Abstract

Nanoparticles are under active investigation for the detection and treatment of cancer. Yet our understanding of nanoparticle delivery to tumors is limited by our ability to observe the uptake process on its own scale in living subjects. We chose to study single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) because they exhibit among the highest levels of tumor uptake across the wide variety of available nanoparticles. We target them using RGD (arginine-glycine-aspartic acid) peptide which directs them to integrins overexpressed on tumor vasculature and on the surface of some tumor cells (e.g., U87MG as used here). We employ intravital microscopy (IVM) to quantitatively examine the spatiotemporal framework of targeted SWNT uptake in a murine tumor model. IVM provided a dynamic microscale window into nanoparticle circulation, binding to tumor blood vessels, extravasation, binding to tumor cells, and tumor retention. RGD-SWNTs bound to tumor vasculature significantly more than controls (P<0.0001). RGD-SWNTs extravasated similarly compared to control RAD-SWNTs, but post-extravasation we observed as RGD-SWNTs eventually bound to individual tumor cells significantly more than RAD-SWNTs (p<0.0001) over time. RGD-SWNTs and RAD-SWNTs displayed similar signal in tumor for a week, but over time their curves significantly diverged (p<0.001) showing increasing RGD-SWNTs relative to untargeted SWNTs. We uncovered the complex spatiotemporal interplay between these competing uptake mechanisms. Specific uptake was delimited to early (1–6 hours) and late (1–4 weeks) time-points, while non-specific uptake dominated from 6 hours to 1 week. Our analysis revealed critical, quantitative insights into the dynamic, multifaceted mechanisms implicated in ligand-targeted SWNT accumulation in tumor using real-time observation.

Keywords: Intravital microscopy, cancer, serial imaging, targeting, specificity, single-walled carbon nanotubes, nanoparticles

Introduction

Nanoparticles (nps) have the potential to revolutionize cancer diagnosis and therapy. Yet the mechanisms of np delivery to the disease sites remain poorly understood. When targeted nps are injected for diagnostic imaging or therapy, typically one only observes a macroscopic effect/picture (via imaging, e.g., PET, SPECT, bioluminescence, Raman, or photoacoustics[1–3]) over time that is assumed to be due to nanoparticles in the tumor. However, due to the lack of spatial and temporal resolution, the underlying microscale interactions of nps that lead to bulk signal at that site are inaccessible and thus not understood. Even if histology or microscopy in living animals is performed to understand np interactions, it is generally at only a single time-point[4, 5], or it is performed in cell culture[6] which while valuable does not recapitulate the complexity of the living mammal. We employ intravital microscopy (IVM), which employs lasers and photodetectors to microscopically image in living subjects[7], to directly and dynamically (repeatedly over weeks) image nanoparticle interactions at many time-points for the first time. This study design enabled us to uncover previously misunderstood, critical features of nanoparticle targeting to cancer in living subjects, such as the role of targeting ligands in tumor specificity.

There remains great debate about how, and whether, targeting ligands actually work in living subjects. Recent literature indicates targeting only increases np specificity of interaction with tumor cells, yet does not affect overall uptake[8–11]. However, many other groups have demonstrated differential levels of uptake between targeted and untargeted nps[12, 13]. This critical question thus remains unresolved. We hypothesized that dynamic IVM could provide unique insights into np behavior in tumors in vivo. Our principal objective was to directly visualize and elucidate the entire spatiotemporal framework of microscale interactions between targeted nanoparticles and the tumor from injection through vascular binding, extravasation, tumor cell binding, and clearance. Herein we employ targeted single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) and frequently observe/quantify their behavior from injection until ~4 weeks post-injection to uncover the fundamental principles underlying np targeting. This enabled us to discover an underlying framework for np targeting which 1. helps resolve the dichotomy in the literature, 2. confirms the importance of temporal effects in targeting, and 3. provides a general structure to help others predict and understand how new nps may behave over space and time. Deep comprehension of the dynamic mechanisms of np delivery has the potential to lead to broad advancement and innovation in nanomedicine.

The Enhanced Permeation and Retention (EPR) effect reflects the tendency in tumors of circulating macromolecules/particles to leak out of blood vessels (permeation/extravasation) and remain there (retention)[14]. EPR is the major mechanism accounting for np distribution into tumor interstitium, but is not well-understood for nps. For instance, in successful siRNA-nanoparticle work in living subjects by Moore and colleagues, their nanoparticles accumulate “…in tumors, presumably resulting from enhanced permeability and retention[15].” This is characteristic of current studies, in which it is unknown (though commonly hypothesized) how nps arrive at/remain in tumors. Furthermore, the retention of nanoparticles is of critical interest to the pharmaceuticals field[16]. These questions of delivery/retention have remained difficult to answer since no dynamic microscopic studies of nps in live subjects have previously been done. Therefore, just as IVM was used to study the hematopoietic stem cell niche[17], we apply IVM to examine the dynamic niche of the tumor-targeted np. This leads to insights that could have far-reaching effects on guiding the engineering and chemistry of injectable nps’ physical structure and ligands, on the imaging of nps as contrast agents or activation as therapeutic agents, and details the interstitial and cellular behavior of nps. Our dynamic, high-resolution approach could thus guide diagnostic tumor imaging and therapeutic treatment time-points and delivery of various nanomedicines.

Materials and Methods

Nanoparticle conjugates

We prepared red-dye labeled, peptide-conjugated SWNT bioconjugates as previously reported, with slight modifications[18]. After sonicating raw Hipco SWNTs in an aqueous solution of DSPE-PEG5000-Amine (NOF Corp) for 1 h, they were centrifuged at 24,000 g for 6 h to obtain short, PEGylated SWNTs in supernatant (~500 PEG chains per SWNT). SWNTs were filtered through 100 kDa filters (Millipore) to remove excess coating polymer. SWNTs were then conjugated to both RGD (or RAD) and Cy5.5. To perform the conjugation, Cy5.5-NHS (Invitrogen) and sulfo-SMCC (sulfosuccinimidyl 4-N-maleimidomethyl cyclohexane-1-carboxylate) (Pierce) were mixed at 1:5 molar ratios (0.2mM : 1mM) and incubated with the SWNT solution at pH 7.4 for 2 h. Upon removal of excess reagents, the SWNT solution was split equally and reacted overnight with 0.2 mM of thiolated RGD (cyclo-(Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe-Lys)) or RAD (cyclo-(Arg-Ala-Asp-D-Phe-Lys)) in the presence of 10 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP, Sigma-Aldrich) at pH 7.4, yielding SWNT-PEG-Cy5.5-RGD and SWNT-PEG-Cy5.5-RAD with both Cy5.5 and RGD / RAD conjugated onto the surface of SWNTs (on average ~8 Cy5.5 molecules per SWNT). Excess peptides were removed by multiple filtrations through 100 kDa filters and washed away by distilled water.

Dorsal Skinfold Chamber

Dorsal skinfold chambers were surgically implanted into male retired breeder C.B-17 SCID mice (>28 g body weight). Mice were anesthetized using an IP injection of mixed ketamine (100 mg/kg body weight) and xylazine (10 mg/kg body weight). The dorsal skin of the mice was extended and two sides of a titanium chamber (APJ Trading, Ventura, CA) were used to sandwich the skin. A ~12 mm diameter circle of skin was removed from one side of the sandwich and a 12 mm glass cover slip (Ted Pella, Redding, CA) was used to cover the skin. Animals were given carprofen at 3 mg/kg SC and 2–3 days to recover from surgery prior to inoculation of a tumor underneath the cover slip. The surgery, recovery, and imaging procedures were approved by the Stanford IACUC.

Tumor model

To create a bright green imageable tumor environment, human glioblastoma cells (U87MG) (obtained from American Type Culture Collection) were labeled with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). The stable EGFP expressing cell lines were established using a lentiviral vector (pRRLsin18.CMV-EGFP, a gift from Luigi Naldini, HSR-TIGET, Italy) with an EGFP transgene. These cells were incubated overnight in media containing high titer virus, after which cells with very high EGFP expression were sorted using FACS. SCID mice (C.B-17 SCID, Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were inoculated with 200,000–300,000 U87MG-EGFP cells in the dorsal skinfold chamber in low volume by removing the glass and pipetting the cells in with PBS. Tumors were imaged ~10 days after inoculation.

Intravital Microscopy

DSC-installed SCID mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and positioned beneath the objective of an IV-100 intravital microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA). Chambers were locked into position using a stainless steel, custom-designed stage. Long-circulating dye Angiosense 750 (VisEn Medical, Woburn, MA) was injected to outline the vasculature. 180 µl of ~400 nM SWNTs (RGD-SWNTs, RAD-SWNTs, plain SWNTs (no peptide), and a 2.5X decreased concentration of RGD-SWNTs) were subsequently injected. Mice (n=20) were imaged during injection and for the following 4 hours. They were re-imaged at 6–8, 12, and 24 hour time-points, every day for a week following injection, three times within the second week post-injection, and at 3, 4, 5, and 6 weeks post-injection. Mice were imaged using the 488, 633, and 748 nm laser lines, and three output channels (green, red, and near-infrared). Output channels were scanned sequentially to prevent filter bleed-through.

Data were analyzed using two customized algorithms developed to quantify SWNT binding to tumor cells using fluorescence (quantified as percent particles bound/associated (or unbound/unassociated) compared to either the total number of particles in the field-of-view or the available binding surface area of cells, see Supplementary Material), manual measurements of SWNT binding length for vascular binding, measurements of SWNTs in tumor macrophages compared with total amount of SWNTs in the image, and associated statistical tests described below.

Statistics

We quantified vascular binding and tumor cell binding over time, and performed statistics. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata Release 9.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). A significance level of 0.05 was used.

Vascular binding

Mice were injected with SWNTs and SWNT binding along vessels was measured after injection in various vessels in various fields of view (FOVs) in each animal. Vessel length and width were measured to calculate vessel surface area as the exposure variable. SWNT binding rates by group and over time were estimated and compared by zero-inflated negative binomial regression adjusted for clustering of vessels within FOVs within animal. A Mann-Whitney test was performed to compare experimental groups to control groups, and a Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare control groups to one another.

Tumor cell binding

To quantify the amount of SWNTs associated with the cell surface, images from each time-point from each mouse were quantified via the algorithm discussed in the intravital microscopy section above and subjected to statistical tests. Greater than 1000 images were analyzed. Measurements were made of bound/associated and unbound/non-associated (to tumor cells, colored yellow in Fig. 5b) RGD- or RAD-SWNTs in multiple FOVs at various magnifications at 13 time-points from 1 day to 4 weeks after SWNT injection (n=12 mice). Measurements were made using two different algorithms, and at two different intensity thresholds (see Supplementary Data). Effects of ligand (RGD vs RAD) on the SWNT, algorithm, threshold, and time were assessed by negative binomial panel regression of particle counts, with field-of-view size (1/magnification) as exposure variable, and adjusted for clustering within animal. Comparisons between conditions with p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. See Supplementary Material for more extensive analysis.

Results

Binding to Vascular endothelium

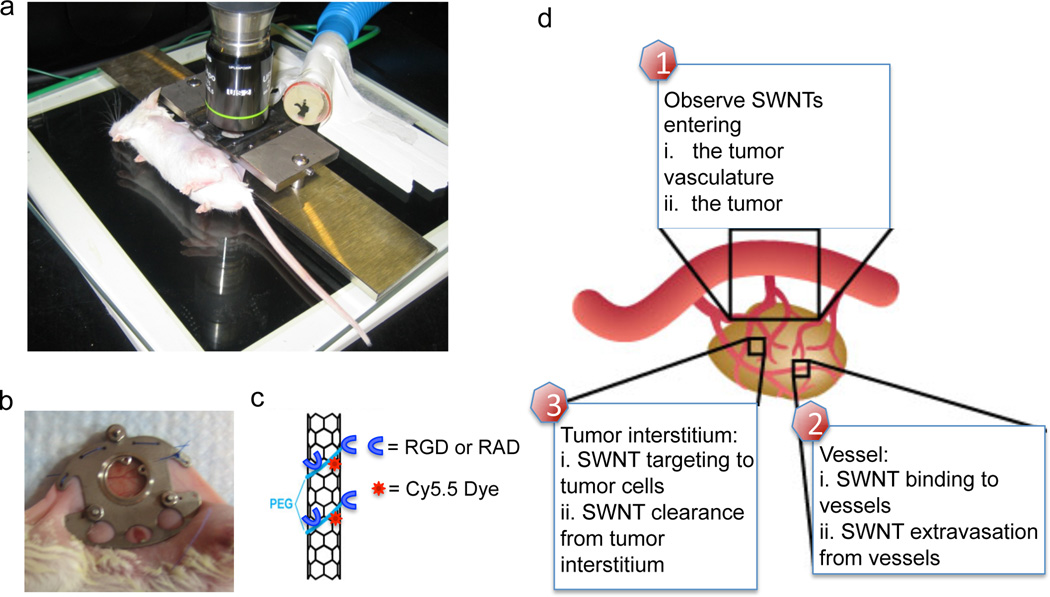

Vascular targeting is an important option in the tumor targeting arsenal. For instance, in therapeutic disciplines such as anti-angiogenic treatments, vascular re-normalization, [19, 20] and in diagnostics for vascular imaging[21–23]. The dorsal skinfold chamber (Fig. 1a–b) represents a useful system to study particle binding to the vasculature as part of the np targeting framework (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1. Mice are imaged with intravital microscopy.

a. Mice are imaged with intravital microscopy on a customized stage. b. A titanium chamber surgically implanted into the mouse dorsum with window. c. Schematic of 2 nm × 200 nm single walled carbon nanotubes employed, with PEG coating Cy5.5 dye, and RGD or control RAD peptide functionalization. d. A schematic of a tumor and its vasculature system, illustrating the major facets we observe in this study from entry of SWNTs, their binding to vasculature, to their extravasation and binding to tumor cells.

SWNTs are excellent cancer targeting agents (and a uniquely promising solution to imaging and therapy[12, 24–30]; while debate remains, these SWNTs proved non-toxic in live animals[31]), and we aimed to identify why they target cancer so effectively (10–15% ID/g[24]). Such work will likely increase their delivery efficacy allowing acceleration of their transition into clinical utility[32], in addition to further toxicity studies. SWNTs were conjugated to RGD (Fig. 1c) for targeting to integrin αvβ3, which is overexpressed on endothelium lining blood vessels in tumors and on the cell membrane of tumor cells such as U87MG. While histology or IVM have been used to suggest that nps can target vasculature[33], it has never been dynamically quantified to our knowledge. We injected typically 70 pmol targeted SWNTs (RGD-SWNTs) or controls (RAD-SWNTs or plain SWNTs conjugated to Cy5.5) into tumor-bearing mice, or RGD-SWNTs into control non-tumor bearing mice (n=20). We focused on time-points from injection until SWNTs cleared from the vasculature (typically ~5–6 hours p.i.[24]) and only performed binding measurements on vasculature after SWNTs had fully extravasated in order to minimize confusion between circulating SWNTs and bound SWNTs. This study design allowed us to quantify binding as a mean binding length along the vessel with respect to the total surface area of vessels available for binding.

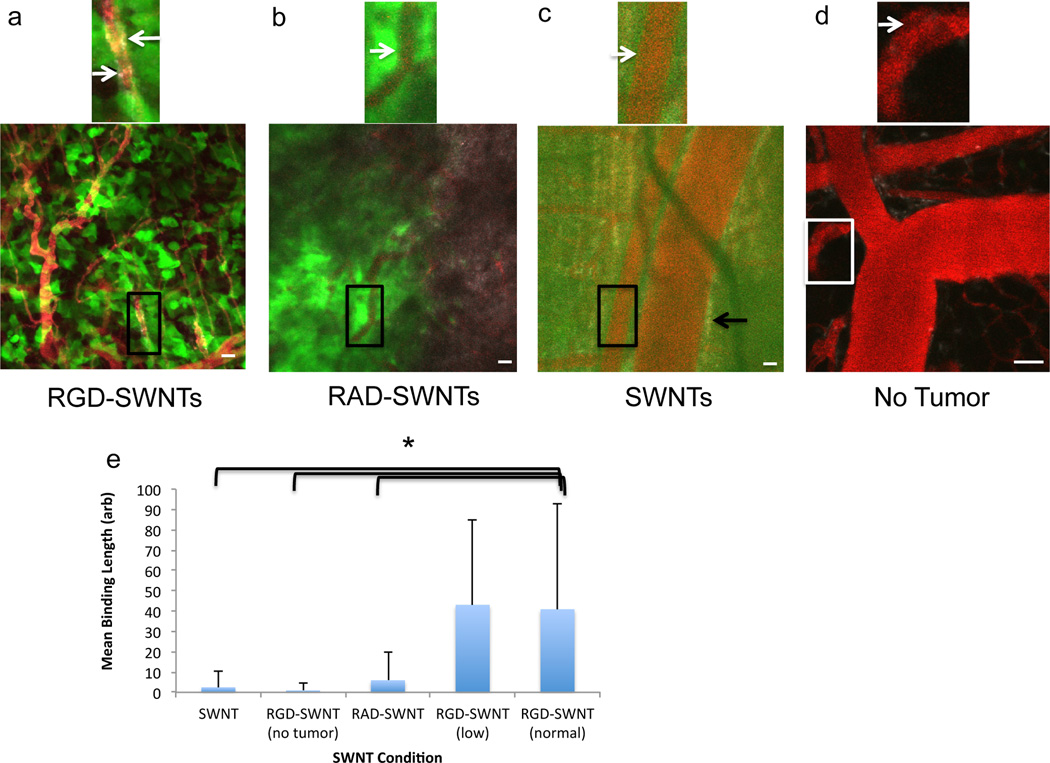

Within four hours of injection, we observed that RGD-SWNTs labeled parts of tumor vascular endothelium (Fig. 2a, where binding is defined as np fluorescence along the inner surface of the vessel rather than signal near to, but outside, the vessel – extravascular signal represents extravasated SWNTs). While some binding was visualized in the control conditions (Fig. 2b–d), it was minimal relative to RGD-SWNT binding to tumor vasculature (RGD-SWNT conditions bound neovasculature more than controls, p<0.0001, Fig. 2e). Even when we reduced the RGD-SWNT injection quantity 2.5-fold, we observed significantly more binding than controls (the RGD-SWNT groups did not differ significantly). RGD-SWNTs bound at least 4X more than RAD-SWNTs.

Figure 2. Vascular binding of SWNTs to blood vessels.

a. The vascular binding of specific RGD-SWNTs to tumor blood vessels (boxed region magnified to illustrate a region of binding - SWNTs are in grayscale, tumor cells in green, and blood vessels in red). Arrows point to regions of binding (grayscale) along the blood vessel surface. b. Control RAD-SWNTs do not generally bind vasculature, as shown with a representative field-of-view (arrow points to edge of blood vessel; no binding is observed). c. Control plain SWNTs (no peptide) display low binding to vasculature. The white arrow points to the edge of a blood vessel in which no binding is observed, while the black arrow points to SWNT signal that is near to, but outside of, the vessel and thus is not included as being bound to the vessel (instead, the SWNTs have extravasated). (a–c) Scale bars: 50 µm. d. When RGD-SWNTs are injected intravenously into a mouse without tumor, little binding results as illustrated in a representative field-of-view (arrow indicates the edge of a vessel; no binding is observed). Scale bar: 40 µm. e. Comparison of vascular binding across all experimental conditions computed as mean binding length over available vessel surface area. RGD-SWNTs at both concentrations bound vessels significantly more than all other groups (p<0.0001), but were not different from each other.

Since quantum dots have been shown not to bind tumor neovasculature individually[22, 23], it is notable that dispersed SWNTs are capable of binding (Fig. 2) as observed by the presence of diffuse fluorescence along the vascular boundary. This may be due to their unique geometry (see Supplementary Discussion). Moreover, we occasionally observed intense RGD-SWNT signal in highly tortuous vessels. We observed that such labeled tortuous vessels periodically lost functionality (Supplementary Fig. 1), which could be due to extensive RGD binding which can induce apoptosis[34] (see Supplementary Discussion) and help reduce vessel functionality. We also note here that during SWNT circulation we observed SWNT uptake into circulating leukocytes (manuscript in preparation); this resulted in a surprising delivery mechanism that accounts for substantial uptake in which these circulating cells extravasate into tumor and account for >20% of total RGD-SWNT accumulation in tumor at 1 day p.i. (see Supplementary Fig. 2). Some proportion of these cells remained in the tumor for days to weeks in all SWNT conditions (manuscript in preparation), so some fraction of the SWNT signal detected in the tumor over time is due to this uptake mechanism (discussed further in the Discussion section).

SWNT Extravasation

We visualized SWNTs entering into the tumor circulation (the speed of which varied considerably, see Supplementary Movies 1–2) and their extravasation due to EPR for the duration of SWNT circulation using IVM. We continued to monitor identical sites of tumor nearly every day for a week, and then weekly thereafter in order to understand the overall kinetics of SWNT extravasation and retention within the tumor.

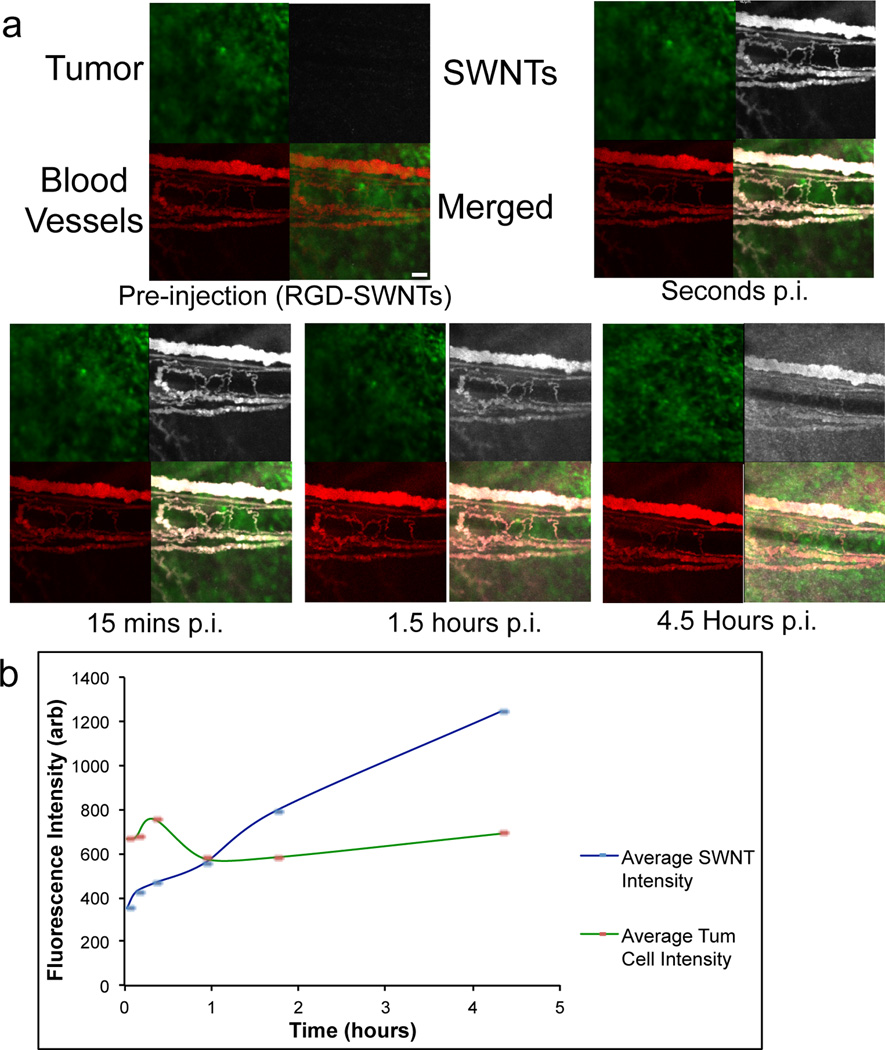

Due to their size/shape, SWNTs are capable of extravasation in U87MG tumor[35]. Extravasation was observed to be highly heterogeneous. The distribution was at times dispersive (Figure 3) and/or point-like (Supplementary Movie 3). Based on the rise in interstitial fluorescence over several hours, it is clear that RGD-SWNTs steadily extravasate and accumulate throughout the tumor interstitium (Fig. 3a–b). Control SWNTs (RAD-SWNTs and plain SWNTs) displayed similar extravasation properties as RGD-SWNTs (Supplementary Fig. 6). Over 4.5 hours, the interstitial fluorescence intensity increased more than 3-fold in a typical FOV in a typical animal, while the fluorescence of an internal control (the tumor cells) remained approximately flat (minor variations are mostly due to small movements of the mouse) (Fig. 3b). While Figure 3 addresses SWNT extravasation/permeation into the interstitium (4–6 hrs p.i.), Figure 4 addresses the “retention” aspect of the EPR (Enhanced Permeation and Retention) effect over weeks.

Figure 3. SWNT extravasation into tumor.

a. Selected time-points show extravasation in a selected region of U87MG tumor in the dorsal skinfold chamber from pre-injection of RGD-SWNTs until 4.5 hours post-injection (p.i.) of RGD-SWNTs at the same site. b. Region-of-interest analysis of extravasation is graphed, illustrating the monotonic increase in RGD-SWNT presence in tumor interstitium over time (linear trend slope = 203), while tumor cell fluorescence as an internal control remains flat (linear trend slope = −2) over 4.5 hours. The tumor extravasation kinetics are representative of all SWNT conditions (RGD-SWNTs, RAD-SWNTs, SWNTs) injected into mice bearing tumor. Scale bar in the merged pre-injection panel represents 100 µm for all panels displayed in the figure.

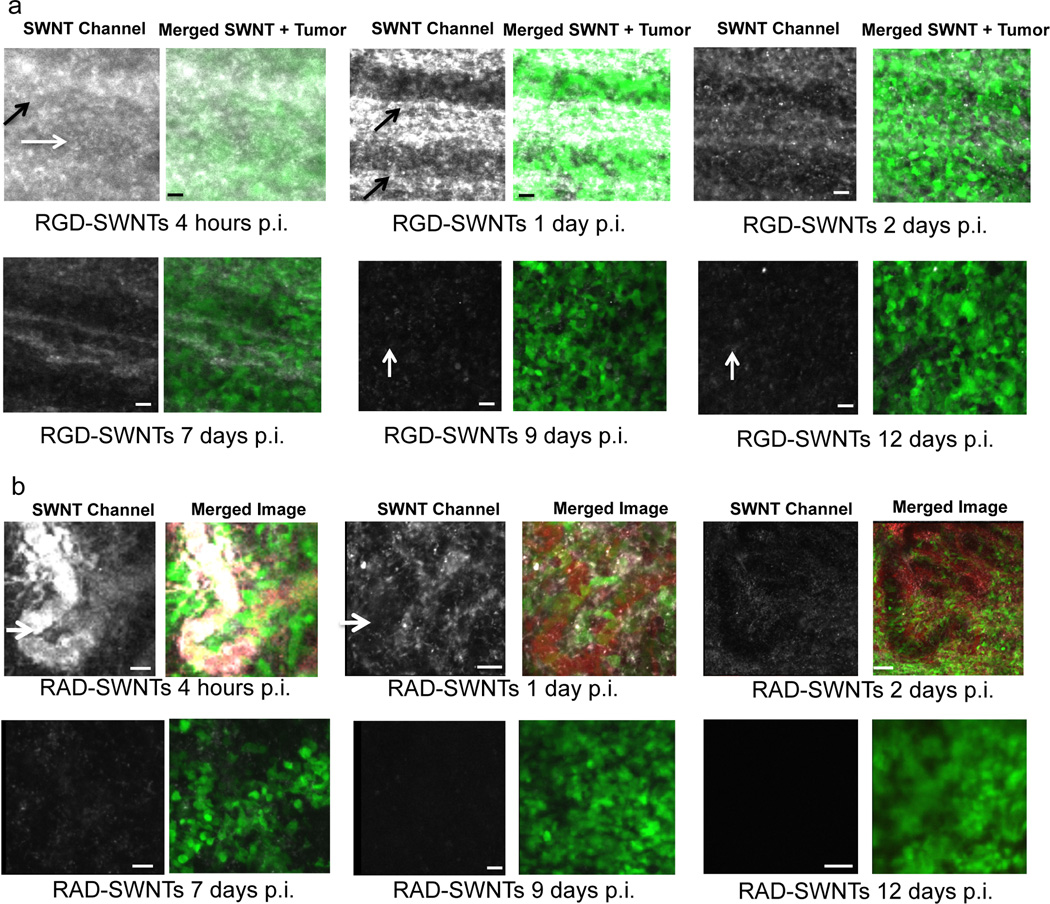

Figure 4. SWNT retention in tumor.

Time series showing the clearance of RGD-SWNTs (a) and RAD-SWNTs (b) at the same respective site within each tumor from 1 to 12 days p.i. SWNTs are present in abundance in tumor interstitium at early time-points, but they clear at later time-points. At each time-point, the panel to the left displays the SWNT channel, while the right panel displays a merged image that includes the tumor (and blood vessels (red) if their presence in that image does not obscure the view of SWNTs and tumor). Note the similarity in retention between RGD and control in the early time-points, but qualitative divergence afterward. In particular, RGD-SWNTs are still present at 9 and 12 days p.i. (white vertical arrows), while no RAD-SWNTs are observable at 9 and 12 days p.i. These data are quantified over many FOVs and mice in Fig. 5c–d. RGD-SWNTs in the interstitium are designated by horizontal white arrows and blood vessels are designated with angled black arrows in (a); blood vessels in the RAD-SWNT condition are designated by short horizontal white arrows in (b). All scale bars for both (a) and (b): 40 µm.

The retention of SWNTs over the first 12 days p.i. is a function of time and targeting ligand (Fig. 4a–b; see Supplementary Fig. 9 for the blood vessel channel at each point). RAD-SWNTs extravasate similarly to RGD-SWNTs (Fig. 4a–b, 4hrs) and their retention is also similar up to 7 days p.i. (Fig. 4a–b, at the same site over time). Yet by 7 days p.i. and afterward, the retention kinetics between RGD-SWNTs and RAD-SWNTs clearly appear considerably different. After 1 week p.i., SWNT signal is observed in the RGD-SWNT condition, while it is minimal to non-existent in the RAD-SWNT condition (quantified in Fig. 5c–d). SWNT presence and quantification is verified by Raman microscopic analysis in live animals at 1 week p.i. (Supplementary Fig. 3). Plain SWNTs extravasate similar to the peptide-conjugated SWNTs. However, plain SWNTs cleared much more rapidly than RAD-SWNTs, as they are mostly cleared by 3 days p.i. and almost fully cleared by 1 week p.i. (Supplementary Fig. 3). These data demonstrate considerably different kinetics between the plain SWNT and RAD-SWNT controls, and may indicate the need for controls to be as similar as possible to the experimental condition to make useful comparisons (RAD is non-specific, and RAD-SWNTs are only 1 amino acid different in structure than RGD-SWNTs, making RAD-SWNTs highly similar to RGD-SWNTs).

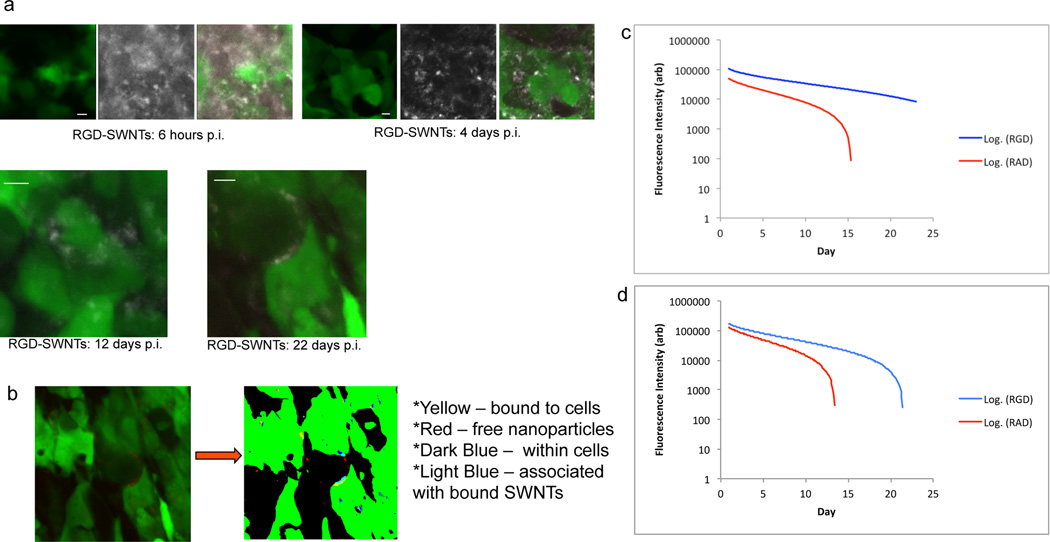

Figure 5. Quantitative SWNT binding to individual tumor cells over time.

a. Representative high-magnification images of tumor in the RGD-SWNT condition of live mice are shown over 3 weeks (6 hours, 4, 12, and 22 days p.i.). Notice the decrease in RGD-SWNTs in the extracellular space over time. At the 6 hour and 4 day time-points, panels include tumor (left), SWNTs (center), and merged (tumor + SWNTs); at 6 hrs RGD-SWNT signal is nearly as high away from tumor cells as it is on cells, while by 4 days p.i. RGD-SWNTs have cleared considerably from the extracellular space. Merged images alone are shown at 12 and 22 days p.i.; at 12 days it appears that most RGD-SWNTs in the FOV are on the cells, and at 22 days post-injection, essentially all the RGD-SWNTs in the image appear bound to the tumor cells (see Supplementary Fig. 6 for RAD-SWNT images). Scale bars in all images are 10 µm. (b) To quantify SWNTs bound to tumor cells compared with unbound SWNTs, raw images were binarized and custom algorithms were applied. SWNTs were categorized using a color-coding scheme: SWNTs bound to tumor cell surface were yellow, SWNTs within tumor cells were dark blue, SWNTS associated with SWNTs bound to cells were light blue, and SWNTs freely diffusing in interstitium were red. Bound RGD-SWNTs and RAD-SWNTs were quantified from >1000 total images (n=12 mice) processed via our algorithms from 1 day until nearly 4 weeks p.i. c−d. Bound (c) and unbound (d) RGD-SWNTs and RAD-SWNTs were plotted on log plots (curves with error bars in Supplementary Fig. 5). The curves significantly diverge by 7 days p.i. in both (c) and (d) (p<0.001), showing RAD particles were removed at a faster rate than RGD particles (p<0.001). Observe that both free RGD-SWNTs and free RAD-SWNTs decrease dramatically over time, as do bound RAD-SWNTs, but bound RGD-SWNTs linger in the tumor and decrease steadily for nearly 4 weeks.

RGD-SWNTs and RAD-SWNTs remained within tumor interstitium at similar levels for up to 7 days after injection. Afterward RGD-SWNTs persist while RAD-SWNTs are removed from tumor, implying that the effects of targeting (i.e., RGD) on retention in tumor are observed only after ~7 days p.i. Note the signal at 9 and 12 days p.i. in the RGD-SWNT condition is low (Fig. 4a). This dramatic reduction in overall signal is attributable to the clearance of unbound RGD-SWNTs; we use high-resolution imaging and quantitative image analysis to show that the remaining RGD-SWNTs in tumor are bound to the surface of tumor cells as described below.

Tumor Cell Binding and Retention

Most nanoparticle-based imaging and therapeutic strategies target tumor cells. No matter the mechanism used to enable particles to reach the interstitium (including extravasation, as employed here, or active methods[36, 37]), the nps must usually interact with and bind directly to tumor cells in order to perform their function. This process of diffusion through interstitium, binding to tumor cells, and retention is not understood and remains a major question in, for instance, the field of pharmaceutics. This section quantitatively addresses how retention is modulated by RGD as a function of binding to tumor cells.

Employing the same mouse cohort (n=20), we used IVM to image the tumor from injection until 4 weeks p.i., with time-points taken several times in the first day, each day for a week, and then approximately weekly thereafter. We acquired many micrographs for each mouse at each time-point, with >1000 images analyzed. To quantitatively analyze this volume of images, we developed algorithms to evaluate the binding of nps to tumor cells (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Figs. 4–5).

Early time-points displayed massive extravasation and little apparent specific tumor cell binding (Fig. 5a, 6hrs) across all conditions (except non-tumor bearing mice, in which little extravasation was observed, data not shown). However, we observed that as time post-injection increased, RGD-SWNTs tended to associate with the tumor cell surface (Fig. 5a, 4 days p.i.). By 4 days p.i., RGD-SWNTs were often bound to tumor cells, yet considerable quantities of RGD-SWNTs remained free in the tumor interstitium. As time continued, however, unbound RGD-SWNT signal decreased; i.e., they were evidently cleared, and the RGD-SWNTs remaining in the tumor appeared to be predominantly bound to tumor cells (Fig. 5a, 12 and 22 days p.i.; also compare 2–3 weeks p.i. for RGD-SWNTs (blue curves) in fig. 5c against fig. 5d). Incredibly, by 3 weeks after injection, we observed RGD-SWNTs clearly bound to the surface of tumor cells, often without free RGD-SWNTs in the region (Fig. 5a, 22 days; Supplementary Fig. 10 displays separated tumor and SWNT channels from 12 and 22 days p.i.). Interestingly, control RAD-SWNTs paralleled the behavior of RGD-SWNTs in the early time-points up to 1 week p.i., while control plain SWNTs paralleled only the extravasation, and were cleared rapidly thereafter. Qualitatively, RAD-SWNTs both associated with the tumor cell surface and remained in the interstitium (in fact, there was no statistically significant difference between RGD-SWNTs and RAD-SWNTs bound to tumor cells until a week p.i. (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Figures 5–6)). Yet after ~7 days, there was a notable decrease in RAD-SWNTs within the region, both bound to tumor cells and free in the interstitium.

Using our algorithms, we quantified the above qualitative observations. These algorithms are described in detail in Supplementary Methods and Data (see Supplementary Figs. 4–5). Briefly, we binarized the tumor cells in our images (Fig. 5b) and employed several approaches to categorize SWNTs using a color-coding scheme to differentiate bound/associated SWNTs from internalized or unbound SWNTs (Supplementary Fig. 4). We developed two image analysis algorithms to quantify SWNTs (Supplementary Fig. 4). We used the algorithms to compute the quantities of RGD-SWNTs and RAD-SWNTs on the surface of cells and freely diffusing in the interstitium (we omit plain SWNTs and non-tumor animals because they displayed minimal tumor cell association (and extravasation, in the non-tumor case) and were not retained long in the interstitium (see Supplementary Fig. 3, and non-tumor data not shown)). Similar to our qualitative observations, RGD-SWNTs and RAD-SWNTs had quantitatively similar tumor cell binding profiles until about 1 week p.i. (in fact, though the RGD-SWNT curve is always clearly at least slightly above the RAD-SWNT curve, the fluorescence at each time-point was not statistically different until 1 week p.i. (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. 5)). The RGD-SWNT curve diverges significantly from the RAD-SWNT curve (p<0.001), implying that at 1 week and beyond RGD-SWNTs tend to bind tumor cells over time in contrast to RAD-SWNTs, which may only be transiently associated with the tumor cells. RGD-SWNTs show a steady, yet gradual decrease in tumor cell binding profile (approximately linear in the logarithmic graph displayed), suggesting they may be in bound (predominantly) and unbound states for an extended period (Supplementary Fig. 7). Notably, the RAD-SWNT curve rapidly diverges beginning after 7 days p.i., and by 2 weeks p.i. a huge reduction is clear (Fig. 5c).

While tumor cell binding of SWNTs is critical, it only provides one attribute of SWNT interactions in tumor interstitium. We next observed the time-dependent behavior of free (unbound) RGD- and RAD-SWNTs in the tumor interstitium in order to understand the overall kinetics of particle behavior and to place the tumor cell binding data in context. The two curves (Fig. 5d) begin at the same point at 0 days p.i. (several hours after injection). This is immediately after SWNTs extravasated, confirming that the extravasation profile of RGD-SWNTs is identical to that of control RAD-SWNTs. While the curves are substantially similar until ~7 days p.i., they are clearly slowly diverging, and this divergence is significant (p<0.001). Both curves significantly decrease over time (p<0.001, Figs. 5c–d). Note that the shape of the unbound RAD-SWNT curve (Fig. 5d) is similar to that of the RAD-SWNT curve in the bound SWNT graph (Fig. 5c). Both curves drop off dramatically around 10–14 days p.i., suggesting that after a certain threshold, the SWNTs are cleared likely because there is no specific interaction (e.g., ligand-receptor) keeping them in the tumor region. However, the shape of the RGD-SWNT curve in the bound graph (Fig. 5c) is much different from that of the unbound RGD-SWNT curve (Fig. 5d). After a certain critical point, unbound RGD-SWNTs diminish rapidly while bound RGD-SWNTs continue to decline gradually; this implies nearly all RGD-SWNTs remaining in the tumor region are bound to tumor cells over time (by ~3 weeks p.i. by comparison between the bound and unbound curves, in which the bound curve continues to ~4 weeks p.i. nearly linearly on the log graph).

Careful inspection of the curves and data shows that a higher amount of even unbound RGD-SWNTs remain in the tumor region longer than RAD-SWNTs remain in interstitium. Coupled with the fact that RGD-SWNTs are binding to tumor cells with greater longevity than RAD-SWNTs, this provides evidence that the mechanism of np binding may be considered a grand equilibrium process. That is, a dynamic process is occurring in which RGD-SWNTs tend to remain bound to the surface of tumor cells over time, while transiently associated (i.e., non-specific interactions) RAD-SWNTs clear over the same period (which is ~1 week in our model, see Supplementary Data for discussion). Plain SWNTs extravasated similarly to RGD-and RAD-SWNTs, but rapidly cleared within 3 days (data not shown) and were at close to background signal by 1 week p.i. (Supplementary Fig. 3), which suggests that even the presence of a non-specific peptide (RAD) attached to SWNTs confers an increased ability for SWNTs to remain in tumors. These data indicate that the presence of a tumor cell-specific targeting ligand promotes accumulation of SWNTs over time relative to untargeted SWNTs.

Discussion

The impact and utility of np targeting ligands on the ability of nps to accumulate in tumor is a critical and somewhat controversial topic. Recent studies suggest that targeting provides no benefit in agent accumulation[8–11], but rather enables an agent to interact with its cognate and thus bind to the desired cells. By offering the spatiotemporal resolution necessary to help resolve this question, our dynamic microscale study partially confirms the above hypothesis, but cautions that this perception is highly time-dependent, i.e., targeting critically depends upon the time after injection at which one observes. In fact, our data show relatively similar binding to/association with tumor cells between RGD-SWNTs and RAD-SWNTs (Fig. 5) in the first few days after injection, but differences increase as RGD-SWNTs remain within the tumor interstitium for weeks while RAD-SWNTs persist for up to a week prior to departing en masse. This fits with current literature, as others’ nanoparticle measurements occurred 1 day after injection[8], or were performed over one week[9]. Notably, we only began to observe differences between the quantity of unbound targeted and untargeted particles after ~1 week, while we were able to discriminate between the two in the bound state slightly earlier. Kirpotin and colleagues showed they could distinguish between targeted and untargeted particles 44 hours after injection[9]. Because this was quantified using flow cytometry, a technique that is more sensitive but does not allow testing under native conditions and is thus unlike our imaging approach, the wash conditions (and a host of other parameters, see Supplementary Data) could explain the discrepancy. Despite these differences, based on our data it is likely that if Kirpotin and colleagues had examined signal at later time-points, the overall kinetic structure would be similar to what we observed. In particular, the initial levels of targeted and untargeted nps would be similar for a certain time period (during which targeted particles tend to bind cells), yet over time targeted particles would tend to remain bound and thus would not be cleared; conversely, untargeted particles would typically not be associated with cells and would slowly be cleared by the lymphatic system over time. We assume that the decrease in fluorescence signal in this work is due to lymphatic clearance of nps, as it has been shown that the major route of nanoparticle clearance out of tumors is typically via the lymphatic system[38, 39]; however, note that we have not directly demonstrated that this is how the SWNTs clear in this work. Non-specific RAD-SWNTs likely clear more slowly than expected because they do display some (albeit non-specific) association with the tumor cells, which while not nearly as strong as RGD-SWNT specificity, provides a mechanism for them to remain in the interstitium for several days (compared with plain SWNTs which clear within 3 days). We note here that while it is possible that the decreasing fluorescent signal we observed (e.g., Figs. 4–5) could potentially be due to SWNT fluorescent signal decline due to physiological conditions/fluorescence quenching, that is unlikely to be the major contributor because we observe that: 1. While there is a large decrease in SWNT signal in unbound RGD-SWNT as well as associated and non-associated RAD-SWNT conditions (Fig. 5c–d), there is a steady, very slow decrease in bound RGD-SWNTs (Fig. 5c, blue curve) – this suggests that the large decrease observed in unbound RGD-SWNT and both RAD-SWNT conditions was predominantly due to actual departure of SWNTs from the tumor site rather than fluorescence decline. If the effect were due to fluorescence quenching by the physiological environment, one would expect all conditions to decrease similarly (i.e., a large decrease would be observed across all conditions). This explanation, however, does not address the steady decrease of fluorescence signal observed in all conditions beginning on day 0 and continuing throughout the experiment (Fig. 5c–d). 2. This steady decrease is likely due to a combination of SWNT clearance plus a gradual decrease in fluorescence intensity over time due to quenching/stability. We attributed the steady decrease as due mostly to SWNT clearance, as we showed that intrinsic Raman signal (which is due solely to SWNT presence and is not affected by fluorescent issues nor physiological concerns[25]) decreases in accord with fluorescence (from 1 to 3 weeks p.i., see Supplementary Fig. 8). Fluorescence has been shown to be fairly well-retained under physiological conditions in living subjects for at least 4 months[40], and for at least several weeks in mice for organic dyes similar to those used here[41]. To ensure that our nanoparticles behave similarly, we tested our SWNT-dye conjugates under mimicked physiological conditions (100% serum incubated at 37°C), and showed the average Cy5.5 fluorescence per SWNT declined less than 5% over one week (Supplementary Fig. 11). This data suggests the vast majority of the fluorescence decrease observed in Fig. 5c–d is due to SWNT clearance rather than SWNT-dye stability.

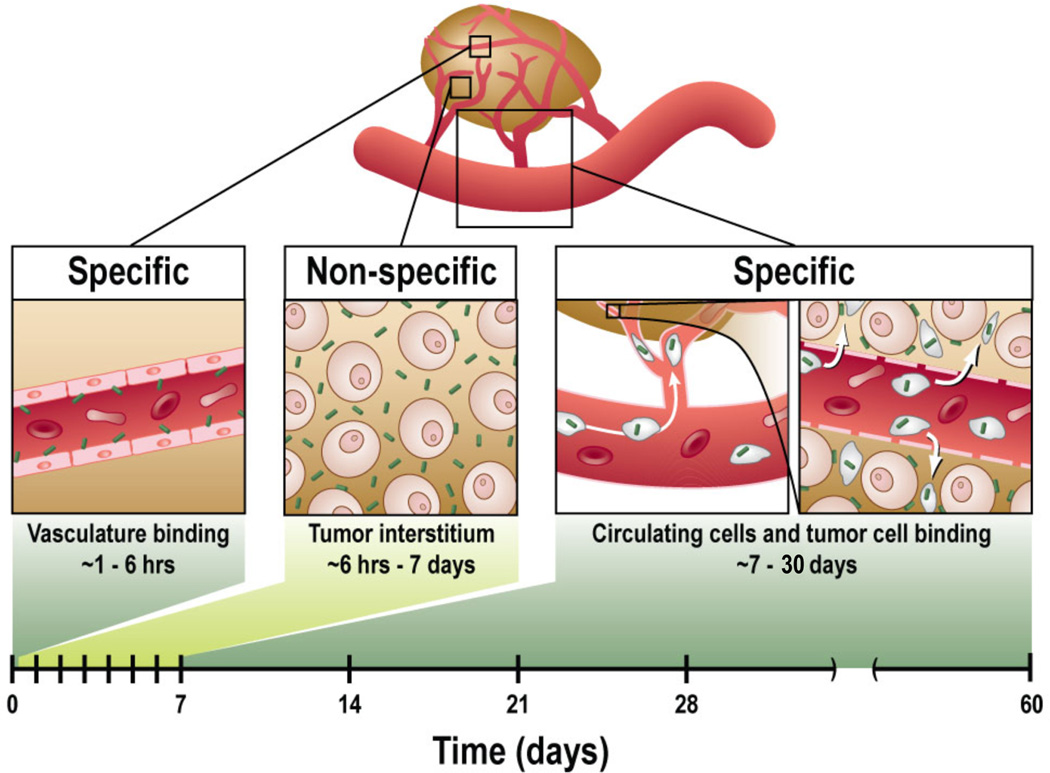

Our data overall imply a general structure for np targeting once the particles have extravasated: an interplay in the tumor interstitium between binary states (cell-bound and unbound particles) which are fixed (bound) or diffuse freely through the interstitial space (unbound, likely to be cleared lymphatically). Endowing a particle with specificity (via, e.g., targeting peptides, antibodies, and aptamers[22, 42, 43]) thus likely increases the time an average particle remains in tumor, ultimately leading to increased accumulation in tumor compared with the nonspecific condition. This explains our data; for instance, it explains why we observe fewer untargeted agents in both associated (Fig. 5c) and non-associated (Fig. 5d) states compared with targeted (RGD) agent binding. The interplay is described schematically for targeted particles (Fig. 6), illustrating the time periods in which np targeting specificity is seen (the time frame for the present experimental model is shown along the bottom). Moreover, understanding the spatiotemporal processes involved in SWNT targeting has the potential to increase the efficacy of SWNTs for imaging and therapy by providing the framework to choose the most efficacious time-points to image or treat cancer using targeted SWNTs; increasing their efficacy is critical to hastening the utility of SWNTs in the clinic[32, 44].

Figure 6. Framework of RGD-SWNT tumor targeting.

The framework summarizes the periods of specific accumulation of RGD-SWNTs in tumor. From ~1−6 hours p.i., the RGD on RGD-SWNTs enables specific vascular binding. Afterward, up to 1 week p.i., extravasated SWNTs overwhelm specific vascular binding, rendering the SWNT signal in tumor non-specific. Yet by 1 week p.i., unbound SWNTs are removed from tumor, so that any RGD-SWNTs remaining are predominantly bound to tumor cells. The final specific box (~7−30 days) includes SWNTs which are taken up by cells in the bloodstream and deposited in tumor, which can account for over 20% of SWNTs accumulated in tumor by 1 day p.i. (see Supplementary Fig. 2).

This work applies IVM to understand the tumor targeting framework of SWNTs, but limitations exist, including the fact that here we have studied only one nanoparticle system, one cell line, and one tumor site within the animals. Also, we have examined tumors at only one stage of development, and it is known that extravasation may vary across tumor stages[45]. Moreover, the dorsal window tumor site that we chose for its ability to allow long-term serial imaging may be less natural than other sites; for instance, the tumor is more compressed. In future studies other window chamber techniques at more natural sites may be useful for serial imaging[46]. Furthermore, we note that in this work we have not established the relative quantities and rates of SWNT internalization into tumor cells; while we have this raw data, we are addressing spatial resolution issues, particularly axial, to be able to confidently resolve this important question. While the timeframes we established in this system will almost certainly change as a function of nanoparticle/ligand type, tumor type, and site, the same analysis performed here can be performed under other conditions to resolve the new parameters; moreover, it is likely that the general targeting framework we uncovered here will parallel how other nanoparticles target cancer in solid tumors and that the effect of the ligand on targeting will be temporally dependent, that is, ligand specificity only causes increased accumulation during specific time periods (Fig. 6). Interestingly, Liu et. al. showed that RGD-SWNTs target tumor much better than a control at very early time-points[24]. The disparity with our data might be due to several factors, but likely the major cause is that the comparison was between RGD-SWNTs and control plain SWNTs[24]. Our results also showed that plain SWNTs did not target tumor as much as RGD-SWNTs even in early time-points (Supplementary Figure 3 and data not shown for early plain SWNT time-points); however, our results show that a more suitable control is RAD peptide, which mimics the presence of RGD without its specificity. This control allows us to tease out the differences in targeting properties over time, and to show that specific tumor cell targeting occurs only within the context of the interstitial equilibrium process described above. Other differences between Liu et. al.’s work and ours include that the tumor is at a different site (which may lead to major differences in extravasation and clearance, as well as vascular targeting, which could be responsible for the increase in RGD-SWNT specificity in the earliest (e.g., 0–6 hour) time-points). Finally, we note that the phenomenon of SWNT uptake driven by leukocyte targeting of tumor (Fig. 6) may partially confound some of our results on the quantitative differences in targeting between RGD-SWNTs and RAD-SWNTs as they are typically counted as free in the interstitium. However, because SWNTs are delivered via this mechanism in both conditions, the overall differential effects between conditions are expected to be minimal and will not change the conclusions (see Supplementary Data for further discussion and for other limitations).

In summary, we employed IVM in the first study to directly de-convolute the mechanisms underlying np delivery, examining targeting dynamics in live animals from injection through vascular binding, extravasation, cell binding, and retention/clearance. Our analysis suggests that specific targeting is realized only at certain, limited time periods, such as early-stage vascular binding and late-stage targeted tumor cell binding, but not at other times. Our data further indicate that targeted tumor cell binding is an equilibrium process in the tumor interstitium in which specific targeting ligands promote np adhesion to tumor cells, thereby lessening the likelihood of clearance. Our analysis also uncovered a surprising delivery mechanism via specific leukocyte uptake that accounts for a substantial portion of SWNT accumulation in tumor (>20%). Taken together, these analyses offer a new paradigm for SWNT/nanoparticle targeting, quantifying the impact of a targeting ligand on several delivery mechanisms, including vascular targeting, extravasation, and tumor cell binding, which should help guide the proper time-points for np-based diagnostic imaging and therapeutic treatment.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Quantitatively de-convoluted carbon nanotube targeting to tumors in live mice

Microscale visualization of targeting from injection to cell binding to clearance

Identified characteristic framework underlying nanoparticle targeting to tumors

Determined how targeting ligands lead to specificity in tumor targeting

Nanotubes taken up into circulating cells are unexpectedly taken up into tumor

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by an NCI K99/R00 Award CA160764 (BRS) as well as NCI U54 CA119367 (SSG). We would like to thank Mana Jammalamadaka, Jarrod Marks, and Harikrishna Rallapalli for their assistance with image processing and Timothy Larson for his assistance with SWNT characterization.

Biographies

Bryan Smith

Bryan Smith completed his Ph.D. in Biomedical Engineering as an NSF Pre-doctoral IGERT Fellow at The Ohio State University, where he worked in biomedical nanotechnology and modeling. He moved to Stanford University for his postdoctoral work, where he was appointed a Stanford Molecular Imaging Scholar NIH Fellow and was awarded a Stanford Dean's Fellowship. Smith's work at Stanford has focused on understanding how nanoparticles behave in living subjects in microscopic detail. He was recently granted a K99/R00 award for his work on integrating experiments with computer simulation to optimize nanoparticle design for imaging and therapy.

Cristina Zavaleta

After receiving her PhD in 2006 from University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, Cristina Zavaleta began her postdoctoral fellowship at Stanford University in Professor Sam Gambhir’s Multimodality-Molecular-Imaging-Laboratory. Here she utilizes several preclinical imaging devices to sensitively detect the localization and tumor targeting efficiency of various nanoparticles that have been chemically modified with specific targeting ligands, in small animal models. More recently, she has focused on the clinical translation of Raman spectroscopy—involving the development and fabrication of a novel endoscopic Raman probe in conjunction with tumor-targeted Raman nanoparticles for the ultrasensitive detection of precancerous colon lesions.

Jarrett Rosenberg

Jarrett Rosenberg is a Research Scientist and Biostatistician in the Department of Radiology at Stanford University, and has over 25 years of experience in applied research in both academia and industry

Ricky Tong

Ricky Tong received his BA in Chemical Engineering from California Institute of Technology, his PhD in Medical Engineering Medical Physics from Harvard-MIT Division of Health Science and Technology and his MD from Stanford University. He is currently a radiology resident at University of California at San Francisco. His research interest is in the field of drug delivery in tumors.

John Ramunas

John Ramunas is a graduate student in the labs of Helen Blau and Juan Santiago at Stanford University, focused on drug development and delivery. In the imaging field John and Eric Jervis at the University of Waterloo co-invented a novel imaging platform allowing long-term temporal analysis of variegated transgene expression and tracking of single cells in contiguous masses.

Zhuang Liu

Dr. Zhuang Liu received his BS from Peking University (China, 2004) and PhD from Stanford University (USA, 2008). In 2009, Dr. Liu joined the Institute Functional Nano & Soft Materials (FUNSOM) at Soochow University in China as a principal investigator. Dr. Liu’s research has focused on developing functional nanomaterials including carbon nanomaterials, upconversion nanoparticles, and other composite nanostructures for applications in biomedical imaging, drug delivery, cancer phototherapy, and stem cell research. Since 2005 Dr. Liu has authored over 70 peer-reviewed papers (citations > 5000). Dr. Liu has received the MRS silver award (2008) and SCOPUS young researcher award (2012).

Hongjie Dai

Hongjie Dai is the J. G. Jackson and C. J. Wood Professor of Chemistry at Stanford University. Dai’s research is in the area of nanoscience and nanotechnology with novel carbon based materials including carbon nanotubes and graphene. His research bridges chemistry, material science, electronics and biological and biomedical disciplines. His group has developed synthesis of carbon nanotubes, integration into electronic devices, carbon nanotube gas and biological sensors, and quasi-ballistic nanotube field effect transistors. Dai’s group has also exploited the optical properties of carbon nanotubes for biological applications including detection, imaging, drug delivery and photothermal cancer therapy.

Sanjiv Sam Gambhir

Dr. Sanjiv Sam Gambhir is the Virginia & D.K. Ludwig Professor of Cancer Research and the Chair of Radiology at Stanford University School of Medicine. He also heads up the Canary Center at Stanford for Cancer Early Detection. He received his MD/PhD from the UCLA Medical Scientist Training Program. He has over 425 publications in the field and over 40 patents pending or granted. He was elected to the Institute of Medicine of the US National Academies in 2008.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Bryan Ronain Smith, Email: brsmith@stanford.edu.

Cristina Zavaleta, Email: czavalet@stanford.edu.

Jarrett Rosenberg, Email: Jarrett.rosenberg@stanford.edu.

Hongjie Dai, Email: hdai1@stanford.edu.

Sanjiv Sam Gambhir, Email: sgambhir@stanford.edu.

References

- 1.Hahn MA, Singh AK, Sharma P, Brown SC, Moudgil BM. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011;399:3. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kircher MF, de la Zerda A, Jokerst JV, Zavaleta CL, Kempen PJ, Mittra E, et al. Nat Med. 2012;18:829. doi: 10.1038/nm.2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zavaleta CL, Smith BR, Walton I, Doering W, Davis G, Shojaei B, et al. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813327106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cai W, Shin DW, Chen K, Gheysens O, Cao Q, Wang SX, et al. Nano Lett. 2006;6:669. doi: 10.1021/nl052405t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tada H, Higuchi H, Wanatabe TM, Ohuchi N. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1138. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim B, Han G, Toley BJ, Kim CK, Rotello VM, Forbes NS. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5:465. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukumura D, Duda DG, Munn LL, Jain RK. Microcirculation. 2010;17:206. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2010.00029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang X, Peng X, Wang Y, Shin DM, El-Sayed MA, Nie S. ACS nano. 2010;4:5887. doi: 10.1021/nn102055s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirpotin DB, Drummond DC, Shao Y, Shalaby MR, Hong K, Nielsen UB, et al. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6732. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt MM, Wittrup KD. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:2861. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartlett DW, Su H, Hildebrandt IJ, Weber WA, Davis ME. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707461104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De la Zerda A, Zavaleta C, Keren S, Vaithilingam S, Bodapati S, Liu Z, et al. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:557. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang L, Mao H, Wang YA, Cao Z, Peng X, Wang X, et al. Small. 2009;5:235. doi: 10.1002/smll.200800714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maeda H, Fang J, Inutsuka T, Kitamoto Y. Int Immunopharmacol. 2003;3:319. doi: 10.1016/S1567-5769(02)00271-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medarova Z, Pham W, Farrar C, Petkova V, Moore A. Nat Med. 2007;13:372. doi: 10.1038/nm1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li SD, Huang L. Mol Pharm. 2008;5:496. doi: 10.1021/mp800049w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lo Celso C, Fleming HE, Wu JW, Zhao CX, Miake-Lye S, Fujisaki J, et al. Nature. 2009;457:92. doi: 10.1038/nature07434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Z, Tabakman SM, Chen Z, Dai H. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1372. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdollahi A, Folkman J. Drug Resist Update. 2010;13:16. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goel S, Wong AH, Jain RK. Cold Spring Harb perspectives in medicine. 2012;2:a006486. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruggiero A, Villa CH, Holland JP, Sprinkle SR, May C, Lewis JS, et al. Int J Nanomed. 2010;5:783. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S13300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith BR, Cheng Z, De A, Koh AL, Sinclair R, Gambhir SS. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2599. doi: 10.1021/nl080141f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith BR, Cheng Z, De A, Rosenberg J, Gambhir SS. Small. 2010;6:2222. doi: 10.1002/smll.201001022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Z, Cai W, He L, Nakayama N, Chen K, Sun X, et al. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:47. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zavaleta C, de la Zerda A, Liu Z, Keren S, Cheng Z, Schipper M, et al. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2800. doi: 10.1021/nl801362a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang B, Li J, Chang S, Dai M, Ren C, Dai Y, et al. Small. 2012;8:777. doi: 10.1002/smll.201101714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson JT, Welsher K, Tabakman SM, Sherlock SP, Wang H, Luong R, et al. Nano Research. 2010;3:779. doi: 10.1007/s12274-010-0045-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welsher K, Liu Z, Sherlock SP, Robinson JT, Chen Z, Daranciang D, et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 2009;4:773. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tucker-Schwartz JM, Hong T, Colvin DC, Xu Y, Skala MC. Opt Lett. 2012;37:872. doi: 10.1364/OL.37.000872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fabbro C, Ali-Boucetta H, Da Ros T, Kostarelos K, Bianco A, Prato M. Chem Commun. 2012;48:3911. doi: 10.1039/c2cc17995d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schipper ML, Nakayama-Ratchford N, Davis CR, Kam NW, Chu P, Liu Z, et al. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:216. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kostarelos K, Bianco A, Prato M. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:627. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mulder WJ, Strijkers GJ, Habets JW, Bleeker EJ, van der Schaft DW, Storm G, et al. FASEB J. 2005;19:2008–2010. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4145fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brooks PC, Montgomery AM, Rosenfeld M, Reisfeld RA, Hu T, Klier G, et al. Cell. 1994;79:1157. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith BR, Kempen P, Bouley D, Xu A, Liu Z, Melosh N, et al. Nano Lett. 2012;12:3369. doi: 10.1021/nl204175t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugahara KN, Teesalu T, Karmali PP, Kotamraju VR, Agemy L, Girard OM, et al. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:510. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oh P, Borgstrom P, Witkiewicz H, Li Y, Borgstrom BJ, Chrastina A, et al. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:327. doi: 10.1038/nbt1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ballou B, Ernst LA, Andreko S, Harper T, Fitzpatrick JA, Waggoner AS, et al. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:389. doi: 10.1021/bc060261j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benezra M, Penate-Medina O, Zanzonico PB, Schaer D, Ow H, Burns A, et al. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2768. doi: 10.1172/JCI45600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ballou B, Lagerholm BC, Ernst LA, Bruchez MP, Waggoner AS. Bioconjugate Chem. 2004;15:79. doi: 10.1021/bc034153y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Longmire MR, Ogawa M, Hama Y, Kosaka N, Regino CA, Choyke PL, et al. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:1735. doi: 10.1021/bc800140c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao H, Qian J, Cao S, Yang Z, Pang Z, Pan S, et al. Biomaterials. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poselt E, Schmidtke C, Fischer S, Peldschus K, Salamon J, Kloust H, et al. ACS nano. 2012;6:3346. doi: 10.1021/nn300365m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hong H, Gao T, Cai W. Nano Today. 2009;4:252. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hori K, Nishihara M, Yokoyama M. J of Pharm Sci. 2010;99:549. doi: 10.1002/jps.21848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ito K, Smith BR, Parashurama N, Yoon J-K, Song SY, Miething C, et al. Cancer Res. 2012;72:6111. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.