Abstract

Humans have an innate requirement for sleep that is intrinsically governed by circadian and endocrine systems. More recently, reduced sleep duration has gained significant attention for its possible contribution to metabolic dysfunction. Significant evidence suggests that reduced sleep duration may elevate the risk for impaired glucose functioning, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. However, to date, few studies have determined the implications of reduced sleep duration with regard to glucose control during pregnancy. With the high prevalence of overweight and obesity in women of reproductive age, the occurrence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is increasing. GDM results in elevated risk of maternal and fetal complications, as well as increased risk of type 2 diabetes postpartum. Infants born to women with GDM also carry a life-long risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes. The impact of reduced sleep on glucose management during pregnancy has not yet been fully assessed and a paucity of literature currently exits. Herein, we review the association between reduced sleep and impaired carbohydrate metabolism and propose how reduced sleep during pregnancy may result in further dysfunction of the carbohydrate axis. A particular focus will be given to sleep-disordered breathing, as well as GDM-complicated pregnancies. Putative mechanisms of action by which reduced sleep may adversely affect maternal and infant outcomes are also discussed. Finally, we will outline important research questions that need to be addressed.

Keywords: sleep, sleep-disordered breathing, pregnancy, gestational diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) generally develops at approximately 24–28 weeks of gestation1 and is classified as glucose intolerance during pregnancy. This condition is the most common pregnancy-associated disorder and affects 7% of all the US pregnancies.1 However, variation in prevalence among ethnic and racial groups are well documented, with a greater prevalence reported among native American, Asian, Hispanic and African-American populations compared with non-Hispanic Whites.1 During the past two decades, the prevalence of GDM has increased by 10–100% depending on race and ethnicity.2,3 Risk factors for the condition include obesity, advanced maternal age and a family history of diabetes, but Asian populations are thought to possess a specific genetic predisposition for the condition.2

The obesity epidemic is largely responsible for the significant increase in GDM.4 Currently in America, 32% of women of reproductive age are overweight or obese, whereas 17% have a body mass index ≥35 kg m−2.5 As a result, more women are now either overweight or obese before, and throughout, pregnancy. Comorbidities associated with GDM include maternal hypertensive disorders,6 increased risk of cesarean delivery and birth complications, as well as elevated risk of type 2 diabetes postpartum.1 The established comorbidities are not isolated to the expectant mother: infants born to women with GDM are more likely to suffer from macrosomia,7 hypoglycemia and hyperbilirubinemia,8 as well as obesity and type 2 diabetes.9

The rise in GDM has been paralleled by a significant decrease in sleep duration. Over the past 4 decades, sleep duration has declined by 2.3 h with Americans reporting average nightly sleep duration of 6.2 h per night.10 Sleep durations of this length fall below adult recommendations of 7–8 h sleep per night. Recently, significant metabolic and endocrine dysfunction,11–13 as well as increased mortality risk,14–16 have been linked to reduced sleep. The interaction between sleep duration and glucose metabolism has been the focus of much research and it is now recognized that sleep curtailment can adversely impact glycemic control.12,17–19 However, there is a paucity of studies examining the effects of reduced sleep duration on glucose metabolism during pregnancy. This review summarizes the available data on the interaction between sleep duration and quality on glucose metabolism, with a particular emphasis on GDM. The mechanisms by which disturbed sleep may affect glucose metabolism and pregnancy are also discussed.

Sleep and pregnancy

That sleep is altered during pregnancy has been known for quite some time20 and preclinical studies have documented pregnancy, as well as trimester-specific, changes in sleep architecture.21 The first trimester is commonly associated with increased daytime sleepiness,22 as well as total sleep time.23,24 Rising hormone levels during this period may partially account for these changes. Progesterone is known to exert soporific effects,25 and administration of exogenous progesterone has been shown to reduce time to sleep onset and modify sleep architecture, such that more time is spent in non-rapid eye movement sleep.26 Other changes, such as organogenesis, place an additional burden on maternal energy stores and the increase in sleep time may reflect a potential mechanism to conserve energy. Nausea, vomiting, frequent urination20 and insomnia27 may further disrupt sleep increasing the likelihood of daytime somnolence.

During the second trimester, sleep architecture is modified such that less time is spent in stage 3 and 4 non-rapid eye movement sleep and there is a concomitant decrease in rapid eye movement sleep.22 Nocturia accounts for the majority of nighttime awakenings during the second trimester. Compression of the bladder, as a result of increasing uterine size, means more frequent urination.28 Other factors such as heartburn and increasing fetal movements may further fragment sleep. By the third trimester, physical changes cause significant discomfort and can impair the ability to fall asleep, as well as maintain sleep. Backache and itching are common complaints during advanced gestation and the shortest sleep durations are commonly reported during the final trimester, despite more time spent in bed.29

Breathing capacity, particularly during sleep, may also be influenced by fluctuating hormone levels. Increasing levels of estrogen and progesterone induce changes in the respiratory capacity via modifications of smooth muscle tone in the respiratory tract.30 In addition, excess weight before pregnancy can cause additional problems, due to further compression of the thorax. Such changes in respiratory function, whether as a result of rising hormone levels or excess weight, diminish breathing capacity during sleep resulting in increased nighttime awakenings.

Short sleep duration and glucose metabolism—the evidence

Recently, disturbed sleep has been regarded as a potential pathological agent in disorders of carbohydrate metabolism. In the Sleep Heart Health Study, participants with both shorter and longer sleep durations were at elevated risk of impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes31 and, in those with type 2 diabetes, both duration and quality of sleep were found to predict hemoglobin A1c levels.32 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data also indicate that short sleep is associated with increased risk of impaired carbohydrate metabolism33 and reduced sleep has been found to be an independent risk factor for incident diabetes in women.34 However, not all studies are in agreement with this association. The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study found no association between sleep duration and diabetes risk35 and there was no effect of sleep duration on incidence of diabetes in a large prospective study from Sweden.36

Despite the lack of causality offered by the observational literature, experimental data strongly supports the hypothesis that reduced sleep duration impedes euglycemia. Sleep restriction studies demonstrate reduced glucose tolerance in healthy individuals following acute periods of partial sleep deprivation. Spiegel et al.12 reported significant adverse effects of short sleep (4 h per night for 6 nights) in young, healthy men compared with regular sleep (12 h sleep opportunity). Both the acute insulin response and glucose disposal rate were reduced with short sleep compared with regular sleep. Furthermore, elevated post-breakfast glucose was observed with short sleep, but not regular sleep, despite similar insulin levels, indicating significant glucose intolerance with short sleep.12 Nedeltcheva et al.37 documented decreased glucose tolerance with both oral and intravenous glucose tolerance tests following reduced (5.5 h per night for 14 days) but not regular sleep (8.5 h per night) in a group of overweight men and women. Other studies have since reported that short sleep duration also decreases insulin sensitivity compared with longer sleep.38,39

The collective evidence, from observational and intervention studies, indicate that moderate sleep restriction has the capacity to adversely affect glucose homeostasis. Reductions in glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, as a result of sleep deprivation, are of particular concern for individuals with impaired glucose functioning. However, caution should be employed when interpreting the results of these studies. To date, most of the sleep deprivation studies have not matched energy intakes between the short and regular sleep phases;12,37 therefore, participants were in different states of energy balance during both phases. Some evidence suggests that while sleep deprivation does affect glucose and insulin action it may be dependent on energy balance.40

Sleep and gestational diabetes

The effect of sleep on GDM has also been investigated, albeit to a lesser degree as type 2 diabetes (Table 1). Several observational studies suggest that glycemic control may be compromised as a result of short sleep duration (< 7 h per night) in patients with GDM.41,42 One prospective study of 189 nulliparous healthy women reported that short sleep duration (< 7 h per night) was associated with glucose intolerance during the gestational period.41 A range of sleep questionnaires that assessed sleep duration, sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), daytime sleepiness, restless leg syndrome, insomnia and overall sleep quality were administered during the first/second trimester (6–20weeks) and repeated during the third trimester (28–40 weeks). During the first trimester, 28% of the population reported short sleep, whereas by the third trimester this had increased to 40%. Furthermore, short sleep was associated with higher fasting glucose levels during the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), as well as with overt GDM even after for controlling for covariates such as age, race, prepregnancy body mass index and snoring.

Table 1.

Studies examining the relationship between sleep and sleep-disordered breathing during pregnancy with gestational diabetes risk

| Author | Qiu et al.42 | Facco et al.41 | Reutrakul et al.43 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | n = 1290 | n = 189 | n = 169 |

| EGA at assessment | 18 weeks | First assessment: 13.8 weeks | 26.2 weeks |

| Second assessment: 30.2 weeks | |||

| Parity | Nulliparous and multiparous | Nulliparous | Unspecified |

| Method of assessment | Interview | Questionnaire | Questionnaires |

| Measures |

|

|

|

| Outcome |

|

|

|

Abbreviations: EGA, estimated gestational age; GDM, gestational diabetes; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

Qiu et al.42 also explored the association between sleep duration and GDM risk. In early pregnancy (24–28 weeks; n = 1290), sleep duration, as well as snoring, was assessed by interview. Sleep duration was categorized into four categories: ≤4, 5–8, 9, ≥10 and 9 h per night was taken as the reference sleep category. Compared to the reference sleep category both short (≤4 h per night) and long (≥10 h per night) sleep was positively associated with elevated glucose levels following 1 h 50 g OGTT. Short sleepers had the highest glucose levels and GDM was present in 5.3% of study participants. Women with the shortest sleep duration (≤4 h per night) had the greatest risk of developing GDM and the risk was most pronounced in overweight women.42 These associations were independent of age and race/ethnicity. Reutrakul et al.43 used four validated sleep questionnaires (Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS); Berlin questionnaire; Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI); and Nocturia, Nocturnal enuresis and sleep interruption questionnaire) to examine the relationship between sleep disturbance, glucose tolerance and pregnancy outcomes. Pregnant women were enrolled in the study at their scheduled OGTT (1 h 50 g glucose load) at approximately 26 weeks gestation. Of the 169 women enrolled, poor quality sleep was reported in 64% of the study population and excessive daytime sleepiness (41%) and daytime dysfunction (14%) were also reported as significant sleep complaints. In terms of glucose tolerance, 68% of women had normal OGTT results and 26% were diagnosed with GDM. A significant correlation between sleep duration and glucose levels was reported in the GDM group, such that for every hour of reduced sleep there was a 4% increase in glucose levels. Moreover, short sleep and measures of poor sleep quality (ESS, PSQI) were also found to be associated with preterm delivery and greater rate of admission to neonatal intensive care units in both GDM and non-GDM women.43

In addition to the possible effect of sleep duration on glucose metabolism, SDB, namely, obstructive sleep apnea, may also develop during pregnancy. Obstructive sleep apnea is characterized by repetitive episodes of upper pharyngeal obstruction resulting in decreased airflow and hypoxia. These obstructions commonly result in sleep fragmentation and nighttime awakenings. Obesity, in particular excess upper thoracic adiposity, as well as reduced upper airway volume are causative factors in the pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea. Due to the prevalence of overweight and obesity in women of reproductive age, obstructive sleep apnea is becoming increasingly commonplace during pregnancy, yet screening and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea are not routine.

Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with particular morbidities including hypertension, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Both hypertension and glucose abnormalities are present during pregnancy in the form of gestational hypertension, preeclampsia and GDM. Whether obstructive sleep apnea during pregnancy can adversely affect maternal and infant outcomes has not been systematically evaluated. However, several studies report a relationship between frequent snoring, a commonly used proxy measure of obstructive sleep apnea, and impaired glucose metabolism. It should be noted that obstructive sleep apnea is commonly assessed under the umbrella term of SDB; therefore, for the purpose of this review, obstructive sleep apnea will be considered synonymous with SDB. One observational study found that 29% of the study population (n = 169) were at elevated risk of SDB and approximately 20% of women had a combination of elevated SDB risk coupled with short sleep (<7 h per night). Furthermore, women diagnosed with GDM were found to have scores indicative of greater risk of SDB than non-GDM women.43 Similarly, when Facco et al.41 examined the relationship between frequent snoring (≥3 nights per weeks) with GDM risk, they found that approximately 20% of their study population were frequent snorers. Both elevated OGTT results and greater incidence of GDM was found among frequent snorers despite controlling for age, race and prepregnancy body mass index.41 In addition, others have found an approximate twofold increased risk of GDM among patients who snored. This effect was more pronounced (6.9-fold increased risk) in overweight snorers compared with lean snorers.42

Mechanisms of action

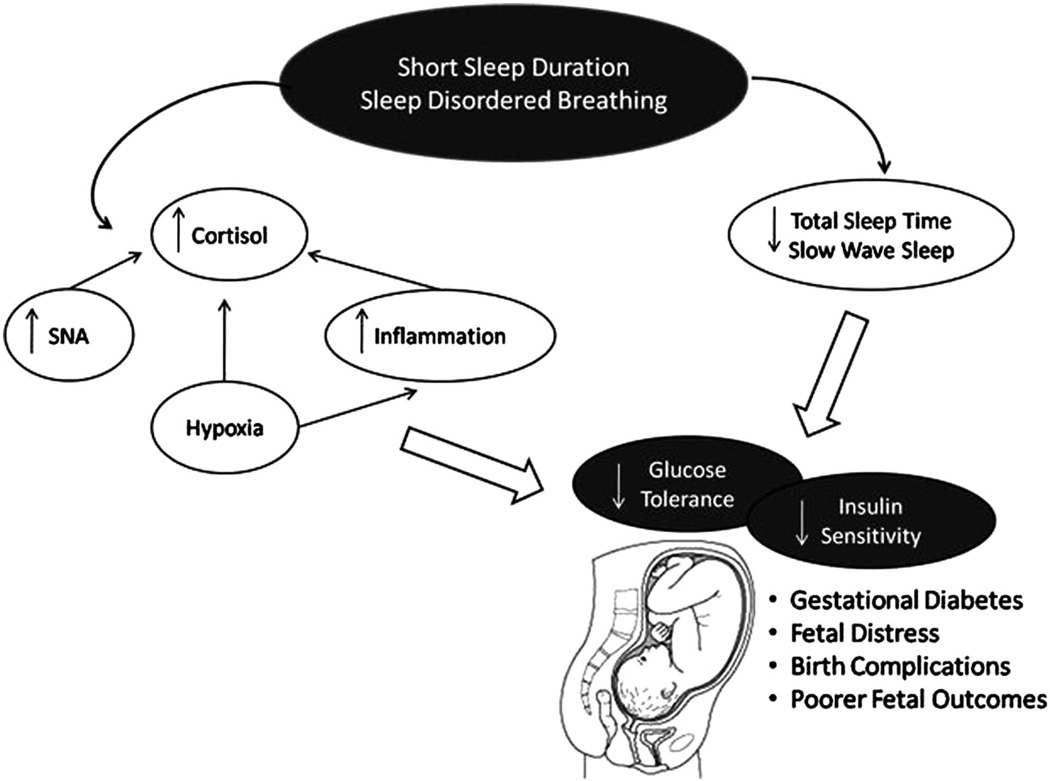

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the relationship between sleep duration and quality, and glycemic control44 (Figure 1). Whether the mechanisms of action differ between pregnant and non-pregnant individuals has yet to be determined. However, the slight reduction in glucose tolerance that accompanies all pregnancies45 may result in the expectant mother being more susceptible to the adverse effects of disturbed sleep on glucose metabolism. One of the primary mechanisms by which short sleep results in impaired glucose functioning is glucose intolerance, which is defined as the inability to maintain euglycemia by metabolizing exogenous glucose via insulin-dependent and non-insulin dependent mechanisms.46 Maintenance of euglycemia is largely dependent on pancreatic beta cells to produce sufficient insulin to ensure glucose disposal. However, in diabetes, both type 2 and gestational, insulin sensitivity is impaired and beta cells are required to increase the level of insulin required for normoglycemia. Sleep can alter the effectiveness of both glucose tolerance12 and insulin sensitivity38,39 and this may be mediated via slow wave sleep (SWS).47 During sleep, particularly stage 3 and 4 SWS, brain glucose utilization is reduced.48 Early nocturnal sleep is also accompanied by a decrease in the stress response systems (sympathetic nervous system49 and the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis (HPA)50). There is also a concomitant reduction in circulating cortisol and epinephrine51 and increase in growth hormone and pro-lactin.52 The reduction in cortisol and elevation in growth hormone are particularly pronounced during SWS.53 These processes are involved in the restorative nature of sleep and it has been shown that a reduction in total sleep time39 or increased awakening during nocturnal sleep54,55 result in reduction in the percent SWS.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of action via which sleep may affect carbohydrate metabolism during pregnancy.

Reduced SWS has, in non-pregnant women and men, been linked to increased risk of impaired glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity,47 presumably as a result of the disruption of the aforementioned hormonal axis. Furthermore, because most ‘normal pregnancies’, those unaffected by metabolic disorders such as GDM, are accompanied with some degree of insulin resistance,45 a reduction in the duration or quality of sleep may increase the severity of insulin resistance and, hence, increase the risk of GDM.

Cortisol may also represent a medium through which altered sleep may disrupt glucose metabolism. However, the effect of sleep on cortisol levels currently remains unclear. Some,11,56 though not all,57,58 experimental studies report disruption of the circadian secretion of cortisol, together with other markers of the stress response system, with partial sleep restriction. However, other studies find no effect.59 One factor that needs to be considered when reviewing the data is whether or not the sleep restriction intervention per se increases stress levels or whether the actual reduction in total sleep time induces altered cortisol secretion. If short sleep duration is responsible for disruption in cortisol levels (that is, elevated evening and night-time cortisol levels) then this may, over time, adversely affect carbohydrate metabolism60,61 decreasing insulin sensitivity and downstream insulin signaling. In addition, obstructive sleep apnea has also been shown to affect the stress response system. Adrenocorticotrophic hormone, a marker of HPA activity, is elevated in patients with obstructive sleep apnea, and continuous positive airway pressure treatment has been shown to effectively reduce circulating hormone levels.62 An elevation in HPA activity, as a result of inadequate or SDB-affected sleep, can increase susceptibility to insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance.

Cortisol and other glucocorticoids alter glucose metabolism via several different mechanisms including decreased translocation of glucose transporter type-4 receptors to the cell surface,63 decreasing insulin release from pancreatic β-cells,64 impairing peripheral glucose uptake and enhancing hepatic gluconeogenesis.65 There are also some mixed reports that cortisol levels can influence insulin receptor binding and downstream insulin signaling.66–68 Alterations in stress markers during pregnancy may increase the likelihood of miscarriage,69 infant developmental delays70 and is likely to contribute to impaired glucose homeostasis in GDM-affected pregnancies.

Sleep duration may also have significant implications for the inflammatory response during pregnancy. Sleep deprivation studies suggest an increased inflammatory response when participants are sleep deprived.71 Increased interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α and C-reactive protein have been shown to be inversely associated with decreasing sleep duration,72–74 and the presence of SDB has also been shown to induce a pro-inflammatory state.75,76 Elevations in these cytokines can disrupt maintenance of normoglycemia by reducing insulin sensitivity and downstream insulin signaling.77 Conditions of impaired glucose control, such as GDM, are also associated with an increased inflammatory response and elevated oxidative stress.78

Cytokines have a significant role during pregnancy with basal levels of certain cytokines present in the amniotic fluid throughout the gestational period.79 During the gestational period, the expression of inflammatory mediators can be viewed as a synchronized balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. This balance may vary with each trimester and disruption of the equilibrium between pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators can adversely affect pregnancy outcomes. As previously mentioned, sleep duration and SDB have both been linked to upregulation of a pro-inflammatory response.72,75 More recently, sleep duration has been shown to alter the inflammatory state during pregnancy29 and some studies have found increased incidence of preterm labor and delivery in women with SDB compared with non-apneic controls.80,81 In addition, a pro-inflammatory state can alter insulin signaling, as well as insulin sensitivity, thereby suggesting another pathway by which sleep can impair glucose control. Moreover, a pro-inflammatory response as a result of sleep loss may increase the risk of preeclampsia,82 a condition increasingly linked to insulin resistance.83

Hypoxia is another pathological hallmark of SDB. Hypoxic conditions, as a result of recurrent apneas and hypopneas, facilitate generation of reactive oxidative species resulting in increased oxidative stress84 and a pro-inflammatory cascade.85 During pregnancy hypoxia has been shown to reduce maternal arterial oxygen saturation giving rise to inadequate blood oxygen for the developing infant, a factor which has been implicated in fetal growth retardation86 and fetal distress.86 Hypoxia can also be attributed to increasing circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines,75,87 which as previously discussed adversely affects pregnancy outcomes.

Changing hormone levels also influence sleep quality via changes in respiratory function. Both estrogen and progesterone alter the smooth muscle tone of the respiratory tract: increasing levels of estrogen induce narrowing of the upper airways resulting in constricted breathing,88 whereas progesterone is believed to increase pharyngeal muscle tone and minute ventilation.30 These effects are exacerbated in overweight or obese women, in whom the risk of SDB, and GDM, is elevated. Excessive adiposity leads to compression of the airways resulting in overt SDB. Although data are inconclusive, it is generally believed that snoring affects pregnant women to a greater extent than non-pregnant women.89,90 Several studies have examined the relationship between snoring, SDB and pregnancy and some,91 though not all,90 report that SDB during pregnancy may adversely affect fetal development. Moreover, the presence of SDB has been shown not only to result in metabolic abnormalities92,93 and daytime dysfunction94 but the repetitive nocturnal arousals also decrease the duration and quality of sleep95 both of which are independently associated with metabolic complications.

As SDB has recently been shown to compromise glucose regulation96 and treatment of SDB with continuous positive airway pressure has demonstrated improvements in glucose control,97 identifying and treating SDB during pregnancy may reduce maternal and infant distress and thereby decrease the incidence of pregnancy-related complications8 attributed to hypoxia. However, rates of screening and diagnosis of SDB are low, and a recent finding illustrates the need for SDB screening, particularly in vulnerable populations such as patients with type 2 diabetes98 and overweight or obese pregnant women.

SUMMARY

Pregnancy is associated with significant hormonal, biochemical and physical alterations. Sleep is also modified by pregnancy and trimester-specific changes. Total sleep time, particularly in the third trimester, is reduced while nocturnal awakenings are increased. Together these changes reflect a shortening of sleep duration and an increase in fragmented sleep. Both short and fragmented sleep have previously been associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes in men and non-pregnant women. Preliminary studies examining the relationship between sleep and GDM suggest that duration and quality of sleep may also contribute to increased risk of GDM. Overweight and obese pregnant women are at elevated risk of SDB, which in non-pregnant study populations has been associated with type 2 diabetes.

Several mechanisms exist by which sleep may modulate impairment in glucose metabolism, yet no study to date has extensively examined the relationship between sleep and GDM. The complexity of the relationship between sleep and glucose metabolism is highlighted by the multiple pathways that are affected by sleep and SDB. The lack of knowledge on how these pathways are affected by sleep is an important area of research that warrants further examination. In our review of the literature, we have identified important unanswered research questions: To what extent does reduced sleep duration affect maternal and infant outcomes? Would increasing sleep duration (either by increased nocturnal sleep or daytime naps) during pregnancy reduce or perhaps prevent the metabolic impairments associated with short sleep? In addition to this, is pregnancy accompanied with specific mechanisms by which disturbed sleep can impair glycemic regulation?

Undiagnosed SDB is common and increased body weight is a primary risk factor. Given the prevalence of overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age, identification of at-risk individuals and subsequent treatment of SDB may be an important issue to consider when monitoring pregnancy, particularly high-risk pregnancies. Whether treatment of SDB can improve maternal and infant outcomes, particularly in relation to GDM, has never been examined. Drawing on the data from non-pregnant populations, partial sleep deprivation, as well as SDB, contribute to significant metabolic abnormalities and increase the risk of glucose dysregulation. These data, combined with the few available epidemiological studies in pregnant women, indicate that much work is needed to unravel the relationship between sleep and sleep-related disorders and GDM.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.A.D.A. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl 1):S88–S90. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caughey AB, Cheng YW, Stotland NE, Washington AE, Escobar GJ. Maternal and paternal race/ethnicity are both associated with gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:616.e1–616.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunsberger M, Rosenberg KD, Donatelle RJ. Racial/ethnic disparities in gestational diabetes mellitus: findings from a population-based survey. Womens Health Issues. 2010;20:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dabelea D, Snell-Bergeon JK, Hartsfield CL, Bischoff KJ, Hamman RF, McDuffie RS. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) over time and by birth cohort: Kaiser Permanente of Colorado GDM Screening Program. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:579–584. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ostlund I, Haglund B, Hanson U. Gestational diabetes and preeclampsia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;113:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donma MM. Macrosomia, top of the iceberg: the charm of underlying factors. Pediatr Int. 2011;53:78–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2010.03198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim C. Gestational diabetes: risks, management, and treatment options. Int J Womens Health. 2010;2:339–351. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S13333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boney CM, Verma A, Tucker R, Vohr BR. Metabolic syndrome in childhood: association with birth weight, maternal obesity, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e290–e296. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Sleep Foundation. 2010 Sleep in America Poll. National Sleep Foundation. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vgontzas AN, Mastorakos G, Bixler EO, Kales A, Gold PW, Chrousos GP. Sleep deprivation effects on the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and growth axes: potential clinical implications. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1999;51:205–215. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiegel K, Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. Lancet. 1999;354:1435–1439. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banks S, Dinges DF. Behavioral and physiological consequences of sleep restriction. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:519–528. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heslop P, Smith GD, Metcalfe C, Macleod J, Hart C. Sleep duration and mortality: The effect of short or long sleep duration on cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in working men and women. Sleep Med. 2002;3:305–314. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(02)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young T, Finn L, Peppard PE, Szklo-Coxe M, Austin D, Nieto FJ, et al. Sleep disordered breathing and mortality: eighteen-year follow-up of the Wisconsin sleep cohort. Sleep. 2008;31:1071–1078. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hublin C, Partinen M, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J. Sleep and mortality: a population-based 22-year follow-up study. Sleep. 2007;30:1245–1253. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.10.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ip MS, Lam B, Ng MM, Lam WK, Tsang KW, Lam KS. Obstructive sleep apnea is independently associated with insulin resistance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:670–676. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.5.2103001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Quantity and quality of sleep and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 33:414–420. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aronsohn RS, Whitmore H, Van Cauter E, Tasali E. Impact of untreated obstructive sleep apnea on glucose control in type 2 diabetes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;181:507–513. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200909-1423OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee KA. Alterations in sleep during pregnancy and postpartum: a review of 30 years of research. Sleep Med Rev. 1998;2:231–242. doi: 10.1016/s1087-0792(98)90010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura M, Zhang SQ, Inoue S. Pregnancy-associated sleep changes in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(Pt 2):R1063–R1069. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.4.R1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee KA, Zaffke ME, McEnany G. Parity and sleep patterns during and after pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:14–18. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00486-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feinsilver SH, Hertz G. Respiration during sleep in pregnancy. Clin Chest Med. 1992;13:637–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunner DP, Munch M, Biedermann K, Huch R, Huch A, Borbely AA. Changes in sleep and sleep electroencephalogram during pregnancy. Sleep. 1994;17:576–582. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.7.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soderpalm AH, Lindsey S, Purdy RH, Hauger R, Wit de H. Administration of progesterone produces mild sedative-like effects in men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:339–354. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santiago JR, Nolledo MS, Kinzler W, Santiago TV. Sleep and sleep disorders in pregnancy. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:396–408. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-5-200103060-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki S, Dennerstein L, Greenwood KM, Armstrong SM, Satohisa E. Sleeping patterns during pregnancy in Japanese women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;15:19–26. doi: 10.3109/01674829409025625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanif S. Frequency and pattern of urinary complaints among pregnant women. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2006;16:514–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okun ML, Coussons-Read ME. Sleep disruption during pregnancy: how does it influence serum cytokines? J Reprod Immunol. 2007;73:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Popovic RM, White DP. Upper airway muscle activity in normal women: influence of hormonal status. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:1055–1062. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.3.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM, Newman AB, Resnick HE, Redline S, Baldwin CM, et al. Association of sleep time with diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:863–867. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.8.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knutson KL, Ryden AM, Mander BA, Van Cauter E. Role of sleep duration and quality in the risk and severity of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1768–1774. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.16.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gangwisch JE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, Buijs RM, Kreier F, Pickering TG, et al. Sleep duration as a risk factor for diabetes incidence in a large U.S. sample. Sleep. 2007;30:1667–1673. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ayas NT, White DP, Al-Delaimy WK, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Speizer FE, et al. A prospective study of self-reported sleep duration and incident diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:380–384. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knutson KL, Van Cauter E, Zee P, Liu K, Lauderdale DS. Cross-sectional associations between measures of sleep and markers of glucose metabolism among subjects with and without diabetes: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Sleep Study 2011. Diabetes Care. 34:1171–1176. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bjorkelund C, Bondyr-Carlsson D, Lapidus L, Lissner L, Mansson J, Skoog I, et al. Sleep disturbances in midlife unrelated to 32-year diabetes incidence: the prospective population study of women in Gothenburg. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2739–2744. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nedeltcheva AV, Kessler L, Imperial J, Penev PD. Exposure to recurrent sleep restriction in the setting of high caloric intake and physical inactivity results in increased insulin resistance and reduced glucose tolerance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3242–3250. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bosy-Westphal A, Hinrichs S, Jauch-Chara K, Hitze B, Later W, Wilms B, et al. Influence of partial sleep deprivation on energy balance and insulin sensitivity in healthy women. Obes Facts. 2008;1:266–273. doi: 10.1159/000158874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buxton OM, Pavlova M, Reid EW, Wang W, Simonson DC, Adler GK. Sleep restriction for 1 week reduces insulin sensitivity in healthy men. Diabetes. 2010;59:2126–2133. doi: 10.2337/db09-0699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kilkus JM, Booth JN, Bromley LE, Darukhanavala AP, Imperial JG, Penev PD. Sleep and eating behavior in adults at risk for type 2 diabetes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;20:112–117. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Facco FL, Grobman WA, Kramer J, Ho KH, Zee PC. Self-reported short sleep duration and frequent snoring in pregnancy: impact on glucose metabolism. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:142 e1–142 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qiu C, Enquobahrie D, Frederick IO, Abetew D, Williams MA. Glucose intolerance and gestational diabetes risk in relation to sleep duration and snoring during pregnancy: a pilot study. BMC Womens Health. 2010;10:17. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-10-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reutrakul S, Zaidi N, Wroblewski K, Kay HH, Ismail M, Ehrmann DA, et al. Sleep disturbances and their relationship to glucose tolerance in pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2454–2457. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spiegel K, Knutson K, Leproult R, Tasali E, Van Cauter E. Sleep loss: a novel risk factor for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:2008–2019. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00660.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Butte NF. Carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in pregnancy: normal compared with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(Suppl):1256 S–1261 S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1256s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davies MJ, Gray IP. Impaired glucose tolerance. BMJ. 1996;312:264–265. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7026.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tasali E, Leproult R, Ehrmann DA, Van Cauter E. Slow-wave sleep and the risk of type 2 diabetes in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1044–1049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706446105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boyle PJ, Scott JC, Krentz AJ, Nagy RJ, Comstock E, Hoffman C. Diminished brain glucose metabolism is a significant determinant for falling rates of systemic glucose utilization during sleep in normal humans. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:529–535. doi: 10.1172/JCI117003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brandenberger G, Ehrhart J, Piquard F, Simon C. Inverse coupling between ultradian oscillations in delta wave activity and heart rate variability during sleep. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:992–996. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00507-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Born J, Fehm HL. Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal activity during human sleep: a coordinating role for the limbic hippocampal system. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabet. 1998;106:153–163. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1211969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dodt C, Breckling U, Derad I, Fehm HL, Born J. Plasma epinephrine and norepinephrine concentrations of healthy humans associated with nighttime sleep and morning arousal. Hypertension. 1997;30(Pt 1):71–76. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steiger A. Sleep and endocrinology. J Intern Med. 2003;254:13–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Born J, Muth S, Fehm HL. The significance of sleep onset and slow wave sleep for nocturnal release of growth hormone (GH) and cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1988;13:233–243. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(88)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin SE, Wraith PK, Deary IJ, Douglas NJ. The effect of nonvisible sleep fragmentation on daytime function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1596–1601. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.5.9154863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Philip P, Stoohs R, Guilleminault C. Sleep fragmentation in normals: a model for sleepiness associated with upper airway resistance syndrome. Sleep. 1994;17:242–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Omisade A, Buxton OM, Rusak B. Impact of acute sleep restriction on cortisol and leptin levels in young women. Physiol Behav. 2010;99:651–656. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schmid SM, Hallschmid M, Jauch-Chara K, Wilms B, Lehnert H, Born J, et al. Disturbed glucoregulatory response to food intake after moderate sleep restriction. Sleep. 2011;34:371–377. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.3.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gonzalez-Ortiz M, Martinez-Abundis E, Balcazar-Munoz BR, Pascoe-Gonzalez S. Effect of sleep deprivation on insulin sensitivity and cortisol concentration in healthy subjects. Diabetes Nutr Metab. 2000;13:80–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmid SM, Hallschmid M, Jauch-Chara K, Bandorf N, Born J, Schultes B. Sleep loss alters basal metabolic hormone secretion and modulates the dynamic counter-regulatory response to hypoglycemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3044–3051. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rizza RA, Mandarino LJ, Gerich JE. Cortisol-induced insulin resistance in man: impaired suppression of glucose production and stimulation of glucose utilization due to a postreceptor detect of insulin action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982;54:131–138. doi: 10.1210/jcem-54-1-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dinneen S, Alzaid A, Miles J, Rizza R. Metabolic effects of the nocturnal rise in cortisol on carbohydrate metabolism in normal humans. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2283–2290. doi: 10.1172/JCI116832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Henley DE, Russell GM, Douthwaite JA, Wood SA, Buchanan F, Gibson R, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation in obstructive sleep apnea: the effect of continuous positive airway pressure therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4234–4242. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weinstein SP, Paquin T, Pritsker A, Haber RS. Glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance: dexamethasone inhibits the activation of glucose transport in rat skeletal muscle by both insulin- and non-insulin-related stimuli. Diabetes. 1995;44:441–445. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Delaunay F, Khan A, Cintra A, Davani B, Ling ZC, Andersson A, et al. Pancreatic beta cells are important targets for the diabetogenic effects of glucocorticoids. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2094–2098. doi: 10.1172/JCI119743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khani S, Tayek JA. Cortisol increases gluconeogenesis in humans: its role in the metabolic syndrome. Clin Sci (Lond) 2001;101:739–747. doi: 10.1042/cs1010739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beck-Nielsen H, De Pirro R, Pedersen O. Prednisone increases the number of insulin receptors on monocytes from normal subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1980;50:1–4. doi: 10.1210/jcem-50-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fantus IG, Ryan J, Hizuka N, Gorden P. The effect of glucocorticoids on the insulin receptor: an in vivo and in vitro study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1981;52:953–960. doi: 10.1210/jcem-52-5-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pagano G, Cavallo-Perin P, Cassader M, Bruno A, Ozzello A, Masciola P, et al. An in vivo and in vitro study of the mechanism of prednisone-induced insulin resistance in healthy subjects. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:1814–1820. doi: 10.1172/JCI111141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nepomnaschy PA, Welch KB, McConnell DS, Low BS, Strassmann BI, England BG. Cortisol levels and very early pregnancy loss in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3938–3942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511183103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huizink AC, Robles de Medina PG, Mulder EJ, Visser GH, Buitelaar JK. Stress during pregnancy is associated with developmental outcome in infancy. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003;44:810–818. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mullington JM, Simpson NS, Meier-Ewert HK, Haack M. Sleep loss and inflammation. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;24:775–784. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meier-Ewert HK, Ridker PM, Rifai N, Regan MM, Price NJ, Dinges DF, et al. Effect of sleep loss on C-reactive protein, an inflammatory marker of cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:678–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haack M, Sanchez E, Mullington JM. Elevated inflammatory markers in response to prolonged sleep restriction are associated with increased pain experience in healthy volunteers. Sleep. 2007;30:1145–1152. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vgontzas AN, Zoumakis E, Bixler EO, Lin HM, Follett H, Kales A, et al. Adverse effects of modest sleep restriction on sleepiness, performance, and inflammatory cytokines. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2119–2126. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Punjabi NM, Beamer BA. C-reactive protein is associated with sleep disordered breathing independent of adiposity. Sleep. 2007;30:29–34. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Larkin EK, Rosen CL, Kirchner HL, Storfer-Isser A, Emancipator JL, Johnson NL, et al. Variation of C-reactive protein levels in adolescents: association with sleep-disordered breathing and sleep duration. Circulation. 2005;111:1978–1984. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161819.76138.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Andrews RC, Walker BR. Glucocorticoids and insulin resistance: old hormones, new targets. Clin Sci (Lond) 1999;96:513–523. doi: 10.1042/cs0960513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Esposito K, Nappo F, Marfella R, Giugliano G, Giugliano F, Ciotola M, et al. Inflammatory cytokine concentrations are acutely increased by hyperglycemia in humans: role of oxidative stress. Circulation. 2002;106:2067–2072. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000034509.14906.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Heikkinen J, Mottonen M, Pulkki K, Lassila O, Alanen A. Cytokine levels in mid-trimester amniotic fluid in normal pregnancy and in the prediction of preeclampsia. Scand J Immunol. 2001;53:310–314. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2001.00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bourjeily G, Raker CA, Chalhoub M, Miller MA. Pregnancy and fetal outcomes of symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing. Eur Respir J. 2010;36:849–855. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00021810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Klebanoff MA, Shiono PH, Rhoads GG. Outcomes of pregnancy in a national sample of resident physicians. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1040–1045. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199010113231506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saito S, Sakai M, Sasaki Y, Tanebe K, Tsuda H, Michimata T. Quantitative analysis of peripheral blood Th0, Th1, Th2 and the Th1:Th2 cell ratio during normal human pregnancy and preeclampsia. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;117:550–555. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rademacher TW, Gumaa K, Scioscia M. Preeclampsia, insulin signalling and immunological dysfunction: a fetal, maternal or placental disorder? J Reprod Immunol. 2007;76:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Prabhakar NR. Sleep apneas: an oxidative stress? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:859–860. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.7.2202030c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gozal D, Kheirandish-Gozal L. Cardiovascular morbidity in obstructive sleep apnea: oxidative stress, inflammation, and much more. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:369–375. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1190PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tapanainen PJ, Bang P, Wilson K, Unterman TG, Vreman HJ, Rosenfeld RG. Maternal hypoxia as a model for intrauterine growth retardation: effects on insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins. Pediatr Res. 1994;36:152–158. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199408000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vgontzas AN, Bixler EO, Chrousos GP. Sleep apnea is a manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9:211–224. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sharma S, Franco R. Sleep and its disorders in pregnancy. WMJ. 2004;103:48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mindell JA, Jacobson BJ. Sleep disturbances during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2000;29:590–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2000.tb02072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Loube DI, Poceta JS, Morales MC, Peacock MD, Mitler MM. Self-reported snoring in pregnancy. Association with fetal outcome. Chest. 1996;109:885–889. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.4.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Franklin KA, Holmgren PA, Jonsson F, Poromaa N, Stenlund H, Svanborg E. Snoring, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and growth retardation of the fetus. Chest. 2000;117:137–141. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Drager LF, Jun JC, Polotsky VY. Metabolic consequences of intermittent hypoxia: Relevance to obstructive sleep apnea. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;24:843–851. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Grunstein RR, Stenlof K, Hedner J, Sjostrom L. Impact of obstructive sleep apnea and sleepiness on metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors in the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19:410–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chasens ER. Obstructive sleep apnea, daytime sleepiness, and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33:475–482. doi: 10.1177/0145721707301492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bianchi MT, Cash SS, Mietus J, Peng CK, Thomas R. Obstructive sleep apnea alters sleep stage transition dynamics. PLoS One. 2004;5:e11356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Punjabi NM, Shahar E, Redline S, Gottlieb DJ, Givelber R, Resnick HE. Sleep-disordered breathing, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:521–530. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Babu AR, Herdegen J, Fogelfeld L, Shott S, Mazzone T. Type 2 diabetes, glycemic control, and continuous positive airway pressure in obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:447–452. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Foster GD, Sanders MH, Millman R, Zammit G, Borradaile KE, Newman AB, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea among obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1017–1019. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]