Abstract

Maternal vitamin D deficiency has been associated with reduced offspring bone mineral accrual. Retinoid-X Receptor-alpha (RXRA) is an essential cofactor in the action of 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D, and RXRA methylation in umbilical cord DNA has been associated with later offspring adiposity. We tested the hypothesis that RXRA methylation in umbilical cord DNA collected at birth is associated with offspring skeletal development, assessed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, in a population-based mother-offspring cohort (Southampton Women’s Survey). Relationships between maternal plasma 25(OH)-vitamin D concentrations and cord RXRA methylation were also investigated. In 230 children aged 4 years, higher % methylation at 4 out of 6 RXRA CpG sites measured was correlated with lower offspring % bone mineral content (%BMC) (β=−0.02 to −0.04%/SD, p=0.002 to 0.043) and BMC corrected for body size (β=−2.1 to −3.4g/SD, p=0.002 to 0.047), with a further site associated with %BMC only. Similar relationships for %BMC were observed in a second independent cohort (n=64). Maternal free 25(OH)-vitamin D index was negatively associated with methylation at one of these RXRA CpG sites (β=−3.3 SD/unit, p=0.03). In addition to the mechanistic insights afforded by associations between maternal free 25(OH)-vitamin D index, RXRA methylation in umbilical cord DNA, and childhood BMC, such epigenetic marks in early life might represent novel biomarkers for adverse bone outcomes in the offspring.

Keywords: Epigenetic, methylation, umbilical cord, RXRA, vitamin D, DXA

Introduction

Poor intrauterine growth is a predictor of later osteoporosis and fracture risk(1;2), and we have previously demonstrated that maternal diet, lifestyle, body build(3;4) and 25(OH)-vitamin D status during pregnancy(5;6) are associated with bone mineral accrual in the offspring. Although it has been suggested that a large proportion of the variance in peak bone mass, achieved in early adulthood, is attributable to heritable fixed genetic factors, several genome-wide association studies have failed to identify SNPs which might explain more than a modest proportion of the overall variation in bone mass in the general population(7;8). Attention is now turning to epigenetic processes, such as DNA methylation, which might provide potential mechanisms to account for relations between transgenerational and perinatal environmental influences and offspring bone development(9). Epigenetic effects on gene expression in the offspring may originate from variations in maternal diet during pregnancy(10); we have previously found evidence that methylation at the promoter region of the Retinoid-X Receptor-Alpha (RXRA, also known as NR2B1) in umbilical cord, is associated with the mother’s diet in early pregnancy and with the offspring’s adiposity in later childhood(11). RXRA is a member of the nuclear hormone superfamily and forms heterodimers with a number of nuclear receptors including the vitamin D receptor, thyroid hormone receptor, GR and PPAR, which are known to influence bone metabolism(12;13). Heterodimerisation with RXRA is critical for both DNA binding and transactivation activity of these receptors. RXRA is also known to play a role in fetal development and in the epigenetic regulation of vitamin D activation(14). Given these critical roles of RXRA in pathways which may influence bone mineral accrual, we reasoned that variation in perinatal epigenetic marking of the RXRA promoter region might be associated with differences in offspring bone size and density in childhood. The aim of this study, therefore, was to investigate the relationships between offspring bone mineral accrual and epigenetic marking in the RXRA promoter region in umbilical cord tissue, at sites previously found to be associated with childhood adiposity. We also investigated whether maternal 25(OH)-vitamin D concentrations might relate to RXRA methylation.

Methods

Participants

The Southampton Women’s Survey (SWS) is a prospective cohort study of 12,583 women aged 20-34 years recruited from the general population(15). Assessments of lifestyle and anthropometry were performed at study entry and then in early (11 weeks) and late (34 weeks) gestation in SWS women who became pregnant. Maternal height was measured with a stadiometer, weight with calibrated digital scales, and skin folds (biceps, triceps, subscapular and suprailiac regions) with Harpenden callipers. The research nurses carrying out the measurements underwent regular assessment and re-training during the study to optimise consistency. The women were asked to characterise their current walking speed into one of five groups (very slow, stroll at an easy pace, normal speed, fairly brisk or fast). The women’s own birth-weight was recorded (by recall, checked by asking her own parents). A subset of 900 offspring aged 4 years was recruited sequentially from the SWS cohort. The mother (or father/guardian) and child were invited to visit the Osteoporosis Centre at Southampton General Hospital for assessment. At this visit written informed consent for a DXA scan was obtained from the mother or father/guardian. The child’s height (using a Leicester height measurer (Seca Ltd, Birmingham, UK) and weight (in underpants only, using calibrated digital scales [Seca Ltd]) were measured. A whole body DXA scan was obtained, using a Hologic Discovery instrument (Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA, USA) in paediatric scan mode. To encourage compliance, a sheet with appropriate coloured cartoons was laid on the couch first; to help reduce movement artefact, the children were shown a suitable DVD cartoon. The total radiation dose for the scans was 4.7 microsieverts for whole body measurement (paediatric scan mode). Thirty-two scans were found to have unacceptable movement artefact so were excluded. The manufacturer’s coefficient of variation (CV) for the instrument was 0.75 % for whole body bone mineral density, and the experimental CV when a spine phantom was repeatedly scanned in the same position 16 times was 0.68%. We studied 230 children selected as having both umbilical cord DNA and DXA bone measurements available at age 4 years.

In the Princess Anne Hospital study, Caucasian women ≥16 years old with singleton pregnancies <17 weeks gestation were recruited; diabetics and hormonally-induced conceptions were excluded. When the children approached 9 years, we wrote to 461 still living locally. 216 (47%) attended a clinic and adiposity was measured using DXA (Lunar DPX-L, GE Lunar, Wisconsin, USA); 64 of these had DNA available from an umbilical cord sample collected at birth and stored at −80°C.

Follow-up of the children and sample collection/analysis was carried out under Institutional Review Board approval (Southampton and SW Hampshire Research Ethics Committee) with written informed consent. Investigations were conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Quantitative DNA methylation analysis

The methods used to select the region of interest and measure RXRA methylation have been described previously(11). In brief, using a commercial tiled oligomer microarray (NimbleGen Systems HG17_min_promoter array, utilising 50-mer oligonucleotides positioned around the transcription start site of 24,134 human genes), we focused initially on 78 candidate genes, and chose 5 genes for further study based on individual oligomers showing evidence of correlation with DXA measurements at age 9 years, biological plausibility and feasibility of designing amplicons suitable for Sequenom analysis. Of the 5 genes chosen, RXRA showed associations between umbilical cord DNA methylation levels and the child’s later adiposity in two independent cohorts(11). Given the common lineage of adipocytes and osteoblasts, we reasoned that such epigenetic marks might also be related to bone development. Genomic DNA was isolated from frozen archived umbilical cord tissue by classical proteinase K digestion and phenol:chloroform extraction. Quantitative analysis of DNA methylation was carried out using the Sequenom MassARRAY Compact System (http://www.sequenom.com), following bisulphate conversion. These methods have been described in detail previously(16). Chromosomal co-ordinates are based on UCSC, human genome March 2006 assembly (hg18).

Statistical analysis

The bone outcomes at 4 years were whole body minus head (for simplicity denoted “whole body” or “WB”) bone area (BA), bone mineral content (BMC), areal bone mineral density (aBMD) and size-corrected bone mineral content (scBMC): BMC adjusted for BA, height and weight (to minimise the effect of body size). Continuous maternal and child characteristics were summarised by mean (SD) or median (IQR) depending on normality. Categorical variables were summarised by percentages. Differences in the continuous variables between boys and girls were tested using t-tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests where appropriate. Linear regression analysis was performed to explore associations between bone outcomes and the epigenetic measurements. For the purpose of this analysis bone outcomes at 4 years were adjusted for sex and the epigenetic variables were transformed to normality using a Fisher-Yates transformation. All statistical analysis was carried out using Stata 12.1 (Statacorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Characteristics of the subjects

There were 230 SWS mother-baby pairs (124 boys) with Sequenom and DXA data. Mean (SD) mother’s age at delivery was 30.4 (3.6) years; 50% were in their first pregnancy and 11% smoked in late pregnancy. Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the mothers, and Table 2, those of the children. The girls had greater bone area and mineral content than the boys, thus the outcomes were adjusted for sex of the child. Compared with mothers of children born to the SWS during the same time frame, but who did not have DXA scans at 4 years, the mothers of children who did have DXA assessments were, on average, slightly older at the birth of their child (mean age 31.2 vs 30.6 years respectively, p=0.007), better educated (24.8% vs 20.6% with higher degree, p=0.002) and smoked less (8.5% vs 17.4% smoked before pregnancy, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the SWS mothers.

| Mean/Median | SD/IQR | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Woman’s age at child’s birth (years) | 30.4 | 3.6 | |

| Height (cm) | 164.2 | 6.2 | |

| Mid-upper arm circumference at 34 weeks (cm) | 29.8 | 3.5 | |

| Pre-pregnancy weight (kg) | 65.4 | 59.4-72.4 | |

| Triceps skinfold at 34 weeks | 19.9 | 16.6-26.1 | |

| Serum 25(OH)-vitamin D at 34 weeks (nmol/l) | 58.5 | 39.0-92.0 | |

| Free 25(OH)-vitamin D index at 34 weeks (units) |

0.1 | 0.1-0.2 | |

| n | |||

| Smoked at 34 weeks (n %) | |||

| No | 197 | 88.7 | |

| Yes | 25 | 11.3 | |

| Parity - two groups (n %) | |||

| 0 | 116 | 50.4 | |

| 1+ | 114 | 49.6 | |

| Educational attainment (n %) | |||

| None | 1 | 0.4 | |

| CSE | 18 | 7.8 | |

| O levels | 68 | 29.6 | |

| A levels | 58 | 25.2 | |

| HND | 21 | 9.1 | |

| Degree | 64 | 27.8 | |

| Walking speed at 34 weeks (n %) | |||

| Very slow | 36 | 16.2 | |

| Stroll at an easy pace | 115 | 51.8 | |

| Normal speed | 60 | 27 | |

| Fairly brisk | 10 | 4.5 | |

| Fast | 1 | 0.5 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of SWS children.

| Boys, n=124 | Girls, n=106 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median/Mean | IQR/SD | Median/Mean | IQR/SD | P diff | |

| At birth | |||||

| Gestational age (weeks) | 39.9 | 38.9-40.7 | 40.4 | 39.4-41.0 | 0.02 |

| RXRA CpG3 (chr9:136355569+) |

20.0 | 7.0-32.0 | 26.5 | 16.0-41.0 | 0.01 |

| RXRA CpG4/5 (chr9:136355593,600+) |

42.0 | 28.5-59.5 | 47.0 | 36.0-60.0 | 0.11 |

| RXRA CpG6 (chr9:136355688+) |

65.0 | 47.5-80.5 | 63.5 | 51.0-77.0 | 0.86 |

| RXRA CpG7 (chr9:136355836+) |

56.0 | 44.0-77.0 | 57.5 | 46.0-72.0 | 0.75 |

| RXRA CpG8 (chr9:136355885+) |

65.0 | 51.0-82.0 | 66.0 | 55.0-82.0 | 0.98 |

| At 4 years | |||||

| Age (years) | 4.1 | 4.1-4.2 | 4.1 | 4.1-4.2 | 0.44 |

| BA (cm2) | 752.4 | 42.9 | 774.9 | 46.5 | <0.001 |

| BMC (g) | 375.6 | 41.0 | 388.1 | 41.9 | 0.02 |

| aBMD (g/cm2) | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.71 |

| scBMC (g) | 375.8 | 17.3 | 374.7 | 17.7 | 0.62 |

| %BMC | 2.6 | 0.2 | 2.6 | 0.2 | 0.10 |

Table shows DXA measures at whole body site. BA = bone area; BMC = bone mineral content; aBMD = areal bone mineral density; scBMC = size-corrected bone mineral content.

RXRA methylation and offspring bone size and density

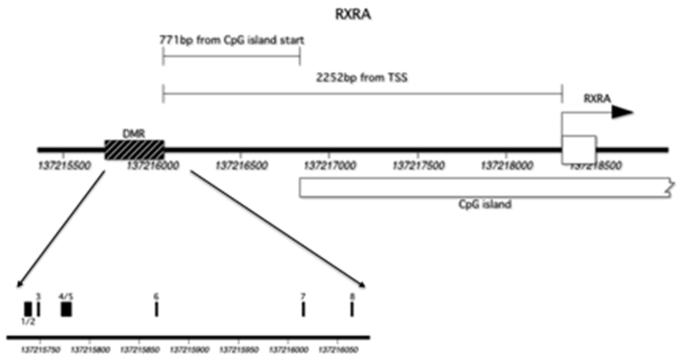

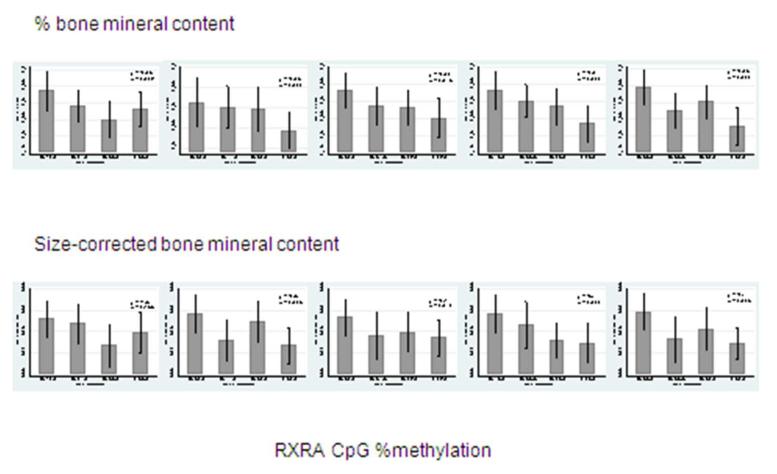

The region of interest contained 13 CpG dinucleotides, however 5 of these could not be assayed due to silent signals or high fragment mass, leaving 8 CpG sites included in this analysis. For ease of interpretation, these have been labeled sequentially GpG1 to GpG8 and their locations are shown in Figure 1. The included RXRA CpG sites demonstrated a wide range of methylation and five were associated with childhood bone indices at 4 years (Tables 2 and 3). These five sites will be denoted RXRA CpG3: chr9:136355569+, RXRA CpG4/5 (chr9:136355593,600+), CpG6: chr9:136355688+, RXRA CpG7 (chr9:136355836+) and RXRA CpG8 (chr9:136355885+). Both size-corrected bone mineral content (scBMC) and percent bone mineral content (%BMC) at the whole body site were negatively and statistically significantly associated with percent methylation at each of these five RXRA sites, except for CpG3, for which the association with scBMC did not achieve statistical significance. These results are summarised in Figure 2. There were no statistically significant relationships between RXRA methylation at the three sites and whole body BA, BMC or aBMD, and no associations were observed between any bone outcome and methylation at the other three RXRA sites [CpG1/2 (chr9:136355556+,560); CpG3 (chr9:136355569+); CpG6 (chr9:136355688+)].

Figure 1.

Location of RXRA CpG sites and transcription start site. (DMR: Differentially methylated region).

Table 3.

Relationships between methylation at sites within RXRA promoter (Fisher-Yates Z-scores) in umbilical cord and sex-adjusted whole body DXA indices in offspring at 4 years.

| Whole body DXA measures: | BA β (cm2/%) |

BMC β (g/%) |

aBMD β (g/cm2 per %) |

scBMC β (g/%) |

%BMC β (%/%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RXRA CpG3 (% methylation) | 2.4 (−3.4, 8.2) | 1.8 (−3.6, 7.2) | 0.000 (−0.000, 0.000) | −1.6 (−3.9, 0.6) | −0.03* (−0.05, −0.00) |

| RXRA CpG4/5 (% methylation) | 2.4 (−3.4, 8.1) | 0.3 (−5.1, 5.6) | −0.002 (−0.01, 0.00) | −2.6* (−4.8, −0.4) | −0.03* (−0.05, 0.00) |

| RXRA CpG6 (% methylation) | 0.4 (−4.8, 5.7) | −1.0 (−5.9, 3.9) | −0.002 (−0.01, 0.00 | −2.1* (−4.1, −0.03) | −0.02* (−0.05, −0.00) |

| RXRA CpG7 (% methylation) | 0.6 (−4.9, 6.1) | −1.4 (−6.5, 3.7) | −0.003 (−0.01, 0.00) | −3.4** (−5.5,−1.3) | −0.04** (−0.06, −0.01) |

| RXRA CpG8 (% methylation) | 0.8 (−4.6,6.1) | −0.3 (−5.3, 4.7) | −0.001 (−0.01, 0.00) | −2.4* (−4.5,−0.3) | −0.03** (−0.06, −0.01) |

Table shows regression coefficient (95% CI).

BA = bone area; BMC = bone mineral content; aBMD = areal bone mineral density; scBMC = size-corrected bone mineral content;

%BMC = percent bone mineral content. RXRA CpG3: chr9:136355569+; RXRA CpG4/5 (chr9:136355593,600+); RXRA CpG6: chr9:136355688+; RXRA CpG7 (chr9:136355836+); RXRA CpG8 (chr9:136355885+).

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Figure 2.

Percent methylation at five umbilical cord RXRA promoter sites and offspring percent and size corrected BMC (g) at 4 years old. [RXRA CpG3: chr9:136355569+; RXRA CpG4/5 (chr9:136355593,600+); RXRA CpG6: chr9:136355688+; RXRA CpG7 (chr9:136355836+); RXRA CpG8 (chr9:136355885+)].

Maternal influences

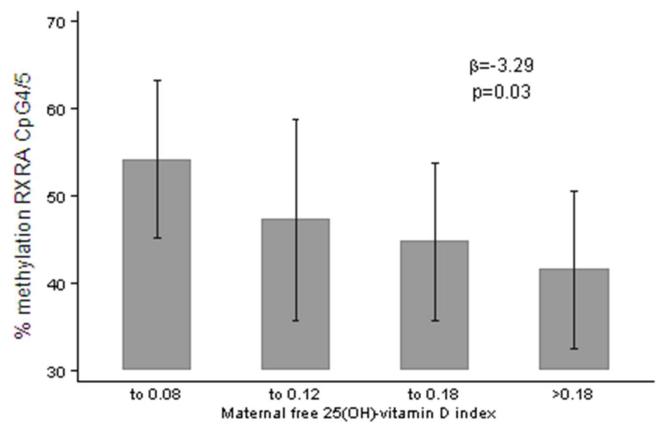

Maternal height and weight pre-pregnancy, and mid-upper arm circumference, smoking and strenuous exercise in late pregnancy, factors previously associated with neonatal bone mass, did not predict RXRA methylation at any site (all p>0.05). In contrast there was a negative, statistically significant relationship between maternal free vitamin D index (ratio of serum 25(OH)-vitamin D to vitamin D binding protein (DBP) concentrations) measured at 34 weeks gestation and percent methylation at RXRA CpG4/5 (β=−3.3 SD/unit, p=0.03), shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Maternal free 25(OH)-vitamin D index, and % methylation at RXRA CpG4/5 (chr9:136355593,600+).

RXRA methylation and birthweight

To investigate whether the associations between RXRA methylation and offspring bone indices might be mediated through an effect on overall size at birth, we examined the relationships between RXRA methylation and birthweight. There was a trend towards a positive association for RXRA CpG4/5 methylation and birthweight (β=46.7g/SD, p=0.11), but no relationships were observed for RXRA CpG3, RXRA CpG6, RXRA CpG7 and RXRA CpG8 (p=0.3, p=0.5, p=0.7 and p=0.8 respectively).

Replication study

We examined these relationships in the Princess Anne Hospital cohort(11), in which we had also previously found associations between RXRA methylation and offspring fat mass. These analyses revealed a consistent pattern of associations in 64 subjects, with higher % methylation at each RXRA site associated with lower %BMC. The effect sizes (β for RXRA CpG3, RXRA CpG4/5, RXRA CpG7 and RXRA CpG8: −0.06, −0.04, −0.04, −0.05 %/SD, respectively) were similar to those observed in the larger SWS cohort, but, in this small sample, did not achieve statistical significance (p=0.22 to 0.32).

Discussion

We have demonstrated in two independent cohorts, and to our knowledge for the first time, that alteration of epigenetic marking of specific regions of the RXRA promoter in umbilical cord predicts childhood percent and size-corrected bone mineral content in the offspring. These associations were present for only five of the eight CpG sites measured, suggesting possible site specificity of methylation; additionally methylation at one of these sites was negatively associated with maternal free 25(OH)-vitamin D index measured at 34 weeks gestation.

We used a prospective cohort with detailed characterisation of mothers and children, using the gold standard DXA technique to assess bone mass. There are, however, several limitations to our study. First, methylation analysis was carried out on samples that had been stored for several years, but our local data suggest that DNA methylation is likely to be stable in tissue stored at −80°C, consistent with findings from another study(17). Moreover, there is no reason to suppose that, if present, sample degradation would have occurred in any but a random distribution across the cohort and therefore should not have led to erroneous associations. Secondly, the methylation sites studied were upstream from the proximal promoter region, but they were located in a region considered to contain positive regulatory elements of transcription and there are several studies reporting promoter regulation by sites at this distance(18;19). We excluded the presence of a SNP at the CpG sites of interest by sequencing, but without genome-wide analysis it is not possible to exclude a genetic effect of distant SNPs which could influence both DNA methylation of a particular sequence and child’s phenotype. Thirdly, we analysed methylation in cells from whole umbilical cord; while it is possible that the differential methylation we observed arose from variation in the proportions of different component cells (for example fibroblasts, epithelial cells) in individual samples our studies show similar methylation in different umbilical cord cell types (unpublished). Fourthly, measurement of bone mineral in children is hampered by their low absolute BMC. However, we used specific paediatric software, and studies of DXA indices compared to ashed mineral content in piglets have confirmed the accuracy of the technique(20). Fifthly, the study cohort was a subset of the SWS, but mothers whose children underwent DXA scanning and those whose children did not were broadly similar: the former were on average slightly older and smoked slightly less. There is no reason to suppose, however, that relationships between RXRA promoter methylation in umbilical cord and childhood bone mineral accrual would differ between these two groups. Finally, the use of DXA does not allow measurement of true volumetric bone density, thus making it difficult to be certain about differential determinants of skeletal size and volumetric density.

Despite its critical role in the nuclear action of a variety of hormones known to influence bone cells, there are scant data directly linking RXRA with bone mineral accrual. We have previously demonstrated an inverse relationship between maternal vitamin D concentration at 34 weeks gestation and offspring bone mass both at birth(21) and in later childhood(22). These associations have been confirmed in another mother-offspring cohort(23). Furthermore, in one study in which umbilical cord calcium concentrations were available the maternal 25(OH)-vitamin D-childhood bone relationships appeared to be, in part, mediated via placental calcium transfer(22). Thus maternal vitamin D concentration might be an important determinant of neonatal bone mineral and of the postnatal skeletal growth trajectory.

In the current study we have demonstrated an inverse association between maternal 25(OH)-vitamin D concentration and methylation at one of the RXRA sites. The relationships between concentrations of 25(OH)-vitamin D and 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D are not straightforward, with the latter regulated tightly by parathyroid hormone and FGF-23, which maintains a constant plasma calcium × phosphorus product, appropriate for bone mineralisation(24). 25(OH)-vitamin D functions as the storage form, but may have the capacity to activate the nuclear receptor complex, albeit with much lower affinity than 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D. In adult life 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D is the predominant biologically active form of vitamin D, converted from 25(OH)-vitamin D by the 1-alpha-(OH)-ase in the kidney, in terms of general circulation, and also by local 1-alpha-(OH)-ase enzymes at the paracrine and autocrine levels(24). 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D enters the nucleus, its action requiring formation of a hetero-dimeric complex between VDR and RXRA(24).

The role of 25(OH)-vitamin D and 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D in the human fetus is unclear; animal work has suggested that different species have varying requirements to enable optimal fetal skeletal mineralisation(25). Additionally 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D has been shown to regulate an active placenta plasma membrane calcium ATP-ase (PMCA) in animals(26). Our previous work has suggested that maternal 25(OH)-vitamin D concentration may be an important determinant of offspring bone development into postnatal life in human pregnancies(21;22), but to our knowledge there are no previous data to suggest that either form of vitamin D may modulate epigenetic marking at the RXRA gene in this context. However, there is evidence that, in adult life, 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D may influence gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms: in animal studies the 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D-VDR-RXRA complex, in combination with other factors such as DNA methyltransferase enzymes, is able to negatively modulate transcription of the 1-alpha-(OH)-ase gene via methylation(14). This provides a negative feedback mechanism, with parathyroid hormone reversing the process and causing demethylation-mediated transcriptional de-repression. This mechanism clearly represents an continuous regulatory process but demonstrates that epigenetic mechanisms may influence action of 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D. Whether such mechanisms might lead to long term methylation change originating in fetal life remains to be elucidated.

Given that RXRA acts as a necessary cofactor for the action of a range of other nuclear receptors, such as thyroid hormone receptor (TR), glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs)(27;28), there are several other mechanistic possibilities linking RXRA methylation to offspring bone development. All of these hormone systems have been demonstrated to influence bone density in adults; indeed circulating cortisol profiles have been linked to growth in early life(29;30), and maternal dietary manipulation in pregnant rats influences methylation of GR(31) and PPAR(32) in the offspring.

We have previously demonstrated that maternal adiposity, smoking, physical activity and parity all predict offspring bone size and geometry(3;4). However none of these factors were associated with methylation of the RXRA promoter in the current study; indeed RXRA methylation appeared to be more strongly related to size-corrected BMC and percent BMC than bone size, suggesting that its effect may relate to volumetric bone density rather than development of the overall skeletal envelope. Whatever the underlying mechanism, our results clearly demonstrate that alteration of epigenetic marking in utero is associated with bone outcomes in the offspring, and observation which, if replicated, might lead to a novel biomarker-based prediction of adverse bone outcomes in children.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that site-specific changes in epigenetic marking within the RXRA promoter in umbilical cord are associated with offspring percent and size-corrected bone mineral content in later childhood. Furthermore, there was an inverse association between free 25(OH)-vitamin D index and methylation at one RXRA site suggesting a possible link between maternal 25(OH)-vitamin D, epigenetic control of RXRA gene expression, and offspring bone development. In addition to the mechanistic insights afforded by these associations, if confirmed, such epigenetic marks in early life might represent novel biomarkers for adverse bone outcomes in the offspring.

Acknowledgements

We thank the mothers and their children who gave us their time, and a team of dedicated research nurses and ancillary staff for their assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Medical Research Council, British Heart Foundation, Arthritis Research UK, National Osteoporosis Society, International Osteoporosis Foundation, Cohen Trust, the NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre, the National Research Centre for Growth and Development (New Zealand) and NIHR Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Unit, University of Oxford. Participants were drawn from a cohort study funded by the Medical Research Council and the Dunhill Medical Trust. We thank Mrs G Strange and Mrs Ruth Fifield for helping to prepare the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures

All authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Reference List

- 1.Cooper C, Eriksson JG, Forsen T, Osmond C, Tuomilehto J, Barker DJ. Maternal height, childhood growth and risk of hip fracture in later life: a longitudinal study. Osteoporos Int JID - 9100105. 2001;12:623–629. doi: 10.1007/s001980170061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Javaid MK, Eriksson JG, Kajantie E, Forsen T, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Cooper C. Growth in childhood predicts hip fracture risk in later life. Osteoporos Int. 2011 Jan;22:69–73. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Godfrey K, Walker-Bone K, Robinson S, Taylor P, Shore S, Wheeler T, Cooper C. Neonatal bone mass: influence of parental birthweight, maternal smoking, body composition, and activity during pregnancy. J Bone Miner Res JID - 8610640. 2001 Sep;16:1694–1703. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.9.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvey NC, Javaid MK, Arden NK, Poole JR, Crozier SR, Robinson SM, Inskip HM, Godfrey KM, Dennison EM, Cooper C. Maternal predictors of neonatal bone size and geometry: the Southampton Women’s Survey. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. 2010 Feb;1:35–41. doi: 10.1017/S2040174409990055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Javaid MK, Crozier SR, Harvey NC, Gale CR, Dennison EM, Boucher BJ, Arden NK, Godfrey KM, Cooper C. Maternal vitamin D status during pregnancy and childhood bone mass at age 9 years: a longitudinal study. Lancet. 2006 Jan 7;367:36–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67922-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harvey NC, Javaid MK, Poole JR, Taylor P, Robinson SM, Inskip HM, Godfrey KM, Cooper C, Dennison EM. Paternal skeletal size predicts intrauterine bone mineral accrual. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 May;93:1676–1681. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rivadeneira F, Styrkarsdottir U, Estrada K, Halldorsson BV, Hsu YH, Richards JB, Zillikens MC, Kavvoura FK, Amin N, Aulchenko YS, Cupples LA, Deloukas P, Demissie S, Grundberg E, Hofman A, Kong A, Karasik D, van Meurs JB, Oostra B, Pastinen T, Pols HA, Sigurdsson G, Soranzo N, Thorleifsson G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Williams FM, Wilson SG, Zhou Y, Ralston SH, van Duijn CM, Spector T, Kiel DP, Stefansson K, Ioannidis JP, Uitterlinden AG. Twenty bone-mineral-density loci identified by large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2009 Nov;41:1199–1206. doi: 10.1038/ng.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estrada K, Styrkarsdottir U, Evangelou E, Hsu YH, Duncan EL, Ntzani EE, Oei L, Albagha OM, Amin N, Kemp JP, Koller DL, Li G, Liu CT, Minster RL, Moayyeri A, Vandenput L, Willner D, Xiao SM, Yerges-Armstrong LM, Zheng HF, Alonso N, Eriksson J, Kammerer CM, Kaptoge SK, Leo PJ, Thorleifsson G, Wilson SG, Wilson JF, Aalto V, Alen M, Aragaki AK, Aspelund T, Center JR, Dailiana Z, Duggan DJ, Garcia M, Garcia-Giralt N, Giroux S, Hallmans G, Hocking LJ, Husted LB, Jameson KA, Khusainova R, Kim GS, Kooperberg C, Koromila T, Kruk M, Laaksonen M, LaCroix AZ, Lee SH, Leung PC, Lewis JR, Masi L, Mencej-Bedrac S, Nguyen TV, Nogues X, Patel MS, Prezelj J, Rose LM, Scollen S, Siggeirsdottir K, Smith AV, Svensson O, Trompet S, Trummer O, van Schoor NM, Woo J, Zhu K, Balcells S, Brandi ML, Buckley BM, Cheng S, Christiansen C, Cooper C, Dedoussis G, Ford I, Frost M, Goltzman D, Gonzalez-Macias J, Kahonen M, Karlsson M, Khusnutdinova E, Koh JM, Kollia P, Langdahl BL, Leslie WD, Lips P, Ljunggren O, Lorenc RS, Marc J, Mellstrom D, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Olmos JM, Pettersson-Kymmer U, Reid DM, Riancho JA, Ridker PM, Rousseau F, Lagboom PE, Tang NL, Urreizti R, Van HW, Viikari J, Zarrabeitia MT, Aulchenko YS, Castano-Betancourt M, Grundberg E, Herrera L, Ingvarsson T, Johannsdottir H, Kwan T, Li R, Luben R, Medina-Gomez C, Th PS, Reppe S, Rotter JI, Sigurdsson G, van Meurs JB, Verlaan D, Williams FM, Wood AR, Zhou Y, Gautvik KM, Pastinen T, Raychaudhuri S, Cauley JA, Chasman DI, Clark GR, Cummings SR, Danoy P, Dennison EM, Eastell R, Eisman JA, Gudnason V, Hofman A, Jackson RD, Jones G, Jukema JW, Khaw KT, Lehtimaki T, Liu Y, Lorentzon M, McCloskey E, Mitchell BD, Nandakumar K, Nicholson GC, Oostra BA, Peacock M, Pols HA, Prince RL, Raitakari O, Reid IR, Robbins J, Sambrook PN, Sham PC, Shuldiner AR, Tylavsky FA, van Duijn CM, Wareham NJ, Cupples LA, Econs MJ, Evans DM, Harris TB, Kung AW, Psaty BM, Reeve J, Spector TD, Streeten EA, Zillikens MC, Thorsteinsdottir U, Ohlsson C, Karasik D, Richards JB, Brown MA, Stefansson K, Uitterlinden AG, Ralston SH, Ioannidis JP, Kiel DP, Rivadeneira F. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 56 bone mineral density loci and reveals 14 loci associated with risk of fracture. Nat Genet. 2012;44:491–501. doi: 10.1038/ng.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, Thornburg KL. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jul 3;359:61–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burdge GC, Lillycrop KA, Phillips ES, Slater-Jefferies JL, Jackson AA, Hanson MA. Folic acid supplementation during the juvenile-pubertal period in rats modifies the phenotype and epigenotype induced by prenatal nutrition. J Nutr. 2009 Jun;139:1054–1060. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.104653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Godfrey KM, Sheppard A, Gluckman PD, Lillycrop KA, Burdge GC, McLean C, Rodford J, Slater-Jefferies JL, Garratt ES, Crozier SR, Emerald BS, Gale CR, Inskip HM, Cooper C, Hanson MA. Epigenetic gene promoter methylation at birth is associated with child’s later adiposity. Diabetes. 2011 doi: 10.2337/db10-0979. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li G, Yin W, Chamberlain R, Hewett-Emmett D, Roberts JN, Yang X, Lippman SM, Clifford JL. Identification and characterization of the human retinoid X receptor alpha gene promoter. Gene. 2006 May 10;372:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahuja HS, Szanto A, Nagy L, Davies PJ. The retinoid X receptor and its ligands: versatile regulators of metabolic function, cell differentiation and cell death. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2003 Jan;17:29–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeyama K, Kato S. The vitamin D3 1alpha-hydroxylase gene and its regulation by active vitamin D3. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2011;75:208–213. doi: 10.1271/bbb.100684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inskip HM, Godfrey KM, Robinson SM, Law CM, Barker DJ, Cooper C. Cohort profile: The Southampton Women’s Survey. Int J Epidemiol. 2005 Sep 29; doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey NC, Lillycrop KA, Garratt E, Sheppard A, McLean C, Burdge G, Slater-Jefferies J, Rodford J, Crozier S, Inskip H, Emerald BS, Gale CR, Hanson M, Gluckman P, Godfrey K, Cooper C. Evaluation of methylation status of the eNOS promoter at birth in relation to childhood bone mineral content. Calcif Tissue Int. 2012 Feb;90:120–127. doi: 10.1007/s00223-011-9554-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talens RP, Boomsma DI, Tobi EW, Kremer D, Jukema JW, Willemsen G, Putter H, Slagboom PE, Heijmans BT. Variation, patterns, and temporal stability of DNA methylation: considerations for epigenetic epidemiology. FASEB J. 2010 Sep;24:3135–3144. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-150490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kranz AL, Eils R, Konig R. Enhancers regulate progression of development in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011 Jul 23; doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park JH, Stoffers DA, Nicholls RD, Simmons RA. Development of type 2 diabetes following intrauterine growth retardation in rats is associated with progressive epigenetic silencing of Pdx1. J Clin Invest. 2008 Jun;118:2316–2324. doi: 10.1172/JCI33655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunton JA, Weiler HA, Atkinson SA. Improvement in the accuracy of dual energy x-ray absorptiometry for whole body and regional analysis of body composition: validation using piglets and methodologic considerations in infants. Pediatr Res. 1997 Apr;41:590–596. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199704000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harvey NC, Javaid MK, Poole JR, Taylor P, Robinson SM, Inskip HM, Godfrey KM, Cooper C, Dennison EM. Paternal skeletal size predicts intrauterine bone mineral accrual. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 May;93:1676–1681. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Javaid MK, Crozier SR, Harvey NC, Gale CR, Dennison EM, Boucher BJ, Arden NK, Godfrey KM, Cooper C. Maternal vitamin D status during pregnancy and childhood bone mass at age 9 years: a longitudinal study. Lancet. 2006 Jan 7;367:36–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67922-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sayers A, Tobias JH. Estimated maternal ultraviolet B exposure levels in pregnancy influence skeletal development of the child. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Mar;94:765–771. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holick MF, Garabedian M. Vitamin D: Photobiology, Metabolism, Mechanisms of Action, and Clinical Applications. In: Favus MJ, editor. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Mineral Metabolism. ASBMR; Chicago: 2006. pp. 106–114. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovacs CS, Kronenberg HM. Skeletal physiology: Pregnancy and Lactation. In: Favus MJ, editor. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. 6th ed. ASBMR; Chicago: 2006. pp. 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kip SN, Strehler EE. Vitamin D3 upregulates plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase expression and potentiates apico-basal Ca2+ flux in MDCK cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004 Feb;286:F363–F369. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00076.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li G, Yin W, Chamberlain R, Hewett-Emmett D, Roberts JN, Yang X, Lippman SM, Clifford JL. Identification and characterization of the human retinoid X receptor alpha gene promoter. Gene. 2006 May 10;372:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahuja HS, Szanto A, Nagy L, Davies PJ. The retinoid X receptor and its ligands: versatile regulators of metabolic function, cell differentiation and cell death. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2003 Jan;17:29–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dennison E, Hindmarsh P, Fall C, Kellingray S, Barker D, Phillips D, Cooper C. Profiles of endogenous circulating cortisol and bone mineral density in healthy elderly men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999 Sep;84:3058–3063. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.9.5964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fall CH, Dennison E, Cooper C, Pringle J, Kellingray SD, Hindmarsh P. Does birth weight predict adult serum cortisol concentrations? Twenty-four-hour profiles in the United kingdom 1920-1930 Hertfordshire Birth Cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002 May;87:2001–2007. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lillycrop KA, Slater-Jefferies JL, Hanson MA, Godfrey KM, Jackson AA, Burdge GC. Induction of altered epigenetic regulation of the hepatic glucocorticoid receptor in the offspring of rats fed a protein-restricted diet during pregnancy suggests that reduced DNA methyltransferase-1 expression is involved in impaired DNA methylation and changes in histone modifications. Br J Nutr. 2007 Jun;97:1064–1073. doi: 10.1017/S000711450769196X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lillycrop KA, Phillips ES, Torrens C, Hanson MA, Jackson AA, Burdge GC. Feeding pregnant rats a protein-restricted diet persistently alters the methylation of specific cytosines in the hepatic PPAR alpha promoter of the offspring. Br J Nutr. 2008 Aug;100:278–282. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507894438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]