Abstract

Aims

To describe the retention of rural women in the Rural Breast Cancer Survivors (RBCS) Intervention.

Background

Few studies describe strategies and procedures for retention of participants enrolled in cancer research. Fewer studies focus on underserved rural cancer survivors.

Methods

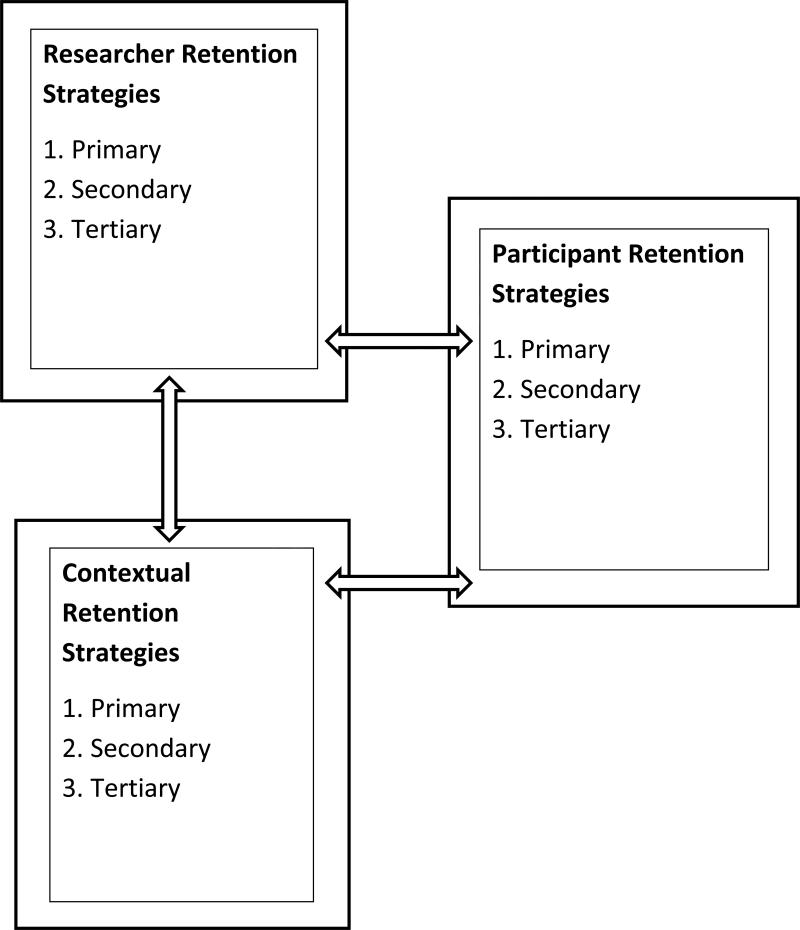

A descriptive design was used. A conceptual model of retention based on three factors: researcher, participant, and context with primary, secondary, and tertiary strategies was used to unify the data.

Results

432 women enrolled in the RBCS study, of which 332 (77%) were retained and completed the 12 month study. Favorable retention strategies included: run-in period, persistent attempts to re-contact hard to reach, recruitment and enrollment tracking database, and a trusting and supportive relationship with the research nurse.

Conclusion

A conceptual model of retention with differential strategies can maintain participant retention in a longitudinal research study.

Keywords: rural, breast cancer, survivors, retention, attrition

Retention of underserved and minority populations in cancer control research has been historically low (Angell et al., 2003). Underserved populations include rural, elder, women, and the poor who carry an unequal burden of disease (Angell et al., 2003; Demark-Wahnefried, Bowen, Jabson, &Paskett, 2011). In the United States, there are more than 13 million cancer survivors, of which, about 17% live in rural areas. Thus, given the large number of cancer survivors, an understanding of the retention of rural survivors is greatly needed to decrease the burden of disease.

Few researchers report retention strategies in clinical research, even less report the success or failure in retaining participants (Robinson, Dennison, Wayman, Provonost, & Needham, 2007). In a systematic review of subject retention in 21 studies, Robinson et al. (2007) examined the types and number of retention strategies reported by investigators. The most common strategies reported were: contact and scheduling methods, visit characteristics to minimize participant burden, and financial incentives. Further, they found that the range of retention strategies was 3-42 (median: 17), and that the larger the number of retention methods, the greater participant retention over time.

Yancey, Ortega, & Kumanyika, (2006b) noted that intensive follow-up and continued contact with research participants were important factors to improve retention. Further, the investigators found that social support was a vital element particularly in retention of minority participants. Janson, Alioto, Boushey, & Asthma Clinical Trials Network (2001) recommend provision of encouragement and attention, and a having a flexible schedule to reduce attrition. Trust and support are also vital to retaining study participants over time. For example, Penckofer, Byrn, Mumby, & Ferrans (2011) identified that the relationship of the participant to study personnel may be the most important factor in subject retention. Fayter, McDaid, & Eastwood (2007) noted that in cancer studies, self-motivation and altruism were cited by participants as the basis to remain committed to the study.

Minimizing barriers to research access strengthens retention. Kroenke et al., (2010) examined the effect of Telecare intervention on pain and depression among cancer survivors, and found that telephone-based intervention was both feasible and produced improvement in symptoms among rural participants. Similarly, Ka'opua, Park, Ward, & Braun, (2011) found that partnership with churches in rural areas was beneficial to retaining participants in an intervention to promote screening for breast cancer.

Given the paucity of retention strategies reported, particularly among underserved rural and older research participants, the purpose of this paper is to (a) describe the overall retention among rural breast cancer survivors enrolled in the Rural Breast Cancer Survivors Intervention (RBCS) study; (b) describe the number and types of retention strategies used; (c) identify the success of retention strategies; and (d) explore future challenges to retention among rural breast cancer survivors in cancer control research.

RBCS Study Aims and Design

The RBCS is a population-based randomized behavioral trial investigating the effect of a telephone-mediated psychoeducational and support intervention (authors, under review). Primary endpoints were quality of life and cancer surveillance outcomes. Recruitment consisted of approved use of a population-based cancer registry data to identify potential participants combined with structured attempts to engage rural breast cancer survivors. In an effort to reduce access barriers to study participation, a telephone-based format was used for intervention delivery by a trained research nurse. The RBCS was designed for twelve months of study participation with random assignment to either: (1) the Support and Early Education Intervention (Experimental) or (2) the Support and Delayed Education Intervention (Wait Control) group.

After completing initial baseline measures, participants in the Support and Early Education Intervention group received three one-on-one survivorship education sessions delivered via telephone by a research nurse. The sessions were reinforced with written education materials. Thereafter, the research nurses contacted participants monthly for telephone follow-up and reinforcement of education and support. Participants assigned to the Support and Delayed Education Intervention group received six monthly telephone support calls starting in the first month after enrollment. In the seventh month, participants received three one-on-one survivorship educational sessions via telephone supplemented by written educational materials. All participants completed data collection measures at 3 month intervals (Month 3, 6, 9, and 12).

Conceptual Model of Retention

The authors developed a conceptual model of retention based on the works of Goodman & Blum, and Shumaker, Dugan, & Bowen (Goodman & Blum, 1996; Shumaker, Dugan, & Bowen 2000). Goodman (1996) posits that research retention and attrition are influenced by three major factors: researcher, participant, and contextual. Shumaker et al. (2000) identified three levels to enhance retention in a randomized study: primary prevention (i.e., careful screening and enrolling of RCT participants and prevention prior to any lagging or attrition); secondary prevention (i.e., early identification of ‘slippage’ or non-adherence to protocol) and tertiary prevention (i.e., recovering participants who have dropped out or non-adhere for long period) to the study. The conceptual model of retention is illustrated in Figure 1 and will be used to illustrate the interrelationship among retention factors across primary, secondary, and tertiary retention strategies in the RBCS.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Research Retention (Copyright 2103, The Authors)

RBCS Retention Protocol

The RBCS was based on a specific protocol for recruitment, and a separate, but related detailed study retention protocol; both protocols were guided by the conceptual model of retention. Table 1 summarizes the 18 researcher retention strategies, 20 participant retention strategies, and 2 main contextual strategies for a total of 40 retention strategies in the RBCS.

Table 1.

Description of RBCS Retention Strategies and Characteristics

| Researcher Retention Strategies |

Primary Prevention 1. Develop structured retention protocol 2. Training of research staff in protocol 3. Frequent clinical and research team meetings 4. Allow for a run-in period between interest and baseline measures 5. Contact interested participants within 5 days of notification of interest 6. Schedule first call for at least 15 minutes to allow for discussion 7. Schedule second call back to allow for answering of questions and discussion 8. Send separate written informed consent 9. Provide time for questions after initial consent 10. Describe mutual expectations 11. Call promptly for scheduled visits |

Secondary Prevention 1. Call back 15 minutes after first failed attempt to contact 2. Leave voice message or email if no response to second attempt 3. Follow-up missed appointments with at least 3 telephone calls or emails at different times of day |

Tertiary Prevention 1. Send a recontact letter with study logo, signed by the research nurse after 3 failed attempts to contact by phone or email 2. Three follow-up phone calls made to the initial recontact letter 3. Send a recontact letter with an Option to Withdraw after three failed attempts to contact after first letter 4. Administrative withdrawal of participants one year after baseline completion |

| Participant Retention Strategies |

Primary Prevention 1. Clinicians assigned a set of participants to work with throughout the year 2. Encouraged trusting relationships between researcher and participant 3. Schedule calls at a convenient time for researcher and participant 4. Use email if participant allows 5. Frequent/monthly contact throughout the study 6. Provide reminders as requested 7. Provide a written schedule for participants in their materials 8. Offer flexible scheduling and breaks if needed during telephone calls 9. Be mindful of participant emotions during the call 10. Provide tailored education and support 11. Provide written materials to reinforce education and support 12. Provide financial incentive after completion |

Secondary Prevention 1. Provide the option for reminder calls/emails/cards for participant who is lagging 2. Reinforce the time commitment of the study 3. Reinforce the roles and responsibilities of the research participant 4.Offer flexible scheduling including breaking visits into smaller blocks of time, changing the time of the scheduled appointment 5. Send a handwritten note or card to participants experiencing unforeseen life circumstances (i.e., weddings, births, deaths, cancer recurrence) |

Tertiary Prevention 1. Use of email, telephone, and mail to reach lagging or difficult to reach participants 2. Continued tracking of the time since participant enrollment 3. Provide support and understanding even if participant is difficult to reach or not able to complete study measures |

| Contextual Retention Strategies |

Primary Prevention 1. Development and use of Recruitment Tracking database 2. Development and use of Enrollment Tracking database |

Secondary Prevention 1. Continued utilization of the Recruitment and Enrollment Tracking databases |

Tertiary Prevention 1. Continued utilization of the Recruitment and Enrollment Tracking databases |

Copyright 2013, the Author

RBCS Researcher Retention Strategies

Primary prevention procedures (see Table 1) consisted of (a) structured participant retention protocol designed prior to the start of the RBCS; (b) training of research nurses and staff in the protocol; (c) monthly clinical and research team meetings; and (d) a run-in period between initial interest and baseline during which time participants were able to think through their decision and ultimately decide to participate or withdraw consent (Ulmer, Robinaugh, Friedberg, Lipsitz, & Natarajan, 2008).

Secondary prevention strategies were aimed at early identification of participants who were or could potentially be at risk for drop out and non-adherence to the study protocol. During monthly research team meetings, retention data were discussed for each participant by month and time. Concerns about specific participants who lagged in maintaining monthly contact and/or data collection were discussed. Once participants who lagged were identified, added strategies to regain momentum were included (see Table 1).

Tertiary prevention researcher strategies aimed to recover participants who lagged for more than four weeks despite persistent and numerous contact attempts. Tertiary prevention researcher strategies included multiple attempts at re-contact by various methods (see Table 1).

RBCS Participant Retention Strategies

Primary prevention participant strategies focused on participant adherence to the protocol. After enrollment, each participant received a tip sheet with bulleted information about their roles and responsibilities during the 12 month study period. The tip sheet included instruction about: reading the survivorship education materials, scheduling regular telephone contact, making time to be away from distractions while on the telephone, and being prepared and engaged for the monthly discussions. The research nurses emphasized and reinforced the time commitment for the 12 month period, and gave voice and encouragement for survivors to reconsider participation if they could not commit to the time despite their interest in the study (see Table 1).

Secondary prevention strategies mirror those identified in Table 1 under researcher secondary prevention. In addition, if the participant gave a reason for a missed visit such as a family emergency (i.e., birth, death, and wedding) or other events, the research nurse sent a personal handwritten note of concern. After enrollment, regular monthly contacts were scheduled at least one month in advance with attention to a time that was convenient and consistent with the participant's personal, family, work, and/or social schedule. A reminder telephone call or email was made to enhance study adherence.

For participants who were unavailable and unreachable at the time of scheduled study appointments, the research nurse made multiple attempts to contact the participants promptly on the day of the scheduled appointment, and continued to follow-up when the participant did not answer or return the phone call. Participants were given a toll-free number to the research office and the office phone number and email to contact their research nurses. Additionally, the time commitment and the roles and responsibilities of the study were reinforced.

Tertiary prevention strategies were aimed at reconnecting with participants who were lost to follow-up (see Table 1). Primarily the use of repeated telephone calls and letters were used for participants who continued to lag after multiple attempt efforts to contact. The time since enrollment of participants was continually and thoroughly tracked throughout their time in the study by the research nurses and data manager. Support and understanding were provided for participants who were difficult to reach or had decided to not complete the data collection measures.

RBCS Contextual Retention Strategies

Contextual retention strategies (see Table 1) are defined as those strategies that are specific to the research enterprise. The researchers developed two Access databases. First, the Recruitment Tracking Database was developed to track the progress of participant recruitment and enrollment using an Access database. This database contains 234 fields with contact information about interested participants (e.g., name, current address, potential new address and/or second contact address, cell and telephone numbers, and the best time to call). A second section of the database allowed the research nurses to track the number of times each participant was contacted, the outcomes of the contact (i.e., scheduled or enrolled), and all subsequent contact times and types of contact. Information about specific mailed contacts with the participant (e.g., unable to reach letters, options to withdraw letters) and dates of receipt (i.e., informed consent and other communication) were also recorded in the Recruitment Tracking Database.

Similar to that for recruitment, the Enrollment Tracking Database was developed to track the progress of participant enrollment. This database contains 130 fields with the following data: participant contact information, name of emergency contact (i.e., name, address, telephone number, and relationship to the participant). Dates and times of pertinent communication with participants (i.e., dates when study materials were sent, baseline materials, study materials, missed appointments, dates, status, length of times, and notes for each scheduled and completed appointment). Information about the length of time between scheduled visits and dates of missed appointments were also recorded.

Both databases allowed the team to track participants who were not progressing in a timely manner. Furthermore, data were coded into a CONSORT by the data manager as a visual and fluid picture of the matriculation and attrition of participants through the study (Moher et al., 2012).

Results and Findings

Participant Characteristics

Baseline socio-demographic and treatment characteristics were tabulated and demographic analysis was conducted using SAS v9.3 statistical software (SASInstitute, 2008; Computing, 2008). A total of 432 rural breast cancer survivors enrolled in the RBCS. Table 2 shows the socio-demographic and treatment characteristics. The typical participant was Caucasian, 63.1 years of age, married or partnered, and retired. About 33.5% had at least high school or trade school education, and 33.5% reported annual household incomes less than $40,000. The average time since diagnosis to study entry was 25.6 months (SD=7.9) with an average time since completion of primary breast cancer treatment of 18.8 months (SD=7.9).

Table 2.

Characteristics and Treatment Characteristics of RBCS Participants (N=432)

| Group Assignment |

| Wait Control (n=217, 50.2%) |

| Experimental (n=215, 49.8%) |

|

Age Range: 35-90 years (M=63.1, SD=10.5) |

| Race |

| Caucasian (n=408, 94.4%) |

| African-American (n=16, 3.7%) |

| Native American (n=3, 0.7%) |

| Asian (n=1, 0.2%) |

| Other (n=4, 0.9%) |

| Annual Income |

| $10,000 or less (n=25, 5.8%) |

| $11,001 to $20,000 (n=46, 10.7%) |

| $21,001 to $30,000 (n=60, 13.9%) |

| $31,001 to $40,000 (n=34, 7.9%) |

| $41,001 to $50,000 (n=46, 10.6%) |

| Greater than $51,000 (n=157, 36.3%) |

| No response (n=64, 14.8%) |

| Marital Status |

| Never married (n=10, 2.3%) |

| Married (n=298, 69%) |

| Living with Partner (n=17, 4%) |

| Separated (n=4, 0.9%) |

| Divorced (n=51, 11.8%) |

| Widowed (n=52, 12 %) |

| Employment |

| Full-time (n=111, 25.7%) |

| Part-time (n=62, 14.4%) |

| Retired (n=196, 45.4%) |

| Homemaker (n=24, 5.5%) |

| Unemployed (n=17, 3.9%) |

| Other (n=22, 5.1%) |

| Education |

| Grade School (n=2, 0.5%) |

| High School (n=22, 5.1 %) |

| High School grad (n=97, 22.4%) |

| Trade or Technical School (n=24, 5.5%) |

| Some college (n=125, 29%) |

| Completed college (n=104, 24.1%) |

| Postgraduate (n=58, 13.4%) |

| Months since Dx (M=25.6, SD=7.9) |

|

Months since end of Tx (M=18.8, SD=8.6) |

| Surgery |

| Lumpectomy (n=246, 56.9%) |

| Mastectomy (n=128, 29.6%) |

| Bilateral mastectomy (n=58, 13.5%) |

| Chemotherapy |

| Yes (n=250, 57.9%) |

| No (n=182, 42.1%) |

| Radiation Therapy |

| Yes (n=304, 70.4%) |

| No (n=128, 26.9%) |

| Hormonal Therapy |

| Yes (n=288, 66.7%) |

| No (n=144, 33.3%) |

Copyright 2013, the Author

Older age has been cited as a barrier to retention (Fayter et al., 2007). However, in the RBCS study, older participants were more likely to be interested and be retained compared to younger participants. There are several potential explanations as to why older participants were retained compared with younger women. First, older participants were retired compared to younger counterparts who worked either full time or part time. Second, older participants had available time compared with younger women who worked and had families and children to attend to. And finally, older participants had more flexibility in scheduling their research meetings compared with younger women.

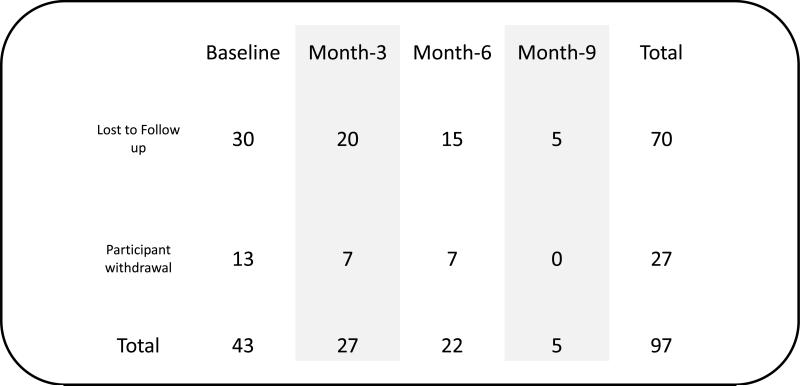

A total of 332 participants (77%) were retained in the study over the twelve month period. The largest number of participant attrition occurred between baseline data collection and Month-3. The lowest number of participant attrition occurred after Month-6. Once a participant passed the Month-3 time point, she was more likely to remain to the end of the study (see Figure 2). These finding suggest that the difference in retention underscored the importance of participant self-motivation, and the development of a trust relationship between the research nurse and participant over time.

Figure 2.

Attrition by Time Point (n=97). Reflects last data collection time point for participants lost to attrition (Copyright 2013, The Authors)

Successful Researcher Retention Factors

The run-in period between interest and enrollment allowed for withdrawal of consent prior to enrollment. There was a time lag of about 2-3 weeks (or longer if the participant requested) from the time the participant expressed initial interest to the time of enrollment. During this run-in period, participants had time to think over their informed consent and return their form. This time also was particularly useful for those participants who changed their mind about being able to fully engage in the study prior to enrollment or who had second thoughts prior to enrollment.

Success with retaining participants who were difficult to reach was achieved by numerous and persistent attempts to contact them over several weeks at different time intervals. In certain cases, participants who were retained despite being difficult to reach, had several family or health issues that arose precluding them from regular contact with the research nurse. The research nurse served as a strong support for the participant during the 12 months of study participation and worked hard to help the participant feel comfortable and at ease during times when study topics were either difficult or emotionally charged.

In the RBCS, financial incentives were distributed at the completion of study participation. Research participants were mailed a federal W-9 tax form and a self-addressed stamped envelope. Those participants who returned the W-9 were provided monetary incentive. The use of incremental rather than one time monetary incentives might be considered in future studies to enhance participant retention. A one-time monetary incentive distributed at the end of their participation may be a limitation.

Successful Participant Retention Factors

For those participants difficult to reach, email and a toll- free telephone number were critical in maintaining contact. Reminder telephone calls and/or emails were consistently offered, but were used infrequently by 1% of participants. Yet, the phone calls were very helpful for those participants who requested them as they missed fewer scheduled appointments, and were well prepared for the telephone interventions. When either telephone cards or “Go phones” were provided for those particularly difficult to reach participants, our experience showed that this retention strategy was not successful.

Given the duration of participation was over a 12 month time frame, there were unexpected and unfortunate life events that occurred in the participants’ lives. The research nurses sent a personal note on behalf of the RBCS team when participants experienced a tragic loss such as a death in the family, hospitalization, or a personal cancer recurrence. Personal notes helped to reinforce a mutually trusting, relationship bond between the research nurse and the participant. Developing a relationship of trust was crucial to the retention of many participants in the RBCS as participants were more likely to remain engaged in the study. The research nurses facilitated this relationship in several ways, but primarily used actively listening and having therapeutic communication during data collection, monthly calls, and telephone intervention.

Based on the trusting and caring relationship, participants often received assistance with their additional problems such as finding financial resources and appropriate tools to defer some of the financial burden associated with their cancer, emotional and psychological support, and information about how to access care for specific health problems or issues they were experiencing. The research nurses were the bridge between each participant and the research study as they emphasized the collaborative partnership between participants and researcher.

Our findings are consistent with a few reports in the literature with social support cited as an important element in participant retention. Social support was highly valued by the participants, and was provided during monthly telephone follow up and accessibility of the research staff through the toll-free number were already in place. Each research nurse was responsible for a caseload of participants to follow up with over the year, and develop a reciprocal relationship based on mutual respect and care. Participants indicated that they were more likely to complete the study if they felt their nurse genuinely cared about them, and had continuous open and therapeutic communication with them. Our findings further support Penckofer et al. (2011) whose data suggest that the relationship of patient to study personnel may be the most important factor in subject retention.

Motivations for retention in the RBCS ranged from personal expectation of improving one's health, gaining personal satisfaction to larger issues of furthering knowledge, benefiting people/patients in the future. This further supports findings from Penckofer and colleagues (2011) that altruism and self-motivation were the main reasons for participant retention.

Successful Contextual Retention Factors

The development of the Recruitment and Enrollment Tracking databases was essential to both timely recruitment and retention. The databases maximized the research nurses’ ability to track enrolled participants and identify early those who were at risk for attrition. The recruitment and the retention databases were developed by a database expert consultant who worked in conjunction with the research nurses in order to maximize user friendliness and usability. The development testing took nearly 100 working hours. Implementation and training of the research nurses took about 2 hours, as the databases were created to be intuitive and for ease of use by the nurses.

Discussion

The challenges faced over the course of this study provided useful information and insight as to how to maintain retention in future studies with rural women. Providing telephone-based interventions for rural women increased access to these services to this underserved population of breast cancer survivors. Those who were retained beyond Month-3 were most likely to remain in the study to completion. Those who were retained were also able to benefit from the development of a trusting relationship with their research nurse.

The use of a conceptual model of retention with the researcher, participant and contextual factors and three levels of primary, secondary and tertiary retention provided the guiding framework to examine the success, or lack thereof, of differential strategies. Similar to Robinson's findings, repeated and regular contact and minimizing participant burden were vital to retention. Moreover, the range of strategies (n=40) was large which also influenced retention of a hard to reach and underserved rural population. Further development and testing of conceptual models of retention of underserved populations is also recommended.

The electronic Recruitment and Enrollment tracking databases allowed for early identification of study drop out. While the development and testing of tracking databases took additional time, the authors believe this is time well spent in minimizing problems with participant tracking in the future, particularly among longitudinal research studies. The Recruitment and Enrollment tracking databases allowed the research nurses to note problems with participants at risk for drop out and allowed the research nurse to maintain steady contact with those difficult to reach.

Robinson et al. (2007) highly recommend the need for prospective evaluation of the effectiveness of differential retention strategies, specifically for those studies that are associated with higher costs in retaining participants. Further, Robinson et al. (2007) recommended that all study investigators should explicitly report retention strategies and retention rates to enhance our understanding of which strategies are most useful for underserved populations.

And finally, the development and maintenance of a trusting and supportive relationship between study participants and the research nurses were perhaps the single most vital aspect for successful retention of rural breast cancer survivors in the RBCS. Missed research appointments were viewed within the larger context of the individual participant's life. Family events, such as family emergencies and/or family celebrations, were woven into the fabric of flexibility, support, and trust between participant and research nurse.

Conclusion

Retention strategies for minorities or underserved populations should be tailored to include as many strategies as possible across the participant, researcher, and contextual strategies at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of retention. In addition, a research team approach using consistent measures over time can help to overcome some of these challenges to maintain and improve rural residents’ participation in cancer control research.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the breast cancer survivor participants and research team members: Silvia Gisiger-Camata, Madeline Harris, Ann Wooten, Andres Azuero, and Xiaogang Su.

Acknowledgment and Disclosure: The Florida cancer incidence data used in this report were collected by the Florida Cancer Data System under contract with the Department of Health (DOH). The views expressed herein are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the contractor or DOH.

Funding source: National Cancer Institute, RO1CA-120638-07

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

References

- Angell KL, Kreshka MA, McCoy R, Donnelly P, Turner-Cobb JM, Graddy K, Kraemer HC, Koopman C. Psychosocial intervention for rural women with breast cancer: The Sierra-Stanford Partnership. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18:499–507. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20316.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Computing RFFS. R Statistical Software v2.15.00 ed. 2008.

- Demark-Wahnfried W, Bowen DJ, Jabson JM, Paskett ED. Scientific bias arising from sampling, selective recruitment, and attrition: the case for improved reporting. Cancer, Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2011;20:415–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1169. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayter D, McDaid C, Eastwood A. A systematic review highlights threats to validity in studies of barriers to cancer trial participation. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2007;60:990–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.12.013. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman J, Blum TC. Assessing the non-random sampling effects of subject attrition in longitudinal research. Journal of Management. 1996;22:627–652. doi: 10.1177/014920639602200405. [Google Scholar]

- Janson SL, Alioto ME, Boushey HA, Asthma Clinical Trials Network Attrition and retention of ethnically diverse subjects in a multicenter randomized controlled research trial. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2001;22:236S–43S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(01)00171-4. doi: 10.1016/S0197-2456(01)00171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ka'Opua LS, Park SH, Ward ME, Braun KL. Testing the feasibility of a culturally tailored breast cancer screening intervention with Native Hawaiian women in rural churches. Health & Social Work. 2011;36:55–65. doi: 10.1093/hsw/36.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Theobald D, Wu J, Norton K, Morrison G, Carpenter J, Tu W. Effect of telecare management on pain and depression in patients with cancer: a randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304:163–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.944. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Authors. Under Review. Recruitment and enrollment to the Rural Breast Cancer Survivors Intervention randomized clinical trial.

- Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gotzche PC, Devereaux PJ, Elbourne D, Egger M, Altman DG, CONSORT CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. International Journal of Surgery. 2012;10:28–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2011.10.001. [Google Scholar]

- Penckofer S, Byrn M, Mumby P, Ferrans CE. Improving subject recruitment, retention, and participation in research through Peplau's theory of interpersonal relations. Nursing Science Quarterly. 2011;24:146–51. doi: 10.1177/0894318411399454. doi: 10.1177/0894318411399454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson KA, Dennison CR, Wayman DM, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Systematic review identifies number of strategies important for retaining study participants. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2007;60:757–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.11.023. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute SAS® 9.2 Software. 2008.

- Shumaker SA, Dugan E, Bowen DJ. Enhancing adherence in randomized controlled clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2000;21:226S–32S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00083-0. doi: 10.1016/S0197-2456(00)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmer M, Robinaugh D, Friedberg JP, Lipsitz SR, Natarajan S. Usefulness of a run-in period to reduce drop-outs in a randomized controlled trial of a behavioral intervention. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2008;29:705–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.04.005. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey AK, McCarthy WJ, Harrison GG, Wong WK, Siegel JM, Leslie J. Challenges in improving fitness: results of a community-based, randomized, controlled lifestyle change intervention. Journal of Women's Health (Larchmt) 2006a;15:412–29. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.412. doi:10.1089/jwh.2006.15.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annual Review of Public Health. 2006b;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]