Abstract

Purpose

Benzaldehyde dimethane sulfonate (DMS612, NSC281612, BEN) is an alkylator with activity against renal cell carcinoma, currently in phase I trials. In blood, BEN is rapidly metabolized into its highly reactive carboxylic acid (BA), presumably the predominant alkylating species. We hypothesized that BEN is metabolized to BA by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) and aimed to increase BEN exposure in blood and tissues by inhibiting ALDH with disulfiram thereby shifting BA production from blood to tissues.

Methods

Female CD2F1 mice were dosed with 20 mg/kg BEN iv alone or 24 h after 300 mg/kg disulfiram ip. BEN, BA and metabolites were quantitated in plasma and urine, and toxicities were assessed.

Results

BEN had a plasma t½ <5 min and produced at least 12 products. The metabolite half-lives were <136 min. Disulfiram increased BEN plasma exposure 368-fold, (AUC0-inf from 0.11 to 40.5 mg/L•min), while plasma levels of BA remained similar. Urinary BEN excretion increased (1.0% to 1.5% of dose) while BA excretion was unchanged.

Hematocrit, white blood cells counts and %lymphocytes decreased after BEN administration. Co-administration of disulfiram appeared to enhance these effects. Profound liver pathology was observed in mice treated with disulfiram and BEN.

Conclusions

BEN plasma concentrations increased after administration of disulfiram, suggesting that ALDH mediates the rapid metabolism of BEN in vivo, which may explain the increased toxicity seen with BEN after administration of disulfiram. Our results suggest that the co-administration of BEN with drugs that inhibit ALDH or to patients that are ALDH deficient may cause liver damage.

Keywords: Aldehyde dehydrogenase, disulfiram, alkylating agent, dimethane sulfonate, BEN

1. INTRODUCTION

Approximately 13,000 people die from metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) in the United States every year [1,2]. Only a small minority of patients achieve durable complete remission with high dose interleukin-2 cytokine therapy [3]. Recently developed agents targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor or the mTOR pathway have shown clinical activity [3–5]. However, responses to these novel agents are generally not durable [6], and there remains a need for new treatments of mRCC.

Benzaldehyde dimethane sulfonate (dimethane sulfonate, BEN, DMS612, NSC281612) has structural similarities to busulfan, melphalan and chlorambucil (Fig. S.1), and is presumed to be a bifunctional alkylating agent. COMPARE analysis suggested that the mechanism of action of BEN overlapped with that of chlorambucil [7]. However, unlike conventional bifunctional alkylating agents, BEN demonstrated specific activity against renal carcinoma cells in the NCI 60 cell line screen [7]. In vitro, BEN treatment resulted in S and G2/M cell cycle arrest [7]. BEN has demonstrated anti-tumor activity in mice with orthotopic renal cell carcinoma xenografts. Specifically, BEN showed significant activity against human 786-0 and ACHN renal cell tumors when administered to mice every four days for five cycles [8]. BEN treatment of mice bearing orthotopically implanted, human RXF-393 renal carcinoma cell xenografts resulted in >70% cure rate whereas busulfan showed no activity [8,9]. In addition, treatment with BEN slowed the growth of A498 human renal cell cancer xenografts [8]. It was hypothesized that BEN’s activity against renal carcinoma cells may be due in part to the hydrophobic moiety in the molecule which allows BEN to pass through the cell membrane or due to its sequence specificity for DNA alkylation [7]. The fact that BEN has displayed significant in vitro and in vivo activity against renal carcinoma cells and tumor xenografts has led to the evaluation of BEN in an ongoing NCI-sponsored phase I clinical trial (clinicaltrials.gov NCT00923520).

We have shown that in plasma, BEN is chemically converted into 6 different BEN analogs. Further, our previous studies suggest that BEN is rapidly metabolized into its benzoic acid analogue (BA) by red blood cells, presumably through aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity [10]. Preliminary studies in mice suggest that BEN is metabolized into at least 12 different BA products [10] (Fig. 1), and has a very short plasma half-life.

Fig. 1.

Proposed metabolic scheme for BEN in murine plasma. After iv injection to mice BEN is rapidly converted to BA. The sulfonate groups on BA are replaced with either chlorides or hydroxyl groups. Each analyte generated is also glucuronidated

ALDHs are NAD(P)+ dependent enzymes that metabolize both aromatic and aliphatic aldehydes into carboxylic acids [11]. Disulfiram (trade name Antabuse) is an inhibitor of ALDH and is prescribed to treat chronic alcoholism.

We showed that BA reacts faster with nucleophiles than BEN, and may therefore be an important effector of DNA alkylation [10]. The conversion of BEN to BA by RBCs is likely an activation step. However, the short half-life of BA may limit the ability of BA generated in RBCs to reach and alkylate tumor DNA. Therefore, a more prolonged and slower generation of BA from BEN, partly in tissues as opposed to primarily in RBCs, might increase the effects of BEN. The purpose of this study was to determine the pharmacokinetics and metabolism of BEN after iv administration in mice and to test our hypothesis that inhibition of ALDH with disulfiram increases the exposure to BEN and thereby increases its effects in mice.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Chemical and reagents

4-[bis[2-[(methylsulfonyl)-oxy]ethyl]amino]-2-methyl-benzaldehyde (NSC 281612, BEN), 4-[bis[2-[(methylsulfonyl)-oxy]ethyl]amino]-2-methyl-benzoic acid (BA), 4-[bis[2-chloro-ethyl]amino]-2-methyl-benzaldehyde (BEN-Cl2), 4-[bis[2-chloro-ethyl]amino]-2-methyl-benzoic acid (BA-Cl2), 4-[bis[2-[(methylsulfonyl)-oxy]ethyl]amino]-benzaldehyde (demethyl-BEN), and 4-[bis[2-chloro-ethyl]amino]-benzaldehyde (demethyl-BEN-Cl2) were obtained from the Developmental Therapeutics Program, National Cancer Institute (NCI, Bethesda, MD). 4-[bis[2-hydroxy-ethyl]amino]-2-methyl-benzaldehyde (BEN-(OH)2) and 4-[bis[2-hydroxy-ethyl]amino]-2-methyl-benzoic acid (BA-(OH)2) were generated as previously described [10].

Tetraethylthiuram disulfide (disulfiram) and gum arabic were acquired from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). PBS and saline were purchased from Fisher Scientific Co. (Fair Lawn, NJ). Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextran was obtained from The National Cancer Institute (NCI) Chemotherapeutics Repository (Bethesda, MD). All solvents used for LC-MS/MS were high purity Burdick & Jackson and purchased from Fisher Scientific Co. Formic acid was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. Nitrogen gas for the mass spectrometer was purified with a Parker Balston Nitrogen Generator (Haverhill, MA), and nitrogen gas for sample evaporation was purchased from Valley National Gases, Inc. (Pittsburgh, PA).

2.2. Animals

Specific-pathogen-free, adult CD2F1 female mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratory (Wilmington, MA). Mice were allowed to acclimate to the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute Animal Facility for ≥1 week before being used for study. Mice were maintained in micro-isolator cages in a separate room and handled in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 1996) and on a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh. Ventilation and airflow were set to 12 changes per h. Room temperatures were regulated at 22±1 °C, and the rooms were kept on automatic 12-h light/dark cycles. Mice received Prolab ISOPRO RMH 3000 Irradiated Lab Diet (PMI Nutrition International, St. Louis, MO) and water ad libitum, except on the evening before dosing, when all food was removed. Mice were 6–8 weeks old and weighed approximately 20 g at the time of dosing. Sentinel animals were maintained in the room housing study mice and assayed at 3-month intervals for specific murine pathogens by mouse antibody profile testing (Charles River, Boston, MA). Sentinel animals remained free of specific pathogens, indicating that the study mice were pathogen free.

2.3. Pharmacokinetic Study design

Mice were dosed iv with 20 mg/kg BEN alone or 24 h after ip administration of 300 mg/kg disulfiram, as described before [12]. BEN was formulated in a 20% solution of hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextran (HPβCD) in water and disulfiram was formulated as a suspension in 5% (w/v) gum arabic in PBS at a concentration of 30 mg/mL.

After administration of BEN, mice (three per time point) were euthanized with CO2 at multiple time points between 5 and 1440 min. Control animals received vehicle alone (0.01 mL/g fasted body weight) and were euthanized at 5 and 1440 min after dosing. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture in heparinized syringes and centrifuged for 4 min at 12,000×g at 4 °C to obtain plasma. A 200 μL aliquot of the resulting plasma was pipetted into a microcentrifuge tube containing 10 μL of 2 M H2SO4 and briefly vortexed to ensure stabilization of the analytes of interest. Plasma samples were stored at −70 °C until analysis.

2.4. Urinary excretion

Mice scheduled for euthanasia at 24 h after dosing were kept in metabolic cages. Urine was collected into tubes containing 2 M H2SO4 estimated to yield 5% acid by volume. At the end of the collection period, cages were washed with 15 mL of sterile water, and 2 M H2SO4 was added to all tubes in a ratio of 5 parts acid to 95 parts urine. Quantitation of analytes in urine and cage wash was accomplished by diluting an aliquot of each sample (between 10 and 100-fold) with control plasma followed by quantitation relative to a plasma standard curve.

2.5. Bioanalysis

BEN, BEN-Cl2, BA, BA-Cl2, BEN-(OH)2 and BA-(OH)2 were quantitated by LC-MS/MS as previously described [10]. For intermediate metabolites (BEN-OH, BEN-Cl, BEN-Cl-OH, BA-OH, BA-Cl, and BA-Cl-OH), and glucuronide conjugates, for which there were no reference standards available, the resulting analyte peak area was divided by the internal standard and the resulting ratio was converted to BEN equivalents by back-calculation using the BEN response equation. This assay, developed in human plasma, was modified for mouse plasma. Control murine plasma (Lampire, Pipersville, PA) resulted in linear, accurate, and precise calibration curves for all analytes. However, when control Lampire plasma was used to quantitate quality control samples prepared in control study mouse plasma, the accuracy was inadequate. Further inspection of the data showed that this was due to a plasma source specific internal standard response, and that the assay displayed adequate performance when peak areas were not corrected by internal standard responses, suggesting a difference in matrix effect between commercially available control Lampire plasma and plasma obtained from our study mice. Consequently, all unknown plasma samples were assayed relative to a calibration curve prepared in control plasma obtained from untreated study mice to assure generation of accurate data. Sample dilution to within the linear range was also performed with control plasma from study mice.

2.6. Pharmacokinetic analysis

The maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and the time to reach Cmax (Tmax) were determined by visual inspection of the plasma concentration versus time data. Other pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated non-compartmentally using PK Solutions 2.0 (Summit Research Services, Montrose, CO http://www.summitPK.com). The area under the plasma concentration versus time curve (AUC) of all analytes was calculated with the linear trapezoidal rule. Renal clearance was calculated by dividing the absolute amount of analyte excreted in urine by the plasma AUC0–t of the respective analyte.

2.7. Data analysis

Statistical analysis of AUC0–t values consisted of the BEN alone to BEN with disulfiram pretreatment AUC ratio with the associated standard error (SE). After log-transformation, these ratios were subjected to a two-sided Students t-test, under the null hypothesis of log (AUC-ratio)=0. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant, as described previously [13]. This approach is similar to that described by Bailer et al.[14]. However, instead of using a z-test, we applied a more conservative t-test with 2 degrees of freedom (N=3 samples per time point).

2.8. Pathology Study

Mice, treated with a single dose of disulfiram alone at 300 mg/kg ip in gum Arabic (N=1), BEN alone at either 20 mg/kg (the maximum tolerated dose, N=1) or 15 mg/kg iv (N=1), or mice treated with 300 mg/kg ip disulfiram 24 h prior to BEN at 20 and 15 mg/kg iv (N=2 each) or the combination of vehicles (20% HPβCD or PBS (0.01 ml/g body weight), N=1), and untreated controls (N=3), were followed for 30 days. Mice were euthanized with CO2 and bled by cardiac puncture one month after treatment. Complete gross necropsies were performed, livers were removed, weighed, and a portion of the medial lobe of each liver was placed in 10% phosphate buffered formalin, fixed, paraffin embedded, cut into 5 μm sections, processed and stained with hemotoxylin and eosin.

2.9. Blood Counts

Mice were treated as described in section 2.8. Blood was collected once daily by orbital sinus bleed or by tail vein bleed from the vehicle (N=1), BEN 15 mg/kg (N=1), BEN 20 mg/kg (N=1), BEN 15 mg/kg + disulfiram (N=2), and BEN 20 mg/kg + disulfiram (N=2) treated mice for at least 14 days using a potassium EDTA coated microhematocrit tube and run on an Scil Vet abc Veterinary Hematology Analyzer (Scil Animal Care Company, Gurnee, IL, 60031) to count platelets, white blood cells and lymphocytes. Hematocrit as percentage was determined with a micro hematocrit centrifuge by measuring the packed red cell height, dividing by the total height, and multiplying by 100.

3. RESULTS

This study was conducted to determine if BEN is metabolized to BA by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) and if BEN exposure could be increased by inhibiting ALDH with disulfiram in blood and tissues thereby shifting BA production from blood to tissues.

In order to measure the analytes generated when BEN is administered to mice we developed an LC-MS/MS assay. The assay for BEN and BA and analytes with known standards had a lower limit of detection of 1 ng/ml for all analytes and was accurate and precise from 10 to 1,000 ng/mL (Table S. 1) and the correlation coefficient (R2) was > 0.97 for all analytes.

There were 12 different metabolites detected in both the mice to which BEN had been administered alone and those to which BEN had been administered after disulfiram pretreatment. The plasma concentration versus time profiles are shown in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, and Fig. S. 2. Pharmacokinetic parameters associated with these profiles are displayed in Table 1 and Table S. 2.

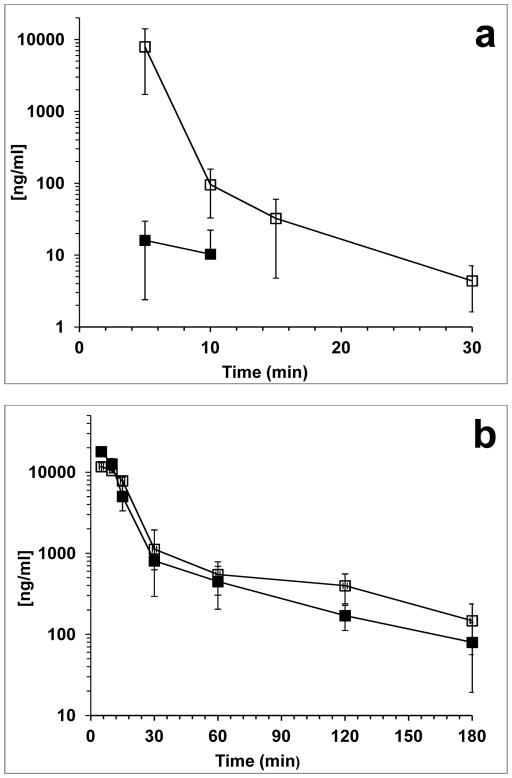

Fig. 2.

Concentration vs. time profile of BEN and quantitatable metabolites in mouse plasma. (a) BEN, (b) BA, (c) BA-Cl2, and (d) BA-OH2. (■) represents BEN administered alone and (□) represents BEN administered after disulfiram. Each point is the mean (±SD) of three mice

Fig. 3.

BEN equivalents vs. time profile of BEN metabolites. (a) BA-Cl-OH, (b) BA-Cl, and (c) BA-OH. (■) represents BEN administered alone and (□) represents BEN administered after disulfiram. Each point is the mean (±SD) of three mice

Table 1.

Non-compartmental plasma pharmacokinetic parameters of BEN and metabolites generated from the mouse PK experiments

| Parameter\Analyte | BEN | BA | BA-(OH)2 | BA-Cl2 | BA-Cla (BEN Eq) | BA-OHa (BEN Eq) | BA-Cl-OHa (BEN Eq) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 16 | 17967 | 327 | 48 | 440 | 847 | 185 |

| Cmax (ng/mL)b | 197 | 11700 | 473 | 46 | 387 | 851 | 229 |

|

| |||||||

| Tmax (min) | 5 | 5 | 10 | 30 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Tmax (min)b | 5 | 5 | 10 | 30 | 10 | 5 | 5 |

|

| |||||||

| Half-life (min) | 1.5 | 55 | 29 | 136 | 69 | 19 | 63 |

| Half-life (min)b | 5.2 | 42 | 34 | ND | 350 | 11 | 219 |

|

| |||||||

| AUC0-t(mg/L•min) | 0.11* | 254 | 9.66t | 4.41 | 17.8 | 15.8 | 9.21 |

| AUC0-t(mg/L•min)b | 40.5* | 267 | 15.3t | 4.86 | 18.1 | 18.3 | 11.3 |

|

| |||||||

| AUC0-inf(mg/L•min) | 0.11 | 261 | 10.6 | 7.01 | 19.6 | 17.7 | 10.3 |

| AUC0-inf(mg/L•min)b | 40.5 | 275 | 17.1 | 8.93 | 29.8 | 21.1 | 15.2 |

|

| |||||||

| Vd/F (L/kg) | ND | 6 | 83 | 562 | 102 | 33 | 176 |

| Vd/F (L/kg)b | 120 | 4 | 60 | 1272 | 241 | 17 | 320 |

|

| |||||||

| Cl/F (mL/min/kg) | ND | 0.08 | 1.90 | 2.90 | 1.02 | 1.17 | 1.90 |

| Cl/F (mL/min/kg)b | 0.18 | 0.07 | 1.20 | ND | 0.45 | 1.07 | 1.01 |

|

| |||||||

| % dose in urine (0–24 hr) | 1 | 5.8 | 1.36 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.55 | 0.15 |

| % dose in urine (0–24 hr)b | 1.5 | 5.95 | 3.30 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.54 | 0.43 |

| Clr mL/min | ND | 0.22 | 1.25 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.32 | 0.17 |

| Clr mL/minb | 0.40 | 0.22 | 1.92 | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.30 |

Analytes were detected and calculated as BEN equivalent concentrations.

Experiment in which disulfiram was administered to the mice before BEN

In order to calculate statistical significance AUC0-t values were compared at the same end time point in each study. The values followed by * were found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05).

ND: not determined, the parameter could not be defined

After iv administration of BEN to mice, BEN was rapidly metabolized resulting in a Cmax of 16 ng/mL at 5 minutes (Fig. 2a) (Table 1). While BEN became undetectable at 15 minutes after administration, BA was rapidly generated, had a plasma exposure 2300-fold greater than that of BEN, and an apparent half-life of 55 min (Fig. 2b) (Table 1). In addition to BEN and BA, 11 other metabolites including 6 glucuronides of BA, where detected. The half-lives of the metabolites ranged from 19 min (BA-OH) to 136 min (BA-Cl2) (Fig. 3) (Table 1). All of the analytes detected in plasma were also detected in the urine of the mice collected between 0–6 and 6–24 h after dosing with BEN (Table 1 and Table S. 2).

Treatment of mice with disulfiram 24 h prior to BEN dosing increased exposure to BEN 368-fold. Interestingly, BA exposure was similar in both studies. The half-lives of the metabolites ranged from 28 min (BA-OH-Gluc) to 350 min (BA-Cl) (Fig. 3 and Fig. S. 2) (Table 1 and Table S. 2). Although the exposure of all of the analytes appeared to increase after pretreatment with disulfiram only BEN, BA-(OH)2 and BA-(OH)2-Gluc were found to be statistically different when comparing the AUC0-t between BEN administered alone and BEN administered after disulfiram (Table 1 and Table S. 2). All of the analytes detected in plasma were also detected in the urine.

The untreated mice and vehicle treated mice did not lose body weight. The mice treated with disulfiram, BEN or the combination, lost approximately 12% body weight by day 4 and regained body weight by day 12.

The hematocrits, white blood cells and percent lymphocytes decreased following treatment in mice receiving BEN alone and disulfiram before BEN (Table 2). The hematocrits reached the lowest level at day either day 4 or 6 when dosed with 20 mg/kg BEN or day 6 or 8 when dosed with 15 mg/kg BEN. The white blood cell count was the lowest on day 4 after dosing except for 1 mouse in which the low point was not seen until day eight. The percent lymphocyte was lowest on either day 6 or day 8 after dosing. All values returned to normal by day 14 after dosing. Pretreatment with disulfiram before BEN appeared to deepen the percentage lymphocytes nadir compared to treatment with BEN alone.

Table 2.

Hematocrit (%), WBC and %Lymphocytes in mice treated with vehicle, BEN alone or disulfiram plus BEN. Each row represents the results of one mouse

| Treatment | Hematocrit (%) | WBC (x103 cells/μL) | %Lymphocyte | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day-1 | Day 0 | Day-1 | Nadir (day) | Day-1 | Nadir (day) | Day-1 | Nadir (day) |

| Vehicle | Vehicle | 47.8 | 51.3 (6) | 10.7 | 6.7 (4) | 75.8 | 60.4 (1) |

| Vehicle | BEN 20 mg/kg | 45.5 | 36.5 (4) | 9.6 | 3.1 (4) | 71.6 | 41.9 (8) |

| Disulfiram | BEN 20 mg/kg | 50.0 | 39.5(4) | 4.5 | 1.4 (4) | 83.0 | 28.5 (8) |

| Disulfiram | BEN 20 mg/kg | 43.8 | 37.0 (6) | 6.4 | 0.4 (4) | 72.6 | 35.5 (6) |

| Vehicle | BEN 15 mg/kg | 48.0 | 39.5 (6) | 5.9 | 2.7 (4) | 81.4 | 48.1 (8) |

| Disulfiram | BEN 15 mg/kg | 45.0 | 41.5 (6) | 5.1 | 3.7 (8) | 79.0 | 33.9 (6) |

| Disulfiram | BEN 15 mg/kg | 53.0 | 40.0 (8) | 5.8 | 3.1 (4) | 75.2 | 29.5 (6) |

When mice were euthanized one month after single dose treatment with either disulfiram or BEN alone, mild hepatic lesions were present in the mice. These lesions included mild focal thickening of the connective tissue capsule and mild fibrosis within few of the portal areas. Hepatic pathology of mice treated with the disulfiram and BEN combination (both at 15 and 20 mg/kg BEN) were profound and included a regional loss of overall hepatic vascular architecture with prominent swelling and clearing of hepatocyte cytoplasm, likely associated with areas of regenerative hyperplasia (Fig. 4). The capsule was diffusely thickened by increased connective tissue, and scattered lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates were observed. Multiple chronic adhesions existed between the thickened hepatic capsule and the omentum. Portal areas were severely expanded by increased fibrous connective tissue, hyperplastic bile ducts, and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates. Mild to moderate fibrosis also existed in centrilobular areas. Early bridging fibrosis spanned between portal areas and from portal to centrilobular areas (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

H&E stained liver sections from control, disulfiram-treated, BEN-treated (20 mg/kg), and disulfiram + BEN-treated (20 mg/kg) mice. Only mild hepatic lesions are present in mice treated with either disulfiram or BEN alone including slight thickening of the capsule (asterix) and a mild increase in portal fibrous connective tissue (arrowhead). Severe lesions in animals treated with a disulfiram + BEN combination include swelling and clearing of hepatocytes with a loss of overall hepatic vascular architecture, extensive capsular thickening (c), and severe portal fibrosis with bile duct hyperplasia (arrow). The “10x” and “20x” refer to the microscope objective magnifications that were used in each image. Each 10x and 20x objective digital image width = 1750 micrometers and 875 micrometers, respectively

4. Discussion

The present investigation was designed to characterize the pharmacokinetics and metabolism of BEN in mice, and to assess the effect of ALDH inhibition with disulfiram on BEN pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and pharmacodynamics in mice. Previous results suggested that BEN is metabolized in vivo and in vitro in blood into BA, presumably by the action of ALDH. We have demonstrated that BA reacts faster with nucleophiles than BEN, and may therefore be an important effector of DNA alkylation [10]. The conversion of BEN to BA by red blood cells (RBCs) is likely an activation step. However, the short in vitro half-life of BA (5 min), [10] may limit the ability of BA to reach and alkylate tumor DNA. Therefore, a more prolonged and slower generation of BA from BEN, partly in tissues as opposed to primarily in RBCs, might increase the effects of BEN administration. Disulfiram has been used previously in a mouse study for the purpose of inhibiting ALDH [12]. The authors of that study found that a single 300 mg/kg dose of disulfiram administered ip caused the greatest inhibition of both RBC and liver ALDH activity at 24 h post dose in which the reductions of ALDH activity in RBC and liver were 81% and 27% compared to controls. Thus, we used the same dose of disulfiram 24 h prior to the dosing of BEN to ensure the greatest inhibition of ALDH in study mice.

After iv BEN administration to mice, the exposure to BEN was low and there were at least 12 metabolites generated, including 6 BA glucuronides. In contrast, the exposure to BA was relatively high and the half-life of BA was 55 min. The plasma half-life of BA in mice was much longer than the in vitro half-life of BA, (5 min) [10]. The possibilities for the longer in vivo half-life of BA may be due to either BA being less reactive in vivo or more likely that there is continued production of BA from BEN in tissues which reappeares in plasma. Pretreatment with disulfiram increased BEN exposure 368-fold, suggesting that ALDH may be an enzyme responsible for metabolizing BEN into BA. Disulfiram is a non-specific inhibitor of multiple isoforms of ALDH and CYP P4502E1 [15–19]. However, while disulfiram did increase BEN exposure, BA was still the predominant species and its exposure was not decreased by disulfiram. This could be due to a number of factors. First, while disulfiram has been shown to be an effective inhibitor of ALDH in RBCs, disulfiram was less effective in inhibiting ALDH in the liver [12]. This difference in inhibition may be explained because RBCs are not able to synthesize de novo ALDH, while the liver may synthesize ALDH in the 24 h between the disulfiram administration and BEN administration. Further, there are at least 19 different known isoforms of ALDH [11]. It is possible that in tissues BEN is metabolized to BA, in part, by an isoform of ALDH that is not inhibited by disulfiram. For instance ALDH1B1 is insensitive to inhibition by disulfiram [20].

The 6 metabolites and their respective glucuronide conjugates that were observed after BEN administration were also observed when BEN was administered after disulfiram pretreatment. The plasma exposures of the glucuronides appeared to be higher after pretreatment with disulfiram, although the variability was too high to reach statistical significance (Table S. 2). This suggests that the inhibition of RBC ALDH increases BEN plasma exposure 368 fold driving greater BEN distribution into tissues where it is metabolized to BA. BA is then metabolized to downstream metabolites. In contrast, in the mice that were not pretreated with disulfiram, it is likely that the conversion of BEN to BA takes place in the RBCs to a greater extent. In this case, BA degrades to BA metabolites in the blood and these compounds are less likely to enter tissues.

Most of the observed metabolites are likely relevant to BEN efficacy and/or toxicity because they still possess alkylating side arms (Parise et al, 2012). Bifunctional alkylating agents have two side arms consisting of either a ethyl-methane sulfonate or ethyl-chloride that are active [21]. Monofunctional alkylators are much less potent than their bifunctional counterparts [22]. Of the non-glucuronide metabolites observed, BA-Cl2 is bifunctional, and three other metabolites are monofunctional.

In addition, we observed six BA glucuronide metabolites, two of the glucuronides are bifunctional and three are monofunctional. It is unclear which glucuronyltransferases are responsible for the conjugation of these BA analogues, and this could have an impact on BEN safety and efficacy. All of the metabolites that were detected in the plasma were also detected in the urine. The percentage of the dose of BEN excreted unchanged in the urine was 50% increased after disulfiram pretreatment. Biliary or urinary excretion could lead to high local concentrations of cytotoxics and result in toxicities. Known examples include ifosfamide and acrolein [23], and irinotecan and SN38(glucuronide) [24].

Toxicities associated with BEN treatment appear to be similar to those observed after treatment with other alkylating agents. After treatment with either busulfan or chlorambucil, bone marrow toxicity is observed and the nadir occurs sometime between day 4 and day 6 after a single treatment with these agents. The percentage decrease of all three measurements (hematocrit, WBC and %lymphocytes) was greater after pretreatment with disulfiram as compared to BEN alone. Again this could be due to the inhibition ALDH in blood by disulfiram allowing a greater concentration of BEN to reach the tissues, such as the bone marrow.

Although the pharmacokinetic study was conducted solely to determine the effect disulfiram has on the pharmacokinetic parameters of BEN, it was noted upon necropsy of the mice that the livers were abnormal. Further evaluation suggested that treating the mice with either disulfiram or BEN alone caused mild hepatic lesions, while mice that received the combination of disulfiram and BEN had severe and marked changes in the liver, as assessed 30 days after treatment. The cause of greater liver damage upon pretreatment with disulfiram may be due to the inhibition of blood ALDH, leading to an increase of BEN, and cellular metabolism of BEN to BA in the liver. This finding could have implications for the dosing of BEN in subjects: 1) on antabuse (disulfiram) therapy; 2) using other aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitors, such as metronidazole [25]; or 3) with aldehyde dehydrogenase deficiencies.

In conclusion, BEN is rapidly metabolized to BA partly by an ALDH. BA is then converted into at least 11 metabolites of which 6 are glucuronides, and most of which are expected to have alkylating activity. Inhibition of ALDH with a single ip dose of disulfiram before the administration of BEN slowed the metabolic degradation of BEN, however, BA was still the major plasma metabolite. The blood chemistry data and liver pathology suggests pretreatment with disulfiram and its inhibition of ALDH in RBCs may cause more BEN to enter tissues. More local metabolism of BEN to BA, a more reactive compound, leads to more tissue localized damage. This could be relevant to patients who are on antabuse therapy, have polymorphic ALDH1A1, or on a drug that inhibits ALDH as these conditions could result in severe liver damage and/or exacerbation of BEN toxicities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Information

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute [contract N01-CM-52202] and [grants U01-CA099168, P30-CA47904].

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute.

We thank Diane Mazzei and her colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh Animal Facility for their expert assistance, and the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute Hematology/Oncology Writing Group for constructive suggestions regarding the manuscript. Also, we like to thank Dr. Joseph M. Covey at the Toxicology and Pharmacology Branch, Developmental Therapeutics Program, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, for his intellectual input. We would like to thank Dr. Merrill Egorin for his help and guidance on conducting the experimentation that was required for this manuscript. He was a great mentor, colleague and friend, and he will not be forgotten.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer JClin. 2010;60 (5):277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen HT, McGovern FJ. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353 (23):2477–2490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Facchini G, Perri F, Caraglia M, Pisano C, Striano S, Marra L, Fiore F, Aprea P, Pignata S, Iaffaioli RV. New treatment approaches in renal cell carcinoma. Anticancer Drugs. 2009;20 (10):893–900. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32833123d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rini BI, Atkins MB. Resistance to targeted therapy in renal-cell carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10 (10):992–1000. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rini BI. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma: many treatment options, one patient. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27 (19):3225–3234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reeves DJ, Liu CY. Treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;64 (1):11–25. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-0983-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mertins SD, Myers TG, Holbeck SL, Medina-Perez W, Wang E, Kohlhagen G, Pommier Y, Bates SE. In vitro evaluation of dimethane sulfonate analogues with potential alkylating activity and selective renal cell carcinoma cytotoxicity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3 (7):849–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mertins S. Treating Renal Cancer Using a 4-[Bis[2-[(methylsulfonyl)oxy]ethyl]amino]-2-methyl-benzaldehyde. Patent Application Publication; United States: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter J. In vivo efficacy of an aldehyde degradation product of dimethane sulfonate (NSC 281612) in an orthotopic RXF-393 human renal tumor model. Proceedings of the American Association of Cancer Research; 2005. pp. 322–323. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parise RA, Anyang BN, Eiseman JL, Egorin MJ, Covey JM, Beumer JH. Formation of active products of benzaldehyde dimethane sulfonate (NSC 281612, DMS612) in human blood and plasma and their activity against renal cell carcinoma lines. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1980-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchitti SA, Brocker C, Stagos D, Vasiliou V. Non-P450 aldehyde oxidizing enzymes: the aldehyde dehydrogenase superfamily. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008;4 (6):697–720. doi: 10.1517/17425250802102627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tottmar O, Hellstrom E. Aldehyde dehydrogenase in blood: a sensitive assay and inhibition by disulfiram. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1983;18(Suppl 1):103–107. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(83)90154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beumer JH, Franke NE, Tolboom R, Buckle T, Rosing H, Lopez-Lazaro L, Schellens JH, Beijnen JH, van Tellingen O. Disposition and toxicity of trabectedin (ET-743) in wild-type and mdr1 gene (P-gp) knock-out mice. Investigational new drugs. 2010;28 (2):145–155. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailer AJ. Testing for the equality of area under the curves when using destructive measurement techniques. Journal of pharmacokinetics and biopharmaceutics. 1988;16 (3):303–309. doi: 10.1007/BF01062139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pratt-Hyatt M, Lin HL, Hollenberg PF. Mechanism-based inactivation of human CYP2E1 by diethyldithocarbamate. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2010;38 (12):2286–2292. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.034710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreb JS, Ucar D, Han S, Amory JK, Goldstein AS, Ostmark B, Chang LJ. The enzymatic activity of human aldehyde dehydrogenases 1A2 and 2 (ALDH1A2 and ALDH2) is detected by Aldefluor, inhibited by diethylaminobenzaldehyde and has significant effects on cell proliferation and drug resistance. Chem Biol Interact. 2012;195 (1):52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chippendale TW, Hu B, El Haj AJ, Smith D. A study of enzymatic activity in cell cultures via the analysis of volatile biomarkers. Analyst. 2012 doi: 10.1039/c2an35815h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong D, Kotraiah V. Modulation of aldehyde dehydrogenase activity affects (+/−)-4-hydroxy-2E-nonenal (HNE) toxicity and HNE-protein adduct levels in PC12 cells. J Mol Neurosci. 2012;47 (3):595–603. doi: 10.1007/s12031-011-9688-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotraiah V, Pallares D, Toema D, Kong D, Beausoleil E. Identification of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 modulators using virtual screening. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2012 doi: 10.3109/14756366.2011.653353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stagos D, Chen Y, Brocker C, Donald E, Jackson BC, Orlicky DJ, Thompson DC, Vasiliou V. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1B1: molecular cloning and characterization of a novel mitochondrial acetaldehyde-metabolizing enzyme. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2010;38 (10):1679–1687. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.034678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Povirk LF, Shuker DE. DNA damage and mutagenesis induced by nitrogen mustards. Mutat Res. 1994;318 (3):205–226. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(94)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall AG, Tilby MJ. Mechanisms of action of, and modes of resistance to, alkylating agents used in the treatment of haematological malignancies. Blood Rev. 1992;6 (3):163–173. doi: 10.1016/0268-960x(92)90028-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ciarimboli G, Holle SK, Vollenbrocker B, Hagos Y, Reuter S, Burckhardt G, Bierer S, Herrmann E, Pavenstadt H, Rossi R, Kleta R, Schlatter E. New Clues for Nephrotoxicity Induced by Ifosfamide: Preferential Renal Uptake via the Human Organic Cation Transporter 2. Mol Pharm. 2010 doi: 10.1021/mp100329u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulz C, Boeck S, Heinemann V, Stemmler HJ. UGT1A1 genotyping: a predictor of irinotecan-associated side effects and drug efficacy? Anticancer Drugs. 2009;20 (10):867–879. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328330c7d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karamanakos PN, Pappas P, Boumba VA, Thomas C, Malamas M, Vougiouklakis T, Marselos M. Pharmaceutical agents known to produce disulfiram-like reaction: effects on hepatic ethanol metabolism and brain monoamines. Int J Toxicol. 2007;26 (5):423–432. doi: 10.1080/10915810701583010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.