Abstract

The MSX2 homeoprotein is implicated in all aspects of craniofacial skeletal development. During postnatal growth, MSX2 is expressed in all cells involved in mineralized tissue formation and plays a role in their differentiation and function. Msx2 null (Msx2 −/−) mice display complex craniofacial skeleton abnormalities with bone and tooth defects. A moderate form osteopetrotic phenotype is observed, along with decreased expression of RANKL (TNFSF11), the main osteoclast-differentiating factor. In order to elucidate the role of such an osteopetrosis in the Msx2 −/− mouse dental phenotype, a bone resorption rescue was performed by mating Msx2 −/− mice with a transgenic mouse line overexpressing Rank (Tnfrsf11a). Msx2 −/− RankTg mice had significant improvement in the molar phenotype, while incisor epithelium defects were exacerbated in the enamel area, with formation of massive osteolytic tumors. Although compensation for RANKL loss of function could have potential as a therapy for osteopetrosis, but in Msx2 −/− mice, this approach via RANK overexpression in monocyte-derived lineages, amplified latent epithelial tumor development in the peculiar continuously growing incisor.

Introduction

Mutations in muscle segment homeobox (MSX) transcription factors cause craniofacial malformations such as cleft palate for MSX1 and craniosynostosis (Boston type) for MSX2 [1]. An MSX2 mutation is associated with amelogenesis imperfecta [2], highlighting the importance of this protein in dental epithelial cell differentiation and function. The fact that MSX2 is required for normal dental epithelial cell fates is supported by the Msx2 −/− mouse dental phenotype. These mutant mice present amelogenesis imperfecta and root dysmorphia associated with differentiation defects in epithelial cells (i.e., ameloblastic tumors and defects in Hertwig epithelial root sheaths [HERS] and epithelial cell rests of Malassez) [3]–[5]. In addition, Msx2 −/− mice display dentinogenesis imperfecta and regional and graded osteopetrosis from the first to the third molar, with inclusion of the mandibular third molar [3]. Molar inclusion can give rise to tooth ankylosis and odontogenic tumor formation [3]–[4], as described for other osteopetrosis mouse models (Src and ntl mutants) [6]–[7]. However, the role of osteopetrosis in the multifaceted dental phenotypes observed in Msx2 −/− mice is unclear. Previous studies have suggested that osteopetrosis in Msx2 −/− mutants could have two nonexclusive origins. First, because Msx2 is expressed during growth by a subpopulation of alveolar bone osteoclasts [3], this osteoclast subset may be missing in the null mutants. Second, gene expression of the key osteoclast differentiation factor RANKL is severely decreased in the dental epithelium and alveolar bone of Msx2 −/− mice [3]–[5]. Therefore, in order to investigate the importance of osteopetrosis in Msx2 −/− mouse dental defects, we developed a strategy to rescue bone resorption by overexpressing RANK in osteoclast precursors [8] of Msx2 −/− mice. The phenotypes of different teeth were then analyzed in these mice.

Materials and Methods

Animal generation and sampling

Ethics statement: the Consultative Bioethics Committee for Health and Life Science has specifically approved the present study (CEEA-2011-32). Staff trained to perform in vivo studies did all of the experiments.

Msx2 knockout (KO) mice were generated by replacing the entire coding sequence of Msx2 with the bacterial LacZ gene [3]. Rank transgenic mice were generated by heterologous recombination of a cassette containing 3.2 kb of the human myeloid related protein 8 (MRP8, also known as S100A8) gene promoter and the coding DNA sequence of the mouse Rank gene. Approximately 30 copies were inserted in tandem in the transgenic line [8].

Males that were heterozygous for the Msx2 gene mutation and overexpressed Rank were mated with females heterozygous for the Msx2 gene mutation in order to generate all possible Msx2 and Rank genotypes. The genetic background of all of the mice was CD1 Swiss. Mice were studied at 2, 3, 4, 8, 10, and 16 weeks, with at least three animals in each experimental group for a total of 147 animals.

Microradiographs, histological analyses, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity assays, and keratin 14 immunohistochemistry

After anesthesia of the mice, intracardiac perfusions were performed with a fixative solution containing 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, la Verpillière, France) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4. Complete fixation was ensured by immersion of the heads in fixative solution overnight at 4°C. After rinsing in PBS, the head halves (cut along the sagittal axis) were microradiographed on High Resolution Film SO-343 (Kodak Professional, Paris, France) with a microfocal X-ray generator (Tubix, Paris, France) at a focal distance of 56 cm for 20 min (power setting: 12 mA and 15 kV). The head halves were then processed for histology by decalcification at 4°C for up to 2 months (depending on the age of the samples) in a pH 7.4 PBS solution that contained 4% EDTA (Sigma) and 0.2% paraformaldehyde. After extensive washing in PBS, the samples were dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol and toluene and were finally embedded in paraffin (Paraplast plus, Sigma). Serial frontal sections of the head halves were sliced with a microtome (RM 2145; Leica, Rueil-Malmaison, France). The 7-µm-thick sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated before being either stained according to a modified van Gieson protocol [9], assayed for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity as previously described [9], or immunolabeled for cytokeratin-14. Briefly, after saturation for 1 h with 10% horse serum in 1×PBS, sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-keratin-14 rabbit primary antibody (PRB-155P; Covance, Paris, France). After washing in 1×PBS, an anti-rabbit biotinylated secondary antibody (BA-1100; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) was applied for 1 h. Sections were then washed, treated with streptavidin–alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Roche, Meylan, France), and stained with nitro-blue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolyphosphate (NBT/BCIP, Roche).

Micro-computed tomography scanner imaging

A micro-CT scanner (desktop Skyscan 1172; Skyscan, Aartselaar, Belgium) was used to provide three-dimensional images of mouse mandibles. This system is based on a cone-beam X-ray source. A spatial resolution that produced voxels that measure 6.7 µm per side was used. Acquisition parameters were 80 kV anode voltage and 100 mA for an exposition time of 4 s. A 0.25° rotation step was performed between two expositions. A total of five expositions were obtained for each angle, and means were calculated. For each mode, a 0.5-mm aluminum filter was installed in the beam path to block the softest X-rays and to increase the accuracy of the beam-hardening correction (BHC). Cross-sectional images were reconstructed with a classical Feldkamp cone-beam algorithm with NRecon (Skyscan). Three-dimensional reconstructions were achieved with the software package CTAn (Skyscan). A threshold between 40 and 140 was selected, because it provided the best image of the mandible and suppressed artifacts.

RT-PCR and TaqMan array RT-qPCR analyses

Dissections of 2-week-old mouse mandibles (five mice per group) were performed under a stereomicroscope in order to collect alveolar bones and incisor epithelia, as previously described [5]. Tissues were directly immersed in RNA extraction solution (Tri-Reagent; Euromedex, Souffelweyersheim, France), and the extraction was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. For classical RT-PCR, reverse transcription was performed on 1 µg of total RNA with Superscript II (Gibco, Cergy-Pontoise, France) and hexanucleotide random primers (Gibco), and PCRs were done with Eurobiotaq (Eurobio, Courtaboeuf, France), following the manufacturer's instructions. The following sets of primers chosen in different exons were used: RankTg-Fw ATG TCT CTT GTC AGC TGT CTT; RankTg-Rv GCT CAT AAT GCC TCT CCT G; Rank-Fw CTT GGA CAC CTG GAA TGA AGA AG; Rank-Rv AGG GCC TTG CCT GCA TC; Rankl-Fw CAG CAT CGC TCT GTT CCT GT; Rankl-Rv TCG TGC TCC CTC CTT TCA TC; Opg-Fw TGA TGA GTG TGT GTA TTG CAG C; Opg-Rv CCC AGG CAA ACT GTC CAC CAA; Runx2-Fw GGA CGA GGC AAG AGT TTC AC; Runx2-Rv TGC CTG CCT GGG ATC TGT AA; Ocn-Fw CTC ACT CTG CTG GCC CTG; Ocn-Rv CCG TAG ATG CGT TTG TAG GC; CD3e-Fw ACT GGA GCA AGA ATA GGA; CD3e-Rv AGG AGA GGA AAG GAA CTG; CD19-Fw CCA TCG AGA GGC ACG TGA A; CD19-Rv TCC ATC CAC CAG TTC TCA ACA G; F4/80-Fw AGA TGG GGG ATG ACC ACA CTT C; F4/80-Rv TGT TCA GGG CAA ACG TCT CG; Csf1r-Fw GAC TTC GCC CTC AGC TTG G; Csf1r-Rv TCC CCA GAC CCC TCA TGT T; CD11b-Fw TGG GCA GGT GGA GCC TTC CT; CD11b-Rv CAC TGC CAC CGT GCC CTC TG; CD11c-Fw CTG AGA GCC CAG ACG AAG ACA; CD11c-Rv TGA GCT GCC CAC GAT AAG AG; 18S-Fw AAA CGG CTA CCA CAT CCA AG; 18S-Rv CCT CCA ATG GAT CCT CGT TTA. PCR products were separated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and were photographed with a Bio-Rad Gel Doc XR camera (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France).

For TaqMan quantitative RT-PCR arrays, reverse transcription was performed on 1 µg of total RNA with the High Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and PCR was performed with a 7900HT Fast system real-time PCR apparatus using Taqman mouse immune arrays (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using a one-factor analysis of variance to assess the effects of genotype. As appropriate, post-hoc testing was performed using Fisher's Protected Least Significant Difference (PLSD). Differences were considered significant at p≤0.05. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M).

Results and Discussion

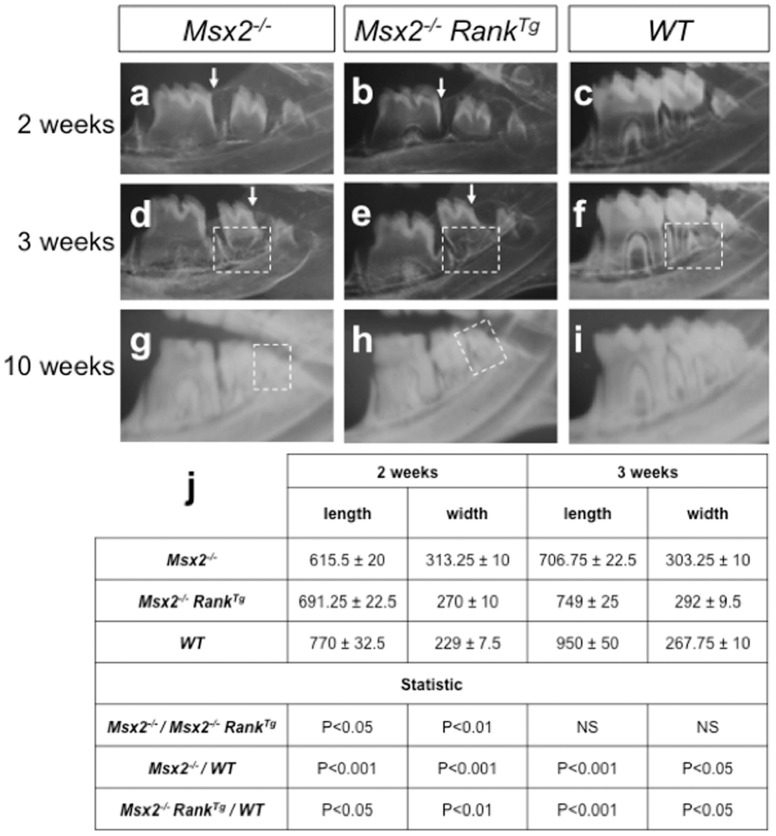

Analyses of Msx2 −/− mouse molars revealed delayed tooth eruption and shortened roots (Fig. 1a, d, g) [3], [9]. RANK overexpression on an Msx2 −/− background (Msx2 −/− RankTg) resulted in significant recovery of all molar eruption and root elongation processes, as revealed by the relative positions of the teeth and alveolar bone crests (arrows in Fig. 1a–e), full eruption of the third molar (square in Fig. 1g–h), and the greater length of the molar roots at day 14 comparatively to Msx2 −/− mouse molar (square in Fig. 1d–f; Fig. 2a, b; Fig. S4c). Measures of Msx2 −/−, Msx2 −/− RankTg and WT mouse mandible first molar mesial root length and width at 2 and 3 weeks, performed on histological sections (three animals by group) using Image-J software, confirmed that, at 2 weeks, roots are significantly longer (p<0.05) in Msx2 −/− RankTg molars comparatively to Msx2 −/− molars but remained shorter (p<0.05) than WT molars (Fig. 1J). Moreover, the root width was significantly reduced in Msx2 −/− RankTg molars comparatively to Msx2 −/− molars (p<0.01) as previously described [9] but was superior (p<0.01) to WT molars (Fig. 1J).

Figure 1. Effect of transgenic Rank on lower molar growth in Msx2 − /− mice.

Microradiographs were taken at 2 (a–c), 3 (d–f), and 10 (g–i) weeks for Msx2 −/− mice overexpressing (b, e, and h) or not expressing (a, d, and g) transgenic Rank, and for WT mice (c, f, and i). At 2 and 3 weeks, eruption of the first and second molars was more advanced in Msx2 −/− RankTg mice than in Msx2 −/− mice, as shown by their positions relative to the vestibular bone crest (arrows in a, b, d, and e). At 3 weeks, the most significant feature of the progression in second molar growth was the more advanced root elongation in Msx2 −/− RankTg mice compared to Msx2 −/− mice (squares in e versus d). However, the root lengths did not match those of WT mice (square in f). At 10 weeks, while the third molars of Msx2 −/− mice were completely surrounded by and indistinguishable from bone on the microradiograph (square in g), the third molars of Msx2 −/− RankTg mice were fully erupted and functional (square in h). Measures of the first molar mesial root length and width at the median position (in µm) were performed on histological sections and presented in a table form (j). A higher length and lower width were observed at 2 weeks for Msx2 −/− RankTg molar root comparatively to Msx2 −/− molar root. However, Msx2 −/− RankTg molar root length and width remained respectively lower and superior to those observed for WT molar root. At 3 weeks, no significant difference of length and width was observed between Msx2 −/− RankTg and Msx2 −/− molar roots.

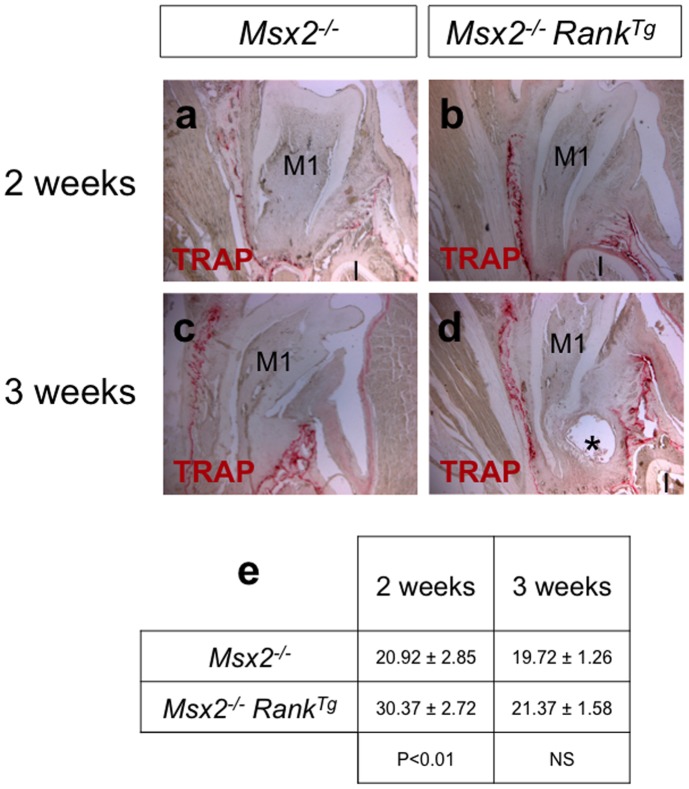

Figure 2. Rank overexpression stimulates alveolar bone osteoclastogenesis.

TRAP activity assays were performed on frontal sections of the mandibles of 2 (a, b) and 3 (c–f) week-old mice to determine the effect of Rank overexpression on osteoclast numbers. At 2 weeks, the number of TRAP-positive cells was significantly increased around the first molar root in Msx2 −/− RankTg mice (b, e). The root appeared longer but thinner in Msx2 −/− RankTg than in Msx2 −/− mice, and advanced eruption was also clearly visible. At 3 weeks, no significant difference in the number of TRAP-expressing cells was observed (c, d, e). While the length of the first molar roots of Msx2 −/− mutants expressing or not expressing Rank was similar, it remained thinner in Msx2 −/− RankTg mice (c, d). Asterisk in (d): Epithelial cyst on the lingual part of the root of a Msx2 −/− RankTg mouse. M1, first molar; I, incisor. (e) Numbering of the TRAP positive cells in the alveolar bone surface performed on 7 µm thick sections (n>8) and presented as a table with statistical analyses.

At 3 weeks, mandible first molar mesial root length and width were not significantly different (p>0.5) in Msx2 −/− RankTg and Msx2 −/− mice (Fig. 1j) but were respectively significantly lower (p<0.001) and higher (P<0.05) than WT mouse ones (Fig. 1j).

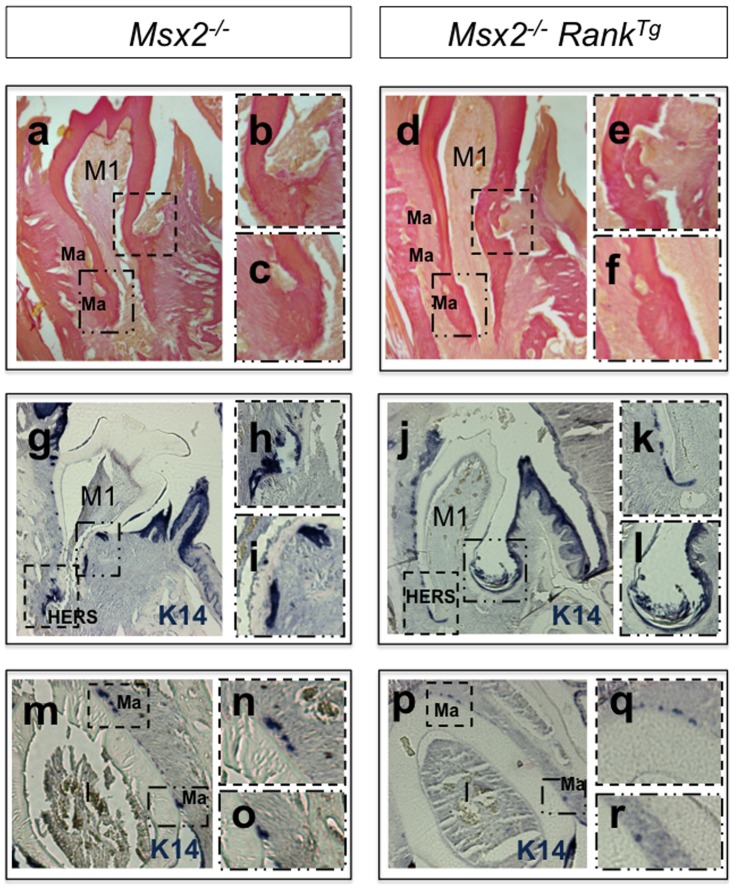

RANK overexpression resulted in a significant (p = 0,0014) increased osteoclast numbers at 2 weeks (Fig. 2), a better commitment of HERS cells in the labial area (Fig. 3g, h, j, k), and a normalization in the size (volume measured using Image-J software) of most of the epithelial cell rests of Malassez (Fig. 3a, c, d, f; Fig. S1). However, the root morphology of Msx2 −/− mice was not completely restored. The roots remained shorter than in wild-type (WT) mice (Fig. 1g–j) [9]. Moreover, epithelial cyst-like structures that were occasionally observed in the lingual area of the mandibular first molar mesial root in Msx2 −/− mice (Fig. S2a) were also present in the Msx2 −/− RankTg mutants (asterisk in Fig. 2d), at an approximately similar frequency, suggesting that the origin of these cyst-like structures was associated with MSX2 loss of function in epithelial cells. Keratin-14 immunostaining showed that these structures were associated with apparent continuity between dental and oral epithelia (Fig. 3j) and the formation of a periodontal pocket (square in Fig. 3j enlarged in 3l). Interestingly, cyst-like structures were only observed in the lingual part of the root. This asymmetrical localization may be associated with a labial-lingual gradient of transcription and growth factor expression during tooth morphogenesis and initial histogenesis [10]–[11]. Indeed, MSX2 loss may affect the expression or function of other factors; for example, DLX2 is known to be a key MSX2 partner [12].

Figure 3. Effect of transgenic Rank on lower first molar and incisor root formation in Msx2 − /− mice.

Van Gieson histology staining (a–f) and keratin immunohistochemistry (g–r) were respectively performed on mandibular frontal sections of 3- and 2-week-old Msx2 −/− mice either overexpressing or not expressing transgenic Rank. At 3 weeks, Rank overexpression had induced a normalization in the size of most epithelial cell rests of Malassez (Ma) (a and c versus d and f), and at 2 weeks it had induced a better commitment of Hertwig epithelial root sheath (HERS) cells, specifically in the labial area (j and k versus g and h). Occasionally and independently of Rank overexpression, epithelial cyst–like structures were observed in the lingual area of Msx2 −/− mandibular first molars (j, i). Cytokeratin-14 immunolabelling revealed that these cyst-like structures were associated with abnormal continuity between dental and oral epithelia (j) and the presence of a periodontal pocket (square in j enlarged in l). Another defect observed at 3 weeks in the lingual root of Msx2 −/− mice, also independent of Rank overexpression, was a lacuna-like structure in the dentine facing the site of transition between crown and root epithelia (squares in a and d enlarged in b and e, respectively). In the incisor root equivalent, normalization of the size of the epithelial cell rests of Malassez (Ma) was observed in Msx2 −/− RankTg mice (squares in m versus p enlarged in n and o and q and r, respectively).

Another defect observed in the lingual root of Msx2 −/− mice, independent of RANK overexpression, was the presence of a lacuna-like structure in the dentine at the crown-root transition site (squares in Fig. 3a, d enlarged in 3b, e, respectively). These structures were maintained in the adult (asterisks in Fig. S2b, c).

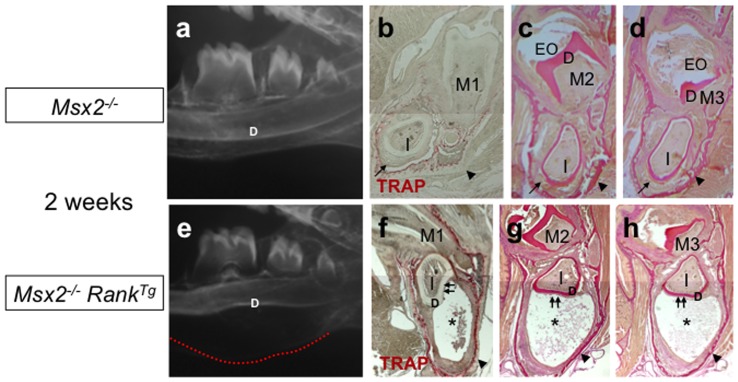

Similar to the molars, the defect in the root analog region of the incisors was improved by RANK overexpression, as reflected by a better commitment of HERS cells and the more typical size of the epithelial cell rests of Malassez (Fig. 3m–r). Strikingly, however, by 2 weeks, in the crown equivalent area of all incisors, the dental epithelium had converted into a massive osteolytic tumor (Fig. 4a–h). The tumor caused a deformation in the dentin (double arrows in Fig. 4f–h) and was associated with substantial resorption of the surrounding bone, as shown by the increased osteoclast numbers (Fig. 4b, f). The tumor caused total destruction of the mandible within 4 months (Fig. 5c). The increased osteoclasts around the incisor seemed to have a positive impact on tumor growth. This scenario is reminiscent of a previously described amplification loop between tumor cells and osteoclasts, which may occur in bone metastasis of several tumor types [13].

Figure 4. Effect of Rank overexpression on lower incisors of Msx2 − /− mice.

Mandibular microradiographs (a, e) and TRAP activity assays (b, f) or van Gieson histology staining (c, d, g, h) of mandibular frontal sections were performed to characterize the effect of Rank overexpression on the lower incisors of 2-week-old Msx2 −/− mice. Substantial enlargement of the area between the basal bone and the dentin was observed in Msx2 −/− RankTg mice (e) compared to Msx2 −/− mice not expressing RankTg (a). This enlarged area, which corresponds to the incisor epithelial compartment, was associated with abnormal curvature in both basal bone (red dotted line) and dentin (D). Mandibular frontal sections through the first (M1), second (M2), and third (M3) molar planes revealed that the enlargement corresponds to an epithelial hypertrophy with the presence of an internal necrosis-like area (asterisks in f–h). In Msx2 −/− incisors, no hypertrophy of the epithelium was visible, but this tissue was disorganized and lacked the ameloblastic palisade structure (arrows in b–d). There was also a substantial increase in the number of osteoclasts around the incisors of Msx2 −/− RankTg mice (f) compared to Msx2 −/− mice not expressing RankTg (b). Moreover, the thickness of the mandibular basal bone in the Msx2 −/− RankTg mutants appeared highly reduced compared to Msx2 −/− mice not expressing RankTg (arrowheads in f–h versus b–d).

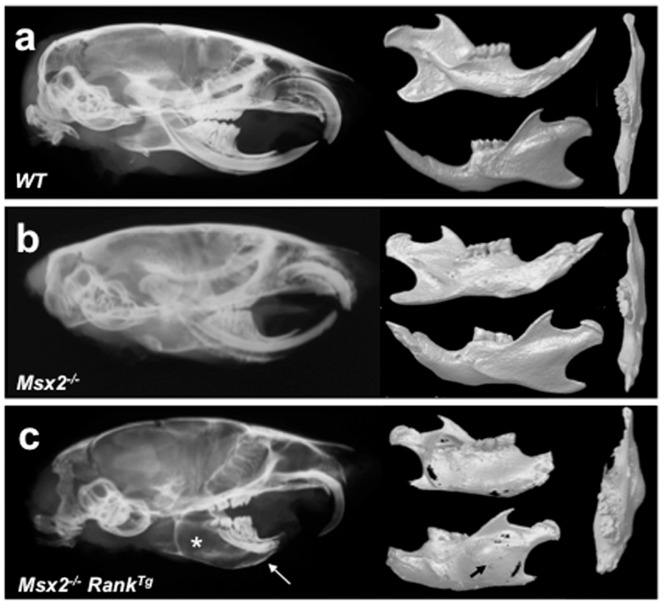

Figure 5. Combined effects of loss of Msx2 and Rank overexpression on mouse mandibular bone phenotype.

Microradiographs and scans of 16-week-old WT (a), Msx2 −/− (b), and Msx2 −/− RankTg (c) mouse skulls were performed to compare characteristics of the bone of the mandible. While the Msx2 −/− mouse mandibular features (b) presented no major alterations compared to WT animals (a), Msx2 −/− RankTg mice had marked disruptions in the architecture of the mandibular bone (c). These disruptions were either mono- or bilateral and were associated with conversion of the incisor epithelium toward massive osteolytic tumors (asterisks in c). Basal bone around these tumors was thinner (arrows in c), porous (arrow in c), and displaced, as seen in the upper view of the mandibular scan (c).

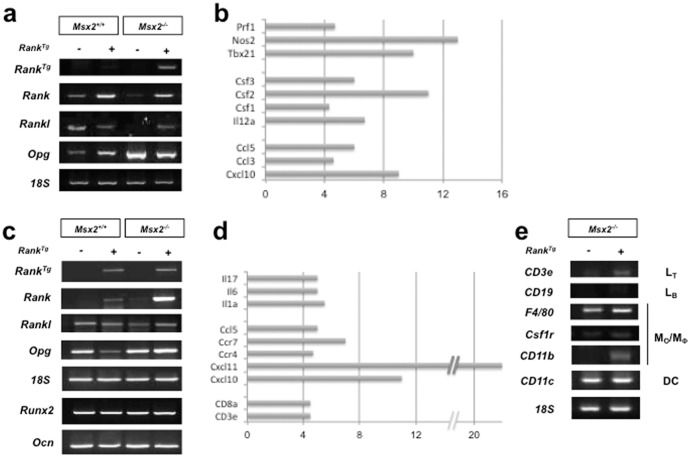

The MSX2 homeoprotein is a critical factor for epithelial cell commitment in various organs, including skin and skin appendages [3], [14]. MSX2 misexpression was reported in tumors of these epithelial tissues in the context of bone metastasis [15] and osteolysis [16]. During bone resorption, MSX2 may positively regulate RANKL expression, as suggested by a reduction in Rankl expression in the dental epithelium of Msx2 −/− mice (Fig. 6a) [3]–[5] and similar expression in odontogenic tumors [17]. This regulation is of particular importance, because increased RANKL expression in tumor cells is directly correlated with hyperactive bone resorption [18]. To further elucidate how RANK overexpression promotes the conversion of Msx2 −/− mouse incisor epithelium into massive tumors, expression levels of Rankl, Opg (Tnfrsf11b), Rank, and various inflammation markers were comparatively analyzed in the epithelium of 14-day-old WT and Msx2 −/− mice that lacked or expressed the Rank transgene (Fig. 6a, b). Rankl, Rank, and Opg expression were detected in WT mouse incisor epithelium. In contrast, in Msx2 −/− mouse incisor epithelium, Rankl and Rank expression decreased but Opg expression increased (Fig. 6a), in accordance with the previously described osteopetrotic phenotype [3]. In RankTg mouse incisor epithelium, Rank and Opg expression was increased and Rankl expression decreased compared to WT epithelium (Fig. 6a), as previously reported [9]. These variations are explained by the more advanced stage of tooth eruption [9]. In the Msx2 −/− RankTg mouse epithelium, Rankl and Rank expression was increased and Opg expression decreased compared to Msx2 −/− mouse epithelium (Fig. 6a). These variations are consistent with the observed augmentation in the surrounding alveolar bone resorption at 2 weeks (Fig. 2a, b). Interestingly, transgene expression was observed only in Msx2 −/− RankTg mouse epithelium (Fig. 6a), suggesting that cells within the tumor mass were expressing the transgene; these cells might correspond to monocyte-derived cells. To further characterize the immune cells infiltrating the epithelial tumor, TaqMan inflammation/cancer array analyses were performed. Elevated signals for Prf1, Nos2, and Tbx21 (Fig. 6b; Fig. S3) are indicative of intra-tumoral T helper type 1 cytotoxic cells, in addition to monocyte-derived cells that are likely recruited and maintained by CSF1 (Fig. 6b). Cytotoxic cells may also be natural killer (NK) cells, which would correspond with the observed unaltered CD8a expression levels (Fig. S3) and increased transcription of genes encoding factors such as IL12A and CXCL10 (Fig. 6b; Fig. S3), which are known to stimulate NK cell chemotaxis and differentiation [19]. In response, NK cells produce IFNG, TNF, CSF2, CCL3, and CCL5 [19], which are all up-regulated in Msx2 −/− RankTg mouse epithelium (Fig. 6b; Fig. S3). Further studies will be necessary to unravel the mechanistic relationship between inflammatory cell recruitment and epithelial tumor activation, and the relationship between tumor growth and RANKL expression. Keeping in mind that cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage were present in the epithelial tumor (Fig. 6a), the recent finding that monocytes control NK cell differentiation in the context of antitumor immunity [20] constitutes an interesting basis for future studies.

Figure 6. Gene signature induced by Rank overexpression in the dental epithelium and alveolar bone of Msx2 − /− mice.

RT-PCR of total RNA extracted from dental epithelium (a) and alveolar bone (c, e) revealed Rank expression in the epithelium and alveolar bone of Msx2 −/− RankTg mice. Increased Rankl expression was associated with Rank overexpression in Msx2 −/− mice (a, c). In Msx2 −/− mice, Rank overexpression induced a decrease in Opg transcriptional activity in the epithelium, while in alveolar bone, expression of Opg increased slightly (a, c). Expression levels of Runx2 and Ocn in alveolar bone were unaffected by Rank overexpression (c), but expression of the T lymphocyte marker Cd3e and the monocyte and macrophage markers Csf1r, F4/80 and Cd11b were increased (e). Also shown are 4-fold or higher increases in gene expression in Msx2 −/− RankTg mice compared to Msx2 −/− mice not expressing RankTg, as quantified by RT-qPCR TaqMan arrays in dental epithelium (b) and alveolar bone (d).

The epithelial tumor growth resulted in marked resorption of the surrounding alveolar bone, likely due to increased osteoclast numbers (Fig. 4f). Interestingly, Runx2 and osteocalcin transcripts remained stable, indicating unaltered bone apposition (Fig. 6c). The rise in osteoclast numbers is likely the result of the marked increase in Rankl expression (Fig. 6c). Analysis of different immune cell–lineage markers (Fig. 6e) suggested that cells of the myeloid linage were increased in Msx2 −/− RankTg mouse alveolar bone. There also appeared to be an increase in the cytotoxic T lymphocyte population, as suggested by increased CD3e and CD8a expression (Fig. 6d, e). These data and the high expression levels of Il1a, Il6, Il17 Ccl5, Ccr4, and Ccr7 (Fig. 6d) provide evidence for enhanced bone loss through inflammation, as described in other pathologies [21]. CXCL10 functions as a chemokine for monocytes and is implicated in osteoclastogenesis [22]–[25], with possible crosstalk with RANKL [24]. Thus, CXCL10 production may constitute a key element in the massive osteolytic epithelial tumor development observed in Msx2 −/− RankTg mice by fostering an amplification cycle between tumor growth and alveolar bone resorption. CXCL11 was shown to inhibit osteoclastogenesis by a mechanism independent of its CXCR3 receptor [26]. CXCL11 should therefore interfere with increased bone resorption and tumor growth. On the other hand, CXCL11 is also known to activate T lymphocytes [27], which could amplify inflammation of the bone environment and adjacent epithelia, where increased Cxcr3 transcriptional activity was observed (Fig. S3).

In addition to above described effects of RANK over-expression on Msx2 −/− dental phenotype, benefic effects of such over-expression have also been observed in other skeleton sites known to be affect in Msx2 −/− mouse (Fig. S4). For instance, the characteristic open foramen of Msx2 −/− mouse skull was partly closed in RANK over-expressing mutant (Fig. S4a). Similarly, the Msx2 −/− mouse tibia that presented features of soft osteopetrosis switched to rather osteopenic bone in RANK over-expressing mutant (Fig. S4b). Nevertheless, other skeleton defects associated to MSX2 lost were poorly improved by RANK over-expression as the tibia length that remained shorter than WT mouse one (Fig. S4b).

Conclusion

In conclusion, rescuing bone resorption in Msx2 −/− mice by overexpressing RANK in the osteoclastic lineage allowed for the correction of a substantial portion of the molar abnormalities, most likely by counteracting the decrease in RANKL expression, which is correlated with Msx2 −/− osteopetrosis. From a more general viewpoint, our results indicate that functional compensation may be a promising approach for the treatment of osteopetrosis. However, in this mouse model, in which Msx2 was not expressed and RANK was overexpressed, and which features continuously growing incisors, precocious formation of a massive and osteolytic odontogenic epithelial tumor was observed.

Supporting Information

Comparative analysis of epithelial rest of Malassez sizes in roots of wild type, Msx2−/− and Msx2−/− RankTg mice. Whatever the age considered, the RANK over-expression in the Msx2−/− mouse normalized the size of the rest of Malassez. Measures were realized as previously described [5] using Image-J software.

(TIF)

Van Gieson staining of Msx2−/− mouse mandible first molar frontal sections at 3, 4 and 16 weeks.The presence of a cyst-like structure at the root lingual surface was observed at 3 weeks (a). At 4 and 16 weeks lacunae in the dentin area facing the site of transition between crown and root epithelium was present (asterisk in b–c). D: dentine; PDL: periodontal ligament; P: pulp.

(TIF)

Table of the TaqMan immune arrays results. Numbers corresponded to the induction folds observed in the 14 day-old Msx2−/− RANKTg mouse tissues comparatively to Msx2−/− mouse tissues. Negative numbers corresponded to reduction folds and ND means that no expression difference has been detected. Inductions over 4 folds have been reported in Figure 6.

(DOCX)

Combined effects of loss of Msx2 and Rank overexpression on mouse skull, tibia and molar phenotypes. Upper and lateral scan-views of skulls of 14 day-old wild type, RANKTg, Msx2−/− and Msx2−/− RANKTg mice (a) enabled to see a significant reduction of the open foramen in the Msx2−/− RANKTg mouse comparatively to Msx2−/− mouse while sutures were normal in RANKTg mouse as in WT mouse. Scan-sections along tibias of 14 day-old WT, RANKTg, Msx2−/− and Msx2−/− RANKTg mice (b) evidenced that RANK over-expression moderately increased Msx2−/− mouse tibia length without reached the normal size seen in RANKTg and WT mice. BV/TV measures on sections realized at 50, 30 and 15% of tibias length evidenced that RANK over-expression is able to reverse the mild osteopetrosis phenotype seen in Msx2−/− mouse toward a rather osteopenic phenotype also visible in RANKTg mouse. Lateral scan-views of mandible first molars of 14 day-old wild type, RANKTg, Msx2−/− and Msx2−/− RANKTg mice (c) enabled to see a significant reduction of the mesial root length in Msx2−/− and Msx2−/− RANKTg mice comparatively to WT mouse with however a longer root in Msx2−/− RANKTg mouse comparatively to Msx2−/− mouse.

(TIF)

Funding Statement

B. Castaneda was a grantee of the Institute Français de la Recherche Odontologique. This work was supported by funding from INSERM UMR872 team5, French Hospital Research Program (PHRC funding Teios) and French National Cancer Institute (Funding INCA-6001). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Cohen MM Jr (2006) The new bone biology, molecular, and clinical correlates. Am J Med Genet A 140 (23) 2646–2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Suda N, Kitahara Y, Ohyama K (2006) A case of amelogenesis imperfecta, cleft lip and palate and polycystic kidney disease. Orthod Craniofac Res 9 (1) 52–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aïoub M, Lézot F, Molla M, Castaneda B, Robert B, et al. (2007) Msx-2−/− transgenic mice develop compound amelogenesis imperfecta, dentinogenesis imperfecta and periodental osteopetrosis. Bone 41: 851–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berdal A, Castaneda B, Aïoub M, Néfussi JR, Mueller C, et al. (2011) Osteoclasts in the dental microenvironment: a delicate balance controls dental histogenesis. Cells Tissues Organs 194 (2–4) 238–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Molla M, Descroix V, Aïoub M, Simon S, Castañeda B, et al. (2010) Enamel protein regulation and dental and periodontal physiopathology in MSX-2 mutant mice. Am J Pathol 177: 2516–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Amling M, Neff L, Priemel M, Schilling AF, Rueger JM, et al. (2000) Progressive increase in bone mass and development of odontomas in aging osteopetrotic c-src-deficient mice. Bone 27 (5) 603–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lu X, Rios HF, Jiang B, Xing L, Kadlcek R, et al. (2009) A new osteopetrosis mutant mouse strain (ntl) with odontoma-like proliferations and lack of tooth roots. Eur J Oral Sci 117 (6) 625–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Duheron V, Hess E, Duval M, Decossas M, Castaneda B, et al. (2011) Receptor activator of NF-kappaB (RANK) stimulates the proliferation of epithelial cells of the epidermo-pilosebaceous unit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 5342–5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Castaneda B, Simon Y, Jacques J, Hess E, Choi YW, et al. (2011) Bone resorption control of tooth eruption and root morphogenesis: Involvement of the receptor activator of NF-kB (RANK). J Cell Physiol 226: 74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davideau JL, Demri P, Hotton D, Gu TT, MacDougall M, et al. (1999) Comparative study of MSX-2, DLX-5, and DLX-7 gene expression during early human tooth development. Pediatr Res 46 (6) 650–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lézot F, Thomas B, Greene SR, Hotton D, Yuan ZA, et al. (2008) Physiological implications of DLX homeoproteins in enamel formation. J Cell Physiol 213: 688–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Diamond E, Amen M, Hu Q, Espinoza HM, Amendt BA (2006) Functional interactions between Dlx2 and lymphoid enhancer factor regulate Msx2. Nucleic Acids Res 34 (20) 5951–5965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yoneda T, Hiraga T (2005) Crosstalk between cancer cells and bone microenvironment in bone metastasis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 328: 679–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stelnicki E, Kömüves LG, Holmes D, Clavin W, Harrison MR, et al. (1997) The human homeobox genes MSX-1, MSX-2, and MOX-1 are differentially expressed in the dermis and epidermis in fetal and adult skin. Differenciation 62: 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gremel G, Ryan D, Rafferty M, Lanigan F, Hegarty S, et al. (2011) Functional and prognostic relevance of the homeobox protein MSX2 in malignant melanoma. Br J Cancer 105: 565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Depondt J, Shabana el-H, Walker F, Pibouin L, Lezot F, et al. (2008) Nasal inverted papilloma expresses the muscle segment homeobox gene Msx2: possible prognostic implications. Hum Pathol 39: 350–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ruhin-Poncelet B, Ghoul-Mazgar S, Hotton D, Capron F, Jaafoura MH, et al. (2009) Msx and Dlx homeogene expression in epithelial odontogenic tumors. J Histochem Cytochem 57: 69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Qian Y, Huang HZ (2010) The role of RANKL and MMP-9 in the bone resorption caused by ameloblastoma. J Oral Pathol Med 39: 592–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morris MA, Ley K (2004) Trafficking of Natural Killer Cells. Curr Mol Med 4 (4) 431–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Soderquest K, Powell N, Luci C, van Rooijen N, Hidalgo A, et al. (2011) Monocytes control natural killer cell differentiation to effector phenotypes. Blood 117: 4511–4518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Redlich K, Smolen JS (2012) Inflammatory bone loss: pathogenesis and therapeutic intervention. Nat Rev Drug Discov 11 (3) 234–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grassi F, Piacentini A, Cristino S, Toneguzzi S, Cavallo C, et al. (2003) Human osteoclasts express different CXC chemokines depending on cell culture substrate: molecular and immunocytochemical evidence of high levels of CXCL10 and CXCL12. Histochem Cell Biol 120: 391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee Y, Chittezhath M, André V, Zhao H, Poidinger M, et al. (2012) Protumoral role of monocytes in human B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: involvement of the chemokine CXCL10. Blood 119: 227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kwak HB, Ha H, Kim HN, Lee JH, Kim HS, et al. (2008) Reciprocal cross-talk between RANKL and interferon-gamma-inducible protein 10 is responsible for bone-erosive experimental arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 58: 1332–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lei SF, Wu S, Li LM, Deng FY, Xiao SM, et al. (2009) An in vivo genome wide gene expression study of circulating monocytes suggested GBP1, STAT1 and CXCL10 as novel risk genes for the differentiation of peak bone mass. Bone 44 (5) 1010–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Coelho LF, Magno de Freitas Almeida G, Mennechet FJ, Blangy A, Uzé G (2005) Interferon-α and –β differentially regulate osteoclastogenesis: Role of differential induction of chemokine CXCL11 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 11917–11922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heise CE, Pahuja A, Hudson SC, Mistry MS, Putnam AL, et al. (2005) Pharmacological characterization of CXC chemokine receptor 3 ligands and a small molecule antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 313 (3) 1263–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Comparative analysis of epithelial rest of Malassez sizes in roots of wild type, Msx2−/− and Msx2−/− RankTg mice. Whatever the age considered, the RANK over-expression in the Msx2−/− mouse normalized the size of the rest of Malassez. Measures were realized as previously described [5] using Image-J software.

(TIF)

Van Gieson staining of Msx2−/− mouse mandible first molar frontal sections at 3, 4 and 16 weeks.The presence of a cyst-like structure at the root lingual surface was observed at 3 weeks (a). At 4 and 16 weeks lacunae in the dentin area facing the site of transition between crown and root epithelium was present (asterisk in b–c). D: dentine; PDL: periodontal ligament; P: pulp.

(TIF)

Table of the TaqMan immune arrays results. Numbers corresponded to the induction folds observed in the 14 day-old Msx2−/− RANKTg mouse tissues comparatively to Msx2−/− mouse tissues. Negative numbers corresponded to reduction folds and ND means that no expression difference has been detected. Inductions over 4 folds have been reported in Figure 6.

(DOCX)

Combined effects of loss of Msx2 and Rank overexpression on mouse skull, tibia and molar phenotypes. Upper and lateral scan-views of skulls of 14 day-old wild type, RANKTg, Msx2−/− and Msx2−/− RANKTg mice (a) enabled to see a significant reduction of the open foramen in the Msx2−/− RANKTg mouse comparatively to Msx2−/− mouse while sutures were normal in RANKTg mouse as in WT mouse. Scan-sections along tibias of 14 day-old WT, RANKTg, Msx2−/− and Msx2−/− RANKTg mice (b) evidenced that RANK over-expression moderately increased Msx2−/− mouse tibia length without reached the normal size seen in RANKTg and WT mice. BV/TV measures on sections realized at 50, 30 and 15% of tibias length evidenced that RANK over-expression is able to reverse the mild osteopetrosis phenotype seen in Msx2−/− mouse toward a rather osteopenic phenotype also visible in RANKTg mouse. Lateral scan-views of mandible first molars of 14 day-old wild type, RANKTg, Msx2−/− and Msx2−/− RANKTg mice (c) enabled to see a significant reduction of the mesial root length in Msx2−/− and Msx2−/− RANKTg mice comparatively to WT mouse with however a longer root in Msx2−/− RANKTg mouse comparatively to Msx2−/− mouse.

(TIF)