Background: The roles of histone demethylase Jmjd3 in osteoblasts are not fully understood.

Results: Jmjd3 expression increased during osteoblast differentiation. Silencing of Jmjd3 impaired osteoblast differentiation. Introduction of the exogenous Runx2 and osterix partly rescued osteoblast differentiation in shJmjd3 cells.

Conclusion: Jmjd3 regulates osteoblast differentiation via transcription factors Runx2 and osterix.

Significance: This study provides new insights about the roles of Jmjd3 in osteoblast differentiation.

Keywords: Bone, Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), Differentiation, Histone methylation, Osteoblasts

Abstract

Post-translational modifications of histones including methylation play important roles in cell differentiation. Jumonji domain-containing 3 (Jmjd3) is a histone demethylase, which specifically catalyzes the removal of trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3). In this study, we examined the expression of Jmjd3 in osteoblasts and its roles in osteoblast differentiation. Jmjd3 expression in the nucleus was induced in response to the stimulation of osteoblast differentiation as well as treatment of bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2). Either treatment with Noggin, an inhibitor of BMP-2, or silencing of Smad1/5 suppressed Jmjd3 expression during osteoblast differentiation. Silencing of Jmjd3 expression suppressed osteoblast differentiation through the expression of bone-related genes including Runx2, osterix, osteopontin, bone sialoprotein (BSP), and osteocalcin (OCN). Silencing of Jmjd3 decreased the promoter activities of Runx2 and osterix and increased the level of H3K27me3 on the promoter regions of Runx2 and osterix. Introduction of the exogenous Runx2 and osterix partly rescued osteoblast differentiation in the shJmjd3 cells. The present results indicate that Jmjd3 plays important roles in osteoblast differentiation and regulates the expressions of BSP and OCN via transcription factors Runx2 and osterix.

Introduction

Bone is a dynamic tissue that undergoes continuous remodeling through bone formation and resorption. Osteoblasts are responsible for bone formation, whereas osteoclasts are responsible for bone resorption. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2)2 is a critical autocrine and paracrine growth factor for bone formation, which is produced by many types of cells including osteoblasts (1–3). BMP transduces its signal via the intracellular downstream mediators Smads. Upon activation of BMP pathway, Smad1 and Smad5 are phosphorylated and interact with Smad4 to enter the nucleus to regulate their target genes including Runx2 and osterix (4). Both Runx2 and osterix are important transcription factors for osteoblast differentiation and control the expressions of bone-related genes such as osteopontin (OPN), bone sialoprotein (BSP), and osteocalcin (OCN) (5–10). These bone-related genes are required for the terminal osteoblast differentiation and bone mineralization (11, 12).

Eukaryotic DNA is packaged into chromatin whose basic repeating unit is a nucleosome. The nucleosome consists of packaged DNA and an octamer of the core histones, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. Histones have their flexible tails extending from the nucleosomal core, which are subjected to numerous modifications such as methylation, acetylation, ubiquitination, and phosphorylation. These modifications change chromatin activity for gene transcription. Site-specific histone methylation on lysine (K), being either monomethylation (me1), dimethylation (me2), or trimethylation (me3), enables the gene promoter region to be accessible or inaccessible for transcription factors. Histone methylation plays a pivotal role during cell commitment and differentiation in many types of cells (13–15). Trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine-4, -36, and -79 (H3K4, H3K36, and H3K79) is implicated in transcriptional activation, whereas trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine-9 and -27 (H3K9 and H3K27) is associated with transcriptional repression (16, 17). Histone methylation has been demonstrated to be reversible and can be eliminated by demethylases (18, 19).

Jumonji domain-containing 3 (Jmjd3) has been identified as a histone demethylase, which specifically catalyzes the removal of trimethylation of histone H3K27 (H3K27me3). Jmjd3 is regulated by a variety of differentiation cues and stress signals in macrophages (20), neuronal stem cells (21), and epidermal cells (22). In addition, Jmjd3-induced demethylation of H3K27me3 in the transcription start site of Nfatc1 gene plays a critical role in osteoclast differentiation (23). However, the roles of Jmjd3 in osteoblasts are not fully understood.

In this study, we examined the expression and subcellular localization of Jmjd3 in osteoblasts. Jmjd3 expression in the nucleus was induced during osteoblast differentiation. Silencing of Jmjd3 expression suppressed osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Silencing of Jmjd3 also increased the level of H3K27me3 on the promoter regions of Runx2 and osterix. Introduction of the exogenous Runx2 and osterix recovered the osteoblast differentiation and expressions of BSP and OCN in the Jmjd3 knockdown cells. These findings indicate that Jmjd3 plays important roles in the osteoblast differentiation via Runx2 and osterix transcription factors.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

α-Modified Eagle's minimal essential medium was purchased from Invitrogen. Plastic dishes were from IWAKI (Chiba, Japan), and fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from JRH Biosciences (Lenexa, KS). Antibody against Jmjd3 was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Antibodies against H3K27me3, H3K4me3, H3K9me3, H3K36me3, and H3 were obtained from Takara (Kyoto, Japan). Anti-B23 and anti-Eps15 antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). Anti-FLAG and anti-β-actin antibodies, ascorbic acid, β-glycerophosphate, Fast Red TR, naphthol AS-MX phosphate, and calcein were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Atelocollagen was from KOKEN (Tokyo, Japan). The other materials used were of the highest grade commercially available.

Cell Culture

Cells were cultured in α-modified Eagle's minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% FBS (growth medium) at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. For the induction of osteoblast differentiation, the growth medium was supplemented with 50 μm ascorbic acid and 10 mm β-glycerophosphate (osteoblast differentiation medium). For recombinant human BMP-2 treatment, cells were treated with 100 ng/ml BMP-2 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in growth medium. For the experiments using inhibitors, cells were pretreated with 100 ng/ml Noggin (R&D Systems), 100 nm U0126 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) or 50 μm LY294002 (Promega, Madison, WI) for 3 h and then cultured in the osteoblast differentiation medium for another 72 h.

RNA Preparation and Real-time PCR Analysis

Cells were homogenized in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's protocol. Reverse transcription was carried out with PrimeScript reverse transcription kit (Takara). Real-time PCR of each gene was performed in triplicate for at least three independent experiments with a 7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM (Takara). The sequences of the primers were as follows: Gapdh, forward, 5′-TGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTGA-3′, reverse, 5′-TTGCTGTTGAAGTCGCAGGAG-3′; Jmjd3, forward, 5′-CTGCTGTAACCCACTGCTGGA-3′, reverse, 5′-GAAAGCCAATCATCACCCTTGTC-3′; Smad1, forward, 5′-CTCAGCTTGCTGCCTTAAACAGAC-3′, reverse, 5′-CCGTGGAGCGGATAAGACAGA-3′; Smad5, forward, 5′-TGCAGCTTGACCGTCCTTACC-3′, reverse, 5′-GCCATCGTCTGCTCTGCATC-3′; Runx2, forward, 5′-CATTTGCACTGGGTCACACGTA-3′, reverse, 5′-GAATCTGGCCATGTTTGTGCTC-3′; osterix, forward, 5′-CTTCCCAATCCTATTTGCCGTTT-3′, reverse, 5′-CGGCCAGGTTACTAACACCAATCT-3′; BSP, forward, 5′-GAGCCTCGTGGCGACACTTA-3′, reverse, 5′-AATTCTGACCCTCGTAGCCTTCATA-3′; OCN, forward, 5′-CCGGGAGCAGTGTGAGCTTA-3′, reverse, 5′-AGGCGGTCTTCAAGCCATACT-3′; OPN, forward, 5′-TACGACCATGAGATTGGCAGTGA-3′, reverse, 5′-TATAGGATCTGGGTGCAGGCTGTAA-3′; exogenous osterix, forward, 5′-ATGGACTACAAGGACGACGAC-3′, reverse, 5′-CGGCCAGGTTACTAACACCAATCT-3′; and exogenous Runx2, forward, 5′-AAAAGCCTGCCTAACTGCAA-3′, reverse, 5′-CCGGGCTGCAGGCTGCTGGA-3′.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blot Analysis

Cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then scraped into lysate buffer (1 mm DTT, 1 mm PMSF, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 mm EGTA). The protein concentration was determined by using protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad) and diluted to a concentration of 1 mg/ml with lysate buffer. Twelve μg of each sample and prestained molecular weight markers were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Medford, MA). The membranes were incubated for 2 h at ambient temperature in a blocking solution consisting of 5% nonfat skim milk in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-Tween), washed briefly in PBS-Tween, and then incubated overnight at 4 °C in 5% nonfat skim milk in PBS-Tween containing specific antibodies (diluted at 1:1,000). After the membranes had been washed four times within 30 min in PBS-Tween, they were incubated at ambient temperature for 2 h in PBS-Tween containing horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (diluted at 1:5,000). The membranes were then washed again as described above, and the proteins recognized by the antibodies were visualized with an ECL detection kit (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer's directions.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were grown on sterile 18-mm round glass coverslips placed in 60-mm plastic dishes. After washing three times with PBS, cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min at ambient temperature followed by methanol permeabilization for an additional 20 min at −20 °C. Having been blocked with 4% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 40 min in a humidified atmosphere, the cells were incubated at 4 °C overnight with anti-Jmjd3 or anti-FLAG antibodies diluted 1:200 in the blocking solution. After three washes with PBS over a 20-min period, they were next incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 goat IgG (Invitrogen) for 40 min and 10 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 for 20 min, both diluted 1:500 in 4% BSA. The coverslips were washed with PBS and mounted with fluorescent mounting medium (DakoCytomation, Carpentaria, CA). The cells were examined under an Olympus BX50 (Tokyo, Japan) microscope equipped with epifluorescence illumination using a U-MNIBA and a WU filter for green and blue fluorescence, respectively. Photomicrographs were recorded on a computer (Olympus, DP70-WPCXP). The blue color was reconstituted to the pseudo-red color by using PP imager software (Olympus).

Extraction of Cytosolic and Nuclear Preparations

For cytosolic and nuclear preparation, cells were lysed with hypotonic buffer (100 mm HEPES, pH 7.9, 15 mm MgCl2, 100 mm KCl, 1 mm DTT, and protease inhibitors) and incubated on ice for 15 min. To the swollen cells in lysis buffer, 10% IGEPAL CA-630 solution was added and centrifuged at 11,000 × g for 5 min. The cytosolic preparation was recovered in the supernatant, whereas the nuclear pellet was resuspended in the buffer containing 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.9, 15 mm MgCl2, 0.42 m NaCl, 0.2 mm EDTA, 25% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mm DTT, and protease inhibitors and then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 5 min. The nuclear preparation was recovered in the supernatant.

Small Interfering RNA (siRNA) and Short Hairpin RNA (shRNA) Transfection

For transient silencing of Jmjd3, MC3T3-E1 cells were transfected with stealth siRNA targeting Jmjd3 (Invitrogen) with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) (siJmjd3). Nonspecific siRNA (Invitrogen) was also transfected as a negative control (siCont). For establishment of stable Jmjd3 knockdown cells, MISSION® shRNA lentiviral transduction particles for Jmjd3 (Sigma-Aldrich) were infected into the cells according to the manufacturer's directions and selected stable clones via puromycin (5 μg/ml) treatment (shJmjd3). MISSION® nontargeted shRNA lentiviral transduction particles were used as a negative control (shCont). The target sites were as follows: siJmjd3, 5′-GAGCCTGCCTACTACTGCAACGAAT-3′; siSmad1, 5′-CCTGCTGGATTGAGATCCATCTGCA-3′; siSmad5, 5′-CCCATGTTATATATTGCCGTGTTTG-3′; siCont, siRNA Negative Control Med GC Duplex #3 (12935-113, Invitrogen); shJmjd3, 5′-CCGGCCTGTTCGTTACAAGTGAGAACTCGAGTTCTCACTTGTAACGAACAGGTTTTTG-3′; and shCont, 5′-CCGGCAACAAGATGAAGAGCACCAACTCGAGTTGGTGCTCTTCATCTTGTTGTTTTT-3′.

Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Staining

Cultured cells in the osteoblast differentiation medium for 7 days were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min and stored at 4 °C in 100 mm cacodylic acid buffer (pH 7.4). The cells were then incubated at 37 °C with freshly prepared alkaline phosphatase substrate solution (100 mm Tris-maleate buffer (pH 8.4), 2.8% N,N-dimethyl formamide (v/v), 1 mg/ml Fast Red TR, and 0.5 mg/ml naphthol AS-MX phosphate). The reaction was terminated after 30 min by removal of the substrate solution and washing with 100 mm cacodylic acid buffer.

ALP Activity Assay

Cultured cells in the osteoblast differentiation medium for 7 days were scraped into ice-cold 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4), sonicated for 20 s using a Sonifier cell disruptor (model UR-20P; TOMY, Tokyo, Japan), and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The ALP activity in the supernatant was then determined using p-nitrophenyl phosphate as a substrate according to the manufacturer's instructions. The ALP activity was normalized to protein content as measured by protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad).

Mineral Apposition and Quantification

For von Kossa staining, cells cultured for 14 days in the osteoblast differentiation medium were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min, washed in cacodylic acid buffer, pH 7.4, incubated in saturated lithium carbonate, and subsequently incubated in 3% AgNO3 (w/v) for 30 s under ultraviolet light. The cells were rinsed with water and air-dried. For Alizarin red staining, cells cultured for 14 days in the osteoblast differentiation medium were washed twice with PBS, fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min, and then stained with 0.1% Alizarin red (Sigma-Aldrich) at pH 6.3 for 10 min. For calcium measurement, cell lysates were collected in lysate buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) from the cells cultured for 21 days in the osteoblast differentiation medium and used for calcium measurement by using the calcium assay kit (Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI). According to the manufacturer's directions, the reaction was measured spectrophotometrically at 590 nm. Calcium content was normalized to protein content measured by protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad).

Animal Studies

All mice studied were reared in our specific pathogen-free mouse colony and given food and water ad libitum. Experiments were humanely conducted under the regulation and permission of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Tokushima, Tokushima, Japan. For local injection, equal volumes of atelocollagen and siRNA (siCont or siJmjd3, 10 μm final concentration) were mixed on ice. Fifty μl of the mixture was injected subcutaneously into the calvarial region on day 3 and day 7 after birth. Briefly, a 27-gauge needle was inserted at the base of the calvaria and pushed until it reached to the central region of the skull. Solution was then injected over the parietal region of the skull. To measure bone mineralization rate, the mice were injected with calcein at concentration of 20 mg/kg on day 6 and day 10 after birth as described above. On day 12, mice were sacrificed and calvaria were dissected.

Microcomputed Tomography (μCT) Analysis of Bone

Dissected mice calvaria were fixed and analyzed by a μCT system (Latheta LCT-2000, Aloka, Tokyo, Japan). Bone mineral density (mg/cm3) was also calculated by μCT analysis.

Histological Analysis

After using for μCT analysis, dissected mice calvaria were embedded in plastic and sectioned at 7 μm. Sections were observed as green fluorescence given from calcein labeling. Trichrome staining was performed using Masson-Goldner staining kit (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer's directions. Von Kossa staining was achieved by incubation with 3% silver nitrate for 5 min, soda-formol solution for 5 min, and 5% sodium thiosulfate for 5 min and counterstaining with Van Gieson solution for 3 min.

Reporter Constructs and Luciferase Assay

Osterix promoter −355/+91 and −786/+91 reporters were kindly gifted from Drs. Tohmonda and Horiuchi (Keio University, Japan). To clone the 5′ upstream region of Runx2 gene, −625 to +1 bp of the Runx2 gene were amplified by PCR from DNA extracted from MC3T3-E1 cells. PCR product was digested with XhoI and HindIII and inserted into the pGL3 basic luciferase reporter vector (Promega). Three copies of Runx2 binding site AACCACA were inserted into the pGL3 basic luciferase reporter vector (Promega), and the recombinant plasmid was designated as Runx2 3×binding site. For luciferase assays, 70–80% confluent cells in 24-well dishes were transfected with 0.5 μg of promoter reporter vector using Lipofectamine LTXTM reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's directions. The cells were also co-transfected with 0.05 μg of pTK-Renilla (Promega) to normalize for transfection efficiency. pGL3 basic vector (Promega) was used for empty vector as control. After 24 h after transfection, total cell lysates were prepared using Dual-Glo® luciferase assay system (Promega) and assessed for luciferase activity.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

ChIP assay was carried out using previously described procedures (24). Briefly, the shCont and shJmjd3 cells were cultured for 3 days in the osteoblast differentiation medium and chemically cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min at ambient temperature. Cells were lysed, sonicated, and immunoprecipitated with 4 μg of antibodies preabsorbed with 40 μl of protein A beads overnight at 4 °C. After several washes, the complexes were eluted, and the cross-linking was reversed by overnight incubation at 65 °C. Extracted (input) and immunoprecipitated DNA were then purified by the treatment with RNase A, proteinase K, and multiple of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol. PCR was performed with the primers corresponding to the promoter regions of Runx2 and osterix as follows: Runx2 promoter primers 1:, forward, 5′-AAGGAGTTTGCAAGCAGAGC-3′, reverse, 5′-CAACTGAGTGTGTGGCGTTC-3′; Runx2 promoter primers 2, forward, 5′-GGCTCCTTCAGCATTTGTGT-3′, reverse, 5′-TGTCCTCTCCCTTTCCTTCC-3′; osterix promoter primers 1, forward, 5′-CAGAGAGTACGTGTGCATGC-3′, reverse, 5′-GCTGCTGAGGAAAGGAACAG-3′; and osterix promoter primers 2, forward, 5′-GAAGCTCTGACAACTTGCCC-3′, reverse, 5′-AAGGGAGAGGGAGGGAGAAT-3′.

Transfection

The shJmjd3 cells at 70–80% confluence were transfected with FLAG-osterix expression vector (25) or Runx2 (Promega, Flexi HaloTag clone pFN21AB9739) expression vector using Lipofectamine LTXTM reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The pcDNA3.1 FLAG empty vector transfection was used as negative control. After 2 days of incubation, the cells were examined by immunocytochemistry, mineral apposition and quantification, and real-time PCR as described above.

Statistical Analysis

Each series of experiments was repeated at least three times, and all the data were expressed as mean values ± S.E. Statistical analyses were performed by analysis of variance. Statistical significance was indicated with (*, p value <0.05) or (**, p value <0.01).

RESULTS

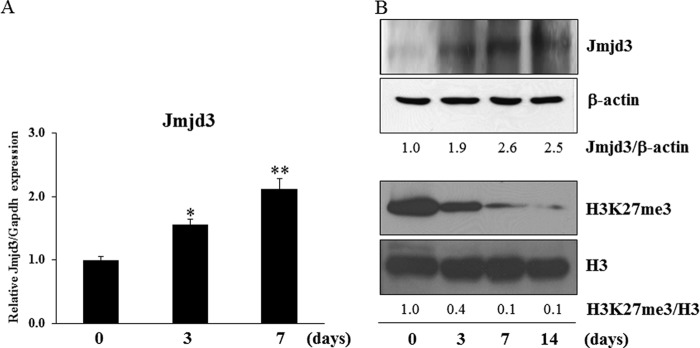

Jmjd3 Expression Increased during Osteoblast Differentiation

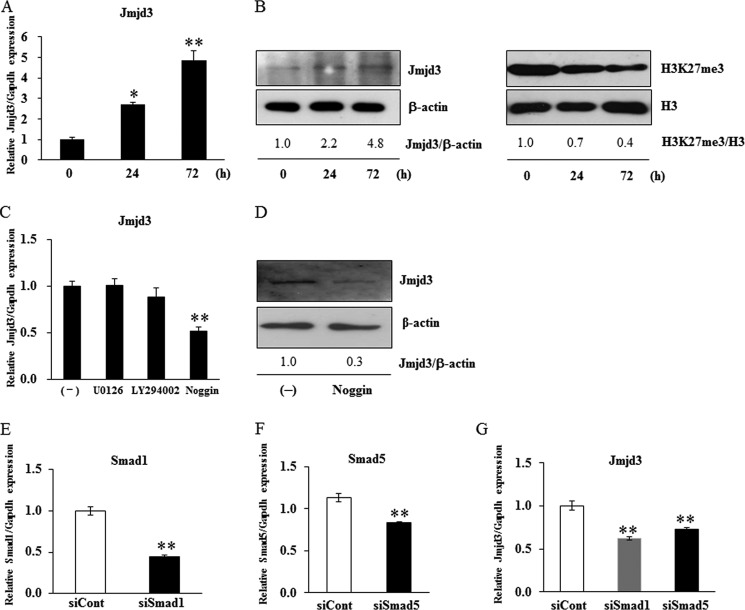

The level of Jmjd3 mRNA expression in MC3T3-E1 cells cultured in the osteoblast differentiation medium increased in a time-dependent manner, as determined by real-time PCR (Fig. 1A). From Western blot analysis, the intensity of a band corresponding to Jmjd3 increased while that of H3K27me3 decreased during osteoblast differentiation (Fig. 1B). The levels of β-actin and H3, used as internal controls, did not change during the culture period (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

The expression of Jmjd3 in osteoblasts. MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured in the osteoblast differentiation medium for the indicated periods. A, the expression of Jmjd3 was examined by real-time PCR. B, the protein expressions of Jmjd3 and H3K27me3 were examined by Western blot analysis. The relative expressions of Jmjd3/β-actin and H3K27me3/H3 were calculated by computer software (ImageJ). All the results in the real-time PCR are presented as means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01

BMP-2 Induced Jmjd3 Expression in Osteoblasts

To examine the effect of BMP-2 on Jmjd3 expression, MC3T3-E1 cells were treated with 100 ng/ml BMP-2 for 72 h. BMP-2 stimulated the expression of Jmjd3 in a time-dependent manner, as determined by real-time PCR (Fig. 2A). Expression of Jmjd3 protein also increased while that of H3K27me3 decreased in MC3T3-E1 cells treated with BMP-2 (Fig. 2B). We further examined whether BMP-2 signaling would be involved in the Jmjd3 expression in MC3T3-E1 cells cultured in the osteoblast differentiation medium. Cells were pretreated for 3 h with 100 nm U0126 (MAPK inhibitor), 50 μm LY2940002 (PI3K inhibitor), or 100 ng/ml Noggin (BMP-2 antagonist) and then continued to culture in the osteoblast differentiation medium for another 72 h. Noggin, but not U0126 and LY2940002, decreased the expression levels of Jmjd3 mRNA and protein (Fig. 2, C and D). Furthermore, silencing of Smad1 and Smad5, which are transducers of BMP-2 signal, also decreased Jmjd3 expression in the cells treated with BMP-2 (Fig. 2, E–G).

FIGURE 2.

BMP-2 induced Jmjd3 expression in osteoblasts. MC3T3-E1 cells were treated with 100 ng/ml BMP-2 for the indicated periods. A and B, the expression levels of Jmjd3 and H3K27me3 were examined by real-time PCR (A) and Western blot analysis (B). MC3T3-E1 cells were pretreated with 100 nm U0126, 50 μm LY294002, or 100 ng/ml Noggin for 3 h and cultured for another 72 h in the osteoblast differentiation medium. C and D, Jmjd3 expression was examined by real-time PCR (C) and Western blot analysis (D). MC3T3-E1 cells were transfected with siRNA for Smad1 or Smad5 and cultured in the medium containing 100 ng/ml BMP-2 for another 72 h. E–G, the expressions of Smad1 (E), Smad5 (F), and Jmjd3 (G) were examined by real-time PCR. The relative expressions of Jmjd3/β-actin and H3K27me3/H3 were calculated by computer software (ImageJ). All the data in the real-time PCR are presented as means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01.

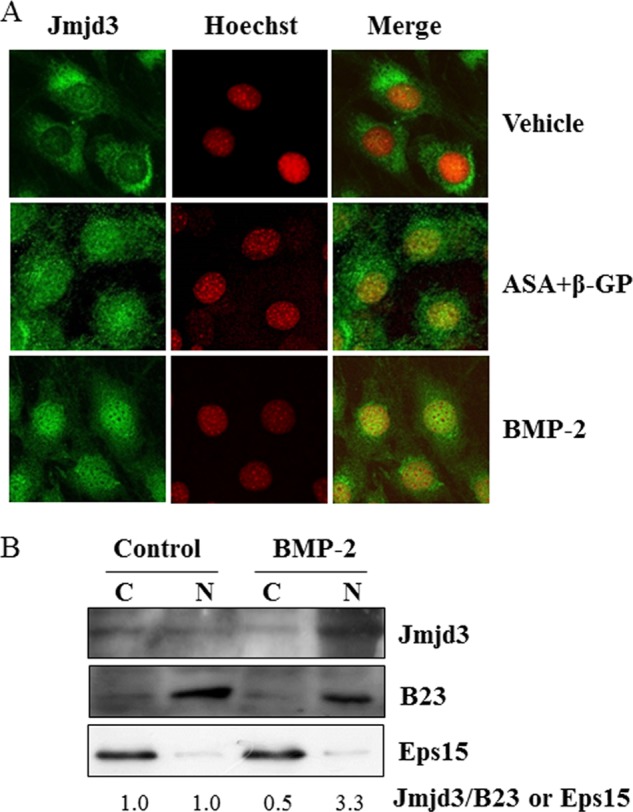

Nuclear Localization of Jmjd3 in Osteoblasts

To determine the localization of Jmjd3 in osteoblasts, MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured for 7 days in the osteoblast differentiation medium or treated with BMP-2 for 3 days. The cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-Jmjd3 antibody. In the untreated cells, Jmjd3 was mainly localized in the cytosol. However, in the cells cultured in the osteoblast differentiation medium or treated with BMP-2, Jmjd3 was mainly detected in the nucleus (Fig. 3A). To confirm the localization of Jmjd3 in the nucleus, nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were prepared from MC3T3-E1 cells treated with BMP-2 and analyzed by Western blotting. Fig. 3B shows that the level of Jmjd3 protein increased in the nuclear fraction in the cells treated with BMP-2. The purity of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions was confirmed by the presence of B23 and Eps15, respectively. Localization of Jmjd3 indicates that the Jmjd3 expression in the nucleus was induced during osteoblast differentiation.

FIGURE 3.

Nuclear localization of Jmjd3. A, MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured for 7 days in the osteoblast differentiation medium or treated with 100 ng/ml BMP-2 for 72 h. The localization of Jmjd3 was determined by immunocytochemistry. B, MC3T3-E1 cells were treated without (Control) or with 100 ng/ml BMP-2 (BMP-2). Seventy-two hours later, the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were prepared. Western blot analysis was performed using the specific antibodies for Jmjd3, B23, and Eps15. The relative expression of Jmjd3/B23 or Eps15 was calculated by computer software (ImageJ). C, cytosolic fraction; N, nuclear fraction.

Silencing of Jmjd3 Expression Impaired Differentiation and Mineralization in Osteoblasts

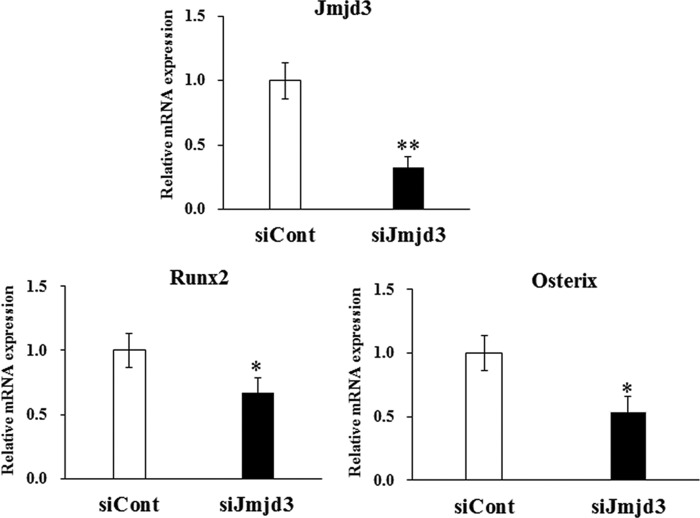

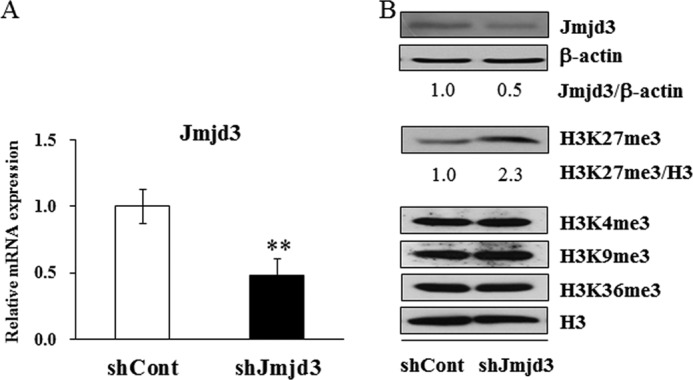

To examine the role of Jmjd3 in osteoblast differentiation, gene silencing experiments were performed. Transient silencing of Jmjd3 by siRNA transfection into MC3T3-E1 cells markedly suppressed the expressions of Runx2 and osterix as compared with those in the siCont cells, as determined by real-time PCR (Fig. 4). The stable Jmjd3 knockdown MC3T3-E1 cells were established by infecting the lentivirus expressing shRNA specific for Jmjd3 (shJmjd3). MC3T3-E1 cells infected with nonspecific shRNA were used as a control (shCont). As expected, the expression of Jmjd3 significantly decreased in the shJmjd3 cells as compared with that in the shCont cells, as determined by real-time PCR (Fig. 5A) and Western blot analysis (Fig. 5B). There are no differences in the rate of cell proliferation in shCont and shJmjd3 cells (data not shown). Fig. 5B also shows that shJmjd3 cells displayed increased level of H3K27me3, whereas the levels of H3K4me3, H3K9me3, and H3K36me3 were unaffected. The levels of β-actin and H3 did not change in these cells (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 4.

Suppression of Runx2 and osterix expression in Jmjd3 transient silencing cells. MC3T3-E1 cells were transfected with nonspecific (siCont) or Jmjd3-specific (siJmjd3) siRNA and cultured for 3 days in the osteoblast differentiation medium. RNA was extracted, and real-time PCR was performed for Jmjd3, Runx2, and osterix. All the data are presented as means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01.

FIGURE 5.

Establishment of stable Jmjd3 knockdown cells. MC3T3-E1 cells were transfected with nonspecific (shCont) or Jmjd3-specific (shJmjd3) shRNA and cultured for 3 days in the osteoblast differentiation medium. A, the expression levels of Jmjd3 mRNA were examined by real-time PCR. Data are presented as means ± S.E. **, p < 0.01. B, Western blot analysis was performed using the specific antibodies for Jmjd3, β-actin, H3K27me3, and H3. The relative expressions of Jmjd3/β-actin and H3K27me3/H3 were calculated by computer software (ImageJ).

To further clarify the role of Jmjd3 in osteoblast differentiation, shCont and shJmjd3 cells were cultured for the indicated periods in the osteoblast differentiation medium, and ALP expression and mineralization were assessed by ALP, von Kossa, and Alizarin red staining (Fig. 6A). The intensity of the staining decreased in the shJmjd3 cells as compared with that in the shCont cells. In accordance with the staining results, ALP activity and calcium level were significantly decreased in the lysate from the shJmjd3 cells (Fig. 6, B and C, respectively). To investigate the molecular mechanism in the impaired osteoblast differentiation by Jmjd3 silencing, the expressions of several bone-related genes were examined in the shCont and shJmjd3 cells by real-time PCR. As shown in Fig. 6D, the expressions of Runx2, osterix, OPN, BSP, and OCN decreased in the shJmjd3 cells as compared with those in the shCont cells.

FIGURE 6.

Inhibition of osteoblast differentiation by Jmjd3 silencing. A, the shCont and shJmjd3 cells were cultured in the osteoblast differentiation medium for 7 and 14 days, respectively. The cells were stained for ALP expression (left panel) or for mineralization by von Kossa (central panel) and Alizarin red (right panel). B, the shCont and shJmjd3 cells were cultured for 7 days in the osteoblast differentiation medium, and ALP activity was measured. C, the shCont and shJmjd3 cells were cultured for 21 days in the osteoblast differentiation medium, and the calcium levels in the cultured cells were quantified. D, the shCont and shJmjd3 cells were cultured in the osteoblast differentiation medium. The mRNA expressions of Runx2 and osterix were determined on day 3 and those of OPN, BSP, and OCN were determined on day 7 by real-time PCR with normalization by Gapdh expression. Each bar represents the mean ± S.E. **, p < 0.01.

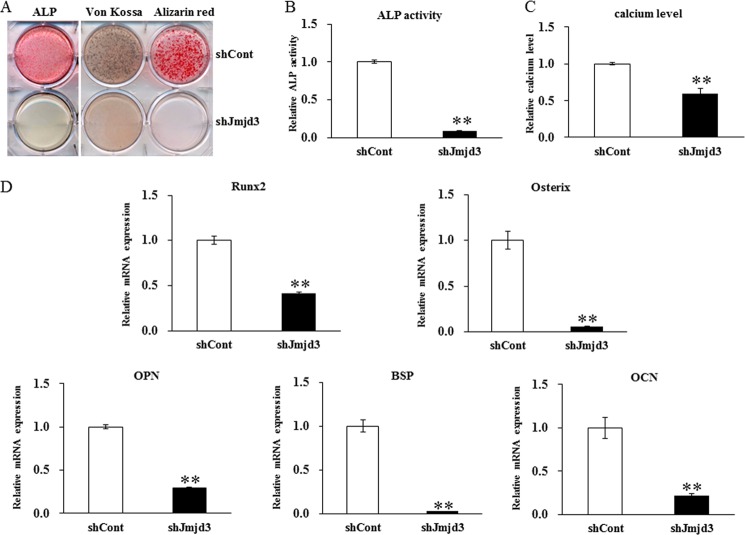

Local Administration of siJmjd3 Suppressed Bone Formation in Mouse Calvaria

To examine the role of Jmjd3 in bone formation in vivo, we subcutaneously administrated the mixture of siJmjd3 with atelocollagen into the calvarial region of mouse. Local administration of siJmjd3 suppressed bone formation in mouse calvaria, as demonstrated by three-dimensional μCT images (Fig. 7A). Cortical bone mineral density was lower in siJmjd3-injected mice versus siCont-injected ones (Fig. 7B). Goldner's trichrome staining and von Kossa staining showed that calvaria from the siJmjd3-injected mice had a decrease in bone thickness with lower mineralization as compared with those of siCont-injected mice. Injection of calcein twice at 4-day intervals indicated dynamic changes in bone mineral apposition. The distance between two consecutive labels in the calvaria was dramatically decreased in the siJmjd3-injected mice as compared with that of the controls (Fig. 7C).

FIGURE 7.

Local administration of siJmjd3 suppressed bone formation in mouse calvaria. A, three-dimensional μCT images of calvaria from mice (12-day-old, n = 4 for siJmjd3 injection, n = 4 for siCont injection) injected with siCont or siJmjd3. B, cortical bone mineral density (BMD) of calvaria was determined by μCT. Data are presented as means ± S.E. **, p < 0.01. C, upper, plastic sections of dissected mouse calvaria were examined under a fluorescence microscope. The distance between two calcein labeling layers reflects the bone mineralization rate. Middle, sections of dissected mice calvaria were stained with Goldner's trichrome to visualize bone thickness. Lower, sections of dissected mice calvaria were stained with von Kossa to visualize bone mineralization.

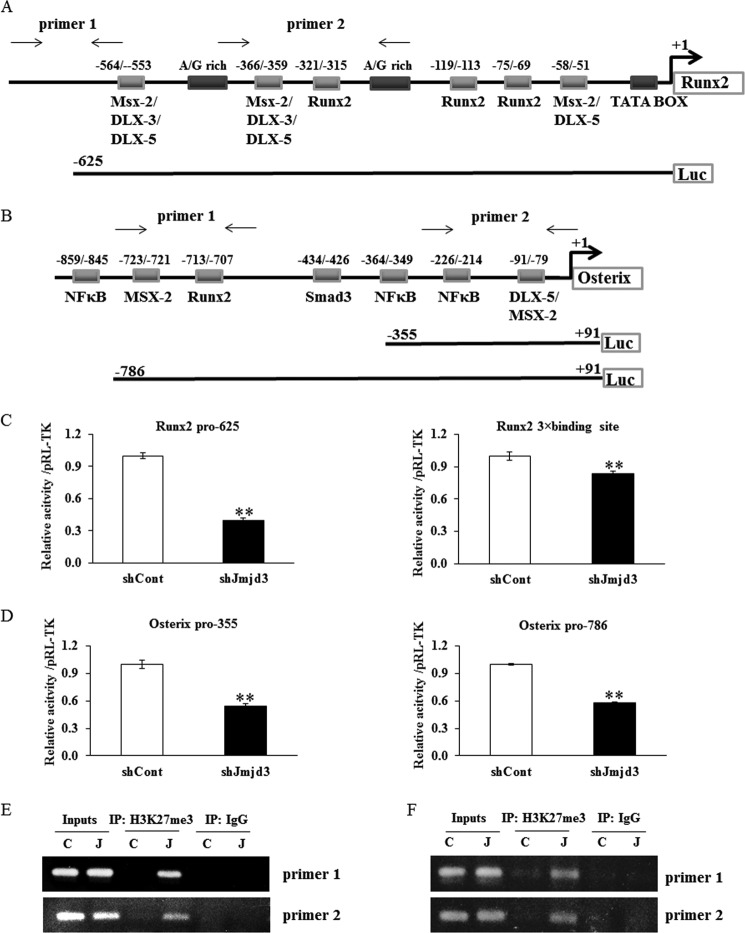

Jmjd3 Mediates the Level of H3K27me3 on the Promoter Regions of Runx2 and Osterix

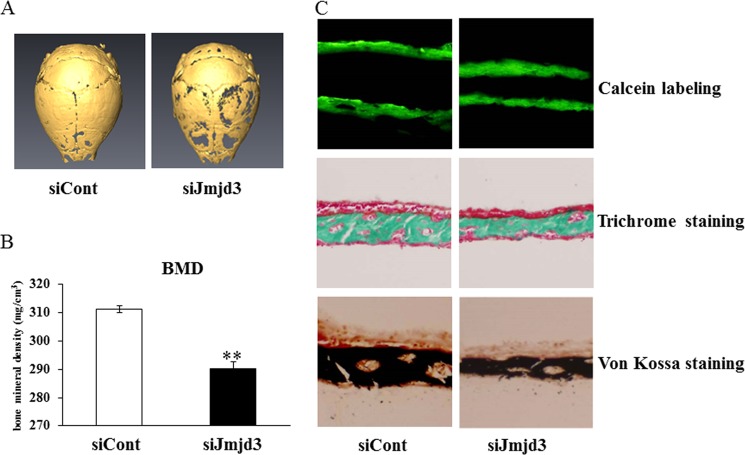

To study the mechanisms responsible for the suppression of osteoblast differentiation in shJmjd3 cells, we first examined the promoter activity of transcription factors, Runx2 and osterix. The schematic illustrations of Runx2 and osterix promoter regions were shown in Fig. 8, A and B, respectively. The luciferase activity of Runx2 (−625) and osterix (−786 and −355) promoters as well as Runx2 3×binding site decreased in shJmjd3 cells (Fig. 8, C and D). To assess whether the decreased activity could result from the changes of histone modification on the promoter region, ChIP assay was performed using anti-H3K27me3 antibody and the primers amplifying the regions of Runx2 and osterix promoter as indicated in Fig. 8, A and B. The corresponding bands were detected in the samples from shJmjd3 cells, but not in the shCont cells (Fig. 8, E and F). Input DNA and anti-IgG antibody-precipitated DNA were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

FIGURE 8.

Knockdown of Jmjd3 suppressed the transcriptional activity of Runx2 and osterix. A and B, schematic illustration of the promoter regions of Runx2 and osterix. The context of luciferase reporter vectors and the primers used for ChIP assay are indicated. C and D, the activity of Runx2 promoter, Runx2 3×binding site, and osterix promoter was decreased in shJmjd3 cells. E and F, knockdown of Jmjd3 increased the level of H3K27me3 on the Runx2 (E) and osterix (F) promoters. The shCont and shJmjd3 cells were cultured for 3 days in the osteoblast differentiation medium. Chromatin solution from the cells was subjected to ChIP analysis using anti-H3K27me3 and anti-IgG antibodies. PCR was performed with the primer pairs amplifying the promoter regions of Runx2 and osterix. IP, immunoprecipitate; C, shCont; J, shJmjd3.

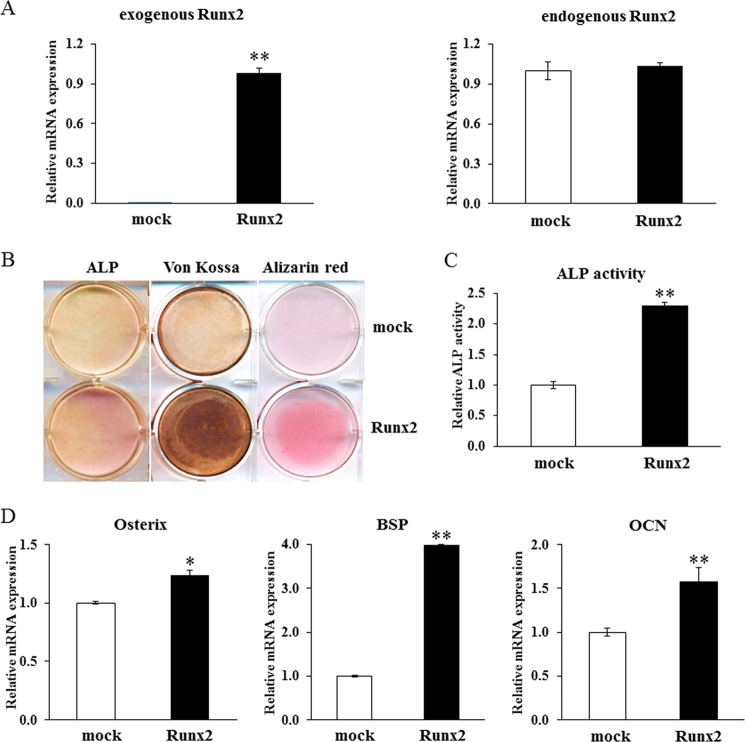

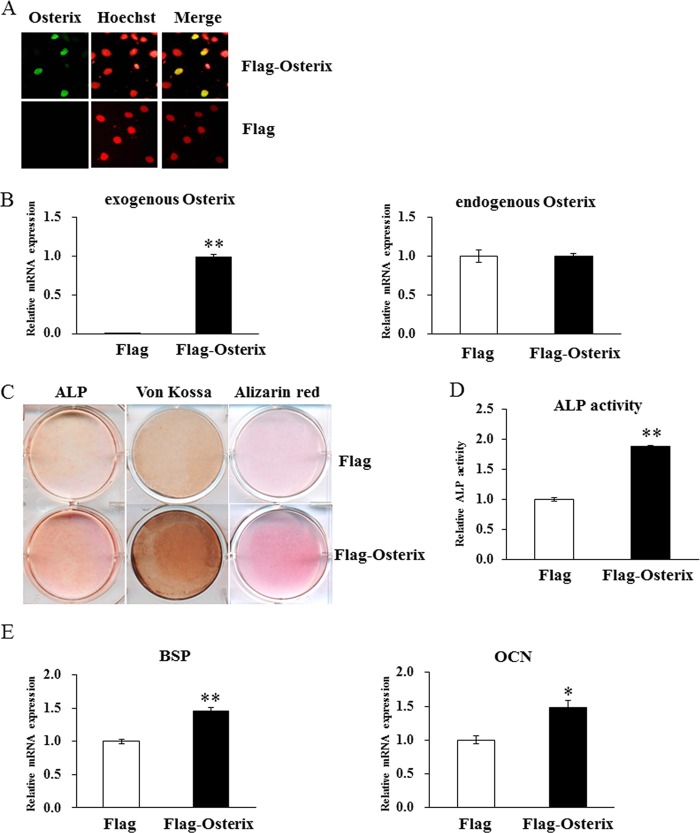

Introduction of Exogenous Runx2 and Osterix Rescued Osteoblast Differentiation in shJmjd3 Cells

To examine whether overexpression of Runx2 and osterix could rescue the impaired osteoblast differentiation in the shJmjd3 cells, Runx2 and osterix expression vectors were transfected into shJmjd3 cells. The expression of exogenous Runx2 was confirmed by real-time PCR (Fig. 9A). The densities of ALP, von Kossa, and Alizarin red staining and ALP activity were higher in the shJmjd3 cells transfected with Runx2 expression vector (Runx2) as compared with mock-transfected cells (mock) (Fig. 9, B and C). The expressions of osterix, BSP, and OCN increased in the Runx2 expression vector-transfected cells (Fig. 9D). Exogenous osterix expression was also confirmed by immunostaining using anti-FLAG antibody and real-time PCR (Fig. 10, A and B). As compared with the cells transfected with the empty vector (FLAG), osterix expression vector-transfected cells exhibited increased density of ALP, von Kossa, and Alizarin red staining, ALP activity, and expressions of BSP and OCN (Fig. 10, C–E).

FIGURE 9.

Overexpression of Runx2 partly rescued osteoblast differentiation in the shJmjd3 cells. The shJmjd3 cells were transfected with Runx2 expression vector. A, expressions of exogenous and endogenous Runx2 were examined by real-time PCR. B, cells were cultured in the osteoblast differentiation medium for 7 days for ALP staining (left panel) and 14 days for von Kossa (central panel) and Alizarin red staining (right panel). mock, mock-transfected cells. C, cells were cultured for 7 days in the osteoblast differentiation medium, and ALP activity was measured. D, the expressions of osterix, BSP, and OCN were determined by real-time PCR. All the data in the real-time PCR experiments are presented as means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01.

FIGURE 10.

Overexpression of osterix partly rescued osteoblast differentiation in the shJmjd3 cells. The shJmjd3 cells were transfected with empty vector (Flag) or osterix expression vector (Flag-Osterix). A, transfected osterix was confirmed by immunocytochemistry with anti-FLAG antibody. B, the exogenous and endogenous osterix expressions were examined by real-time PCR. C, cells were cultured in the osteoblast differentiation medium for 7 and 14 days, respectively. The cells were stained for ALP expression (left panel) or for mineralization by von Kossa (central panel) and Alizarin red (right panel). D, cells were cultured for 7 days in the osteoblast differentiation medium, and ALP activity was measured. E, the expressions of BSP and OCN were determined by real-time PCR. All the data in the real-time PCR experiments are presented as means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provide the evidence that Jmjd3 is a novel factor responsible for osteoblast differentiation. The Jmjd3 expression was induced during osteoblast differentiation, which was mediated by BMP-2 signaling. Moreover, silencing of Jmjd3 decreased ALP activity and the expression levels of bone-related genes through the modification of H3K27me3 on the promoter regions of Runx2 and osterix, resulting in the suppression of osteoblast differentiation and mineralization.

First, we showed that the Jmjd3 expression increased in the osteoblasts cultured in the osteoblast differentiation medium containing ascorbic acid and β-glycerophosphate. Treatment of ascorbic acid and β-glycerophosphate has been reported to induce BMP-2 expression in osteoblasts, which is required for osteoblast-specific gene expression (26–28). We examined whether the induced BMP-2 would mediate the Jmjd3 expression in the cultured cells. Noggin is an extracellular antagonist of BMP-2, which binds to BMP-2 and prevents its downstream signaling pathway. Noggin inhibited the Jmjd3 expression in the cells cultured in the osteoblast differentiation medium. In contrast, U0126 (MAPK inhibitor) and LY2940002 (PI3K inhibitor) did not inhibit the Jmjd3 expression, although MAPK and PI3K pathways are involved in osteoblast differentiation (29, 30). Furthermore, silencing of Smad1/5 decreased Jmjd3 expression, which suggests that BMP-2 signaling is involved in the induction of the Jmjd3 expression during osteoblast differentiation.

Second, we demonstrated that the induced Jmjd3 was mainly localized in the nucleus in the differentiating osteoblasts. In the untreated cells, the slight expression of Jmjd3 was observed in the cytoplasm. Expression of Jmjd3 in the nucleus increased during osteoblast differentiation, as determined by immunocytochemistry and Western blot analysis. It was reported that Jmjd3 is localized in the nucleus during embryo development and neural stem cell differentiation (31, 32). Induction of Jmjd3 expression in the nucleus suggests that Jmjd3 plays important roles in osteoblast differentiation as a histone demethylase.

Third, we examined the roles of Jmjd3 in osteoblast differentiation. With this objective, we performed the gene-silencing experiments by siRNA and shRNA. Transient knockdown of Jmjd3 decreased the expressions of Runx2 and osterix, which are the markers at the earlier stage of osteoblast differentiation. To further investigate the role of Jmjd3 in the late stage of osteoblast differentiation and mineralization, stable Jmjd3 knockdown cells were established. Knockdown of Jmjd3 decreased the level of H3K27me3 but did not affect H3K4me3, H3K9me3, and H3K36me3, which is consistent with the other studies about the role of Jmjd3 as demethylase specific for H3K27me3 (33–35). In this study, we demonstrated that ALP activity and mineralization were dramatically reduced in the shJmjd3 cells, indicating that reduction of Jmjd3 expression strongly suppressed osteoblast differentiation. The impaired osteoblast differentiation was accompanied with significant decreases in the expressions of BSP, OCN, and OPN in the shJmjd3 cells. To further clarify the role of Jmdj3 in bone formation in vivo, we subcutaneously injected the siJmjd3 in the mouse calvarial region. Administration of siJmjd3 decreased bone mineral density, bone mineralization rate, bone thickness, and mineralized bone matrix. Taken together, this information indicates that silencing of Jmjd3 impaired osteoblast differentiation and bone formation.

Modifications of histones have several important consequences. The most profound effect of methylation of histones is their ability to cause compaction of the chromatin or facilitate access to the DNA, negatively or positively regulating the transcriptional activity of the target genes. Our study also uncovered a distinct promoter behavior in response to H3K27me3 occupation. Knockdown of Jmjd3 decreased the activity of Runx2 and osterix promoters, as well as the Runx2 3×binding site, and increased the level of H3K27me3 on the promoter regions of Runx2 and osterix. On the promoter regions of Runx2 and osterix, there are several important binding sites for transcription factors such as Msx-2 and distal-less homeobox 5 (Dlx-5). Our results suggest that knockdown of Jmjd3 failed to remove the repressive transcription mark H3K27me3 on the promoter regions of Runx2 and osterix, which further prevented Msx-2 and Dlx-5 from approaching to these binding sites, resulting in the down-regulation of Runx2 and osterix.

To further confirm the roles of Runx2 and osterix in the Jmjd3 knockdown cells, we transfected Runx2 and osterix expression vectors in the shJmjd3 cells. Introduction of the exogenous Runx2 and osterix rescued osteoblast differentiation and the expressions of BSP and OCN in the shJmjd3 cells. These results indicate that Jmjd3 regulates the expressions of BSP and OCN during osteoblast differentiation via transcription factors, Runx2 and osterix.

Recently, it was reported that histone demethylases such as NO66 (36) and retinoblastoma-binding protein 2 (RBP2) (37) are involved in osteoblast differentiation. NO66, a histone demethylase of H3K4me and H3K36me, directly interacts with osterix, which is required for the inhibition of osterix transcriptional activity. RBP2 is also a histone demethylase of H3K4me and associates with Runx2, which in turn controls osteoblast differentiation. The targeted sites (H3K4 and H3K36) of NO66 and RBP2 are normally associated with the active gene transcription when the sites are methylated. Knockdown of NO66 and RBP2 has been reported to lead to accelerated osteoblast differentiation. On the other hand, the target site of Jmjd3 is H3K27me3, which is generally relevant in the transcriptional repression. It is reasonable that knockdown of Jmjd3 resulted in impaired osteoblast differentiation. The expression of ubiquitously transcribed tetratricopeptide repeat X chromosome (Utx), another demethylase of H3K27me3, also increased during osteoblast differentiation, and knockdown of Utx gene decreased the expression of bone-related gene including Runx2 and osterix.3 These results support the view that H3K27me3 is an important epigenetic regulator of osteoblast differentiation.

In summary, we demonstrated that Jmjd3 expression and nuclear localization were stimulated during osteoblast differentiation, which was mediated by BMP-2 signaling pathway. Silencing of Jmjd3 expression suppressed osteoblast differentiation through increasing occupation of H3K27me3 to the promoter region of Runx2 and osterix. Introduction of exogenous Runx2 and osterix partly recovered the expressions of BSP and OCN and sequentially osteoblast differentiation in the Jmjd3 knockdown cells. Our present study provides new findings that Jmjd3 plays important roles in osteoblast differentiation and regulates the expressions of BSP and OCN via transcription factors Runx2 and osterix.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. K. Ochiai for constructing three-dimensional images of mouse calvaria and Dr. J. Teramachi for valuable discussions. We give our gratitude to Drs. T. Tohmonda and K. Horiuchi for providing us with the osterix promoter reporter vectors. We also thank E. Sasaki for skillful technical assistance.

This study was supported by Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research 21592330, 23592703, and 25462859 from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan.

D. Yang, H. Okamura, Y. Nakashima, and T. Haneji, unpublished data.

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic protein

- ALP

- alkaline phosphatase

- μCT

- microcomputed tomography.

REFERENCES

- 1. Katagiri T., Yamaguchi A., Komaki M., Abe E., Takahashi N., Ikeda T., Rosen V., Wozney J. M., Fujisawa-Sehara A., Suda T. (1994) Bone morphogenetic protein-2 converts the differentiation pathway of C2C12 myoblasts into the osteoblast lineage. J. Cell Biol. 127, 1755–1766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen D., Harris M. A., Rossini G., Dunstan C. R., Dallas S. L., Feng J. Q., Mundy G. R., Harris S. E. (1997) Bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) enhances BMP-3, BMP-4, and bone cell differentiation marker gene expression during the induction of mineralized bone matrix formation in cultures of fetal rat calvarial osteoblasts. Calcif. Tissue Int. 60, 283–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wozney J. M., Rosen V. (1998) Bone morphogenetic protein and bone morphogenetic protein gene family in bone formation and repair. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 26–37 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hanai J., Chen L. F., Kanno T., Ohtani-Fujita N., Kim W. Y., Guo W. H., Imamura T., Ishidou Y., Fukuchi M., Shi M. J., Stavnezer J., Kawabata M., Miyazono K., Ito Y. (1999) Interaction and functional cooperation of PEBP2/CBF with Smads: synergistic induction of the immunoglobulin germline Cα promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 31577–31582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ducy P., Zhang R., Geoffroy V., Ridall A. L., Karsenty G. (1997) Osf2/Cbfa1: a transcriptional activator of osteoblast differentiation. Cell 89, 747–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nakashima K., Zhou X., Kunkel G., Zhang Z., Deng J. M., Behringer R. R., de Crombrugghe B. (2002) The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell 108, 17–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hill T. P., Später D., Taketo M. M., Birchmeier W., Hartmann C. (2005) Canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling prevents osteoblasts from differentiating into chondrocytes. Dev. Cell 8, 727–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Komori T. (2006) Regulation of osteoblast differentiation by transcription factors. J. Cell Biochem. 99, 1233–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Komori T. (2008) Regulation of bone development and maintenance by Runx2. Front. Biosci. 13, 898–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Okamura H., Yoshida K., Yang D., Haneji T. (2013) Protein phosphatase 2A Cα regulates osteoblast differentiation and the expressions of bone sialoprotein and osteocalcin via osterix transcription factor. J. Cell Physiol. 228, 1031–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Okamura H., Yoshida K., Ochiai K., Haneji T. (2011) Reduction of protein phosphatase 2A Cα enhances bone formation and osteoblast differentiation through the expression of bone-specific transcription factor Osterix. Bone 49, 368–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Okamura H., Yang D., Yoshida K., Haneji T. (2013) Protein phosphatase 2A Cα is involved in osteoclastogenesis by regulating RANKL and OPG expression in osteoblasts. FEBS Lett. 587, 48–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Surani M. A., Hayashi K., Hajkova P. (2007) Genetic and epigenetic regulators of pluripotency. Cell 128, 747–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen S., Ma J., Wu F., Xiong L. J., Ma H., Xu W., Lv R., Li X., Villen J., Gygi S. P., Liu X. S., Shi Y. (2012) The histone H3 Lys 27 demethylase JMJD3 regulates gene expression by impacting transcriptional elongation. Genes Dev. 26, 1364–1375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen S., Shi Y. (2013) A new horizon for epigenetic medicine? Cell Res. 23, 326–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yu H., Zhu S., Zhou B., Xue H., Han J. D. (2008) Inferring causal relationships among different histone modifications and gene expression. Genome Res. 18, 1314–1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cui K., Zang C., Roh T. Y., Schones D. E., Childs R. W., Peng W., Zhao K. (2009) Chromatin signatures in multipotent human hematopoietic stem cells indicate the fate of bivalent genes during differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 4, 80–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rivenbark A. G., Strahl B. D. (2007) Molecular biology. Unlocking cell fate. Science 318, 403–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pedersen M. T., Helin K. (2010) Histone demethylases in development and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 20, 662–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. De Santa F., Narang V., Yap Z. H., Tusi B. K., Burgold T., Austenaa L., Bucci G., Caganova M., Notarbartolo S., Casola S., Testa G., Sung W. K., Wei C. L., Natoli G. (2009) Jmjd3 contributes to the control of gene expression in LPS-activated macrophages. EMBO J. 28, 3341–3352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Estarás C., Akizu N., García A., Beltrán S., de la Cruz X., Martínez-Balbás M. A. (2012) Genome-wide analysis reveals that Smad3 and JMJD3 HDM co-activate the neural developmental program. Development 139, 2681–2691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sen G. L., Webster D. E., Barragan D. I., Chang H. Y., Khavari P. A. (2008) Control of differentiation in a self-renewing mammalian tissue by the histone demethylase JMJD3. Genes Dev. 22, 1865–1870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yasui T., Hirose J., Tsutsumi S., Nakamura K., Aburatani H., Tanaka S. (2011) Epigenetic regulation of osteoclast differentiation: possible involvement of Jmjd3 in the histone demethylation of Nfatc1. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26, 2665–2671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fei T., Xia K., Li Z., Zhou B., Zhu S., Chen H., Zhang J., Chen Z., Xiao H., Han J. D., Chen Y. G. (2010) Genome-wide mapping of SMAD target genes reveals the role of BMP signaling in embryonic stem cell fate determination. Genome Res. 20, 36–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Amorim B. R., Okamura H., Yoshida K., Qiu L., Morimoto H., Haneji T. (2007) The transcriptional factor Osterix directly interacts with RNA helicase A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 355, 347–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ghosh-Choudhury N., Harris M. A., Feng J. Q., Mundy G. R., Harris S. E. (1994) Expression of the BMP 2 gene during bone cell differentiation. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 4, 345–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harris S. E., Bonewald L. F., Harris M. A., Sabatini M., Dallas S., Feng J. Q., Ghosh-Choudhury N., Wozney J., Mundy G. R. (1994) Effects of transforming growth factor β on bone nodule formation and expression of bone morphogenetic protein 2, osteocalcin, osteopontin, alkaline phosphatase, and type I collagen mRNA in long-term cultures of fetal rat calvarial osteoblasts. J. Bone Miner. Res. 9, 855–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xiao G., Gopalakrishnan R., Jiang D., Reith E., Benson M. D., Franceschi R. T. (2002) Bone morphogenetic proteins, extracellular matrix, and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways are required for osteoblast-specific gene expression and differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 17, 101–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee S. U., Shin H. K., Min Y. K., Kim S. H. (2008) Emodin accelerates osteoblast differentiation through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation and bone morphogenetic protein-2 gene expression. Int. Immunopharmacol. 8, 741–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee S. U., Kang N. S., Min Y. K., Kim S. H. (2010) Camphoric acid stimulates osteoblast differentiation and induces glutamate receptor expression. Amino Acids 38, 85–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Canovas S., Cibelli J. B., Ross P. J. (2012) Jumonji domain-containing protein 3 regulates histone 3 lysine 27 methylation during bovine preimplantation development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 2400–2405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fonseca M. B., Nunes A. F., Morgado A. L., Solá S., Rodrigues C. M. (2012) TAp63γ demethylation regulates protein stability and cellular distribution during neural stem cell differentiation. PLoS One 7, e52417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lan F., Bayliss P. E., Rinn J. L., Whetstine J. R., Wang J. K., Chen S., Iwase S., Alpatov R., Issaeva I., Canaani E., Roberts T. M., Chang H. Y., Shi Y. (2007) A histone H3 lysine 27 demethylase regulates animal posterior development. Nature 449, 689–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xiang Y., Zhu Z., Han G., Lin H., Xu L., Chen C. D. (2007) JMJD3 is a histone H3K27 demethylase. Cell Res. 17, 850–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Solá S., Xavier J. M., Santos D. M., Aranha M. M., Morgado A. L., Jepsen K., Rodrigues C. M. (2011) p53 interaction with JMJD3 results in its nuclear distribution during mouse neural stem cell differentiation. PLoS One 6, e18421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sinha K. M., Yasuda H., Coombes M. M., Dent S. Y., de Crombrugghe B. (2010) Regulation of the osteoblast-specific transcription factor Osterix by NO66, a Jumonji family histone demethylase. EMBO J. 29, 68–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ge W., Shi L., Zhou Y., Liu Y., Ma G. E., Jiang Y., Xu Y., Zhang X., Feng H. (2011) Inhibition of osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stromal cells by retinoblastoma binding protein 2 repression of RUNX2-activated transcription. Stem Cells 29, 1112–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]