Background: Mouse dendritic cell inhibitory receptor 2 (DCIR2) specifically binds to bisecting GlcNAc-containing N-glycans.

Results: The crystal structure of DCIR2 carbohydrate recognition domain in complex with bisected glycan was elucidated.

Conclusion: The lectin asymmetrically interacts with the α1-3 arm (GlcNAcβ1–2Man) of the biantennary oligosaccharide including bisecting GlcNAc.

Significance: Mouse DCIR2 is the first bisecting GlcNAc-specific lectin to be structurally characterized.

Keywords: Carbohydrate, Crystal Structure, Dendritic Cells, Lectin, Receptors, C-type Lectin, DCIR2, Bisecting N-Acetylglucosamine, Glycan

Abstract

Dendritic cell inhibitory receptor 2 (DCIR2) is a C-type lectin expressed on classical dendritic cells. We recently identified the unique ligand specificity of mouse DCIR2 (mDCIR2) toward biantennary complex-type glycans containing bisecting N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc). Here, we report the crystal structures of the mDCIR2 carbohydrate recognition domain in unliganded form as well as in complex with an agalactosylated complex-type N-glycan unit carrying a bisecting GlcNAc residue. Bisecting GlcNAc and the α1-3 branch of the biantennary oligosaccharide asymmetrically interact with canonical and non-canonical mDCIR2 residues. Ligand-protein interactions occur directly through mDCIR2-characteristic amino acid residues as well as via a calcium ion and water molecule. Our structural and biochemical data elucidate for the first time the unique binding mode of mDCIR2 for bisecting GlcNAc-containing glycans, a mode that contrasts sharply with that of other immune C-type lectin receptors such as DC-SIGN.

Introduction

The innate immune system uses a variety of pattern recognition receptors on the cell surface to recognize molecular structures shared among pathogens. C-type lectin receptors on dendritic cells are carbohydrate binding receptors that interact with pathogens primarily through the recognition of foreign or endogenous carbohydrate structures (1–3). These C-type lectin receptors recognize mannose, fucose, and glucan carbohydrate structures that comprise the cell walls of pathogens (4). The recognition of pathogens by C-type lectin receptors is essential for immune activation and antigen presentation.

Proteins containing the C-type lectin domain constitute a superfamily of proteins, and more than 1000 of such proteins are classified into 17 groups (group I-XVII) on the basis of domain organization and phylogeny (4). Ca2+-dependent carbohydrate binding is the most common function of the C-type lectin domain. Group II C-type lectin receptors are type II transmembrane proteins consisting of a short N-terminal cytoplasmic tail, a transmembrane helix, an extracellular stalk region, and a single C-type lectin domain. This group consists of asialoglycoprotein receptor, dendritic cell (DC)4-specific ICAM3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN), Langerin, scavenger receptor, and members of DC-associated C-type lectin-1 (Dectin-1) and the DC inhibitory receptor (DCIR) family. The DCIR family includes DCIR, the DC activating receptor (DCAR), Dectin-2, and blood DC antigen-2 (BDCA-2) and is encoded primarily within a single gene cluster, i.e. the natural killer cell gene complex on chromosome 12 in humans and chromosome 6 in mice (5). These C-type lectin domains bind both a calcium ion and carbohydrate ligands and hence function as lectin receptors on myeloid cells.

Human DCIR, also known as CLEC4A or CLECSF6, is expressed on various antigen-presenting cells such as B cells, monocytes, and myeloid DCs (6) and acts as an inhibitory receptor via a short cytoplasmic tail with an intracellular immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (5). Triggering of DCIR on human DCs results in antigen presentation and inhibition of type I interferon-α production (7). The DCIR on monocyte-derived DCs is internalized efficiently after triggering with a DCIR-specific monoclonal antibody (8). Four homologs of human DCIR are present in the mouse genome (DCIR1–4), but only DCIR1 and DCIR2 possess the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif sequence (9). Mouse DCIR1 is expressed in B cells, monocytes, macrophages, and DCs (6). Mouse DCIR2 (mDCIR2), also known as Clec4a4, was utilized as a benchmark for the selection of mouse DCs (10, 11). The ligand binding characteristics of the DCIR family have been extensively investigated. Human DCIR binds to mannose/fucose-conjugated bovine serum albumin (BSA) (12) and has been reported to act as the attachment factor for HIV-1 in DCs (13). Recently we found that mDCIR2 specifically binds to complex-type N-glycan containing bisecting N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc).5 Mouse DCIR2 is the first example of an animal lectin that specifically binds bisected N-glycan.

Bisecting GlcNAc is a β1–4-linked GlcNAc residue attached to a β-mannose of the N-glycan core, and the reaction is catalyzed by N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase-III (GnT-III/Mgat-III) (14). Many reports have suggested that sugar chains containing bisecting GlcNAc are involved in a variety of biological functions such as cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, cell growth control, and tumor progression (15–17). A mutated mouse with truncated inactive mouse GnT-III showed neurological dysfunction (18). Overexpression of GnT-III resulted in the suppression of H2O2-induced apoptosis in HeLaS3 cells by the inhibition of the PKCδ-JNK1 pathway (19) and GnT-III-potentiated β1 integrin-mediated neuritogenesis in Neuro2a cells (20). The addition of bisecting GlcNAc to the N-glycan of integrin α5β1 inhibited cell spreading and migration by blocking fibronectin binding ability (21). Although bisected glycans appear to have biological importance, lectin receptors that specifically recognize this glycan have not been well understood.

In this report we present crystallographic analyses of the mDCIR2 carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) in the absence and presence of complex-type glycan containing bisecting GlcNAc. We couple the structures with a site-directed mutagenesis study and present a unique carbohydrate binding mode.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

The hexasaccharide GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-3[GlcNAcβ1-4][GlcNAcβ1-2Manα1-6]Manα1-O-methyl was chemically synthesized, and the procedure will be reported elsewhere.6 Pyridylaminated biantennary glycans for NMR titration study were prepared from sheep immunoglobulin G (IgG). Briefly, the N-glycans attached to IgG were liberated by hydrazinolysis. After acetylation, the released oligosaccharides were pyridylaminated as described previously (22, 23). The pyridylamino derivatives of the oligosaccharides were separated on an ODS column, and the two target oligosaccharides (Fig. 6A) isolated. Each chemical structure was identified by 1H NMR based on previous reports (24, 25).

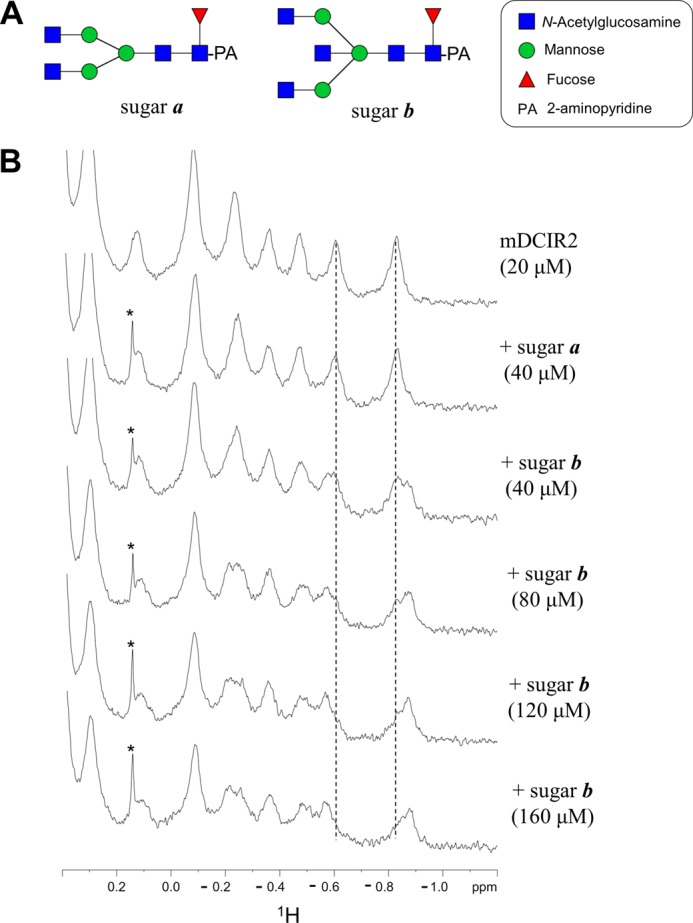

FIGURE 6.

Solution NMR analysis of the interaction between mDCIR2 CRD and glycans. A, the pyridylaminated oligosaccharides (sugars a and b) used in the titration study. B, a part of 1H NMR spectra of 20 μm mDCIR2 CRD in the absence of glycan (top), in the presence of 40 μm sugar a (second), and 40–120 μm sugar b (third to the last). The signal from a low molecular weight contaminant is indicated with an asterisk.

Protein Expression and Purification

A DNA fragment encoding mDCIR2 CRD (Cys-107–Lys-233) was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers containing BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites. The PCR product was cloned into the BamHI/EcoRI site of a pCold-TEV vector that had been modified to include a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage sequence between the hexahistidine tag and mDCIR2. The expression plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli strain Rosetta 2 (DE3) (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). The transformed cells were grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 37 °C, and the expression was induced with 0.5 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) for 16 h at 15 °C. The harvested cells were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 8 mm Na2HPO4, 1 mm KH2PO4, 137 mm NaCl, and 3 mm KCl (pH 7.4)) containing Bugbuster (Novagen) and then sonicated. After centrifugation, the inclusion bodies were washed 3 times with PBS. The resulting protein was solubilized in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mm NaCl, and 8 m urea at a protein concentration of 5 mg/ml. Solubilized protein was diluted into 2 liters of buffer containing 200 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.4 m l-arginine, 5 mm reduced glutathione, and 0.5 mm oxidized glutathione. The mixture was equilibrated at 4 °C for 16 h with slow stirring and then concentrated to a volume of 200 ml by the QuixStand Benchtop system (GE Healthcare). The concentrated protein solution was extensively dialyzed against 2 liters of PBS containing 10% (v/v) glycerol at 4 °C. The dialyzed protein was applied onto a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with PBS containing 500 mm imidazole. The eluted protein was treated with tobacco etch virus protease for 16 h at 4 °C to remove the hexahistidine tag. The digest was applied onto a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 prep grade column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mm NaCl, and 1 mm CaCl2. The protein fraction was concentrated to 3∼5 mg/ml using an Amicon Ultra (molecular weight cutoff, 10,000) and then subjected to crystallization screening.

Crystallization and Structure Determination

All the crystals were obtained by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method using 0.8-μl drops containing a 50:50 (v/v) mix of protein and reservoir solution at 20 °C. The crystallization conditions were determined by screening using the Crystal Screen and Index (Hampton Research, Aliso Viejo, CA). Crystals of the ligand-free form were grown in a reservoir containing 2.0 m ammonium sulfate. Crystals in complex with hexasaccharide ligand were obtained in 0.1 m Bis-Tris (pH 6.5), 0.2 m ammonium sulfate, and 25% (w/v) PEG 3350.

Before x-ray diffraction experiments, crystals were soaked in the reservoir solution containing 20% (v/v) ethylene glycol and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data sets for the crystals were collected at the synchrotron radiation source at AR-NW12A and BL17A in the Photon Factory (Tsukuba, Japan). All data sets were processed and scaled using the HKL2000 program suite (26). Initial phase determination was performed by the molecular replacement method using the program MOLREP (27), with the structure of human DC-SIGN (PDB code 2XR6) as template. Further model building was performed manually using the program COOT (28). Refinement was conducted using REFMAC5 (29). The stereochemical quality of the final models was assessed by MolProbity (30). Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1. All figures were prepared with PyMOL (DeLano Scientific). Structural superposition was performed with SUPERPOSE (31). Dihedral angles of the glycosidic linkages were calculated with CARP (32).

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Data sets | Ligand-free | Ligand-bound | Ligand-bound (low energy) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection statistics | |||

| Space group | P6522 | P3221 | P3221 |

| Unit cell | a = b = 49.4 Å, | a = b = 76.3 Å, | a = b = 76.2 Å, |

| c = 250.5 Å | c = 50.6 Å | c = 50.5 Å | |

| Beam line | BL-17A, PF | AR-NW12A, PF | BL-17A, PF |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9800 | 1.0000 | 1.7000 |

| Resolution (Å)a | 100-2.15 | 100-1.50 | 100-1.85 |

| (2.19-2.15) | (1.53-1.50) | (1.88-1.85) | |

| Total reflections | 212,564 | 290,505 | 285,954 |

| Unique reflections | 10,806 | 27,520 | 14,745 |

| Completeness (%)a | 99.9 (100) | 99.4 (100) | 99.9 (100) |

| Rsym (%)a | 7.2 (48.4) | 4.7 (49.6) | 6.8 (41.3) |

| 〈I〉/〈σI〉a | 65.2 (10.0) | 60.2 (7.0) | 88.1 (9.3) |

| Refinement statistics | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 42.80-2.15 | 66.11-1.50 | |

| Reflections | 10,218 | 26,110 | |

| Rwork (%) | 23.7 | 21.1 | |

| Rfree (%) | 27.2 | 22.4 | |

| r.m.s.d. from ideal values | |||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.010 | 0.009 | |

| Bond angle (°) | 1.319 | 1.274 | |

| Average B-factors (Å2) | 34.5 | 19.1 | |

| Ramachandran plot | |||

| Favored (%) | 96.0 | 98.4 | |

| Allowed (%) | 4.0 | 1.6 | |

a Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shells.

NMR Titration Analysis

mDCIR2 CRD was dissolved at a concentration of 20 μm in a volume of 0.2 ml with 5 mm Tris·HCl (pH 8.0) containing 25 mm NaCl and 1 mm CaCl2. All NMR experiments were carried out on a DRX-500 spectrometer (BrukerBiospin) equipped with a triple resonance cryogenic probe with the temperature set to 283 K. 1H chemical shift values are given in ppm calibrated with external reference DSS (4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid) at 0 ppm. Data processing was performed by XWIN-NMR Version 3.5 (BrukerBiospin), and the spectra were displayed using XWIN-PLOT Version 3.5 (BrukerBiospin).

Binding Assay Using Mouse DCIR2 Reporter Cells

To express the extracellular part of mDCIR2 on the surface of the reporter cells, the pMXs-IRES-GFP vector, containing cDNAs encoding the cytoplasmic region of mouse CD3ζ as well as the Ly49A transmembrane domain and the extracellular domain of mDCIR2 (residues 70–236), was constructed and used for the transduction of BWZ.36 cells to establish the mDCIR2 reporter cell line BWZ.mDCIR2. The empty vector (without the DCIR2 extracellular domain) was used to establish the control cell line BWZ.Myc. The lectin-resistant CHO cell line, Lec8 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was transfected with mouse GlcNAc-transferase III cDNA (mgatIII), and the stably expressing cell clone, Lec8mgatIII, was used. BWZ.mDCIR2 reporter cells were cocultured with Lec8 or Lec8mgatIII cells in ELISA plates (Greiner Bio-One, Frickenhausen, Germany) for 16 h, and then the β-galactosidase activity was determined by colorimetric assay using chlorophenol red-β-d-galactopyranoside (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) as the substrate. mDCIR2 clones containing the individual mutations N198A, Q199A, W201A, D223A, or H225A were also generated by PCR-based mutagenesis using a QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

Erythroagglutinating Phaseolus vulgaris Agglutinin (E-PHA) Binding Assay Using Flow Cytometry

The presence of complex-type N-glycans with bisecting GlcNAc on the cell surface was confirmed by E-PHA binding using flow cytometry. Lec8 or Lec8mgatIII cells (2 × 105 cells) were incubated with biotinylated E-PHA (1 μg/ml) in 40 μl of 20 mm HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.4) and 150 mm NaCl (HEPES-buffered saline (HBS)) containing 1 mm CaCl2, 0.1% NaN3, and 0.1% BSA at 25 °C for 60 min. After washing with HBS, the cells were stained with 10 μg/ml phycoerythrin-conjugated streptavidin (Pharmingen) at 25 °C for 30 min in the dark. After washing 3 times with HBS, the cells were suspended in 300 μl of HBS containing 1 μg/ml propidium iodide. The cells were analyzed by a FACSCalibur system (BD Biosystems) and a FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

RESULTS

Overall Structure of mDCIR2 CRD

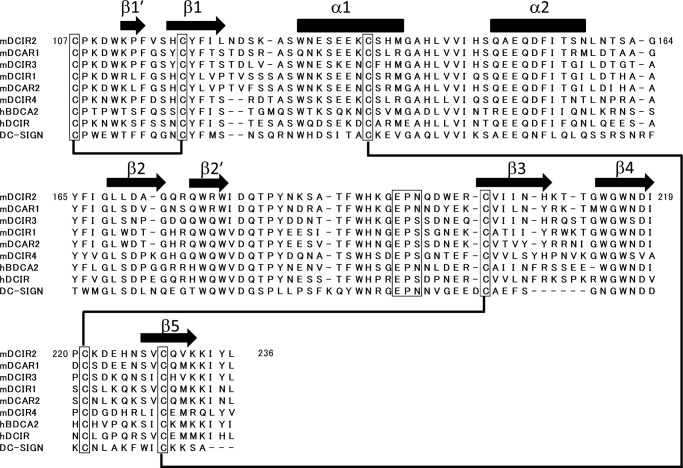

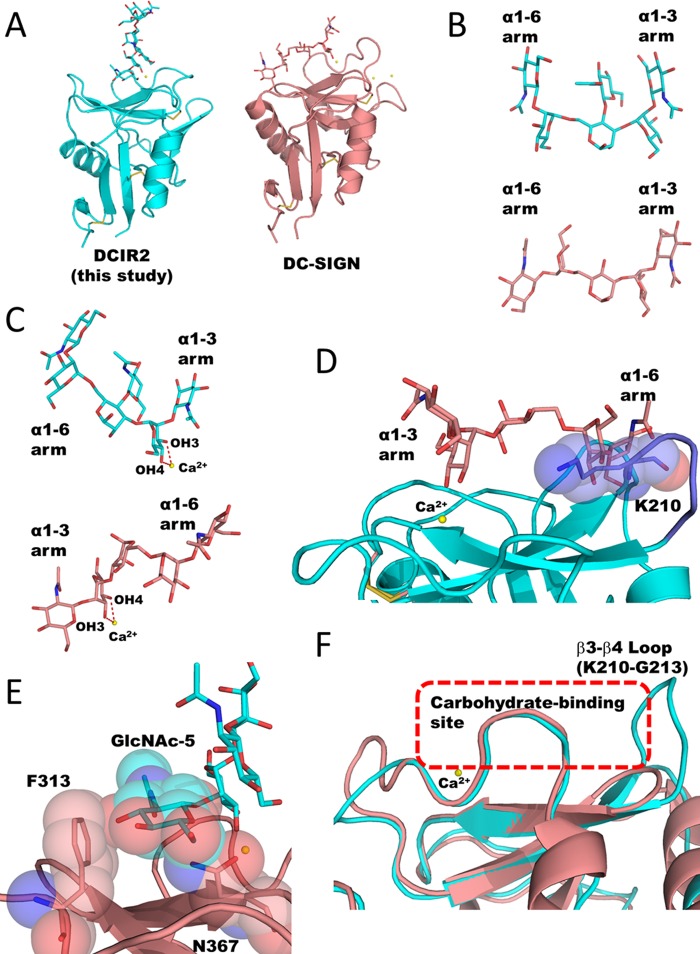

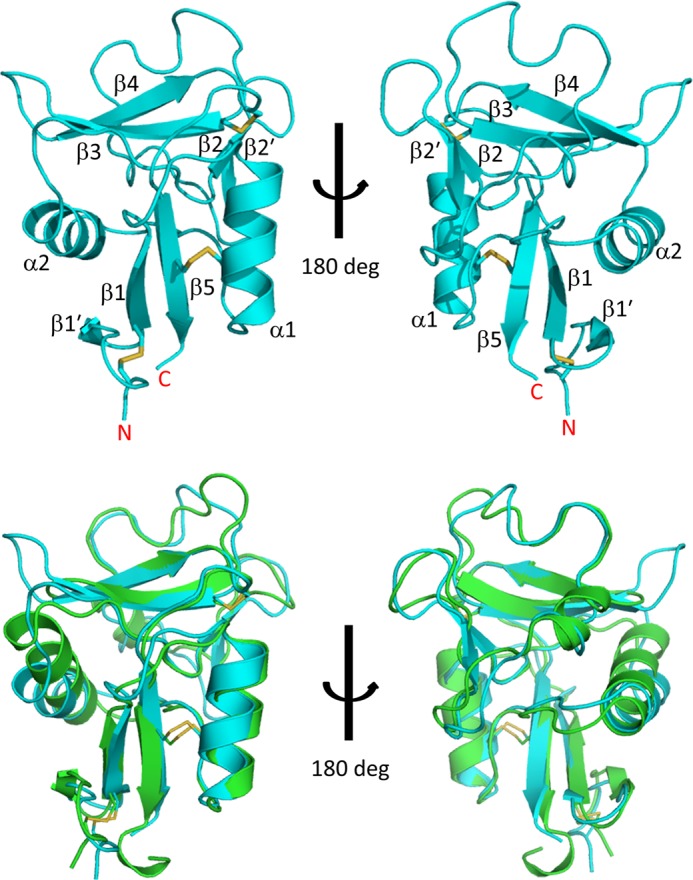

Our aim was to reveal how mDCIR2 specifically recognizes the glycans that have a bisecting GlcNAc residue. To investigate the binding mode of mDCIR2, we determined the crystal structures of the mDCIR2 CRD in the absence and presence of the carbohydrate ligand. The crystals of the ligand-free form of mDCIR2 CRD belong to space group P6522 and diffracted to 2.15 Å resolution. The initial phase of mDCIR2 CRD was determined by molecular replacement using the structure of DC-SIGN CRD as a search model, sharing 34% amino acid sequence identity with the mDCIR2 CRD (Fig. 1). The asymmetric unit contains one mDCIR2 CRD molecule. mDCIR2 CRD is composed of two α-helices (α1 and α2) and seven β-strands (β1, β1′, β2, β2′, β3, β4, and β5) with three disulfide bridges (Cys-107–Cys-118, Cys-136–Cys-229, and Cys-204–Cys-221) (Figs. 1 and 2, upper panel). There are two antiparallel β-sheets; one is formed by the β1′, β1, and β5 strands, and the other is formed by the β3 and β4 strands. The architecture of mDCIR2 CRD thus preserves key features of a typical long-form C-type lectin-like domain (33). A difference observed in the mDCIR2 CRD structure compared with other CRDs is that the β2 strand is short and, therefore, does not participate in the β-sheet composed of the β3 and β4 strands. Instead, an additional short β-hairpin loop is formed between Leu-169 (β2) and Trp-179 (β2′). There is no discernable electron density corresponding to a calcium ion in the ligand-free mDCIR2 molecule. The high concentration (2.0 m) of ammonium sulfate, used as precipitant, may have significantly lowered the free Ca2+ concentration. Structural superposition of mDCIR2 and DC-SIGN reveals that the loop connecting the β3 and β4 strands (His-209–Trp-214) of mDCIR2 is relatively long and kinked toward the carbohydrate binding site (Fig. 2, lower panel). The DALI server (34) revealed that mouse scavenger receptor C-type lectin (SRCL) CRD has the closest structural similarity to mDCIR2 CRD (PDB code 2OX9; Z score = 22.1, root mean square deviation = 1.0 Å for 116 Cα atoms) (35).

FIGURE 1.

Sequence alignment of the carbohydrate recognition domains of DCIR family members. Amino acid sequences of human (hDCIR) and mouse DCIR family proteins were aligned by ClustalW. The amino acid sequence information was obtained from Uniprot Knowledgebase.

FIGURE 2.

Crystal structure of mDCIR2 CRD in ligand-free form. Upper panel, overall structure of apo-mDCIR2 CRD is shown in a ribbon representation. The disulfide bridges are displayed as rods. The secondary structure element numbering is based on a previous report (4). Lower panel, superposition of mDCIR2 (cyan) and DC-SIGN (green).

Recognition of Bisecting GlcNAc

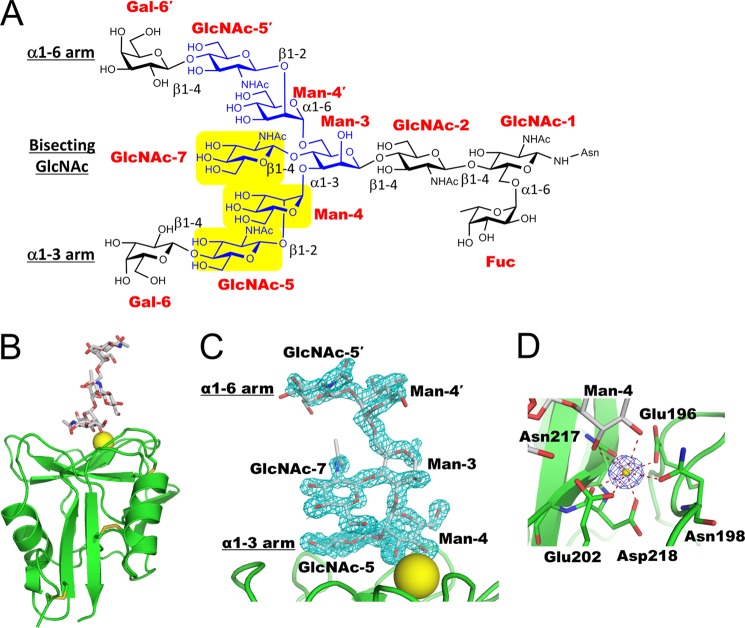

A representative chemical structure of a biantennary complex-type glycan containing bisecting GlcNAc and core-fucose is shown in Fig. 3A. To clarify the recognition mechanism of the bisecting GlcNAc-containing glycan, we co-crystallized mDCIR2 with a truncated hexasaccharide of biantennary complex-type glycan containing bisecting GlcNAc (Fig. 3B). Co-crystals of mDCIR2 CRD with the hexasaccharide diffracted to 1.5 Å resolution in the P3221 space group. The asymmetric unit contains one protein-carbohydrate complex. The electron density for the hexasaccharide, with all six carbohydrate residues, was readily identified (Fig. 3C). The dispersive difference Fourier map calculated from the data set at a wavelength of 1.7 Å revealed only one strong peak density (above 10 σ), corresponding to a calcium ion located in the canonical binding site (Fig. 3D). The calcium ion is octa-coordinated by the acidic oxygen atoms of Glu-196, Glu-202, and Asp-218, the oxygen atoms from amides Asn-198 and Asn-217, and the carbonyl oxygen atom of Asp-218 and OH3 and OH4 hydroxyl groups of α1-3-linked mannose (Man-4).

FIGURE 3.

Crystal structure of mDCIR2 CRD in complex with a bisected hexasaccharide. A, representative chemical structure of a biantennary complex-type N-glycan with bisecting GlcNAc and core-fucose residues. Bisecting GlcNAc-containing glycan used in the crystallization is shown in yellow. Carbohydrate residues that interact with mDCIR2 are highlighted with yellow. B, overall structure of mDCIR2 CRD in complex with the bisected glycan. DCIR2 CRD, calcium ion, and glycan are represented in ribbon, sphere, and rod models, respectively. C, close-up view of the calcium ion-binding site of mDCIR2. The carbohydrate and the amino acid residues that coordinate the calcium ion (yellow) are displayed in rod models. The coordination bonds are shown in red dotted lines. The anomalous difference Fourier map contoured at 10 σ is shown in blue mesh. D, the observed electron density of the ligand. The omit map of the ligand contoured at the 3 σ level in the carbohydrate binding site is shown in cyan mesh. The ligand is shown in the rod model.

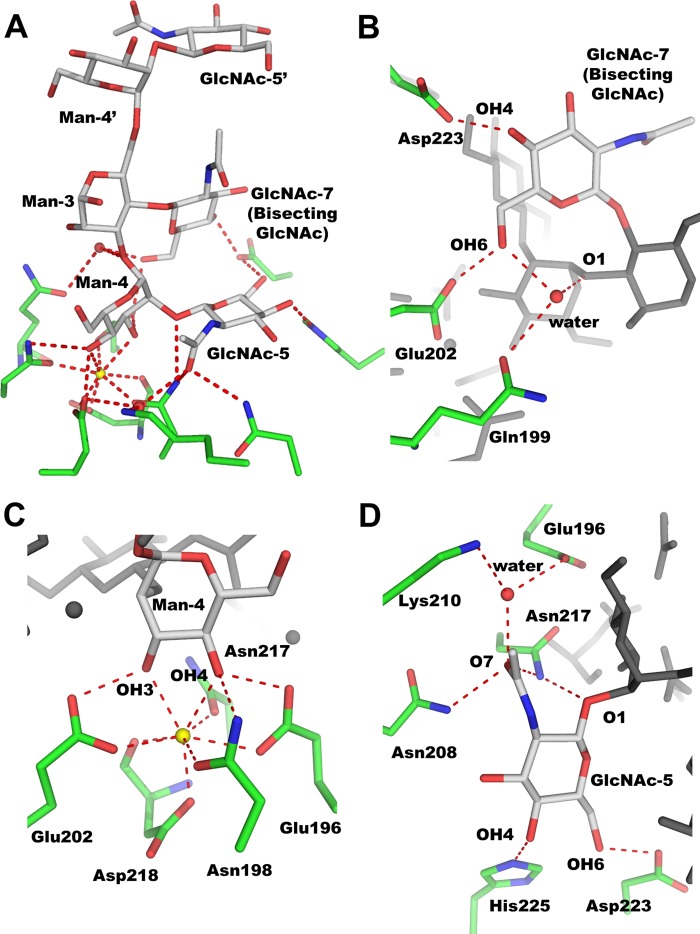

The hexasaccharide forms a “trident”-like structure, with mDCIR2 CRD interacting with three carbohydrate residues; that is, Man-4 and GlcNAc-5 in the α1-3 branch as well as bisecting GlcNAc (GlcNAc-7) (Fig. 4A). Carbohydrate recognition by mDCIR2 is mediated by several hydrogen bonds and coordination bonds. For the recognition of bisecting GlcNAc (GlcNAc-7), mDCIR2 CRD interacts with two hydroxyl groups, OH4 and OH6 (Fig. 4B). The OH4 hydroxyl group of GlcNAc-7 forms a hydrogen bond with the Oδ atom of Asp-223, and the OH6 hydroxyl group forms a hydrogen bond with the Oϵ atom of Glu-202. One water molecule bridges the Oϵ atom of Gln-199, OH6 of GlcNAc-7, and OH1 of Man-4. Thus, the recognition of bisecting GlcNAc is associated with the α1-3 branch. In this branch Man-4 is mainly stabilized by coordination bonds between the OH3/OH4 groups and a calcium ion (Fig. 4C). Moreover, the OH3 group of Man-4 binds to the side chain of Glu-202. The OH4 group of Man-4 hydrogen bonds with the Oϵ atom of Glu-196 and the Nδ atom of Asn-198. mDCIR2 CRD interacts with two hydroxyl groups (OH4 and OH6) and the acetyl oxygen atom (O7) of GlcNAc-5 in the α1-3 branch (Fig. 4D). The OH4 hydroxyl group of GlcNAc-5 interacts with the Nϵ atom of His-225. The OH6 hydroxyl group of GlcNAc-5 forms a hydrogen bond with the Oδ atom of Asp-223. The acetyl oxygen (O7) of GlcNAc-5 hydrogen bonds with the Nδ atoms of two asparagine residues (Asn-208 and Asn-217) and forms water-mediated contacts with the Oϵ atom of Glu-196 and the Nζ atom of Lys-210. In contrast to the extensive interaction of the α1-3 branch with mDCIR2, the α1-6 branch does not interact with mDCIR2 CRD. The α1-6 branch is located far from mDCIR2 CRD and is completely solvent-exposed.

FIGURE 4.

Specific recognition of bisected glycan by mDCIR2. A, close-up view of the ligand-binding site. B–D, close up view of GlcNAc-7 (B), Man-4 (C), and GlcNAc-5 (D). Hydrogen and coordination bonds are shown in red dotted lines. Calcium ion is shown in a sphere model. Carbohydrate and amino acid residues are depicted in rod models.

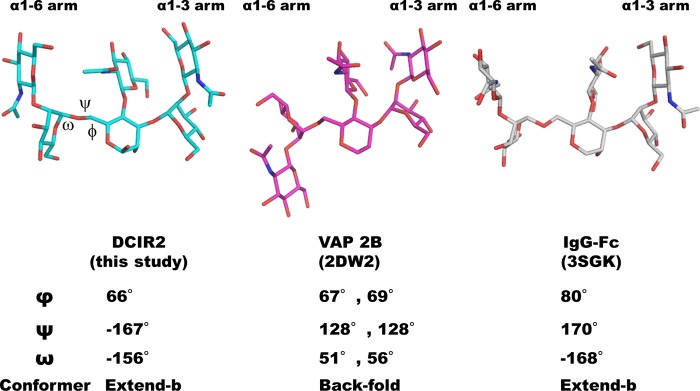

Conformation of the Glycan Containing Bisecting GlcNAc

Recent molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of biantennary N-glycans indicated that α1-6 branches adopt five distinct conformers (backfold, half backfold, tight backfold, extend-a, and extend-b), whereas the distances between the α1-3 branch and the core-mannose are nearly constant (36, 37). The conformation of the α1-6 linkage is defined by three dihedral angles, ψ (C1-O-C6′-C5′), φ (O5-C1-O-C6′), and ω (O-C6′-C5′-C4′). For glycans with bisecting GlcNAc, a “backfold” conformation might be the favored conformer in solution. The ψ, φ, and ω values of the backfold conformer are ∼90°, ∼70°, and 60°, respectively. However, in the bisected glycan complexed with mDCIR2, the dihedral angles of the α1-6 linkage ψ, φ, and ω are −167°, 66°, and −156°, respectively. The conformer is an “extend-b” conformation, which is a meta-stable glycan conformer with bisecting GlcNAc according to MD simulations. MD simulations also showed the presence of hydrogen bonds between the bisecting GlcNAc and several other carbohydrate residues in solution (37). However, in the crystal structure, no such hydrogen bond was observed. Interestingly, several protein atoms and water molecules serve to mediate the sugar-sugar interaction. For example, Asp-223 bridges OH6 of GlcNAc-5 and OH4 of GlcNAc-7 (Fig. 4, B and D). This hydrogen bond network may contribute to the structural stabilization of the ligand complex. Intriguingly, additional electron density was observed between GlcNAc-7 and the α1-6-branched GlcNAc-5′. This electron density was assigned to ethylene glycol, which was used as a cryoprotectant (data not shown). The α1-6 branch is completely exposed to solvent and essentially free from protein interactions. Despite this observation, the electron density of the branch was clearly observed.

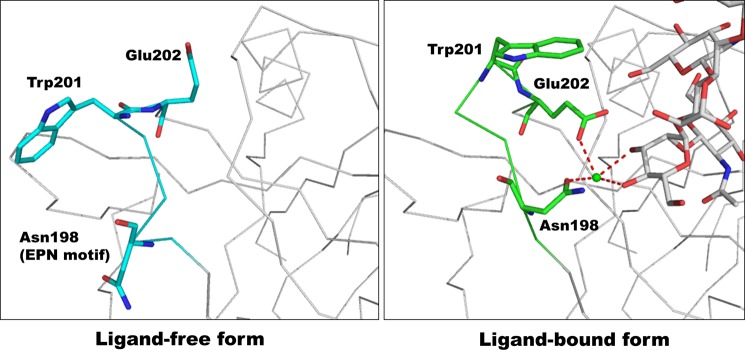

Ligand-induced Conformational Change of mDCIR2

Structural comparison of the ligand-free and ligand-bound mDCIR2 revealed that the protein structures were essentially identical, with a root mean square deviation of 0.59 Å for 127 Cα atoms. A critical difference was found in the loop region (Pro-197–Glu-202) near the primary calcium ion binding site (Fig. 5). The primary calcium ion binding site of the ligand-free form is fully opened, whereas the side chains of Asn-198 and Glu-202 contribute to the coordination of the calcium ion in the sugar-bound complex. Interestingly, ligand binding induces a flip of the Trp-201 side chain to cover the ligand binding site. The primary Ca2+-binding site in the ligand-free form is fully opened, which is quite different from the C-type lectin CD23 (38). The open form of mDCIR2 is distinct from apoCD23, where the Ca2+-binding site is occupied by an arginine residue from the neighboring loop (38).

FIGURE 5.

Structural comparison between the ligand-free and ligand-bound mDCIR2 CRD, focusing on the β2′-β3 loop region. The main chains of the ligand-free form (cyan, left panel) and ligand complex (green, right panel) are depicted in a wire model. Three amino acid residues (Asn-198, Trp-201, and Glu-202) are highlighted in rod models.

Solution NMR Analysis of mDCIR2 Interaction

To demonstrate a direct interaction between bisected glycan and mDCIR2 in solution, we performed titration experiments monitored by one-dimensional 1H NMR spectra (Fig. 6). Upon the addition of the bisected ligand, we observed spectral changes in the 1H NMR spectra in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6B). The observation indicates that the bisected glycan directly interacts with mDCIR2 in solution. The interaction is a slow exchange process in terms of the chemical shift, and the dissociation constant was estimated to be 3.0 × 10−5 m. In contrast, the non-bisected ligand did not show spectral changes (Fig. 6B), indicating that mDCIR2 binds bisected glycans selectively.

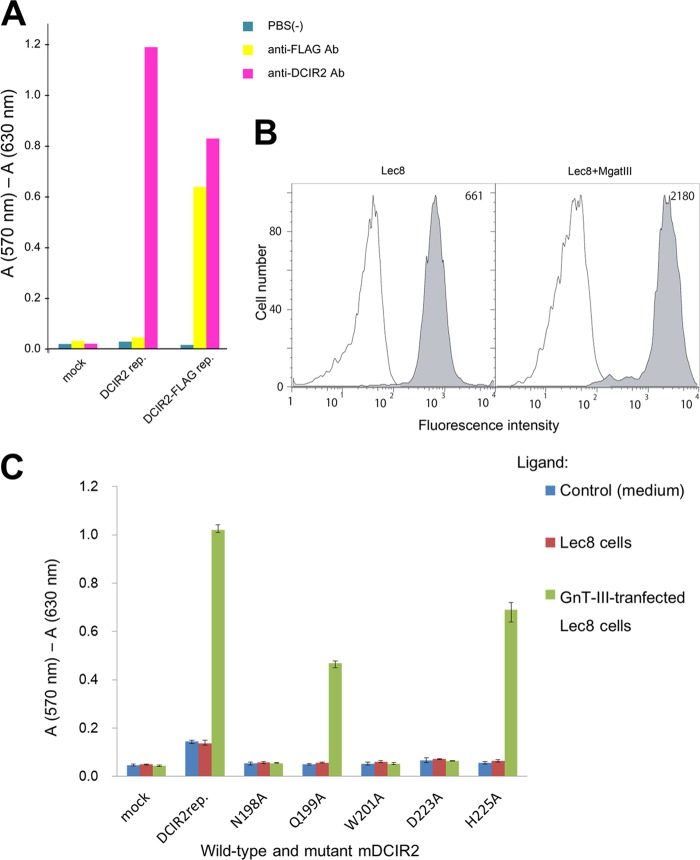

Reporter Assay Using Alanine-substituted mDCIR2 Mutants

To evaluate the contribution of each amino acid residue to ligand binding, we performed reporter-gene assays using wild-type mDCIR2 and its five alanine-substituted mutants. BWZ.mDCIR2 cells express a chimeric protein of the mDCIR2 extracellular domain and the CD3ζ cytoplasmic domain on the cell surface. Cross-linking of mDCIR2 chimeric protein on the cell surface by the ligands leads to β-galactosidase expression (39). Anti-mDCIR2 monoclonal antibody immobilized on the plastic well transduced the cross-linking signal into both the mDCIR2-expressing BWZ.mDCIR2 and the FLAG-tagged mDCIR2-expressing BWZ.mDCIR2-FLAG cells but not into the mock-transfected BWZ.36 cells (Fig. 7A). Anti-FLAG antibody immobilized on the well transduced the signal into the BWZ.mDCIR2-FLAG cell but not into the BWZ.mDCIR2 or the mock-transfected cell (Fig. 7A). These results indicate that cross-linking of mDCIR2 chimeric proteins on BWZ.36 cell surfaces via immobilized antibodies resulted in the expression of β-galactosidase in the cells.

FIGURE 7.

Binding assays using wild-type and mutated mDCIR2 reporter cells. A, the mouse DCIR2-expressing BWZ.36 reporter cell, BWZ.mDCIR2 (DCIR2 rep.), cells expressing FLAG-tagged mouse DCIR2 (DCIR2-FLAG rep.), or mock transfected cells (mock) were cultured in anti-mDCIR2 antibody (pink)- or anti-FLAG antibody (Ab)-immobilized wells (yellow). The cells cultured in uncoated wells were used as a control (blue). The induced expression of β-galactosidase in the reporter cells was measured by a colorimetric assay. B, expression of bisecting GlcNAc-containing glycans on GnT-III-overexpressing cells. Binding of biotinylated E-PHA to Lec8 or GnT-III-overexpressing Lec8mgatIII was measured by flow cytometry. Lec8 or Lec8mgatIII cells were incubated with 1 μg/ml biotinylated E-PHA followed by staining with phycoerythrin-conjugated streptavidin. After three washes with HBS, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (filled histogram). Lines indicate staining with phycoerythrin-conjugated streptavidin alone. The numbers in each panel indicate the mean fluorescence intensity of E-PHA staining. C, the mouse DCIR2-expressing reporter cell, BWZ.mDCIR2, or cells expressing mutated mDCIR2 variants (N198A, Q199A, W201A, D223A, and H225A) instead of the wild type, were cultured in the absence (medium, blue) or the presence of Lec8 cells (red) or GnT-III-transfected Lec8 cells (green). BWZ.36 cells cultured in ELISA plate were used as a control (mock). The induced expression of β-galactosidase in the reporter cells was measured by a colorimetric assay. The results shown represent the means of triplicate experiments, and the error bars indicate the S.D.

We then investigated the interaction between mDCIR2 or its mutants, which are expressed on BWZ.mDCIR2 cells, and bisecting GlcNAc-containing glycans expressed on Lec8mgatIII cells. Lec8mgatIII cells are Lec8 cells stably transfected with the mouse GnT-III cDNA (mgatIII). GnT-III expression increased the expression of bisecting GlcNAc-containing glycans on the cell surface, which was confirmed by an ∼3-fold increase in binding of bisecting GlcNAc-specific E-PHA (Fig. 7B) (40–42). The expression levels of five mDCIR2 mutants (N198A, Q199A, W201A, D223A, and H225A) on mutant mDCIR2 reporter cells were similar to that of the wild-type protein on BWZ.mDCIR2 cells as monitored by anti-DCIR2 antibody detection using flow cytometry (data not shown). The wild-type mDCIR2 reporter cells responded to GnT-III-transfected Lec8mgatIII cells but not to untransfected Lec8 cells, confirming that DCIR2 specifically bound to bisecting GlcNAc-containing glycans (Fig. 7C). In contrast, mDCIR2 reporter cells with any one of the three mutations (N198A, W201A, and D223A) had a completely abolished response to Lec8mgatIII cells, whereas either of the other two mutants (Q199A and H225A) had a partially ablated response (Fig. 7C). These results clearly suggest that Asn-198, Trp-201, and Asp-223 of mDCIR2 are essential for mDCIR2 binding to the bisecting GlcNAc-containing glycans and that Gln-199 and His-225 also contribute to the binding. The replacement of Asn-198 with alanine may impair Ca2+ coordination and abolish carbohydrate binding. It is noteworthy that the side chain of Trp-201 adopts alternative conformations in the ligand-containing complex structure (supplemental Fig. S1). One conformer of the indole ring makes a weak van der Waals contact with OH6 of GlcNAc-5. The indole ring of the other conformer weakly interacts with the side chain of Glu-202. The carboxyl oxygen of Glu-202 coordinates the calcium ion; consequently, the Trp-201 side chain may stabilize the conformation of the Glu-202 side chain required for Ca2+ coordination. Asp-223 directly interacts with the bisecting GlcNAc residue, and the impairment in ligand binding in the D223A mutant suggests a large contribution of bisecting GlcNAc to the interaction between mDCIR2 and bisected glycan.

Comparison of the Binding Mode with C-type Lectin DC-SIGN

mDCIR2 and DC-SIGN belongs to C-type II lectin receptors, and thus we compared the ligand binding modes of each lectin. Crystal structures of DC-SIGN with a set of different oligosaccharides such as biantennary complex-type, high mannose-type, and fucose-containing glycans are available (43–45). mDCIR2 was found not to prefer these glycans. Moreover, DC-SIGN has been found to predominantly interact with the α1-6 branch and the α1-3-linked mannose of both biantennary complex-type and high mannose-type glycans (PDB codes 1K9I and 1SL4 (43, 44)). Comparisons of the mDCIR2 structure with DC-SIGN in complex with a complex-type biantennary glycan revealed that the ligand interaction modes are different (Fig. 8A). The conformations of the α1-3 branches are quite similar in the two structures; however, the conformations of the α1-6 arm are distinct (Fig. 8B). In the biantennary complex-type glycan bound to DC-SIGN, the dihedral angles of the α1-6 linkage ψ, φ, and ω are 167°, 71°, and 48°, respectively. The difference in the ω angle of the α1-6 linkage (−156° for mDCIR2) may be due to crystal packing with the symmetry-related molecule or the presence of ethylene glycol between the bisecting GlcNAc and the α1-6 arm on mDCIR2. Structural superposition clearly demonstrates that the sugar ring of α1-3-linked mannose (Man-4) in mDCIR2 is rotated around the axis, perpendicular to the C3-C4 bond; hence, the positions of the OH3 and OH4 groups are reversed (Fig. 8C). Therefore, the ligand/receptor orientations are completely different between DC-SIGN and mDCIR2. Structural superposition of the mDCIR2 CRD and the DC-SIGN ligands shows a severe steric clash between the α1-6 arm of the ligand and the protruded β3-β4 loop region, especially Lys-210 of mDCIR2 (Fig. 8D). Moreover, structural superposition of the DC-SIGN CRD and the mDCIR2 ligands also shows that the GlcNAc residue of the α1-3 arm of the ligand (GlcNAc-5) causes a severe steric clash with Phe-313 and Asn-367 of DC-SIGN (Fig. 8E). DC-SIGN shows the highest affinity for the oligosaccharide Man9GlcNAc2 among the high mannose-type glycans (44). This high affinity binding arises from the multiple binding modes of Manα1–2Man at the primary binding site (45). However, the protruded loop region (Asn-208–Trp-214) of mDCIR2 forms a narrow carbohydrate binding site (Fig. 8F) and may thus prohibit binding of high mannose-type glycans despite the flexibility and bonding potential. The presence of the protruded β3-β4 loop might be a common feature of the DCIR family (Fig. 1); thus, DCIR family members may bind poorly to high mannose-type ligands.

FIGURE 8.

Structural comparison between DC-SIGN-biantennary glycan complex and the mDCIR2-bisected glycan complex. A, structural comparison between mDCIR2 in complex with a bisected complex-type glycan (cyan, left panel) and DC-SIGN in complex with a bi-antennary glycan (PDB code 1K9I, pink, right panel) (43). Protein molecules, carbohydrate residues, and calcium ions are shown in ribbon, stick, and sphere models, respectively. B, structural comparison between a bisected glycan bound to mDCIR2 and a non-bisected, bi-antennary glycan bound to DC-SIGN. C, close-up view of the ligand binding sites. Coordination bonds between mannose and the calcium ion are shown in red dotted lines. D, structural superposition of biantennary glycan (magenta) complexed with DC-SIGN and mDCIR2 (cyan). Lys-210 of mDCIR2 is shown in a rod and sphere model. The β3-β4 loop of mDCIR2 is highlighted in blue. E, structural superposition of the bisected glycans of the mDCIR2 complex (cyan) and DC-SIGN. The side chains of DC-SIGN are shown in rod and sphere models. F, structural superposition of DC-SIGN (magenta) and mDCIR2 (cyan). Carbohydrate-binding site is indicated with red dotted line.

DISCUSSION

In this study we provided the first insights into the molecular basis of the receptor/ligand recognition mechanism of bisecting GlcNAc-containing glycans. Our results show that mouse DCIR2 mainly recognizes three carbohydrate residues, including bisecting GlcNAc (Man-4, GlcNAc-5, and GlcNAc-7). The hexasaccharide ligand is trident-shaped. The positions of two disaccharide units (Man-4 and GlcNAc-5) of both branches relate to the approximate 2-fold symmetry along the bisecting GlcNAc (GlcNAc-7)-core Man (Man-3) axis. We found that the disaccharide unit (Man-4′ and GlcNAc-5′) of the α1-6 branch superimposes well on the corresponding unit (Man-4 and GlcNAc-5) of the α1-3 branch (supplemental Fig. S2). However, in this case mDCIR2 CRD could not directly interact with the bisecting GlcNAc over the α1-6 branch, because the bisecting GlcNAc is not positioned within hydrogen-bonding distance to mDCIR2. In addition, the ligand binding sites of the symmetry-related molecules are located far from the α1-6 branch and cannot be used for its recognition in the crystal (supplemental Fig. S3). These features account for the specific recognition of mDCIR2 for bisecting GlcNAc along the α1-3 branch. The asymmetrical branch-specific recognition is also explained by the structures. Thus, there is no space to accommodate the galactose on the α1-3 arm. In contrast, galactosylation on the α1-6 arm will not disrupt the ligand-protein interaction because that arm is not directly involved in the interaction. We could not determine the exact position of the reducing GlcNAc residue because our ligand did not have the di-N-acetylchitobiose portion. Nonetheless, the plausible location of the di-N-acetylchitobiose moiety is distant from the ligand binding site (supplemental Fig. S4). Asymmetrical branch recognition of mDCIR2 is rare among glycan-lectin interactions, an example being PELa from Platypodium elegans, which recognizes asymmetrical complex-type N-glycans (46). A short branch of one mannose residue is preferred along the α1-6 arm, and extensions of GlcNAc, galactose, and N-acetylneuraminic acid are tolerated on the α1-3 arm.

We found two entries containing the coordinates of bisecting GlcNAc in the PDB. One structure is of snake venom metalloproteinase catrocollastatin/vascular apoptosis-inducing protein 2B (VAP2B) (PDB code 2DW2) (47), and the other is of a glycoform-engineered human Fc fragment (PDB code 3SGK) (48). In these entries the bisecting GlcNAc-containing glycans are covalently attached to asparagine side chains in each protein. Consistent with the MD simulations, the structural variation in the α1-3 arm is smaller than in the α1-6 arm among three entries (Fig. 9). In the vascular apoptosis-inducing protein 2B structure, the α1-6 arm assumes a backfold conformation, which is the most stable conformer according to MD simulations. In contrast, the bisecting GlcNAc-containing glycan of the Fc fragment (PDB code 3SGK) assumes an extend-b conformation (φ = 80°, ψ = 170°, and ω = 168°; Fig. 9), and the structure superimposes well on the structure of our ligand.

FIGURE 9.

Structural comparison of complex-type N-glycans containing bisecting GlcNAc. The bisected glycans complexed with mDCIR2, snake venom metalloproteinase catrocollastatin/vascular apoptosis-inducing protein (VAP 2B) (PDB code 2DW2) (47), and a glycoform-engineered human Fc fragment (PDB code 3SGK) (48) are shown in cyan, magenta, and white stick models, respectively.

Human and mouse DCIR family members share a common structural scaffold, but specific binding to cognate glycans could occur by subtle changes in the polypeptide orientation. Recent glycan microarray analysis revealed that human BDCA-2, which is also known as CLEC4C and CD303, binds biantennary complex-type glycans with a terminal galactose (49). BDCA-2 CRD shares 54% amino acid sequence identity with mDCIR2 CRD. Trp-201, Asp-223, and His-225 of mDCIR2 are replaced with Asp-146, Val-169, and Gln-171 in BDCA-2, respectively (Fig. 1). The substitution of Asp-223 with Val may abolish the hydrogen bonds with the bisecting GlcNAc-containing glycan. Human DCIR shares 54% amino acid sequence identity with mDCIR2. Importantly, Asp-223, which directly interacts with bisecting GlcNAc in mouse DCIR2, is replaced by Gly-225 in human DCIR. Although the ligand binding specificity of human DCIR is not known, this difference may not allow human DCIR to bind bisected glycans. Mouse DCIR2 CRD shows the highest sequence identity with mouse DC activating receptor-1 (DCAR1; 72%) and mouse DCIR3 (67%) among the DCIR family members (Fig. 1). Mouse DCAR1 and mouse DCIR3 CRDs also possess an aspartic acid corresponding to Asp-223, and their ligand binding properties might be similar to those of mouse DCIR2.

Using the amino acid sequence of mDCIR2 CRD as a query sequence, BLAST searches of the NCBI non-redundant protein database identified several proteins with high sequence identities in closely related species. Asp-223, the sole amino acid residue that directly interacts with the bisecting GlcNAc residue, is conserved between rat DCIR2, DCIR3 (50), and Chinese hamster CLEC4A proteins (XP-003510222). In contrast, Trp-201 is not conserved among similar proteins in different species, which suggests that the Trp side chain is not essential for ligand recognition. The severe consequences of mutating Trp-201 in mouse DCIR2 to alanine may be due to the disruption of the local conformation around the ligand binding site. Ligand characterization of these proteins is a challenge for future studies.

DCs are known to comprise several subsets. Two major types of DCs are found in the mouse spleen; one is positive for CD8 and CD205 (CD8+DEC205+), and the other lacks CD8 but expresses DCIR2 (CD8−DCIR2+). CD8+DEC205+ DCs are specialized for cross-presentation, i.e. the capacity to present extracellular antigens to CD8+ T cells in complexes with major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules, whereas CD8−DCIR2+ DCs are specialized for presentation of MHC class II molecules (11). CD8− DC subsets are subdivided into two further subsets based on their expression of either DCIR2 or DCAL2 (dendritic cell-associated C-type lectin 2, CLEC12A). DCAL2+(DCIR2−) and CD8+ DC subsets preferentially induce T helper 1 responses, whereas DCIR2+ DCs predominantly induce T helper 2 responses (51). Thus, each DC subset has distinct roles in immunity to infection and in the maintenance of self-tolerance. The physiological role of mDCIR2 is still unclear but may play a specific function in the DCIR2-expressing DC subset by binding to bisected N-glycan expressed on endogenous or exogenous proteins.

GlcNAc-terminated bisecting GlcNAc-containing N-glycan with proximal fucose is abundant in the mouse brain, especially in the cerebrum, cerebellum, and brain stem (52). In mouse tissues, a high level of expression of GnT-III mRNA is observed in the brain and kidney (53, 54). Mutated mice with a truncated, inactive GnT-III show neurological dysfunction (18). A glycan profile of C57BL/6 mice demonstrated that GlcNAc-terminated, bisecting GlcNAc-containing glycans are detected in various tissues such as the colon, intestine, kidney, spleen, and testis (consortium for functional glycomics; Functional Glycomics Gateway). These observations suggest that the role of mDCIR2 is to bind a subset of glycoproteins in various tissues.

During N-glycan processing and maturation, the α1-6 arm undergoes multistep structural changes, suggesting that the α1-6 arm is heterogeneous. In contrast, the α1-3 arm is more homogeneous, and a recognition preference for this arm and bisecting GlcNAc seems to be a strategy for mDCIR2 to bind to N-glycans with α1-6 arm heterogeneity. The addition or removal of galactose on the α1-3 branch seems to strictly regulate mDCIR2 function. Galactosylation of complex-type glycans on several proteins was reported to correlate directly with physiological conditions. The major glycan attached to transferrin from human cerebrospinal fluid is an agalacto-biantennary complex-type structure with bisecting GlcNAc and core fucose (55), and the levels are increased in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (56). Another example is immunoglobulin G (IgG), the glycan structure of which has been extensively characterized for different disease conditions. The carbohydrate structures of N-glycans of human serum IgG are mainly biantennary, complex-type glycans, some of which contain bisecting GlcNAc. Agalactosylation of the N-glycan on IgG occurs in a number of inflammatory autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (57). Although the glycan structure of mouse IgG contains biantennary complex-type sugar chains without bisecting GlcNAc (58), the degree of galactosylation of serum IgG is significantly decreased in autoimmune mice (59). In addition, the expression level of GnT-III is affected by various biological stimulants such as bisdemethoxycurcumin (60). DCIR2 may function to detect subtle environmental changes triggered by immune responses and oxidative stress. Further studies on the structure-function relationships of mDCIR2 are warranted to reveal the detailed functional role of mDCIR2 in vivo.

In conclusion, mouse DCIR2 is the first bisecting GlcNAc-specific lectin to be structurally characterized. The structure of mDCIR2 CRD in complex with a specific glycan provides a detailed mechanism for selective binding of complex-type glycans containing bisecting GlcNAc. The presence of bisecting GlcNAc enables unique asymmetric α1-3 branch recognition by mDCIR2, in sharp contrast to the binding mode of the well characterized C-type lectin DC-SIGN.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the Photon Factory (Tsukuba, Japan) for providing data collection facilities and support. We thank Dr. Yukishige Ito (RIKEN) and Prof. Osamu Kanie (Tokai University) for allowing use of the cryoprobe-equipped NMR and Noriko Tanaka for secretarial assistance.

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (C) 25460054 (to Y. Y.) and for Young Scientists (B) 24770111 (to M. N.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 3VYJ and 3VYK) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

T. Nishimura et al., manuscript in preparation.

S. Hanashima et al., manuscript in preparation.

- DC

- dendritic cell

- mDCIR2

- mouse DCIR2

- DC-SIGN

- DC-specific ICAM3-grabbing nonintegrin

- DCIR

- dendritic cell inhibitory receptor

- BDCA-2

- blood DC antigen-2

- HBS

- HEPES-buffered saline

- MD

- molecular dynamics

- E-PHA

- erythroagglutinating P. vulgaris agglutinin

- GnT-III

- N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase-III

- Bis-Tris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sancho D., Reis e Sousa C. (2012) Signaling by myeloid C-type lectin receptors in immunity and homeostasis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 30, 491–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Geijtenbeek T. B., Gringhuis S. I. (2009) Signalling through C-type lectin receptors. Shaping immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 465–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Figdor C. G., van Kooyk Y., Adema G. J. (2002) C-type lectin receptors on dendritic cells and Langerhans cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zelensky A. N., Gready J. E. (2005) The C-type lectin-like domain superfamily. FEBS J. 272, 6179–6217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kanazawa N., Okazaki T., Nishimura H., Tashiro K., Inaba K., Miyachi Y. (2002) DCIR acts as an inhibitory receptor depending on its immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif. J. Invest. Dermatol. 118, 261–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bates E. E., Fournier N., Garcia E., Valladeau J., Durand I., Pin J. J., Zurawski S. M., Patel S., Abrams J. S., Lebecque S., Garrone P., Saeland S. (1999) APCs express DCIR, a novel C-type lectin surface receptor containing an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif. J. Immunol. 163, 1973–1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meyer-Wentrup F., Benitez-Ribas D., Tacken P. J., Punt C. J., Figdor C. G., de Vries I. J., Adema G. J. (2008) Targeting DCIR on human plasmacytoid dendritic cells results in antigen presentation and inhibits IFN-α production. Blood 111, 4245–4253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meyer-Wentrup F., Cambi A., Joosten B., Looman M. W., de Vries I. J., Figdor C. G., Adema G. J. (2009) DCIR is endocytosed into human dendritic cells and inhibits TLR8-mediated cytokine production. J. Leukoc. Biol. 85, 518–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaden S. A., Kurig S., Vasters K., Hofmann K., Zaenker K. S., Schmitz J., Winkels G. (2009) Enhanced dendritic cell-induced immune responses mediated by the novel C-type lectin receptor mDCAR1. J. Immunol. 183, 5069–5078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nussenzweig M. C., Steinman R. M., Witmer M. D., Gutchinov B. (1982) A monoclonal antibody specific for mouse dendritic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 79, 161–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dudziak D., Kamphorst A. O., Heidkamp G. F., Buchholz V. R., Trumpfheller C., Yamazaki S., Cheong C., Liu K., Lee H. W., Park C. G., Steinman R. M., Nussenzweig M. C. (2007) Differential antigen processing by dendritic cell subsets in vivo. Science 315, 107–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee R. T., Hsu T. L., Huang S. K., Hsieh S. L., Wong C. H., Lee Y. C. (2011) Survey of immune-related, mannose/fucose-binding C-type lectin receptors reveals widely divergent sugar-binding specificities. Glycobiology 21, 512–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lambert A. A., Gilbert C., Richard M., Beaulieu A. D., Tremblay M. J. (2008) The C-type lectin surface receptor DCIR acts as a new attachment factor for HIV-1 in dendritic cells and contributes to trans- and cis-infection pathways. Blood 112, 1299–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Narasimhan S. (1982) Control of glycoprotein synthesis. UDP-GlcNAc:glycopeptide β4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase III, an enzyme in hen oviduct which adds GlcNAc in β1–4 linkage to the β-linked mannose of the trimannosyl core of N-glycosyl oligosaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 10235–10242 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miwa H. E., Song Y., Alvarez R., Cummings R. D., Stanley P. (2012) The bisecting GlcNAc in cell growth control and tumor progression. Glycoconj. J. 29, 609–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Takahashi M., Kuroki Y., Ohtsubo K., Taniguchi N. (2009) Core fucose and bisecting GlcNAc, the direct modifiers of the N-glycan core. Their functions and target proteins. Carbohydr. Res. 344, 1387–1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stanley P. (2002) Biological consequences of overexpressing or eliminating N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase-TIII in the mouse. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1573, 363–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bhattacharyya R., Bhaumik M., Raju T. S., Stanley P. (2002) Truncated, inactive N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase III (GlcNAc-TIII) induces neurological and other traits absent in mice that lack GlcNAc-TIII. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 26300–26309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shibukawa Y., Takahashi M., Laffont I., Honke K., Taniguchi N. (2003) Down-regulation of hydrogen peroxide-induced PKCδ activation in N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase III-transfected HeLaS3 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 3197–3203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shigeta M., Shibukawa Y., Ihara H., Miyoshi E., Taniguchi N., Gu J. (2006) β1,4-N-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase III potentiates β1 integrin-mediated neuritogenesis induced by serum deprivation in Neuro2a cells. Glycobiology 16, 564–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Isaji T., Gu J., Nishiuchi R., Zhao Y., Takahashi M., Miyoshi E., Honke K., Sekiguchi K., Taniguchi N. (2004) Introduction of bisecting GlcNAc into integrin α5β1 reduces ligand binding and down-regulates cell adhesion and cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 19747–19754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Takahashi N., Nakagawa H., Fujikawa K., Kawamura Y., Tomiya N. (1995) Three-dimensional elution mapping of pyridylaminated N-linked neutral and sialyl oligosaccharides. Anal. Biochem. 226, 139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nakagawa H., Kawamura Y., Kato K., Shimada I., Arata Y., Takahashi N. (1995) Identification of neutral and sialyl N-linked oligosaccharide structures from human serum glycoproteins using three kinds of high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 226, 130–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fujii S., Nishiura T., Nishikawa A., Miura R., Taniguchi N. (1990) Structural heterogeneity of sugar chains in immunoglobulin G. Conformation of immunoglobulin G molecule and substrate specificities of glycosyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 6009–6018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Takahashi N., Ishii I., Ishihara H., Mori M., Tejima S., Jefferis R., Endo S., Arata Y. (1987) Comparative structural study of the N-linked oligosaccharides of human normal and pathological immunoglobulin G. Biochemistry 26, 1137–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vagin A., Teplyakov A. (2010) Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 22–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot. Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lovell S. C., Davis I. W., Arendall W. B., 3rd, de Bakker P. I., Word J. M., Prisant M. G., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2003) Structure validation by Cα geometry: φ, ψ, and Cβ deviation. Proteins 50, 437–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krissinel E., Henrick K. (2004) Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2256–2268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lütteke T., Bohne-Lang A., Loss A., Goetz T., Frank M., von der Lieth C. W. (2006) GLYCOSCIENCES.de. An Internet portal to support glycomics and glycobiology research. Glycobiology 16, 71R–81R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Drickamer K. (1999) C-type lectin-like domains. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 9, 585–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Holm L., Rosenström P. (2010) Dali server. Conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W545–W549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Feinberg H., Taylor M. E., Weis W. I. (2007) Scavenger receptor C-type lectin binds to the leukocyte cell surface glycan Lewisx by a novel mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 17250–17258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Re S., Miyashita N., Yamaguchi Y., Sugita Y. (2011) Structural diversity and changes in conformational equilibria of biantennary complex-type N-glycans in water revealed by replica-exchange molecular dynamics simulation. Biophys. J. 101, L44–L46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nishima W., Miyashita N., Yamaguchi Y., Sugita Y., Re S. (2012) Effect of bisecting GlcNAc and core fucosylation on conformational properties of biantennary complex-type N-glycans in solution. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 8504–8512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wurzburg B. A., Tarchevskaya S. S., Jardetzky T. S. (2006) Structural changes in the lectin domain of CD23, the low-affinity IgE receptor, upon calcium binding. Structure 14, 1049–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Qin S. Y., Hu D., Matsumoto K., Takeda K., Matsumoto N., Yamaguchi Y., Yamamoto K. (2012) Malectin forms a complex with ribophorin I for enhanced association with misfolded glycoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 38080–38089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Irimura T., Tsuji T., Tagami S., Yamamoto K., Osawa T. (1981) Structure of a complex-type sugar chain of human glycophorin A. Biochemistry 20, 560–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cummings R. D., Kornfeld S. (1982) Characterization of the structural determinants required for the high affinity interaction of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides with immobilized Phaseolus vulgaris leukoagglutinating and erythroagglutinating lectins. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 11230–11234 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yamashita K., Hitoi A., Kobata A. (1983) Structural determinants of Phaseolus vulgaris erythroagglutinating lectin for oligosaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 14753–14755 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Feinberg H., Mitchell D. A., Drickamer K., Weis W. I. (2001) Structural basis for selective recognition of oligosaccharides by DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. Science 294, 2163–2166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Guo Y., Feinberg H., Conroy E., Mitchell D. A., Alvarez R., Blixt O., Taylor M. E., Weis W. I., Drickamer K. (2004) Structural basis for distinct ligand-binding and targeting properties of the receptors DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 591–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Feinberg H., Castelli R., Drickamer K., Seeberger P. H., Weis W. I. (2007) Multiple modes of binding enhance the affinity of DC-SIGN for high mannose N-linked glycans found on viral glycoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 4202–4209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Benevides R. G., Ganne G., Simões Rda C., Schubert V., Niemietz M., Unverzagt C., Chazalet V., Breton C., Varrot A., Cavada B. S., Imberty A. (2012) A lectin from Platypodium elegans with unusual specificity and affinity for asymmetric complex N-glycans. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 26352–26364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Igarashi T., Araki S., Mori H., Takeda S. (2007) Crystal structures of catrocollastatin/VAP2B reveal a dynamic, modular architecture of ADAM/adamalysin/reprolysin family proteins. FEBS Lett. 581, 2416–2422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ferrara C., Grau S., Jäger C., Sondermann P., Brünker P., Waldhauer I., Hennig M., Ruf A., Rufer A. C., Stihle M., Umaña P., Benz J. (2011) Unique carbohydrate-carbohydrate interactions are required for high affinity binding between FcγRIII and antibodies lacking core fucose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 12669–12674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Riboldi E., Daniele R., Parola C., Inforzato A., Arnold P. L., Bosisio D., Fremont D. H., Bastone A., Colonna M., Sozzani S. (2011) Human C-type lectin domain family 4, member C (CLEC4C/BDCA-2/CD303) is a receptor for asialo-galactosyl-oligosaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 35329–35333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Flornes L. M., Bryceson Y. T., Spurkland A., Lorentzen J. C., Dissen E., Fossum S. (2004) Identification of lectin-like receptors expressed by antigen presenting cells and neutrophils and their mapping to a novel gene complex. Immunogenetics 56, 506–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kasahara S., Clark E. A. (2012) Dendritic cell-associated lectin 2 (DCAL2) defines a distinct CD8α− dendritic cell subset. J. Leukocyte Biol. 91, 437–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shimizu H., Ochiai K., Ikenaka K., Mikoshiba K., Hase S. (1993) Structures of N-linked sugar chains expressed mainly in mouse brain. J. Biochem. 114, 334–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bhaumik M., Seldin M. F., Stanley P. (1995) Cloning and chromosomal mapping of the mouse Mgat3 gene encoding N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase III. Gene 164, 295–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nairn A. V., York W. S., Harris K., Hall E. M., Pierce J. M., Moremen K. W. (2008) Regulation of glycan structures in animal tissues. Transcript profiling of glycan-related genes. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 17298–17313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hoffmann A., Nimtz M., Getzlaff R., Conradt H. S. (1995) “Brain-type” N-glycosylation of asialo-transferrin from human cerebrospinal fluid. FEBS Lett. 359, 164–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Futakawa S., Nara K., Miyajima M., Kuno A., Ito H., Kaji H., Shirotani K., Honda T., Tohyama Y., Hoshi K., Hanzawa Y., Kitazume S., Imamaki R., Furukawa K., Tasaki K., Arai H., Yuasa T., Abe M., Arai H., Narimatsu H., Hashimoto Y. (2012) A unique N-glycan on human transferrin in CSF. A possible biomarker for iNPH. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 1807–1815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Parekh R. B., Dwek R. A., Sutton B. J., Fernandes D. L., Leung A., Stanworth D., Rademacher T. W., Mizuochi T., Taniguchi T., Matsuta K. (1985) Association of rheumatoid arthritis and primary osteoarthritis with changes in the glycosylation pattern of total serum IgG. Nature 316, 452–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mizuochi T., Hamako J., Titani K. (1987) Structures of the sugar chains of mouse immunoglobulin G. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 257, 387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mizuochi T., Hamako J., Nose M., Titani K. (1990) Structural changes in the oligosaccharide chains of IgG in autoimmune MRL/Mp-lpr/lpr mice. J. Immunol. 145, 1794–1798 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fiala M., Liu P. T., Espinosa-Jeffrey A., Rosenthal M. J., Bernard G., Ringman J. M., Sayre J., Zhang L., Zaghi J., Dejbakhsh S., Chiang B., Hui J., Mahanian M., Baghaee A., Hong P., Cashman J. (2007) Innate immunity and transcription of MGAT-III and Toll-like receptors in Alzheimer's disease patients are improved by bisdemethoxycurcumin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 12849–12854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]