Background: Inefficient functional receptor expression in heterologous expression systems has hampered investigations of α6* nAChRs.

Results: Determinants in the α6 subunit for α6β4* functionality have been delineated.

Conclusion: Phe223 and the intracellular loop in α6 are molecular impediments to functional α6β4* nAChR expression in vitro.

Significance: The molecular basis for the inefficient functional expression of α6β4* nAChRs in vitro has been elucidated.

Keywords: Cell Surface Receptor, Cys-loop Receptors, Ion Channels, Neurotransmitter Receptors, Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors

Abstract

Explorations into the α6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α6* nAChRs) as putative drug targets have been severely hampered by the inefficient functional expression of the receptors in heterologous expression systems. In this study, the molecular basis for the problem was investigated through the construction of chimeric α6/α3 and mutant α3 and α6 subunits and functional characterization of these co-expressed with β4 or β4β3 subunits in tsA201 cells in a fluorescence-based assay and in Xenopus oocytes using two-electrode voltage clamp electrophysiology. Substitution of a small C-terminal segment in the second intracellular loop or the Phe223 residue in transmembrane helix 1 of α6 with the corresponding α3 segment or residue was found to enhance α6β4 functionality in tsA201 cells significantly, in part due to increased cell surface expression of the receptors. The gain-of-function effects of these substitutions appeared to be additive since incorporation of both α3 elements into α6 resulted in assembly of α6β4* receptors exhibiting robust functional responses to acetylcholine. The pharmacological properties exhibited by α6β4β3 receptors comprising one of these novel α6/α3 chimeras in oocytes were found to be in good agreement with those from previous studies of α6* nAChRs formed from other surrogate α6 subunits or concatenated subunits and studies of other heteromeric nAChRs. In contrast, co-expression of this α6/α3 chimera with β2 or β2β3 subunits in oocytes did not result in efficient formation of functional receptors, indicating that the identified molecular elements in α6 could be specific impediments for the expression of functional α6β4* nAChRs.

Introduction

The nicotinic acetylcholine (ACh)2 receptors (nAChRs) mediate the rapid signaling of ACh and are widely distributed in the central nervous system (CNS) and in the periphery (1, 2). The receptors are membrane-bound complexes assembled from five subunits, each consisting of a large extracellular N-terminal domain (NTD), a transmembrane domain (TMD) consisting of four transmembrane α-helices (TM1–TM4) connected by intracellular and extracellular loops, including a large second intracellular loop (ICL), and a short extracellular C terminus. Thus, the pentameric nAChR complex comprises three structural entities: an extracellular domain containing the orthosteric sites, a transmembrane domain containing the ion channel, and an intracellular domain, the three entities being assembled from the NTDs, the TMDs, and the ICLs of the five subunits, respectively (1, 2).

The relatively promiscuous assembly of neuronal nAChRs from a total of eight α (α2–α7, α9, and α10) and three β (β2–β4) subunits gives rise to a plethora of physiologically relevant subtypes characterized by different distributions and distinct biophysical, kinetic, and pharmacological properties (1–3). The key roles played by this heterogeneous receptor population for cholinergic neurotransmission and for other neurotransmitter systems make them interesting as therapeutic targets in several neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders (1, 2, 4).

The distribution of α6-containing nAChRs (α6* nAChRs) in the CNS is very restricted as these receptors predominantly are found in the visual system and in catecholaminergic pathways (5, 6). Extensive investigations have identified the α6β2β3 and α6α4β2β3 subtypes localized on dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area as key modulators of dopamine release in striatum and nucleus accumbens (7–16), making the receptors interesting in connection with Parkinson disease and nicotine addiction (4, 6, 17). Although not having been subjected to the same meticulous exploration as α6β2* receptors, α6β4* nAChRs have recently been reported to regulate norepinephrine release in mouse hippocampus (18), to play a major role for exocytosis in human adrenal gland chromaffin cells (19), and to be expressed in rat dorsal root ganglia (20).

The exploration of α6* nAChRs as putative drug targets has been hampered severely by the difficulties associated with efficient expression of functional receptors in heterologous expression systems (6, 21). Several approaches have been applied to overcome this obstacle. First, co-expression of chimeric α6/α3 or α6/α4 subunits (α6-NTD fused with α3- or α4-TMD/ICL) with β2, β2β3, and β4 subunits results in formation of functional receptors in both mammalian cells and oocytes (22–27). Second, the minute responses observed for α6β2β3 and α6β4β3 nAChRs in oocytes have been found to be dramatically enhanced by the introduction of a β3V273S mutant in the receptors (28, 29). Finally, expression of functional α6β2β3 and α6α4β2β3 nAChRs in oocytes has recently been accomplished by linking subunits in pentameric constructs; this concatemerization somehow makes up for the absence of whatever cellular factors that enables the formation of functional wild type (WT) receptors in neurons (26). Although these approaches have provided valuable tools for in vitro studies of α6* nAChRs, all of these are nevertheless modified receptors with the ever present uncertainty as to whether their functional characteristics diverge from those of WT α6* nAChRs (6).

In the present study, we further investigated the molecular determinants underlying the difficulties connected with in vitro expression of functional α6* nAChRs. A considerable number of novel α6/α3 chimeras and several α6 and α3 mutants were constructed, and the functional properties of the receptors assembled from these subunits and various β subunits in mammalian cells and Xenopus oocytes were characterized. Two molecular elements in the α6 subunit were identified as important determinants, or rather impediments, of the expression of functional α6β4* nAChRs in heterologous expression systems.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Culture medium, serum, and antibiotics were purchased from Invitrogen. ACh, (S)-nicotine, and chemicals used for the buffers were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; (−)-cytisine, (+)-tubocurarine, and mecamylamine were purchased from Ascent Scientific (Bristol, UK); and (±)-epibatidine, varenicline, and sazetidine A were obtained from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK). The FLIPR Membrane PotentialTM Blue (FMP) dye was purchased from Molecular Devices (Crawley, UK), and Xenopus laevis oocytes were obtained from Lohmann Research Equipment (Castrop-Rauxel, Germany). The cDNAs encoding for the human α3, β2, and β4 nAChR subunits were kind gifts from Dr. M. L. Jensen (NeuroSearch A/S, Denmark), and human α6 and β3 nAChR cDNAs were kind gifts from Dr. J. Lindstrom (University of Pennsylvania) and L. G. Sivilotti (University College London, London, UK), respectively. 5-HT3A and 5-HT3B cDNAs were kind gifts from Drs. J. Egebjerg (H. Lundbeck A/S, Denmark) and E. F. Kirkness (The J. Craig Venter Institute), respectively.

Molecular Biology

The cDNAs of the α3, α6, β2, β3, and β4 nAChR subunits were amplified by the original vectors by PCR and subcloned into the pcDNΑ3.1+ vector by use of the unique restriction sites NheI and XhoI (α3, α6, β3, and β4) or NotI and XhoI (β2). The chimeric α6/α3 subunits were constructed using splicing by overlap extension PCR (30). This method was also used to insert a nucleotide sequence encoding for the c-myc epitope into α6, α3, and selected α6/α3 chimeras and α6 mutants. The c-myc nucleotide sequence was inserted immediately downstream of the nucleotide sequence encoding for the signal peptide in each of the plasmids (α6, -Val-Gly|Cys1-Ala2-; α3, -Arg-Ala|Ser1-Glu2-). Point mutations were introduced by using QuikChange® site-directed mutagenesis according to the manufacturer's protocol (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA). The integrity and the absence of unwanted mutations in all cDNAs created by PCR were verified by DNA sequencing (Eurofins MWG Operon, Martinsried, Germany).

Cell Culture and Transfections

The tsA201 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium + GlutaMAXTM-I supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. The cells were split into 6-cm (1 × 106 cells) or 10-cm (2 × 106 cells) tissue culture plates and transfected the following day with a total of 4 μg (6-cm plate) or 8 μg (10-cm plate) of cDNA in a 1:1 α:β4 ratio using PolyFect® transfection reagent according to the protocol of the manufacturer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The cells were used for the experiments 40–48 h after the transfection.

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The ELISA was performed essentially as described previously (54). The tsA201 cells transfected with α3, myc-α3, myc-α6, myc-C1, myc-C2, myc-C6, or myc-α6F223L cDNAs together with β4 cDNA were seeded into poly-d-lysine-coated 24-well plates (3 × 105 cells/well). The following day cells were washed in ice-cold wash buffer (phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 1 mm CaCl2) and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (in PBS) on ice for 12 min. The following steps were performed at room temperature. The cells were washed three times with assay buffer and incubated with a blocking solution (3% dry milk in 50 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm CaCl2, pH 7.5) for 20 min. After blocking, the cells were incubated with mouse anti-myc antibody (Invitrogen; diluted 1:500 in blocking solution) for 45 min. Then the cells were washed three times with wash buffer, incubated with blocking solution for 20 min, and incubated with goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated (Invitrogen; diluted 1:400 in blocking solution) for 45 min. The cells were then washed three times in wash buffer before receptor expression was quantified using the 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine liquid substrate system (Sigma-Aldrich). The reaction was quenched with 1 n H2SO4 after which the absorbance of the supernatants was determined at 450 nm. Total receptor expression levels of the respective myc-tagged subunits were determined by adding 0.1% Triton X-100 to the blocking solution used during the first round of blocking and the incubation with the primary antibody. Nonspecific binding was determined in parallel experiments on tsA201 cells expressing the WT (untagged) α3β4 nAChR, and the “basal” staining determined in these wells was subtracted from the staining observed in the other wells.

Whole Cell Binding Assay

The whole cell [3H]epibatidine binding experiments with tsA201 cells transiently expressing WT α3β4, WT α6β4, C1β4, C6F223Lβ4, and C16F223Lβ4 nAChRs were performed essentially as described previously for whole cell [3H]GR65630 binding to 5-HT3A receptors (31). The tsA201 cells were harvested in assay buffer (140 mm NaCl, 1.5 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm Mg2SO4, 25 mm HEPES, pH 7.4) using non-enzymatic cell dissociation solution (Sigma-Aldrich), counted, and divided into two equally sized fractions. Following centrifugation for 5 min, the resulting two cell pellets were resuspended to a concentration of 1 × 107 cells/ml in assay buffer (intact cell population) or in assay buffer supplemented with 0.1% saponin (permeabilized cell population) and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Visual inspection of the two cell populations mixed with trypan blue using a microscope confirmed that saponin treatment resulted in permeabilization of the cell membrane of virtually all cells (estimated >98%), whereas the cell membranes of virtually all non-treated cells were intact (estimated >98%). The samples were further diluted with assay buffer, and cells (1.5 × 105 cells/reaction) were mixed with 3 nm [3H]epibatidine in the absence (total binding) or presence of 300 μm (S)-nicotine (nonspecific binding) in a total assay volume of 1 ml and incubated for 4 h at room temperature while shaking. Whatman GF/C filters were presoaked for 1 h in 0.2% polyethyleneimine, and binding was terminated by filtration through these filters using a 48-well cell harvester followed by washing with 3 × 4 ml of ice-cold isotonic NaCl solution. Following this, the filters were dried, 3 ml of Opti-FluorTM (Packard) was added, and the amount of bound radioactivity was determined in a scintillation counter. The binding experiments were performed in duplicate three to four times for each receptor.

FMP Assay

The FMP assay was performed in poly-d-lysine-coated, black 96-well plates (BD Biosciences). Transfected tsA201 cells were seeded into these plates 16–24 h before the experiment. On the day of the experiment, the medium was aspirated, and the cells were washed with 100 μl of Krebs buffer (140 mm NaCl, 4.7 mm KCl, 2.5 mm CaCl2, 1.2 mm MgCl2, 11 mm HEPES, 10 mm d-glucose, pH 7.4). Then 100 μl of Krebs buffer supplemented with FMP dye (0.5 mg/ml) was added to the wells after which the plate was incubated at 37 °C in humidified 5% CO2 for 30 min and assayed in a NOVOstarTM plate reader (BMG LABTECH, Offenburg, Germany) measuring emission at 560 nm (in fluorescence units) caused by excitation at 530 nm before and up to 1 min after addition of 33 μl ACh solution in Krebs buffer. Experiments were performed in duplicate at least three times for each of the receptors. The concentration-response curves for ACh were constructed based on the differences in the fluorescence units between the maximal fluorescence levels recorded before and after addition of the agonist.

Preparation of cRNA and Injection in Xenopus Oocytes

The cDNA constructs were linearized with the unique restriction enzymes SmaI (α subunits) or StuI (β subunits) and used as templates for in vitro cRNA synthesis using the T7 mMESSAGE mMACHINE High Yield Capped RNA Transcription kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). For the initial comparisons of the functionalities of the C6F223Lβ4, C6F223Lβ2, and C6F223Lβ2β3 receptors with those of the corresponding receptors containing WT α6, WT α3, and the C1 chimera, 20–35 ng of cRNA of each subunit was used for the α3β4, C1β4, α3β2, α3β2β3, and C1β2β3 combinations, whereas 50–60 ng of cRNA of each subunit was used for the C6F223Lβ4, C6F223Lβ2β3, C6F223Lβ2, and α6β2β3 combinations. Up to 70–80 ng of cRNA of each subunit was used for the α6β2 and α6β4 combinations, respectively. For the subsequent in-depth characterization of the pharmacological properties of the C6F223Lβ4β3 nAChR, 46 ng of cRNA of each of the three subunits was used for the injections. All injections were carried out in total volumes of 20–46 nl. Following injection, oocytes were incubated at 18 °C in modified Barth's solution (88 mm NaCl, 1 mm KCl, 15 mm HEPES, 2.4 mm NaHCO3, 0.41 mm CaCl2, 0.82 mm MgSO4, 0.3 mm Ca(NO3)2, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, pH 7.5). Electrophysiological recordings were performed 3–6 days after injection.

Electrophysiological Recordings

Electrophysiological recordings were performed using the two-electrode voltage clamp technique on Xenopus oocytes expressing the various receptors using a protocol adapted from previous studies (24, 27, 32). The oocytes were placed in a recording chamber continuously perfused with a saline solution (115 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 0.1 mm MgCl2). Oocytes were clamped at −40 to −90 mV by a GeneClamp 500B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA), and both voltage and current electrodes were filled with 3 m KCl. Six to eight different concentrations of the test compounds (in the saline solution described above) were applied until saturation followed by saline perfusion for 4–6 min (C6F223Lβ4, C1β4, and WT α3β4 recordings) or 2.5 min (C6F223Lβ4β3 recordings). Experiments were performed at room temperature on at least four oocytes from at least two different batches of oocytes for each subtype. Data were normalized to the maximum current elicited by ACh at the individual oocyte.

Data Analysis

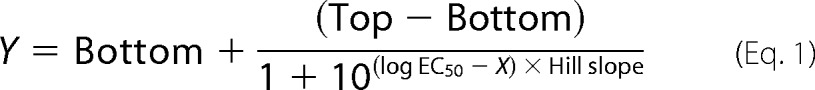

All data analysis and curve fitting were performed using GraphPad Prism, version 5a (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Concentration-response curves for agonists constructed based on the data obtained in the FMP assay and the oocyte recordings were fitted by non-linear regression using the equation for sigmoidal dose response with variable slope,

|

where X represents the logarithm of the agonist concentration, Y represents the response, and “Top” and “Bottom” represent the plateaus in units of the y axis. Concentration-inhibition curves for mecamylamine in the oocyte recordings were fitted to a sigmoidal curve with variable slope using nonlinear regression,

|

where X is the logarithm of the antagonist concentration, Y is the response, and Top and Bottom are the plateaus in units of the y axis.

Specific binding in the [3H]epibatidine whole cell binding experiments was defined as the difference between measured total and nonspecific binding. In the ELISA experiments, specific binding of anti-myc antibody was determined as the difference between A450 measured for the cells expressing the myc-tagged constructs and the A450 measured for cells expressing WT (untagged) α3β4 nAChR on the same plate.

RESULTS

Molecular Determinants in the ICL of α6 for the Expression of Functional α6β4 nAChRs

In a search for putative molecular elements in the α6 subunit underlying the problems obtaining efficient in vitro expression of functional α6* nAChRs, a series of 16 α6/α3 chimeras (termed C1–C16) were constructed, co-expressed with the WT β4 nAChR subunit in tsA201 cells, and characterized functionally in the fluorescence-based FMP assay (Figs. 1–3 and Table 1).

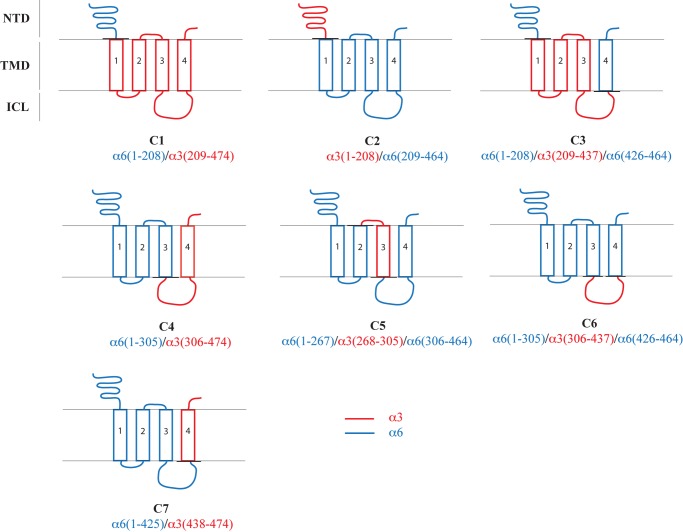

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the compositions of the α6/α3 chimeras C1–C7. The α6 and α3 segments are given in blue and red, respectively.

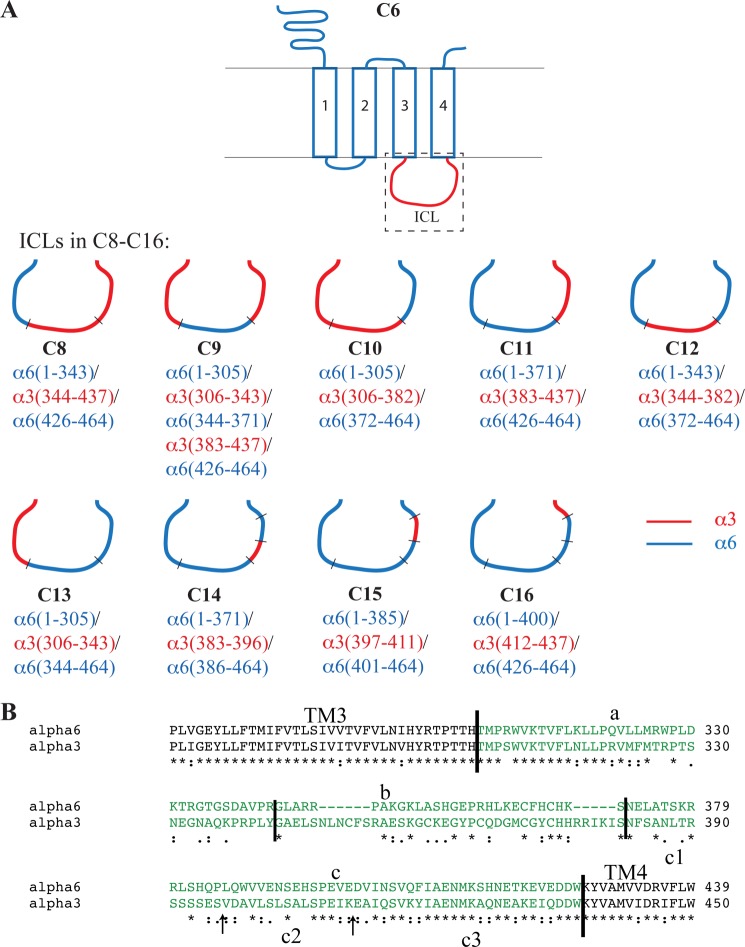

FIGURE 2.

A, schematic representation of the compositions of the α6/α3 chimeras C8–C16. The α6 and α3 segments are given in blue and red, respectively. B, alignment of parts of the amino acid sequences of the human α6 and α3 nAChR subunits. The second intracellular loops in the subunits are given in green. The a, b, and c segments of mixed α6/α3 compositions in the loops of chimeras C8–C13 are indicated above the sequences, and the c1, c2, and c3 segments of mixed α6/α3 compositions in chimeras C14–C16 are indicated below the sequences. The arrows represent the fusion points of the C14–C16 chimeras.

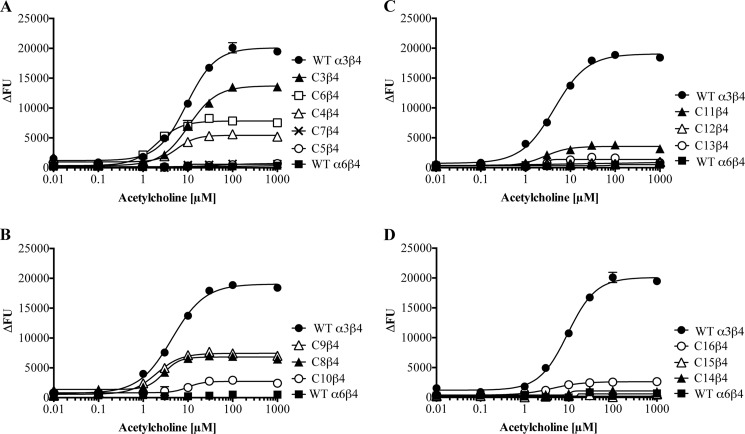

FIGURE 3.

A–D, concentration-response curves for ACh at tsA201 cells co-expressing WT α3, WT α6, or α6/α3 chimeras with the WT β4 nAChR subunit in the FMP assay. The concentration-response curves depicted in the graphs were obtained on the same day. The experiments were performed three times in duplicate for all receptors containing chimeras. The data presented in the figure represent a representative experiment, and the data are given as mean ± S.E. (error bars) of duplicate measurements. FU, fluorescence units.

TABLE 1.

Functional properties of ACh at tsA201 cells co-expressing WT α3, WT α6, or 16 chimeric α6/α3 subunits with the WT β4 subunit in the FMP assay

Rmax/Rmax(α3β4) (%), Rmax of the specific chimera co-expressed with WT β4 relative to the Rmax value of WT α3β4 nAChR on the same 96-well plate. N.R., no significant response. The data are given as mean ± S.E. values from experiments performed in duplicate. Statistical analysis was only performed for the Rmax values exhibited by chimeras C9–C16.

| Subunit | EC50 (pEC50 ± S.E.) | nH ± S.E. | Rmax/Rmax (α3β4) ± S.E. | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | % | |||

| α3 (WT) | 8.7 (5.11 ± 0.04) | 1.3 ± 0.040 | 100 | 25 |

| C1 | 14 (4.85 ± 0.01) | 1.1 ± 0.07 | 80 ± 6.8 | 3 |

| C2 | 5.2 (5.29 ± 0.08) | 2.1 ± 0.15 | 13 ± 1.5 | 3 |

| C3 | 11 (4.95 ± 0.05) | 1.4 ± 0.13 | 72 ± 8.1 | 3 |

| C4 | 7.0 (5.16 ± 0.08) | 1.8 ± 0.31 | 31 ± 3.6 | 3 |

| C5 | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 3 |

| C6 | 2.4 (5.62 ± 0.07) | 1.6 ± 0.05 | 38 ± 4.5 | 3 |

| C7 | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 3 |

| C8 | 2.7 (5.56 ± 0.03) | 1.9 ± 0.30 | 32 ± 4.6 | 3 |

| C9 | 1.9 (5.72 ± 0.04) | 1.6 ± 0.03 | 41 ± 5.9a | 3 |

| C10 | 8.3 (5.10 ± 0.09) | 2.1 ± 0.32 | 12 ± 1.6b | 3 |

| C11 | 2.3 (5.62 ± 0.06) | 1.6 ± 0.15 | 22 ± 3.7c | 3 |

| C12 | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 3 |

| C13 | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 3 |

| C14 | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 3 |

| C15 | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 3 |

| C16 | 4.7 (5.33 ± 0.07) | 1.7 ± 0.43 | 9.0 ± 3.1 | 3 |

| α6 (WT) | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 19 |

a Significant difference from WT α6β4, p < 0.001.

b Significant difference from WT α6β4, p < 0.05.

c Significant difference from WT α6β4, p < 0.01.

In contrast to α6, the α3 subunit efficiently forms functional receptors in combination with β2, β2β3, and β4 subunits in heterologous expression systems. Furthermore, it is the nAChR subunit most homologous to α6, making it ideal to use in this study. In concordance with the literature (22, 24), ACh was found to elicit a robust functional response in tsA201 cells expressing the WT α3β4 nAChR in the FMP assay, whereas no significant response could be detected in WT α6β4-expressing cells (Tables 1 and 2 and Figs. 3 and 4). The WT α3β4 and WT α6β4 nAChRs were included as controls on all plates in the subsequent functional characterization of the receptors formed by chimeras C1–C16 in combination with WT β4. The dramatically different functionalities of the two WT receptors enabled us to relate the effects on α6β4 signaling arising from various chimeric and mutant subunits to two fairly black-and-white references. The study was performed as an iterative process in which the results for chimeras obtained in one round formed the basis for the construction of additional chimeras to be studied in the next round.

TABLE 2.

Functional properties of ACh at tsA201 cells co-expressing WT α3, WT α6, α6 mutant, or α3 mutant subunits with the WT β4 subunit in the FMP assay

Rmax/Rmax(α3β4) (%), Rmax of the specific chimera co-expressed with WT β4 relative to the Rmax value of WT α3β4 nAChR on the same 96-well plate. N.R., no significant response. The data are given as mean ± S.E. values from experiments performed in duplicate.

| Subunit | EC50 (pEC50 ± S.E.) | nH ± S.E. | Rmax/Rmax (α3β4) ± S.E. | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | % | |||

| α3 (WT) | 8.7 (5.11 ± 0.04) | 1.3 ± 0.04 | 100 | 25 |

| α3L211M | 7.3 (5.14 ± 0.03) | 1.5 ± 0.04 | 103 ± 0.24 | 3 |

| α3L223F | 6.2 (5.21 ± 0.02) | 1.5 ± 0.01 | 64 ± 1.3 | 3 |

| α3L211M/L223F | 6.4 (5.21 ± 0.08) | 1.3 ± 0.16 | 56 ± 7.1 | 3 |

| α6M211L | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 3 |

| α6F223L | 9.6 (5.02 ± 0.05) | 1.8 ± 0.20 | 18 ± 3.4 | 3 |

| α6M211L/F223L | 13 (4.90 ± 0.02) | 1.7 ± 0.15 | 22 ± 3.5 | 3 |

| α6 (WT) | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | 19 |

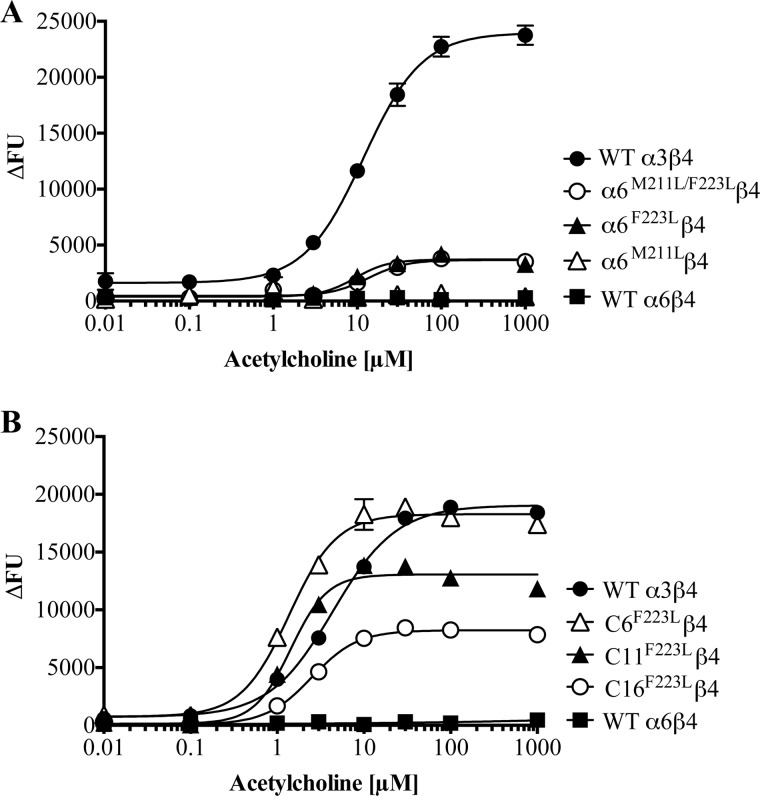

FIGURE 4.

A, concentration-response curves for ACh at tsA201 cells co-expressing WT α3, WT α6, α6M211L, α6F223L, or α6M211/F223L with the WT β4 nAChR subunit in the FMP assay. B, concentration-response curves for ACh at tsA201 cells co-expressing WT α3, WT α6, C6F223L, C11F223L, or C16F223L with the WT β4 nAChR subunit in the FMP assay. The concentration-response curves depicted in the graphs were obtained on the same day. The experiments were performed three times in duplicate for all receptors containing chimeras. The data presented in the figure represent a representative experiment, and the data are given as mean ± S.E. (error bars) of duplicate measurements. FU, fluorescence units.

As mentioned in the Introduction, α6NTD/α3TMD/ICL and α6NTD/α4TMD/ICL subunits form functional receptors together with β subunits in heterologous expression systems (22–27). In contrast, co-expression of α3NTD/α6TMD/ICL and α4NTD/α6TMD/ICL chimeras with β2 or β2β3 in oocytes does not result in functional receptors, and although the chimeras have been reported to form some functional receptors with β4, these are characterized by dramatically impaired functionalities compared with WT α3β4 and α4β4 nAChRs (23, 27). Initially, these findings from the literature were verified through the functional characterization of the receptors assembled from chimeras C1 (α6NTD/α3TMD/ICL) and C2 (α3NTD/α6TMD/ICL) together with WT β4 in the FMP assay. ACh evoked a robust signal in a concentration-dependent manner in tsA201 cells expressing the C1β4 combination, giving rise to a maximal response comparable in size with that observed for the WT α3β4 nAChR (Table 1). The response elicited by the agonist through C2β4 was dramatically smaller, albeit this minute response was significantly higher than the complete lack of response observed in cells expressing the WT α6β4 nAChR (Table 1). Thus, the functional properties exhibited by C1β4 and C2β4 were in good agreement with those observed previously for the receptors (23, 27).

The properties displayed by C1β4 and C2β4 strongly implicated the TMD and/or the ICL in α6 as domains containing “problem regions/residues” for assembly of functional α6β4 nAChRs. To shed further light on these molecular elements, all chimeras subsequently generated comprised “pure” α6 NTDs and “mixed” α6/α3 TMD/ICL regions (Fig. 1). Of the five chimeras in the next round, only C3, C4, and C6 formed functional complexes with WT β4 (Table 1 and Fig. 3A). All of these chimeras contain an ICL composed completely of α3, and particularly informative was chimera C6 consisting of pure α6 NTD and TMD and a pure α3 ICL. In contrast, chimeras C5 and C7 with ICLs consisting completely of α6 did not form functional receptors with β4, further substantiating the notion of the ICL in α6 constituting a problem for the functional expression of α6β4 nAChRs.

In the next round of chimeras, the ICLs of α6 and α3 were divided into three segments, a, b, and c, containing 21, 31, and 30 residues differing between α6 and α3, respectively (Fig. 2B). In the C8–C13 chimeras, the a, b, and c segments from the two subunits were combined in various combinations, whereas the NTDs and TMDs of all chimeras were pure α6 (Fig. 2A). Functional characterization of these chimeras co-expressed with WT β4 identified the c segment of the ICL as a particularly “problematic” segment for the expression of functional α6β4 nAChRs, as the maximal responses elicited by ACh in cells expressing chimera C8 (α6 a segment, α3 bc segments) and C9 (α6 b segment, α3 ac segments) together with β4 were considerably higher than that for chimera C10 (α6 c segment, α3 ab segments) (Table 1 and Fig. 3B). The pattern of functionality was not completely black and white because C10β4 was functional albeit very compromised compared with C6β4 (Fig. 3 and Table 1). On the other hand, the pattern observed for the C11β4, C12β4, and C13β4 receptors supported a key role of the c segment for α6β4 function. Here, C11 (α6 ab segments, α3 c segment) was capable of forming functional receptors with β4, whereas cells expressing the C13β4 (α6 bc segments, α3 a segment) or C12β4 (α6 ac segments, α3 b segment) combinations were completely non-responsive to ACh (Fig. 3C and Table 1).

In the final round of chimeras, the c segments were further subdivided into three segments, c1, c2, and c3, in a way so that each of the three segments contained 10 non-conserved residues between α6 and α3 (Fig. 2B). In the C14, C15, and C16 chimeras, the c1, c2, and c3 segments of α3 were introduced in α6, respectively (Fig. 2A). Whereas ACh did not elicit agonist responses in cells transfected with the C14β4 and C15β4 combinations, a small but significant response was observed in C16β4-expressing cells, identifying the c3 segment as an important region for functional expression of α6β4 receptors (Table 1 and Fig. 3D). The 10 residues in the c3 segment of α6 not conserved in α3 were subsequently mutated to the respective corresponding α3 residues, and the mutants (α6D401E, α6V402A, α6N404Q, α6Q407K, α6F408Y, α6S415A, α6H416Q, α6T419A, α6V422I, and α6E423Q) were co-expressed with WT β4 in tsA201 cells and tested for functionality in the FMP assay. None of these mutant receptors exhibited a significant functional response to ACh exposure in the assay (data not shown). We did not attempt to further narrow down the molecular determinants for α6β4 function in this segment.

Molecular Determinants in TM1 of α6 for the Expression of Functional α6β4 nAChRs

Although substitution of the ICL in α6 with that of α3 yielded functional receptors, the substantially smaller responses evoked by ACh through C6β4 compared with C1β4 indicated that TMD elements in α6 also could contribute to the poor in vitro functionality of α6β4 nAChRs (Table 1). Although TM4 and the extracellular C terminus are the α6-TMD regions comprising most non-conserved residues compared with other α nAChR subunits, the non-responsiveness of C7β4 and the comparable responses evoked by ACh through C3β4 and C1β4 strongly suggested that any such elements are not harbored in these regions. Instead, the considerably smaller maximal response elicited by ACh through C4β4 than through C1β4 identified the six non-conserved residues in the TM1–TM3 region as candidates (Fig. 3A and Table 1). The non-responsiveness of C5β4 containing α3 residues in four of these six positions as well as the findings in a recent study prompted us to focus on the two non-conserved residues in TM1: Leu211 and Leu223 in α3 corresponding to Met211 and Phe223 in α6, respectively. In this recent study, the maximal current amplitudes recorded from oocytes expressing α3L211Mβ2 and α3L223Fβ2 nAChRs were demonstrated to be significantly reduced compared with those of the WT α3β2 nAChR (26). To investigate the importance of these two TM1 residues for α6β4 nAChR function, the mutations L211M, L223F, and L211M/L223F were introduced in α3; the reverse M211L, F223L, and M211L/F223L mutations were introduced in α6, and the mutant subunits were co-expressed with WT β4 in tsA201 cells and characterized functionally in the FMP assay.

Analogously to the reported effect of the α3L223F mutant on α3β2 signaling (26), α3L223Fβ4 displayed a significantly reduced maximal response compared with that of WT α3β4 in the FMP assay. However, in contrast to the impaired signaling of α3L211Mβ2 nAChR (26), introduction of the L211M mutation into α3 did not change the maximal response of ACh at the α3β4 nAChR substantially (Table 2). Co-expression of α3L211M/L223F with β4 also resulted in the formation of receptors at which ACh exhibited a reduced maximal response compared with that at WT α3β4, the Rmax value of the agonist at the double mutant being very similar to that at the α3L223Fβ4 receptor (Table 2).

Strikingly, introduction of the F223L mutation in α6 resulted in the ability of the subunit to assemble into functional α6β4 receptors (Fig. 4A and Table 2). In contrast, the α6M211Lβ4 combination did not display a significant functional response to ACh. Analogously to the pattern observed for the α3 mutants, the α6M211L/F223Lβ4 receptor exhibited a functional response to ACh similar to that of α6F223Lβ4.

Additive Effects of Molecular Determinants in ICL and TM1 in α6 for the Expression of Functional α6β4 nAChRs

The observed rescue of α6β4 nAChR function from introduction of even small α3 segments into the ICL as well as by a single mutation (F223L) in the TM1 of α6 prompted us to investigate whether the effects of these ICL and TM1 substitutions on α6β4 function were additive. Introduction of the F223L mutation into the C6, C11, and C16 chimeras had dramatic augmenting effects on the functional properties of ACh at receptors containing all three chimeras, as the maximal responses exhibited by the agonist at C6F223Lβ4-, C11F223Lβ4-, and C16F223Lβ4-expressing cells were more than double the size of those at C6β4, C11β4, and C16β4, respectively (Table 3 and Fig. 4B).

TABLE 3.

Functional properties of ACh at tsA201 cells co-expressing WT α3; the chimeras C6, C11, or C16; or the point-mutated chimeras C6F223L, C11F223L, or C16F223L with the WT β4 subunit in the FMP assay

Rmax/Rmax(α3β4) (%), Rmax of the specific chimera co-expressed with WT β4 relative to the Rmax value of WT α3β4 on the same 96-well plate. N.R., no significant response. The data are given as mean ± S.E. values from experiments performed in duplicate.

| Subunit | EC50 (pEC50 ± S.E.) | Hill slope | Rmax/Rmax (α3β4) ± S.E. | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | % | |||

| α3 (WT) | 8.7 (5.11 ± 0.04) | 1.3 ± 0.04 | 100 | 25 |

| C6F223L | 1.4 (5.85 ± 0.01) | 1.6 ± 0.03 | 94 ± 1.6 | 2 |

| C6 | 2.4 (5.62 ± 0.07) | 1.6 ± 0.05 | 38 ± 4.5 | 3 |

| C11F223L | 1.3 (5.87 ± 0.03) | 3.0 ± 0.98 | 64 ± 2.6 | 2 |

| C11 | 2.3 (5.62 ± 0.06) | 1.6 ± 0.15 | 22 ± 3.7 | 3 |

| C16F223L | 3.5 (5.47 ± 0.10) | 1.1 ± 0.66 | 42 ± 0.46 | 2 |

| C16 | 4.7 (5.33 ± 0.07) | 1.7 ± 0.43 | 9.0 ± 3.1 | 3 |

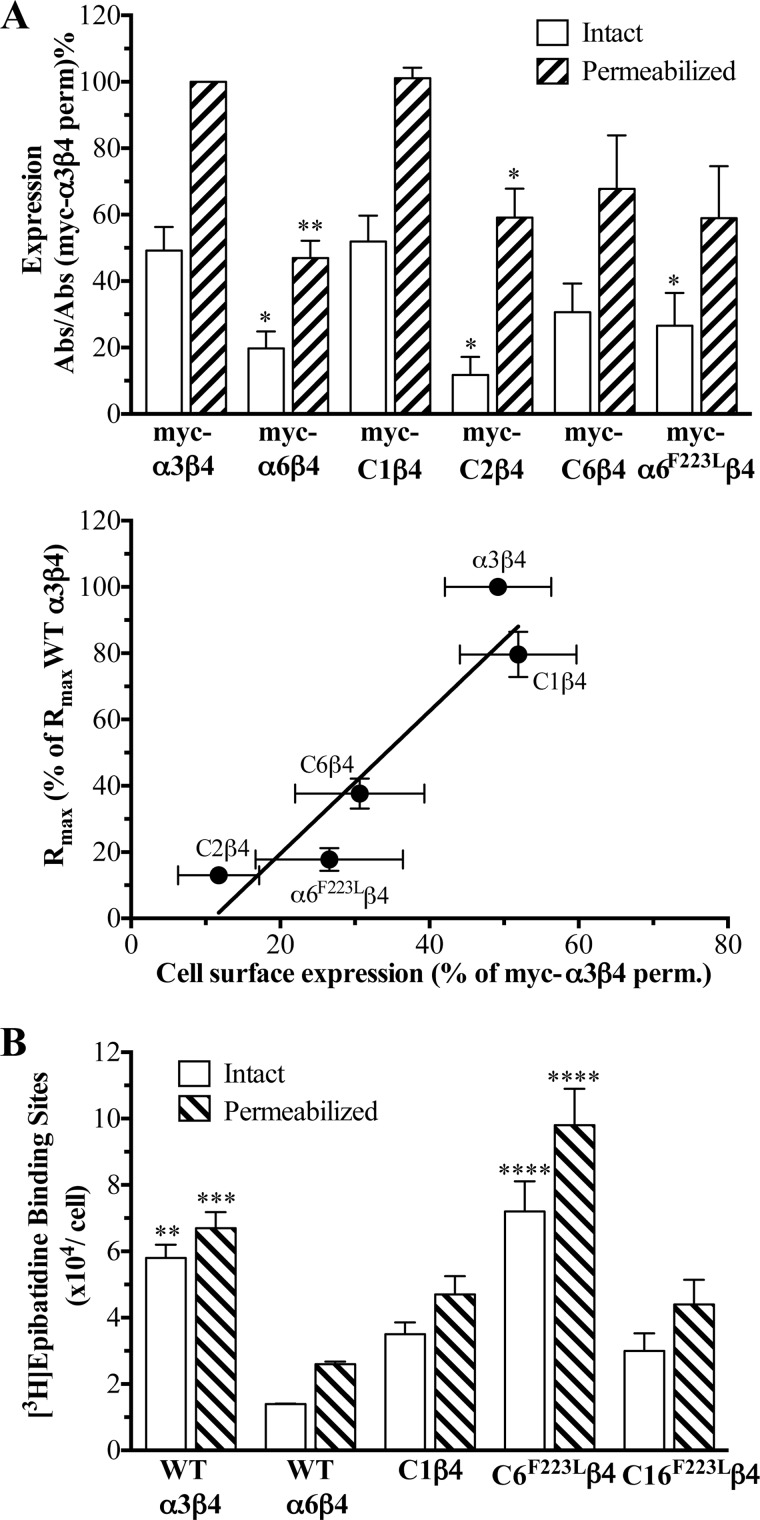

Cell Surface Expression Levels of Chimeric α6/α3 and Mutant α6 Subunits Co-expressed with WT β4 in tsA201 Cells

To elucidate to what extent the absolute number of receptors assembled in the cell membrane contributes to the respective functionalities in tsA201 cells, the cell surface expression levels of selected receptors were determined. In the first line of experiments, myc-tagged versions of WT α6, WT α3, C1, C2, C6, and the α6F223L mutant were co-expressed with WT β4 in tsA201 cells, and their expression patterns were investigated by ELISA. Insertion of the myc tag into α3 and C1 was found not to alter the functional properties of the α3β4 and C1β4 nAChRs (data not shown). Furthermore, the validity of the ELISA was verified in control experiments performed in parallel, where transfection of tsA201 cells with HA-tagged 5-HT3B was found not to result in significant cell surface expression, whereas co-expression of HA-5-HT3B with WT 5-HT3A gave rise to significant levels of cell surface expression of the HA-tagged subunit (54).

As can be seen from Fig. 5A, tsA201 cells transfected with the myc-α3β4 and myc-C1β4 combinations displayed significantly higher levels of “total” expression than cells expressing the myc-C2β4 and myc-α6β4 receptors. Furthermore, myc-α3β4 and myc-C1β4 displayed significantly higher cell surface expression than the myc-α6β4, myc-C2β4, and myc-α6F223Lβ4 combinations, whereas the cell surface expression of myc-C6β4 did not differ significantly (Fig. 5A). The relative cell surface expression, i.e. the percentage of the total number of myc-tagged subunits expressed at the cell surface, was very similar for five of the six receptors (40–52%) with myc-C2β4 being the outlier (18%). Interestingly, a distinct correlation was observed between the sizes of the maximal response evoked by ACh through the receptors in the FMP assay and their cell surface expression in the ELISA (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Cell surface and total expression of WT α3β4, WT α6β4, chimeric α6/α3β4, and mutant α6β4 nAChRs in tsA201 cells. A, top panel, cell surface and total expression of myc-tagged α3, α6, C1, C2, C6, and α6F223L subunits co-expressed with the β4 nAChR subunit in tsA201 cells determined by ELISA on intact cells (white bars) and permeabilized cells (hatched bars). Absorbance (Abs) was measured at λ = 450 nm and normalized to absorbance measured from permeabilized myc-α3β4-expressing cells on the same day on the same 24-well plate. The measured absorbance was background-corrected using the absorbance measured from WT (untagged) α3β4-transfected cells. Data are given as mean ± S.E. (error bars) of five to six independent experiments performed in triplicate. Asterisks indicate significant difference from myc-α3β4 and myc-C1β4: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. Bottom panel, correlation between the cell surface expression of the receptors and the maximal responses elicited by ACh through the receptors in the FMP assay. B, the numbers of cell surface-expressed and total numbers of [3H]epibatidine binding sites in tsA201 cells transiently expressing WT α3β4, WT α6β4, C1β4, C6F223Lβ4, and C16F223Lβ4 nAChRs. Specific [3H]epibatidine binding to intact cells (number of cell surface-expressed binding sites, white bars) and permeabilized (perm.) cells (total number of binding sites, hatched bars) is shown. Data are given as the means of three to four individual experiments performed in triplicate. Asterisks indicate significant difference from WT α6β4: **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001.

In another line of experiments, the number of binding sites for the orthosteric nAChR radioligand [3H]epibatidine in tsA201 cells transfected with WT α3β4, WT α6β4, C1β4, C6F233Lβ4, and C16F233Lβ4 nAChRs was determined in a whole cell binding assay using a saturating radioligand concentration (3 nm) and non-permeabilized and permeabilized cells (Fig. 5B). The number of [3H]epibatidine binding sites at the surface of WT α6β4-expressing cells was significantly lower than that for WT α3β4-expressing cells, and all three receptors containing chimeric α6/α3 subunits also displayed higher cell surface expression than WT α6β4, albeit the C6F233Lβ4 was the only receptor for which the difference was found to be significant (Fig. 5B).

The ELISA and whole cell binding experiments revealed a correlation between the cell surface expression levels of the receptors and their respective functionalities in the FMP assay. However, this correlation was not clear-cut, since some receptors with comparable levels of cell surface expression, for example C1β4 and C16F223Lβ4, displayed very different Rmax values in the functional assay (Tables 1 and 3 and Fig. 5). Furthermore, several receptors exhibiting a significant functional response to ACh in the FMP assay displayed surface expression levels similar to or only slightly higher than that of the non-functional WT α6β4 (Fig. 5). Thus, although increased levels of cell surface expression of the receptors arising from the modifications introduced in the α6 subunit in some of these chimeras and mutants certainly seem to contribute to the functional rescue of WT α6β4 function, the gain-of-function effects observed upon other α6 modifications cannot be ascribed to this factor.

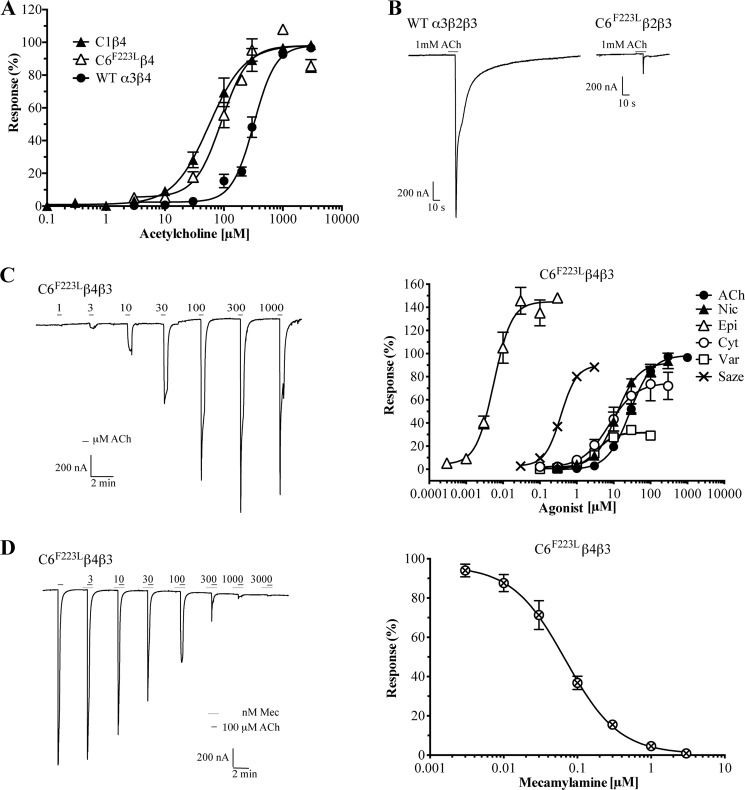

Functional Characterization of C6F223Lβ4* and C6F223Lβ2* nAChRs in Xenopus Oocytes

To investigate the functional properties of α6* nAChRs comprising one of the novel α6/α3 chimeras in a more conventional assay for ligand-gated ion channels, C6F223L, C1, WT α3, and WT α6 subunits were co-expressed with β4, β4β3, β2, or β2β3 subunits in Xenopus oocytes, and the assembled receptors were studied in two-electrode voltage clamp recordings.

Initially, we investigated whether the gain of function observed for C6F223Lβ4 compared with WT α6β4 in the FMP assay could be verified in the oocytes. Because of the extremely high expression levels of heterologously expressed proteins in this system, oocytes injected with WT α6β4 cRNA actually form functional receptors, albeit agonist-evoked currents recorded from these have been reported to be minute (21, 23, 29). Thus, in contrast to the black-and-white functional rescue of α6β4 function observed for the C6F223L chimera in the FMP assay, a comparison of the functionalities of WT α6β4 and C6F223Lβ4 nAChRs in oocytes had to be based on the sizes of the maximal current amplitudes evoked by ACh in oocytes injected with comparable amounts of cRNA encoding for the two receptors. We observed a clear correlation between the amounts of WT α6β4 cRNA injected into the oocytes and the current amplitude sizes evoked by 1 mm ACh in them. Upon injection of 70–80 ng of cRNA of each subunit for WT α6β4, maximal current amplitudes in the range of 300–600 nA were observed upon application of 1 mm ACh (Table 4). In contrast, upon injection with 50–60 ng of cRNA of each subunit, maximal current amplitudes of 20–50 nA were recorded in two oocytes, whereas no currents could be measured in three other oocytes (Table 4). Because injection of similar amounts of C6F223Lβ4 cRNA (50–60 ng of cRNA of each subunit) in oocytes resulted in the formation of receptors responding robustly to ACh with maximal current amplitudes of up to 10 μA, we conclude that the functionality of the α6β4 nAChR in the oocyte expression system is also substantially augmented by the modifications introduced in the C6F223L chimera.

TABLE 4.

Functional properties of various nAChRs assembled in oocytes co-expressing WT α3, WT α6, C1, or C6F223L with β4, β2, or β2β3 subunits

The amounts of cRNA (of each subunit) injected, the current amplitudes recorded upon application of 1 mm ACh, and the number of oocytes tested (n) are given for the different receptor combinations.

| Receptor | ng of cRNA of each subunit injected | Current amplitudes at 1 mm ACh | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT α3β4 | 20–35 | Up to 10–15 μA | 27 |

| WT α6β4 | 50–60 | 2 oocytes: 20–50 Na | 5 |

| 3 oocytes: no significant response | |||

| 70–80 | 300–600 nA | 3 | |

| C1β4 | 20–35 | Up to 3–4 μA | 6 |

| C6F223Lβ4 | 20–35 | 50–200 nA | 14 |

| 50–60 | Up to 10 μA | 32 | |

| WT α3β2 | 20–35 | 1–2 μA | 7 |

| WT α6β2 | 70–80 | No significant response | 3 |

| C6F223Lβ2 | 50–60 | No significant response | 14 |

| WT α3β2β3 | 20–35 | 1–2 μA | 18 |

| WT α6β2β3 | 50–60 | No significant response | 3 |

| C1β2β3 | 20–35 | Up to 3–4 μA | 3 |

| C6F223Lβ2β3 | 50–60 | 150–250 nA | 15 |

Next we compared the ACh-evoked currents through the C6F223Lβ4 nAChRs with those through WT α3β4 and C1β4 nAChRs. When similar amounts of cRNA for the WT α3β4 and C6F223Lβ4 combinations (20–35 ng of each subunit) were injected into the oocytes, the maximal current amplitudes measured for C6F223Lβ4 were consistently lower (50–200 nA) than those recorded in oocytes expressing WT α3β4 (up to 10–15 μm; Table 4). To obtain comparable maximal current amplitudes for all three receptor combinations in the following experiments, we injected double the amount of cRNA for C6F223Lβ4 (50–60 ng of each subunit) than for WT α3β4 and C1β4 (20–35 ng of each subunit).

ACh elicited robust currents in a concentration-dependent manner in oocytes expressing the WT α3β4, C1β4, and C6F223Lβ4 nAChRs (Fig. 6A). The ACh-evoked currents through C6F223Lβ4 were efficiently eliminated by application of reference nAChR antagonists (+)-tubocurarine (10 μm) and mecamylamine (3 μm) (data not shown). It should be mentioned that a pronounced decrease in maximal current amplitude was observed at ACh concentrations above 100 μm in some of the C6F223Lβ4-expressing oocytes, a phenomenon not observed for oocytes expressing WT α3β4 and C1β4 nAChRs (data not shown). The currents evoked by EC20 ACh concentrations applied before and after the recording of currents for a range of different ACh concentrations differed somewhat in recordings at these oocytes. A decrease in current amplitude was observed for the EC20 ACh application in the end of a run compared with that at the beginning, perhaps suggesting a more long lasting desensitization of this receptor than of WT α3β4 and C1β4. We nevertheless propose that the EC50 value determined for ACh at C6F223Lβ4 is a valid estimate of its actual potency at the receptor.

FIGURE 6.

Electrophysiological characterization of C6F223Lβ4, C6F223Lβ2β3, and C6F223Lβ4β3 nAChRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes. A, concentration-response curves for ACh at oocytes expressing WT α3β4, C1β4, and C6F223Lβ4 nAChRs. Data points represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) of determinations on four to five oocytes from two different batches. The EC50 values of ACh at WT α3β4, C1β4, and C6F223Lβ4 were 309 μm (pEC50 ± S.E., 3.51 ± 0.06; n = 7), 59 μm (pEC50 ± S.E.; 4.23 ± 0.08; n = 4), and 98 μm (pEC50 ± S.E., 4.01 ± 0.08; n = 5), respectively. B, representative traces of ACh-induced currents in oocytes expressing WT α3β2β3 and C6F223Lβ2β3 nAChRs. C, pharmacological properties exhibited by six reference nAChR agonists at the C6F223Lβ4β3 nAChR. Representative traces of the responses elicited by various concentrations of ACh through the C6F223Lβ4β3 nAChR (left) and concentration-response curves for ACh, (S)-nicotine (Nic), (±)-epibatidine (Epi), (−)-cytisine (Cyt), varenicline (Var), and sazetidine A (Saze) at the receptor (right) are shown. Data are given as the percentage of the maximal response obtained for ACh and represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) of determinations on four to five oocytes from two different batches. Pharmacological properties of the agonists (pEC50 ± S.E., nH ± S.E., Rmax ± S.E.) are as follows: ACh: 4.53 ± 0.05, 1.4 ± 0.1, 100; (S)-nicotine: 4.92 ± 0.08, 1.9 ± 0.4, 92 ± 7; (±)-epibatidine: 8.19 ± 0.04, 1.6 ± 0.1, 154 ± 10; (−)-cytisine: 5.08 ± 0.06, 1.2 ± 0.2, 76 ± 13; varenicline: 5.43 ± 0.03, 1.2 ± 0.2, 32 ± 3; sazetidine A: 6.40 ± 0.02, 2.1 ± 0.1, 91 ± 11. The maximal responses elicited by (±)-epibatidine, (−)-cytisine, and varenicline differed significantly from that of ACh at the receptor (****, p < 0.0001 for all three agonists). D, representative traces of the responses elicited by 100 μm ACh in oocytes expressing C6F223Lβ4β3 nAChRs in the presence of various concentrations of mecamylamine (Mec) (left) and the concentration-inhibition curve for mecamylamine at the receptor (right). Data are given as the percentage of the response elicited by 100 μm ACh in the absence of mecamylamine and represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) of determinations on six oocytes from two different batches. Pharmacological properties of mecamylamine are as follows: pIC50 ± S.E., 7.22 ± 0.06; nH ± S.E., −1.3 ± 0.2.

The physiological importance of the α6β2β3* nAChRs located on dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain prompted us to investigate the functional properties of these receptors expressed in oocytes. Although several different batches of cRNAs and oocytes were used in these experiments, applications of 1 mm ACh did not produce measurable responses in any of the WT α6β2- or C6F223Lβ2-expressing oocytes tested (Table 4). In contrast, ACh elicited robust currents through WT α3β2 with maximal current amplitudes in the 1–2-μA range (Table 4). Interestingly, application of 1 mm ACh consistently produced significant currents in C6F223Lβ2β3-expressing oocytes, whereas the WT α6β2β3 nAChR was completely non-responsive to the agonist (Table 4 and Fig. 6B). The fact that measurable currents could be recorded at C6F223Lβ2β3 but not at C6F223Lβ2 seems to be in concordance with previous reports of β3-mediated enhancement of α6* nAChR expression and function (23, 33). However, the amplitudes of the currents recorded for C6F223Lβ2β3 were small (150–250 nA) compared with those elicited by 1 mm ACh through the WT α3β2β3 and C1β2β3 nAChRs (Table 4).

Finally, we performed a detailed pharmacological characterization of the C6F223Lβ4β3 nAChR in oocytes (Fig. 6C). This subtype was chosen for these studies because the pronounced co-localization of α6 and β3 is suggestive of the presence of β3 in the majority of α6β4* complexes in vivo (6). In these recordings, the duration of the intermediate saline perfusions between the drug applications was reduced from the 4–6 min used in the C6F223Lβ4 recordings to 2.5 min. We did not see the same degree of run-down in the C6F223Lβ4β3 recordings as for the C6F223Lβ4 nAChR, which may also in part be ascribed to a stabilizing effect of β3 in the nAChR complex analogous to that observed previously for WT α6β4β3 and α6β4 nAChRs (23).

Six reference nAChR agonists were all found to evoke currents through the C6F223Lβ4β3 nAChR in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6C). The rank order of agonist potencies at C6F223Lβ4β3 was (±)-epibatidine > sazetidine A > varenicline > (−)-cytisine ∼ (S)-nicotine > ACh. The current amplitudes evoked by sazetidine A through the receptor decreased dramatically at high concentrations (>3 μm), a characteristic not observed for the other five agonists (data not shown). The maximal responses elicited by (S)-nicotine and sazetidine A through C6F223Lβ4β3 did not differ significantly from that evoked by ACh. In contrast, (±)-epibatidine was found to be a superagonist, and (−)-cytisine and varenicline displayed partial agonism at the receptor (Fig. 6C). Finally, ACh-evoked signaling through C6F223Lβ4β3 was antagonized in a concentration-dependent manner by the noncompetitive antagonist mecamylamine (Fig. 6D).

The pharmacological properties exhibited by the C6F223Lβ4β3 nAChR seem to be in good agreement with the limited literature data available. The rank order and the absolute values of the potencies of ACh, (S)-nicotine, (−)-cytisine, and (±)-epibatidine are in concordance with those obtained in previous studies of α6NTD/α4TMD/ICLβ4, chick α6-human β4, WT α6β4, and WT α6β4β3 nAChRs (21, 23, 24) and of other β4* nAChRs expressed in oocytes (2). However, in contrast to the pronounced partial agonist activity exhibited by (S)-nicotine at WT α6β4β3 (23), the maximal response of the agonist at C6F223Lβ4β3 in this study did not differ significantly from that of ACh (Fig. 6). Also, the superagonism displayed by (±)-epibatidine at the receptor differs from the full agonism reported for this agonist at WT α6β4 (23). As for the other agonists, the partial agonist activity of (−)-cytisine at C6F223Lβ4β3 is in concordance with previous studies of the agonist at chick α6-human β4 and α3β4 nAChRs (21, 34–36) just as the 32% efficacy exhibited by varenicline seems plausible considering its partial agonist activity at α4β2, α3β4, and α6NTD/α3TMD/ICLβ2β3 nAChRs (37, 38). Finally, the biphasic concentration-response relationship exhibited by sazetidine A seems plausible in light of previous reports of sazetidine A being a potent agonist and desensitizing agent of α4β2 nAChRs (39, 40). Finally, although the determined IC50 value of 60 nm for mecamylamine at C6F223Lβ4β3 admittedly is in the low end of IC50 values reported for the antagonist at heteromeric nAChRs (2), the antagonist has displayed comparable antagonist potencies at α3β4 nAChRs in some studies (41, 42).

DISCUSSION

The inefficient expression of functional α6* nAChRs in heterologous expression systems has been the subject of extensive investigations addressing the origin of the problem and attempting to circumvent it by various approaches. In the present study, we have identified two molecular impediments in α6 for the functional expression of α6β4* receptors: the Phe223 residue in TM1 and the ICL (in particular the C-terminal part).

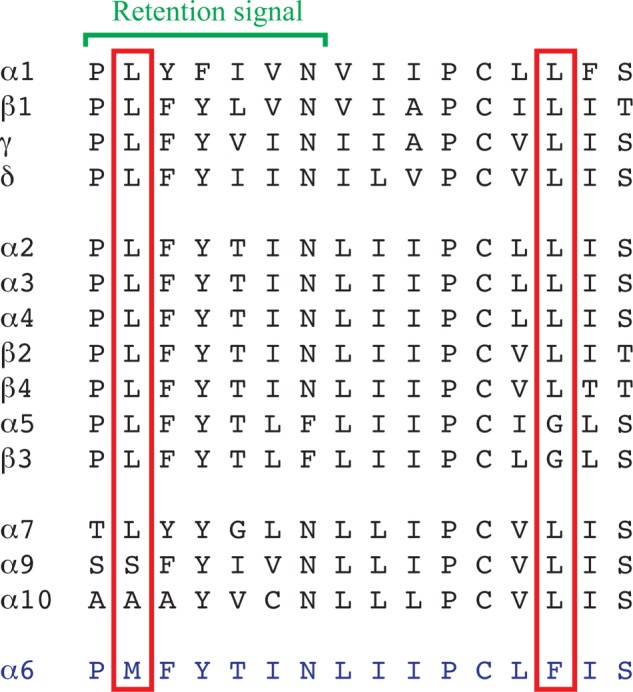

Because the focus of this study was on the α6 protein, it offers little insight into the putative neuronal factors or chaperones enabling expression of functional α6* receptors in vivo and does not address whether these are absent or compromised in vitro. Nevertheless, augmentation of α6β4* function arising from α6 modifications has to be interpreted in light of the current understanding of nAChR trafficking and assembly. In an elegant study, a conserved PL(Y/F)(F/Y)XXN motif in the TM1s of the α1, β1, γ, and δ subunits has been identified as a retention signal preventing the surface trafficking of unassembled subunits while being masked upon assembly into the muscle-type nAChR complex (43). Interestingly, the corresponding segment in α6 contains a methionine instead of highly conserved Leu residue (Fig. 7), and it has been speculated that this Met211 residue could disrupt the retention signal in α6, thereby impairing the assembly of mature α6* receptors in the endoplasmic reticulum (26). However, although an Ala mutation of Leu212 in the PLYFXXN sequence in α1 results in significantly decreased endoplasmic reticulum retention of the subunit (43), a Met residue in this position may not necessarily have a similar impact on endoplasmic reticulum retention, the Met residue being structurally more similar to Leu than Ala. Although the present study does not shed light on the role of Met211, introduction of the M211L mutation in α6 clearly does not rescue α6β4 function, and thus the residue seems unlikely to be the sole molecular impediment for efficient functional expression of the receptors in vitro.

FIGURE 7.

Amino acid sequence alignment of the Pro210–Ser225 segment of the TM1 of α6 and the corresponding segments of the other human nAChR subunits. The Met211 and Phe223 residues in α6 and the corresponding residues in the other nAChR subunits are boxed in red, and the location of the conserved retention signal in subunits forming heteromeric nAChR complexes is indicated with a green bracket.

The Phe223 residue located a couple of helix turns downstream of the TM1 retention signal is equally unique to α6 as Met211 compared with other nAChR subunits (Fig. 7). The modest functionality of the α6F223Lβ4 receptor could arise from an allosterically induced change in the conformation of the proximate retention motif or from a more direct effect of the introduced Leu residue on the assembly of the α6β4 complex and/or its allosteric transitions. Based on the localization of the corresponding residues in high resolution structures of the Torpedo AChR and Cys-loop receptor orthologs (44–46), Phe223 is predicted to be positioned in the TMD subunit interface of the α6* complex facing toward TM3 of the neighboring subunit. The Cys-loop receptor TMD subunit interface is a hot spot for allosteric modulation (1), and a molecular change in this region could be speculated to result in a receptor that is more responsive to agonist stimulation.

The C-terminal part of the ICL in α6 is likely to present a different molecular hindrance to functional expression of α6β4* receptors than Phe223. First of all, because of the sheer distance between the two molecular elements, it would be difficult to imagine modifications in this loop having an effect on the retention motif in TM1. Second, the contributions of deletions of the two elements to the enhancement of α6β4 functionality appears to be additive (Table 3 and Fig. 4B). A role of the α6-ICL for the inefficient expression of functional α6β4 receptors is not surprising considering reported involvement of ICLs in the trafficking, expression, and signaling of other nAChRs through their interactions with intracellular proteins (47–50). However, the molecular impediments to functional expression of α6β4 receptors comprised within the ICL are certainly less defined than Phe223, as we have not been able to pinpoint the problem to a specific residue or motif in the loop. Although substitution of the non-conserved residues contained in the C-terminal Asp412–Trp437 segment of the α6-ICL with the corresponding α3 residues results in a functional receptor (C16β4), the significantly higher maximal responses elicited by ACh through C11β4 and C6β4 and the small but significant response evoked through C10β4 could indicate that the entire ICL constitutes a molecular obstacle to functional receptor expression. Alternatively, introduction of an α3 segment instead of a segment in the α6-ICL region that does not in itself constitute a problem could induce a conformational change in the C-terminal part of the loop and thereby diminish the impact of a specific problematic molecular element located here.

In agreement with a previous study of WT α6β4 and α6NTD/α4TMD/ICLβ4 nAChRs (24), the receptors formed by the surrogate α6 subunits C1, C6F223L, and C16F223L with β4 were found to exhibit higher cell surface expression levels than WT α6β4 (Fig. 5B). However, although this definitely seems to be an important component of the augmented functionality of several of the receptors in this study, increased trafficking and/or incorporation of the subunits into receptor complexes in the cell membrane does not account for the gain-of-function effects arising from all α6 modifications. Thus, introduction of the Leu223 residue and/or an α3-ICL segment in α6 may also alter the allosteric transitions of the receptor, induce another subunit stoichiometry in the complex, or in other ways affect its functionality. Whatever the molecular mechanisms causing the augmented functionality of the α6β4* receptors containing these surrogate α6 subunits are, it is important to remember that neither Phe223 nor the C-terminal ICL segment in α6 constitute an insurmountable hindrance for expression of functional receptors in neurons. Thus, these so-called molecular impediments in α6 are really only in vitro manifestations existing in light of the deficiency of the heterologous expression system to efficiently express functional WT α6β4* nAChRs.

Interestingly, the C6F223L chimera exhibits strikingly different efficiency when it comes to the formation of functional α6β2* and α6β4* receptors. Although the minute currents elicited by ACh through C6F223Lβ2β3 can be considered a gain-of-function effect compared with the completely non-responsive WT α6β2β3, the molecular modifications introduced in α6 to facilitate functional expression of α6β4* receptors clearly do not translate into nearly as an efficient rescue of α6β2* function. In this respect, C6F223L differs from the classical α6NTD/α3TMD/ICL chimera (C1), but analogously the α6NTD/α4TMD/ICL chimera has been shown to form functional receptors with β4 but not with β2 (24), and co-expression of this chimera with β2β3 yields functional receptors (27). Furthermore, a complex pattern of subunit compatibilities has been observed for hybrid nAChRs formed from human and murine α6, β2, β4, β3, and β3V273S subunits (29). All these findings bear witness to the allosteric nature of the nAChR complex and illustrate one of the potential shortcomings of the surrogate α6 subunit: although the Leu223 residue and the α3-ICL in C6F223L appear to have overcome the inborn molecular impediments in α6 for assembly and expression of functional α6β4* nAChRs, other or additional elements in the subunit may counteract efficient formation of functional α6β2* receptors.

In conclusion, it is important to stress that we do not consider the novel α6/α3 chimeras presented in this study to be superior to other surrogate α6 subunits or other approaches used to express functional α6* nAChRs in vitro in previous studies. The higher α6 content in the C6F223L and C16F223L chimeras compared with the classical α6NTD/α3TMD/ICL and α6NTD/α4TMD/ICL chimeras may be considered an advantage for example when it comes to screenings for novel α6β4* ligands. On the other hand, the inefficient formation of functional α6β2* nAChRs from the chimeras clearly reduces the overall utility of the constructs. Furthermore, although the pharmacological properties exhibited by the C6F223Lβ4β3 nAChR seem to be in good agreement with previous findings for α6β4* and other nAChRs, the characteristics of these receptors cannot be assumed to mimic those of WT α6β4* nAChRs on all accounts, especially when considering the important role of the ICL in the Cys-loop receptor for its trafficking, assembly, and biophysical properties (51–53). Such concerns will inevitably exist for any α6* nAChR assembled from modified α6 subunits or concatamers, and thus the identification of the neuronal factors or chaperones enabling the expression of functional receptors in vivo and the resulting ability to express functional WT α6* nAChRs in heterologous expression systems would constitute a major leap forward in this field.

Acknowledgments

Drs. M. L. Jensen, J. Lindstrom, L. G. Sivilotti, J. Egebjerg, and E. F. Kirkness are thanked for the generous gifts of cDNAs.

This work was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation, The Aase and Ejner Danielsen Foundation, the Carlsberg Foundation, and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. Part of this work was presented in the form of a poster at the Society of Neuroscience conference in New Orleans on October 15, 2012.

- ACh

- acetylcholine

- FMP

- FLIPR Membrane Potential Blue

- nAChR

- nicotinic ACh receptor

- ICL

- second intracellular loop

- NTD

- N-terminal domain

- TMD

- transmembrane domain

- 5-HT

- 5-hydroxytryptamine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Taly A., Corringer P. J., Guedin D., Lestage P., Changeux J. P. (2009) Nicotinic receptors: allosteric transitions and therapeutic targets in the nervous system. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8, 733–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jensen A. A., Frølund B., Liljefors T., Krogsgaard-Larsen P. (2005) Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: structural revelations, target identifications, and therapeutic inspirations. J. Med. Chem. 48, 4705–4745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gotti C., Zoli M., Clementi F. (2006) Brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: native subtypes and their relevance. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 27, 482–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miwa J. M., Freedman R., Lester H. A. (2011) Neural systems governed by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: emerging hypotheses. Neuron 70, 20–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Quik M., Perez X. A., Grady S. R. (2011) Role of α6 nicotinic receptors in CNS dopaminergic function: relevance to addiction and neurological disorders. Biochem. Pharmacol. 82, 873–882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Letchworth S. R., Whiteaker P. (2011) Progress and challenges in the study of α6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 82, 862–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Champtiaux N., Han Z. Y., Bessis A., Rossi F. M., Zoli M., Marubio L., McIntosh J. M., Changeux J. P. (2002) Distribution and pharmacology of α6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors analyzed with mutant mice. J. Neurosci. 22, 1208–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Champtiaux N., Gotti C., Cordero-Erausquin M., David D. J., Przybylski C., Léna C., Clementi F., Moretti M., Rossi F. M., Le Novère N., McIntosh J. M., Gardier A. M., Changeux J. P. (2003) Subunit composition of functional nicotinic receptors in dopaminergic neurons investigated with knock-out mice. J. Neurosci. 23, 7820–7829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Salminen O., Murphy K. L., McIntosh J. M., Drago J., Marks M. J., Collins A. C., Grady S. R. (2004) Subunit composition and pharmacology of two classes of striatal presynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors mediating dopamine release in mice. Mol. Pharmacol. 65, 1526–1535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Quik M., Polonskaya Y., Gillespie A., Jakowec M., Lloyd G. K., Langston J. W. (2000) Localization of nicotinic receptor subunit mRNAs in monkey brain by in situ hybridization. J. Comp. Neurol. 425, 58–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Exley R., Clements M. A., Hartung H., McIntosh J. M., Cragg S. J. (2008) α6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors dominate the nicotine control of dopamine neurotransmission in nucleus accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 2158–2166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Perez X. A., Bordia T., McIntosh J. M., Quik M. (2010) α6β2* and α4β2* nicotinic receptors both regulate dopamine signaling with increased nigrostriatal damage: relevance to Parkinson's disease. Mol. Pharmacol. 78, 971–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gotti C., Guiducci S., Tedesco V., Corbioli S., Zanetti L., Moretti M., Zanardi A., Rimondini R., Mugnaini M., Clementi F., Chiamulera C., Zoli M. (2010) Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the mesolimbic pathway: primary role of ventral tegmental area α6β2* receptors in mediating systemic nicotine effects on dopamine release, locomotion, and reinforcement. J. Neurosci. 30, 5311–5325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drenan R. M., Grady S. R., Whiteaker P., McClure-Begley T., McKinney S., Miwa J. M., Bupp S., Heintz N., McIntosh J. M., Bencherif M., Marks M. J., Lester H. A. (2008) In vivo activation of midbrain dopamine neurons via sensitized, high-affinity α6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuron 60, 123–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Drenan R. M., Grady S. R., Steele A. D., McKinney S., Patzlaff N. E., McIntosh J. M., Marks M. J., Miwa J. M., Lester H. A. (2010) Cholinergic modulation of locomotion and striatal dopamine release is mediated by α6α4* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Neurosci. 30, 9877–9889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zoli M., Moretti M., Zanardi A., McIntosh J. M., Clementi F., Gotti C. (2002) Identification of the nicotinic receptor subtypes expressed on dopaminergic terminals in the rat striatum. J. Neurosci. 22, 8785–8789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Quik M., Wonnacott S. (2011) α6β2* and α4β2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as drug targets for Parkinson's disease. Pharmacol. Rev. 63, 938–966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Azam L., Maskos U., Changeux J. P., Dowell C. D., Christensen S., De Biasi M., McIntosh J. M. (2010) α-Conotoxin BuIA[T5A;P6O]: a novel ligand that discriminates between α6β4 and α6β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and blocks nicotine-stimulated norepinephrine release. FASEB J. 24, 5113–5123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pérez-Alvarez A., Hernández-Vivanco A., McIntosh J. M., Albillos A. (2012) Native α6β4* nicotinic receptors control exocytosis in human chromaffin cells of the adrenal gland. FASEB J. 26, 346–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hone A. J., Meyer E. L., McIntyre M., McIntosh J. M. (2012) Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in dorsal root ganglion neurons include the α6β4* subtype. FASEB J. 26, 917–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gerzanich V., Kuryatov A., Anand R., Lindstrom J. (1997) “Orphan” α6 nicotinic AChR subunit can form a functional heteromeric acetylcholine receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 51, 320–327 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dash B., Chang Y., Lukas R. J. (2011) Reporter mutation studies show that nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) α5 subunits and/or variants modulate function of α6*-nAChR. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 37905–37918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kuryatov A., Olale F., Cooper J., Choi C., Lindstrom J. (2000) Human α6 AChR subtypes: subunit composition, assembly, and pharmacological responses. Neuropharmacology 39, 2570–2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Evans N. M., Bose S., Benedetti G., Zwart R., Pearson K. H., McPhie G. I., Craig P. J., Benton J. P., Volsen S. G., Sher E., Broad L. M. (2003) Expression and functional characterisation of a human chimeric nicotinic receptor with α6β4 properties. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 466, 31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McIntosh J. M., Azam L., Staheli S., Dowell C., Lindstrom J. M., Kuryatov A., Garrett J. E., Marks M. J., Whiteaker P. (2004) Analogs of α-conotoxin MII are selective for α6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 65, 944–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kuryatov A., Lindstrom J. (2011) Expression of functional human α6β2β3* acetylcholine receptors in Xenopus laevis oocytes achieved through subunit chimeras and concatamers. Mol. Pharmacol. 79, 126–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Papke R. L., Dwoskin L. P., Crooks P. A., Zheng G., Zhang Z., McIntosh J. M., Stokes C. (2008) Extending the analysis of nicotinic receptor antagonists with the study of α6 nicotinic receptor subunit chimeras. Neuropharmacology 54, 1189–1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Broadbent S., Groot-Kormelink P. J., Krashia P. A., Harkness P. C., Millar N. S., Beato M., Sivilotti L. G. (2006) Incorporation of the β3 subunit has a dominant-negative effect on the function of recombinant central-type neuronal nicotinic receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 1350–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dash B., Bhakta M., Chang Y., Lukas R. J. (2011) Identification of N-terminal extracellular domain determinants in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) α6 subunits that influence effects of wild-type or mutant β3 subunits on function of α6β2*- or α6β4*-nAChR. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 37976–37989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Horton R. M., Hunt H. D., Ho S. N., Pullen J. K., Pease L. R. (1989) Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene 77, 61–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krzywkowski K., Jensen A. A., Connolly C. N., Bräuner-Osborne H. (2007) Naturally occurring variations in the human 5-HT3A gene profoundly impact 5-HT3 receptor function and expression. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 17, 255–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hansen K. B., Bräuner-Osborne H. (2009) Xenopus oocyte electrophysiology in GPCR drug discovery. Methods Mol. Biol. 552, 343–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tumkosit P., Kuryatov A., Luo J., Lindstrom J. (2006) β3 subunits promote expression and nicotine-induced up-regulation of human nicotinic α6* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in transfected cell lines. Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 1358–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Harpsøe K., Hald H., Timmermann D. B., Jensen M. L., Dyhring T., Nielsen E. Ø., Peters D., Balle T., Gajhede M., Kastrup J. S., Ahring P. K. (2013) Molecular determinants of subtype-selective efficacies of cytisine and the novel compound NS3861 at heteromeric nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 2559–2570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chavez-Noriega L. E., Crona J. H., Washburn M. S., Urrutia A., Elliott K. J., Johnson E. C. (1997) Pharmacological characterization of recombinant human neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors hα2β2, hα2β4, hα3β2, hα3β4, hα4β2, hα4β4 and hα7 expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 280, 346–356 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gerzanich V., Wang F., Kuryatov A., Lindstrom J. (1998) α5 subunit alters desensitization, pharmacology, Ca++ permeability and Ca++ modulation of human neuronal α3 nicotinic receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 286, 311–320 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mihalak K. B., Carroll F. I., Luetje C. W. (2006) Varenicline is a partial agonist at α4β2 and a full agonist at α7 neuronal nicotinic receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 801–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rollema H., Chambers L. K., Coe J. W., Glowa J., Hurst R. S., Lebel L. A., Lu Y., Mansbach R. S., Mather R. J., Rovetti C. C., Sands S. B., Schaeffer E., Schulz D. W., Tingley F. D., 3rd, Williams K. E. (2007) Pharmacological profile of the α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist varenicline, an effective smoking cessation aid. Neuropharmacology 52, 985–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xiao Y., Fan H., Musachio J. L., Wei Z. L., Chellappan S. K., Kozikowski A. P., Kellar K. J. (2006) Sazetidine-A, a novel ligand that desensitizes α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors without activating them. Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 1454–1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zwart R., Carbone A. L., Moroni M., Bermudez I., Mogg A. J., Folly E. A., Broad L. M., Williams A. C., Zhang D., Ding C., Heinz B. A., Sher E. (2008) Sazetidine-A is a potent and selective agonist at native and recombinant α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 73, 1838–1843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cachelin A. B., Rust G. (1995) β-subunits co-determine the sensitivity of rat neuronal nicotinic receptors to antagonists. Pflugers Arch. 429, 449–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang J., Xiao Y., Abdrakhmanova G., Wang W., Cleemann L., Kellar K. J., Morad M. (1999) Activation and Ca2+ permeation of stably transfected α3/β4 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 55, 970–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang J. M., Zhang L., Yao Y., Viroonchatapan N., Rothe E., Wang Z. Z. (2002) A transmembrane motif governs the surface trafficking of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nat. Neurosci. 5, 963–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Miyazawa A., Fujiyoshi Y., Unwin N. (2003) Structure and gating mechanism of the acetylcholine receptor pore. Nature 423, 949–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hilf R. J., Dutzler R. (2008) X-ray structure of a prokaryotic pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature 452, 375–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hibbs R. E., Gouaux E. (2011) Principles of activation and permeation in an anion-selective Cys-loop receptor. Nature 474, 54–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kabbani N., Woll M. P., Levenson R., Lindstrom J. M., Changeux J. P. (2007) Intracellular complexes of the β2 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in brain identified by proteomics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 20570–20575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Williams B. M., Temburni M. K., Levey M. S., Bertrand S., Bertrand D., Jacob M. H. (1998) The long internal loop of the α3 subunit targets nAChRs to subdomains within individual synapses on neurons in vivo. Nat Neurosci 1, 557–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rezvani K., Teng Y., Pan Y., Dani J. A., Lindstrom J., García Gras E. A., McIntosh J. M., De Biasi M. (2009) UBXD4, a UBX-containing protein, regulates the cell surface number and stability of α3-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci 29, 6883–6896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jeanclos E. M., Lin L., Treuil M. W., Rao J., DeCoster M. A., Anand R. (2001) The chaperone protein 14-3-3η interacts with the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α4 subunit. Evidence for a dynamic role in subunit stabilization. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 28281–28290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kelley S. P., Dunlop J. I., Kirkness E. F., Lambert J. J., Peters J. A. (2003) A cytoplasmic region determines single-channel conductance in 5-HT3 receptors. Nature 424, 321–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tsetlin V., Kuzmin D., Kasheverov I. (2011) Assembly of nicotinic and other Cys-loop receptors. J. Neurochem. 116, 734–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Peters J. A., Cooper M. A., Carland J. E., Livesey M. R., Hales T. G., Lambert J. J. (2010) Novel structural determinants of single channel conductance and ion selectivity in 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Physiol. 588, 587–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Krzywkowski K., Davies P. A., Feinberg-Zadek P. L., Bräuner-Osbourne H., Jensen A. A. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 722–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]