Background: Anti-polysialic acid monoclonal antibody mAb735 preferentially binds longer polysialic acid chains.

Results: Crystal structure of the single chain Fv fragment was determined in complex with octasialic acid.

Conclusion: Two linked units of three consecutive sialic acid residues interact with two antibody fragments in extended conformation.

Significance: An immunological strategy for preference of longer polysialic acid polymers is revealed conflicting with the conformational epitope hypothesis.

Keywords: Antibodies, Crystal Structure, Oligosaccharide, Sialic Acid, Site-directed Mutagenesis

Abstract

Polysialic acid is a linear homopolymer of α2–8-linked sialic acids attached mainly onto glycoproteins. Cell surface polysialic acid plays roles in cell adhesion and differentiation events in a manner that is often dependent on the degree of polymerization (DP). Anti-oligo/polysialic acid antibodies have DP-dependent antigenic specificity, and such antibodies are widely utilized in biological studies for detecting and distinguishing between different oligo/polysialic acids. A murine monoclonal antibody mAb735 has a unique preference for longer polymers of polysialic acid (DP >10), yet the mechanism of recognition at the atomic level remains unclear. Here, we report the crystal structure of mAb735 single chain variable fragment (scFv735) in complex with octasialic acid at 1.8 Å resolution. In the asymmetric unit, two scFv735 molecules associate with one octasialic acid. In both complexes of the unit, all the complementarity-determining regions except for L3 interact with three consecutive sialic acid residues out of the eight. A striking feature of the complex is that 11 ordered water molecules bridge the gap between antibody and ligand, whereas the direct antibody-ligand interaction is less extensive. The dihedral angles of the trisialic acid unit directly interacting with scFv735 are not uniform, indicating that mAb735 does not strictly favor the previously proposed helical conformation. Importantly, both reducing and nonreducing ends of the bound ligand are completely exposed to solvent. We suggest that mAb735 gains its apparent high affinity for a longer polysialic acid chain by recognizing every three sialic acid units in a paired manner.

Introduction

Polysialic acid is a long homopolymer chain of α2–8-linked sialic acids with a degree of polymerization (DP)3 ranging from 8 to 400 (1, 2). Polysialic acid was discovered as an abundant carbohydrate component in the developing mammalian brain (3). Polysialic acid is found mainly on the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) and possesses an enormous hydrated volume that serves to modulate the distance between cells (4). Deletion of polysialic acid causes severe neuronal development defects (5). Polysialic acid is also known to have major functions in the development, morphogenesis, and function of various neural systems. In addition, polysialic acid occurs on several immune cells such as dendritic cells (6, 7), and in some stages of T cell development (8, 9). In these examples, the polysialic acid in α2–8 linkage is attached to specific proteins, such as neuropilins, modulating cellular interactions. Expression of polysialic acid coincides with the loss of pluripotency when embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells differentiate down their several lineage pathways (10). Polysialic acid with α2–8, α2–9, and α2–8/2–9 linkages is also located in the capsule of pathogenic bacteria, including strains of Neisseria meningitidis group B and group C and Escherichia coli K92, respectively (11), enabling them to escape immunological surveillance (12).

The functions of the polysialic acids on glycolipids and glycoproteins are likely closely related to their three-dimensional structure; however, the conformations of polysialic acid remain a debatable issue. Flexible helical structures were suggested by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analyses with the aid of molecular modeling and dynamics calculations. Two groups independently reported helical structures, but the pitches of the proposed helices are significantly different (13, 14). More recently, another helical structure was suggested based on trisialic acid analysis using high field NMR with molecular dynamics simulations (15). But in contrast, an NMR relaxation analysis suggests that polysialic acid is random coil and does not assume a helical structure at all (16).

A series of antibodies that recognize the α2–8-linked polysialic acid epitope have been developed (2). These antibodies often have DP-dependent antigenic specificity, and such unique antibodies are used in biological studies for detecting and distinguishing polysialic acids. Furthermore, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (17) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) (18) bind to polysialic acid in a DP-dependent manner, in need of DP ≥12 and DP ≥17, respectively. It is possible that the oligo/polysialic acid bound to the corresponding specific antibody or partner proteins assumes a conformation existing in solution. This idea comes from the fact that most carbohydrates and polysaccharides bind lectins or antibodies in stable or metastable conformations (19). Accordingly, we recently analyzed the binding epitopes and conformations of the oligosialic acids bound to anti-oligosialic acid antibodies, A2B5 (20) and 12E3 (21), by NMR (22).

Murine monoclonal antibody mAb735 is specific for α2–8-linked polysialic acid and is the subject of this study. The antibody was originally isolated from spleen cells from an autoimmune NZB mouse immunized with N. meningitidis group B and E. coli K1 (23–25). Anti-polysialic acid antibodies, including mAb735, often require a long segment of sialic acid for binding, and the affinity appears to increase with increasing chain length, which led to a conformational epitope hypothesis, in which longer polysialic acid gives rise to a particular helical conformation (26). A crystal structure of an unliganded Fab fragment of mAb735 was reported previously (26), and a subsequent docking model with an extended helical α2–8-linked polysialic acid proposed that a positively charged shallow groove formed by complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) could accept an extended helical conformation of polysialic acid. It is therefore believed that mAb735 is a conformation-specific antibody for “helical” polysialic acids. However, direct structural evidence has not been reported yet.

To clarify the specific recognition mechanism for longer polysialic acid, we here determined the crystal structure of a single chain variable fragment of mAb735 (scFv735) in complex with α2–8-linked octasialic acid. The crystal structure reveals that scFv735 recognizes three consecutive sialic acid residues. The conformation of the trisialic acid is different from the helical conformation proposed previously. This antibody apparently prefers to bind longer polysialic acid by interacting with any three consecutive sialic acid residues with the flat binding surface.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of Octasialic Acid

Mild acid hydrolysates of colominic acid were separated on a Jasco HPLC system equipped with a Mono Q HR5/5 anion-exchange column. Samples were loaded on the column and eluted with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), followed by a NaCl gradient (0–20 min, 0 m; 20–60 min, 0–0.3 m; 60–100 min, 0.3–0.45 m; 100–110 min, 0.45–1 m, and 110–120 min, 1 m) in 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min, and fractions were monitored with a UV detector (UV, Jasco Corp., Japan) at a wavelength of 210 nm. α2–8-Linked octasialic acid fractions were pooled and desalted on a Sephadex G-25 column.

Protein Expression and Purification

A DNA fragment encoding VL and VH domains of mAb735 (murine IgG2a), including linker peptide (Gly4, Ser1)3 was chemically synthesized by Eurofins MWG Operon (Huntsville, AL). The PCR product was amplified and cloned into the BamHI/XbaI site of pCold-TEV vector that had been modified to include a tobacco etch virus protease cleavage sequence between the hexahistidine and Strep-tag (WSHPQFEK) and single chain variable fragment. Expression plasmid was transformed in the E. coli strain BL21 (DE3). The transformed cells were grown in LB medium at 310 K and induced with 0.5 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd.) for 16 h at 288 K. The harvested cells were suspended in PBS (8 mm Na2HPO4, 1 mm KH2PO4, 137 mm NaCl, and 3 mm KCl (pH 7.4)), including Bugbuster (Novagen), and then sonicated. After centrifugation, inclusion bodies were washed three times with PBS. The resultant protein was solubilized in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mm NaCl, and 8 m urea at a protein concentration of 5 mg/ml. Solubilized protein was diluted into 2 liters of buffer containing 200 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.4 m l-arginine, 5 mm reduced glutathione, and 0.5 mm oxidized glutathione. The mixture was equilibrated at 277 K for 16 h with slow stirring and then concentrated to a volume of 200 ml by the Quixstand Benchtop system (GE Healthcare). The concentrated protein solution was extensively dialyzed against 2 liters of PBS at 277 K. The dialyzed protein was applied onto a Ni-NTA column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with PBS containing 500 mm imidazole. The eluted protein was treated with tobacco etch virus protease for 16 h at 277 K to remove the hexahistidine tag. The digest was applied to a Ni-NTA column again. The protein that passed through the Ni-NTA column was collected and dialyzed against 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mm NaCl. The dialyzed protein was concentrated up to 10 mg/ml by Amicon Ultra (molecular weight cutoff of 10,000). The purified protein was mixed with octasialic acid at the concentration of 2 mm and then subjected to crystallization trials. A series of alanine-substituted mutants (Asn-35, Tyr-37, Tyr-39, Arg-55, Tyr-159, Tyr-160, Tyr-179, Asp-232, Lys-228, and Tyr-233) were generated by PCR-based mutagenesis. The correct folding of wild type protein and each mutant was confirmed by the thermal assay described below.

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Structure Determination

All crystals were obtained by the sitting drop vapor diffusion method using 0.8-μl drops containing a 50:50 (v/v) mixture of protein and reservoir solution at 293 K. The crystallization conditions were found from screening using Index (Hampton Research). The crystals in complex with octasialic acid were obtained under the condition of 1.8 m ammonium citrate tribasic (pH 7.0) (Index 21). X-ray diffraction data sets for the crystals were collected at the synchrotron radiation source at BL17A in the Photon Factory (Tsukuba, Japan). All data sets were processed and scaled using HKL2000 program suite (27). Initial phase determination was performed by the molecular replacement method using the program MOLREP (28) with the structure of mAb735 Fab fragment (PDB code 1PLG) as a template. Further model building was performed manually using the program COOT (29). Refinement was carried out using the program REFMAC5 (30). The stereochemical quality of the final models was assessed by MolProbity (31). Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1. All figures were prepared with PyMOL (DeLano Scientific LLC). The structural superposition was performed with SUPERPOSE (32). Dihedral angles of glycosidic linkages were calculated with CARP (33).

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection statistics | |

| Crystal ID | scFv + Sia8 |

| Space group | P64 |

| Cell constant | a = b = 161.2, c = 45.9 Å |

| Resolution | 100 to 1.80 Å (1.83 to 1.80 Å) |

| Rsyma | 9.2% (41.5%) |

| Completenessa | 99.9% (100%) |

| Redundancya | 11.2 (11.2) |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Resolution | 100 to 1.80 Å |

| R | 23.4% |

| Rfree | 25.9% |

| Root mean square deviations from ideal values | |

| Bond length | 0.007 Å |

| Bond angle | 1.251° |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Favored | 96.5% |

| Outliers | 0.0% |

a Values in parentheses are the highest resolution shells.

Estimation of Melting Temperature by Fluorescence-based Thermal Stability Assay

Melting temperature of the protein was estimated as described in Ericsson et al. (34) with a slight modification. The sample solution contained 1 mg/ml protein and 1000-fold diluted SYPRO Orange (Molecular Probes) as the reporter dye in PBS (pH 7.4). The wavelengths for excitation and emission were 475–500 and 520–550 nm, respectively. The samples were heated in a real time PCR instrument (Piko Real24, Thermo Scientific) from 293 to 368 K with increments of 0.5 K/s.

Size Exclusion Chromatography

scFv735 (20 μg) was applied onto a Superdex75 10/300 GL (GE Healthcare) with or without premixing of 400 μg of polysialic acid (Sigma). The size exclusion column was equilibrated with PBS at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. RNase A (14.3 kDa) and ovalbumin (43 kDa) were used as molecular weight standard proteins.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

Ligand binding experiments of scFv735 were conducted on an iTC200 instrument (GE Healthcare) at 298 K. Oligosialic acids (DP3, DP4, DP5, and DP6) were purchased from Nakalai Tesque, Inc. In a typical ITC experiment, the cell was filled with 200 μl of 100 μm protein solution dissolved in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 50 mm NaCl. The protein sample was titrated with successive injections (2 μl) of oligosialic acid solution (10 mm) or polysialic acid solution (300 μm) in the same buffer. Reference experiments were performed by injecting ligand solution into the buffer. The experimental data were fitted using the software Origin 7.0 (OriginLab).

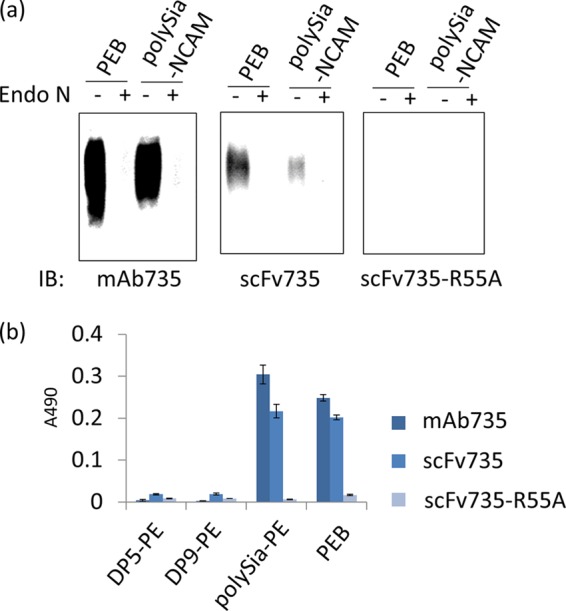

Western Blotting

Pig embryonic brain homogenate (35) or polysialylated NCAM (36) was treated with or without endo-N-acylneuraminidase (Endo N) (37) at 310 K for 20 h and then applied on SDS-PAGE. After blotting to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (38), the membrane was incubated with mAb735 (0.3 μg/ml) or scFv735 (0.13 μg/ml) at 310 K for 2 h. After washing, peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse (IgG + IgM) (0.2 μg/ml) (American Qulex, San Clemente, CA) was applied at 310 K for 1 h and detected by ECL system (GE Healthcare).

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The solid phase ELISA was performed as described previously (21). Briefly, phosphatidylethanolamine dipalmitoyl (PE)-modified DP5 (PE-DP5) (2.5 nmol/well), PE-DP9 (2.5 nmol/well), PE-polysialic acid (2.5 nmol/well), and pig embryonic brain homogenate (5 μg/well as protein) were immobilized on each well and then incubated with mAb735 (0.33 μg/ml) or scFv735 (3.3 μg/ml). The binding was detected by peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse (IgG + IgM) (0.2 μg/ml), and o-phenylenediamine was used as a substrate.

RESULTS

Preparation of Single Chain Variable Fragment of mAb735 (scFv735)

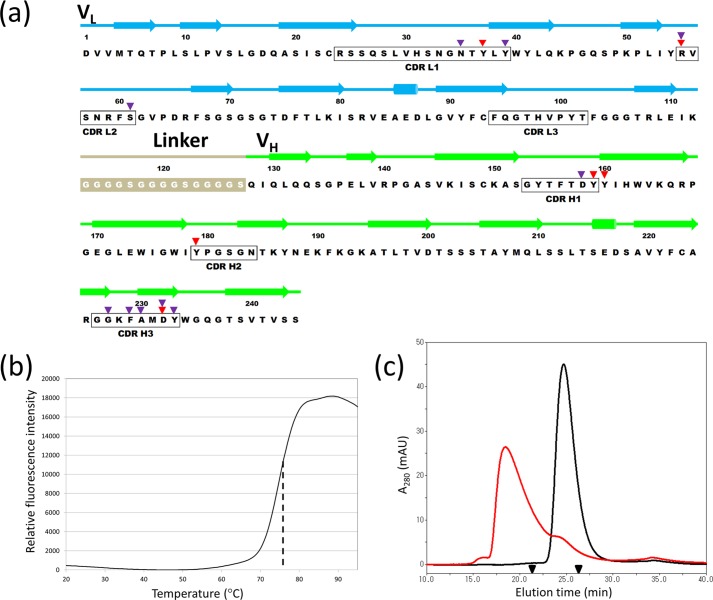

We designed a single chain variable fragment of mAb735, designated as scFv735 hereafter, by introducing a (Gly4-Ser)3 linker between the C terminus of the variable light chain domain (VL) and the N terminus of the variable heavy chain domain (VH) (Fig. 1a). The scFv735 was expressed as inclusion bodies in E. coli cells. The protein in the inclusion bodies was refolded and then purified by affinity chromatography. To check whether purified scFv735 is folded correctly, a thermal stability assay was performed using SYPRO Orange as the reporter fluorescent dye. The melting temperature (Tm), which is defined as the midpoint temperature of the protein-unfolding transition, was estimated to be 77 °C from the thermal denaturation curve (Fig. 1b). We confirmed the binding capability of scFv735 to polysialic acid by size exclusion chromatography. scFv735 alone eluted at 25 min, which indicates the monomeric form of this protein (25 kDa). The co-injection of α2–8 polysialic acid (Mr 24,000–38,000, DP = 80–130) with scFv735 induced a change in the elution time to 18 min (Fig. 1c), indicating the formation of a scFv735-polysialic acid complex. From the elution time, it is estimated that one scFv735 binds one polysialic acid chain in the presence of excess polysialic acid. From these observations taken together, we conclude that refolded and purified scFv735 is folded correctly and is functionally active.

FIGURE 1.

a, amino acid sequence of the anti-polysialic acid scFv of mAb735 (scFv735). Above the sequence, the VL and VH domains, as well as the 15-residue peptide linker (Gly4-Ser)3 that connects VL and VH domains, are colored cyan, green, and gray, respectively. Secondary structural elements of scFv735 are depicted with arrows (β-strands) and cylinders (α-helices). The CDR regions of scFv735 are indicated with black boxes, and red and purple triangles above the sequence mark the residues that make direct and water-mediated indirect interactions with antigen. b, melting curve of scFv735 in PBS (pH 7.4). Relative fluorescence is shown as a black solid line. The midpoint corresponding Tm value is indicated as a dotted line. c, size exclusion chromatography of scFv735 in the absence (black line) and presence of polysialic acid (red line). The retention time of standard proteins (RNase A, 14.3 kDa, 27.3 min; ovalbumin, 44 kDa, 21.5 min) are indicated with triangles.

Overall Structure of scFv735

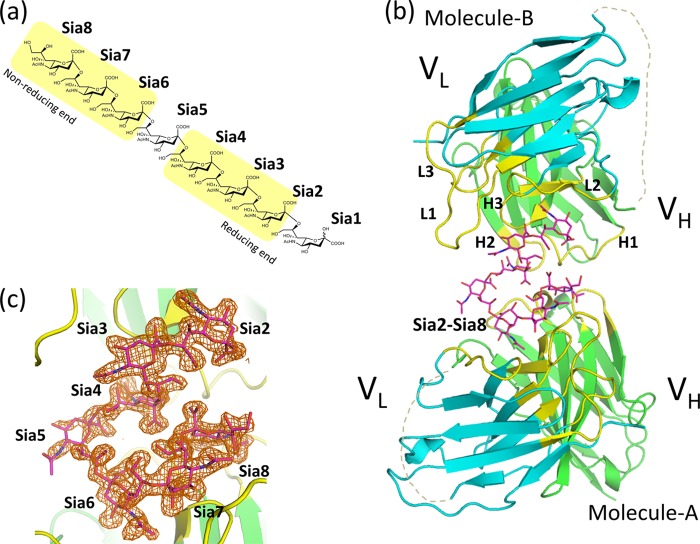

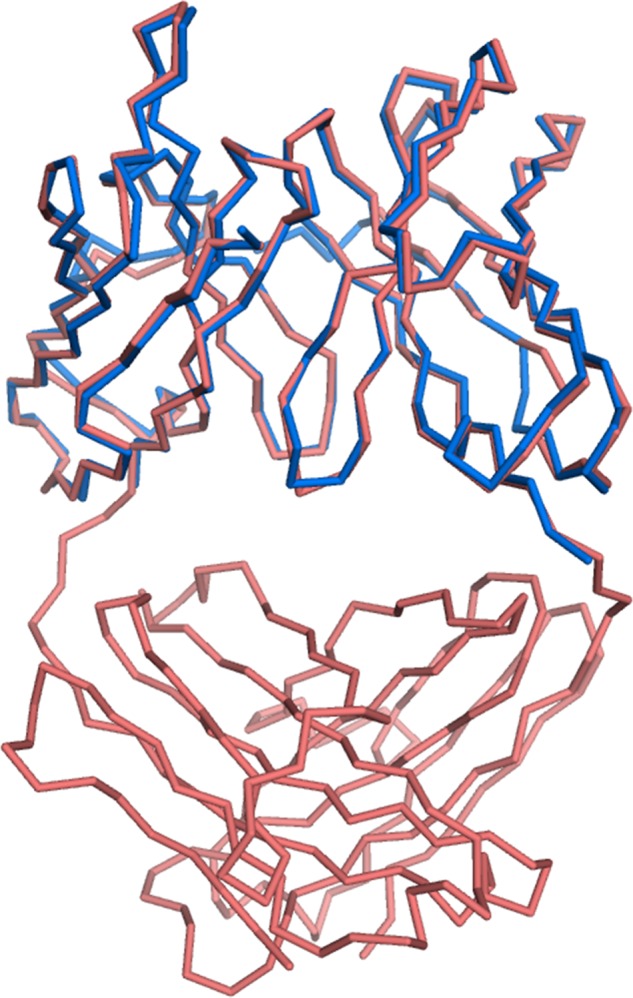

For crystallographic analysis, we prepared octasialic acid by mild acid hydrolysis of polysialic acid (Fig. 2a) and mixed it with scFv735. A 1:5 molar ratio mixture of scFv735 and octasialic acid was used for crystallization. After screening, crystals belonging to space group P64 were obtained and diffracted up to 1.8 Å resolution. The asymmetric unit contains two scFv735 molecules and one carbohydrate chain (Fig. 2b). We designated the two protein molecules in the asymmetric unit as molecules A and B for clarity. The final model of each scFv735 molecule includes residues 1–110 of VL and residues 128–244 of VH. The polypeptide linker regions were completely missing in the two protein molecules (Figs. 1a and 2b). The VL and VH domains of the scFv735 exhibit the typical fold of the variable domains of an immunoglobulin. Each domain contains two antiparallel β-sheets arranged in a β-sandwich fold. The antigen-binding site is formed by six CDR loops corresponding to six hypervariable sequence regions designated as L1, L2 and L3 and H1, H2, and H3 (Figs. 1a and 2b). The two scFv735 molecules are conformationally identical at the backbone level. The root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) value of 224 eq Cα atoms is only 0.4 Å. Structural comparison between antigen-unbound Fab fragment of mAb735 (PDB code 1PLG) and antigen-bound scFv735 showed the protein structures to be essentially identical, with an r.m.s.d. value of 0.6 Å for corresponding 224 Cα atoms (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 2.

Crystal structure of scFv735 in complex with oligosialic acid. a, representative chemical structure of α2–8-linked octasialic acid. The sialic acid residues that interact with two scFv735 molecules are highlighted in yellow. b, overall structure of scFv in complex with trisialic acid. Protein and carbohydrate molecules are shown as ribbon and rod models, respectively. The VL and VH domains are colored cyan and green. Carbohydrate residues are shown as a magenta rod model. Six CDRs are shown in yellow and labeled. The disordered linker regions that connect VL and VH are shown as gray dotted lines. c, omit map for heptasialic acid contoured at 2.5σ level is shown as orange mesh. The orientation is the same as b.

FIGURE 3.

Structural superposition of scFv735 (blue) and Fab fragment of mAb735 (PDB code 1PLG, red). Protein molecules are shown as wire models.

The antigen-binding sites formed by the CDRs of these two molecules face each other. Despite a 5-fold excess of ligand, two scFv735 molecules unexpectedly interact with six of the sialic acid residues of a single octasialic acid molecule in the crystal. Electron density corresponding to seven sialic acid residues was observed. The terminal sialic acid residue at the reducing end is in an α-configuration, contrasting with the predominantly β-anomeric form of sialic acid in solution (24, 25). Because no crystal contacts were found around this residue, it is evidently in a nonreducing form and assigned as Sia2. One scFv735 molecule (molecule B) interacts with Sia2–Sia4, and the other (molecule A) interacts with Sia6–Sia8 as shown in Fig. 2, a and b. The electron density maps corresponding to the three consecutive sialic acid residues (Sia2–Sia4 associated with molecule B and Sia6–Sia8 with molecule A) are clear whereas that of Sia5 is weak (Fig. 2c). Sia5 does not directly contact scFv735, and its average temperature factor is relatively high (36 Å2) compared with the total average of all carbohydrate residues (26 Å2). The chain of seven residues (Sia2–Sia8) is tightly folded in a hairpin structure between the two scFv735 molecules.

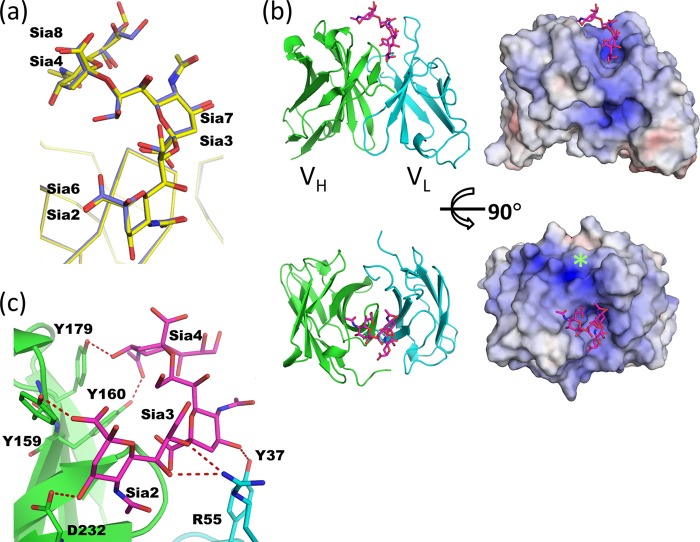

Direct and Water-mediated Carbohydrate Recognition by scFv735

A three consecutive sialic acid segment (Sia2–4 in molecule B and Sia6–8 in molecule A) is in direct contact with the antibody, burying 406 Å2 on average (412 Å2 in molecule A and 400 Å2 in molecule B) of an otherwise solvent-accessible surface area. The positions of the residues in the two trisialic acid units superimpose well (r.m.s.d. = 0.3 Å for all atoms) (Fig. 4a). Electrostatic surface representation reveals that the antigen-binding site is a large, positively charged cleft (Fig. 4b), with the patch of Lys-186 and Lys-228 of CDR H3 defining the periphery of the nonreducing end of the trisialic acids. The protein interacts extensively with Sia2 (Sia6) and Sia4 (Sia8) via all of the CDRs except L3. Intriguingly, direct interaction is mainly through the hydroxyl groups of four tyrosine residues (Tyr-37, Tyr-159, Tyr-160, and Tyr-179) (Fig. 4c). The Oϵ atom of Tyr-159 of CDR H1 makes a hydrogen bond with the carboxyl oxygen of Sia2. The hydroxyl groups of Tyr-160 (CDR H1) and Tyr-179 (CDR H2) interact with OH4 and the N-acetyl oxygen of Sia4. Oϵ of Tyr-37 (CDR L1) bonds with OH4 of Sia3. In addition to these interactions, two polar residues directly interact with the hydroxyl groups of the sialic acids. Oδ2 of Asp-232 (CDR H3) hydrogen bonds with OH4 of Sia2 and Nϵ2 of Arg-55 (CDR L2) with both OH7 and OH8 of Sia2.

FIGURE 4.

Recognition of trisialic acid by scFv735. a, superposition of two scFv735-trisialic acid complexes in the asymmetric unit. Molecule A-Sia2–Sia4 complex and molecule B-Sia6–Sia8 complex are shown in yellow and blue, respectively. Carbohydrate residues are shown as a rod model. b, ribbon model (left) and electrostatic surface representation (right) of scFv735-trisialic acid complex. Carbohydrate residues are shown as a rod model. Positive (blue) and negative (red) potentials are mapped on the van der Waals surfaces in the range −10 kBT (red) to +10 kBT (blue), where kB is Boltzmann's constant, and T is the absolute temperature. Positively charged patch formed by Lys-186 and Lys-228 is indicated by a green asterisk. c, close-up view of antigen recognition site. The side chains of amino acid and carbohydrate residues are shown as rod models. Hydrogen bonds are shown as red dashed lines.

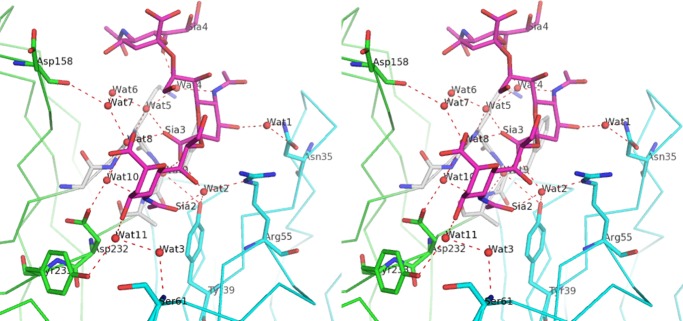

In addition to direct interactions, stabilization is achieved through a water-mediated hydrogen bonded network. Eleven structured water molecules are located in the space between protein and ligand (Fig. 5). The positions of these water molecules are the same in the two complexes in the asymmetric unit, indicating their importance in ligand recognition. Furthermore, the average temperature factor of these 11 water molecules (20 Å2) is lower than those of the carbohydrate residues (26 Å2) as summarized in Table 2. This value is also lower than that of the amino acid residues of the protein molecules, A (23 Å2) and B (30 Å2). Six water molecules (Wat1, -2, -5, and -9–11) directly link trisialic acid residues to protein, although the remaining five (Wat3, -4, and -6–8) participate in the hydrogen bonded network. All CDRs except for L3 participate in water-mediated interactions. CDR H3 (Gly-226–Tyr-233) plays an especially important role. Three water molecules (Wat5, -9, and -10) make hydrogen bonds with backbone amides of Gly-226–Ala-230. The side chains of Arg-55 and Asp-232 contribute both direct and indirect interactions with the ligand (Figs. 4c and 5 and Table 2).

FIGURE 5.

Stereographic display of water-mediated antigen recognition. Carbohydrate and amino acid residues that involve water interactions are shown as rod models. Water molecules are shown as red spheres. Hydrogen bond network is shown as red dashed lines. A summary of the interactions is described in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Water-mediated hydrogen bond network at the scFv735-trisialic acid interface

Temperature factors of water molecules are the averaged values of two complex units in the asymmetric unit.

| Water molecule | B factor | scFv735 residue (atom) | Trisialic acid residue (atom) | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Å2 | Å | |||

| Wat1 | 27 | Asn-35 (Nδ2) | 3.3 | |

| Asn-35 (Oδ2) | 3.2 | |||

| Sia6 (OH6) | 2.7 | |||

| Wat2 | 21 | Tyr-39 (Oη) | 2.7 | |

| Arg-55 (Nϵ) | 2.9 | |||

| Sia5 (O1) | 2.8 | |||

| Sia6 (O1B) | 2.7 | |||

| Wat3 | 22 | Ser-61 (N) | 2.8 | |

| Wat11 | 2.8 | |||

| Wat4 | 19 | Wat5 | 2.9 | |

| Sia6 (N5) | 2.9 | |||

| Sia7 (O7) | 2.9 | |||

| Wat5 | 21 | Lys-228 (N) | 2.8 | |

| Wat4 | 2.9 | |||

| Wat6 | 2.7 | |||

| Sia6 (O1A) | 2.8 | |||

| Wat6 | 19 | Wat5 | 2.7 | |

| Wat7 | 2.9 | |||

| Wat7 | 21 | Asp-158 (O) | 3.0 | |

| Wat6 | 2.9 | |||

| Wat8 | 2.7 | |||

| Wat8 | 19 | Wat7 | 2.7 | |

| Wat10 | 2.8 | |||

| Sia6 (O1A) | 2.9 | |||

| Wat9 | 20 | Tyr-39 (Oη) | 3.4 | |

| Phe-229 (N) | 3.0 | |||

| Ala-230 (N) | 3.1 | |||

| Sia6 (O1B) | 2.7 | |||

| Wat10 | 15 | Gly-227 (N) | 3.2 | |

| Asp-232 (Oδ2) | 2.8 | |||

| Wat8 | 2.8 | |||

| Sia5 (N5) | 2.9 | |||

| Wat11 | 19 | Tyr-233 (Oη) | 2.8 | |

| Wat3 | 2.8 | |||

| Sia5 (OH4) | 2.7 |

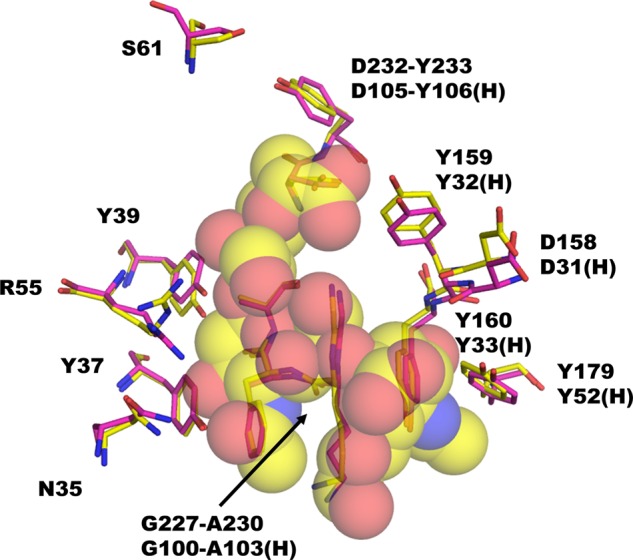

Site-directed Mutagenesis Study

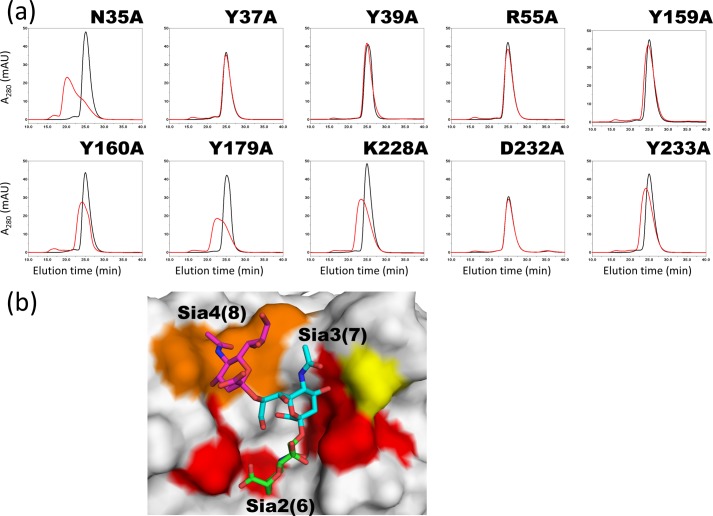

To examine the contribution of each amino acid residue to ligand interaction in solution, we mutated the amino acid residues that directly or indirectly interact with ligand. Amino acid residues Tyr-37, Arg-55, Tyr-159, Tyr-160, Tyr-179, and Asp-232 interact directly. Alanine substitutions of Tyr-37, Arg-55, Tyr-159, and Asp-232 completely abolished ligand binding according to size exclusion chromatography, whereas those of Tyr-160 and Tyr-179 weakened it (Fig. 6a). Mutations to indirect residues Asn-35, Tyr-39, and Tyr-233 revealed that Asn-35 is relatively unimportant; Tyr-39 is essential, and the interaction with Tyr-233 is of intermediate strength. Interestingly, the alanine mutant of Lys-228, which is peripheral to the ligand-binding site, also impaired binding. The mutated residues are mapped on the crystal structure of the scFv735-ligand complex in Fig. 6b, and the proximity of the critical residues located around Sia2 (Sia6) and Sia3 (Sia7) can be seen clearly. The residues interacting with Sia4 (Sia8) seem less important.

FIGURE 6.

Relative importance of binding site amino acid residues studied by site-directed mutagenesis. a, elution profiles from a size exclusion column of mutated scFv735 without (black lines) and with (red lines) polysialic acid. mAU, milli-absorbance unit. b, mapping of the mutated residues in the scFv735-ligand complex structure. The residues whose substitution abolished (Tyr-37, Tyr-39, Arg-55, Tyr-159, and Asp-232) or impaired ligand binding (Tyr-160, Tyr-179, Lys-228, and Tyr-233) are colored in red and orange, respectively. The residue whose substitution did not significantly affect ligand binding (Asn-35) is shown in yellow. The sugar residues are colored in green (Sia2(6)), cyan (Sia3(7), and pink (Sia4(8)), respectively.

Conformation of Heptasialic Acid Bound to scFv735

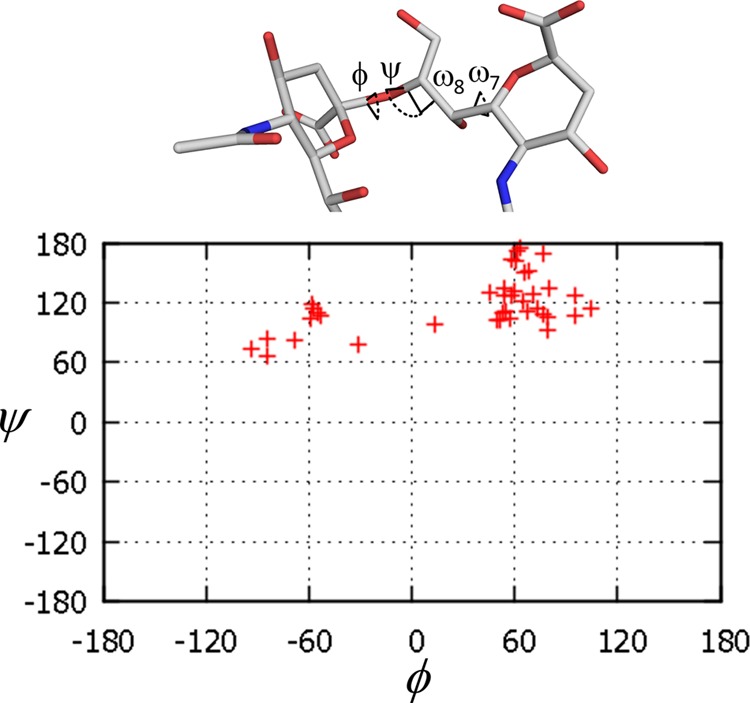

The conformation of polysialic acid has been a subject of much discussion. The dihedral angles (φ, ψ, ω8, and ω7) of the bound heptasialic acid were calculated and are summarized in Table 3. The conformations of the trisialic acids in the two antigen-binding sites are essentially identical. The dihedral angles of a helical conformation reported in a previous docking model study are −45°, 130°, 60°, and 60°, respectively (14). In this structure, however, the dihedral angles of the interacting trisialic acid demonstrate a rather unfolded conformation and differ greatly from those mentioned above for the proposed helical conformation (underlined in Table 3). The φ angles are particularly different.

TABLE 3.

Dihedral angles of the glycosidic linkages in the crystal

The definitions of dihedral angles are as follows: ϕ = O6(+1)-C2(+1)-O2(+1)-C8; ψ = C2(+1)-O2(+1)-C8-C7; ω7 = O6-C6-C7-O7, and ω8 = O7-C7-C8-O8 (Fig. 13). The dihedral angles from the trisialic unit in the antigen binding sites are underlined.

| Dihedral angle | Sia2–3 | Sia3–4 | Sia4–5 | Sia5–6 | Sia6–7 | Sia7–8 | Helixa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ϕ | 63 | −58 | 81 | 99 | 64 | −57 | −45 |

| ψ | 112 | 109 | 90 | 155 | 109 | 112 | 130 |

| ω8 | 62 | 55 | 63 | 94 | 69 | 49 | 60 |

| ω7 | 61 | 54 | 67 | 62 | 63 | 51 | 60 |

a Adapted from Ref. 14.

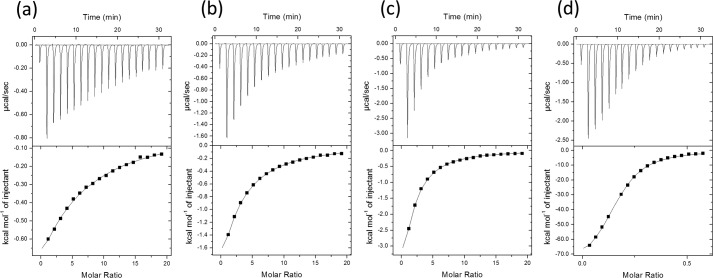

Thermodynamics Study

In the crystal structure, a short trisialic acid unit interacts with scFv735 in a nonhelical manner. To investigate the interaction between scFv735 and short oligosialic acids, we performed isothermal titration calorimetry to determine the dissociation constants and thermodynamic parameters (Fig. 7 and Table 4). The dissociation constants of scFv735 to DP4, DP5, and DP6 were 1.7, 0.65, and 0.30 mm, respectively. For DP3, we could not determine the dissociation constant under the condition we tested, but it is estimated to be larger than 5 mm. The titration experiment also revealed that one polysialic acid (DP = 80∼130) interacts with six scFv735 molecules on average with a dissociation constant of 3.5 μm. These observations suggest that short oligosialic acids weakly interact with scFv735 in solution. A DP-dependent affinity increase might be explained by the presentation of repeated trisaccharide units to scFv, thereby reducing the off-rate of interaction. Furthermore, thermodynamic parameters for each interaction revealed that a large entropy loss upon interaction (−TΔS = 72.7 kcal/mol for polysialic acid) is compensated for by a larger enthalpy gain (ΔH = −80.1 kcal/mol) (1 kcal = 4.184 kJ).

FIGURE 7.

Isothermal titration calorimetry analysis of scFv735 using DP4 (a), DP5 (b), DP6 (c), and polysialic acid (DP80–130) (d). Dissociation constants and thermodynamic parameters are summarized in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Dissociation constants of scFv735/Fab735/mAb735 and oligo/polysialic acid obtained by isothermal titration calorimetry

| Ligand | Protein | Kd | ΔH | −TΔS | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | kcal/mol | kcal/mol | |||

| DP3 | scFv735 | NDa | ND | ND | This study |

| DP4 | scFv735 | 1.7 × 10−3 | −11.5 | 7.7 | This study |

| DP5 | scFv735 | 6.5 × 10−4 | −12.2 | 7.9 | This study |

| DP6 | scFv735 | 3.0 × 10−4 | −12.6 | 7.8 | This study |

| DP9 | mAb735 | 2.6 × 10−5 | −10.9 | 4.6 | Evans et al. (26) |

| DP11 | mAb735 | 2.1 × 10−5 | −10.2 | 3.8 | Evans et al. (26) |

| DP14 | mAb735 | 1.7 × 10−5 | −9.2 | 2.7 | Evans et al. (26) |

| DP15 | mAb735 | 2.3 × 10−5 | −9.9 | 3.8 | Evans et al. (26) |

| Polysialic acid (DP ∼41) | Fab735 | 4.1 × 10−6 | −12.9 | 5.5 | Evans et al. (26)b |

| Polysialic acid (DP 80–130) | scFv735 | 3.5 × 10−6 | −80.1 | 72.7 | This studyc |

a ND means the dissociation constant could not be determined under the experimental condition we tested but must be larger than 5 mm.

b Kd was calculated assuming one polysialic acid (DP ∼41) chain binds to three Fab735.

c Stoichiometry was experimentally determined to be n = 0.166, where the one polysialic acid chain (DP 80–130) binds to six scFv735 molecules on average.

Comparison between Divalent mAb735 and Monovalent scFv735

The binding between scFv735 and short oligosialic acids is weak compared with typical antigen-antibody interactions. It is likely that the divalent nature of mAb735 contributes to the apparent affinity to polysialic acid in an in vitro assay at least in part. To test this idea, we performed Western blotting and ELISA using divalent mAb735 and monovalent scFv735. In the Western blotting analysis, both mAb735 and scFv735 could detect the polysialic acid in pig embryonic brain homogenate and polysialylated NCAM (Fig. 8a). As expected, monovalent scFv735 detected polysialic acid to a lesser extent compared with divalent mAb735. The scFv735 mutant R55A failed to detect polysialic acid at all, as observed in the size exclusion chromatography experiment (Fig. 6a). ELISA was also performed using PE-modified DP5 (DP5-PE), DP9-PE, polysialic acid-PE, and pig embryonic brain homogenate (Fig. 8b). Binding of mAb to DP5-PE or DP9-PE was not detected, but it was for polysialic acid-PE and pig embryonic brain homogenate, in agreement with a previous report (35). A similar result was obtained for scFv735, although less strongly compared with mAb735. The scFv735-R55A mutant did not bind to any of the ligands. These observations suggest that the bivalent nature of mAb735 binding does indeed contribute to a higher apparent affinity thereby overcoming the inherently weak binding to polysialic acid.

FIGURE 8.

Biochemical assays using divalent mAb735 and monovalent scFv735. a, Western blot analysis of pig embryonic brain homogenate (PEB) and polysialylated NCAM (polySia-NCAM) using mAb735 (0.3 μg/ml), scFv735 (0.13 μg/ml), and scFv735-R55A (0.13 μg/ml). Endo N-treated samples were also analyzed for control experiment. b, ELISA analysis of DP5-PE, DP9-PE, polysialic acid-PE (polySia-PE), and pig embryonic brain homogenate using mAb735 (0.33 μg/ml), scFv735 (3.3 μg/ml), and scFv735-R55A (3.3 μg/ml).

DISCUSSION

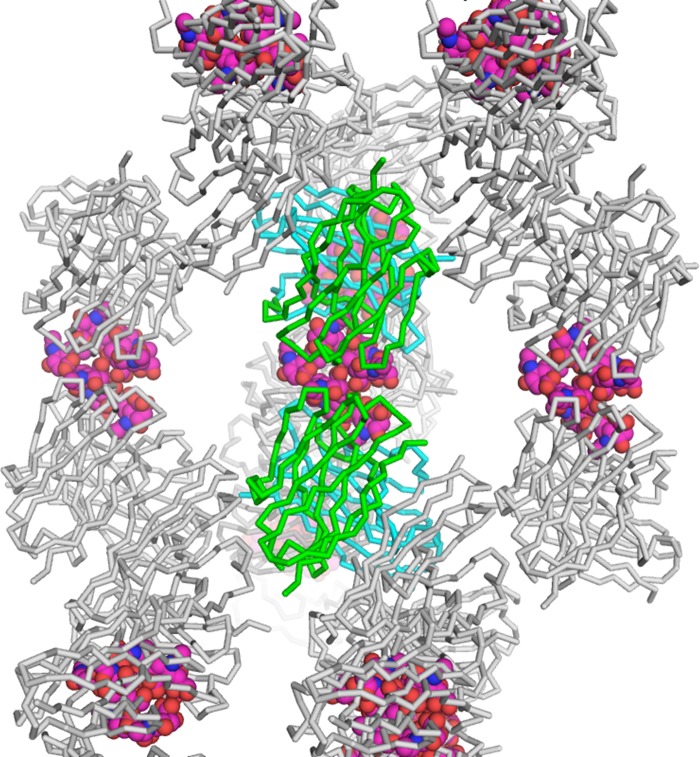

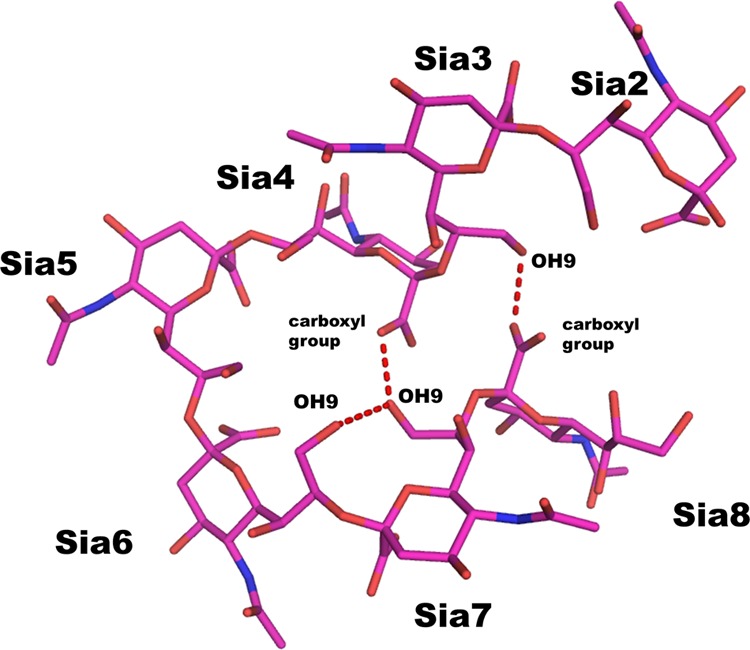

We have elucidated the crystal structure of anti-polysialic acid antibody mAb735 complexed with an oligosialic acid and revealed its unique antigen recognition mechanism. We initially attempted to crystallize scFv735 in complex with tetrasialic acid but failed to obtain diffraction quality crystals. We had success with octasialic acid, but, surprisingly, even though there was a 5-fold molar excess of ligand, two scFv735 proteins were found bound to one sialic acid chain in the crystal. There is only one interaction between the two scFv735 molecules in the asymmetric unit. The side chain of Asp-158 of one molecule hydrogen bonds with that of Tyr-179 of the other. The two scFv735s are arranged on opposite sides of the octasialic acid ligand, each interacting with a sugar triplet. The heptasialic acid portion for which there is electron density is compactly folded, stabilized through hydrogen bonds between sialic acid residues (Fig. 9), and fixes the relative orientation of the two scFvs. The intersugar interactions highlight the role of the sugar chain in anchoring the two scFv735 molecules and in facilitating subsequent crystallization (Fig. 10).

FIGURE 9.

Hydrogen bonding interactions observed within heptasialic acid. Heptasialic acid (Sia2–Sia8) is shown as a rod model. Intersugar hydrogen bonds are indicated by red dashed lines.

FIGURE 10.

Crystal packing of scFv735-octasialic acid complex. Protein molecules and carbohydrate moieties are shown as wire and sphere models, respectively. The VH and VL domains in the asymmetric unit are shown in green and cyan, respectively.

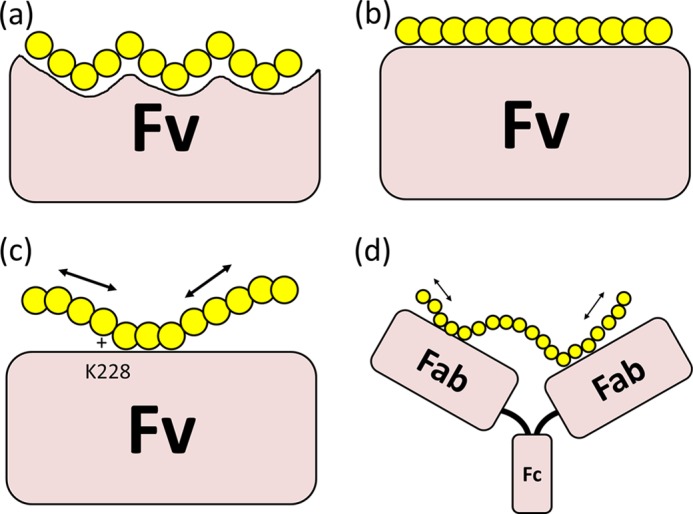

Why does mAb735 prefer longer polysialic acids? The mechanism of DP-dependent antigen recognition has been obscure for a long time. It has been proposed, based on a model of polysialic acid docked in an mAb735 Fab fragment, that longer polymers form helical segments that fit into a crevice formed by the CDR loop regions (Fig. 11a) (26). Another possibility is that the binding site is lengthy, and there is interaction with an unfolded long sugar chain segment (Fig. 11b). However, the crystal structure reveals that a single scFv735 recognizes only three sequential sialic acid residues, in a rather extended conformation (Fig. 11c). A classical helical structure or long segment is not involved. The reducing and nonreducing ends of the octasialic acid are exposed to the solvent, indicating that the antibodies recognize internal residues of polysialic acids. Furthermore, the crystal structure has two opposing Fv molecules interacting in an identical paired binding mode with a single carbohydrate-carbohydrate cross-linked sialic acid chain. We propose that the binding preference for longer sialic acid chains may come about initially by a single antibody fragment (Fab) binding weakly to any sequential three sialic acids in the chain, and the subsequent similar binding of the other Fab fragment in the same antibody molecule in proximity to the first, together with looping of the chain, causes stronger binding. We call this the avidity hypothesis (Fig. 11d). This idea is supported the Western blotting and ELISAs (Fig. 8), in which divalent mAb735 binds polysialic acid more efficiently than monovalent scFv735. We estimate that two Fab units in the same antibody could bind to two independent three sialic acid unit sections on one ∼30 sialic acid unit stretch of polysialic acid, based on the result that one polysialic acid chain (DP ∼100) can bind six scFv735 molecules (Table 4). It also suggests that any trisialic unit in a long chain, irrespective of its position, could be a target for the antibody, and this fits with the wide and flat accommodating ligand-binding site. The affinity toward a homopolymer may also be enhanced simply by the presentation of multiple proximal antibody-binding sites on the polymer, which could slow the dissociation of antibody. In fact, apparent affinity enhancement of scFv735 is observed in a DP-dependent fashion (Table 4), supporting this idea.

FIGURE 11.

Models of the interactions that prefer longer polysialic acid. a, conformational epitope hypothesis. Longer polysialic acid assumes a helix that is specifically recognized by the Fv. b, long epitope hypothesis. Fv recognizes more than 10 sugar residues in an extended nonhelical conformation. c, multiple epitope hypothesis. Fv recognizes a short epitope unit, but multiple nearby epitopes are presented by the polysialic acid, which reduces the off-rate of Fv or even enables the sliding of Fv on the polymer. d, avidity hypothesis. Single antibody fragment (Fab) recognizes a short sugar unit weakly, but the complex gains affinity through interaction with the other Fab fragment of the same antibody-sialic acid complex. c and d, the arrows indicate the movement (shifting or sliding) of the polysialic acid on the antibody.

Undoubtedly, the main contributor to the high ligand affinity and recognition is the extensive direct and indirect hydrogen bond interactions between the sialic acid triplet and protein. Six amino acid residues are involved in direct hydrogen bonds. Two residues in the VL region (Tyr-37 and Arg-55) and two residues in the VH region (Tyr-159 and Asp-232) are critical for antigen recognition (Figs. 4c and 6). Tyr-160 and Tyr-179 are less important. Water-mediated interactions are extensive and likely crucial for antigen recognition (Fig. 5). About half of the water-mediated hydrogen bonds are formed between backbone atoms and trisialic acid residues (Table 2). Both Arg-55 and Asp-232 participate in direct and indirect interactions with the ligand. Three amino acid residues, Asn-35, Tyr-39, and Tyr-233, contribute indirect interactions. Among them, Tyr-39 binds two sialic acid residues via two water molecules and plays a crucial role in ligand binding (Table 2 and Fig. 6). Lys-228 located at the adjoining binding site also plays a role (Figs. 4b and 6a) and perhaps it functions as a transient acceptor for the incoming polysialic acid.

The contribution of water-mediated hydrogen bonds in the binding of lectins to their ligands has been discussed for more than a decade. Peanut lectin prefers T-antigen (Galβ1–3GalNAc) to lactose (Galβ1–4Glc). The 20-fold difference in affinity is attributed to the presence of two water molecules that make hydrogen bonds with the protein and the N-acetyl group of the T-antigen (39, 40). In the case of family 15 and 29 carbohydrate-binding modules (CBM15 and -29), the removal of amino acid residues engaging in water-mediated interactions with ligands had comparatively little effect on carbohydrate binding (41, 42). In our scFv735-ligand structure, water-mediated interactions are extensive and intrinsic to recognition. The role of water-mediated interactions appears different for different lectins, and each should be considered independently.

We recently analyzed the binding modes of two anti-oligosialic acid IgMs, A2B5 and 12E3, by saturation transfer difference NMR and transferred NOE (22). A2B5 favors a trisialic acid unit over others, although 12E3 shows a binding preference for more than five successive sialic acid residues. A2B5 predominantly interacts with sialic acid residues at the nonreducing end, whereas 12E3 binds internal sialic acid residues through C4–C8 moieties and N-acetyl groups. scFv735, which has a binding preference for polysialic acid chains with DP >10 (35), is similar to 12E3 in that it also likely binds internal residues and directly interacts with OH4, OH7, OH8, a carboxyl group, and the N-acetyl oxygen atoms (Fig. 4c). Interestingly, scFv735 interacts with all OH4 groups of the triplet, whereas 12E3 primarily interacts with N-acetyl groups of three sequential sialic acid residues.

Our finding that the interaction between antibody and ligand involves a network of hydrogen bonds fits well with the thermodynamics studies that indicate the binding is enthalpy-driven with some opposition from an unfavorable entropy (Table 4) (26). Structural comparison of ligand-free and -bound scFv735 shows that the protein does not change conformation on ligand binding (Fig. 12), indicating that the negative entropic factor likely originates from the loss of rotational and/or translational entropies of the ligand.

FIGURE 12.

Comparison between structures of mAb735 Fab fragment (PDB code 1PLG, magenta) and scFv735-trisialic acid complex (yellow). The amino acid residues that are involved in direct or water-mediated antigen binding are shown as rod models. The trisialic acid residues are shown as semi-transparent sphere models.

The geometry of α2–8-linked sialic acid residues in crystal structures has not been analyzed in detail, which contrasts with the extensive discussion of such structures in solution. The website Glycoscience.de (33) offers ways to search for carbohydrate structures in the PDB. About 40 α2–8 glycosidic linkages between two sialic acid residues are deposited in the PDB. We have extracted all the available dihedral angles (φ and ψ) of the linkages and plotted them in Fig. 13. The φ angle exhibits a marked preference for angles −60° and 60°, whereas ψ prefers ∼120°. Three sialic acid residues in the antigen-binding sites of our crystal structure show typical φ and ψ angles, whereas the dihedral angles of Sia4–Sia5 and Sia5–Sia6 are atypical (φ = 81° and 99°, and ψ = 90° and 155°, respectively (Table 3)). It suggests that longer oligosialic acids are conformationally flexible or else restrained by the crystallographic packing.

FIGURE 13.

Dihedral angles of α2–8 glycosidic linkages between two sialic acid residues. The data were extracted from the PDB, and the dihedral angles φ and ψ were plotted using glycoscience.de on-site tool (33).

In conclusion, the crystal structure of anti-polysialic antibody mAb735 complexed with octasialic acid, in conjunction with a series of mutagenesis analyses, reveals that paired antibody binding and extensive hydrogen bonding interactions could underlie antibody recognition of polysialic acid chains.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staff of the beamlines at Photon Factory (Tsukuba, Japan) for providing data collection facilities and support. We thank Drs. Masato Kikkawa and Seiji Yamamoto (GE Healthcare) for ITC measurements and valuable discussions. We also thank Noriko Tanaka for secretarial assistance.

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (deciphering sugar chain-based signals regulating integrative neuronal functions) 24110506 and 24110520 (to M. N. and C. S.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) AB821355.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3WBD) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- DP

- degree of polymerization

- CDR

- complementarity-determining region

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- scFv

- single chain variable fragment

- PE

- phosphatidylethanolamine

- NCAM

- neural cell adhesion molecule

- Endo N

- endo-N-acylneuraminidase

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nakata D., Troy F. A., 2nd (2005) Degree of polymerization (DP) of polysialic acid (polySia) on neural cell adhesion molecules (N-CAMS): development and application of a new strategy to accurately determine the DP of polySia chains on N-CAMS. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38305–38316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sato C., Kitajima K. (2013) Disialic, oligosialic, and polysialic acids: distribution, functions and related disease. J. Biochem. 154, 115–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Finne J. (1982) Occurrence of unique polysialosyl carbohydrate units in glycoproteins of developing brain. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 11966–11970 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rutishauser U. (2008) Polysialic acid in the plasticity of the developing and adult vertebrate nervous system. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 26–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weinhold B., Seidenfaden R., Röckle I., Mühlenhoff M., Schertzinger F., Conzelmann S., Marth J. D., Gerardy-Schahn R., Hildebrandt H. (2005) Genetic ablation of polysialic acid causes severe neurodevelopmental defects rescued by deletion of the neural cell adhesion molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42971–42977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bax M., van Vliet S. J., Litjens M., García-Vallejo J. J., van Kooyk Y. (2009) Interaction of polysialic acid with CCL21 regulates the migratory capacity of human dendritic cells. PLoS One 4, e6987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rey-Gallardo A., Delgado-Martín C., Gerardy-Schahn R., Rodríguez-Fernández J. L., Vega M. A. (2011) Polysialic acid is required for neuropilin-2a/b-mediated control of CCL21-driven chemotaxis of mature dendritic cells and for their migration in vivo. Glycobiology 21, 655–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Drake P. M., Nathan J. K., Stock C. M., Chang P. V., Muench M. O., Nakata D., Reader J. R., Gip P., Golden K. P., Weinhold B., Gerardy-Schahn R., Troy F. A., 2nd, Bertozzi C. R. (2008) Polysialic acid, a glycan with highly restricted expression, is found on human and murine leukocytes and modulates immune responses. J. Immunol. 181, 6850–6858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Drake P. M., Stock C. M., Nathan J. K., Gip P., Golden K. P., Weinhold B., Gerardy-Schahn R., Bertozzi C. R. (2009) Polysialic acid governs T-cell development by regulating progenitor access to the thymus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 11995–12000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nairn A. V., Aoki K., dela Rosa M., Porterfield M., Lim J. M., Kulik M., Pierce J. M., Wells L., Dalton S., Tiemeyer M., Moremen K. W. (2012) Regulation of glycan structures in murine embryonic stem cells: combined transcript profiling of glycan-related genes and glycan structural analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 37835–37856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Finne J., Leinonen M., Mäkelä P. H. (1983) Antigenic similarities between brain components and bacteria causing meningitis. Implications for vaccine development and pathogenesis. Lancet 2, 355–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jódar L., Feavers I. M., Salisbury D., Granoff D. M. (2002) Development of vaccines against meningococcal disease. Lancet 359, 1499–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yamasaki R., Bacon B. (1991) Three-dimensional structural analysis of the group B polysaccharide of Neisseria meningitidis 6275 by two-dimensional NMR: the polysaccharide is suggested to exist in helical conformations in solution. Biochemistry 30, 851–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brisson J. R., Baumann H., Imberty A., Pérez S., Jennings H. J. (1992) Helical epitope of the group B meningococcal α(2–8)-linked sialic acid polysaccharide. Biochemistry 31, 4996–5004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yongye A. B., Gonzalez-Outeiriño J., Glushka J., Schultheis V., Woods R. J. (2008) The conformational properties of methyl α-(2,8)-di/trisialosides and their N-acyl analogues: implications for anti-Neisseria meningitidis B vaccine design. Biochemistry 47, 12493–12514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Henderson T. J., Venable R. M., Egan W. (2003) Conformational flexibility of the group B meningococcal polysaccharide in solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 2930–2939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kanato Y., Ono S., Kitajima K., Sato C. (2009) Complex formation of a brain-derived neurotrophic factor and glycosaminoglycans. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 73, 2735–2741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ono S., Hane M., Kitajima K., Sato C. (2012) Novel regulation of fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2)-mediated cell growth by polysialic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 3710–3722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Imberty A. (1997) Oligosaccharide structures: theory versus experiment. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7, 617–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Inoko E., Nishiura Y., Tanaka H., Takahashi T., Furukawa K., Kitajima K., Sato C. (2010) Developmental stage-dependent expression of an α2,8-trisialic acid unit on glycoproteins in mouse brain. Glycobiology 20, 916–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sato C., Kitajima K., Inoue S., Seki T., Troy F. A., 2nd, Inoue Y. (1995) Characterization of the antigenic specificity of four different anti-(α2→8-linked polysialic acid) antibodies using lipid-conjugated oligo/polysialic acids. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 18923–18928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hanashima S., Sato C., Tanaka H., Takahashi T., Kitajima K., Yamaguchi Y. (2013) NMR study into the mechanism of recognition of the degree of polymerization by oligo/polysialic acid antibodies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 21, 6069–6076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frosch M., Görgen I., Boulnois G. J., Timmis K. N., Bitter-Suermann D. (1985) NZB mouse system for production of monoclonal antibodies to weak bacterial antigens: isolation of an IgG antibody to the polysaccharide capsules of Escherichia coli K1 and group B meningococci. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 1194–1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vaesen M., Frosch M., Weisgerber C., Eckart K., Kratzin H., Bitter-Suermann D., Hilschmann N. (1991) Primary structure of the murine monoclonal IgG2a antibody mAb735 against α(2–8) polysialic acid. 1) Amino-acid sequence of the light (L-) chain, κ-isotype. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 372, 451–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klebert S., Kratzin H. D., Zimmermann B., Vaesen M., Frosch M., Weisgerber C., Bitter-Suermann D., Hilschmann N. (1993) Primary structure of the murine monoclonal IgG2a antibody mAb735 against α(2–8) polysialic acid. 2. Amino acid sequence of the heavy (H-) chain Fd′ region. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 374, 993–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Evans S. V., Sigurskjold B. W., Jennings H. J., Brisson J. R., To R., Tse W. C., Altman E., Frosch M., Weisgerber C., Kratzin H. D. (1995) Evidence for the extended helical nature of polysaccharide epitopes. The 2.8 Å resolution structure and thermodynamics of ligand binding of an antigen binding fragment specific for α-(2→8)-polysialic acid. Biochemistry 34, 6737–6744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vagin A., Teplyakov A. (2010) Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 22–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) COOT: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lovell S. C., Davis I. W., Arendall W. B., 3rd, de Bakker P. I., Word J. M., Prisant M. G., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2003) Structure validation by Cα geometry: φ,ψ and Cβ deviation. Proteins 50, 437–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krissinel E., Henrick K. (2004) Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2256–2268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lütteke T., Bohne-Lang A., Loss A., Goetz T., Frank M., von der Lieth C. W. (2006) GLYCOSCIENCES.de: an Internet portal to support glycomics and glycobiology research. Glycobiology 16, 71R–81R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ericsson U. B., Hallberg B. M., Detitta G. T., Dekker N., Nordlund P. (2006) Thermofluor-based high-throughput stability optimization of proteins for structural studies. Anal. Biochem. 357, 289–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sato C., Fukuoka H., Ohta K., Matsuda T., Koshino R., Kobayashi K., Troy F. A., 2nd, Kitajima K. (2000) Frequent occurrence of pre-existing α2→8-linked disialic and oligosialic acids with chain lengths up to 7 Sia residues in mammalian brain glycoproteins. Prevalence revealed by highly sensitive chemical methods and anti-di-, oligo-, and poly-Sia antibodies specific for defined chain lengths. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 15422–15431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hane M., Sumida M., Kitajima K., Sato C. (2012) Structural and functional impairments of polysialic acid (polySia)-neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) synthesized by a mutated polysialyltransferase of a schizophrenic patient. Pure Appl. Chem. 84, 1895–1906 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hallenbeck P. C., Vimr E. R., Yu F., Bassler B., Troy F. A. (1987) Purification and properties of a bacteriophage-induced endo-N-acetylneuraminidase specific for poly-α-2,8-sialosyl carbohydrate units. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 3553–3561 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sato C., Kitajima K., Inoue S., Inoue Y. (1998) Identification of oligo-N-glycolylneuraminic acid residues in mammal-derived glycoproteins by a newly developed immunochemical reagent and biochemical methods. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 2575–2582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ravishankar R., Ravindran M., Suguna K., Surolia A., Vijayan M. (1997) Crystal structure of the peanut lectin-T-antigen complex. Carbohydrate specificity generated by water bridges. Curr. Sci. India 72, 855–861 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ravishankar R., Suguna K., Surolia A., Vijayan M. (1999) Structures of the complexes of peanut lectin with methyl-β-galactose and N-acetyllactosamine and a comparative study of carbohydrate binding in Gal/GalNAc-specific legume lectins. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55, 1375–1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pell G., Williamson M. P., Walters C., Du H., Gilbert H. J., Bolam D. N. (2003) Importance of hydrophobic and polar residues in ligand binding in the family 15 carbohydrate-binding module from Cellvibrio japonicus Xyn10C. Biochemistry 42, 9316–9323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Flint J., Bolam D. N., Nurizzo D., Taylor E. J., Williamson M. P., Walters C., Davies G. J., Gilbert H. J. (2005) Probing the mechanism of ligand recognition in family 29 carbohydrate-binding modules. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 23718–23726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]