Abstract

Objective

Social withdrawal is described as the condition in which an individual experiences a desire to make social contact, but is unable to satisfy that desire. It is an important issue for patients with motor neurone disease who are likely to experience severe physical impairment. This study aims to reassess the psychometric and scaling properties of the MND Social Withdrawal Scale (MND-SWS) domains and examine the feasibility of a summary scale, by applying scale data to the Rasch model.

Methods

The MND Social Withdrawal Scale was administered to 298 patients with a diagnosis of MND, alongside the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. The factor structure of the MND Social Withdrawal Scale was assessed using confirmatory factor analysis. Model fit, category threshold analysis, differential item functioning (DIF), dimensionality and local dependency were evaluated.

Results

Factor analysis confirmed the suitability of the four-factor solution suggested by the original authors. Mokken scale analysis suggested the removal of item five. Rasch analysis removed a further three items; from the Community (one item) and Emotional (two items) withdrawal subscales. Following item reduction, each scale exhibited excellent fit to the Rasch model.

A 14-item Summary scale was shown to fit the Rasch model after subtesting the items into three subtests corresponding to the Community, Family and Emotional subscales, indicating that items from these three subscales could be summed together to create a total measure for social withdrawal.

Conclusion

Removal of four items from the Social Withdrawal Scale led to a four factor solution with a 14-item hierarchical Summary scale that were all unidimensional, free for DIF and well fitted to the Rasch model. The scale is reliable and allows clinicians and researchers to measure social withdrawal in MND along a unidimensional construct.

Keywords: Social withdrawal, Rasch analysis, Psychological distress, ALS, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, MND, Motor neurone disease

1. Introduction

Motor neurone disease (MND) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease of unknown aetiology that is characterised by weakness in limb and bulbar muscles, culminating in respiratory failure and death. No curative treatments exist for the disease. Progression is often rapid and may present a serious challenge for patients with MND who need to cope not only with a terminal diagnosis but also with the intense demands of a potentially steep decline in physical function.

There is a growing body of literature which demonstrates, perhaps paradoxically, that quality of life in MND is only weakly related to impairments in physical function that define the disease [1–4]. The psychological consequences of the illness and their relationship to patient quality of life have been increasingly examined over recent years and findings have shown strong relationships between social support, depression, coping, fatigue and patient quality of life [4–8].

Social withdrawal has not only been described as the condition in which an individual experiences a desire to make social contact, but is unable to satisfy that desire [9], but may also be described as a conscious desire for reduced social interaction due to increased anxiety or embarrassment [10,11]. It is a factor associated with poor quality of life for patients with other neurological illnesses, such as Parkinson's disease (PD) [12] and multiple sclerosis (MS) [13].

People with MND often experience social withdrawal from family, friends and events occurring outside the home. Patients commonly report that they are less socially attached following diagnosis, including fewer visits from friends and church attendances and may describe visits to their doctor or MND clinic as their most common form of social interaction [11]. Low levels of social interaction are related to increased levels of psychological distress in MND patients. Conversely, high levels of social support are related to increased quality of life in MND [2]. Recent calls have been made to develop psychological therapies specifically for MND patients and their carers [14,15] and, given its relationship with quality of life and depression, social withdrawal may make a point of departure for future interventions.

A disease-specific measure has been designed to assess social withdrawal from the perspective of the MND patient across four domains measuring withdrawal across domains of Community, Family, Emotional and Physical Withdrawal [16]. The original scale consists of 24 items scored along a four point Likert-type response ranging from Strongly Disagree (scored 0) to Strongly Agree (scored 3). Items were derived from semi-structured interviews carried out with MND patients. Consistent with the patient-led rationale of the original study, domains were conceptually based on the manner in which interviewed MND patients described their experiences of social withdrawal.

The original study found SW, particularly from the community, to be strongly associated with depression and physical symptoms of the disease [16]. Further research using this measure has found SW from family and friends to be associated with reduced quality of life [17]. Other researchers using the MND-SWS Scale have found higher levels of social withdrawal in patients who were struggling to cope with the disease. Those patients found to have difficulty in coping also scored highly for depression and anxiety [18].

The SWS was developed on a relatively small sample of MND patients (N = 23), meaning reduced power in statistical tests [19]; with a potential error rate of up to 30% [20]. In addition to the inherent risks of developing scales on small samples, measures developed using classic test theory (CTT) will always be ordinal, which may affect the accuracy of arithmetic operations and comparison of raw scores [21]. A further caveat of the four disparate factors of the original scale was that no analysis was conducted to confirm that they could also form a single unidimensional construct, allowing estimation of a total score for social withdrawal.

The Rasch model [22] is a modern psychometric approach that permits interval-level measurement from pencil-and-paper questionnaires. Rasch techniques have been shown to successfully reduce the number of items on questionnaires [23], a particularly important issue when developing questionnaires for disabled populations [24].

The impetus of the current study is to assess the psychometric and scaling properties of the MND-SWS from a Rasch measurement perspective and, in doing so, to evaluate the psychometric properties of the four subscales of the MND-SWS, and to provide a unidimensional Summary scale of social withdrawal.

2. Methods

2.1. Main data collection

The psychometric and scaling properties of the MND-SWS were assessed among 298 patients recruited from five regional MND care centres: the Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery in Liverpool, Preston Royal Hospital, Oxford John Radcliffe Hospital, Salford Hope Hospital, and Sheffield Royal Hallamshire Hospital. All participants had a diagnosis of MND from a neurologist with expertise in MND. Patients were unselected for age, sex, and symptom presentation or disability status. The MND-SWS was administered as part of a questionnaire suite that contained a number of psychometric instruments, including the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [25] modified for use with MND patients [26] and the Neurological Fatigue Index-MND [27]. Contemporaneous functional status information was taken for 142 patients using the ALS Functional Rating Scale — Revised (ALSFRS-R) [28] in clinic within a month of either side of questionnaire completion. Questionnaires were either handed out during a routine clinic appointment or sent to the patients' homes over a period of twelve months. Where patients were unable to complete the pack by themselves a nurse or caregiver was allowed to act as a scribe. Each participant gave informed consent.

Ethical permission was granted for this study from relevant hospital committees in the U.K. (Sefton 05/Q0401/7 and Tayside 07/S1402/64), and local research governance committees at all participating sites.

2.2. Statistical analysis

An initial exploration of the factor structure of the existing scale was undertaken with a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) based upon the four domain structure. The purpose here is to provide confirmation of the structure so as to include the extant domains within the Rasch analysis. Consequently a ‘weak’ confirmation is used with an associated fit statistic (RMSEA of < 0.10) as indicative of a minimum confirmed structure. The CFA factors will be rotated using oblique Geomin rotation with weighted least squares mean- and variance-adjusted estimation. Should the CFA fail, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) would be undertaken. More rigorous post-hoc tests of unidimensionality will be undertaken within the Rasch analysis (detailed below). Prior to this, a non-parametric probabilistic (Mokken) model will be used to screen the domain items for a probabilistic structure that would be consistent with the Rasch model [29]. A Loevinger's coefficient value of < 0.3 would indicate an item not consistent with this structure [30].

To evaluate the scaling properties and construct validity of the MND-SWS, the Rasch measurement model was used [22]. Rasch analysis ensures that the fundamental scaling properties of an instrument are assessed alongside traditional psychometric assessments of reliability. The model operationalises the formal axioms of measurement (order, unidimensionality and additivity) [31]. Unlike classical approaches, it allows the creation of interval level measurement from questionnaire measures given certain criteria [32]. A sample size of 243 will provide accurate estimates of item and person locations irrespective of scale targeting [33].

Analyses used to assess whether the scale conforms to Rasch model expectations are briefly explained below. A comprehensive review with a more detailed explanation of the Rasch analytical process may be found elsewhere [34]. The unconditional ‘partial credit’ polytomous Rasch model was used with conditional pair-wise parameter estimation [35].

Rasch model fit is primarily indicated by a non-significant deviation from model expectations across a range of fit statistics. For example, the summary chi-square statistic should be non-significant, after adjusting for multiple testing. In addition, both person fit and item fit are assessed by their residual mean values. This examines the differences between the observed data and model expectations for each person and each item estimate. At the summary level, perfect fit is represented by a mean of zero and a standard deviation (SD) of ± 1, whilst at the individual level for persons and items, a residual value of ± 2.5 is appropriate.

Reliability for Rasch scales is described as the extent to which items distinguish between distinct levels of functioning and is shown statistically using the Person Separation Index (PSI) (where 0.7 is considered a minimal value for research use; 0.85 for clinical use) [36]. Where the distribution is normal the PSI is equivalent to Cronbach's alpha.

Scale unidimensionality is assessed using a post-hoc comparison of two independent estimates, which are subjected to a t-test. These estimates are derived from the loadings on the first principal component analysis of the residuals, and the latent estimate of each person (and its standard error) calculated independently for each test. These estimates are then compared and the number of significant t-tests outside the ± 1.96 range indicates whether the scale is unidimensional or not. Generally, where less than 5% of the t-tests are significant this is indicative of a unidimensional scale (or the lower bound of the 95% binomial confidence interval is below 5%) [37].

Rasch analysis permits the evaluation of important psychometric criteria, including local dependency, category threshold disordering and differential item functioning (DIF). Local dependency occurs when two questions on a scale are too similar, leading to artificially inflated reliability. Item category threshold disordering occurs where patients cannot reliably distinguish between response categories (i.e. points on a Likert scale). Differential item functioning occurs when different demographic groups within the sample respond in a different way to a certain question. In the present study DIF was assessed by age, sex and functional ability. Further details of Rasch analysis are comprehensively provided elsewhere [26,34].

For the analysis of DIF by functional impairment, scores on the ALSFRS-R were categorised into three groups representing patients in the lower, middle and upper tertiles within the sample. These groups represented ALSFRS-R scores of 29 or less (n = 48), 30 to 38 (n = 58) and 39 to 45 (n = 36).

When necessary, items are removed one at a time. Once an item is removed the resultant scale is reassessed for fit, dimensionality, local dependency and DIF. This iterative process is repeated until an acceptable solution is found. This process has been used in previous Rasch studies [26,38].

The CFA was undertaken with MPlus [39], Rasch analysis with RUMM2030 [40], and the Mokken scaling with STATA [41].

3. Results

3.1. Patient sample

Summary demographic information and questionnaire response by centre are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and questionnaire response by centre.

| Demographics | N = 298 | n(%), M ± SD (range) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 62.09 ± 11.01 | |

| Sex | 62.4% male | |

| Questionnaires completed at home | 278 (93.3%) | |

| Disease duration (years) | 2.69 ± 3.54 | |

| ALSFRS-R score | 32.6 (12–48) | |

| Patients recruited from each research centre | Liverpool | 110 (36.9%) |

| Sheffield | 38 (12.8%) | |

| Oxford | 39 (13.1%) | |

| Salford | 76 (25.5%) | |

| Preston | 35 (11.7%) |

3.2. Confirmatory factor analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) confirmed the suitability of the four-factor structure suggested by the original authors. The original solution displayed acceptable initial dimensionality (RMSEA = 0.09) [42] before more rigorous tests of dimensionality are conducted within Rasch analysis [37]. Mokken scale analysis of the four-factor structure suggested the removal of item 5 ‘No longer use telephone’ from the ‘Community Withdrawal’ factor.

3.3. Rasch analysis

Each subscale was tested separately using the Rasch model to assess unidimensionality and fit to the Rasch model. All items apart from item 5 from the original scale were taken into Rasch analysis.

3.4. Community Withdrawal subscale

The 5-item Community Withdrawal subscale displayed initial misfit to the Rasch model (see Table 2, Community Initial). Analysis of item fit residuals revealed that item 4 ‘Still participate in everything’ was misfitting the Rasch model (χ2 = 19.39 [4], p < 0.01). Scale fit was improved following the removal of item 4; including acceptable targeting, dimensionality and reliability (see Table 2, Community Final). The modified Community Withdrawal subscale has ordered category thresholds, has no local dependency and is free from DIF by age, gender or functional impairment.

Table 2.

Summary fit statistics for the Social Withdrawal Scale.

| Analysis name |

# of items | Item residual |

Person residual |

Chi square |

PSI | Unidimensional test (CI %) | Extreme scores (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | ± SD | Mean | ± SD | Value | p | |||||

| Community: Initial | 5 | 0.88 | 2.45 | − 0.36 | 1.26 | 106.51 | < 0.001 | 0.78 | 3.61% (1.70–6.50) | 7.00% |

| Community: Final | 4 | 0.72 | 0.81 | − 0.44 | 1.11 | 22.7 | 0.12 | 0.76 | 0.78% (0.10–2.80) | 14.42% |

| Family: Final | 6 | 0.3 | 1.18 | − 0.39 | 1.22 | 34.39 | 0.08 | 0.67 | 4.79% (2.60–7.90) | 2.01% |

| Emotional: Initial | 6 | 0.2 | 3.38 | − 0.52 | 1.5 | 160.53 | < 0.001 | 0.78 | 6.94% (4.30–10.5) | 3.36% |

| Emotional: Final | 4 | 0.14 | 1.08 | − 0.91 | 1.84 | 17.4 | 0.36 | 0.75 | 3.90% (1.96–6.87) | 5.37% |

| Physical: Final | 6 | − 0.05 | 1.67 | − 0.34 | 1.03 | 37.9 | 0.04 | 0.91 | 4.15% (2.00–6.90) | 19.13% |

| Summary: Initial | 20 | 0.24 | 2.12 | − 0.38 | 1.67 | 196.08 | < 0.001 | 0.82 | 17.91% (16.10–26.60) | 0.67% |

| Summary: Final | 14a | 0.4 | 1.22 | − 0.37 | 1.51 | 4.52 | 0.97 | 0.65 | 0.72% (0–3.3) | 0.68% |

| Ideal values | 0 | < 1.4 | 0 | < 1.4 | > 0.01 | > 0.85 | < 5% (CI < 0.05) | < 10% | ||

Key: SD — standard deviation, p — probability, PSI — Person Separation Index, CI — confidence interval.

Items collapsed into 3 subtests representing the Community, Family and Emotional subscales.

3.5. Family Withdrawal subscale

The 6-item Family Withdrawal subscale displayed excellent summary fit to the Rasch model and did not require any modification. Item 9 ‘Enjoy the company of friends’ did display misfit to the Rasch model (χ2 = 13.7 [4], p = 0.01) but overall scale fit was not improved by removal of this item so it was retained. Item category thresholds were correctly ordered. Summary fit statistics are given for the final subscale in Table 2. Items were locally independent and no DIF by age, gender or functional impairment.

3.6. Emotional Withdrawal

The Emotional Withdrawal subscale did not display good fit to the Rasch model (see Table 2, Emotional Initial). Item 14 ‘Want to go and do things’ displayed high residual fit and poor fit to the Rasch model (Fit residual = 6.56; χ2 = 93.2 [4], p < 0.001) and was removed from the scale. Thresholds were correctly ordered and did not require any restructuring. Reanalysis of the revised Emotional Withdrawal subscale revealed that item 17 ‘Embarrassed in public places’ also displayed misfit to the Rasch model (χ2 = 13.32 [4] p < 0.05). Upon the removal of items 14 and 17, the Emotional Withdrawal scale displayed excellent fit to the Rasch model, including unidimensionality, ordered category thresholds, absence of DIF by age, gender or functional impairment, no local dependency, good reliability and acceptable scale targeting.

3.7. Physical Withdrawal

The original Physical Withdrawal subscale displayed adequate fit to the Rasch model (p = 0.04). Whilst item 19 ‘Physical condition prevents me from doing what I want to do’ displayed a high positive fit residual, removal of the item did not improve fit to the scale; and so it was retained. The scale demonstrated good dimensionality, local independence of items and ordered category thresholds (see Table 2, Physical: Final). A large ceiling effect was apparent, with 17.91% of respondents scoring the maximum score for the subscale.

The Physical Withdrawal subscale did not display DIF by age, gender or level of functional impairment.

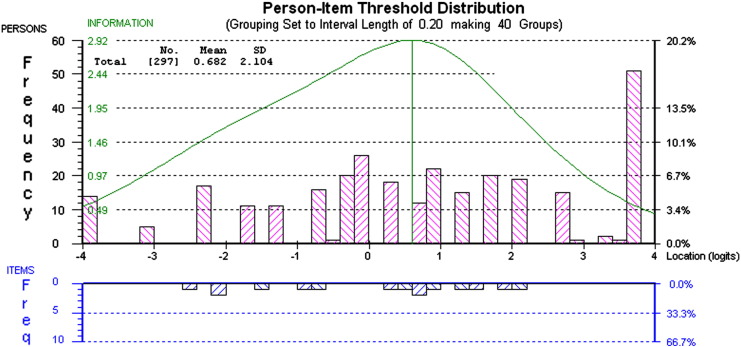

The high ceiling effect present for this subscale is shown in Fig. 1. Bars above the x-axis of the scale represent the person location in logits and bars below the x-axis represent item threshold location in logits. In spite of this ceiling effect, there is a good spread of item difficulty (clusters below the x-axis), ranging from − 2.5 to 2.2 logits.

Fig. 1.

Person–item threshold distribution for Physical subscale. This figure shows the distribution of person and item thresholds (above the x-axis) and item (below the x-axis). A ceiling effect is evident between 2.2 and 3.8 logits.

3.8. Summary scale

In order to assess the potential suitability of the Social Withdrawal Scale as a total measure of withdrawal the 20 items from the four constituent subscales were analysed. Initial analysis of the 20 items showed misfit to the Rasch model that appeared to be driven by multidimensionality within the dataset (see Table 2, Summary: Initial). For the purposes of the analysis, the 20 items were arranged into four subtests, with each subtest consisting of the items from the four subscales. Arranging the items in this manner would allow Rasch analysis to evaluate each subscale as a single item when analysing fit for the Summary scale. Subtesting the items improved fit however uniform DIF was present for the ‘Physical’ subscale (f(2) = 9.53, p < 0.001). Resultantly, the Physical subscale was removed from the Summary scale analysis. Following the removal of these items, the final 14-item Summary scale yielded excellent fit to the Rasch model (see Table 3, Summary Final); including unidimensionality, reliability and absence of DIF or local dependency.

Table 3.

Item fit statistics for the final subscales.

| Item | Location | SE | FitResid. | ChiSq. | Prob. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community subscale | 1 | 0.44 | 0.08 | 1.51 | 8.23 | 0.08 |

| 2 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.80 | 3.26 | 0.51 | |

| 3 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.96 | 2.63 | 0.62 | |

| 6 | − 0.85 | 0.09 | − 0.40 | 8.59 | 0.07 | |

| Family subscale | 7 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.56 | 4.34 | 0.23 |

| 8 | − 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.36 | 2.88 | 0.41 | |

| 9 | 0.93 | 0.11 | − 0.16 | 13.7 | 0.01 | |

| 10 | 0.12 | 0.08 | − 1.59 | 4.32 | 0.23 | |

| 11 | − 0.55 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 2.63 | 0.45 | |

| 12 | − 0.69 | 0.08 | 2.03 | 9.14 | 0.03 | |

| Emotional subscale | 13 | − 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.94 | 4.56 | 0.35 |

| 15 | − 0.07 | 0.10 | − 1.43 | 10.08 | 0.04 | |

| 16 | − 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.31 | 1.05 | 0.90 | |

| 18 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.75 | 1.72 | 0.78 | |

| Physical subscale | 19 | − 1.04 | 0.12 | 2.92 | 13.31 | 0.01 |

| 20 | 0.52 | 0.10 | − 1.39 | 4.91 | 0.30 | |

| 21 | − 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.83 | 1.24 | 0.87 | |

| 22 | 0.51 | 0.10 | − 0.66 | 4.04 | 0.40 | |

| 23 | 0.23 | 0.09 | − 0.58 | 4.00 | .0.41 | |

| 24 | 0.86 | 0.09 | − 1.45 | 10.41 | 0.03 |

Key — SE = Standard Error; FitResid. = Fit Residual; ChiSq. Chi Square; Prob — Probability.

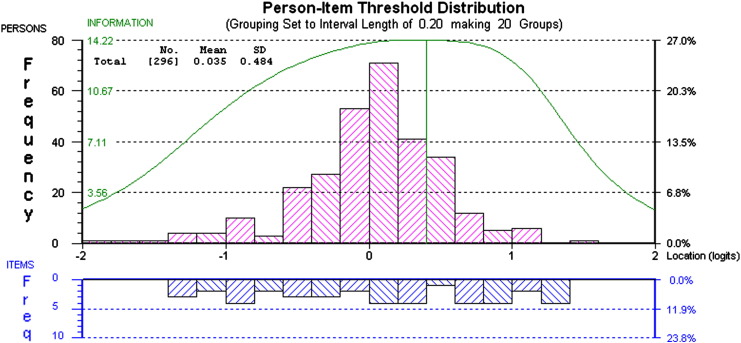

Fig. 2 shows the person–item threshold distribution for the Summary scale. On the Summary scale persons (shown above the x-axis) are normally distributed and the incidence of patients falling at the floor and ceiling is an acceptable 1.68%. Scale information, indicated by large clusters of items beneath the x-axis, appears to be maximised between − 2.5 and 2.8 logits, where the majority of patients fall. Reliability was higher when the Summary scale was analysed without subtests (PSI = 0.82, Cronbach's alpha = 0.81).

Fig. 2.

Person–item threshold distribution for Summary scale. This figure displays the person–item threshold distribution for the Summary scale. The normal distribution of bars above the x-axis that fall within the range of the items (below the x-axis).

Individual item fit statistics for all subscales are displayed in Table 3.

3.9. Raw score to interval scale conversion

Table 4 provides a simple chart for allowing conversion of raw scores taken from each of the four subscales into interval level scores for use in arithmetic operations. These conversions will hold provided there are no missing data. Parametric statistics can then be utilised, given appropriate distributional assumptions.

Table 4.

Conversion table for raw to interval score for Social Withdrawal subscales.

| Raw score | Sum. | Com. | Emo. | Phys. | Fam. | Raw score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31 |

| 1 | 3.82 | 1.53 | 1.37 | 1.51 | 2.09 | 32 |

| 2 | 6.38 | 2.65 | 2.55 | 2.87 | 3.62 | 33 |

| 3 | 8.08 | 3.45 | 3.55 | 4.12 | 4.75 | 34 |

| 4 | 9.40 | 4.13 | 4.5 | 5.27 | 5.68 | 35 |

| 5 | 10.48 | 4.73 | 5.38 | 6.31 | 6.52 | 36 |

| 6 | 11.42 | 5.34 | 6.18 | 7.26 | 7.29 | 37 |

| 7 | 12.26 | 5.96 | 6.93 | 8.12 | 7.98 | 38 |

| 8 | 13.03 | 6.68 | 7.68 | 8.91 | 8.68 | 39 |

| 9 | 13.76 | 7.55 | 8.48 | 9.63 | 9.35 | 40 |

| 10 | 14.44 | 8.65 | 9.39 | 10.29 | 10.02 | 41 |

| 11 | 15.09 | 10.09 | 10.54 | 10.94 | 10.71 | 42 |

| 12 | 15.72 | 12 | 12 | 11.58 | 11.43 | 43 |

| 13 | 16.33 | 12.23 | 12.2 | 44 | ||

| 14 | 16.92 | 12.93 | 13.02 | 45 | ||

| 15 | 17.51 | 13.75 | 13.93 | |||

| 16 | 18.08 | 14.72 | 14.93 | |||

| 17 | 18.64 | 16.08 | 16.28 | |||

| 18 | 19.20 | 18 | 18 | |||

| 19 | 19.75 | |||||

| 20 | 20.31 | |||||

| 21 | 20.87 | |||||

| 22 | 21.43 | |||||

| 23 | 21.99 | |||||

| 24 | 22.56 | |||||

| 25 | 23.13 | |||||

| 26 | 23.71 | |||||

| 27 | 24.30 | |||||

| 28 | 24.91 | |||||

| 29 | 25.52 | |||||

| 30 | 26.15 |

Key: Com. = Community subscale; Emo. = Emotional scale; Phys. = Physical subscale; Sum. = Summary scale.

3.10. Comparison of MND Social Withdrawal Scale with physical functioning, fatigue and psychological distress

Table 5 displays Spearman's correlation coefficients between the MND-SWS subscales and other variables. The 15-item MND-SWS Summary scale is strongly associated with depression (rs = .61, p < 0.05), anxiety (rs = .42, p < 0.05) and fatigue (rs = .40, p < 0.05), but was less strongly related to functional status (rs = − .30, p < 0.05). The Physical Withdrawal scale was strongly correlated with functional status (rs = − .61, p < 0.05), but not to such a degree that they appear to measure exactly the same construct. Raw scores were used in all analyses.

Table 5.

Spearman's correlation coefficients between study variables.

| ALSFRS-R | HADS-D | HADS-A | NFI-MND | SWS Community | SWS Family | SWS Physical | SWS Emotional | SWS Summary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALSFRS | 1 | ||||||||

| HADS-D | 1 | ||||||||

| HADS-A | .54 | 1 | |||||||

| NFI-MND | .46 | .51 | 1 | ||||||

| SWS Community | − .34 | .57 | .46 | 1 | |||||

| SWS Family | .35 | .30 | 1 | ||||||

| SWS Emotional | .41 | .34 | .33 | .38 | 1 | ||||

| SWS Physical | − .61 | .44 | .44 | .61 | .30 | 1 | |||

| SWS Summary | − .30 | .61 | .42 | .40 | .69 | .75 | .73 | .49 | 1 |

Key: ALSFRS = Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale — revised; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale — Depression; D = Depression; A = Anxiety; NFI-MND = Neurological Fatigue Index-Motor Neurone Disease; SWS = Social Withdrawal Scale.

Spearman's rank correlations all significant at p < 0.05. Effect sizes below .3 suppressed.

4. Discussion

Living with motor neurone disease is a potentially devastating experience, which may be worsened if patients become socially withdrawn. In order to facilitate further social withdrawal research, we provide a modified version of the MND-SWS questionnaire that is capable of interval-level measurement of social withdrawal across four domains and a Summary scale.

Research that examines the role of social withdrawal in the determination of psychological distress and quality of life will be well placed to inform the development of novel psychological therapies in this population. In the present study, social withdrawal was shown to be associated with increased levels of depression and anxiety and reduced functional ability. These results are congruent with previous research [16] and suggest that further investigation of social withdrawal may provide important insight into the complex relationship between quality of life and functional status in MND patients.

Social withdrawal has also been shown to affect quality of life in other neurological conditions, including Parkinson's disease [12] and multiple sclerosis [13]. Further work could be undertaken with other neurological patient groups to adapt the MND-SWS Scale for use in these conditions, facilitating better understanding of the processes underlying social withdrawal and allowing comparisons between diseases. Recent calls have been made to develop psychological therapies specifically for MND patients and their carers [14,15].

The original four-factor structure of the MND-SWS was supported by factor and Rasch analysis. Only one item “I no longer use the telephone as much as I used to, prior to MND” was identified by the Mokken scale analysis as being unsuitable and was removed prior to Rasch analysis. A further three items that displayed either poor fit to the Rasch model or high fit residuals were omitted.

A large ceiling effect was apparent for the ‘Physical’ subscale, with 74 patients (19%) scoring beyond the maximum range of this subscale. This suggests that the Physical subscale is primarily useful for measuring Physical Withdrawal in patients who do not experience severe physical impairment. In contrast, the Summary scale, which excluded the items from the Physical Withdrawal subscale, was well targeted, with less than 1% of extreme scores, indicating that the scale is suitable for use with all MND patients, regardless of disease duration or functional impairment.

It should be noted that items 9 and 19 were retained in the ‘Family’ and ‘Physical’ subscales despite displaying high fit residuals. These items were retained as their removal did not improve Rasch model fit, and their inclusion will serve to maximise scale information. Further research should test the suitability of these two items in a separate population.

The Person Separation Index (PSI) value for the Summary scale is sufficient for research use but falls below the recommended threshold for clinical use. Analysis of the person–item threshold distributions suggests that the Summary scale is well targeted. Reliability is likely to be reduced by the process of subtesting due to the local dependency within the subtests, a factor which spuriously inflates reliability if not addressed [43]. The 14-item that make up the Summary scale displayed excellent reliability of .81 when evaluated as individual items (i.e. when not analysed using subtests).

The present study is limited insofar as the MND-SWS was validated statistically and has yet to be completed in its modified form by patients in either research or as part of the clinical assessment process. Such use would confirm the acceptability of the scale and allow the psychometric properties of the scale to be tested outside the development sample. Sample size and budget constraints in the current study precluded the completion of a secondary analysis using a validation sample. Further work is planned to administer the MND-SWS to a large sample of patients with MND, which will allow for validation of the new scale.

The age and sex of our sample are representative of the U.K. research populations from other studies [44,45]. Patients were recruited from MND care centres across the U.K. These centres care for MND patients at all stages of the disease. A wide spread of disability within the current sample was indicated by a large range of ALSFRS-R scores.

The MND-SWS has a hierarchical factor structure, and may be used in a number of ways. We suggest that the 15-item Summary scale is useful for both clinical and research applications. The total score for the Summary scale can be calculated by summing together the score of the constituent items. Greater detail can be gained from the analysis of the four individual subscales, which we consider to be primarily useful for research applications and more in-depth investigations concerning the nature of social withdrawal.

Our findings support the use of the modified 14-item MND Social Withdrawal Scale with MND patients. The new 14-item Summary scale and the four subscales displayed good internal construct validity, excellent unidimensionality and were free from gender or age related item bias.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements and funding

UKMND-QOL Members

Alan Tennant, Statistician, Leeds

Carolyn Young, Principal Investigator, Liverpool

Chris Gibbons, Postdoctoral Researcher, Liverpool

Dave Watling, R&D Manager, Liverpool

Douglas Mitchell, Consultant Neurologist, Preston

Everard Thornton, Consultant Health Psychologist, Liverpool

Hannah Hollinger, Research Nurse, Sheffield

John Ealing, Consultant Neurologist, Manchester

Kevin Talbot, Consultant Neurologist, Manchester

Nicky Pih, MND Nurse, Liverpool

Pam Shaw, Consultant Neurologist, Sheffield

Pauline Callagher, Research Nurse, Preston

Rachael Marsden, Research Nurse, Oxford

Robert Addison-Jones, Research Nurse, Preston

Theresa Walsh, Research Nurse, Sheffield

The Walton Centre Neurological Disability Fund and the Motor Neurone Disease Association U.K. supported this research. We thank the reviewers of this manuscript for their helpful comments. We would particularly like to thank the patients and carers who graciously gave their time to participate in the study.

Professor John Douglas Mitchell also played a key role in the design and conduct of the study but passed away in 2011.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Simmons Z., Bremer B.A., Robbins R.A., Walsh S.M., Fischer S. Quality of life in ALS depends on factors other than strength and physical function. Neurology. 2000;55(3):388–392. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstein L.H., Atkins L., Leigh P.N. Correlates of quality of life in people with motor neuron disease (MND) Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2002;3(3):123–129. doi: 10.1080/146608202760834120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robbins R.A., Simmons Z., Bremer B.A., Walsh S.M., Fischer S. Quality of life in ALS is maintained as physical function declines. Neurology. 2001;56(4):442–444. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.4.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibbons C., Thronton E., Ealing J., Shaw P., Talbot K., Tennant A. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal degeneration. 2013. The impact of fatigue and psychosocial variables on quality of life for patients with motor neuron disease. [Early online:1–9] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hecht M., Hillemacher T., Grasel E., Tigges S., Winterholler M., Heuss D. Subjective experience and coping in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2002;3(4):225–231. doi: 10.1080/146608202760839009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abe K. Fatigue and depression are associated with poor quality of life in ALS. Neurology. 2004;62:1914. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.10.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cupp J., Simmons Z., Berg A., Felgoise S.H., Walsh S.M., Stephens H.E. Psychological health in patients with ALS is maintained as physical function declines. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2011;12(4):290–296. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2011.554555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matuz T., Birbaumer N., Hautzinger M., Kubler A. Coping with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an integrative view. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(8):893–898. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.201285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpentino L. 3rd ed. Lippincott Company; Philadelphia: 1989. Nursing diagnosis application to clinical practice. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hogg K.E., Goldstein L.H., Leigh P.N. The psychological impact of motor neurone disease. Psychol Med. 1994;24(3):625–632. doi: 10.1017/s003329170002777x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDonald E.R. The ALS Patient Profile Project; Seattle: 1992. Psychological aspects of ALS patients and their primary caregivers. [Google Scholar]

- 12.deBoer A., Wijker W., Speelman J.D., deHaes J. Quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease: development of a questionnaire. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;61(1):70–74. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.61.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stenager E., Stenager E.N., Knudsen L., Jensen K. Multiple sclerosis: the impact on family and social life. Acta Psychiatr Belg. 1994;94(3):165–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibbons C.J., Young C.A. Assessing and managing fatigue in motor neuron disease. Neurodegener Dis Manage. 2012;2(4):401–409. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pagnini F., Simmons Z., Corbo M., Molinari E. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: time for research on psychological intervention? Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2012;13(5):416–417. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2011.653572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rigby S.A., Thornton E.W., Tedman S., Burchardt F., Young C.A., Dougan C. Quality of life assessment in MND: development of a Social Withdrawal Scale. J Neurol Sci. 1999;169(1–2):26–34. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chio A., Gauthier A., Montuschi A., Calvo A., Di Vito N., Ghiglione P. A cross sectional study on determinants of quality of life in ALS. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(11):1597–1601. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.033100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hugel H., Pih N., Dougan C.P., Rigby S., Young C.A. Identifying poor adaptation to a new diagnosis of motor neuron disease: a pilot study into the value of an early patient-led interview. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2010;11(1–2):104–109. doi: 10.3109/17482960902829205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Comfrey A.L., HB . Laurence Earlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1992. A first course in factor analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osborne J.W.A.B..C. Sample size and subject to item ratio in principal components analysis. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2004;9(11) [Epub 6/7/2004] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright B. Fundamental measurement for outcome evaluation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;11(2):261–268. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasch G. The University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1960. Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prieto L., Alonso J., Lamarca R. Classical test theory versus Rasch analysis for quality of life questionnaire reduction. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:27. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell J.D., O'Brien M.R. Quality of life in motor neurone disease — towards a more practical assessment tool? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(3):287–288. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.3.287-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zigmond A.S., Snaith R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibbons C.J., Mills R.J., Thornton E.W., Ealing J., Mitchell J.D., Shaw P.J. Rasch analysis of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) for use in motor neurone disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9(82) doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-82. [Epub 29th September 2011] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibbons C.J., Mills R.J., Thornton E.W., Ealing J., Mitchell J.D., Shaw P.J. Development of a patient-reported outcome measure for fatigue in motor neurone disease: the Neurological Fatigue Index (NFI-MND) Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:101. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cedarbaum J.M., Stambler N., Malta E., Fuller C., Hilt D., Thurmond B. The ALSFRS-R: a revised ALS Functional Rating Scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. J Neurol Sci. 1999;169(1–2):13–21. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mokken R. Mouth; The Hague: 1971. A theory and procedure of scale analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loevinger J. A systematic approach to the construction and evaluation of tests of ability. Psychol Monogr. 1947;61(4):i-49. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karabatsos G. The Rasch model, additive conjoint measurement, and new models of probabilistic measurement theory. J Appl Meas. 2001;2(4):389–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hobart J. Measuring disease impact in disabling neurological conditions: are patients' perspectives and scientific rigor compatible? Curr Opin Neurol. 2002;15(6):721–724. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000044769.39452.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linacre J. Sample size and item calibration stability. Rasch Meas Trans. 1994;7:28. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pallant J.F., Tennant A. An introduction to the Rasch measurement model: an example using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) Br J Clin Psychol. 2007;46:1–18. doi: 10.1348/014466506x96931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choppin B. ERIC Clearinghouse; Washington, D.C.: 1983. A fully conditional estimation procedure for Rasch model parameters. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fisher W. Reliability statistics. Rasch Meas Trans. 1992;6:238. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tennant A., Pallant J. Unidimensionality matters (a tale of two Smiths?) Rasch Meas Trans. 2006;20:1048–1051. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mills R.J., Young C.A., Pallant J.F., Tennant A. Development of a patient reported outcome scale for fatigue in multiple sclerosis: the Neurological Fatigue Index (NFI-MS) Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muthén L.K., Muthén B.O. Statistical analysis with latent variables Version. 2007. Mplus; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andrich D., Sheridan B., Luo G. RUMM Laboratory Pty Ltd.; Perth, Western Australia: 2010. Rasch models for measurement: RUMM2030. [Google Scholar]

- 41.StataCorp . Statacorp LP; College Station, TX: 2011. Stata statistical software: release 12. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Browne M., Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen K., Long J., editors. Testing structural equation models. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X., Bradlow T.G., Wainer H. A general Bayesian model for testlets: theory and applications. Appl Psychol Meas. 2002;26:109–128. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldstein L.H., Atkins L., Landau S., Brown R.G., Leigh P.N. Longitudinal predictors of psychological distress and self-esteem in people with ALS. Neurology. 2006;67(9):1652–1658. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000242886.91786.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abrahams S., Goldstein L.H., AlChalabi A., Pickering A., Morris R.G., Passingham R.E. Relation between cognitive dysfunction and pseudobulbar palsy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62(5):464–472. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.62.5.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]