Abstract

Recent epidemiological data have shown that patients suffering from Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus have an increased risk to develop Alzheimer’s disease and vice versa. A possible explanation is the cross-sequence interaction between Aβ and amylin. Because the resulting amyloid oligomers are difficult to probe in experiments, we investigate stability and conformational changes of Aβ–amylin heteroassemblies through molecular dynamics simulations. We find that Aβ is a good template for the growth of amylin and vice versa. We see water molecules permeate the β-strand–turn−β-strand motif pore of the oligomers, supporting a commonly accepted mechanism for toxicity of β-rich amyloid oligomers. Aiming for a better understanding of the physical mechanisms of cross-seeding and cell toxicity of amylin and Aβ aggregates, our simulations also allow us to identify targets for the rational design of inhibitors against toxic fibril-like oligomers of Aβ and amylin oligomers.

Keywords: Amyloid oligomer, water channel, molecular dynamics, crosses seeding

Amyloid diseases are characterized by the presence of extracellular or intracellular fibrous protein deposits, known as amyloids.1,2 While the precise nature of the toxic agents has not yet been established,3 a likely culprit are amyloid oligomers formed from disease-specific peptides.4,3 Common features5,4 of such oligomers are that they are cytotoxic, recognizable by an oligomer specific antibody and rich in β-sheets. With their fibril-like morphology they can also seed new populations of oligomers.6−8

These commonalities in molecular structure may cause the observed correlations between amyloid diseases. For instance, patients with diabetes have an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.9,10 A controlled community-based epidemiologic and pathological study has indicated also an increased risk of type 2 diabetes in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.11 In Alzheimer disease mouse models an increased circulating Aβ level is correlated with impaired glucose/insulin tolerance and hepatic insulin resistance.12 All these studies suggest a bidirectional relationship between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer disease.13 While Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by the aggregation and accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ), human amylin constitutes the major part of the pancreatic amyloid found in patients with type 2 diabetes.14,15 One possible explanation for the link between the two diseases is cross-seeding, that is, the promotion of aggregation of one protein by another protein.

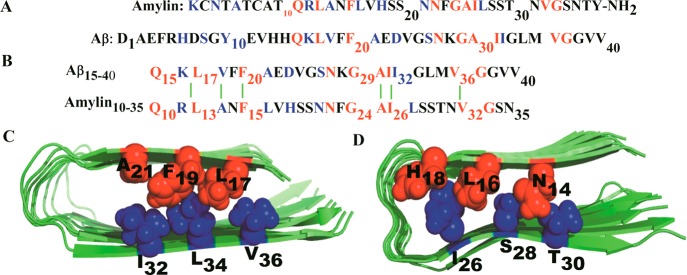

Adding a preformed template to a solution of amyloidic peptides reduces significantly the duration of lag phase in formation of amyloid oligomers. In the case of amylin20–28 and Aβ25–33, the large overlap (90%) in the structural properties,11,16 which both form a U-shaped β-strand–turn−β-strand motif (Figure 1A,B), leads in vitro to formation of amyloid heteroassemblies of Aβ and amylin.17,16 Both peptides are found in blood and cerebrospinal fluid at similar concentrations,18,19 and a recent study found accumulations of mixed amylin and Aβ aggregates in the brain of type II diabetes and AD patients.20 Because the prefibrillar assemblies of both amylin and Aβ destabilize synthetic phospholipid bilayers and cell membranes, one can conjecture that amyloid heteroassemblies of Aβ and amylin have similar toxic properties. This would explain the link between the two diseases.

Figure 1.

Sequence and structure of the amylin and Aβ1–40 domains involved in cross-seeding. (A) Sequences of Aβ1–40 and amylin. Identical residues are indicated in red and similar residues in blue.17 (B) Domains involved in heteroassociation based on structural models of amylin38 and Aβ fibril models.62 The green lines illustrate hydrophobic interactions. (C) Face-to-face hydrophobic contacts between residues L17/V36, F19/L34, and A21/I32 of Aβ and (D) Face-to-face hydrophobic contacts between residues N14/T30, L16/S28, and H18/I26 for amylin. Residues at the N-terminus are colored red and their C-terminal partners in blue.

In order to test this conjecture one needs to determine not only the structure and stability of the Aβ and amylin amyloid assemblies but also how they interact with cell membranes and other molecules. A widely accepted mechanism for the neurotoxicity21 of amyloid oligomers is that they can form membrane or channel pores lowering the permeability barrier22 by enabling water leakage through cell membranes. Another prominent hypothesis is that the oligomers expose hydrophobic sites that facilitate aberrant interactions and sequestration of other proteins, impairing their function.4 Investigating such questions of structure, stability, and functions directly in experiments is difficult, but atomistic mechanisms of amyloid formation23 and growth24−27 can be modeled by molecular dynamics simulations and compared with experimental measurements.28 Examples of such computational studies are recent investigations of amyloid heteroassociation between Aβ and tau fibrils. These studies suggest that the U-turn-based structural core of tau filaments promotes cross-interaction with the amyloid-β peptide, demonstrating the possibility of cross-seeding between nonhomologous proteins.29,30 In this article, we examine the cross-seeding between amylin and Aβ, using molecular dynamics simulations on octamer oligomer of amylin, Aβ, and a mixture of both peptides (four strands from each), respectively. Our simulations test whether the U-shaped fibril model represents the molecular structure of the cross-seeded Aβ–amylin assemblies, and the role of the different structural elements of the U-shaped β-strand–turn−β-strand motif for the stability and conformational dynamics of the Aβ–amylin assembly. These stability investigations are complemented by ones that probe whether water molecules can penetrate their β-strand–turn−β-strand motif pore, that is, whether Aβ–amylin assemblies can lead to water leakage through cell membranes, the commonly accepted mechanism of toxicity. While the purpose of this article is to add to a better understanding of the physical mechanism of cross-seeding between amylin and Aβ and of the mechanism for the cell toxicity of the resulting oligomers, it also points to the β1 and β2 regions as potential targets for the design of aggregation inhibitors.31,32

Results and Discussions

Structural Stability of Self- and Cross-Seeded Oligomers

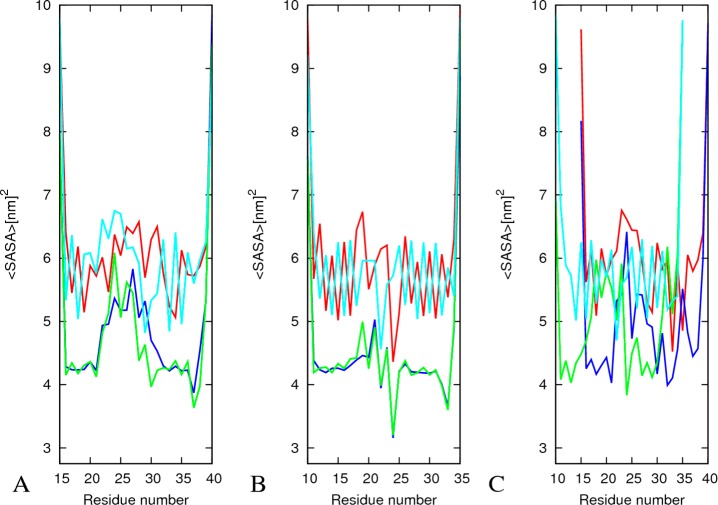

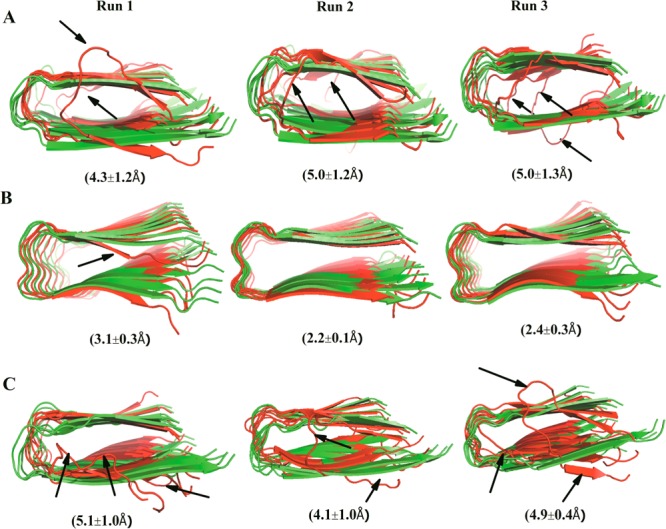

An overall picture of the conformational changes over the course of the simulation can be gained by comparing the average structures with the initial one. The average structure is calculated from the position of all heavy atoms of the protein over the 300 ns molecular dynamics trajectories using the program g_covar of the Gromacs 4.5.3 package. The so-calculated average structures and their Cα-RMSD (root-mean-square deviation) values with respect to the initial structures (Figure 2) show that the U-shaped conformation of the octameric oligomers is retained. Among the three octamers, amylin is the most stable system. It has the lowest Cα-RMSD, with an average ⟨RMSD⟩ in the range of 2.2–3.1 Å. Conformational drifts are observed only for the outer strands in the Aβ15–40 and Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 heteroassemblies leading to average ⟨RMSD⟩ of 4.3–5.1 and 4.1–5.1, respectively. This picture is supported also by average root-mean-square fluctuations calculated either for each residue or for each single strand and shown in Figure S1, Supporting Information. The residues with larger backbone root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) values have increased average solvent accessible surface area (SASA) values as calculated by the standard Gromacs tool g_sas. This suggests that they are exposed to the solvent to a larger degree (Figure 3A–C). Especially, the residues from the inner strands are less solvent-exposed than those of the more flexible outer strands. The central residues in the N terminal (residues 17–21 for Aβ and residues 12–16 for amylin) and C terminal residues (residues 30–35 for Aβ and residues 25–30 for amylin) have much smaller mean solvent exposure than edge strands; that is, they remain inaccessible (Figure 3A–C) to the solvent during the whole simulations. The RMSF and SASA values for the Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 heteroassemblies (Figure S1C, Supporting Information, and Figure 3C) signal that the chains at the border between amylin and Aβ change their configuration to enhance favorable interactions between them (i.e., the amylin strands at the interface have C-terminal RMSF values of about 4 Å compared with about 2 Å in the amylin octamer). This structural adjustment observed at the interface between amylin and Aβ, two peptides with different side-chain packing, is in agreement to previous experimental observation on heteroassembly of amyloid fibrils.33,34

Figure 2.

Average structures and Cα root-mean-square deviations (RMSDs) with respect to the corresponding minimized start configurations. Cartoon representation of the initial (green) and averaged structures (red) from three independent trajectories over 300 ns simulation of (A) Aβ15–40 octamers; (B) amylin10–30 octamers; and (C) Aβ15–40|amylin15–35 octamers. Averaged RMSD values calculated for each peptide with respect to the start configurations are included in parentheses. Major differences between the average and initial structures are highlighted by black arrows pointing out the flexible edge strands.

Figure 3.

Average solvent accessible surface area (SASA) of the three octamers. The average SASA per strand for Aβ15–40 (A), amylin10–35 (B), and Aβ15–40|amylin15–35 (C) octamers. Chain 1, red; chain 4, blue; chain 5, green; and chain 8, cyan. Chain 2, 6, and 7 have SASA values similar to chains 4 and 5, and they are not shown to simplify the figure.

Hydrogen Bond Analysis

The differences in stability between the three studied octamers result from differences in the association forces that keep them together. Especially important here are hydrogen bonds as the architecture of the amyloid fibrils dependent strongly on an array of inter backbone hydrogen bonds between the β-strands within the core of the fibril.35,2

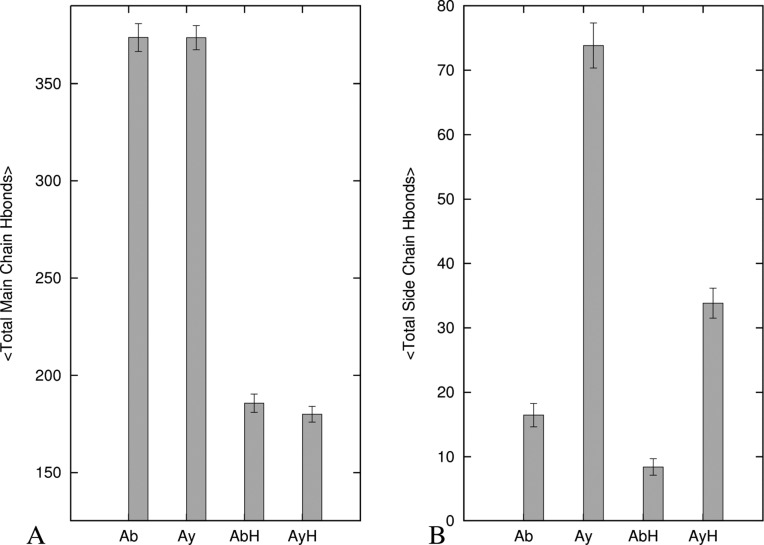

The total number of hydrogen bonds (main chain and sides chains) is shown in Figure 4 for all three oligomers. The corresponding numbers for the key segments (the C terminal, loop, and N terminal regions) are shown in Supplemental Figure S2, Supporting Information. The average number of main chain to main chain hydrogen bonds in the β1 and β2 regions of the Aβ15–40, amylin10–35, and Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 oligomers differ little when the less stable terminal chains 1 and 8 are excluded. Because the U-shaped motif is retained in all three octamers, this indicates inter- and intramolecular main chain hydrogen bonds play a significant role in stabilizing this structure. The number of hydrogen bonds per residue is smaller in the loop region than in the β regions making this region more flexible and less stable (Figure S2, Supporting Information). Aβ15–40 lacks side chain to side chain hydrogen bonds in both β regions while in amylin10–35 such side chain to side chain hydrogen bonds help to retain the U-shaped geometry of the amylin oligomer. While the total number of main chain to main chain hydrogen bonds (which is directly related to in-register hydrogen bonds) is similar in all the three systems, the total number of side chain to side chain hydrogen bonds is larger in amylin10–35 than for both Aβ15–40 and Aβ15–40|amylin10–35. Hence, the lack of strong side chain hydrogen bonds in Aβ15–40 and Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 and their presence in amylin10–35 indicate that such side chain hydrogen bonds contribute to the better retention of the U-shaped geometry in amylin10–35, as has been reported previously.36

Figure 4.

Average numbers of main chain and side chain hydrogen bonds in β-strand–loop−β-strand regions of the three oligomers: (A) total number of main chain hydrogen bonds; (B) total number of side chain hydrogen bonds. Legend: Ab = Aβ15–40, Ay = amylin10–35, AbH = Aβ15–40 part of the heteroassembly system, and AyH = amylin10–35 part of the heteroassembly system.

Hydrophobic Interactions and Oligomer Stability

Besides hydrogen bonds, the U-shaped conformations of amylin37,38 and Aβ39,32 are stabilized by interpeptide hydrophobic interactions of hydrophobic residues. For this reason, we have also monitored for the three octamers the interpeptide hydrophobic interactions between adjacent residues in the L13ANFL17 and A25ILSS29 region of amylin and those in the hydrophobic residues L17VFFA21 and A30IIGL34 in Aβ. Measurements of solvent accessible surface area and root-mean-square fluctuations (Figure 3 and Figure S1, Supporting Information) show that these regions are more stable than the other parts. The hydrophobic contacts between selected adjacent residues in these hydrophobic regions are shown in Table 1. The interstrand hydrophobic side chain contacts for Aβ15–40 are measured between F20 and F20, I32 and I32, and V36 and V36 of each strand and the adjacent successive once. In the case of amylin, the distances between F15 and F15, I26 and I26, and V32 and V32 are measured. Correspondingly, in the Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 oligomer, it is measured based on a combination of the above interactions. The hydrophobic phenylalanine, isoleucine, and valine interstrand contacts are retained in the simulation of the core of both the Aβ15–40 and amylin10–35 octamers, with distances ranging from 4.5 to 5 Å, close to the experimental results of 4.8 Å for amyloid fibrils32 and oligomers.6,32

Table 1. Average Hydrophobic Contact Distances between Selected Adjacent Hydrophobic Residues of Aβ15–40, Amylin15–35 and Their Cross-Seeded Oligomers (Aβ15-40|Amylin15-35).

| Aβ oligomer |

Aβ oligomer |

Aβ oligomer |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F20/F20a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 | I32/I32a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 | V36/V36a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 |

| chains 2–3 | 4.95(0.2) | 4.97(0.2) | 5.30(0.7) | chains 2–3 | 4.79(0.3) | 5.40(0.6) | 4.92(0.3) | chains 2–3 | 4.99(0.5) | 4.81(0.2) | 4.80(0.2) |

| chains 3–4 | 4.93(0.2) | 4.96(0.3) | 4.92(0.3) | chains 3–4 | 4.82(0.2) | 5.24(0.3) | 5.28(0.9) | chains 3–4 | 4.77(0.2) | 4.78(0.2) | 4.77(0.2) |

| chains 4–5 | 4.91(0.2) | 4.95(0.2) | 4.92(0.2) | chains 4–5 | 4.81(0.1) | 4.81(0.2) | 4.73(0.8) | chains 4–5 | 4.99(0.4) | 4.82(0.2) | 4.80(0.2) |

| chains 5–6 | 4.93(0.2) | 4.92(0.2) | 4.97(0.2) | chains 5–6 | 4.96(0.3) | 4.83(0.2) | 4.77(0.1) | chains 5–6 | 5.22(0.2) | 4.85(0.2) | 4.76(0.1) |

| chains 6–7 | 4.82(0.2) | 4.97(0.3) | 4.96(0.3) | chains 6–7 | 6.38(1.6) | 4.99(0.2) | 4.91(0.2) | chains 6–7 | 5.10(0.2) | 4.82(0.2) | 4.90(0.2) |

| mean ± SD | 4.91 ± 0.05 | 4.95 ± 0.02 | 5.01 ± 0.2 | mean ± SD | 5.15 ± 0.7 | 5.05 ± 0.3 | 4.92 ± 0.2 | mean ± SD | 11.1 ± 0.52 | 1.59 ± 0.8 | 11.09 ± 0.4 |

| amylin oligomer |

amylin oligomer |

amylin oligomer |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F15/F15a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 | I26/I26a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 | V32/V32a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 |

| chains 2–3 | 4.82(0.2) | 4.81(0.2) | 4.82(0.2) | chains 2–3 | 4.79(0.2) | 4.78(0.2) | 4.77(0.2) | chains 2–3 | 5.24(0.4) | 4.77(0.2) | 4.86(0.2) |

| chains 3–4 | 4.75(0.2) | 4.79(0.2) | 4.83(0.2) | chains 3–4 | 4.80(0.2) | 4.81(0.2) | 4.89(0.2) | chains 3–4 | 4.99(0.3) | 4.70(0.1) | 4.81(0.2) |

| chains 4–5 | 4.79(0.2) | 4.81(0.2) | 4.86(0.2) | chains 4–5 | 4.88(0.2) | 4.91(0.2) | 4.94(0.2) | chains 4–5 | 4.95(0.2) | 4.70(0.2) | 4.75(0.2) |

| chains 5–6 | 4.83(0.2) | 4.79(0.2) | 4.94(0.2) | chains 5–6 | 4.79(0.2) | 4.89(0.2) | 4.79(0.2) | chains 5–6 | 4.78(0.2) | 4.73(0.2) | 4.86(0.2) |

| chains 6–7 | 4.81(0.2) | 4.81(0.2) | 4.82(0.2) | chains 6–7 | 4.86(0.2) | 4.91(0.2) | 4.77(0.2) | chains 6–7 | 4.89(0.2) | 4.76(0.2) | 4.74(0.2) |

| mean ± SD | 4.80 ± 0.03 | 4.80 ± 0.01 | 4.80 ± 0.05 | mean ± SD | 4.82 ± 0.04 | 4.86 ± 0.06 | 4.83 ± 0.08 | mean ± SD | 4.97 ± 0.2 | 4.73 ± 0.03 | 4.80 ± 0.06 |

| Aβ–amylin

heteroassembly |

Aβ–amylin

heteroassembly, Aβ |

Aβ–amylin

heteroassembly, Aβ |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F/Fa contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 | I/Ia contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 | V/Va contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 |

| chains 2–3 (Aβ) | 4.82(0.2) | 4.89(0.2) | 4.79(0.2) | chains 2–3 (Aβ) | 5.02(0.2) | 4.81(0.2) | 4.86(0.2) | chains 2–3 (Aβ) | 5.32(0.7) | 5.07(0.3) | 4.89(0.2) |

| chains 3–4(Aβ) | 4.81(0.2) | 5.14(0.3) | 4.81(0.2) | chains 3–4(Aβ) | 4.96(0.2) | 5.26(0.2) | 4.95(0.2) | chains 3–4(Aβ) | 7.90(2.4) | 4.90(0.3) | 4.82(0.2) |

| chains 4–5 | 4.89(0.2) | 4.98(0.2) | 5.07(0.2) | chains 4–5 | 6.61(0.5) | 6.57(0.3) | 6.61(0.4) | chains 4–5 | 8.87(2.4) | 6.79(0.6) | 7.65(0.9) |

| chains 5–6 (amy.) | 4.88(0.2) | 4.92(0.2) | 4.84(0.2) | chains 5–6 (amy.) | 5.09(0.4) | 4.95(0.2) | 5.16(0.2) | chains 5–6 (amy.) | 5.13(0.2) | 5.03(0.3) | 4.94(0.3) |

| chains 6–7(amy.) | 4.92(0.2) | 4.94(0.2) | 4.82(0.2) | chains 6–7(amy.) | 5.22(0.4) | 5.09(0.3) | 4.99(0.4) | chains 6–7(amy.) | 5.51(1.1) | 4.88(0.2) | 4.74(0.2) |

| mean ± SD | 4.86 ± 0.05 | 4.97 ± 0.1 | 4.87 ± 0.1 | mean ± SD | 5.38 ± 07 | 5.34 ± 0.8 | 5.31 ± 0.7 | mean ± SD | 6.55 ± 1.7 | 5.33 ± 0.8 | 5.41 ± 1.3 |

Hydrophobic contact of Cα–Cα distances (Å) between the residues F20/F20, I32/I32, and V36/V36 of Aβ and F15/F15, I26/I26, and V32/V32 of amylin and their heteroassembly. Values are shown after excluding peptides chains 1 and 8.

The F15–F15, F15–F20, and F20–F20 residues (Table 1) in the β1 regions of the Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 oligomer are within 4.5 to 5 Å of each other. This includes the F15–F20 contacts at the interface between amylin and Aβ. A similar result is also observed for adjacent I26–I26, I32–I32, V32–V32, and V36–V36 residues within β2 regions. On the other hand, the hydrophobic contacts between adjacent I26–I32 and V32–V36 residues at the interface between Aβ and amylin (where there is a larger degree of sequence dissimilarity) in the β2 regions of Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 oligomer are larger than the expected distance of about 5 Å. The average distance between such pairs of residues is more than 6.5 and 7 Å, respectively. These distances suggests that a combination of stable hydrophobic contacts in the β1 regions and a more flexible hydrophobic contact in the β2 regions is necessary to accommodate side-chain packing between the two peptides in the heteroassemblies.

Face-to-Face Hydrophobic Contacts Inside the Interior of the Oligomers

Face-to-face interactions between β-sheets are common in proteins and amyloids. They involve hydrophobic surfaces with good shape complementarity that are held together through van der Waals and hydrophobic interactions. Such hydrophobic contacts often involve large, branched, nonpolar side chains of valine, leucine, isoleucine, and phenylalanine, because they can provide large hydrophobic areas that maximize interactions. However, polar residues such as tyrosine, tryptophan, serine, and threonine can also participate.40 For this reason, we have monitored the hydrophobic contact between residues V36/L17, L34/F19, and I32/A21 of Aβ and T30/N14, S28/L16, and I26/H18 for amylin (Figure 1C,D). These contacts are calculated also in the heteroassembly, and the results are shown in Table 2. After excluding the terminal strands, the average distances between the two β-sheets within the β1 and β2 regions of oligomers are within 7.5 to 11 Å (Table 2). These distances are measured between the residues involved in the face-to-face hydrophobic contacts and are in agreement with experimental results, 8–11 Å.41 Hence, in all three oligomers, the core and the β-strand–turn−β-strand motif are stabilized by such face-to-face hydrophobic interactions. The distance between the two β-sheets is about 10 Å for the Aβ octamer, while in amylin the distances are smaller by 1–2 Å. However, in the cross-seeded Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 octamers, the amylin strand at the interface between Aβ and amylin chains has face-to-face hydrophobic distances of 10 Å indicating that at the interface the interaction of Aβ and amylin chains requires structural flexibility and conformational adaptation for better shape complementary.

Table 2. Face-to-Face Hydrophobic Contact Distances of Aβ15-40, Amylin15-35 and Their Cross-Seeded Oligomers (Aβ15-40|Amylin15-35).

| Aβ oligomer |

Aβ oligomer |

Aβ oligomer |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L17/V36a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 | F19/L34a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 | A21/I32a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 |

| chain 2 | 9.4(0.7) | 9.2(0.6) | 9.8(1.0) | chain 2 | 10.9(0.9) | 11.2(0.6) | 10.9(0.8) | chain 2 | 10.7(0.9) | 13.2(0.7) | 10.8(1.3) |

| chain 3 | 8.6(0.7) | 8.1(0.6) | 9.6(0.6) | chain 3 | 10.3(0.5) | 10.5(0.5) | 10.5(0.8) | chain 3 | 10.8(0.5) | 10.5(0.7) | 10.6(0.8) |

| chain 4 | 8.1(1.2) | 7.4(0.7) | 9.0(0.6) | chain 4 | 10.0(0.5) | 10.3(0.5) | 10.3(0.5) | chain 4 | 11.5(0.6) | 11.3(0.6) | 11.1(0.6) |

| chain 5 | 6.7(0.3) | 7.1(0.6) | 7.9(0.6) | chain 5 | 9.4(0.4) | 9.8(0.5) | 10.1(0.5) | chain 5 | 11.9(0.6) | 11.6(0.6) | 11.6(0.5) |

| chain 6 | 7.1(0.4) | 6.9(0.3) | 6.9(0.3) | chain 6 | 9.3(0.5) | 9.3(0.4) | 9.5(0.4) | chain 6 | 11.7(0.6) | 11.5(0.6) | 11.6(0.5) |

| chain 7 | 9.1(0.7) | 6.9(0.4) | 7.1(0.5) | chain 7 | 10.5(0.7) | 9.2(0.4) | 9.3(0.6) | chain 7 | 11.9(0.9) | 11.4(0.6) | 10.9(0.7) |

| mean ± SD | 8.1 ± 1.1 | 7.6 ± 0.9 | 8.4 ± 1.3 | mean ± SD | 10.1 ± 0.2 | 10.1 ± 0.8 | 10.1 ± 0.6 | mean ± SD | 11.4 ± 0.5 | 11.6 ± 0.9 | 11.1 ± 0.4 |

| amylin oligomer |

amylin oligomer |

amylin oligomer |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N14/T30a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 | L16/S28a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 | H18/I26a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 |

| chain 2 | 7.3(0.4) | 7.8(0.4) | 6.4(0.2) | chain 2 | 8.1(0.4) | 9.1(0.4) | 6.8(0.2) | chain 2 | 8.8(0.5) | 8.8(0.4) | 8.8(0.3) |

| chain 3 | 7.5(0.5) | 8.0(0.4) | 6.4(0.2) | chain 3 | 8.6(0.5) | 9.2(0.4) | 6.7(0.2) | chain 3 | 8.5(0.5) | 8.8(0.4) | 9.2(0.3) |

| chain 4 | 7.7(0.5) | 7.9(0.3) | 6.5(0.3) | chain 4 | 8.9(0.6) | 9.1(0.4) | 7.0(0.4) | chain 4 | 8.8(0.5) | 8.9(0.4) | 9.0(0.3) |

| chain 5 | 7.6(0.4) | 8.0(0.3) | 6.9(0.4) | chain 5 | 9.3(0.6) | 9.0(0.4) | 7.2(0.5) | chain 5 | 9.6(0.7) | 8.7(0.4) | 8.8(0.3) |

| chain 6 | 7.6(0.4) | 7.8(0.4) | 6.4(0.4) | chain 6 | 9.8(0.7) | 9.0(0.5) | 7.0(0.5) | chain 6 | 10.1(0.7) | 8.6(0.6) | 9.1(0.3) |

| chain 7 | 7.7(0.4) | 7.7(0.4) | 6.4(0.5) | chain 7 | 10.6(0.5) | 9.1(0.8) | 7.2(0.8) | chain 7 | 9.8(0.6) | 8.9(0.7) | 9.0(0.4) |

| mean ± SD | 7.6 ± 0.1 | 7.9 ± 0.1 | 6.5 ± 0.2 | mean ± SD | 9.3 ± 0.9 | 9.1 ± 0.1 | 7.0 ± 0.2 | mean ± SD | 9.3 ± 0.6 | 8.8 ± 0.1 | 9.0 ± 0.2 |

| Aβ–amylin

heteroassembly, Aβ |

Aβ–amylin

heteroassembly, Aβ |

Aβ–amylin

heteroassembly, Aβ |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L17/V36a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 | F19/L34a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 | A21/I32a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 |

| chain 2 | 12.1(0.7) | 11.2(0.5) | 11.4(0.4) | chain 2 | 10.5(1.2) | 10.3(1.1) | 11.7(0.9) | chain 2 | 10.4(0.9) | 11.5(0.7) | 10.1(0.8) |

| chain 3 | 10.8(0.5) | 11.9(0.7) | 9.8(0.4) | chain 3 | 9.3(0.4) | 9.7(0.6) | 10.5(0.6) | chain 3 | 11.3(0.5) | 11.8(0.5) | 10.2(0.7) |

| chain 4 | 6.1(0.3) | 8.2(0.7) | 6.0(0.3) | chain 4 | 9.4(0.4) | 9.4(0.5) | 9.2(0.5) | chain 4 | 11.3(0.6) | 11.4(0.5) | 10.8(0.5) |

| mean ± SD | 9.7 ± 3.2 | 10.4 ± 2.0 | 9.1 ± 2.75 | mean ± SD | 9.6 ± 0.4 | 9.8 ± 0.5 | 10.5 ± 1.3 | mean ± SD | 11.0 ± 0.5 | 11.6 ± 0.2 | 10.4 ± 0.4 |

| Aβ–amylin

heteroassembly, amylin |

Aβ–amylin

heteroassembly, amylin |

Aβ–amylin

heteroassembly, amylin |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N14/T30a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 | L16/S28a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 | H18/I26a contacts | run 1 | run 2 | run 3 |

| chain 5 | 10.6(0.8) | 10.1(0.7) | 9.4(0.4) | chain 5 | 12.1(0.7) | 11.2(0.5) | 11.4(0.4) | chain 5 | 10.0(0.6) | 7.1(0.40) | 9.3(0.6) |

| chain 6 | 7.7(0.4) | 9.0(0.5) | 7.6(0.6) | chain 6 | 10.8(0.5) | 11.9(0.7) | 9.8(0.4) | chain 6 | 8.6(0.5) | 10.2(0.5) | 8.8(0.4) |

| chain 7 | 6.4(0.3) | 8.3(0.4) | 6.4(0.3) | chain 7 | 6.1(0.3) | 8.2(0.7) | 6.0(0.3) | chain 7 | 8.6(0.4) | 9.3(0.6) | 8.7(0.4) |

| mean ± SD | 8.2 ± 2.1 | 9.2 ± 0.9 | 7.8 ± 1.5 | mean ± SD | 9.6 ± 3.2 | 10.4 ± 1.9 | 9.1 ± 2.7 | mean ± SD | 9.1 ± 0.8 | 8.9 ± 1.6 | 8.9 ± 0.3 |

Hydrophobic contact of Cα- Cα distances (Å) between the residues L17/V36, F19/L34 and A21/I32 of Aβ and N14/T30, L16/S28 and H18/I26 of amylin and their heteroassembly. Values are shown after excluding peptides chains 1 and 8.

Salt Bridge Analysis for the Aβ Self-Seeding and Its Cross-Seeding with Amylin

It has been proposed that the loop region connecting the two β-sheets of the U turn or (β arch) model of Aβ are stabilized by a salt bridge between D23 and K2842,32 that prevents larger backbone motions. Hence, we also probe the effect of the salt bridge on the stability of the aggregates on the Aβ and its hetero-octamer assemblies. The salt bridge distance is calculated as the averaged distance of the C=O bonds of the carboxyl group of D23 to the N atom of the NH3+ in K28 of the intrachain salt bridge (D23n/K28n) or the interchain salt–bridge (D23n/K28n+1) as the carboxylate group of D23n dynamically relocates between the amine groups of adjacent K28n or K28n+1 residues.32,43 In agreement with previous simulations of the pentamer Aβ15–40,32 we observe that the Aβ15–40 octamers form more stable interchain salt bridges than intrachain salt bridges. Note that the edge peptides at the ends of the oligomer are excluded, because they are highly flexible. The interchain and intrachain salt bridge in the Aβ15–40|amylin15–35 heteroassembly from the Aβ15–40 tetramer portion also forms a stable inner salt bridge, with strong intrachain salt bridge (Figure S3, Supporting Information). Hence, the presence of these salt bridges is important for stabilizing the hydration cavity not only of the Aβ15–40 octamers but also of the cross-seeded Aβ15–40|amylin15–30 heteroassembly.

The MM-PBSA Binding Free Energies for Tetramer-Tetramer Association

The binding free energy between the two tetramers for the octameric oligomers is calculated according to the thermodynamic cycle shown in Figure S4, Supporting Information, using the MM-PBSA approach.11,28 This approach is computationally less expensive than thermodynamic integration or free energy perturbation methods because it evaluates only the bound and unbound states.44 However, because the approach does not take into account explicitly water and ions but models their effects by a continuum approach, its application is limited to systems without high charges where screening by water and ions is less critical. Furthermore, entropic contributions due to the release or trapping of water or ions are neglected in this approach. Despite these and other limitations, MM-PBSA, can yield reasonable approximations of relative binding energies for protein-to-protein association.45,46 In our case, we generate 1250 equally spaced snapshots of each complex (every 40 ps) from the molecular dynamics trajectories, and all water molecules and counterions were removed before MM-PBSA calculations with the MMPBSA.py script in AMBER11. The solute entropic contributions (TΔS) have not been calculated since they cannot be estimated sufficiently accurately and their contribution to the total energy difference is small compared with the term that results from conformational changes.47,48

The total binding free energy for all three octamers is negative, that is, favors the stability of the aggregates over that of separated tetramers. We have listed in Table 3 both the total binding energies and their components. This separation into components can help us to understand the contributions of electrostatic, van der Waals, polar, and nonpolar interactions in stabilizing of oligomers. The electrostatic energy of Aβ15–40 and Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 oligomers is negative and favors the stability of the complex, but it is positive and therefore destabilizing for the amylin10–35 octamer. Absolute values of the van der Waals interaction are larger than the electrostatic contributions, and negative for all three systems. Hence, the van der Waals interaction contribution to the stability of the oligomers is significantly favorable. The nonpolar solvation contributions also favor the octamer in all three cases; however, the larger polar solvation energy turns the total solvation energy of the Aβ15–40 and Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 octamers positive, that is, destabilizes them, while it is negative and stabilizing for the amylin10–35 complex.

Table 3. The Binding Energy of Tetramer-to-Tetramer Interactions of the Octameric Oligomers and Contributions of Solvation, van der Waals, and Electrostatic Interactions Using the Single Trajectory MM-PBSA Methoda.

| ⟨ΔEvdw⟩ | ⟨ΔEele⟩ | ⟨ΔGPB⟩ | ⟨ΔGSA⟩ | ⟨ΔGsolv⟩ | ⟨ΔGbinding⟩ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ15–40 | traj 1 | –135.4 | –24.6 | 43.1 | –11.2 | 31.8 | –128.3 |

| traj 2 | –126.4 | –39.9 | 49.9 | –10.9 | 38.9 | –127.3 | |

| traj 3 | –130.3 | –48.6 | 60.0 | –11.4 | 48.7 | –130.2 | |

| traj 4 | –132.6 | –62.5 | 67.6 | –11.3 | 56.3 | –138.8 | |

| mean valueb | –131.2 | –43.9 | 55.1 | –11.2 | 43.9 | –131.1 | |

| SDc | 3.8 | 15.9 | 10.9 | 0.2 | 10.8 | 5.3 | |

| amylin15–30 | traj 1 | –140.1 | 126.1 | –104.6 | –10.9 | –115.6 | –129.6 |

| traj 2 | –138.2 | 144.8 | –119.6 | –10.9 | –130.5 | –123.5 | |

| traj 3 | –140.5 | 135.9 | –111.5 | –11.1 | –122.5 | –127.1 | |

| traj 4 | –141.2 | 146.9 | –123.3 | –10.8 | –134.1 | –128.4 | |

| mean valueb | –140.0 | 138.4 | –114.7 | –10.9 | –125.7 | –127.2 | |

| SDc | 1.1 | 8.21 | 7.2 | 0.1 | 7.2 | 2.3 | |

| Aβ15–40|amylin15–30 | traj 1 | –122.7 | –15.4 | 59.5 | –10.5 | 46.9 | –91.1 |

| traj 2 | –122.6 | –23.7 | 68.4 | –10.5 | 57.9 | –88.3 | |

| traj 3 | –135.5 | –35.6 | 82.7 | –11.2 | 71.4 | –99.7 | |

| traj 4 | –122.3 | –37.6 | 83.2 | –10.9 | 72.2 | –87.7 | |

| mean valueb | –125.8 | –28.1 | 73.4 | –10.8 | 62.1 | –91.7 | |

| SDc | 6.5 | 10.4 | 11.6 | 0.4 | 12.1 | 5.5 |

ΔEele, non-solvent electrostatic potential energy; ΔGPB, electrostatic contributions to the solvation free energy calculated with Poisson–Boltzmann equation; GSA, nonpolar contributions to solvation free energy; ΔEvdw, van der Waals potential energy; ΔGbinding, calculated binding, and ΔGsolv are total solvation energies. Data are shown as mean with the standard deviation (SD) in brackets. ΔGbinding = ΔEvdw + ΔEele + ΔGsolv; ΔGsolv = ΔGPB + ΔGSA.

Mean values are calculated from the four trajectories for each model resulting from two independent simulations.

The standard deviation (SD) therefore describes the deviation between the four independent simulations. Results are averages over four MD runs.

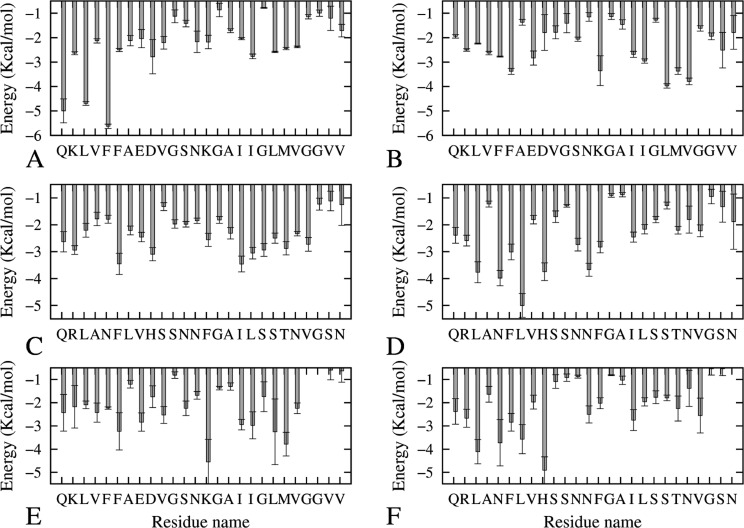

A decomposition of the free energies according to residues points to several amino acids as key contributors to the overall binding energy. Figure 5 and Figure S5, Supporting Information, display the residues that make significant favorable or unfavorable contributions to the van der Waals and electrostatic binding free energy of the two monomers at strands 4 and 5 of the octamers. The residues with the most favorable van der Waals interaction contributions to the binding free energy between the two chains are in the β1 and β2 regions (that is, L13ANFL17 in the β1 region and A25ILSS29 in β2 region of amylin, L17VFFA21 in the β1 region and A30IIGL34 in the β2 region in Aβ, and L13ANFL17 in the β1 region and A25ILSS29 in in the β2 region of amylin and L17VFFA21 in the β1 region and A30IIGL34 in the β2 region in Aβ of the Aβ–amylin heteroassembly). This observation agrees with the hydrogen bond network and hydrophobic contacts observed in Figure 4 and Table 1. Note also that the charged residues involved in the salt bridge in Aβ15–40 and Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 heteroassemblies (D24–K28 and E23–K28) contribute favorably to the backbone and side-chain van der Waals term in the binding free energy.

Figure 5.

van der Waals contributions to the binding free energy from interactions between the interface strands in each of the three oligomers: (A) strand 4 of Aβ15–40; (B) strand 5 of Aβ15–40; (C) strand 4 of amylin15–35; (D) strand 5 of amylin15–35; (E) strand 4 (Aβ15–40) of Aβ15–40|amylin15–35; (F) strand 4 (amylin15–35) of Aβ15–40|amylin15–35.

The total per residue decomposition of electrostatic interaction for strands 4 and 5 of the octamers is shown in Figure S5, Supporting Information. Residues that contribute most to the electrostatic interaction in Aβ15–40 include the charged residues Q15, K16, E23, D24, and K28. The E23 and D24 residues involved in salt bridge with K28 have an electrostatic interaction opposite to the contribution of K28, which has been observed also in previous simulations.49 The neighboring K16 disfavors oligomerization because of the unfavorable vicinity to the positively charged side chain amino groups, but the major unfavorable per residue electrostatic interaction in amylin oligomers is from R11. The adjacent positively charged side chain amino leads to a positive electrostatic interaction term for the tetramer-to-tetramer binding energy term of amylin (see Table 3). This unfavorable electrostatic contribution of the R11 from the amylin strand is suppressed at the interface of the Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 heteroassembly (see Figure S5, Supporting Information) leading to an overall negative electrostatic interaction term for the tetramer-to-tetramer binding energy term of amylin (see Table 3).

The binding free energy of Aβ15–40, amylin10–35, and Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 heteroassemblies over the constituting tetramers indicates that the nonpolar electrostatic and van der Waals terms are favorable. On the other hand, the intermolecular electrostatic and the electrostatic solvation terms cancel each other and contribute little to the association of the three oligomer systems. The per-residue energy decomposition of the nonpolar van der Waals interactions shows that the stabilizing contributions come from hydrophobic residues that are involved in the face-to-face intrastrand and interstrand interactions of all three oligomers (i.e., L17, F19, F20, I32, I34, and V36 in Aβ15–40; N14, F15, L16, L17, H18, I26, S28, T30 and V32 in amylin10–35; combination of these key amino acids in the Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 heteroassembly) through nonpolar contacts between main chains and side chains.

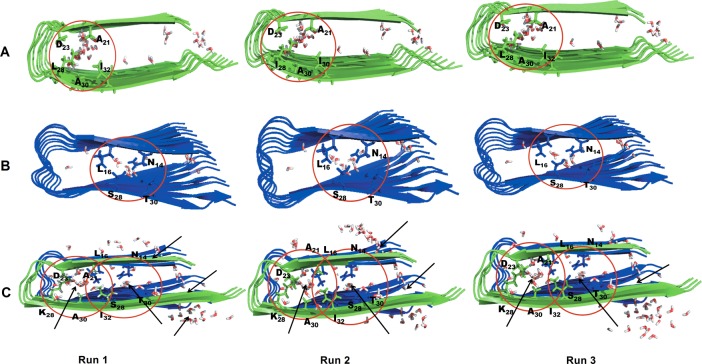

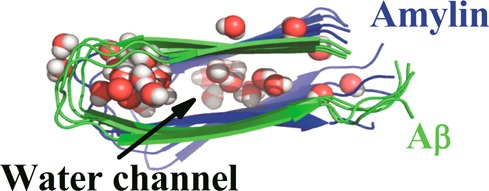

Interior Water Channels of the Octameric Oligomers and Toxicity

All three octamer oligomer simulations start without waters molecules inside the β-strand–turn−β-strand motif. However, during the course of the simulation, we observe that water molecules permeate the interior of the complexes. A snapshot from an early part of the production simulation illustrates that water molecules quickly and deeply penetrate into the interior of the oligomers (Figure 6). This points to water leakage through cell membranes as the cause for toxicity of β-rich amyloid oligomers. Note that our results here differ from previous studies of infinitely long fibrils where water molecules were absent in the interior. The difference is likely due to the slow equilibration between interior water and the bulk phase43,50 because in molecular dynamics simulations of finite Aβ fibril segments, internal water molecules were also present.43,51

Figure 6.

Snapshots of water molecules in the interior hydration cavity of the start octamer configurations: (A) Aβ15–40, (B) amylin15–35, and (C) Aβ15–40|amylin15–35). The water molecules are white and red colored. Residues that interact with water molecules in Aβ15–40 (panel A, between D23 and K28 shown within the circle in blue stick representation), amylin15–35 (panel B, between N14, S28, and T30 shown within the circle in blue stick representation), and Aβ15–40|amylin15–35 cross-seeding (panel C, between D23 and K28 for Aβ15–40 and between N14, S28, and T30 shown within the circle in stick for amylin15–35) are indicated.

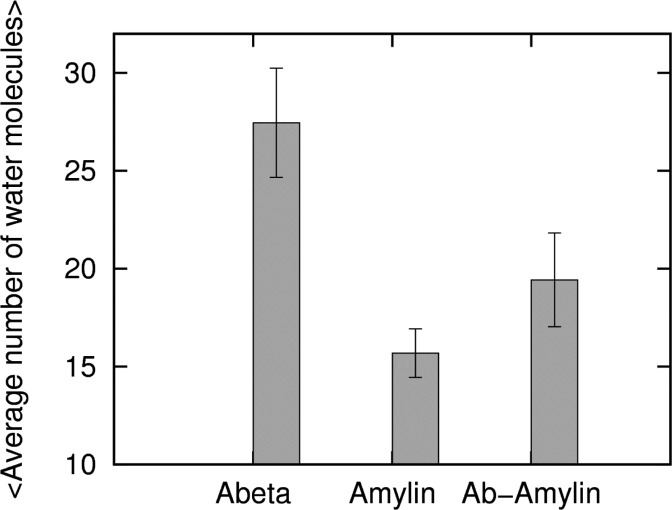

The number of water molecules inside the β-strand–turn−β-strand motif pore of the oligomers is plotted in Figure 7 over the course of the molecular dynamics trajectory. An internal water channel for the Aβ is found in the vicinity of the loop region of the D23–K28 salt-bridges (A21, D23, K28, A30, and I32). On the other hand, the loop region in amylin formed by H18–N23 is devoid of water molecules as was observed also in a recent simulation by Liang et al.37 Our simulations show that water molecules enter into polar cavities (internal polar side chains or ionizable groups) around the polar amino acids N14, L16, S28, and T30 (Figure 7) instead of the loop region of amylin, which is rich in hydrophobic amino acids. This is consistent with a recent study,52 which showed that the water content in the protein interior can be modulated by the polarity of the protein cavity. The average number of internal waters differs for the three oligomers. We find about 30 molecules of water in Aβ15–40, about 20 water molecules in Aβ15–40|amylin15–35 heteroassembly, but only around 15 water molecules in the amylin15–35 oligomer.

Figure 7.

Time-averaged numbers of internal water molecules. Average number of water molecules in the inner cavity of (Abeta) Aβ15–40, (Amylin) amylin10–35, and (Ab-Amylin) Aβ15–40|amylin15–35. The averages are over all three trajectories.

The location in the β-strand–turn−β-strand motif, where water molecules are present, differs among the three octamers. In the Aβ octamer, water molecules are located around the loop region, while in amylin they are found in the middle of the two β-stands. This difference in the location of the water cavity determines the flow of the water molecules across the cross-seeded oligomer, especially at the border. Here, water coming from the loop region of Aβ encounters the hydrophobic loop region of amylin. Such interfacial interaction will affect the stability of strand-to-strand association at this particular location as is evident in the RMSF and SASA and hydrophobic contacts (Figure 3, Figure S1, Supporting Information, and Table 1, respectively). However, despite the difference in the location of hydration cavity in the heteroassembly, we observe still a flow of water molecules from one side into the other. This suggests flow of water and electrolyte through the pore as a possible common toxicity mechanism, because the stability of the oligomers in our simulations indicates that Aβ and amylin can cross-seed to form structures capable of inserting into membranes. Hence, our results suggest cross-sequence interaction between Aβ and amylin as the apparent link between Alzheimer’s disease and type II diabetes.

Conclusions

We have reported results from long constant temperature molecular dynamics simulations of preformed octamers (amylin10–35, Aβ15–40, and a heteroassembly of both amylin10–35 and Aβ15–40) in explicit solvent. Our analysis shows that with the exception of the edge strands, the individual chains in all three octamers retain a β-strand–turn−β-strand motif under physiological conditions. Throughout the whole trajectories, the oligomers are characterized by close hydrophobic packing at the N-terminus, fluctuations in the loop region, moderate flexibility in the C-terminal region, and larger flexibility in the outer layer strands of Aβ15–40 and amylin10–35 chains. All three octamers keep the network of hydrogen bonds and the interstrand and intrastrand hydrophobic contacts that stabilize the U-shaped start configurations. This highlights the importance of hydrophobic interactions and the highly organized interstrand hydrogen bonding in conferring stability to an octamer. Our results also demonstrate the need to monitor the underappreciated face-to-face hydrophobic interactions for probing dynamics in the internal structure. The distance between the two β-sheets is about 2 Å smaller in the amylin octamer than in the amylin strand at the interface between Aβ and amylin chains in the cross-seeded Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 octamers. This smaller distance indicates that the interaction of the two peptides at the interface requires structural flexibility and conformational adaptation for better shape complementarity. Note that despite their sequence dissimilarity the Aβ and amylin chains maintain even in the mixed Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 oligomer their initial U-shaped motif without distortion (except for the terminal strands 1 and 8). MM-PBSA calculations show that the Aβ15–40|amylin15–35, amylin10–35, and Aβ15–40 octamers are favored over the corresponding systems of two separated tetramers by average interaction energies of −91.70, −127.16, and −131 (kcal/mol). Even accounting for limited accuracy of MM-PBSA calculations, these numbers show that lateral growth is favorable for both self- and cross-seeded oligomers. The favorable free energy of the cross-seeded oligomer results from changes in side-chain packing (as can be seen from the per residue decomposition of energy terms) in the flexible C-terminal region that allow the peptides at the border between Aβ and amylin chains to adopt configurations that stabilize the heteroassembly. Note that by design our stability analysis cannot give any information on whether Aβ seeds amylin or vice versa. According to Nuallian et al.,16 Aβ fibrils seeded amylin efficiently but amylin was less efficient in seeding the growth of Aβ aggregates. Our simulations only indicate the stability of such aggregates that are also observed experimentally in the brain–blood vessel of both of demented diabetics and late onset Alzheimer’s Disease nondiabetic patients.20

The characterization of toxic soluble oligomeric intermediates is a challenge because of their transient nature, small sizes, and heterogeneous morphologies.53 Several structural models have been suggested for amyloid oligomers including annular or β-barrel,53 cylindrin,6 and parallel in-register β-sheet. Recent X-ray diffraction and electron microscopy studies evidenced that laterally associated fibril filaments of Aβ can wrap around forming a hole along the axis of assembly. All these models of amyloid-β fibrillar oligomers have in common that they form pore-like structures believed to be essential for their toxicity. Our recent simulations on small hydrophobic cylindrins revealed water molecules entering into the interior channel that might lead to leakage upon insertion into the membrane.47 On the other hand, a recent study on the mechanism of membrane insertion of toxic fibrils like Aβ suggests that a U-shaped trimer is the minimum oligomer size for effective insertion to membrane and its toxicity.54 Note that while a recent NMR study has reported partial helical structures for dissolved amylin peptides, these early helical intermediates convert into β structures upon binding to membrane.55 Computational studies by Jang et al. of the interactions of lipid bilayer with preformed Aβ protofilaments54 found U-shaped Aβ oligomers in both aqueous solution and membrane. Another simulation study56 of Aβ-monomer and Aβ-dimers bound to a membrane model starting from an initial helical peptide conformation showed again β-hairpin motif formation. These studies suggest that Aβ aggregates in lipid bilayers adopt a structure similar to that in aqueous medium and especially that the U-shaped motif is preserved. In the present simulations, all three oligomers retain their fibril-like U-shaped structure, and water molecules are found to pass through hydration channels. In Aβ, these are located around the loop region, while in amylin, the water molecules are found in the middle of the two β-stands near a group of polar amino acids whose side chains point toward the interior of the oligomer cavity (N14, S28, and T30). Despite the different locations of the hydration channels in Aβ15–40 octamers and amylin10–35 octamers, we find a flow of internal water molecules from amylin10–35 side into the Aβ15–40 in the cross-seeded Aβ15–40|amylin15–35 octamer.

The presence of a hydration cavity and the maintenance of U-shaped structure in by the fibril-like octamers suggest as a common toxicity mechanism, the leakage of water and electrolyte through the pore in the various assemblies of amyloid peptides, both homo-oligomers and cross-seeded hetero-oligomers. Our simulation indicates that the hydrophobic core comprising the β1 and β2 regions of the cross-seeded model is crucial for the stability and elongation of the aggregate. These regions should therefore be considered as potential targets for structure-based design of aggregation inhibitors.57,58

Methods

Construction of the Fibril-like Oligomer Models

It is known from NMR studies that Aβ fibers of various Aβ oligomers59 share a U-shaped motif where two β-strand segments (residues 10–24 and 30–40) are joined by a U-turn and stabilized by interior salt bridges between residues D23 and K28.60,42 Amylin has a similar β-strand–loop−β-strand motif, with the loop region located at residues 18–27 straddled by two β-strands comprising residues 8–17 and 28–37.11 Since both Aβ and amylin fibril models contain this U-shaped motif, cross interaction is assumed to depend mostly on their β-strand domains,61 and we use in the present study not the full-length peptides but truncated fragments that contain this motif. This is justified because residues 1–16 are disordered in Aβ1–42 fibrils and residues 1–9 in Aβ1–40 fibrils, and Takeda et al50 found that the Aβ1–40 and Aβ10–40 systems are equivalent. Hence, we make in the present study the assumption that Aβ15–40 fibrils are similar to such of Aβ1–40 or Aβ10–40. For amylin, residues 1–7 are not part of a β-sheet in the experimental structure, and because of a disulfide bridge between cysteine residues 2 and 7,38 do not contribute to aggregate assembly. In order to ensure equal length of our molecules, we therefore used truncated Aβ15–40 and amylin10–35 peptides (capped with acetyl and amide groups to mimic the full-length peptide) in the present study. The Aβ15–40 fibril model is derived from protofilament models of Aβ9–42 (http://people.mbi.ucla.edu/sawaya/jmol/fibrilmodels/), Colletier et al.,62 after removing the residues 9–14 and residues 41–42. The amylin10–35 fibril model is obtained in a similar manner from the model of amylin1–37. Tetramers of these fragments were extracted from the fibril models of the Eisenberg group38,62 and are used to construct Aβ15–40 octamers, amylin10–35 octamers, and Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 octamer heteroassemblies, taking into consideration the interactions in the β-structure domain and ones that stabilize the U-turn, e.g., hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic interactions, polar interactions, and salt bridges. For building the Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 octamer heteroassembly, we align and superimpose the chains to maximize the overlap between the hydrophobic residues, the U turn, and the C-terminal and N-terminal regions. For example, hydrophobic residues in the L13ANFL17 motif of the β1 region of amylin are matched with the hydrophobic residues L17VFFA21 in Aβ (Figure 1B), and the hydrophobic A25ILSS29 motif in the β2 region of amylin is matched with the hydrophobic residues A30IIGL34 in the β2 region of Aβ (Figure 1B). Face-to-face interactions between β-sheets, usually hydrophobic contacts, are common in amyloid structure, but their role in the formation and stabilization of amyloid fibrils has been underappreciated.40,63 The U-shaped structures reveal such contact between residues V36/L17, L34/F19, and I32/A21 of Aβ, T30/N14, S28/L16, and I26/H18 for amylin (Figure 1C,D), and a combination of these face-to-face interactions in the Aβ15–40|amylin10–35 octamer heteroassembly.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Reliable simulations of structure and dynamics of large biomolecules require accurate and reliable force fields.64 A common choice for exploring amyloid peptide aggregation64,65 is the combination of the AMBER ff99SB force field66 with explicit water (TIP3P)67,68 used also in this study. We use the GROMACS program, version 4.5.3,69 and a time step of 2 fs. Hydrogen atoms are added with the pdb2gmx module of the GROMACS suite. The start configurations of all proteins are set in the center of a cubic box where the distance between the solute and the edge of the box is at least 12 Å. Periodic boundary conditions are employed, and electrostatic interactions are calculated with the PME algorithm.70,71 Hydrogen atoms are constrained with the LINCS72 algorithm, while for water, the Settle algorithm is used.73 The temperature of 310 K is kept constant by the Parrinello–Donadio–-Bussi algorithm74 (τ = 0.1 fs), which is similar to Berendsen coupling but adds a stochastic term that ensures a proper canonical ensemble.74,75 In a similar way, the pressure is kept constant at 1 bar by the Parrinello–Rahman algorithm76 (τ = 1 fs). The temperature of 310 K is chosen as a compromise between preserving the experimentally observed stability of the amyloid fibrils77 and the desire to enhance sampling by raising temperature.78,79 The solvated start configuration is first energy minimized using the steepest descent method, followed by conjugate gradient. Afterward, the system is equilibrated in two steps of 500 ps, the first step in an NVT ensemble and the second phase in an NPT ensemble at 1 bar. After equilibrization, 300 ns of trajectories are analyzed for each system to examine the structural changes of the oligomer aggregates with time. Data are saved at 4.0 ps intervals for further analysis. For each system (solely Aβ15–40, solely amylin10–35, and mixed Aβ15–40–amylin10–35), we run three distinct simulations of 300 ns with different initial velocity distributions. This allows us to test that we reached equilibrium and guarantees three independent sets of measurements.

The molecular dynamics trajectories are analyzed with the tool set of the GROMACS package. Especially, we monitor conformational changes and stability of the oligomer models through the time evolution of the root mean square deviations of the Cα atoms (RMSD), root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF), solvent accessible surface area (SASA), hydrophobic contact distances, hydrogen bonds, and D23–K28 salt bridges, measured with the g_hbond and g_dist modules in GROMACS. Hydrogen bonds are defined by a distance cut off between donor and acceptor of 0.36 nm and an angle cut off of 30°. Configurations are visualized using PyMOL.80

Free Energy Calculations

The binding energy between the tetramers that form the octameric oligomers (Figure S4, Supporting Information) are estimated with the MM-PBSA methodology as implemented in AMBER1181 using the same force field and water model as above. The free energy of a molecule in the MM-PBSA is computed as the sum of the molecular mechanics energy in the gas phase, the solvation free energy, and the conformational entropy. Conformational effects are taken into account by averaging over the ensemble of configuration as generated in the molecular dynamics simulations. From the free energies of tetramer 1 (A), tetramer 2 (B), and octamer complex (C), the binding free energy is computed by subtracting the first two from the latter one from a single simulation of the complex (Figure S4, Supporting Information).

The bracket ⟨⟩ indicates a trajectory average, and the free energy of each system X = A, B, or C is computed as a sum of the three terms:

Here, the molecular mechanics energy, EMM, is the sum of the internal energy (bonds, angles, and dihedrals; Eint), electrostatic energy (Eele), and van der Waals term (Evdw):

The solvation energy, ΔGsolv, can be divided into the polar and nonpolar part:

where the polar part, ΔGPB, describes the electrostatic contribution to solvation as obtained from Poisson–Boltzmann (PB) calculations in a continuum solvent model, and the nonpolar contribution, ΔGSA, is proportional to the solvent accessible surface area (SASA):

In our calculations, we use the AMBER11 default parameter for γ and b.

Acknowledgments

F.Y. thanks the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry for kind hospitality during his sabbatical stay at the University of Oklahoma.

Supporting Information Available

System set up for binding free energy calculation and additional results on structural flexibility, hydrogen bond content, salt bridge stability, and electrostatic contributions to the binding free energy. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

We acknowledge support from the National Institutes of Health (Grant Number GM62838). This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, which is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. Parts of the simulations were done on the BOOMER cluster of the University of Oklahoma. F.Y. is supported by Hacetttepe University Scientific Research Fund under Project Number 012.D12.602.001.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Stefani M. (2012) Structural features and cytotoxicity of amyloid oligomers: Implications in Alzheimer’s disease and other diseases with amyloid deposits. Prog. Neurobiol. 99, 226–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D.; Jucker M. (2012) The Amyloid State of Proteins in Human Diseases. Cell 148, 1188–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan P.; Ganzinger K. A.; McColl J.; Weimann L.; Meehan S.; Qamar S.; Carver J. A.; Wilson M. R.; George-Hyslop P. S.; Dobson C. M.; Klenerman D. (2013) Single Molecule Characterization of the Interactions between Amyloid-beta Peptides and the Membranes of Hippocampal Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1491–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolognesi B.; Kumita J. R.; Barros T. P.; Esbjorner E. K.; Luheshi L. M.; Crowther D. C.; Wilson M. R.; Dobson C. M.; Favrin G.; Yerbury J. J. (2010) ANS Binding Reveals Common Features of Cytotoxic Amyloid Species. ACS Chem. Biol. 5, 735–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R.; Head E.; Thompson J. L.; McIntire T. M.; Milton S. C.; Cotman C. W.; Glabe C. G. (2003) Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science 300, 486–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laganowsky A.; Liu C.; Sawaya M. R.; Whitelegge J. P.; Park J.; Zhao M. L.; Pensalfini A.; Soriaga A. B.; Landau M.; Teng P. K.; Cascio D.; Glabe C.; Eisenberg D. (2012) Atomic View of a Toxic Amyloid Small Oligomer. Science 335, 1228–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. W.; Breydo L.; Isas J. M.; Lee J.; Kuznetsov Y. G.; Langen R.; Glabe C. (2010) Fibrillar Oligomers Nucleate the Oligomerization of Monomeric Amyloid beta but Do Not Seed Fibril Formation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 6071–6079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C Z. M.; Jiang L.; Cheng P. N.; Park J.; Sawaya M. R.; Pensalfini A.; Gou D.; Berk A. J.; Glabe C. G.; Nowick J.; Eisenberg D. (2012) Out-of-register β-sheets suggest a pathway to toxic amyloid aggregates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 20913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott A.; Stolk R. P.; van Harskamp F.; Pols H. A. P.; Hofman A.; Breteler M. M. B. (1999) Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia - The Rotterdam Study. Neurology 53, 1937–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng G.; Huang C.; Deng H.; Wang H. (2012) Diabetes as a risk factor for dementia and mild cognitive impairment: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Intern. Med. J. 42, 484–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson J.; Laedtke T.; Parisi J. E.; O’Brien P.; Petersen R. C.; Butler P. C. (2004) Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in Alzheimer disease. Diabetes 53, 474–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Zhou B.; Deng B.; Zhang F.; Wu J. X.; Wang Y. G.; Le Y. Y.; Zhai Q. W. (2013) Amyloid-beta Induces Hepatic Insulin Resistance In Vivo via JAK2. Diabetes 62, 1159–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato N.; Morishita R. (2013) Plasma A beta: A Possible Missing Link Between Alzheimer Disease and Diabetes. Diabetes 62, 1005–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo A.; Razzaboni B.; Weir G. C.; Yankner B. A. (1994) Pancreatic-islet cell toxicity of amylin associated with type-2 diabetes-mellitus. Nature 368, 756–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppener J. W. M.; Ahren B.; Lips C. J. M. (2000) Islet amyloid and type 2 diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 343, 411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Nuallain B.; Williams A. D.; Westermark P.; Wetzel R. (2004) Seeding specificity in amyloid growth induced by heterologous fibrils. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 17490–17499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreetto E.; Yan L. M.; Tatarek-Nossol M.; Velkova A.; Frank R.; Kapurniotu A. (2010) Identification of Hot Regions of the A beta-IAPP Interaction Interface as High-Affinity Binding Sites in both Cross- and Self-Association. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 49, 3081–3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ida N.; Hartmann T.; Pantel J.; Schroder J.; Zerfass R.; Forstl H.; Sandbrink R.; Masters C. L.; Beyreuther K. (1996) Analysis of heterogeneous beta A4 peptides in human cerebrospinal fluid and blood by a newly developed sensitive Western blot assay. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 22908–22914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks W. A.; Kastin A. J.; Maness L. M.; Huang W. T.; Jaspan J. B. (1995) Permeability of the blood-brain-barrier to amylin. Life Sci. 57, 1993–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K.; Barisone G. A.; Diaz E.; Jin L. W.; DeCarli C.; Despa F. (2013) Amylin deposition in the brain: a second amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease?. Annals of Neurology 10.1002/ana.23956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasagna-Reeves C. A.; Glabe C. G.; Kayed R. (2011) Amyloid-beta Annular Protofibrils Evade Fibrillar Fate in Alzheimer Disease Brain. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 22122–22130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield S. M.; Lashuel H. A. (2010) Amyloidogenic Protein Membrane Interactions: Mechanistic Insight from Model Systems. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 49, 5628–5654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthes D.; Gapsys V.; de Groot B. L. (2012) Driving Forces and Structural Determinants of Steric Zipper Peptide Oligomer Formation Elucidated by Atomistic Simulations. J. Mol. Biol. 421, 390–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub J. E., and Thirumalai D. (2011) Toward a Molecular Theory of Early and Late Events in Monomer to Amyloid Fibril Formation. In Annual Review of Physical Chemistry (Leone S. R., Cremer P. S., Groves J. T., and Johnson M. A., Eds.), Vol 4, pp 437–463, Annual Reviews, Palo Alto, CA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M.; Hansmann U. H. E. (2011) Replica exchange molecular dynamics of the thermodynamics of fibril growth of Alzheimer’s A beta(42) peptide. J. Chem. Phys. 135, 065101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy G.; Straubb J. E.; Thirumalai D. (2009) Dynamics of locking of peptides onto growing amyloid fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 11948–11953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi W. H.; Li W. F.; Wang W. (2012) Template Induced Conformational Change of Amyloid-beta Monomer. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 7398–7405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng B. P.; Esler W. P.; Clish C. B.; Stimson E. R.; Ghilardi J. R.; Vinters H. V.; Mantyh P. W.; Lee J. P.; Maggio J. E. (1999) Deposition of monomeric, not oligomeric, A beta mediates growth of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid plaques in human brain preparations. Biochemistry 38, 10424–10431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Y.; Ma B. Y.; Nussinov R. (2011) Synergistic Interactions between Repeats in Tau Protein and A beta Amyloids May Be Responsible for Accelerated Aggregation via Polymorphic States. Biochemistry 50, 5172–5181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma B. Y.; Nussinov R. (2012) Selective Molecular Recognition in Amyloid Growth and Transmission and Cross-Species Barriers. J. Mol. Biol. 421, 172–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessalew N.; Mikre W. (2008) On the paradigm shift towards multitarget selective drug design. Curr. Comput.-Aided Drug Des. 4, 76–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins A. L. (2008) Network pharmacology: The next paradigm in drug discovery. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 682–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarell C. J.; Woods L. A.; Su Y. C.; Debelouchina G. T.; Ashcroft A. E.; Griffin R. G.; Stockley P. G.; Radford S. E. (2013) Expanding the Repertoire of Amyloid Polymorphs by Co-polymerization of Related Protein Precursors. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 7327–7337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarava N.; Ostapchenko V. G.; Savtchenko R.; Baskakov I. V. (2009) Conformational Switching within Individual Amyloid Fibrils. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14386–14395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson C. M. (1999) Protein misfolding, evolution and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24, 329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles T. P.; Fitzpatrick A. W.; Meehan S.; Mott H. R.; Vendruscolo M.; Dobson C. M.; Welland M. E. (2007) Role of intermolecular forces in defining material properties of protein nanofibrils. Science 318, 1900–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang G. Z.; Zhao J.; Yu X.; Zheng J. (2013) Comparative Molecular Dynamics Study of Human Islet Amyloid Polypeptide (IAPP) and Rat IAPP Oligomers. Biochemistry 52, 1089–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltzius J. J. W.; Sievers S. A.; Sawaya M. R.; Cascio D.; Popov D.; Riekel C.; Eisenberg D. (2008) Atomic structure of the cross-beta spine of islet amyloid polypeptide (amylin). Protein Sci. 17, 1467–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. H.; Liu H. L.; Liu Y. F.; Lin H. Y.; Fang H. W.; Ho Y.; Tsai W. B. (2009) Molecular Dynamics Simulations to Investigate the Aggregation Behaviors of the A beta(17–42) Oligomers. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 26, 481–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin-Nan Cheng J. D. P.; Nowick J. S. (2013) The Supramolecular Chemistry of β-Sheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 5477–5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya M. R.; Sambashivan S.; Nelson R.; Ivanova M. I.; Sievers S. A.; Apostol M. I.; Thompson M. J.; Balbirnie M.; Wiltzius J. J. W.; McFarlane H. T.; Madsen A. O.; Riekel C.; Eisenberg D. (2007) Atomic structures of amyloid cross-beta spines reveal varied steric zippers. Nature 447, 453–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkova A. T.; Yau W. M.; Tycko R. (2006) Experimental constraints on quaternary structure in Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid fibrils. Biochemistry 45, 498–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchete N. V.; Tycko R.; Hummer G. (2005) Molecular dynamics simulations of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid protofilaments. J. Mol. Biol. 353, 804–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homeyer N.; Gohlke H. (2012) Free Energy Calculations by the Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area Method. Mol. Inf. 31, 114–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhanu W. M.; Masunov A. E. (2011) Molecular Dynamic Simulation of Wild Type and Mutants of the Polymorphic Amyloid NNQNTF Segments of Elk Prion: Structural Stability and Thermodynamic of Association. Biopolymers 95, 573–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohlke H.; Case D. A. (2004) Converging free energy estimates: MM-PB(GB)SA studies on the protein-protein complex Ras-Raf. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 238–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workalemahu M.; Berhanu U. H. E. H. (2013) The stability of cylindrin β-barrel amyloid oligomer models – a molecular dynamics study. Proteins 81, 1542–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.; Kahng B.; Hwang W. (2009) Thermodynamic Selection of Steric Zipper Patterns in the Amyloid Cross-beta Spine. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F. F.; Liu Z.; Bai S.; Dong X. Y.; Sun Y. (2012) Exploring the inter-molecular interactions in amyloid-beta protofibril with molecular dynamics simulations and molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area free energy calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 136, 145101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda T.; Klimov D. K. (2009) Probing the Effect of Amino-Terminal Truncation for A beta(1–40) Peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 6692–6702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Jang H.; Ma B.; Tsai C. J.; Nussinov R. (2007) Modeling the Alzheimer A beta(17–42) fibril architecture: Tight intermolecular sheet-sheet association and intramolecular hydrated cavities. Biophys. J. 93, 3046–3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damjanovic A.; Schlessman J. L.; Fitch C. A.; Garcia A. E.; Garcia-Moreno B. (2007) Role of flexibility and polarity as determinants of the hydration of internal cavities and pockets in proteins. Biophys. J. 93, 2791–2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud J. C.; Liu C.; Teng P. K.; Eisenberg D. (2012) Toxic fibrillar oligomers of amyloid-beta have cross-beta structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 7717–7722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang H.; Connelly L.; Arce F. T.; Ramachandran S.; Kagan B. L.; Lal R.; Nussinov R. (2013) Mechanisms for the Insertion of Toxic, Fibril-like beta-Amyloid Oligomers into the Membrane. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 822–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanga R. P. R.; Brender J. R.; Vivekanandan S.; Ramamoorthy A. (2011) Structure and membrane orientation of IAPP in its natively amidated form at physiological pH in a membrane environment. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 1808, 2337–2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna M.; C M. (2013) Binding, Conformational Transition and Dimerization of Amyloid-b Peptide on GM1-Containing Ternary Membrane: Insights from Molecular Dynamics Simulation. PLoS One 8, e71308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers S. A.; Karanicolas J.; Chang H. W.; Zhao A.; Jiang L.; Zirafi O.; Stevens J. T.; Munch J.; Baker D.; Eisenberg D. (2011) Structure-based design of non-natural amino-acid inhibitors of amyloid fibril formation. Nature 475, 96–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Liu C.; Sawaya M. R.; Vadla B.; Khan S.; Woods R. J.; Eisenberg D.; Goux W. J.; Nowick J. S. (2012) Macrocyclic β-Sheet Peptides That Inhibit the Aggregation of a Tau-Protein-Derived Hexapeptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17832–17832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K.; Condron M. M.; Teplow D. B. (2009) Structure-neurotoxicity relationships of amyloid beta-protein oligomers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 14745–14750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhrs T.; Ritter C.; Adrian M.; Riek-Loher D.; Bohrmann B.; Doeli H.; Schubert D.; Riek R. (2005) 3D structure of Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta(1–42) fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 17342–17347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz Y.; Y M. (2013) Interactions between Aβ and Mutated Tau Lead to Polymorphism and Induce Aggregation of Aβ-Mutated Tau Oligomeric Complexes. PLoS ONE 8, e73303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colletier J. P.; Laganowsky A.; Landau M.; Zhao M. L.; Soriaga A. B.; Goldschmidt L.; Flot D.; Cascio D.; Sawaya M. R.; Eisenberg D. (2011) Molecular basis for amyloid-beta polymorphism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 16938–16943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda T.; Klimov D. K. (2009) Probing Energetics of A beta Fibril Elongation by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Biophys. J. 96, 4428–4437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhanu W. M.; Hansmann U. H. E. (2012) Structure and Dynamics of Amyloid-b Segmental Polymorphisms. PLoS ONE 7, e41479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndlovu H.; Ashcroft A. E.; Radford S. E.; Harris S. A. (2012) Effect of Sequence Variation on the Mechanical Response of Amyloid Fibrils Probed by Steered Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Biophys. J. 102, 587–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornak V.; Abel R.; Okur A.; Strockbine B.; Roitberg A.; Simmerling C. (2006) Comparison of multiple amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins 65, 712–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariae U.; Schneider R.; Briones R.; Gattin Z.; Demers J. P.; Giller K.; Maier E.; Zweckstetter M.; Griesinger C.; Becker S.; Benz R.; de Groot B. L.; Lange A. (2012) beta-Barrel Mobility Underlies Closure of the Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel. Structure 20, 1540–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutzner C.; Grubmuller H.; de Groot B. L.; Zachariae U. (2011) Computational Electrophysiology: The Molecular Dynamics of Ion Channel Permeation and Selectivity in Atomistic Detail. Biophys. J. 101, 809–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronk S.; Páll S.; Schulz R.; Larsson P.; Bjelkmar P.; Apostolov R.; Shirts M. R.; Smith J. C.; Kasson P M.; van der Spoel D.; Hess B.; Lindahl E. (2013) GROMACS 4.5: a high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics 29, 845–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darden T.; York D.; Pedersen L. (1993) Particle mesh ewald - an n. log(n) method for ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- Essmann U.; Perera L.; Berkowitz M. L.; Darden T.; Lee H.; Pedersen L. G. (1995) A smooth particle mesh ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- Hess B. (2008) P-LINCS: A parallel linear constraint solver for molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4, 116–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S.; Kollman P. A. (1992) Settle - an analytical version of the shake and rattle algorithm for rigid water models. J. Comput. Chem. 13, 952–962. [Google Scholar]

- Bussi G.; Donadio D.; Parrinello M. (2007) Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 014101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussi G.; Zykova-Timan T.; Parrinello M. (2009) Isothermal-isobaric molecular dynamics using stochastic velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 130, 074101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrinello M.; Rahman A. (1981) Polymorphic transitions in single-crystals - a new molecular-dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 7182–7190. [Google Scholar]

- Meersman F.; Dobson C. M. (2006) Probing the pressure-temperature stability of amyloid fibrils provides new insights into their molecular properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1764, 452–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhanu W. M.; Masunov A. E. (2012) Controlling the aggregation and rate of release in order to improve insulin formulation: molecular dynamics study of full-length insulin amyloid oligomer models. J. Mol. Model. 18, 1129–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhanu W. M.; Masunov A. E. (2012) Unique example of amyloid aggregates stabilized by main chain H-bond instead of the steric zipper: Molecular dynamics study of the amyloidogenic segment of amylin wild-type and mutants. J. Mol. Model. 18, 891–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano W. L. (2002) PyMOL molecular graphics system, version 1.3.0.4, Schrödinger, LLC.

- Miller B. R.; McGee T. D.; Swails J. M.; Homeyer N.; Gohlke H.; Roitberg A. E. (2012) MMPBSA.py: An Efficient Program for End-State Free Energy Calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 3314–3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.