Abstract

Interleukin-16 (IL-16) is a multifunctional cytokine that has been associated with autoimmune and allergic diseases. To investigate comprehensively whether IL-16 is also associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and emphysema, we performed an integrated analysis of multiple “omics” data. Over 500 subjects participating in the COPDGene® study donated blood and were clinically characterized and genetically profiled. IL-16 mRNA levels were measured in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), and protein levels were measured in fresh frozen plasma. A multivariate analysis found plasma IL-16 positively associated with age and body mass index, and negatively associated with current smoking and emphysema in the upper lobes. PBMC IL-16 expression was positively associated with gender and a composite score for airflow obstruction, emphysema, and gas trapping. Whole-genome expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) analysis identified a novel IL-16 missense SNP (rs11556218) associated with lower IL-16 in plasma. In summary, an integrated “omics” analysis in a very large cohort identified an association between decreased IL-16 and emphysema and discovered a novel IL-16 cis-eQTL. Thus IL-16 plasma levels and IL-16 genotyping may be useful in a personalized medicine approach for lung disease.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) develops in only 25%–40% of cigarette smokers (Lokke et al., 2006). The pathophysiologic factors postulated to determine which of these smokers develop disease include: inflammation, oxidant/antioxidant imbalance, unopposed protease activity, autoimmunity, and enhanced apoptosis (Bowler et al., 2004). The role of cytokines in driving lung and systemic inflammation has generated much interest, and many studies are attempting to identify plasma cytokines that could serve as biomarkers for COPD. The ideal cytokine biomarker of COPD would be detectable in plasma, change with COPD severity, and play a role in the pathogenesis of disease. One such cytokine that may fulfill some of these criteria is interleukin-16 (IL-16) (Cruikshank et al., 2000).

Interleukin-16 (IL-16), formerly called lymphocyte chemoattractant factor, is an immune modulator that is a chemoattractant for CD4+ cells, monocytes, and eosinophils (Cruikshank et al., 2000). The IL-16 gene (IL16) maps to chromosome 15q26.3. IL-16 mRNA is present almost exclusively in leukocytes (Baier et al., 1997). IL-16 protein is secreted as a 631-amino-acid precursor that is cleaved by caspase-3 (Zhang et al., 1998) and can stimulate the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (Mathy et al., 2000). Both immune and non-immune cells produce IL-16, including T-cells, eosinophils, dendritic cells, fibroblasts, epithelial cells, and neuronal cells (Cruikshank et al., 2000). Although IL-16 plasma levels have been associated with diverse diseases, such as AIDS (Jin et al., 2009) and Alzheimer's disease (Motta et al., 2007), the majority of literature has focused on the role of IL-16 allergic, airways, and autoimmune diseases (Lard et al., 2002).

IL-16 gene expression has been associated with increased CD4+ T-cell infiltration in patients with atopic dermatitis (Laberge et al., 1998). Patients with allergic rhinitis also have elevated nasal IL-16 expression which is exacerbated during allergy season and depressed by corticosteroid therapy (Pullerits et al., 2001). In mice, allergic rhinitis-induced increases in IL-16 can also be attenuated by fexofenadine and ramatroban (Akiyama et al., 2009). Although a correlation between plasma IL-16 levels and asthma has not been reported, increased airway IL-16 has been associated with severe asthma (Burkart et al., 2006). IL-16 has also been associated with asthma in genetic studies (Burkart et al., 2006). In addition, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) IL-16 increases in patients with asthma after exposure to an allergen (Krug et al., 2000). Two small studies of chronic bronchitis and COPD suggest a possible relationship between IL-16 and COPD. In a study of 33 smokers, BALF IL-16 was reported to be elevated with chronic bronchitis (Andersson et al., 2004) and in a study of 152 COPD patients and 80 controls, plasma IL-16 was lower in males with COPD, but there was no adjustment for potential confounding factors other than gender (de Torres et al., 2011). This study did not investigate emphysema and we are unaware of any studies investigating differences of IL16 mRNA in peripheral blood gene expression. We are also unaware of any studies identifying quantitative trait locus of expression (eQTL) for IL-16.

In addition to allergic inflammation, IL-16 has been associated with autoimmune diseases. For instance, rheumatoid arthritis is associated with increased IL-16 plasma levels (Kaufmann et al., 2001) and higher IL-16 in sera and synovial fluids compared to patients with osteoarthritis (Blaschke et al., 2001). Furthermore, high systemic levels of IL-16 at the initial presentation of RA are associated with greater joint destruction (Lard et al., 2004). Serum IL-16 is also higher in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients compared to healthy controls (Lard et al., 2002; Lee et al., 1998). In RA and SLE, increases in IL-16 are associated with disease activity and thought to be mediated by CD4+ cells. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) IL-16 is higher in patients with scleroderma (Duan et al., 2008).

Since COPD and emphysema share clinical features of asthma, and recent studies have suggested a role for CD4+ mediated-autoimmunity in the pathogenesis emphysema (Lee et al., 2007), we investigated whether IL-16 would be associated with COPD and emphysema using a multiple ‘omics' data in a large cohort of smokers.

Materials and Methods

Study subjects

This study was approved and reviewed by the institutional review board at participating institutions. Study participants provided written informed consent for clinical and genetic studies. 600 subjects were recruited from a subset of the COPDGene® study at two clinical centers: National Jewish Health (NJH) at Denver, Colorado, and University of Iowa (UIA), Iowa City, Iowa. (Regan et al., 2010). All subjects were studied under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board at NJH and UIA with guidelines by the National Institutes of Health. All subjects were non-Hispanic white (NHW) or African-American (AA) and had at least a 10-pack year smoking history and no respiratory symptoms or disease other than COPD. Subjects with >10 mg/day oral corticosteroids or change in corticosteroid dose in the previous 30 days were excluded. The diagnosis of COPD was made using Global initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria: post bronchodilator (BD) maximum volume of air expired in one second (FEV1) divided by forced vital capacity (FVC) less than 0.7 (Fabbri and Hurd, 2003). Reference values for spirometry were based on a sample of the general U.S. population (Hankinson et al., 1999). In those with COPD, severity of COPD was defined through FEV1%, or GOLD Stage (1–4 from least to most severe). All subjects had extensive clinical questionnaires, physical measurements, spirometry, and an inspiratory and expiratory high resolution CT (HRCT) scan (Regan et al., 2010). Quantitative HRCT measurements of emphysema, gas trapping, and airway wall thickening were made as described (Kim et al., 2011). A subject was defined as having emphysema if the lung attenuation area at −950 Houndsfeld Units was <5%. In longitudinal follow up, subjects were contacted every 6 months (average 2.5 years follow up) to assess prospectively moderate or severe (requiring hospitalization) COPD exacerbations. An exacerbation was defined as a respiratory illness that required the use of antibiotic, steroids, or hospitalization.

IL-16 plasma measurement

Eight and a half mL of blood were withdrawn from the antecubital vein into a sterile 13×1000 mm P100 Blood Collection Tube (BD, New Jersey, USA). The sample was immediately spun at 2500 g for 20 min at room temperature. The sample was placed into 500 μL aliquots and stored at −80°C. In a pilot study of 15 controls and 15 subjects with emphysema that used a Luminex discovery platform (Myriad RBM, Texas), we identified plasma IL-16 as a potential biomarker of emphysema. For the validation phase, IL-16 plasma levels were measured using the Human IL-16 Immunoassay Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Mn) in 541 subjects selected randomly from COPDGene®. The ELISA kit was used according to the instructions provided by R&D Systems, and the standard curve was calculated using 4-parameter nonlinear regression. All of the samples were assayed in duplicate. Log transformed IL-16 plasma levels were used for all studies.

IL-16 gene expression in PBMCs

RNA peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained from 214 of the 600 participants using a Vacutainer Cell Preparation Tube (BD, New Jersey). RNA isolation was performed in a QIAcube automated protocol using RNeasy RNA isolation spin-column kits (Qiagen, Duesseldorf, Germany). RNA purity and integrity were assessed and only samples with A260/A280 absorbance ratios between 1.8 and 2.1 and an integrity number above 7 were considered acceptable. Subjects were selected for expression profiling based on a random selection of available samples that balanced the demographic and clinical covariates (e.g., severity of COPD, gender, current smoking status, BMI, and parental history of COPD). IL-16 was assessed using two platforms: 138 subjects had IL-16 gene expression determined from three probe sets using U133 plus 2.0 microarrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, USA; GEO accession number GSE 42057), 149 subjects on an Applied Biosystems OpenArray® platform (RT-qPCR), and 73 subjects had IL-16 assessed on both platforms. The microarray platform was used for a genome-wide study to identify candidate genes, including 1L-16, which were further validated using the RT-qPCR platform on additional subjects; see Bahr et al. (2013) for more details.

For the subjects profiled by microarray, the sample size by GOLD stage was GOLD 0 (n=42), GOLD 1 (n=8), GOLD 2 (n=34), GOLD 3 (n=25), and GOLD 4 (n=17), and for the subjects profiled by RT-qPCR, the breakdown was GOLD 0 (n=65), GOLD 1 (n=13), GOLD 2 (n=27), GOLD 3 (n=22), and GOLD 4 (n=15). The subjects profiled between the two platforms were not significantly different in GOLD stage (Chi-square test, p=0.18). For the subjects profiled by microarray, the mean and standard deviation (in parenthesis) for percent emphysema by GOLD stage was GOLD 0 [1.4 (1.5)], GOLD 1 [5.6 (6.0)], GOLD 2 [6.0 (6.9)], GOLD 3 21.5 (10.9)], and GOLD 4 [22.1 (9.3)], and for the subjects profiled by RT-qPCR percent emphysema by GOLD stage was GOLD 0 [1.2 (1.3)], GOLD 1 [4.1 (4.4)], GOLD 2 [6.7 (6.1)], GOLD 3 [20.3 (12.3)], and GOLD 4 [28.6 (16.3)]. For each of the GOLD stages, there was no significant difference in the mean percent emphysema for the two groups (two sample t-test) using either the complete number of subjects or the non-overlapping subjects (P>0.17).

IL-16 measurements on Affymetrix platform

Raw data collected from the DNA microarray assay was assessed for quality, log transformed, normalized using the RMA normalization algorithm (Bolstad et al., 2003), and modeled using multiple linear regression. The regression model included disease severity measured by FEV1% as the dependent variable, normalized gene expression values as the primary independent variable, and seven covariates to account for possible confounding (age, sex, BMI, current smoking status, lifetime pack years, and family history of COPD). Estimated regression coefficients for Il-16 gene expression were recorded, and a t-test was performed on each coefficient (slope). More details are provided in Bahr et al. (2013).

IL-16 assessment on OpenArray® platform

Normalization was performed using the geometric mean of a select group of controls (Mar et al., 2009). Control genes were evaluated using methodology described in (Vandesompele et al., 2002) and out of ten possible controls (ACTB, B2M, GAPD, GUSB, HPRT1, PGK1, PPIA, RPL30, TBP, and TFRC) the best five controls (GUSB, GAPDH, HPRT1, B2M, and RPL30) were selected based upon having an internal control gene stability measure of less than 0.10. The geometric mean of these controls was then calculated to create a normalization factor (nfCt) for each subject (Vandesompele et al., 2002). The dCt value was then calculated as the difference in gene Ct vs. nfCt. As growth is exponential, the final metric was calculated 2-dCt which is the fold change of the gene's expression compared to the control (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). More details are provided in Bahr et al. (2013).

eQTL analysis

Samples from self-described European whites were genotyped at the Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR) at Johns Hopkins University using the Illumina Omni1 Quad platform quality-control procedure (available on dbGaP Study Accession phs000179.v3.p2) as previously described (Cho et al., 2012). Linear regression for IL-16 by genotype was performed using PLINK v 1.07 with covariates included age, gender, pack-years, body mass index (BMI), and the first five principal components from the entire COPDGene® genotyping dataset to account for population stratification. Only SNPs with mean allele frequency of at least 1% were studied.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed with the statistical software SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) (R and R Development Core Team 2008). The two-sample t-test was used to compare means of normally distributed data, and the Chi squared test for dichotomous outcomes was used for categorical variables. The Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test was used for smaller groups with large variation or data that was not normally distributed. Multiple regression included variables that were significant at p value <0.05. Regression models were assessed for collinearity using the variance inflation factor, condition indices, and variation proportions. When there was evidence of significant collinearity among model variables (e.g., FEV1%, emphysema, and gas trapping), we performed a principle component analysis of those variables and then used the principle components with eigenvectors >1.

Results

Study population

The COPD and control subjects were similar to controls for age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and smoking status (current or former); however, the average pack-years were higher for COPD subjects (Table 1). Of the 332 COPD subjects, 56 were GOLD 1, 132 were GOLD 2, 95 were GOLD 3, and 49 were GOLD 4. Because the vast majority of subjects reported race as non-Hispanic White and concerns for population stratification, African-Americans were excluded from eQTL analysis. Quantitative high resolution CT (HRCT), questionnaire data, and rates of prospective acute exacerbations of COPD during longitudinal follow up are shown in Supplementary Table S1 (supplementary data are available online at wwwliebertpub.com/omi). Demographics for subjects with and without emphysema are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Table 1.

Cohort Characteristics

| No COPD (N=268) | COPD (N=332) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60.9±8.6 | 63.0±8.6 | 0.0026 |

| Gender (% Male) | 49% | 54% | 0.1641 |

| Race (% Non-Hispanic White) | 84% | 94% | 0.0001 |

| BMI | 28.9±5.6 | 27.9±5.9 | 0.0256 |

| Current smoker | 41% | 34% | 0.0799 |

| Pack years | 40.9±26.2 | 51.4±27.4 | 0.0001 |

| FEV1 (%) | 95±14 | 56±23 | N/A |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.76±0.05 | 0.50±0.14 | N/A |

N/A, not applicable; p value for No COPD compared to COPD.

Effect of COPD phenotypes on IL-16 plasma levels

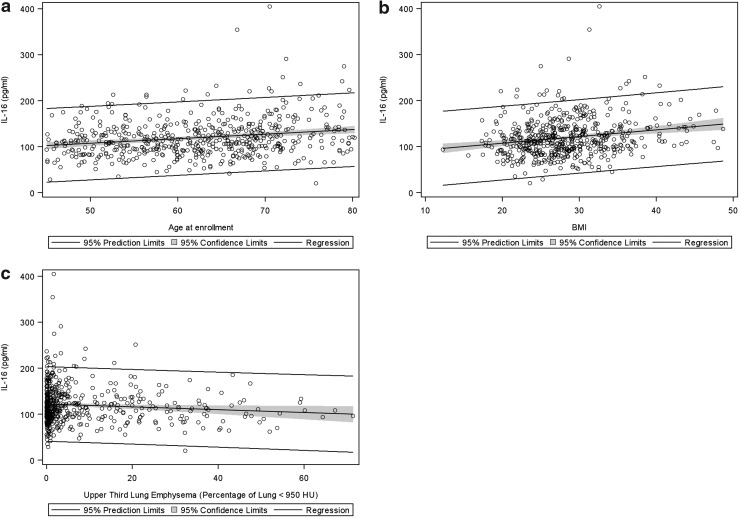

Most plasma IL-16 levels ranged from 100–200 pg/ml, which is consistent with other recent reports (Goihl et al,. 2012). In the univariate analysis (Supplementary Table S3), higher IL-16 plasma levels were associated with age, elevated BMI, and upper lobe emphysema (Fig. 1). IL-16 was also associated with reduced 6-min walk distance, having a history of asthma, being a former smoker, and thickened airway walls (Supplementary Table S3). Although smaller studies have reported interactions between COPD and gender for plasma IL-16 concentrations (de Torres et al., 2011), we found no significant interaction for either gender and COPD (p=0.05), gender and GOLD stage (p=0.13), or gender and emphysema (p=0.34). In the multivariate model, age, being a current smoker, a history of asthma, BMI, and emphysema were all independently associated with plasma IL-16 (Table 2). IL-16 levels at the time of enrollment in COPDGene® did not predict either moderate or severe exacerbations of COPD (p=0.78 and 0.42, respectively).

FIG. 1.

Plasma IL-16 association with clinical variables. (a) age; (b) BMI; and (c) emphysema in the upper lobes. Regression line and 95% confidence intervals are shown.

Table 2.

Multiple Regression for Plasma IL-16

| Variable | Parameter estimate | P |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.00507±0.00195 | 0.0096 |

| Current smoker | −0.08872±0.03585 | 0.0137 |

| History of asthma | 0.09584±0.04170 | 0.0220 |

| BMI | 0.00728±0.00292 | 0.0129 |

| 6 min. walk distance (ft) | 0.00002982±0.00004591 | 0.5164 |

| Emphysema, upper lung (%) | −0.00443±0.00140 | 0.0017 |

| Wall area % (segmental) | 0.00758±0.00549 | 0.1681 |

Effect of corticosteroids on IL-16 plasma concentrations

Fourteen subjects reported that they were using oral corticosteroids regularly at stable doses less than 10 mg per day at the time of enrollment (Supplementary Table S1). The 14 subjects on corticosteroids had significantly higher mean plasma IL-16 levels compared to those not on oral corticosteroids (145±13 pg/mL vs. 119±2 pg/mL; p=0.0212). There were no differences in plasma IL-16 levels for those on inhaled corticosteroids. Results from multivariate analysis were similar when the 14 subjects on low dose oral corticosteroids were excluded.

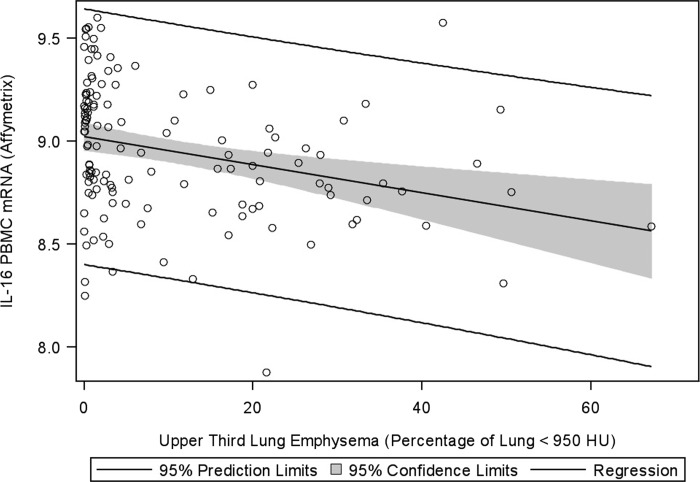

COPD phenotypes associated with IL-16 gene expression in PBMCs

IL-16 PBMC gene expression was measured on 214 subjects using either Affymetrix or OpenArray platform (see Materials and Methods). 73 subjects had IL-16 gene expression measured on both platforms; there was a good correlation between platforms (Pearson r=0.46; p<0.0001). Pearson's correlation between IL-16 plasma concentrations and PBMC IL-16 gene expression were not significant (p=0.20 for Affymetrix platform and p=0.21 for OpenArray platform). In the univariate analysis on both platforms, females had higher IL-16 gene expression but lower expression was noted with worse airflow limitation (lower FEV1/FVC), emphysema, and gas trapping (Supplementary Table S3 and Fig. 2). PBMC IL-16 expression at the time of COPDGene® enrollment was predictive of neither moderate nor severe exacerbations upon longitudinal follow up.

FIG. 2.

IL-16 gene expression is inversely associated with upper lobe emphysema in PBMCs. Shown are (log) data from the Affymetrix platform. Regression line and 95% confidence interval are shown.

Because multiple measurements of airflow limitation, emphysema, and air trapping demonstrated high degrees of co-linearity and small sample size, we performed a principle component analysis using measures of airflow obstruction, emphysema, and air trapping before performing multiple regression. Only the first principle component (explaining 81% of the variation) had an eigenvalue >1 and was significantly associated with IL-16 PBMC gene expression on both the Affymetrix (Supplementary Fig. S1) and OpenArray (not shown) platforms. On both platforms only the first principal component and gender remained in the model with total R2=0.10 for Affymetrix platform and R2=0.06 for OpenArray platform (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multiple Regression for IL-16 in PBMC

| Affymetrix P | OpenArray P | |

|---|---|---|

| Principle component 1 | 0.003 | 0.103 |

| Gender | 0.067 | 0.037 |

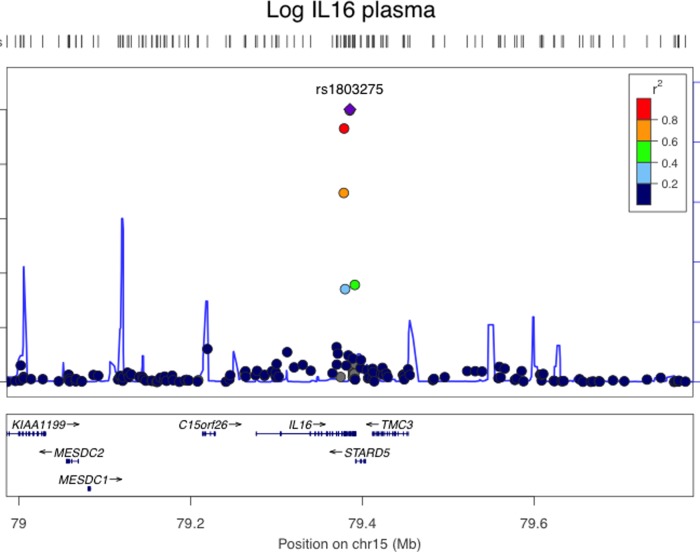

eQTL for IL-16

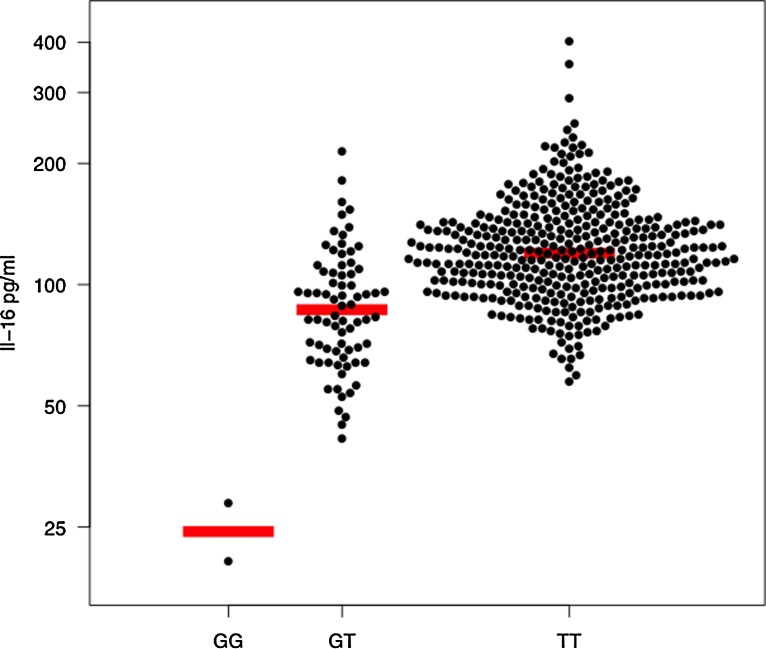

In our eQTL analysis of plasma, we identified six SNPs in chromosome 15q26.3 that met genome wide significance after adjustment for covariates (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table S4). All of the eQTL SNPs were in cis, adjacent, and had high degrees of linkage disequilibrium. The most significant association between a SNP and IL-16 plasma level was for rs1803275 (ancestral allele G; minor allele A; p<10−25 adjusted), which is a synonymous SNP at mRNA position +3949 and amino acid 1196 of pro-interleukin-16 isoform 2. A second adjacent SNP (rs11556218) was also highly associated with IL-16 plasma (p=10−25 adjusted) and was in strong linkage disequilibrium with rs1803275. The rs11556218 SNP is a missense polymorphism (G- >T) at mRNA position +3801 resulting in an Asn->Lys amino acid substitution at amino acid 1147. Subjects who had two copies of the ancestral allele (GG) had mean log IL-16 plasma of 4.80±0.28 pg/mL versus those with one copy of the minor allele (GT) for or two copies of the minor allele (TT), who had mean log IL-16 plasma of 4.46±0.34 and 3.19±0.23 pg/mL, respectively (p<0.0001; Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Regional plot on chromosome 15q26.3 of SNPs associated with plasma IL-16 concentrations. The purple diamond indicates the top SNP, which has the strongest evidence of association. Each circle shows a SNP with a color scale relating the r2 value for that SNP and the top SNP from HapMap CEU (Build Hg19). Blue lines indicate estimated recombination rates from HapMap. The bottom panels illustrate the relative position of genes near each locus. Candidate genes are indicated with directional arrows.

FIG. 4.

Plasma IL-16 concentration by genotype. Each circle represents a single measurement of log plasma IL-16. Horizontal line indicates median.

Discussion

Emphysema is a debilitating chronic disease with few systemic biomarkers other than α1-antitypsin. In the current investigation, we are the first to identify IL-16 as a biomarker of emphysema. Our approach is unique in that it included a multiple omics biomarker discovery strategy (plasma protein, PBMC gene expression, and genetics). Furthermore, we are the first to identify a genetic locus associated with plasma IL-16.

Although the mechanisms by which IL-16 may contribute to the pathogenesis of emphysema are unknown, there are several compelling reasons why IL-16 might be a good candidate biomarker for COPD and emphysema. First, IL-16 is pro-inflammatory in Th1 cells (e.g., IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α) (Mathy et al., 2000), but is suppressive of Th2 cytokines (e.g., IL-5) (McFadden et al., 2007). Second, IL-16 is expressed both in lymphocytes (Kaser et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 1998) as well as bronchial epithelium (Laberge et al., 1997). Third, emphysema has recently been postulated to have an autoimmune etiology (Lee et al., 2007) and IL-16 has been associated with autoimmune disorders such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. Finally, IL-16 has been implicated in playing a role in asthma (Lee et al., 2007).

In recent years there have been multiple in vitro and in vivo reports that have identified IL-16 as an immune modulating protein. In BALF, IL-16 has been shown to be a major lymphocyte chemoattractant (Cruikshank et al., 1995). IL-16 induces eosinophils to make leukotriene C4 (LTC4), RANTES, eotaxin, and can induce eosinophil migration (Ferland et al., 2004), but is also chemotactic for mast cells/basophils (Qi et al., 2006) and may affect macrophages function (Ghigo et al., 2010). Recent studies suggest that IL-16 dampens Th2 responses (e.g., IL-5 and IL-13) in response to allergen stimulation of PBMCs (El Bassam et al., 2006). Thus, IL-16 may be negative feedback for Th2-induced airway inflammation and may be a good marker for Th2 type airways diseases such as asthma. Alternatively, the low IL-16 may reflect negative feedback from activation of the Th1 response that has been described patients with emphysema (Lee et al., 2007). Because this is a cross-sectional study, we cannot rule out the possibility that IL-16 is a marker of another systemic disease, but we have made an effort to avoid confounding factors by randomly selected subjects and trying to balance the selection with respect to covariates such as gender and smoking status, which we found were associated with IL-16 expression.

In this study, there are several findings that suggest that the role of IL-16 in emphysema may be different from asthma. First, in contrast to asthma studies, we found that subjects with emphysema had decreased IL-16 protein in plasma and decreased Il-16 mRNA expression in PBMCs. Second, we found that IL-16 was associated with neither airway wall thickness nor exacerbations of COPD. This observation would tend to favor the “British Hypothesis” that asthma and COPD (in particular, emphysema) are distinct diagnoses as opposed to the Dutch hypothesis, which postulates that the two diseases are related through a continuum of airway inflammation (Barnes, 2006). Although the role that IL-16 might play in emphysema and COPD is unknown, one possibility is that it is related to autoimmunity, which has recently been shown to be important in the pathogenesis of emphysema.

A role for IL-16 in autoimmune diseases has recently been suggested for systemic lupus erythmatosus (SLE) (Lard et al., 2002; Lee et al., 1998), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (Blaschke et al., 2001; Lard et al., 2004); bullous pemphigoid (Frezzolini et al., 2004), diabetes (Meagher et al., 2010), and preeclampsia (Gu et al., 2008). In a mouse model of rheumatoid arthritis, IL-16 attenuates joint inflammation (Klimiuk et al., 1999). However, IL-16 plasma levels are elevated during RA and SLE flare-ups in humans, suggesting that IL-16 may play a regulatory role rather than a pathogenic role (Blaschke et al., 2001; Lard et al., 2002; 2004; Lee et al. 1998). Adoptive transfer experiments of IL-16 expressing CD8+ (suppressor) cells result in a marked reduction of autoimmunity in rheumatoid synovitis (Klimiuk et al., 1999). Since we and others have recently reported that patients with emphysema have autoimmune features (Lee et al., 2007; Packard et al., 2013), these findings might suggest that a loss of IL-16 secreting T-cells might play a role in the autoimmune pathogenesis of emphysema.

Since IL-16 is emerging as a potential biomarker for respiratory and autoimmune diseases, we investigated whether there are any eQTLs for IL-16 plasma. To our knowledge, there have been only a few small eQTL studies for IL-16 mRNA and no large studies of eQTLs for plasma IL-16. Two small studies investigated the role of cis-SNPs: a T→C SNP at the −295 position in the promoter region of IL16 has been reported to associated with increase promoter activity and with asthma (Burkart et al., 2006); however, a different study did not demonstrate the association between either asthma disease severity or atopy in a large Australian Caucasian population (Akesson et al., 2005). A small study of 166 Chinese subjects with colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, or controls reported no association between six IL-16 SNPs (including rs11446218) and IL-16 serum levels (Gao et al., 2009); however, this study likely suffered from population stratification, small sample size, and the median reported IL-16 serum concentration was 7.09 ng/mL, which is nearly 50-fold higher than typically reported. To our knowledge, this is the first report that identifies an eQTL for plasma IL-16. All six of the eQTL SNPs were clustered around one locus in the coding region of the gene and only one (rs11556218) was a mis-sense SNP (Asn->Lys amino acid substitution at amino acid 1147). Whether any of these SNPs are causally associated with low plasma IL-16 is unknown, but candidates for further investigation.

Conclusions

Using data collected from multiple “omics” technologies, this is the first comprehensive study in a large cohort to show that low IL-16 plasma and PBMC mRNA expression are associated with emphysema independent of other confounding variables such as age, gender, and BMI. Although the mechanism remains unknown, we suggest that it may be related to autoimmunity. Taking advantage of the parent COPDGene® study, this is also the first study to perform genome-wide quantitative trait loci analysis to identify eQTLs SNPs for plasma IL-16. These SNPs are candidate loci that should be investigated in COPD and emphysema, in addition to other diseases for which IL-16 is postulated to play a role.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in one second

- FVC

forced vital capacity

- GWAS

genome-wide association study

- IL-16

interleukin-16

- NAS

normative aging study

- NETT

national emphysema treatment trial

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphisms

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kiel Butterfield for assistance with collection of plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. This study was supported by NIH R01 HL 09 543 and R01 HL 08 9897, in part by Colorado CTSA grant UL1 RR 02 5780 from NCRR/NIH and a Butcher Seed Grant.

All authors made a significant contribution to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and approved the final version to be published. RB was responsible for IRB submission, study design, statistical analysis, and manuscript preparation. JD contributed to the IL-16 measurements and writing of the manuscript. TB contributed to the generation and analysis of the IL-16 expression measurements in PBMC. GH performed the analysis of the OpenArray IL-16 measurements in PBMC. SL performed the eQTL analysis. YK contributed to study design, IL-16 measurements, and editing of the manuscript. CC contributed to the gene expression study. NR critically reviewed the mansucript. KK contributed to expression study design, the statistical analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Akesson LS. Duffy DL. Phelps SC. Thompson PJ. Kedda MA. A polymorphism in the promoter region of the human interleukin-16 gene is not associated with asthma or atopy in an Australian population. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:327–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama K. Karaki M. Kobayshi R. Dobashi H. Ishida T. Mori N. IL-16 variability and modulation by antiallergic drugs in a murine experimental allergic rhinitis model. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2009;149:315–322. doi: 10.1159/000205577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson A. Qvarfordt I. Laan M, et al. Impact of tobacco smoke on interleukin-16 protein in human airways, lymphoid tissue and T lymphocytes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;138:75–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02580.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahr TM. Hughes GJ. Armstrong A, et al. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;49:316–323. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0230OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baier M. Bannert N. Werner A. Lang K. Kurth R. Molecular cloning, sequence, expression, and processing of the interleukin-16 precursor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5273–5277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ. Against the Dutch hypothesis: Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are distinct diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:240–243. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2604008. discussion 243–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaschke S. Schulz H. Schwarz G. Blaschke V. Muller GA. Reuss-Borst M. Interleukin-16 expression in relation to disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:12–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad BM. Irizarry RA. Astrand M. Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler RP. Barnes PJ. Crapo JD. The role of oxidative stress in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Copd. 2004;1:255–277. doi: 10.1081/copd-200027031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkart KM. Barton SJ. Holloway JW, et al. Association of asthma with a functional promoter polymorphism in the IL16 gene. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho MH. Castaldi PJ. Wan ES, et al. A genome-wide association study of COPD identifies a susceptibility locus on chromosome 19q13. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:947–957. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruikshank WW. Kornfeld H. Center DM. Interleukin-16. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:757–766. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruikshank WW. Long A. Tarpy RE, et al. Early identification of interleukin-16 (lymphocyte chemoattractant factor) and macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha (MIP1 alpha) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of antigen-challenged asthmatics. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13:738–747. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.6.7576712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Torres JP. Casanova C. Pinto-Plata V, et al. Gender differences in plasma biomarker levels in a cohort of COPD patients: A pilot study. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan H. Fleming J. Pritchard DK, et al. Combined analysis of monocyte and lymphocyte messenger RNA expression with serum protein profiles in patients with scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1465–1474. doi: 10.1002/art.23451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Bassam S. Pinsonneault S. Kornfeld H. Ren F. Menezes J. Laberge S. Interleukin-16 inhibits interleukin-13 production by allergen-stimulated blood mononuclear cells. Immunology. 2006;117:89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri LM. Hurd SS. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD: 2003 update. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:1–2. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00063703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferland C. Flamand N. Davoine F. Chakir J. Laviolette M. IL-16 activates plasminogen-plasmin system and promotes human eosinophil migration into extracellular matrix via CCR3-chemokine-mediated signaling and by modulating CD4 eosinophil expression. J Immunol. 2004;173:4417–4424. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frezzolini A. Cianchini G. Ruffelli M. Cadoni S. Puddu P. De Pita O. Interleukin-16 expression and release in bullous pemphigoid. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;137:595–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02570.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao LB. Rao L. Wang YY, et al. The association of interleukin-16 polymorphisms with IL-16 serum levels and risk of colorectal and gastric cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:295–299. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghigo E. Barry AO. Pretat L, et al. IL-16 promotes T. whipplei replication by inhibiting phagosome conversion and modulating macrophage activation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13561. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goihl A. Rolle AM. Kahne T. Reinhold A. Wrenger S. Reinhold D. Methodologic issues in the measurement of interleukin-16 in clinical blood samples using immunoassays. Cytokine. 2012;58:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y. Lewis SF. Deere K. Groome LJ. Wang Y. Elevated maternal IL-16 levels, enhanced IL-16 expressions in endothelium and leukocytes, and increased IL-16 production by placental trophoblasts in women with preeclampsia. J Immunol. 2008;181:4418–4422. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankinson JL. Odencrantz JR. Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin CZ. Zhao Y. Zhang FJ, et al. Different plasma levels of interleukins and chemokines: Comparison between children and adults with AIDS in China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2009;122:530–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaser A. Dunzendorfer S. Offner FA, et al. B lymphocyte-derived IL-16 attracts dendritic cells and Th cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:2474–2480. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann J. Franke S. Kientsch-Engel R. Oelzner P. Hein G. Stein G. Correlation of circulating interleukin-16 with proinflammatory cytokines in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40:474–475. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.4.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YI. Schroeder J. Lynch D, et al. Gender differences of airway dimensions in anatomically matched sites on CT in smokers. COPD. 2011;8:285–292. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2011.586658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimiuk PA. Goronzy JJ. Weyand CM. IL-16 as an anti-inflammatory cytokine in rheumatoid synovitis. J Immunol. 1999;162:4293–4299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug N. Cruikshank WW. Tschernig T, et al. Interleukin-16 and T-cell chemoattractant activity in bronchoalveolar lavage 24 hours after allergen challenge in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:105–111. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.1.9908055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laberge S. Ernst P. Ghaffar O, et al. Increased expression of interleukin-16 in bronchial mucosa of subjects with atopic asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17:193–202. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.2.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laberge S. Ghaffar O. Boguniewicz M. Center DM. Leung DY. Hamid Q. Association of increased CD4+ T-cell infiltration with increased IL-16 gene expression in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:645–650. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lard LR. Roep BO. Toes RE. Huizinga TW. Enhanced concentrations of interleukin-16 are associated with joint destruction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:35–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lard LR. Roep BO. Verburgh CA. Zwinderman AH. Huizinga TW. Elevated IL-16 levels in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus are associated with disease severity but not with genetic susceptibility to lupus. Lupus. 2002;11:181–185. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu176sr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. Kaneko H. Sekigawa I. Tokano Y. Takasaki Y. Hashimoto H. Circulating interleukin-16 in systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:1334–1337. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.12.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH. Goswami S. Grudo A, et al. Antielastin autoimmunity in tobacco smoking-induced emphysema. Nat Med. 2007;13:567–569. doi: 10.1038/nm1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ. Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-delta delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokke A. Lange P. Scharling H. Fabricius P. Vestbo J. Developing COPD: A 25 year follow up study of the general population. Thorax. 2006;61:935–939. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.062802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mar J. Kimura Y. Schroder K, et al. Data-driven normalization strategies for high-throughput quantitative RT-PCR. BMC Bioinformat. 2009;10:110. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathy NL. Scheuer W. Lanzendorfer M, et al. Interleukin-16 stimulates the expression and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by human monocytes. Immunology. 2000;100:63–69. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden C. Morgan R. Rahangdale S, et al. Preferential migration of T regulatory cells induced by IL-16. J Immunol. 2007;179:6439–6445. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meagher C. Beilke J. Arreaza G, et al. Neutralization of interleukin-16 protects nonobese diabetic mice from autoimmune type 1 diabetes by a CCL4-dependent mechanism. Diabetes. 2010;59:2862–2871. doi: 10.2337/db09-0131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motta M. Imbesi R. Di Rosa M. Stivala F. Malaguarnera L. Altered plasma cytokine levels in Alzheimer's disease: Correlation with the disease progression. Immunol Lett. 2007;114:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard TA. Li QZ. Cosgrove GP. Bowler RP. Cambier JC. COPD is associated with production of autoantibodies to a broad spectrum of self-antigens, correlative with disease phenotype. Immunol Res. 2013;55:48–57. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8347-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullerits T. Linden A. Malmhall C. Lotvall J. Effect of seasonal allergen exposure on mucosal IL-16 and CD4+ cells in patients with allergic rhinitis. Allergy. 2001;56:871–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi JC. Wang J. Mandadi S, et al. Human and mouse mast cells use the tetraspanin CD9 as an alternate interleukin-16 receptor. Blood. 2006;107:135–142. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Regan EA. Hokanson JE. Murphy JR, et al. Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD. 2010;7:32–43. doi: 10.3109/15412550903499522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesompele J. De Preter K. Pattyn F, et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:RESEARCH0034. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Center DM. Wu DM, et al. Processing and activation of pro-interleukin-16 by caspase-3. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1144–1149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.