Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune demyelinating disorder of the central nervous system (CNS) with unknown etiology. Several studies have shown that demyelination in MS is caused by proinflammatory mediators and nitric oxide (NO), which is released by perivascular infiltrates and/or activated glial cells. Both endogenous NO released by microglia and astrocytes; and NO generated from exogenous NO donors are known to induce oligodendrocytes death. However, the molecular mechanism of oligodendroglial death is poorly understood. Here we explore the role of NO in modulating the expression of myelin-specific genes that leads to oligodendroglial death. We investigated the effect of NO on the expression of myelin basic protein (MBP), 2’,3’-cyclic nucleotide 3’-phosphodiesterase (CNPase), myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), and proteolipid protein (PLP) in human primary oligodendrocytes. Combination of IFN-γ and bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or double stranded RNA in the form of polyIC induced the production of NO and decreased the expression of myelin gene in human fetal mixed glial cultures. Either a scavenger of NO (PTIO) or an inhibitor of inducible nitric oxide synthase (L-NIL) abrogated (LPS+IFN-γ)- and polyIC-mediated suppression of myelin genes in human mixed glial cells. The role of NO was further corroborated by the inhibition of myelin gene expression in purified human oligodendroglia by several NO donors including SNP, NOC-7, SIN-1, and SNAP. This study illustrates a novel biological role of NO in down-regulating the expression of myelin genes preceding the death of oligodendrocytes.

Keywords: LPS, IFN-γ, polyIC, Nitric oxide, Oligodendrocytes, Myelin gene expression

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) in which myelin sheaths and the myelin producing cells, oligodendrocytes, are destroyed. From a clinical standpoint, MS symptoms are diverse, ranging from tremor, nystagmus, paralysis, and disturbances in speech and vision; it occurs primarily in early adult life with characteristic exacerbations and remissions [1]. Pathologically, it is identified by the presence of diffuse, discrete demyelinated areas, called plaques. Although the etiology of MS is not completely understood, studies of MS patients suggest that the observed demyelination in the CNS is a result of an autoimmune inflammation [1] and [2]. Consistently, demyelinated areas in the CNS of MS patients are associated with an inflammatory reaction orchestrated by activated T cells, macrophages, and endogenous glial cells (astroglia and microglia). Activated T cells, macrophages, and endogenous glial cells produce a variety of proinflammatory and neurotoxic factors such as NO [3]. There is abundant evidence that the production of NO is significantly raised within MS lesions, arising not only from the pathological study of lesions themselves, but also from studies of the CSF, blood, and urine patients, and the electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy of animals with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model for MS [4,5]. Several studies demonstrate that nitric oxide plays an important role in oligodendrocytes damage in MS [6,7]. Increased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) has been detected in MS lesions. In fact, both endogenous NO released by glial cells and NO generated from exogenous NO donors are known to induce oligodendrocytes death [3,8–10].

Astrocytes, a major gial cells in the CNS, and microglia play an important role in the regulation of immune responses by functioning as a source of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, chemokines and NO [3,11,12]. Chronically activated astrocytes and microglia are also believed to contribute to the pathology of neuroimmunological diseases including MS [10,13]. Previous studies have shown that astrocytes play important roles in development and differentiation of oligodendrocytes and the proinflammatory products of astrocytes were important in ridding the CNS of pathogens [14]. However, they can also be toxic to host CNS cells including myelin producing oligodendrocytes, which are compromised in the course of primary demyelination in MS and considered to contribute significantly to functional neurological deficits [15]. In acute MS lesions and experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE), intense reactivity for iNOS mRNA and protein was detected in reactive astrocytes and microglia throughout the lesions and in adjacent normal appearing white matter and that astrocyte-derived NO could be important in orchestrating inflammatory response in MS [16–18].

An inflammatory response can be induced experimentally by various agents activating microglial cells and astrocytes. The cytokines IFN-γ secreted by activated lymphocytes and detected in the brain during the symptomatic phase of MS, It can directly activates cells of the macrophage lineage [19–21]. IFN-γ is also able to target oligodendrocytes and can lead to demyelination after a repeated application [22]. The endotoxin LPS from bacterial origin has been shown to activate microglia and to induce the proinflammatory mediators [13]. LPS also induced the death of oligodendrocytes and neurons. Li et al. demonstrated that peroxynitrite, a short-lived potent oxidant and the reaction product of nitric oxide (NO) and superoxide is the toxic microglial factor responsible for LPS induced death of pre-oligodendrocytes [8].

Environmental factor (s), particularly viral infection, has been implicated as one of the potential triggering events leading to demyelination in MS [23–25]. Demyelination in both humans and rodents can be initiated by infection with a diverse group of viruses. Both retroviral expression and cytotoxic factor production have been evidenced in MS monocyte/macrophage cultures and cerebrospinal fluid. Coronavirus RNA was detected in MS patient brains and in cerebrospinal fluid of MS and other neurological diseases. Recently, it has been reported that RNA viral mimic polyIC causes the oligodendrocytes death when mixed glial cultures were treated with polyIC [26]. The toxic effect of polyIC was indirect as it failed to affect pre-oligodendrocytes in pure cultures despite the pre-oligodendrocytes express TLR3 [26]. It has been reported that polyIC induces the expression of NO from human astrocytes [27].

Previous reports have shown that NO damages oligodendrocytes and myelin, resulting in swelling of myelin sheaths and oligodendrocytes death. However the mechanisms of oligodendrocytes damage induced by NO are not well understood. In the present study, we show that both exogenous and endogenous NO down-regulates the expression of myelin genes (MBP, PLP, CNPase, and MOG) in primary human mixed glial cells and oligodendrocytes, which is probably an early event before the oligodendrocytes death.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Fetal bovine serum, Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS), trypsin and DMEM/F-12 were from Mediatech (USA). Recombinanat human IFN-γ, IL-1β were obtained from R & D (USA). Uric acid, 3-Morpholinosydnonimine hydrochloride (SIN1), LPS (Escherichia colt), S-nitroso-N-acetyl-DL-penicillamine (SNAP) and sodium nitoprusside (SNP) were purchased from sigma. L-N6-(1-Iminoethyl)-lysine (L-NIL), was obtained from Biomol. 2-phenyl-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazolineoxyl-1-oxyl-3-oxide (PTIO) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotecnol. NOC-7 was obtained from Calbiochem. Antibodies against MOG, PLP and GFAP were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Isolation of human mixed glial cultures and primary oligodendrocytes

Human fetal brain tissues were obtained from the Human Embryology Laboratory, University of Washington, Seattle. All of the experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Rush University Medical Center. Briefly, 14- to 16-weeks-old fetal brains obtained from the Human Embryology Laboratory (University of Washington, Seattle, WA) were dissociated by trituration and trypsinization (0.25% trypsin in PBS at 37°C for 15 min). The trypsin was inactivated with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Mediatech, Washington, DC). The dissociated cells were filtered successively through 380 and 140 µm meshes (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and pelleted by centrifugation. The resulting suspension was centrifuged for 10 min at 1500 rpm and then resuspended in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 20% heat inactivated FBS. Cells were plated on poly-D-lysine-coated 75 cm2 flasks and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 in air. Culture medium was changed after every 3 days. The initial mixed glial cultures, grown for 9 days, were placed on a rotary shaker at 240 rpm at 37°C for 2 hrs to remove loosely attached microglia. The oligodendrocytes were detached after shaking for 18 hrs at 200 rpm at 11 days. To purify oligodendrocytes from astrocytes and microglia, the detached cell suspension was plated in tissue culture dishes (2×l06 cells/100 mm) for 60 min at 37°C. This step was repeated twice for non-adherent cells to minimize the contamination. The non-adhering cells, mostly oligodendrocytes, were seeded onto poly-D-lysine-coated culture plates in complete medium (DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS) at 37°C with 5% CO2 in air. The remaining cells in the flask are astrocytes. Earlier we [28,29] have shown that oligodendrocytes isolated through this procedure are more than 98% pure.

Immunostaining of MBP, CNPase, MOG, PLP, GFAP, and Ibal

Immunostaining was performed as described earlier [28–30]. Briefly, coverslips containing 200–300 cells/mm2 were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, followed by treatment with cold ethanol (−20°C) for 5 min and two rinses in PBS. Samples were blocked with 3% BSA in PBS containing Tween 20 (PBST) for 30 min and incubated in PBST containing 1% BSA and goat anti-MOG (1:50), rabbit anti-PLP (1:70), and rabbit anti-CNPase (1:50). After three washes in PBST (15 min each), slides were further incubated with Cy5 and Cy2 (Jackson Immuno Research, West Grove, PA). For negative controls, a set of culture slides was incubated under similar conditions without the primary antibodies. The samples were mounted and observed under a Bio-Rad MRC1024ES confocal laser-scanning microscope.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from human oligodendrocytes and mixed glial cells using RNA-Easy Qiagen kit following manufactures protocol. To remove any contaminating genomic DNA, total RNA was digested with DNase. Semiquantitative RT-PCR was carried out as described earlier using oligo(dT) 12–18 as primer and MMLV reverse transcriptase (Clontech) in a 20 µl reaction mixture [28,30]. The resulting cDNA was appropriately diluted, and diluted cDNA was amplified using Titanium Taq polymerase and the following primers.

Human primers

hMBP: sense, 5’-GGA AAC CAC GCA GGC AAA CGA GA-3’; antisense, 5’-GAA AAG AGG CGG ATC AAG TGG GG-3’; hPLP: sense, 5’-CTT CCC TGG TGG CCA CTG GAT TGT-3’; antisense, 5’-TGA TGT TGG CCT CTG GAA CCC CTC-3’; hMOG: sense, 5’-TCC TCC TCC TCC TCC AAG TGT CT-3’; antisense, 5’-AGT GGG GAT CAA AAG TCC GGT GG-3’; hCNPase: sense, 5’-GGC CAC GCT GCT AGA GTG CAA GAC-3’; antisense, 5’-GGT ACT GGT ACT GGT CGG CCA TTT-3’; hGAPDH: Sense, 5’-GGT GAA GGT CGG AGT CAA CG-3’; antisense, 5’-GTG AAG ACG CCA GTG GAC TC-3’.

Amplified products were electrophoresed on a 1.8% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Message for the GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) gene was used to ascertain that an equivalent amount of cDNA was synthesized from different samples.

Real-time PCR analysis

It was performed using the ABI-Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as described earlier [28,30,31]. All primers and FAM-labeled probes for human MBP, PLP, MOG, CNPase, and GAPDH were obtained from Applied Biosytems. The mRNA expression of myelin genes was normalized to the label of GAPDH mRNA. Data were processed by the ABI Sequence Detection System 1.6 software and analyzed by ANOVA.

Assay for NO Synthesis

Synthesis of NO was determined by assay of culture supernatants for nitrite, a stable reaction product of NO with molecular oxygen, using Griess reagent as described [32,33].

Immunoblotting

Western blotting was conducted as described earlier [30,34]. Briefly, cells were scraped in lysis buffer, transferred to microfuse tube and spun into pellets. The supernatant was collected, and was analyzed for protein concentration via the Bradford methods (Bio-Rad). SDS sample buffer was added to 40–50 µg total protein and boiled for 5 mins. Denatured samples were electrophoresed on NeuPAGE Novex 4–12% Bis Tris gel (Invitrogen) and protein transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) using the Thermo-Pierce Fast Semi-Dry Blotter. The membrane was then washed for 15 min in PBS plus Tween 20 (PBST) and blocked for 1 h in PBST containing 2% BSA. Next, membranes were incubated overnight at 40°C under shaking conditions with primary antibodies. The next day membranes were washed in PBST for 1 h, incubated in secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature, washed for one more hour and visualized under the Odyssey Infrared Imaging system (Li-Cor, Lincoln, Nebraska).

Astrocyte-oligodendrocytes transwell study

Primary human astrocytes were grown to confluency on inserts. In this culture more than 98% of the cells were identified as astrocytes [29,30]. First time we have reported that IL-1b treatment of human primary astrocytes alone induces the high level of NO production [32]. After 6 h of stimulation by the IL-1β (10 ng/ml) under serum free conditions, inserts were washed thrice with HBSS and then placed onto the wells containing primary human oligodendrocytes that were already pretreated with uric acid and Carboxy-PTIO. Non treated cells were served as controls in all experiments. Therefore, in this transwell model, although oligodendrocytes and astrocytes face each other, they are separable, and the effect of soluble factors released from activated astrocytes on oligodendrocytes can be studied, allowing analysis of oligodendrocytes and astrocytes populations separately.

Results

(LPS+IFN-γ) and polyIC induce the production of NO in human fetal mixed glial cultures

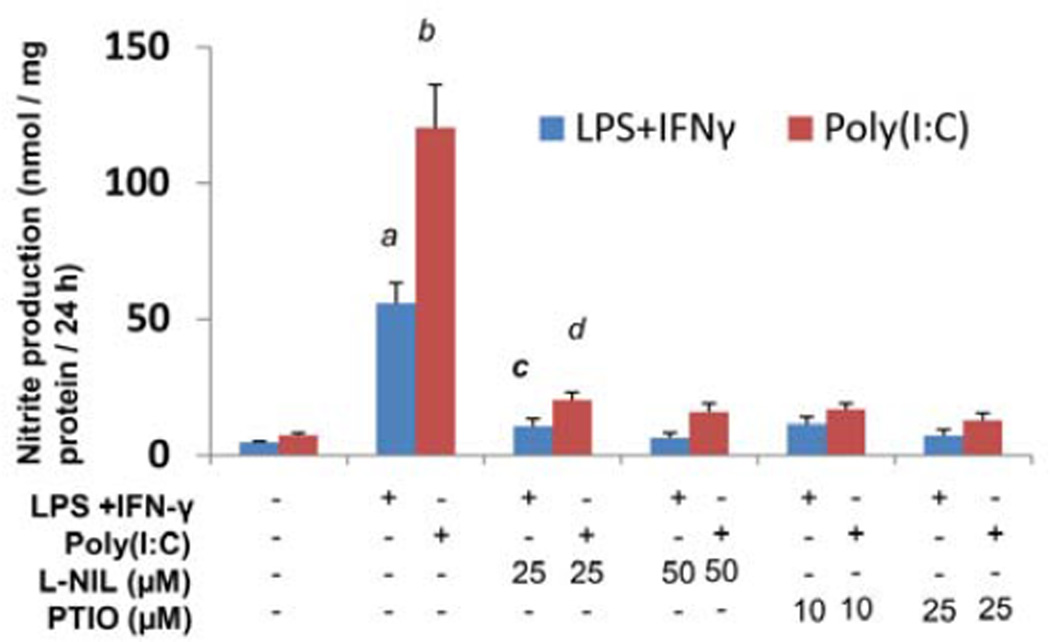

LPS is a potent inducer of inflammation [35]. IFN-γ is a pleiotrophic cytokine that plays an important role in many inflammatory processes, including autoimmune diseases such as MS [36]. Several reports indicate that LPS alone and (LPS+IFN-γ) combination are a potent inducer of NO production in astrocytes and microglia [8,11]. Specifically, the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is up-regulated during inflammation and infection, and up-regulation can be sustained over a prolonged period culminating in the production of large quantities of NO [11,35,37]. Production of NO generally starts at 12 h and maximum production is observed at 24 h time period. Several reports also demonstrate that NO causes the damage of oligodendrocytes [8,10]. Mixed glial cultures were treated with (LPS+IFN-γ) under serum free conditions for 24 h. It is evident from Figure 1 that (LPS+IFN-γ) markedly induced the production of NO in mixed glial cultures. One hour pretreatment of L-NIL (an inhibitor of NOS) and PTIO (a scavenger of NO) inhibited the (LPS+IFN-γ)-mediated NO production (Figure 1).

Figure 1. (LPS+IFN-γ) and polyIC induce the production of NO in human primary fetal mixed glial cultures.

Mixed glial cells prelncubated with different concentrations of L-NIL and PTIO for 1 h under serum free conditions were stimulated either with 1 µg/ml of LPS and 6.25 mU/ml of IFN-γ or 100 µg/ml polyIC for 24 h and the nitrite concentrations were measured (B). Data are means ± S.D. of three different experiments.ap<0.01 vs. control, bp<0.001 vs. control, cp<0.01 vs. nitrite in (LPS+IFN-γ) treatment, dp<0.001 vs. nitrite in polyIC treatment.

PolyIC, a synthetic dsRNA copolymer of inosinic and cytidic acids has been often used as tool to mimic the effects of dsRNA intermediates produced during viral infection of cells. Mixed glial cultures were treated with polyIC under serum free conditions for 24 h. PolyIC also induced the production of NO in human mixed glial cells and this induction of NO production was inhibited by L-NIL (an inhibitor of NOS) and PTIO (a scavenger of NO) (Figure 1). All these results clearly demonstrate that (LPS+IFN-γ), and polyIC induce the NO production in human fetal mixed glial cultures.

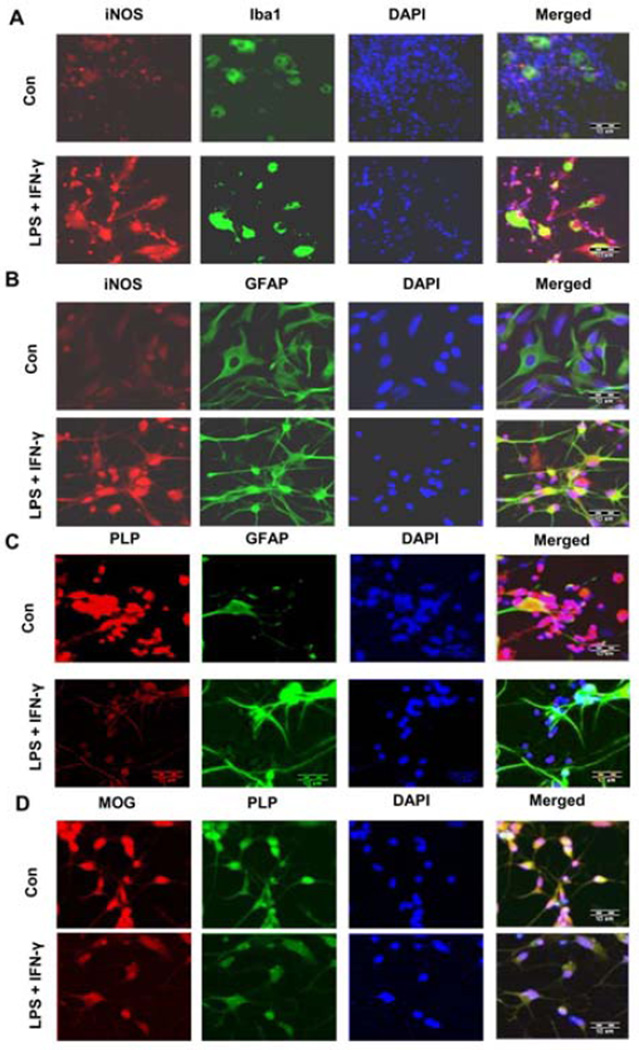

(LPS+IFN-γ) induced the production of iNOS from activated glia and suppressed the expression of myelin genes in human fetal mixed glial cultures

Next, to investigate whether (LPS+IFN-γ)-mediated nitric oxide is capable of down-regulating the myelin gene expression in mixed glial cultures Mixed glial cultures were treated with (LPS+IFN-γ) under serum free conditions for 24 h. Apart from oligodendrocytes, mixed glial cells contained other glial cells like astroglia and microglia. While GFAP is a marker of astrocytes, microglia is identified by Ibal. Immunofluroscence analysis showed that (LPS+IFN-γ) activated the expression of microglial marker Ibal and astroglial marker GFAP (Figures 2A, 2B and 2C). It was also found that (LPS+IFN-γ) markedly induced the production of iNOS expression in astrocytes and microglia (Figures 2A and 2B), while down-regulating the expression of myelin proteins PLP and MOG in fetal mixed glial cultures (Figures 2C and 2D).

Figure 2. The combination of (LPS+IFN-γ) upregulates the iNOS protein expression in astrocytes and microglia, and down-regulates the expression of MOG and PLP in oligodendrocytes.

Human mixed glial cells were treated with the combination of LPS (1 µg/ml) and IFN-γ (6.25 mU/ml) under serum free conditions. After 24 h, cells were immunostained with INOS & lba1 (A), iNOS & GFAP (B), PLP & GFAP (C), and MOG & PLP (D). Scale bars represent 10 µM.

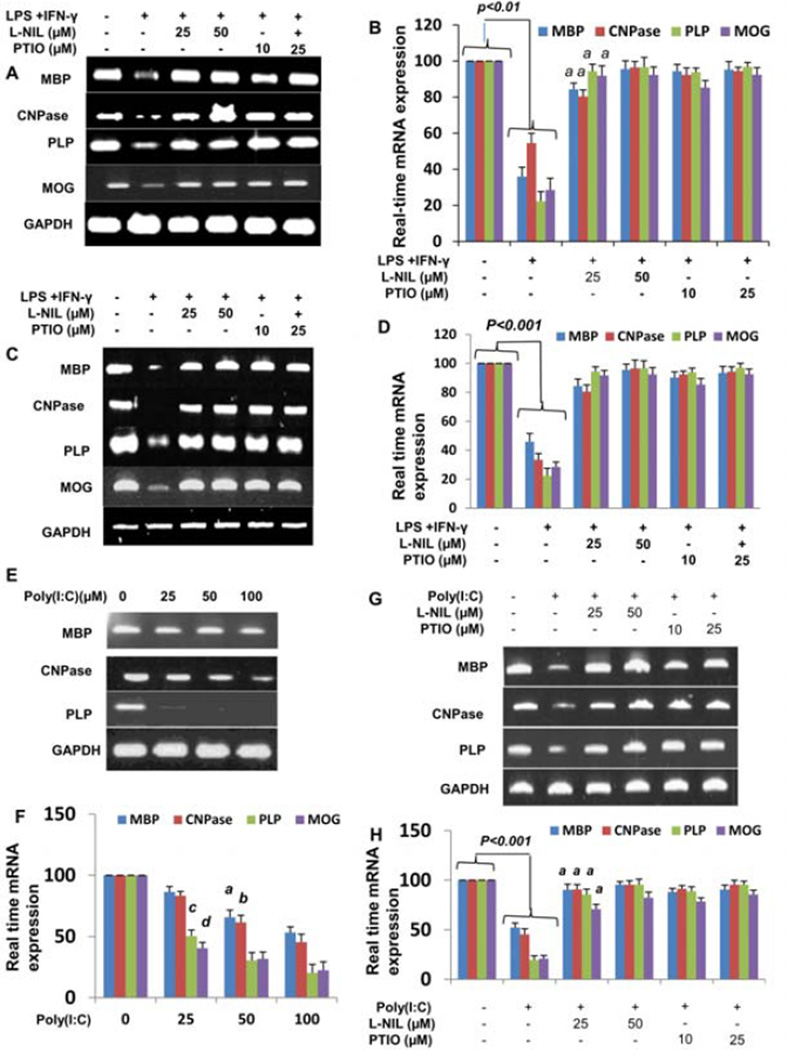

PTIO and L-NIL block (LPS+IFN-γ)- and poyIC mediated down-regulation of myelin gene expression in human primary mixed glial cultures and spinal cord mixed glial cultures

To investigate whether (LPS+IFN-γ) down-regulates the myelin gene expression in human mixed glial culture, cells were treated with (LPS+IFN-γ) combination for 24 h. The expression of MBP, PLP, MOG, and CNPase was analyzed by semi-quantitative PCR and real time PCR. Results showed that (LPS+IFN-γ) combination suppressed the myelin gene expression (Figures 3A and 3B). However, the expression of GAPDH remained unaltered under the same treatment conditions. These results suggest that decreased expression of MBP, MOG, PLP, and CNPase in (LPS+IFN-γ)-challenged oligodendrocytes is not due to cell death.

Figure 3. Effect of L-NIL and PTIO on (IFN-γ + LPS)- and polyIC-mediated decrease in myelin gene expression in human fetal mixed glial cultures.

Human primary brain (A & B) and spinal cord (C & D) mixed glial cells preincubated with different concentrations of L-NIL and PTIO for 1 h were stimulated with 1 µg/ml of LPS and 6.25 mU/ml of IFN-γ. After 24 h of stimulation, the expression of MBP, MOG, PLP, and CNPase mRNA was analyzed in cells by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (A & C). Quantitative real time PCR was also employed to further clarify the expression of myelin genes (B & D). ap<0.001. Human primary mixed glial cell were stimulated with different concentrations of polyIC under serum free conditions. After 24 h of stimulation, the expression of myelin genes was analyzed in cells by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (E) and real time-PCR (F). ap<0.01, bp<0.01, cp<0.001 & dp<0.001 vs. polyIC-treated cells. Cells preincubated with different concentrations of L-NIL and PTIO for 1 h were stimulated with 100 µg/ml of polyIC. After 24 h of stimulation, the expression of MBP, MOG, PLP, and CNPase mRNA was analyzed in cells by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (G) and Quantitative real time PCR (H). Results are mean ± S.D. of three different experiments. ap<0.001 vs. polyIC-treated cells.

Next, to test the role of NO in (LPS+IFN-γ)-mediated down-regulation of myelin gene expression, we examined the effect of L-NIL (an inhibitor of NOS) and carboxyl PTIO (a scavenger of NO) on the (LPS+IFN-γ)-mediated decrease in myelin gene expression in mixed glial cultures. Mixed glial cultures preincubated with different concentration of L-NIL and PTIO for 1 h were treated with (LPS+IFN-γ) for 24 h followed by semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis for myelin genes. As observed in Figure 3A, both L-NIL and PTIO prevented (LPS+IFN-γ)-mediated suppression of MBP, CNPase, MOG, and PLP expression. This finding is also supported by real time PCR (Figure 3B). These results suggest that (LPS+IFN-γ) inhibit the expression of myelin gene in human primary mixed culture via NO.

Next we tested whether L-NIL and PTIO were capable of inhibiting the (LPS+IFN-γ)-mediated down-regulation of myelin gene expression in human fetal spinal cord mixed cultures. As evident from semi-quantitave RT-PCR in Figure 3C and real time PCR in Figure 3D, L-NIL and PTIO significantly inhibited the (LPS+IFN-γ)-mediated down-regulation of myelin gene expression.

To investigate the effect of polyIC on the expression of myelin specific genes in human primary mixed glial cultures, cells were treated with different concentration of polyIC for 24 h. The expression of MBP, PLP, MOG, and CNPase was analyzed by semi-quantitative PCR and real time PCR. It is clearly evident from Figures 3E and 3F that polyIC dose dependently inhibited the expression MBP, PLP, MOG, and CNPase. Marked decreased in the expression of PLP was observed at 25 µM of polyIC. On the other hand, the expression of MBP was affected moderately by treatment with polyIC.

To investigate the role of NO in polyIC-mediated down-regulation of myelin gene expression, we examined the effect of L-NIL and carboxyl PTIO on the polyIC-mediated decreased in myelin gene expression in mixed glial culteures. Mixed glial cultures preincubated with different concentration of L-NIL and PTIO for 1 h were treated with polyIC for 24 h followed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis (Figure 3G) and real time PCR (Figure 3H) for myelin genes. As observed in Figures 3G and 3H, both L-NIL and PTIO prevented polyIC-mediated down-regulation of CNPase, PLP, MOG, and MBP expression. All these results suggest that polyIC-induced NO are an important factor to suppress the myelin gene expression.

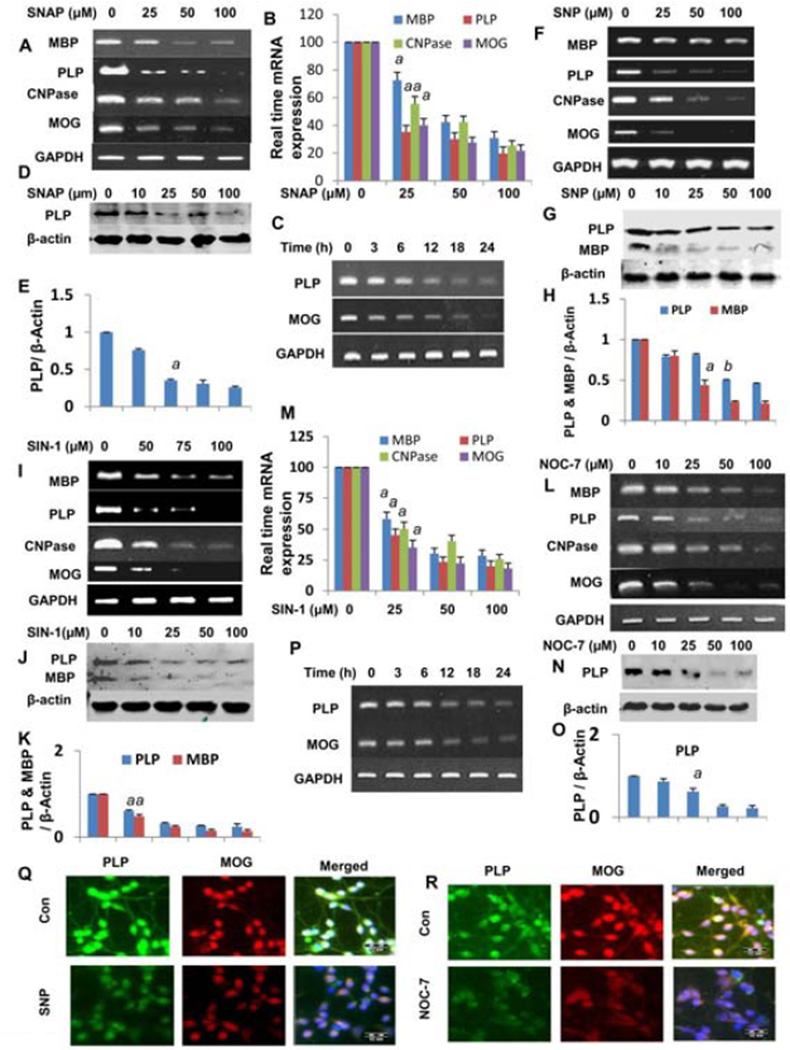

Effect of different NO donor on the expression of myelin gene expression on human primary oligodendrocytes

In our previous results, we have already shown that endogeneous NO- produced from astrocytes and microglia down-regulates the myelin gene expression (Figures 2 and 3). Several reports demonstrate that exogenous NO donors are responsible to the oligodendrocytes death [3,9,10]. To further examine whether exogenous NO produced from different NO donors directly inhibits the expression of myelin gene preceding the oligodendrocytes death, primary human oligodendrocytes were treated with different concentration of SNP, SIN-1, SNAP, and NOC-7. As reported earlier [28–30], oligodendrocytes isolated from human fetal brains were highly pure. These cells were positive for GalC, MBP, PLP, CNPase, and MOG [29,30]. However we were unable to detect any GFAP-positive astroglia and CD11b-positive microglia in this oligodendroglial preparation. Rarely did we observe one GFAP positive astrocyte of 50 or more GalC positive oligodendrocytes [29,30].

Cells were treated with different doses of SNAP under serum free conditions for 12 h and the expression of myelin genes were analyzed by semi-quantitative PCR (Figure 4A) and real time PCR (Figure 4B). Figures 4A and 4B showed that SNAP suppressed the myelin gene expression in a dose dependent manner. Figure 4C showed that SNAP time dependency inhibited the expression of myelin genes MBP, PLP, MOG and CNPase. Maximum inhibition was observed at 12 h. Next we determined the effect of SNAP on the expression of myelin protein PLP in primary oligodendrocytes. As evident from the Western blots in Figure 4D, SNAP, dose dependently inhibited the expression PLP in human oligodendrocytes. Dentiometric analysis also further confirmed these results (Figure 4E). Similarly, other nitric oxide donors including SNP (Figures 4F, 4G and 4H) SIN-1 (Figures 4I, 4J and 4K) and NOC7 (Figures 4L, 4M, 4N, 4O and 4P) had been shown to suppress the expression of myelin molecule by mRNA and protein analyses. Similarly, immunofluroscence analysis also shows that SNP and NOC-7 markedly inhibited the protein expression of MOG and PLP (Figures 4Q and 4R). Taken together, these results clearly suggest that exogenous NO donors are capable of suppressing the expression of myelin genes in human primary oligodendrocytes.

Figure 4. Effect of SNP, SIN-1, SNAP, and NOC-7 on myelin gene expression in human primary oligodendrocytes.

Cells were treated with different doses of SNAP, SNP, SIN-1 and NOC-7 for 12 h. After 12 h of stimulation, the expression of MBP, MOG, PLP, and CNPase mRNA was analyzed In cells by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (A, F, I and L) and real time–PCR for SNAP (B) and NOC-7 (M) respectively. ap<0.001 vs control. Cells were treated with 50 µM of SNAP and NOC-7 for different period of time. The expression of MOG & PLP mRNA was analyzed in cells by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (C and P). Cells were treated with different concentrations of SNAP, SNP, SIN-1 and NOC-7. After 18 h of treatment, the protein levels of PLP and MBP was examined by Western blot (D, G, J & N) and further confirmed by dentiometric analysis (E, H, K & O). ap<0.01, bp<0.01 vs control PLP. Cells were treated with 50 µM of SNP and NOC-7. After 18 h, Cells were immunostained with PLP and MOG (Q & R). Figures are representative of three independent experiments.

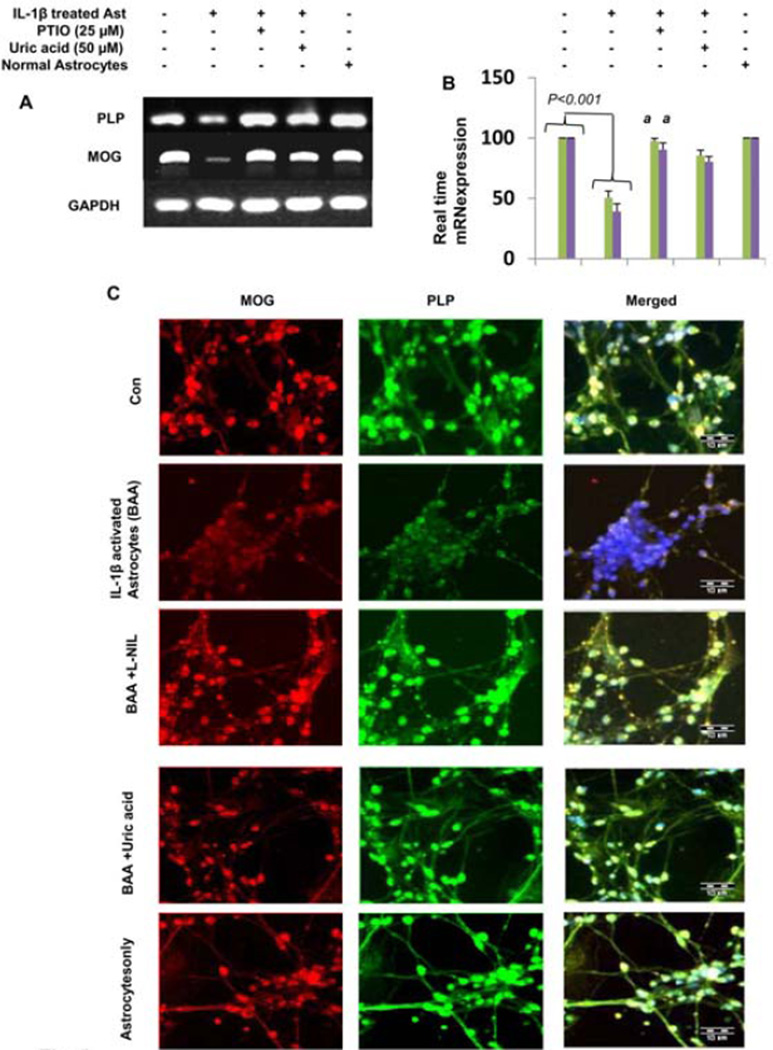

Nitric oxide regulated myelin gene expression in oligodendrocytes mediated by conditioned medias from astrocytes

NO and TNF-α can selectively damage oligodendrocytes, resulting in severe demyelination. Previously we also demonstrate that TNF-α downregulates the myelin gene expression [28]. We have found that exogenous NO decreased the myelin gene expression (Figure 4). To identify the mechanism underlying the down-regulation of myelin gene expression in oligodendroctes by activated astrocytes, we next asked whether cell-to-cell contact was required for the down-regulation of myelin gene expression. To pursue this question, we performed experiments by using porous transwells in which astrocytes were cultured in transwell and placed into 12-well culture plates containing pure oligodendrocytes. So there was no physical contact between the two cell types but soluble/secreted factors could move across the transwell. In the presence of transwell containing IL-1β activated astrocytes, the expression of PLP and MOG was inhibited. But in the presence of transwell containing untreated astrocytes, PLP and MOG expression remained unchanged. These observations suggested that diffusible factors were responsible for the down-regulation of myelin gene expression. It is evident from Figure 5A that L-NIL and uric acid block the soluble factor-mediated down-regulation of myelin gene expression. Quantitative real time PCR data in Figure 5B supported this conclusion. Consistent with mRNA results, L-NIL and uric acid also inhibited the soluble factor mediated suppression of PLP and MOG (Figure 5C). These results further suggest that IL-1β activated astrocytes induce NO that reacts with superoxide anion at a diffusion-limited rate to form the short-lived potent oxidant peroxynitrite.

Figure 5. L-NIL and uric acid block down-regulation of myelin gene expression from IL-1β activated human primary astrocytes in astrocytes-oligodendrocytes transwell cultures.

Human primary oligodendrocytes were treated with PTIO and Uric acid. Primary human astrocytes seeded in inserts were stimulated with 10 ng/ml IL-1β under serum free conditions for 6 h. After 6 h of treatments, IL-1β medium was replaced by fresh medium and placed in oligodendrocytes culture well for 24 h that were already pretreated with uric acid and Carboxy-PTIO. After 24 h, oligodendrocytes cells were collected for PLP expression. The expression of PLP and MOG mRNA was analyzed in cells by semi-quantitative RT-PCR and real time PCR (A & B). Results are means ± S.D. of three different experiments. p<0.001. Oligodendrocytes were immunostained with PLP and MOG (C). Figures are representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

It has been shown that myelin-specific genes decrease in the CNS of MS patients and EAE animals, and an increase in myelin-specific genes is a prerequisite to an increase in CNS remyelination. However, despite extensive research on the pathogenesis of MS, no effective therapy is available to halt demyelination and/or stimulate remyelination. Many studies have documented the fact that cytokine induced NO production can lead to damage and destruction of normal cells [4]. It is implicated in autoimmune diseases such as diabetes were the death of pancreatic β islet cells occurs as well as normal tissue damage as the result of infarction, such as damage to neurons during stroke. Several reports demonstrate the role for NO in glial cells killing of the myelin-producing cell, the oligodendrocytes [4,8,18,26]. Previous work showed that in mature aggregating brain cells cultures, the combined treatment with IFN-γ and LPS, two inflammatory agents, caused microglial activation and the up-regulation of a variety of inflammatory mediators including cytokines, chemokines and NO. This inflammatory response was accompanied by demyelination in the absence of neuronal damage, cell death or astrogliosis [38]. The excessive release of NO is major mediator in autoimmune diseases and is involved in the killing of oligodendrocytes, resulting in subsequent demyelination and permanent neurological deficits in affected individuals [12,39].

Several lines of evidence presented in this manuscript clearly demonstrate that NO plays a key role in the down-regulation of myelin genes preceding the oligodendrocytes death. First, (LPS+IFN-γ) combination or PolyIC were unable to inhibit the myelin gene expression in mixed glial cultures where either NO production was inhibited by L-NIL or NO was scavenged by PTIO. Second, NO alone was also capable of inhibiting the expression of myelin gene expression in primary human oligodendrocytes. Third, to address the possibility of correlation between NO and down-regulation of myelin gene expression, we applied conditional media from astrocytes by treatment with IL-1β to culture primary oligodendrocytes. The conditioned media from astrocytes treated by IL-βcauses the down-regulation of myelin gene expression. Pretreatment astrocytes with uric acid and PTIO restore the myelin gene expression. These observations demonstrate that myelin gene expression is regulated by NO produced by activated astrocytes. This study also demonstrates that cell-to-cell contact is not necessary to down-regulation of myelin gene expression.

Only microglia and astrocytes, but not oligodendrocytes expressed inducible nitric oxide synthase after (LPS+IFN-γ) challenge [8]. Studies published in other reports have shown that microglia and astrocytes produce significant NO2- or NOS production after stimulation either with (LPS+IFN-γ) or polyIC [3,8]. NO is a reactive molecule, it does not exist in tissues only as a free radical; it also gives rise, sometimes reversibly, to several other related compounds. These compounds include the nitroxyl (NO=) ion, nitrous acid (HNO2), the nitrogen dioxide (NO2) radical, peroxynitrite (ONOO-; a product of the combination of superoxide and nitric oxide) and peroxinitrous acid (ONOOH) [4]. Forms that NO takes at the site of inflammation are not known with much certainty. In pathological conditions, NO reacts with superoxide to form peroxynitrite, which nitrates proteins forming nitrotyrosine residues, leading to loss of protein function, perturbation of signal transduction, and cell death [40]. In the present study, we have examined four different NO generators to regulate the role of myelin genes expression in human primary oligodendrocytes. Previous studies demonstrate that all these NO donors cause the oligodendrocytes damage [9]. SNAP generates the NO radical NO., SNP generates nitrosonium ion, NO+, and SIN-1 generates peroxynitrite [9,41]. These molecules cause oligodendrocytes damage by different mechanisms, but we found that all these molecules downregulates the myelin gene expression. Scavenging of peroxynitrite by uric acid blocks conditioned media mediated-down-regulation of myelin gene expression suggesting that peroxitrite is the major reactive species in IL-1β-activated astrocytes, and it is an important regulator of myelin gene expression.

In summary, we have demonstrated that NO suppresses the expression of MBP, MOG, CNPase, and PLP preceding the oligodendrocytes death. Although the in vitro situation of human fetal oligodendrocytes in culture does not truly resemble the complex in vivo situation of oligodendrocytes in the CNS of MS patients, therefore, our results suggest that specific targeting of NO either by iNOS inhibitors or NO scavengers may be an important step for the preservation of myelin gene expression in the inflammatory CNS of MS patients.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant (R01AT6681) and Veteran Affairs Merit Award (I01BX002174) to KP.

Abbreviations

- NO

Nitric Oxide

- SIN-1

3-Morpholinosydnonimine Hydrochloride

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharides

- SNAP

S-nitroso-N-acetyl-DL-penicillamine

- SNP

Sodium Nitroprusside

- L-NIL

L-N6-(1-Iminoethyl)-lysine

- PTIO

2-phenyl-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazolineoxyl-1-oxyl-3-oxide

- MBP

Myelin Basic Protein

- MOG

Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein

- PLP

Proteolipid Protein

- CNPase

2’,3’-cyclic nucleotide 3’-phosphodiesterase

- GFAP

Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein

- PolyIC

Polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Kurth E. A modified method for clearing leaves. Stain Technol. 1978;53:291–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu H, MaoKenzie-Graham AJ, Kim S, Voskuhl RR. Mice resistant to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis have increased thymic expression of myelin basic protein and increased MBP specific T cell tolerance. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;115:118–126. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merrill JE, Ignarro LJ, Sherman MP, Melinek J, Lane TE. Microglial cell cytotoxicity of oligodendrocytes is mediated through nitric oxide. J Immunol. 1993;151:2132–2141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith KJ, Lassmann H. The role of nitric oxide in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:232–241. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagasra O, Michaels FH, Zheng YM, Bobraski LE, Spitsin SV, et al. Activation of the inducible form of nitric oxide synthase in the brains of patients with multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:12041–12045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witherick J, Wilkins A, Scolding N, Kemp K. Mechanisms of oxidative damage in multiple sclerosis and a cell therapy approach to treatment. Autoimmune Dis. 2010;2011:164608. doi: 10.4061/2011/164608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calabrese V, Scapagnini G, Ravagna A, Bella R, Foresti R, et al. Nitric oxide synthase is present in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with active multiple sclerosis and is associated with increases in cerebrospinal fluid protein nitrotyrosine and S-nitrosothiols and with changes in glutathione levels. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:580–587. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, Baud O, Vartanian T, Volpe JJ, Rosenberg PA. Peroxynitrite generated by inducible nitric oxide synthase and NADPH oxidase mediates microglial toxicity to oligodendrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9936–9941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502552102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boullerne Al, Nedelkoska L, Benjamins JA. Synergism of nitric oxide and iron in killing the transformed murine oligodendrocyte cell line N20.1. J Neurochem. 1999;72:1050–1060. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0721050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boullerne Al, Benjamins JA. Nitric oxide synthase expression and nitric oxide toxicity in oligodendrocytes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:967–980. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Yan M, Hu L, Sun L, Zhang F, et al. Involvement of Src-suppressed C kinase substrate in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: a link between release of astrocyte proinflammatory factor and oligodendrocyte apoptosis. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:1858–1871. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu J, Drew PD. 9-Cis-retinoic acid suppresses inflammatory responses of microglia and astrocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;171:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pang Y, Campbell L, Zheng B, Fan L, Cai Z, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-activated microglia induce death of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells and impede their development. Neuroscience. 2009;166:464–475. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pang Y, Cai Z, Rhodes PG. Analysis of genes differentially expressed in astrocytes stimulated with lipopolysaccharide using cDNA arrays. Brain Res. 2001;914:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02766-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin R, McFariand MF, McFarlin DE. Immunological aspects of demyelinating diseases. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:153–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.001101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu JS, Zhao ML, Brosnan CF, Lee SC. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitrotyrosine in multiple sclerosis lesions. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:2057–2066. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64677-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tran EH, Hardin-Pouzet H, Verge G, Owens T. Astrocytes and microglia express inducible nitric oxide synthase in mice with experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;74:121–129. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(96)00215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molina-Holgado E, Vela JM, Arévalo-Martín A, Guaza C. LPS/IFN-gamma cytotoxicity in oligodendroglial cells: role of nitric oxide and protection by the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:493–502. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2000.01412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martino G, clementi E, Brambilla E, Moiola L, Comi G, et al. Gamma interferon activates a previously undescribed Ca2+ influx in T lymphocytes from patients with multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4825–4829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panitch HS, Hirsch RL, Schindler J, Johnson KP. Treatment of multiple sclerosis with gamma interferon: exacerbations associated with activation of the immune system. Neurology. 1987;37:1097–1102. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.7.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baerwald KD, Popko B. Developing and mature oligodendracytes respond differently to the immune cytokine interferon-gamma. J Neurosci Res. 1998;52:230–239. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980415)52:2<230::AID-JNR11>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Defaux A, Zurich MG, Honegger P, Monnet-Tschudi F. Inflammatory responses in aggregating rat brain cell cultures subjected to different demyelinating conditions. Brain Res. 2010;1353:213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ebers GC, Sadovnick AD. The role of genetic factors in multiple sclerosis susceptibility. J Neuroimmunol. 1994;54:1–17. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)90225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theil DJ, Tsunoda I, Rodriguez F, Whitton JL, Fujinami RS. Viruses can silently prime for and trigger central nervous system autoimmune disease. J Neurovirol. 2001;7:220–227. doi: 10.1080/13550280152403263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oleszak EL, Katsetos CD, Kuzmak J, Varadhachary A. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus infection. J Virol. 1997;71:3228–3235. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3228-3235.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steelman AJ, Li J. Poly(I:C) promotes TNFalpha/NFR1 -dependent oligodendrocyte death in mixed glial cultures. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:89. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Auch CJ, Saha RN, Sheikh FG, Liu X, Jacobs BL, et al. Role of protein kinase R in double-stranded RNA-induced expression of nitric oxide synthase in human astroglia. FEBS Lett. 2004;563:223–228. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00302-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jana M, Pahan K. Redox regulation of cytokine-mediated inhibition of myelin gene expression in human primary oligodendrocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:823–831. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jana M, Jana A, Pal U, Pahan K. A simplified method for isolating highly purified neurons, oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and microglia from the same human fetal brain tissue. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:2015–2022. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9340-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jana M, Mondal S, Gonzalez FJ, Pahan K. Gemfibrozil, a lipid-lowering drug, increases myelin genes in human oligodendrocytes via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-beta. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:34134–34148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.398552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dasgupta S, Jana M, Zhou Y, Fung YK, Ghosh S, et al. Antineuroinflammatory effect of NF-kappaB essential modifier-binding domain peptides in the adoptive transfer model of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2004;173:1344–1454. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jana M, Anderson JA, Saha RN, Liu X, Pahan K. Regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase in proinflammatory cytokine-stimulated human primary astrocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:655–664. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jana M, Dasgupta S, Pal U, Pahan K. IL 12 p40 homodimer, the so-called biologically inactive molecule, induces nitric oxide synthase in microglia via IL-12R beta 1. Glia. 2009;57:1553–1565. doi: 10.1002/glia.20869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jana M, Pahan K. IL-12 p40 homodimer, but not IL-12 p70, induces the expression of IL-16 in microglia and macrophages. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:773–783. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cines DB, Pollak ES, Buck CA, Loscalzo J, Zimmerman GA, et al. Endotheiiai cells in physiology and in the pathophysioiogy of vascular disorders. Blood. 1998;91:3527–3561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maña P, Liñares D, Fordham S, Staykova M, Willenborg D. Deleterious role of IFNgamma in a toxic model of central nervous system demyeiination. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1464–1473. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staykova MA, Paridaen JT, Cowden WB, Willenborg DO. Nitric oxide contributes to resistance of the Brown Norway rat to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:147–157. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62240-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Defaux A, Zurich MG, Honegger P, Monnet-Tschudi F. Minocycline promotes remyelination in aggregating rat brain cell cultures after interferon-gamma plus lipopolysaccharide-induced demyeiination. Neuroscience. 2011;187:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paintlia AS, Paintlia MK, Singh I, Singh AK. IL-4-induced peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activation inhibits NF-kappaB trans activation in central nervous system (CNS) glial cells and protects oligodendrocyte progenitors under neuroinflammatory disease conditions: implication for CNS-demyelinating diseases. J Immunol. 2006;176:4385–4598. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hooper DC, Scott GS, Zborek A, Mikheeva T, Kean RB, et al. Uric acid, a peroxynitrite scavenger, inhibits CNS inflammation, blood-CNS barrier permeability changes, and tissue damage in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. FASEB J. 2000;14:691–698. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.5.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spitsin SV, Scott GS, Mikheeva T, Zborek A, Kean RB, et al. Comparison of uric acid and ascorbic acid in protection against EAE. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1363–1371. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]