Abstract

Because reliance on patients' self-perceived risk for HIV might mislead emergency department (ED) clinicians on the need for HIV testing, we aimed to measure congruency between self-perceived and reported HIV risk in a traditional lower prevalence, lower-risk cohort. A random sample of 18- to 64-year-old patients at a large academic urban ED who were by self-report not men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM) or injection-drug users (IDUs) were surveyed regarding their self-perceived and reported HIV risk. Sixty-two percent of participants were white non-Hispanic, 13.8% Black, and 21.2% Hispanic; and 66.9% previously had been tested for HIV. Linear regression models were constructed comparing self-perceived to reported HIV risk. Among the 329 female ED patients, 50.5% perceived that they were “not at risk” for HIV, yet only 10.9% reported no HIV risk behaviors, while among the 175 male ED patients, 50.9% perceived that they were “not at risk” for HIV, yet only 12.6% reported no HIV risk behaviors. Only 16.9% of women and 15.7% of men who had no self-perceived risk for HIV also reported no HIV risk behaviors. Multivariable linear regression demonstrated a weak relationship between self-perceived and reported risk. Congruency between self-perceived risk and reported HIV risk was low among these non-MSM, non-IDU ED patients.

Introduction

The health belief model1 and protection motivation theory2 posit that once patients are empowered with health information, they are likely to comply with preventive or curative behaviors.3 The foundations of both theories emphasize the importance of self-perceived risk, which is a person's perception of the likelihood that he/she will contract a disease. Self-perceived HIV risk is considered an integral component in motivating avoidance of HIV risk.3 Congruency between self-perception of HIV risk and reported risk-taking behaviors might be especially important in the proclivity to engage in self-protective behaviors, such as condom use and uptake of HIV testing.4–6 People who refuse HIV testing commonly do so because they do not perceive themselves to be at risk;4,7–13 thus, self-perceived risk is an important factor in the uptake of HIV testing. Incongruency between self-perceived and actual risk could result in missed opportunities to identify HIV infection because patients might refuse HIV testing out of a false belief that they are at low risk for an infection.

Recognizing that self-perceived risk might not be accurate, and in an effort to decrease the prevalence of unrecognized HIV infections, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) currently recommends an opt-out approach to screening without routine assessment of risk in healthcare settings.14 CDC specifically advocates for large-scale or en masse opt-out HIV screening among 13- to 64-year-olds without regard to risk factors in the emergency department (ED) setting.15 However, large-scale HIV screening has yet to be universally adopted across US EDs.16–20 Instead, it is likely that clinicians in most EDs are more apt to select for and conduct targeted HIV screening and diagnostic testing among patients they believe to be at higher risk, such as men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM), injection-drug users (IDUs), and patients with a possible sexually transmitted disease (STD). For traditionally lower HIV prevalence and lower-risk populations (e.g., heterosexuals who do not inject drugs) who do not disclose higher-risk behaviors, ED clinicians may be less likely to advocate strongly for or conduct an HIV test, especially among patients who self-perceive themselves to be at lower risk, and consequently inform the ED clinician that they are at low risk for an HIV infection and decline testing. Given the recent de-emphasis on assessing HIV risk, ED clinicians might not attempt to elucidate whether a patient's self-perception of their HIV risk is accurate. This practice is problematic, given the results of a recent study by Ubhayakar et al.,21 which observed that ED patients who declined HIV testing due to no or low self-perceived risk had in fact engaged in risky behaviors, such as having multiple sexual partners within the last year or having sex with partners at higher risk for HIV.

Multiple studies12,22–44 have documented inconsistencies between self-perceived HIV risk and reported HIV risk-taking behaviors, while others have reported varying levels of congruency, which has led to no clear consensus as to how well people can assess their own HIV risk (Table 1). Variations in methods used across studies, and limitations in how self-perceived HIV risk and reported HIV risk was assessed likely impacted these study findings and their authors' interpretations of whether congruency exists between self-perceived HIV risk and reported risk behaviors. These variations and limitations have produced an inconsistent message regarding the relationship between self-perceived and reported risk for HIV. The accuracy of self-perceived risk for HIV becomes clinically relevant when a healthcare provider mistakenly accepts a patient's self-perceived risk as a reason to not pursue testing or not perform a detailed HIV risk assessment. Such practice might miss identifying HIV infections even when an opt-out approach method is used or large scale screening is conducted. Therefore, even when using an opt-out approach, it is important for health care providers to understand the possibility of incongruency between self-perceived and actual risk and how this influences patients to decline HIV testing, even if it would be in their best interest to be tested.

Table 1.

Summary of Articles About Congruency Between Self-Perceived and Reported HIV/AIDS Risk

| |

|

|

Self-perceived assessment |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year | Population | Question and responses | Administration | Reported sexual behaviors | Reported drug behaviors | Congruence conclusions |

| Weisman | 1989 | 430 adolescent women from Planned Parenthood Clinic in Baltimore | How much chance do you think there is that you will get AIDS in the next 5 years? | Face-to-face interview | Yesa | Yes (1 year) | Risk taking behavior not strongly associated with perceived personal risk of AIDS |

| Very sure it will not happen; somewhat sure it will not happen; there is an even chance (50–50); somewhat sure it will happen; very sure it will happen | |||||||

| Prohaska | 1990 | 1540 urban and suburban adults in Chicago | In terms of your own risk of getting AIDS do you think you are at … for getting AIDS? | Telephone interview | Yes (5 years) | None | Two sexual risk practices were congruent with perceived risk of AIDS |

| Great; some; or no risk | |||||||

| Kalichman | 1992 | 384 mass transit waiting areas in Chicago | What do you think your chances are of getting AIDS? | Anonymous paper survey | Yes | IDU (1 year) | Women at higher risk estimated that they were at greater risk for AIDS |

| 4 point scale ranging from: I will never get AIDS to I know I will get AIDS | |||||||

| Goldman | 1993 | 602 men and women from University of Rhode Island | 4 question composite score: I am currently at risk for AIDS; thought of getting AIDS does not worry me; I sometime suspect that I am exposed to AIDS; I have had intercourse with someone in the last 10 years who could have exposed me to AIDS | Written questionnaire | Yes | None | Perceived risk negatively related to AIDS preventive behavior |

| Definitely false; probably false; probably true; definitely true | |||||||

| Klepinger | 1993 | 3321 men 20–39 years old; national sample | Perceived personal HIV-infection risk: | Face-to-face interview | Yes (4 weeks) | Yes (4 weeks) | Weak association between perceptions of risk and HIV-related risk-behavior |

| None; some; ≥50% | |||||||

| Kline | 1993 | 242 women from drug treatment centers in 3 high HIV prevalence cities in northern New Jersey | How likely is it that you will become infected with AIDS in the next 12 months? | Face-to-face interview | Yes (4 weeks) | Yes | Congruence with drug use, but incongruence with sexual behavior |

| 4 point scale: Very unlikely; somewhat unlikely; somewhat likely; very likely | |||||||

| van der Velde | 1994 | 1318 participants from 4 HIV risk stratified samples from Amsterdam | How do you estimate the chance that you will become infected with AIDS virus in the next 2 years? | Written questionnaire | Yes (4 months) | No | Modest correlation of perception of risk and previous sexual experiences in a high risk population |

| Scale from 0–100% chance | |||||||

| Bosga | 1995 | 165 homosexual men who practice unprotected anogenital intercourse with steady and non-steady partners | Not available | Not available | Not available | Not available | Majority of men who engage in risky behaviors within their primary relationship do not appraise their behaviors as risky |

| Not available | |||||||

| Dolcini | 1996 | 1770 men and women 18–44 years old living in San Francisco with high rates of STDs and drug use | How likely do you think it is that you will eventually get AIDS? | Face-to-face interview | Yes | No | Only having a sexual partner who was an IDU was associated with self-perceived risk |

| 1 = definitely not possible; 2 = very unlikely; 3 = somewhat unlikely; 4 = very worried or concerned |

|||||||

| Fitchtner | 1996 | 51,359 patients from 25 STD clinics in Illinois | Do you have any reason to be concerned that you may have been exposed to HIV from a sex or needle-sharing partner? | Face-to-face interview | Yes | Yes (lifetime) | 65% with assessed risk did not perceive risk |

| Yes or no | |||||||

| Steers | 1996 | 424 undergraduates from 6 California schools | My chances of contracting HIV are low | Anonymous written questionnaire | Yesa | No | Perceived susceptibility predicted many safer-sex behaviors |

| 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree | |||||||

| Brown | 1998 | 140 random sample of IDUs attending methadone clinics and needle exchanges in New York City | If you do not know your HIV status or if you have tested negative, how would you rate your risk of acquiring HIV? | Face-to-face structured interview | Yesa | No | AIDS risk perception was not a significant predictor of condom use |

| 0 = none; 1 = small; 2 = moderate; 3 = large; 4 = great | |||||||

| Cummings | 1999 | 142 African American low-income women; not considered high-risk | Are you worried about getting AIDS? | Semi-structured 1-on-1 interviews | Yes | No | Worried and non-worried women were equally likely to report risk behaviors |

| Yes or no | |||||||

| Weinreb | 1999 | 220 homeless and 216 low-income mothers living in Massachusetts | Do you perceive your HIV risk to be: | Multi-session interview format | Yes | Yes (2 years) | Among high-risk women 75% believed themselves to be a low- or no-risk for HIV |

| Non-existent; low; medium; high | |||||||

| Stein | 2000 | 1049 homeless, impoverished, minority, and/or IDU men and women in Los Angeles | 1. I've already done plenty that could have exposed me to AIDS; 2. I've never done anything that could give me AIDS; 3. My chances of getting AIDS are great; 4. I don't think I'm at risk for AIDS; 5. Rating of chances of getting AIDS | Face-to-face interview | Yes | Yes | Composite score of perceived risk and IDU has congruency, but sexual risk does not |

| Statements 1–4 scored 1–5: 1 = disagree strongly to 5 = agree strongly; 5th question scored 1 = no chance 4 = high chance |

|||||||

| Maurier | 2000 | A range of 1204–1277 participants over five periods representative of Alberta | What do you think your choices are of getting HIV or AIDS? | Telephone interview | Yes (2 years) | Yes | Congruency between self-perceived risk and number or partners varied by survey and year |

| 1 = none; 2 = low; 3 = medium; 4 = high | |||||||

| Amadora-Nolasco | 2001 | 360 registered and 360 freelance sex workers | Do you think you have a chance of getting HIV/AIDS or do you think there is a possibility for you to be infected? | Face-to-face interview | Yes (6 months) | No | For freelance sex workers associated perceived risk and number of sex partners and condom usage in selected populations |

| Yes; no; don't know | |||||||

| Holtzman | 2001 | Random sample of 18- to 49-year-olds in the United States | Perceived risk of HIV infection: | Telephone interview | Yes | Yes (1 year) | Good agreement between measure of actual HIV risk and perceptions of risk |

| High; medium; low; none | |||||||

| Schröder | 2001 | 666 Black and 626 white single low-income women from OB/GYN clinic in the midwest | Own perceived risk of getting AIDS | Face-to-face interview | Yes (6 months) | No | Lack of risk perception correlated with lack of sexual protective behaviors |

| 1 = no risk; 2 = low risk; 3 = moderate risk; 4 = high risk |

|||||||

| Klein | 2003 | 250 urban economically disadvantaged women in Atlanta | What do you think your chances are of getting the AIDS virus? | Female interviewer; Face-to-face | Yes (90 days) | Yes (30 days) | Incongruency among lower-risk perception group |

| No chance or at least some chance | |||||||

| Theall | 2003 | 183 mostly African American women in Atlanta | What do you think are the chances of your getting the AIDS virus? | Female interviewer; Face-to-face | Yesa | Yes | Relationship between report and perceived risk with some incongruence |

| 0 = none; 1 = low; 2 = medium; 3 = high | |||||||

| Wood | 2004 | 994 IDUs in Vancouver | Compared to other drug users in Vancouver, how likely do you think you are to get infected with HIV/AIDS? | Face-to-face interview | Yes (6 months) | Yes (6 months) | Inconsistent relationship between IDU behavior and risk-perception |

| Much more likely; a bit more likely; about the same; less likely | |||||||

| Takahashi | 2005 | 2911 sexually active adults 18–50 years old in Florida, Montana, Ohio, and South Dakota | What are your chances of getting infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS? | Telephone interview | Yes (1 year) | Yes (1 year) | Most individuals who report behaviors that increase their risk for HIV do not consider themselves to be at risk and have not been recently tested |

| High; medium; low; none | |||||||

| Prata | 2006 | 7817 sexually experienced 15- to 24-year-olds in Mozambique | Risk of HIV: | Household survey | Yes | No | 27% of women and 80% of men with self-perceived no or small risk were actually at moderate or high risk |

| None; small; moderate; high; or not known | |||||||

| Lapidus | 2006 | 222 American Indians and Alaska Natives in 4 counties; Oregon or Washington State | Perceived risk of HIV infection: | Interview | Yes | Yes | 44% reporting high-risk behaviors reported themselves at low or no risk of HIV |

| High; medium; low; none; don't know | |||||||

| MacKellar | 2007 | 2788 MSM in 6 US cities | Which number best describes how likely it is that you will become HIV+ today? Your lifetime? | Interviewed with a questionnaire | Yes | Yes | Although some congruency, a substantial proportion of those with risk behaviors perceived a low-risk for infection |

| 1 = very unlikely; 2 = unlikely; 3 = somewhat likely; 4 = likely; 5 = very likely |

|||||||

| Cole | 2008 | 529 women recruited from a domestic violence court | Which statement best describes your chance of getting HIV? | Interview; event calendar | Yes (1 year) | Yes | Congruence in some but not all risk behaviors |

| 0 = no chance; 1 = 50% chance; 2 = 75% chance |

Indicates multiple time frames provided in the study for participants to report their behaviors.

In this investigation, we examined the congruency between self-perceived and reported HIV risk among ED patients in a traditional lower HIV prevalence and risk group (heterosexuals who have not injected drugs). If evidence of incongruency between self-perception and report of HIV risk in this traditional lower risk group exists, it could indicate the need for revisions in HIV testing practices and procedures in EDs, as well as raise awareness among providers that traditionally lower-risk patients might also benefit from testing in the ED. This research attempts to address some of the limitations of previous studies conducted in other settings on this topic and improve understanding of the relationship between self-perceived and reported HIV risk among traditional lower-risk patients who would be tested for HIV by: (1) restricting the scope of questionnaires to assess self-perceived and reported risk for HIV and not AIDS; (2) avoiding contamination of measuring self-perceived risk by purposely querying about self-perceived HIV risk before asking participants to report their HIV risk-taking behaviors; (3) including questions about sexual, as well as drug-related HIV risk behaviors, in the reported HIV risk assessments to gain a more complete understanding of reported HIV risk; (4) using a consistent time frame for asking about reported HIV risk behaviors that is commensurate with the period in which an HIV infection could be discovered; (5) querying about current risk for having an HIV infection in regards to self-perceived HIV risk, instead of future or previous risk (which is relevant in the context of HIV testing); (6) evaluating this topic in a clinically appropriate traditional lower HIV risk group (non-MSM, non-IDU ED patients) for whom HIV testing and concerns about incongruency between self-perceived and reported HIV risk is crucial to elucidate; and (7) using survey methods that encourage the veracity of responses to sensitive questions.

Methods

Study setting and population

This cross-sectional study included a random sample of 18- to 64-year-old subcritically ill or injured patients at a large urban academic ED in New England about their HIV testing history, self-perceived risk for currently being infected with HIV, and reported HIV risk-taking behaviors within the past 10 years. This investigation was part of a larger study. Descriptions of the study methods have been previously published, and are briefly summarized here.45 The participation selection process included randomly selecting: (1) 16 dates per month during which we conducted the study over a 12-month period; (2) the timing of the 8-h shifts that we conducted the study on those 16 dates per month (day, evening, or night shifts); and (3) the patients we approached to assess their study eligibility during those shifts. Shifts were elected based on a weighting scheme that reflected the typical patterns of the ED patient registrations during a typical 24-h period (40% were day, 50% evening, and 10% night shifts). During each shift, we randomly selected 80% of the patients present in the ambulatory care and urgent care areas of the ED to approach for possible inclusion in the study. Patients in the psychiatric/substance abuse care and critical care areas were not assessed for study eligibility.

Study protocol

A research assistant assessed the eligibility of ED patients randomly selected for possible study inclusion by reviewing their ED medical records and then confirming their eligibility through an in-person assessment. ED patients whose medical record indicated they were not eligible for the study were not interviewed. Inclusion criteria were: age 18–64 years; English-speaking; not critically ill or injured; not incarcerated, under arrest or on home confinement; not presenting for evaluation of a psychiatric illness; not known to be infected with HIV; not participating in an HIV vaccine trial; not intoxicated; and not having a physical disability or mental impairment that prevented them from providing consent to be in the study. All patients who were confirmed as eligible were invited to enroll. No incentives were offered to participants. ED staff were not permitted to refer patients for inclusion in the study.

Participants were interviewed about their demographic characteristics and HIV testing history using instruments developed for and employed in a prior study.45 Next, using an audio computer-assisted self-interviewer (ACASI), participants completed the “HIV risk questionnaire”. The “HIV risk questionnaire”, which was created by the study authors and underwent a rigorous development process that included cognitive-based assessments and pilot testing, has been described in detail previously.45 Participants were first asked to consider their self-perceived risk of currently having an HIV infection (“In your opinion, what is your risk of being infected with HIV?”). Response options to this question were provided on a five-point scale presented in descending order ranging from 4 “I am very much at risk” to 0 “I am not at risk”. Afterwards, participants responded to multiple-choice, closed-end questions that asked them to report their injection-drug and sexual HIV risk-taking behaviors within the past 10 years. Participants were asked if they had engaged in selected behaviors over a 10-year period because this reflects the usual time during which an HIV infection is detected through an HIV test or AIDS manifests (and HIV would be diagnosed). Because males and females differ in the types of HIV sexual risk-taking behaviors that they can engage in (e.g., females can have unprotected sex with MSMs), the reported HIV risk-taking behavior questions were gender-specific. Accordingly, there were a total of 16 possible reported HIV risk-taking behavior questions for females and 26 for males. Scores were not calculated for respondents who refused to answer any part of the questionnaire. A higher score represented a greater number of HIV risk behaviors; details regarding scoring can be found in previously published studies.45,46

Data analysis

All data analyses were conducted using STATA 11 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). The results of the study eligibility assessment and enrollment procedures were summarized and diagramed per the STROBE recommendations.47 Study participants who refused to answer questions and those who did not know the answers to questions about their demographic characteristics were excluded. Missing data were not imputed. For this investigation, participants who self-identified as MSM or who self-reported IDU were not included in the analysis, because the intent was to evaluate the relationship of self-perceived and self-reported HIV risk among a traditionally lower HIV prevalence and risk group (heterosexuals who have not injected drugs). Summary statistics of demographic characteristics, including the median and interquartile range (IQR) for age were calculated for both genders.

As we did in prior studies, we calculated a reported HIV risk score to summarize the responses from the “HIV risk questionnaire”.45,46 Higher scores represented a greater number of reported HIV risk behaviors. The reported HIV risk score was the sum of each participant's responses divided by the total possible points for all questions. The maximum possible scores were 36 for females and 61 for males. Participants were stratified into two groups by gender based upon their risk score: those who reported no HIV risk and those who reported any HIV risk. Among those who reported any HIV risk, these participants were further stratified into terciles according to their risk score, which indicated increasing levels of reported HIV risk. Summary statistics were calculated for the reported risk score (mean, median, and IQR). Risk scores (reported risk) were compared to the level of self-perceived HIV risk.

Multivariable linear regression models were constructed comparing self-perceived to log-transformed reported HIV risk scores. Models were adjusted for participant age, HIV testing history, and partner status (single/never married, currently married, divorced/widowed/separated) because these variables were related to self-perceived and reported risk in univariable analyses. Beta coefficients (β) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated.

Results

Description of study participants

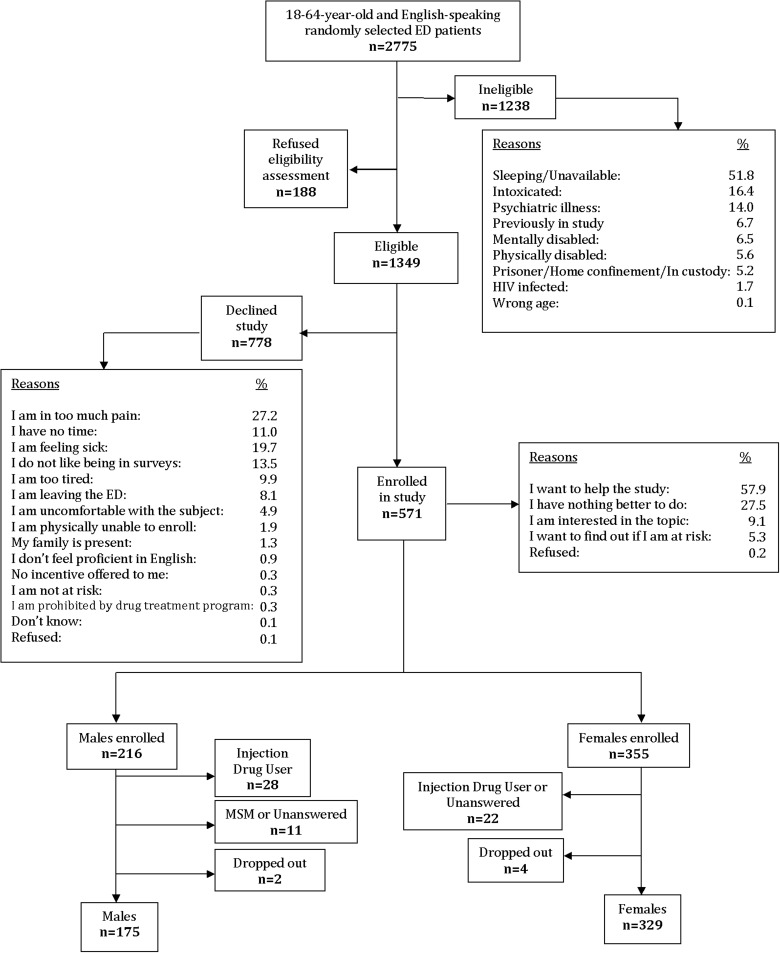

Figure 1 depicts the results of the study eligibility assessment and enrollment procedures. After excluding participants who reported IDU or male–male sex, 175 males and 329 females were retained for analysis. Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of participants by gender. The majority of the females and males were white, never married (single), had private health care insurance, 12 years or fewer of formal education, and had previously been tested for HIV. Based upon the “HIV risk questionnaire”, females had an HIV risk score mean of 0.19 (median 0.16 [IQR 0.11–0.25]), while males had an HIV risk score mean of 0.10 (median 0.09 [IQR 0.07–0.14]).

FIG. 1.

Eligibility assessment and enrollment flow diagram.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

| |

|

Participants enrolled in study |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| All eligible participants | Males | Females | |

| Demographic characteristics | N=571 | N=175 | N=329 |

| Median age in years (IQR) | 29 (22–43) | 34 (23–46) | 28 (22–39) |

| % | % | % | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 62.4 | 60.0 | 62.0 |

| White, Hispanic | 14.9 | 12.0 | 17.0 |

| Black, African American | 13.8 | 18.0 | 13.0 |

| Black, Hispanic | 6.3 | 5.0 | 12.0 |

| Asian/Middle Eastern | 1.9 | 4.0 | 1.0 |

| Native Hawaiian, Other Pacific Islander | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Partner status | |||

| Married | 22.4 | 28.5 | 20.4 |

| Divorced | 10.5 | 7.4 | 11.6 |

| Widowed | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.6 |

| Separated | 3.2 | 5.0 | 2.1 |

| Never married | 48.3 | 47.4 | 49.2 |

| Unmarried couple | 14.9 | 11.4 | 16.1 |

| Insurance status | |||

| Private | 41.3 | 44.0 | 38.0 |

| Governmental | 36.3 | 31.4 | 43.8 |

| Private and governmental | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| None | 21.5 | 24.6 | 13.0 |

| Don't know | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Years of formal education | |||

| 1–8 years | 3.3 | 4.0 | 1.8 |

| 9–11 years | 15.8 | 17.7 | 14.5 |

| 12 years or General Equivalency Diploma (GED) | 29.3 | 30.2 | 25.8 |

| College 1–3 years | 31.5 | 26.2 | 35.5 |

| College 4 years/graduate school | 20.0 | 21.7 | 21.9 |

| Don't know | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| Ever tested for HIV | |||

| Previously | 66.9 | 55.4 | 70.2 |

| Never | 32.4 | 44.0 | 28.9 |

| Don't know | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| Number of unprotected sexual partners of the opposite sex | |||

| 21 or more different partners | 3.0 | 1.1 | 2.1 |

| 11–20 different partners | 5.2 | 4.6 | 2.7 |

| 6–10 different partners | 6.0 | 5.1 | 7.3 |

| 2–5 different partners | 57.1 | 30.2 | 35.9 |

| 1 partner | 34.9 | 36.6 | 36.8 |

| Always have sex with condoms | 4.9 | 8.0 | 4.0 |

| Don't know | 0.3 | 0.5 | 10.9 |

Relationship of self-perceived and reported HIV risk

Among all females, 50.5% perceived that they were “not at risk” for HIV and 10.9% reported no HIV risk behaviors. Among all males, 50.9% perceived that they were “not at risk” for HIV and 12.6% reported no HIV risk behaviors. Table 3 depicts the proportions of all participants by gender and by their level of self-reported risk, and according to whether they reported any versus no HIV risk behaviors, and by tercile of reported HIV risk. Of the 166 females and 89 males who perceived themselves not to be at risk for HIV, 9.6% of females and 7.9% of males were in the highest quartile of reported HIV risk. In addition, only 16.9% of females and 15.7% of males who self-perceived themselves to be “not at risk” for HIV reported no behavioral risk factors. After removing women who assessed their self-perceived risk for HIV as “not at risk” and who reported no HIV-risk behaviors (n=28), there were 138 remaining women who rated themselves as “not at risk” for HIV despite having self-reported risk behaviors. Of these 138 women, 51.4% (n=71) were in the lowest tercile, 37.0% (n=51) in the middle tercile, and 11.6% (n=16) in the highest tercile of self-reported HIV risk behaviors. After removing men who assessed their self-perceived risk for HIV as “not at risk” and who reported no HIV-risk behaviors (n=14), there were 100 men remaining who rated themselves as “not at risk” for HIV despite having self-reported risk behaviors. Of these 100 men, 69.3% (n=52) were in the lowest tercile, 21.3% (n=16) in the middle tercile, and 18.3% (n=32) in the highest tercile of self-reported HIV risk behaviors, respectively.

Table 3.

Self-Perceived Versus Reported HIV Risk of Study Participants

| |

|

Self-perceived risk for HIV |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reported HIV risk | Not at risk | Not much at risk | Somewhat at risk | Pretty much at risk | Very much at risk |

| Females (n=329) | |||||

| No reported HIV risk (n=36; 10.9%) | 28 (8.5%) | 6 (1.8%) | 2 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Lowest tercile of reported HIV risk (n=104; 31.6%) | 71 (21.6% | 23 (7.0%) | 6 (1.8%) | 2 (1.0%) | 2 (1.0%) |

| Middle tercile of reported HIV risk (n=114; 34.7%) | 51 (15.5%) | 45 (13.7%) | 12 (3.6%) | 5 (1.5%) | 1 (0.0%) |

| Highest tercile of reported HIV risk (n=79; 24.0%) | 16 (4.9%) | 34 (10.3%) | 23 (7.0%) | 4 (1.2%) | 2 (1.0%) |

| Males (n=175) | |||||

| No reported HIV risk behaviors (n=22; 12.6%) | 14 (8.0%) | 5 (2.9%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.0%) |

| Lowest tercile of reported HIV risk (n=78; 44.6%) | 52 (29.7%) | 22 (12.6%) | 2 (1.1%) | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (1.0%) |

| Middle tercile of reported HIV risk (n=43; 25.6%) | 16 (9.1%) | 18 (10.3%) | 7 (4.0%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Highest tercile of reported HIV risk (n=32; 18.3%) | 7 (4.0%) | 15 (7.0%) | 7 (4.0%) | 1 (1.2%) | 2 (1.0%) |

In the multivariable linear regression models which controlled for age, HIV testing history, and partner status, there was a weakly increasing relationship among females between greater self-reported HIV risk (the outcome) and higher levels of self-perceived risk [self-perceived risk levels: “not at risk” (reference), “not much” β 0.06 (0.04, 0.08), “somewhat” β 0.10 (0.07, 0.13), “pretty much” β 0.04 (–0.2, 0.11), and “very much” at risk β 0.14 (0.05, 0.23)]. The relationship was similar among males [“not at risk” (reference), “not much” β 0.02 (0.01, 0.04), “somewhat” β 0.03 (0.01, 0.06), “pretty much” β 0.06 (0.01, 0.12), and “very much” at risk β 0.04 (-0.02, 0.09)].

Discussion

The results of this investigation suggest that traditionally lower HIV prevalence and risk ED patients (heterosexuals without a history of IDU) inaccurately self-perceive their risk for having an HIV infection as compared to their reported HIV risk-taking behaviors. As shown in this study, both males and females did not demonstrate consistent congruence between self-perceived HIV risk and reported HIV risk behaviors. Both genders underestimated their risk for HIV, as only 17% of females and 15.7% of males of those who rated themselves as “not at risk” for HIV also had no self-reported HIV risk behaviors. In other words, 83% percent of female and 84.3% of male participants who perceived themselves not to be at risk had engaged in HIV risk-taking behaviors.

Underlying reasons for incongruency between self-perceived and reported HIV risk were not investigated in this study, but have been considered elsewhere. Some authors have compared risk-stratified groups (high vs. low) in terms of their self-perceived versus reported risk for HIV in an attempt to understand reasons for incongruency. For example, Brown48 compared self-perceived risk to reported risk for HIV among college students and IDUs, while van der Velde et al.36 assessed these same constructs among MSMs in low and high sexual promiscuity groups and heterosexual low and high sexual promiscuity groups. In both studies, the authors found that a significant proportion of participants rated their self-perceived HIV risk as low despite their high-risk behaviors. Researchers have hypothesized that optimistic bias (when a person to believe that they are less at risk for a negative event when compared to others), denial and distancing (refusal to accept a situation or events and refusing to think about unpleasant thoughts or facts), and downward comparison (when a person compares himself to another group or person to dissociate himself from perceived similarities) explain the incongruency between reported behavior and self-perceived risk.3,40,48

Additional studies hypothesize that other factors such as HIV/AIDS knowledge,8,22,23,38,39,41 self-esteem,8,40 self-efficacy,27,31,32,49 strength of support systems,8,49 religiosity,40 history of physical or sexual abuse,5,22,49 perceived control in the relationship,50 anchoring on previously negative test results,4 and personal knowledge of someone with AIDS26,41,49 are factors that might impact self-perceived risk, reported risk, and congruency between self-perceived and reported risk, as well as resultant risk-taking behaviors. Another proposed reason for incongruencies observed in studies between self-perceived HIV risk and reported HIV risk could be the historical targeting of specific populations (e.g., MSMs, IDUs) during HIV educational campaigns that might perpetuate the belief that only the “cultural other” is susceptible to HIV/AIDS.25,48,51 Further, previous HIV educational campaigns that primarily focus on relatively infrequent high-transmission behaviors (e.g., IDU) might give the impression that frequent low-transmission behaviors (e.g., unprotected sex among heterosexuals who are not IDUs) are an unimportant factor in HIV/AIDS transmission.25 Regardless of the reason for incongruency, the repercussions of incongruency seem apparent in a recent study by Nunn et al.52 that found that 67% of seropositive outpatient clinics patients in Philadelphia identified their self-perceived risk as zero or low.

The results of this investigation should serve as a cautionary message to ED clinicians not to rely upon patients' self-perception of risk when deciding how to select patients or choosing whether they should conduct HIV testing. Clinicians also can be reminded by the study results that even traditionally lower HIV risk groups do in fact have substantial risk for an HIV infection, which adds support for broadening the scope of HIV diagnostic and screening in EDs. The incongruency between self-perceived HIV risk and self-reported HIV risk behaviors also would at first seem to support CDC's recommendation that initial HIV screening and diagnostic testing in the ED setting be performed using an opt-out approach without conducting HIV risk assessments. The advantages of an opt-out versus an opt-in approach are that ED patients might be more inclined to be tested, because acceptance of testing is passive, and patients are more likely to agree when testing appears to be a recommended routine procedure. Some advantages of not basing testing on HIV risk assessments are that time and costs could be saved (which would allow more people to be tested), those without traditional risk factors might more likely be tested, and patients would not need to report their risk-taking behaviors.

However, it should be recalled that ED patients typically decline HIV testing out of a belief that they are not at risk for an infection,53–65 and many patients who decline testing do have significant risk for having an undiagnosed infection.21 When an opt-out approach without a risk assessment is used by ED clinicians, patients likely conduct their own risk assessment internally and perhaps subconsciously, and maybe inaccurately. They might self-perceive that they are not at risk for HIV, when they in fact have engaged in HIV risk-taking behaviors. If patients who decline screening are then not asked about their risk-taking behaviors, but would have reported risk-taking behaviors had they been asked, then an opportunity to identify an HIV infection would have been lost. As such, a potential pitfall of not using risk assessments might be that patients do not recognize that their behaviors are putting them at risk for HIV. Furthermore, when ED clinicians do not query their patients about their HIV-risk behaviors and instead rely upon their patients' self-perceived risk of HIV, they miss an opportunity to identify mistaken beliefs about risk, which could perpetuate risk-taking behavior and the spread of HIV, as well as miss an opportunity to encourage testing, make the diagnosis and link patients to care and treatment.

On a systems and HIV testing policies and procedures level, the problem of incongruency and the possibility of a failure to uncover it should be considered when deciding how screening should be conducted in EDs. Of course, EDs need to balance utilizing streamlined methods that enable en masse screening against optimal accuracy in identifying infections and resources available to conduct screening. Nevertheless, our results at least caution EDs when conducting HIV screening not to use self-perceived HIV risk as an adequate reason to defer conducting an HIV test, particularly among those in traditionally lower HIV risk and prevalence groups.

The extent to which there are lost opportunities for identifying HIV infections when risk is not assessed is unknown, yet it is understood that infections are being missed in the ED setting. Lyons et al.66 demonstrated that there were missed HIV diagnoses in 76 patients who visited an urban academic ED (n=70), an urban community ED (n=9), and a suburban ED (n=4) in the year prior to diagnosis. Another study performed by Czarnogorski et al.62 demonstrated the prevalence of HIV to be 2.74 times higher (95% CI 1.44–5.18) in those who declined a screening test than those who accepted routine HIV screening in an urban ED. They also observed that the most popular reason for declining testing was no self-perceived risk for HIV, even among the one-third of participants with a positive HIV test result.

The findings from this investigation align with results of previous studies that mostly found incongruency or a weak relationship between self-perceived and self-reported risk for HIV (Table 1). However, previous studies may not have produced a consistent message regarding HIV self-perceived risk and reported HIV risk behaviors because of variations in data collection or limitations in study designs, which have included: either asking about HIV,5,12,26,28,30,31,33,34,37,42,45 AIDS,8,22,23,25,27,32,35,36,39,40,43,49 or both;24,29,38 only asking about either sexual or drug-related behaviors in their questionnaires but not both,23,26,27,31,32,35,36,38,42,43 or asking about both types of risk-taking behaviors;5,8,12,22–33,35–38,40,42–44,49 varying the time frame in questions asking about HIV or AIDS risk behaviors (ranging in these studies from 4 weeks to 10 years),22,24,25,30,45,48,67 changing the time frame with the type of behavior queried about (e.g., sexual or IDU),8,30,33,35,43 not specifying time frame,22,31,40,42 or using different time frames within the same questionnaire for sexual and IDU risk-taking behaviors.24,37,39,49,68 Further variations include differences in the time frame that participants were asked to gauge their self-perceived HIV risk; some asked about current risk for HIV (or AIDS),23,27,28,31,37 while others asked participants to evaluate future or lifetime risk.5,12,22,24,25,35,36,40,48,49,69 Some studies used different time frames to measure self-perceived risk within the same survey for different risk-taking behaviors.4,8,27,38 Means of quantifying risk also varied across studies from using categories (e.g., “high,” “medium,” or “low”)8,12,23–33,35–40,42–44 percentages (e.g., 0–100%),5,36 and scales to indicate self-perceived risk (e.g., zero to ten on a likelihood scale),23,37,49,70 or a combination of methods to quantify self-perceived risk.22,41 The types of populations enrolled in these studies also varied from traditional high-risk populations (e.g., MSM, drug users, STD clinic patients)8,28,29,31,34,37,38,48–50 to selected specific populations, such as minorities,39,69,70 urban and economically disadvantaged citizens,22,25,32,43,44 or victims of intimate partner violence.5 Studies also have varied in how the data were collected (telephone interview,12,23,24,33,70 face-to-face interview,8,22,25,28,31,35,38–41,43,44,48,49,70 or “paper and pencil” questionnaire27,37,42,50), which influences the questions asked, response options, ability of participants to seek clarification, interpretation and categorization of responses that were free-form, and validity of responses due to the sensitive nature of the topics.

This study improves on previous research on this topic by attempting to evaluate the relationship between self-perceived and reported HIV risk with carefully planned methodology in the context of HIV screening in a defined setting and relevant population. This study uses a consistently applied and explicitly stated time frame for both drug and sexual risk behaviors; a time frame that is commensurate with the period HIV/AIDS is typically diagnosed; the ACASI method of questioning to improve veracity of responses and understanding of the study questions; and acknowledges risk differences by gender. Regardless of these advantages, there were several limitations to this investigation. Despite attempting to obtain a representative sample of ED patients, this study may not be applicable to other EDs with different patient demographic characteristics. Second, the “HIV risk questionnaire,” though rigorously developed, has not been evaluated on its ability to predict the presence of an HIV infection. Therefore, although assumed in this study, the risk score may not truly reflect risk for the presence of an HIV infection. Additionally, although the models comparing self-perceived and reported HIV risk adjusted for a history of HIV testing, self-perceived risk of HIV infection could not be assessed in relationship to current or previous HIV testing. Participants who partake in high-risk HIV behaviors might correctly identify themselves as being at low-risk for having an HIV infection if they recently had a negative test [“In your opinion, what is your risk of being infected with HIV?” Choose a number from 4 (“I am very much at risk”) to 0 (“I am not at risk”)]. Finally, we did not specify a population with whom the participants should compare themselves when answering the questions about their self-perceived risk or HIV (i.e., risk of being infected with HIV relative to others in their community, other ED patients etc.), which left the participants without a standard to assess their level of self-perceived risk.

Future research should focus on interventions to optimize opportunities for HIV screening in EDs in light of this observed incongruency between self-perceived and reported HIV risk, which has implications for patient–clinician encounters as well as policies, procedures, and practices regarding HIV testing and screening in EDs and other healthcare settings. Potential solutions include routine patient-performed reporting of HIV risk-taking behaviors linked to electronic health records that can be reviewed during the patient encounter, and targeted interviews with risk assessments and interventions among those who decline HIV screening. The value of these changes should be evaluated in future studies. In a prior study, we found that ED patients modestly increased their self-perceived HIV risk when queried about their reported HIV risk behaviors, and that this increase was associated with greater uptake of HIV screening.45,71 However, how to convince patients who decline testing to be tested and improve the accuracy of self-perceived risk is not yet known. Future research should evaluate the effectiveness of these approaches, as well as optimal methods for reporting HIV risk, the content of these assessments, the risks that should be evaluated given changes in the HIV epidemic, how well such risk assessments predict acquisition of an HIV infection, and interventions to encourage patients who decline testing even though they are at risk to be tested. Further, standardization across studies in how self-perceived and reported HIV risks are evaluated would be helpful in comparing results in different settings and populations. Finally, future studies can evaluate whether risk assessments might provide opportunity for interventions to reduce incongruencies between self-perceived risk and reported HIV risk behaviors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the research assistants, staff, and patients at Rhode Island Hospital who made this study possible. This research was supported by a career development grant to Dr. Merchant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious diseases (K23 A1060363).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Rosenstock I. Why people use health services. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44:94–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers R. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J Psychol Interdiscip Appl. 1975;91:93–114. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerrard M. Gibbons FX. Bushman BJ. Relation between perceived vulnerability to HIV and precautionary sexual behavior. Psychol Bull. 1996;119:390–409. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacKellar DA. Valleroy LA. Secura GM, et al. Unrecognized HIV infection, risk behaviors, and perceptions of risk among young men who have sex with men: Opportunities for advancing HIV prevention in the third decade of HIV/AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:603–614. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000141481.48348.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole JLT. Shannon L. Self-perceived risk of HIV among women with protective orders against male partners. Health Social Work. 2008;33:287–298. doi: 10.1093/hsw/33.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mill JE. Jackson RC. Worthington CA, et al. HIV testing and care in Canadian Aboriginal youth: A community based mixed methods study. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyons MS. Lindsell CJ. Ledyard HK. Frame PT. Trott AT. Emergency department HIV testing and counseling: An ongoing experience in a low-prevalence area. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein JA. Nyamathi A. Gender differences in behavioural and psychosocial predictors of HIV testing and return for test results in a high-risk population. AIDS Care. 2000;12:343–356. doi: 10.1080/09540120050043007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson JE. Mosher WD. Chandra A. Measuring HIV risk in the U.S. population aged 15–44: Results from Cycle 6 of the National Survey of Family Growth. Adv Data. 2006:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kellerman SE. Lehman JS. Lansky A, et al. HIV testing within at-risk populations in the United States and the reasons for seeking or avoiding HIV testing. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31:202–210. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200210010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wurcel A. Zaman T. Zhen S. Stone D. Acceptance of HIV antibody testing among inpatients and outpatients at a public health hospital: A study of rapid versus standard testing. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19:499–505. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi TJK. Bradly KA. A population-based study of HIV testing practices and perceptions in 4 U.S. states. J Gen Int Med. 2005;20:618–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liddicoat RV. Losina E. Kang M. Freedberg KA. Walensky RP. Refusing HIV testing in an urgent care setting: results from the "Think HIV" program. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20:84–92. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Branson BHH. Lampe MA. Janssen RS. Taylor AW. Lyss SB. Clark JE. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR. 2006;55:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Branson BHH. Lampe MA. Janssen RS. Taylor AW. Lyss SB. Clark JE. Recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR. 2006;55:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoover JB. Tao G. Heffelfinger JD. Monitoring HIV testing at visits to emergency departments in the United States: Very low rate of HIV testing. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62:90–94. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182742933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rothman RE. Hsieh YH. Harvey L, et al. 2009 US emergency department HIV testing practices. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:S3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.016. e1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrin J. Wesolowski LG. Heffelfinger JD, et al. HIV screening practices and hospital characteristics in the US, 2009–2010. Public Health Rep. 2013;128:161–169. doi: 10.1177/003335491312800306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berg LJ. Delgado MK. Ginde AA. Montoy JC. Bendavid E. Camargo CA., Jr. Characteristics of U.S. emergency departments that offer routine human immunodeficiency virus screening. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:894–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haukoos JS. Hopkins E. Hull A, et al. HIV testing in emergency departments in the United States: A national survey. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:S10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.033. e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ubhayakar ND. Lindsell CJ. Raab DL, et al. Risk, reasons for refusal, and impact of counseling on consent among ED patients declining HIV screening. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weisman CS. Nathanson CA. Ensminger M. Teitelbaum MA. Robinson JC. Plichta S. AIDS knowledge, perceived risk and prevention among adolescent clients of a family planning clinic. Fam Plann Perspect. 1989;21:213–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prohaska TR. Albrecht G. Levy JA. Sugrue N. Kim JH. Determinants of self-perceived risk for AIDS. J Health Soc Behav. 1990;31:384–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maurier WL. Northcott HC. Self-reported risk factors and perceived chance of getting HIV/AIDS in the 1990s in Alberta. Can J Public Health. 2000;91:340–344. doi: 10.1007/BF03404803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein H. Elifson KW. Sterk CE. "At risk" women who think that they have no chance of getting HIV: Self-assessed perceived risks. Women Health. 2003;38:47–63. doi: 10.1300/J013v38n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prata N. Morris L. Mazive E. Vahidnia F. Stehr M. Relationship between HIV risk perception and condom use: Evidence from a population-based survey in Mozambique. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2006;32:192–200. doi: 10.1363/3219206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldman JA. Harlow LL. Self-perception variables that mediate AIDS-preventive behavior in college students. Health Psychol. 1993;12:489–498. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.6.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fichtner RR WR. Johnson WD. Rabins CB. Fishbein M. Influence of perceived an assessed risk on STD clinic clients' acceptance of HIV testing, return for test results and HIV serostatus. Psychol Health Med. 1996;1:83–98. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood E. Li K. Miller CL, et al. Baseline self-perceived risk of HIV infection independently predicts the rate of HIV seroconversion in a prospective cohort of injection drug users. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:152–158. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lapidus JA. Bertolli J. McGowan K. Sullivan P. HIV-related risk behaviors, perceptions of risk, HIV testing, and exposure to prevention messages and methods among urban American Indians and Alaska Natives. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18:546–559. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.6.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown EJ. Female injecting drug users: Human immunodeficiency virus risk behavior and intervention needs. J Prof Nurs. 1998;14:361–369. doi: 10.1016/s8755-7223(98)80078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schroder KE. Hobfoll SE. Jackson AP. Lavin J. Proximal and distal predictors of AIDS risk behaviors among inner-city African American and European American women. J Health Psychol. 2001;6:169–190. doi: 10.1177/135910530100600207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holtzman D. Bland SD. Lansky A. Mack KA. HIV-related behaviors and perceptions among adults in 25 states: 1997 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1882–1888. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bosga MB. de Wit JB. de Vroome EM. Houweling H. Schop W. Sandfort TG. Differences in perception of risk for HIV infection with steady and non-steady partners among homosexual men. AIDS Educ Prev. 1995;7:103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dolcini MM. Catania JA. Choi KH. Fullilove MT. Coates TJ. Cognitive and emotional assessments of perceived risk for HIV among unmarried heterosexuals. AIDS Educ Prev. 1996;8:294–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Velde FW. van der Pligt J. Hooykaas C. Perceiving AIDS-related risk: accuracy as a function of differences in actual risk. Health Psychol. 1994;13:25–33. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacKellar DA. Valleroy LA. Secura GM, et al. Perceptions of lifetime risk and actual risk for acquiring HIV among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:263–270. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amadora-Nolasco FAF. Aguilar ET. Trevathan W. Knowledge, perception of risk for HIV, and condom use: A comparison of registered and freelance female sex workers in Cebu City, Philippines. AIDS Behav. 2001;5:319–330. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalichman SC. Hunter TL. Kelly JA. Perceptions of AIDS susceptibility among minority and nonminority women at risk for HIV infection. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:725–732. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Theall K. Perceived susceptibility to HIV among women: Differences according to age. Res Aging. 2003;25:405–432. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klepinger DH. Billy JO. Tanfer K. Grady WR. Perceptions of AIDS risk and severity and their association with risk-related behavior among U.S. men. Fam Plann Perspect. 1993;25:74–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steers WN. Elliott E. Nemiro J. Ditman D. Oskamp S. Health beliefs as predictors of HIV-preventive behavior and ethnic differences in prediction. J Soc Psychol. 1996;136:99–110. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1996.9923032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cummings GL. Battle RS. Barker JC. Krasnovsky FM. Are African American women worried about getting AIDS? A qualitative analysis. AIDS Educ Prev. 1999;11:331–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weinreb L. Goldberg R. Lessard D. Perloff J. Bassuk E. HIV-risk practices among homeless and low-income housed mothers. J Fam Pract. 1999;48:859–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Merchant RC. Clark MA. Langan TJt. Seage GR., 3rd Mayer KH. DeGruttola VG. Effectiveness of increasing emergency department patients' self-perceived risk for being human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected through audio computer self-interview-based feedback about reported HIV risk behaviors. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1143–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merchant RC. Freelove SM. Langan TJT, et al. The relationship of reported HIV risk and history of HIV testing among emergency department patients. Postgrad Med. 2010;122:61–74. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.01.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Elm E. Altman DG. Egger M. Pocock SJ. Gotzsche PC. Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown E. Theoretical antecedents to HIV risk perception. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2000;6:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kline A. Strickler J. Perceptions of risk for AIDS among women in drug treatment. Health Psychol. 1993;12:313–323. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.4.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van der Velde FW. van der Pligt I. Hooykas C. Perceiving AIDS-related risk accuracy as a runction of differences in actual risk. Health Psychol. 1994;13:25–33. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arya M. Kallen MA. Williams LT. Street RL. Viswanath K. Giordano TP. Beliefs about who should be tested for HIV among African American individuals attending a family practice clinic. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26:1–4. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nunn A. Zaller N. Cornwall A, et al. Low perceived risk and high HIV prevalence among a predominantly African American population participating in Philadelphia's Rapid HIV testing program. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:229–235. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glick NR. Silva A. Zun L. Whitman S. HIV testing in a resource-poor urban emergency department. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16:126–136. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.2.126.29391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schrantz SJ. Babcock CA. Theodosis C, et al. A targeted, conventional assay, emergency department HIV testing program integrated with existing clinical procedures. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:S85–88. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.031. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.D'Almeida KW. Kierzek G. de Truchis P, et al. Modest public health impact of nontargeted human immunodeficiency virus screening in 29 emergency departments. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:12–20. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Christopoulos KA. Schackman BR. Lee G. Green RA. Morrison EA. Results from a New York City emergency department rapid HIV testing program. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:420–422. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b7220f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mehta SD. Hall J. Lyss SB. Skolnik PR. Pealer LN. Kharasch S. Adult and pediatric emergency department sexually transmitted disease and HIV screening: programmatic overview and outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:250–258. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.10.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lyss SB. Branson BM. Kroc KA. Couture EF. Newman DR. Weinstein RA. Detecting unsuspected HIV infection with a rapid whole-blood HIV test in an urban emergency department. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:435–442. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802f83d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Silva A. Glick NR. Lyss SB, et al. Implementing an HIV and sexually transmitted disease screening program in an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:564–572. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brown J. Kuo I. Bellows J, et al. Patient perceptions and acceptance of routine emergency department HIV testing. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 3):21–26. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pisculli ML. Reichmann WM. Losina E, et al. Factors associated with refusal of rapid HIV testing in an emergency department. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:734–742. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9837-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Czarnogorski M. Brown J. Lee V, et al. The prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection in those who decline HIV screening in an urban Emergency Department. AIDS Res Treat. 2011;2011:879065. doi: 10.1155/2011/879065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Minniear TD. Gilmore B. Arnold SR. Flynn PM. Knapp KM. Gaur AH. Implementation of and barriers to routine HIV screening for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1076–1084. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Merchant RC. Seage GR. Mayer KH. Clark MA. DeGruttola VG. Becker BM. Emergency department patient acceptance of opt-in, universal, rapid HIV screening. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:27–40. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Christopoulos KA. Weiser SD. Koester KA, et al. Understanding patient acceptance and refusal of HIV testing in the emergency department. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lyons MS. Lindsell CJ. Wayne DB, et al. Comparison of missed opportunities for earlier HIV diagnosis in 3 geographically proximate emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:S17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.018. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fernandez MI. Perrino T. Royal S. Ghany D. Bowen GS. To test or not to test: Are Hispanic men at highest risk for HIV getting tested? AIDS Care. 2002;14:375–384. doi: 10.1080/09540120220123757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fichtner RR WR. Johnson WD. Rabins CB. Fishbein M. Influence of perceived and assessed risk on STD clinic clients' acceptance of HIV testing, return for test results and HIV serostatus. Psychol Health Med. 1996;1:83–98. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bond L. Lauby J. Batson H. HIV testing and the role of individual- and structural-level barriers and facilitators. AIDS Care. 2005;17:125–140. doi: 10.1080/09541020512331325653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Adams AL. Becker TM. Lapidus JA. Modesitt SK. Lehman JS. Loveless MO. HIV infection risk, behaviors, and attitudes about testing: Are perceptions changing? Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:764–768. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000078824.33076.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Merchant RC. Clark MA. Langan TJt. Mayer KH. Seage GR., 3rd DeGruttola VG. Can computer-based feedback improve emergency department patient uptake of rapid HIV screening? Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:S114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.035. e1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]