Abstract

Objectives

To describe the duration of bipolar I major and minor depressive episodes and factors associated with time to recovery.

Method

219 participants with bipolar I disorder based on Research Diagnostic Criteria analogs to DSM-IV-TR criteria were recruited from 1978–1981 and followed for up to 25 years. Psychopathology was assessed with the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation. The probability of recovery over time from multiple successive depressive episodes was examined with survival analytic techniques, including mixed-effects grouped-time survival models.

Results

The median duration of major depressive episodes was 14 weeks, and over 70% recovered within 12 months of onset of the episode. The median duration of minor depressive episodes was 8 weeks, and approximately 90% recovered within 6 months of onset of the episode. Aggregated data demonstrated similar durations of the first three major depressive episodes. However, for each participant with multiple episodes of major depression or minor depression, the duration of each episode was not consistent (intraclass correlation coefficient=0.07 and 0.25 for major and minor depression, respectively). The total number of years in episode over follow-up with major plus minor depression prior to onset of a major depressive episode was significantly associated with a decreased probability of recovery from that episode; with each additional year, the likelihood of recovery was reduced by 7% (hazard ratio: 0.93, 95% CI: 0.89–0.98, p=0.002).

Conclusions

Bipolar I major depression generally lasts longer than minor depression, and the duration of multiple episodes within an individual varies. However, the probability of recovery over time from an episode of major depression appears to decline with each successive episode.

Introduction

Depression occurs more often in bipolar I disorder than manic and mixed states.1–3 Bipolar I depressive states are associated with poor short-term4 and long-term symptomatic outcome,5 psychosocial functioning is significantly worse during periods of depression than mania or hypomania,6–10 and suicidality is greatest during depressive and mixed states.8,11–14 Despite these implications, few reports have described the duration of depressive episodes.

The National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Depression Study (CDS) is the only long-term observational study to have previously examined the duration of depressive episodes in bipolar I.15 An early report from this study examined 66 participants with bipolar I followed for up to 5 years, and found that the median time to recovery from the first two prospectively observed episodes of major depression was 20 weeks and 24 weeks.16 A subsequent report described 82 participants with bipolar I followed for 10 years; the median duration of major and minor depressive episodes were 12 and 5 weeks, respectively.17 These results are limited by the relatively short duration of follow-up, which is problematic as bipolar I disorder has a mean age of onset of 18 years,18 and the risk of suffering recurrent mood episodes remains high for at least 40 years after onset.19 These two reports also lacked the analytic methods required to study the effect of successive mood episodes given correlated observations.20

We sought to utilize longer term data from the CDS to describe recovery from episodes of bipolar I major and minor depression. Using a mixed-effects grouped-time survival model, we analyzed the effect of multiple depressive episodes upon episode duration, and examined factors associated with time to recovery. The model also facilitated determination of within-subject variability in time to recovery across depressive episodes.

Methods

Subjects

From 1978 to 1981, the CDS recruited patients with active mood disorders at academic medical centers in Boston, Chicago, Iowa City, New York, or St. Louis. Inclusion criteria included age of at least 17 years, IQ greater than 70, ability to speak English, white race (genetic hypotheses), knowledge of biological parents, and no evidence the mood disorder was secondary to a medical condition. The study was approved by each respective institutional review board, and participants provided written informed consent.

A total of 955 patients entered the study, all of whom met Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC)21 for a major mood episode. The sample for the present analysis consists of the 219 subjects who 1) met RDC for either bipolar I disorder or schizoaffective disorder, mainly affective subtype, 2) recovered from the mood episode present at study intake, and 3) subsequently suffered at least one depressive episode. Of the 269 subjects who met diagnostic criterion 1 above, 4 were lost to follow-up before the six month assessment, 46 did not suffer a recurrence of major depression, and 219 recovered from the intake mood episode and suffered at least one subsequent depressive episode. The 46 subjects with at least one follow-up who did not suffer a repeat depressive episode following recovery were followed for a mean (SD) of 10.7 (9.4) years, and compared with the 219 subjects, experienced a non-significantly greater persistence of clinically significant depressive symptoms as defined by previous methods22–28 (median of 35% vs. 14% of follow-up, Wilcoxon Rank Sum p=0.07), though otherwise did not differ from the sample on sociodemographic or clinical variables. RDC21 criteria for bipolar I disorder fall within DSM-IV-TR criteria.20 RDC21 for schizoaffective disorder, mainly affective subtype, are very similar to the DSM-IV-TR20 criteria for bipolar I disorder, demanding relevant psychotic symptoms develop simultaneously with or following manic or depressive symptoms and are not present for a week or more in the absence of manic or depressive symptomatology. Previous analyses further show similar course of illness.29 The inclusion of subjects with the predominantly affective subtype of schizoaffective disorder isconsistent with other longitudinal studies of bipolar I disorder.19,26,27,29–32

Of the 219 subjects, 156 (71%) were diagnosed with bipolar I disorder at study intake, 25 (11%) were diagnosed with unipolar major depressive disorder at intake but subsequently suffered at least one episode of mania over follow-up, 14 (6%) were diagnosed with bipolar II disorder at intake but subsequently suffered an episode of mania, and 24 (11%) were diagnosed at study intake with schizoaffective disorder, mainly affective subtype. Compared with the other subjects, those with unipolar major depressive disorder on intake experienced a greater persistence of clinically significant depressive symptoms as defined by previous methods22–28 (median of 33% vs. 11% of follow-up, Wilcoxon Rank Sum p=0.001), though otherwise did not differ from the remaining sample on sociodemographic or clinical variables. Subjects with bipolar II disorder or schizoaffective disorder, mainly affective subtype did not differ from other subjects on any of the sociodemographic or clinical variables.

Assessments and Procedures

At intake, raters interviewed patients about their current and past psychiatric history using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia.33 Raters also reviewed medical records, and whenever feasible, interviewed physicians and other informants.

Over prospective follow-up, raters assessed the level of psychopathology through direct interviews conducted every six months for the first five years of the study and annually thereafter, using variations of the semi-structured Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE).34 In the current study, participants were prospectively followed for up to 25 years. At each assessment, the interviewer rated the weekly level of psychopathology for each mood syndrome that occurred since the time of the last interview, and assigned a separate weekly score for each mood syndrome. To accomplish this, the rater utilized chronological anchor points to aid recollection and whenever possible obtained corroborative data from medical records. Level of psychopathology for major depression was quantified on a 6-point scale. A rating of 1 corresponded to no symptoms while 6 indicated full criteria for the disorder along with psychosis or extreme impairment in functioning. For minor depression, psychopathology was quantified on a 3-point scale.

Minor depression was defined as at least two weeks of depressed mood accompanied by at least two other symptoms, without psychosis or the threshold of major depression. Minor depression included episodes identified within the RDC35 nosology as lasting “for less than 2 years,” or “for 2 or more years” (analogous to the DSM-IV-TR construct of “dysthymia”).20 If at any point during a minor depressive episode, the participant met criteria for major depression, the entire episode was considered major depression.

Recovery from episodes of major or minor depression was defined according to RDC,20 which require ≥8 consecutive weeks with either no symptoms or only 1–2 mild symptoms with no functional impairment. A major depressive episode may thus include periods of minor depression and euthymia shorter than eight weeks. Recurrence or onset of a new depressive episode was defined as the reappearance of major depression at full criteria for at least two consecutive weeks or minor depression at the definite level for at least two consecutive weeks. By definition, recurrence occurred only after recovery from the preceding episode.

Raters received rigorous training before\certified to conduct interviews and subsequently the inter-rater reliability of the LIFE was excellent, with high intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for rating changes in symptoms (ICC=0.92), recovery from mood episodes (ICC=0.95), and reappearance of symptoms (ICC=0.88).34 Additionally, the test-retest reliability of the LIFE was very good, with ICC’s ranging from 0.85 to 0.93.36

Treatment

The CDS was an observational study in that treatment was not assigned. Over time, the intensity of treatment varied both within subjects and between subjects. The type and dose of all prescribed somatic treatment was collected with the LIFE34 and corroborated with available medical records.

Data Analytic Procedures – Time to Recovery

The Kaplan-Meier product-limit37 estimated the cumulative probability of recovery over time from each of the first three, prospectively observed, major depressive episodes per subject. The intake depressive episode was excluded from these analyses because it was previously described,38 and was not entirely prospective. Survival time was defined as the number of weeks until recovery from the depressive episode, and began with the first week of each depressive episode. Survival analyses estimated the cumulative probability of recovery and survival time ended with recovery from the episode, or for censored cases, end of the follow-up period (25 years), withdrawal from study, or death.

Data Analytic Procedures – Factors Associated with Recovery

A mixed-effects grouped-time survival model39 estimated the magnitude of the association between various clinical predictors and the probability of recovery over time from episodes of bipolar I major depression. The predictors included:

Severe episode onset: full criteria for major depression along with psychosis or extreme impairment in functioning in week one of the episode

Number of prior depressive episodes: number of major and minor depressive episodes observed during prospective follow-up, beginning with the intake mood episode and ending with the depressive episode immediately prior

Number of years in episode with depression: cumulative number of years in episode (symptomatically ill) with major depression plus minor depression during prospective follow-up, beginning at study intake and ending with the week prior to onset of the referent episode

Comorbid anxiety disorder: generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, phobic disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder.

A second mixed-effects grouped-time survival model39 estimated the magnitude of any association between various predictors and recovery from bipolar I minor depression over time. The predictors included: number of prior depressive episodes, number of years ill with depression, and comorbid anxiety disorder. The mixed models also calculated an ICC, which estimated the consistency in duration of depressive episodes across multiple within-subject episodes.

The mixed-effects models accounted for the correlation among multiple, within-subject depressive episodes. In the grouped-time survival model for recovery from major depression, the episode durations were categorized as follows (in weeks): 1–4, 5–8, 9–13, 14–17, 18–21, 22–26, 27–52, and > 52. For minor depression, the episode durations were categorized as follows (in weeks): 1–4, 5–8, 9–13, 14–26, and > 26. The choice of survival time intervals was guided by clinical relevance while avoiding sparse cells. It was assumed that the hazard was constant within any categorized time interval. Each statistical test used a two-tailed alpha=0.05.

Results

Subjects and Length of Follow-Up

The sample consisted of 219 subjects with bipolar I disorder who each recovered from the study-intake mood episode and then suffered at least one depressive episode. The mean (median; SD) length of follow-up was 17.3 (20; 7.9) years. Of the 219 subjects, 169 (77%) were followed for at least 10 years and 122 (56%) were followed for at least 20 years. Those with ≥20 years of follow-up tended to be younger at intake (p=0.001) though did not otherwise differ. Data for the 39 (18%) who died during follow-up are included. Table 1 displays the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics at study intake.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics at Study Intake for Subjects with Bipolar I Disorder N = 219

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 37 (13) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| male | 97 (44) |

| female | 122 (56) |

| Marital Status, n (%) | |

| never married | 84 (38) |

| married/live together | 85 (39) |

| divorced, separated, or widowed | 50 (23) |

| Socioeconomic Status, n (%)a, b | |

| I | 8 (4) |

| II | 32 (15) |

| III | 69 (32) |

| IV | 63 (29) |

| V | 47 (21) |

| Intake Medical Center, n (%) | |

| Boston | 34 (16) |

| Chicago | 43 (20) |

| Iowa City | 62 (28) |

| New York | 31 (14) |

| St. Louis | 49 (22) |

| Status at Intake, n, (%) | |

| inpatient | 196 (89) |

| outpatient | 23 (11) |

| Polarity of Mood State at Study Intake, n (%) | |

| mania | 142 (65) |

| major depression | 62 (28) |

| mixed | 15 (7) |

| Psychosis, n (%) | |

| present | 121 (55) |

| absent | 98 (45) |

| Global Assessment Scale score, mean (SD)c | 32 (11) |

| Age of Onset for First Lifetime Mood Episode (major depression, minor depression, mania or hypomania), years, mean (SD) | 24 (10) |

| Number of Mood Episodes Prior to Intake Episode, n (%) | |

| 0 | 27 (12) |

| 1 | 20 (9) |

| 2 | 26 (12) |

| 3 or more | 146 (67) |

Time to Recovery – Bipolar I Major Depression

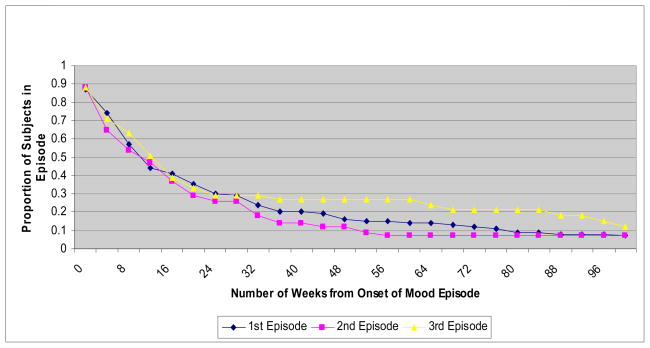

A total of 373 major depressive episodes were prospectively observed during the 25-year follow-up. Table 2 displays the proportion of subjects who recovered over time from each of the first three episodes of major depression. These first three episodes comprised 262 (70%) of the 373 major depressive episodes. There were 130 subjects who suffered at least one prospectively observed major depressive episode. Based upon Kaplan-Meier estimates, 84% recovered from this first episode within one year of onset of the episode. Of the 80 subjects with a second major depressive episode, 88% recovered within one year. Among subjects with a third episode, 73% recovered within one year. The corresponding Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the duration of the first three major depressive episodes are shown in Figure 1. The three curves are similar, indicating that time to recovery in the sample as a whole was consistent across multiple episodes.

Table 2.

Proportion of Subjects Recovering from Successive Prospectively Observed Episodes of Bipolar I Major Depressiona

| Time from Onset of Mood Episodeb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mood Episode Number | Number of Subjects at Start of Mood Episode | 1 month | 3 months | 6 months | 1 year | 2 years | 5 years |

| 1 | 130 | 0.130 (0.045–0.345) | 0.460 (0.287–0.674) | 0.670 (0.486–0.842) | 0.840 (0.668–0.952) | 0.930 (0.784–0.990) | c |

| 2 | 80 | 0.120 (0.028–0.433) | 0.480 (0.265–0.750) | 0.720 (0.485–0.913) | 0.880 (0.664–0.984) | c | c |

| 3 | 52 | 0.120 (0.021–0.534) | 0.370 (0.149–0.733) | 0.710 (0.425–0.937) | 0.730 (0.439–0.949) | c | c |

Recovery from an episode of major depression was defined according to Research Diagnostic Criteria (Spitzer et al., 1978), which require at least eight consecutive weeks with either no symptoms or only one or two symptoms at a mild level of severity, and no impairment of functioning.

Proportions derived from Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimates (95% confidence interval).

Estimate was not calculated because of limited number of subjects at risk for recovery.

Figure 1.

Time to Recovery from the First Three Major Depressive Episodes

The quartiles for duration of the first three prospectively observed major depressive episodes were also analyzed. Across all three episodes, 25% of the subjects (i.e., the first quartile) recovered within 6.0 (SE=0.8) weeks of onset of the episode, 50% of the subjects recovered within 14.0 (SE=1.4) weeks, and 75% recovered within 35.0 (SE=3.4) weeks.

Factors Associated with Recovery from Bipolar I Major Depression over Time

In mixed-effects grouped-time survival analysis, a greater number of years in episode (symptomatically ill) with major depression plus minor depression during prospective follow-up was associated with a significantly decreased probability of recovery. With each additional year in episode prior to onset of a major depressive episode, the likelihood of recovery from that episode was reduced by approximately 7% (hazard ratio: 0.93, 95% CI: 0.89–0.98, Z=−3.08, p=0.002), controlling for number of prior depressive episodes, severe onset of episode, and comorbid anxiety. Number of prior depressive episodes (hazard ratio: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.94–1.04, Z=−0.50, p=0.62), severe onset of episode (hazard ratio: 1.08, 95% CI: 0.65–1.77, Z=0.28, p=0.78), and comorbid anxiety disorder (hazard ratio: 1.01, 95% CI: 0.64–1.62, Z=0.05, p=0.96) were not significantly associated with the probability of recovery from an episode of major depression.

The mixed-effects model also examined within-subject variability in time to recovery. The model yielded an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.07, meaning that for each subject with two or more prospectively observed episodes of major depression, the duration of these multiple episodes was not consistent.

Time to Recovery – Bipolar I Minor Depression

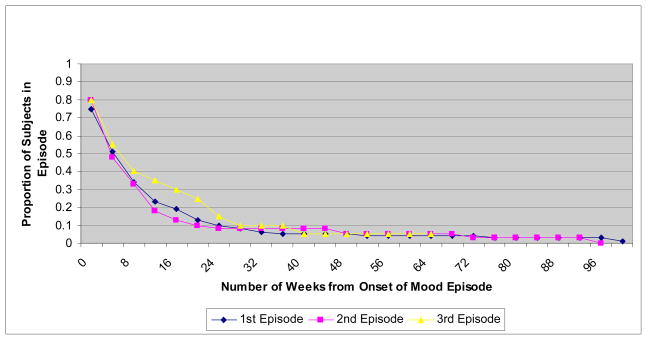

A total of 157 bipolar I minor depressive episodes were prospectively observed during the 25-year follow-up. Table 3 displays the proportion of subjects who recovered over time from each of the first three episodes of minor depression. These first three episodes comprised 140 (89%) of the 157 minor depressive episodes. There were 80 subjects who suffered at least one prospectively observed minor depressive episode. Based upon Kaplan-Meier estimates, 70% recovered from this first episode within three months of onset of the episode. Of the 40 subjects with a second minor depressive episode, 70% recovered from that episode within three months of onset. Among subjects with a third minor depressive episode, 60% recovered within three months.

Table 3.

Proportion of Subjects Recovering from Successive Prospectively Observed Episodes of Bipolar I Minor Depressiona

| Time from Onset of Mood Episode b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mood Episode Number | Number of Subjects at Start of Mood Episode | 1 month | 3 months | 6 months | 1 year |

| 1 | 80 | 0.250 (0.099–0.550) | 0.700 (0.471–0.898) | 0.890 (0.687–0.985) | c |

| 2 | 40 | 0.200 (0.044–0.668) | 0.700 (0.385–0.949) | 0.920 (0.608–0.999) | c |

| 3 | 20 | 0.200 (0.023–0.882) | 0.600 (0.212–0.971) | c | c |

Recovery from an episode of minor depression was defined according to Research Diagnostic Criteria (Spitzer et al., 1978), which require at least eight consecutive weeks with either no symptoms or only one or two symptoms at a mild level of severity, and no impairment of functioning.

Proportions derived from Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimates (95% confidence interval).

Estimate was not calculated because of limited number of subjects at risk for recovery.

The corresponding Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the duration of the first three minor depressive episodes are shown in Figure 2. The three curves are again similar, suggesting consistency in aggregate time to recovery across multiple mood episodes.

Figure 2.

Time to Recovery from the First three Minor Depressve Episodes

The quartiles for duration of the first three prospectively observed bipolar I minor depressive episodes were also analyzed. Overall, across all three episodes, 25% of the subjects (the first quartile) recovered within 4.0 (SE=0.4) weeks of onset of the episode, 50% of the subjects (the median) recovered within 8.0 (SE=0.9) weeks of onset of the episode, and 75% (the third quartile) recovered within 15 (SE=1.9) weeks.

Factors Associated with Recovery from Bipolar I Minor Depression over Time

With mixed-effects grouped-time survival analysis, the number of years of episodic depression (hazard ratio: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.86–1.02, Z=−1.54, p=0.12), number of prior depressive episodes (hazard ratio: 1.09, 95% CI: 0.98–1.22, Z=1.63, p=0.10), and comorbid anxiety disorder (hazard ratio: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.18–1.91, Z=−0.88, p=0.38) were not significantly associated with the probability of recovery from an episode of minor depression.

The mixed-effects model also examined within-subject variability in time to recovery from one minor depressive episode to the next. The model yielded an ICC of 0.25.

Treatment

Treatment was categorically defined as at least eight consecutive weeks of somatic therapy or treatment for the entire episode in the case of episodes lasting fewer than eight weeks. Over one-half of the depressive episodes were treated with a mood stabilizer, and roughly one-quarter of the depressive episodes were treated with a mood stabilizer plus an antidepressant. Nearly one-quarter of the bipolar I major depressive episodes were treated with an antidepressant in the absence of a mood stabilizer.

Discussion

In a large prospective cohort with bipolar I disorder over long-term follow-up, the median duration of major depression was 14 weeks and minor depression was 8 weeks. Within episodes, the rate of recovery decreases over time, underscoring the significance of persistent depressive episodes. Across episodes, the cumulative duration of previous depressive episodes was associated with a significantly decreased probability of recovery from a new episode of major depression, such that with each additional year of depressive illness prior to onset of a major depressive episode, the likelihood of recovery from that episode was reduced by approximately 7% (consistent with a previous finding).38 For any single patient with multiple episodes of major and minor depression, the duration of the episodes was inconsistent although those with a more chronic course had delayed recovery as noted above.

Only a few observational studies such as the CDS have prospectively collected data on samples of this size over decades to describe recovery from multiple mood episodes of bipolar I disorder. The length of follow-up allowed the investigators to analyze 402 depressive episodes, and to better assess subjects with relatively long mood episodes and subjects with a long interval of wellness between mood episodes. This reduced the likelihood that length of follow-up would condition or bias the results. Other strengths of the present study included frequent assessment of subjects through direct interviews using standardized diagnostic and follow-up instruments. In addition, the study met the need for evaluating course of illness in patients treated in the community rather than specialty mood disorder clinics.8

For the entire sample of subjects analyzed collectively, time to recovery from the three prospectively observed episodes of bipolar I major depression was similar (see Figure 1 and Table 2). Likewise, recovery from the three prospectively observed episodes of minor depression was uniform (see Figure 2 and Table 3). This consistency across multiple depressive episodes in bipolar I disorder is strikingly similar to the uniformity in time to recovery across multiple depressive episodes in unipolar major depressive disorder.40,41

However, the regularity in recovery across multiple episodes that was observed when the data were analyzed collectively for the entire sample was not observed at the level of individual subjects. For each participant with two or more prospectively observed episodes of major depression, the duration of these multiple episodes was highly inconsistent. Similarly, for each subject with two or more prospectively observed episodes of minor depression, the duration of these multiple episodes was inconsistent. These findings are at odds with the idea that the duration of episodes is relatively constant in a given individual8 and in contrast to prior findings of long-term stability in consistency of overall symptom burden or persistence,42 suggesting perhaps that chronicity of illness but not episode duration may be stable. In this analysis, those with a more chronic course of illness over prospective follow-up were less likely to recover from major depressive episodes.

There are several limitations to this study. A majority of participants were inpatients at academic medical centers at the time of enrollment into the study although participants spent a significant amount of time as outpatients and hospitalization is relatively common in patients with bipolar disorder.43 The recruitment location may have selected for higher acuity than a representative community sample. While our use of prospectively observed episodes minimized recall bias related to any estimation of the duration of intake episode, almost one fifth of those with bipolar I did not have a recurrence following a remission. Our results may not generalize to this subset of individuals with a chronic course that does not remit. Our results related to duration of depressive episodes in bipolar I are further presented in aggregate form and it is not clear the extent to which this overlaps with specific subgroups. Another limitation is that subjects were recruited at varying points in their course of illness, with some subjects enrolled closer to onset of their illness. The mixed-effects model thus systematically and differentially underestimated the number of years in episode with depression, because the analyses did not capture depressive illness prior to intake. Treatment was not controlled and may not have been optimal. The analyses were not designed to appropriately assess treatment effects akin to prior analyses of these observational data.44,45 This prior work highlighted the importance of clinical variables such as the nature, severity, and trajectory of mood symptoms,44–46 which if not adequately addressed, could yield misleading results. Future study of treatment will use models with treatment intervals, rather than mood episodes, as the unit of analysis, and use propensity scores to address confounding factors that determine treatment selection.

Additional questions remain regarding duration of bipolar I mania, hypomania, and cycling and mixed episodes. Further analyses of the CDS data will improve our knowledge of the prognosis for bipolar I disorder.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by NIMH grant MH25478-29A2. The NIMH had no further role in the design or conduct of this study; in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

This study was funded by NIMH grants 5R01MH025416-33 (W Coryell), 5R01MH023864-35 (J Endicott), 5R01MH025478-33 (M Keller), 5R01MH025430-33 (J Rice), and 5R01MH029957-30 (WA Scheftner). Dr. Solomon serves as Deputy Editor at UpToDate.com. In the past 36 months, Dr. Endicott has received research support from the New York State Office of Mental Hygiene, the US National Institute of Mental Health and Cyberonics. She has served as a consultant or advisory board member to Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer Heathcare, Berlex, Shire and Wyeth-Ayerst. In the past 36 months, Dr. Keller has received research support from Pfizer. He has served as a consultant or received honoraria from CENEREX, Medtronic, and Sierra Neuropharmceuticals and served on an advisory board for CENEREX.

Conducted with the current participation of the following investigators: M.B. Keller, M.D. (Chairperson, Providence, RI); W. Coryell, M.D. (Co-Chairperson, Iowa City, IA); D.A. Solomon, M.D. (Providence, RI); W. Scheftner, M.D. (Chicago, IL); J. Endicott, Ph.D., A.C. Leon, Ph.D., and J. Loth, M.S.W. (New York, NY); and J. Rice, Ph.D., (St. Louis, MO). Other current contributors include H.S. Akiskal, M.D., J. Fawcett, M.D., L.L. Judd, M.D., P.W. Lavori, Ph.D., J.D. Maser, Ph.D., and T. I. Mueller, M.D.

Footnotes

deceased

Clinical Points

The median duration of major and minor depressive episodes in bipolar I disorder are 14.0 and 8.0 weeks, respectively.

A more chronic course of illness is associated with a delayed recovery from depressive episodes in bipolar I disorder, although duration of discrete episodes is variable within individuals.

Disclosures:

All other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

This manuscript has been reviewed by the Publication Committee of the Collaborative Depression Study and has its endorsement. The data for this manuscript came from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Collaborative Program on the Psychobiology of Depression - Clinical Studies. The Collaborative Program was initiated in 1975 to investigate nosologic, genetic, family, prognostic, and psychosocial issues of mood disorders, and is an ongoing, long-term multidisciplinary investigation of the course of mood and related affective disorders. The original principal and co-principal investigators were from five academic centers and included Gerald Klerman, M.D.* (Co-Chairperson), Martin Keller, M.D., Robert Shapiro, M.D.* (Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School), Eli Robbins, M.D.*, Paula Clayton, M.D., Theodore Reich, M.D.,* Amos Wellner, M.D.,* (Washington University Medical School), Jean Endicott, Ph.D., Robert Spitzer, M.D., (Columbia University), Nancy Andreasen, M.D., Ph.D., William Coryell, M.D., George Winokur, M.D.* (University of Iowa), Jan Fawcett, M.D., William Scheftner, M.D., (Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center). The NIMH Clinical Research Branch was an active collaborator in the origin and development of the Collaborative Program with Martin M. Katz, Ph.D., Branch Chief as the Co-Chairperson and Robert Hirschfeld, M.D. as the Program Coordinator. Other past collaborators include J. Croughan, M.D., M.T. Shea, Ph.D., R. Gibbons, Ph.D., M.A. Young, Ph.D., D.C. Clark, Ph.D.

References

- 1.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(6):530–537. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kupka RW, Altshuler LL, Nolen WA, et al. Three times more days depressed than manic or hypomanic in both bipolar I and bipolar II disorder. Bipolar disorders. 2007;9(5):531–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) The American journal of psychiatry. 2006;163(2):217–224. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mysels DJ, Endicott J, Nee J, et al. The association between course of illness and subsequent morbidity in bipolar I disorder. Journal of psychiatric research. 2007;41(1–2):80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coryell W, Turvey C, Endicott J, et al. Bipolar I affective disorder: predictors of outcome after 15 years. Journal of affective disorders. 1998;50(2–3):109–116. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer MS, Kirk GF, Gavin C, Williford WO. Determinants of functional outcome and healthcare costs in bipolar disorder: a high-intensity follow-up study. Journal of affective disorders. 2001;65(3):231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calabrese JR, Hirschfeld RM, Frye MA, Reed ML. Impact of depressive symptoms compared with manic symptoms in bipolar disorder: results of a U.S. community-based sample. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2004;65(11):1499–1504. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-Depressive Illness: Bipolar Disorders and Recurrent Depression. 2. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 120pp. 128pp. 263–264.pp. 340 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. Psychosocial disability in the course of bipolar I and II disorders: a prospective, comparative, longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(12):1322–1330. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon GE, Bauer MS, Ludman EJ, Operskalski BH, Unutzer J. Mood symptoms, functional impairment, and disability in people with bipolar disorder: specific effects of mania and depression. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2007;68(8):1237–1245. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dilsaver SC, Chen YW, Swann AC, Shoaib AM, Tsai-Dilsaver Y, Krajewski KJ. Suicidality, panic disorder and psychosis in bipolar depression, depressive-mania and pure-mania. Psychiatry research. 1997;73(1–2):47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawton K, Sutton L, Haw C, Sinclair J, Harriss L. Suicide and attempted suicide in bipolar disorder: a systematic review of risk factors. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2005;66(6):693–704. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isometsa ET, Henriksson MM, Aro HM, Lonnqvist JK. Suicide in bipolar disorder in Finland. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(7):1020–1024. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valtonen HM, Suominen K, Haukka J, et al. Differences in incidence of suicide attempts during phases of bipolar I and II disorders. Bipolar disorders. 2008;10(5):588–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz MM, Secunda SK, Hirschfeld RM, Koslow SH. NIMH clinical research branch collaborative program on the psychobiology of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36(7):765–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780070043004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coryell W, Keller M, Endicott J, Andreasen N, Clayton P, Hirschfeld R. Bipolar II illness: course and outcome over a five-year period. Psychol Med. 1989;19(1):129–141. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700011090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The comparative clinical phenotype and long term longitudinal episode course of bipolar I and II: a clinical spectrum or distinct disorders? J Affect Disord. 2003;73(1–2):19–32. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angst J, Gamma A, Sellaro R, Lavori PW, Zhang H. Recurrence of bipolar disorders and major depression. A life-long perspective. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience. 2003;253(5):236–240. doi: 10.1007/s00406-003-0437-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E. Research diagnostic criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35(6):773–782. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300115013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coryell W, Fiedorowicz J, Leon AC, Endicott J, Keller MB. Age of onset and the prospectively observed course of illness in bipolar disorder. Journal of affective disorders. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiedorowicz JG, Endicott J, Solomon DA, Keller MB, Coryell WH. Course of illness following prospectively observed mania or hypomania in individuals presenting with unipolar depression. Bipolar disorders. 2012;14(6):664–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiedorowicz JG, Coryell WH, Rice JP, Warren LL, Haynes WG. Vasculopathy related to manic/hypomanic symptom burden and first-generation antipsychotics in a sub-sample from the collaborative depression study. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics. 2012;81(4):235–243. doi: 10.1159/000334779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiedorowicz JG, Palagummi NM, Behrendtsen O, Coryell WH. Cholesterol and affective morbidity. Psychiatry research. 2010;175(1–2):78–81. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fiedorowicz JG, Solomon DA, Endicott J, et al. Manic/Hypomanic Symptom Burden and Cardiovascular Mortality in Bipolar Disorder. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(6):598–606. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181acee26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fiedorowicz JG, Leon AC, Keller MB, Solomon DA, Rice JP, Coryell WH. Do risk factors for suicidal behavior differ by affective disorder polarity? Psychol Med. 2009;39(5):763–771. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Persons JE, Coryell WH, Fiedorowicz JG. Cholesterol fractions, symptom burden, and suicide attempts in mood disorders. Psychiatry research. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solomon DA, Leon AC, Endicott J, et al. Empirical typology of bipolar I mood episodes. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(6):525–530. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.062083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nolen WA, Luckenbaugh DA, Altshuler LL, et al. Correlates of 1-year prospective outcome in bipolar disorder: results from the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network. The American journal of psychiatry. 2004;161(8):1447–1454. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sachs GS, Thase ME, Otto MW, et al. Rationale, design, and methods of the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD) Biological psychiatry. 2003;53(11):1028–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solomon DA, Leon AC, Coryell WH, et al. Longitudinal course of bipolar I disorder: duration of mood episodes. Archives of general psychiatry. 2010;67(4):339–347. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Endicott J, Spitzer RL. A diagnostic interview: the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia. Archives of general psychiatry. 1978;35(7):837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770310043002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, et al. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation. A comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44(6):540–548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Altshuler LL, Gitlin MJ, Mintz J, Leight KL, Frye MA. Subsyndromal depression is associated with functional impairment in patients with bipolar disorder. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2002;63(9):807–811. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warshaw MG, Keller MB, Stout RL. Reliability and validity of the longitudinal interval follow-up evaluation for assessing outcome of anxiety disorders. Journal of psychiatric research. 1994;28(6):531–545. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Statistical Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Coryell W, et al. Differential outcome of pure manic, mixed/cycling, and pure depressive episodes in patients with bipolar illness. Jama. 1986;255(22):3138–3142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hedeker D, Siddiqui O, Hu FB. Random-effects regression analysis of correlated grouped-time survival data. Stat Methods Med Res. 2000;9(2):161–179. doi: 10.1177/096228020000900206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coryell W, Akiskal HS, Leon AC, et al. The time course of nonchronic major depressive disorder. Uniformity across episodes and samples. National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Program on the Psychobiology of Depression--Clinical Studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(5):405–410. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950050065007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Recovery from major depression. A 10-year prospective follow-up across multiple episodes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(11):1001–1006. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230033005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coryell W, Fiedorowicz J, Solomon D, Endicott J. Age transitions in the course of bipolar I disorder. Psychological medicine. 2009;39(8):1247–1252. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peele PB, Xu Y, Kupfer DJ. Insurance expenditures on bipolar disorder: clinical and parity implications. The American journal of psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1286–1290. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leon AC, Solomon DA, Li C, et al. Antidepressants and risks of suicide and suicide attempts: a 27-year observational study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(5):580–586. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leon AC, Solomon DA, Li C, et al. Antiepileptic drugs for bipolar disorder and the risk of suicidal behavior: a 30-year observational study. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(3):285–291. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11060948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prabhakar M, Haynes WG, Coryell WH, et al. Factors associated with the prescribing of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with bipolar and related affective disorders. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31(8):806–812. doi: 10.1592/phco.31.8.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]