Abstract

Tropheryma whipplei endocarditis differs from classic Whipple disease, which primarily affects the gastrointestinal system. We diagnosed 28 cases of T. whipplei endocarditis in Marseille, France, and compared them with cases reported in the literature. Specimens were analyzed mostly by molecular and histologic techniques. Duke criteria were ineffective for diagnosis before heart valve analysis. The disease occurred in men 40–80 years of age, of whom 21 (75%) had arthralgia (75%); 9 (32%) had valvular disease and 11 (39%) had fever. Clinical manifestations were predominantly cardiologic. Treatment with doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine for at least 12 months was successful. The cases we diagnosed differed from those reported from Germany, in which arthralgias were less common and previous valve lesions more common. A strong geographic specificity for this disease is found mainly in eastern-central France, Switzerland, and Germany. T. whipplei endocarditis is an emerging clinical entity observed in middle-aged and older men with arthralgia.

Keywords: Whipple’s disease, Whipple disease, Tropheryma whipplei, endocarditis, arthralgia, bacteria

Whipple disease was first described in 1907 (1). This chronic infection is characterized by histologic indication of gastrointestinal involvement, determined by a positive periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) reaction in macrophages from a small bowel biopsy sample (2). It is caused by Tropheryma whipplei and encompasses asymptomatic carriage of the organism to a wide spectrum of clinical pathologic conditions, including acute and chronic infections (1,2).

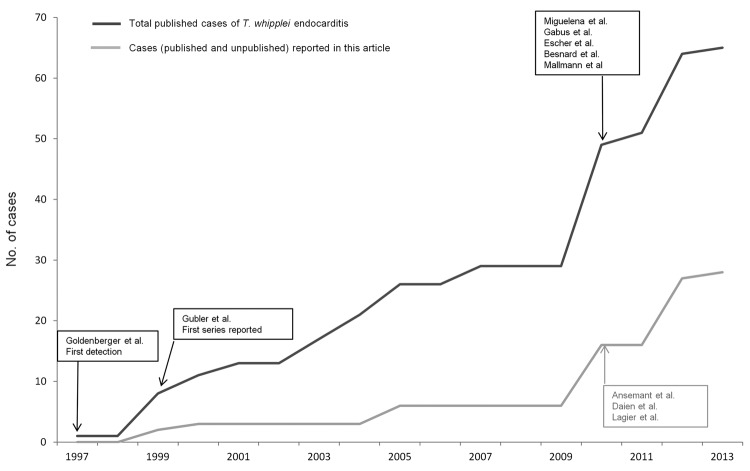

In 1997, T. whipplei was first implicated as an agent of blood culture–negative endocarditis in 1 patient by use of broad-range PCR amplification and direct sequencing of 16S rRNA applied to heart valves from patients in Switzerland (3). Two years later, 4 additional cases were reported in Switzerland (4). In 2000, the first strain of T. whipplei was obtained from the aortic valve of a patient with blood culture–negative endocarditis (5).

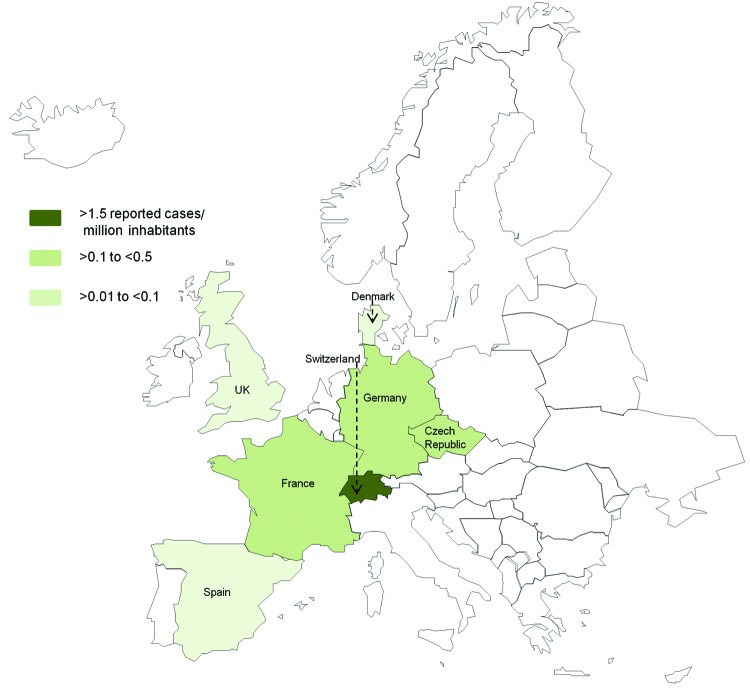

Blood culture–negative endocarditis accounts for 2.5%–31.0% of all cases of endocarditis. The incidence rate of T. whipplei endocarditis among blood culture–negative endocarditis cases has not been established; however, at our center (Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Marseille, Marseille, France), this incidence rate was estimated to be 2.6% (6). In Germany, the reported incidence rate for T. whipplei endocarditis is 6.3%: T. whipplei was the fourth most frequent pathogen found among 255 cases of endocarditis with an etiologic diagnosis and was the most common pathogen associated with blood culture–negative endocarditis. This incidence rate exceeds rates of infections caused by Bartonella Quintana; Coxiella burnetii; and members of the Haemophilus, Actinobacillus, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, Kingella spp. group (7). Smaller studies found incidence rates of 3.5% in Denmark (8), 4.3% in Switzerland (9), 7.1% in the Czech Republic (10), 2.8% in Spain (11), and none in Algeria (12). We describe 28 cases of T. whipplei endocarditis and compare them with cases reported in the literature.

Materials and Methods

Patient Recruitment and Case Definitions

Our center in Marseille, France, has become a referral center for patients with T. whipplei infections and blood culture–negative endocarditis (2,5,6). We receive samples from France and other countries. Each sample is accompanied by a questionnaire, completed by the physician, covering clinico-epidemiologic, biological, and therapeutic data for each patient. We analyzed data from October 2001 through April 2013. Diagnosis of T. whipplei endocarditis was confirmed by positive results from PAS staining and/or specific immunohistochemical analysis and 2 positive results from specific PCRs of a heart valve specimen in addition to lack of histologic lesions in small bowel biopsy samples or lack of clinical involvement of the gastrointestinal tract.

Laboratory Procedures

DNA was extracted from heart valves, 200 µL of body fluid (blood in a tube containing EDTA, saliva, or cerebrospinal fluid), small bowel biopsy samples, and ≈1 gram of feces by using QIAGEN columns (QIAamp DNA kit; QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed by using a LightCycler instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France) and the QuantiTect Probe PCR Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. From October 2001 through September 2003, all specimens were tested by qPCR selective for the 16S–23S rRNA intergenic spacer and the rpoB gene, as described (13); from October 2003 through March 2004, all specimens were tested by qPCR selective for T. whipplei repeated sequences (repeat PCR), as described (13). When an amplified product was detected, sequencing was systematically performed. Since April 2004, all specimens have been tested by a qPCR selective for T. whipplei repeated sequences, which used specific oligonucleotide Taqman probes for the identification (13). To validate the tests, we used positive and negative controls (13). For determination of DNA extract quality, the human actin gene was also detected. For positive specimens, T. whipplei genotyping was performed as described (14). In parallel, all heart valves and blood samples from patients with suspected endocarditis underwent systematic PCR screening for all bacteria (16S rRNA) and all fungi (18S rRNA) and underwent specific real-time PCR selective for Streptococcus oralis group, Streptococcus gallolyticus group, Enterococcus faecium and E. faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Mycoplasma spp., Coxiella burnetii, Bartonella spp., and T. whipplei as described (6).

For histologic analysis, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded heart valves and small bowel biopsy samples were cut in thin sections. Samples stained with hematoxylin-eosin-saffron and special stains were examined, and immunohistochemical investigations with a specific antibody were performed as reported (15). Cardiac valve and heparinized blood specimens were injected into cell and axenic cultures (5,16). Serologic assays were based on Western blot analyses (17).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using EpiInfo6 (www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/Epi6/EI6dnjp.htm). A p value <0.05 was considered significant. Data for the population of France were extracted from the National Institute for Statistics and Economical Studies website (www.insee.fr/fr/).

Literature Review

We searched the PubMed database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) through April 2013, using the keywords “Tropheryma,” “Whipple’s disease,” and “endocarditis.” We then performed a cross-reference analysis on the results of the search. For this literature review, the patient inclusion criteria were lack of histologic evidence of small bowel involvement or lack of diarrhea.

Results

Epidemiologic and Clinical Characteristics

Among the 28 patients for whom data enabled the diagnosis of T. whipplei endocarditis; 16 have been previously reported or cited (2,5,18,19). According to current modified Duke criteria (20) before the examination of heart valve specimens, only 1 (3.6%) patient met the criteria for endocarditis and 17 (60.7%) met the criteria for possible endocarditis (Technical Appendix Table 1)

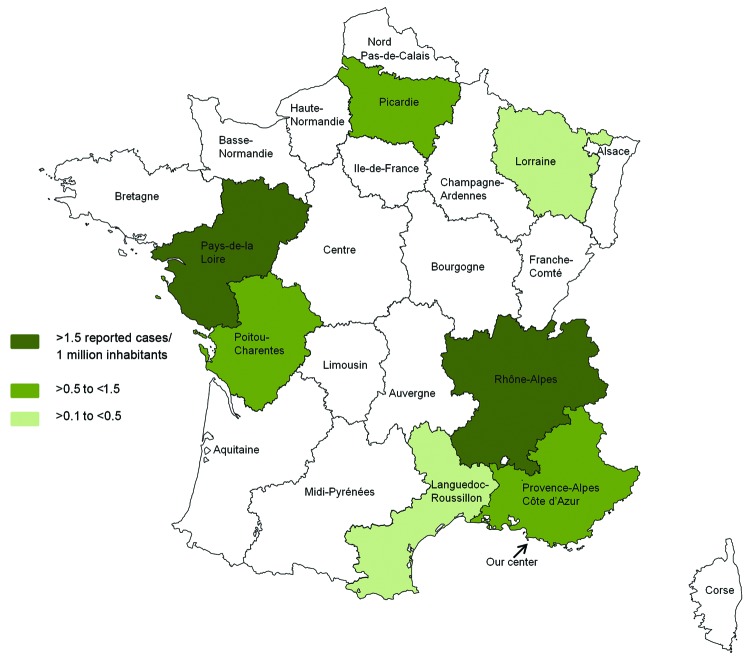

All 28 patients underwent heart valve replacement because of valve damage (21). All patients were male (Table 1), and mean age (± SD) was 58.6 (± 10) years (range 40–80 years). Among the 27 patients from France, 13 (48.1%) were living in the Rhône-Alpes area and 5 (18.5%) in the Pays de la Loire area. Although samples are sent from all over France, 66.6% of the patients were from only these 2 areas. If we focus on the 702 patients with blood culture–negative endocarditis in France referred to our center from May 2001 through September 2009 (Technical Appendix Table 2), the patients from these 2 areas were significantly more affected than the rest of the population (Rhône-Alpes 9/106 [8.5%] vs 7/596 [1.16%], p<0.001 and Pays de la Loire 4/26 [15.4%] vs 12/676; p<0.001) (6). Incidence rates of T. whipplei endocarditis in these 2 areas are also significantly higher than those in the rest of France (Rhône-Alpes 0.25 cases/1 million inhabitants/year, p<0.001; Pays de la Loire (0.15 cases/1 million inhabitants/year, p<0.001) (Figure 1).

Table 1. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of 28 patients with Tropheryma whipplei endocarditis*.

| Patient (reference) | Area of origin | Age, y | IS | Cardiac history | Arthralgia duration, y | Weight loss | Cardiac symptoms | Fever | Involved valves | Vegetation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PACA | 80 | N | PM | Y (15) | N | HF and AIS | N | AV | Y |

| 2 | Corsica† | 58 | N | N | Y (8) | N | HF | Y | AV+MV | N |

| 3 | Rhône-Alpes | 54 | N | N | Y (3) | Y | HF | Y | AV | Y |

| 4 | Rhône-Alpes | 45 | N | BAV | N | N | Stroke | Y | AV | Y |

| 5 | Rhône-Alpes | 56 | N | CS | N | N | HF | Y | AV | Y |

| 6 | PACA | 59 | Y | N | Y (35) | N | HF | N | AV | N |

| 7 | Pays de la Loire | 50 | N | N | Y (NA) | N | HF | N | AV+MV | Y |

| 8 | Picardie | 51 | N | N | N | N | Stroke | N | AV | Y |

| 9 | PACA | 79 | N | AVB | Y | N | HF | N | AV | Y |

| 10 | Lorraine | 50 | N | N | N | N | HF | N | MV | N |

| 11 | Rhône-Alpes | 62 | N | N | Y | N | HF | N | AV | Y |

| 12 | PACA | 58 | N | BAV | Y | Y | HF | Y | AV | Y |

| 13 (2) | Rhône-Alpes | 71 | N | N | N | N | HF | N | AV | Y |

| 14 (18) | Rhône-Alpes | 57 | Y | N | Y (4) | N | HF+PAE | Y | AV | N |

| 15 (2) | Poitou-Charentes | 68 | N | N | N | N | HF | Y | AV | Y |

| 16 (2) | Pays de la Loire | 48 | N | AVI | Y (NA) | N | HF | Y | AV | Y |

| 17 (19) | Languedoc-Roussillon | 70 | Y | N | Y (27) | N | HF | Y | AV | Y |

| 18 (2) | Pays de la Loire | 71 | N | MVI | Y (NA) | N | HF | Y | MV | Y |

| 19 (2) | Pays de la Loire | 57 | Y | N | Y (10) | Y | HF | Y | AV+MV | N |

| 20 (2) | Rhône-Alpes | 67 | N | N | Y (4) | N | Stroke | N | AV | N |

| 21 (2) | Rhône-Alpes | 51 | Y | N | Y (6) | N | PAE | N | AV+TV | Y |

| 22 (2) | Pays de la Loire | 58 | N | AAR | Y (NA) | N | PAE | N | AV | Y |

| 23 (2) | Rhône-Alpes | 60 | Y | N | Y (2) | N | HF | N | AV+MV | Y |

| 24 (2) | Rhône-Alpes | 61 | N | AAR | Y (4) | N | Stroke | N | AV+MV | Y |

| 25 (2) | Rhône-Alpes | 63 | N | N | Y (3) | N | PAE+stroke | N | AV | Y |

| 26 (5) | Canada | 42 | N | AAR | N | Y | HF | N | AV+MV | Y |

| 27 (2) | Rhône-Alpes | 40 | Y | AAR | Y (5) | N | HF | N | AV | Y |

| 28 (2) | Rhône-Alpes | 55 | N | N | Y (5) | Y | Stroke | N | MV | Y |

*All patients were male, and none had diarrhea. IS, immunosuppressive therapy; PACA, Provence-Alpes-Côte-d’Azur; N, no; PM, pacemaker; Y, yes; HF; heart failure; AIS, acute ischemic stroke; AV, aortic valve; MV, mitral valve; BAV, bicuspid aortic valve; CS, coronary stent; AVB, aortic valve bioprosthesis; AVI, aortic valve insufficiency; MVI, mitral valve insufficiency; NA, not available; PAE, peripheral arterial embolism; AAR, acute articular rheumatism. †This patient was from Poland but resided in Corsica for 8 years.

Figure 1.

Number of reported cases of Tropheryma whipplei endocarditis per 1 million inhabitants in each area of France over 10 years. Data from this series and the literature (22–24) were included. Among the metropolitan areas in France, the incidence of T. whipplei endocarditis is significantly more frequent in the Rhône-Alpes area than in 11 others areas (Alsace, Aquitaine, Basse-Normandie, Bourgogne, Centre, Champagne-Ardenne, Haute-Normandie, Ile de France, Languedoc-Roussillon, Midi-Pyrénées, and Nord Pas-de-Calais; p = 0.04, p = 0.004, p = 0.048, p = 0.04, p = 0.01, p = 0.04, p = 0.02, p<0.001, p = 0.04, p = 0.007, p = 0.006, respectively). The incidence rate is also significantly more frequent in the Pays de la Loire area than in 6 other areas (Aquitaine, Bretagne, Centre, Ile-de France, Lorraine, Midi-Pyrénées, Nord Pas de Calais; p = 0.04, p = 0.04, p = 0.04, p = 0.003, p = 0.03, p = 0.02, respectively).

Immunosuppressive therapy had been given to 7 (29%) patients, of which 3 received a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor. Arthralgia was reported for 21 (75%) patients; mean delay between arthralgia onset and endocarditis diagnosis was 8.5 years. Among 12 patients who had been interviewed by 1 of the authors (D.R.), arthralgia was detected in 11. Among these 12, arthralgia was retrospectively noticed by 1 patient who, after beginning treatment for endocarditis, reported the disappearance of slight pain that had been present for many years. Previous heart valve disease was known for 9 (32%) patients. Heart failure occurred in 20 (71.4%) patients, acute ischemic stroke in 7 (29.2%), and peripheral arterial embolism in 4 (16.6%). Fever was detected in 11 (39%) patients, and weight loss was experienced by 4 (14.3%). Echocardiography was performed for all 28 patients: transthoracic echocardiography for 4 patients, transesophageal echocardiography for 9 patients, both procedures for 7 patients, and unspecified procedures for 8 patients. Cardiac vegetations were found in 22 (78.6%) patients, and aortic valve involvement was found in 18 (64.2%).

Laboratory Findings

At the time of T. whipplei endocarditis diagnosis, increased C-reactive protein levels were detected in 17 (81%) of 21 patients, anemia in 6 (37.5%) of 16, and leukocytosis in 5 (29.5%) of 17. T. whipplei endocarditis was diagnosed by heart valve analysis (either PCR for T. whipplei or histologic analysis) for 27 of the 28 patients (Technical Appendix Table 3). Other molecular analyses were negative for other microorganisms on all heart valves and in blood samples (when available). Blood samples were positive for T. whipplei for 5 (31.2%) of 16 patients. For 1 patient (patient 12), at 4 days before heart valve replacement, a blood sample was positive for T. whipplei according to repeat PCR and negative according to 16S rRNA PCR. For another patient (patient 1), a pacemaker was positive for T. whipplei by PCR. T. whipplei was detected in 1 (6.7%) of 15 saliva samples, 2 (16.6%) of 12 fecal samples, and none of 8 cerebrospinal fluid samples.

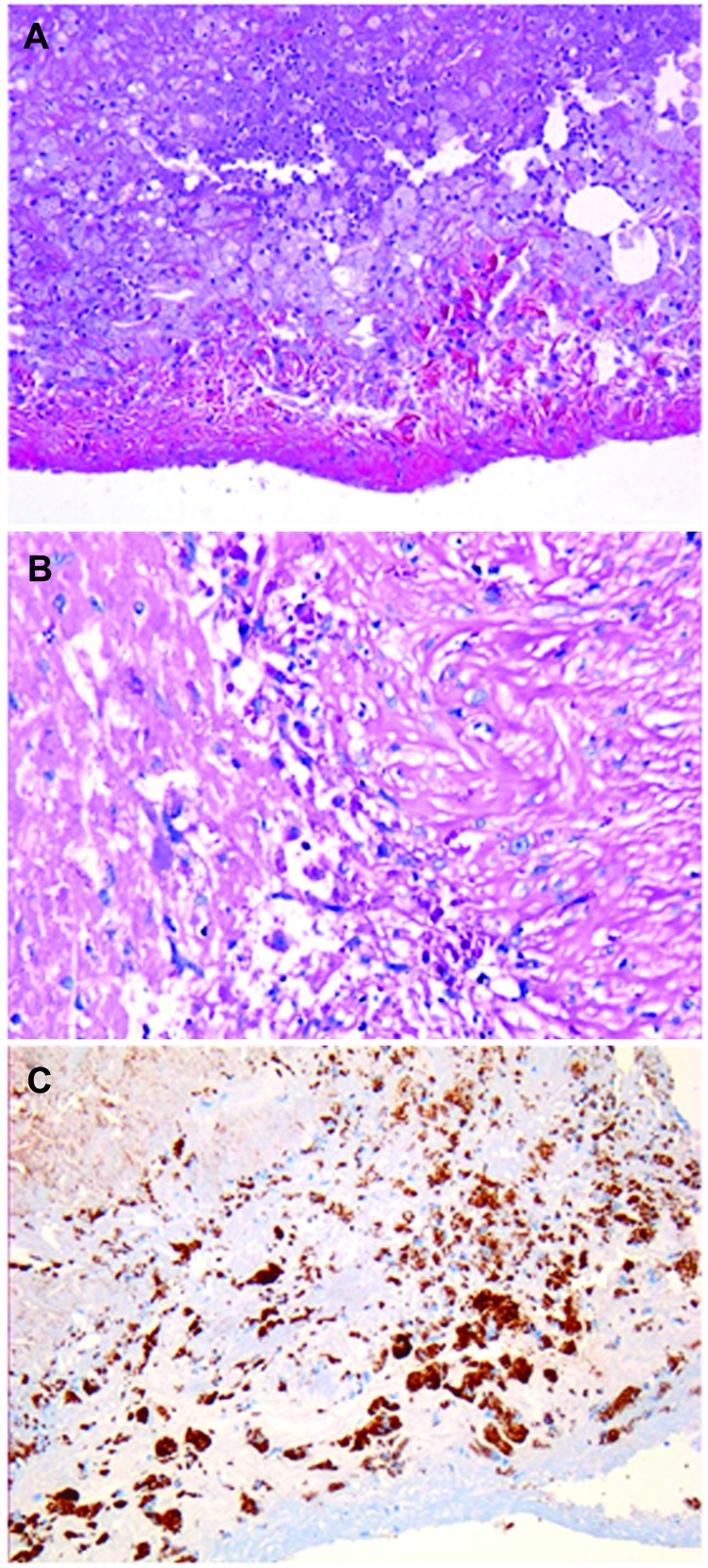

T. whipplei–infected heart valves show the typical histologic features of infective endocarditis: vegetations, inflammatory infiltrates, and valvular destruction (15). They show fibrotic, scarred areas. Valvular inflammatory infiltrates mainly consisted of foamy macrophages and lymphocytes. The foamy histiocytes were filled with dense and granular material that was strongly positive on PAS staining and resistant to diastase or immunopositive with a specific antibody against T. whipplei. T. whipplei–infected macrophages were seen in the vegetations on the surface of the heart valves and more deeply in the valvular tissues (Figure 2). An arterial embolus surgically removed from the lower limb of patient 22 was positive by immunodetection (15). However, 1 year before the heart valve was removed, this embolus had been histologically analyzed but infection was not suspected. Only after the valve was found to be positive for T. whipplei did subsequent analyses show that the embolus was positive for T. whipplei. Small bowel biopsy samples were obtained for 19 patients; all samples were negative by PAS staining, probably ruling out asymptomatic involvement of the gastrointestinal tract.

Figure 2.

Aortic valve from patient with Tropheryma whipplei endocarditis. A) Hematoxylin–eosin–saffron stain (original magnification ×100). B) Foamy macrophages containing characteristic inclusion bodies (periodic acid–Schiff stain; original magnification ×200). C) Immunostaining of T. whipplei with polyclonal rabbit antibody against T. whipplei and Mayer’s hemalum counterstain (original magnification ×100). No destruction of this valve is visible.

Two strains of T. whipplei were isolated from blood specimens, and 7 strains (including the strain from the index case-patient) from heart valve culture (5). For patient 20, a strain was isolated from the blood and heart valve specimens. The delay in primary isolation was 2 weeks for the heart valve sample and 8 weeks for the blood sample. No other microorganism was isolated. Serum was available for 18 patients. According to our previously established criteria, 10 (55.5%) patients had a negative or weakly positive serologic profile, as is observed for patients with classic Whipple disease, and 8 (44.5%) patients had a frankly positive profile, as is observed for chronic carriers. This finding suggests a potentially less decreased antibody-mediated immune response for these patients (17). Thus, the previously established serologic profile for patients with classic Whipple disease is observed significantly less frequently among patients with T. whipplei endocarditis (10/18) than among patients with classic Whipple disease (56/60; p<0.001). The serologic profile previously observed for chronic carriers also occurs significantly less frequently among patients with endocarditis (24/26 vs 8/18; p = 0.01).

T. whipplei genotype was obtained for 19 heart valves samples. Genotype 3 was detected in 5 samples, and genotype 1 was detected in 2 samples. The other 12 samples harbored a unique genotype. Genotypes for 4 patients were those previously detected in other circumstances (genotypes 8, 11, 19, and 97). Only patients with T. whipplei endocarditis had genotypes 7, 24, 87, 90, 96, 99, 113, 117. For 1 of these patients (patient 13), genotype 7 was detected in a heart valve sample at the time of diagnosis in 2002, but genotype 101 was detected in saliva and fecal samples in 2011 (Table 2). The patient did not have characteristics that favor endocarditis relapse.

Table 2. Treatment, outcome, and follow-up data for 14 patients with Tropheryma whipplei endocarditis managed entirely by our team*.

| Patient no.† | First drug (duration) | Second drug (duration)† | Outcome | Length of follow-up at the end of the last treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

AMX + GEN (15 d) |

DOX + HCQ (ongoing) |

Well, including arthralgia disappearance |

Ongoing treatment |

| 2 | AMX + GEN (15 d) | DOX + HCQ (ongoing) | Well, including arthralgia disappearance | Ongoing treatment |

| 5 | CEF + GEN (15 d) | DOX + HCQ (ongoing) | Well | Ongoing treatment |

| 6 | NA | DOX + HCQ (1 yr) | Well | 1 yr |

| 7 | AMX + GEN (NA) | DOX + HCQ (7 mo) | Relapse 4 mo after the end of treatment; prosthetic dehiscence without fever; heart valve positive by PAS and immunohistochemical staining; negative by PCR | Ongoing new treatment |

| 9 | AMC + GEN (11 d) | DOX + HCQ (ongoing) | Well | Ongoing treatment |

| 12 | CEF (5 d) | DOX + HCQ (ongoing) | Well | Ongoing treatment |

| 14 | CEF + GEN (15 d) | DOX + HCQ (1 yr) | Well | 2.5 yr |

| 17 | CEF + GEN (15 d) | DOX + HCQ (1.5 yr) | Well | 3.5 yr |

| 20 | NA | DOX + HCQ (1 yr) | Well | 6 mo |

| 21 | AMX + GEN (18 d) | SXT (1.5 yr) | Well | 5 yr |

| 23 | VAN + DOX + OFX (19 d) | DOX + HCQ (1.5 yr) | 1 yr after end of treatment, saliva sample positive for T. whipplei by PCR (genotype NA); SXT started and continued for 12 mo | 9 mo after onset of lifelong prophylaxis |

| 5.5 yr after end of treatment, saliva and fecal samples positive for T. whipplei by PCR (new genotype: 101); no cardiac abnormalities observed; started lifelong prophylaxis with DOX at 100 mg 2×/d; well | ||||

| 24 | AMX + GEN (4 wk) | DOX + HCQ (1.5 yr) | Well | 2 yr, then colon cancer and death |

| 25 | AMX + GEN (15 d) | SXT (14 mo) | 12 mo after the end of the treatment: saliva specimen positive for T. whipplei by PCR (genotype NA); SXT replaced DOX + HCQ after a perforated sigmoid diverticulitis with spreading peritonitis for 18 mo; well | 6 yr |

*Team from Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Marseille, Marseille, France. All patients had undergone heart valve surgery. AMX, amoxicillin; GEN, gentamicin; HCQ,, hydroxychloroquine; PAS, periodic acid–Schiff; CEF, ceftriaxone ; AMC, amoxicillin–clavulanate; VAN, vancomycin; DOX, doxycycline; OFX, ofloxacin. †DOX at 100 mg 2×/d and HCQ at 200 mg 3×/ d; SXT at 320 mg trimethoprim and 1,600 mg sulfamethoxazole 3×/d.

Treatment and Outcomes

We focused on 14 patients for whom the entire treatment was managed by our team, 13 of whom regularly consulted author D.R. (Table 2). Overall, 12 patients received a combination of doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine for 7–18 months, and 2 received trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole. One patient who experienced relapse received treatment for 7 months. According to analysis of saliva and fecal samples, 2 patients had been colonized by T. whipplei at another time. Colonization of 1 of these patients was with a new strain, but neither had cardiac abnormalities. We prescribed treatment for these patients, including 1 who had been taking lifelong prophylactic doxycycline, as reported for a patient with classic Whipple disease (25).

Literature Review

After checking for repeated reporting, we found 49 patients who met our criteria for T. whipplei endocarditis reported in the literature (Technical Appendix Table 4); 7 (14.5%) were female (3,4,7–11,22–39). The patients were predominantly from Germany (15 [30.6%]) and Switzerland (12 [24.5%]). Figure 3 shows the number of reported cases of T. whipplei endocarditis per million inhabitants in Europe. The number of cases reported in the literature since 2010 has dramatically increased (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Number of reported cases of Tropheryma whipplei endocarditis per 1 million inhabitants in each country of Europe (www.statistiques-mondiales.com/union_europeenne.htm).

Figure 4.

Number of cases of Tropheryma whipplei endocarditis reported in the literature since the first detection of this condition in 1997. Cases in 2013 are reported through April.

Among the cases reported in the literature, fever was scarcely observed (8/33, 24.2%), but vegetations (28/33, 84.8%) and involvement of the aortic valve (29/48, 60.4%) were frequent. The clinical manifestations were mainly heart failure (25/35, 71.4%), acute ischemic stroke (9/35, 25.7%), and peripheral arterial embolism (4/35, 11.4%). Arthralgia was observed significantly less frequently among patients reported in the literature (15/37, 40.5%) than among the patients we report (75%, p = 0.01). However, if the 14 patients from the recently published series from Germany (7) are excluded from the analysis, this difference is not significant (14/23, 60.9%; p = 0.4). The percentage of patients with a history of valvular heart disease was similar among the patients reported here (32%) and the patients reported in the literature (12/33, 36.4%; p = 0.9), but this analysis excludes the series from Germany. The patients in the Germany study experienced significantly more valvular heart disease before diagnosis with endocarditis (13/15, 87%; p = 0.002). The diagnosis was performed by analyzing the removed heart valve for all but 2 of these patients (patients 25 and 33). The clinical manifestations for 2 patients were mainly weight loss, not cardiac disease. The diagnosis for patient 25 was made by a positive PCR on blood and pleural effusion and for patient 39 by a positive PCR from a duodenal biopsy sample. According to the current modified Duke criteria (20), before the examination of the heart valve specimens, only 2 (4.25%) patients met the criteria for definite endocarditis (Technical Appendix Table 1).

Data regarding treatment were available for 45 patients (Technical Appendix Table 4). A total of 43 patients received antimicrobial drugs; at least 15 compounds were used. The most common treatment was trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (34 patients); 10 of these patients had previously received ceftriaxone for 2 weeks. The maximum duration of treatment was 2 years; 24 patients received treatment for 1 year. Death was reported for 8 (21%) of 38 patients.

Discussion

Although the first description of T. whipplei endocarditis was made 15 years ago, diagnosing this disease remains difficult because clinical signs are often those of cardiac disease rather than infection. The first case was detected by chance when a broad-spectrum PCR was systematically applied to heart valve specimens (3). However, the diagnosis of T. whipplei endocarditis is still the result of chance because there are no diagnostic criteria. Thus, diagnosis is still made after 16S rRNA PCR of a removed valve.

The incidence of a disease depends of 3 parameters: physician vigilance, available diagnostic tools, and the true incidence. A team in Switzerland was the first to apply systematic broad-spectrum molecular diagnostics to heart valves (3). Although the efforts of that team might explain the high number of reported cases in Switzerland, studies in Marseille, France, that used the same technique did not detect T. whipplei in heart valves (40). In Germany, several physicians have been interested in Whipple disease for a long time, resulting in the development of new tools (1,32). In the Rhone-Alpes area of France, physicians have been interested in Whipple disease for several years, resulting in increased attention to T. whipplei (26).

With regard to the global effects of T. whipplei endocarditis, there seems to be a geographic gradient with higher incidence in eastern-central France, Switzerland, and Germany. Because 16S rRNA PCR is used in many areas to test for blood culture–negative endocarditis, which would enable detection of T. whipplei in heart valves, and significant differences in incidence rates exist, a potential bias seems unlikely (6,12). Whipple disease reportedly occurs mainly in white persons (1). Genotyping shows that a same strain of T. whipplei can be involved in chronic infections, acute infections, and chronic carriage. In addition, T. whipplei strains are heterogenic; thus, a patient could be colonized multiple times by a new strain (14). These data argue for the presence of specific host defects in patients with chronic infections. These defects could be linked to genetic factors that could explain the geographic distribution.

Even in the absence of diagnostic criteria, the reports of ≈50 cases in the literature enabled us to propose several characteristics that might help clinicians recognize potential T. whipplei endocarditis. This disease occurs mainly in white men who are ≈50 years of age with cardiac manifestations including heart failure, acute ischemic stroke, and peripheral arterial embolism. These patients might have complained about arthralgia for several years and might have recently received immunosuppressants (4,7,28,33,34). Arthralgia was not frequently reported among patients in the Germany series (7) but was reported as a more prominent symptom by others (4,9,26,29,31,33,37,38). Arthralgia is sometimes subtle and noticed only after a careful clinical investigation (37). Because we have never received articular specimens from these patients, we do not know whether the joints are reactive or correspond to a second localization of T. whipplei. Of note, however, these arthralgias are highly sensitive to antimicrobial drugs. Overall, middle-age and older men with subacute endocarditis and no fever or low-grade fever should be asked about the presence of arthralgia because the combination of endocarditis and arthralgia suggests T. whipplei infection.

For now, diagnosis of T. whipplei endocarditis is made late, performed by molecular analysis of surgically obtained heart valves; specific repeat PCR is used because broad-spectrum PCR might lack sensitivity (40). Serologic assays only distinguish between classic Whipple disease and gastrointestinal carriage (17). Screening of saliva and fecal specimen has poor predictive value for diagnosis. The diagnostic situation is not satisfactory, but diagnostic improvements are challenging. Only optimization of molecular techniques and culture will enable diagnosis before heart valve analysis. Currently, 16S rRNA amplification performed on blood specimens lacks sensitivity (6). Specific repeat PCR is more sensitive (13), enabling diagnosis of 31.2% of the patients reported here. In Marseille, for cases of blood culture–negative endocarditis, we systematically apply specific repeat PCR on blood specimens; this protocol enables us to make the diagnosis before heart valve removal (6). We suggest adding performance of repeat PCR for T. whipplei on blood specimens as a major criterion in the Duke classification for endocarditis, as PCR or serologic testing for C. burnetii have been added (20). The application of this criterion for patients who have benefited from molecular analysis of blood specimens significantly increases the definitive diagnosis of endocarditis (1/18 vs 6/18; p = 0.03) before the heart valve analysis. In the future, blood specimens from patients with blood culture–negative endocarditis should be also inoculated systematically on specific media. For patients for whom echocardiography is not informative, preliminary data have shown that positron emission tomography and computed tomography show promise, mainly for the detection of silent peripheral embolic events and infectious metastases (21).

There is no standard treatment for T. whipplei endocarditis. Our series represents a large study with a standardized treatment strategy and follow-up. On the basis of drug sensitivity data, reported resistance of T. whipplei to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, and prior experience, a combination of doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine was used. A 12- to 18-month treatment strategy and analysis of the drug concentrations every 3 months seem reasonable. Patients must be forewarned about the risk for photosensitivity when taking doxycycline. All patients in our series have benefitted from heart valve removal; but in the future, to make the diagnosis before heart valve surgery is performed, we advise following the current recommendations for the surgical indications in infective endocarditis (21). Even if the approach lacks sensitivity, for patient follow-up, we suggest checking for the presence of T. whipplei in the saliva, fecal samples, and blood 2 months after the end of treatment. Subsequent analysis should be performed every 6 months for 2 years and every year for the life of the patient. Echocardiography should be performed yearly to detect relapses. We decided to treat T. whipplei recolonization, but we do not know if this measure is necessary.

T. whipplei endocarditis differs from classic Whipple disease. Classic Whipple disease involves most organs. Its diagnosis is based on the presence of T. whipplei–infected macrophages in intestinal tissues. T. whipplei endocarditis is an infection and not a potential cardiovalvular colonization with the bacterium because T. whipplei is the only infectious agent detected in heart valves, surrounded by an inflammatory process, and inside the macrophages. For white men >40 years of age with subacute endocarditis and arthralgia, T. whipplei infection should be suspected and the organism searched for in blood specimens by using specific repeat PCR and axenic culture, sampled in EDTA and heparin tubes, respectively.

Classification of the patients with Tropheryma whipplei endocarditis; proportion and geographic distribution of Tropheryma whipplei endocarditis cases; PCR and histological results for samples from 28 patients with Tropheryma. whipplei endocarditis; and characteristics of patients with endocarditis according to literature review.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the patients who took part in this study and thank the staff members of the referring medical institutions for help in obtaining specimens.

This study was supported by the Crédit Ministériel “Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique” 2009.

Dr Fenollar is a physician and research scientist at the Unité des Rickettsies, Aix-Marseille Université. Her main research interests include T. whipplei and Whipple disease.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Fenollar F, Célard M, Lagier J-C, Lepidi H, Fournier P-E, Raoult D. Tropheryma whipplei endocarditis. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2013 Nov [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1911.121356

References

- 1.Moos V, Schneider T. Changing paradigms in Whipple’s disease and infection with Tropheryma whipplei. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:1151–8. 10.1007/s10096-011-1209-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lagier JC, Lepidi H, Raoult D, Fenollar F. Systemic Tropheryma whipplei: clinical presentation of 142 patients with infections diagnosed or confirmed in a reference center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2010;89:337–45. 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181f204a8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldenberger D, Kunzli A, Vogt P, Zbinden R, Altwegg M. Molecular diagnosis of bacterial endocarditis by broad-range PCR amplification and direct sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2733–9 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gubler JG, Kuster M, Dutly F, Bannwart F, Krause M, Vögelin HP, et al. Whipple endocarditis without overt gastrointestinal disease: report of four cases. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:112–6. 10.7326/0003-4819-131-2-199907200-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raoult D, Birg M, La Scola B, Fournier P, Enea M, Lepidi H, et al. Cultivation of the bacillus of Whipple's disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:620–5. 10.1056/NEJM200003023420903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fournier PE, Thuny F, Richet H, Lepidi H, Casalta JP, Arzouni JP, et al. Comprehensive diagnostic strategy for blood culture–negative endocarditis: a prospective study of 819 new cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:131–40. 10.1086/653675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geissdörfer W, Moos V, Moter A, Loddenkemper C, Jansen A, Tandler R, et al. High frequency of Tropheryma whipplei in culture-negative endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:216–22. 10.1128/JCM.05531-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voldstedlund M, Norum PL, Baandrup U, Klaaborg KE, Fuursted K. Broad-range PCR and sequencing in routine diagnosis of infective endocarditis. APMIS. 2008;116:190–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2008.00942.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosshard PP, Kronenberg A, Zbinden R, Ruef C, Bottger EC, Altwegg M. Etiologic diagnosis of infective endocarditis by broad-range polymerase chain reaction: a 3-year experience. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:167–72. 10.1086/375592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grijalva M, Horvath R, Dendis M, Erny J, Benedik J. Molecular diagnosis of culture negative infective endocarditis: clinical validation in a group of surgically treated patients. Heart. 2003;89:263–8. 10.1136/heart.89.3.263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marín M, Muñoz P, Sánchez M, del Rosal M, Alcalá L, Rodríguez-Créixems M, et al. Molecular diagnosis of infective endocarditis by real-time broad-range polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing directly from heart valve tissue. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:195–202. 10.1097/MD.0b013e31811f44ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benslimani A, Fenollar F, Lepidi H, Raoult D. Bacterial zoonoses and infective endocarditis, Algeria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:216–24. 10.3201/eid1102.040668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fenollar F, Laouira S, Lepidi H, Rolain J, Raoult D. Value of Tropheryma whipplei quantitative PCR assay for the diagnosis of Whipple’s disease: usefulness of saliva and stool specimens for first-line screening. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:659–67. 10.1086/590559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li W, Fenollar F, Rolain JM, Fournier PE, Feurle GE, Müller C, et al. Genotyping reveals a wide heterogeneity of Tropheryma whipplei. Microbiology. 2008;154:521–7. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/011668-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lepidi H, Fenollar F, Dumler JS, Gauduchon V, Chalabreysse L, Bammert A, et al. Cardiac valves in patients with Whipple endocarditis: microbiological, molecular, quantitative histologic, and immunohistochemical studies of 5 patients. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:935–45. 10.1086/422845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raoult D, Fenollar F, Birg ML. Culture of Tropheryma whipplei from the stool of a patient with Whipple’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1503–5. 10.1056/NEJMc061049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenollar F, Amphoux B, Raoult D. A paradoxical Tropheryma whipplei Western blot differentiates patients with Whipple’s disease from asymptomatic carriers. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:717–23. 10.1086/604717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ansemant T, Celard M, Tavernier C, Maillefert JF, Delahaye F, Ornetti P. Whipple’s disease endocarditis following anti-TNF therapy for atypical rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:622–3. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daïen CI, Cohen JD, Makinson A, Battistella P, Bilak EJ, Jorgensen C, et al. Whipple’s endocarditis as a complication of tumour necrosis factor-alpha antagonist treatment in a man with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49:1600–2. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, Nettles R, Fowler VG Jr, Ryan T, et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:633–8. 10.1086/313753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thuny F, Grisoli D, Collart F, Habib G, Raoult D. Management of infective endocarditis: challenges and perspectives. Lancet. 2012;379:965–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60755-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Besnard S, Cady A, Flecher E, Fily F, Revest M, Arvieux C, et al. Should we systematically perform central nervous system imaging in patients with Whipple’s endocarditis? Am J Med. 2010;123:962.e–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Brondex A, Jobic Y. Infective endocarditis as the only manifestation of Whipple’s disease: an atypical presentation. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris). 2012;61:61–3. 10.1016/j.ancard.2010.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saba M, Rollot F, Park S, Grimaldi D, Sicard D, Abad S, et al. Whipple disease, initially diagnosed as sarcoidosis. Presse Med. 2005;34:1521–4. 10.1016/S0755-4982(05)84217-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lagier JC, Fenollar F, Lepidi H, Raoult D. Evidence of lifetime susceptibility to Tropheryma whipplei in patients with Whipple’s disease. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1188–9. 10.1093/jac/dkr032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Célard M, de Gevigney G, Mosnier S, Buttard P, Benito Y, Etienne J, et al. Polymerase chain reaction analysis for diagnosis of Tropheryma whippelii infective endocarditis in two patients with no previous evidence of Whipple’s disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1348–9. 10.1086/313477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan V, Wang B, Veinot JP, Suh KN, Rose G, Desjardins M, et al. Tropheryma whipplei aortic valve endocarditis without systemic Whipple’s disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:e804–6. 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dreier J, Szabados F, von Herbay A, Kroger T, Kleesiek K. Tropheryma whipplei infection of an acellular porcine heart valve bioprosthesis in a patient who did not have intestinal Whipple’s disease. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4487–93. 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4487-4493.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Escher R, Roth S, Droz S, Egli K, Altwegg M, Tauber MG. Endocarditis due to Tropheryma whipplei: rapid detection, limited genetic diversity, and long-term clinical outcome in a local experience. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:1213–22. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03038.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gabus V, Grenak-Degoumois Z, Jeanneret S, Rakotoarimanana R, Greub G, Genne D. Tropheryma whipplei tricuspid endocarditis: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports. 2010;4:245. 10.1186/1752-1947-4-245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolek M, Zaloudikova B, Freiberger T, Brat R. Aortic and mitral valve infective endocarditis caused by Tropheryma whipplei and with no gastrointestinal manifestations of Whipple’s disease. Klin Mikrobiol Infekc Lek. 2007;13:213–6 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mallmann C, Siemoneit S, Schmiedel D, Petrich A, Gescher DM, Halle E, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization to improve the diagnosis of endocarditis: a pilot study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:767–73. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02936.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miguelena J, Munoz R, Maseda R, Epeldegui A. Endocarditis due to Tropheryma whipplei. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2010;63:250–1. 10.1016/S0300-8932(10)70052-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naegeli B, Bannwart F, Bertel O. An uncommon cause of recurrent strokes: Tropheryma whippelii endocarditis. Stroke. 2000;31:2002–3 . 10.1161/01.STR.31.8.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Voldstedlund M, Pedersen LN, Baandrup U, Fuursted K. Whipple’s disease—a cause of culture-negative endocarditis. Ugeskr Laeger. 2004;166:3731–2 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West D, Hutcheon S, Kain R, Reid T, Walton S, Buchan K. Whipple’s endocarditis. J R Soc Med. 2005;98:362–4 . 10.1258/jrsm.98.8.362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whistance RN, Elfarouki GW, Vohra HA, Livesey SA. A case of Tropheryma whipplei infective endocarditis of the aortic and mitral valves in association with psoriatic arthritis and lumbar discitis. J Heart Valve Dis. 2011;20:353–6 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams OM, Nightingale AK, Hartley J. Whipple’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1479–81. 10.1056/NEJMc070234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Love SM, Morrison L, Appleby C, Modi P. Tropheryma whipplei endocarditis without gastrointestinal involvement. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;15:161–3. 10.1093/icvts/ivs116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greub G, Lepidi H, Rovery C, Casalta JP, Raoult D. Diagnosis of infectious endocarditis in patients undergoing valve surgery. Am J Med. 2005;118:230–8. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Classification of the patients with Tropheryma whipplei endocarditis; proportion and geographic distribution of Tropheryma whipplei endocarditis cases; PCR and histological results for samples from 28 patients with Tropheryma. whipplei endocarditis; and characteristics of patients with endocarditis according to literature review.