Abstract

During 2010–2013, we recruited 16 persons with confirmed Mayaro virus infection in the Peruvian Amazon to prospectively follow clinical symptoms and serologic response over a 12-month period. Mayaro virus infection caused long-term arthralgia in more than half, similar to reports of other arthritogenic alphaviruses.

Keywords: alphavirus, arboviruses, Peru, arthralgia, chronic pain, diagnosis, viruses, vector-borne infections

Since the discovery of Mayaro virus (MAYV) in Trinidad in 1954, the etiologic agent of Mayaro fever has been identified in French Guiana, Suriname, Venezuela, Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil (1–9). The presumed primary vectors, Haemagogus mosquitoes, inhabit rural settings and tree canopies, a factor that may explain the relative paucity of cases and restricted endemicity. However, Aedes aegypti mosquitoes have been shown to be competent vectors of MAYV in the laboratory (10), suggesting that an urban-dwelling arthropod could be a vector of this virus over a wider scale. MAYV infection has been demonstrated in tourists returning from the Amazon region, highlighting not only the need to consider MAYV in febrile returned travelers, but also a possible role in global transmission (11).

Incapacitating chronic joint pain has been described with other arthritogenic alphaviruses (12), but little is known about the prognosis and serologic response over long periods after MAYV infection. Therefore, we conducted a prospective 1-year longitudinal study to determine the clinical manifestations and to describe the serologic response among humans with Mayaro fever in the Peruvian Amazon Basin.

The Study

Persons identified for this cohort were recruited in a passive febrile surveillance study in 15 health centers in 4 Peruvian cities: Iquitos, Yurimaguas, Chanchamayo, and Puerto Maldonado (Figure 1). Persons meeting the following criteria were recruited: age >5 years, oral/tympanic temperature >38°C (or axillary >37.5°C), and no obvious focus of infection. Written consent was obtained from all adults and from a parent or guardian for participants <18 years of age; participants 8–17 years of age also provided written assent. The surveillance period of this study was December 6, 2010–April 30, 2012. Follow-up appointments continued for another year, through April 5, 2013. The institutional review boards of the US Naval Medical Research Unit No. 6 and the Peruvian Ministry of Health approved the protocol.

Figure 1.

Map of Peru. Sites for study of Mayaro virus–infected patients are marked with a dot.

Compared with the day of the visit for acute illness (acute-phase visit), follow-up evaluations occurred at 20 (SD) days (±10 days), 3 months (±10 days), 6 months (±15 days), and 12 months (±30 days). At the acute-phase visit and at all follow-up visits, a blood sample was obtained.

For every participant, we attempted to determine the cause of infection by testing acute-phase serum for virus in Ae. albopictus (C6/36) and African green monkey kidney (Vero 76) cell culture (with immunofluorescence assay) and for viral nucleic acid by reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR). Capture IgM and IgG ELISAs were performed at 1:100 dilution on the acute-phase and all follow-up samples to evaluate antibody responses to MAYV and other endemic arboviruses (i.e., Venezuelan equine encephalitis, Oropouche, group C, Guaroa, and dengue viruses) (6). Samples with detectable IgM or IgG were serially diluted and retested. Seroconversion was defined as a >4-fold increase in IgM titer between the acute-phase visit and the second visit. A Mayaro fever case was defined as IgM seroconversion or virus detected by isolation or by RT-PCR. In addition, we collected throat swabs from participants with pharyngeal erythema at the acute-phase visit and urine samples from the 3-month follow-up visit to determine the presence of MAYV with RT-PCR (13).

Of 2,094 febrile participants enrolled, 16 (0.8%) had Mayaro fever (Table 1). Of the 16 persons with Mayaro fever, 11 had MAYV isolated by the cell culture assays (11 in both Vero 76 and C6/36), 13 were MAYV positive by RT-PCR, and all had IgM ELISA seroconversion between the acute-phase and 20-day follow-up visits (Table 1). In all 16 participants, no IgM ELISA seroconversion occurred for endemic non-alphavirus viruses (i.e., Oropouche, group C, Guaroa, and dengue viruses). Four participants demonstrated IgM ELISA seroconversion against another alphavirus, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, but these 4 all had MAYV identified by immunofluorescence assay and by RT-PCR. Using RT-PCR, we did not detect MAYV in 2 acute visit throat swabs, any second-visit (20-day) serum samples, and any third-visit (3-month) urine samples.

Table 1. Demographic factors and laboratory findings at 5 encounters for patients with MAYV infection, Amazon Basin region, Peru, 2010–2013*.

| Patient | Age, y/sex | Day of illness at enrollment | Isolation | RT-PCR† | IgM; IgG‡ |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute phase | Day 20 | Month 3 | Month 6 | Month 12 | |||||

| 1 | 12/F | 2 | MAYV | MAYV | 0; 0 | 6,400; 100 | 0; 6,400 | 0; 25,600 | 0; 25,600 |

| 2 | 28/F | 2 | MAYV | MAYV | 0; 0 | 1,600; 100 | 0; 1,600 | 0; 6,400 | 0; 25,600 |

| 3 | 19/F | 4 | Neg | Neg | 0; 0 | 6,400; 100 | 0; 1,600 | – | – |

| 4 | 11/M | 2 | MAYV | MAYV | 0; 0 | 1,600; 100 | 0; 1,600 | 0; 1,600 | 0; 6,400 |

| 5 | 41/F | 2 | MAYV | MAYV | 0; 0 | 25,600; 400 | 0; 1,600 | 0; 1,600 | 0; 6,400 |

| 6 | 20/M | 2 | Neg | Neg | 0; 0 | 6,400; 1,600 | 0; 1,600 | 0; 400 | – |

| 7 | 36/F | 1 | MAYV | MAYV | 0; 0 | 6,400; 100 | 0; 102,400 | 0; 409,600 | 0; 102,400 |

| 8 | 35/F | 1 | MAYV | MAYV | 0; 0 | 1,600; 100 | 400; 1,600 | 0; 25,600 | 0; 25,600 |

| 9 | 43/M | 2 | MAYV | MAYV | 0; 0 | 1,600; 0 | 0; 1,600 | 0; 6,400 | 0; 6,400 |

| 10 | 34/F | 3 | MAYV | MAYV | 0; 0 | 6,400; 100 | 0; 1,600 | 0; 6,400 | 0; 25,600 |

| 11 | 46/F | 3 | Neg | MAYV | 0; 0 | 1,600; 400 | 0; 6,400 | – | – |

| 12 | 51/M | 4 | Neg | Neg | 0; 0 | 6,400; 400 | 0; 1,600 | 0; 6,400 | 0; 6,400 |

| 13 | 40/F | 1 | MAYV | MAYV | 0; 0 | 1,600; 400 | 400; 25,600 | 0; 25,600 | 0; 25,600 |

| 14 | 11/M | 2 | MAYV | MAYV | 0; 0 | 1,600; 400 | 0; 25,600 | 0; 6,400 | 0; 6,400 |

| 15 | 11/M | 3 | MAYV | MAYV | 0; 0 | 1,600; 400 | 0; 6,400 | 0; 25,600 | 0; 25,600 |

| 16 | 64/M | 2 | Neg | MAYV | 0; 0 | 6,400; 25,600 | 400; 6,400 | 0; 6,400 | 0; 6,400 |

*MAYV, Mayaro virus; RT-PCR, reverse transcription PCR; Neg, negative; –, visits not attended by the patient. †Isolation and RT-PCR results are from the acute-phase visit. ‡For ELISA IgM and IgG results, endpoint titration values were determined. All serology values are expressed as inverse titers.

Besides fever, the most common symptoms affecting participants in the acute stage of MAYV infection were malaise, headache, arthralgia, myalgia, and retro-orbital pain. The prevalence of these and other nonjoint signs and symptoms at the acute-phase and follow-up visits are available in the Technical Appendix Table.

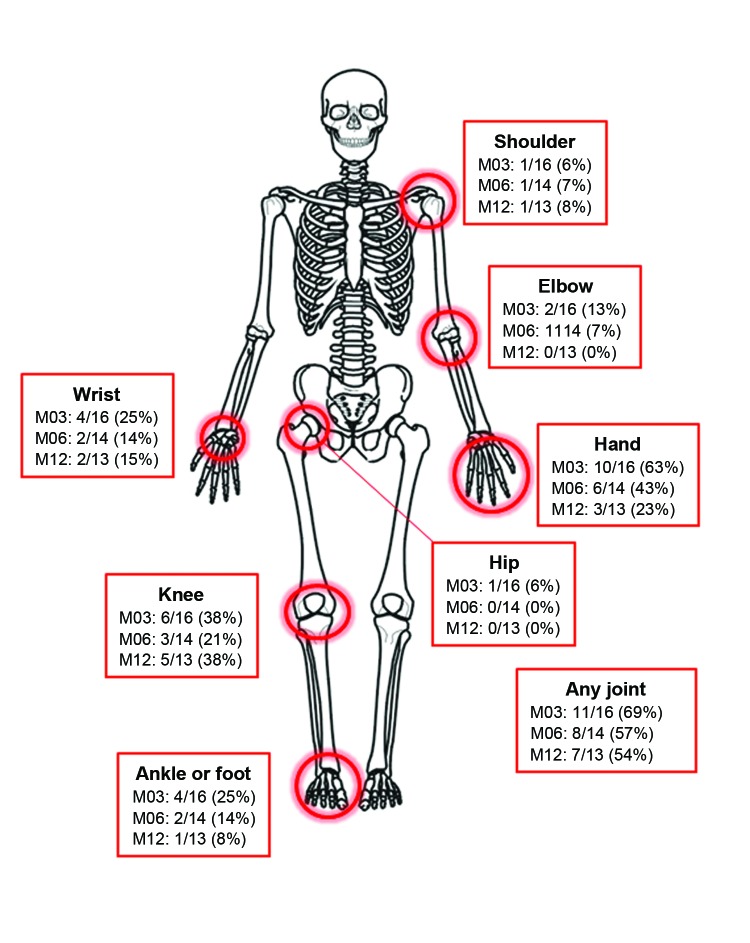

Although reports of joint pain waned in study participants by the second (20-day) visit, complaints increased at 3 months and persisted in 54% even after 12 months. Joints of the hand, wrist, elbow, feet, and knee were identified as problematic, whereas hip or axial joint pain was rare (Figure 2). The chronic joint pain often interfered with activities of daily living (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of joint involvement at the different follow-up visits for Mayaro virus infection, Amazon Basin region, Peru, 2010–2013. Denominators varied because of varying numbers of participants reporting to each follow-up visit. M03, 3-month follow-up; M06, 6-month follow-up; M12, 12-month follow-up.

Table 2. Specific limitations and length of time of limitation caused by long-term joint pain in 16 patients with Mayaro virus infection, Peru, 2010–2013.

| Patient | Occupation | Limitation secondary to long-term joint pain | Duration of limitation, mo |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Student | Inability to write because of pain and stiffness in finger joints of both hands; inability to walk long distances because of pain in knees and ankles | 12 |

| 2 | Office worker | No long-term limitations | NA |

| 3 | Housewife | No long-term limitations at 3 mo; lost to follow-up at 6 mo | NA |

| 4 | Student | No long-term limitations | NA |

| 5 | Housewife | No long-term limitations | NA |

| 6 | Soldier | No long-term limitations at 6 mo; lost to follow-up at 12 mo | NA |

| 7 | Housewife | Limited ability to perform housework because of pain in hand and wrist joints | 3 |

| 8 | Secretary | Inability to remain seated for long periods | 8 |

| 9 | Electrician and other manual labor | Limited ability to climb electric poles because of pain and stiffness in both hands and elbows | 12 |

| 10 | Teacher | Inability to lecture standing up for prolonged periods because of pain in feet and knees | 12 |

| 11 | River boat cook | Limited ability to cook because of pain in both hands, wrists, and knees at 3 mo; lost to follow-up at 6 mo | 3 |

| 12 | Teacher | Difficulty writing because of pain in both hands and arms and pain in shoulders with movement | 12 |

| 13 | Teacher | Inability to lecture standing up for prolonged periods because of pain in hands, knees, and ankles | 6 |

| 14 | Student | Inability to write because of pain and stiffness in finger joints of both hands | 6 |

| 15 | Student | Moderate pain when playing sports, such as basketball | 3 |

| 16 | Driver | No specific limitations noted | NA |

*NA, not applicable.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that persons with acute Mayaro fever often have many nonspecific symptoms but may continue to have chronic joint pain for at least 1 year after acute illness. Our study offers physicians valuable prognostic data to share with patients. It also indicates the need to consider MAYV infection in patients with seronegative arthritis (i.e., negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies) in regions to which MAYV is endemic.

Previous reports have documented persistent joint pain after MAYV infection (2–5,9,11), although all of these were either solitary case reports or case series of <4 persons. By using follow-up periods ranging from 1 month to 12 months, most of these studies identified persistent symptoms in the fingers. Involvement of joints of the wrist, ankle, and knee also were mentioned, similar to the participants in our study.

Long-term manifestations of infection with other alphaviruses have been more robustly characterized, with persistent arthralgia being commonly described. Follow-up of chikungunya virus–infected patients on Réunion Island revealed that ≈60% had joint pain >3 years after acute illness that most often affected the fingers, wrists, knees, and ankles (14). Sindbis virus infection in a cohort in Finland resulted in persistent arthralgia lasting at least a year in half of those infected, with ankles, fingers, and wrists being most often affected (15). One caveat of our study and other studies is the difficulty in definitively attributing persistent arthralgia solely to viral infection, although our participants’ limitations in activities of daily living were all described as starting after their acute Mayaro fever illness.

IgM seroconversion occurred in all of the participants in our study that were identified with either isolation or RT-PCR, consistent with another report that noted the reliability of serology in detecting MAYV infection (9). In our study participants identified by serology, both RT-PCR and culture were more sensitive than what others have found for Sindbis virus infection, for which 1 study found sensitivities of 7% and 1%, respectively (15). However, RT-PCR and culture were negative in the only 2 participants in our study who had Mayaro fever after day 3 of symptoms, suggesting a narrow window when these assays may be effective.

No effective vaccine or antiviral agent exists for the arthritogenic alphaviruses, and treatment relies mainly on supportive modalities, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (12). Our results offer evidence that MAYV, similar to other alphaviruses, may cause protracted joint symptoms and provide further impetus to the development of more effective preventive and treatment strategies.

Signs and symptoms in patients with Mayaro virus infection at the acute-phase visit and each follow-up visit, Amazon Basin region, Peru, 2010–2013.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brett Forshey for his critical reading of this manuscript and Karen Campos and Yojani Aguilar for their assistance with field work and follow-up in Yurimaguas.

This work was supported by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center’s Global Emerging Infections Systems Research Program. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and final responsibility for the decision to submit this publication.

Biography

Dr Halsey is a board-certified infectious diseases physician, US Air Force officer, and Virology Department head at the US Naval Medical Research Unit No. 6 in Lima, Peru. His research interests include the clinical and epidemiologic aspects of flavivirus, alphavirus, and bunyavirus infections.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Halsey ES, Siles C, Guevara C, Vilcarromero S, Jhonston EJ, Ramal C, et al. Mayaro virus infection, Amazon Basin region, Peru, 2010–2013. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2013 Nov [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1911.130777

References

- 1.Anderson CR, Downs WG, Wattley GH, Ahin NW, Reese AA. Mayaro virus: a new human disease agent. II. Isolation from blood of patients in Trinidad, B.W.I. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1957;6:1012–6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talarmin A, Chandler LJ, Kazanji M, de Thoisy B, Debon P, Lelarge J, et al. Mayaro virus fever in French Guiana: isolation, identification, and seroprevalence. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:452–6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karbaat J, Jonkers AH, Spence L. Arbovirus infections in Dutch military personnel stationed in Surinam: a preliminary study. Trop Geogr Med. 1964;16:370–6 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres JR, Russell KL, Vasquez C, Barrera R, Tesh RB, Salas R, et al. Family cluster of Mayaro fever, Venezuela. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1304–6 . 10.3201/eid1007.030860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tesh RB, Watts DM, Russell KL, Damodaran C, Calampa C, Cabezas C, et al. Mayaro virus disease: an emerging mosquito-borne zoonosis in tropical South America. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:67–73 . 10.1086/515070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forshey BM, Guevara C, Laguna-Torres VA, Cespedes M, Vargas J, Gianella A, et al. Arboviral etiologies of acute febrile illnesses in western South America, 2000–2007. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e787. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mourão MP, Bastos Mde S, de Figueiredo RP, Gimaque JB, Galusso Edos S, Kramer VM, et al. Mayaro fever in the city of Manaus, Brazil, 2007–2008. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:42–6 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azevedo RS, Silva EV, Carvalho VL, Rodrigues SG, Nunes-Neto JP, Monteiro H, et al. Mayaro fever virus, Brazilian Amazon. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1830–2. 10.3201/eid1511.090461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinheiro FP, Freitas RB, Travassos da Rosa JF, Gabbay YB, Mello WA, LeDuc JW. An outbreak of Mayaro virus disease in Belterra, Brazil. I. Clinical and virological findings. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;30:674–81 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long KC, Ziegler SA, Thangamani S, Hausser NL, Kochel TJ, Higgs S, et al. Experimental transmission of Mayaro virus by Aedes aegypti. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:750–7 . 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hassing RJ, Leparc-Goffart I, Blank SN, Thevarayan S, Tolou H, van Doornum G, et al. Imported Mayaro virus infection in the Netherlands. J Infect. 2010;61:343–5. 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suhrbier A, Jaffar-Bandjee MC, Gasque P. Arthritogenic alphaviruses—an overview. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:420–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Powers AM, Aguilar PV, Chandler LJ, Brault AC, Meakins TA, Watts D, et al. Genetic relationships among Mayaro and Una viruses suggest distinct patterns of transmission. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:461–9 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schilte C, Staikovsky F, Couderc T, Madec Y, Carpentier F, Kassab S, et al. Chikungunya virus–associated long-term arthralgia: a 36-month prospective longitudinal study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2137. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurkela S, Manni T, Myllynen J, Vaheri A, Vapalahti O. Clinical and laboratory manifestations of Sindbis virus infection: prospective study, Finland, 2002–2003. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1820–9. 10.1086/430007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Signs and symptoms in patients with Mayaro virus infection at the acute-phase visit and each follow-up visit, Amazon Basin region, Peru, 2010–2013.