Abstract

Objective

To determine whether exposure to smoking imagery in films predicts smoking onset among never-smoking Mexican adolescents.

Methods

The analytic sample was comprised of 11- to 14-year old secondary school students who reported never having tried smoking at baseline, 83% (1741/2093) of whom were successfully followed up after one year. Exposure to 42 popular films that contained smoking was assessed at baseline, whereas smoking behavior and risk factors were assessed at baseline and follow up. Logistic regression was used to estimate bivariate and adjusted relative risks of trying smoking and current smoking at follow up.

Results

At follow up, 36% reported having tried smoking and 8% reported having smoked in the previous month. Students who were successfully followed up were exposed to an average of 43.8 minutes of smoking in the films they reported viewing at baseline. Adjusted relative risks (ARRs) indicated that students in the two highest levels of exposure to film smoking were more than twice as likely to have smoked in the previous 30 days at follow up (ARR3v1=2.44, 95%CI 1.31, 4.55; ARR4v1=2.23, 95% CI 1.19, 4.17). The adjusted relative risk of having tried smoking by follow up reached statistical significance only when comparing the 3rd highest to the lowest exposure group (ARR3v1=1.54, 95%CI 1.01, 2.64). Having a parent or best friend who smoked at baseline were the only other variables that independently predicted both outcomes.

Conclusions

Exposure to movie smoking is a risk factor for smoking onset among Mexican youth.

Keywords: Media, tobacco, smoking, longitudinal, adolescents

INTRODUCTION

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) monograph on mass media and smoking concluded that “evidence from cross-sectional, longitudinal, and experimental studies indicates a causal relation between exposure to youth smoking depictions and youth smoking initiation.”(1) Since the NCI monograph was written, additional cross-sectional (2–5) and longitudinal studies (6–9), including those that evidence how cumulative exposure to movies influence behavior over time by promoting pro-tobacco attitudes and perceived norms (5, 6, 10). Recent cross-sectional and longitudinal studies in Germany (3, 9) suggest the consistency of this causal relationship outside of the US. However, there has been little research on movie smoking as a risk factor for youth smoking in low- and middle-income countries, where the burden of the global tobacco epidemic is shifting.

The global distribution of films from the United States may influence youth in low- and middle-income countries who aspire to American cultural values. This kind of aspirational motivation for cigarettes from other countries of origin was documented for Thai youth (11), among whom a desire to “magically change yourself for one year” into an American teenager was associated both with higher exposure to American movies and consumption of Marlboro cigarettes. Our previous cross-sectional research found that exposure to movie smoking among Mexican adolescents was independently associated with current smoking and having ever smoked (5). Moreover, among never smokers, there was an association between higher exposure to movie smoking and hypothesized psychological mediators of the relationship between this exposure and smoking behavior, including higher susceptibility to smoking, more favorable attitudes toward smoking, and perceptions of higher peer smoking prevalence. This report describes the factors that predict smoking onset and current smoking after one year among those who reported never smoking at baseline.

METHODS

Sample population

Secondary schools that participated in this study included 18 secondary schools (4 in Zacatecas, 14 in Cuernavaca) from the 2003 Mexican administration of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) (12). Details on school selection for the current study have been described elsewhere (5). The study protocol was approved by the IRB at the Mexican National Institute of Public Health, and passive parental consent procedures were followed. In June 2006, 90.6% of registered students in selected classrooms (n=3874) completed a self-administered survey, which took approximately 45 minutes to finish. In June 2007, students in grades two and three in each school were again surveyed. We eliminated from the analytic sample observations from students who were in grade three at baseline because they were not followed up due to graduation to a different school (n=622). Because of our interest in smoking uptake, we included only students who reported never having tried smoking at baseline (n=2093). Elimination of those who had tried smoking at baseline was done to remove concerns about reverse causality, whereby adolescents who have tried smoking could be drawn to movies that contain smoking. Of the baseline never smokers, 83% (n=1741) were successfully followed up.

Measurement

Exposure to smoking in films

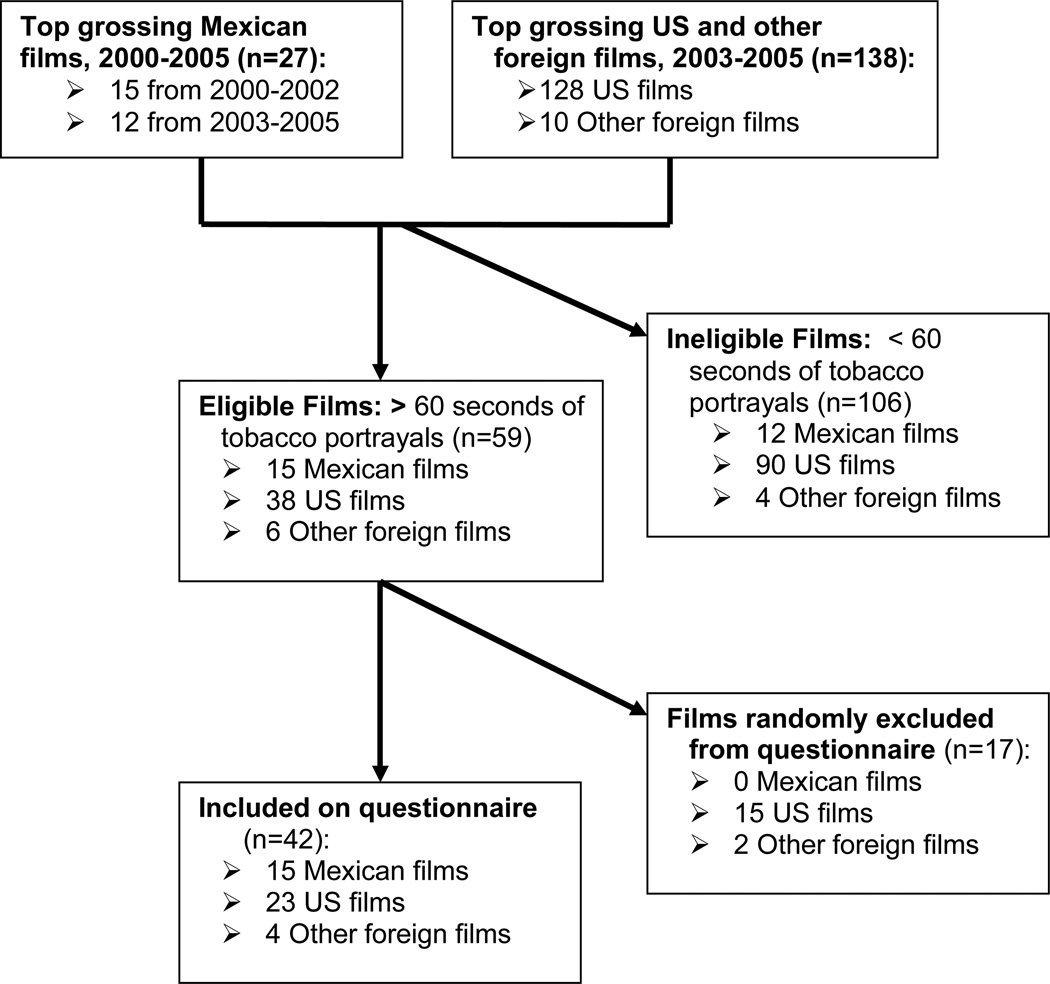

Each baseline survey included the same list of 42 popular films that portrayed tobacco for at least one minute (Figure I). The top 50 grossing films each year from 2003 until 2005 (n=150) and the top 60 grossing films each year from 2000 until 2002 (n=180) were determined using Mexico City box office earnings from the Mexican National Film and Video Industry Chamber. Films eligible for inclusion in our survey came from all 150 films from the 2003 to 2005 period (138 US films; 12 Mexican films; 10 films from other countries) and the 15 Mexican-made films amongst the 160 top films from 2000 until 2002. These 15 Mexican films from the earlier period were included because of their continued popularity, as indicated by their being shown regularly on television and being sold by street vendors at the time of data collection. Also, future analyses aimed to determine whether the impact of imagery differed for Mexican versus US films. For each of these 165 eligible films, we assessed the total seconds of screen time in which tobacco products, tobacco packaging, and smoke known to emanate from lighted tobacco products were portrayed. All tobacco products were assessed in this measure; however, we generally refer to “smoking” exposure because smoking comprises the vast majority of tobacco use in popular films (13). Inter-rater assessments of screen-time smoking in a subset of coded films was high (r=0.99). A fuller discussion of our methodology has been published elsewhere (5).

Figure 1.

Selection of top grossing films for inclusion in questionnaire

We eliminated from consideration films with less than one minute of screen-time smoking (69/165), in order to capture a broader range of exposure than a random selection of films would have allowed. In order to have a sufficient number of Mexican films, all Mexican films with more than a minute of smoking were included in the final list (15/15). However, due to concerns about response burden, we randomly selected approximately 60% of the remaining US (23/38) and other foreign films (4/6). The included films had slightly higher average screen-time exposure to smoking than the eligible but excluded films (4.0 vs. 3.5 minutes, respectively). Two bogus film titles were also included, and a dummy variable was derived to assess and adjust for over-report of seeing either (1) or neither (0) of these films. The total seconds of exposure to smoking portrayals were summed across all films each student reported having seen, and this was converted into minutes of exposure. Total film tobacco exposure was divided into quartiles, with the lowest quartile as the reference group.

Smoking susceptibility and behavior

As is standard practice (14, 15), students were classified as susceptible if they indicated that they would “definitely not” accept a cigarette if a friend offered it to them and “definitely not” smoke in the next year, whereas students who stated otherwise to either question were classified as susceptible. Students who reported having never smoked even a puff of a cigarette at baseline were selected into the analytic sample. Because movie smoking appears to have its strongest impact on smoking onset (9, 16), we studied follow up report of having ever smoked even a puff at as “trying smoking” and having smoked at least once in the previous 30 days as “current smoking.” This measure of current smoking is standard for national surveys of adolescents, such as the annual Centers for Disease Control Youth Risk Behavior survey (17). Progression to more established smoking is rare among nonsmoking youth of this age, but past month smokers have higher nicotine addition and likelihood of progression toward daily smoking than those who have only tried smoking (18, 19).

Control variables

A variety of factors were assessed which could confound the association between exposure to smoking in films and smoking outcomes. Sensation seeking involves seeking and enjoying high sensory experiences (20), including risk behaviors (16, 21, 22) and has been associated with more frequent media exposure (23). The Brief Sensation Seeking Scale-4 (BSSS-4) has good measurement properties in surveys of US (24, 25) and Mexican youth (5, 26) and had good internal consistency in our analytic sample (α=0.80). Responses to these four questions were averaged, with higher scores indicating higher sensation seeking. Tertiles were derived, with the reference group being those with lowest sensation seeking. Low self-esteem also predicts adolescent smoking uptake among US youth (16) and is positively associated with susceptibility to smoking (26) and smoking behavior among Mexican adolescents (5). Related psychological constructs, such as low personal adjustment (27) and contentedness (28), have been associated with higher mass media exposure. Three items (i.e. “I hate how I am;” “I would like to be someone else;” “I feel ashamed of myself”) from the Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory (SEI), which has been validated for Mexican adolescents (29), were used to assess self esteem. These items had good internal consistency in our sample (α=0.86), were averaged together, and their average used to create tertiles, with the reference group being those with highest self esteem.

Social network members who smoke may also promote both adolescent smoking and selective viewing of films that contain smoking. These influences were assessed with three dichotomous variables: any (1) vs. no parent who smoked (0); any (1) vs. no siblings who smoked (0); and best friend smoked (1) or not (0). Assessment of parental rules about smoking involved asking students what their parents would do if they found them smoking, with responses recoded as indicating punishment (0) vs. no punishment (1). To assess perceived legitimacy of parental authority, students were asked whether they thought their parents should tell them what to do about smoking, which has been validated as a correlate of smoking among US youth (30). Students who responded “definitely not”, “probably not”, or “probably yes” were classified as perceiving low parental legitimacy (1) and those who responded “definitely yes” were classified as perceiving high parental legitimacy (0). We also asked whether participants had a TV in their bedroom (1) or not (0), which is a proxy for higher levels of media exposure among US youth (23). Self-reported possession of an object that had a cigarette logo on it was used as an indicator of openness to tobacco industry marketing. Finally, we used private school attendance as an indicator of socioeconomic status, since upper- and middle-class students mostly attend private school.

Analyses

All data analyses were conducted using STATA, version 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, 2004). Chi-square and t-tests were used to assess significant differences between students who were and were not followed up. In further analyses, we adjusted for clustering within schools. Bi-variate relative risk of having tried smoking at follow up, as well as of and current smoking at follow up, were estimated using logistic regression models for each variable under consideration. Logistic regression was also used to estimate adjusted relative risks of experiencing each outcomes, including in multivariate models variables for which a statistically significant bivariate relative risk was found.

RESULTS

Attrition analysis

Table 1 shows the characteristics of adolescents lost to follow up compared with those retained in the analytic sample. Adolescents lost to follow up were significantly older, more likely to be male, to have a parent or best friend who smoked, to report seeing a bogus film, and to have higher exposure to movie smoking at baseline. There was no difference between those lost and retained on exposure to sibling smoking, susceptibility to smoking, sensation seeking, attending private school, having a TV in their bedroom, or possession of something with a tobacco logo.

Table I.

Characteristics of students who were and were not successfully followed

| Characteristics | Followed (n=1741) |

Not followed (n=352) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 11 or 12 years | 22.0% | 17.4% | <0.0001 |

| 13 years | 56.6% | 51.1% | ||

| 14 years | 21.5% | 31.4% | ||

| Male | 46.9% | 54.3% | 0.012 | |

| At least one parent smokes | 33.0% | 41.0% | 0.004 | |

| At least one sibling smokes | 16.6% | 18.5% | 0.402 | |

| Best friend smokes | 11.9% | 17.3% | 0.006 | |

| Susceptibility to smoke | 39.8% | 43.2% | 0.260 | |

| Sensation seeking | 2.37 | 2.41 | 0.521 | |

| Self esteem | 1.84 | 1.94 | 0.085 | |

| Attended private school | 17.7% | 18.4% | 0.749 | |

| TV in bedroom | 72.3% | 72.6% | 0.905 | |

| Own something with cigarette logo | 9.9% | 10.3% | 0.843 | |

| Reported viewing a bogus film | 8.5% | 12.2% | 0.027 | |

| Minutes of film tobacco exposure | 43.8 | 49.0 | 0.019 | |

Main effects analysis

At follow up, 35.8% (n=624) of the sample reported having tried smoking and 8.1% (n=134) reported having smoked in the previous 30 days. Students saw an average of 48.3 minutes of smoking, with the lowest quartile spanning no exposure (n=69) to 17.89 minutes, the second, third and fourth quartiles ranging up to 39.5, 64.3 and 176.9 minutes, respectively. Bi-variate and multivariate adjusted relative risk of baseline factors associated with each smoking outcome are shown in Table 2. In bi-variate analyses, the following variables were significantly associated with increased risk of trying smoking in the year after baseline: older age; having parents, siblings or a best friend who smoked; perceiving low vs. high legitimacy of parental authority over smoking; high vs. low sensation seeking; low vs. high self esteem; possessing something with a tobacco logo; report of having seen a bogus film; and being in the 3rd or 4th highest quartile vs. lowest quartile of movie smoking exposure. In the adjusted model, having a parent, sibling, or best friend who smoked, as well as having high sensation seeking propensity and low self esteem remained statistically significant predictors of trying smoking within the year after baseline. A statistically significant association between film exposure and trying smoking was found when examining the third highest vs. lowest exposure quartiles (ARR3v1=1.54, 95%CI 1.01, 2.64). When comparing the highest vs. the lowest exposure quartiles, this association become non-statistically significant (ARR4v1=1.41, p=0.08).

Table II.

Relative risk of smoking initiation and current smoking at follow up

| Independent Variables | Smoked in last year | Smoked in last 30 days | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate RR (95%CI) |

Multivariate* RR (95%CI) |

Bivariate RR (95%CI) |

Multivariate* RR (95%CI) |

||

| Age | 13 vs. 11 or 12 | 1.37 (0.96, 1.95) |

1.29 (0.82, 2.01) |

1.60 (0.86, 2.98) |

-- |

| 14 vs. 11or 12 | 1.41a (1.03, 1.93) |

1.20 (0.74, 1.95) |

1.38 (0.93, 2.04) |

-- | |

| Male vs. Female | 1.19 (0.93, 1.52) |

-- | 1.60a (1.09, 2.35) |

1.15 (0.76, 1.74) |

|

|

Any parent smoke (1) vs. no parents who smoke (0) |

1.56d (1.28, 1.90) |

1.52b (1.18, 1.95) |

1.95d (1.52, 2.51) |

1.78b (1.26, 2.53) |

|

|

Any sibling smokes (1) vs. no sibling smokes (0) |

1.73d (1.34, 2.23) |

1.49b (1.14, 1.95) |

1.86b (1.24, 2.80) |

1.32 (0.83, 2.10) |

|

|

Best friend smokes (1) vs. does not smoke (0) |

2.04b (1.33, 3.12) |

1.95b (1.28, 2.98) |

2.85c (1.60, 5.06) |

2.32a (1.05, 5.12) |

|

|

Parent would not (1) vs. would (0) punish for smoking |

0.99 (0.75, 1.29) |

-- | 0.80 (0.45, 1.42) |

-- | |

|

Parental authority not legitimate (1) vs. legitimate (0) |

1.22a (1.01, 1.46) |

1.11 (0.92, 1.35) |

1.30 (0.98, 1.74) |

-- | |

|

Sensation seeking |

Mid vs Low | 1.19 (0.91, 1.55) |

0.99 (0.76, 1.29) |

1.03 (0.67, 1.56) |

0.94 (0.58, 1.50) |

| High vs Low | 2.20d (1.67, 2.89) |

1.50a (1.10, 2.04) |

2.24c (1.48, 3.40) |

1.45 (0.82, 2.55) |

|

|

Self- esteem |

Mid vs High | 1.14 (0.91, 1.42) |

1.13 (0.93, 1.38) |

0.95 (0.61, 1.46) |

0.82 (0.50, 1.33) |

| Low vs High | 1.68d (1.34, 2.11) |

1.34a (1.00, 1.79) |

2.10b (1.38, 3.18) |

1.43 (0.78, 2.60) |

|

| Private vs. public school | 1.09 (0.84, 1.42) |

-- | 0.72 (0.38, 1.37) |

-- | |

|

TV in bedroom vs. no TV in bedroom |

1.12 (0.86, 1.45) |

-- | 1.58 (0.97, 2.57) |

-- | |

|

Own something with a tobacco logo |

1.84b (1.27, 2.68) |

1.58 (0.90, 2.76) |

1.99a (1.12, 3.54) |

1.43 (0.66, 3.11) |

|

|

Reported seeing bogus film vs. not seen |

1.79b (1.24, 2.57) |

1.26 (0.70, 2.28) |

3.61d (2.30, 5.68) |

2.45a (1.19, 5.03) |

|

|

Quartiles of film smoking exposure |

2nd vs 1st | 1.19 (0.84, 1.69) |

1.01 (0.64, 1.60) |

1.20 (0.64, 2.25) |

1.22 (0.59, 2.51) |

| 3rd vs 1st | 1.79d (1.35, 2.37) |

1.54a (1.01, 2.64) |

2.59b (1.40, 4.80) |

2.44b (1.31, 4.55) |

|

| 4th vs 1st | 1.96c (1.41, 2.72) |

1.41 (0.95, 2.10) |

3.71d (2.04, 6.73) |

2.23a (1.19, 4.17) |

|

=p<0.05;

=p<0.01;

=p<0.001;

=p<0.0001

model includes all variables for which estimates are included in the table

Most of the same variables that had statistically significant, bi-variate relative risks associated with trying smoking were also associated with current smoking. In particular, having a parent, sibling or best friend who smoked, high sensation seeking, low self-esteem, possessing tobacco paraphernalia, reporting having seen a bogus film and being amongst the two highest quartiles of movie smoking exposure were all associated with relative risk of current smoking at one year follow up. In contrast to the bi-variate relative risk of trying smoking for the first time, lower perceived legitimacy of parental authority over smoking was unassociated with current smoking and males were more likely than females to become a current smoker. In the multivariate model, having a parent or best friend who smoked, reporting having viewed a bogus film, and being in the 3rd or 4th highest quartiles of movie smoking exposure (ARR=2.44 and 2.23, respectively) were independent predictors of current smoking behavior.

DISCUSSION

Results from the current study suggest that film smoking exposure predicts current smoking but has only a marginal influence on trying smoking at follow up. The highest level of movie smoking exposure was not significantly associated with increased risk of trying smoking; however, the point estimate (ARR4v1=1.41) was similar to that found for the statistically significant risk associated with the third highest exposure level (ARR 3v1=1.54), suggesting that there may be a threshold effect. Longitudinal studies in Germany (9) and the US (16) found a stronger predictive, dose-response relationship between movie smoking exposure and trying smoking for the first time; however, this relationship was weaker in Germany than the US. Researchers hypothesized that this may be due to weaker tobacco regulation and a resulting greater range of social and marketing influences to smoke among German youth. The more permissive tobacco control environment in Mexico (31) may similarly account for the fact that movie smoking had a weaker influence over trying smoking. At the time of data collection in Mexico, youth smoking was on the rise (12), attitudes about smoking were generally permissive (32, 33), single cigarrette sales were prevalent and allowed easy youth access (34, 35), and there were few marketing restrictions on the tobacco industry (31). Indeed, the incidence of trying smoking in our sample over the one-year follow up period was much higher (36%) than the one- to two-year incidence for similarly aged adolescents in studies conducted in Germany (19%), and much higher than among US adolescents studied (10%). The findings from these three studies suggest that as the tobacco control environment strengthens and smoking incidence decreases, movies may become more important as a social influence to smoke. The role of other pro-tobacco messages and cues in Mexico may also account for why the influence of exposure appeared to have a threshold effect, with little difference in the increased risk associated with the third and fourth highest levels of exposure.

Another difference between this study and previous longitudinal studies mentioned above is that the present study found stronger movie effects for progression to a more advanced stage of smoking (30 day smoking) than it did for having tried smoking in the previous year. In countries like Mexico, movie images of smoking may play a bigger role in helping the experimental smoker define him or herself as a smoker. The dominance of the US film industry in Mexico, as well as the market dominance of US cigarette brands there (36), may mean that some youth use smoking to symbolize their affiliation with US culture, as has been found for Thai youth (11).

Previous work among U.S. (37) and German (38) adolescents suggested that movie influences predominate over tobacco marketing influences in promoting trying smoking, while the reverse is true for the transition between onset and established smoking. Our data suggest that the effect of tobacco marketing, at least as measured by possession of a tobacco promotional item, does not have an independent influence on either transition. However, this measure only picks up a small range of tobacco marketing exposure and should be include a fuller range of marketing influences in future analyses on this topic.

Our research involved a different method for determining film smoking exposure than has been used in other studies. For example, youth have reported their favorite movie stars, with the smoking status of these stars used to determine film influence on smoking (39). Other studies have randomly selected popular films for each students’ survey and quantified exposure to the number of occurrences of tobacco use in films seen (2, 9). A random selection of movies for each survey allows for an unbiased estimate of overall exposure (40), but may be impractical for studies in lower-income countries that have fewer resources. Our approach involved determining total screen time of exposure to smoking imagery, which while correlated with the frequency of tobacco use occurrences, also accounts for the range of screen time exposures that takes place within any particular occurrence. We assume that our fixed list of movies that each contained a minute or more of tobacco imagery provides a reasonable estimate of overall exposure to smoking in films. This selection may explain the threshold exposure effects that we found, and excluded films may provide important contributions to exposure that bias results in unpredictable ways. Our particular list of movies may be confounded with other factors that explain smoking, such as seeking out movies with adult-rated themes. Nevertheless, our analyses adjusted for personality and social factors that might drive youth to view such movies. Furthermore, the fact that our results are relatively consistent with other studies, in spite of our different exposure assessment method, suggests that the association found here is robust and may extend to other youth in other middle-income countries.

Despite the strengths of this longitudinal study, there are some limitations. One year of follow up in this study and at this young age was not enough time to assess the relation between movie exposure and established adolescent smoking. Although some current smokers in our study may never try smoking again, having smoked in the last 30 days confers greater risk of progression to smoke than having tried smoking beyond a month ago (18, 19). Furthermore, we only assessed movie smoking exposure before baseline, not after. Although we missed exposures that took place between survey waves, lagged exposure has been shown to have similar influences on smoking uptake as more recent exposure (8). This lagged exposure assessment method also addressed concerns about reverse causality (i.e., adolescents who had tried smoking in the interval may have subsequently been drawn to movies that contain smoking), which we also addressed by limiting our baseline sample to never smokers. This design is in line with theories of media socialization effects (41) that suggest that cumulative exposure to movie smoking is a more important influence on smoking than particular exposures close to the onset of smoking. Nevertheless, our baseline assessment of movie smoking exposure could be criticized for including films that were released as many as five years prior to baseline data collection. This was done because studies of U.S. adolescents have shown that they see many older movies on DVD, and we did not want to miss these exposures. We expect that Mexican adolescents, like their US counterparts (42), are less likely to see movies in the theater than on DVDs after their release – which the black market makes very accessible and affordable ($1 USD per DVD) in Mexico. Studies with longer follow-up times and with repeated assessments of exposure are needed to confirm whether film smoking exposure accounts for further progression toward established smoking among Mexican adolescents, as has been found for US adolescents (42, 43).

There is always the possibility that an unmeasured third variable confounds our results. Our analyses controlled for expectations around parental punishment for smoking and perceived legitimacy of parental authority over smoking, which had not been treated as covariates in other studies; however, we did not address other parenting practices that could confound the association between exposure to media with smoking content and smoking. Nevertheless, among US adolescents, similar dose-response curves relate film smoking exposure and smoking initiation across adolescents exposed to distinct parenting styles (44). Research on such parenting practices and their relationship to media consumption should aim to assess whether these practices differentially impact Latino youth, as has been found for some ethnic groups of youth (7). We also limited our sample to those who had not tried smoking at baseline, thereby eliminating from the analyses youth who were more likely to progress to established smoking. Some studies have found that films have a weaker influence on higher-risk kids, such as those who have parents who smoke (9, 16), and this possibility should be explored for Mexican youth. Finally, our data came from a convenience sample in two Mexican cities, and hence, the results may not apply to other Mexican adolescents. Nevertheless, the study sample was selected from a set of randomly selected schools that have been used to estimate the prevalence of adolescent tobacco use and risk factors in Mexico (12).

Despite these limitations, our results are consistent with other studies that indicate that exposure to portrayals of smoking in films promotes adolescent smoking. Although our results suggest that the strength of this association may vary by strength of tobacco control environment, the existence of an influence appears independent of this environment or of the socio-cultural context. Policymakers should consider policies to reduce youth exposure to smoking portrayals in film and other mass media. One key policy strategy includes assigning an adult rating to films with tobacco content (45). The World Health Organization (WHO) supports this policy, which could be considered for incorporation into the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO-FCTC). Indeed, the WHO-FCTC promotes a coordinated international response to address the challenges posed by the growing epidemic of tobacco use in low- and middle-income countries while the global tobacco industry foments this epidemic while expanding into new markets. Since rating boards differ across each country, if this strategy is implemented in one country, it does not guarantee that a film with tobacco will be similarly rated in another country to which it is distributed. As the Conference of the Parties to the WHO-FCTC develops amendments to address emerging issues, including direct and indirect transnational advertising, film ratings should be included as part of that discussion.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded as part of a larger project supported by the Mexican National Council on Science and Technology (Convocatoria Salud-2003-C01-78), with additional funding provided by the Initiative for Cardiovascular Research in Developing Countries. Content analysis of U.S. films was supported by the US National Cancer Institute (CA 77026) and a grant from the American Legacy Foundation. The coding on some US films and all Mexican and other foreign films was supported by the University of Illinois at Chicago, Cancer Center, Cancer Education and Career Development Program (RA25-CA57699), which was funded by the US National Cancer Institute.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. The role of media in promoting tobacco use, NIH Pub. No. 07-6242. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2008. National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sargent JD, Beach ML, Adachi-Mejia AM, et al. Exposure to movie smoking: Its relations to smoking initiation among US adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1183–1191. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD. Exposure to smoking in popular contemporary movies and youth smoking in Germany. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32(6):466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song A, Ling P, Neilands T, Glantz S. Smoking in movies and increased smoking among young adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thrasher JF, Jackson C, Arillo-Santillan E, Sargent JD. Exposure to smoking imagery in popular films and adolescent smoking in Mexico. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;35:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wills T, Sargent JD, Stoolmiller M, Gibbons F, Gerrard M. Movie smoking exposure and smoking onset: A longitudinal study of mediation processes in a representative sample of U.S. adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behavior. 2008;22:269–277. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson C, Brown JD, L'Engle KL. R-rated movies, bedroom televisions, and initiation of smoking by white and black adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:260–268. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Titus-Ernstoff L, Dalton MA, Adachi-Mejia A, Longacre M, Beach M. Longitudinal study of viewing smoking in movies and initiation of smoking by children. Pediatrics. 2008;121:15–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD. Exposure to smoking in internationally distributed American movies and youth smoking in germany: A Cross-cultural Cohort Study. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e108–e117. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sargent JD, Dalton MA, Beach ML, et al. Viewing tobacco use in movies: Does it shape attitudes that mediate adolescent smoking? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00434-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg M, Baumgartner H. Cross-country attraction as a motivation for product consumption. Journal of Business Research. 2002;55:901–906. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valdés-Salgado R, Thrasher JF, Sánchez-Zamorano LM, et al. Los retos del Convenio Marco para el Control del Tabaco en México: Un diagnostico a partir de la Encuesta sobre Tabaquismo en Jóvenes [Challenges for the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in Mexico: A diagnosis using the Global Youth Tobacco Survey] Salud Pública de México. 2006;48:S5–S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalton MA, Tickle JJ, Sargent JD, Beach ML, Ahrens BM, Heatherton TF. The incidence and context of tobacco use in popular movies from 1988–1997. Preventive Medicine. 2002;34:516–523. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Merritt RK. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychology. 1996;15:355–361. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.5.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson C, Dickinson D. Cigarette consumption during childhood and persistence of smoking through adolescence. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:1–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.11.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalton M, Sargent J, Beach M, et al. Effect of viewing smoking in movies on adolescent smoking initiation: A cohort study. Lancet. 2003;362:281–285. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brener ND, Kann L, Kinchen SA, et al. Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004;53:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Loughlin J, DiFranza J, Tyndale RF, et al. Nicotine-dependence symptoms are associated with smoking frequency in adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;25:219–225. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi WS, Pierce JP, Gilpin EA, Farkas A, Berry C. Which adolescent experimenters progress to established smoking in the United States. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1997;13:385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuckerman M. Sensation Seeking: Beyond the Optimal Level of Arousal. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skara S, Sussman S, Dent CW. Predicting regular cigarette use among continuation high school students. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2001;25:147–156. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.25.2.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thrasher JF, Niederdeppe J, Jackson C, Farrelly MC. Using anti-tobacco industry messages to prevent smoking among high-risk youth. Health Education Research. 2006;21:325–337. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts DF, Foehr UG, Rideout V. Generation M: Media in the lives of 8–18-year-olds: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hornik R, Maklan D, Orwin R, et al. Evaluation of the national youth anti-drug media campaign: Third semi-annual report of findings. Washington, DC: National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stephenson MT. Mass media strategies targeting high sensation seekers: What works and why. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27:s233–s238. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.1.s3.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arillo-Santillán E, Thrasher JF, Rodríguez-Bolaños R, Chávez-Ayala R, Silvia RV, Lazcano-Ponce E. Susceptibilidad al consumo de tabaco en estudiantes no fumadores de 10 ciudades mexicanas: Una necesidad de cultura contra permisividad social del tabaquismo. Salud Pública de México. 2007;49:S170–S181. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Comstock G. Television and the American child. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts DF, Foehr UG. Kids and media in America. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verduzco M, Lara-CantúM, Acevedo M, Cortés J. Validación del Inventario de Autoestima de Coopersmith para niños mexicanos. Revista Intercontinental de Psicología y Educación. 1994;7:55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson C. Perceived legitimacy of parental authority and tobacco and alcohol use during early adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:425–432. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00398-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thrasher JF, Reynales-Shigematsu L, Baezconde-Garbanati L, et al. Promoting the effective translation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: A case study of challenges and opportunities for strategic communications in Mexico. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2008;31:145–166. doi: 10.1177/0163278708315921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thrasher JF, Bentley ME. The meanings and context of smoking among Mexican university students. Public Health Reports. 2006;121:578–585. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thrasher JF, Boado M, Sebrié EM, Bianco E. Smoke-free policies and the social acceptability of smoking in Uruguay and Mexico: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation (ITC) Project. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11(6):591–599. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thrasher J, Villalobos V, Dorantes-Alonso A, Arillo-Santillán E, Cummings KM, O'Connor R, Fong G. Does the availability of single cigarettes promote or inhibit cigarette consumption?: Perceptions, prevalence and correlates of single cigarette use among adult Mexican smokers. Tobacco Control doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.029132. , In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuri-Morales PA, Cortes-Ramirez M, Cravioto-Quintana P. [Prevalence and risk factors related to sale of cigarettes to minors in stores in Mexico City] Salud Pública de México. 2005;47:402–412. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342005000600004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saenz de Miera B, Thrasher JF, Chaloupka FJ, Watters H, Fong GT, Hernández-Avila M. Self-reported price, consumption and brand switching of cigarettes in a cohort of Mexican smokers before and after a cigarette tax increase. Under review. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.032177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sargent JD, Gibson J, Heatherton TF. Comparing the effects of entertainment media and tobacco marketing on youth smoking. Tobacco Control. 2009;18:47–53. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.026153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sargent JD, Hanewinkel R. Comparing the effects of entertainment media and tobacco marketing on youth smoking in Germany. Addiction. 2009;104:815–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Distefan JM, Pierce JP, Gilpin EA. Do favorite movie stars influence adolescent smoking initiation? American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1239–1244. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sargent J, Tanski S, Gibson J. Exposure to movie smoking among US adolescents aged 10 to 14 years: a population estimate. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1167–e1176. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McQuail D. McQuail's mass communication theory. London: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sargent J, Stoolmiller M, Worth K, Dal Cin S, Wills T, Gibbons F. Exposure to smoking depictions in movies: Its association with established adolescent smoking. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:849–856. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.9.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dalton M, Beach M, Adachi-Mejia A, et al. Early exposure to movie smoking predicts established smoking by older teens and young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e551–e558. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sargent JD. Smoking in movies: Impact on adolescent smoking. Adolescent Medicine. 2005;16:345–370. doi: 10.1016/j.admecli.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.WHO. Smoke-free Movies: From evidence to action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]