Abstract

Siderophore-mediated iron handling is crucial for the virulence of Aspergillus fumigatus. Here we identified a new component of its siderophore metabolism, termed SidJ, which is encoded by AFUA_3G03390. The encoding gene is localized in a siderophore biosynthetic gene cluster that is conserved in a variety of fungi. During iron starvation, SidJ deficiency resulted in decreased growth and increased intracellular accumulation of hydrolysis products of the siderophore fusarinine C. The implied role in siderophore hydrolysis is consistent with a putative esterase domain in SidJ, which now represents the first functionally characterized member of the DUF1749 (domain of unknown function) protein family, with members found exclusively in fungi and plants.

TEXT

The bioavailability of the essential nutrient iron is low, and therefore fungi have evolved various iron acquisition mechanisms, including siderophore-mediated iron uptake (1–3). The opportunistic fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus produces four types of low-molecular-mass iron chelators, termed siderophores; it secretes fusarinine C (FSC) and triacetylfusarinine C (TAFC) for iron uptake and accumulates ferricrocin (FC) for hyphal iron distribution and storage and hydroxyferricrocin (HFC) for conidial iron distribution and storage (4, 5). FSC consists of three N5-anhydromevalonyl-N5-hydroxyornithine residues, termed fusarinine (FS), which is cyclically linked by ester bonds. TAFC is the N2-acetylated FSC. FC is a cyclic hexapeptide with the structure Gly-Ser-Gly-(N5-acetyl-N5-hydroxyornithine)3, and HFC is the hydroxylated FC (1). Both extra- and intracellular siderophores have been shown to be crucial for the virulence of A. fumigatus (4, 6). Subsequent to chelation of iron and uptake, FSC and TAFC are hydrolyzed and the iron is transferred to the metabolism or to the intracellular siderophore FC for transport and storage of iron (7, 8). The esterase EstB was shown to be involved in the hydrolysis of TAFC, but not FSC, and consequently in the transfer of iron from TAFC to the metabolism and FC (8). In contrast, intracellular processing of FSC has remained enigmatic so far. Here we report the characterization of the FSC esterase SidJ.

Under iron-sufficient conditions, siderophore production is repressed in A. fumigatus by the GATA transcription factor SreA (9). Genome-wide transcriptional profiling identified 49 SreA target genes, of which 13 have so far experimentally been proven to be involved in mechanisms for adaptation to iron starvation, such as reductive iron assimilation, siderophore metabolism, and iron regulation (10). Most of these genes are organized in gene clusters. The gene cluster encoding SidD (FSC nonribosomal peptide synthetase), SidF (hydroxyornithine transacylase), and SidH (mevalonyl-coenzyme A [CoA] hydratase), which are all essential for the biosynthesis of FSC and TAFC, also contains the so far uncharacterized gene AFUA_3G03390 (10) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The deduced protein, termed SidJ, consists of 354 amino acid residues. Sequence similarity analysis (blastp; http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) revealed that SidJ is highly conserved in numerous fungal species and belongs to the DUF1749 (domain of unknown function) protein family, with members found in fungi and plants. Notably, genes with high sequence similarity (E value < e−120; see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) are also flanked by putative siderophore biosynthetic genes in other fungal species, e.g., all Aspergillus species with available genome sequences, Penicillium chrysogenum, Geomyces destructans, Trichoderma reesei, and Botryotinia fuckeliana (http://www.aspergillusgenome.org/; data not shown), underlining a putative function in siderophore metabolism.

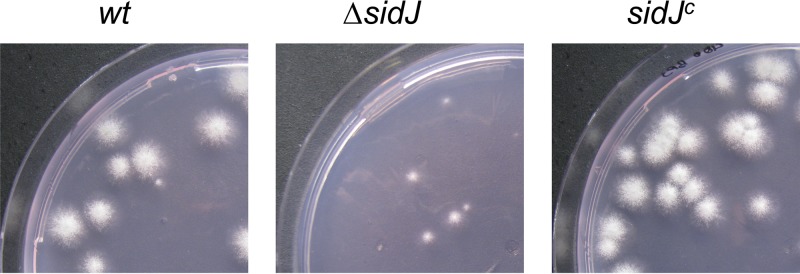

In order to characterize the function of SidJ, the encoding region was replaced by the hygromycin B resistance marker gene in A. fumigatus ATCC 46645 (wild type [wt]) as described in Fig. S2A in the supplemental material. Complementation of the ΔsidJ strain with a functional sidJ gene (sidJc strain; see Fig. S2B) cured all ΔsidJ defects described below (Fig. 1 and data not shown), which proves that the ΔsidJ strain-specific phenotypic changes are a direct result of the loss of sidJ. Comparison of the growth rates of colonies originating from single conidia showed no difference between the wt, ΔsidJ, and sidJc strains under iron sufficiency (Table 1). However, the radial growth of the ΔsidJ strain was decreased by 16% during iron starvation and 40% in the presence of 200 μM bathophenanthroline disulfonic acid (BPS) in comparison to the growth of wt and sidJc strains (Table 1). Moreover, 400 μM BPS inhibited almost completely the growth of the ΔsidJ strain but not that of the wt or sidJc strain (Fig. 1). Notably, the ferrous iron-specific chelator BPS inhibits reductive iron assimilation and renders the siderophore system the only functional high-affinity iron uptake system in A. fumigatus (6). Interestingly, these differences were less dramatic when growth was measured with colonies arising from 103 conidia, as is usually used in radial growth assays (data not shown). The ΔsidJ conidia showed wt-like germination efficiency under iron-sufficient conditions (30 μM FeSO4) as well as in the presence of 200 μM BPS (data not shown). Together with the finding that FSC is produced mainly by young cultures (11, 12), these data indicate that FSC and its hydrolysis are particularly crucial during initial hyphal elongation. Spot inoculation of 103 conidia most likely masks this ΔsidJ defect by mutual growth support of the large number of germinating conidia. At later time points, TAFC metabolism then probably compensates for the defect in FSC metabolism. Taken together, these data demonstrate that the function of SidJ is limited to iron starvation conditions, as previously indicated by the iron repression of sidJ expression (10) (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material), and furthermore suggest the involvement of SidJ in siderophore-mediated iron acquisition.

Fig 1.

SidJ deficiency results in decreased growth in the presence of 400 μM BPS. Representative pictures of colonies arising from single conidia were taken after growth for 48 h at 37°C.

Table 1.

SidJ deficiency decreases radial growth during iron starvation but not iron sufficiencya

| Medium | Colony diam (mm) (mean ± SD)b |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| wt | ΔsidJ strain | sidJc strain | |

| +Fe | 10.8 ± 0.5 | 11.2 ± 0.6 | 10.3 ± 0.5 |

| −Fe | 12.2 ± 1.3 | 10.2 ± 1.3* | 12.4 ± 1.4 |

| BPS | 12.3 ± 0.8 | 7.4 ± 1.1* | 13.3 ± 1.3 |

Radial growth (colony diameter in mm) of colonies raised from single conidia was measured on minimal medium with 30 μM FeSO4 (+Fe) or without iron (−Fe) after incubation for 48 h as well as without iron plus 200 μM BPS (BPS) after incubation for 72 h.

The data are mean values ± standard deviation for 10 colonies. *, significantly different from results for wt by the t test (P < 0.05).

Quantification of the production of extracellular TAFC and FSC as well as intracellular FC in 24-h iron-limited liquid cultures, performed as described previously (4), did not reveal any significant differences between wt, ΔsidJ, and sidJc strains (data not shown). These data rule out a major role of SidJ in siderophore biosynthesis.

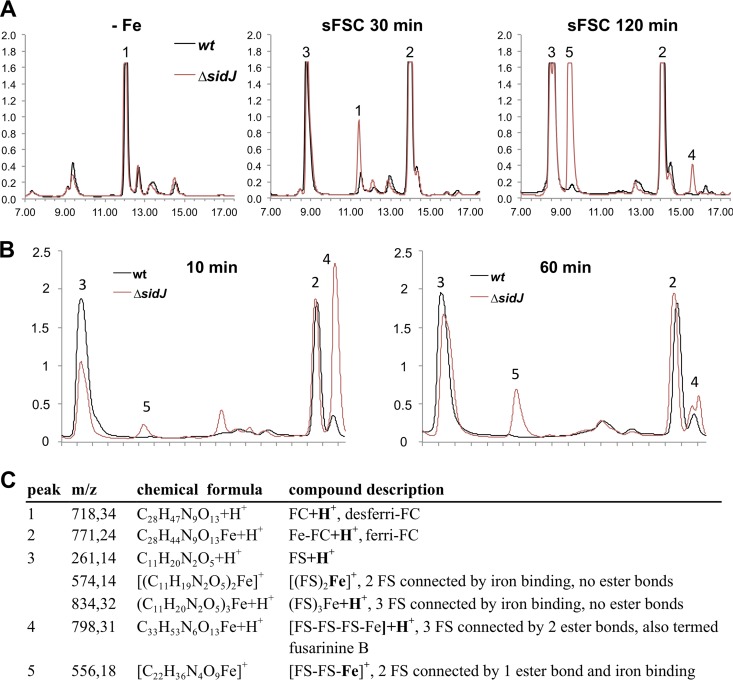

In order to study a potential role of SidJ in the intracellular processing of siderophore-iron complexes subsequent to their uptake in vivo, A. fumigatus wt, ΔsidJ, and sidJc strains were grown for 22 h at 37°C in iron-limited liquid minimal medium. Subsequently, mycelia were washed and transferred to fresh minimal medium containing 30 μM ferri-FSC or 30 μM ferri-TAFC and incubated for another 30 min or 120 min. The intracellular accumulation of siderophores was analyzed before and after the shift by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Fig. 2A) combined with mass spectrometric identification of detected compounds (Fig. 2C), as described previously (7). Such an experimental setup previously provided the in vivo proof for the involvement of EstB in the hydrolysis of ferri-TAFC in A. fumigatus, because the mutant deficient in the esterase EstB showed increased cellular accumulation of TAFC degradation products concomitant with decreased transfer of iron to FC (8). Under iron-limited conditions, the major siderophore detected was desferri-FC, with similar amounts in all three strains (Fig. 2, peak 1). After the addition of ferri-FSC, the desferri-FC was converted to ferri-FC (peak 2), which was already visible after 30 min. Moreover, various FSC degradation products accumulated at 120 min; these included FS and FS-iron complexes (peak 3), ferri-fusarinine B derived from FSC by the hydrolysis of one ester bond (peak 4), and a ferri-FS dimer derived from FSC by the hydrolysis of two ester bonds (peak 5). The ΔsidJ strain displayed a decreased iron transfer from ferri-FSC to FC at 30 min that is in perfect agreement with the increased cellular accumulation with ferric FSC degradation products at 120 min, namely, ferri-fusarinine B and the ferri-FS dimer (Fig. 2, peaks 1, 4, and 5). This pattern was consistently seen in three different experiments (data not shown). Determination of the siderophore contents of the culture supernatants of wt, ΔsidJ, and sidJc strains at the end of the shift periods indicated similar uptake rates for both siderophores in all three strains (data not shown). Consequently, these data suggest that SidJ is involved in the hydrolysis of ferri-FSC to optimize iron transfer to FC and metabolism. In line, SidJ deficiency resulted in decreased ferri-FSC hydrolytic activity of the A. fumigatus cell extract, i.e., the mutant displayed increased accumulation of FSC hydrolysis products, mainly ferri-fusarinine B (peak 4) after 10 min of incubation and the ferri-FS dimer (peak 5) (Fig. 2B). Nevertheless, both the in vivo and in vitro results also indicated that A. fumigatus is able to hydrolyze FSC into the very same degradation products independently of SidJ, although with less efficiency.

Fig 2.

SidJ deficiency increases the accumulation of FSC and its degradation products and decreases the transfer rate of iron to desferri-FC. (A) Representative reversed-phase HPLC analysis of the intracellular siderophore content of wt (shown in black) and ΔsidJ (shown in red) strains. A. fumigatus wt, ΔsidJ, and sidJc strains were grown for 22 h at 37°C in iron-limited liquid minimal medium (−Fe). Subsequently, mycelia were washed and transferred to fresh minimal medium containing 30 μM ferri-FSC and incubated for another 30 min or 120 min (sFSC 30 min and 120 min, respectively). The absorption at 210 nm is given in milliabsorption units (y axis), and the retention time is given in minutes (x axes). The intracellular siderophore content of the sidJc strain was wt-like and is therefore not shown. (B) Representative reversed-phase HPLC analysis of ferri-FSC incubated with cellular extracts of wt (shown in black) or ΔsidJ (shown in red) strains. Cellular extracts prepared from 30 mg iron-starved, freeze-dried mycelia were incubated with 1.0 mM ferri-FSC in 0.1 M Na phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, in a total volume of 0.7 ml at 37°C for 10 min or 60 min. (C) Mass spectrometry analysis of compound peaks 1 to 5 from panels A and B. The additional ionizing atoms are shown in bold, and the ionizing iron is connected to the molecules with two single bonds. The structures of these compounds are shown in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material.

The role of SidJ in the hydrolysis of the ester bonds of ferri-FSC is perfectly consistent with the fact that a computational protein pattern scan (http://prosite.expasy.org/) revealed that amino acid residues 116 to 125, IVLMGHSTGS, perfectly match the consensus motif for a putative lipase/esterase domain with serine as the active site (prosite domain PS00120), [LIV]-{KG}-[LIVFY]-[LIVMST]-G-[HYWV]-S-{YAG}-G-[GSTAC], which is conserved in fungal SidJ orthologs (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) and plant DUF1749 protein family members (see Fig. S5). However, it is not clear whether all DUF1749 members have the same substrate specificity.

When the same experimental setup was used, the ΔsidJ strain displayed wt-like degradation of ferri-TAFC (data not shown). Previously EstB was shown to hydrolyze exclusively ferri-TAFC, not ferri-FSC (8). Taken together, these data suggest high specificity of the enzymes involved in siderophore degradation. Moreover, SidJ represents the first functionally characterized member of the DUF1749 (domain of unknown function) protein family with members found in fungi and plants.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Austrian Science Foundation grant FWF P21643-B11 (to H.H.) and the Medizinische Forschungsförderung Innsbruck (MUI START 2010012025 to M.S.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 September 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01285-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haas H, Eisendle M, Turgeon BG. 2008. Siderophores in fungal physiology and virulence. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 46:149–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan CD, Kaplan J. 2009. Iron acquisition and transcriptional regulation. Chem. Rev. 109:4536–4552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Philpott CC. 2006. Iron uptake in fungi: a system for every source. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763:636–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schrettl M, Bignell E, Kragl C, Sabiha Y, Loss O, Eisendle M, Wallner A, Arst HN, Jr, Haynes K, Haas H. 2007. Distinct roles for intra- and extracellular siderophores during Aspergillus fumigatus infection. PLoS Pathog. 3:e128. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallner A, Blatzer M, Schrettl M, Sarg B, Lindner H, Haas H. 2009. Ferricrocin, a siderophore involved in intra- and transcellular iron distribution in Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:4194–4196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schrettl M, Bignell E, Kragl C, Joechl C, Rogers T, Arst HN, Jr, Haynes K, Haas H. 2004. Siderophore biosynthesis but not reductive iron assimilation is essential for Aspergillus fumigatus virulence. J. Exp. Med. 200:1213–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gsaller F, Eisendle M, Lechner BE, Schrettl M, Lindner H, Muller D, Geley S, Haas H. 2012. The interplay between vacuolar and siderophore-mediated iron storage in Aspergillus fumigatus. Metallomics 4:1262–1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kragl C, Schrettl M, Abt B, Sarg B, Lindner H, Haas H. 2007. EstB-mediated hydrolysis of the siderophore triacetylfusarinine C optimizes iron uptake of Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot. Cell 6:1278–1285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haas H. 2012. Iron - a key nexus in the virulence of Aspergillus fumigatus. Front. Microbiol. 3:28. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schrettl M, Kim HS, Eisendle M, Kragl C, Nierman WC, Heinekamp T, Werner ER, Jacobsen I, Illmer P, Yi H, Brakhage AA, Haas H. 2008. SreA-mediated iron regulation in Aspergillus fumigatus. Mol. Microbiol. 70:27–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charlang G, Horowitz RM, Lowy PH, Ng B, Poling SM, Horowitz NH. 1982. Extracellular siderophores of rapidly growing Aspergillus nidulans and Penicillium chrysogenum. J. Bacteriol. 150:785–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oberegger H, Schoeser M, Zadra I, Abt B, Haas H. 2001. SREA is involved in regulation of siderophore biosynthesis, utilization and uptake in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 41:1077–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.