Abstract

Achromobacter xylosoxidans is an aerobic nonfermentative Gram-negative rod considered an important emerging pathogen among cystic fibrosis (CF) patients worldwide and among immunocompromised patients. This increased prevalence remains unexplained, and to date no environmental reservoir has been identified. The aim of this study was to identify potential reservoirs of A. xylosoxidans in hospital, domestic, and outdoor environments and to compare the isolates with clinical ones. From 2011 to 2012, 339 samples were collected in Dijon's university hospital, in healthy volunteers' homes in the Dijon area, and in the outdoor environment in Burgundy (soil, water, mud, and plants). We designed a protocol to detect A. xylosoxidans in environmental samples based on a selective medium: MCXVAA (MacConkey agar supplemented with xylose, vancomycin, aztreonam, and amphotericin B). Susceptibility testing, genotypic analysis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and blaOXA-114 sequencing were performed on the isolates. A total of 50 strains of A. xylosoxidans were detected in hospital (33 isolates), domestic (9 isolates), and outdoor (8 isolates) samples, mainly in hand washing sinks, showers, and water. Most of them were resistant to ciprofloxacin (49 strains). Genotypic analysis and blaOXA-114 sequencing revealed a wide diversity among the isolates, with 35 pulsotypes and 18 variants of oxacillinases. Interestingly, 10 isolates from hospital environment were clonally related to clinical isolates previously recovered from hospitalized patients, and one domestic isolate was identical to one recovered from a CF patient. These results indicate that A. xylosoxidans is commonly distributed in various environments and therefore that CF patients or immunocompromised patients are surrounded by these reservoirs.

INTRODUCTION

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disorder which affects different organs, including the respiratory system. The presence of abnormal mucus predisposes patients to chronic airway infections. Over the last 2 decades, new emerging bacteria have been found to invade the airways of CF patients, including nontuberculous mycobacteria, Burkholderia cepacia complex, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, and Achromobacter xylosoxidans. Most of them are multidrug-resistant organisms thought to have been selected by intense antibiotic use over many years (1–4).

A. xylosoxidans is a Gram-negative, aerobic, and oxidase-positive bacillus, often misidentified as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (5, 6). It is an opportunistic pathogen that can cause a wide variety of infections in immunocompromised patients (7–10) but is mainly recovered from CF patients' airways. As previously reported, this species is innately resistant to cephalothin, cefoxitin, cefotaxime, aztreonam, and aminoglycosides (11, 12). Acquired resistance to carbapenems, ceftazidime, and ciprofloxacin is frequent, dramatically limiting therapeutic choices (13, 14).

The prevalence of infection or colonization is variable among CF centers, and cases of cross-contamination have been reported (1, 2, 14–16). In France, analysis of the global data from all the centers visited by CF patients revealed an increase in the isolation of A. xylosoxidans in recent years, with a rate rising from 2.7% in 2001 to 5.3% in 2011 (http://www.vaincrelamuco.org/e_upload/div/registre_francais_mucoviscidose_2011_15.03.13.pdf). In a recent study, we reported the first epidemiological data about A. xylosoxidans in a French CF center (Dijon, Burgundy), with a prevalence of 13.9% among the 120 patients (13). This percentage is, surprisingly, much higher than the one reported in the French global data and does not result from cross-contamination between the patients. Moreover, we observed an increase in the rate of isolation of A. xylosoxidans in hospitalized patients, mainly in intensive care units and hematology wards. This unusually high frequency of A. xylosoxidans isolation prompted us to look for specific environmental sources of contamination in the area.

To date, in hospitals, A. xylosoxidans has been involved in many procedure-related infections, being associated for instance with contaminated disinfectants (17), dialysis fluids (7), and ultrasound gel (18). There are a few reports of A. xylosoxidans being found in outdoor environments, including in some plants (19, 20), in polluted soils (21, 22), and in an indoor swimming pool (23). Nevertheless, the natural habitat of this organism (24, 25) as well as the possible sources of patient contamination remain unknown. Only one report documented the contamination of a patient by an isolate originating from well water (26). The identification of potential reservoirs in the environment might constitute an aid to the prevention of infection in CF patients and in the immunocompromised population. In our laboratory, we have established a collection of all the clinical strains of A. xylosoxidans recovered in our hospital, including 808 isolates from CF patients (since 1995) and 32 isolates from non-CF patients (since 2010). For all these isolates, antimicrobial susceptibility tests have been performed by the disk diffusion method and genotyping analysis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

The aim of the present study was (i) to search different environments (natural, hospital, and domestic) for the presence of A. xylosoxidans strains potentially involved in patient contamination, (ii) to study the antimicrobial susceptibility of the isolates, and (iii) to compare the environmental isolates to clinical isolates from our collection by a genotyping method.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling sites.

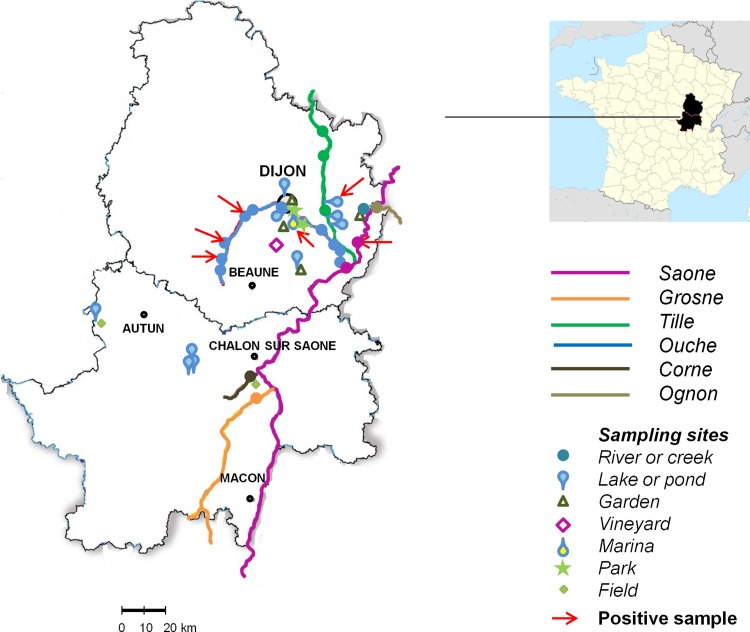

We chose various sampling sites to get an overview of the presence of A. xylosoxidans in diverse environments: hospital, domestic, and outdoor. For outdoor environment sampling sites, we focused our investigation on Cote d'Or and Saone et Loire. Indeed, more than 60% of CF colonized patients visiting our CF center live in these two areas of Burgundy, France. From September 2011 to December 2012, a total of 339 samples were collected. In the University Hospital of Dijon (1,772 beds), 188 distinct samples were obtained in 10 different departments located in 4 different buildings: 4 intensive care units (ICU), a pneumology and nephrology department (first building), a hematology department (second building), a pediatrics department and the CRCM (Centre de Ressources et de Compétences de la Mucoviscidose), where cystic fibrosis patients receive care (third building), and a dentistry department (fourth building, 5 km away). In each department, environmental wet surfaces in patients' rooms (drains of sinks used for hand washing, shower drains, and toilet bowls) and medication preparation rooms (sink drains) and nearby offices (ward sluice sinks) were swabbed. The number of samples per room depended on the department (e.g., ICU rooms are not equipped with showers or toilets). In the dentistry department, we collected water from dental unit waterlines (14 chairs). A total of 58 domestic samples were collected from 16 residences of healthy volunteers (bathroom sinks, kitchen sinks, shower drains, and toilet bowls). These apartments or houses were located in Dijon (n = 14) and in two villages, Domois (n = 1) and St Nicolas les Citeaux (n = 1) (10 km south and 35 km south of Dijon, respectively). Finally, 93 samples were obtained from outdoor environments: soils (n = 8), waters (n = 36), mud from rivers or lakes (n = 29), and plants (n = 20). The sampling sites included 4 lakes with recreational activities (from 7 to 37 ha), 6 rivers (9 to 480 km long), 1 creek, 1 marina, 6 ponds, 2 fields, 1 vineyard, 2 public parks, and 5 domestic vegetable gardens. Plant collection included the aerial parts (leaf, stem, branch, or fruit) of herbs, moss, vines, mushrooms, strawberries, and oaks and the roots of alfalfa, tomato plants, green bean plants, clover, lupine, carrots, convolvulus, and vines. The outdoor sampling sites are indicated on the map in Fig. 1.

Fig 1.

Outdoor sampling sites in Cote d'Or and Saone-et-Loire, France. Red arrows show positive sampling sites. (Map used with permission from CartesFrance.fr.)

Sample collection.

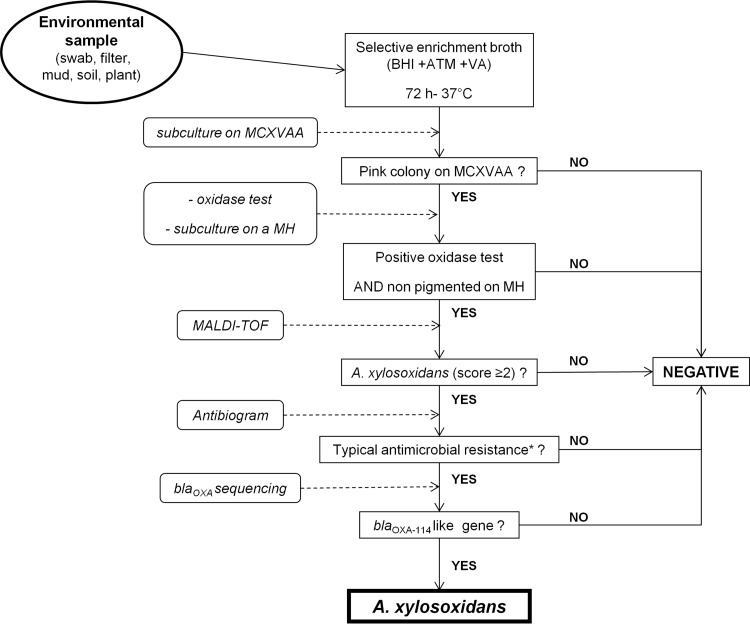

Domestic and hospital samples were obtained using sterile cotton swabs. Sink and shower drains were sampled by rotating a cotton swab inserted approximately 5 cm into the sink drain. Toilets were sampled with sterile cotton swabs inserted under the rim of the toilet bowl. Sluice sinks were sampled by inserting swabs in the wastewater and collection bowl and grid surfaces. Outdoor samples were collected in sterile containers. Approximately 1 g of mud or soil and 5 cm2 of parts of plants (roots or aerial parts) were disrupted with sterile devices and then vigorously shaken with brain heart infusion enrichment broth (BHI). Water samples were concentrated by filtration of 500 ml through sterile 0.45-μm membrane filters (Milliflex Plus; Millipore, Billerica, MA). Samples were stored at room temperature for less than 24 h before processing. The protocol for isolation and identification of A. xylosoxidans is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig 2.

Isolation and identification protocol of A. xylosoxidans strains from environmental samples. A typical antibiogram (*) is defined by resistance to all aminoglycosides tested, aztreonam, cefoxitin, cefotaxime, and cefepime. VA, vancomycin; ATM, aztreonam.

Culture of the samples.

In our experience, from previous studies conducted on hospital environment samples, samples such as those collected in this study often contain a wide diversity of Gram-negative bacilli, including nonfermenting Gram-negative rods (NF-GNB) and Enterobacteriaceae. All these organisms grow on Drigalski agar; therefore, the detection of A. xylosoxidans among the environmental flora on this medium is impossible. Given that A. xylosoxidans is innately resistant to aztreonam, we tested a Drigalski medium supplemented with this antibiotic. On this medium, we still observed the growth of many different oxidase-positive NF-GNB despite the antibiotic selection. Therefore, we developed a selective enrichment procedure to enhance our ability to detect A. xylosoxidans in the samples. Swabs, filters, mud, soil samples, and plants were first enriched with 10 ml of BHI supplemented with aztreonam (32 mg/liter) and vancomycin (32 mg/liter) for 72 h at 37°C. One drop of each of the enrichment cultures was plated on MCXVAA medium and incubated 48 h at 37°C. MCXVAA agar is a medium that we designed for the study: MacConkey agar (selective for Gram-negative rods) supplemented with xylose (5 g/liter), vancomycin (20 mg/liter) (to prevent growth of Gram-positive bacteria), aztreonam (20 mg/liter), and amphotericin B (5 mg/liter) (to prevent fungal growth). In preliminary experiments (data not shown), we checked that A. xylosoxidans reference strains (CIP 7132T, CIP 102236, CIP 101902, and CIP 110540) as well as 15 clinical strains from our previously described collection (13) grew on MCXVAA agar. A. xylosoxidans forms pink colonies, resulting from acidification of this medium due to xylose oxidation. Moreover, MCXVAA agar is unable to support the proliferation of Gram-positive bacteria or yeasts/fungi. Nevertheless, it is important to note that other aztreonam-resistant Gram-negative rods are able to grow on this medium. For example S. maltophilia forms yellow colonies, and some Pseudomonas spp., other Achromobacter spp., and Bordetella spp. also appear as pink colonies. Therefore, pink colonies must undergo further identification.

Identification.

The identification scheme is summarized in Fig. 2. Given that A. xylosoxidans is an oxidase-positive bacillus forming pink colonies on MCXVAA agar and nonpigmented ones on Mueller-Hinton agar, we retained for further identification only the strains fulfilling these 3 criteria. These strains were identified by matrix-assisted laser-desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF; Bruker). This technique proved to be efficient for identifying A. xylosoxidans (27–29). According to the manufacturer's instructions, a score of ≥2 indicates a “secure genus identification, and probable species identification.” Moreover, such a score was obtained for the reference strains CIP 7132T, CIP 102236, CIP 101902, and CIP 110540. Therefore, the isolates identified as A. xylosoxidans with a score of ≥2 were subjected to susceptibility tests to select the strains harboring the typical resistance profile (cefoxitin, cefotaxime, cefepime, aztreonam, kanamycin, tobramycin, netilmicin, amikacin, and gentamicin). The last step of identification consisted of detecting and sequencing the naturally occurring blaOXA genes of A. xylosoxidans (blaOXA-114 and variants [13, 30, 31] and blaOXA-243 and variants [13]). We used the primer pair OXA-114A and OXA-114B (30). In cases where PCR was negative, we used the primer pair AXXA-F and AXXA-R (13). Reference strains of A. xylosoxidans described above were used as positive controls for PCRs. Positive PCR products were purified with a Millipore centrifugal filter unit (Amicon Microcon PCR kit; Millipore). Double-strand sequencing was then performed using BigDye v1.1 Terminator chemistry and a 3130XL genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Susceptibility tests.

Susceptibility tests of the isolates were performed by the disk diffusion method and interpreted according to recommendations of EUCAST (http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/Breakpoint_table_v_3.1.pdf). The following antibiotics were tested: β-lactams (ticarcillin, ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, piperacillin, piperacillin-tazobactam, cefoxitin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefepime, imipenem, meropenem, doripenem, and aztreonam), ciprofloxacin, and aminoglycosides (amikacin, gentamicin, kanamycin, netilmicin, and tobramycin).

Genotyping by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

All the strains identified as A. xylosoxidans were subjected to genotypic analysis by PFGE as previously described (32). Total DNA was analyzed after digestion with the restriction enzyme XbaI. Electrophoresis was carried out for 20 h at 5.4 V/cm, with pulse times ranging from 5 s to 35 s, using the CHEF-DR II system (Bio-Rad). Restriction patterns were interpreted according to the criteria of Tenover et al. (33), and the isolates were classified into pulsotypes (A, B, C, etc.). These pulsotypes were compared to those of the clinical isolates of our collection gathered since 2006. We have recently described isolates recovered from 21 CF patients (P1 to P21) (13). Clonally related isolates belong to the same pulsotype. Pulsotypes recovered only once and different from all those already identified to date in our hospital were designated “unique.”

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

OXA-114p, -114q, -114r, -114s, -114t, -114u, and -114v gene sequences have been submitted to GenBank under accession numbers KF573363, KF573364, KF573365, KF573366, KF573367, KF573368, and KF573369. OXA-243e's gene sequence has been submitted to GenBank under accession number KF582664.

RESULTS

The results are summarized in Table 1 (hospital and domestic), in Table 2 (outdoor) and in Table 3 (susceptibility tests).

Table 1.

Hospital and domestic samples

| Source | No. of samples (no. positive) |

Total no. of strains | No. of pulsotypes | Pulsotype(s) (OXA variant[s])a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handwashing-sink drains | Toilet pans | Shower drains | Sluice sinks | Total | ||||

| Hospital | ||||||||

| ICU-1 | 25 (1) | 2 | 27 (1) | 1 | 1 | A (OXA-114h) | ||

| ICU-2 | 11 (1) | 11 (1) | 1 | 1 | Un. (OXA-114i) | |||

| ICU-3 | 5 (1) | 2 (1) | 7 (2) | 2 | 1 | B (OXA-114p) | ||

| ICU-4 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 0 | ||||

| Pediatrics | 8 (3) | 1 | 9 (3) | 3 | 2 | C (OXA-114f), Db (OXA-114h) | ||

| CF Center | 4 | 1 | 1 (1) | 6 (1) | 1 | 1 | E (OXA-114f) | |

| Nephrology | 5 | 1 | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | 12 (3) | 3 | 1 | F (OXA-114 m) |

| Pneumology | 13 (2) | 6 | 6 (4) | 2 | 27 (6) | 7 | 6 | G (OXA-114h), H (OXA-114a), Un. (OXA-114e), Un. (OXA-114g), Un. (OXA-114s), Un. (OXA-114s) |

| Hematology | 43 (7) | 6 | 17 (3) | 1 | 67 (10) | 11 | 6 | C (OXA-114f), I (OXA-114c), Un. (OXA-114g), Un. (OXA-114g), Un. (OXA-114l), Un. (OXA-243e) |

| Dentistry | 14c (4) | 4 | 1 | J (OXA-114r) | ||||

| Total | 121 (15) | 15 (0) | 25 (8) | 13 (4) | 188 (31) | 33 | 19 | |

| Domestic | 31 (3) | 13 (0) | 14 (4) | 58 (7) | 9 | 9 | Un. (OXA-114a), Un. (OXA-114c), Un. (OXA-114c), Un. (OXA-114f), K (OXA-114h), Un. (OXA-114i), Un. (OXA-114j), Un. (OXA-114t), Un. (OXA-114v) | |

Letters designate pulsotypes that were recovered more than once. Un., unique (i.e., the pulsotype was recovered only once). Pulsotypes in bold are identical to clinical strain pulsotypes. Pulsotype C includes strains from 2 departments and clinical strains.

Pulsotype also recovered in one sample from the Saone River.

Dental chair water samples.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the strains found at outdoor positives sampling sitesa

| Outdoor source and sample type | No. of samples (no. positive) | No. of pulsotypes | Pulsotype(s) (OXA variant)b | Description of source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ouche River (95.4 km) | ||||

| Water | 11 (3) | 3 | Un. (OXA-114b) Un. (OXA-114g) Un. (OXA-114g) | Water treatment, port |

| Mud | 13 (2) | 2 | Un. (OXA-114h) Un. (OXA-114q) | Water treatment |

| Saone River water (480 km) | 2 (1) | 1 | Dc (OXA-114h) | Boating, fishing |

| Lake Arc-sur-Tille water (36 ha) | 2 (1) | 1 | Un. (OXA-114u) | Swimming, water sports |

| Dijon Marina water (3 ha) | 1 (1) | 1 | Un. (OXA-114a) | Port |

| Total | 29 (8) | 8 |

Only one strain was isolated from each positive sample.

Letters designate pulsotypes that were recovered more than once. Un., unique (i.e., the pulsotype was recovered only once).

This pulsotype was also recovered in the pediatrics department of the hospital.

Table 3.

Number of isolates categorized as intermediate or resistant among hospital, domestic, and outdoor strains

| Antimicrobial agenta | No. of intermediate or resistant isolates |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital (n = 33) | Domestic (n = 9) | Outdoor (n = 8) | Total (n = 50) | |

| TIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TCC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PIP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TZP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CAZ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| IPM | 10 | 1 | 4 | 15 |

| MEM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DOR | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| CIP | 32 | 9 | 8 | 49 |

TIC, ticarcillin; TCC, ticarcillin plus clavulanic acid; PIP, piperacillin; TZP, piperacillin plus tazobactam; CAZ, ceftazidime; IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; DOR, doripenem; CIP, ciprofloxacin.

Detection of strains.

The protocol used in this study allowed us to identify a total of 50 isolates of A. xylosoxidans among the 339 samples, mainly in the hospital environment (n = 33) but also in domestic (n = 9) and outdoor (n = 8) environments.

Hospital samples.

A total of 33 strains were isolated in 31 of the 188 samples. All studied wards were concerned with the exception of ICU-4. A. xylosoxidans has been recovered in hand-washing sink drains, shower drains, and sluice sinks but not in toilet bowls. Water from 4 of the 14 dental chairs was contaminated with A. xylosoxidans.

Domestic samples.

A total of 9 strains were isolated in 7 out of the 58 samples. These findings concerned 6 of the 16 residences investigated. A. xylosoxidans was detected in 4 of 14 shower drains (6 strains), in 1 of 16 bathroom sink drains (1 strain), and in 2 of 15 kitchen sink drains (2 strains). All 13 toilet bowls sampled were negative.

Outdoor samples.

A total of 8 strains were isolated from the 93 samples, all in water or mud samples. None of these strains were isolated from plants or soils. The positive samples are indicated with red arrows in Fig. 1 and described in Table 2. Five strains were isolated from the Ouche River (at 3 different sites), one was from Lake Arc-sur-Tille, one was from the Port du Canal marina in Dijon, and the last one was from the Saone River in Auxonne.

Genotyping by PFGE.

Among the 50 isolates obtained, we distinguished 35 pulsotypes with PFGE: 19 pulsotypes in hospital samples, 9 in domestic samples, and 8 in outdoor samples, with one pulsotype being identical in hospital and outdoor isolates. Indeed, the isolate detected in water from the Saone River (pulsotype D) was clonally related to isolates recovered in the pediatrics department (2 different hand-washing sink drains). In samples from the hospital environment, we detected isolates belonging to the same pulsotype (pulsotype C) in two departments, pediatrics (one hand-washing sink drain) and hematology (3 samples in a patient's room located on level 0 of the unit and the hand-washing sink drain of a medication preparation room on level 1). We performed repeated samplings at two locations. The first one was the CF center, where we recovered the isolate harboring pulsotype E twice at an 8-month interval (October 2011 and July 2012). The second location was ICU-1, from which the isolate (pulsotype A) was isolated 3 times (September 2011, October 2011, and February 2012). In the dentistry department, the isolates recovered from the 4 dental chairs water belonged to the same pulsotype (pulsotype J). Comparison of environmental with clinical isolates pulsotypes revealed interesting findings. Among the 35 pulsotypes from environmental isolates, 6 were identical to that of patients. In ICU-1, the strain recovered from a wound of a patient had the same pulsotype as the one isolated in the hand-washing sink of his room during his hospitalization (pulsotype A). Pulsotype C, including 6 environmental isolates, was identical to that of strains isolated in tracheal aspirates of 2 non-CF patients hospitalized in ICU-1 in 2010. The strain recovered from a shower in the pneumology department was clonally related (pulsotype G) to that recovered from the sputum of a CF patient who had been chronically colonized since 1995 (patient P19) but had not previously been hospitalized in that ward. Pulsotype I, including 2 strains recovered in the hematology ward in December 2012 (1 shower and 1 hand-washing sink in two rooms), also included isolates from 6 patients. Among these patients, only one had been hospitalized in the hematology department (blood culture sampled in November 2012). For the other patients, the strains were recovered from sputum samples. Two of them had been hospitalized: one in the pneumology department (March 2012) and one in ICU-2 (January 2013). One outpatient suffering from bronchiectasis regularly attended the pneumology department. (isolate recovered in April 2012). The last two were CF patients (isolates recovered in 2007–2008) P7 and P32. Finally, one domestic isolate recovered in a hand-washing sink drain was identical (pulsotype K) to that of one CF patient who had been chronically colonized since 1997 (patient P8).

Antimicrobial susceptibilities.

The majority of the isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin (49/50). Fifteen isolates were categorized as intermediate or resistant to imipenem (10 hospital, 4 outdoor, and 1 domestic isolate), with one of them (a hospital isolate) also being resistant to ceftazidime and 5 (2 hospital, 2 outdoor, and 1 domestic isolate) being also resistant to doripenem. All isolates remained susceptible to meropenem, ticarcillin, ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, piperacillin, and piperacillin-tazobactam. The results are reported in Table 3.

blaOXA sequencing.

On the basis of antimicrobial susceptibility tests and MALDI-TOF analysis, a total of 51 strains were subjected to PCRs. A PCR product was obtained for 50 isolates and sequenced. We could not detect any blaOXA gene in the remaining strain; therefore, this strain was not identified as A. xylosoxidans and was excluded from the study. Many variants of OXA-114 have been detected in 49 strains. Among them, the variants OXA-114a, -114b, -114c, -114f, -114g, -114h, -114i, -114j, -114l, and -114m had already been identified in clinical isolates. We also detected 7 new variants: OXA-114p, -114q, -114r, -114s, -114t, -114u, and -114v. Finally, only one strain harbored a variant of OXA-243, the new variant OXA-243e.

DISCUSSION

A. xylosoxidans is an important emerging pathogen among CF patients worldwide, commonly described as an environmental pathogen widely distributed in soils and waters (4, 14, 34, 35). Nevertheless, this statement is not supported by any study in natural environments. The scarce reports concern a very limited number of isolates which were recovered mainly from polluted sites. Because of the high prevalence of A. xylosoxidans in our CF center and its emergence in immunocompromised patients hospitalized in our university hospital, an investigation of reservoirs was required. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to look for the presence of A. xylosoxidans in various environments and to compare the environmental isolates with the clinical ones. For this comparison, we chose the PFGE method, commonly used to analyze the clinical isolates of this species (14, 16, 31, 32, 36). Very recently (2012) and after the beginning of the present study, several schemes of multilocus sequence typing were proposed for A. xylosoxidans (37, 38). This method seems to be interesting for global epidemiological studies and allows interlaboratory comparisons. Nevertheless, all the isolates from our collection have been subjected to PFGE analysis since 1995, and we took advantage of this large amount of available data.

In the hospital, environmental samplings targeted potential sources of contamination already reported for other pathogens, such as P. aeruginosa (39). For outdoor environmental samples, we focused on two areas of Burgundy (Cote d'Or and Saone et Loire) because most of our infected CF patients live there. We searched for A. xylosoxidans in different sites related to various common activities: walking (parks and fields), gardening (gardens), and fishing, swimming, or boating (rivers, lakes, and the marina). Because of bacterial species richness in these environments, we designed for this study an identification procedure and a selective medium (MCXVAA) to detect A. xylosoxidans. This allowed us to isolate 50 strains of A. xylosoxidans from wet environments, including water, mud, and sink and shower drains. Nevertheless, the use of a selective medium may have led to underestimation of the presence of A. xylosoxidans, as already described for other media (40). We observed a high diversity among the 50 environmental isolates: they were classified into 35 pulsotypes. It is noteworthy that the 17 domestic and outdoor strains all belonged to different pulsotypes. Moreover, we detected many oxacillinase variants (n = 19). These findings strongly suggested that A. xylosoxidans is well adapted to the wet environments of hospitals, outdoor sites, and domiciles that act as reservoirs. In the hospital, we found various A. xylosoxidans isolates in 9 out of 10 wards studied. Some hospital isolates had the same pulsotype (33 isolates for 19 pulsotypes). For instance, in the nephrology department, the three strains isolated from different sites (in one patient's room and two sluice sinks) were identical. Similarly, a single strain contaminated the water of four dental chairs. In these cases, hand contamination of staff members might explain the spread of the isolate through the ward. In another case, we suspected contamination of the water distribution pipe. Indeed, six isolates belonging to pulsotype C were recovered in the hematology and pediatrics departments, two wards located in adjacent buildings supplied by the same water distribution line. We did not detect A. xylosoxidans in the water (data not shown): perhaps the volume of the water was too small, or more likely the contamination occurred months or years ago. Our bacterial findings provided information about the presence of A. xylosoxidans in the sink drain at the moment when we obtained the samples but did not allow us to draw conclusions about the temporal and spatial evolution of the colonization. Nevertheless, the results from repeated samplings at two points indicate that isolates can persist in some sites for long periods (at least 8 months), probably thanks to biofilm formation. Surprisingly, we identified 10 hospital environmental isolates that were indistinguishable from patients' isolates. In most cases, it was not possible to determine if the patients acquired A. xylosoxidans from the hospital environment or if the environment had been contaminated by an infected patient, because the patients' strains had been isolated mainly before this study. In all cases but one, the patients had not been hospitalized in the wards where the clonally related environmental isolates were detected. For example, the strains harboring pulsotype I from the hematology department have also been isolated from 6 patients in samples collected over 6 years (in the pneumology department, the hematology department, ICU-2, and the CF center). This reflects a spread of the isolates in all the wastewater system of the hospital, constituting a reservoir of A. xylosoxidans. Therefore, hospitalized patients might be contaminated when splash-back occurs, for instance during showering, hand washing, or tooth brushing, as has been described for other pathogens (41, 42). The role of dental chair waters as a source of contamination has to be taken into account for outpatients receiving dental care.

Our study also pointed out that A. xylosoxidans is widespread in outdoor aquatic and in domestic environments. Indeed, the organism was detected in 6 samples from bodies of water used for recreational activities and from 6 of 16 residences. For outdoor environments, 4 isolates were recovered from the Ouche River (water and mud) near the points where the effluents from wastewater treatment stations of local villages flow into the river. Moreover, one isolate recovered from the Saone River, 35 km away from Dijon, was identical to one isolate in the pediatrics department of the hospital (pulsotype D). These findings may reflect bacterial pollution of the rivers by the effluents. In domestic environments, A. xylosoxidans was detected in hand-washing sinks and shower drains but not in toilet bowls. The colonization of sinks and shower drains by P. aeruginosa has already been described in home environment studies (43, 44). These materials are in contact with soap as well as with chemical products used for cleaning, many of them containing alkyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride, a quaternary ammonium compound. The natural resistance of A. xylosoxidans to these compounds might explain its presence in the domestic samples (45). We did not detect A. xylosoxidans in the toilet bowls, probably because the site sampled (under the rim of the toilet bowl) is easily accessible for regular cleaning and free of stagnant water. Interestingly, one isolate recovered from a residence located in Dijon was identical to that harbored by a CF patient since 1997 who has always lived 37 km away from Dijon. This finding remains unexplained.

These results indicate that in everyday life, CF patients can be exposed to reservoirs of A. xylosoxidans. For several authors, the diversity among CF patients isolates suggested the acquisition from various environmental sources (13, 31, 46). This hypothesis of contamination from these different niches out of hospital is corroborated by several of our observations. First, the environmental isolates described here are varied: they belonged to many distinct pulsotypes and harbored many oxacillinase variants. Second, environmental and clinical isolates share common variants of OXA-114. Finally, with regard to antimicrobial resistance, it is interesting that all environmental strains were resistant to ciprofloxacin and remained susceptible to ticarcillin, piperacillin, ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, and piperacillin-tazobactam like most strains (75%) isolated from CF patients' sputa at first positive culture in our CF center. For the first time, we have identified various environmental reservoirs of A. xylosoxidans and demonstrated that some of these isolates are indistinguishable from clinical ones. In hospital and domestic environments, A. xylosoxidans is widely encountered in sink drains, which are therefore potential sources of contamination for immunocompromised or CF patients. Particular cleaning procedures might be a help in preventing the acquisition of this emerging pathogen. Larger studies in other geographical regions need to be conducted to confirm our findings. A prospective study analyzing the domestic environments of CF patients would be of particular interest, and our detection procedure may be suitable for this purpose.

In conclusion, there is a need for a global approach, examining medical but also environmental and probably animal aspects of contamination, to better understand the worldwide increased prevalence of A. xylosoxidans infections and its possible relationship to anthropogenic activity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nathalie Sixt and her team, who helped with the water filtrations.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 September 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Ciofu O, Hansen CR, Hoiby N. 2013. Respiratory bacterial infections in cystic fibrosis. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 19:251–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Razvi S, Quittell L, Sewall A, Quinton H, Marshall B, Saiman L. 2009. Respiratory microbiology of patients with cystic fibrosis in the United States, 1995 to 2005. Chest 136:1554–1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salvatore D, Buzzetti R, Baldo E, Furnari ML, Lucidi V, Manunza D, Marinelli I, Messore B, Neri AS, Raia V, Mastella G. 2012. An overview of international literature from cystic fibrosis registries. Part 4: update 2011. J. Cyst. Fibros. 11:480–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waters V. 2012. New treatments for emerging cystic fibrosis pathogens other than Pseudomonas. Curr. Pharm. Des. 18:696–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hogardt M, Ulrich J, Riehn-Kopp H, Tummler B. 2009. EuroCareCF quality assessment of diagnostic microbiology of cystic fibrosis isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3435–3438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kidd TJ, Ramsay KA, Hu H, Bye PT, Elkins MR, Grimwood K, Harbour C, Marks GB, Nissen MD, Robinson PJ, Rose BR, Sloots TP, Wainwright CE, Bell SC. 2009. Low rates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa misidentification in isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1503–1509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed MS, Nistal C, Jayan R, Kuduvalli M, Anijeet HK. 2009. Achromobacter xylosoxidans, an emerging pathogen in catheter-related infection in dialysis population causing prosthetic valve endocarditis: a case report and review of literature. Clin. Nephrol. 71:350–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aisenberg G, Rolston KV, Safdar A. 2004. Bacteremia caused by Achromobacter and Alcaligenes species in 46 patients with cancer (1989–2003). Cancer 101:2134–2140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tena D, Gonzalez-Praetorius A, Perez-Balsalobre M, Sancho O, Bisquert J. 2008. Urinary tract infection due to Achromobacter xylosoxidans: report of 9 cases. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 40:84–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turel O, Kavuncuoglu S, Hosaf E, Ozbek S, Aldemir E, Uygur T, Hatipoglu N, Siraneci R. 2013. Bacteremia due to Achromobacter xylosoxidans in neonates: clinical features and outcome. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 17:450–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bador J, Amoureux L, Blanc E, Neuwirth C. 2013. Innate aminoglycoside resistance of Achromobacter xylosoxidans is due to AxyXY-OprZ, an RND-type multidrug efflux pump. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:603–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bador J, Amoureux L, Duez JM, Drabowicz A, Siebor E, Llanes C, Neuwirth C. 2011. First description of an RND-type multidrug efflux pump in Achromobacter xylosoxidans, AxyABM. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4912–4914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amoureux L, Bador J, Siebor E, Taillefumier N, Fanton A, Neuwirth C. 2013. Epidemiology and resistance of Achromobacter xylosoxidans from cystic fibrosis patients in Dijon, Burgundy: first French data. J. Cyst. Fibros. 12:170–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lambiase A, Catania MR, Del Pezzo M, Rossano F, Terlizzi V, Sepe A, Raia V. 2011. Achromobacter xylosoxidans respiratory tract infection in cystic fibrosis patients. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 30:973–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Baets F, Schelstraete P, Van Daele S, Haerynck F, Vaneechoutte M. 2007. Achromobacter xylosoxidans in cystic fibrosis: prevalence and clinical relevance. J. Cyst. Fibros. 6:75–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pereira RH, Carvalho-Assef AP, Albano RM, Folescu TW, Jones MC, Leao RS, Marques EA. 2011. Achromobacter xylosoxidans: characterization of strains in Brazilian cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:3649–3651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molina-Cabrillana J, Santana-Reyes C, Gonzalez-Garcia A, Bordes-Benitez A, Horcajada I. 2007. Outbreak of Achromobacter xylosoxidans pseudobacteremia in a neonatal care unit related to contaminated chlorhexidine solution. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 26:435–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olshtain-Pops K, Block C, Temper V, Hidalgo-Grass C, Gross I, Moses AE, Gofrit ON, Benenson S. 2011. An outbreak of Achromobacter xylosoxidans associated with ultrasound gel used during transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy. J. Urol. 185:144–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho YN, Mathew DC, Hsiao SC, Shih CH, Chien MF, Chiang HM, Huang CC. 2012. Selection and application of endophytic bacterium Achromobacter xylosoxidans strain F3B for improving phytoremediation of phenolic pollutants. J. Hazard Mater. 219–220:43–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jha P, Kumar A. 2009. Characterization of novel plant growth promoting endophytic bacterium Achromobacter xylosoxidans from wheat plant. Microb. Ecol. 58:179–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buckova M, Godocikova J, Zamocky M, Polek B. 2010. Screening of bacterial isolates from polluted soils exhibiting catalase and peroxidase activity and diversity of their responses to oxidative stress. Curr. Microbiol. 61:241–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh NS, Singh DK. 2011. Biodegradation of endosulfan and endosulfan sulfate by Achromobacter xylosoxidans strain C8B in broth medium. Biodegradation 22:845–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmes B, Snell JJ, Lapage SP. 1977. Strains of Achromobacter xylosoxidans from clinical material. J. Clin. Pathol. 30:595–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brusse HJ, Auling G. 2005. Genus II. Achromobacter Yabuuchi and Yano 1981, 477VP emend. Yabuuchi, Kawamura, Kosako and Ezaki 1998a, 1083, p 658–662 In Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, Garrity GM. (ed), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, 2nd ed, vol 2, part C Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wirsing von Konig CH RM, Coenye T. 2011. Bordetella and related genera, p 739–750 In Versalovic J, C K, Jorgensen JH, Funke G, Landry ML, Warnock DW. (ed), Manual of clinical microbiology, 10th ed, vol 1 ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spear JB, Fuhrer J, Kirby BD. 1988. Achromobacter xylosoxidans (Alcaligenes xylosoxidans subsp. xylosoxidans) bacteremia associated with a well-water source: case report and review of the literature. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:598–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Degand N, Carbonnelle E, Dauphin B, Beretti JL, Le Bourgeois M, Sermet-Gaudelus I, Segonds C, Berche P, Nassif X, Ferroni A. 2008. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry for identification of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli isolated from cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:3361–3367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desai AP, Stanley T, Atuan M, McKey J, Lipuma JJ, Rogers B, Jerris R. 2012. Use of matrix assisted laser desorption ionisation-time of flight mass spectrometry in a paediatric clinical laboratory for identification of bacteria commonly isolated from cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Pathol. 65:835–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marko DC, Saffert RT, Cunningham SA, Hyman J, Walsh J, Arbefeville S, Howard W, Pruessner J, Safwat N, Cockerill FR, Bossler AD, Patel R, Richter SS. 2012. Evaluation of the Bruker Biotyper and Vitek MS matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry systems for identification of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli isolated from cultures from cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:2034–2039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doi Y, Poirel L, Paterson DL, Nordmann P. 2008. Characterization of a naturally occurring class D beta-lactamase from Achromobacter xylosoxidans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1952–1956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turton JF, Mustafa N, Shah J, Hampton CV, Pike R, Kenna DT. 2011. Identification of Achromobacter xylosoxidans by detection of the blaOXA-114-like gene intrinsic in this species. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 70:408–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheron M, Abachin E, Guerot E, El-Bez M, Simonet M. 1994. Investigation of hospital-acquired infections due to Alcaligenes denitrificans subsp. xylosoxydans by DNA restriction fragment length polymorphism. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1023–1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, Mickelsen PA, Murray BE, Persing DH, Swaminathan B. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrado L, Branas P, Orellana MA, Martinez MT, Garcia G, Otero JR, Chaves F. 2013. Molecular characterization of Achromobacter isolates from cystic fibrosis and non-cystic fibrosis patients in Madrid, Spain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51:1927–1930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siebor E, Llanes C, Lafon I, Ogier-Desserrey A, Duez JM, Pechinot A, Caillot D, Grandjean M, Sixt N, Neuwirth C. 2007. Presumed pseudobacteremia outbreak resulting from contamination of proportional disinfectant dispenser. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 26:195–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moissenet D, Baculard A, Valcin M, Marchand V, Tournier G, Garbarg-Chenon A, Vu-Thien H. 1997. Colonization by Alcaligenes xylosoxidans in children with cystic fibrosis: a retrospective clinical study conducted by means of molecular epidemiological investigation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24:274–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ridderberg W, Wang M, Norskov-Lauritsen N. 2012. Multilocus sequence analysis of isolates of Achromobacter from patients with cystic fibrosis reveals infecting species other than Achromobacter xylosoxidans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:2688–2694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spilker T, Vandamme P, Lipuma JJ. 2012. A multilocus sequence typing scheme implies population structure and reveals several putative novel Achromobacter species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:3010–3015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hota S, Hirji Z, Stockton K, Lemieux C, Dedier H, Wolfaardt G, Gardam MA. 2009. Outbreak of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization and infection secondary to imperfect intensive care unit room design. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 30:25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kodaka H, Iwata M, Yumoto S, Kashitani F. 2003. Evaluation of a new agar medium containing cetrimide, kanamycin and nalidixic acid for isolation and enhancement of pigment production of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in clinical samples. J. Basic Microbiol. 43:407–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Breathnach AS, Cubbon MD, Karunaharan RN, Pope CF, Planche TD. 2012. Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa outbreaks in two hospitals: association with contaminated hospital waste-water systems. J. Hosp. Infect. 82:19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoque SN, Graham J, Kaufmann ME, Tabaqchali S. 2001. Chryseobacterium (Flavobacterium) meningosepticum outbreak associated with colonization of water taps in a neonatal intensive care unit. J. Hosp. Infect. 47:188–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Regnath T, Kreutzberger M, Illing S, Oehme R, Liesenfeld O. 2004. Prevalence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in households of patients with cystic fibrosis. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 207:585–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schelstraete P, Van Daele S, De Boeck K, Proesmans M, Lebecque P, Leclercq-Foucart J, Malfroot A, Vaneechoutte M, De Baets F. 2008. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the home environment of newly infected cystic fibrosis patients. Eur. Respir. J. 31:822–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reverdy ME, Freney J, Fleurette J, Coulet M, Surgot M, Marmet D, Ploton C. 1984. Nosocomial colonization and infection by Achromobacter xylosoxidans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 19:140–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ridderberg W, Bendstrup KE, Olesen HV, Jensen-Fangel S, Norskov-Lauritsen N. 2011. Marked increase in incidence of Achromobacter xylosoxidans infections caused by sporadic acquisition from the environment. J. Cyst. Fibros. 10:466–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]