Abstract

Anaerobic activation of benzene is expected to represent a novel biochemistry of environmental significance. Therefore, benzene metabolism was investigated in Geobacter metallireducens, the only genetically tractable organism known to anaerobically degrade benzene. Trace amounts (<0.5 μM) of phenol accumulated in cultures of Geobacter metallireducens anaerobically oxidizing benzene to carbon dioxide with the reduction of Fe(III). Phenol was not detected in cell-free controls or in Fe(II)- and benzene-containing cultures of Geobacter sulfurreducens, a Geobacter species that cannot metabolize benzene. The phenol produced in G. metallireducens cultures was labeled with 18O during growth in H218O, as expected for anaerobic conversion of benzene to phenol. Analysis of whole-genome gene expression patterns indicated that genes for phenol metabolism were upregulated during growth on benzene but that genes for benzoate or toluene metabolism were not, further suggesting that phenol was an intermediate in benzene metabolism. Deletion of the genes for PpsA or PpcB, subunits of two enzymes specifically required for the metabolism of phenol, removed the capacity for benzene metabolism. These results demonstrate that benzene hydroxylation to phenol is an alternative to carboxylation for anaerobic benzene activation and suggest that this may be an important metabolic route for benzene removal in petroleum-contaminated groundwaters, in which Geobacter species are considered to play an important role in anaerobic benzene degradation.

INTRODUCTION

Elucidating the pathways for anaerobic benzene degradation is important because of the environmental significance of this process and its potential biochemical novelty (1). For example, contamination of groundwater with hydrocarbons often leads to the development of anaerobic conditions, and benzene is one of the most mobile and toxic pollutants (1–4). Numerous studies with mixed microbial communities have documented that benzene can be degraded under anaerobic conditions (1, 5–12), but benzene is typically only slowly removed from anaerobic contaminated groundwater unless anaerobic microbial metabolism is artificially stimulated with the addition of Fe(III) chelators (13, 14), electron shuttles (15), sulfate (5), or an electrode (16).

It was previously found that the archaeon Ferroglobus placidus is capable of anaerobically oxidizing benzene to carbon dioxide with Fe(III) as the sole electron acceptor (17). Analysis of gene expression patterns indicated that benzene was first metabolized to benzoate (17), which was then metabolized via well-known pathways for anaerobic benzoate metabolism (18). The proposed carboxylation of benzene by F. placidus is consistent with evidence suggesting carboxylation in enrichment cultures (19–23). A gene encoding a putative benzene carboxylase in F. placidus was identified (17), but further analysis has been limited by a lack of a system for genetic manipulation of F. placidus.

A potential alternative for anaerobic benzene activation is conversion to phenol. This mechanism was previously proposed for Dechloromonas aromatica, which grows on benzene in anaerobic medium with nitrate as the electron acceptor (7, 24, 25). However, several lines of evidence suggest that the initial activation of benzene in D. aromatica involves molecular oxygen generated intracellularly from nitrate (1, 9, 26, 27). For example, the D. aromatica genome lacks genes for the anaerobic degradation of aromatic compounds that are highly conserved in all other organisms capable of anaerobic metabolism of monoaromatics but contains multiple genes for monooxygenases that could be involved in activation of benzene with oxygen (26). Furthermore, the oxygen incorporated into the benzene ring to produce phenol does not come from water, as would be expected for anaerobic metabolism of benzene to phenol (24). Another potential line of evidence for the possibility of anaerobic benzene activation to phenol is the presence of phenol in enrichment cultures anaerobically degrading benzene (12, 28, 29). However, it has been suggested that the phenol detected may have been an artifact of an abiotic reaction (19, 30).

Numerous studies have suggested that Geobacter species play an important role in the removal of aromatic hydrocarbons from contaminated aquifers, anaerobically oxidizing aromatic hydrocarbons to carbon dioxide with the reduction of Fe(III), which is abundant in many subsurface environments (6, 31–43). Recently two members of the Geobacteraceae family, Geobacter metallireducens and Geobacter sp. strain Ben, were shown to be capable of anaerobically metabolizing benzene (44). The development of methods for genetic manipulation of G. metallireducens (45) has made it possible to begin to evaluate the pathways for benzene metabolism with targeted gene deletions. Here we provide evidence from gene expression and gene deletion studies that indicate that G. metallireducens metabolizes benzene via a phenol intermediate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Geobacter metallireducens (ATCC 53774 and DSM 7210) (46) was obtained from our laboratory culture collection and was routinely cultured under strict anaerobic conditions with 50 mM Fe(III) citrate as the electron acceptor, as previously described (47). Unless otherwise noted, the electron donor (concentration) for growing cultures was benzene (0.25 mM), phenol (0.5 mM), benzoate (1 mM), toluene (0.5 mM), or acetate (10 mM). The exception to this was that in the studies in which phenol concentrations during growth on benzene were monitored, the initial concentration of benzene was 0.1 mM.

For control studies, G. sulfurreducens cultures that were grown with acetate (10 mM) as the electron donor and Fe(III) citrate (50 mM) as the electron acceptor served as the inoculum, and a 10% inoculum was transferred into medium with benzene (100 μM) and Fe(III) citrate (50 mM). The acetate remaining in the inoculum (ca. 4 mM) served as an additional electron donor.

Cell suspensions.

Studies of the metabolism of 14C- or 18O-labeled compounds were performed with cell suspensions to increase cell density and provide more rapid metabolic flux. Cells grown in acetate-Fe(III) citrate medium were concentrated under anaerobic conditions via centrifugation (4,400 × g for 10 min at 15°C). The cell pellets were washed with Fe(III) citrate medium devoid of an electron donor and then resuspended to provide a 30-fold concentration of cells. Aliquots (3 ml) of the cell suspension were incubated in 15-ml anaerobic pressure tubes. For studies on the origin of oxygen in phenol, H218O (95 atom% 18O; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was mixed with water to provide 9.5% H218O. Additions for 14C-labeled studies were 2.59 × 105 Bq [U-14C]benzene (39 μM, 2.78 × 109 Bq mmol−1; Moravek Biochemicals, Brea, CA), 2.22 × 105 Bq [U-14C]benzoate (40 μM, 2.22 × 109 Bq mmol−1; Moravek Biochemicals, Brea, CA), or 3.7 × 105 Bq [U-14C]phenol (44 μM, 2.96 × 109 Bq mmol−1; American Radiolabeled Chemicals Inc. [ARC], St. Louis, MO).

Analysis of gene expression.

Cells were grown in 1-liter bottles and harvested during mid-exponential phase by centrifugation. The cell pellet was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

RNA was isolated from triplicate cultures grown on each electron donor with a modification of a previously described method (17). Briefly, cell pellets were resuspended in HG extraction buffer (18) preheated to 65°C. The suspension was incubated for 10 min at 65°C to lyse the cells. Nucleic acids were isolated with a phenol-chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation. The pellet was washed twice with 70% ethanol, dried, and resuspended in sterile diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water. RNA was then purified with an RNA cleanup kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and treated with DNA-free DNase (Ambion, Woodward, TX). The RNA samples were tested for genomic DNA contamination by PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene. cDNA was generated with a TransPlex whole-transcriptome amplification kit (Sigma).

The sequences of all primers used for quantitative reverse transcription-PCR are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. Each reaction consisted of forward and reverse primers at a final concentration of 200 nM, 5 ng of cDNA, and 12.5 μl of Power SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primer pairs with amplicon sizes of 100 to 200 bp were designed for the following: bamY (Gmet 2143), ppsA (Gmet 2100), and bssA (Gmet 1539). Expression of these genes was normalized to the expression of proC, a gene shown to be constitutively expressed in Geobacter species (48). Relative levels of expression of the studied genes were calculated with the 2−ΔΔCT threshold cycle (CT) method (49).

Whole-genome microarray hybridizations were carried out by Roche NimbleGen, Inc. (Madison, WI). Triplicate biological and technical replicates were conducted for all microarray analyses. Cy3-labeled cDNA was hybridized to oligonucleotide microarrays based on the G. metallireducens genome and resident plasmid sequences (GenBank accession numbers NC_007515 and NC_007517). The microarray results were analyzed with Array 4 Star software (DNASTAR, Madison, WI). A gene was considered differentially expressed only if the P value determined by Student's t test analysis was less than or equal to 0.01.

Mutant construction and complementation studies.

Sequences for all primers used for construction of the mutants are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. Genomic DNA was extracted with an Epicentre MasterPure DNA purification kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI). Plasmids were extracted with a QIAprep Spin miniprep kit (Qiagen). PCR amplification was done with Taq polymerase (Qiagen). DNA gel purification was done with a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). Mutant alleles were constructed by replacing the coding sequences with a spectinomycin resistance cassette as described previously (45). Briefly, upstream and downstream flanking regions of the genes to be deleted (ca. 500 bp) were amplified with G. metallireducens genomic DNA as the template. PCR products were mixed, digested with AvrII (NEB, Beverly, MA), and ligated with the T4 DNA ligase (NEB). The resulting construct (ca. 1kb) was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO with a TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The spectinomycin resistance cassette with AvrII sites at both ends was amplified with pRG5 (50) as the template. The spectinomycin resistance cassette was AvrII digested and ligated into the AvrII site located between the flanking regions of the genes to be deleted.

The sequences of the mutant alleles were verified by Sanger sequencing. Plasmids bearing the mutant alleles were linearized by restriction enzyme digestion. The linearized plasmids were concentrated by ethanol precipitation. The linearized plasmids were electroporated into G. metallireducens as described earlier (45). The genotypes of the mutant strains were confirmed by PCR using the genomic DNA of the mutant strains as the template.

For complementation studies, ppsA and ppcB with their respective native ribosome binding sites (RBSs) were cloned under the control of a constitutive lac promoter into pCM66 (51).

Analytical techniques.

Fe(III) reduction was monitored by measuring the accumulation of Fe(II) over time with ferrozine, as previously described (52).

The benzene and toluene concentrations in the headspace were quantified with a gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector. The samples were run through a Supelco VOCOL fused silica capillary column (60 m by 0.25 mm by 1.5 μm) held at 50°C for 0.5 min, followed by an increase to 200°C at 10°C/min, as previously described (16). The concentrations of benzene in the aqueous phase were calculated with Henry's law using the constant at 25°C of 0.25 for benzene and 0.27 for toluene (53).

The acetate, benzoate, and phenol concentrations in the medium were measured with high-performance liquid chromatography as previously described (16). The [14C]carbon dioxide in the headspace was quantified with a gas proportional counter, as previously described (54, 55).

Samples (5 ml) of culture for analysis of transient phenol were collected over time from benzene-degrading cultures and immediately extracted with hexane (2 ml) by vigorous shaking for 2 min. Hexane extracts from unlabeled water and 18O experiments were immediately analyzed with a gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer (Shimadzu GCMS-QP2010Ultra). The injector port temperature was set at 250°C, and 1-μl sample extracts were injected through a SHRX1-5MS column (30 m by 0.25 mm by 0.25 μm) with the splitless mode. The column temperature was initially held at 60°C for 1 min, followed by an increase to 200°C at 4°C/min. Compounds were identified by comparison with chemical standards, and mass spectral data were characterized by comparison with data in the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) library.

Microarray data accession number.

Microarray data have been deposited with the NCBI GEO database under accession number GSE33794.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Detection of phenol as an intermediate in benzene metabolism.

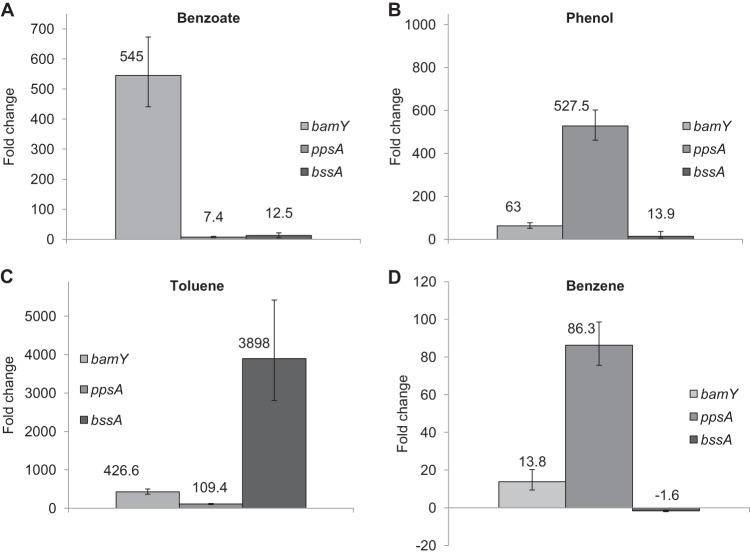

Small quantities of phenol but not benzoate were detected in cultures of G. metallireducens growing on benzene (Fig. 1), suggesting that G. metallireducens metabolized benzene via a phenol intermediate. It was previously suggested that phenol may be abiotically produced from benzene in the presence of iron (30), but this was not observed in subsequent studies with F. placidus (17). In order to further evaluate this possibility, an inoculum of G. sulfurreducens, a Geobacter species which cannot metabolize aromatic compounds (56), was grown in acetate-Fe(III) citrate medium, and a 10% inoculum of this culture was added to Fe(III) citrate medium that contained 100 μM benzene. The Fe(II) from the inoculum, as well as the Fe(II) produced from the residual acetate in the inoculum, ensured the presence of substantial (>7 mM) Fe(II), yet no phenol was detected over 27 days (Fig. 1). These results further demonstrate that phenol is not abiotically produced from benzene reacting with iron under the culture conditions employed.

Fig 1.

Transient phenol formation during anaerobic benzene degradation by G. metallireducens and a lack of phenol in cell-free and G. sulfurreducens controls. In the G. metallireducens culture, ca. 1.5 mM Fe(II) accumulated during the course of the incubation. The phenol results are the mean and standard deviation from triplicate cultures of each type.

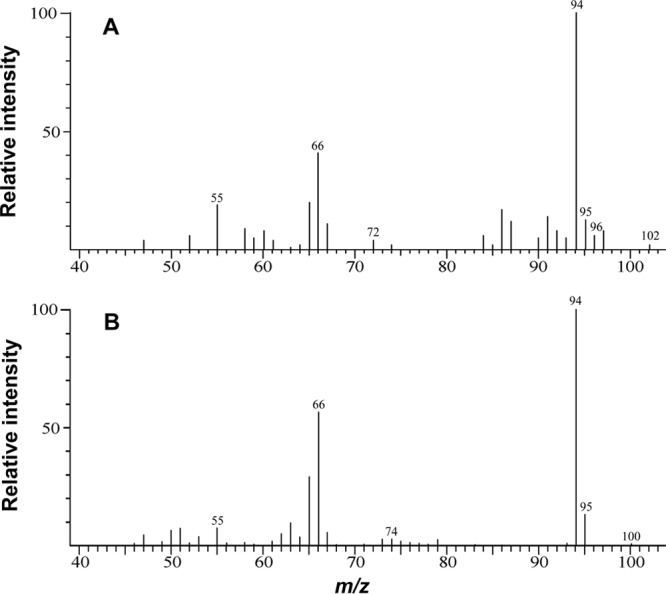

In order to investigate the source of oxygen for phenol production, cell suspensions were provided benzene and Fe(III) citrate in medium in which the water included 9.5% H218O (Fig. 2). The m/z 96 peak, representing 18O-labeled phenol, had a relative intensity that was 5% of the m/z 94 peak, representing unlabeled phenol (Fig. 2A). There was no m/z 96 peak when G. metallireducens was incubated in benzene medium without H218O (Fig. 2B). The production of 18O-labeled phenol suggested that the hydroxyl group introduced into benzene during benzene metabolism was derived from water. This result is consistent with the fact that G. metallireducens does not possess monooxygenase genes, which would be required for activation of benzene with molecular oxygen. These results, coupled with the fact that strict anaerobic culturing techniques and the presence of abundant Fe(II) in the cultures ensured that molecular oxygen was not available, suggested that the formation of phenol in benzene-degrading cultures was likely to be an anaerobic enzymatic reaction.

Fig 2.

Mass spectra of phenol produced during metabolism of benzene (250 μM) in 18O-labeled water (A) and unlabeled water (B).

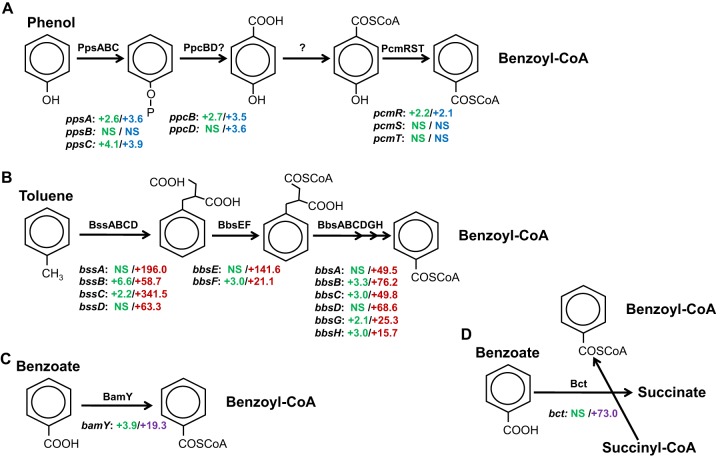

Differential expression of genes associated with possible benzene degradation pathways.

In order to gain additional insight into the pathway for benzene metabolism, the transcript abundance for genes coding for subunits of the enzymes catalyzing the first step of benzoate, phenol, or toluene metabolism was quantified with reverse transcription-quantitative PCR during growth with one of these aromatic compounds. Results were compared with expression during growth with acetate. As might be expected, each gene was the most highly expressed when its respective substrate was the electron donor that was added to support growth (Fig. 3). For example, bamY (Gmet 2143) encodes the benzoate coenzyme A (benzoate-CoA) ligase, an enzyme catalyzing the conversion of benzoate to benzoyl-CoA (57–59), and the transcript abundance of bamY was the highest during growth on benzoate (Fig. 3A). The transcript abundance for ppsA (Gmet 2100), which encodes the alpha subunit of phenylphosphate synthase, responsible for the conversion of phenol to phenylphosphate (60, 61), was the highest during growth on phenol (Fig. 3B). The transcript abundance of bssA (Gmet 1539), which encodes the alpha subunit of benzylsuccinate synthase, responsible for the activation of toluene with fumarate (60, 62), was the highest during growth on toluene (Fig. 3C).

Fig 3.

Relative transcript abundance of ppsA, bamY, and bssA during growth of G. metallireducens on benzoate (A), phenol (B), toluene (C), or benzene (D). The fold change shown is relative to the gene transcript abundance during growth on acetate, with gene expression normalized to that of the constitutively expressed gene proC. The results are the mean and standard deviation from triplicate cultures of each type.

As has previously been observed (63, 64), the genes for enzymes responsible for initiating the metabolism of benzoate, phenol, or toluene also had some increased expression during growth on the alternative aromatic compounds. This result demonstrates that the regulation of expression of aromatic degradation genes is not absolute but that relative gene expression levels might be diagnostic of the metabolic pathway employed.

During growth on benzene, the greatest increase in transcript abundance was for ppsA (Fig. 3D). There was a slight increase in transcript abundance for bamY, but this was much less than that in cells grown on any other aromatic compound. Transcript levels for bssA were comparable to those in acetate-grown cells. These results suggest that phenol, but not benzoate or toluene, is an intermediate in benzene degradation. The transcript abundance of ppsA was lower in the benzene-grown cells than in the phenol-grown cells, which may be linked to the higher phenol concentrations available to phenol-grown cells, as well as the greater phenol flux in phenol-grown cells, which grow much faster than benzene-grown cells.

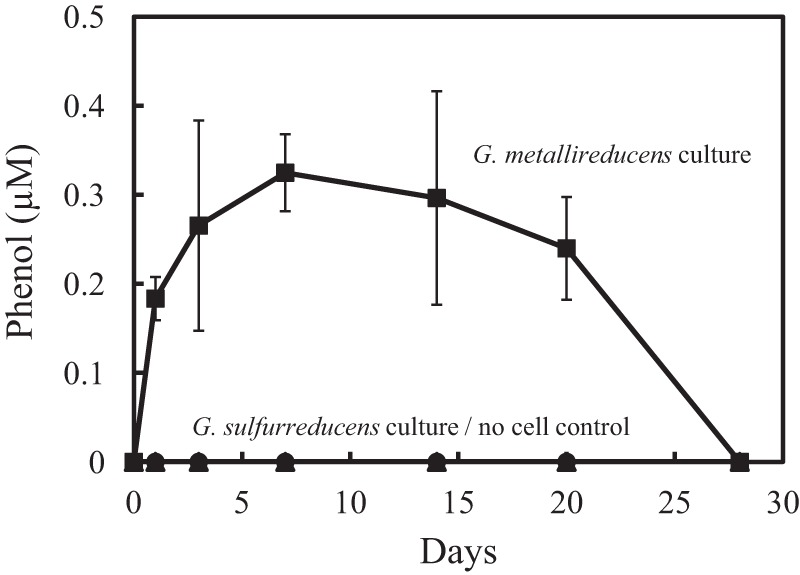

Subsequent genome-scale analysis of gene expression with whole-genome microarrays (NCBI GEO accession number GSE33794) revealed that genes for the putative phenol pathway in G. metallireducens that are upregulated in cells grown on phenol versus their regulation in cells gown on acetate are also upregulated during growth on benzene (Fig. 4A). The one exception was the gene for PpcD, which is thought to be a subunit in the enzyme phenylphosphate carboxylase (65). However, expression of the gene for the other subunit of this enzyme was upregulated in benzene-grown cells. Genes in the pathway for toluene degradation, which were highly upregulated in toluene-grown cells, had relatively little or no increase in transcript abundance in benzene-grown cells (Fig. 4B). In a similar manner, the microarray analysis confirmed the earlier findings from quantitative PCR analysis that bamY expression levels were much lower in benzene-grown cells than in cells metabolizing benzoate (Fig. 4C). Like bamY, bct (Gmet 2054), a gene coding for a succinyl-CoA:benzoate-CoA transferase involved in a recently discovered alternative mode of benzoate activation (66), was highly upregulated in benzoate-grown cells but not in cells grown on benzene (Fig. 4D). The results are consistent with a metabolism in which benzene is anaerobically hydroxylated to phenol, followed by a two-step carboxylation process to 4-hydroxybenzoate via phenylphosphate as an intermediate. 4-Hydroxybenzoate is further reductively converted via its coenzyme A ester to benzoyl-CoA. Free benzoate itself is not an expected intermediate.

Fig 4.

Transcriptomic analysis of benzene degradation in G. metallireducens evaluating expression for genes specifically involved in the phenol (A), toluene (B), or benzoate (C, D) degradation pathways. The numbers next to the gene designations represent the fold change in transcript abundance determined with microarray analyses in benzene- versus acetate-grown cells (green), phenol- versus acetate-grown cells (blue), toluene- versus acetate-grown cells (red), or benzoate- versus acetate-grown cells (violet). The results are the means of triplicate determinations from each of three replicate cultures. NS, no significant change in gene expression. COSCoA, carbon-oxygen-sulfur-coenzyme A.

Genetic evidence for benzene degradation via phenol.

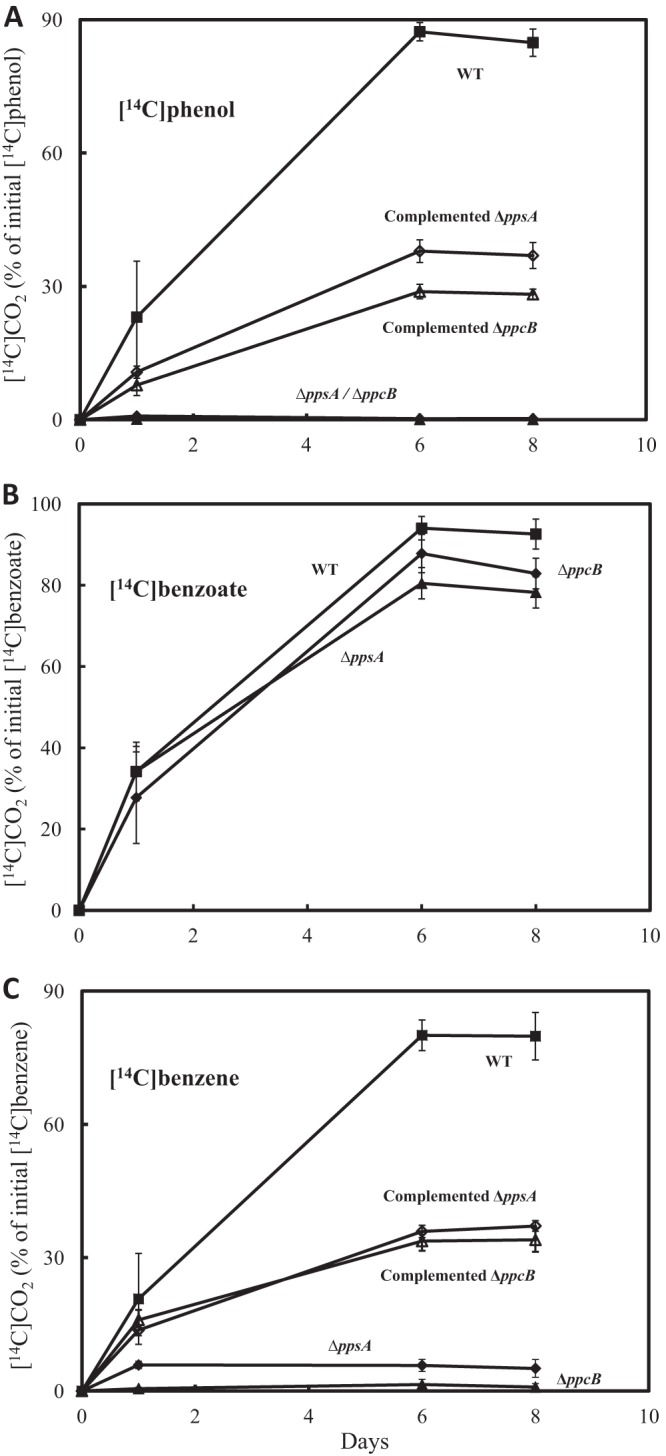

The possibility that benzene was metabolized via a phenol intermediate was further evaluated by deleting either ppsA, a gene predicted to encode a subunit for the enzyme necessary for the first step in phenol metabolism, or ppcB (65), a gene predicted to encode a subunit for the second step in phenol metabolism (Fig. 4). Cell suspensions of the wild-type strain readily utilized phenol, as expected (67), but cell suspensions of the ppsA- or ppcB-deficient strains could not (Fig. 5A), even though they metabolized benzoate as well as the wild type (Fig. 5B). Benzene oxidation was completely inhibited (Fig. 5C) in the absence of ppsA or ppcB. Complementation of either gene deletion by expression of the deleted gene on a plasmid restored the capacity for anaerobic phenol and benzene oxidation (Fig. 5). Rates of metabolism in the complemented strains were lower than those in the wild type, consistent with the general finding in previous studies with Geobacter species that the strategy for in trans expression does not yield wild-type activities when complementing deletions of genes for a wide variety of functions (45, 68–71). These results demonstrate that the phenol degradation pathway is essential for benzene degradation, further suggesting that phenol is an important intermediate in the metabolism of benzene.

Fig 5.

Production of 14CO2 from [14C]phenol (44 μM) (A), [14C]benzoate (40 μM) (B), and [14C]benzene (39 μM) (C) with in-cell suspensions of G. metallireducens wild-type (WT), ppsA mutant, ppcB mutant, complemented ppsA mutant, and complemented ppcB mutant strains. The results are the mean and standard deviation from triplicate cultures of each type.

Implications.

The results demonstrate that phenol is a key intermediate in the anaerobic degradation of benzene by Geobacter metallireducens. The specific upregulation of genes for phenol metabolism during growth on benzene and the finding that the capacity for anaerobic benzene metabolism is lost when genes for phenol metabolism are deleted indicate that phenol is produced from benzene. The incorporation of oxygen from water in phenol demonstrates that molecular oxygen is not involved in the benzene activation. Potential mechanisms for conversion of benzene to phenol, an endergonic reaction, have previously been proposed (7, 24), but unlike the clustering of genes for the degradation of other monoaromatic compounds (60), no genomic regions specific for benzene degradation have been identified through genome annotation or gene expression patterns. Thus, further speculation on activation mechanisms are not warranted at this time.

The production of phenol as an intermediate in anaerobic benzene degradation in G. metallireducens contrasts with the production of benzoate as an intermediate in the hyperthermophile Ferroglobus placidus (17). A highly enriched benzene-oxidizing, Fe(III)-reducing enrichment culture also appears to activate benzene via carboxylation (19, 30).

It seems likely that benzene conversion to phenol will be the major route for anaerobic benzene degradation in petroleum-contaminated environments in which Geobacter species are specifically enriched (37). The ability to discern pathways for anaerobic benzene degradation through analysis of gene transcript abundance in pure cultures, as demonstrated previously in studies with F. placidus (17) and in this study with G. metallireducens, might be extended with metatranscriptomic analysis to elucidate how benzene is anaerobically degraded in other environments.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Muktak Aklujkar and Trevor Woodward for assistance with data processing.

This research was supported by grant N00014-09-1-0190 from the Office of Naval Research.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 October 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03134-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vogt C, Kleinsteuber S, Richnow HH. 2011. Anaerobic benzene degradation by bacteria. Microb. Biotechnol. 4:710–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmona M, Zamarro MT, Blazquez B, Durante-Rodriguez G, Juarez JF, Valderrama JA, Barragan MJ, Garcia JL, Diaz E. 2009. Anaerobic catabolism of aromatic compounds: a genetic and genomic view. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 73:71–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foght J. 2008. Anaerobic biodegradation of aromatic hydrocarbons: pathways and prospects. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 15:93–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuchs G. 2008. Anaerobic metabolism of aromatic compounds. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1125:82–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson RT, Lovley DR. 2000. Anaerobic bioremediation of benzene under sulfate-reducing conditions in a petroleum-contaminated aquifer. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34:2261–2266 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson RT, Rooney-Varga JN, Gaw CV, Lovley DR. 1998. Anaerobic benzene oxidation in the Fe(III) reduction zone of petroleum contaminated aquifers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 32:1222–1229 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coates JD, Chakraborty R, McInerney MJ. 2002. Anaerobic benzene biodegradation—a new era. Res. Microbiol. 153:621–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lovley DR, Coates JD, Woodward JC, Phillips E. 1995. Benzene oxidation coupled to sulfate reduction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:953–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meckenstock RU, Mouttaki H. 2011. Anaerobic degradation of non-substituted aromatic hydrocarbons. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 22:406–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rooney-Varga JN, Anderson RT, Fraga JL, Ringelberg D, Lovley DR. 1999. Microbial communities associated with anaerobic benzene degradation in a petroleum-contaminated aquifer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3056–3063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiner JM, Lovley DR. 1998. Anaerobic benzene degradation in petroleum-contaminated aquifer sediments after inoculation with a benzene-oxidizing enrichment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:775–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiner JM, Lovley DR. 1998. Rapid benzene degradation in methanogenic sediments from a petroleum-contaminated aquifer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1937–1939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lovley DR, Woodward JC, Chapelle FH. 1996. Rapid anaerobic benzene oxidation with a variety of chelated Fe(III) forms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:288–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lovley DR, Woodward JC, Chapelle FH. 1994. Stimulated anoxic biodegradation of aromatic hydrocarbons using Fe(III) ligands. Nature 370:128–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lovley DR, Coates JD, Blunt-Harris EL, Phillips EJP, Woodward JC. 1996. Humic substances as electron acceptors for microbial respiration. Nature 382:445–448 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang T, Gannon SM, Nevin KP, Franks AE, Lovley DR. 2010. Stimulating the anaerobic degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons in contaminated sediments by providing an electrode as the electron acceptor. Environ. Microbiol. 12:1011–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmes DE, Risso C, Smith JA, Lovley DR. 2011. Anaerobic oxidation of benzene by the hyperthermophilic archaeon Ferroglobus placidus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:5926–5933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmes DE, Risso C, Smith JA, Lovley DR. 2012. Genome-scale analysis of anaerobic benzoate and phenol metabolism in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Ferroglobus placidus. ISME J. 6:146–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abu Laban N, Selesi D, Jobelius C, Meckenstock RU. 2009. Anaerobic benzene degradation by Gram-positive sulfate-reducing bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 68:300–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abu Laban N, Selesi D, Rattei T, Tischler P, Meckenstock R. 2010. Identification of enzymes involved in anaerobic benzene degradation by a strictly anaerobic iron-reducing enrichment culture. Environ. Microbiol. 12:2783–2796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caldwell ME, Suflita JM. 2000. Detection of phenol and benzoate as intermediates of anaerobic benzene biodegradation under different terminal electron-accepting conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34:1216–1220 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musat F, Widdel F. 2008. Anaerobic degradation of benzene by a marine sulfate-reducing enrichment culture, and cell hybridization of the dominant phylotype. Environ. Microbiol. 10:10–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phelps CD, Zhang X, Young LY. 2001. Use of stable isotopes to identify benzoate as a metabolite of benzene degradation in a sulphidogenic consortium. Environ. Microbiol. 3:600–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chakraborty R, Coates JD. 2005. Hydroxylation and carboxylation—two crucial steps of anaerobic benzene degradation by Dechloromonas strain RCB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5427–5432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coates JD, Chakraborty R, Lack JG, O'Connor SM, Cole KA, Bender KS, Achenbach LA. 2001. Anaerobic benzene oxidation coupled to nitrate reduction in pure culture by two strains of Dechloromonas. Nature 411:1039–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salinero KK, Keller K, Feil WS, Feil H, Trong S, Di Bartolo G, Lapidus A. 2009. Metabolic analysis of the soil microbe Dechloromonas aromatica str. RCB: indications of a surprisingly complex life-style and cryptic anaerobic pathways for aromatic degradation. BMC Genomics 10:351. 10.1186/1471-2164-10-351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weelink SAB, van Eekert MHA, Stams AJM. 2010. Degradation of BTEX by anaerobic bacteria: physiology and application. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 9:359–385 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ulrich AC, Beller HR, Edwards EA. 2005. Metabolites detected during biodegradation of 13C6-benzene in nitrate-reducing and methanogenic enrichment cultures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39:6681–6691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogel TM, Grbic-Galic D. 1986. Incorporation of oxygen from water into toluene and benzene during anaerobic fermentative transformation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 52:200–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunapuli U, Griebler C, Beller HR, Meckenstock RU. 2008. Identification of intermediates formed during anaerobic benzene degradation by an iron-reducing enrichment culture. Environ. Microbiol. 10:1703–1712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Botton S, van Harmelen M, Braster M, Parsons JR, Roling WF. 2007. Dominance of Geobacteraceae in BTX-degrading enrichments from an iron-reducing aquifer. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 62:118–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmes DE, O'Neil RA, Vrionis HA, N′Guessan AL, Ortiz-Bernad I, Larrahondo MJ, Adams LA, Ward JA, Nicoll JS, Nevin KP, Chavan MA, Johnson JP, Long PE, Lovley DR. 2007. Subsurface clade of Geobacteraceae that predominates in a diversity of Fe(III)-reducing subsurface environments. ISME J. 1:663–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hosoda A, Kasai Y, Hamamura N, Takahata Y, Watanabe K. 2005. Development of a PCR method for the detection and quantification of benzoyl-CoA reductase genes and its application to monitored natural attenuation. Biodegradation 16:591–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kane SR, Beller HR, Legler TC, Anderson RT. 2002. Biochemical and genetic evidence of benzylsuccinate synthase in toluene-degrading, ferric iron-reducing Geobacter metallireducens. Biodegradation 13:149–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuntze K, Vogt C, Richnow HH, Boll M. 2011. Combined application of PCR-based functional assays for the detection of aromatic-compound-degrading anaerobes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:5056–5061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lovley DR, Baedecker MJ, Lonergan DJ, Cozzarelli IM, Phillips EJP, Siegel DI. 1989. Oxidation of aromatic contaminants coupled to microbial iron reduction. Nature 339:297–300 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lovley DR, Ueki T, Zhang T, Malvankar NS, Shrestha PM, Flanagan K, Aklujkar M, Butler JE, Giloteaux L, Rotaru AE, Holmes DE, Franks AE, Orellana R, Risso C, Nevin KP. 2011. Geobacter: the microbe electric's physiology, ecology, and practical applications. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 59:1–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Röling WF, van Breukelen BM, Braster M, Lin B, van Verseveld HW. 2001. Relationships between microbial community structure and hydrochemistry in a landfill leachate-polluted aquifer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4619–4629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snoeyenbos-West OL, Nevin KP, Anderson RT, Lovley DR. 2000. Enrichment of Geobacter species in response to stimulation of Fe(III) reduction in sandy aquifer sediments. Microb. Ecol. 39:153–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Staats M, Braster M, Rölling WF. 2011. Molecular diversity and distribution of aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading anaerobes across a landfill leachate plume. Environ. Microbiol. 13:1216–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tobler NB, Hofstetter TB, Straub KL, Fontana D, Schwarzenbach RP. 2007. Iron-mediated microbial oxidation and abiotic reduction of organic contaminants under anoxic conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41:7765–7772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winderl C, Anneser B, Griebler C, Meckenstock RU, Lueders T. 2008. Depth-resolved quantification of anaerobic toluene degraders and aquifer microbial community patterns in distinct redox zones of a tar oil contaminant plume. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:792–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yun J, Ueki T, Miletto M, Lovley DR. 2011. Monitoring the metabolic status of Geobacter species in contaminated groundwater by quantifying key metabolic proteins with Geobacter-specific antibodies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:4597–4602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang T, Bain TS, Nevin KP, Barlett MA, Lovley DR. 2012. Anaerobic benzene oxidation by Geobacter species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:8304–8310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tremblay PL, Aklujkar M, Leang C, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. 2012. A genetic system for Geobacter metallireducens: role of the flagellin and pilin in the reduction of Fe(III) oxide. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 4:82–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lovley DR, Giovannoni SJ, White DC, Champine JE, Phillips EJP, Gorby YA, Goodwin S. 1993. Geobacter metallireducens gen. nov. sp. nov., a microorganism capable of coupling the complete oxidation of organic compounds to the reduction of iron and other metals. Arch. Microbiol. 159:336–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lovley DR, Phillips EJ. 1988. Novel mode of microbial energy metabolism: organic carbon oxidation coupled to dissimilatory reduction of iron or manganese. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:1472–1480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holmes DE, Nevin KP, O'Neil RA, Ward JE, Adams LA, Woodard TL, Vrionis HA, Lovley DR. 2005. Potential for quantifying expression of the Geobacteraceae citrate synthase gene to assess the activity of Geobacteraceae in the subsurface and on current-harvesting electrodes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:6870–6877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim BC, Leang C, Ding YH, Glaven RH, Coppi MV, Lovley DR. 2005. OmcF, a putative c-type monoheme outer membrane cytochrome required for the expression of other outer membrane cytochromes in Geobacter sulfurreducens. J. Bacteriol. 187:4505–4513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marx CJ, Lidstrom ME. 2001. Development of improved versatile broad-host-range vectors for use in methylotrophs and other Gram-negative bacteria. Microbiology 147:2065–2075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lovley DR, Phillips EJ. 1986. Organic matter mineralization with reduction of ferric iron in anaerobic sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 51:683–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Staudinger J, Roberts PV. 1996. A critical review of Henry's law constants for environmental applications. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 26:205–297 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Coates JD, Woodward J, Allen J, Philp P, Lovley DR. 1997. Anaerobic degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkanes in petroleum-contaminated marine harbor sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3589–3593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hayes LA, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. 1999. Role of prior exposure on anaerobic degradation of naphthalene and phenanthrene in marine harbor sediments. Org. Geochem. 30:937–945 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Caccavo F, Jr, Lonergan DJ, Lovley DR, Davis M, Stolz JF, McInerney MJ. 1994. Geobacter sulfurreducens sp. nov., a hydrogen- and acetate-oxidizing dissimilatory metal-reducing microorganism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3752–3759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Egland PG, Gibson J, Harwood CS. 1995. Benzoate-coenzyme A ligase, encoded by badA, is one of three ligases able to catalyze benzoyl-coenzyme A formation during anaerobic growth of Rhodopseudomonas palustris on benzoate. J. Bacteriol. 177:6545–6551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schühle K, Gescher J, Feil U, Paul M, Jahn M, Schagger H, Fuchs G. 2003. Benzoate-coenzyme A ligase from Thauera aromatica: an enzyme acting in anaerobic and aerobic pathways. J. Bacteriol. 185:4920–4929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wischgoll S, Heintz D, Peters F, Erxleben A, Sarnighausen E, Reski R, Van Dorsselaer A, Boll M. 2005. Gene clusters involved in anaerobic benzoate degradation of Geobacter metallireducens. Mol. Microbiol. 58:1238–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Butler JE, He Q, Nevin KP, He Z, Zhou J, Lovley DR. 2007. Genomic and microarray analysis of aromatics degradation in Geobacter metallireducens and comparison to a Geobacter isolate from a contaminated field site. BMC Genomics 8:180. 10.1186/1471-2164-8-180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmeling S, Narmandakh A, Schmitt O, Gad'on N, Schuhle K, Fuchs G. 2004. Phenylphosphate synthase: a new phosphotransferase catalyzing the first step in anaerobic phenol metabolism in Thauera aromatica. J. Bacteriol. 186:8044–8057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leuthner B, Leutwein C, Schulz H, Horth P, Haehnel W, Schiltz E, Schagger H, Heider J. 1998. Biochemical and genetic characterization of benzylsuccinate synthase from Thauera aromatica: a new glycyl radical enzyme catalysing the first step in anaerobic toluene metabolism. Mol. Microbiol. 28:615–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peters F, Heintz D, Johannes J, van Dorsselaer A, Boll M. 2007. Genes, enzymes, and regulation of para-cresol metabolism in Geobacter metallireducens. J. Bacteriol. 189:4729–4738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schleinitz KM, Schmeling S, Jehmlich N, von Bergen M, Harms H, Kleinsteuber S, Vogt C, Fuchs G. 2009. Phenol degradation in the strictly anaerobic iron-reducing bacterium Geobacter metallireducens GS-15. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:3912–3919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schuhle K, Fuchs G. 2004. Phenylphosphate carboxylase: a new C-C lyase involved in anaerobic phenol metabolism in Thauera aromatica. J. Bacteriol. 186:4556–4567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oberender J, Kung JW, Seifert J, von Bergen M, Boll M. 2012. Identification and characterization of a succinyl-coenzyme A (CoA):benzoate CoA transferase in Geobacter metallireducens. J. Bacteriol. 194:2501–2508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lovley DR, Lonergan DJ. 1990. Anaerobic oxidation of toluene, phenol, and p-cresol by the dissimilatory iron-reducing organism, GS-15. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1858–1864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leang C, Coppi MV, Lovley DR. 2003. OmcB, a c-type polyheme cytochrome, involved in Fe(III) reduction in Geobacter sulfurreducens. J. Bacteriol. 185:2096–2103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mehta T, Coppi MV, Childers SE, Lovley DR. 2005. Outer membrane c-type cytochromes required for Fe(III) and Mn(IV) oxide reduction in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8634–8641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reguera G, McCarthy KD, Mehta T, Nicoll JS, Tuominen MT, Lovley DR. 2005. Extracellular electron transfer via microbial nanowires. Nature 435:1098–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smith JA, Lovley DR, Tremblay PL. 2013. Outer cell surface components essential for Fe(III) oxide reduction by Geobacter metallireducens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79:901–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.