Abstract

The survival of microorganisms in ancient glacial ice and permafrost has been ascribed to their ability to persist in a dormant, metabolically inert state. An alternative possibility, supported by experimental data, is that microorganisms in frozen matrices are able to sustain a level of metabolic function that is sufficient for cellular repair and maintenance. To examine this experimentally, frozen populations of Psychrobacter arcticus 273-4 were exposed to ionizing radiation (IR) to simulate the damage incurred from natural background IR sources in the permafrost environment from over ∼225 kiloyears (ky). High-molecular-weight DNA was fragmented by exposure to 450 Gy of IR, which introduced an average of 16 double-strand breaks (DSBs) per chromosome. During incubation at −15°C for 505 days, P. arcticus repaired DNA DSBs in the absence of net growth. Based on the time frame for the assembly of genomic fragments by P. arcticus, the rate of DNA DSB repair was estimated at 7 to 10 DSBs year−1 under the conditions tested. Our results provide direct evidence for the repair of DNA lesions, extending the range of complex biochemical reactions known to occur in bacteria at frozen temperatures. Provided that sufficient energy and nutrient sources are available, a functional DNA repair mechanism would allow cells to maintain genome integrity and augment microbial survival in icy terrestrial or extraterrestrial environments.

INTRODUCTION

The results from decades of studying the stability of DNA in bacteria may be summarized in two uncomplicated axioms. First, genomic DNA is not inert; the genetic material will degrade with time, and damage will accumulate unless that degradation is repaired. And second, if this degradation is not reversed, the cell will die. The repair processes that cope with DNA damage are integral to life, and it is assumed that all species express means of maintaining genetic integrity.

The importance of DNA repair to cell viability motivated extensive study of the biochemistry and molecular biology of these repair processes in model organisms such as Escherichia coli (1). Although the advantages of using this species for such studies are well documented, there is a question as to whether detailed knowledge of DNA repair in E. coli as observed under standard laboratory conditions adequately represents the full spectrum of bacterial responses to DNA damage. For instance, DNA repair is an energy-intensive activity (2, 3), but microbial species in nature rarely experience optimal conditions for growth or have access to nutrient excess. Without a generous supply of energy, cells may need to generate a more measured response, rationing available resources in a manner that prioritizes the most important tasks for survival. Moreover, viability in the absence of cellular reproduction is sustained only by cells that do not accumulate a level of damage (e.g., to DNA) that exceeds a threshold beyond which effective repair is no longer possible.

Genomic DNA and viable bacteria are preserved in ancient ice and permafrost for hundreds of thousands to millions of years (4–8). The presence of a solute-rich liquid phase within the ice matrix has been argued to be a habitat suitable for microorganisms (9–11). Furthermore, experimental data support the hypothesis that certain bacteria and fungi are metabolically active under frozen conditions (12), and there is currently no evidence for a minimum temperature threshold for metabolism (13). Amato et al. (14) argued that the low rates of DNA synthesis observed in bacteria at −15°C would be sufficient to offset DNA damage incurred by natural background ionizing radiation (IR) over geological timescales. Additionally, Johnson et al. (8) found microbial DNA preserved in permafrost samples as old as 600 kiloyears (ky) and speculated that active DNA repair by certain bacterial phyla was the most likely explanation for the DNA integrity observed.

Information on the metabolic capabilities of microorganisms at very low temperatures has provided a new perspective on microbial survival strategies in the Earth's cryosphere (12, 15, 16); however, specific knowledge about their physiology under frozen conditions is still very limited. More precisely, while it is clear that DNA damage and repair are highly relevant to microbial survival, it is not known if microorganisms have the capacity to repair DNA damage under the conditions existing in an ice matrix (i.e., high ionic strength and low water activity and temperature). Here we report on experiments in which populations of Psychrobacter arcticus 273-4 were exposed to IR, and subsequently, the cells repaired lesions in their genomic DNA at −15°C. We discuss the broader relevance of how a functional pathway of double-strand break (DSB) repair would be superior to dormancy in alleviating the problem of incurring formidable damage to DNA over extended time frames and contribute to microbial persistence in glacial ice and permafrost environments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strain and culture conditions.

Pure cultures of Psychrobacter arcticus 273-4 (DSM 17307; equivalent to VKM B-2377) were grown aerobically with shaking (200 rpm) at 22°C in R2A broth (17). Cells from the mid-exponential phase were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g, washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2), and suspended in either PBS or 0.8% R2A broth. The viable cell concentration in each sample was determined by standard dilution plating.

Cells for the DNA repair experiments were suspended in an ice-cold R2A medium that was diluted to 0.8% of the standard recipe (i.e., a final concentration of ∼10 mg C liter−1). Triplicate samples were prepared for each time point and assay. One- or two-milliliter samples of the cell suspensions were frozen by transferring the tubes to a −80°C freezer and storing the samples for at least 16 h. After exposure to IR, the samples were transferred to a −15 ± 1°C incubator (Thermo Scientific Revco ULT model 350-3-A32 freezer) for up to 505 days. At each experimental time point, the viable cell count was determined using standard dilution plating; dilutions were performed in PBS, and the number of CFU was determined in triplicate following incubation at 22°C for 3 days on R2A medium solidified with 1.5% agar.

Exposure to ionizing radiation.

To establish the sensitivity of P. arcticus to IR, cells suspended in PBS were exposed to IR at a rate of 5.0 ± 0.14 Gy min−1 for 30, 60, and 90 min at 22°C, using a 60Co irradiator (model 484; J. L. Sheppard and Associates). The dose rate was directly measured by Fricke dosimetry (18). Survival was determined at each time point by triplicate serial dilution plating of the samples on agar-solidified R2A medium. The surviving fraction at each dose was calculated by dividing the average number of CFU formed postirradiation by the number of CFU in the control. The dose response of P. arcticus to IR was expressed as the D37 value (i.e., the dose at which 37% of the cells survived) and was calculated from the slope of the survival curve (Fig. 1).

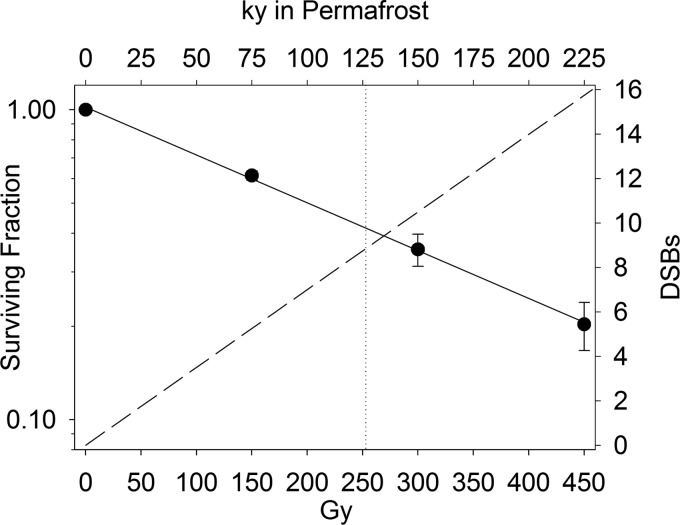

Fig 1.

Survival curve of Psychrobacter arcticus as a function of ionizing radiation (IR) dose on a logarithmic scale. Data points represent means and standard deviations for triplicate plate counts. The dotted vertical line represents the D37 value, and the dashed line represents average numbers of double-strand breaks (DSBs) introduced into the genome of P. arcticus. The upper x axis shows the predicted time frame in permafrost to receive the IR doses applied in this study, based on the measurements of McKay (2 mGy year−1) (37).

Individual samples (n = 48) of the frozen cell suspensions were placed in a glass beaker, overlain with dry ice, and transported from the −80°C freezer to the 60Co irradiator in an insulated cooler containing ice packs chilled to −80°C. In the irradiation chamber, the beaker was surrounded by the ice packs to keep the samples at low temperature during irradiation. Cell populations of P. arcticus were exposed to 450 Gy of IR, and all samples remained frozen during the 90-min exposure. Identical samples that were not irradiated served as controls. After irradiation, the tubes were sorted and boxed within a −20°C walk-in freezer and were transferred to a −15 ± 1°C incubator at <0.5 h postirradiation.

DNA extraction and PFGE.

At each experimental time point, three samples were removed from the freezer, melted at 22°C, and immediately prepared for DNA extraction. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, suspended in a prewarmed buffer (50°C; 10 mM Tris, 50 mM EDTA, 20 mM NaCl; pH 7.2), and embedded in 1.6% low-melting-point agarose (50°C; 1% final concentration) within 15 min of removal from the freezer. To enhance polymerization, the plugs were incubated at 4°C for 10 min. Cell lysis was performed by placing the low-melting-point agarose plugs in a 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0) solution containing 1 mg ml−1 proteinase K, 1% (wt/vol) lauroyl sarcosine, and 1% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate and incubating them for 24 h at 50°C. After lysis, the plugs were washed twice in 5 ml of deionized water and four times in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) for 30 min with agitation. A 2-mm slice was cut from each plug, and the chromosomal DNA was digested with 25 units of NotI in 1× RE buffer (60 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 1.5 M NaCl, 60 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol) supplemented with bovine serum albumin (BSA; final concentration, 0.1 mg ml−1) (all from Promega) for 48 h at 50°C. After restriction enzyme digestion, the plugs were washed twice in 5 ml of TE buffer as described above. A DNA standard (Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosomal DNA; Lonza) was included to facilitate sizing of the fragments and comparisons of migration patterns between individual gels. High-molecular-weight DNAs were separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) on a 1% agarose gel containing 0.5× TBE (45 mM Tris-borate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) at 6 V cm−1, with a 120° angle and a ramp switch time from 50 to 90 s over 26 h at 12°C. The separated DNAs were visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. The gel was digitally photographed, and electropherograms were obtained and analyzed with the Bio-Rad Quantity One (version 4.2) software package. Background was subtracted using the software's rolling disk method, and the width and height of the automatically detected peaks were adjusted manually (Quantity One user guide for version 4, Bio-Rad). The shape of each band conformed to a Gaussian model, which was used to mathematically describe the PFGE profiles. The data from each electropherogram were normalized to the highest pixel intensity (i.e., expressed as 100% intensity), allowing individual peaks to be distinguished and compared more easily.

The frequency at which DNA DSBs were generated in the 2.65-Mb genome of P. arcticus (19) was estimated based on a rate of 1 DSB per 10 Gy per 5 × 109 Da of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) (20). In the case of P. arcticus, 29 Gy would generate one DSB per chromosome, and 450 Gy (i.e., the experimental dosage) would introduce 16 DSBs. Similarly, the average number of DSBs that would be expected in each NotI restriction product was calculated (Table 1). The kinetics of DNA repair was determined using the time-dependent appearance of intact chromosomal fragments in the electropherograms. Using this approach, the average cumulative number of DSBs repaired from triplicate samples was calculated at each time point. For example, if an average of 16 DSBs must be repaired to assemble the 2.65-Mb P. arcticus chromosome, then the repair of 6 DSBs would be required for a DNA fragment of 0.997 Mb (Table 1, data for band 7). The rate of DSB repair was determined from the slope of a fitted linear regression model. To represent the variability observed between sample replicates, the minimum and maximum numbers of DNA DSBs repaired by 505 days were used to calculate low and high rate estimates for the number of DNA DSBs repaired.

Table 1.

Predicted sizes of NotI restriction fragments of the Psychrobacter arcticus chromosome and estimated average numbers of DNA DSBs introduced into each region after exposure to 450 Gy of ionizing radiation

| Band | Fragment size (kb) | Avg no. of DNA DSBs |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 33 | <1 |

| 2 | 114 | <1 |

| 3 | 229 | 1 |

| 4 | 305 | 2 |

| 5 | 375 | 2 |

| 6 | 598 | 4 |

| 7 | 997 | 6 |

| Genome | 2,650 | 16 |

RESULTS

The survival of P. arcticus after exposure to 150, 300, and 450 Gy of IR followed an exponential-decay function (Fig. 1). From these data, the D37 of P. arcticus was determined to be 253 Gy, which represents the dosage at which each cell, on average, experienced a lethal event. The D37 dosage corresponded to the formation of an average of 9 DSBs, and based on the linear accumulation of DNA DSBs (i.e., 1 DSB per 10 Gy per 5 × 109 Da of dsDNA [20]), 16 DSBs, on average, were introduced into the chromosome of P. arcticus after exposure to 450 Gy of IR (Fig. 1).

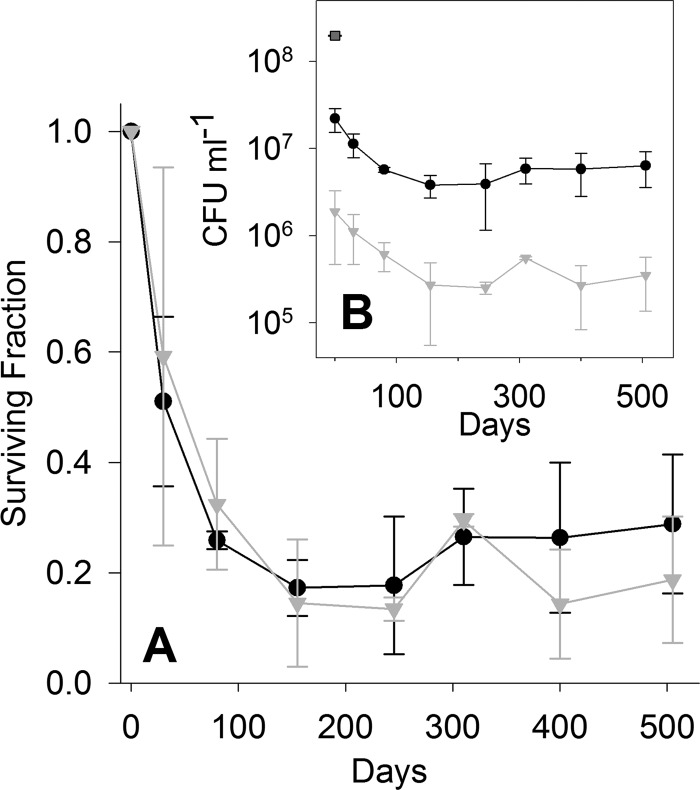

A 9-fold reduction in culturability of P. arcticus cells occurred as a result of freezing in low-nutrient medium (0.8% R2A medium) at −80°C and thawing at 22°C (Fig. 2B). The additive effect of exposure to 450 Gy reduced the P. arcticus population an additional 12-fold (Fig. 2B). Long-term incubation at −15°C showed no measureable difference in culturability of irradiated and control samples (unpaired two-tailed t test; P > 0.369). Cell survival over 505 days at −15°C was biphasic, with an initial 80-day exponential decay in which approximately 80% of the population lost culturability, followed by a plateau in the residual fraction (Fig. 2A). The data from the irradiated and control samples between 80 and 505 days were not statistically different (one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]; P > 0.161), indicating that a subpopulation of the cells (∼20%) were more resistant to the effects of storage at −15°C.

Fig 2.

Effect of freezing on survival of control (●) and irradiated (▼) (450 Gy) cell suspensions of Psychrobacter arcticus incubated at −15°C for 505 days. The data are shown as fractions of culturable cells (A) and numbers of CFU ml−1 (B), with the square (■) representing the CFU ml−1 prior to freezing and irradiation. Error bars represent standard deviations from the means for triplicate measurements.

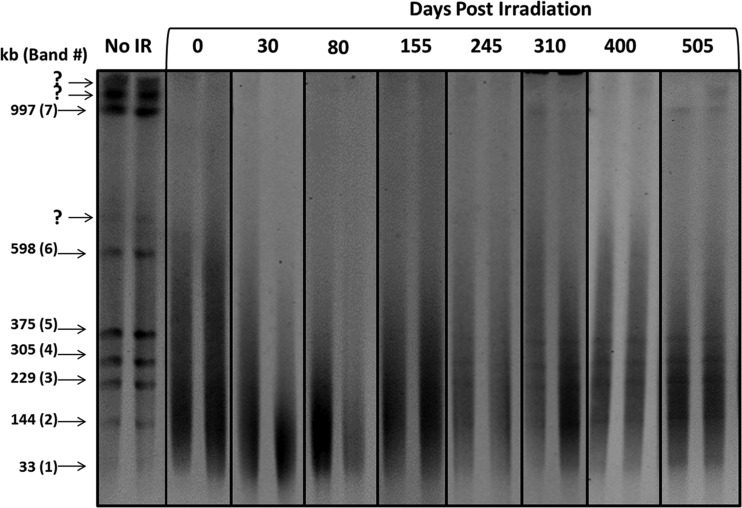

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis was used to visualize high-molecular-weight DNA molecules isolated from populations of P. arcticus (Fig. 3). Digestion of the chromosomal DNA with NotI facilitated the movement of large-molecular-weight DNA into the gel and provided a means of monitoring the reassembly of chromosomal DNA following the introduction of IR-induced DSBs. Restriction of the intact chromosome with NotI generated seven fragments (Fig. 3 and 4A) that corresponded in size to predictions based on the genome sequence. The lowest-molecular-weight band (33 kb) was difficult to resolve under the electrophoretic conditions used. In addition to the seven expected genome fragments, three additional bands (700, 1,600, and 2,200 kb) (Fig. 3) were regularly observed that were consistent with incompletely digested products (e.g., bands 4 and 5 are neighboring fragments on the chromosome that together form an ∼700-kb molecule). Exposure to 450 Gy of IR led to a drastic change in the pattern of P. arcticus genome fragments as observed by PFGE, reducing the resolvable chromosomal DNA to a population of molecules between 30 and 200 kb (Fig. 3 and 4A). This was consistent with dose-rate calculations that predicted the introduction of 16 DSBs into the 2.65-Mb chromosome of P. arcticus, producing an average fragment size of ∼170 kb. Based on the size of each NotI fragment, the average numbers of DSBs introduced after exposure to 450 Gy ranged from less than one to six DSBs (Table 1).

Fig 3.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of NotI-restricted genomic DNA from Psychrobacter arcticus after exposure to 450 Gy of IR and subsequent incubation at −15°C. Fragment sizes in kilobases (kb) and number designations of the NotI-digested bands (1 to 7) are given on the left. The question marks indicate incompletely digested DNA fragments. No IR, chromosomal DNAs from frozen samples that were not exposed to IR. Samples irradiated with 450 Gy and examined after 0, 30, 80, 155, 245, 310, 400, and 505 days of frozen incubation are indicated. Duplicate samples are shown for each time point. Each picture is a negative image of an ethidium bromide-stained gel.

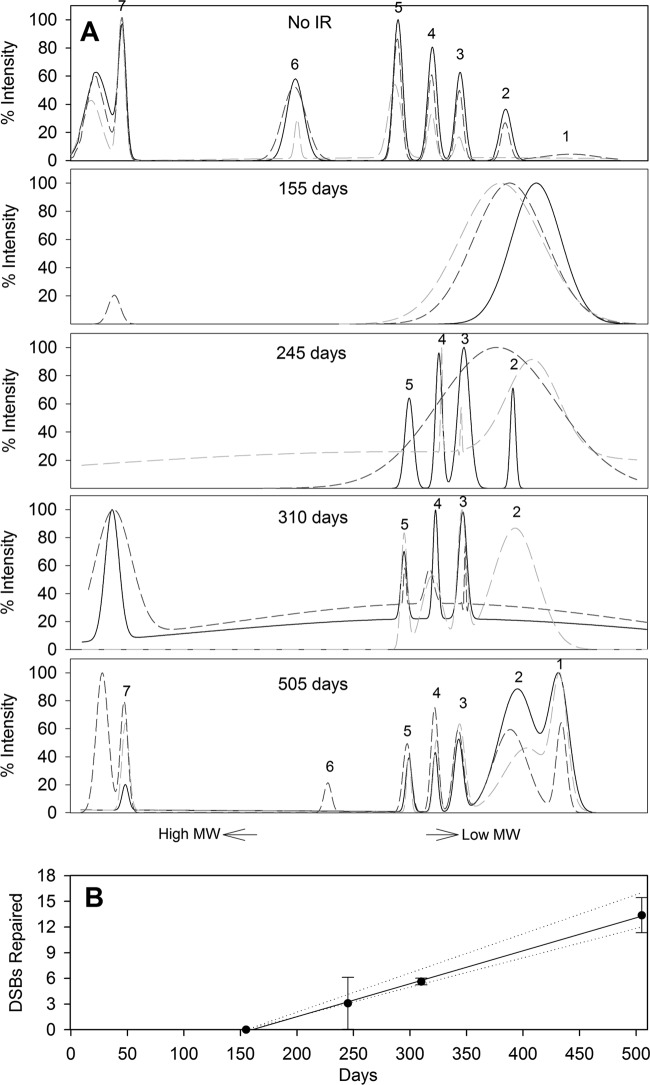

Fig 4.

(A) Pulsed-field gel electropherograms from a Psychrobacter arcticus population after exposure to 450 Gy of IR and long-term incubation at −15°C. Each time point consists of 3 plots derived from independent samples. Labels 1 to 7 indicate the resolvable NotI digestion fragments and coincide with the band designations in Table 1 and Fig. 3. (B) DNA DSB repair kinetics. Solid line, regression line for DSBs repaired, with standard deviations of the data (error bars); dotted lines, range of DSBs repaired, based on the minimum and maximum numbers of NotI bands observed after 505 days. MW, molecular weight.

During the first 155 days, the DNA remained fragmented, migrating as a low-molecular-weight smear (Fig. 3). Bands 3 to 5, corresponding to the smaller NotI chromosomal fragments (229, 305, and 375 kb), appeared in some PFGE profiles at 245 days, and by 310 days, these fragments were clearly resolved in all replicates (Fig. 3 and 4A). Although bands 1 and 2 (33 and 114 kb) could be visualized by PFGE, they were masked in the electropherograms due to the weak contrast between the fragments and the large pool of low-molecular-weight DNA. Since NotI fragments 1 to 5 (33 to 375 kb) required an average of two or fewer DSB repair events for reassembly (Table 1), these were the first genome segments observed, as would be expected if active DNA repair was occurring. The two highest-molecular-weight bands (598 and 997 kb) were not observed before 505 days (Fig. 3 and 4A).

The electropherograms generated from the PFGE images were used to construct Gaussian models (Fig. 4A) that characterized each band and aided in describing the kinetics of DNA DSB repair (Fig. 4B). After 155 days of incubation at −15°C, measureable repair and reassembly of damaged chromosomes had occurred. Using the cumulative number of DNA DSBs repaired in triplicate samples from each time point, averages of 3, 6, and 13 DSBs were repaired after 245, 310, and 505 days, respectively (Fig. 4B). From the slope of the linear regression, a repair rate of 8 DSBs year−1 was calculated. Also shown in Fig. 4B are rates of DSB repair based on the minimum and maximum numbers of DNA DSBs repaired in each replicate after 505 days (dotted lines). Either six or seven NotI fragments were observed after 505 days (Fig. 4A), corresponding to the repair of 12 and 16 DSBs, respectively. Based on these data, we infer that P. arcticus repaired between 7 and 10 DSBs year−1 under the conditions tested.

DISCUSSION

P. arcticus was isolated from a Siberian permafrost horizon that had been frozen for 20 to 30 ky at temperatures of −10 to −12°C (21). Subsequently, this species has provided valuable insight into the growth (22), genomic composition (19), and gene expression (23) of permafrost bacteria, as well as the effect of low water activity (24) on these bacteria. P. arcticus has one of the coldest reported growth temperatures (−10°C) (25), which is eclipsed only by those of Psychromonas ingrahamii 37 (−12°C) (26), Colwellia psychrerythraea strain 34H (−12°C) (27), and Planococcus halocryophilus Or1 (−15°C) (28). The genome of P. arcticus encodes a complete complement of proteins involved in canonical bacterial DNA repair, including base excision repair, nucleotide excision repair, mismatch repair, and homologous recombination (HR) (19). Given the opportunity to function, these proteins should be capable of efficiently dealing with DNA damage as it appears. Survival in ancient permafrost and the capacity to grow and metabolize at subzero temperatures (14, 24, 25) were thus the primary rationales for using P. arcticus as a model for examining if bacteria can repair their DNA under conditions physicochemically similar to those found in situ, i.e., low temperature and organic carbon concentrations (total of ∼10 mg C liter−1) similar to values reported for permafrost (29, 30).

Exposure to 450 Gy of IR introduced an average of 16 DSBs into the P. arcticus genome, as well as other forms of DNA damage not detectable by PFGE (e.g., single-strand lesions and damage to nitrogenous bases), and led to a 12-fold reduction in the number of CFU ml−1. This dose was empirically determined to be the minimum exposure that created sufficient DSB damage to eliminate the resolvable NotI fragments (Fig. 3). The data from Fig. 3 and 4 imply that reassembly of damaged chromosomal DNA did not proceed immediately after exposure to IR, with a linear rate of DSB repair detected only after 155 days of incubation at −15°C (Fig. 4B). The time frame for the initiation of genome assembly coincided with a period in which the number of CFU stabilized and remained statistically unchanged for ∼350 days (Fig. 2). Although the repair of DSBs had no appreciable effect on cell culturability (Fig. 2), the sublethally damaged cells were assayed by plating on culture medium, which would have provided the opportunity for them to repair their DNA prior to initiating colony formation. This result brings a new perspective to the observations of Alur and Grecz (31) and Grecz et al. (32), who incubated cell suspensions of E. coli for up to 12 months at −20°C and demonstrated that freezing caused single- and double-strand breaks in the genome which were associated with decreased survival. Unexpectedly, it was observed that the extent of DSBs began to decrease after 4 months postfreezing, and the authors speculated that “random reassociation and aggregation of the initial DNA fragments” was the most likely explanation for the results (32). Whether or not the DNA repair activity we observed is a property exclusive to cold-adapted species or is more broadly distributed in the microbial world represents fertile territory for further study.

The major, ubiquitous pathway of DNA DSB repair in bacteria is homologous recombination (HR) (33). Some species (e.g., Bacillus subtilis) also possess a rudimentary analog to the eukaryotic nonhomologous end-joining pathway (NHEJ) (34), and a modified version of NHEJ, named alternative end joining (A-EJ), exists in E. coli (35). Recently, genome condensation under stress conditions was suggested as an additional DSB repair mechanism that operates in E. coli (36). Of these DNA DSB repair mechanisms, only genes involved in HR pathways have been identified in the P. arcticus genome (19). The P. arcticus inoculum used in our experiments was harvested from the exponential phase of growth, and despite the removal of nutrients, DNA repair enzymes and parental scaffolds for HR could have existed.

Amato et al. (14) examined DNA synthesis in frozen samples of P. arcticus incubated with various nutrient amendments and measured rates at −15°C that ranged from 20 to 1,625 bp cell−1 day−1. Although their study did not specifically examine DNA repair, it was concluded that if suitable nutrients and redox couples were present, such a rate of DNA metabolism would be adequate for offsetting the DNA damage incurred from natural and cosmic sources of IR in terrestrial and extraterrestrial permafrost. Based on IR dose values in Siberian permafrost (∼2 mGy year−1) (37), each cell in a dormant P. arcticus population would incur an average of one DSB every 14,500 years, and the D37 would be reached in 126,500 years (Fig. 1). As an extreme comparison, the time to reach the D37 would be as few as 305 years on the surface of Mars, which receives solar energetic protons and high-energy galactic cosmic rays (as well as germicidal short-wavelength UV radiation) at a rate estimated to be 830 mGy year−1 (38). In this end-member scenario, IR would induce an average of one DSB per cell every 35 years on the Martian surface, a frequency that is 280-fold lower than the rate of DSB repair measured in this study (Fig. 4B). Our experiments delivered a dose of IR in 90 min that would be equivalent to the cumulative dosage P. arcticus would be exposed to over 225 ky in permafrost (Fig. 1). As such, a more restrained response to DNA damage may be ample for cellular maintenance under IR conditions that more closely resemble those found in nature. It is also important to note that our estimates of DSBs induced by IR were based on experiments with liquid cell suspensions (20) and therefore may not be directly applicable to those under frozen conditions. However, the sizes of genome fragments observed after exposure to 450 Gy of IR (Fig. 3) agreed well with predicted values (Table 1). If our data and related calculations are an approximation of P. arcticus's physiological potential in permafrost, a rate of 7 to 10 DSBs repaired year−1 at −15°C would be more than sufficient to offset DSB damage resulting from IR in terrestrial permafrost or ice on the surface of Mars. Although this study focused on a cold-adapted bacterium from the cryosphere, our results may have broader implications for understanding microbial longevity in the deep biosphere (e.g., see references 39 and 40), where microbes persist on scant energy sources and the turnover of microbial biomass is estimated to be hundreds to several thousand years (41, 42).

In his review of the endogenous hydrolytic and oxidative processes that decompose DNA, Lindahl (43) described how genomic DNA would progressively accumulate damage when “deprived of the repair mechanisms provided in living cells.” DNA is inherently unstable, exhibiting spontaneous base loss, deamination, and strand breaks. Although the rates of these processes are extremely low under physiological conditions, they will eventually degrade the DNA to a point where information storage is no longer possible. Lindahl concluded that under the best conditions, genomic DNA will degrade to short nonfunctional fragments within tens of thousands of years, and the recovery of low-molecular-weight DNA fragments from long-dead animals and plants supports this prediction (e.g., see reference 44 and references within). However, the rates of DNA decomposition described by Lindahl (43) are not relevant in considering the longevity of genomic DNA if a cell expresses DNA repair processes. We suggest that as long as cells are capable of repair, the long-term effects of spontaneous decomposition or natural radioactive decay on their genomic DNA can be delayed and cell survival extended.

Conclusions.

This study demonstrated that P. arcticus has the capacity to overcome damage induced to its genome by IR at a rate >100,000 times faster than DNA DSB lesions would occur in its native permafrost environment. This has expanded our understanding of bacterial physiology at low temperature and provides direct evidence of a mechanism that could increase the longevity of microbes in frozen matrices. Considering the instability of DNA, the capacity to conduct metabolic activity under icy conditions is a long-term survival strategy that is superior to dormancy. The ability to synthesize (14) and repair (Fig. 4B) DNA at temperatures relevant to Siberian permafrost and the northern polar region of Mars (45) suggests that long-term survival of P. arcticus under such conditions may be limited only by the water activity and availability of suitable redox couples and nutrients. In conclusion, our investigation of DNA repair in a permafrost bacterium has revealed an important factor pertinent to theoretical predictions of microbial longevity while frozen (37, 38) and is clearly relevant to discussions concerning the survival of microbial life in icy extraterrestrial environments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Gregg S. Pettis for assistance with PFGE.

This work was supported by grants to B.C.C. from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (grants NNX10AR92G and NNX10AN07A) and the Louisiana Board of Regents.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 Septembre 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Persky NS, Lovett ST. 2008. Mechanisms of recombination: lessons from E. coli. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43:347–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kowalczykowski SC. 1991. Biochemistry of genetic recombination: energetics and mechanism of DNA strand exchange. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 20:539–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kowalczykowski SC, Dixon DA, Eggleston AAK, Lauder SD, Rehrauer WM. 1994. Biochemistry of homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 58:401–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christner BC, Mosley-Thompson E, Thompson LG, Reeve JN. 2003. Bacterial recovery from ancient ice. Environ. Microbiol. 5:433–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christner BC, Royston-Bishop G, Foreman CM, Arnold BR, Tranter M, Welch KA, Lyons WB, Tsapin AI, Studinger M, Priscu JC. 2006. Limnological conditions in subglacial Lake Vostok, Antarctica. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51:2485–2501 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bidle KD, Lee SH, Marchant DR, Falkowski PG. 2007. Fossil genes and microbes in the oldest ice on Earth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:13455–13460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilichinsky DA, Wilson GS, Friedmann EI, Mckay CP, Sletten RS, Rivkina EM, Vishnivetskaya TA, Erokhina LG, Ivanushkina NE, Kochkina GA, Shcherbakova VA, Soina VS, Spirina EV, Vorobyova EA, Fyodorov-Davydov DG, Hallet B, Ozerskaya SM, Sorokovikov VA, Laurinavichyus KS, Shatilovich A, Chanton JP, Ostroumov VE, Tiedje JM. 2007. Microbial populations in Antarctic permafrost: biodiversity, state, age, and implication for astrobiology. Astrobiology 7:275–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson SS, Hebsgaard MB, Christensen TR, Mastepanov M, Nielsen R, Munch K, Brand T, Gilbert MT, Zuber MT, Bunce M, Rønn R, Gilichinsky D, Froese D, Willerslev E. 2007. Ancient bacteria show evidence of DNA repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:14401–14405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Price PB. 2000. A habitat for psychrophiles in deep Antarctic ice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:1247–1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barletta RE, Priscu JC, Mader HM, Jones WL, Roe CH. 2012. Chemical analysis of ice vein microenvironments. II. Analysis of glacial samples from Greenland and Antarctica. J. Glaciol. 58:1109–1118 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dani KGS, Mader HM, Wahman JL, Wolff EW. 2012. Modelling the liquid-water vein system within polar ice sheets as a potential microbial habitat. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 333–334:238–249 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doyle S, Dieser M, Broemsen E, Christner B. 2012. General characteristics of cold-adapted microorganisms, p 103–125 In Whyte L, Miller RV. (ed), Polar microbiology: life in a deep freeze. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price PB, Sowers T. 2004. Temperature dependence of metabolic rates for microbial growth, maintenance, and survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:4631–4636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amato P, Doyle SM, Battista JR, Christner BC. 2010. Implications of subzero metabolic activity on long-term microbial survival in terrestrial and extraterrestrial permafrost. Astrobiology 10:789–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Lorenzo V. 2011. Genes that move the window of viability of life: lessons from bacteria thriving at cold extremes. Bioessays 33:38–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verde C, di Prisco G, Giordano D, Russo R, Anderson D, Cowan D. 2012. Antarctic psychrophiles: models for understanding the molecular basis of survival at low temperature and response to climate change. Biodiversity 13:249–256 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reasoner DJ, Geldreich EE. 1985. A new medium for the enumeration and subculture of bacteria from potable water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 49:1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fricke H, Hart EJ. 1966. Chemical dosimetry, p 167–239 In Attix FH, Roesch WC. (ed), Radiation dosimetry. Academic Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ayala-del-Río H, Chain PS, Grzymski JJ, Ponder MA, Ivanova N, Bergholz P, Di Bartolo G, Hauser L, Land M, Bakermans C, Rodrigues D, Klappenbach J, Zarka D, Larimer F, Richardson P, Murray A, Thomashow M, Tiedje JM. 2010. The genome sequence of Psychrobacter arcticus 273-4, a psychroactive Siberian permafrost bacterium, reveals mechanisms for adaptation to low-temperature growth. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:2304–2312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burrell AD, Dean CJ. 1975. Repair of double-strand breaks in Micrococcus radiodurans. Basic Life Sci. 5B:507–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vishnivetskaya T, Kathariou S, McGrath J, Gilichinsky D, Tiedje JM. 2000. Low temperature recovery strategies for the isolation of bacteria from ancient permafrost sediments. Extremophiles 4:165–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bakermans C, Tsapin AI, Souza-Egipsy V, Gilichinsky DA, Nealson KH. 2003. Reproduction and metabolism at −10°C of bacteria isolated from Siberian permafrost. Environ. Microbiol. 5:321–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergholz PW, Bakermans C, Tiedje JM. 2009. Psychrobacter arcticus 273-4 uses resource efficiency and molecular motion adaptations for subzero temperature growth. J. Bacteriol. 191:2340–2352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponder MA, Thomashow MF, Tiedje JM. 2008. Metabolic activity of Siberian permafrost isolates, Psychrobacter arcticus and Exiguobacterium sibiricum, at low water activities. Extremophiles 12:481–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bakermans C, Ayala-del-Río HL, Ponder MA, Vishnivetskaya T, Gilichinsky D, Thomashow MF, Tiedje JM. 2006. Psychrobacter cryohalolentis sp. nov. and Psychrobacter arcticus sp. nov., isolated from Siberian permafrost. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56:1285–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Auman AJ, Breezee JL, Gosink JJ, Kaempfer P, Staley JT. 2006. Psychromonas ingrahamii sp. nov., a novel gas vacuolate, psychrophilic bacterium isolated from Arctic polar sea ice. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56:1001–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wells LE, Deming JW. 2006. Characterization of a cold-active bacteriophage on two psychrophilic marine hosts. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 45:15–29 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mykytczuk NCS, Foote SJ, Omelon CR, Southam G, Greer CW, Whyte LG. 2013. Bacterial growth at −15°C; molecular insights from the permafrost bacterium Planococcus halocryophilus Or1. ISME J. 7:1211–1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rivkina E, Laurinavichius K, McGrath J, Tiedje J, Shcherbakova V, Gilichinsky 2004. Microbial life in permafrost. Adv. Space Res. 33:1215–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Douglas TA, Fortier D, Shur YL, Kanevskiy MZ, Guo L, Cai Y, Bray MT. 2011. Biogeochemical and geocryological characteristics of wedge and thermokarst-cave ice in the CRREL permafrost tunnel, Alaska. Permafrost Periglac. Processes 22:120–128. 10.1002/ppp.709 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alur MD, Grecz N. 1975. Mechanism of injury of Escherichia coli by freezing and thawing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 62:308–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grecz N, Hammer TL, Robnett CJ, Long MD. 1980. Freeze-thaw injury: evidence for double strand breaks in Escherichia coli DNA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 93:1110–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wigley DB. 2013. Bacterial DNA repair: recent insights into the mechanism of RecBCD, AddAB and AdnAB. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11:9–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alonso JC, Cardenas PP, Sanchez H, Hejna J, Suzuki Y, Takeyasu K. 2013. Early steps of double-strand break repair in Bacillus subtilis. DNA Repair 12:162–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chayot R, Montagne B, Mazel D, Ricchetti M. 2010. An end-joining repair mechanism in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:2141–2146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shechter N, Zaltzman L, Weiner A, Brumfeld V, Shimoni E, Fridmann-Sirkis Y, Minsky A. 2013. Stress-induced condensation of bacterial genomes results in re-pairing of sister chromosomes: implications for double-strand DNA break repair. J. Biol. Chem. 288:25659–25667. 10.1074/jbc.M113.473025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKay CP. 2001. The deep biosphere: lessons for planetary exploration, p 315–327 In Frederickson JK, Fletcher M. (ed), Subsurface microbiology and biogeochemistry. Wiley-Liss, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dartnell LR, Desorgher Ward LM, Coates AJ. 2007. Modelling the surface and subsurface Martian radiation environment: implications for astrobiology. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34:L02207 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morono Y, Terada T, Nishizawa M, Ito M, Hillion F, Takahata N, Sanoe Y, Inagaki F. 2011. Carbon and nitrogen assimilation in deep subseafloor microbial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:18295–18300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roussel EG, Cambon Bonavita MA, Querellou J, Cragg BA, Webster G, Prieur D, Parkes RJ. 2008. Extending the sub-sea-floor biosphere. Science 320:1046. 10.1126/science.1154545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biddle JF, Lipp JS, Lever MA, Lloyd KG, Sorensen KB, Anderson R, Fredricks HF, Elvert M, Kelly TJ, Schrag DP, Sogin ML, Brenchley JE, Teske A, House CH, Hinrichs KU. 2006. Heterotrophic Archaea dominate sedimentary subsurface ecosystems off Peru. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:3846–3851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jørgensen BB. 2011. Deep subseafloor microbial cells on physiological standby. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:18193–18194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindahl T. 1993. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature 362:709–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Willerslev E, Cooper A. 2005. Ancient DNA. Proc. Biol. Sci. 272:3–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jakosky BM, Nealson KH, Bakermans C, Ley RE, Mellon MT. 2003. Subfreezing activity of microorganisms and the potential habitability of Mars' polar regions. Astrobiology 3:343–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]