Abstract

Microbial desulfurization, or biodesulfurization (BDS), of fuels is a promising technology because it can desulfurize compounds that are recalcitrant to the current standard technology in the oil industry. One of the obstacles to the commercialization of BDS is the reduction in biocatalyst activity concomitant with the accumulation of the end product, 2-hydroxybiphenyl (HBP), during the process. BDS experiments were performed by incubating Rhodococcus erythropolis IGTS8 resting-cell suspensions with hexadecane at 0.50 (vol/vol) containing 10 mM dibenzothiophene. The resin Dowex Optipore SD-2 was added to the BDS experiments at resin concentrations of 0, 10, or 50 g resin/liter total volume. The HBP concentration within the cytoplasm was estimated to decrease from 1,100 to 260 μM with increasing resin concentration. Despite this finding, productivity did not increase with the resin concentration. This led us to focus on the susceptibility of the desulfurization enzymes toward HBP. Dose-response experiments were performed to identify major inhibitory interactions in the most common BDS pathway, the 4S pathway. HBP was responsible for three of the four major inhibitory interactions identified. The concentrations of HBP that led to a 50% reduction in the enzymes' activities (IC50s) for DszA, DszB, and DszC were measured to be 60 ± 5 μM, 110 ± 10 μM, and 50 ± 5 μM, respectively. The fact that the IC50s for HBP are all significantly lower than the cytoplasmic HBP concentration suggests that the inhibition of the desulfurization enzymes by HBP is responsible for the observed reduction in biocatalyst activity concomitant with HBP generation.

INTRODUCTION

Biodesulfurization (BDS) is a process in which microorganisms, typically, bacteria, are used to reduce the level of sulfur in fuels derived from crude oil, including diesel and gasoline. Over the last 20 years, interest in BDS as an alternative to hydrodesulfurization (HDS), which is the current desulfurization standard in the oil industry, has increased. HDS uses a metal catalyst along with hydrogen gas (H2) at high temperature and pressure to remove sulfur from organic sulfur compounds and generate H2S gas (1). Major drawbacks of HDS include steric hindrance of the metal catalysts by certain recalcitrant compounds and large energy consumption due to process operation at high temperature and pressure (1). Recalcitrant compounds include the parent molecule dibenzothiophene (DBT) and some of its alkylated derivatives, such as 4-methyldibenzothiophene (4-DBT) and 4,6-dimethyldibenzothiophene (4,6-DBT). BDS can potentially be used to remove the sulfur that cannot be removed by HDS, though it is likely not a replacement for the current HDS infrastructure. The use of more than one desulfurization technology may be necessary to meet the increasingly stringent sulfur regulations (1).

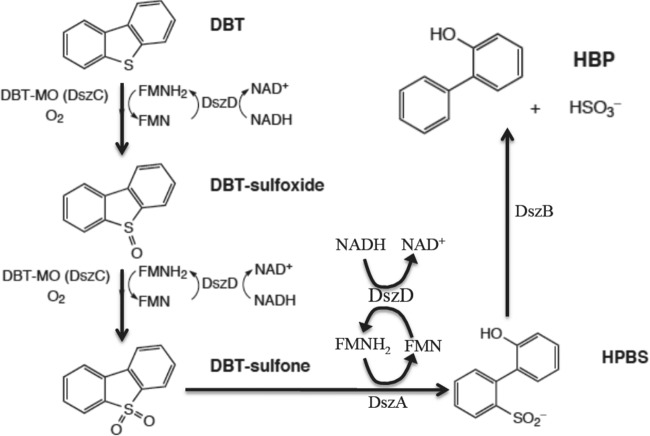

There is a wide range of microorganisms known to have BDS capability (2). Such microorganisms typically desulfurize DBT by one of two pathways: the Kodama pathway or the 4S pathway (1). The Kodama pathway is a destructive BDS pathway in which carbon-carbon bonds in the DBT molecule are broken and sulfur is not selectively removed from the organic molecule. Due to its destructive nature, the Kodama pathway reduces the caloric value of the fuel that is being desulfurized. As a result, the majority of the focus in the past 20 years has been on the 4S pathway, which is an oxidative desulfurization pathway that cleaves the carbon-sulfur bond in DBT and leaves the carbon structure intact. The 4S pathway is a four-step enzymatic pathway that converts DBT to 2-hydroxybiphenyl (HBP) and sulfate (Fig. 1). The first two steps are the conversion of DBT to DBT sulfoxide (DBTO) and then to DBT sulfone (DBTO2). These steps are catalyzed by the enzymes DszC monooxygenase and DszD oxidoreductase in synchrony. The third step is the conversion of DBTO2 to 2-(2′-hydroxyphenyl) benzene sulfinate (HBPS), which is catalyzed by DszA monooxygenase and DszD oxidoreductase in synchrony. The final step is the conversion of HBPS to HBP and sulfite by DszB desulfinase (3).

Fig 1.

The four-step biodesulfurization 4S pathway. The first two steps, catalyzed by both DszC and DszD, are the conversion of DBT to DBT-sulfoxide (DBTO) and then to DBT-sulfone (DBTO2). The third step, catalyzed by both DszA and DszD, is the conversion of DBTO2 to HBPS. The final step is the conversion of HBPS to HBP by DszB. DBT-MO, DBT monooxygenase.

The isolation and purification of the desulfurization enzymes from Rhodococcus erythropolis IGTS8 have been reported (4, 5). Preliminary characterization of these enzymes showed that DszB catalyzes the slowest reaction with a turnover number (kcat) of about 2 min−1 (4). Furthermore, it was reported that DszA has a kcat of about 1/s (4). Following the finding that DszB catalyzes the slowest step, the kinetics of DszB were investigated in detail (6). DszB kinetics were modeled appropriately by the Michaelis-Menten model with a Michaelis constant (Km) of 0.90 ± 0.15 μM and a kcat of 1.3 ± 0.07 min−1 (6). The kinetics of DszA, DszC, and DszD from R. erythropolis IGTS8 have yet to be investigated in detail.

Two major obstacles facing BDS commercialization are that (i) biocatalyst activities are significantly lower than what is needed for BDS rates to match HDS rates (2) and (ii) biocatalysts cannot maintain activity for a long period of time. Considerable effort has gone into trying to understand and overcome the limitations to the desulfurization activity of the biocatalysts. Several studies have shown that genetic engineering can lead to higher desulfurization activities (2). For example, the desulfurization activity of R. erythropolis KA2-5-1 was increased from 50 to 250 μmol DBT/g dry cell weight (DCW)/h by providing multiple copies of the desulfurization genes and placing them under the control of alternative promoters (2).

A reduction in biocatalyst activity over time has been widely reported in BDS processes (2, 7, 8). The reduction in activity is typically correlated to the accumulation of HBP in the medium during the BDS process. The desulfurization activity of a cell suspension of R. erythropolis IGTS8 with a cell density of 66 g DCW/liter mixed with hexadecane (at a 1:1 [vol/vol] ratio) containing 19,000 μM DBT was found to follow first-order decay with a decay constant of 0.072 h−1 (7). It was suggested that the loss of biocatalyst activity might be due to exposure to increasing HBP concentrations, although no experiments were done to validate this hypothesis (7). The cells were active for 24 h, and only 7,000 out of 19,000 μM DBT in oil was consumed. The final concentration of HBP accumulated in the oil phase after 24 h was only 3,300 μM. Although aqueous-phase accumulation of DBT or HBP was not measured, the contribution from the aqueous phase concentration to the overall concentration of either compound could not have been more than 5%. This was estimated on the basis of the partition coefficients of DBT and HBP between hexadecane (oil) and water (PO/W), which are 21,000 and about 30 to 50, respectively (9). As a result, approximately 3,600 to 3,700 μM DBT or HBP is unaccounted for at the end of the BDS process. Possible reasons for the discrepancy between DBT disappearance and HBP accumulation are accumulation of pathway intermediates or retention of DBT and/or HBP within the biocatalyst. R. erythropolis, being a Gram-positive bacterium, has a cytoplasmic membrane surrounded by a thick cell wall made mostly of peptidoglycan. The cell wall is composed of a thick peptidoglycan structure to which fatty acid molecules are attached. In the case of R. erythropolis (a member of the Actinomycetes family), the cell wall is composed of mycolic acids that are perpendicular to the cell surface (10). These mycolic acids range from 30 to 54 carbon atoms in length, and they make the cell wall of R. erythropolis highly hydrophobic. It is possible that a significant concentration of DBT initially in the oil phase would have been retained within the cell wall of R. erythropolis IGTS8 as it entered the cell. It is also possible that a significant fraction of HBP produced by the biocatalyst would have been trapped within the biocatalyst cytoplasmic membrane or cell wall as it exited the cell. The amount of DBT or HBP retained by the biocatalyst depends on the partition coefficients between the biocatalyst and the oil or aqueous phases, PC/O or PC/W, respectively (where C, O, and W represent cells, oil, and water, respectively).

A number of studies have investigated the effect of HBP on biocatalyst activity. HBP has been shown to inhibit the growth of R. erythropolis IGTS8 at concentrations greater than 200 μM (11). Preliminary characterization of the DszB enzyme from R. erythropolis KA2-5-1 showed that its activity is reduced by 50% at HBP concentrations of about 2,000 μM (12). In other studies, the effect of exogenously added HBP on the BDS process has been described. R. erythropolis IGTS8 aqueous resting-cell suspensions of 2 g DCW/liter were prepared and supplied with only one of the 4S pathway compounds (either DBT, DBTO, DBTO2, or HBPS) (13). HBP was also added at concentrations of either 0 or 50 μM in each experiment. The disappearance rate of each compound was monitored over a short period of 15 min. It was found that the disappearance rates of DBTO and HBPS were significantly reduced by the presence of 50 μM HBP. These results suggested that HBP might be inhibitory to the enzymes responsible for DBTO and HBPS consumption, which are DszC and DszB, respectively (Fig. 1). In a different study, the DBT desulfurization rate of resting cells of Microbacterium sp. strain ZD-M2 was found to decrease significantly when HBP was added exogenously at concentrations ranging from 0 to 2,000 μM (14). Results from experiments where HBP is added exogenously cannot be used to quantitatively predict the effect of HBP on a typical BDS process where DBT is added exogenously and HBP is generated endogenously within the cytoplasm of the cells. When HBP is added exogenously, a significant fraction may be retained by the cell wall and may never reach the cytoplasm, where inhibition of the desulfurization enzymes could occur. On the other hand, HBP generated endogenously within the cytoplasm is immediately at the location where it can be inhibitory to the desulfurization enzymes. Therefore, the specific HBP loading of the biocatalyst (mg HBP/g DCW) that leads to a certain level of reduction in BDS activity may be significantly larger when HBP is added exogenously.

In summary, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that HBP (either generated endogenously or supplied exogenously) reduces the overall biocatalyst activity. In this work, a series of commercially available adsorbents was screened for the affinity and selectivity of the adsorbents to adsorption of HBP. The best adsorbent was used to determine whether or not HBP-selective adsorbents could help mitigate the loss of desulfurization activity correlated with HBP accumulation during the BDS process. The kinetics and inhibition of the four enzymes in the 4S pathway by the intermediate compounds were next investigated in detail, in an attempt to understand the mechanism for the reduction in biocatalyst activity that is correlated with HBP accumulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, vectors, media, and chemicals.

The DBT-desulfurizing strain used in this study was Rhodococcus erythropolis IGTS8 ATCC 53968, purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. The defined minimal medium for cultivation contained the following (per liter of deionized water): glucose, 30.0 g; NH4Cl, 3.0 g; K2HPO4 · 3H2O, 6.75 g; NaH2PO4 · H2O, 2.25 g; MgCl2, 0.245 g; FeCl3, 4 mg; CaCl2, 4 mg; Na2SO4, 0.14 g; ZnCl2, 32 mg; MnCl2 · 4H2O, 1 mg; CuCl2 · 2H2O, 5 mg; Co(NO3)2 · 6H2O, 0.7 mg; Na2B4O7 · 10H2O, 0.7 mg; (NH4)6Mo7O24 · 4H2O, 1 mg; EDTA, 12 mg. Cryogenic stocks were prepared by addition of 15% (vol/vol) glycerol (final concentration) to mid-log-growth-phase cultures in minimal medium, which were then kept at −80°C for long-term storage. Medium components were obtained from VWR International. Christine Nguyen, from Stephen Buchwald's research group at MIT, kindly provided HBPS. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The strains used for expression of the desulfurization genes were Escherichia coli MAX Efficiency DH10B and E. coli BL21 Star(DE3) One Shot from Invitrogen. The vector used for all molecular manipulations was pETDuet-1 from Novagen. The medium used to culture these strains was Luria-Bertani (LB) broth from Difco supplemented with ampicillin (working concentration, 100 μg/ml) for selection of clones containing the pETDuet-1 vector.

Testing HBP adsorbents.

Activated charcoal, molecular sieves (pore sizes, 4, 5, and 13 Å), Diaion HP-20, Dowex Optipore L-493, Dowex Optipore SD-2, Biobeads, Amberlite XAD4, Amberlite IRC86, and Amberlite IRA958 were all obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Resins were tested for their ability to adsorb HBP from a hexadecane-water solution. The adsorption experiments were carried out in 20-ml scintillation vials by mixing 5 ml of water with 5 ml of a hexadecane solution containing 10,000 μM DBT and 10,000 μM HBP with either 0.1 or 1.0 g of resin. Mixtures were equilibrated for 24 h at 30°C, with agitation at 250 rpm. After measuring solute concentrations before and after sample equilibration with a particular resin concentration (Xr), specific loadings (Lr) were determined by the following relationships:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where CHBP represents the total concentration of HBP (in oil and water), Vtotal is the total volume of solution (oil plus water), mr is the mass of resin used, Xr is the concentration of resin employed, MMHBP is the molecular mass of HBP (170 g/mol), and t0 and teq represent the times at initial and equilibrium conditions, respectively.

Resting-cell preparation.

R. erythropolis IGTS8 cultures were grown in 400 ml of minimal medium in a 2-liter shake flask for a period of 40 to 48 h, during which the cell density increased from approximately 0.03 g DCW/liter to 3 g DCW/liter. Cultures were centrifuged at 5,000 rpm and 4°C for 15 min, and spent medium was discarded. Biocatalyst pellets were resuspended to the experimental cell density in 5 g/liter glucose and 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0.

Four-component biodesulfurization experiments.

BDS experiments in the presence of Dowex Optipore SD-2 resin were carried out in 250-ml shake flasks containing 20 ml of a 15.5-g DCW/liter resting-cell suspension mixed with 20 ml of hexadecane containing 10,000 μM DBT. The resin was added to the mixture at Xrs of 0, 10, or 50 g/liter in the shake flask, and the flasks were incubated at 30°C for 26 h. After the 26-h incubation period, the mixtures were centrifuged for 15 min at 5,000 rpm, and the four components (oil, water, cells, and resin) were separated. The DBT and HBP concentrations in the oil and aqueous components were measured directly after centrifugation. The DBT and HBP concentrations in the cells and resin were measured by extraction into ethanol. Ethanol was selected as the best extractant among a variety of solvents tested, including acetone, methanol, hexane, hexadecane, squalane, and toluene. Cell wall solubilization by treatment with an enzymatic mixture of lysozyme (100 mg/ml) and mutanolysin (5,000 U/ml) did not increase the concentration of DBT or HBP extracted from the cells. Sonication of the cells also did not increase extraction concentrations. Loadings of HBP on the biocatalyst (Lc) and resin (Lr) were calculated from the expressions

| (3) |

| (4) |

where Cextract, i is the concentration of HBP in the ith extract, Vextract is the volume of the extract (constant for each fraction), mcells is the mass of cells extracted, and mr is the mass of resin extracted.

DNA manipulations and preparation of E. coli recombinant strains.

Molecular biology manipulations were performed according to standard protocols. Genomic DNA was extracted from R. erythropolis IGTS8 using Promega's Wizard genomic DNA purification kit. Each of the desulfurization genes was PCR amplified from the extracted genomic DNA with appropriate primers (see the supplemental material). Restriction sites for EcoRI and HindIII were included in the primers. PCR amplicons were then cut with the appropriate restriction enzymes and ligated with the pETDuet-1 vector that had previously been cut with the corresponding restriction enzymes. The sequences of the resulting vectors containing the four genes (dszA, dszB, dszC, and dszD) were verified. Each of the four vectors was then used to transform E. coli DH10B by electroporation using 1-mm-path-length cuvettes. E. coli BL21 Star(DE3) was used as the expression host for each of the four desulfurization proteins and transformed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). Selection with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) was used to identify successful transformants.

Protein expression and purification protocol.

The following protocol was followed to express and purify each of the four desulfurization enzymes:

A transformed E. coli BL21 Star(DE3) colony from an LB broth-ampicillin plate was picked and grown in 10 ml LB broth with ampicillin at 30°C overnight.

On the next day, 1 liter of LB medium with ampicillin was inoculated with 10 ml of an overnight culture, and cells were grown at 30°C with shaking at 250 rpm.

The 1-liter culture was induced with 0.3 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) when the optical density at 600 nm of the culture was 0.5 to 0.6. Growth was continued for 18 h at 20°C.

Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C.

The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was frozen at −20°C overnight.

From this point on, all cells and protein samples were maintained at 4°C or on ice to avoid protein degradation. The cell pellet was resuspended using a volume of the 1× His buffer (with 10% glycerol) equal to at least 2.5 times the mass of the cell pellet. Lysozyme (1 mg/ml) and DNase I (500 μg/ml) were added, and the cell suspension was incubated for 30 min on ice.

The cell suspension was sonicated for 15 to 30 min at 90 to 100% amplitude with a 1-s on/1-s off cycle.

Cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 20,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C.

The supernatant (20 to 40 ml) was mixed with 5 ml Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (Qiagen) in order to bind the histidine-tagged desulfurization protein to the resin. The time for this binding step was 1 h at 4°C.

After the 1-h binding step, the protein-resin mixture was poured onto a Pierce centrifuge column (total volume, 10 ml), and the resin was allowed to settle. The flowthrough was processed by gravity flow and collected.

The resin was washed with 10 ml of 1× His buffer containing 7.5 mM imidazole, and the flowthrough was collected. Then, the resin was treated with five different solutions of 1× His buffer containing increasing imidazole concentrations of 40, 60, 100, 250, and 500 mM imidazole. Each solution was 5 ml in volume. The eluent of each fraction was collected.

A diagnostic SDS-polyacrylamide gel was run to determine the fractions with the highest purity. These fractions were combined in one piece of snakeskin dialysis tubing, and the protein sample was dialyzed overnight in 1 liter of 50 mM Tris-HCl–50 mM NaCl–10% glycerol buffer in a cold room with mild stirring.

Finally, the dialyzed protein was flash-frozen using liquid nitrogen in small aliquots for long-term storage at −80°C.

Enzyme assays.

All enzyme assays were performed in 20 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 and 30°C. The assay volume was 1,000 μl for all assays. DszD assays were performed in semimicrocuvettes and maintained at room temperature. DszA, DszB, and DszC assays were performed in 1.7-ml Eppendorf tubes in a rotary shaker incubator at 30°C and 250 rpm and were quenched either by addition of 1% of a 12 M HCl solution or by use of an Amicon Ultra 0.5-ml 10-kDa spin filter device to remove the enzyme. For DszD enzyme assays, either the concentration of NADH was varied from 0 to 400 μM (at a fixed flavin mononucleotide [FMN] concentration of 100 μM) or the concentration of FMN was varied from 0 to 100 μM (at fixed a NADH concentration of 150 μM), the concentration of DszD enzyme was 1.2 μg/ml, and the assays were run for 10 min. For DszC enzyme assays, the concentration of NADH was 500 μM, the FMN concentration was 10 μM, the DBT concentration was varied from 0 to 5 μM, the DszD concentration was 0.47 μg/ml, the DszC concentration was 3.1 μg/ml, and the assays were run for 5 min. Assay conditions were identical for determining the mechanism of DszC inhibition by HBPS and HBP, except for the addition of those compounds at concentrations of 0 to 200 and 0 to 1,000 μM, respectively. For DszA enzyme assays, the NADH concentration was 500 μM, the FMN concentration was 10 μM, the DBTO2 concentration was varied from 0 to 80 μM, the DszD concentration was 1.4 μg/ml, the DszA concentration was 6.7 μg/ml, and the assays were run for 3 min. For DszB enzyme assays, the HBPS concentration was varied from 0 to 200 μM, the DszB concentration was 3.5 μg/ml, and the assays were run for 5 min. For all four enzymes, dose-response-type assays were performed to measure the inhibitory concentration leading to a 50% reduction in enzyme activity (IC50). For DszD dose-response assays, the concentration of NADH was 500 μM and that of FMN was 200 μM, the concentration of the various pathway intermediates was varied (DBT, 0 to 5 μM; DBTO2, 0 to 80 μM; HBPS, 0 to 2,000 μM; HBP, 0 to 2,000 μM), the concentration of DszD was 4.7 μg/ml, and the assays were run for up to 5 min. For DszC dose-response assays, the NADH concentration was 500 μM, the FMN concentration was 10 μM, the DBT concentration was 5 μM, the DszD concentration was 0.47 μg/ml, the DszC concentration was 0.3 mg/ml, the concentration of the pathway intermediates was varied (DBTO2, 0 to 80 μM; HBPS, 0 to 1,000 μM; HBP, 0 to 2,000 μM), and the assays were run for 10 min. For DszA dose-response assays, the NADH concentration was 500 μM, the FMN concentration was 10 μM, the DBTO2 concentration was 80 μM, the DszD concentration was 1.4 μg/ml, the DszA concentration was 67 μg/ml, the concentration of the pathway intermediates was varied (DBT, 0 to 5 μM; HBPS, 0 to 500 μM; HBP, 0 to 1,000 μM), and the run time was 3 min. For DszB dose-response assays, the HBPS concentration was 200 μM, the DszB concentration was 58.5 μg/ml, the concentration of the pathway intermediates was varied (DBT, 0 to 5 μM; DBTO2, 0 to 80 μM; HBP, 0 to 1,000 μM), and the assays were run for 5 min.

Analytical methods.

For DszD assays, the absorbance at 340 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer to calculate the NADH concentration, and this was used to calculate the activity. The concentrations of DBT, DBTO2, HBPS, and HBP were measured using reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a Zorbax SB-C18 column at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. For DszC and DszB assays, the mobile phase was 50% acetonitrile–50% water and the temperature of the column was maintained at 65°C. For DszA assays, the mobile phase was 30% acetonitrile–70% 10 mM tetrabutylammonium bisulfate, the mobile phase was 15 mM acetic acid (pH 5.0), and the temperature of the column was maintained at 45°C.

RESULTS

Screening HBP-selective adsorbent resins.

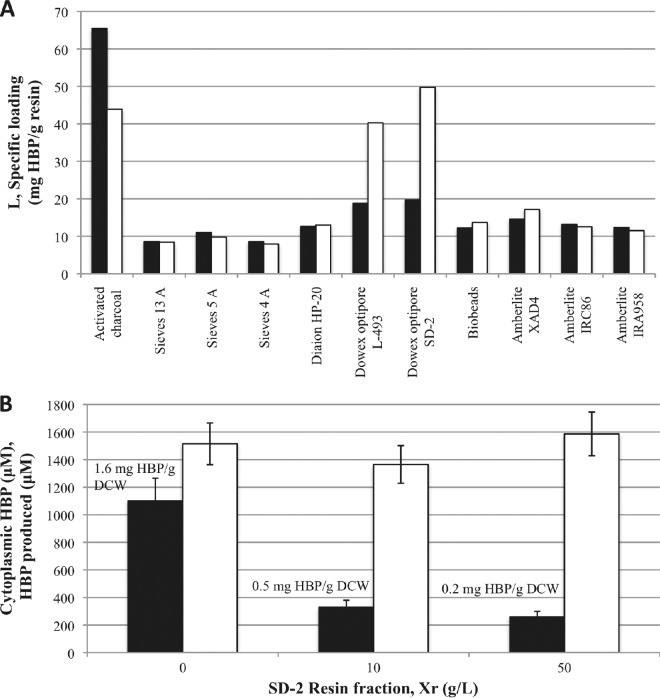

A variety of commercially available resins were screened for their ability to take up HBP and DBT from a 0.50 (vol/vol) hexadecane-water solution with an initial concentration of 10,000 μM DBT and 10,000 μM HBP in hexadecane. The resins screened in this study were chosen because they span a wide range of resin hydrophobicity and ionic functionalities, and most have been previously investigated in the Prather lab (15). We found that poly(styrene-co-divinylbenzene)-derived resins generally had the greatest affinity for HBP (Fig. 2A; Xr = 10 g resin/liter total volume for each resin). For instance, Dowex Optipore L-493 and SD-2 were able to achieve specific loadings of HBP of 40 and 50 mg/g resin, respectively. In addition to having the highest affinity for HBP of all the resins tested, Dowex Optipore L-493 and SD-2 also possessed the highest selectivity for HBP relative to DBT, with HBP loadings that were 2.1 and 2.5 times greater than their respective DBT loadings. These resins were also found to have the highest affinity for butanol, with specific loadings of butanol of 175 and 150 mg/g resin, respectively (15). The high affinity of these resins for butanol has been attributed to strong hydrophobic interactions between the resins' π-π bonds of the aromatic side groups and the alkyl chain of butanol and to the resins' high specific surface area (15). The affinity of these resins for HBP is likely due to strong hydrophobic interactions between the resins' aromatic side groups and the biphenyl part of HBP, though the specific loadings are reduced relative to that of n-butanol.

Fig 2.

(A) Specific loading of HBP (white) and DBT (black) by the various resins tested at a resin concentration of 10 g/liter from a 0.50 (vol/vol) hexadecane-water solution initially containing 10 mM DBT and 10 mM HBP. (B) Total amount of HBP produced (white) and cytoplasmic HBP concentration (black) in the four-component BDS experiment at 15.5 g DCW/liter and with an oil fraction of 0.50 (vol/vol) and 10 mM DBT. Specific HBP loadings are shown above the black columns. Data shown are the averages and standard deviations of 3 replicates.

Four-component BDS experiments.

We previously reported that the DBT desulfurization activity of R. erythropolis IGTS8 is significantly reduced as HBP accumulates in the medium during the BDS process (A. Abin-Fuentes, J. C. Leung, M. E. S. Mohamed, D. I. C. Wang, and K. L. J. Prather, submitted for publication). In particular, we found that the activity of a resting-cell suspension of 15.5 g DCW/liter was decreased by 90% when the HBP concentration in the aqueous medium reached 40 μM (Abin-Fuentes et al., submitted). In previous work, the use of Dowex Optipore SD-2 in butanol fermentations led to a decrease in the aqueous-phase concentration and an increase in productivity (15). In the current work, this resin, which had the best affinity and selectivity for HBP of all resins studied, was used to try to mitigate the reduction in biocatalyst activity correlated with HBP accumulation during the BDS process, thereby increasing the conversion of DBT. R. erythropolis IGTS8 resting-cell suspensions of 15.5 g DCW/liter were mixed with hexadecane (0.50, vol/vol) containing 10,000 μM DBT, and Dowex Optipore SD-2 was added at an Xr of 0, 10, or 50 g/liter. The four-component (oil, water, cells, and resin) mixtures were incubated at 30°C in a rotary shaker at 250 rpm for 26 h. The concentration of DBT and HBP in each component was measured at the end of the incubation period. The partition coefficient of HBP between one component (component 1) and another component (component 2) in the four-component BDS experiments (Pcomp1/comp2) is expressed as

| (5) |

where CHBP, comp1 is the HBP concentration measured in component 1 and CHBP, comp2 is the HBP concentration measured in component 2. For example, PR/C is the partition coefficient of HBP between the resin and the biocatalyst (cells). Similarly, PO/W is the partition coefficient of HBP between hexadecane (oil) and water. The partition coefficients calculated at the different resin concentrations are shown in Table 1. The resin Dowex Optipore SD-2 had the highest affinity for HBP relative to the other components of the system. This resin had log PR/C and log PR/O values of about 2, which means that the resin's affinity for HBP was about 100 times greater than the affinity of either the hexadecane oil phase or the biocatalyst. Furthermore, this resin had a log PR/W of about 4, which means that its affinity for HBP was about 10,000 times greater than that of the aqueous buffer. The partition coefficients of HBP between oil and the aqueous buffer (PO/W) and between the biocatalyst and the aqueous buffer (PC/W) were very similar (Table 1). The log PO/W and log PC/W in the absence of resin were 1.7 and 1.8, respectively. Also, the partition coefficient of HBP between the biocatalyst and oil (PC/O) was calculated to be 1 in the absence of resin. The finding that PO/W was approximately equal to PC/W and that PC/O was approximately equal to 1 indicates that the oil and biocatalyst components have very similar affinities for HBP. Both the oil and the biocatalyst have an affinity for HBP that is 50 to 60 times greater than that of the aqueous buffer in the absence of resin (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of partition coefficients between the four different components in the four-component BDS experiments in the presence of Dowex Optipore SD-2 resina

| Resin concn (g/liter) | PC/O | PC/W | PO/W | PR/C | PR/O | PR/W | Log PC/O | Log PC/W | Log PO/W | Log PR/C | Log PR/O | Log PR/W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 60 | 52 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 1.7 | ||||||

| 10 | 1 | 47 | 42 | 88 | 99 | 4,116 | 0 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 2 | 3.6 |

| 50 | 3 | 160 | 54 | 99 | 296 | 15,906 | 0.5 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 2 | 2.5 | 4.2 |

C, cells; O, oil; W, water; R, resin.

The partition coefficient PC/W is defined as

| (6) |

where CHBP, water is the HBP concentration in the water phase and CHBP, intracellular is the HBP concentration within the biocatalyst. The cell can be viewed as being composed of two components: the inner cytoplasmic space and the outer envelope/shell that encompasses the cytoplasm, which is the cell wall. The partition coefficient of HBP between the cytoplasm and water (Pcytoplasm/W) was estimated from solving for its value in the expression

| (7) |

where Pcell wall/W is the partition coefficient of HBP between the cell wall and the water. The value of Pcell wall/W was estimated to be 550 (see the supplemental material). fcell wall and fcytoplasm are the fractions of the total volume of a single cell that are occupied by the cell wall and cytoplasm, respectively. The values of fcytoplasm and fcell wall were calculated from the expressions

| (8) |

| (9) |

where W is the thickness of the cell wall, which has been estimated to be approximately 10 nm for Rhodococcous species (16). Rcell is the radius of the cell, which was estimated to be 0.5 μm (17). The cytoplasmic HBP concentration (CHBP, cytoplasm) was calculated from the following expression:

| (10) |

The value of CHBP, cytoplasm was calculated to be 1,100, 330, and 260 μM at resin concentrations (Xr) of 0, 10, and 50 g/liter, respectively (Fig. 2B). The corresponding HBP loadings on the biocatalyst (Lc) were calculated to be 1.6, 0.5, and 0.2 mg HBP/g DCW using equation 3 (Fig. 2B). These values show that the resin was effective in reducing HBP retention within the cytoplasm of the biocatalyst, which is where the desulfurization enzymes are present (4). Despite the significant decrease in HBP retained within the cytoplasm, the total amount of HBP produced in the system did not increase with increasing resin concentration (Fig. 2B). Therefore, it was postulated that the biocatalyst and, in particular, the desulfurization enzymes might be susceptible to cytoplasmic HBP concentrations of less than 260 μM.

Enzyme kinetics.

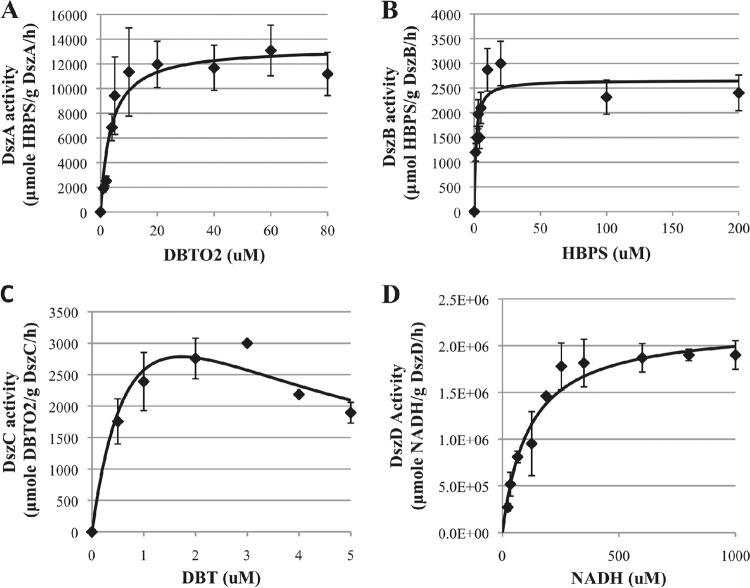

To study the kinetics of each enzyme, recombinant protein was expressed in and purified from E. coli (see the supplemental material). For DszA, DszB, and DszD, the kinetic data obtained were appropriately modeled by the Michaelis-Menten model (Fig. 3A, B, and D). The equation for this model is

| (11) |

where ν is the enzyme activity, kcat is the turnover number, [E0] is the enzyme concentration in each assay, [S] is the substrate concentration, Km is the Michaelis constant, and Vmax is the maximum enzyme activity. The kinetics of DszC could not be modeled accurately with a simple Michaelis-Menten model because it was found that DszC was inhibited by its substrate, DBT (Fig. 3C). As a result, a substrate inhibition model was used to fit the data obtained with DszC (18):

| (12) |

where KSI is the substrate (DBT) inhibition constant.

Fig 3.

Enzyme kinetics for DszA (A), DszB (B), DszC (C), and DszD (D). Diamonds, the data; solid lines, Michaelis-Menten model fits for DszA, DszB, and DszD and substrate inhibition model for DszC. Data shown are the averages and standard deviations of 3 replicates.

The fitting of the models to the data was done using the enzkin package in the MATLAB program. The kinetic data obtained for all four desulfurization enzymes are shown in Fig. 3. The kinetic parameters of each enzyme are summarized in Table 2 and compared to parameters from other studies, where available. To our knowledge, the only prior detailed characterization of a desulfurization enzyme from R. erythropolis IGTS8 found kcat to be equal to 1.3 ± 0.07 min−1 and Km to be equal to 0.90 ± 0.15 μM for DszB (6). In the current work, kinetic characterization of DszB yielded a kcat value of 1.7 ± 0.2 min−1 and a Km value of 1.3 ± 0.3 μM, which are in good agreement with values from the previous study (6). Rough preliminary characterization of DszA and DszD from R. erythropolis IGTS8 yielded kcat values of about 60 min−1 and approximately 300 min−1, respectively (4). The corresponding values of kcat for DszA and DszD measured in this work were 11 ± 2 min−1 and 760 ± 10 min−1, which are of the same order of magnitude as those rough estimates from preliminary characterization studies (4). DszC was inhibited by its substrate (DBT), and the kinetic parameters obtained were as follows: kcat was equal to 1.6 ± 0.3 min−1, Km was equal to 1.4 ± 0.3 μM, and KSI was equal to 1.8 ± 0.2 μM. The activity of DszC from R. erythropolis D-1 was reported to be 30.3 nmol DBTO2/mg DszC/min (19), which is in close agreement with the maximum activity measured in this work of 31.3 nmol DBTO2/mg DszC/min (Fig. 3C).

Table 2.

Main properties of the Dsz enzymes purified in this work, including molecular weights, stock concentrations, and measured kinetic constants

| Enzyme | Mol wt (103) | Stock concn (mg/ml) | This work |

Other authors |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat (min−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (μM−1 min−1) | kcat (min−1) | Km (μM) | |||

| DszA | 49.6 | 1.3 | 11 ± 2 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 3.1 | ∼60a | ∼1a |

| DszB | 39.0 | 1.2 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 ± 0.07b | 0.90 ± 0.15b |

| DszC | 45.0 | 6.1 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3e | 1.1 | NAf | <5a |

| DszD | 25.0 | 4.7 | 760 ± 10 | 114 ± 5 (NADH), 7.3 ± 0.5 (FMN) | 6.7 (NADH), 100 (FMN) | ∼300c | 208 (NADH), 10.8 (FMN)d |

The catalytic efficiency of an enzyme is best defined by the ratio of the kinetic constants, kcat/Km (20). The catalytic efficiency of each desulfurization enzyme was calculated (Table 2). The catalytic efficiencies of DszA, DszB, and DszC were calculated to be 3.1, 1.3, and 1.1 μM−1 min−1, respectively. The catalytic efficiency of DszD on NADH and FMN was calculated to be 6.7 and 100 μM−1 min−1, respectively. Therefore, the enzymes can be listed in order of decreasing efficiency as DszD > DszA > DszB ≈ DszC.

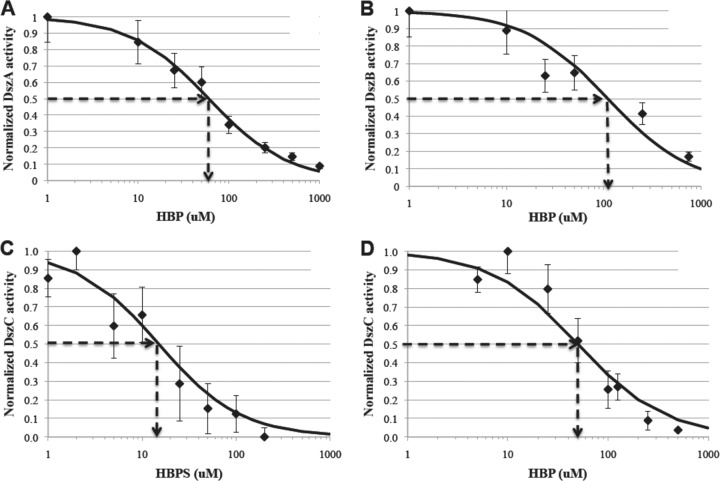

Identification of four major inhibitory interactions in the 4S pathway.

All of the possible interactions among the 4 different desulfurization enzymes and the four compounds in the pathway (DBT, DBTO2, HBPS, and HBP) were studied to determine the major inhibitory interactions. DBTO was not included because it is not typically observed during the BDS process because its rate of consumption is much faster than its rate of generation (4). The strength of inhibition was studied by means of a dose-response plot. The dose-response equation describing the effect of the inhibitor concentration on enzyme activity is expressed as (20)

| (13) |

where νi is the enzyme's activity at an inhibitor concentration of [I], ν0 is the enzyme's activity in the absence of inhibitor, and IC50 is the concentration of inhibitor required to reduce the enzyme's activity by 50%. The IC50 parameter is phenomenological and has no mechanistic implications. The value of IC50 was obtained by fitting the data for νi/ν0 versus [I] to the dose-response equation using the nonlinear fitting package nlinfit in the MATLAB program. The four major inhibitory interactions identified were (in order of decreasing strength) DszC inhibition by HBPS (IC50 = 15 ± 2 μM), DszC inhibition by HBP (IC50 = 50 ± 5 μM), DszA inhibition by HBP (IC50 = 60 ± 5 μM), and DszB inhibition by HBP (IC50 = 110 ± 10 μM) (Fig. 4 and Table 3). Note that the IC50s of all four inhibitory interactions are significantly less than the estimated cytoplasmic HBP concentration. Even in the best-case scenario, when 50 g/liter of a highly HBP-selective resin was added to the BDS mixture, the estimated cytoplasmic HBP concentration was still 260 μM. This finding suggests that these four inhibitory interactions are likely responsible for the reduction in biocatalyst activity that is observed during a typical BDS process when HBP is generated endogenously from DBT within the biocatalyst.

Fig 4.

Normalized desulfurization enzyme activity at different inhibitor concentrations for the four major inhibitory interactions identified in the 4S pathway. (A) DszA inhibition by HBP has an IC50 of 60 ± 5 μM; (B) DszB inhibition by HBP has an IC50 of 110 ± 10 μM; (C) DszC inhibition by HBPS has an IC50 of 15 ± 2 μM; (D) DszC inhibition by HBP has an IC50 of 50 ± 5 μM. Data shown are the averages and standard deviations of 3 replicates.

Table 3.

Summary of inhibition parameters for the four major inhibitory interactions, including the mechanism of inhibition, Ki, α, and IC50s

| Enzyme | Inhibitor | Mechanism | Ki (μM) | α | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DszA | HBP | Not determined | NAa | NA | 60 ± 5 |

| DszB | HBP | Not determined | NA | NA | 110 ± 10 |

| DszC | HBPS | Noncompetitive | 13.5 | 0.13 | 15 ± 2 |

| DszC | HBP | Noncompetitive | 40 | 0.4 | 50 ± 5 |

NA, not applicable.

The only prior preliminary characterization of inhibition within the 4S pathway showed that DszB from R. erythropolis KA2-5-1 had an IC50 of about 2,000 μM with respect to HBP (12). We report here three new inhibitory interactions in the pathway that are stronger than any previous preliminary findings. Note that the strongest inhibitory interactions are on the first enzyme in the pathway, DszC, and the strength of inhibition decreases farther down the pathway, with the last enzyme in the pathway, DszB, having the weakest HBP inhibition at an IC50 of 110 μM (Fig. 4B). Note also that the major inhibitory compounds in the pathway are the last two intermediates, HBPS and HBP. This pattern of inhibition is typical of feedback inhibition of linear pathways; for example, in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, the first enzyme in the pathway is strongly inhibited by the end product, ATP.

Mechanism of major inhibitory interactions in the 4S pathway.

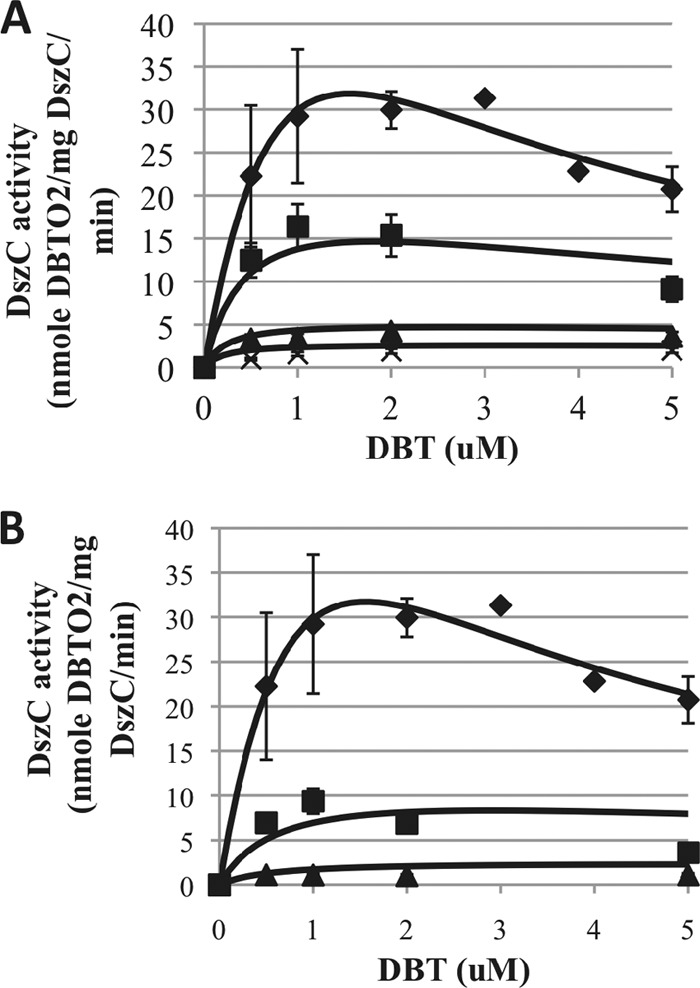

The telltale sign of noncompetitive inhibition is a reduced Vmax without a change in Km as the inhibitor concentration is increased (20). This phenomenon was observed in the inhibition of DszC by both HBPS and HBP (Fig. 5A and B). The model for noncompetitive inhibition of an enzyme that obeys Michaelis-Menten kinetics is given by (20)

| (14) |

where [I] is the inhibitor concentration, Ki is the inhibition constant, and α is a parameter that reflects the effect of the inhibitor on the affinity of the enzyme for its substrate and, likewise, the effect of the substrate on the affinity of the enzyme for the inhibitor. Noncompetitive inhibition refers to the case in which an inhibitor displays binding affinity for both the free enzyme and the enzyme-substrate binary complex (see the supplemental material). This form of inhibition is the most general case; in fact, competitive and uncompetitive inhibition can be viewed as special, restricted cases of noncompetitive inhibition in which the value of α is infinity and zero, respectively (20). Since the kinetics of DszC showed substrate inhibition, a modification to the noncompetitive model was derived (see the supplemental material). The noncompetitive inhibition of DszC by HBPS and HBP can be expressed as

| (15) |

Fig 5.

Noncompetitive inhibition of DszC by HBPS and HBP. (A) DszC activity over a range of DBT substrate concentrations from 0 to 5 μM and HBPS concentrations of 0 μM (closed diamonds), 5 μM (closed squares), 25 μM (closed triangles), and 50 μM (crosses). (B) DszC activity over a range of DBT substrate concentrations from 0 to 5 μM and HBP concentrations of 0 μM (closed diamonds), 100 μM (closed squares), and 500 μM (closed triangles). Solid lines are model fits from equation 15.

The solid lines in Fig. 5A and B represent the fits for the noncompetitive inhibition model (equation 15), where the values of Ki and α were 13.5 μM and 0.13, respectively, for HBPS inhibition and 40 μM and 0.4, respectively, for HBP. Fitting of the model to the data was attempted using nlinfit from MATLAB but was unsuccessful due to convergence issues. Instead, the parameters were determined by a graphical method outlined in section 8.3 of reference 20. The first step in this method was the construction of the double-reciprocal Lineweaver-Burk plot. To obtain the values of Ki and αKi, two secondary plots were constructed. The first of these was a Dixon plot of 1/Vmax as a function of [I], from which the value of −αKi can be determined as the x intercept. In the second plot, the slopes of the double-reciprocal lines (from the Lineweaver-Burk plot) are plotted as a function of [I]. For this plot, the x intercept is equal to −Ki. Combining the information from these two secondary plots allows determination of both inhibition parameters. The mechanism of DszB inhibition by HBP and DszA inhibition by HBPS could not be determined due to the limited resolution of the HPLC detector.

The enzyme inhibition model predicts the reduction in biocatalyst activity.

A model that incorporated enzyme inhibition was developed to predict the volumetric desulfurization rate in biphasic (oil-water) BDS experiments (see the supplemental material for the model equations). The model accounted for DBT and HBP in three components: oil, water, and cytoplasm. The two pathway intermediates, DBTO2 and HBPS, were assumed to be present only in the cytoplasm. The three major inhibitory interactions by HBP on DszA, DszB, and DszC were taken into account. The fourth major inhibitory interaction, the inhibition of DszC by HBPS, was ignored for simplicity. DszD activity was assumed to not be limiting and was therefore excluded from the model. A loss of biocatalyst activity unrelated to HBP accumulation was also taken into account in the model through an exponential decay constant, kd (see the supplemental material). The concentrations of DszA, DszB, and DszC were assumed to be all the same and equal to E0. E0 was the only floating parameter in the model. The value of E0 was obtained by allowing its value to vary until the initial desulfurization rate predicted by the model matched the measured desulfurization rate. The value of E0 obtained was 15 mg/ml, so that the total concentration of desulfurization enzymes in the cytoplasm was 45 mg/ml. This value is of the same order as the total cytoplasmic concentration of protein, which has been reported to be approximately 200 mg/ml (21).

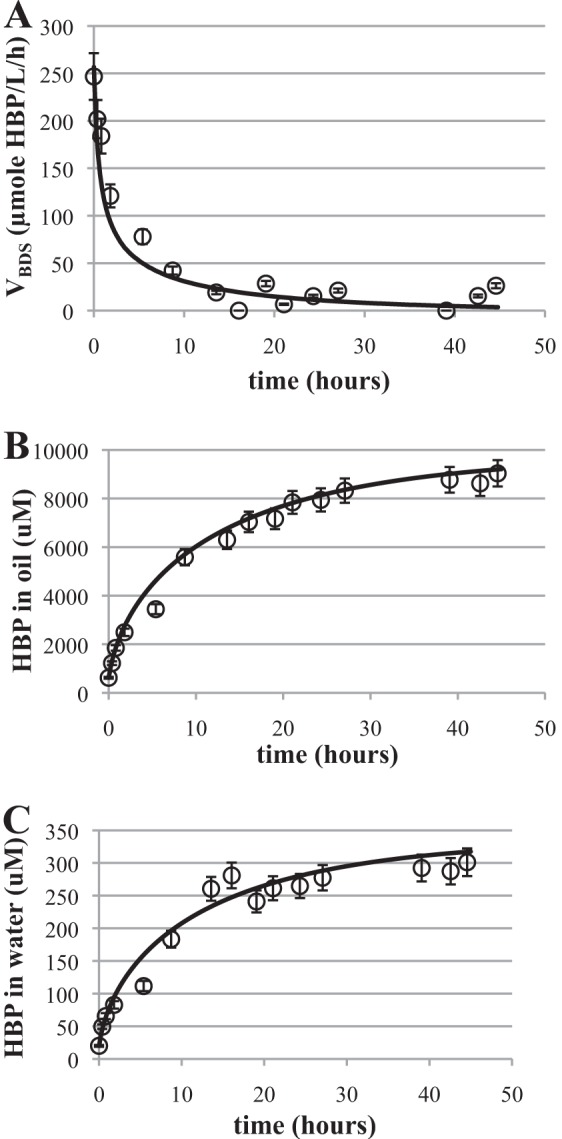

The first step in the biphasic BDS experiments was growth of biocatalyst in a 4-liter bioreactor to a cell density of 29 to 35 g DCW/liter. Next, 10% (vol/vol) hexadecane containing 100,000 μM DBT was added to the bioreactor. The desulfurization rate of DBT in the bioreactor was monitored thereafter from the measured concentrations of DBT and HBP in the hexadecane and aqueous phases. For the first 2 h after hexadecane addition, the mixing speed was maintained at 200 rpm. The mixing speed was increased to 500 rpm thereafter to minimize mass transport limitations in the system. The enzyme inhibition model was used to predict the desulfurization rate only after the shift in mixing speed to 500 rpm. The model predicts the concentration of HBP in the oil and water phases and the volumetric desulfurization rate accurately (Fig. 6A to C). The coefficient of determination (R2) between the model and the data was calculated to be 0.96 using the MATLAB function corr(X,Y).

Fig 6.

Enzyme inhibition model predictions for BDS bioreactor experiment. (A) Volumetric desulfurization rate data (circles) and model prediction (line). VBDS, volumetric desulfurization rate of BDS. (B) Concentration of HBP in the oil phase data (circles) and model (line). (C) Concentration of HBP in the water phase data (circles) and model (line). Data shown are the averages and standard deviations of 3 replicates.

DISCUSSION

Dose-response experiments were performed to investigate the potential inhibitory effect of the various intermediates in the 4S pathway on the desulfurization enzymes. Four major inhibitory interactions were identified, all of which had IC50s under 110 μM. Three of the four major inhibitory interactions were carried out by HBP. HBP was found to inhibit DszA, DszB, and DszC with IC50s of 60, 110, and 50 μM, respectively. The fourth major inhibitory interaction identified is the inhibition of DszC monooxygenase by HBPS. This interaction is the strongest of the four since it has the lowest IC50 of 15 μM. The HBPS concentration during the four-component BDS experiments was not measured in this work. The IC50s of HBP on the desulfurization enzymes were all significantly lower than the minimum cytoplasmic HBP concentration estimated during the four-component BDS experiments, which was 260 μM. This suggests that enzyme inhibition by HBP was responsible for the reduction in biocatalyst activity during the four-component BDS experiments, even in the presence of 50 g/liter of HBP-selective resin (Dowex Optipore SD-2). In the n-butanol fermentation by Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824, n-butanol productivity was increased 2-fold upon addition of Dowex Optipore SD-2 to the medium (15). However, the n-butanol toxicity threshold of Clostridium is generally considered to be about 1.3% (wt/vol), which is approximately 180 mM (15). The fact that the inhibitory levels of HBP on the R. erythropolis IGTS8 desulfurization enzymes are at least 3 orders of magnitude smaller than the toxicity levels of n-butanol on Clostridium might explain why the n-butanol productivity by Clostridium was enhanced upon addition of Dowex Optipore SD-2 and the HBP productivity by R. erythropolis IGTS8 was not enhanced.

In another study, R. erythropolis IGTS8 lysates were supplied with 200 μM DBT initially and the concentrations of DBT, DBTO2, HBPS, and HBP were monitored over time (4). After 10 min, all DBT was depleted, the HBPS concentration was approximately 130 μM, and the HBP concentration was approximately 50 μM (4). From 10 to 60 min, the HBPS concentration decreased steadily from 130 to 0 μM and the HBP concentration increased from 50 to 200 μM. No DBTO2 was detected at any time (4). All of these results agree with the kinetic data obtained in this work. First of all, since the kcat of DszA is approximately 7 times that of DszC (Table 2), the DBTO2 consumption rate is expected to be significantly greater than its generation rate, which agrees with the fact that no DBTO2 was detected. Second, the buildup of HBPS within the first 10 min is consistent with the fact that its consumption rate (DszB kcat = 1.7 min−1) is significantly slower than its generation rate (DszA kcat = 11.2 min−1) (Table 2). The fact that the HBP concentration accumulates to over 130 μM within the first few minutes indicates that DszC would have been severely inhibited by HBPS at that point in time. As HBPS is consumed, DszC inhibition by HBPS is relieved, but then HBP inhibition of DszC (and DszA and DszB) becomes more significant. Therefore, we expect that during a BDS experiment, all four major inhibitory interactions reported here would be important. HBPS inhibition of DszC is responsible for maintaining the BDS rate low at the beginning of the BDS process, when HBP levels are still low. Once HBP levels rise, HBP inhibition of DszA, DszB, and DszC is mostly responsible for inhibition of the BDS rate.

Due to the biocatalyst's high affinity for HBP relative to that of the aqueous buffer (PC/W = 60 at Xr = 0 g/liter), the intracellular HBP concentration (CHBP, intracellular) is much higher than the HBP concentration in the aqueous buffer (CHBP, water). In previous studies, HBP inhibition in biphasic (oil-water) BDS experiments has been downplayed due to the partition coefficient of HBP between oil and water (PO/W) being high (about 40 to 50) (22). It has generally been assumed that since the biocatalyst resides in the aqueous phase, the intracellular concentration of HBP is similar to the aqueous-phase concentration. This assumption is made in part because the biocatalyst's affinity for HBP has not been quantified in previous studies. We have shown that this affinity for HBP is in par with that of the oil phase. As a result, HBP retention within the biocatalyst and HBP inhibition of the desulfurization enzymes are obstacles even in biphasic BDS experiments.

The affinity of the biocatalyst for HBP is an intrinsic property of the biocatalyst and likely varies depending on the biocatalyst employed. Interactions between cyclic hydrocarbons and biological membranes have been previously investigated (23). The partition coefficients of a range of cyclic hydrocarbons (including aromatics) between liposomes prepared from E. coli phospholipids and an aqueous phosphate buffer were measured. From these measured partition coefficients, a correlation for predicting the partition coefficient of any cyclic hydrocarbon between the liposome (membrane) and the aqueous buffer (PM/B) based on the octanol-water partition coefficient (PO/W) of that cyclic hydrocarbon was developed. The liposome-buffer partition coefficient of HBP [log(PM/B)] is predicted to be 2.2, given the known value of the octanol-water partition coefficient [log(PO/W)] of 3.09 (24). This is in good agreement with the value of the partition coefficient of HBP between the biocatalyst and the buffer measured in this work [log(PC/W) = 1.8 to 2.2] (Table 1). The liposomes prepared by Sikkema et al. (23) are representative of the cytoplasmic membrane of a Gram-negative bacterium. R. erythropolis, being a Gram-positive bacterium, has a thin cytoplasmic membrane surrounded by a thick cell wall made mostly of a peptidoglycan structure and mycolic acids (10). The fact that the value of log(PC/W) measured in this study agrees well with the predicted value of log(PM/B) suggests that the HBP retained by R. erythropolis IGTS8 might reside mostly within the cytoplasmic membrane as opposed to the cell wall, which is structurally very different. This idea agrees with the mechanism of DBT-to-HBP conversion during the BDS process. When DBT is added exogenously, it is transported into the cell (likely by passive diffusion). Inside the cytoplasm, the DBT is transformed to HBP via the 4S pathway and then the HBP interacts first with the cytoplasmic membrane as it attempts to exit the cell.

Conclusions.

In this work, the mechanism of biocatalyst inhibition in the BDS of DBT was investigated. Retention of the final product (HBP) during the BDS process to concentrations in the range of hundreds of μM or higher leads to inhibition of the three enzymes in the linear part of the 4S pathway. These three enzymes, DszA, DszB, and DszC, have IC50s with respect to HBP of 60, 110, and 50 μM, respectively. Host engineering to reduce retention of HBP might mitigate inhibition of the 4S pathway by HBP. This poses a formidable challenge, as it has been suggested that the cytoplasmic membrane, which is ubiquitous in nature, may be responsible for HBP retention within the biocatalyst. Protein engineering might also be explored as a means to overcome inhibition of the pathway enzymes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A.A.-F. was supported by the Biotechnology Training Program from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Research support from Saudi Aramco is also gratefully acknowledged.

Christine Nguyen is gratefully acknowledged for synthesizing HBPS.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 October 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02696-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Soleimani M, Bassi A, Margaritis A. 2007. Biodesulfurization of refractory organic sulfur compounds in fossil fuels. Biotech. Adv. 25:570–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilbane JJ. 2006. Microbial biocatalyst developments to upgrade fossil fuels. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 17:305–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray KA, Mrachko GT, Squires CH. 2003. Biodesulfurization of fossil fuels. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:229–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray KA, Pogrebinsky OS, Mrachko GT, Xi L, Monticello DJ, Squires CH. 1996. Molecular mechanisms of biocatalytic desulfurization of fossil fuels. Nat. Biotech. 14:1705–1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xi L, Squires CH, Monticello DJ, Childs JD. 1997. A flavin reductase stimulates DszA and DszC proteins of Rhodococcus erythropolis IGTS8 in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 230:73–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watkins LM, Rodriguez R, Schneider D, Broderick R, Cruz M, Chambers R, Ruckman E, Cody M, Mrachko GT. 2003. Purification and characterization of the aromatic desulfinase 2-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)benzenesulfinate desulfinase. Biochem. Biophys. 415:14–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schilling BM, Alvarez LM, Wang DIC, Cooney CL. 2002. Continuous desulfurization of dibenzothiophene with R. rhodochrous IGTS8 (ATCC 53968). Biotechnol. Prog. 18:1207–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naito M, Kawamoto T, Fujino K, Kobayashi M, Maruhashi K, Tanaka A. 2001. Long-term repeated desulfurization by immobilized Rhodococcus erythropolis KA2-5-1 cells. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 55:374–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jia X, Wen J, Sun Z, Caiyin Q, Xie S. 2006. Modeling of DBT biodegradation behaviors by resting cells of Gordonia sp.WQ-01 and its mutant in oil-water dispersions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 61:1987–2000 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lichtinger T, Reiss G, Benz R. 2000. Biochemical identification and biophysical characterization of a channel-forming protein from Rhodococcus erythropolis. J. Bacteriol. 182:764–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honda H, Sugiyama H, Saito I, Kobayashi T. 1998. High cell density culture of Rhodococcus rhodochrous by pH-stat feeding and dibenzothiophene degradation. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 85:334–338 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakayama N, Matsubara T, Ohshiro T, Moroto Y, Kawata Y, Koizumi K, Hirakawa Y, Suzuki M, Maruhashi K, Izumi Y, Kurane R. 2002. A novel enzyme, 2′-hydroxybiphenyl-2-sulfinate desulfinase (DszB), from a dibenzothiophene-desulfurizing bacterium Rhodococcus erythropolis KA2-5-1: gene overexpression and enzyme characterization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1598:122–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caro A, Boltes K, Leton P, Garcia-Calvo E. 2008. Description of by-product inhibition effects on biodesulfurization of dibenzothiophene in biphasic media. Biodegradation 19:599–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen H, Zhang WJ, Cai YB, Zhang Y, Li W. 2008. Elucidation of 2-hydroxybiphenyl effect on dibenzothiophene desulfurization by Microbacterium sp. strain ZD-M2. Bioresour. Technol. 99:6928–6933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen DR, Prather KJ. 2009. In situ product recovery of n-butanol using polymeric resins. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 102:811–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutcliffe IC, Brown AK, Dover LG. 2010. The rhodococcal cell envelope: composition, organization and biosynthesis. Biology of Rhodococcus. Microbiology monographs 16. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilbane JJ. April 1992. Mutant microorganisms useful for cleavage of organic C-S bonds. US patent 5,104,801

- 18.Shuler ML, Kargi F. 2002. Bioprocess engineering: basic concepts, 2nd ed. Prentice Hall, Inc, Upper Saddle River, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohshiro T, Suzuki K, Izumi Y. 1997. Dibenzothiophene (DBT) degrading enzyme responsible for the first step of DBT desulfurization by Rhodococcus erythropolis D-1: purification and characterization. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 83:233–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Copeland RA. 2000. Enzymes: a practical introduction to structure, mechanism, and data analysis, 2nd ed, p 397 Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellis RJ. 2001. Macromolecular crowding: obvious but underappreciated. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26:597–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caro A, Boltes K, Leton P, Garcia-Calvo E. 2007. Dibenzothiophene biodesulfurization in resting cell conditions by aerobic bacteria. J. Biochem. Eng. 35:191–197 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sikkema J, de Bont JAM, Poolman B. 1994. Interactions of cyclic hydrocarbons with biological membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 269:8022–8028 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansch C, Leo A, Hoekman D. 1995. Exploring QSAR, p 97 American Chemical Society, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsubara T, Ohshiro T, Nishina Y, Izumi Y. 2001. Purification, characterization, and overexpression of flavin reductase involved in dibenzothiophene desulfurization by Rhodococcus erythropolis D-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1179–1184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.