Abstract

Drug resistance mutations (DRMs) have been reported for all currently approved anti-HIV drugs, including the latest integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs). We previously used the new INSTI dolutegravir (DTG) to select a G118R integrase resistance substitution in tissue culture and also showed that secondary substitutions emerged at positions H51Y and E138K. Now, we have characterized the impact of the G118R substitution, alone or in combination with either H51Y or E138K, on 3′ processing and integrase strand transfer activity. The results show that G118R primarily impacted the strand transfer step of integration by diminishing the ability of integrase-long terminal repeat (LTR) complexes to bind target DNA. The addition of H51Y and E138K to G118R partially restored strand transfer activity by modulating the formation of integrase-LTR complexes through increasing LTR DNA affinity and total DNA binding, respectively. This unique mechanism, in which one function of HIV integrase partially compensates for the defect in another function, has not been previously reported. The G118R substitution resulted in low-level resistance to DTG, raltegravir (RAL), and elvitegravir (EVG). The addition of either of H51Y or E138K to G118R did not enhance resistance to DTG, RAL, or EVG. Homology modeling provided insight into the mechanism of resistance conferred by G118R as well as the effects of H51Y or E138K on enzyme activity. The G118R substitution therefore represents a potential avenue for resistance to DTG, similar to that previously described for the R263K substitution. For both pathways, secondary substitutions can lead to either diminished integrase activity and/or increased INSTI susceptibility.

INTRODUCTION

The HIV integrase (IN) enzyme catalyzes the insertion of viral DNA into host DNA, a process known as integration (1). In a reaction termed 3′ processing, integrase recognizes and cleaves off a dinucleotide GT downstream of a conserved dinucleotide CA signal, located within the last 15 bp of the long terminal repeats (LTR) that flank the viral DNA, and this effectively creates new 3′ hydroxyl ends (2). The second step in integration, termed strand transfer, is the integrase-mediated insertion of the processed viral DNA into host DNA by a 5-bp staggered cleavage of target DNA. The exposed 3′ hydroxyl groups on the viral insert interact with exposed 5′ phosphates on the host DNA. Integration, which occurs primarily in highly expressed genes (3), causes the host machinery to transcribe viral genes and leads to successful propagation of viral particles. Integration is essential for productive infection and the establishment of viral persistence; therefore, integration was an early choice for the development of inhibitory compounds (4).

The development of in vitro microtiter plate-based biochemical assays for the measurement of the various biochemical activities of integrase facilitated compound screening and identification of viable integrase inhibitors (5). The first specific integrase inhibitors, identified in 2000 (5), possessed diketoacid motifs and targeted the strand transfer activity of integrase; these compounds were thus termed integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs). The first INSTIs to be approved for therapy were raltegravir (RAL) in 2007 (6) and elvitegravir (EVG) in 2012 (7). These compounds have been shown to be highly potent bioavailable inhibitors of integrase strand transfer (8) but have demonstrated low-moderate genetic barriers to the development of drug resistance substitutions (DRMs) (9). There are three major pathways that are involved in resistance for RAL, commencing with substitutions at any of positions 155, 143, and 148 (9–11); EVG exhibits extensive cross-resistance with RAL due to substitutions at positions 155 and 148 (9, 12–14) and demonstrates other resistance pathways as well. This cross-resistance between RAL and EVG has necessitated the development of other INSTIs that possess higher barriers to resistance development as well as nonoverlapping resistance profiles.

A newer INSTI, dolutegravir (DTG), has been shown in both preclinical and clinical studies to have higher potency and a higher barrier to resistance than either RAL or EVG (15). DTG (8, 16–23) also binds to integrase protein with a longer residence time than either RAL and EVG (24) and has yet to select for resistance substitutions in HIV-positive previously antiretroviral (ARV)-naive patients receiving ARVs for the first time, despite having been used over a period of 96 weeks (20, 21, 25). It is important to better understand the resistance profile of DTG as well as to determine whether differences in HIV subtype might ultimately affect the clinical performance of this drug.

We previously identified a G118R substitution in the integrase of subtype C HIV through cell culture selections; G118R resulted in moderate levels of resistance to an experimental INSTI, MK-2048 (26), and was also observed in a patient harboring HIV-1 CRF02_A/G virus to whom it conferred high-level resistance to RAL (27). Prior to these reports, G118ACR mutants had been selected only in cell culture with the early INSTI S-1360, resulting in resistance to this compound (28). More-recent cell culture selections with DTG selected for the G118R substitution in subtype C and CRF02_A/G clonal viruses but not in subtype B viruses (29). In our MK-2048 selections, E138K was a secondary substitution that appeared after G118R and seemed to partially rescue its replication activity as well as to enhance levels of resistance to MK-2048 (26); E138K was also observed as a secondary substitution in one instance alongside R263K, the most common substitution associated with resistance to DTG in selection studies (29), although the role of E138K in the R263K resistance pathway has not been characterized. The primary RAL substitutions Q148H/K/R are often found together with E138K as a second or third substitution, and in this context, E138K has been shown to restore fitness and enhance resistance (8, 11).

The H51Y substitution was first reported as a secondary substitution to E92Q in the context of EVG treatment. It has also recently been observed as a secondary substitution to both R263K and G118R in DTG passage experiments (29, 30). In our recently published work, we observed that the double mutant H51Y/R263K had lower LTR binding affinity and resulted in a virus that was less fit and less infectious than that containing only R263K (30).

Here we present a biochemical characterization of subtype B integrase proteins that harbor the G118R substitution, in isolation or in combination with either of the secondary substitutions H51Y and E138K. We investigated the impact of these substitutions on the strand transfer activity of integrase and its ability to bind to substrates, i.e., the LTR and target DNA. We also present homology modeling of the active site of integrase, based on the published foamy virus (PFV) strand transfer complex (STC) (31), and explain the cross-resistance profiles of integrase proteins for the three clinically relevant INSTIs, i.e., DTG, RAL, and EVG. This work provides a detailed analysis of mechanistic, structural, and sequence-specific factors that may affect the in vivo development and maintenance of resistance substitutions and may be instrumental in predicting resistance pathways for INSTIs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antiviral compounds.

The integrase inhibitor drug RAL was provided by Merck & Co. Inc.; EVG and DTG were kindly provided by Gilead Sciences and GlaxoSmithKline, respectively. Prior to use, compounds were solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at −20°C. All other reagents used were enzyme grade and of the highest available purity.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

The generation of a pET-15b expression plasmid containing soluble wild-type (WT) HIV subtype B integrase has already been described (32, 33). PCR-mediated site-directed mutagenesis was performed on this plasmid to yield plasmid DNA encoding the G118R substitution, either in isolation or together with one of two additional substitutions, H51Y and E138K. The following primers were used for mutagenesis: G118R (CCAGTAAAAACAGTACATACAGACAATCGCAGCAATTTCACC); G118R_antisense (GGTGAAATTGCTGCGATTGTCTGTATGTACTGTTTTTACTGG); H51Y (CTAAAAGGGGAAGCCATGTATGGACAAGTAGACTGTA); H51Y_antisense (TACAGTCTACTTGTCCATACATGGCTTCCCCTTTTAG); E138K_sense (GGCGGGGATCAAGCAGAAATTTGGCATTCCCTA); and E138K_antisense (TAGGGAATGCCAAATTTCTGCTTGATCCCCGCC). Plasmid DNA was amplified and maintained in Escherichia coli XL10-Gold ultracompetent cells [Tetr Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac Hte], [F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10(Tetr) Amy Camr] (Stratagene). Successful mutagenesis was confirmed by sequencing (Genome Quebec).

Protein expression, purification, and quantification.

Plasmids bearing either a WT or a G118R-mutated IN gene were transformed into BL21(DE3) Gold cells [F− ompT hsdS(rB− mB−) dcm+ Tetr gal λ(DE3) endA Hte] (Stratagene) for protein expression. Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (Multicell), prepared in MilliQ water and supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin, was used for all bacterial growth. Expression and purification of integrase recombinant proteins were performed as previously described for His-tagged integrase (29). Fractions containing purified integrase as judged by SDS-PAGE were dialyzed into storage buffer (20 mM HEPES, 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM [DTT], 10% glycerol, pH 7.5) with a molecular cutoff of 30 kDa. Protein concentrations were measured using a calculated extinction coefficient of 50,420 M−1 cm−1 (29). Protein aliquots could be kept for several months at −80°C without significant loss of activity or integrity.

DNA substrates for in vitro assays.

All oligonucleotide substrates were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT; Coralville, IA). The following oligonucleotides were used for strand transfer assays: preprocessed donor LTR DNA sense A (5′amino-modifier with 12-carbon linker [AmMC12]-ACCCTTTTAGTCAGTGTGGAAAATCTCTAGCA-3′) and antisense B (5′-ACTGCTAGAGATTTTCCACACTGACTAAAAG-3′) and target DNA sense C (5′-TGACCAAGGGCTAATTCACT-3′ biotin [3Bio]-3′) and antisense D (5′-AGTGAATTAGCCCTTGGTCA-3Bio-3′). The following oligonucleotides were used for LTR DNA binding assays: E (5′-CTTTTAGTCAGTGTGGAAAATCTCTAGCAGT-3′) and F (5′rhodamine cross-linked at amino terminus to DNA [/Rhodamine-XN/]ACTGCTAGAGATTTTCCACACTGACTAAAAG-3′). For 3′ processing assays, primer B was used together with LTR 3′ sense oligonucleotide G (5′AmMC12-ACCCTTTTAGTCAGTGTGGAAAATCTCTAGCAGT-BioTEG-3′). All these oligonucleotides have been previously described (29, 30, 34, 35). Functional DNA duplexes were made by combining equimolar amounts of sense and antisense primers to appropriate concentrations in low-chelate TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.8), heated for 10 min at 95°C, and annealed by slow cooling to room temperature over a period of 4 h. Duplexes were stored at −20°C for several months without loss of integrity.

Preparation of preprocessed LTR-coated plates for strand transfer activity.

An 80-μl volume of preprocessed viral LTR-mimic (donor DNA) duplex A/B, diluted to 150 nM (except as dictated by experiment design) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) (Bioshop), was covalently linked to Costar DNA-Bind 96-well plates (Corning catalog no. 2499) by overnight incubation at 4°C; negative-control wells lacked any DNA duplex. The plates were blocked with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in blocking buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.8], 150 mM NaCl) and were stored in blocking buffer for several weeks without detectable loss in integrity. Before use, the plates were washed twice with each of PBS (pH 7.4) and assay buffer (50 mM MOPS [morpholinepropanesulfonic acid; pH 6.8], 50 μg/ml BSA, 50 mM NaCl, 0.15% CHAPS {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate}, 30 mM MnCl2/MgCl2) except as dictated by experimental design.

Protein calibration for strand transfer activity.

The optimum concentration of protein to use in subsequent strand transfer experiments was determined by titrating the protein concentration (effective [protein] = 0 to 1.8 μM) in the presence of various target DNA concentrations (0 to 128 nM). Preprocessed LTR-coated plates were prepared as described above. Purified integrase proteins, diluted appropriately in assay buffer supplemented with 5 mM DTT, were added followed by a 30-min incubation at room temperature to allow for assembly of integrase onto the preprocessed LTR duplexes. Biotinylated target DNA duplex C/D was added, and the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C (except when specified otherwise) for the strand transfer reaction to occur. The plates were then rinsed three times with wash buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, 0.2 mg/ml BSA) and incubated with Eu-labeled streptavidin (Eu-Streps; PerkinElmer) diluted to 0.025 μg/ml in wash buffer supplemented with 50 μM DTPA (diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid) (Sigma). After additional rinses with wash buffer, 100 μl of Wallac enhancement solution (PerkinElmer) was added. Ionization of conjugated Eu to free aqueous Eu3+ is caused by the low pH of the enhancement solution (pH < 4). Excitation of Eu3+ ions by incident wavelength at 355 nm resulted in time-resolved emission of fluorescence (TRF) that was measured at 612 nm on a FLUOStar Optima multilabel plate reader (BMG Labtech) in TRF mode.

Protein concentrations that yielded the highest activity (300 nM) as measured by relative fluorescence units (RFU) were chosen for subsequent experiments. A common target concentration was also chosen in this experiment for subsequent experiments.

Time-phase strand transfer activity assay.

Preprocessed LTR plates were prepared and washed as described above. A 50-μl volume of reaction buffer (assay buffer supplemented with 5 mM DTT) was then added to each well. At time intervals of 10 min, 50 μl of 3× WT integrase enzyme (900 nM) was added to one column of wells followed immediately by addition of 50 μl of target DNA (0 to 128 nM). Incubation at 37°C followed immediately to initiate the transfer reaction in that column. All transfers between the incubator and pipetting station were done with the aid of heating blocks precalibrated to 38°C; this reduced temperature variations that might have impacted ongoing strand transfer reactions. After 2 h, integrase and target were added to the final column and the plates were immediately inverted to stop the reactions. The plates were quickly washed three times with wash buffer to remove all traces of unreacted protein and target. All subsequent steps of the assay were as described above for the strand transfer assay. Following detection of TRF, the raw data were processed in GraphPad Prism V5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) using Michaelis-Menten settings and kinetic parameters obtained for the particular enzyme employed. Departures from linearity for data points in the range of 0 to 70 min were tested using linear regression analysis in GraphPad Prism. The means of the results of at least three independent experiments are reported.

Fixed-[LTR]-variable-[target] strand transfer activity assay.

In order to obtain kinetic activity parameters for WT and variant integrase proteins, strand transfer reactions were carried out as described based on the same design as that for the protein calibration assay described above. The major difference is that the effective LTR and integrase concentrations 80 nM and 300 nM, respectively, were used for these assays. All other experimental procedures were as described above. The means of the results of at least three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate for each integrase protein, were calculated. The data were analyzed using Michaelis-Menten kinetics in GraphPad Prism.

Variable-[LTR]-variable-[target] strand transfer activity assay.

In order to test the binding dynamics of LTR mimic and target DNA, 12 concentrations of preprocessed LTR DNA mimic (effective assay concentrations: 0 to 160 nM) were used to coat Costar DNA-Bind 96-well plates as described above. The plates were incubated overnight at 4°C, followed by an overnight incubation with blocking buffer (4°C). An equimolar amount of integrase (effective concentration = 450 nM) was added to each well followed by 50 μl of 0 to 128 nM target DNA. The plates were then incubated at 37°C. After 1 h, the reaction was stopped by inversion of the plates followed by appropriate washing and the Eu-Streps hybridization and detection steps. Data for three independent experiments for each integrase protein were fitted by GraphPad Prism to the user-defined bisubstrate equilibrium-ordered kinetic equation (36, 37) shown below:

In the equations above, A represents [LTR] in nM, B represents [target] in nM, Kia refers to the stability of the enzyme-LTR complex, V refers to enzyme activity in RFU/h, Vmax refers to the maximum activity in RFU/h, and KApp refers to the apparent Km for the target observed for a given concentration of LTR. To reflect the likely order of substrate addition in vivo, LTR was assumed to bind first, followed by target DNA.

LTR DNA binding assay.

The LTR binding ability of our purified integrase proteins was measured as previously described (34). Briefly, Corning 96-well black flat-bottom polystyrene high-Bind microplate wells (Corning catalog no. 3925) were coated overnight at 4°C with HIV integrase proteins (500 nM) diluted in PBS (pH 7.4); negative-control wells were incubated only with PBS. Unbound proteins were removed by rapid inversion and subsequent washing with 200 μl/well of PBS (pH 7.4). The plates were then blocked with 200 μl of PBS (pH 7.4) containing 5% BSA at room temperature for 2 h. After blocking, the coated plates were washed twice with PBS and once with binding buffer (20 mM MOPS [pH 7.2], 20 mM NaCl, 7.5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT). Fluorescently labeled RhoR-LTR (duplex E/F, 0 to 200 nM) was then added into each well, and the plates were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 1 h. After the incubation, the reaction mixtures were removed by rapid inversion and plates washed 3 times with 200 μl of PBS. After removal of the final wash, 100 μl of PBS was added to each well and the fluorescent signals were measured at an excitation wavelength of 544 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm using a FLUOstar Optima plate reader.

Control reactions without IN (protein free) or LTR were performed under the same reaction conditions to monitor the background signal (Bbackground). Reactions with immobilized HIV-1 IN under different conditions were performed to measure the total binding activity (Btotal). The HIV-1 IN DNA binding activity for each sample was calculated using the following equation:

To determine the apparent dissociation constant (Kd) value, IN (500 nM) was incubated with increasing concentrations of RhoR-LTR (from 0 to 200 nM), and the Kd value was calculated by directly fitting the titration curve using GraphPad Prism with nonlinear one-site binding regression.

3′ Processing assay.

The determination of the 3′ processing activity of the purified recombinant integrase proteins was performed as previously described (35). Briefly, 3′ biotinylated LTR duplex G/B was covalently linked at various concentrations (0 to 36 nM) to Costar DNA-Bind plates under conditions similar to those described for strand transfer. To initiate 3′ processing, purified integrase protein (300 nM) in reaction buffer (50 nM MOPS [pH 6.8], 50 mg/ml BSA, 50 mM NaCl, 20 mM MnCl2, 0.015% CHAPS, 5 mM DTT) and the plates were incubated at 37°C. Protein negative-control wells had only reaction buffer added. After 2 h of incubation, the plate was quickly washed three times with wash buffer to remove all traces of protein and cleaved 3′GT-Bioteg. All subsequent steps of the assay were as described above for the strand transfer assay with the exception of data analysis. For each plate and concentration of LTR, four protein negative controls contained unprocessed LTR and the average signal from these represented the maximum possible TRF signal (3′OHmax). For each protein, the TRF signal observed (3′OHobs) represented unprocessed LTR. Thus, the TRF signal representing actual 3′ processing activity (3′OHactual) was determined by the following equation: (3′OHactual) = (3′OHmax) − (3′OHobs).

The calculated 3′ processing readings (n ≥ 8) were then processed in GraphPad Prism to yield 3′ processing kinetic parameters for the particular integrase protein employed.

Competitive inhibition of strand transfer inhibition by DTG, RAL, and EVG.

The susceptibilities of our purified integrase proteins to INSTIs were tested in competitive inhibition assays using the compounds DTG, RAL, and EVG. Drug stock solutions were prepared as 6× working solutions at a concentration of 6 μM and subsequently serially diluted 4-fold in compound dilution buffer (assay buffer containing 10% DMSO) to concentrations between 1.2 and 6,000 nM; inhibition assays were performed in the presence of various target DNA concentrations (0 to 128 nM). Briefly, preprocessed LTR-coated plates (effective LTR concentration = 160 nM) were prepared as described above. Purified integrase proteins (effective concentration = 300 nM) in assay buffer supplemented with 5 mM DTT were added to each well followed by a 30-min incubation at room temperature to allow for assembly of integrase onto the preprocessed LTR duplexes. A 25-μl volume of appropriately diluted compound was added to each well followed immediately by 25 μl of appropriately diluted biotinylated target DNA duplex. The plates were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C, followed by the usual post-strand transfer steps described above. Data from three independent competition assays for each protein were fitted to the competitive inhibition algorithm using GraphPad Prism. Inhibitory constants (Ki) calculated by this algorithm were transformed to fold change (FC) values by division with the Ki value for WT B integrase enzyme.

Data processing.

All data from the cell-free experiments presented here, except when otherwise indicated, were the result of at least 3 independent sets of experiments. When relevant, statistical significances of differences between data sets for two or more integrase proteins were determined using a one-sample two-tailed t test. Probability values equal to or below 0.05 (P ≤ 0.05) were used to indicate statistically significant differences between different protein results.

Homology modeling.

Homology models of the HIV-1 integrase strand transfer complex (STC) were created based on the STC (31) of PFV. Amino acid sequences that were of WT origin or that had been point mutated at desired positions were submitted to the I-TASSER three-dimensional (3D) protein prediction server (38); the prototype foamy virus (PFV) crystal structure (Protein Data Bank identification no. [PDB ID] 3OY9) (31) was selected as a lead template for the modeling. Rotamer orientations for key residues in the active site, especially the mutated residues, were interrogated; whenever possible, the best backbone-dependent rotamers were selected (39, 40). Model quality was assessed based on root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the global homology structure from the PFV lead template using the RCSB PDB Protein Comparison Tool. Superimposition of the HIV-1 homology models with the published cocrystal structures of PFV with DTG (PDB ID 3S3M) (41), RAL (PDB ID 3OYA) (31), and EVG (PDB ID 3L2U) (31) provided insights into the mechanism of resistance caused by G118R substitution in regard to these three INSTIs. DNA interaction hints were obtained by overlaying the HIV-1 homology models with the PFV crystal structure PDB ID 4E7K, representing the target capture complex (TCC) (42). The molecular visualization program PyMOL (http://pymol.org/) (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3; Schrödinger, LLC) was used for structural visualization and image processing.

RESULTS

Generation of recombinant integrase proteins and calibration of enzyme activity.

HIV integrase-encoding plasmids that carried the G118R substitution alone or in combination with either of the H51Y or E138K substitutions were created. Generation of the G118R substitution was by a single G→C nucleotide change at position 118 in integrase from GGC to CGC; the other two substitutions, H51Y and E138K, occurred by the more common G→A single-base-pair changes. Mutated or WT proteins were expressed in and purified from E. coli BL-21 DE3 cells to greater than 90% homogeneity (Fig. 1A).

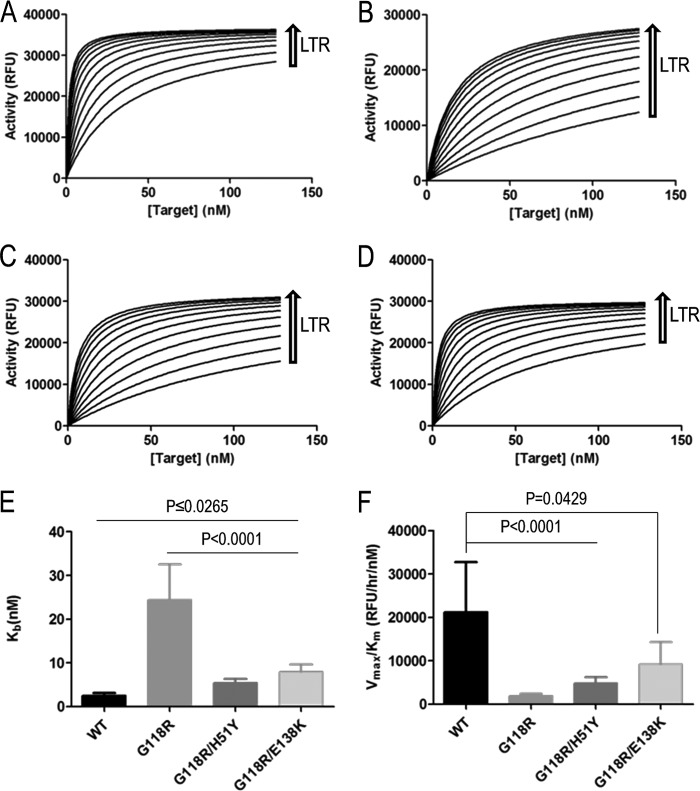

Fig 1.

Generation and quantitation of drug-resistant HIV-1 integrase proteins. (A) Successful purification of integrase (white arrowhead) proteins was confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis. (B) Optimum protein and target DNA concentrations were determined by performing strand transfer reactions in the presence of various concentrations of integrase protein. Although these experiments were performed for all the proteins tested at concentrations ranging from 37 to 1,800 nM, only wild-type results determined at concentrations between 150 and 1,200 nM are shown.

The HIV integrase protein has been shown to lose activity at high concentrations due to nonspecific aggregation (1, 43–45), and it is thus necessary to determine the dynamic range of its activity before its use in enzyme assays. In order to determine appropriate protein and target DNA concentrations, the strand transfer activity of both WT and mutated integrase preparations was monitored as previously described (29) in the presence of various protein concentrations (37 nM to 1,800 nM) and target DNA concentrations (0 to 256 nM) (Fig. 1B). From these experiments, an optimum integrase protein concentration of 300 nM and a maximum target DNA concentration of 128 nM were employed; significant differences were not observed between variants and/or purifications. Since most of our experiments were performed for a fixed period of 1 h, we confirmed that the results using WT enzyme were within the linear phase of the strand transfer reaction over this time through the use of time-resolved activity assays (not shown).

G118R causes a deficit in integrase strand transfer activity.

The G118R substitution had previously been shown by our group to reduce viral replication and infectivity; the addition of E138K partially rescued this defect (26). We also showed that the addition of H51Y to R263K further reduced each of strand transfer activity, viral replication, and infectiousness (30). In both cases, neither H51Y nor E138K alone had any significant effect on integration and/or viral replication or infectivity (30).

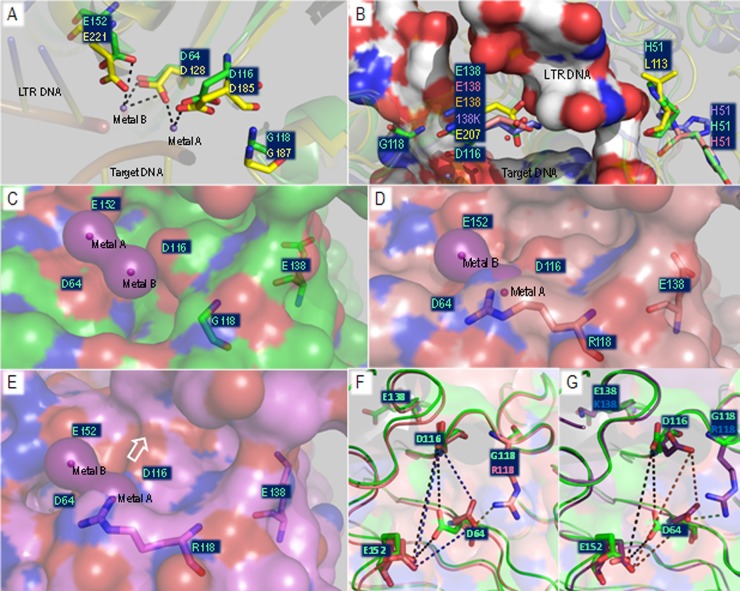

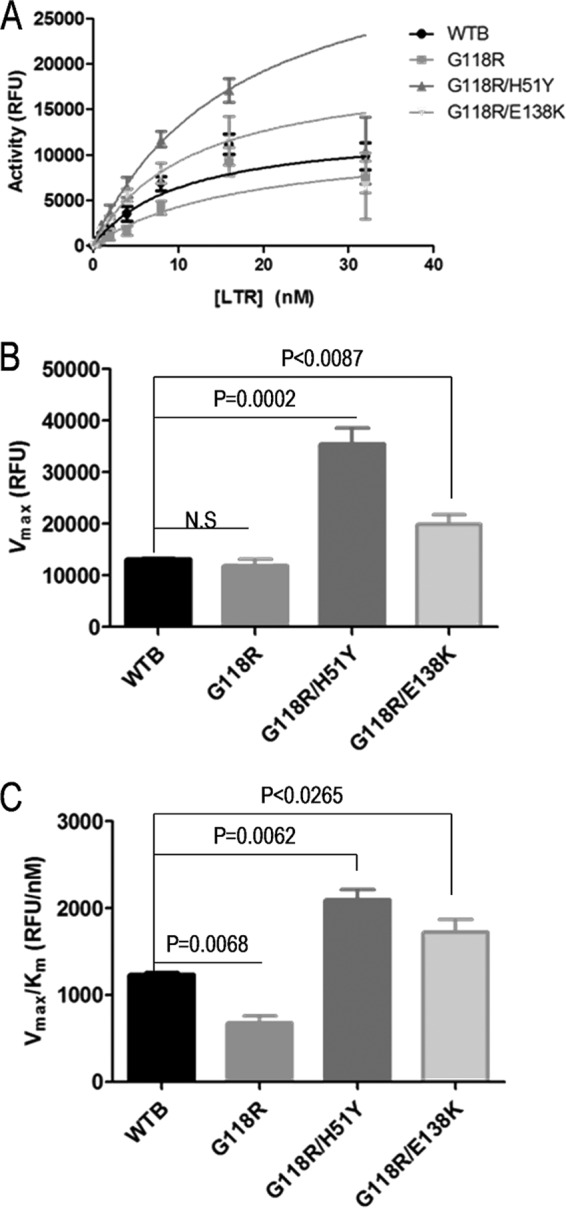

We wished to confirm that the partial rescue of G118R by E138K occurred at the level of strand transfer. To study this, we used preprocessed LTR in our assays and decoupled the strand transfer activity of integrase from its 3′ processing activity to uniquely examine strand transfer. Target saturation strand transfer experiments were performed using fixed concentrations of integrase protein (300 nM) and viral LTR mimic (80 nM) at variable target DNA concentrations (0 to 128 nM) (Fig. 2). In agreement with previous work (26), the presence of G118R resulted in >50% loss in maximal strand transfer activity (Vmax); this loss was partially rescued by the addition of H51Y and E138K (Fig. 2A). The Km for the strand transfer reaction for the G118R enzyme was increased by ∼10-fold over that of the WT, indicating lower target DNA affinity, and the addition of E138K reduced this deficit to ∼6-fold, although this effect was not statistically significant (Table 1).

Fig 2.

Strand transfer activities of purified recombinant integrase proteins at target saturation. (A and B) Strand transfer activities were measured using an immobilized preprocessed LTR plate-based assay. Graph Pad Prism was used to transform TRF data using the Michaelis-Menten functionality to obtain Vmax (A) and Km (B) values. (C) Enzyme performance was determined by division of Vmax by Km. Data represent the means of the results of at least 3 independent experiments each performed in triplicate (n ≥ 9). Error bars represent the standard errors of the means (SEM). Statistical significance was calculated for individual pairs of data using a one-sample two-tailed test with a statistical cutoff of P ≤ 0.05. N.S., not significant.

Table 1.

Strand transfer activity parameters for purified integrase proteinsa

| Subtype B integrase protein | Fixed [LTR]-strand transfer activity |

Variable-LTR/variable-target assay |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vmax ± SEM (RFU/h) | Target Km ± SEM (nM) | Vmax/Km ± SEM (RFU/h/nM) | Vmax ± SEM (RFU/h) | Target Km ± SEM (nM) | Vmax/Km ± SEM (RFU/h/nM) | |

| Wild type | 21,300 ± 1,371 | 2.13 ± 0.42 | 10,208 ± 1,842 | 18,896 ± 4,460 | 2.54 ± 0.562 | 21,273 ± 11,493 |

| G118R | 10,815 ± 2,185 | 22.0 ± 7.21 | 458 ± 21 | 20,490 ± 2,870 | 24.5 ± 8.80 | 1,962 ± 473 |

| G118R/H51Y | 16,615 ± 1,987 | 24.3 ± 6.72 | 880 ± 141 | 19,715 ± 3,242 | 5.43 ± 0.886 | 4,886 ± 1,303 |

| G118R/E138K | 12,730 ± 4,001 | 13.2 ± 7.84 | 995 ± 45 | 19,793 ± 2,644 | 8.00 ± 1.65 | 9,278 ± 4,989 |

Km = Kb from variable-LTR/variable-target assays. All data represent the results of at least 3 independent experiments.

Since in vivo enzyme activity does not differentiate between Vmax and Km effects, enzyme performance calculations (Vmax/Km) can be used to assess the effect of substitutions in enzymes in vivo, when substrates may be in limiting concentration (46). Additionally, this analysis provides a more accurate representation of the activity of single-turnover enzymes such as integrase (47). We observed that G118R caused an ∼96% reduction in enzyme performance and that the secondary substitutions H51Y and E138K minimally rescued activity by 2% and 4%, respectively (Fig. 2C). Only the E138K rescue reached statistical significance (P = 0.007).

Addition of H51Y and E138K to G118R regulates the formation of integrase-LTR complexes.

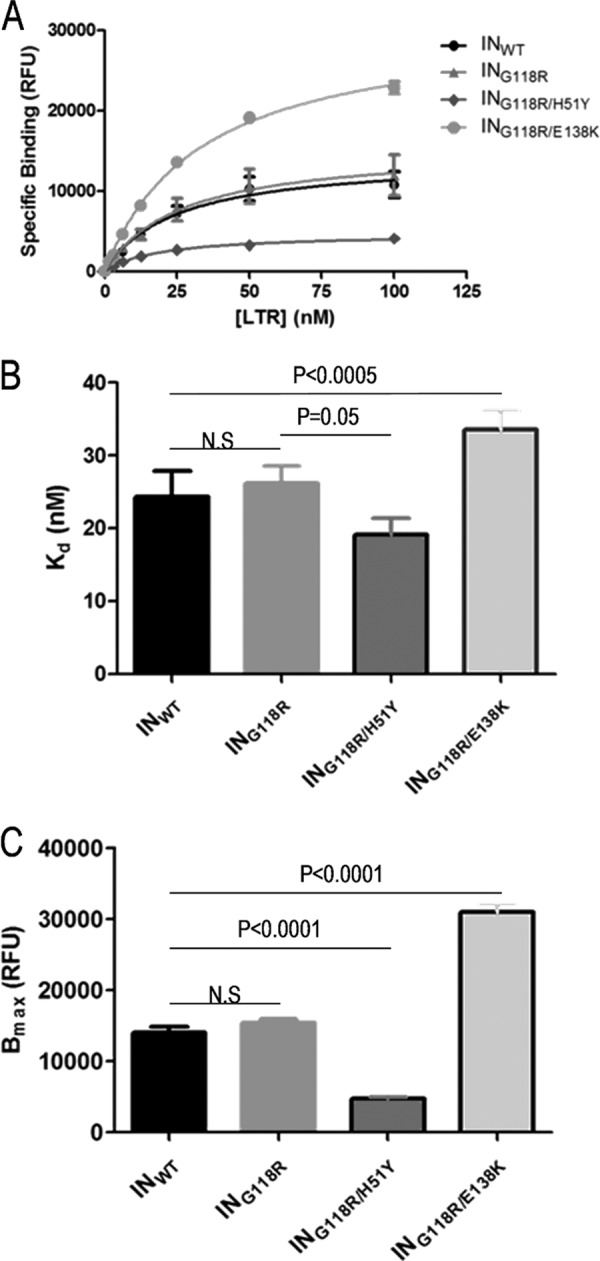

The ability of integrase to bind viral LTR impacts on the efficiency of the strand transfer reaction (45). We thus investigated if the loss in enzyme activity and performance, attributed to the G118R substitution, was related to deficits in LTR affinity or solely to deficits in target DNA binding and catalytic activity. A LTR DNA binding assay, performed as previously described (34), showed that G118R did not affect either the dissociation constant (Kd) or the ability of integrase to bind to the LTR mimic in our assay (Fig. 3). The Kd values for WT integrase in these experiments were in agreement with previous reports (34, 47, 48) (Table 2). Binding of LTR by G118R/H51Y integrase was tighter than that by WT enzyme, indicating an increase in substrate selectivity, but was associated with a reduction in total LTR bound (Fig. 3). The G118R/E138K integrase variant showed less-tight binding to the LTR (Fig. 3A and B) but possessed twice the maximal LTR binding ability of the WT enzyme (Fig. 3A and C). Taken together, these results suggest that a deficit in target DNA binding but not LTR DNA usage may account, at least in part, for the diminished enzymatic performance of the G118R integrase. The partial compensatory mechanism described here for both the H51Y and E138K secondary substitutions has not been reported previously.

Fig 3.

LTR binding experiments using purified integrase proteins. IN DNA binding reactions were performed with various concentrations of RhoR-LTR and were fitted to nonlinear one-site binding regression equations (A) to obtain values of Kd (B) and Bmax (C). Data represent the means of the results of at least 3 independent experiments each performed in duplicate (n ≥ 6). Error bars represent the standard errors of the means (SEM). Statistical significance was calculated for individual pairs of data using a one-sample two-tailed test with a statistical cutoff of P ≤ 0.05. N.S. = not significant.

Table 2.

3′ Processing parameters for purified integrase proteinsa

| Subtype B integrase protein | LTR binding assay |

3′ Processing assay |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd ± SEM (nM) | Bmax ± SEM (RFU) | Vmax ± SEM (RFU) | LTR Km ± SEM (nM) | Vmax/Km ± SEM (RFU/nM) | |

| Wild type | 24.2 ± 3.58 | 14,079 ± 796.5 | 13,101 ± 217 | 10.6 ± 0.46 | 1,235 ± 18.8 |

| G118R | 26.2 ± 2.42 | 15,419 ± 559.1 | 11,887 ± 1,292 | 17.9 ± 3.99 | 675 ± 46.3 |

| G118R/H51Y | 19.1 ± 2.24 | 4,715 ± 198.2 | 35,497 ± 3,098 | 17.0 ± 2.42 | 2,099 ± 68.2 |

| G118R/E138K | 33.5 ± 2.55 | 31,022 ± 1,002 | 19,958 ± 1,903 | 11.7 ± 2.04 | 1,727 ± 81.6 |

All data represent the results of at least 4 independent experiments, each performed in duplicate.

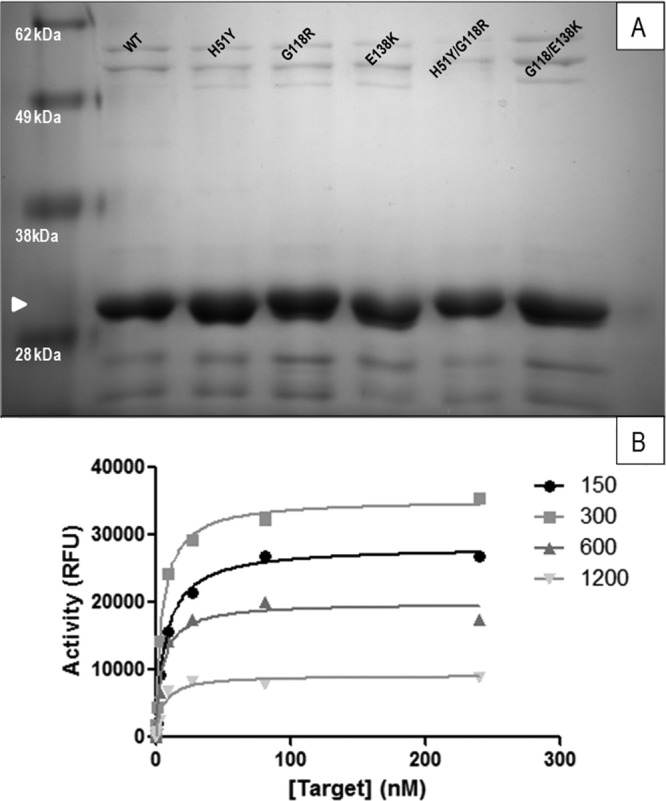

G118R reduces 3′ processing activity, and yet G118R/H51Y and G118R/E138K are fully active.

We showed above that the G118R substitution caused no difference in the ability of mutant enzyme to bind viral LTR DNA and that G118R/H51Y and G118R/E138K increased binding specificity and total DNA binding relative to the WT, respectively (Fig. 3B). We thus wanted to see the effect of these differences in LTR binding on the 3′ processing reaction. Using a previously reported and validated assay (35), we observed no significant differences between the 3′ processing activities of WT and G118R integrase proteins, while both the G118R/H51Y and G118R/E138K mutants had significantly higher 3′ processing activity than the WT (Fig. 4A and B). This led to significantly higher enzyme performance levels for the two double mutants relative to both the WT and G118R enzymes (Fig. 4C). The enzyme with the G118R substitution, despite having a Vmax similar to that of the WT enzyme, showed a 40% increase in its Km (Table 2); this, however, does not represent a major reduction in enzyme activity and would not account for the drastic reduction in viral integration and replication ability previously reported (26).

Fig 4.

Measurements of the 3′ processing activities of integrase. (A and B) The 3′ processing activities of the various integrase proteins were determined using a fixed enzyme concentration and various concentrations of immobilized LTR DNA. The raw TRF data for 3′ processing were calculated as described in Materials and Methods, and data were fitted in GraphPad Prism to Michaelis-Menten kinetics to obtain values of Vmax (A) and Km (B). (C) Enzyme performance was determined by division of Vmax by Km. Data represent the means of the results of at least 4 independent experiments each performed in duplicate (n ≥ 8). Error bars represent the standard errors of the means (SEM). Statistical significance was calculated for individual pairs of data using a one-sample two-tailed test with a statistical cutoff of P ≤ 0.05. N.S. = not significant.

H51Y and E138K partially rescue G118R activity by enhancing LTR DNA binding.

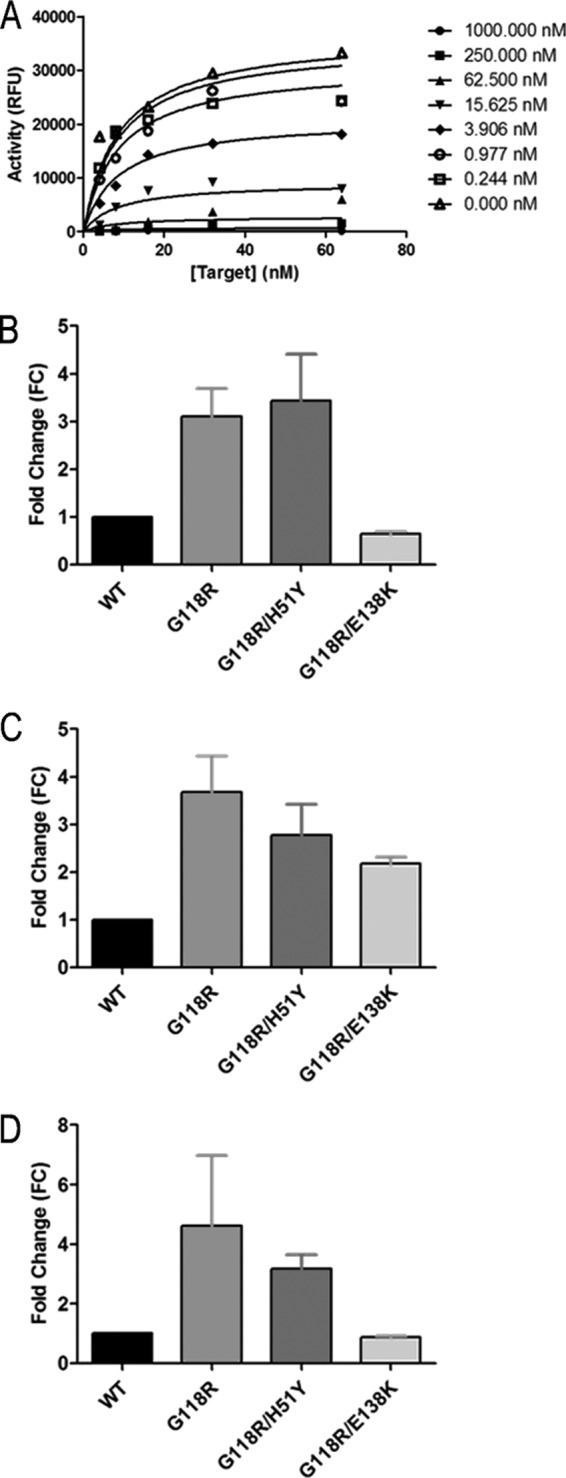

The LTR DNA binding assay indicated that a loss in enzyme performance may be partially attributable to deficits in target binding to the integrase-LTR DNA complexes. Integration requires two substrates, i.e., viral LTR DNA and target DNA. In addition, LTR binding and 3′ processing take place in the cytoplasm whereas strand transfer occurs in the nucleus; thus, the addition of DNA substrates to integrase is essentially a sequential ordered bisubstrate reaction (36), with the LTR binding first. In order to obtain a more accurate measure of the strand transfer reaction in an ordered sequential-addition bisubstrate reaction model, we varied the concentrations of both LTR DNA (0 to 160 nm) and target DNA (0 to 128 nM) in the presence of a fixed enzyme concentration (Fig. 5). Integrase strand transfer Vmax values calculated by this approach did not differ significantly between proteins (Table 1), and both the G118R/H51Y and G118R/E138K enzymes possessed target affinity (Kb) similar to that seen with the WT integrase (Fig. 5E), with enzyme performance levels for G118R/H51Y and G118R/E138K being 22% and 44% of the WT level, respectively. However, the G118R variant showed target DNA affinity similar to that seen in our initial assays (Fig. 2), with enzyme performance levels being 91% below that of WT enzyme (Fig. 5F and Table 1). Thus, the G118R substitution appears to reduce integration by affecting target DNA binding, and the addition of either H51Y or E138K increases strand transfer efficiency by enhancing LTR binding to integrase.

Fig 5.

Measurements of the strand transfer activities of integrase with bisubstrate variation. (A to D) Strand transfer activities of the various integrase proteins were determined by using a fixed enzyme concentration and various concentrations of LTR DNA and target DNA. The raw TRF data were fitted in GraphPad Prism to an ordered sequential-addition kinetic mechanism for WT (A), G118R (B), G118R/H51Y (C), and G118R/E138K (D) integrase proteins. (E) The affinity of target DNA for enzyme was assessed by the calculated Kb values. (F) Enzyme performance was determined by division of Vmax by the Km. Data represent the means of the results of 3 independent experiments (n = 3). Error bars represent the standard errors of the means (SEM). Statistical significance was calculated for individual pairs of data using a one-sample two-tailed test with a statistical cutoff of P ≤ 0.05. N.S. = not significant.

The H51Y and E138K double mutants do not show increased resistance to DTG, RAL, and EVG.

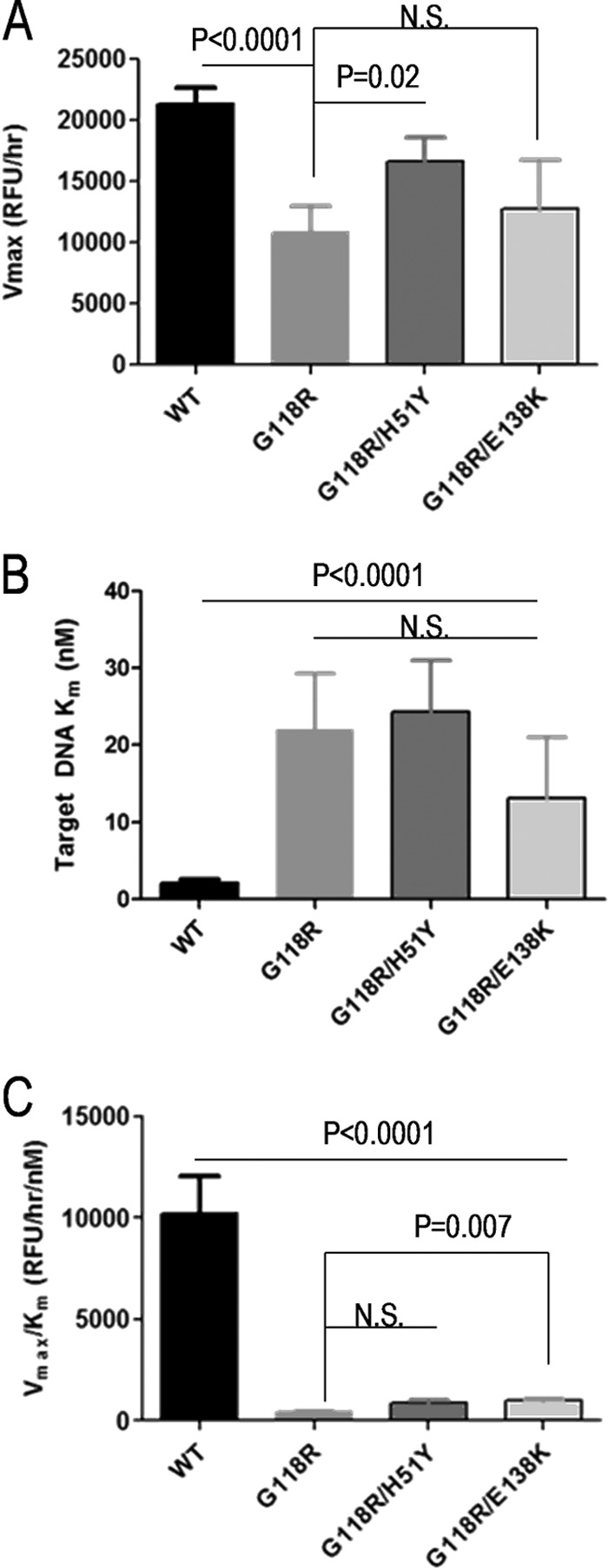

Primary drug resistance substitutions tend to cause deficits in enzyme activity, and the presence of secondary substitutions usually restores fitness and increases the level of resistance to a particular inhibitor (14). We have shown above that the performance loss caused by the G118R substitution in integrase can be partially rescued by either the H51Y or E138K secondary substitutions and therefore also wished to learn whether the addition of either of these substitutions to G118R would also affect levels of resistance to DTG, RAL, and EVG. Numerous reports have confirmed that INSTIs act by direct competition with target DNA and can also coordinate with divalent cations that are bound at the active site of integrase (5, 33, 49, 50). Next, we performed target saturation assays in the presence of various concentrations of RAL, EVG, or DTG (0 to 5 μM) (Fig. 6A). The data were fitted by nonlinear regression analysis to a competitive inhibition algorithm using GraphPad Prism to yield an inhibitory constant (Ki) for each drug-enzyme combination (Table 3). Unlike 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) measurements, which can vary if substrate concentrations are not sufficiently saturating, the Ki is an intrinsic property of each enzyme-inhibitor complex and is independent of the substrate concentration (36). Ki fold change (FC) results were obtained by dividing the Kis of the individual variants by that of the WT enzyme (Fig. 6B to D). The presence of G118R caused a 3.1-fold change in resistance to DTG. The addition of H51Y to G118R did not have a significant effect on resistance to DTG (Fig. 6B). As previously reported (26), G118R conferred low-level resistance to both RAL (Fig. 6C) and EVG (Fig. 6D). In both cases, the addition of either H51Y or E138K to G118R caused reductions in the level of resistance to RAL and EVG (Fig. 6C and D).

Fig 6.

Competitive inhibition of strand transfer by DTG, RAL, and EVG. Strand transfer reactions were carried out in the presence of 300 nM integrase. Transfer of target DNA was competitively inhibited with each of DTG, RAL, and EVG. Raw data from three independent experiments were fit to the competitive inhibition equation using GraphPad Prism. (A) A representative plot for the competitive inhibition of WT integrase DTG is shown. (B, C, and D) The fold change in susceptibility of each variant to DTG (B), RAL (C), and EVG (D) was calculated by division of the Ki for each variant by that for WT integrase. Data represent the means of the results of at least 3 independent experiments (n ≥ 3). Error bars represent the standard errors of the means (SEM).

Table 3.

Susceptibilities of purified integrase proteins to DTG, RAL, and EVGa

| Subtype B integrase protein |

Ki ± SEM (nM) |

∼FC |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAL | EVG | DTG | RAL | EVG | DTG | |

| WT | 1.83 ± 0.44 | 2.22 ± 0.92 | 1.25 ± 0.13 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| G118R | 6.29 ± 2.66 | 10.2 ± 2.46 | 3.94 ± 0.60 | 3.4 | 4.6 | 3.1 |

| G118R/H51Y | 5.16 ± 1.30 | 7.08 ± 0.69 | 4.26 ± 0.50 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 3.4 |

| G118R/E138K | 4.12 ± 0.34 | 1.95 ± 0.19 | 0.78 ± 0.26 | 2.3 | 0.88 | 0.64 |

All data represent the results of at least 3 independent experiments.

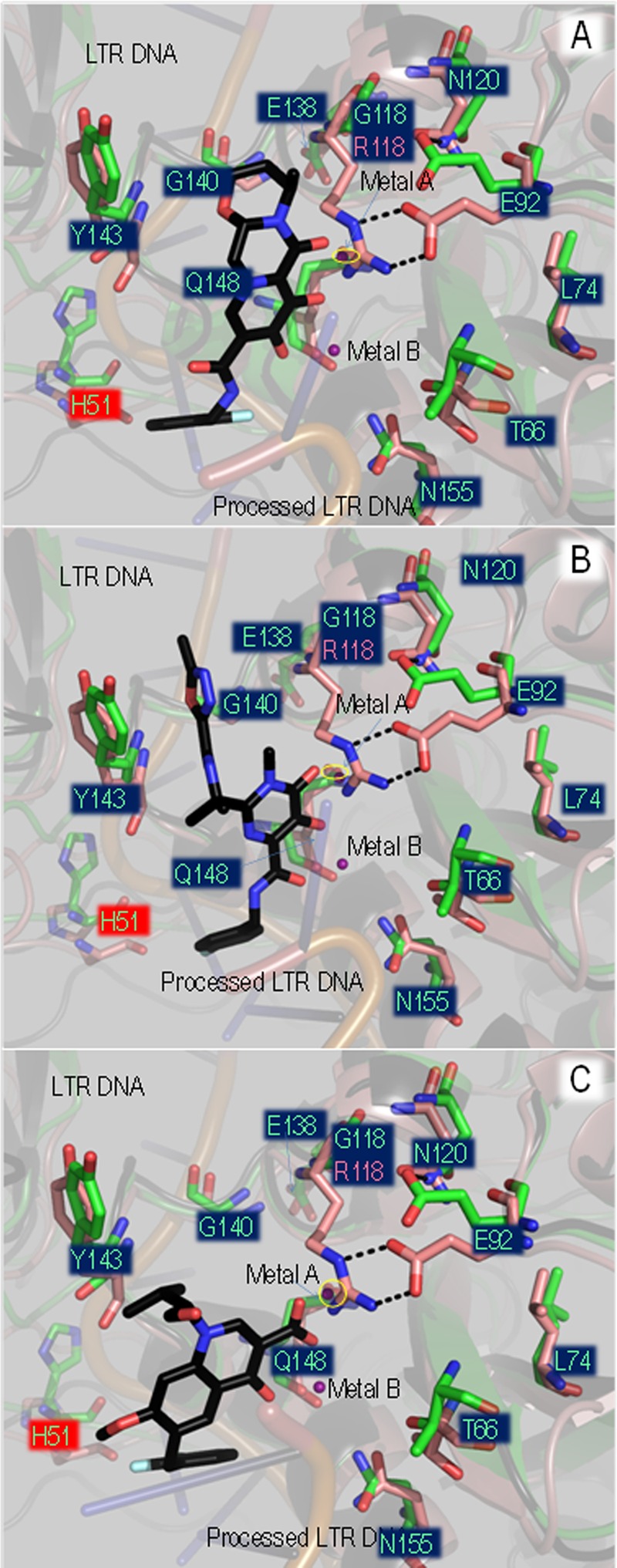

Structural analysis of the impact of G118R, E138K, and H51Y on the integrase active site.

Homology models of the integrase active site for the WT, G118R, G118R/H51Y, and G118R/E138K enzymes (Fig. 7 and 8) were created using the I-TASSER server (38, 51) with the recently published structures of PFV integrase as lead modeling templates (31). Rotamer analysis of WT active-site residues showed a propensity for the D64, D116, and E152 sites to co-orient in a manner similar to that described for the amino acid pairs in the PFV structure (Fig. 7A); in these orientations, the DDE motif of the WT HIV-1 integrase had good coordination interactions with the two Mn2+ ions derived from the PFV structure (Fig. 7A and C). When the WT model was overlaid with the latest PFV TCC (42), residue G118 was within 4 Å of the target DNA, and it is a logical assumption that any bulky substitution at this position would interfere with target DNA binding. This complements our data shown above in regard to a deficit in target DNA binding caused by the G118R substitution.

Fig 7.

Modeling of the HIV integrase active site. Energetically minimized homology models with sequences corresponding to the WT, G118R, G118R/H51Y, or G118R/E138K HIV-1 integrase were created based on the PFV strand transfer structure (PDB ID 3YO9). (A) Rotamer interrogation in the WT model showed that catalytic residues had a propensity to coordinate two divalent Mn2+ cations similar to that seen with the PFV integrase. (B) The positions of the mutated residues, G118R, H51Y, and E138K, relative to the corresponding residues in PFV integrase and to target and LTR DNA were obtained by direct superimposition of all the homology models with the PFV TCC. (C to E) Coordination of Mn2+ by the integrase active sites was simulated by insertion of the Mn2+ coordinates from the PDB structure 3YO9 into the active sites of modeled WT (C), G118R (D), and G118R/E138K (E) HIV-1 integrase enzymes. (F and G) Differences in orientations of catalytic residues in the presence or absence of G118R were investigated by superimposition of the WT and G118R homology models (F) and of G118R/E138K (G). All images were processed in PyMOL. Secondary structures are represented by partially transparent cartoon structures, with key residues shown in stick form. Cartoon and carbon atom coloration differentiates the WT (light green), G118R (salmon), and G118R/E138K (magenta). Mn2+ cations are shown as small purple spheres, with acidic (red) and basic (blue) moieties identified by standard atomic coloration.

Fig 8.

The G118R mutation in the context of INSTI drug resistance. Coordinates of DTG (A), RAL (B), and EVG (C) structures were inserted into the active site of the WT HIV-1 integrase homology model by overlap of the PFV integrase cocrystal structures, i.e., PDB ID 2S3M, PDB ID 3OYA, and PDB ID 3L2U, respectively. WT and G118R homology models were superimposed, with the side chains of most major integrase drug resistance mutations within 12 Å of the side chain of 118R being shown as stick representations. PyMOL was used for all image processing. All residues shown, with the exception of H51Y (red highlight), are within a 10-Å-diameter sphere of the active site. INSTI molecules are shown as sticks, with carbon molecules colored black and all other residues colored by standard atomic coloration. Coloration of WT and G118R models is as described for Fig. 7. A yellow oval marks the presence of metal A.

In an effort to gain insight into the mechanism of resistance caused by G118R, we superimposed the WT and G118R homology models with cocrystal PFV structures containing DTG, RAL, or EVG (Fig. 8) and examined interactions of G118 and 118R with the various inhibitors as well as with other residues implicated in INSTI resistance (11, 52, 53). The G118R substitution may cause 118R to form a salt bridge with E92, effectively breaking an electrostatic interaction of E92 with N120. E92 is implicated in EVG resistance. Additionally, all residues implicated in high-level RAL and EVG resistance (11, 14, 52, 53) were within 8 Å of position 118; in particular, T66 and L74 were within 4 Å of the guanidino group of 118R. L74M was an accessory substitution to G118R in the only clinically reported instance of this substitution (27) (Fig. 8).

DISCUSSION

The HIV integrase G118R substitution was selected by two drugs, RAL (27) and DTG (29), in CRF02_A/G virus and by MK-2048 (27) and DTG (29) in subtype C viruses. Prior to these selections, G118A, G118C, and G118R had been selected by a preclinical inhibitor S-1360 in a non-B context (28). G118R in subtype B was shown to display resistance to MK-2048 (26) and DTG (41). The current work focused on the enzymatic cost of the G118R substitution in a subtype B background as well as on the effects of the secondary H51Y and E138K substitutions on enzyme activity and level of drug resistance.

We have shown in this report that the G118R substitution results in a loss in both 3′ processing (Fig. 4 and Table 2) and strand transfer activity (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Our findings further indicate that the major block to integration ability caused by this substitution occurs at the level of strand transfer. There was no serious deficit in 3′ processing ability caused by the G118R substitution (Fig. 4), and the ability of the secondary substitutions H51Y and E138K to compensate G118R to higher-than-WT 3′ processing levels did not correlate with their inability to restore total integration activity (26) (unpublished data). The G118R substitution resulted in a >90% reduction in strand transfer efficiency (Fig. 3C and 5F and Table 1). The secondary substitutions H51Y and E138K partially repaired this deficit (Fig. 5E) but by different mechanisms: H51Y increased the specificity of LTR binding (Fig. 3B) whereas E138K increased the total overall DNA binding ability. Both of these secondary substitutions increased the number of integrase-LTR complexes; this resulted in increased overall enzyme performance, thereby implying that the deficit was partially due to the ability of the LTR-integrase complex to bind to target DNA (Fig. 5F). Although the G118R/H51Y and G118R/E138K enzymes had increased enzyme strand transfer performance relative to the G118R variant, this was still <50% of the WT enzyme performance (Fig. 5F). Additionally, an increase in the number of integrase-LTR complexes did not completely rescue the deficit in enzyme performance exhibited by the G118R variant. Thus, factors other than target DNA might be involved in the G118R-mediated reduction in enzyme performance. There was no major defect in the ability of the various integrase proteins to multimerize and to form the strand transfer complexes with the LTR and target DNA molecules (data not shown), as this would have changed the protein concentration at which integration was optimal (300 nM).

Homology modeling based on the PFV crystal structure provided some insight into the effects of the various substitutions described here on the active-site residues of HIV subtype B integrase (Fig. 7 and 8). The formation of a salt bridge between 118R and D64 represents the most energetically favorable backbone-dependent rotamer for 118R (Fig. 7A). The formation of this salt bridge causes a distortion in the orientation of D64 relative to the other two catalytic residues, and this could conceivably affect the ability of the G118R variant to coordinate the cofactor Mg2+/Mn2+ ions. This could also be related to the ability of the variant to bind to target DNA. It has been suggested that only one cation initially binds the enzyme and that the binding of the second cation is facilitated by DNA binding (34, 50, 54–56). This can also be inferred from the difficulty of obtaining integrase crystal structures with two bound Mg2+ ions (31, 41, 54, 55, 57). In the initial PFV crystal structures, the only structures that cocrystallized with Mn2+ had two ions bound at the active site whereas those formed with Mg2+ had only one ion bound despite evidence of effective 3′ processing activity (31). It has previously been reported that LTR binding to integrase is independent of cation binding (34, 42, 55), which may explain why there were no appreciable defects in the ability of the variant proteins to bind LTR DNA, with the exception of the G118R/H51Y double variant (Fig. 3). Additionally, it had been postulated that the roles of the two ions differ during the two integration steps (58), and this has recently been experimentally demonstrated (42). A single cation of Mn2+ (metal B) primes a water molecule for nucleophilic attack on the cytidine-guanine phosphodiester bond, facilitating 3′ processing. It subsequently keeps the reactive 3′OH end stabilized and primed for strand transfer. The other Mn2+ cation (metal A) (Fig. 8) polarizes and destabilizes the scissile phosphodiesterbond in the target DNA, permitting a nucleophilic attack on the target DNA by the reactive 3′OH of the viral DNA. The G118R enzyme and doubly mutated variants may have been impaired in their ability to bind metal A. Alternatively, the coordination sphere may have been altered toward D116 and E152 (Fig. 7E [indicated by arrow]). The addition of E138K to G118R resulted in an altered orientation for D116, bringing it closer to D64 relative to the WT enzyme (Fig. 7G) and G118R (Fig. 7F), and this may account for the partial rescue in activity and target DNA affinity that we observed in our experiments. Additionally, the G118R/E138K active site appeared to be slightly more acidic than that of WT enzyme (Fig. 8) and this may have increased the ability of the G118R/E138K integrase enzyme to coordinate Mg2+/Mn2+ ions and target DNA.

The E138K substitution was observed at the integrase, RAL, and -LTR interface; the change of an E to a K may have increased the nonspecific DNA binding abilities of integrase, leading to a concomitant increase in affinity for the target DNA relative to the G118R single variant (Fig. 5E). However, the addition of E138K to G118R did not abrogate the salt bridge between 118R and D64 and this may thus account for the fact that the G118R/E138K enzyme was seriously compromised in enzyme performance (Fig. 3C and 5F). In contrast, the G118R and H51Y substitutions did not appear to interact in the doubly mutated enzyme. This is in contradiction to interactions between H51Y and R263K (30) in the H51Y/R263K double mutant. The effect of H51Y on G118R may be due to the likelihood that each of G118R and H51Y has a separate effect on the enzyme. We previously reported that H51Y enzyme was less able to bind to the viral LTR (30), a finding consistent with the reduction in total LTR binding seen with the G118R/H51Y double mutant and the inability of H51Y to rescue enzyme performance.

The G118R substitution caused low-level resistance to DTG (3.1-fold), and the addition of H51Y to G118R did not significantly increase the level of resistance (3.4-fold) (Table 3). Superimposition of the HIV integrase models with PFV integrase bound to DTG (Fig. 8A), RAL (Fig. 8B), and EVG into the homology models (Fig. 8C) showed that the activity of these INSTIs would be compromised by the G118R substitution. It had been previously reported that the G118R substitution may result in steric hindrance to DTG binding (41). Our homology model of G118R provides additional possibilities for the mechanism(s) of resistance to DTG and other INSTIs. The side chain of 118R, in addition to forming a salt bridge with D64, forms a strong salt bridge with E92 and is within 4 Å of T66 and N155 (Fig. 8); each of these three residues has previously been implicated in resistance to both EVG and RAL (8, 11–13, 52). The salt bridge between 118R and E92 may break the interaction between E92 and N120 (Fig. 8A). Additionally, the E92-118R salt bridge may abrogate the interaction between E92 and the coordination scaffold of EVG (Fig. 8C), potentially explaining the slightly higher resistance levels conferred by G118R to EVG (Fig. 6C) compared to the other INSTIs.

The addition of E138K in a background of G118R caused striking reductions in resistance to all drugs tested, and the G118R/E138K enzyme displayed slightly higher susceptibility to DTG than the WT enzyme (Table 3 and Fig. 6B), while the G118R substitution alone apparently conferred low-level resistance to both RAL (Fig. 6C) and EVG (Fig. 6D). The G118R/H51Y and G118R/E138K doubly mutated enzymes displayed less resistance to both EVG and RAL than the G118R integrase, while the G118R/E138K enzyme was hypersensitive to EVG. Both H51Y and E138K have been selected in the clinic and have been shown to play a role in clinical resistance to EVG and RAL (11, 12, 14, 30, 52, 53).

In summary, this report presents an analysis of biochemical and structural data that define the G118R substitution in the context of subtype B and its interactions with integrase substitutions at positions H51Y and E138K. Our findings show that multiple factors may preclude G118R from occurring spontaneously and extend to the ability of G118R-mutated enzyme to efficiently catalyze integration. Structural insights provided through PFV crystal structures and modeling alignments imply that combinations of G118R together with multiple other substitutions might result in an enzyme that most likely would be catalytically defective. Should G118R develop in patients receiving DTG therapy, we believe that the resultant virus would be extremely unfit and that the development of further substitutions such as E138K might render the virus hypersusceptible to EVG and other INSTIs. Ongoing work will quantify the effects of these same substitutions in non-B subtypes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by research grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Canadian Foundation for AIDS Research (CANFAR) to M.A.W. and by an unrestricted research grant from ViiV Healthcare Inc.

P.K.Q. is a recipient of a doctoral scholarship from CIHR and the Canadian Association for HIV Research (CAHR). T.M. is the recipient of the BMS/CTN CIHR HIV Trials Network Postdoctoral Fellowship.

We are grateful to Maureen Oliviera for the initial selection studies and useful discussions and to Olivia Varsaneux, David Abergel, Arielle Sabbah, and Marc Charabati for assistance. We are also grateful to Tamara Bar-Magen for critical review of the manuscript and helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 September 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Bushman FD, Fujiwara T, Craigie R. 1990. Retroviral DNA integration directed by HIV integration protein in vitro. Science 249:1555–1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pauza CD. 1990. Two bases are deleted from the termini of HIV-1 linear DNA during integrative recombination. Virology 179:886–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lewinski MK, Bisgrove D, Shinn P, Chen H, Hoffmann C, Hannenhalli S, Verdin E, Berry CC, Ecker JR, Bushman FD. 2005. Genome-wide analysis of chromosomal features repressing human immunodeficiency virus transcription. J. Virol. 79:6610–6619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kulkosky J, Skalka AM. 1990. HIV DNA integration: observations and interferences. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 3:839–851 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hazuda DJ, Felock P, Witmer M, Wolfe A, Stillmock K, Grobler JA, Espeseth A, Gabryelski L, Schleif W, Blau C, Miller MD. 2000. Inhibitors of strand transfer that prevent integration and inhibit HIV-1 replication in cells. Science 287:646–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. FDA 12 October 2007, posting date FDA approval of Isentress (raltegravir). FDA, Silver Spring, MD [Google Scholar]

- 7. Temesgen Z. 2012. Cobicistat-boosted elvitegravir-based fixed-dose combination antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection. Drugs Today (Barc) 48:765–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Quashie PK, Sloan RD, Wainberg MA. 2012. Novel therapeutic strategies targeting HIV integrase. BMC Med. 10:34. 10.1186/1741-7015-10-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hazuda DJ. 2010. Resistance to inhibitors of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integration. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 14:513–518 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. 1989 Oral candidosis in HIV infection. Lancet ii:1491–1492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mesplède T, Quashie PK, Wainberg MA. 2012. Resistance to HIV integrase inhibitors. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 7:401–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blanco JL, Varghese V, Rhee SY, Gatell JM, Shafer RW. 2011. HIV-1 integrase inhibitor resistance and its clinical implications. J. Infect. Dis. 203:1204–1214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van Wesenbeeck L, Rondelez E, Feyaerts M, Verheyen A, Van der Borght K, Smits V, Cleybergh C, De Wolf H, Van Baelen K, Stuyver LJ. 2011. Cross-resistance profile determination of two second-generation HIV-1 integrase inhibitors using a panel of recombinant viruses derived from raltegravir-treated clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:321–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Quashie PK, Mesplede T, Wainberg MA. 2013. Evolution of HIV integrase resistance mutations. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 26:43–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kobayashi M, Yoshinaga T, Seki T, Wakasa-Morimoto C, Brown KW, Ferris R, Foster SA, Hazen RJ, Miki S, Suyama-Kagitani A, Kawauchi-Miki S, Taishi T, Kawasuji T, Johns BA, Underwood MR, Garvey EP, Sato A, Fujiwara T. 2011. In Vitro antiretroviral properties of S/GSK1349572, a next-generation HIV integrase inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:813–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. O'Neal R. 2011. Dolutegravir: a new integrase inhibitor in development. BETA 23:10–12 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Johnson BC, Métifiot M, Pommier Y, Hughes SH. 2012. Molecular dynamics approaches estimate the binding energy of HIV-1 integrase inhibitors and correlate with in vitro activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:411–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dooley KE, Sayre P, Borland J, Purdy E, Chen S, Song I, Peppercorn A, Everts S, Piscitelli S, Flexner C. 2013. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of the HIV integrase inhibitor dolutegravir given twice daily with rifampin or once daily with rifabutin: results of a phase 1 study among healthy subjects. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 62:21–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fantauzzi A, Turriziani O, Mezzaroma I. 2013. Potential benefit of dolutegravir once daily: efficacy and safety. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 5:29–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Waters LJ, Barber TJ. 2013. Dolutegravir for treatment of HIV: SPRING forwards? Lancet 381:705–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Raffi F, Rachlis A, Stellbrink HJ, Hardy WD, Torti C, Orkin C, Bloch M, Podzamczer D, Pokrovsky V, Pulido F, Almond S, Margolis D, Brennan C, Min S. 2013. Once-daily dolutegravir versus raltegravir in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 infection: 48 week results from the randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority SPRING-2 study. Lancet 381:735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eron JJ, Clotet B, Durant J, Katlama C, Kumar P, Lazzarin A, Poizot-Martin I, Richmond G, Soriano V, Ait-Khaled M, Fujiwara T, Huang J, Min S, Vavro C, Yeo J. 2013. Safety and efficacy of dolutegravir in treatment-experienced subjects with raltegravir-resistant HIV type 1 infection: 24-week results of the VIKING Study. J. Infect. Dis. 207:740–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wainberg MA, Quashie PK, Mesplede T. 2012. Dolutegravir HIV integrase inhibitor treatment of HIV infection. Drug Future 37:697–707. 10.1358/dof.2012.37.10.1855759 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hightower KE, Wang R, Deanda F, Johns BA, Weaver K, Shen Y, Tomberlin GH, Carter HL, Broderick T, Sigethy S, Seki T, Kobayashi M, Underwood MR. 2011. Dolutegravir (S/GSK1349572) exhibits significantly slower dissociation than raltegravir and elvitegravir from wild-type and integrase inhibitor-resistant HIV-1 integrase-DNA complexes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4552–4559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vavro C, Hasan S, Madsen H, Horton J, DeAnda F, Martin-Carpenter L, Sato A, Cuffe R, Chen S, Underwood M, Nichols G. 2013. Prevalent polymorphisms in wild-type HIV-1 integrase are unlikely to engender drug resistance to dolutegravir (S/GSK1349572). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:1379–1384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bar-Magen T, Sloan RD, Donahue DA, Kuhl BD, Zabeida A, Xu H, Oliveira M, Hazuda DJ, Wainberg MA. 2010. Identification of novel mutations responsible for resistance to MK-2048, a second-generation HIV-1 integrase inhibitor. J. Virol. 84:9210–9216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Malet I, Fourati S, Charpentier C, Morand-Joubert L, Armenia D, Wirden M, Sayon S, Van Houtte M, Ceccherini-Silberstein F, Brun-Vézinet F, Perno CF, Descamps D, Capt A, Calvez V, Marcelin AG. 19 September 2011. The HIV-1 integrase G118R mutation confers raltegravir resistance to the CRF02_AG HIV-1 subtype. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. [Epub ahead of print.] 10.1093/jac/dkr389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kobayashi M, Nakahara K, Seki T, Miki S, Kawauchi S, Suyama A, Wakasa-Morimoto C, Kodama M, Endoh T, Oosugi E, Matsushita Y, Murai H, Fujishita T, Yoshinaga T, Garvey E, Foster S, Underwood M, Johns B, Sato A, Fujiwara T. 2008. Selection of diverse and clinically relevant integrase inhibitor-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutants. Antiviral Res. 80:213–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Quashie PK, Mesplede T, Han YS, Oliveira M, Singhroy DN, Fujiwara T, Underwood MR, Wainberg MA. 2012. Characterization of the R263K mutation in HIV-1 integrase that confers low-level resistance to the second-generation integrase strand transfer inhibitor dolutegravir. J. Virol. 86:2696–2705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mesplède T, Quashie PK, Osman N, Han Y, Singhroy DN, Lie Y, Petropoulos CJ, Huang W, Wainberg MA. 2013. Viral fitness cost prevents HIV-1 from evading dolutegravir drug pressure. Retrovirology 10:22. 10.1186/1742-4690-10-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hare S, Gupta SS, Valkov E, Engelman A, Cherepanov P. 2010. Retroviral intasome assembly and inhibition of DNA strand transfer. Nature 464:232–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bar-Magen T, Donahue DA, McDonough EI, Kuhl BD, Faltenbacher VH, Xu H, Michaud V, Sloan RD, Wainberg MA. 2010. HIV-1 subtype B and C integrase enzymes exhibit differential patterns of resistance to integrase inhibitors in biochemical assays. AIDS 24:2171–2179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bar-Magen T, Sloan RD, Faltenbacher VH, Donahue DA, Kuhl BD, Oliveira M, Xu H, Wainberg MA. 2009. Comparative biochemical analysis of HIV-1 subtype B and C integrase enzymes. Retrovirology 6:103. 10.1186/1742-4690-6-103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Han YS, Xiao WL, Quashie PK, Mesplede T, Xu H, Deprez E, Delelis O, Pu JX, Sun HD, Wainberg MA. 2013. Development of a fluorescence-based HIV-1 integrase DNA binding assay for identification of novel HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Antiviral Res. 98:441–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Han YS, Quashie P, Mesplede T, Xu H, Mekhssian K, Fenwick C, Wainberg MA. 2012. A high-throughput assay for HIV-1 integrase 3′-processing activity using time-resolved fluorescence. J. Virol. Methods 184:34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cleland WW. 1989. The kinetics of enzyme-catalyzed reactions with two or more substrates or products. I. Nomenclature and rate equations. 1963. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1000:213–220 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cleland WW. 1967. Enzyme kinetics. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 36:77–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang Y. 2009. I-TASSER: fully automated protein structure prediction in CASP8. Proteins 77(Suppl 9):100–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bhuyan MS, Gao X. 2011. A protein-dependent side-chain rotamer library. BMC Bioinformatics 12(Suppl 14):S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bower MJ, Cohen FE, Dunbrack RL., Jr 1997. Prediction of protein side-chain rotamers from a backbone-dependent rotamer library: a new homology modeling tool. J. Mol. Biol. 267:1268–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hare S, Smith SJ, Métifiot M, Jaxa-Chamiec A, Pommier Y, Hughes SH, Cherepanov P. 2011. Structural and functional analyses of the second-generation integrase strand transfer inhibitor dolutegravir (S/GSK1349572). Mol. Pharmacol. 80:565–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hare S, Maertens GN, Cherepanov P. 2012. 3′-Processing and strand transfer catalysed by retroviral integrase in crystallo. EMBO J. 31:3020–3028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jenkins TM, Engelman A, Ghirlando R, Craigie R. 1996. A soluble active mutant of HIV-1 integrase: involvement of both the core and carboxyl-terminal domains in multimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 271:7712–7718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jenkins TM, Hickman AB, Dyda F, Ghirlando R, Davies DR, Craigie R. 1995. Catalytic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase: identification of a soluble mutant by systematic replacement of hydrophobic residues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:6057–6061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dyda F, Hickman AB, Jenkins TM, Engelman A, Craigie R, Davies DR. 1994. Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of HIV-1 integrase: similarity to other polynucleotidyl transferases. Science 266:1981–1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cleland WW. 1975. Partition analysis and the concept of net rate constants as tools in enzyme kinetics. Biochemistry 14:3220–3224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Smolov M, Gottikh M, Tashlitskii V, Korolev S, Demidyuk I, Brochon JC, Mouscadet JF, Deprez E. 2006. Kinetic study of the HIV-1 DNA 3′-end processing. FEBS J. 273:1137–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Deprez E, Barbe S, Kolaski M, Leh H, Zouhiri F, Auclair C, Brochon JC, Le Bret M, Mouscadet JF. 2004. Mechanism of HIV-1 integrase inhibition by styrylquinoline derivatives in vitro. Mol. Pharmacol. 65:85–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Goldgur Y, Craigie R, Cohen GH, Fujiwara T, Yoshinaga T, Fujishita T, Sugimoto H, Endo T, Murai H, Davies DR. 1999. Structure of the HIV-1 integrase catalytic domain complexed with an inhibitor: a platform for antiviral drug design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:13040–13043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Parrill AL. 2003. HIV-1 integrase inhibition: binding sites, structure activity relationships and future perspectives. Curr. Med. Chem. 10:1811–1824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Xu D, Zhang J, Roy A, Zhang Y. 2011. Automated protein structure modeling in CASP9 by I-TASSER pipeline combined with QUARK-based ab initio folding and FG-MD-based structure refinement. Proteins 79(Suppl 10):147–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Quashie PK, Mesplede T, Wainberg MA. 2013. HIV drug resistance and the advent of integrase inhibitors. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 15:85–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wainberg MA, Mesplede T, Quashie PK. 2012. The development of novel HIV integrase inhibitors and the problem of drug resistance. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2:656–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cherepanov P, Maertens GN, Hare S. 2011. Structural insights into the retroviral DNA integration apparatus. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 21:249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Li X, Krishnan L, Cherepanov P, Engelman A. 2011. Structural biology of retroviral DNA integration. Virology 411:194–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Marchand C, Zhang X, Pais GC, Cowansage K, Neamati N, Burke TR, Pommier Y. 2002. Structural determinants for HIV-1 integrase inhibition by beta-diketo acids. J. Biol. Chem. 277:12596–12603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hare S, Vos AM, Clayton RF, Thuring JW, Cummings MD, Cherepanov P. 2010. Molecular mechanisms of retroviral integrase inhibition and the evolution of viral resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:20057–20062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nowotny M, Gaidamakov SA, Crouch RJ, Yang W. 2005. Crystal structures of RNase H bound to an RNA/DNA hybrid: substrate specificity and metal-dependent catalysis. Cell 121:1005–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]