Abstract

The clonal distribution of Escherichia coli across an unselected population in the current era of widespread antimicrobial resistance is incompletely defined. In this study, we used a newly described clonal typing strategy based on sequencing of fumC and fimH (i.e., CH typing) to infer multilocus sequence types (STs) for 299 consecutive, nonduplicate extraintestinal E. coli isolates from all cultures submitted to Olmsted County, MN, laboratories in February and March 2011 and then compared STs with epidemiological data. Forty-seven different STs were identified, most commonly ST131 (27%), ST95 (11%), ST73 (8%), ST127 (6%), and ST69 (5%). Isolates from these five STs comprised two-thirds of health care-associated (HA) isolates but only half of community-associated (CA) isolates. ST131 was represented overwhelmingly (88%) by a single recently expanded H30 subclone, which was the most extensively antimicrobial-resistant subclone overall and was especially predominant in HA infections and among adults >50 years old. In contrast, among patients 11 to 50 years old, ST69, -95, and -73 were more common. Because of the preponderance of the H30 subclone of ST131, ST diversity was lower among HA than CA isolates, and among antimicrobial-resistant than antimicrobial-susceptible isolates, which otherwise had similar ST distributions. In conclusion, in this U.S. Midwest region, the distribution and diversity of STs among extraintestinal E. coli clinical isolates vary by patient age, type of infection, and resistance phenotype. ST131 predominates among young children and the elderly, HA infections, and antimicrobial-resistant isolates, whereas other well-known pathogenic lineages are more common among adolescents and young adults, CA infections, and antimicrobial-susceptible isolates.

INTRODUCTION

Escherichia coli, the most common Gram-negative extraintestinal pathogen, is becoming increasingly resistant to antimicrobials, thereby posing a significant public health threat. Antimicrobial resistance in E. coli can change rapidly due to dissemination of specific clones, or sequence types (STs). For example, strains of serotype O15:K52:H1 (ST393, within clonal complex CC31) caused an outbreak of multidrug-resistant extraintestinal infections in South London in 1986-1987 (1); likewise, the spread of clonal group A (CGA, ST69) contributed to outbreaks of urinary tract infections caused by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX)-resistant E. coli in the United States in the 1990s (2, 3). More recently, there has been worldwide expansion of the O15:K52:H1 (4) and ST131 (5–11) clonal groups. ST131 is now highly prevalent among antimicrobial-resistant E. coli, comprising nearly 70% of U.S. isolates resistant to fluoroquinolones (FQs) or extended-spectrum cephalosporins (8). Almost exclusively, the FQ resistance of ST131 is due to its single recently expanded subclone that is named H30 according to a typing scheme based on the carriage of specific fimH alleles (12).

In Olmsted County, MN, ST131 is common among elderly patients and those with health care-associated (HA) infections (13). In contrast, the prevalence of other E. coli clonal groups and their associations with clinical and demographic characteristics are not known. Indeed, few molecular epidemiology studies have evaluated the clonal distribution of E. coli across an unselected population in the current era of widespread antimicrobial resistance. Numerous previous studies have focused on antimicrobial-resistant (8) or extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase (ESBL)-expressing E. coli isolates (10, 14, 15), leading to over- or underrepresentation of certain clonal groups. Others have included isolates only from young (3) or elderly (16) patients or from restricted specimen types (3, 17, 18). Although some recent studies did evaluate consecutively collected isolates, they did not ascertain clinical data and thus could not reliably differentiate community-associated (CA) and health care-associated infections (17, 19). Thus, important knowledge gaps remain.

We used an unselected, population-based sample of E. coli from a region within the upper U.S. Midwest to determine E. coli population structure, clonal distribution, and ST associations with clinical and demographic characteristics. For this, we utilized a newly described, rapid clonal typing strategy based on sequencing of fumC and fimH, i.e., CH typing (20).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimen collection.

We collected and analyzed all nonduplicate extraintestinal E. coli isolates from all specimen types submitted to two Olmsted County laboratories (serving Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center, the only health care centers in Olmsted County, MN) during February and March 2011. These two laboratories handle the specimens from all inpatients and outpatients in the county. We included only 1 isolate per individual, from patients who provided research authorization. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by the clinical microbiology laboratories (21). Results were interpreted using breakpoints recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (22). Isolates that were resistant or intermediate to a given antimicrobial were considered nonsusceptible. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) isolates were those resistant to ≥3 of the following drug classes: beta-lactams, fluoroquinolones, TMP-SMX, nitrofurantoin, and aminoglycosides (23). The Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center institutional review boards approved this study.

Clinical data abstraction.

We reviewed medical records to abstract demographic and clinical variables. HA isolates were defined as those collected from inpatients >72 h after hospitalization, or from outpatients who had been hospitalized within 90 days prior to culture collection, were residents of a nursing home or long-term care facility (LTCF), and/or within 30 days prior to culture collection had received home intravenous therapy, wound care, specialized nursing, urinary catheterization, dialysis, or chemotherapy. CA isolates were defined as those recovered from patients who lacked the above health care-associated risk factors and were either outpatients or inpatients hospitalized for <72 h. An infection was considered uncomplicated if (i) E. coli was cultured from urine and (ii) the patient was treated as an outpatient and was immunocompetent, without genitourinary abnormalities or evidence of upper urinary tract infection. An infection was considered complicated if (i) E. coli was cultured from any extraintestinal nonurine site (including blood, peritoneal fluid, intra-abdominal abscess fluid, bone, and bronchial washings) or (ii) the patient was immunocompromised or hospitalized, had significant genitourinary abnormalities other than neurogenic bladder, or had upper urinary tract infection.

Molecular characterization.

The major E. coli phylogenetic group (A, B1, B2, and D) was determined by triplex PCR (24). Three resistance-associated E. coli clonal groups—ST131, CGA, and O15:K52:H1—were identified by using PCR-based detection of clonal group-specific single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in housekeeping genes (5). All isolates were clonally typed using CH typing (20). Based on the so-identified fumC and fimH allele combinations (i.e., CH types), STs were inferred with reference to a large private database (V.T. and E.V.S.) containing CH types for diverse E. coli isolates that had undergone full 7-locus multilocus sequence typing (MLST; http://mlst.ucc.ie/mlst/dbs/Ecoli). This allowed CH types to be cross-referenced to specific STs and single-locus variants thereof, which were included under the main ST designations. Within ST131, we also discriminated the H30 subclone from non-H30 subclones. The few CH types that mapped to multiple STs were assigned to the numerically most-probable ST.

Statistical analysis.

Comparisons between groups were evaluated using Kruskal-Wallis, Wilcoxon rank sum, chi-square, and Fisher exact tests, as appropriate. All tests were two-sided. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Simpson's diversity index was used to analyze genotypic diversity of isolates (25, 26). Isolates that could not be assigned an ST were excluded from diversity analyses.

RESULTS

ST distribution.

Consecutive single-patient E. coli clinical isolates were characterized from all patients who provided research authorization (299 [90%] of 331 patients). Most of the 299 isolates were from urine (90%), outpatients (68%), and community-associated (CA) infections (61%) (Table 1). The median patient age was 58 years. Isolates overwhelmingly belonged to phylogenetic group B2 (71%), followed distantly by groups D (17%), A (6%), and B1 (6%). Forty-seven different STs were identified, the most common being ST131 (27%), ST95 (11%), ST73 (8%), ST127 (6%), and ST69 (5%). Within the ST131 clonal group, the H30 ST131 subclone accounted for 70 (88%) of 80 isolates. Only 20 isolates (6.6%), which contained novel fimH alleles, could not be assigned to an ST using the CH typing strategy. Clonal group-specific SNP PCR agreed precisely with CH typing for identifying ST131, CGA (ST69), and the O15:K52:H1 (ST393) clonal group.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic features according to ST among 299 Escherichia coli isolates

| Characteristic | No. of isolates (column %) |

P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 299) | ST131 (n = 80) | ST95 (n = 32) | ST73 (n = 25) | ST127 (n = 18) | ST69 (n = 15) | Othera (n = 129) | ||

| Age (yrs) | ||||||||

| ≤10 | 23 (8) | 5 (6) | 1 (3) | 1 (4) | 0 | 2 (20) | 13 (10) | <0.01 |

| 11–50 | 96 (32) | 10 (13) | 16 (50) | 12 (48) | 8 (44) | 6 (40) | 44 (34) | |

| >50 | 180 (60) | 65 (81) | 15 (47) | 12 (48) | 10 (56) | 6 (40) | 72 (56) | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 238 (80) | 63 (79) | 28 (88) | 19 (76) | 14 (78) | 13 (87) | 101 (78) | 0.84 |

| Male | 61 (20) | 17 (21) | 4 (13) | 6 (24) | 4 (22) | 2 (13) | 28 (22) | |

| Raceb | ||||||||

| White | 243 (91) | 62 (90) | 27 (93) | 23 (100) | 14 (88) | 12 (92) | 105 (91) | 0.68 |

| Nonwhite | 23 (9) | 7 (10) | 2 (7) | 0 | 2 (13) | 1 (8) | 11 (9) | |

| Acquisitionb | ||||||||

| CA | 180 (61) | 27 (34) | 21 (68) | 18 (72) | 14 (78) | 11 (73) | 89 (70) | <0.01 |

| HA | 117 (39) | 53 (66) | 10 (32) | 7 (28) | 4 (22) | 4 (27) | 39 (30) | |

| Source | ||||||||

| Urine | 268 (90) | 68 (85) | 28 (88) | 24 (96) | 17 (94) | 13 (87) | 118 (91) | 0.40 |

| Blood | 17 (6) | 5 (6) | 4 (13) | 1 (4) | 1 (6) | 1 (7) | 5 (4) | |

| Other | 14 (5) | 7 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (7) | 6 (5) | |

| Severityb | ||||||||

| Colonization | 34 (12) | 7 (9) | 4 (13) | 4 (17) | 3 (18) | 1 (7) | 15 (12) | 0.27 |

| Uncomplicated | 211 (72) | 52 (67) | 19 (61) | 19 (79) | 12 (71) | 11 (73) | 98 (77) | |

| Complicated | 48 (16) | 19 (24) | 8 (26) | 1 (4) | 2 (12) | 3 (20) | 15 (12) | |

| Residenceb | ||||||||

| Non-LTCF | 261 (88) | 52 (65) | 29 (94) | 24 (96) | 17 (94) | 15 (100) | 124 (96) | <0.01 |

| LTCF | 37 (12) | 28 (35) | 2 (6) | 1 (4) | 1 (6) | 0 | 5 (4) | |

Other isolates include ST58 (n = 12); ST141 (n = 11); ST10 (n = 10); ST38 (n = 9); ST144 (n = 7); ST372 and ST12 (n = 6 each); ST393 and ST14 (n = 4 each); ST101, ST1193, ST405, ST59, ST62, and ST80 (n = 2 each), and ST10160, ST1146, ST1148, ST117, ST130, ST1670, ST2260, ST2541, ST2556, ST28, ST297, ST349, ST354, ST420, ST448, ST491, ST54, ST625, ST646, ST648, ST681, ST701, ST83, ST929, ST973, and ST11089 (n = 1 each).

Isolates with missing data were excluded, leaving n = 266 for race, n = 297 for acquisition, n = 293 for severity, and n = 298 for residence.

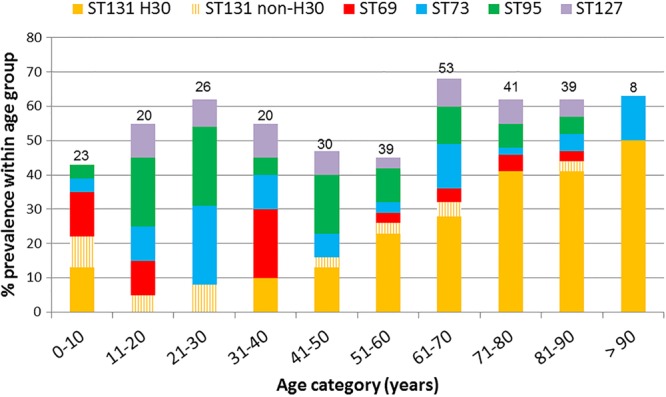

Although the 5 most common STs accounted collectively for a near majority of isolates within each age group, their distribution varied significantly with decade (P = 0.001) (Table 1). ST131, represented almost exclusively by its H30 subclone, was the most common ST among adults >50 years old and increased in prevalence with age, as previously described (13). In contrast, among children <10 years old, both H30 and non-H30 ST131 isolates were prevalent, and among subjects 11 to 30 years old, non-H30 ST131 isolates were more common than H30 ST131 isolates (Fig. 1). ST distribution did not vary by gender or between the two medical centers (not shown).

Fig 1.

Clonal distribution of extraintestinal Escherichia coli isolates according to patient age group. The five most prevalent STs overall are shown. The number above each bar is the number of patients within that age cohort.

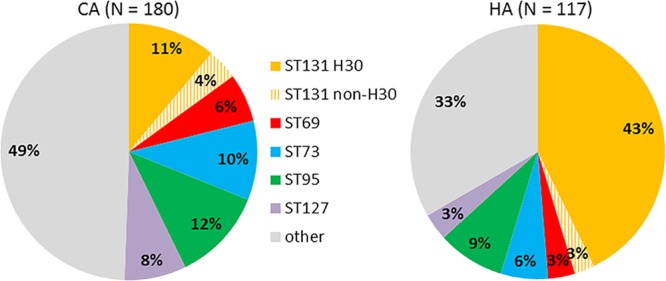

ST distribution also differed by site of infection acquisition, complicated versus uncomplicated infection, and specimen type (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Regarding site of acquisition, isolates from the 5 most common STs comprised two-thirds of HA isolates but only half of CA isolates (Fig. 2). This association was due to ST131, in particular its H30 subclone, since two-thirds of ST131 isolates were HA and one-third were CA, whereas for all other STs the majority of isolates were CA (P < 0.001) (Table 1). Additionally, ST131 comprised 76% of isolates from LTCF residents, a significantly higher proportion than other STs (0 to 14%; P < 0.001), which in contrast accounted for most isolates from patients who did not reside in LTCFs. ST95 and ST131 accounted jointly for a significantly higher proportion of complicated infections than did other STs (P = 0.003). The proportion of nonurine isolates was higher for ST131 (15%), ST69 (14%), and ST95 (13%) than for other STs (0 to 9% each).

Fig 2.

Distribution of Escherichia coli STs among patients with CA or HA extraintestinal E. coli isolates. Total ST131 prevalences (i.e., for H30 plus non-H30 ST131 subsets combined) were 15% in CA and 46% in HA isolates (P < 0.001).

ST distribution likewise varied by resistance phenotype (Table 2). ST131 was the most extensively antimicrobial-resistant ST, displaying high prevalence of resistance to fluoroquinolones (89%), any beta-lactam (84%), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) (46%), and multidrug resistance (51%). Within ST131, all 70 (100%) H30 subclone isolates were resistant to fluoroquinolones, compared with only 1 (10%) of the 10 non-H30 ST131 isolates (P < 0.001). Over half of isolates within ST95, ST73, and ST127 were fully antimicrobial susceptible. ST69 stood out from the other prevalent non-ST131 STs and more closely resembled ST131, with its high prevalence of resistance to beta-lactams (82%, versus 81% for ST131) and TMP-SMX (53%, versus 46% for ST131) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antimicrobial resistance according to ST among 299 extraintestinal Escherichia coli isolates

| Antimicrobial | No. of resistant isolates (column %) |

P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 299) | ST131a (n = 80) | ST95 (n = 32) | ST73 (n = 25) | ST127 (n = 18) | ST69 (n = 15) | Other (n = 129) | ||

| Fluoroquinolone | 88 (29) | 71 (89) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (7) | 16 (12) | <0.01 |

| Ampicillin | 156 (52) | 65 (81) | 13 (41) | 10 (40) | 4 (22) | 11 (73) | 53 (41) | <0.01 |

| Ceftriaxone (n = 259)b | 16 (6) | 8 (11) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 (7) | 0.28 |

| Gentamicin | 29 (10) | 23 (29) | 0 | 0 | 1 (6) | 0 | 5 (4) | <0.01 |

| TMP-SMX | 88 (29) | 37 (46) | 2 (6) | 3 (12) | 1 (6) | 8 (53) | 37 (29) | <0.01 |

| Cefazolin (n = 297)b | 93 (31) | 45 (57) | 3 (9) | 7 (28) | 3 (17) | 5 (33) | 30 (23) | <0.01 |

| Nitrofurantoin (n = 274)b | 8 (3) | 3 (4) | 1 (3) | 1 (4) | 0 | 0 | 3 (2) | 0.93 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 6 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | 2 (8) | 1 (6) | 0 | 2 (2) | 0.20 |

| Imipenem (n = 258)b | 3 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (14) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0.03 |

| FQ + TMP-SMX | 46 (15) | 33 (41) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (7) | 12 (9) | <0.01 |

| Any beta-lactamc (n = 256)b | 141 (55) | 59 (84) | 11 (42) | 8 (38) | 5 (36) | 9 (82) | 49 (43) | <0.01 |

| MDRd (n = 233)b | 42 (18) | 30 (51) | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) | 0 | 11 (10) | <0.01 |

| None of abovee (n = 233)a | 96 (41) | 1 (2) | 13 (52) | 13 (65) | 9 (69) | 1 (11) | 59 (55) | <0.01 |

Resistance prevalence among H30 (n = 70) versus non-H30 (n = 10) ST131 was as follows: FQ (100% versus 10%; P < 0.01), ampicillin (81% versus 80%; P = 1), ceftriaxone (9% versus 29%; P = 0.18), gentamicin (30% versus 20%; P = 0.72), TMP-SMX (47% versus 40%; P = 0.75), cefazolin (58% versus 50%; P = 0.74), nitrofurantoin (3% versus 13%; P = 0.32), piperacillin-tazobactam (1% versus 0%; P = 1), FQ + TMP-SMX (47% versus 0%; P < 0.01), any beta-lactam (86% versus 71%; P = 0.30), MDR (52% versus 40%; P = 0.67), none of above (0% versus 20%; P = 0.08).

Not all isolates were tested against all agents, accounting for the smaller sample size in some rows.

Beta-lactams: ampicillin, ceftriaxone, cefazolin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and imipenem.

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) isolates were those resistant to ≥3 of the following drug classes: beta-lactams, fluoroquinolones, TMP-SMX, nitrofurantoin, and aminoglycosides.

Resistant to none of the tested agents.

CH type diversity.

To quantify and compare genotypic diversity among isolate groups, we used Simpson's diversity index, with which higher numbers indicate lower diversity (Table 3). Diversity of STs did not differ by gender or specimen type. However, ST diversity was significantly lower among isolates from patients >50 years old than among those from patients 11 to 50 years old. When we excluded the H30 ST131 subclone, ST diversity increased most dramatically among patients >50 years old, becoming significantly higher than the diversity of entire data set (P < 0.001). This result is consistent with the predominance of the H30 ST131 subclone among patients >50 years old, as depicted in Fig. 1. Also, HA isolates were significantly less diverse than CA isolates. Similarly, isolates resistant to any given antimicrobial agent, or to combinations thereof, were significantly less diverse than isolates with the corresponding susceptible phenotype. The observed difference in clonal diversity was due primarily to the differential distribution of the H30 ST131 subclone. Accordingly, when H30 isolates were excluded from these analyses, the estimated diversity among HA and antimicrobial-resistant isolates increased to match that of the CA and susceptible isolates (Table 3).

Table 3.

Simpson diversity indices according to patient characteristics and resistance phenotypes, with and without the H30 ST131 subclonea

| Feature | Including all ST131 isolates |

Excluding H30 ST131 subclone isolates |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simpson index (SE) | P value | Simpson index (SE) | P value | |

| All | 0.12 (0.01) | 0.07 (0.01) | <0.01b | |

| Age (yrs) | ||||

| <10 | 0.12 (0.03) | 0.53c | 0.10 (0.02) | 1c |

| 11–50 | 0.10 (0.01) | 0.03d | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.07d |

| > 50 | 0.17 (0.03) | 0.18e | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.07e |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 0.12 (0.02) | 1 | 0.07 (0.01) | 1 |

| Male | 0.12 (0.03) | 0.07 (0.01) | ||

| Acquisition | ||||

| CA | 0.08 (0.01) | <0.01 | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.79 |

| HA | 0.25 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.01) | ||

| Source | ||||

| Urine | 0.11 (0.01) | 0.13 | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.31 |

| Nonurine | 0.21 (0.07) | 0.10 (0.03) | ||

| Fluoroquinolone | ||||

| Susceptible | 0.08 (0.01) | <0.01 | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.11 |

| Resistant | 0.69 (0.07) | 0.14 (0.04) | ||

| Ampicillin | ||||

| Susceptible | 0.08 (0.01) | <0.01 | 0.08 (0.01) | 1 |

| Sesistant | 0.22 (0.03) | 0.08 (0.01) | ||

| TMP-SMX | ||||

| Susceptible | 0.10 (0.01) | <0.01 | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.35 |

| Resistant | 0.23 (0.05) | 0.08 (0.01) | ||

| Cefazolin | ||||

| Susceptible | 0.09 (0.01) | <0.01 | 0.08 (0.01) | 1 |

| Resistant | 0.28 (0.05) | 0.08 (0.01) | ||

| Beta-lactamsf | ||||

| Susceptible | 0.07 (0.01) | <0.01 | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.13 |

| Resistant | 0.22 (0.03) | 0.07 (0.01) | ||

| MDRg | ||||

| No | 0.08 (0.01) | <0.01 | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.14 |

| Yes | 0.54 (0.10) | 0.11 (0.02) | ||

| Any resistance | ||||

| No | 0.08 (0.01) | <0.01 | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.91 |

| Yes | 0.23 (0.04) | 0.08 (0.01) | ||

Note that 20 isolates with unknown ST by CH typing were excluded.

Compares diversity among all isolates with and without ST131. All other P values compare diversity between subgroups of each variable within the category “all ST131” or “excluding H30 ST131.”

Compares diversity between <10 years and 11 to 50 years.

Compares diversity between 11 to 50 years and >50 years.

Compares diversity between <10 years and >50 years.

Beta-lactams: ampicillin, ceftriaxone, cefazolin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and imipenem.

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) isolates were those resistant to ≥3 of the following classes: fluoroquinolones, beta-lactams, TMP-SMX, gentamicin, and nitrofurantoin.

DISCUSSION

In this survey, we characterized the clonal distribution, clonal diversity, and associated clinical characteristics of extraintestinal E. coli isolates consecutively sampled in February and March 2011 in a region within the upper U.S. Midwest by using CH typing, a novel, rapid, and discriminatory strategy for clonal typing. We determined that different E. coli STs varied in prevalence by patient age, type of infection, and resistance phenotype. Specifically, the H30 ST131 subclone was especially common among very young children, older adults, HA infections, and antimicrobial-resistant isolates, whereas non-H30 ST131 and other well-known pathogenic lineages were common among older children, young adults, CA infections, and antimicrobial-susceptible isolates. Differences in antibiotic exposure, prevalence of comorbidities, exposure to long-term care facilities, and relative proportion of CA versus HA infections may contribute to ST distribution differences among various patient populations.

Five STs comprised well over half of the isolates in our collection, as in similar recent collections (17, 19). The most prevalent STs we identified correspond closely with those found in several other geographic regions (19, 20). However, in the San Francisco Bay area, ST12 but not ST127 was noted as a prevalent clonal group (17). This difference could be related to geographic variation or the fact that the San Francisco study evaluated only blood isolates (17), while our isolates were primarily from urine. Across all these studies, ST131 was the most common ST identified (16, 17, 19). Notably, our ST131 prevalence (27%) was higher than found in prior studies (the next highest being 23% [17]), likely due to geographic or host population differences and/or increasing ST131 prevalence over time.

We found that genotypic diversity was lower among antimicrobial-resistant isolates than among antimicrobial-susceptible isolates, as noted previously (3, 17), and among HA isolates than among CA isolates. Furthermore, we found that when the H30 subclone ST131 isolates were excluded, the diversity of HA and antimicrobial-resistant isolates increased substantially, to a level matching that of the CA and antimicrobial-susceptible isolates. This suggests that the clonal expansion (and consequent predominance) of the H30 ST131 subclone is responsible for the observed lower diversity of the HA and antimicrobial-resistant subgroups. These findings, together with earlier work by our group (13) and others (16, 27), support the idea that the H30 ST131 subclone is expanding within health care facilities, which emphasizes the need for more effective antimicrobial stewardship and infection prevention efforts in these settings. In contrast, the greater diversity observed among CA isolates suggests that expansion of specific clonal groups has not occurred to nearly the same extent in the community as in health care settings.

A study limitation is that we did not confirm CH typing results with MLST for each isolate. However, we did confirm the identity of 3 major clonal groups (ST131, CGA, and O15:K52:H1) through SNP-based PCR, and the CH typing method has been validated previously using several large isolate collections (20; V. Tchesnokova and E. V. Sokurenko, unpublished data). We also were unable to assign STs to 20 isolates containing novel fimH alleles. However, since each of these isolates had a unique combination of fumC and fimH alleles, they are quite unlikely to represent a prevalent clonal group. Additionally, the study spanned a 2-month period, which was not long enough to assess seasonal variation in circulating E. coli sequence types. Study strengths include the facts that we used unselected consecutive sampling and population-based clinical microbiology surveillance, resolved not just STs but the H30 subclone within ST131, and reviewed medical records to assess for complicated infection and to determine whether isolates caused community- versus health care-associated infection.

In conclusion, we found that in the study region within the upper U.S. Midwest, E. coli clonal group distribution and diversity varied by patient age, community- versus hospital-associated status, and resistance phenotype. We conclude that the resistance-associated H30 ST131 subclone, more than other clonal groups, has expanded in health care settings, likely in part due to widespread, often inappropriate antimicrobial use, inadequate infection control practices, and a high proportion of elderly patients who serve as reservoirs of this subset within ST131. In addition, we confirmed that CH typing is a rapid clonal typing method, feasible for evaluating large numbers of isolates. Since CH typing is based on sequencing of two loci, it is faster and cheaper than standard MLST and is likely to become a widely used strategy in future studies of E. coli molecular epidemiology and clonal group surveillance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mary Ann Butler and Jacalyn Koranda, Olmsted Medical Center, and Lisa Nyre, Jim Uhl, and Robin Patel, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, for assistance with isolate collection, processing, and storage.

J.R.J. has received grants, contracts, or consultancies from ICET, Merck, Rochester Medical, and Syntiron. J.R.J. and E.V.S. have patent applications related to diagnostic tests for E. coli clonal groups.

This material is based upon work supported by Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, grant 1 I01 CX000192 01 (J.R.J.), and NIH grants RC4-AI092828 (E.V.S. and J.R.J.) and 2KL2RR024151-07 (R.B.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 September 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. O'Neill O, Talboys C, Roberts A, Azadian B. 1990. The rise and fall of Escherichia coli O15 in a London teaching hospital. J. Med. Microbiol. 33:23–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johnson J, Manges A, O'Bryan T, Riley L. 2002. A disseminated multidrug-resistant clonal group of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in pyelonephritis. Lancet 359:2249–2251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Manges A, Johnson J, Foxman B, O'Bryan T, Fullerton K, Riley L. 2001. Widespread distribution of urinary tract infections caused by a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli clonal group. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:1007–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Olesen B, Scheutz F, Menard M, Skov M, Kolmos H, Kuskowski M, Johnson J. 2009. Three-decade epidemiological analysis of Escherichia coli O15:K52:H1. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1857–1862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johnson J, Menard M, Johnston B, Kuskowski M, Nichol K, Zhanel G. 2009. Epidemic clonal groups of Escherichia coli as a cause of antimicrobial-resistant urinary tract infections in Canada, 2002–2004. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2733–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coque T, Baquero F, Canton R. 2008. Increasing prevalence of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Euro Surveill. 13:1–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Platell J, Cobbold R, Johnson J, Trott D. 2010. Clonal group distribution of fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli among humans and companion animals in Australia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1936–1938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnson J, Johnston B, Clabots C, Kuskowski M, Castanheira M. 2010. Escherichia coli sequence type ST131 as the major cause of serious multidrug-resistant E. coli infections in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 51:286–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cagnacci S, Gualco L, Debbia E, Schito G, Marchese A. 2008. European emergence of ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli clonal groups O25:H4-ST131 and O15:K52:H1 causing community-acquired uncomplicated cystitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2605–2612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nicolas-Chanoine M-H, Blanco J, Leflon-Guibout V, Demarty R, Alonso M, Canica MM, Park Y-J, Lavigne J-P, Pitout J, Johnson J. 2008. Intercontinental emergence of Escherichia coli clone O25:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:273–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peirano G, Costello M, Pitout J. 2010. Molecular characteristics of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli from the Chicago area: high prevalence of ST131 producing CTX-M-15 in community hospitals. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 36:19–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johnson J, Tchesnokova V, Johnston B, Clabots C, Roberts P, Billig M, Riddell K, Rogers P, Qin X, Butler-Wu S, Price L, Aziz M, Nicolas-Chanoine M, Debroy C, Robicsek A, Hansen G, Urban C, Platell J, Trott D, Zhanel G, Weissman S, Cookson B, Fang F, Limaye A, Scholes D, Chattopadhyay S, Hooper D, Sokurenko E. 2013. Abrupt emergence of a single dominant multidrug-resistant strain of Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 207:919–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Banerjee R, Johnston B, Lohse C, Porter S, Clabots C, Johnson J. 2013. Escherichia coli sequence type ST131 is a dominant, antimicrobial-resistant clonal group associated with healthcare and elderly hosts. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 34:361–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson J, Urban C, Weissman S, Jorgensen J, II JL, Hansen G, Edelstein P, Robicsek A, Cleary T, Adachi J, Paterson D, Quinn J, Hanson N, Johnston B, Clabots C, Kuskowski M. 2012. Molecular epidemiological analysis of Escherichia coli sequence type ST131 (O25:H4) and blaCTX-M-15 among extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing E. coli from the United States, 2000–2009. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:2364–2370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blanco M, Alonso MP, Nicolas-Chanoine M-H, Dhabi G, Mora A, Blanco JE, Lopez C, Cortex P, Llagostera M, Leflon-Guibout V, Puentes B, Mamani R, Herrera A, Coira MA, Garcia-Garrote F, Pita JM, Blanco J. 2009. Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli producing extended-spectrum beta lactamases in Lugo (Spain): dissemination of clone O25b:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63:1135–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Croxall G, Hale J, Weston V, Manning G, Cheetham P, Achtman M, McNally A. 2011. Molecular epidemiology of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates from a regional cohort of elderly patients highlights the prevalence of ST131 strains with increased antimicrobial resistance in both community and hospital care settings. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:2501–2508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Adams-Sapper S, Diep B, Perdreau-Remington F, Riley L. 2013. Clonal composition and community clustering of drug-susceptible and -resistant Escherichia coli isolates from bloodstream infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:490–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Manges A, Tabor H, Tellis P, Vincent C, Tellier P-P. 2008. Endemic and epidemic lineages of Escherichia coli that cause urinary tract infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:1575–1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gibreel T, Dodgson A, Cheesbrough J, Fox A, Bolton F, Upton M. 2012. Population structure, virulence potential and antibiotic susceptibility of uropathogenic Escherichia coli from Northwest England. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:346–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weissman S, Johnson J, Tchesnokova V, Billig M, Dykhuizen D, Riddell K, Rogers P, Qin X, Butler-Wu S, Cookson B, Fang F, Scholes D, Chattopadhyay S, Sokurenko E. 2012. High resolution two-locus clonal typing of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:1353–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2009. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; nineteeth informational supplement (M100-S19). Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 22. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2010. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twentieth informational supplement, CLSI document M100-S20. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sahm D, Thornsberry C, Mayfield D, Jones M, Karlowsky J. 2001. Multidrug-resistant urinary tract isolates of Escherichia coli: prevalence and patient demographics in the United States in 2000. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:402–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Clermont O, Bonacorsi S, Bingen E. 2000. Rapid and simple determination of Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4555–4558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Simpson E. 1949. Measurement of diversity. Nature 163:688 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chattopadhyay S, Feldgarden M, Weissman S, Dykhuizen D, Belle Gv, Sokurenko E. 2007. Haplotype diversity in source-sink dynamics of Escherichia coli urovirulence. J. Mol. Evol. 64:204–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brisse S, Diancourt L, Laouenan C, Vigan M, Caro V, Arlet G, Drieux L, Leflon-Guibout V, Mentre F, Jarlier V, Nicolas-Chanoine M. 2012. Phylogenetic distribution of CTX-M and non-extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates: group B2 isolates, except clone ST131, rarely produce CTX-M enzymes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:2974–2981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]