Abstract

B cell activating factor of the tumor necrosis factor family (BAFF) is an essential survival factor for B cells and has been shown to regulate T cell-independent (TI) IgM production. During Ehrlichia muris infection, TI IgM secretion in the spleen was BAFF dependent, and antibody-mediated BAFF neutralization led to an impairment of IgM-mediated host defense. The failure of TI plasmablasts to secrete IgM was not a consequence of alterations in their generation, survival, or early differentiation, since all occurred normally in infected mice following BAFF neutralization. Gene expression characteristic of plasma cell differentiation was also unaffected by BAFF neutralization in vivo, and except for CD138, plasmablast cell surface marker expression was unaffected. IgM was produced, since it was detected intracellularly, and impaired secretion was not due to a failure to express the IgM secretory exon. Addition of BAFF to plasmablasts in vitro rescued IgM secretion, suggesting that BAFF signaling can directly regulate secretory processes. Our findings indicate that BAFF signaling can modulate TI host defense by acting at a late stage in B cell differentiation, via its regulation of terminal plasmablast differentiation and/or IgM secretion.

INTRODUCTION

In contrast to infections with many other obligately intracellular pathogens, Ehrlichia muris infection generates a T cell-independent (TI) plasmablast response that is required for IgM-mediated immunity during both acute and chronic infection (1–3). Although originally characterized as CD11c-expressing B cells, the TI spleen plasmablasts we have described express a number of other distinctive cell surface markers, including transmembrane activator and calcium-modulating cyclophilin ligand interactor (TACI), a receptor for B cell activating factor of the tumor necrosis factor family (BAFF) (2). These observations suggested that BAFF may act to regulate the generation and/or maintenance of TI plasmablasts generated during ehrlichial infection.

BAFF is well known to play an essential role in B cell development. It is produced by nonhematopoietic stromal cells, bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, and neutrophils, and it binds to three receptors on B cells: the BAFF receptor (BAFF-R), TACI, and B cell maturation antigen (BCMA) (4). A second ligand, a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL), binds TACI and BCMA but not BAFF-R. The BAFF–BAFF-R interaction is critical for cell survival upon the egress of newly generated B cells from the bone marrow and their transition to the spleen, as evidenced by the fact that BAFF- or BAFF-R-deficient mice are severely deficient in splenic marginal zone (MZ) and follicular (FO) B cells (5, 6). In contrast, mice deficient in TACI or BCMA exhibit normal B cell maturation, essentially excluding a role for TACI or BCMA in this process (7, 8).

In the context of humoral immunity, inhibition of BAFF-induced signaling results in an impaired antibody (Ab) response to T cell-dependent (TD) antigens (Ags) (9). B cell responses to TI Ags are also defective in BAFF-R- or TACI-deficient mice, supporting a role for BAFF and/or APRIL in Ab production (10–13). Although roles for BAFF and APRIL have been investigated in the generation of humoral immunity, including primary and secondary responses to TI and TD Ags, defects in immune responses have usually been attributed to the reduction in the frequency of naïve precursor cells that occurs in the absence of these ligands (10, 14–17). Less emphasis has been placed on a role for BAFF signaling in plasmacytic differentiation and in host defense. In this study, we demonstrate that during ehrlichial infection, BAFF neutralization is associated with a defect in IgM secretion by spleen plasmablasts that impairs early immunity to intracellular bacterial infection. In the absence of BAFF, plasmablasts exhibit a transcriptional profile characteristic of plasma cells but fail to secrete IgM. Our data reveal that BAFF, by regulating a key step in terminal plasmablast differentiation and/or IgM secretion, plays an important role in host humoral immunity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice, infections, and immunizations.

C57BL/6 mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) or were bred under microisolator conditions at the Wadsworth Center Animal Care Facility, in accordance with institutional guidelines for animal welfare. Mice were infected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 5 × 104 copies of E. muris, as described previously (3). Serum BAFF was neutralized by administration of the neutralizing Ab 10F4 (100 μg/mouse; Human Genome Sciences) (14); control mice were treated with an irrelevant Armenian hamster IgG1 isotype-matched antibody.

Quantification of bacteria.

Bacterial copy numbers were determined by probe-based PCR using primers and probes for the E. muris dsb gene, as described previously (18). The limit of detection of the assay was found to be 1 copy of the dsb gene per 10 ng of mouse genomic DNA. We have made the simplifying assumption that bacterial copy numbers and numbers of viable bacteria were equivalent in our experimental model.

Flow cytometry and Abs.

Spleens were mechanically disrupted using razor blades, and bone marrow cells were obtained by flushing femurs with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) using a 23-gauge needle. Cells were disaggregated using a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon), and erythrocytes removed by hypotonic lysis using ammonium chloride. Cells were treated with anti-CD16/CD32 (2.4G2) prior to incubation with the following antibodies: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-BAFF-R (eBio7H22-E16), anti-CD49d (R1-2), anti-IgM (II/41), phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-TACI (eBio8F10-3), anti-CD29 (HMb1-1), anti-CD38 (clone 90), anti-CD40 (1C10), and peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-Cy5.5-conjugated anti-B220 (RA3-6B2) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), as well as FITC-conjugated anti-CD80 (16-10A1), anti-CD86 (GL1), PE-conjugated anti-CD138 (281-2), anti-IgM (R6-60.2), anti-CXCR4 (2B11), anti-CD62L (MEL-14), and allophycocyanin-conjugated CD11c (HL3) (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). FITC-conjugated annexin V was purchased from SouthernBiotech. The cells were stained at 4°C for 20 min, washed, and analyzed without fixation. For detection of intracellular IgM, cell surface Ags were stained, and unbound surface IgM was blocked with unlabeled polyclonal goat anti-mouse IgM (SouthernBiotech). Cells were subsequently fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% saponin, and stained with anti-IgM. Data were acquired on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer with CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson) and were analyzed with FloJo software (TreeStar, Inc.). Dead cells were excluded from analyses by using a “live-gate” strategy, based on the forward and side scatter profiles.

Flow cytometric cell sorting and in vitro culture.

Plasmablasts were purified from 10F4- and isotype control Ab-treated mice on day 9 postinfection using a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences). B220-expressing B cells were purified from uninfected mice and were used for comparison. Cells were cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), with or without the addition of 100 or 200 ng recombinant human BAFF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ).

Gene expression analysis.

RNA was extracted from purified plasmablasts using an RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using a High-Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression was determined using TaqMan-based real-time PCR for the following genes (with Applied Biosystems primer designations given in parentheses): prdm1 (Mm00476128_m1), pax5 (Mm00435501_m1), xbp1 (Mm00457360_g1), irf4 (Mm00516431_m1), sdc1 (Mm00448920_g1), and igj (Mm00461780_m1) (Applied Biosystems). The data for each gene were normalized to actb expression using the 2−ΔΔCT method (19). The following oligonucleotide primers were used for the detection of μS and μM: for μS, forward primer 5′-TCCGGAGAGACCTATACCTGTGTT-3′, reverse primer 5′-TACAGTGTGGGTTTACCAGTGGAC-3′, and probe 5′-6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-TGGTGACCG-Zen-AGAGGACCGTGGACAA-Iowa Black fluorescein quencher (IBFQ)-3′; for μM, forward primer 5′-TGCCACACCTGGTGACCGAGA-3′, reverse primer 5′-TCCACAGGTTCTCAAAGCCTTCCT-3′, and probe 5′-FAM-ACCGTGGAC-Zen-AAGTCCACTGAGG-IBFQ-3′.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analyses.

Single-cell suspensions of splenocytes, or plasmablasts purified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), were incubated in nitrocellulose plates (Millipore) coated with E. muris outer membrane protein 19 (OMP-19) or goat anti-mouse IgM. Plasmablasts were cultured with or without the addition of recombinant BAFF. Ab-secreting cells (ASCs) were detected using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM, followed by the substrate BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate)-NBT (nitroblue tetrazolium) (Amresco). OMP-19-specific serum IgM was detected as described previously (20). Plotted values are the percentages of total cells that secrete IgM, determined by dividing the number of spots in each well by the number of cells plated. The number of ASCs for each organ (spleen or bone marrow) was calculated by multiplying the percentage of ASCs by the total number of cells obtained per organ or tissue.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed using an unpaired Student t test (GraphPad Prism; GraphPad Software).

RESULTS

BAFF is required for optimal IgM immunity during bacterial infection.

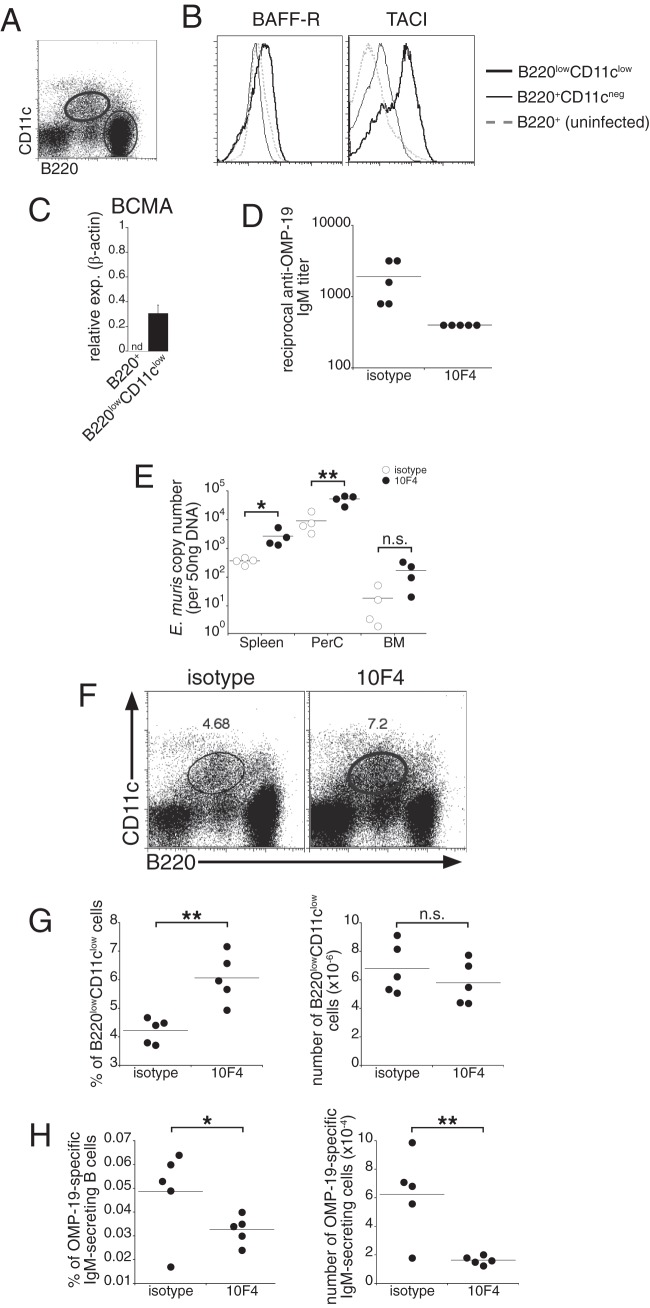

We have shown previously that E. muris infection elicits a large population of TI spleen plasmablasts that can be uniquely identified on the basis of their expression of low levels of B220 and CD11c (2). These cells express higher levels of cell surface BAFF-R and TACI, and of BCMA mRNA, than B220-positive, CD11c-negative B cells, suggesting a role for either BAFF or APRIL in their generation or function (Fig. 1A to C).

Fig 1.

BAFF signaling regulates TI IgM production during E. muris infection. (A and B) Mice were infected with E. muris, and the spleen populations indicated in the dot plot (A) were analyzed for surface expression of BAFF-R and TACI (B). Results for B220-positive B cells from an uninfected C57BL/6 mouse were included in the histograms as a control. (C) Quantitative PCR was used to determine BCMA expression (exp.) in FACS-purified cells from the indicated populations. nd, not detected. (D) Mice were administered either a BAFF-neutralizing Ab (10F4) or an isotype-matched irrelevant control Ab 3 days prior to and 3 days after infection with E. muris. Sera from infected mice were tested for IgM reactivity to OMP-19 by ELISA. The data represent Ab titers detected in individual mice. (E) The indicated tissues were isolated from control and 10F4-treated mice, and quantitative PCR analysis was performed to determine bacterial copy numbers. PerC, peritoneal cavity; BM, bone marrow. (F) Spleen cells from control and 10F4-treated mice were analyzed for expression of B220 and CD11c on day 9 postinfection. The percentages of B220low CD11clow cells are shown. (G) Frequencies and numbers of plasmablasts in the spleens of control and 10F4-treated mice. (H) ELISPOT analysis was used to determine the frequency and number of Ag-specific IgM-secreting cells in the spleen on day 9 postinfection. Dots represent values for individual mice, and horizontal lines indicate the means. The data are representative of at least three experiments that used 4 to 5 animals per group. A Student t test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of differences. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant.

To address whether BAFF signaling played a role in ehrlichial immunity, we administered a BAFF-neutralizing Ab (10F4) to mice 3 days before infection and 3 days postinfection. Ab-mediated BAFF ablation was effective: in control experiments, long-term 10F4 administration eliminated most mature B cells from the spleens of C57BL/6 mice (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In 10F4-treated infected mice, the concentrations of OMP-19-specific IgM in serum were markedly diminished following BAFF neutralization, and this reduced IgM response was associated with a 10-fold increase in bacterial infection in the spleen, peritoneum, and bone marrow (Fig. 1D and E). In contrast, BAFF neutralization did not affect the generation of the B220low CD11clow spleen plasmablast population that we have shown is responsible for IgM production. Plasmablast numbers for the treated and control groups were comparable; the plasmablasts were detected at even higher frequencies in mice treated with Ab 10F4 than in those treated with irrelevant isotype-matched Abs (Fig. 1F and G), likely a consequence of effects of BAFF neutralization on spleen inflammation and cellularity. In contrast, we observed significantly lower frequencies and numbers of ehrlichial immunodominant OMP-19-specific IgM-secreting cells in the spleens of 10F4-treated mice than in those of control mice (Fig. 1H). The data indicate that BAFF signaling is necessary for optimal TI IgM responses during acute ehrlichial infection, a finding consistent with those of other studies that have described a requirement for BAFF in IgM production after immunization (14–16).

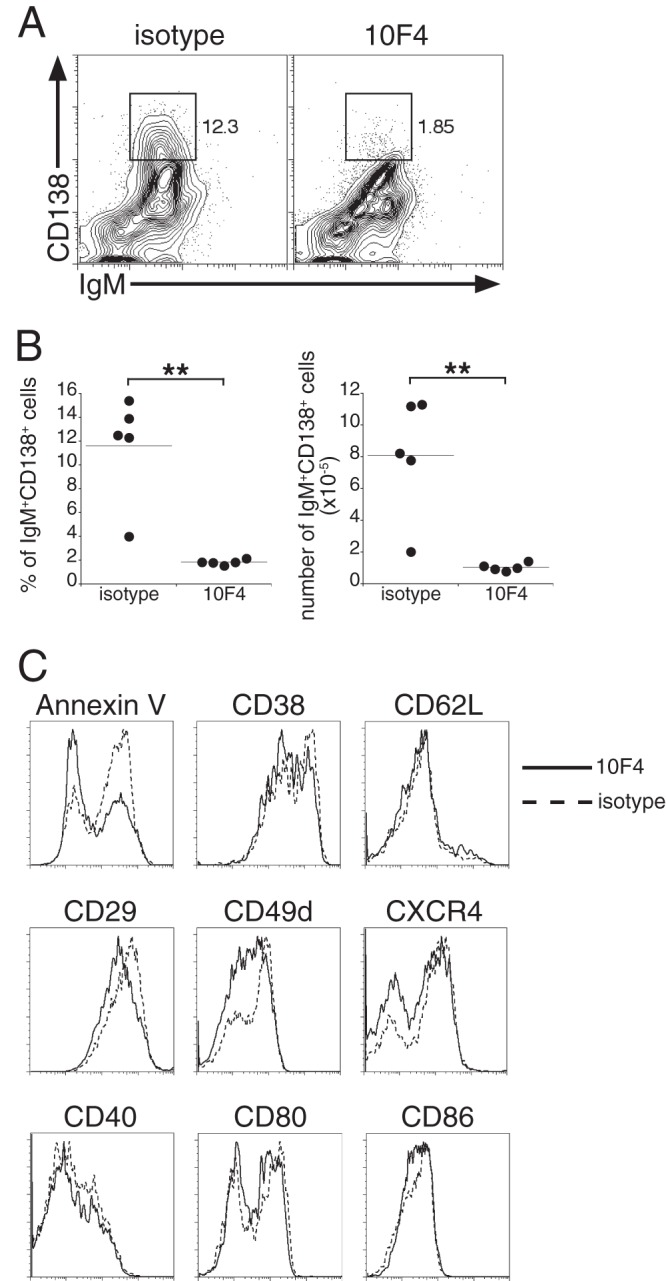

BAFF signaling is required for CD138 expression on IgM-producing plasmablasts.

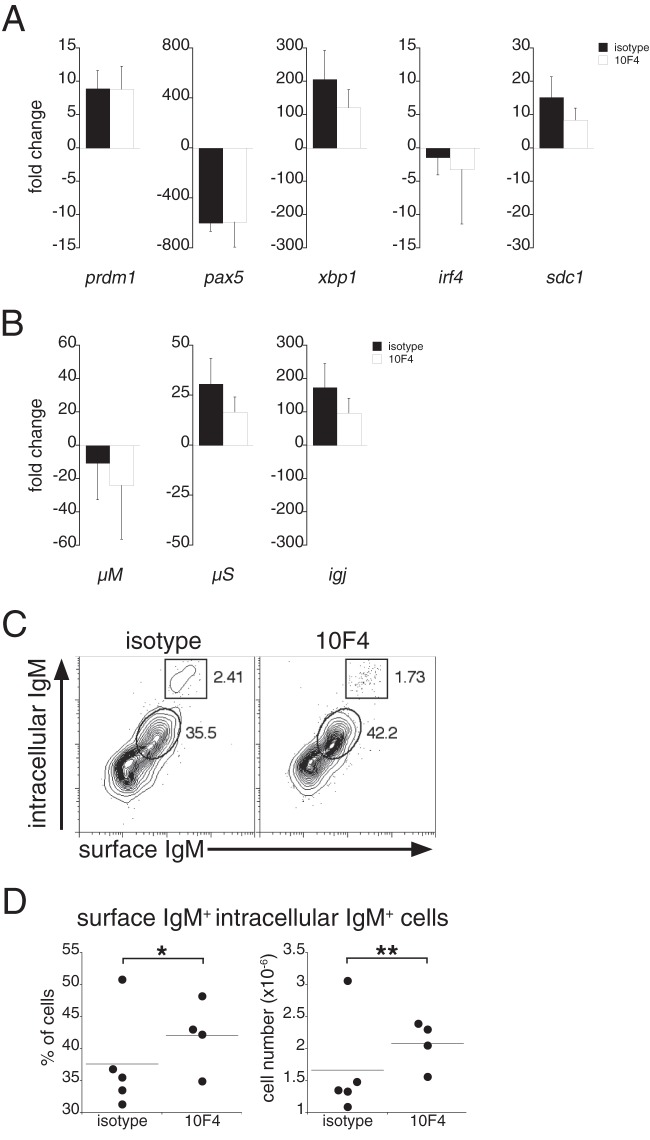

We next addressed whether BAFF signaling was required for terminal plasmablast differentiation by monitoring the expression of CD138, a cell surface marker commonly used to identify ASCs. BAFF neutralization nearly eliminated the plasmablasts expressing CD138 at high levels (CD138hi plasmablasts), and the number of CD138-expressing cells in the population was decreased nearly 8-fold (Fig. 2A and B). The failure to secrete IgM during BAFF blockade was not likely to be due to plasmablast apoptosis, since most plasmablasts from treated mice bound less annexin V than cells from control mice (Fig. 2C). CD138 was the only surface Ag examined that exhibited altered expression in 10F4-treated mice; analysis of cell surface markers associated with plasma cell differentiation, cell activation status, integrins, and chemokine receptors revealed no differences between BAFF-depleted and control mice (Fig. 2C). These data suggested that BAFF signaling was involved in the transcriptional control of CD138 expression and/or that of other genes in differentiating plasmablasts.

Fig 2.

BAFF signaling regulates the expression of CD138, but not that of other cell surface molecules, on TI plasmablasts. (A) B220low CD11clow plasmablasts from the spleens of control and 10F4-treated mice were analyzed for surface expression of IgM and CD138 on day 9 postinfection. The gates demarcate the CD138hi B cells. The percentages of B220low CD11clow plasmablasts that express high levels of CD138 are given on the right. (B) Frequency and number of the IgM+ CD138hi spleen cells analyzed in panel A. **, P < 0.01. (C) B220low CD11clow cells were analyzed for annexin V binding and for the expression of surface markers associated with plasma cell differentiation, adhesion and trafficking, and activation. The data are representative of three experiments in which 5 animals were analyzed per group.

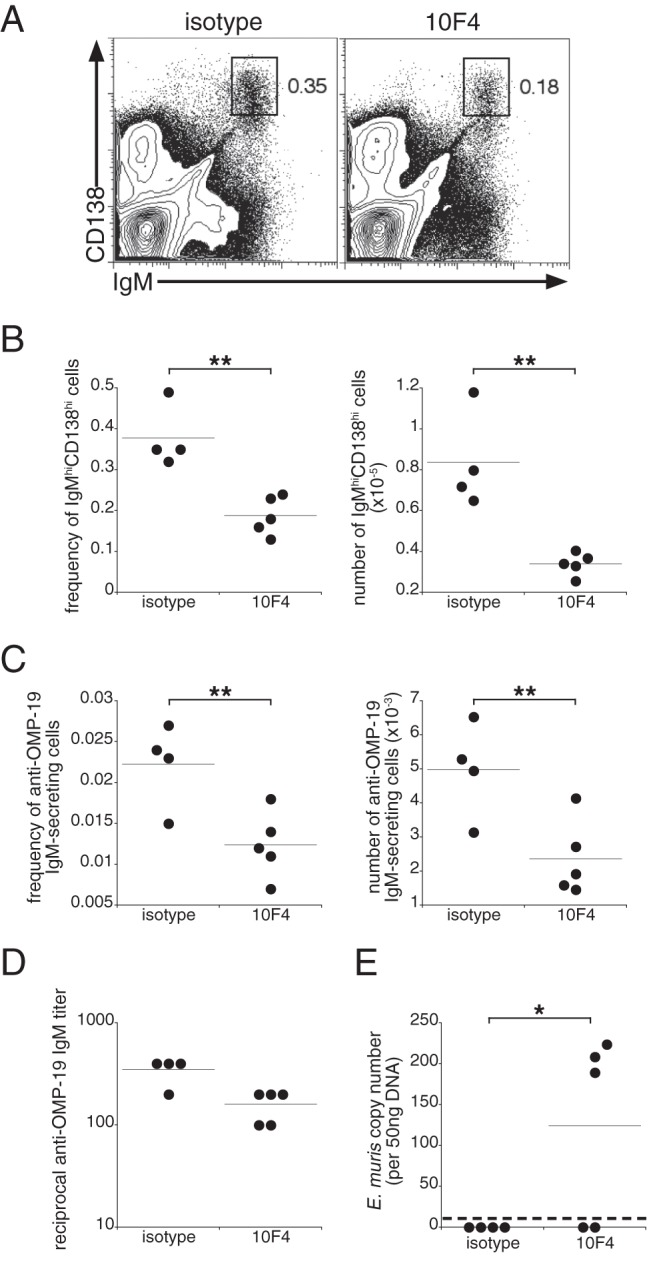

BAFF signaling is required for the maintenance of IgM production during chronic infection.

We have demonstrated in our previous studies that E. muris infection generates an IgM response responsible for long-term immunity to challenge infection (1). Long-term IgM production is maintained at least in part by a population of spleen and bone marrow plasmablasts (1). Therefore, we next addressed whether BAFF signaling was also required to maintain IgM production during low-level chronic infection. In these studies, the BAFF-neutralizing antibody was administered on days 63, 70, and 77 postinfection, and B cells were monitored in the bone marrow on day 79 postinfection. BAFF neutralization reduced the frequency and number of CD138hi IgMhi plasmablasts that were detected in the bone marrow (Fig. 3A and B). ELISPOT analyses also revealed declines in the frequency and number of OMP-19-specific IgM-producing cells (Fig. 3C). The reductions in the frequency and number of Ag-specific IgM-secreting cells in the bone marrow were accompanied by a modest decline in serum OMP-19-specific IgM titers (Fig. 3D) and caused bacterial recrudescence in 3 of the 5 treated mice (Fig. 3E). These data indicate that BAFF plays a role in the survival of ASCs and/or in their maintenance in the bone marrow and that depletion of BAFF negatively affects the maintenance of serological memory for the ehrlichiae.

Fig 3.

BAFF signaling is required for the maintenance of IgM production during chronic infection. (A) A BAFF-neutralizing antibody was administered on days 63, 70, and 77 postinfection, and bone marrow cells were analyzed for surface expression of IgM and CD138 on day 79 postinfection. The gated regions indicate the long-term IgM-producing plasmablasts identified in our previous studies (1), and percentages are given on the right. (B) Frequency and number of IgMhi CD138hi bone marrow plasmablasts identified using the gating strategy shown in panel A. (C) Frequency and number of OMP-19-specific IgM-secreting cells enumerated by an ELISPOT assay. Data represent values calculated from one femur and tibia for each mouse. (D) Titers of OMP-19-specific IgM in sera from control and treated mice. (E) Peritoneal exudates were isolated from mice on day 79 postinfection, and E. muris copy numbers were determined using quantitative PCR. The dashed line indicates the limit of detection of our assay. The data are representative of two experiments using 4 to 5 mice per group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

BAFF regulates IgM production posttranscriptionally.

The regulation of gene expression in ASCs is mediated by the transcription factor Blimp-1, encoded by prdm1 (21). Via its inhibition of the repressor Pax5, Blimp-1 initiates the activation of numerous transcription factors involved in plasma cell differentiation (21). To address the molecular mechanisms responsible for the apparent lack of IgM secretion in BAFF-depleted mice, we purified B220low CD11clow plasmablasts on day 9 postinfection and monitored the gene expression of several transcription factors associated with plasma cell differentiation. Compared to gene expression in B220-positive, CD11c-negative B cells from uninfected mice, plasmablasts from both 10F4- and isotype control Ab-treated mice exhibited gene transcription profiles characteristic of ASCs, including, most notably, increased expression of prdm1 and xbp1 and reduced expression of pax5 (Fig. 4A). However, although sdc1 mRNA (encoding syndecan-1 [CD138]) was expressed at similar levels in the treated and control groups (Fig. 4A), we failed to detect CD138 on the surfaces of plasmablasts from 10F4-treated mice (Fig. 2A). Plasmablasts isolated from both treatment groups exhibited reduced expression of membrane-bound IgM (encoded by μM), expressed mRNA encoding the secretory IgM exon (μS), and produced J-chain transcripts (igj), suggesting that IgM pentamers were assembled (Fig. 4B). No major differences were observed between the treated and control groups with respect to the expression of any of the genes examined (including irf4), suggesting that BAFF signaling functions to regulate IgM secretion posttranscriptionally. Consistent with this interpretation, intracellular IgM was detected in plasmablasts from 10F4-treated mice, and the frequency and cell number of the major population of IgM-expressing cells in 10F4-treated mice were higher than those in control Ab-treated mice (Fig. 4C and D; validation of the experimental approach is provided in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). An uncharacterized minor population of IgMhi cells was detected in both groups of mice; the total number of these cells declined modestly in 10F4-treated mice (data not shown). These data, taken together, indicate that BAFF regulates a posttranscriptional checkpoint in plasmacytic differentiation, downstream of Blimp-1 and XBP-1 expression, and suggest that BAFF signaling is required for the secretion of fully assembled IgM.

Fig 4.

Plasmablasts exhibit a transcriptional profile characteristic of ASCs and express intracellular IgM. (A and B) B220low CD11clow spleen plasmablasts were purified by FACS from control and 10F4-treated mice on day 9 postinfection, and mRNA was isolated for gene expression analysis. The data show the expression of the indicated genes in plasmablasts isolated from infected mice relative to that in B220-positive spleen cells purified from uninfected mice. Gene expression values were normalized to actb expression values. The differences between control and 10F4-treated samples were not significant, as determined using a Student t test. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (C) B220low CD11clow plasmablasts from the spleens of control and 10F4-treated mice were analyzed for surface and intracellular IgM. Cells expressing both surface IgM and intracellular IgM (enclosed by ovals) and a minor population of IgMhi cells (boxed) are gated, and percentages are given on the right. (D) Frequency and number of cells positive for both surface IgM and intracellular IgM. The data are representative of two experiments that utilized 4 to 5 mice per group. For gene expression analyses, pooled splenocytes from 4 to 5 mice per group (control and 10F4 treated) were purified by FACS. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

BAFF administration in vitro restored IgM secretion by plasmablasts.

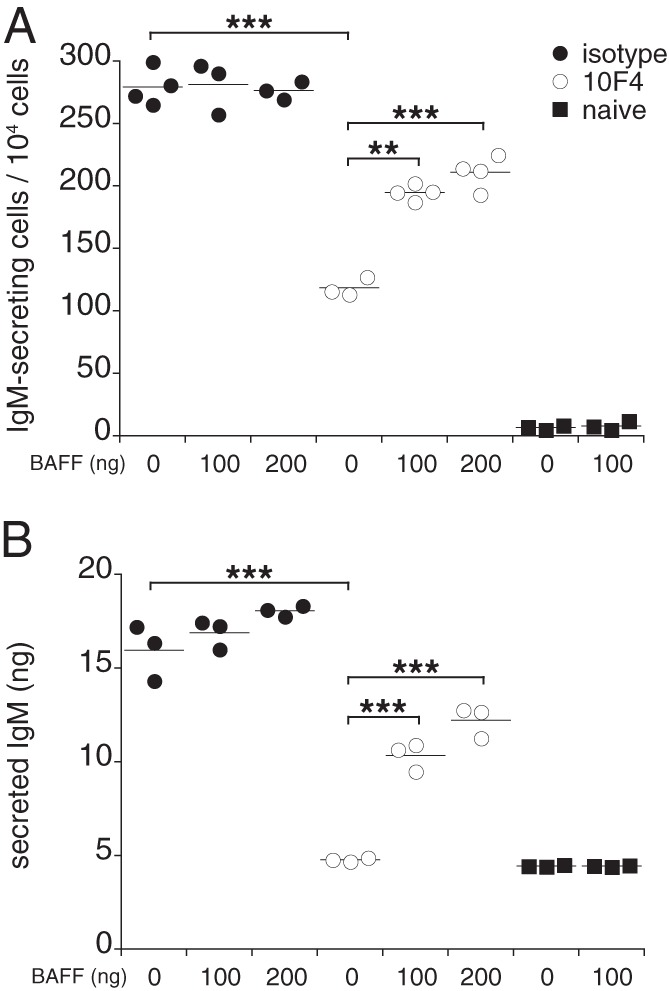

The detection of IgM within plasmablasts from BAFF-depleted mice suggested that BAFF acts at a terminal stage in plasmablast differentiation, after IgM synthesis and assembly, by regulating Ab secretion. To address this question directly, we purified plasmablasts from 10F4-treated mice 9 days postinfection and cultured the cells with or without recombinant human BAFF, since mouse B cells are fully responsive to human BAFF. The addition of BAFF did not affect the number of IgM-secreting cells obtained from mice treated with a control Ab; in contrast, recombinant BAFF restored IgM production by BAFF-depleted plasmablasts in vitro (Fig. 5A). BAFF signaling reversed the apparent blockade in IgM secretion quite rapidly: IgM was detected in culture supernatants as early as 1 h following BAFF addition (Fig. 5B). BAFF administration did not restore CD138 expression on plasmablasts (data not shown), however, indicating that additional time or other in vivo signals are required for BAFF-mediated induction of CD138 expression.

Fig 5.

BAFF restored IgM secretion by plasmablasts in vitro. B220low CD11clow spleen plasmablasts were purified from control and 10F4-treated mice on day 9 postinfection, and the cells were cultured for 12 h with or without the addition of 100 ng or 200 ng recombinant human BAFF. (A) ELISPOT analysis was used to determine the number of IgM-secreting cells. (B) IgM was measured in culture supernatants 1 h after the addition of BAFF. The data are representative of three experiments, in which each group contained splenocytes pooled from 2 to 4 mice. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Our findings support a novel role for BAFF in antibacterial immunity, via its regulation of IgM production by TI plasmablasts. Ours is not the only study to describe a defect in TI B cell responses in the absence of BAFF signaling: BAFF-deficient mice mount limited IgM responses to Pneumovax immunization, and TACI-deficient B cells secrete reduced amounts of IgM (10, 11, 13). As part of larger studies of the role of meningococcal type C polysaccharide in suppressing BAFF signaling, Kanswal et al. demonstrated that BAFF signaling promoted IgM secretion in vitro (22, 23), and BAFF signaling has been shown to promote IgM production in B cells obtained from Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia patients (24). Coadministration of a BAFF-expressing recombinant adenovirus during immunization with heat-killed Pseudomonas aeruginosa increased pathogen-specific IgM responses (25). Our studies, which were also performed in an infectious-disease setting, demonstrate that BAFF signaling can play an important role in infections where IgM contributes to host defense.

Diminished Ab responses to both TD and TI Ags in the absence of BAFF and/or APRIL have usually been attributed to a reduction in the pool of responding precursor cells (i.e., splenic MZ and FO B cell subsets) (14–17). Our data are not compatible with such an explanation for the decrease in IgM synthesis, since we detected similar numbers of IgM-expressing plasmablasts in BAFF-depleted and control mice. Moreover, the expression of cell surface markers and mRNA encoding key B cell differentiation factors was largely unaffected by BAFF neutralization. One notable exception was CD138 (syndecan-1), which was not expressed at high levels in 10F4-treated mice, suggesting that CD138 expression may be coupled to IgM secretion. However, in vivo treatment of plasmablasts with recombinant BAFF largely rescued IgM secretion but not CD138 expression, indicating that the regulation of CD138 and that of IgM expression are temporally distinct. The incomplete rescue of IgM secretion, compared to the control phenotype, could be attributed to several factors, such as (i) insufficient time to fully restore IgM secretion, (ii) an insufficient amount of recombinant BAFF, and (iii) a lack of additional soluble factors and/or costimulatory interactions. The failure to rescue CD138 expression may have been due to the lack of interleukin 4 (IL-4) and/or CD40 stimulation, since TACI signaling in the presence of these factors increased the frequency of CD138-expressing cells in vitro in Ig-secreting plasmablasts (26).

Although we did not directly address a role for APRIL in our studies, our data suggest that a role for APRIL in promoting TI IgM secretion, if any, is nonredundant with respect to BAFF signaling. It has been proposed that BAFF signaling may play a direct role in Ab production (10), but the mechanism(s) responsible for BAFF-mediated IgM production is not known. Our findings suggest that IgM synthesis in plasmablasts is regulated posttranscriptionally. We propose that during bacterial infection, TI plasmablasts efficiently initiate plasmacytic differentiation, assemble IgM, and are poised to secrete Ab but that BAFF signaling is required during differentiation to facilitate IgM secretion. The apparent rapidity with which IgM is produced in vitro suggests that BAFF signaling, likely via TACI (27) and perhaps via other receptors, regulates a late step in IgM assembly or polymerization mediated by endoplasmic reticulum (ER)- or Golgi apparatus-resident chaperone molecules (28–30), or regulates the secretory process itself.

Our findings demonstrate that the generation of TI plasmablasts in the spleen during bacterial infection is BAFF independent and that BAFF acts instead to regulate plasmablast terminal differentiation and/or IgM secretion. Thus, although current therapies target BAFF for the treatment of autoimmune disorders (31), BAFF also plays an important role in the regulation of TI microbial immunity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Renjie Song of the Wadsworth Center Immunology Core Facility for excellent technical assistance and Karen Chave, of the Northeast Biodefense Center Expression Core Facility for the production of recombinant OMP-19. We also thank Thi-Sau Migone and Human Genome Sciences for providing antibody 10F4.

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, NIH, NIAID (grant R01AI064678 to G.M.W.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 September 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00998-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Racine R, McLaughlin M, Jones DD, Wittmer ST, MacNamara KC, Woodland DL, Winslow GM. 2011. IgM production by bone marrow plasmablasts contributes to long-term protection against intracellular bacterial infection. J. Immunol. 186:1011–1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Racine R, Chatterjee M, Winslow GM. 2008. CD11c expression identifies a population of extrafollicular antigen-specific splenic plasmablasts responsible for CD4 T-independent antibody responses during intracellular bacterial infection. J. Immunol. 181:1375–1385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bitsaktsis C, Nandi B, Racine R, MacNamara KC, Winslow G. 2007. T-cell-independent humoral immunity is sufficient for protection against fatal intracellular ehrlichia infection. Infect. Immun. 75:4933–4941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorelik L, Gilbride K, Dobles M, Kalled SL, Zandman D, Scott ML. 2003. Normal B cell homeostasis requires B cell activation factor production by radiation-resistant cells. J. Exp. Med. 198:937–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiemann B, Gommerman JL, Vora K, Cachero TG, Shulga-Morskaya S, Dobles M, Frew E, Scott ML. 2001. An essential role for BAFF in the normal development of B cells through a BCMA-independent pathway. Science 293:2111–2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackay F, Browning JL. 2002. BAFF: a fundamental survival factor for B cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:465–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackay F, Schneider P, Rennert P, Browning J. 2003. BAFF AND APRIL: a tutorial on B cell survival. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21:231–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu S, Lam KP. 2001. B-cell maturation protein, which binds the tumor necrosis factor family members BAFF and APRIL, is dispensable for humoral immune responses. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4067–4074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu G, Boone T, Delaney J, Hawkins N, Kelley M, Ramakrishnan M, McCabe S, Qiu WR, Kornuc M, Xia XZ, Guo J, Stolina M, Boyle WJ, Sarosi I, Hsu H, Senaldi G, Theill LE. 2000. APRIL and TALL-I and receptors BCMA and TACI: system for regulating humoral immunity. Nat. Immunol. 1:252–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shulga-Morskaya S, Dobles M, Walsh ME, Ng LG, MacKay F, Rao SP, Kalled SL, Scott ML. 2004. B cell-activating factor belonging to the TNF family acts through separate receptors to support B cell survival and T cell-independent antibody formation. J. Immunol. 173:2331–2341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Bülow GU, van Deursen JM, Bram RJ. 2001. Regulation of the T-independent humoral response by TACI. Immunity 14:573–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia XZ, Treanor J, Senaldi G, Khare SD, Boone T, Kelley M, Theill LE, Colombero A, Solovyev I, Lee F, McCabe S, Elliott R, Miner K, Hawkins N, Guo J, Stolina M, Yu G, Wang J, Delaney J, Meng SY, Boyle WJ, Hsu H. 2000. TACI is a TRAF-interacting receptor for TALL-1, a tumor necrosis factor family member involved in B cell regulation. J. Exp. Med. 192:137–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bossen C, Cachero TG, Tardivel A, Ingold K, Willen L, Dobles M, Scott ML, Maquelin A, Belnoue E, Siegrist CA, Chevrier S, Acha-Orbea H, Leung H, Mackay F, Tschopp J, Schneider P. 2008. TACI, unlike BAFF-R, is solely activated by oligomeric BAFF and APRIL to support survival of activated B cells and plasmablasts. Blood 111:1004–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scholz JL, Crowley JE, Tomayko MM, Steinel N, O'Neill PJ, Quinn WJ, III, Goenka R, Miller JP, Cho YH, Long V, Ward C, Migone TS, Shlomchik MJ, Cancro MP. 2008. BLyS inhibition eliminates primary B cells but leaves natural and acquired humoral immunity intact. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:15517–15522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benson MJ, Dillon SR, Castigli E, Geha RS, Xu S, Lam KP, Noelle RJ. 2008. The dependence of plasma cells and independence of memory B cells on BAFF and APRIL. J. Immunol. 180:3655–3659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramanujam M, Wang X, Huang W, Liu Z, Schiffer L, Tao H, Frank D, Rice J, Diamond B, Yu KO, Porcelli S, Davidson A. 2006. Similarities and differences between selective and nonselective BAFF blockade in murine SLE. J. Clin. Invest. 116:724–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolf AI, Mozdzanowska K, Quinn WJ, III, Metzgar M, Williams KL, Caton AJ, Meffre E, Bram RJ, Erickson LD, Allman D, Cancro MP, Erikson J. 2011. Protective antiviral antibody responses in a mouse model of influenza virus infection require TACI. J. Clin. Invest. 121:3954–3964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stevenson HL, Jordan JM, Peerwani Z, Wang HQ, Walker DH, Ismail N. 2006. An intradermal environment promotes a protective type-1 response against lethal systemic monocytotropic ehrlichial infection. Infect. Immun. 74:4856–4864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 3:1101–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones DD, DeIulio GA, Winslow GM. 2012. Antigen-driven induction of polyreactive IgM during intracellular bacterial infection. J. Immunol. 189:1440–1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaffer AL, Shapiro-Shelef M, Iwakoshi NN, Lee AH, Qian SB, Zhao H, Yu X, Yang L, Tan BK, Rosenwald A, Hurt EM, Petroulakis E, Sonenberg N, Yewdell JW, Calame K, Glimcher LH, Staudt LM. 2004. XBP1, downstream of Blimp-1, expands the secretory apparatus and other organelles, and increases protein synthesis in plasma cell differentiation. Immunity 21:81–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanswal S, Katsenelson N, Allman W, Uslu K, Blake MS, Akkoyunlu M. 2011. Suppressive effect of bacterial polysaccharides on BAFF system is responsible for their poor immunogenicity. J. Immunol. 186:2430–2443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanswal S, Katsenelson N, Selvapandiyan A, Bram RJ, Akkoyunlu M. 2008. Deficient TACI expression on B lymphocytes of newborn mice leads to defective Ig secretion in response to BAFF or APRIL. J. Immunol. 181:976–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elsawa SF, Novak AJ, Grote DM, Ziesmer SC, Witzig TE, Kyle RA, Dillon SR, Harder B, Gross JA, Ansell SM. 2006. B-lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) stimulates immunoglobulin production and malignant B-cell growth in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Blood 107:2882–2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tertilt C, Joh J, Krause A, Chou P, Schneeweiss K, Crystal RG, Worgall S. 2009. Expression of B-cell activating factor enhances protective immunity of a vaccine against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 77:3044–3055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castigli E, Wilson SA, Elkhal A, Ozcan E, Garibyan L, Geha RS. 2007. Transmembrane activator and calcium modulator and cyclophilin ligand interactor enhances CD40-driven plasma cell differentiation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 120:885–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katsenelson N, Kanswal S, Puig M, Mostowski H, Verthelyi D, Akkoyunlu M. 2007. Synthetic CpG oligodeoxynucleotides augment BAFF- and APRIL-mediated immunoglobulin secretion. Eur. J. Immunol. 37:1785–1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimizu Y, Meunier L, Hendershot LM. 2009. pERp1 is significantly up-regulated during plasma cell differentiation and contributes to the oxidative folding of immunoglobulin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:17013–17018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anelli T, Ceppi S, Bergamelli L, Cortini M, Masciarelli S, Valetti C, Sitia R. 2007. Sequential steps and checkpoints in the early exocytic compartment during secretory IgM biogenesis. EMBO J. 26:4177–4188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cortini M, Sitia R. 2010. ERp44 and ERGIC-53 synergize in coupling efficiency and fidelity of IgM polymerization and secretion. Traffic 11:651–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Z, Davidson A. 2011. BAFF and selection of autoreactive B cells. Trends Immunol. 32:388–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.