Abstract

A large subgroup of the repeat in toxin (RTX) family of leukotoxins of Gram-negative pathogens consists of pore-forming hemolysins. These can permeabilize mammalian erythrocytes (RBCs) and provoke their colloid osmotic lysis (hemolytic activity). Recently, ATP leakage through pannexin channels and P2X receptor-mediated opening of cellular calcium and potassium channels were implicated in cell permeabilization by pore-forming toxins. In the study described here, we examined the role played by purinergic signaling in the cytolytic action of two RTX toxins that form pores of different sizes. The cytolytic potency of ApxIA hemolysin of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, which forms pores about 2.4 nm wide, was clearly reduced in the presence of P2X7 receptor antagonists or an ATP scavenger, such as pyridoxalphosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonic acid (PPADS), Brilliant Blue G, ATP oxidized sodium salt, or hexokinase. In contrast, antagonists of purinergic signaling had no impact on the hemolytic potency of the adenylate cyclase toxin-hemolysin (CyaA) of Bordetella pertussis, which forms pores of 0.6 to 0.8 nm in diameter. Moreover, the conductance of pores formed by ApxIA increased with the toxin concentration, while the conductance of the CyaA single pore units was constant at various toxin concentrations. However, the P2X7 receptor antagonist PPADS inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner the exacerbated hemolytic activity of a CyaA-ΔN489 construct (lacking 489 N-terminal residues of CyaA), which exhibited a strongly enhanced pore-forming propensity (>20-fold) and also formed severalfold larger conductance units in planar lipid bilayers than intact CyaA. These results point to a pore size threshold of purinergic amplification involvement in cell permeabilization by pore-forming RTX toxins.

INTRODUCTION

The repeat in toxin (RTX) proteins represent a family of proteins exhibiting a wide range of activities and molecular masses ranging from 40 to 600 kDa (1). A prominent group of RTX proteins consists of toxins mostly exhibiting cytotoxic pore-forming activity, which was first detected as a hemolytic halo surrounding bacterial colonies grown on blood agar plates (2, 3). Biophysical studies have shown that RTX toxins form cation-selective pores of a defined size and with short lifetimes of only a few seconds (4–7). This also applies to the RTX adenylate cyclase (AC) toxin-hemolysin (CyaA, ACT, or AC-Hly) that is a key virulence factor of the whooping cough agent Bordetella pertussis (8–10). CyaA is a 1,706-residue-long (177-kDa) bifunctional protein that consists of an amino-terminal adenylate cyclase domain of about 400 N-terminal residues and of an RTX cytolysin moiety of about 1,306 residues (11, 12). The RTX moiety inserts into cellular membranes and mediates translocation of the AC domain into the cytosol, where it binds calmodulin and catalyzes conversion of ATP to cyclic AMP (cAMP), thereby subverting cellular signaling (13). In parallel, the RTX moiety of CyaA can form cation-selective pores that mediate the efflux of cytosolic potassium ions from cells (4, 14–16), eventually provoking colloid osmotic cell lysis. This hemolytic activity synergizes with the cytotoxic signaling of the translocated AC enzyme in bringing about the final cytotoxic action of CyaA (14, 17, 18). The capacity of CyaA to penetrate cellular membranes, to form pores, and to deliver the AC domain into cells depends on covalent posttranslational fatty acylation of pro-CyaA at the ε amino groups of the internal lysine residues Lys-983 and Lys-860 by a coexpressed protein acyltransferase, CyaC (19–24). Toxin activities further require binding of calcium ions to the numerous sites formed in the RTX domain by the glycine- and aspartate-rich repetitions (25–27). Indirect evidence suggests that formation of CyaA pores involves oligomerization of membrane-embedded CyaA monomers (4, 7, 15, 28–30). Moreover, the propensity of CyaA to form the dynamic and unstable oligomeric pores is modulated by the character of attached fatty acyl chains (21, 23, 31), as well as by charge-reverting substitutions of glutamate residues in the pore-forming domain of CyaA by lysines, such as the substitutions E509K, E516K, E570Q, and E581K (16, 17, 28, 30). The stoichiometry of the pore-forming oligomers of CyaA remains to be defined, while the toxin concentration dependency of the membrane-permeabilizing activity would suggest the formation of CyaA trimers or tetramers (7, 28). Nevertheless, the small diameter of the CyaA pores of only 0.6 to 0.8 nm was derived from both osmotic protection experiments and single-channel measurements in planar lipid bilayers (4, 32).

In contrast, a substantially larger pore size of about 2.4 nm was determined for the ApxIA toxin produced by Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, the etiological agent of swine pleuropneumonia (6, 33). ApxIA is a toxin with molecular mass of 105 kDa that exhibits the typical features of hemolytic RTX leukotoxins, including the hydrophobic domain and 13 glycine- and aspartate-rich nonapeptide repeats (34). ApxIA is strongly hemolytic on porcine red blood cells (RBCs) and is also cytotoxic on a broad range of cells of different types and species (35, 36).

Recently, it was shown that the hemolytic capacity on red blood cells of pores formed by other members of the RTX toxin family, namely, the Escherichia coli alpha-hemolysin (HlyA) and the Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans LtxA toxin, is potentiated by a mechanism that involves release of intracellular ATP, probably through the pannexin 1 channel, and triggers activation of P2X receptors. This appears to amplify cell lysis by increasing the overall permeability of the membrane of erythrocytes for calcium and potassium ions (37, 38). P2X receptors were further suggested to play a role in modulation of HlyA-induced phagocytosis of erythrocytes by human monocytes (39), and amplification of red blood cell lysis through P2X receptors was also demonstrated for Staphylococcus aureus alpha-toxin (40). Recently, the involvement of the P2X7 receptor in A. actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin-induced proinflammatory macrophage cell death was documented (41). These mechanisms appear to be mediated by pannexins, which can form large nonselective membrane hemichannels that allow the flux of small ions and ATP across the plasma membrane (42). Pannexin 1 has been found to be physically associated with the P2X7 receptor (43), and activation of the P2X7 receptor by ATP was shown to open both cation-specific and large nonselective cell membrane channels (44, 45) that trigger several pathways leading to cell death (46).

In the present work, we investigated the involvement of purinergic signaling in CyaA- and ApxIA-mediated erythrocyte lysis. We show that both RTX toxins cause a rise in the volume of erythrocytes prior to cell lysis and that specific antagonists of the P2X7 receptor block the ApxIA-induced lysis of sheep erythrocytes but not the lysis of sheep erythrocytes by CyaA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Pyridoxalphosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonic acid (PPADS), probenecid, carbenoxolone, ATP oxidized sodium salt (oATP), suramin, hexokinase, sucrose, l-arabinose, and l-α phosphatidylcholine (from soybean, type IIS, asolectin), trypsin, and trypsin inhibitor were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Brilliant Blue G (BBG) was purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). PPADS, carbenoxolone, oATP, and suramin were dissolved in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS; 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 3 mM MgCl2, 50 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES-Na, pH 7.4), probenecid was dissolved in 1 M Na2CO3, and BBG was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. Hoechst 33258 and tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) were from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). Dyomics 647 dye was from Dyomics (Jena, Germany).

Production and purification of CyaA, CyaA-AC−, and CyaA-ΔN489.

Intact CyaA, an AC-negative enzymatically inactive CyaA (CyaA-AC−) variant (47), and a construct lacking the 489 N-terminal residues of CyaA (CyaA-ΔN489) (48) were produced in E. coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene) transformed with the pCACT3 or pT7CACT1 construct, as appropriate (49). Exponential-phase 500-ml cultures were grown at 37°C and induced by isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG; 1 mM) for 4 h before the cells were washed in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.2 mM CaCl2, and disrupted by sonication. The insoluble cell debris was resuspended in 8 M urea, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM CaCl2. Upon centrifugation at 25,000 × g for 20 min, clarified urea extracts were loaded onto a DEAE-Sepharose column equilibrated with 8 M urea, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 120 mM NaCl. After washing, the CyaA was eluted with 8 M urea, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 2 M NaCl, diluted four times with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 M NaCl buffer, and further purified on a phenyl-Sepharose column equilibrated with the same buffer. Unbound proteins were washed out with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and the CyaA was eluted with 8 M urea, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 2 mM EDTA and stored at −20°C. The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Construction, production, and purification of ApxIA.

The pET28b-apxIA vector for the expression of the nonacylated ApxIA toxin was recently described by Sadilkova and coworkers (50). For expression of the acylated and fully active ApxIA toxin, the pET28b-apxIA vector was modified by a gene encoding ApxIA-activating lysine acyltransferase, apxIC. The apxIC sequence was amplified from genomic DNA of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 5 by PCR using forward primer 5′-GGCCATGGATGAGTAAAAAAATTAATGGATTT-3′ containing the NcoI site and reverse primer 5′-CCGCTAGCTCTAGATTAGCTATTTACTAATGAAAATTT-3′ containing NheI and XbaI sites. The PCR product was digested by NcoI and NheI restriction enzymes and ligated into the NcoI-NheI-digested pET28b vector. This construct (pET28b-apxIC) was further digested by the XbaI restriction enzyme, and the 564-bp fragment encoding the ApxIC acyltransferase enzyme was ligated into the XbaI-linearized pET28b-apxIA vector. This construct was designated pET28b-apxIC-apxIA and verified by DNA sequencing. The acylated ApxIA was produced in E. coli strain BL21(λDE3) transformed with the pET28b-apxIC-apxIA construct. Exponential-phase cultures grown with shaking at 37°C in MDO medium (yeast extract, 20 g/liter; glycerol, 20 g/liter; KH2PO4, 1 g/liter; K2HPO4, 3 g/liter; NH4Cl, 2 g/liter; Na2SO4, 0.5 g/liter; thiamine hydrochloride, 0.01 g/liter) supplemented with 60 μg/ml of kanamycin were induced at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6 with 0.5 mM IPTG and grown for an additional 4 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, and disrupted by sonication on ice. Nonbroken cells were centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 5 min, and the cell extract was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the inclusion bodies in the pellet were solubilized with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 8 M urea (TU buffer) and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min. The urea extract was loaded on a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid Sepharose column (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom), washed extensively with TU buffer containing 40 mM imidazole, and eluted by TU buffer supplemented with 200 mM imidazole. Imidazole from the samples was further removed by Sephadex G-25 (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) column chromatography. The fractions of purified ApxIA toxin were concentrated by use of a centrifugal filter unit (molecular weight cutoff, 10,000; Amicon; Millipore, Billerica, MA) and stored at −20°C for further use. The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Assay of AC, cell-binding, cell-invasive, and hemolytic activities.

Adenylate cyclase (AC) activities were measured in the presence of 1 μM calmodulin as previously described (51). One unit of AC activity corresponds to 1 μmol of cAMP formed per min at 30°C, pH 8.0. Hemolytic activities were measured in HBSS buffer as previously described (13) by determining the amount of hemoglobin released over time upon toxin incubations with washed sheep erythrocytes (5 × 108/ml in HBSS). Erythrocyte binding and cell-invasive AC activities were determined as previously described in detail (52). Briefly, sheep erythrocytes (5 × 108 cells/ml) were incubated with 50 nM CyaA at 37°C in TNC buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2). After 30 min, cell suspensions were washed three times in TNE buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA) to remove unbound CyaA and divided into two aliquots. The first aliquot was directly used to determine the amount of cell-associated AC activity (membrane-bound CyaA). The second aliquot was treated with 20 μg of trypsin for 15 min at 37°C in order to inactivate the extracellular AC toxin which did not translocate into cells. Forty micrograms of soybean trypsin inhibitor was added to stop the reaction before the samples were washed three times in TNE buffer and used to determine the amount of cell-invasive AC activity. The cell-binding and cell-invasive enzymatic activities of CyaA in the presence of antagonist were expressed as the percentages of CyaA activity in the absence of antagonist. The activity of CyaA in the absence of antagonist was taken as 100%. Erythrocyte binding of the ApxIA was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 107/ml) in HBSS buffer in the presence of 75 mM sucrose were incubated with 12.5 nM ApxIA labeled with Dyomics 647 dye at 37°C. After 120 min, unbound toxin was removed by repeated cell washes, and cell-surface-localized ApxIA- Dyomics 647 dye was detected by FACS analysis. The hemolytic activity of ApxI was measured in HBSS buffer as the amount of hemoglobin released over time upon toxin incubations with washed sheep erythrocytes (5 × 108/ml).

ApxIA and CyaA-ΔN489 labeling.

Toxins were labeled with the amine-reactive Dyomics 647 dye upon binding to phenyl-Sepharose during the last purification step in 50 mM NaHCO3, pH 8.3, at room temperature for 1 h. Unreacted dye was washed out from the resin with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), and labeled protein was eluted from phenyl-Sepharose in TUE buffer (50 mM Tris, 8 M urea, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0).

Cultivation of J774A.1 cells.

J774.A1 murine monocytes/macrophages (catalog number TIB-67; ATCC) were cultured at 37°C in a humidified air-CO2 (19:1) atmosphere in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 IU/ml), streptomycin (100 mg/ml), and amphotericin B (250 ng/ml). Prior to FACS assay, RPMI was replaced with HBSS buffer without fetal calf serum, and the cells were allowed to rest in HBSS for 30 min at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Flow cytometry.

An LSR II instrument (BD Biosciences) was used for flow cytometry, with FlowJo, version 7.6.1, software used for analysis. Erythrocyte size was assessed using forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC). For each time point, a suspension of sheep erythrocytes in HBSS buffer containing 2.5 × 107 cells/ml was used. For binding experiments, sheep erythrocytes (5 × 107/ml) in HBSS buffer in the presence of 75 mM sucrose were incubated with 12.5 nM ApxIA or 50 nM CyaA-ΔN489 labeled with Dyomics 647 dye in the presence or absence of antagonists at 37°C. After the times indicated below, cells were washed repeatedly and used to determine the amount of cell-associated toxin by FACS.

Western blotting and densitometric analysis.

Erythrocytes with bound toxin were lysed with 2× SDS gel sample buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 200 mM dithiothreitol, 4% SDS, 0.2% bromophenol blue, 20% glycerol), and the lysates were separated by 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. CyaA and CyaA-ΔN489 were probed by the anti-RTX monoclonal antibody 9D4 (at a 1:1,000 dilution) (53) and revealed by peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5,000; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) using a chemiluminescence detection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) and an LAS-1000 imaging system instrument (Fuji, Tokyo, Japan). Images were analyzed using AIDA two-dimensional densitometry software, version 2.11 (Raytest, Straubenhardt, Germany). Binding data were deduced from the integrated signal intensities of the protein bands and expressed as a percentage of CyaA binding to erythrocytes.

Lipid bilayer experiments.

Measurements on planar lipid bilayers (black lipid membranes) were performed in Teflon cells separated by a diaphragm with a circular hole (diameter, 0.5 mm) bearing the membrane. The CyaA toxin was diluted in 8 M urea, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 2 mM EDTA buffer and added into the grounded cis compartment with positive potential. The membrane was formed by the painting method using 3% soybean phosphatidylcholine (type IIS, asolectin; Sigma-Aldrich) in n-decane–butanol (9:1, vol/vol). Both compartments contained 2 ml of 10 mM Tris, 1 M KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4. The membrane current was registered by Ag/AgCl electrodes (Theta) with salt bridges (applied voltage, 20 to 90 mV), amplified by an LCA-4k-1G or LCA-200-100G amplifier (Femto), and digitized by use of a KPCI-3108 card (Keithly) and BLM2 software (Jiří Bok, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic). The signal was processed by Perl script and QuB software (http://www.qub.buffalo.edu/). The current traces were electronically filtered using a 100-Hz low-band-pass filter. The area of the lipid bilayer was controlled during the experiments by measuring the membrane capacitance using alternating sinusoidal voltage (±2 mV at 50 Hz) on top of the offset direct-current voltage. The histograms of single pore conductance units were calculated from >500 events using a 1-pS bin size and fitted with Gaussian functions using Fityk software (http://fityk.nieto.pl/).

Statistical analysis.

The significance of differences in values was assessed by Student's t test.

RESULTS

ApxIA and CyaA induce swelling and lysis of erythrocytes.

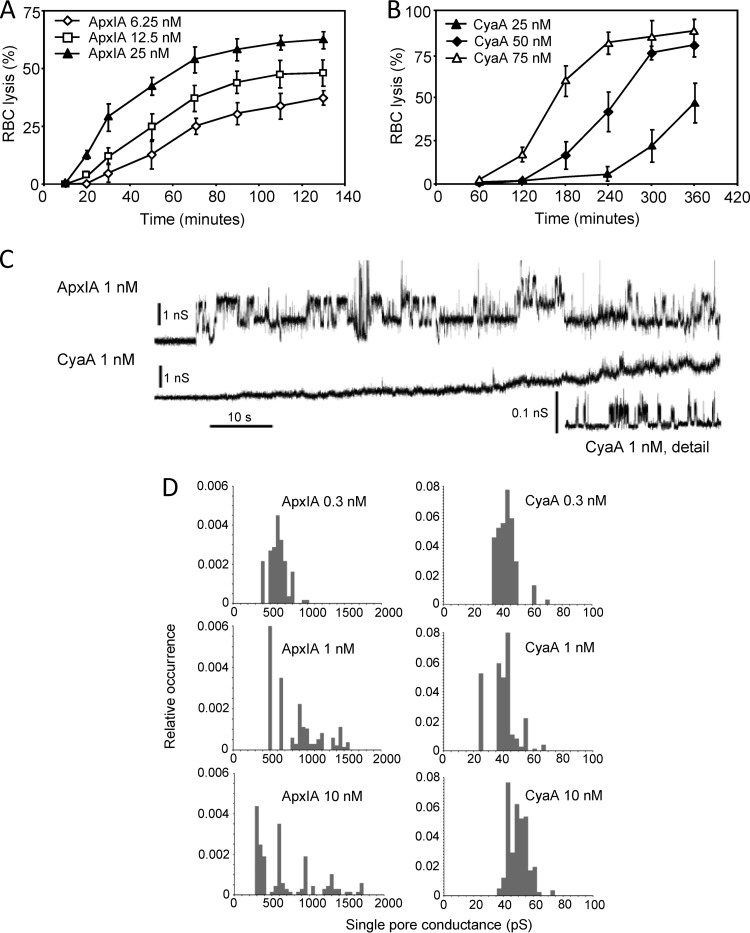

The CyaA and ApxIA leukotoxins were shown to form cation-selective pores of different sizes and with short lifetimes of only a few seconds (4, 6, 7). To compare their overall membrane permeabilization properties, we first determined their hemolytic potency toward sheep erythrocytes (RBCs). As shown in Fig. 1A and B, despite being most active on porcine cells, ApxIA still exhibited a higher hemolytic potency on sheep RBCs than CyaA. As expected from the published pore characteristics of the two toxins and in line with its lower hemolytic potency, CyaA formed considerably smaller single pore conductance units in asolectin planar lipid bilayer membranes than ApxIA, as shown in Fig. 1C. Furthermore, over a range of toxin concentrations of 0.3 to 10 nM, the conductance of single pore units formed by CyaA was constant (Fig. 1D). In contrast, an increased frequency of formation of smaller as well as of several larger single conductance units (pores) was observed with ApxIA when the toxin concentration was increased from 0.3 to 10 nM, as documented in Fig. 1D. This suggests that in contrast to CyaA, the stoichiometry of the ApxIA hemolysin pore may vary depending on the toxin concentration. This may indeed reflect a more general feature of bona fide RTX hemolysins, as the toxin concentration-dependent aggregation of E. coli RTX alpha-hemolysin (HlyA) pores into larger conductance units in lipid bilayers and larger membrane lesions within erythrocyte membranes has previously been observed (5, 54).

Fig 1.

Sheep erythrocytes are susceptible to the pore-forming activity of ApxIA and CyaA in a concentration-dependent manner. Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 108/ml) in HBSS buffer were incubated at 37°C in the presence of different concentrations of ApxIA (A) and CyaA (B). Hemolytic activity was measured as the amount of released hemoglobin by photometric determination (A541). The results represent average values from two independent experiments performed in duplicate. (C) Typical current traces of ApxIA and CyaA in asolectin lipid bilayers in 1 M KCl, 10 mM Tris, and 2 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.4). The ApxIA and CyaA concentration was 1 nM. Traces were recorded 60 s after ApxIA or CyaA addition. The applied membrane potential was 55 mV; the temperature was 25°C. All recordings were filtered at 100 Hz. The detailed recording of CyaA pores was performed at a higher current resolution. (D) The conductance of single ApxIA or CyaA pores was determined in 1 M KCl, 10 mM Tris, and 2 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.4) at membrane potentials of between 50 and 75 mV; the temperature was 25°C.

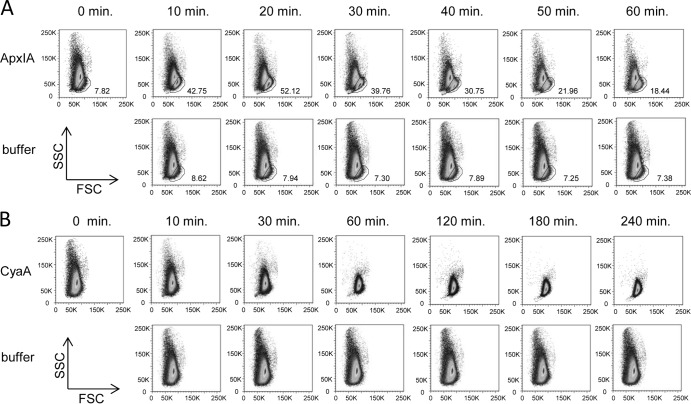

Permeabilization by pore-forming toxins results in the influx of ions and water, provoking cell swelling and colloid osmotic lysis of cells (8, 40, 55). An initial shrinkage of erythrocytes prior to subsequent swelling and lysis was, however, recently observed with RTX hemolysins HlyA and LtxA (37, 38). With both toxins, this appeared to result from an initial rise in the intracellular concentration of calcium ions that triggered activation of K+ and Cl− currents across the cell membrane. Therefore, we next used flow cytometry to assess whether ApxIA and CyaA trigger a similar process in RBCs. Cell volume changes of erythrocytes exposed to toxins were thus followed over time as forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) parameters. As shown in Fig. 2A, ApxIA triggered the early formation of a distinct subpopulation of swollen RBCs that exhibited an increased FSC and a decreased SSC, thus separating from the bulk of the cells in the FACS plot (the outlined cells in Fig. 2A). The percentage of such morphologically altered RBCs increased for up to 20 min from the time of ApxIA addition (12.5 nM) before the swollen erythrocytes started to lyse and disappear from the FACS plot. In contrast, addition of CyaA to a 50 nM concentration did not trigger the formation of any morphologically distinct subpopulations of erythrocytes (Fig. 2B). Instead, it resulted in progressive homogenization of the size (FSC) and shape (SSC) distributions of RBCs, with the mean SSC progressively decreasing and the mean FSC increasing over time to the onset of lysis. Hence, in contrast to the action of HlyA or LtxA, no initial shrinkage prior to a progressive increase in cell volume was observed after addition of either the CyaA or ApxIA toxin to sheep erythrocytes.

Fig 2.

Erythrocyte volume changes induced by ApxIA and CyaA. Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 108/ml) in HBSS buffer were incubated at 37°C in the presence of 12.5 nM ApxIA (A), 50 nM CyaA (B), or control buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 8 M urea, pH 8). The size distributions of erythrocytes represented by FSC and SSC were obtained at different times. The numbers in panel A indicate the percentage of gated nonlysed erythrocytes in the sample. The images are representative of those from three independent experiments.

ApxIA-induced lysis of erythrocytes involves purinergic amplification.

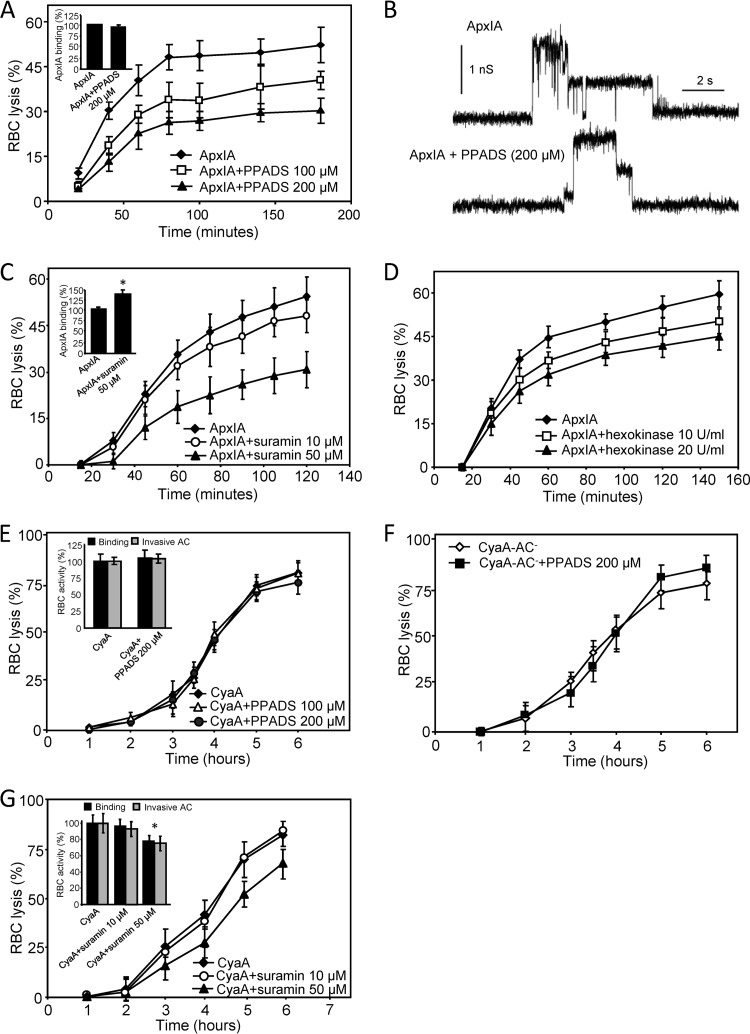

Next, we investigated whether the cytolytic action of ApxIA and CyaA was potentiated by P2X receptor activation, similar to the mode of action of HlyA, LtxA, or the alpha-toxin of S. aureus (37, 38, 40). As documented in Fig. 3A, while toxin binding to cells was not affected (inset), the extent of ApxIA-triggered erythrocyte lysis was reduced (P < 0.05) in a concentration-dependent manner in the presence of the allosteric P2 receptor antagonist pyridoxalphosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonic acid (PPADS). This was most likely not due to inhibition of the formation and activity of ApxIA pores in erythrocyte membranes, since PPADS did not inhibit the pore-forming activity of the toxin in planar lipid bilayers, as further shown in Fig. 3B. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 3C, ApxIA-triggered lysis of erythrocytes was also inhibited (P < 0.05) in the presence of the nonselective P2 antagonist suramin (50 μM), which even enhanced toxin binding to erythrocytes (inset). To further examine whether purinergic receptor activation due to ATP leakage from cells might be involved in the cytolytic action of ApxIA, the ATP scavenger hexokinase was used. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 3D, inhibition of ApxIA-induced hemolysis was observed in the presence of 20 U/ml of hexokinase (P < 0.05), indicating involvement of ATP-mediated P2X receptor activation in the process of ApxIA-induced erythrocyte lysis. In contrast, as shown in Fig. 3E, PPADS (100 and 200 μM) had no effect on the hemolytic potency of CyaA. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 3F, PPADS also failed to affect the hemolytic activity of the enzymatically inactive CyaA-AC−. The possibility that the effect of PPADS may have been masked by restriction of leakage of the P2 receptor ligand ATP (56) due to its conversion to cAMP by the AC activity of CyaA can therefore be excluded. As further shown in Fig. 3G, the hemolytic capacity of CyaA was not affected in the presence of 10 μM suramin, while at 50 μM suramin, CyaA binding to cells was decreased (inset), making it difficult to relate the resulting decrease of cell lysis to inhibition of P2 receptor activation (Fig. 3G).

Fig 3.

In contrast to CyaA-induced hemolysis, ApxIA-induced hemolysis is inhibited by nonselective P2 receptor antagonists. Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 108/ml) in HBSS buffer were preincubated for 5 min in the presence or absence of nonselective purinergic antagonist PPADS (A) or suramin (C). Hemolytic activity was measured at 37°C in the presence of 12.5 nM ApxIA as the amount of released hemoglobin by photometric determination (A541). Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 107/ml) in HBSS buffer in the presence of 75 mM sucrose were incubated with 12.5 nM ApxIA labeled with Dyomics 647 dye at 37°C. After 120 min, cells were washed repeatedly to remove unbound ApxIA and used to determine the amount of cell-associated toxin by FACS. (A and C, insets) The binding activity of ApxIA-Dyomics 647 dye in the absence of antagonist was taken to be 100%. *, statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) from the activity of ApxIA without antagonist. (B) Typical current traces of ApxIA in planar lipid bilayers in the presence or absence of PPADS (200 μM) in 1 M KCl, 10 mM Tris, and 2 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.4). The toxin concentration was 2.3 nM. The applied membrane potential was 55 mV; the temperature was 25°C. (D) Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 108/ml) in HBSS buffer were incubated in the presence or absence of hexokinase (10 and 20 U/ml). Hemolytic activity was measured at 37°C in the presence of 12.5 nM ApxIA as the amount of released hemoglobin by photometric determination (A541). Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 108/ml) in HBSS buffer were preincubated for 5 min in the presence or absence of the nonselective purinergic antagonist PPADS (E, F) or suramin (G). Hemolytic activity was measured in the presence of 50 nM CyaA (E, G) or the CyaA-AC− variant (F), as described for panel D. (E and G, insets) Cell-binding and cell-invasive activities of intact CyaA in the presence of PPADS or suramin, respectively. Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 108/ml) in HBSS buffer were incubated with 50 nM enzymatically active CyaA at 37°C in the presence or absence of antagonists. After 30 min, aliquots of the cell suspensions were washed repeatedly to remove unbound CyaA and used to determine the amount of cell-associated and cell-invasive AC enzyme activities. The activity of CyaA in the absence of antagonist was taken to be 100%. The results represent average values of at least four independent experiments. *, statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) from the activities of CyaA without inhibitor.

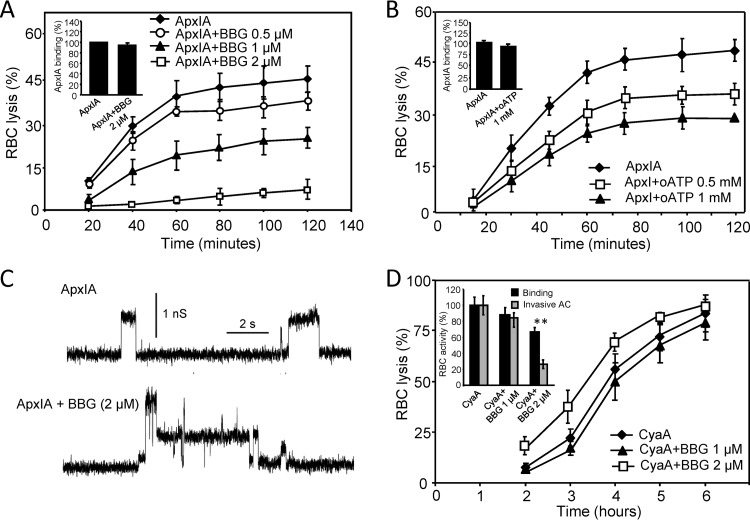

To corroborate the finding that, in contrast to the activity of CyaA, the cytolytic activity of ApxIA may be amplified by P2X receptor activation, we employed antagonists exhibiting a relative selectivity for P2X7, such as Brilliant Blue G (BBG) dye and oxidized ATP (oATP). Indeed, as shown in Fig. 4A and B, ApxIA-induced hemolysis was importantly inhibited by the BBG and oATP compounds in a concentration-dependent manner, while BBG presence had no effect on the properties of pores formed by ApxIA in asolectin membranes (Fig. 4C).

Fig 4.

ApxIA-induced hemolysis is inhibited by selective P2X7 antagonist BBG or oATP. Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 108/ml) in HBSS buffer were preincubated in the presence or absence of BBG (A) or oATP (B) for 5 or 60 min, respectively. Hemolytic activity was measured at 37°C in the presence of 12.5 nM ApxIA as the amount of released hemoglobin by photometric determination. Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 107/ml) in HBSS buffer in the presence of 75 mM sucrose were incubated with 12.5 nM ApxIA labeled with Dyomics 647 dye in the presence or absence of purinergic antagonists at 37°C. (A and B, insets) After 120 min, cells were washed repeatedly to remove unbound ApxIA and used to determine the amount of cell-associated toxin by FACS. The binding activity of ApxIA-Dyomics 647 dye in the absence of purinergic antagonist was taken to be 100%. (C) Typical current traces of ApxIA in planar lipid bilayers in the presence or absence of BBG (2 μM) in 1 M KCl, 10 mM Tris, and 2 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.4). The toxin concentration was 2.3 nM. The applied membrane potential was 55 mV; the temperature was 25°C. (D) Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 108/ml) in HBSS buffer were preincubated for 5 min in the presence or absence of BBG. Hemolytic activity was measured in the presence of 50 nM CyaA as described for panels A and B. (Inset) Cell-binding and cell-invasive activities of CyaA in the presence of BBG. Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 108/ml) in HBSS buffer were incubated with 50 nM CyaA at 37°C in the presence or absence of BBG. After 30 min, aliquots of cell suspensions were washed repeatedly to remove unbound CyaA and used to determine the amount of cell-associated and cell-invasive AC enzyme activities. The activity of CyaA in the absence of BBG was taken to be 100%. The results represent average values from at least four independent experiments. **, statistically significant differences (P < 0.001) from the activities of CyaA without inhibitor.

In contrast, the course of CyaA-induced hemolysis was not affected by 1 μM BBG, as shown in Fig. 4D, while at a 2 μM BBG concentration, an enhancement of the hemolytic potency of CyaA was observed, despite the decreased toxin binding to cells (inset). This seemingly paradoxical result is likely explained by the marked inhibition of AC domain translocation into cells by CyaA in the presence of 2 μM BBG (Fig. 4D, inset). Thus, the resulting enhancement of specific hemolytic activity of cell-bound CyaA would, indeed, likely compensate for the partly decreased cell binding of toxin (Fig. 4D, inset). In this respect, the impact of BBG on CyaA activity would, intriguingly, mimic the impact of certain substitutions in the pore-forming region of CyaA (e.g., E509P, E516P, and E581K) or 3D1 antibody binding to the C-proximal segment of the AC domain of CyaA, both of which impair AC domain translocation into cells and at the same time exacerbate the specific hemolytic (pore-forming) potency of the cell-bound toxin (14, 18, 28, 30, 48).

It can hence be concluded that activation of the P2X7 receptor was not involved in amplification of CyaA-induced colloid osmotic lysis of erythrocytes, as this was not affected at the concentrations of P2X antagonists that inhibited ApxIA-induced lysis and that were shown to protect erythrocytes from lysis by other pore-forming toxins (37, 38, 40).

Cell lysis induced by a hyperhemolytic CyaA-ΔN489 variant is potentiated by purinergic signaling.

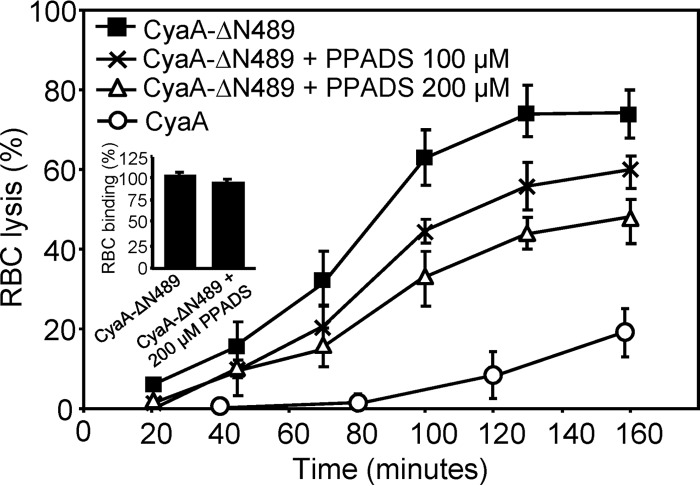

The hemolytic capacity of CyaA is generally considered to be relatively weak, and one potential reason for this appears to be the competition between the AC-translocating and pore-forming conformations of CyaA within the erythrocyte membrane (16, 28). It has previously been shown that the specific hemolytic potency of CyaA was importantly enhanced upon deletion of residues 6 to 489 (CyaA-ΔN489), which comprise the translocated AC domain and an adjacent membrane-interacting segment (48, 57). We thus examined the pore-forming properties of the truncated CyaA-ΔN489 toxoid. As shown in Fig. 5, erythrocyte lysis induced by CyaA-ΔN489 was inhibited by PPADS at 100 μM and 200 μM concentrations, while PPADS did not affect the binding of CyaA-ΔN489 to RBCs (Fig. 5, inset). Hence, lysis of RBCs exposed to CyaA-ΔN489 appeared to be accelerated by purinergic signaling, most likely triggered by ATP leaking from RBCs.

Fig 5.

The lysis of erythrocytes induced by CyaA-ΔN489 is partially inhibited by PPADS. Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 108/ml) in HBSS buffer were preincubated for 5 min in the presence or absence of PPADS (100 and 200 μM), and hemolytic activity was measured at 37°C in the presence of 50 nM CyaA-ΔN489 or intact CyaA as the amount of released hemoglobin by photometric determination (A541). The results represent average values from three independent experiments. Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 107/ml) in HBSS buffer in the presence of 75 mM sucrose were incubated with 50 nM CyaA-ΔN489 labeled with Dyomics 647 dye at 37°C. After 30 min, cells were washed repeatedly to remove unbound CyaA-ΔN489 and used to determine the amount of cell-associated toxin by FACS. (Inset) The binding activity of CyaA-ΔN489–Dyomics 647 dye in the absence of PPADS was taken to be 100%.

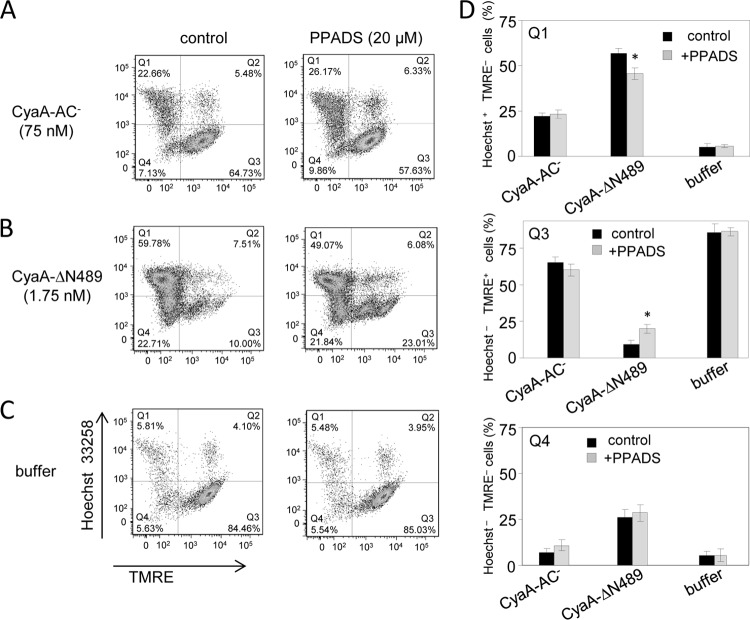

We thus next examined if purinergic amplification was also contributing to CyaA-mediated lysis of CD11b-expressing phagocyte targets, such as CD11b+ J774A.1 mouse macrophages. These cells are primarily killed by the cytotoxic cAMP signaling and ATP depletion provoked by the AC enzyme activity of CyaA. Due to an intact pore-forming capacity, however, on J774A.1 cells the fully hemolytic but enzymatically inactive CyaA-AC− toxoid still preserved about 1/10 of the cytolytic potency of CyaA (17). J774A.1 cells labeled with the TMRE sensor of mitochondrial potential were, hence, incubated for 2 h with the CyaA-AC− or the CyaA-ΔN489 toxoid and the proportion of live and necrotic cells was determined by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 6, the proportion of live cells (quadrant Q3; Hoechst 33258 negative [Hoechst−], TMRE positive [TMRE+]) versus necrotic cells (quadrant Q1; Hoechst 33258 positive [Hoechst+], TMRE negative [TMRE−]) was not affected by the presence of 20 μM PPADS when the cells were exposed to CyaA-AC− (Fig. 6A). In contrast, the presence of 20 μM PPADS enhanced by a factor of 2 (P < 0.05) the number of macrophages staining as live cells upon incubation with CyaA-ΔN489 (Fig. 6B and D). Hence, purinergic signaling also potentiated the cytotoxic action of CyaA-ΔN489 on CD11b+ macrophages.

Fig 6.

The lysis of macrophages induced by CyaA-ΔN489 is partially inhibited by PPADS. J774A.1 cells (2 × 105/well) labeled with TMRE (40 nM) were preincubated for 10 min in the presence or absence of 20 μM PPADS. After 2 h of incubation with CyaA-AC− (75 nM) (A), CyaA-ΔN489 (1.75 nM) (B), or control buffer (C), the J774A.1 cells were stained with Hoechst 33258 (0.5 μg/ml). The live (Hoechst−, TMRE+) and necrotic (Hoechst+, TMRE−) cells were detected by FACS. (D) The results represent average values from three independent experiments. *, statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) from the untreated control.

N-terminal truncation significantly enhances the frequency of formation and conductance of CyaA pores.

The results presented above indicated that the CyaA-ΔN489 construct might form pores large enough to allow ATP leakage from cells to trigger purinergic signaling locally from outside the cell. The CyaA-ΔN489 pore properties were thus characterized in more detail by osmotic protection experiments on erythrocytes and measurements in artificial planar lipid bilayer membranes.

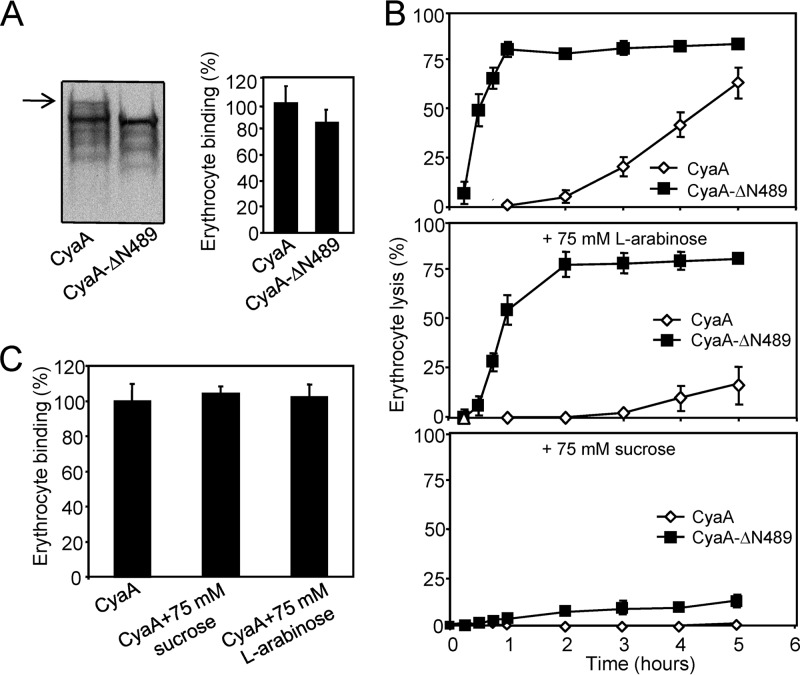

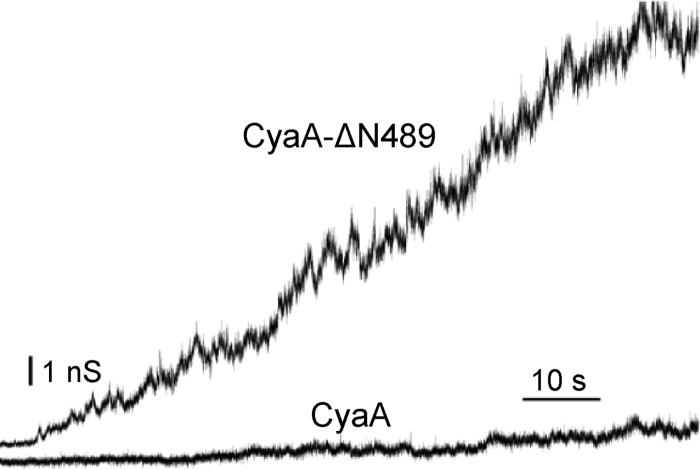

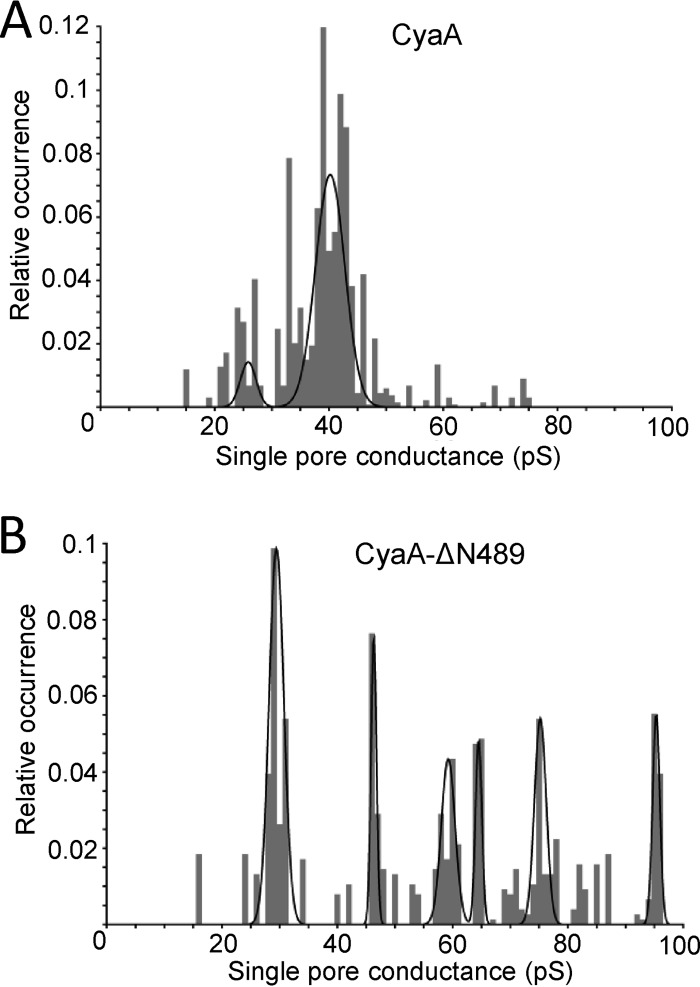

As shown in Fig. 7A, the truncated CyaA-ΔN489 associated with the membrane of erythrocytes with approximately the same efficacy as intact CyaA. Previously, Ehrmann and colleagues (32) used sugars like arabinose (estimated diameter of the sugar, 0.62 nm) and sucrose (estimated diameter of the sugar, 0.92 nm) to estimate the size of the CyaA pore in osmotic protection experiments. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 7, erythrocytes were only partially protected from lysis by CyaA or CyaA-ΔN489 in the presence of 75 mM arabinose (Fig. 7B). In contrast, a nearly complete protection from lysis was also observed in the presence of 75 mM sucrose with CyaA-ΔN489 (Fig. 7B), while toxin binding to cells was unaltered (Fig. 7C). It appears, hence, that CyaA-ΔN489 also formed pores of about 0.6 to 0.9 nm in diameter, like CyaA. As shown in Fig. 8, however, at an equal concentration (1 nM), the CyaA-ΔN489 protein exhibited an importantly greater overall pore-forming activity (membrane conductance) in planar lipid bilayer membranes than intact CyaA. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 9, the most frequent conductance unit observed in single pore recordings with CyaA was ∼38 pS, while a large dispersion of conductance unit sizes was observed for CyaA-ΔN489. Hence, the strongly enhanced specific cell-permeabilizing (hemolytic) potency of CyaA-ΔN489 resulted from its at least an order of magnitude enhanced propensity to form pores synergizing with a capacity to form pores of larger diameter (conductance).

Fig 7.

Erythrocyte lysis caused by CyaA-ΔN489 is protected by sucrose. (A) Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 108/ml) in TNC buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) containing 75 mM sucrose were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with CyaA or CyaA-ΔN489 (final concentration, 60 nM). Cells were washed three times in ice-cold TNC buffer containing 75 mM sucrose and further lysed in ice-cold 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4. Membranes were pelleted by centrifugation at 40,000 × g for 20 min and separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE. CyaA fragments were detected in Western blots using the 9D4 antibody recognizing the C-terminal RTX repeats of CyaA (left). The full-length CyaA is indicated by an arrow. Binding data were deduced from the integrated signal intensities of protein bands and are expressed as a percentage of CyaA binding to erythrocytes. The experiments were repeated three times, and the given values represent the average ± standard deviation (right). (B) Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 108/ml) in TNC buffer or in TNC buffer containing 75 mM l-arabinose or 75 mM sucrose were incubated at 37°C in the presence of CyaA or CyaA-ΔN489 (60 nM). Hemolytic activity was measured as the amount of released hemoglobin by photometric determination (A541). The results represent average values from three independent experiments. (C) Sheep erythrocytes (5 × 108/ml) in TNC buffer were incubated with CyaA (60 nM) at 37°C in the presence of 75 mM sucrose or 75 mM l-arabinose. After 30 min, aliquots of cell suspensions were washed repeatedly to remove unbound CyaA and used to determine the amount of cell-associated AC enzyme activity. The activity of CyaA in the absence of sugars was taken to be 100%. The results represent average values from two independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Fig 8.

N-terminal deletion significantly enhances the frequency of CyaA pore formation. The total electrical conductance of an asolectin–n-decane membrane in the presence of 1 nM intact CyaA or CyaA-ΔN489 is shown. The aqueous phase contained 1 M KCl, 10 mM Tris, and 2 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.4). The applied membrane potential was 70 mV; the temperature was 25°C.

Fig 9.

The conductance of a single CyaA pore is affected by N-terminal deletion. Single-pore conductance of CyaA (0.5 nM) (A) or CyaA-ΔN489 (0.01 nM) (B) was determined in 1 M KCl, 10 mM Tris, and 2 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.4) at membrane potentials of between 50 and 75 mV; the temperature was 25°C. The conductance histograms of at least 500 pore openings were fitted with the sum of Gaussian functions.

DISCUSSION

We report here that the involvement of purinergic amplification in the process of colloid osmotic lysis of cells by hemolytic RTX leukotoxins may differ depending on the size of the formed toxin pores. As could be expected, purinergic signaling of ATP leaking from cells appeared to be amplifying the cytolytic action of ApxIA, which forms pores of about 2.4 nm in diameter. It did not, however, accelerate the lysis of cells permeabilized by CyaA pores, which are only 0.6 to 0.8 nm wide and thus impermeant for ATP. Nevertheless, once the size and propensity of formation of CyaA pores were increased by removal of the cell-invasive AC enzyme domain together with an adjacent segment (residues 6 to 489), purinergic amplification was found to play a role also in the cytolytic action of the CyaA-ΔN489 construct.

Indeed, ATP concentrations inside cells range from 1 to 10 mM (58), and purinergic signaling is likely to be initiated early during the lytic process by ATP leaking from toxin-permeabilized cells. It appears to be involved in the mechanism of action of S. aureus alpha-toxin or that of E. coli HlyA, each of which induces hemolysis by forming 2.2- and >1-nm-wide pores in the erythrocyte membrane, respectively (38, 59, 60). The diameter of the pores formed by ApxIA in planar lipid bilayer membranes was previously estimated to be ∼2.4 nm (6). As, however, reported earlier for HlyA (5, 54) and corroborated here for ApxIA using planar lipid bilayers (Fig. 1D), the pores formed by bona fide RTX hemolysins may aggregate over time into larger conductance units or lesions in target cell membranes, in particular, at increased toxin concentrations (Fig. 1D). Besides mediating cation and water fluxes across the cell membrane, the >2-nm-wide ApxIA pores are hence likely to allow also leakage of the ∼1.5-nm-wide ATP molecules. We cannot, however, exclude the possibility that ATP also leaked from ApxIA-exposed cells through pannexin 1 channels. These were recently implicated in purinergic acceleration of cell lysis resulting from the action of other pore-forming toxins (37, 38, 40). Indeed, we also found here that two nonselective pannexin inhibitors, probenecid and carbenoxolone, antagonized ApxIA-induced hemolysis in a concentration-dependent manner (data not shown). However, such data need to be interpreted with caution, as the regulation of pannexin 1 channel activity is poorly understood and both inhibitors are known to affect also other membrane transporter functions (61–64).

Lysis of erythrocytes by ApxIA was further found to be antagonized by P2X inhibitors (200 μM PPADS or 2 μM BBG) that did not interfere with the activity and properties of toxin pores formed in planar bilayer membranes. It is, hence, plausible to propose that the leaking ATP would form a local gradient at the plasma membrane of permeabilized cells and that, through activation of P2X receptors and opening of cellular ion channels located in the vicinity of the pores, the ATP leakage would initiate an amplifying (positive) feedback loop of ApxIA-mediated cell permeabilization and lysis. Indeed, P2X7 receptors were previously shown to be activated by millimolar concentrations of ATP (65). Paradoxically, however, externally added ATP at a 1 or 5 mM concentration inhibited ApxIA-induced erythrocyte lysis (data not shown). This was most likely due to chelation of calcium ions that were present at a 2 mM concentration in order to maximize the activity of the RTX toxin. Moreover, calcium-complexed ATP was previously shown to be a P2X receptor antagonist (44, 66–68).

In contrast to ApxIA, CyaA forms frequently opening and closing (flipping) pores only 0.6 to 0.8 nm wide. The same opening propensity and conductance characteristics were, indeed, also repeatedly observed for pores formed by the truncated CyaA-ΔAC hemolysin construct that lacks only the cell-invasive AC domain located within the first 373 residues (4, 14, 48, 69, 70). When the deletion was extended up to residue 489 of CyaA, thus removing the sequence linking the cell-invasive AC domain to the pore-forming domain of CyaA, the resulting hyperhemolytic CyaA-ΔN489 construct was found to exhibit specific hemolytic potency at least an order of magnitude higher than that of intact CyaA (48). Recently, this linker segment between residues 400 and 500 of CyaA was shown to possess a lipid bilayer-interacting and destabilizing capacity (57). It is, hence, plausible to speculate that its presence may be imposing on CyaA a certain topology in the cellular membrane. This might be restricting the capacity of CyaA to form membrane pores by acting against or delaying the oligomerization of CyaA molecules into toxin pores. At the same time, such a topology might favor or enable AC domain translocation across the cell membrane. A similar role in the maintenance of equilibrium between the AC translocation precursor and the pore-forming conformer molecules has, indeed, been previously associated with the amphipathic transmembrane α helices predicted between residues 502 to 522 and residues 565 to 591 of CyaA (28, 30).

CyaA can penetrate with reduced efficacy across the membranes of a variety of cell types, including mammalian erythrocytes (13, 30, 71). The most sensitive primary targets of the toxin during natural infections by Bordetella, however, appear to be myeloid phagocytes, such as neutrophils, macrophages, or dendritic cells. These sentinels of the innate immune system indeed express high levels of the CyaA receptor CD11b/CD18, an αMβ2 integrin also known as complement receptor 3 (CR3) or Mac-1 (72, 73). Rapid elevation of intracellular cAMP concentrations by CyaA in such cells then causes a nearly instant ablation of their bactericidal capacities (74–78). The role of the pore-forming activity of CyaA in the immunosubversive activities of CyaA, however, remains largely unexplored. Recently, Dunne and coworkers showed that by eliciting K+ efflux from CD11b-expressing cells, the pore-forming activity of CyaA contributed to activation of the NALP3 inflammasome and thereby to induction of the innate interleukin-1β (IL-1β) response. This is likely contributing to the development of the pertussis syndrome, while at the late stages of infection, the IL-1β response would support the clearance of Bordetella bacteria (79). The relatively low hemolytic (pore-forming) potency associated with the CyaA molecule may thus represent an adaptation of the function of a pore-forming RTX hemolysin for the purpose of an immunomodulatory leukotoxin action in Bordetella infections. Restriction of harnessing of host proinflammatory responses through restriction of the pore-forming activity of CyaA and its balancing with the immunosuppressive cAMP signaling action of the toxin may then reflect an optimization of CyaA action toward maximal support of host colonization by the pathogen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants P302/12/0460 (to J.M.), P207/12/P890 (to R.F.), P302/11/0580 (to R.O.), P207/11/0717 (to L.B.), 13-14547S (to P.S.), and IAA500200914 (to P.S.) and received institutional support from RVO 61388971.

We thank H. Lukeova, S. Kozubova, and Iva Marsikova for excellent technical help. We acknowledge the assistance of Jan Polednak with black lipid membranes.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 September 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Linhartova I, Bumba L, Masin J, Basler M, Osicka R, Kamanova J, Prochazkova K, Adkins I, Hejnova-Holubova J, Sadilkova L, Morova J, Sebo P. 2010. RTX proteins: a highly diverse family secreted by a common mechanism. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34:1076–1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goebel W, Hedgpeth J. 1982. Cloning and functional characterization of the plasmid-encoded hemolysin determinant of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 151:1290–1298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welch RA. 1991. Pore-forming cytolysins of gram-negative bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 5:521–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benz R, Maier E, Ladant D, Ullmann A, Sebo P. 1994. Adenylate cyclase toxin (CyaA) of Bordetella pertussis. Evidence for the formation of small ion-permeable channels and comparison with HlyA of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 269:27231–27239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benz R, Schmid A, Wagner W, Goebel W. 1989. Pore formation by the Escherichia coli hemolysin: evidence for an association-dissociation equilibrium of the pore-forming aggregates. Infect. Immun. 57:887–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maier E, Reinhard N, Benz R, Frey J. 1996. Channel-forming activity and channel size of the RTX toxins ApxI, ApxII, and ApxIII of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 64:4415–4423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szabo G, Gray MC, Hewlett EL. 1994. Adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis produces ion conductance across artificial lipid bilayers in a calcium- and polarity-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 269:22496–22499 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodwin MS, Weiss AA. 1990. Adenylate cyclase toxin is critical for colonization and pertussis toxin is critical for lethal infection by Bordetella pertussis in infant mice. Infect. Immun. 58:3445–3447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khelef N, Sakamoto H, Guiso N. 1992. Both adenylate cyclase and hemolytic activities are required by Bordetella pertussis to initiate infection. Microb. Pathog. 12:227–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss AA, Hewlett EL, Myers GA, Falkow S. 1983. Tn5-induced mutations affecting virulence factors of Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 42:33–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glaser P, Ladant D, Sezer O, Pichot F, Ullmann A, Danchin A. 1988. The calmodulin-sensitive adenylate cyclase of Bordetella pertussis: cloning and expression in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2:19–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glaser P, Sakamoto H, Bellalou J, Ullmann A, Danchin A. 1988. Secretion of cyclolysin, the calmodulin-sensitive adenylate cyclase-haemolysin bifunctional protein of Bordetella pertussis. EMBO J. 7:3997–4004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellalou J, Sakamoto H, Ladant D, Geoffroy C, Ullmann A. 1990. Deletions affecting hemolytic and toxin activities of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase. Infect. Immun. 58:3242–3247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiser R, Masin J, Bumba L, Pospisilova E, Fayolle C, Basler M, Sadilkova L, Adkins I, Kamanova J, Cerny J, Konopasek I, Osicka R, Leclerc C, Sebo P. 2012. Calcium influx rescues adenylate cyclase-hemolysin from rapid cell membrane removal and enables phagocyte permeabilization by toxin pores. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002580. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gray M, Szabo G, Otero AS, Gray L, Hewlett E. 1998. Distinct mechanisms for K+ efflux, intoxication, and hemolysis by Bordetella pertussis AC toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 273:18260–18267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osickova A, Masin J, Fayolle C, Krusek J, Basler M, Pospisilova E, Leclerc C, Osicka R, Sebo P. 2010. Adenylate cyclase toxin translocates across target cell membrane without forming a pore. Mol. Microbiol. 75:1550–1562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basler M, Masin J, Osicka R, Sebo P. 2006. Pore-forming and enzymatic activities of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin synergize in promoting lysis of monocytes. Infect. Immun. 74:2207–2214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hewlett EL, Donato GM, Gray MC. 2006. Macrophage cytotoxicity produced by adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis: more than just making cyclic AMP! Mol. Microbiol. 59:447–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barry EM, Weiss AA, Ehrmann IE, Gray MC, Hewlett EL, Goodwin MS. 1991. Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin and hemolytic activities require a second gene, cyaC, for activation. J. Bacteriol. 173:720–726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basar T, Havlicek V, Bezouskova S, Hackett M, Sebo P. 2001. Acylation of lysine 983 is sufficient for toxin activity of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase. Substitutions of alanine 140 modulate acylation site selectivity of the toxin acyltransferase CyaC. J. Biol. Chem. 276:348–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basar T, Havlicek V, Bezouskova S, Halada P, Hackett M, Sebo P. 1999. The conserved lysine 860 in the additional fatty-acylation site of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase is crucial for toxin function independently of its acylation status. J. Biol. Chem. 274:10777–10783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hackett M, Guo L, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Hewlett EL. 1994. Internal lysine palmitoylation in adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis. Science 266:433–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hackett M, Walker CB, Guo L, Gray MC, Van Cuyk S, Ullmann A, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Hewlett EL, Sebo P. 1995. Hemolytic, but not cell-invasive activity, of adenylate cyclase toxin is selectively affected by differential fatty-acylation in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 270:20250–20253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masin J, Basler M, Knapp O, El-Azami-El-Idrissi M, Maier E, Konopasek I, Benz R, Leclerc C, Sebo P. 2005. Acylation of lysine 860 allows tight binding and cytotoxicity of Bordetella adenylate cyclase on CD11b-expressing cells. Biochemistry 44:12759–12766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumann U, Wu S, Flaherty KM, McKay DB. 1993. Three-dimensional structure of the alkaline protease of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a two-domain protein with a calcium binding parallel beta roll motif. EMBO J. 12:3357–3364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knapp O, Maier E, Polleichtner G, Masin J, Sebo P, Benz R. 2003. Channel formation in model membranes by the adenylate cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis: effect of calcium. Biochemistry 42:8077–8084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rose T, Sebo P, Bellalou J, Ladant D. 1995. Interaction of calcium with Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. Characterization of multiple calcium-binding sites and calcium-induced conformational changes. J. Biol. Chem. 270:26370–26376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osickova A, Osicka R, Maier E, Benz R, Sebo P. 1999. An amphipathic alpha-helix including glutamates 509 and 516 is crucial for membrane translocation of adenylate cyclase toxin and modulates formation and cation selectivity of its membrane channels. J. Biol. Chem. 274:37644–37650 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vojtova-Vodolanova J, Basler M, Osicka R, Knapp O, Maier E, Cerny J, Benada O, Benz R, Sebo P. 2009. Oligomerization is involved in pore formation by Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin. FASEB J. 23:2831–2843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basler M, Knapp O, Masin J, Fiser R, Maier E, Benz R, Sebo P, Osicka R. 2007. Segments crucial for membrane translocation and pore-forming activity of Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 282:12419–12429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Havlicek V, Higgins L, Chen W, Halada P, Sebo P, Sakamoto H, Hackett M. 2001. Mass spectrometric analysis of recombinant adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis strain 18323/pHSP9. J. Mass Spectrom. 36:384–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ehrmann IE, Gray MC, Gordon VM, Gray LS, Hewlett EL. 1991. Hemolytic activity of adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis. FEBS Lett. 278:79–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shope RE, White DC, Leidy G. 1964. Porcine contagious pleuropneumonia. II. Studies of the pathogenicity of the etiological agent, Hemophilus pleuropneumoniae. J. Exp. Med. 119:369–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frey J, Meier R, Gygi D, Nicolet J. 1991. Nucleotide sequence of the hemolysin I gene from Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 59:3026–3032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frey J, Nicolet J. 1990. Hemolysin patterns of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:232–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosendal S, Devenish J, MacInnes JI, Lumsden JH, Watson S, Xun H. 1988. Evaluation of heat-sensitive, neutrophil-toxic, and hemolytic activity of Haemophilus (Actinobacillus) pleuropneumoniae. Am. J. Vet. Res. 49:1053–1058 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Munksgaard PS, Vorup-Jensen T, Reinholdt J, Soderstrom CM, Poulsen K, Leipziger J, Praetorius HA, Skals M. 2012. Leukotoxin from Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans causes shrinkage and P2X receptor-dependent lysis of human erythrocytes. Cell. Microbiol. 14:1904–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skals M, Jorgensen NR, Leipziger J, Praetorius HA. 2009. Alpha-hemolysin from Escherichia coli uses endogenous amplification through P2X receptor activation to induce hemolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:4030–4035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fagerberg SK, Skals M, Leipziger J, Praetorius HA. 2013. P2X receptor-dependent erythrocyte damage by alpha-hemolysin from Escherichia coli triggers phagocytosis by THP-1 cells. Toxins (Basel) 5:472–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skals M, Leipziger J, Praetorius HA. 2011. Haemolysis induced by alpha-toxin from Staphylococcus aureus requires P2X receptor activation. Pflugers Arch. 462:669–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelk P, Abd H, Claesson R, Sandstrom G, Sjostedt A, Johansson A. 2011. Cellular and molecular response of human macrophages exposed to Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin. Cell Death Dis. 2:e126. 10.1038/cddis.2011.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bao L, Locovei S, Dahl G. 2004. Pannexin membrane channels are mechanosensitive conduits for ATP. FEBS Lett. 572:65–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pelegrin P, Surprenant A. 2009. The P2X(7) receptor-pannexin connection to dye uptake and IL-1beta release. Purinergic Signal. 5:129–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Virgilio F. 1995. The P2Z purinoceptor: an intriguing role in immunity, inflammation and cell death. Immunol. Today 16:524–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Surprenant A, Rassendren F, Kawashima E, North RA, Buell G. 1996. The cytolytic P2Z receptor for extracellular ATP identified as a P2X receptor (P2X7). Science 272:735–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller CM, Boulter NR, Fuller SJ, Zakrzewski AM, Lees MP, Saunders BM, Wiley JS, Smith NC. 2011. The role of the P2X(7) receptor in infectious diseases. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002212. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osicka R, Osickova A, Basar T, Guermonprez P, Rojas M, Leclerc C, Sebo P. 2000. Delivery of CD8(+) T-cell epitopes into major histocompatibility complex class I antigen presentation pathway by Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase: delineation of cell invasive structures and permissive insertion sites. Infect. Immun. 68:247–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gray MC, Lee SJ, Gray LS, Zaretzky FR, Otero AS, Szabo G, Hewlett EL. 2001. Translocation-specific conformation of adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis inhibits toxin-mediated hemolysis. J. Bacteriol. 183:5904–5910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Betsou F, Sebo P, Guiso N. 1993. CyaC-mediated activation is important not only for toxic but also for protective activities of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase-hemolysin. Infect. Immun. 61:3583–3589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sadilkova L, Nepereny J, Vrzal V, Sebo P, Osicka R. 2012. Type IV fimbrial subunit protein ApfA contributes to protection against porcine pleuropneumonia. Vet. Res. 43:2. 10.1186/1297-9716-43-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ladant D. 1988. Interaction of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase with calmodulin. Identification of two separated calmodulin-binding domains. J. Biol. Chem. 263:2612–2618 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iwaki M, Ullmann A, Sebo P. 1995. Identification by in vitro complementation of regions required for cell-invasive activity of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. Mol. Microbiol. 17:1015–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee SJ, Gray MC, Guo L, Sebo P, Hewlett EL. 1999. Epitope mapping of monoclonal antibodies against Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. Infect. Immun. 67:2090–2095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moayeri M, Welch RA. 1994. Effects of temperature, time, and toxin concentration on lesion formation by the Escherichia coli hemolysin. Infect. Immun. 62:4124–4134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harris RW, Sims PJ, Tweten RK. 1991. Evidence that Clostridium perfringens theta-toxin induces colloid-osmotic lysis of erythrocytes. Infect. Immun. 59:2499–2501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.North RA. 2002. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol. Rev. 82:1013–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karst JC, Barker R, Devi U, Swann MJ, Davi M, Roser SJ, Ladant D, Chenal A. 2012. Identification of a region that assists membrane insertion and translocation of the catalytic domain of Bordetella pertussis CyaA toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 287:9200–9212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beis I, Newsholme EA. 1975. The contents of adenine nucleotides, phosphagens and some glycolytic intermediates in resting muscles from vertebrates and invertebrates. Biochem. J. 152:23–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bhakdi S, Mackman N, Nicaud JM, Holland IB. 1986. Escherichia coli hemolysin may damage target cell membranes by generating transmembrane pores. Infect. Immun. 52:63–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bhakdi S, Tranum-Jensen J. 1991. Alpha-toxin of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Rev. 55:733–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gerard C, Boudier JA, Mauchamp J, Verrier B. 1990. Evidence for probenecid-sensitive organic anion transporters on polarized thyroid cells in culture. J. Cell. Physiol. 144:354–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hsyu PH, Gisclon LG, Hui AC, Giacomini KM. 1988. Interactions of organic anions with the organic cation transporter in renal BBMV. Am. J. Physiol. 254:F56–F61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perwitasari O, Yan X, Johnson S, White C, Brooks P, Tompkins SM, Tripp RA. 2013. Targeting organic anion transporter 3 with probenecid as a novel anti-influenza A virus strategy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:475–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tovar KR, Maher BJ, Westbrook GL. 2009. Direct actions of carbenoxolone on synaptic transmission and neuronal membrane properties. J. Neurophysiol. 102:974–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Donnelly-Roberts DL, Jarvis MF. 2007. Discovery of P2X7 receptor-selective antagonists offers new insights into P2X7 receptor function and indicates a role in chronic pain states. Br. J. Pharmacol. 151:571–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Di Virgilio F, Chiozzi P, Ferrari D, Falzoni S, Sanz JM, Morelli A, Torboli M, Bolognesi G, Baricordi OR. 2001. Nucleotide receptors: an emerging family of regulatory molecules in blood cells. Blood 97:587–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Evans RJ, Lewis C, Virginio C, Lundstrom K, Buell G, Surprenant A, North RA. 1996. Ionic permeability of, and divalent cation effects on, two ATP-gated cation channels (P2X receptors) expressed in mammalian cells. J. Physiol. 497(Pt 2):413–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakazawa K, Fujimori K, Takanaka A, Inoue K. 1990. An ATP-activated conductance in pheochromocytoma cells and its suppression by extracellular calcium. J. Physiol. 428:257–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sakamoto H, Bellalou J, Sebo P, Ladant D. 1992. Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. Structural and functional independence of the catalytic and hemolytic activities. J. Biol. Chem. 267:13598–13602 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Masin J, Konopasek I, Svobodova J, Sebo P. 2004. Different structural requirements for adenylate cyclase toxin interactions with erythrocyte and liposome membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1660:144–154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rogel A, Meller R, Hanski E. 1991. Adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis. The relationship between induction of cAMP and hemolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 266:3154–3161 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.El-Azami-El-Idrissi M, Bauche C, Loucka J, Osicka R, Sebo P, Ladant D, Leclerc C. 2003. Interaction of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase with CD11b/CD18: role of toxin acylation and identification of the main integrin interaction domain. J. Biol. Chem. 278:38514–38521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guermonprez P, Khelef N, Blouin E, Rieu P, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Guiso N, Ladant D, Leclerc C. 2001. The adenylate cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis binds to target cells via the alpha(M)beta(2) integrin (CD11b/CD18). J. Exp. Med. 193:1035–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Confer DL, Eaton JW. 1982. Phagocyte impotence caused by an invasive bacterial adenylate cyclase. Science 217:948–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Khelef N, Guiso N. 1995. Induction of macrophage apoptosis by Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase-hemolysin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 134:27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Khelef N, Zychlinsky A, Guiso N. 1993. Bordetella pertussis induces apoptosis in macrophages: role of adenylate cyclase-hemolysin. Infect. Immun. 61:4064–4071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Njamkepo E, Pinot F, Francois D, Guiso N, Polla BS, Bachelet M. 2000. Adaptive responses of human monocytes infected by Bordetella pertussis: the role of adenylate cyclase hemolysin. J. Cell. Physiol. 183:91–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weingart CL, Weiss AA. 2000. Bordetella pertussis virulence factors affect phagocytosis by human neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 68:1735–1739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dunne A, Ross PJ, Pospisilova E, Masin J, Meaney A, Sutton CE, Iwakura Y, Tschopp J, Sebo P, Mills KH. 2010. Inflammasome activation by adenylate cyclase toxin directs Th17 responses and protection against Bordetella pertussis. J. Immunol. 185:1711–1719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]