Abstract

Candidemia has become an important bloodstream infection that is frequently associated with high rates of mortality and morbidity, and its growing incidence is related to complex medical and surgical procedures. We conducted a multicenter study in five tertiary care teaching hospitals in Italy and Spain and evaluated the epidemiology, species distribution, antifungal susceptibilities, and outcomes of candidemia episodes. In the period of 2008 to 2010, 995 episodes of candidemia were identified in these hospitals. The overall incidence of candidemia was 1.55 cases per 1,000 admissions and remained stable during the 3-year analysis. Candida albicans was the leading agent of infection (58.4%), followed by Candida parapsilosis complex (19.5%), Candida tropicalis (9.3%), and Candida glabrata (8.3%). The majority of the candidemia episodes were found in the internal medicine department (49.6%), followed by the surgical ward, the intensive care unit (ICU), and the hemato-oncology ward. Out of 955 patients who were eligible for evaluation, 381 (39.9%) died within 30 days from the onset of candidemia. Important differences in the 30-day mortality rates were noted between institutions: the lowest mortality rate was in the Barcelona hospital, and the highest rate was in the Udine hospital (33.6% versus 51%, respectively; P = 0.0005). Overall, 5.1% of the 955 isolates tested were resistant or susceptible dose dependent (SDD) to fluconazole, with minor differences between the hospitals in Italy and Spain (5.7% versus 3.5%, respectively; P = 0.2). Higher MICs for caspofungin were found, especially with C. parapsilosis complex (MIC90, 1 μg/ml). Amphotericin B had the lowest MICs. This report shows that candidemia is a significant source of morbidity in Europe, causing a substantial burden of disease and mortality.

INTRODUCTION

Candida is an important cause of bloodstream infections (BSIs), leading to significant mortality and morbidity in health care settings. The incidence of candidemia is growing with the increasing complexity of surgical procedures, the existence of patient populations who are at higher risk of infection, and changes in patient demographics. The global incidence of candidemia increased 5-fold in the past 10 years, and Candida spp. are currently between the fourth and the sixth most common nosocomial bloodstream isolates found in studies done in the United States and Europe (1, 2). However, candidemia rates vary geographically. For example, an increasing incidence of candidemia in Iceland was reported for the period between 1980 and 1999 (3) but the same was not observed in Switzerland, where a national surveillance study showed that the incidence of candidemia had remained unchanged between 1991 and 2000 (2). Therefore, it seems that differences do exist in the epidemiology of candidemia between different countries, underscoring the need for continuous surveillance to monitor trends in the incidence, species distribution, and antifungal drug susceptibility profiles. The epidemiology of candidemia has been studied extensively in the United States, Europe, and some countries in South America (4–16).

Candidemia remains associated with high crude and attributable mortality rates and with increased costs of patient care and duration of hospitalization. The attributable mortality rates have been reported to range from 5% to 71%, and crude mortality rates have been reported to be as high as 81% (4–6, 14, 17–19). In terms of species of Candida, recently, a shift toward non-albicans species was reported by some authors, especially in hematological, transplanted, and intensive care unit (ICU) patients (12, 20, 21).

A reduced antifungal susceptibility in non-albicans Candida species and a correlation with routine fluconazole prophylactic use has been suggested (15). Intrinsic and emerging resistance to azoles represents a major challenge for empirical therapeutic and prophylactic strategies (5).

This study was performed to evaluate the contemporary epidemiology, species distribution, antifungal susceptibilities, and outcomes of candidemia episodes in five big teaching hospitals in Italy and Spain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted in five tertiary care teaching hospitals in Italy and Spain: (i) Trieste University Hospital (700 beds) in Trieste, Italy, (ii) Santa Maria Misericordia University Hospital (1,200 beds) in Udine, Italy, (iii) Policlinico Gemelli (1,500 beds) in Rome, Italy, (iv) Val d'Hebron Hospital (1,150 beds) in Barcelona, Spain, and (v) Virgen Del Rocio University Hospital (851 beds) in Seville, Spain. All patients admitted to these five hospitals who developed candidemia in the period of January 2008 to December 2010 were included in the study and prospectively followed. Patients with at least one positive blood culture for Candida spp. and a compatible clinical illness were identified through the microbiological laboratory database, and all information was recorded in an electronic database. For each patient, only the first episode of candidemia was recorded. Patients whose cultures grew >1 species of Candida were excluded from the analysis. Patients with candidemia were followed prospectively for 30 days or until their discharge from the hospital. Outcomes were recorded only for patients with ≥30 days of follow-up after the initial episode of candidemia.

During the study period, there were no changes in microbiological laboratory techniques in the five hospitals. Candida species were isolated from blood samples using the Bactec 860 system (Becton, Dickinson, Inc., Sparks, MD). The species were identified using the API ID 32C system (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) or the Vitek 2 system (bioMérieux). In the cases of inconclusive results obtained by both systems, isolates were definitively identified using supplemental tests, e.g., by the presence or absence of well-formed pseudohyphae on cornmeal-Tween 80 agar and growth at 42 to 45°C. The last test was also required to differentiate isolates of C. albicans from those of Candida dubliniensis. Antifungal susceptibility testing to amphotericin B, caspofungin, fluconazole, itraconazole, and voriconazole was performed using the Sensititre YeastOne colorimetric plate (Trek Diagnostic Systems, Cleveland, OH). MIC results were interpreted according to species-specific clinical breakpoints as established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) for amphotericin B, caspofungin, fluconazole, itraconazole (only with C. albicans), and voriconazole (22, 23).

The chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Differences between the groups were considered to be significant for variables yielding a P value of <0.05.

This study was approved by the local institutional review boards, and written patient consent was not required because of the observational nature of this study.

RESULTS

A total of 995 episodes of candidemia were identified during the study period (January 2008 to December 2010). The median patient age was 66.2 years old and 57% were males. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The majority of patients (93.1%) had one or more comorbidities at the time of candidemia diagnosis. Four hundred forty-one patients (46%) had undergone a surgical intervention, 285 (30%) had a solid tumor, 275 (28.8%) had cardiovascular diseases, 242 (25.3%) were diabetic, 60 (6.3%) had hematological malignancies, 33 (3.4%) received a solid organ transplantation, and 19 (2%) had human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. The overall incidence of candidemia was 1.55 cases per 1,000 admissions and remained stable during the 3-year analysis. As shown in Table 2, the incidences differed across hospitals, with the highest incidence in Rome (2.53 cases per 1,000 admissions), and the lowest in Udine (0.8 per 1,000 admissions).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 955 episodes of candidemia stratified by hospital

| Patient characteristic | Data by hospital (n)a |

Total (955) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U (126) | T (140) | R (456) | B (131) | S (102) | ||

| Age (mean [±SD]) (yr) | 64.4 (21.4) | 75.9 (16.1) | 65 (15) | 61 (19) | 59.1 (14) | 66.2 (13) |

| Male sex (n [%]) | 79 (63) | 73 (52) | 252 (55.2) | 82 (62.6) | 54 (52.9) | 486 (57) |

| Underlying disease/history (n [%]) | ||||||

| Surgery | 54 (43) | 27 (38) | 242 (53.2) | 68 (52) | 50 (49) | 441 (46) |

| Solid organ transplantation | 4 (3.2) | 0 | 19 (4.2) | 6 (4.5) | 4 (3.9) | 33 (3.4) |

| Hematologic malignancy | 12 (10) | 3 (4) | 24 (5.2) | 9 (6.9) | 12 (11.8) | 60 (6.3) |

| HIV | 3 (2.49) | 1 (1) | 1 (1.1) | 8 (6.1) | 6 (5.9) | 19 (2) |

| Solid tumor | 47 (37.3) | 39 (55) | 153 (33.5) | 11 (11.5) | 35 (34.3) | 285 (30) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 72 (57) | 12 (17) | 143 (31.3) | 30 (31) | 18 (17.6) | 275 (28.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 27 (21.5) | 26 (36) | 100 (21.9) | 68 (71.2) | 21 (20.6) | 242 (25.3) |

| Distribution of different Candida species (n [%/rank]) | ||||||

| C. albicans | 79 (63/1) | 77 (55/1) | 274 (60.1/1) | 78 (59.5/1) | 50 (48.1/1) | 558 (58.4/1) |

| C. parapsilosis complex | 22 (17.4/2) | 34 (24/2) | 87 (19.1/2) | 20 (15.3/2) | 23 (22.1/2) | 186 (19.5/2) |

| C. glabrata | 11 (8.7/3) | 14 (10/3) | 33 (7.2/4) | 14 (10.7/4) | 7 (6.7/4) | 79 (8.3/4) |

| C. tropicalis | 9 (7.1/4) | 6 (4/4) | 38 (8.3/3) | 15 (11.4/3) | 21 (20.2/3) | 89 (9.3/3) |

| Non-albicans Candida spp. | 5 (2.4/5) | 9 (7/5) | 24 (5.2/5) | 4 (3.11/5) | 3 (2.9/5) | 45 (4.7/5) |

U, Udine; T, Trieste; R, Rome; S, Seville; B, Barcelona.

Table 2.

Incidence of candidemia in the study period

| Hospital | Mean incidence (no. of episodes/1,000 admissions) by period: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2008–2010 | |

| Udine, Italy | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.8 |

| Trieste, Italy | 2.11 | 1.73 | 1.4 | 1.74 |

| Rome, Italy | 2.35 | 2.53 | 2.71 | 2.53 |

| Barcelona, Spain | 1.6 | 1.57 | 1.54 | 1.55 |

| Seville, Spain | 0.98 | 1.08 | 1.25 | 1.12 |

| Overall | 1.55 | 1.54 | 1.71 | 1.55 |

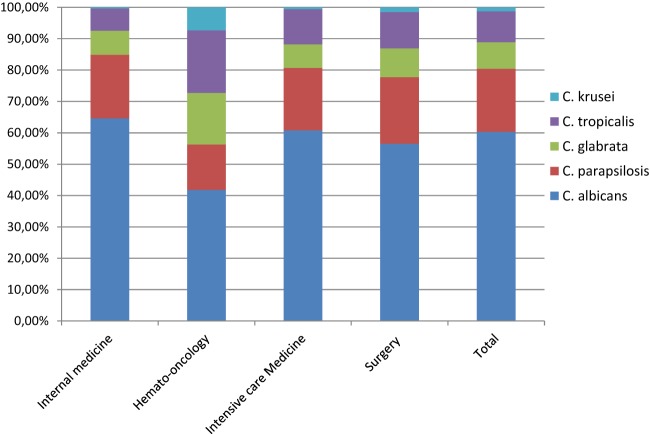

C. albicans was the leading cause of infection (58.4%), followed by C. parapsilosis complex (19.5%), C. tropicalis (9.3%), and C. glabrata (8.3%). C. albicans accounted for >50% of infections in all 3 Italian hospitals and in the hospital in Barcelona, Spain; only in Seville did non-albicans Candida species represent >50% of the isolates. The distribution of C. albicans and non-albicans Candida strains differed according to the patient population and risk factors, as shown in Fig. 1. In hemato-oncology patients, C. albicans was isolated in 41.8% of the cases, C. tropicalis in 20%, and C. glabrata in 16.4%; in the internal medicine ward, the ICU, and the surgery ward, C. albicans accounted for around 60% of the cases.

Fig 1.

Distribution (%) of Candida species according to underlying pathology or medical care.

The majority of the candidemia episodes were found in the internal medicine department (49.6%), followed by the surgery, ICU, and hemato-oncology wards (Table 3).

Table 3.

Thirty-day crude mortality rates and distributions of candidemia in hospital wards

| Distribution of candidemia episodes/mortality rate by hospital ward | Data by hospital (n)a |

Total (955) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U (126) | T (140) | R (456) | B (131) | S (102) | ||

| Overall 30-day mortality rate (n [%]) | 64 (51)b,c | 63 (45) | 178 (39.9)c | 44 (33.6)b | 32 (31.4)b | 381 (39.9) |

| Internal medicine | ||||||

| n (%) | 72 (57) | 95 (67.8) | 237 (56.9) | 42 (32) | 29 (28.4) | 475 (49.7) |

| 30-day mortality rate (n [%]) | 42 (52.3)b,c | 48 (51.5) | 108 (45.6) | 13 (33.3)b | 7 (24)b | 218 (46) |

| Hemato-oncology | ||||||

| n (%) | 12 (10) | 0 (0) | 24 (5.3) | 11 (8.4) | 11 (10.8) | 58 (6.1) |

| 30-day mortality rate (n [%]) | 8 (67)b | 0 (0) | 16 (66.6) | 4 (36.4)b | 5 (45.5) | 33 (56.9) |

| Intensive care | ||||||

| n (%) | 20 (16) | 22 (15.7) | 59 (12.9) | 42 (32) | 44 (43.1) | 187 (19.6) |

| 30-day mortality rate (n [%]) | 10 (50) | 9 (41) | 29 (49.1) | 20 (47.6) | 18 (41) | 86 (46) |

| General surgery | ||||||

| n (%) | 22 (17) | 23 (16.4) | 136 (29.8) | 36 (27.5) | 18 (17.6) | 235 (24.6) |

| 30-day mortality rate (n [%]) | 4 (18) | 6 (26) | 25 (18.4) | 7 (19.4) | 2 (11.1) | 44 (18.7) |

U, Udine; T, Trieste; R, Rome; S, Seville; B, Barcelona.

U versus B and S, P = 0.0005.

U versus R, P = 0.002.

Crude mortality rates stratified by hospital and ward are reported in Table 3. Out of 955 evaluable patients, 381 (39.9%) died within 30 days from the onset of candidemia. Important differences in the 30-day mortality rates were noted between institutions: the lowest mortality rate was in the hospital in Barcelona, and the highest rate was in the hospital in Udine (33.6% and 51%, respectively; P = 0.0005).

Regarding the crude mortality rates in the different units, patients in hemato-oncology wards had the highest mortality rate (56.9%), followed by patients in the ICU (46%) and in the internal medicine wards (45.9%). Patients in general surgery showed the lowest mortality rate of all the centers, with a mean rate of 18.7%.

Table 4 shows the in vitro activities of 5 systemically active antifungal agents tested against 955 BSI isolates of Candida spp. based on CLSI breakpoints (23). The rates of susceptibility to fluconazole were 98.6% for C. albicans and 97.3% for C. parapsilosis complex. Decreased susceptibility to fluconazole was mostly seen with C. glabrata (54.4%) and C. tropicalis (94.9%). Overall, 5.1% of the 955 isolates tested were resistant, intermediate, or susceptible dose dependent (SDD) to fluconazole. Higher MICs for caspofungin were found in C. albicans, C. glabrata, and especially in C. parapsilosis complex (MIC90, 1 μg/ml), which had 5 resistant strains (2.7%). Amphotericin B had the lowest MIC values. Some minor differences were found for fluconazole resistance in all Candida species between the hospitals in Italy and Spain (5.7% versus 3.5%; P = 0.2).

Table 4.

Frequency of antifungal resistance in Candida bloodstream infections according to CLSI breakpoints and MICs

| Species (n) | Antifungal agent | No. (%) of isolates resistant, intermediate, or SDD to the antifungal agent ina: |

Total no. of nonsusceptible strains (% SDD, intermediate, or resistant) | MIC50/MIC90 (μg/ml) of isolates in: |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U | T | B | R | S | U | T | B | R | S | |||

| C. albicans (558) | Amphotericin B | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.06/0.125 | 0.25/0.5 | 0.19/0.38 | 0.06/0.25 | 0.5/1 |

| Caspofungin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.06/0.12 | <0.06/0.12 | 0.047/0.125 | 0.03/0.125 | 0.03/0.06 | |

| Fluconazole | 2 (3.8) | 1 (1) | 0 | 5 (1.8) | 0 | 8 (1.4) | 0.25/1 | <0.12/0.5 | 0.25/1 | 0.125/2 | 0.25/0.5 | |

| Itraconazole | 2 (6) | 1 (1) | 18 (23.1) | 5 (1.8) | 0 | 26 (4.7) | 0.06/0.25 | <0.06/0.12 | 0.047/0.5 | 0.06/0.5 | 0.03/0.0795 | |

| Voriconazole | 2 (3.8) | 1 (1) | 0 | 4 (1.5) | 0 | 7 (1.2) | 0.008/0.06 | <0.06/<0.06 | 0.016/0.064 | 0.016/0.125 | 0.008/0.008 | |

| C. parapsilosis complex (186) | Amphotericin B | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.06/0.25 | 0.25/0.5 | 0.25/0.5 | 0.03/0.125 | 0.5/1 |

| Caspofungin | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 2 (10) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (4.3) | 5 (2.7) | 0.25/1 | 0.25/0.5 | 0.125/0.38 | 0.25/1 | 0.25/1 | |

| Fluconazole | 1 (4.5) | 1 (3) | 0 | 3 (3.4) | 0 | 5 (2.7) | 1/4 | 0.5/1 | 0.25/1.5 | 0.25/1 | 1/1 | |

| Itraconazole | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.06/0.25 | 0.06/0.25 | 0.032/0.25 | 0.06/0.25 | 0.06/0.125 | |

| Voriconazole | 2 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) | 0.023/0.125 | <0.06/<0.06 | 0.008/0.047 | 0.03/0.125 | 0.008/0.03 | |

| C. glabrata (79) | Amphotericin B | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.125/0.25 | 0.25/1 | 0.5/1 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.5/1 |

| Caspofungin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.09/0.125 | <0.06/0.12 | 0.064/0.19 | 0.016/0.06 | 0.06/0.86 | |

| Fluconazole | 1 (10) | 7 (50) | 16 (48.5) | 9 (27.3) | 3 (42.8) | 36 (45.6) | 4/8 | 8/16 | 3/16 | 4/128 | 16/128 | |

| Itraconazole | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.25/0.5 | 0.5/4 | 1/4 | 0.06/4 | 0.5/11.2 | |

| Voriconazole | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.045/0.25 | 0.5/1 | 0.094/0.19 | 0.06/8 | 0.25/2.8 | |

| C. tropicalis (89) | Amphotericin B | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.25/0.5 | 0.5/1 | 0.19/0.38 | 0.125/0.5 | 1/1 |

| Caspofungin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.120/0.125 | <0.06/0.12 | 0.047/0.125 | 0.06/0.25 | 0.06/0.125 | |

| Fluconazole | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 2 (5.3) | 1 (4.8) | 4 (4.5) | 1/2 | 0.5/4 | 0.75/2 | 0.25/2 | 1/2 | |

| Itraconazole | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.25/0.375 | 0.25/0.5 | 0.032/1 | 0.03/0.25 | 0.25/0.25 | |

| Voriconazole | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 2 (9.5) | 3 (3.4) | 0.015/0.06 | 0.06/0.5 | 0.047/0.19 | 0.03/0.5 | 0.06/0.125 | |

SDD, susceptible dose dependent; U, Udine; T, Trieste; R, Rome; S, Seville; B, Barcelona; NA, species-specific clinical breakpoint not available.

DISCUSSION

Several studies have shown a substantial increase in the incidence of candidemia in the past 2 decades. Our data show that in the 5 hospitals we analyzed, the incidence of candidemia has increased steadily in two of the institutions (Rome Catholic Hospital and Seville Hospital) and has remained stable in the other three. The mean rates are higher than those reported for centers in the Northern Hemisphere, including the United States (0.42 cases per 1,000 admissions) (24), Canada (0.45 per 1,000 admissions) (25), and some European countries (0.20 to 1.09 cases per 1,000 admissions) (26), but they are much higher than those reported in Finland (0.026 to 0.03 cases per 1,000 admissions [27]). The differences in candidemia rates between these countries may reflect differences in the representativeness and age distributions of the study populations, variations in health care practices, blood culture patterns, and antibiotic usage and resistance patterns.

Over the past 10 years, some studies have reported a shift in the etiology of candidemia. While C. albicans is still considered to be the most common species that causes candidemia, increasing rates of candidemia caused by C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis species complex, C. glabrata, and Candida krusei have been reported worldwide (28–31). The reasons for the emergence of non-albicans Candida species are not completely understood, but some medical conditions may consistently impact the risk of developing candidemia due to non-albicans Candida species: C. parapsilosis complex fungemia has been associated with vascular catheters and parenteral nutrition (28), C. tropicalis candidemia is associated with cancer and neutropenia (32), and C. krusei and C. glabrata fungemias are associated with previous exposure to azoles (15). The findings from our surveillance do not support these reports. We observed a predominance of C. albicans (around 60%) in candidemia infections. In our study, C. parapsilosis complex surpassed the other non-albicans Candida spp. to become the most common species isolated after C. albicans. Our series clearly supports the concept that C. parapsilosis complex accounts for the large majority of non-albicans Candida species in southern Europe. The high incidence of candidemia caused by C. parapsilosis complex has been previously reported in South American and Italian hospitals (11, 16). Of note, the frequencies of C. glabrata candidemia in these regions are lower than those reported in the Northern Hemisphere (33), and their frequency has been surpassed by that caused by C. tropicalis. We did not observe important differences across countries regarding the species distributions in the different departments. C. albicans dominated in our study in internal medicine, surgery, and ICU departments, while non-albicans Candida spp. occurred frequently among hemato-oncology patients, confirming previous observations (28). On the other hand, C. tropicalis candidemia was found more frequently in elderly patients, as reported elsewhere (34).

Interesting differences emerged in the profiles of patients with Candida BSIs between our data and those previously described elsewhere. Latin American and European studies have indicated that 56.5% and 44.4% of episodes of nosocomial fungemia cases, respectively, occurred in patients in the ICU(31, 34). In contrast, only 19.6% of episodes in our study occurred in ICU patients; this proportion was only a small amount lower than that which occurred in patients in the surgical units (24.6%). In our study, in contrast with those of other studies, an unusually large proportion (49.7%) of candidemia infections occurred among patients in a general internal medicine department, especially in the Italian hospitals. We hypothesize that this variety of patterns reflects differences in the organization and resourcing of health care delivery practices in various countries rather than significant differences in the characteristics of the populations studied.

Our proportion of fluconazole-resistant or SDD isolates (5.1%) was similar to the rates observed for European (6.3%) and North American (6.6%) hospital isolates (9, 35). Differences in susceptibilities to fluconazole were observed between Italy and Spain, with a higher proportion occurring in Italy, but the rates were lower than those recently reported in a tertiary-care Italian hospital (12). Voriconazole was the azole that exhibited the best in vitro antifungal activity. As reported by others (36), caspofungin demonstrated excellent activity for all the Candida species, except for C. parapsilosis complex, for which higher MICs were observed. The clinical relevance of these findings is unknown because the correlation between MICs and outcomes is still uncertain.

Retrospective cohort studies involving patients with candidemia and various underlying diseases have revealed worldwide crude and attributable mortality rates of 30% to 81% and 5% to 71%, respectively (10). The severity of candidemia is confirmed by the high crude mortality rate found in the European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) survey (38%) (37–39), as well as in Finland (35%) (40) and in the Barcelona area (44%) (8). In our series, patients with candidemia had a crude 30-day mortality rate of 39.9%. A major finding of the present study is the high mortality rate for candidemia in patients admitted to hemato-oncology and internal medicine wards compared with other wards (44.4% versus 35.4%; P = 0.002). Several factors may have impacted the outcome, e.g., the high APACHE II score, patient age, and the presence of multiple comorbidities. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that these factors played a major role in the poor outcomes in internal medicine wards compared to other wards. Thus, factors that may lead to intervention should be explored in future studies.

Certainly, the severity of a patient's underlying medical condition greatly influences the crude mortality rate in these patient populations; however, for patients in internal medicine wards, inappropriate therapy (consisting mostly of omission of initial empirical therapy and an inadequate choice of antifungals) might represent an important variable that has been associated with increased mortality rates (41).

Finally, the current study has several limitations that should be kept in mind when interpreting the results. All five sites we analyzed were located in teaching institutions, and our observations may not be generalizable to all patients with candidemia. Important intrahospital differences may also be observed in the larger hospitals. Another limitation of our study is that although 5 centers from 2 European countries participated, the results may not be representative of each country.

This report shows that candidemia is a significant source of morbidity in Italy and Spain, causing substantial burdens of disease, mortality, and likely high costs associated with care. Determining the factors associated with high rates of candidemia may lead to the identification of measures that can help prevent disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M.B. serves on scientific advisory boards for Pfizer Inc., MSD, Gilead, and Astellas Pharma, Inc., and has received funding for travel or speaker honoraria from Pfizer Inc., MSD, Gilead Sciences, and Astellas Pharma, Inc. M.T. has been a speaker or consultant for Gilead Sciences, MSD, and Pfizer. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This work was carried out as part of the regular work of the hospital and university departments.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 October 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent SM, Seifert H, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. 2004. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:309–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marchetti O, Bille J, Fluckiger U, Eggimann P, Ruef C, Garbino J, Calandra T, Glauser MP, Täuber MG, Pittet D, Fungal Infection Network of Switzerland 2004. Epidemiology of candidaemia in Swiss tertiary care hospitals: secular trends, 1991–2000. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:311–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asmundsdóttir LR, Erlendsdóttir H, Gottfredsson M. 2002. Increasing incidence of candidemia: results from a 20-year nationwide study in Iceland. J. Clin. Microbiol. 4:3489–3492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaoutis TE, Argon J, Chu J, Berlin JA, Walsh TJ, Feudtner C. 2005. The epidemiology and attributable outcomes of candidemia in adults and children hospitalized in the United States: a propensity analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:1232–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leroy O, Gangneux JP, Montravers P, Mira JP, Gouin F, Sollet JP, Carlet J, Reynes J, Rosenheim M, Regnier B, Lortholary O, AmarCand Study Group 2009. Epidemiology, management, and risk factors for death of invasive Candida infections in critical care: a multicenter, prospective, observational study in France (2005–2006). Crit. Care Med. 37:1612–1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horn DL, Neofytos D, Anaissie EJ, Fishman JA, Steinbach WJ, Olyaei AJ, Marr KA, Pfaller MA, Chang CH, Webster KM. 2009. Epidemiology and outcomes of candidemia in 2019 patients: data from the prospective antifungal therapy alliance registry. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:1695–1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tortorano AM, Kibbler C, Peman J, Bernhardt H, Klingspor L, Grillot R. 2006. Candidaemia in Europe: epidemiology and resistance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 27:359–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almirante B, Rodríguez D, Park BJ, Cuenca-Estrella M, Planes AM, Almela M, Mensa J, Sanchez F, Ayats J, Gimenez M, Saballs P, Fridkin SK, Morgan J, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Warnock DW, Pahissa A, Barcelona Candidemia Project Study Group 2005. Epidemiology and predictors of mortality in cases of Candida bloodstream infection: results from population-based surveillance, Barcelona, Spain, from 2002 to 2003. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1829–1835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cisterna R, Ezpeleta G, Telleria O, Spanish Candidemia Surveillance Group 2010. Nationwide sentinel surveillance of bloodstream Candida infections in 40 tertiary care hospitals in Spain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:4200–4206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 10.Garbino J, Kolarova L, Rohner P, Lew D, Pichna P, Pittet D. 2002. Secular trends of candidemia over 12 years in adult patients at a tertiary care hospital. Medicine (Baltimore) 81:425–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luzzati R, Amalfitano G, Lazzarini L, Soldani F, Bellino S, Solbiati M, Danzi MC, Vento S, Todeschini G, Vivenza C, Concia E. 2000. Nosocomial candidemia in non-neutropenic patients at an Italian tertiary care hospital. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:602–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bassetti M, Righi E, Costa A, Fasce R, Molinari MP, Rosso R, Pallavicini FB, Viscoli C. 2006. Epidemiological trends in nosocomial candidemia in intensive care. BMC Infect. Dis. 6:21. 10.1186/1471-2334-6-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bassetti M, Trecarichi EM, Righi E, Sanguinetti M, Bisio F, Posteraro B, Soro O, Cauda R, Viscoli C, Tumbarello M. 2007. Incidence, risk factors, and predictors of outcome of candidemia. Survey in 2 Italian university hospitals. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 58:325–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bassetti M, Taramasso L, Nicco E, Molinari MP, Mussap M, Viscoli C. 2011. Epidemiology, species distribution, antifungal susceptibility and outcome of nosocomial candidemia in a tertiary care hospital in Italy. PLoS One 6(9):e24198. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bassetti M, Ansaldi F, Nicolini L, Malfatto E, Molinari MP, Mussap M, Rebesco B, Bobbio Pallavicini F, Icardi G, Viscoli C. 2009. Incidence of candidaemia and relationship with fluconazole use in an intensive care unit. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:625–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colombo AL, Nucci M, Salomao R, Branchini ML, Richtmann R, Derossi A, Wey SB. 1999. High rate of non-albicans candidemia in Brazilian tertiary care hospitals. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 34:281–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kett DH, Azoulay E, Echeverria PM, Vincent JL, Extended Prevalence of Infection in ICU Study (EPIC II) Group of Investigators 2011. Candida bloodstream infections in intensive care units: analysis of the extended prevalence of infection in intensive care unit study. Crit. Care Med. 39:665–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Rosa FG, Trecarichi EM, Montrucchio C, Losito AR, Raviolo S, Posteraro B, Corcione S, Di Giambenedetto S, Fossati L, Sanguinetti M, Serra R, Cauda R, Di Perri G, Tumbarello M. 2012. Mortality in patients with early- or late-onset candidaemia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68:927–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viscoli C, Girmenia C, Marinus A, Collette L, Martino P, Vandercam B, Doyen C, Lebeau B, Spence D, Krcmery V, De Pauw B, Meunier F. 1999. Candidemia in cancer patients: a prospective, multicenter surveillance study by the Invasive Fungal Infection Group (IFIG) of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Clin. Infect Dis. 28:1071–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen MH, Peacock JE, Jr, Morris AJ, Tanner DC, Nguyen ML, Snydman DR, Wagener MM, Rinaldi MG, Yu VL. 1996. The changing face of candidemia: emergence of non-Candida albicans species and antifungal resistance. Am. J. Med. 100:617–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rocco TR, Reinsert SE, Simms HH. 2000. Effects of fluconazole administration in critically ill patients: analysis of bacterial and fungal resistance. Arch. Surg. 135:160–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2012. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; 4th informational supplement. CLSI M27-S4 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. 2012. Progress in antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida spp. by use of Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute broth microdilution methods, 2010 to 2012. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:2846–2856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Kollef MH. 2008. Secular trends in candidemia-related hospitalization in the United States, 2000–2005. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 29:978–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macphail GL, Taylor GD, Buchanan-Chell M, Ross C, Wilson S, Kureishi A. 2002. Epidemiology, treatment and outcome of candidemia: a five-year review at three Canadian hospitals. Mycoses 45:141–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richet H, Roux P, Des Champs C, Esnault Y, Andremont A, French Candidemia Study Group 2002. Candidemia in French hospitals: incidence rates and characteristics. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 8:405–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poikonen E, Lyytikäinen O, Anttila VJ, Koivula I, Lumio J, Kotilainen P, Syrjälä H, Ruutu P. 2010. Secular trend in candidemia and the use of fluconazole in Finland, 2004–2007. BMC Infect. Dis. 10:312. 10.1186/1471-2334-10-312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark TA, Slavinski SA, Morgan J, Lott T, Arthington-Skaggs BA, Brandt ME, Webb RM, Currier M, Flowers RH, Fridkin SK, Hajjeh RA. 2004. Epidemiologic and molecular characterization of an outbreak of Candida parapsilosis bloodstream infections in a community hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4468–4472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin MY, Carmeli Y, Zumsteg J, Flores EL, Tolentino J, Sreeramoju P, Weber SG. 2005. Prior antimicrobial therapy and risk for hospital-acquired Candida glabrata and Candida krusei fungemia: a case-case-control study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4555–4560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pappas PG, Rex JH, Lee J, Hamill RJ, Larsen RA, Powderly W, Kauffman CA, Hyslop N, Mangino JE, Chapman S, Horowitz HW, Edwards JE, Dismukes WE, NIAID Mycoses Study Group 2009. A prospective observational study of candidemia: epidemiology, therapy, and influences on mortality in hospitalized adult and pediatric patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37:634–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfaller MA, Messer SA, Moet GJ, Jones RN, Castanheira M. 2011. Candida bloodstream infections: comparison of species distribution and resistance to echinocandin and azole antifungal agents in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and non-ICU settings in the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2008–2009). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 38:65–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Komshian SV, Uwaydah AK, Sobel JD, Crane LR. 1989. Fungemia caused by Candida species and Torulopsis glabrata in the hospitalized patient: frequency, characteristics, and evaluation of factors influencing outcome. Rev. Infect. Dis. 11:379–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lockhart SR, Pham CD, Gade L, Iqbal N, Scheel CM, Cleveland AA, Whitney AM, Noble-Wang J, Chiller TM, Park BJ, Litvintseva AP, Brandt ME. 2013. Preliminary laboratory report of fungal infections associated with contaminated methylprednisolone injections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51:2654–2661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nucci M, Queiroz-Telles F, Alvarado-Matute T, Tiraboschi IN, Cortes J, Zurita J, Guzman-Blanco M, Santolaya ME, Thompson L, Sifuentes-Osornio J, Echevarria JI, Colombo AL, Latin American Invasive Mycosis Network 2013. Epidemiology of candidemia in Latin America: a laboratory-based survey. PLoS One 8(3):e59373. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Messer SA, Moet GJ, Kirby JT, Jones RN. 2009. Activity of contemporary antifungal agents, including the novel echinocandin anidulafungin, tested against Candida spp., Cryptococcus spp., and Aspergillus spp.: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2006 to 2007). J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1942–1946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfaller MA, Castanheira M, Messer SA, Moet GJ, Jones RN. 2011. Echinocandin and triazole antifungal susceptibility profiles for Candida spp., Cryptococcus neoformans, and Aspergillus fumigatus: application of new CLSI clinical breakpoints and epidemiologic cutoff values to characterize resistance in the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2009). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 69:45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doern L, Messer SA, Brueggemann AB, Coffman SL, Doern GV, Herwaldt A, Pfaller MA. 2002. Epidemiology of candidemia: 3-year results from the Emerging Infections and the Epidemiology of Iowa Organisms study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1298–1302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dóczi I, Dósa E, Hajdú E, Nagy E. 2002. Aetiology and antifungal susceptibility of yeast bloodstream infections in a Hungarian university hospital between 1996 and 2000. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:677–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fraser VJ, Jones M, Dunkel J, Storfer S, Medoff G, Dunagan WC. 1992. Candidemia in a tertiary care hospital: epidemiology, risk factors, and predictors of mortality. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:414–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poikonen E, Lyytikainen O, Anttila VJ, Ruutu P. 2003. Candidemia in Finland, 1995–1999. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:985–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bassetti M, Molinari MP, Mussap M, Viscoli C, Righi E. 2013. Candidaemia in internal medicine departments: the burden of a rising problem. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 19:E281–E284. 10.1111/1469-0691.12155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]