Abstract

Splenic abscesses caused by Streptococcus bovis are rarely reported in the literature and are mainly seen in patients with endocarditis and associated colonic neoplasia/carcinoma. We report the first case of splenic abscess caused by Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus (Streptococcus bovis biotype II/2) as presentation of a pancreatic cancer.

CASE REPORT

A 55-year-old man was referred to the Department of Infection and Critical Care Medicine, Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital University of Medical Sciences (Beijing, China), because of persistent fever over 40°C for 9 days with shaking and chills. He also complained of general fatigue and loss of appetite but had no abdominal pain, vomiting, weight loss, or other symptoms. His previous medical history was unremarkable. On physical examination, fever was present (39.3°C), lung fields were clear, heart sounds were regular without murmur, and the abdomen was soft, nondistended, and with no palpable mass.

Initial laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 16.7 × 109/liter with 83.6% neutrophils. A stool occult blood test was negative. Inflammatory tests showed the following results: a C-reactive protein level of >160 mg/dl (normal, 0.0 to 0.8 mg/dl) and a procalcitonin (PCT) level of 2.32 ng/ml (reference range, 0 to 0.05 ng/ml). Tumor markers CA125 and CA19-9 increased greatly: CA19-9 to >1,200 U/ml (reference range, 0 to 37 U/ml) and CA125 to 247.9 U/ml (reference range, 0 to 37 U/ml). However, the carcinoembryonic antigen level was normal. The results of the pancreatic amylase test and creatinine, glucose, and liver function tests were all within normal limits. Blood cultures were collected.

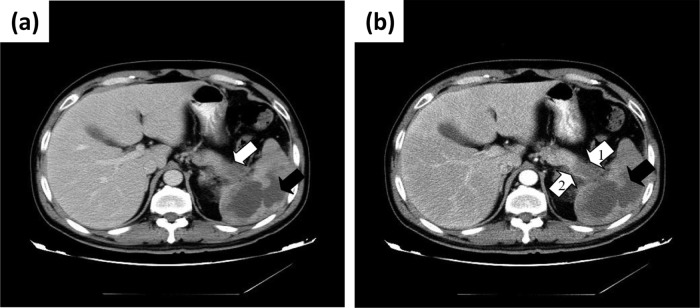

A chest radiograph was unremarkable; however, a chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed lobar consolidation in the left lower lobe with associated pleural effusion. An abdominal ultrasound exam demonstrated a hypoechoic area in the spleen with an unclear margin, suggestive of a splenic abscess. An enhanced abdominal CT further revealed a nonenhancing hypodense lesion in the tail of the pancreas with invasion into the spleen and multiple hypodense lesions in the liver, along with the splenic lesion (Fig. 1a and b). The splenic artery was slender without obvious filling of the contrast agent. These findings were also demonstrated on magnetic resonance imaging studies. Together, the imaging studies, constitutional presentation, and laboratory test results suggested a working diagnosis of an occult pancreatic cancer and a splenic abscess.

Fig 1.

(a) CT scan (portal phase) image of a hypodense area that invaded hilum of spleen, in the tail of pancreas (white arrow), and an irregular hypodense area with an unclear margin in the spleen (black arrow). (b) CT scan (arterial phase) image of nonenhancing hypodense area that invaded hilum of spleen, in the tail of pancreas (white arrow 1), and an irregular nonenhancing hypodense area in the spleen (black arrow). The splenic artery is slender (white arrow 2).

Empirical antibiotic therapy with intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam and azithromycin was started. However, the patient's fever persisted, up to 40.5°C, which required a switch of antimicrobials to imipenem-cilastatin and vancomycin in order to broaden the coverage. On the 4th hospitalization day, an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided percutaneous drainage of the splenic abscess was performed, which aspirated 50 ml odorous pus, leading to a decrease of the patient's temperature. The aspirate was stained and cultured. Numerous white blood cells were found, and the Gram-positive coccus was isolated and identified as Streptococcus gallolyticus by Vitek 2 compact GP systems (bioMérieux, France). On the 5th hospitalization day, the isolate from initial blood culture was also identified as S. gallolyticus. Subsequently on the 7th day, the patient underwent EUS-guided percutaneous drainage again, 100 ml of pus was obtained, and the culture was the same S. gallolyticus isolate. The isolate was tested by a microdilution method according to the published CLSI standard (1) and proved sensitive to vancomycin and cefotaxime and resistant to erythromycin, clindamycin, and levofloxacin. Treatment with intravenous (i.v.) vancomycin was continued. The isolate was further identified to the subspecies level by partial sequencing of 16S rRNA gene (Institute for Biological Product Control, National Institutes for Food and Drug Control, Beijing, China). Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted with the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen). The 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR with the universal primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′). The PCR amplification program was followed by 95°C (30 s), 55°C (30 s), and 72°C (90 s) for 30 cycles and a final extension step at 72°C (10 min). The products were purified and submitted for nucleotide sequencing (Shanghai Songan Biological Engineering Technology & Services Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The 16S rRNA gene sequences were compared by using the BLASTN program at the U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) and showed 100% (1,414/1,414 bp) homology with S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus (GenBank accession no. EU163502).

Considering the association between Streptococcus bovis/S. gallolyticus bacteremia and colonic carcinoma, the patient underwent colonoscopy, but no significant lesions were found. The surgical service was consulted, but eventually the patient refused an operation for the pancreatic cancer. After treatment with antibiotics and EUS-guided PCD, the culture of drainage turned negative, and the patient was discharged 3 weeks later in stable condition.

The patient was followed up after discharge. He was advised to go to the Beijing Cancer Hospital, where the same diagnosis of pancreatic tail cancer was made. However, the patient also refused an operation or chemotherapy. His condition deteriorated in the next several months, including development of abdominal symptoms, ascites, and other symptoms. He died 6 months later.

Splenic abscess is a rare clinical entity, occurring in 0.14% to 0.7% of autopsy studies (2). It generally occurs in patients with neoplasia, immunodeficiency, trauma, metastatic infection, splenic infarct, or diabetes (3). Splenic abscess is often misdiagnosed, because its signs and symptoms are nonspecific. Sarr and Zuidema suggested the triad of fever, left upper quadrant pain, and a tender mass for diagnosis of splenic abscess (4). However, fever was the only symptom observed in our patient.

The pathogenesis of splenic abscess is multifactorial, including metastatic infection, contiguous infection, noninfectious splenic embolism with ischemia, and secondary infection, trauma, and immunodeficiency (5). Additionally, the metastatic infection of the spleen is often caused by a different primary site of infection, especially endocarditis. In our case, the patient's echocardiography was normal, which essentially ruled out endocarditis as the source of the splenic abscess. Instead, the occult pancreatic cancer was the probable cause of the large abscess, which caused persistent fever with positive blood culture.

A variety of microorganisms have been isolated from splenic abscesses (6, 7). The frequently isolated aerobic and facultative isolates were Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, S. bovis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus. The isolated anaerobes were Peptostreptococcus spp., Bacteroides spp., Fusobacterium spp., and Clostridium spp. (6, 7). The organisms isolated often reflect the underlying pathogenesis: i.e., S. aureus and S. bovis were associated with endocarditis, K. pneumoniae with respiratory infection or liver abscess, E. coli with urinary tract and abdominal infection, and Bacteroides spp. and Clostridium spp. with abdominal infection (6). Casess of splenic abscess caused by S. bovis are rare and usually due to septic emboli from endocarditis in patients with colonic cancer (8, 9). To our knowledge, our case is the first report of a splenic abscess in association of pancreatic cancer along with subspecies identification.

S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus belongs to the group D streptococci and was previously recognized as S. bovis biotype II/2. S. bovis is found as part of the human gastrointestinal microbiota in 5 to 16% of individuals (10). Using the scheme proposed by Schlegel et al. (11), on the basis of DNA studies, there are two Streptococcus species of principal interest: S. gallolyticus, with the subspecies gallolyticus (formerly biotype I), pasteurianus (formerly biotype II/2), and macedonicus; and S. infantarius (formerly biotype II/1), with the subspecies coli and infantarius. Each biotype has somewhat different pathogenicity. S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus (biotype I) has been associated frequently with underlying colorectal cancer (12). S. infantarius (biotype II/1) could be associated with noncolonic cancers (13). S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus (biotype II/2) has been reported recently to cause to cause neonatal and adult meningitis (14–16) and bacteremia and peritonitis (17, 18) but not solid organ infections.

The association between S. bovis bacteremia and pancreatic carcinoma was first reported in 1980 (19) and has been reported in only a few case reports to date (13, 19–22), but molecular genetic characterization of strains was not described in the studies. One of them described the association with S. infantarius (13), but there is no reported case associated with S. pasteurianus. Our case of S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus bacteremia with splenic abscess and underlying pancreatic cancer reminds clinicians that malignancy might be a potential feature to search for.

Splenic abscess as a complication of pancreatic cancer has been reported in only a few cases to date (23–27). This may be due to the location of the tumor in the pancreas. As we all know, pancreatic carcinoma occurs most commonly in the head, and as such, usually presents with obstructive jaundice. Conversely, the least common location for pancreatic carcinoma, as seen in our patient, is in the tail. These cancers tend to present later and are larger at presentation than pancreatic head tumors, with signs of advanced disease, such as contiguous organ extension, vascular invasion, and distant metastases (24), and splenic involvement can include infarction, abscess, intrasplenic pseudocysts, and hemorrhage (28).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge financial support from the Capital Medical Development Fund sponsored by the Beijing Municipal Bureau of Traditional Chinese Medicine (SF-2009-I-11) and the Scientific Research Fund of the Beijing Friendship Hospital.

We thank Qiang Ye, Institute for Biological Product Control, National Institutes for Food and Drug Control, for subtype determination of Streptococcus gallolyticus.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 September 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2011. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 21st informational supplement. Document M100-S21, CLSI, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso Cohen MA, Galera MJ, Ruiz M, Puig la Calle J, Jr, Ruis X, Artigas V, Puig la Calle J. 1990. Splenic abscess. World J. Surg. 14:513–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng KK, Lee TY, Wan YL, Tan CF, Lui KW, Cheung YC, Cheng YF. 2002. Splenic abscess: diagnosis and management. Hepatogastroenterology 49:567–571 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarr MG, Zuidema GD. 1982. Splenic abscess—presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Surgery 92:480–485 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelken N, Ignatius J, Skinner M, Christensen N. 1987. Changing clinical spectrum of splenic abscess. Am. J. Surg. 154:27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brook I, Frazier EH. 1998. Microbiology of liver and spleen abscesses. J. Med. Microbiol. 47:1075–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee WS, Choi ST, Kim KK. 2011. Splenic abscess: a single institution study and review of the literature. Yonsei Med. J. 52:288–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belinkie SA, Narayanan NC, Russell JC, Becker DR. 1983. Splenic abscess associated with Streptococcus bovis septicemia and neoplastic lesions of the colon. Dis. Colon Rectum 26:823–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Genta PR, Carneiro L, Genta EN. 1998. Streptococcus bovis bacteremia: unusual complications. South. Med. J. 91:1167–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noble CJ. 1978. Carriage of group D streptococci in the human bowel. J. Clin. Pathol. 31:1182–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlegel L, Grimont F, Ageron E, Grimont PA, Bouvet A. 2003. Reappraisal of the taxonomy of the Streptococcus bovis/Streptococcus equinus complex and related species: description of Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus subsp. nov., Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. macedonicus subsp. nov. and Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus subsp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:631–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devriese LA, Vandamme P, Pot B, Vanrobaeys M, Kersters K, Haesebrouck F. 1998. Differentiation between Streptococcus gallolyticus strains of human clinical and veterinary origins and Streptococcus bovis strains from the intestinal tracts of ruminants. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3520–3523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corredoira J, Alonson MP, Coira A, Varela J. 2008. Association between Streptococcus infantarius (formerly Streptococcus bovis II/1) bacteremia and noncolonic cancer. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:1570 (Letter.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sturt AS, Yang L, Sandhu K, Pei Z, Cassai N, Blaser MJ. 2010. Streptococcus gallolyticus subspecies pasteurianus (biotype II/2), a newly reported cause of adult meningitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:2247–2249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith AH, Sra HK, Bawa S, Stevens R. 2010. Streptococcus bovis meningitis and hemorrhoids. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:2654–2655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Onoyama S, Ogata R, Wada A, Saito M, Okada K, Harada T. 2009. Neonatal bacterial meningitis caused by Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus. J. Med. Microbiol. 58:1252–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romero B, Morosini MI, Loza E, Rodríguez-Baños M, Navas E, Cantón R, Campo RD. 2011. Reidentification of Streptococcus bovis isolates causing bacteremia according to the new taxonomy criteria: still an issue? J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:3228–3233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akahane T, Takahashi K, Matsumoto T, Kawakami Y. 2009. A case of peritonitis due to Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 83:56–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrington P, Finkelman D, Balart L, Hines C, Jr, Ferrante W. 1980. Streptococcus bovis septicemia and pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann. Intern. Med. 92:441 (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gold JS, Bayar S, Salem RR. 2004. Association of Streptococcus bovis bacteremia with colonic neoplasia and extracolonic malignancy. Arch. Surg. 139:760–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robson SC, Cannan C. 1989. Streptococcus bovis bacteremia and endocarditis at Groote Schuur Hospital. S. Afr. Med. J. 75:597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzlez-Quintela A, Martinez-Rey C, Castroagudin JF, Rajo-Iglesias MC, Dominguez-Santalla MJ. 2001. Prevalence of liver disease in patients with Streptococcus bovis bacteraemia. J. Infect. 42:116–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cavuoti D, Fogli M, Quinton R, Gander RM, Southern PM. 2002. Splenic abscess with Vibrio cholerae masking pancreatic cancer. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 43:311–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lastrapes RG, Parker JR, Kida M. 1995. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma presenting as a splenic abscess: case report and diagnostic approach. J. Okla. State Med. Assoc. 88:333–336 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nano J, Welch JP. 1997. Splenic abscess associated with pancreatic cancer: report of a case. Surgery 121:237–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cipe G, Gen.ç Cakmak VA, Kuterdem E. 2011. Pancreatic cancer complicated by splenic infarction and abscess. Chirurgia (Bucur) 106:523–525 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ida A, Nagashima I, Inaba T, Tanaka F, Imamura T, Okinaga K. 2003. A case of splenic abscess associated with pancreatic tail cancer. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi 100:599–603 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fishman EK, Soyer P, Bliss DF, Bluemke DA, Devine N. 1995. Splenic involvement in pancreatitis: spectrum of CT findings. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 164:631–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]