Abstract

Hypoxia is a feature of solid tumors. Most tumors are at least partially hypoxic. This hypoxic environment plays a critical role in promoting resistance to anticancer drugs. PHLPP, a novel family of Ser/Thr protein phosphatases, functions as a tumor suppressor in colon cancers. Here, we show that the expression of both PHLPP isoforms is negatively regulated by hypoxia/anoxia in colon cancer cells. Interestingly, a hypoxia-induced decrease of PHLPP expression is attenuated by knocking down HIF1α but not HIF2α. Whereas the mRNA levels of PHLPP are not significantly altered by oxygen deprivation, the reduction of PHLPP expression is caused by decreased protein translation downstream of mTOR and increased degradation. Specifically, hypoxia-induced downregulation of PHLPP is partially rescued in TSC2 or 4E-BP1 knockdown cells as the result of elevated mTOR activity and protein synthesis. Moreover, oxygen deprivation destabilizes PHLPP protein by decreasing the expression of USP46, a deubiquitinase of PHLPP. Functionally, downregulation of PHLPP contributes to hypoxia-induced chemoresistance in colon cancer cells. Taken together, we have identified hypoxia as a novel mechanism by which PHLPP is downregulated in colon cancer, and the expression of PHLPP may serve as a biomarker for better understanding of chemoresistance in cancer treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Hypoxia is a condition commonly occurring in most solid tumors. Numerous studies have demonstrated that hypoxia plays a pivotal role in tumor progression and metastasis and is often associated with increased malignancy and poor prognosis (1, 2). Serving as the primary modulators of hypoxic stress, hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) are rapidly induced in response to oxygen deprivation to regulate the expression of genes that facilitate adaptation to hypoxic conditions (2, 3). The HIF transcription factors are heterodimers consisting of an O2-sensitive α subunit and a stable β subunit. There are three isoforms of mammalian HIFα, of which HIF1α and HIF2α are the most structurally similar and best characterized (3). Under normoxic condition, HIFs are modified at two conserved proline residues by prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins (PHDs; consisting of PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3). The modified HIFs are subsequently recognized and ubiquitinated by an E3 ligase, the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) protein, resulting in the degradation of HIF proteins via the proteasome pathway. Under hypoxic conditions, the hydroxylase activity of PHDs is inhibited, and stabilized HIF transcription factors can translocate to the nucleus and regulate the transcription of hypoxia-associated genes (3–5).

Previous studies have shown that hypoxia inhibits mTOR and cap-dependent protein translation via a TSC2-dependent mechanism upon the induction of REDD1 (6, 7). mTOR is an evolutionarily conserved serine/threonine protein kinase that functions in two distinct complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2, in cells. mTORC1 serves as a nutrient and energy sensor by controlling protein translation through phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and S6K1 (8). The inhibition of mTORC1-dependent protein translation has been suggested to affect cellular tolerance to hypoxia; however, it remains elusive how hypoxia-induced downregulation of translation contributes to tumor progression. Furthermore, cancer cells exposed to hypoxic conditions are notoriously known to be more resistant to apoptosis induced by radiation and chemotherapy drugs, and a variety of mechanisms have been suggested to affect the treatment sensitivity (9–12). Thus, a better understanding of hypoxia-mediated chemoresistance is needed in order to treat cancer cells more effectively.

PHLPP (PH domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase) belongs to a novel family of Ser/Thr protein phosphatases consisting of two isoforms, namely, PHLPP1 and PHLPP2. As a direct regulator of several critical protein kinases, including Akt, protein kinase C (PKC), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and MST1, PHLPP plays a critical role in maintaining the balance of signaling and homeostasis in cells (13–16). Recently, an increasing numbers of studies have revealed that loss of PHLPP expression is highly associated with tumor progression in both human cancers and mouse models, thus further confirming the role of PHLPP as a tumor suppressor (17–20). Our previous studies have shown that PHLPP is degraded via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, and the turnover of PHLPP proteins is mediated by the E3 ubiquitin ligase β-TrCP (21). Conversely, the expression of PHLPP is stabilized by the deubiquitinase USP46, which rescues PHLPP from proteasomal degradation by removing ubiquitin chains from PHLPP directly (22). In this study, we investigated the role of hypoxia in negatively controlling the expression of PHLPP in colon cancer cells. Our results revealed the functional importance of hypoxia-mediated downregulation of PHLPP in regulating chemosensitivity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and reagents.

Antibodies against PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 were purchased from Bethyl Laboratory. The HIF1α antibody was obtained from BD Biosciences, and antibodies against HIF-2α and ubiquitin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The carbonic anhydrase IX (CA9) antibody was from Novus Biologicals, the β-TrCP antibody was from Invitrogen, and the USP46 and γ-tubulin antibodies were from Sigma-Aldrich. The antibodies against 4E-BP1, TSC2, phospho-S6K (T389), S6K1, and PHD2 were from Cell Signaling. The antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) Affinity Matrix of rat IgG1 was purchased from Roche Applied Science. The expression plasmids for HA-tagged PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 have been described in previous studies (18, 23, 24). The Myc-tagged USP46 was constructed by subcloning of the USP46 coding sequence into the pcDNA4-Myc/His vector.

Cell culture and treatment.

Human colon cancer cell lines SW480 and HCT116 were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Cellgro) and McCoy's 5A medium, respectively. All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Stable SW480 cells overexpressing HA-PHLPP1 or HA-PHLPP2 were generated as described previously (25). Cells were routinely cultured in a humidified incubator at 37°C in 95% air–5% CO2. The hypoxic condition was achieved by placing cells in a sealed hypoxia incubator chamber (Stemcell Technologies, Inc.) filled with 5% CO2 and 95% N2. Alternatively, cells were grown in a humidified incubator maintained with 5% CO2 and 1% O2. To induce hypoxia chemically, cells were treated with desferrioxamine (DFO) or CoCl2 for the times shown in the figure legends.

Lentivirus-mediated delivery of shRNA.

The stable PHLPP1, PHLPP2, 4E-BP1, and TSC2 knockdown HCT116 and SW480 cells were generated in previous studies using lentivirus carrying specific short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting sequences for each gene (18, 25, 26). To generate stable knockdown cells for HIF1α, HIF2α, and PHD2, the shRNA for each gene was constructed in pLKO.1-puro vector and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The shRNA targeting sequences are as follows: for HIF1α, 5′-CCAGTTATGATTGTGAAGTTA-3′ and 5′-CGGCGAAGTAAAGAATCTGAA-3′; for HIF2α, 5′-CGACCTGAAGATTGAAGTGAT-3′ and 5′-GCGCAAATGTACCCAATGATA-3′; and for PHD2, 5′-ACGCCACTGTAACGGGAAGCT-3′ and 5′-TGCACGACACCGGGAAGTTCA-3′. The lentivirus-mediated delivery of shRNA and selection for stable knockdown cells were carried out as previously described (18).

Immunoblotting.

Cultured cells were harvested and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 20 mM NaF, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 200 mM benzamidine, 40 mg ml−1 leupeptin, 200 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]), and the detergent-solubilized cell lysates were obtained after centrifugation for 5 min at 16,000 × g at 4°C. Equal amounts of cell lysates as determined by Bradford assays were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting analysis. The density of enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) signals was obtained and quantified using a FluoChem digital imaging system (Alpha Innotech).

Analysis of ubiquitination.

To examine the ubiquitination of PHLPP in cells, stable SW480 cells expressing vector or HA-PHLPP1 or HA-PHLPP2 cultured cells were exposed to normoxia or hypoxia for 6 h and lysed in buffer A (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, 200 μM benzamidine, 40 μg ml−1 leupeptin, 200 μM PMSF, and 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide). The detergent-solubilized cell lysates were incubated with the anti-HA Affinity Matrix at 4°C for overnight. The beads were washed three times with buffer B (buffer A plus 250 mM NaCl) and once with buffer A. The immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using ubiquitin and HA antibodies.

Cell viability assay.

Equal numbers of HCT116 cells (2,000 cells/well) were seeded onto 96-well plates and allowed to attach overnight. Cells were then treated with different concentrations of paclitaxel or oxaliplatin and cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for an additional 48 h. MTS [3,4-(5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxy phenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium salt] assays were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Promega). The absorbance was measured as the optical density at 492 nm (OD492) using a microplate reader.

Real-time PCR.

Total RNA was isolated with an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) from SW480 and HCT116 cells following specific treatment. Equal amounts of RNA were used as templates for the synthesis of cDNA using a High Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Real-time PCR was performed using PHLPP1-, PHLPP2-, or USP46-specific probes using a StepOne real-time PCR system (Applied Biosysems). All values were normalized to the level of β-actin.

RESULTS

Expression of PHLPP is downregulated under hypoxic conditions in colon cancer cells.

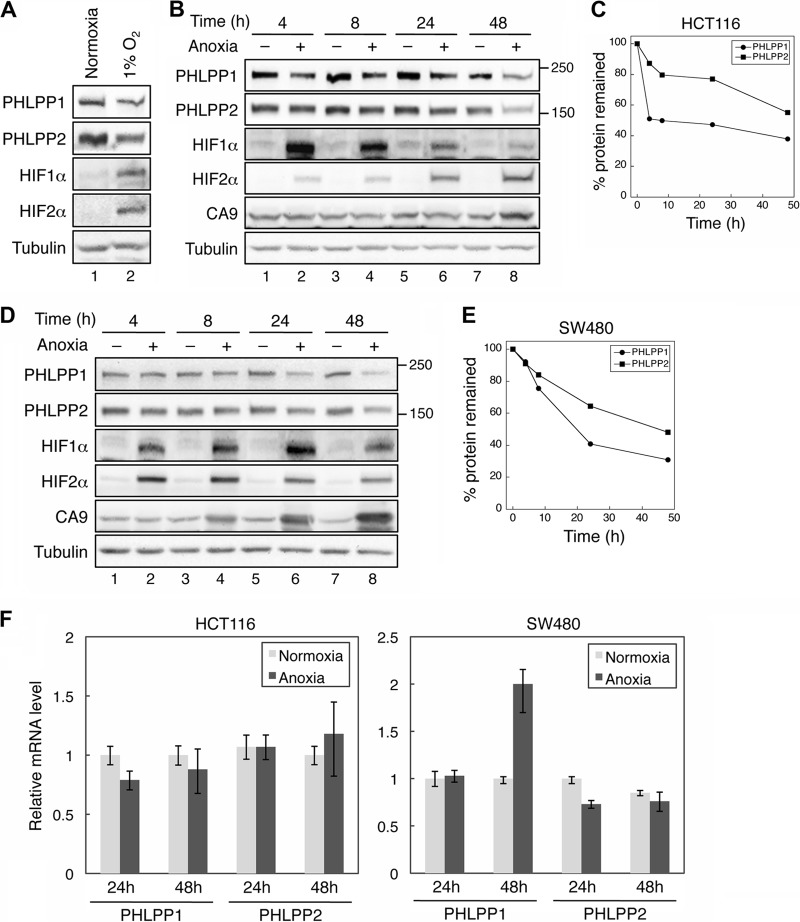

Since hypoxia and expression of HIFs have been linked to the development and progression of colon cancer, we first investigated the effect of oxygen deprivation on the expression of PHLPP isoforms in colon cancer cells. As 50 to 60% of solid tumors are estimated to contain areas of hypoxic and/or anoxic tissues (27), we performed the experiments under both 1% O2 and anoxic conditions (<0.1% O2). As shown in Fig. 1, the expression of both PHLPP isoforms was markedly reduced in HCT116 cells grown in 1% O2 after a 24-h exposure, whereas the expression levels of HIF1α and HIF2α were induced (Fig. 1A). Similarly, anoxic treatment resulted in a decrease in PHLPP expression over the period of 4 to 48 h in both HCT116 and SW480 cells (Fig. 1B to E). The levels of both PHLPP isoforms began to decrease as early as 4 h after exposure to anoxia; at the end of 48 h, the total expression of PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 was reduced by approximately 60% and 40%, respectively, compared to cells grown under normoxic conditions (Fig. 1C and E). As a positive control, the expression levels of hypoxia markers HIF1α, HIF2α, and carbonic anhydrase IX (CA9; a target of hypoxia) were induced under anoxic conditions (Fig. 1B and D). Since 1% O2 and anoxia had similar effects on HIF induction and PHLPP expression, the subsequent experiments were usually performed under one condition and confirmed under the other condition. To further determine if hypoxia-induced downregulation of PHLPP expression is regulated at the transcriptional level, total RNAs were isolated from HCT116 and SW480 cells exposed to normoxic or anoxic conditions for 24 and 48 h, and real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis was performed using probes specific for the PHLPP1 or PHLPP2 gene. The results revealed that the mRNA levels of PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 were not decreased in both cell lines treated with anoxia (Fig. 1F). Interestingly, the level of PHLPP1 mRNA was increased in HCT116 cells after 48 h in anoxia. However, since the expression of PHLPP1 proteins was decreased at this time point, this increase of PHLPP1 mRNA was likely unrelated to hypoxia-mediated downregulation of PHLPP1.

Fig 1.

The protein but not mRNA expression of PHLPP isoforms is downregulated under hypoxia. (A) Hypoxia treatment decreases PHLPP expression. HCT116 cells cultured under normoxic condition or 1% O2 were analyzed for the expression of PHLPP1, PHLPP2, HIF1α, and HIF2α. Tubulin was used as the loading control throughout this study. (B to E) Time course of anoxia-induced PHLPP downregulation in colon cancer cells. SW480 (B and C) and HCT116 (D and E) cells were cultured under normoxic (−) or anoxic (+) conditions for the indicated times. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed for the expression of PHLPP1, PHLPP2, HIF1α, HIF2α, and CA9 using corresponding antibodies. Representative Western blots are shown in panels B and D. Note that the major isoform of PHLPP1 expressed in colon cancer cells used in this study is PHLPP1β, which has a molecular mass of ∼190 kDa. The molecular mass of PHLPP2 is ∼160 kDa. The relative expression levels of PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 were quantified by normalizing the amount of PHLPP to tubulin and are expressed graphically in panels C and E. (F) The mRNA expression of PHLPP was not decreased in anoxia-treated cells. SW480 and HCT116 cells were exposed to anoxia for 24 or 48 h, and total RNA was extracted. Real-time RT-PCR analysis was performed using probes specific for the human PHLPP1 or PHLPP2 gene. Each experimental point was done in triplicates, and the graphs represent the means ± standard deviations. (n = 3).

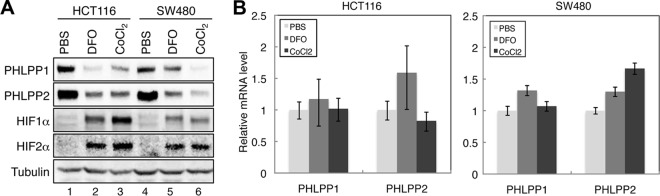

To confirm the effect of hypoxia on the downregulation of PHLPP protein expression, SW480 and HCT116 cells were treated with hypoxia-mimetic agents, DFO and CoCl2, for 24 h. Consistent with results shown in Fig. 1, the expression levels of both PHLPP isoforms were largely decreased by the DFO and CoCl2 treatments (Fig. 2A). The effect of DFO and CoCl2 on inducing the expression of HIF1α and HIF2α was also confirmed in both cell lines (Fig. 2A). In contrast, treating cells with DFO or CoCl2 had no effect on the levels of PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 mRNAs, as indicated by the RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 2B). Taken together, these results demonstrated that hypoxia promotes downregulation of PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 proteins via a posttranscriptional mechanism in colon cancer cells.

Fig 2.

Hypoxia-mimetic agents reduce the protein expression of both PHLPP isoforms. (A) HCT116 and SW480 cells were treated with PBS, DFO (100 μM), or CoCl2 (100 μM) for 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed for the expression of PHLPP1, PHLPP2, HIF1α, HIF2α, and tubulin using corresponding antibodies. (B) Total RNAs were isolated from cells as treated as described for panel A. Real-time RT-PCR analysis was performed using probes specific for the human PHLPP1 or PHLPP2 gene. Each experimental point was done in triplicates, and the graphs represent the means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

Hypoxia-induced downregulation of PHLPP is HIF1α but not HIF2α dependent.

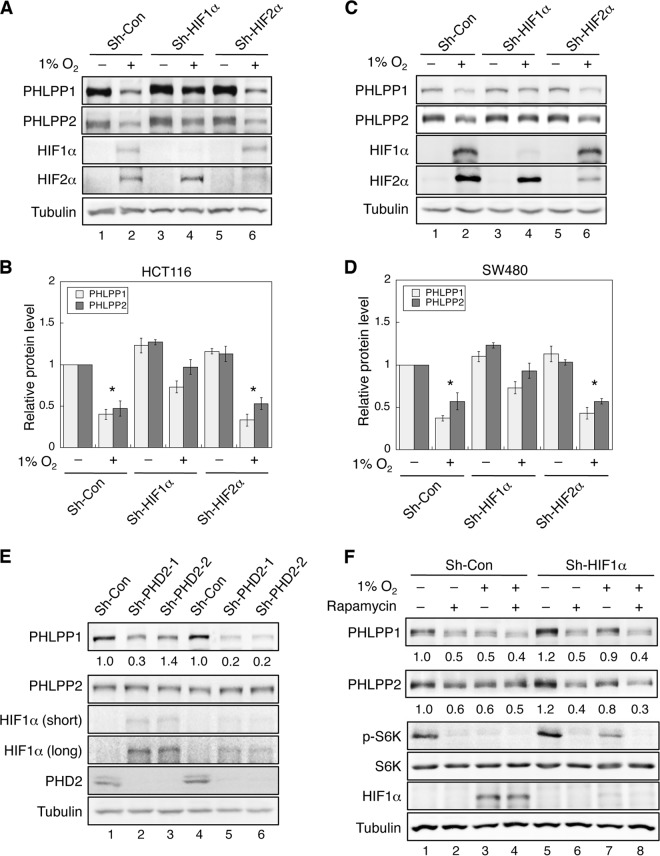

Both HIF1α and HIF2α are known to be the central regulators in mediating hypoxia-induced effects; however, they may play distinct roles in responding to hypoxia, depending on cancer cell types (28, 29). To determine which HIF isoform is involved in downregulating the expression of PHLPP under hypoxic/anoxic conditions in colon cancer cells, stable knockdown cells were generated using lentivirus-based shRNA targeting HIF1α or HIF2α. In stable HIF1α or HIF2α knockdown cells, silencing of either HIF isoform was effectively achieved, as shown by reduced induction of HIF1α or HIF2α upon hypoxia treatment (Fig. 3A and C). More importantly, knockdown of HIF1α partially rescued the expression of PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 under hypoxic conditions in both HCT116 and SW480 cells, whereas knockdown of HIF2α had no effect on hypoxia-induced downregulation of PHLPP isoforms (Fig. 3A to D). To rule out potential off-target effects, two other shRNA targeting constructs were used to knock down HIF1α and HIF2α in HCT116 and SW480 cells. Consistently, silencing endogenous HIF1α expression partially rescued anoxia-mediated downregulation of PHLPP1 and PHLPP2, whereas knockdown of HIF2α had no effect (data not shown). These results suggested that hypoxia-induced decrease of PHLPP expression is mediated by HIF1α rather than HIF2α.

Fig 3.

Hypoxia-induced downregulation of PHLPP expression is HIF1α but not HIF2α dependent. (A to D) Knockdown of HIF1α but not HIF2α partially prevents hypoxia-induced downregulation of PHLPP. Stable control and HIF1α or HIF2α knockdown HCT116 (A and B) and SW480 cells (C and D) were exposed to normoxia (−) or hypoxia (1% O2; +) for 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed for the expression of PHLPP1, PHLPP2, HIF1α, HIF2α, and tubulin using corresponding antibodies. Results shown in panels A and C were quantified by normalizing the expression of PHLPP isoforms to the level of tubulin and summarized in panels B and D. The relative expression of PHLPP for the control cells under normoxia was set to 1, and cells under all other conditions were compared accordingly. Data shown in graphs represent the means ± standard errors of the means (n = 3; *, P < 0.05, by a two-sample t test). (E) Knockdown of PHD2 results in an increase in HIF1α and a decrease in PHLPP expression in colon cancer cells. Cell lysates prepared from stable control and PHD2 knockdown HCT116 (lanes 1 to 3) and SW480 (lanes 4 to 6) cells were analyzed for the expression of PHLPP1, PHLPP2, HIF1α, PHD2, and tubulin using Western blotting. Two different PHD2 shRNA targeting constructs (sh-PHD2-1 and sh-PHD2-2) were used. The relative expression of PHLPP isoforms was quantified by normalizing ECL signals generated by the PHLPP antibodies to that of tubulin, and this number for the control cells was set to 1. The expression of PHLPP in PHD2 knockdown cells was normalized to the control cells, and the numbers are indicated below the PHLPP panels. (F) Stable control and HIF1α knockdown SW480 cells (Sh-Con and Sh-HIF1a, respectively) were exposed to normoxia (−) or hypoxia (1% O2; +) for 24 h in the presence or absence of rapamycin (20 nM). Cell lysates were analyzed for the expression of PHLPP1, PHLPP2, phospho-S6K (T389 site; p-S6K), total S6K, HIF1α, and tubulin using Western blotting. The expression of PHLPP was normalized to that of the control cells under normoxia, and the numbers are indicated below the PHLPP panels.

Since the expression of HIFs is known to be controlled by the intracellular oxygen sensors PHDs, especially PHD2 (also known as EGLN1), we next determined if knockdown of PHD2 affects PHLPP expression. Stable PHD2 knockdown HCT116 and SW480 cells were generated using two different lentiviral shRNA targeting constructs, and the expression of PHD2 was reduced by ∼90% in both cell lines (Fig. 3E). A small increase in HIF1α expression was observed under normoxic conditions in PHD2 knockdown cells; however, prolonged exposure was needed to better detect the expression HIF1α by Western blotting (Fig. 3E). The relative HIF1α expression in PHD2 knockdown cells was less than 10% of that observed in cells under hypoxic conditions. In addition, HIF2α remained undetectable by Western blotting (data not shown). Despite the small increase in HIF1α expression, the protein level of PHLPP1 decreased in PHD2 knockdown cells (Fig. 3E). However, the expression of PHLPP2 was largely unchanged. This is likely because the induction of HIF1α is considerably lower in PHD2 knockdown cells and because PHLPP2 is a more stable protein than PHLPP1. Moreover, RT-PCR analyses did not detect any decrease in mRNA expression of PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 in either HIF1α or PHD2 knockdown cells compared to control cells, suggesting posttranscriptional regulation (data not shown). Collectively, we identified a functional link between the induction of HIF1α (by hypoxia or by loss of PHD2 expression) and downregulation of PHLPP expression in colon cancer cells.

Hypoxia downregulates PHLPP expression through the inhibition of mTOR-mediated protein translation.

Our results shown above indicate that hypoxia negatively regulated PHLPP expression via a posttranscriptional mechanism as mRNA levels of PHLPP were not affected by hypoxia or the expression of HIF1α. Previously, we have identified both PHLPP isoforms as translational targets of mTORC1 (25). To begin to address whether hypoxia reduces PHLPP expression by inhibiting mTOR-dependent translation, control and HIF1α knockdown cells were treated with rapamycin and subsequently exposed to normoxic or hypoxic conditions. The activity of mTORC1 was inhibited upon rapamycin or hypoxia treatment as indicated by decreased phosphorylation of S6K1. Consistent with our previous findings (25), treating cells with rapamycin reduced the expression of both PHLPPs under normoxic conditions, and the extent of PHLPP decrease was similar to that observed in cells exposed to hypoxia (Fig. 3F). Interestingly, rapamycin treatment reversed the effect of HIF1α knockdown on preserving PHLPP expression under hypoxia (Fig. 3F), suggesting that inhibition of mTOR-dependent translation is likely one of the mechanisms underlying hypoxia-induced downregulation of PHLPP.

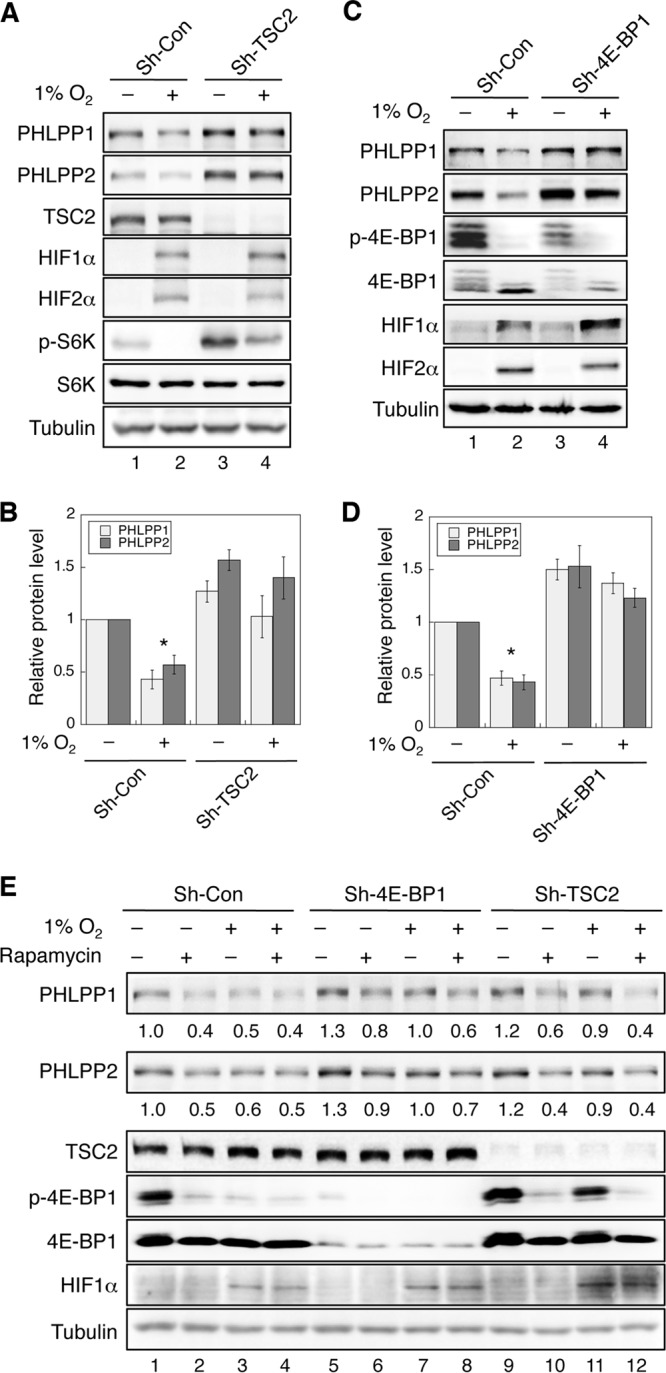

It has been shown previously that hypoxia-induced inhibition of mTORC1 requires TSC2, an upstream negative regulator of mTORC1 (6, 7). To further determine if hypoxia-induced downregulation of PHLPP is mediated through inhibition of mTORC1, we generated stable TSC2 knockdown HCT116 cells and subjected cells to normoxic and hypoxic conditions. In TSC2 knockdown cells, mTOR activity was enhanced, as shown by increased phosphorylation of S6K under normoxic conditions, and hypoxia-induced decrease of mTOR activity was partially prevented (Fig. 4A). Consequently, the expression of both PHLPP isoforms was largely rescued in hypoxia-treated cells (Fig. 4B). To further confirm that decreased PHLPP expression under hypoxia is controlled at the translational level, we examined the effect on the expression of PHLPP of silencing 4E-BP1, a negative regulator of translation downstream of mTORC1. To this end, we assessed whether knockdown of 4E-BP1 can rescue PHLPP expression in cells exposed to hypoxia. Indeed, hypoxia-induced downregulation of both PHLPP isoforms was markedly attenuated in HCT116 cells depleted of 4E-BP1 expression (Fig. 4C and D). Similar results were obtained in stable 4E-BP1 knockdown SW480 cells (data not shown). In addition, knockdown of either TSC2 or 4E-BP1 resulted in an increase in PHLPP expression under normoxic conditions, confirming the notion that the translation of PHLPP isoforms is positively controlled by the mTOR pathway (Fig. 4A and C) (25). Furthermore, the mRNA levels of both PHLPP isoforms were not significantly altered in TSC2 and 4E-BP1 knockdown cells that were cultured under normoxia or hypoxia (data not shown). Finally, we determined the effect of rapamycin on PHLPP expression in TSC2 and 4E-BP1 knockdown cells under hypoxia. Consistent with our results shown in Fig. 3F, rapamycin treatment or hypoxia reduced the expression of PHLPP in control cells as the result of mTORC1 inhibition. Since 4E-BP1 functions downstream of mTOR, rapamycin was less effective at blocking PHLPP expression under either normoxic or hypoxic conditions in 4E-BP1 knockdown cells than control cells (Fig. 4E). On the other hand, although silencing TSC2 alleviated hypoxia-induced downregulation of PHLPP, rapamycin was able to decrease PHLPP expression in TSC2 knockdown cells under hypoxia, likely because rapamycin inhibits mTOR-mediated translation downstream of TSC2 (Fig. 4E). Taken together, these results indicate that hypoxia reduces PHLPP expression, at least partially, by inhibiting mTOR-mediated translation of PHLPP proteins.

Fig 4.

Hypoxia inhibits mTOR-mediated protein translation of PHLPP isoforms. (A) Knockdown of TSC2 rescues PHLPP expression under hypoxia. Stable control and TSC2 knockdown HCT116 cells were exposed to normoxia (−) or hypoxia (1% O2; +) for 24 h. The expression levels of PHLPP1, PHLPP2, TSC2, HIF1α, HIF2α, phospho-S6K (p-S6K), total S6K, and tubulin were analyzed using Western blotting. (B) The relative expression of PHLPP isoforms was quantified by normalizing ECL signals generated by the PHLPP antibodies to the level of tubulin, and this number for the control cells under normoxia was set to 1. The levels of PHLPP isoforms were compared to those of control cells under normoxia. Data shown in graphs represent the means ± standard errors of the means (n = 3; *, P < 0.05, by a two-sample t test). (C) Knockdown of 4E-BP1 rescues PHLPP expression under hypoxia. Stable control and 4E-BP1 knockdown HCT116 cells were exposed to normoxia (−) or hypoxia (1% O2; +) for 24 h. The expression levels of PHLPP1, PHLPP2, 4E-BP1, HIF1α, HIF2α, and tubulin were analyzed using Western blotting. (D) The relative expression levels of PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 were quantified by normalizing the values to the level of tubulin. The levels of PHLPP isoforms were compared to those of control cells under normoxia. Data shown in graphs represent the means ± standard errors of the means (n = 3; *, P < 0.05, by a two-sample t test). (E) Stable control, 4E-BP1, and TSC2 knockdown SW480 cells were exposed to normoxia or hypoxia for 24 h in the presence or absence of rapamycin (20 nM). Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed for the expression of PHLPP1, PHLPP2, TSC2, phospho-4E-BP1, total 4E-BP1, and tubulin using Western blotting. The expression of PHLPP was normalized to the level of the control cells under normoxia, and the numbers are indicated below the PHLPP panels.

Hypoxia downregulates PHLPP expression by promoting ubiquitination and degradation of PHLPP.

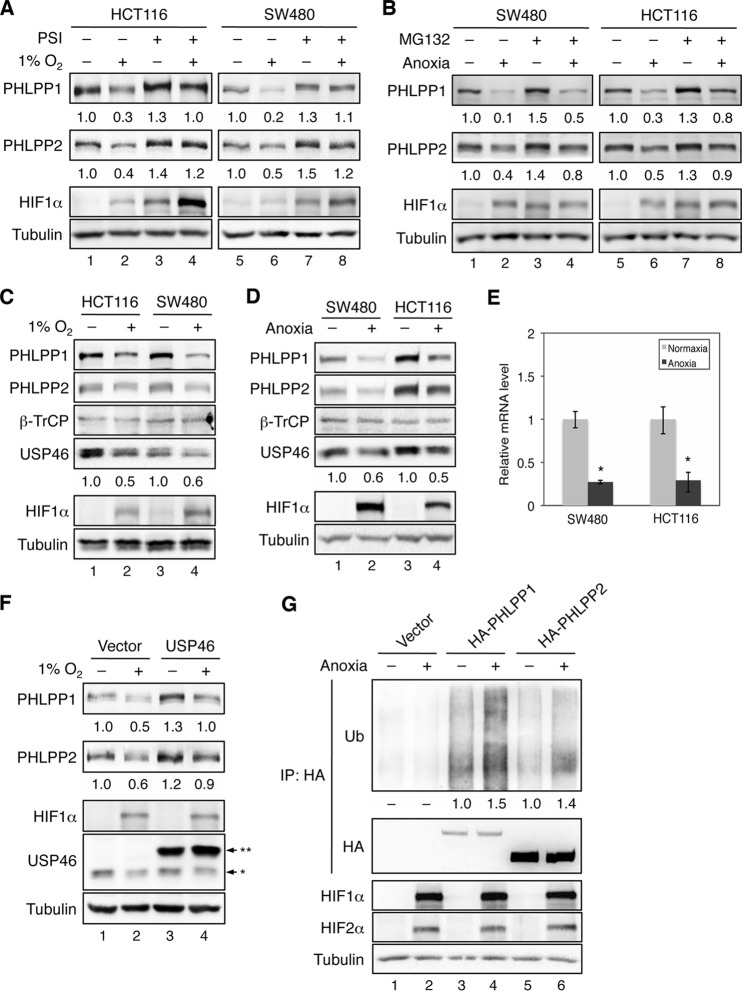

Although knockdown of TSC2 or 4E-BP1 largely rescued PHLPP from hypoxia-induced downregulation, a portion of PHLPP proteins were still lost under hypoxia (Fig. 4). To fully understand the mechanism underlying the inhibitory effect of hypoxia on PHLPP expression, we examined whether hypoxia promotes PHLPP degradation as well. Since PHLPP is degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (21), we analyzed the expression of PHLPP in cells treated with proteasome inhibitors (PSIs; a combination of bortezomib and carfilzomib) before being exposed to normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Similar to the results shown in Fig. 1, PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 levels were drastically reduced in hypoxic cells in the absence of PSIs (Fig. 5A). However, the hypoxia-induced decrease in PHLPP expression was attenuated in cells treated with PSIs, suggesting that hypoxia promotes proteasome-mediated degradation of PHLPP proteins. The basal expression of both PHLPP isoforms was also increased under normoxia when cells were treated with proteasome inhibitors, confirming PHLPP as a target of proteasome-mediated degradation (Fig. 5A). As a control, the expression of HIF1α, a known substrate of proteasomes, was preserved under normoxic conditions in cells treated with PSIs (Fig. 5A). Similar results were obtained under anoxic conditions using MG-132 to inhibit proteasome-mediated degradation (Fig. 5B).

Fig 5.

Hypoxia promotes the degradation of PHLPP isoforms by downregulating USP46 deubiquitinase. (A) Hypoxia-induced downregulation of PHLPP is partially rescued by pretreating cells with proteasome inhibitor. HCT116 and SW480 cells were exposed to normoxia or 1% O2 for 24 h. During the last 3 h of incubation, cells were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide or a combination of bortezomib and carfilzomib (PSI; 10 nM each). (B) SW480 and HCT116 cells were exposed to normoxia or anoxia for 24 h. During the last 3 h of incubation, cells were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide or MG-132 (20 μM). The expression levels of PHLPP1, PHLPP2, and tubulin were analyzed using Western blotting. The normalized expression levels of PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 are indicated by the numbers below the PHLPP panels. (C and D) The expression of USP46, a PHLPP-specific deubiquitinase, is decreased under hypoxic conditions. HCT116 and SW480 cells were exposed to normoxia (−) or 1% O2 (+) for 24 h (C); alternatively, SW480 and HCT116 cells were exposed to normoxia (−) or anoxia (+) for 24 h (D). Total protein levels of PHLPP1, PHLPP2, β-TrCP, USP46, HIF1α, HIF2α, and tubulin were detected using Western blotting. The relative expression of USP46 was quantified by normalizing to the level of tubulin and is indicated below the USP46 panel. (E) The mRNA expression of USP46 is inhibited by anoxia. Total RNAs were isolated from cells as treated as described for panel D. Real-time RT-PCR analysis was performed using probes specific for the human USP46 gene. Each experimental point was done in triplicates, and the graphs represent the means ± standard deviations (n = 3; *, P < 0.05, by a two-sample t test). (F) Overexpression of USP46 rescues PHLPP expression under hypoxia. HCT116 cells transfected with vector or Myc-USP46 were subjected to normoxia (−) or 1% O2 (+) for 24 h. Cell lysates were analyzed for the expression of PHLPP1, PHLPP2, HIF1α, USP46, and tubulin using Western blotting. Note that two bands were detected by the USP46 antibody, with a single asterisk indicating the endogenous USP46 and double asterisks indicating the Myc-USP46. (G) The ubiquitination (Ub) level of PHLPP is upregulated under anoxia. Stable SW480 cells expressing control vector, HA-PHLPP1, or HA-PHLPP2 were exposed to anoxia for 6 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) using the anti-HA Affinity Matrix. The level of ubiquitination and the amount of PHLPP in the immunoprecipitates were detected using the ubiquitin and HA antibodies, respectively. The expression of HIF1α, HIF2α, and tubulin in cell lysates was analyzed using Western blotting. The relative ubiquitination levels detected on PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 were quantified by normalizing ECL signals of ubiquitin to those of HA and are indicated below the ubiquitin panel.

Our previous studies have shown that PHLPP is ubiquitinated and degraded by β-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase (21), and this degradation process can be reversed by the deubiquitinase USP46 which removes ubiquitin chains from PHLPP and rescues PHLPP expression (22). Here, we examined whether the expression of β-TrCP or USP46 is altered by hypoxia. Coinciding with hypoxia-induced decrease of PHLPP expression, the levels of USP46 were reduced by 40 to 50% under hypoxia, whereas the expression of β-TrCP was not affected in colon cancer cells (Fig. 5C). Similar results were obtained in cells grown under anoxia (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, the RT-PCR analysis indicated that the mRNA expression of the USP46 gene was significantly decreased under anoxic conditions, suggesting a transcriptional inhibition imposed by hypoxia (Fig. 5E). To confirm the role of USP46 in hypoxia-induced downregulation of PHLPP, we expressed a Myc-tagged USP46 in HCT116 cells and monitored expression of PHLPP under hypoxia. Consistent with our previous report, overexpression of Myc-USP46 increased PHLPP expression under normoxic conditions (22). The expression of Myc-USP46 was not affected by hypoxia, whereas the amount of endogenous USP46 decreased (Fig. 5F). More importantly, hypoxia-induced downregulation of PHLPP was attenuated in cells expressing the exogenous Myc-USP46, suggesting that decreased expression of USP46 leads to destabilization of PHLPP under hypoxia (Fig. 5F).

To further determine if hypoxia promotes PHLPP degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, the levels of PHLPP ubiquitination were analyzed in stable SW480 cells overexpressing vector, HA-PHLPP1, or HA-PHLPP2 exposed to normoxia or anoxia for 6 h. Results showed that anoxia treatment increased the amount of ubiquitination of PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 by 50% and 40%, respectively (Fig. 5G). Interestingly, the ubiquitination level of PHLPP1 was much higher than that of PHLPP2 under both normoxic and anoxic conditions. This is consistent with our previous finding that the half-life of PHLPP2 is at least twice as long as that of PHLPP1 (21). Collectively, we showed that the ubiquitination and degradation of both PHLPP isoforms are enhanced under hypoxic conditions as the result of decreased transcription of USP46 mRNA.

Downregulation of PHLPP contributes to hypoxia-induced drug resistance.

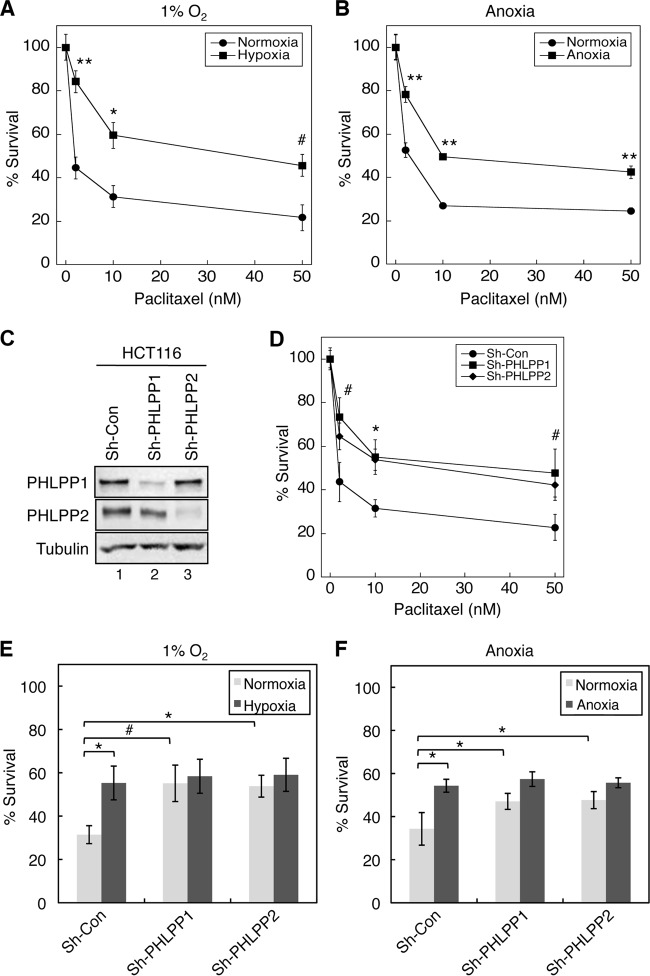

Since hypoxia is known to induce resistance to chemotherapy drugs in cancer cells, we sought to demonstrate whether hypoxia-induced downregulation of PHLPP contributes to drug resistance. To this end, we first established conditions in which colon cancer HCT116 and SW480 cells exhibited resistance to chemotherapy drugs under hypoxic conditions. Consistent with the notion that cancer cells become more resistant to chemotherapy drugs under hypoxic conditions, we found that although treating HCT116 cells with paclitaxel caused dose-dependent cell death under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions, the cytotoxic effect of the chemotherapy agent was significantly reduced under hypoxia compared to normoxic conditions (Fig. 6A and B). Next, we investigated whether downregulation of PHLPP expression contributed to the decreased drug sensitivity. Colon cancer HCT116 cells were infected with lentiviral shRNA targeting PHLPP1 (sh-PHLPP1) or PHLPP2 (sh-PHLPP2), and knockdown of PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 proteins was confirmed using Western blotting (Fig. 6C). The cells were then treated with increasing concentrations of paclitaxel for 48 h under normoxic conditions. The results showed that knockdown of either PHLPP gene rendered the cells more resistant to the drug treatment than the control cells (Fig. 6D), suggesting that both PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 play an important role in regulating drug sensitivity. Furthermore, we assessed whether loss of PHLPP expression is involved in hypoxia-induced drug resistance. HCT116 control and PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 knockdown cells were subjected to paclitaxel treatment under normoxic or hypoxic/anoxic conditions for 48 h. Consistent with data shown in Fig. 6D, hypoxia/anoxia treatment significantly increased the survival rate in control cells, indicating the induction of drug resistance; however, this hypoxia-induced survival advantage was abolished in cells depleted of PHLPP1 or PHLPP2 expression as the knockdown cells became equally sensitive to paclitaxel under both normoxic and hypoxic/anoxic conditions (Fig. 6E and F).

Fig 6.

Loss of PHLPP expression contributes to hypoxia-induced drug resistance in HCT116 cells. (A and B) Hypoxia induces resistance to paclitaxel in colon cancer cells. HCT116 cells were treated with different concentrations of paclitaxel for 48 h under hypoxic (1% O2) (A) or anoxic (B) conditions. Cell viability was determined using MTS assays, and the percentage of survival was calculated by normalizing the results for drug-treated groups to those of untreated control groups. Each experimental point was done in quadruplicate, and the graph represents the average of two independent experiments. Two-sample t tests were performed to compare the results obtained in cells under hypoxia/anoxia to those of cells under normoxia (means ± standard deviations; #, P < 0.05; *, P < 0.005; **, P < 0.001). (C) Cell lysates isolated from control and PHLPP knockdown HCT116 cells were analyzed to determine the expression of PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 using Western blotting. (D) Knockdown of PHLPP expression rendered HCT116 cells resistant to paclitaxel. Cells infected with lentivirus encoding control shRNA (Sh-con) or shRNA for PHLPP1 (Sh-PHLPP1) or PHLPP2 (Sh-PHLPP2) were subjected to treatment with paclitaxel for 48 h. Cell viability was determined as described in panel A. Two-sample t tests were performed to compare the results obtained in PHLPP knockdown cells to results of control cells. Data represents means ± standard deviations (n = 4; #, P < 0.05; *, P < 0.005). (E and F) Control and PHLPP knockdown HCT116 cells as described in panel D were treated with paclitaxel (10 nM) for 48 h under hypoxic (E) or anoxic (F) conditions. The percent survival was calculated by normalizing results of drug-treated groups to those of untreated control groups. The results obtained in PHLPP knockdown cells were compared to those of control cells. Data represent means ± standard deviations (n = 4; #, P < 0.05; *, P < 0.005, as determined by two-sample t tests). No statistically significant differences were observed within PHLPP1 or PHLPP2 knockdown cell lines for comparisons between the normoxic and hypoxic conditions.

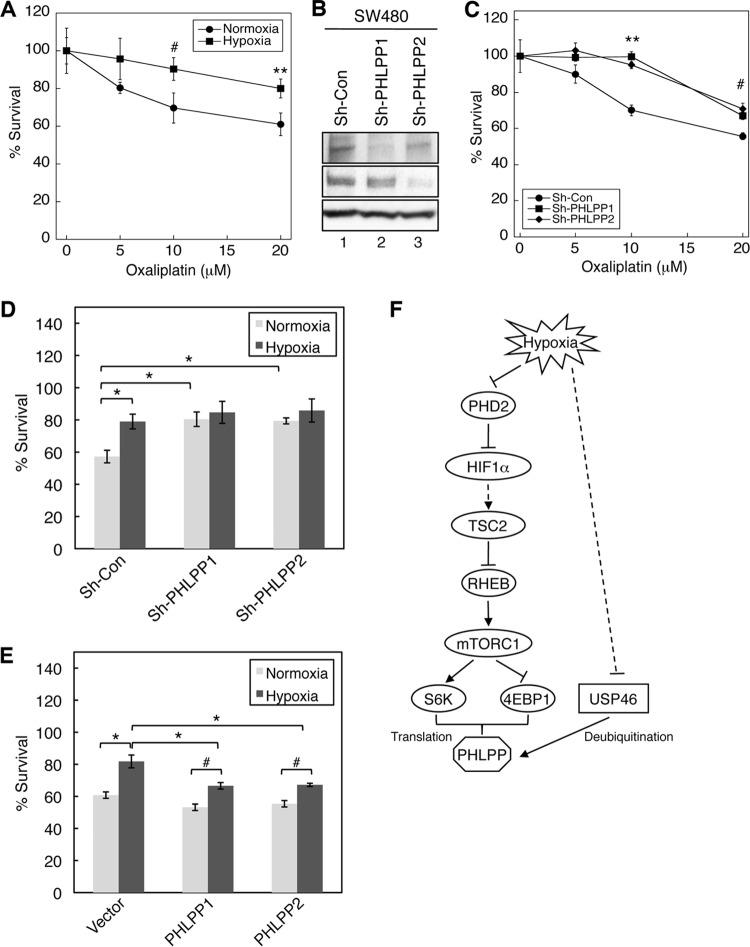

The effect of PHLPP on chemosensitivity to another chemotherapy drug, oxaliplatin, was confirmed in SW480 cells. Specifically, SW480 cells were more resistant to oxaliplatin under hypoxia (Fig. 7A), and knockdown of PHLPP1 or PHLPP2 expression conferred this chemoresistance (Fig. 7B and C). In addition, the hypoxia-induced increase in cell survival was eliminated in PHLPP knockdown cells (Fig. 7D). Furthermore, we tested whether overexpression of exogenous PHLPP renders cells more sensitive to the chemotherapy agent. Indeed, the percent cell survival was significantly decreased in PHLPP overexpressing cells compared to that of vector transfected cells under hypoxia, suggesting that increased PHLPP expression enhanced the cytotoxic effect of oxaliplatin (Fig. 7E). However, hypoxia-induced chemoresistance observed in control cells persisted in PHLPP-overexpressing cells (i.e., the survival rates remained higher under hypoxia for PHLPP-overexpressing cells). This is likely due to the fact that the expression of exogenous PHLPP (HA-PHLPP1 and HA-PHLPP2) was not completely hypoxia resistant. We found that overexpressed PHLPP proteins were still sensitive to hypoxia-induced protein degradation (data not shown) as they were destabilized in hypoxic cells with reduced USP46 levels. In addition, other cellular factors may be needed to allow overexpressed PHLPP to function properly. For example, a recent study has shown that FKBP51, a scaffolding protein of PHLPP, affects the chemosensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells by enhancing PHLPP-mediated dephosphorylation of Akt (30). More studies are needed to better understand the role PHLPP in determining chemosensitivity. Taken together, our results demonstrate that loss of PHLPP expression contributed to hypoxia-induced resistance to chemotherapy drugs in colon cancer cells.

Fig 7.

Loss of PHLPP expression contributes to hypoxia-induced drug resistance in SW480 cells. (A) SW480 cells were treated with different concentrations of oxaliplatin for 48 h under normoxia or hypoxia (1% O2). Cell viability was determined using MTS assays, and the percentage of survival was calculated by normalizing results of drug-treated groups to those of untreated control groups. Each experimental point was done in quadruplicate, and the graph represents averages of two independent experiments. Two-sample t tests were performed to compare the results obtained in cells under hypoxia to those of cells under normoxia (means ± standard deviations; #, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001). (B) Cell lysates isolated from control and PHLPP knockdown SW480 cells were analyzed to determine the expression of PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 using Western blotting. (C) SW480 cells infected with lentivirus encoding control shRNA (Sh-con) or shRNA for PHLPP1 (Sh-PHLPP1) or PHLPP2 (Sh-PHLPP2) were treated with different concentrations of oxaliplatin for 48 h. Cell viability was determined as described in panel A. Two-sample t tests were performed to compare the results obtained in PHLPP knockdown cells to those of control cells. Data represent means ± standard deviations (n = 4; #, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001). (D) Control and PHLPP knockdown cells as described in panel C were subjected to treatment with oxaliplatin (20 μM) for 48 h under normoxic or hypoxic (1% O2) conditions. The percentage of survival was calculated by normalizing values of drug-treated groups to those of untreated control groups. The results obtained in PHLPP knockdown cells were compared to those of control cells. Data represent means ± standard deviations (n = 4; *, P < 0.005, as determined by two-sample t tests). No statistically significant differences were observed within PHLPP1 or PHLPP2 knockdown cell lines in comparisons between the normoxic and hypoxic conditions. (E) SW480 cells overexpressing vector, HA-PHLPP1, or HA-PHLPP2 were subjected to treatment with oxaliplatin (20 μM) for 48 h under normoxic or hypoxic (1% O2) conditions. The percentage of survival was analyzed as described in panel D. The results obtained in PHLPP knockdown cells were compared to those of control cells. Data represent means ± standard deviations (n = 4; #, P < 0.05; *, P < 0.005 as determined by two-sample t tests). (F) Diagram showing the mechanism underlying hypoxia-mediated downregulation of PHLPP expression. Our study demonstrates that mTOR-dependent translation of PHLPP is inhibited under hypoxia and that this hypoxia-induced inhibition of mTOR, at least in part, is mediated via TSC2, an upstream regulator of mTOR. Knocking down TSC2 or 4E-BP1, a downstream effector of mTOR, partially rescues PHLPP expression under hypoxia. In addition, hypoxia negatively regulates the level of USP46 mRNA expression. As a consequence, the ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation of PHLPP are increased. Functionally, downregulation of PHLPP contributes to hypoxia-induced chemoresistance in colon cancer cells.

In summary, we have identified two main mechanisms that contribute to PHLPP loss under hypoxic conditions: (i) inhibition of mTOR-mediated translation of PHLPP proteins and (ii) upregulation of proteasome-mediated degradation of PHLPP (Fig. 7F). Consistent with previous reports that TSC2 is an essential mediator that relays energy stress signals downstream of hypoxia to inhibit mTOR-dependent protein translation (6, 31, 32), we found that hypoxia-induced downregulation of PHLPP can be rescued by silencing TSC2. Similarly, knockdown of 4E-BP1, a downstream negative regulator of mTOR-mediated protein translation, attenuates the effect of hypoxia on PHLPP expression. In addition, we found that expression of USP46 mRNA is decreased under hypoxia, which results in an increase in the ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation of PHLPP. More importantly, our study demonstrated the importance of maintaining PHLPP expression in preventing chemoresistance in cancer treatment.

DISCUSSION

The effect of hypoxia on tumor initiation and progression has been extensively studied in recent years. Clinical investigations have clearly demonstrated that hypoxic and/or anoxic tissue areas are prevalently associated with solid tumors as the result of poor oxygen delivery (27). Upregulation of HIF-mediated signaling plays a positive role in tumorigenesis by helping tumor cells to adapt to the hypoxic environment (2). Specifically, HIFs are known to have multifaceted functions in promoting tumor progression in colon cancer. Upregulation of HIF1α and HIF2α is detected in 19% and 46% of colorectal cancer patients, respectively, and overexpression of HIF1α is significantly associated with higher mortality (2, 33). Hypoxia and HIF1α specifically enhance clonogenicity and suppress differentiation of cancer stem cells in colon cancer (34). Moreover, HIF-dependent upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been used as a drug target for treating metastatic colon cancer patients (35). In this study, we determined the role of hypoxia in promoting the downregulation of tumor suppressor PHLPP. Loss of both PHLPP isoforms occurs at high frequency in colorectal cancer patients (18). However, the mechanism underlying PHLPP downregulation in cancer is not clear. Our study here has shown that tumor-associated hypoxia promotes rapid downregulation of both PHLPP isoforms in colon cancer cells, and this decrease in PHLPP expression is mediated through inhibition of mTOR-dependent protein translation and upregulation of ubiquitination-dependent PHLPP degradation. Therefore, we have identified hypoxia as a novel mechanism leading to PHLPP downregulation in cancer. In addition, since hypoxia and loss of PHLPP expression exert similar functions in tumorigenesis, in which both are capable of promoting cell proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis, results from our study have also established a functional connection between hypoxia and downregulation of PHLPP. During the tumorigenesis process, when tumor cells begin to experience hypoxia, downregulation of PHLPP resulting from oxygen deprivation would give an additional growth advantage and promote tumor progression.

Interestingly, we found that knockdown of HIF1α is sufficient to rescue PHLPP from hypoxia-induced downregulation, although not completely (this is likely due to the fact that a low level still remains in the knock down cells). In marked contrast, silencing HIF2α expression has no effect on PHLPP expression under hypoxic conditions. Recent studies have suggested that HIF1α and HIF2α may have independent roles in different tumor models (29). In the case of colon cancer cells, it has been reported that HIF1α facilitates cell growth in vitro and tumorigenesis in vivo, whereas HIF2α has the opposite effect (28). Thus, downregulation of PHLPP is likely one of the contributing factors that mediate HIF1α-dependent tumorigenesis in colon cancer cells. Moreover, it has been shown previously that hypoxia-induced inhibition of protein translation can be mediated via REDD1, a known HIF1α target gene under hypoxia, and REDD1-mediated suppression of translation requires TSC2 (6, 31). Our findings that knockdown of TSC2 rescues PHLPP expression under hypoxia suggested that a REDD1/TSC2/mTOR-dependent mechanism may be involved in mediating HIF1α-induced inhibition of PHLPP expression. Interestingly, a recent study showed that mTOR preferentially controls the translation of transcripts that contain 5′ TOP or TOP-like motifs (36). Consistent with this notion, we found that the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of PHLPP1 mRNA contains a terminal oligopyrimidine (TOP) motif (5′-CTTCTCCCTTCTCC-3′) and that PHLPP2 mRNA contains a TOP-like motif (5′-CCTTGCC-3′).

Both isoforms of PHLPP serve as tumor suppressors in colon cancer as overexpression of either PHLPP is sufficient to inhibit tumorigenesis (18). Intriguingly, our previous studies have shown that the expression of PHLPP1 is more sensitive to the alteration of environmental cues than expression of PHLPP2. For example, rapid downregulation of PHLPP1 is observed in cells exposed to nutrient deprivation or treated with rapamycin, whereas PHLPP2 is more stable (25). Here, we found that hypoxia also has a more pronounced effect on PHLPP1 ubiquitination and degradation than on PHLPP2. The longer half-life of PHLPP2 is consistent with the notion that it lacks certain phosphorylation sites required for mediating protein ubiquitination (21). In addition, our study has identified USP46 as a novel target of hypoxia. We have previously shown that USP46 functions as a tumor suppressor by stabilizing PHLPP expression (22). However, little is known about how USP46 is regulated in cancer. Our finding that the transcription of USP46 mRNA is inhibited by hypoxia provides a novel mechanism of USP46 regulation. Similarly, hypoxia-induced downregulation of E-cadherin and proapoptotic proteins such as Bid and Bad is also known to be mediated via a transcriptional mechanism (10, 37).

A number of studies have highlighted the importance of targeting hypoxia in cancer therapy due to the chemoresistance often associated with hypoxia (12). Several different mechanisms, such as downregulation of proapoptotic factors and upregulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), have been suggested for hypoxia-mediated drug resistance (10, 38). More recently, it has been shown that downregulation of dual-specificity phosphatase 2 (DUSP2) leads to reduced sensitivity to MEK inhibitors in HeLa cells (11). In our current study, we demonstrated that the level of PHLPP expression regulates drug sensitivity in colon cancer cells and that downregulation of PHLPP contributes to hypoxia-induced chemoresistance. These findings are consistent with the established role of PHLPP in promoting apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation in various cancer cells (18, 20, 23, 24, 39).

In summary, we have identified PHLPP as a critical factor in determining drug sensitivity under hypoxic conditions. Our study adds yet another important function of PHLPP and provides rationales for taking PHLPP into consideration when the treatment options for colon cancer patients are being evaluated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Natasha Kyprianou, Peter Zhou, and Yadi Wu (University of Kentucky) for providing technical assistant in setting up hypoxia-related experiments in our study.

This work was supported by NIH grant R01CA133429 (T.G.) and American Cancer Society grant RSG0822001TBE (T.G.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 23 September 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Lu X, Kang Y. 2010. Hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factors: master regulators of metastasis. Clin. Cancer Res. 16:5928–5935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rankin EB, Giaccia AJ. 2008. The role of hypoxia-inducible factors in tumorigenesis. Cell Death Differ. 15:678–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majmundar AJ, Wong WJ, Simon MC. 2010. Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol. Cell 40:294–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, Wilson MI, Gielbert J, Gaskell SJ, Kriegsheim A, Hebestreit HF, Mukherji M, Schofield CJ, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. 2001. Targeting of HIF-α to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 292:468–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW, Clifford SC, Vaux EC, Cockman ME, Wykoff CC, Pugh CW, Maher ER, Ratcliffe PJ. 1999. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature 399:271–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brugarolas J, Lei K, Hurley RL, Manning BD, Reiling JH, Hafen E, Witters LA, Ellisen LW, Kaelin WG., Jr 2004. Regulation of mTOR function in response to hypoxia by REDD1 and the TSC1/TSC2 tumor suppressor complex. Genes Dev. 18:2893–2904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wouters BG, van den Beucken T, Magagnin MG, Koritzinsky M, Fels D, Koumenis C. 2005. Control of the hypoxic response through regulation of mRNA translation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 16:487–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma XM, Blenis J. 2009. Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10:307–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown JM, Wilson WR. 2004. Exploiting tumour hypoxia in cancer treatment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4:437–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erler JT, Cawthorne CJ, Williams KJ, Koritzinsky M, Wouters BG, Wilson C, Miller C, Demonacos C, Stratford IJ, Dive C. 2004. Hypoxia-mediated down-regulation of Bid and Bax in tumors occurs via hypoxia-inducible factor 1-dependent and -independent mechanisms and contributes to drug resistance. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:2875–2889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin SC, Chien CW, Lee JC, Yeh YC, Hsu KF, Lai YY, Tsai SJ. 2011. Suppression of dual-specificity phosphatase-2 by hypoxia increases chemoresistance and malignancy in human cancer cells. J. Clin. Invest. 121:1905–1916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson WR, Hay MP. 2011. Targeting hypoxia in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11:393–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brognard J, Newton AC. 2008. PHLiPPing the switch on Akt and protein kinase C signaling. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 19:223–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiao M, Wang Y, Xu X, Lu J, Dong Y, Tao W, Stein J, Stein GS, Iglehart JD, Shi Q, Pardee AB. 2010. MstI is an interacting protein that mediates PHLPPs' induced apoptosis. Mol. Cell 38:512–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimizu K, Mackenzie SM, Storm DR. 2010. SCOP/PHLPP and its functional role in the brain. Mol. Biosyst. 6:38–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warfel NA, Newton AC. 2012. Pleckstrin homology domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase (PHLPP): a new player in cell signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 287:3610–3616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen M, Pratt CP, Zeeman ME, Schultz N, Taylor BS, O'Neill A, Castillo-Martin M, Nowak DG, Naguib A, Grace DM, Murn J, Navin N, Atwal GS, Sander C, Gerald WL, Cordon-Cardo C, Newton AC, Carver BS, Trotman LC. 2011. Identification of PHLPP1 as a tumor suppressor reveals the role of feedback activation in PTEN-mutant prostate cancer progression. Cancer Cell 20:173–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J, Weiss HL, Rychahou P, Jackson LN, Evers BM, Gao T. 2009. Loss of PHLPP expression in colon cancer: role in proliferation and tumorigenesis. Oncogene 28:994–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molina JR, Agarwal NK, Morales FC, Hayashi Y, Aldape KD, Cote G, Georgescu MM. 2012. PTEN, NHERF1 and PHLPP form a tumor suppressor network that is disabled in glioblastoma. Oncogene 31:1264–1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nitsche C, Edderkaoui M, Moore RM, Eibl G, Kasahara N, Treger J, Grippo PJ, Mayerle J, Lerch MM, Gukovskaya AS. 2012. The phosphatase PHLPP1 regulates Akt2, promotes pancreatic cancer cell death, and inhibits tumor formation. Gastroenterology 142:377–387.e1-5. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Liu J, Gao T. 2009. β-TrCP-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of PHLPP1 are negatively regulated by Akt. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:6192–6205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, Stevens PD, Yang H, Gulhati P, Wang W, Evers BM, Gao T. 2013. The deubiquitination enzyme USP46 functions as a tumor suppressor by controlling PHLPP-dependent attenuation of Akt signaling in colon cancer. Oncogene 32:471–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brognard J, Sierecki E, Gao T, Newton AC. 2007. PHLPP and a second isoform, PHLPP2, differentially attenuate the amplitude of Akt signaling by regulating distinct Akt isoforms. Mol. Cell 25:917–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao T, Furnari F, Newton AC. 2005. PHLPP: a phosphatase that directly dephosphorylates Akt, promotes apoptosis, and suppresses tumor growth. Mol. Cell 18:13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J, Stevens PD, Gao T. 2011. mTOR-dependent regulation of PHLPP expression controls the rapamycin sensitivity in cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286:6510–6520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larson Y, Liu J, Stevens PD, Li X, Li J, Evers BM, Gao T. 2010. Tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) regulates cell migration and polarity through activation of CDC42 and RAC1. J. Biol. Chem. 285:24987–24998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaupel P, Mayer A. 2007. Hypoxia in cancer: significance and impact on clinical outcome. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 26:225–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imamura T, Kikuchi H, Herraiz MT, Park DY, Mizukami Y, Mino-Kenduson M, Lynch MP, Rueda BR, Benita Y, Xavier RJ, Chung DC. 2009. HIF-1α and HIF-2α have divergent roles in colon cancer. Int. J. Cancer 124:763–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keith B, Johnson RS, Simon MC. 2012. HIF1αand HIF2α: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12:9–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pei H, Li L, Fridley BL, Jenkins GD, Kalari KR, Lingle W, Petersen G, Lou Z, Wang L. 2009. FKBP51 affects cancer cell response to chemotherapy by negatively regulating Akt. Cancer Cell 16:259–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeYoung MP, Horak P, Sofer A, Sgroi D, Ellisen LW. 2008. Hypoxia regulates TSC1/2-mTOR signaling and tumor suppression through REDD1-mediated 14-3-3 shuttling. Genes Dev. 22:239–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu L, Cash TP, Jones RG, Keith B, Thompson CB, Simon MC. 2006. Hypoxia-induced energy stress regulates mRNA translation and cell growth. Mol. Cell 21:521–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baba Y, Nosho K, Shima K, Irahara N, Chan AT, Meyerhardt JA, Chung DC, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. 2010. HIF1A overexpression is associated with poor prognosis in a cohort of 731 colorectal cancers. Am. J. Pathol. 176:2292–2301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeung TM, Gandhi SC, Bodmer WF. 2011. Hypoxia and lineage specification of cell line-derived colorectal cancer stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:4382–4387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marshall J. 2005. The role of bevacizumab as first-line therapy for colon cancer. Semin. Oncol. 32:S43–S47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thoreen CC, Chantranupong L, Keys HR, Wang T, Gray NS, Sabatini DM. 2012. A unifying model for mTORC1-mediated regulation of mRNA translation. Nature 485:109–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Esteban MA, Tran MG, Harten SK, Hill P, Castellanos MC, Chandra A, Raval R, O'Brien ST, Maxwell PH. 2006. Regulation of E-cadherin expression by VHL and hypoxia-inducible factor. Cancer Res. 66:3567–3575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cannito S, Novo E, Compagnone A, Valfre di Bonzo L, Busletta C, Zamara E, Paternostro C, Povero D, Bandino A, Bozzo F, Cravanzola C, Bravoco V, Colombatto S, Parola M. 2008. Redox mechanisms switch on hypoxia-dependent epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 29:2267–2278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dibble CC, Manning BD. 2009. A molecular link between AKT regulation and chemotherapeutic response. Cancer Cell 16:178–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]