Abstract

Retrovirus maturation involves sequential cleavages of the Gag polyprotein, initially arrayed in a spherical shell, leading to formation of capsids with polyhedral or conical morphology. Evidence suggests that capsids assemble de novo inside maturing virions from dissociated capsid (CA) protein, but the possibility persists of a displacive pathway in which the CA shell remains assembled but is remodeled. Inhibition of the final cleavage between CA and spacer peptide SP1/SP blocks the production of mature capsids. We investigated whether retention of SP might render CA assembly incompetent by testing the ability of Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) CA-SP to assemble in vitro into icosahedral capsids. Capsids were indeed assembled and were indistinguishable from those formed by CA alone, indicating that SP was disordered. We also used cryo-electron tomography to characterize HIV-1 particles produced in the presence of maturation inhibitor PF-46396 or with the cleavage-blocking CA5 mutation. Inhibitor-treated virions have a shell that resembles the CA layer of the immature Gag shell but is less complete. Some CA protein is generated but usually not enough for a mature core to assemble. We propose that inhibitors like PF-46396 bind to the Gag lattice where they deny the protease access to the CA-SP1 cleavage site and prevent the release of CA. CA5 particles, which exhibit no cleavage at the CA-SP1 site, have spheroidal shells with relatively thin walls. It appears that this lattice progresses displacively toward a mature-like state but produces neither conical cores nor infectious virions. These observations support the disassembly-reassembly pathway for core formation.

INTRODUCTION

Formation of infectious retroviral particles is a two-step process that begins with assembly of the Gag polyprotein into a spherical shell as it buds through the plasma membrane to form the immature virion. This is followed by maturation—a program of proteolytic cleavage of Gag by the viral protease (PR) and structural remodeling that leads eventually to infectious particles. Disruption of maturation results in virions with profound defects in infectivity, often accompanied by altered morphology. Maturation is ultimately the process that is abrogated by protease-inhibitor drugs (1), and it is also the target of “maturation inhibitors” that impede the last step in the Gag processing cascade, apparently by interacting with the Gag substrate rather than PR (2, 3).

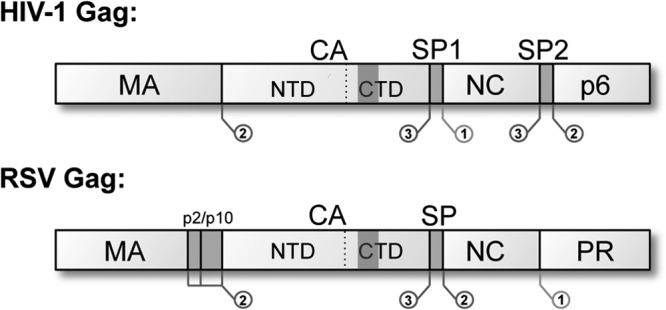

Gag proteins have a matrix domain (MA), a capsid domain (CA), and an RNA-binding nucleocapsid domain (NC), as well as several, mostly smaller, virus-specific domains, including a “spacer” between CA and NC (4, 5). Domain maps for HIV-1 and Rous sarcoma virus (RSV), the two viruses addressed in this study, are shown in Fig. 1. In the immature virion, an incomplete spherical shell is formed from an array of Gag hexamers, with the domains ordered from N-terminal (outside) to C-terminal (inside). In particular, CA is primarily responsible for Gag-Gag interactions and later, during maturation, undergoes radical rearrangement to form the capsid or “core” of the mature virion. Cores are polymorphic, with the predominant form varying among different retroviruses: they can be cones, irregular polyhedra, tubes, or spheres, but all are foldings of a common fullerene lattice (6–8) of hexamers punctuated with vertices. For closed shells, the vertices are 12 in number and they are thought to be occupied by CA pentamers (9, 10). The mature lattice is relatively thin (see below) and has an interhexamer spacing of 9.2 nm, whereas the immature CA lattice is thicker and has a periodicity of 8.0 nm (11–14).

Fig 1.

Domain maps of HIV-1 and RSV Gag proteins. Both retroviruses contain a short “spacer” peptide between CA and NC, which is removed from CA in the final cleavage step of maturation. In HIV-1, this domain is called SP1 and contains 14 residues; in RSV, this domain is called SP and contains 12 residues. The location and sequence of PR cleavage sites are indicated within Gag. The shaded regions in the CTDs mark the MHRs.

CA has an N-terminal domain (NTD) and a C-terminal domain (CTD), separated by a flexible linker. The NTD contains seven α-helices, while the CTD contains four. The secondary and tertiary structures of retroviral CA proteins are highly conserved, despite little sequence similarity (15–19). The mature lattice is coordinated by three major interactions: the CTD contains a dimerization interface in helix 9 that bridges adjacent hexamers, while NTD-NTD interactions involving helices 1 to 3, plus an interaction between NTD helix 4 and CTD helix 8 of the adjacent subunit, form the contacts that stabilize the hexamer (4, 20, 21). Pentamers are held together by a quasiequivalent set of these interactions (9, 10). Recent cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) analysis of in vitro-assembled HIV-1 CA tubes suggests the presence of an additional CTD-CTD interhexamer contact in the mature lattice (22, 23). A study that combined cryo-electron microscopy and tomography to develop a pseudoatomic model of CA in immature Mason-Pfizer monkey virus particles concluded that inter-CA contacts differ substantially between immature and mature virions (24).

The final step in PR-mediated cleavage of Gag generates mature CA protein by removing the spacer peptide from its C-terminal end (25–29). The spacer—called SP1 for HIV-1 and SP for RSV—plays an important role in assembly and maturation as attested by the observation that interventions affecting this region have drastic consequences (26, 27, 30–34). Specifically, blockage of CA-SP1 cleavage by maturation inhibitors, such as the class prototype bevirimat (BVM), results in virions with severely reduced infectivity, accompanied by failure to assemble a mature core (2, 35–37).

The maturation mechanism remains unclear, and virion polymorphism combined with lack of synchrony in maturing populations has made controlled study difficult. Nevertheless, two broad models for retroviral maturation have been proposed. One envisages a “displacive” transformation of the proteolytically processed CA lattice whereby it changes shape from spherical to polyhedral—conical in the case of HIV-1. The second model envisages instead that the immature lattice disassembles following cleavage by PR, generating a pool of soluble CA protein from which a mature core reassembles de novo. This model is supported by several lines of evidence: notably, in addition to the core, mature virions have been shown to contain a large pool of unassembled CA protein (38–40), and there has been no evidence of partial immature lattices remaining in wild-type mature virions. However, a conclusive demonstration for this mechanism has not been accomplished. Moreover, capsid maturation is a phenomenon that takes place and correlates with infectivity in many other viral systems and in all cases on record involves a displacive transformation in which the capsid topology is preserved. With retroviruses, in contrast, the mature core is quite different in size and CA copy number from the precursor Gag shell. There is, however, a possible precedent for such a transformation in that displacive transformation has been proposed to mediate the production of spheroidal clathrin coats (which are also fullerene structures) from initially flat sheets (41).

Here, we have used a two-pronged approach to investigate retroviral maturation. It combines observations on two retroviruses, each of which was amenable to a particular line of experimentation. First, we investigated how in vitro assembly of CA into capsids was affected by retention of the spacer peptide, using cryo-EM single particle analysis (SPA). These experiments were performed in the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) system, which has provided numerous insights into current models of retroviral assembly/maturation (6, 42, 43). We find that removal of the SP peptide is not required for CA to assemble into capsids. Second, we extended our earlier studies with HIV-1 maturation inhibitors, using cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) to characterize their effects on the structure of wild-type (WT) virions and of a strain mutated to prevent cleavage at the CA-SP1 scissile site. From these observations, we conclude that disassembly of the immature-like lattice does appear to be needed for a proper core to be assembled. On the other hand, if maturational proteolysis goes to completion except at the CA-SP1 sites, the resulting lattice appears to be metastable and can convert displacively into a mature-like conformation, although the resulting virions are nonviable. Therefore, we conclude that the requirement for CA-SP1/SP cleavage during maturation is to mediate disassembly of the immature CA lattice. Our results are consistent with a model whereby mature cores assemble de novo from the resulting pool of free CA protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Single particle analysis.

RSV CA-SP protein was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 and purified by ion-exchange and size exclusion chromatography, as previously described (42). Purified protein was assembled at a ∼2-mg/ml concentration in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 75 mM NaCl, and 0.05 mM EDTA, plus 0.5 M NaPO4, pH 7.5, the same conditions used previously for mature CA (10). Assembly products were visualized using a Philips CM200-FEG microscope operating at 120 keV, recording images on film at ×50,000 magnification. The electron dose was ∼15 e−/Å2. Negatives were digitized at 1.27 Å/pixel with a Super CoolScan 9000 ED (Nikon). Approximately 3,500 of the ∼18-nm particles were picked manually and subjected to iterative icosahedral alignment and reconstruction using bsoft (44). Two initial templates were used for independent alignments of the ∼18-nm particles in order to minimize template bias: the first was based on the solved RSV CA T=1 particle structure (10) and the second was used by assigning random icosahedral orientations to a subset of the ∼18-nm CA-SP particles and reconstructing them. The ∼30-nm particles were aligned using a smooth icosahedral shell of matching diameter as an initial template. An independent reconstruction was performed on the central shell of 30-nm particles by masking out the outer shell density and aligning with a smooth icosahedral shell 18 nm in diameter as the initial template. Iterative orientation finding and refinement for all reconstructions were performed using borient and brefine, respectively. The final reconstructions of the 18-nm particle had full contrast transfer function (CTF) correction applied using bctf. Resolution was calculated by Fourier shell correlation (FSC) of two independent half-data-set reconstructions and was 8.5 Å for the T=1 CA-SP particle or 1.8 nm for the T=3 CA-SP particle (FSC = 0.3 threshold). Atomic models of the CA NTD (Protein Data Bank [PDB] 1em9) and CTD (PDB 1eoq) were fitted independently into the T=1 reconstruction density as rigid bodies using the docking tools in UCSF Chimera (45). The density map of the RSV-CA capsid (10) in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB code 1862) was used to calculate sections and renderings to allow direct comparisons and to confirm consistent fitting of the atomic models. The EMDB accession numbers for the RSV-CA-SP capsids determined in this study are 5772 (T=1) and 5773 (T=3).

Cell culture and maturation inhibitors.

293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS), l-glutamine (2 mM), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were transfected by using Lipofectamine 2000 as recommended by the supplier (Invitrogen). Bevirimat (BVM) and PF-46396 were prepared as previously reported (46) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted to a working concentration of 5 μM for PF-46396 or 4 μM for bevirimat (BVM) in treated culture media.

Virus particles.

Particles were prepared for cryo-ET as previously described (36). 293T or COS cells were transfected with HIV-1 molecular clone pNL4-3 (47), pNL4-3/PR− (48), or pNL4-3/CA5 (26). Briefly, transfected cells were incubated with or without maturation inhibitor and then washed and incubated for an additional 6 to 9 h. Particles were then harvested from culture supernatant, clarified by low-speed centrifugation and filtration, and concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 28,000 rpm for 2 h at 4°C using a Sorvall AH-629 rotor. The pellet was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and inactivated by addition of paraformaldehyde to a final concentration of 2% prior to EM sample preparation.

Cryo-electron tomography.

Cryo-ET was performed as previously described (36, 43). Inactivated purified virus was mixed with a solution of 10-nm colloidal gold particles (EMS) to serve as fiducial alignment markers during reconstruction. Drops of 3.5 to 4 μl of this mixture were applied to glow-discharged Quantifoil R2/2 holey carbon grids and allowed to adsorb for 30 s. Immediately following adsorption, the grid was blotted and plunge-frozen in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot cryostation (FEI). Frozen grids were transferred to an EM cryoholder (Gatan) for data collection. Images were acquired on a Tecnai T12 transmission electron microscope (TEM) (FEI), operating at 120 keV with a postcolumn energy filter (Gatan) operating in zero-loss mode. Tilt series data were collected on a 2k-by-2k charge-coupled device (CCD) camera, over an average angular range of ±64°, with an image recorded every 2°. Total electron dose for each series was limited to 35 to 70 e−/Å2, with an image pixel size of 7.8 Å (×38,500 magnification). Images were captured with a nominal defocus of −4 μm.

Reconstruction and averaging.

Tilt series were aligned and reconstructed using bsoft (49), according to the same procedures as our analysis of BVM-treated virions (36); CTF correction was not applied to the images. Resolution of the reconstructions was estimated by the NLOO-2D method (50) and averaged between 5 and 6 nm for individual reconstructions used in subsequent analysis. Following reconstruction, tomograms were denoised using nonlinear anisotropic diffusion filtering. Virus particles were extracted from raw and denoised reconstructions for subsequent analysis. Particles containing shell structures analyzed for lattice features were subject to subtomogram averaging, carried out as previously described (36). Briefly, shells of interest were modeled in three dimensions (3D) as a sphere of points, from which the area(s) of interest was selected and 3-dimensional subvolumes were extracted from around each point. Mature cores were modeled similarly but using an initial model of points approximating the conical core shape, rather than a spherical set of points. The extracted subvolumes were subjected to iterative averaging and alignment, using the programs bfind and bxb, to produce final subtomogram averages. Subtomogram averages had resolutions between 4 and 5 nm.

The point models were also used to measure the extent of the shells in PR− and PF-46396-treated virions. Regions of the virions and models affected by the missing wedge were masked out of the analysis, and the remaining points were scored as either covering a region with lattice or covering a region without lattice. Lattice completeness was calculated as the simple average of lattice points over total points scored.

RESULTS

In vitro assembly of RSV CA-SP capsids.

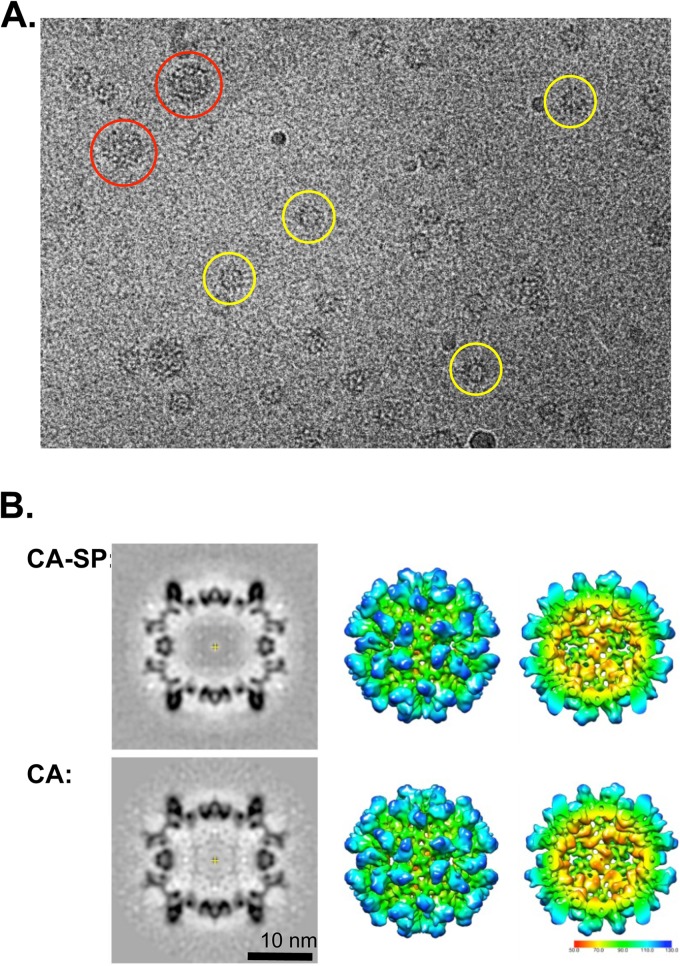

First, we tested the hypothesis that retention of the spacer peptide might adversely affect the ability of CA to self-assemble. This was done in the RSV system where previous work had shown that purified recombinant CA can self-assemble in vitro in the presence of 0.5 M phosphate into icosahedral capsids (10, 42, 51). These capsids appear to emulate the conformation of the mature lattice (9, 11, 14, 16), although they have a higher ratio of pentamers to hexamers than in native polyhedral capsids. Thus, CA-SP protein was expressed and purified and subjected to the same assembly conditions (52). The resulting particles are illustrated in Fig. 2A. As with CA alone, the CA-SP particles fall into two size classes, with diameters of ∼18 nm (∼90%) and ∼30 nm (∼10%), respectively. Three-dimensional reconstructions were calculated from particles in both classes. The density map of the smaller particle, calculated from ∼3,500 particles, reached a resolution of 8.5 Å. It reveals a T=1 capsid that is compared in Fig. 2B with the earlier reconstruction of the corresponding CA capsid. The two particles are essentially indistinguishable. We conclude that in vitro CA-SP can self-assemble in much the same way as CA (52).

Fig 2.

Cryo-EM of RSV CA-SP T=1 capsid. (A) A cryo-electron micrograph of in vitro-assembled CA-SP capsids. Spherical particles of two size classes, small (T=1, some examples marked with yellow circles and large (T=3, red circles), are embedded in the vitreous ice layer. (B) The T=1 CA-SP particles reconstructed to 8.5-Å resolution and compared with the corresponding CA capsid (10) EMDB code 1862 shown here to allow direct comparison. At left are central slices of the capsids viewed along a 2-fold axis of symmetry. Also shown are surface renderings of the reconstructions, color coded according to radius from the capsid center: outer surface (middle panel) and cutaway view of the inner surface (right panel).

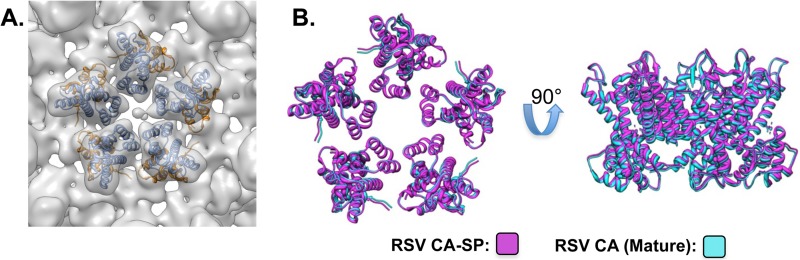

Atomic models of the RSV CA-NTD and CA-CTD could be fitted unambiguously as rigid bodies into the density maps (Fig. 3). The NTDs form the outer “turret” portion of each pentamer; NTD helices 1, 2, and 3 are positioned to allow the intrapentamer NTD-NTD contacts that stabilize the lattice. The CTDs form the “floor” of the structure and mediate interpentamer contacts through the CTD-CTD dimer interface at helix 9. Each CTD is offset, lying beneath the NTD of the next adjacent subunit; this allows for the helix 4-to-helix 8/11 NTD-CTD interactions unique to the mature lattice (20, 21, 40). As we do not see any additional density in the CA-SP map that can be assigned to the SP moiety, we infer that it is disordered.

Fig 3.

Fitting of CA domains into CA-SP T=1 particle density. (A) RSV CA-NTD and CA-CTD atomic models were fitted into the CA-SP T=1 reconstruction independently, as rigid bodies. (B) The modeled CA-SP pentamer (magenta) is compared to the mature CA pentamer structure (cyan). The two structures are shown superimposed both from the top and in side view.

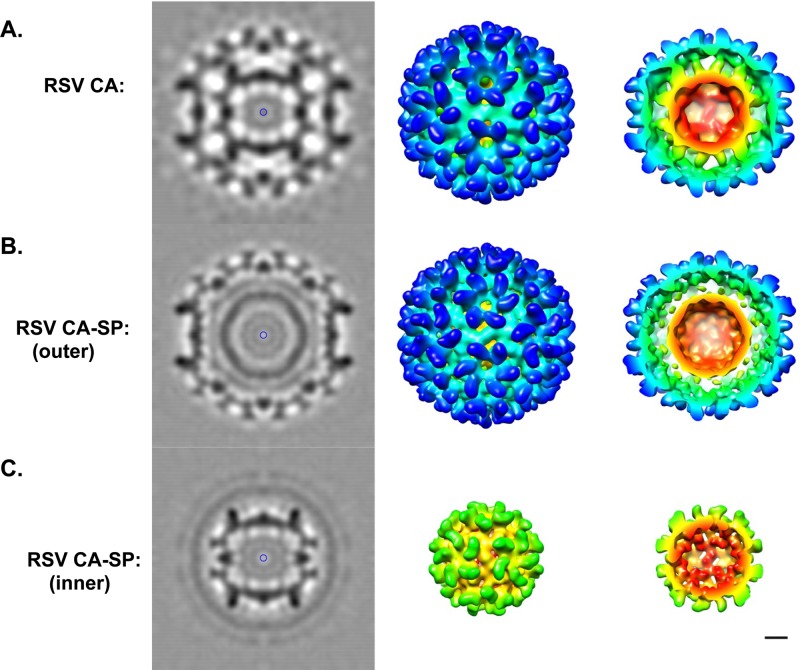

We also reconstructed the larger, double-layered, CA-SP particles (Fig. 4). As this data set was smaller (n ∼ 600), the resolution reached was lower (18 Å). Both nested capsids (T=1, inner, and T=3, outer) are indistinguishable from the corresponding CA particles. However, the analysis had to proceed differently in this case. With CA, the two nested capsids are in register with their vertices aligned (Fig. 4A). Such is not the case for CA-SP. When the latter particles are aligned for reconstruction on the outer T=3 capsid, the inner T=1 capsid appears as a smooth-surfaced spherical shell (Fig. 4B), indicating that the T=1 capsids were randomly and inconsistently oriented. Conversely, when the alignment focused on the T=1 particle, its icosahedral nature was expressed in the reconstruction and it was the outer T=3 shell that appeared smooth and featureless (Fig. 4C).

Fig 4.

Reconstruction of RSV T=3 capsids. (A) RSV CA T=3 reconstruction (10), EMDB code 1862, shown here to allow direct comparison with the CA-SP T=3 reconstruction. Note the in-register alignment of the outer T=3 shell and the inner T=1 shell. (B) The CA-SP T=3 reconstruction obtained using the entire particle for alignment and orientation determination. The outer T=3 shell is resolved clearly, but the inner particle is smooth and featureless, indicative of inconsistent orientation assignments. (C) Reconstruction obtained using only the inner portion of the T=3 particle, i.e., inside a radius of 110 Å, to determine orientations. In it, the T=1 icosahedral structure becomes evident, while the T=3 outer shell becomes smooth and featureless. Bar, 5 nm.

To account for this lack of registration, we infer that the presence of the SP peptide on the interior surface of the outer capsid (where the C terminus of CA resides, according to docking experiments) interferes with its registration with the inner capsid. In fact, the site of contact for the inner capsid on the interior of the outer capsid includes a portion of the major homology region (MHR) (Fig. 1 and reference 10). These data suggest that SP, although disordered, is in close proximity to the MHR on the inner surface of the assembled CA shell. However, the fact that we see very few empty T=3 capsids implies that there is still sufficient interaction between the two shells for the inner capsid to nucleate assembly of the outer capsid.

We conclude from these experiments that excision of SP is not required for CA to assemble directly into the mature lattice, i.e., the uncleaved protein CA-SP (p25) is not fundamentally incapable of assembly, and that SP is disordered in these capsids.

Morphology of PF-46396-inhibited virions.

In the following experiments, we used cryo-electron tomography to assess the effects on HIV-1 virions of the recently described maturation inhibitor PF-46396 (46, 53) and of the CA5 mutation in which cleavage at the CA-SP1 site is blocked by two amino acid substitutions (26). Control virions were produced by transfection of 293T or COS cells and then isolated from the culture supernatant for visualization. To produce immature virions, cells were transfected with the PR-deficient mutant HIV-1 clone pNL4-3/PR− (48). To determine the phenotype of the pNL4-3-derived Gag mutant CA5, a similar procedure was followed. To investigate the effects of PF-46396 on virion morphology, the compound was added to cells during virus production.

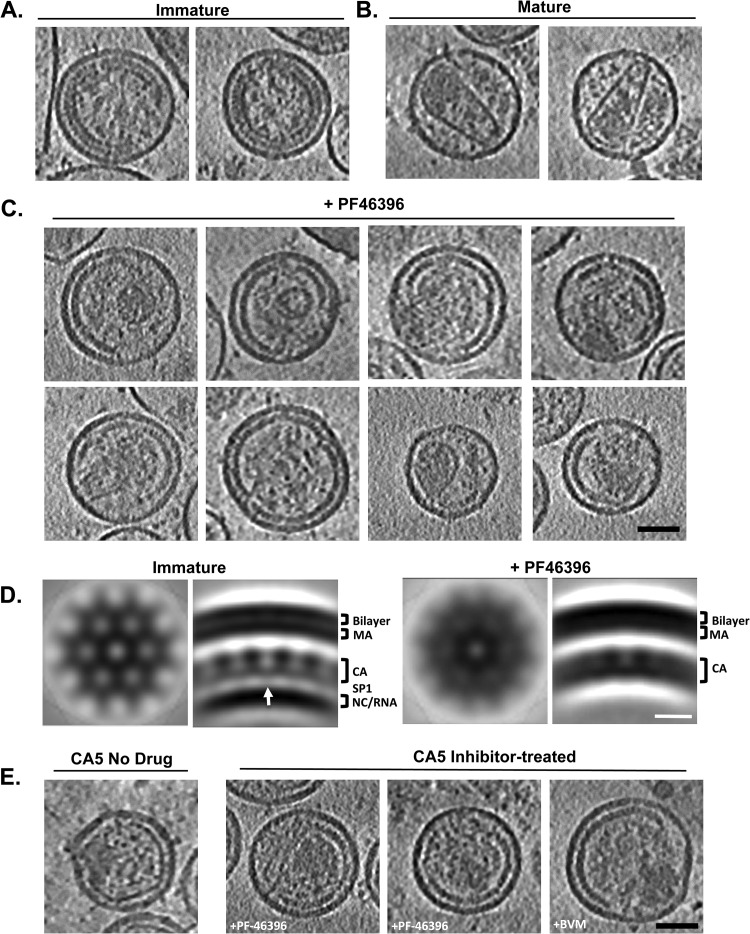

Our results indicated that PF-46396 has effects on virion morphology generally similar to those of BVM (36). While this compound has no discernible effect on the assembly of immature virions (Fig. 5A) (46), maturation is largely disrupted and characteristic structures are present in the resulting particles (Fig. 5C). They include a thick-walled partial shell lining the viral membrane and smaller, irregular and/or acentric, core-like structure(s). For reference, mature virions produced in the absence of PF-46396 are shown in Fig. 5B. Of note, some PF-46396-inhibited virions contain conical cores (e.g., Fig. 5C, lower left). These particles are discussed further below.

Fig 5.

Cryo-ET of HIV-1 particles generated in the presence of PF-46396 and BVM. (A to C) Gallery of central slices from tomographic reconstructions of HIV-1 virions: immature (A), mature wild type (B), and wild type treated with the PF-46396 inhibitor (C). Bar (C), 50 nm. (D) Slices from subtomogram averages of immature virion (at left) and WT plus PF-46396 (at right) reveal consistent 8-nm hexagonal lattice patterns in the CA layer. Views from above (left) and radial views (right) are shown for each average. The white arrow points to the faint densities that connect the CA layer to the underlying NC-plus-RNA layer. Bar, 10 nm. (E) Gallery of central slices through CA5 particle reconstructions, with drug treatment as indicated. Bar, 50 nm.

We measured the extent of the partial shell in PF-46396-treated virions to compare its completeness to the immature shell of PR− virions. The shell in treated virions is considerably less extensive than the immature lattice, covering an average of 46% of the virion surface (n = 15) versus an average of 75% for the immature lattice (n = 15). The PF-46396-treated shell is also more variable in size than the immature shell, as indicated by a standard deviation (SD) of ±21% versus ±10% for PR− particles.

Subtomogram averaging was performed to enhance the partial shell structure typical of PF-46396-treated virions. It revealed, as with BVM (36), a honeycomb-like lattice (Fig. 5D, right panels) that resembles the immature lattice (Fig. 5D, left panels) but has markedly lower contrast, suggesting that either this lattice is less well ordered or it represents a somewhat different conformation.

Production of conical cores.

As noted above, we also observed differences between virions produced in the presence of BVM and those produced in the presence of PF-46396; the most striking is in the incidence of virions that have conical cores. About one in eight PF-46396-treated particles contains a conical core, whereas with BVM we see only half as many (Table 1; Fig. 6). This distinction correlates with their respective efficiencies in blocking cleavage at the CA-SP1 site. With wild-type (WT) HIV-1, which has >95% mature CA, we observed ∼ 69% of the virions to have conical cores. Under the conditions used, PF-46396 is ∼50% effective at blocking CA-SP1 cleavage (46), and the percentage of particles with conical cores drops to 13%. BVM-treated particles contain about 25% of mature CA (36, 46), and only 6% of them have conical cores. The CA5 mutant, with <1% mature CA (26, 36), produced no particles with complete conical cores in our data set (n = 145).

Table 1.

Conical core formation is correlated with CA maturationa

| Virus sample (n) | Fraction of mature CA (%) | % particles with core type |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Conical | Irregular | ||

| WT (141) | >95 | 69 | 20 |

| WT + PF-46396 (197) | 50 | 13 | 76 |

| WT + BVM (145) | 25 | 6 | 91 |

| CA5 (145) | <1 | 0 | 85 |

Individual particles were scored for core morphology. To be counted, conical cores had to appear closed and filled, i.e., having typical levels of internal electron density. Cores that failed these criteria were scored as irregular. The rate of successful conical core formation correlates directly with the fraction of fully mature CA (i.e., lacking SP1) in the sample type. Percentages do not add up to 100, as some particles contain no identifiable core-like structures.

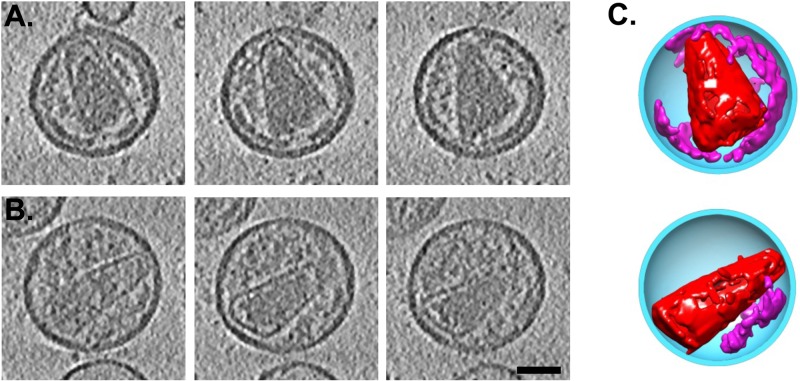

Fig 6.

Conical cores in PF-46396-inhibited virions. (A and B) Three tomographic slices at different Z-heights through two WT-plus-PF-46396 virions containing conical cores. Both conical cores and immature-like lattice remnants are visible in each case. The remnant is large in virion A and small (at bottom right) in virion B. (C) Three-dimensional segmented cutaway models of the virions shown in panels A and B. The viral membrane/matrix protein layers are colored blue, conical cores are in red, and immature-like lattice remnants are in magenta. Bar, 50 nm.

Thus, the higher incidence of conical cores in PF-46396-inhibited virions (versus BVM-inhibited virions) correlates with a larger percentage of mature CA protein. This trend continues with the complete absence of conical cores in CA5 and essentially zero cleavage of CA-SP1.

We also observed some PF-46396-inhibited virions to contain both a conical core and a sizable remnant of an immature-like shell (Fig. 6A). We have not detected such remnants in any mature WT virions. In fact, most of the PF-46396-inhibited virions with conical cores also contained some such remnants, with the latter varying widely in size (compare Fig. 6A and B). Three-dimensional modeling of these particles (Fig. 6C) suggested that the two structures (conical core and shell remnant) are separate and do not merge, even lacking consistently identifiable contact points. This lack of connectivity makes it unlikely that conical cores emerge displacively from the immature lattice and more likely that they assemble de novo.

Inhibitor treatment of the CA5 mutant.

Although CA5 virions have in common with BVM-inhibited virions that cleavage at the CA-SP1 site is blocked in both cases (more efficiently so for CA5), they have distinct morphologies. In particular, CA5 virions have a peripheral shell that tracks or comes close to tracking the viral envelope and is thinner, i.e., more mature-like, than the immature-like shell of BVM-inhibited virions (e.g., Fig. 5E, left). This observation led to the idea that BVM has a stabilizing effect on the immature lattice (36). We have now tested this hypothesis directly by analyzing CA5 particles produced in the presence of BVM or PF-46396 and find that these compounds do indeed have the effect of retaining the CA lattice in an immature-like state (Fig. 5E, right).

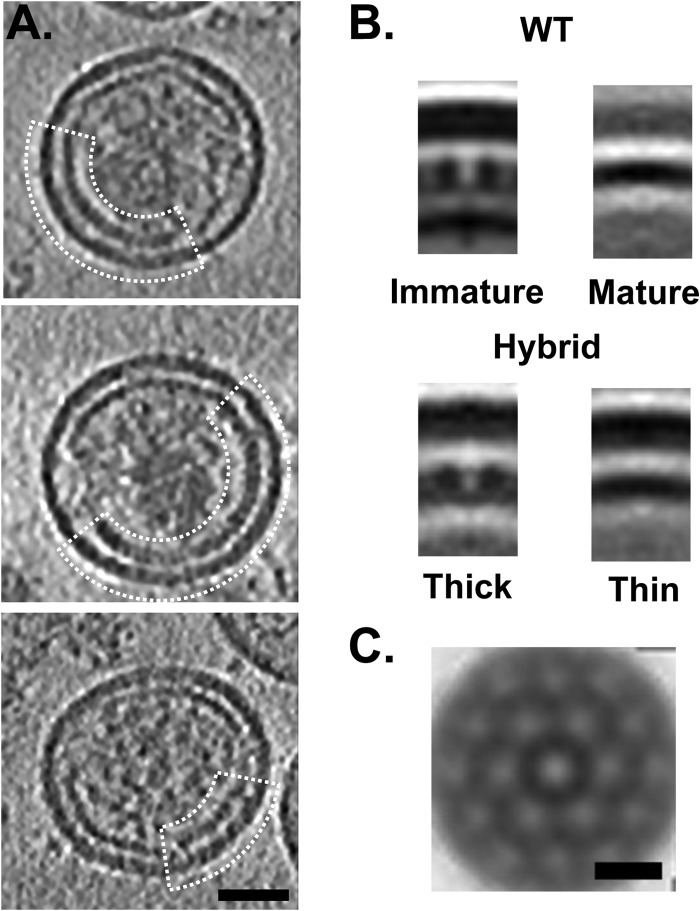

With the less potent inhibitor, PF-46396, we observed that approximately 50% of CA5 particles contain “hybrid” peripheral shells (Fig. 7A), i.e., they have patches that are in both the “thin” and the “thick” conformations. Unlike the conical cores described above (Fig. 6), the hybrid shells are clearly composed of two distinct lattice types continuously merging within the same shell. Subtomogram averaging and radial profile measurement reveal that the thick conformation resembles a remnant of the immature CA lattice complete with the same honeycomb motif symmetry (Fig. 7B and C); the thin conformation is more like the mature core shell (Fig. 7B and 8).

Fig 7.

Gag mutant CA5 hybrid shell. (A) Central slices through cryo-electron tomograms of three CA5-plus-PF-46396 particles. In each case, a quasispherical shell is evident, with separate regions exhibiting two distinct conformations: thin mature-like and thicker immature-like (the latter regions are delineated by cages). Bar, 50 nm. (B) Radial sections through the averaged subtomograms of the two hybrid shell morphologies compared to WT immature and mature core shell accentuate the difference in CA layer thickness between the two regions. This implies a change of CA organization/conformation. (C) Spherical section through the averaged “thick” CA5 lattice. Bar, 10 nm.

Fig 8.

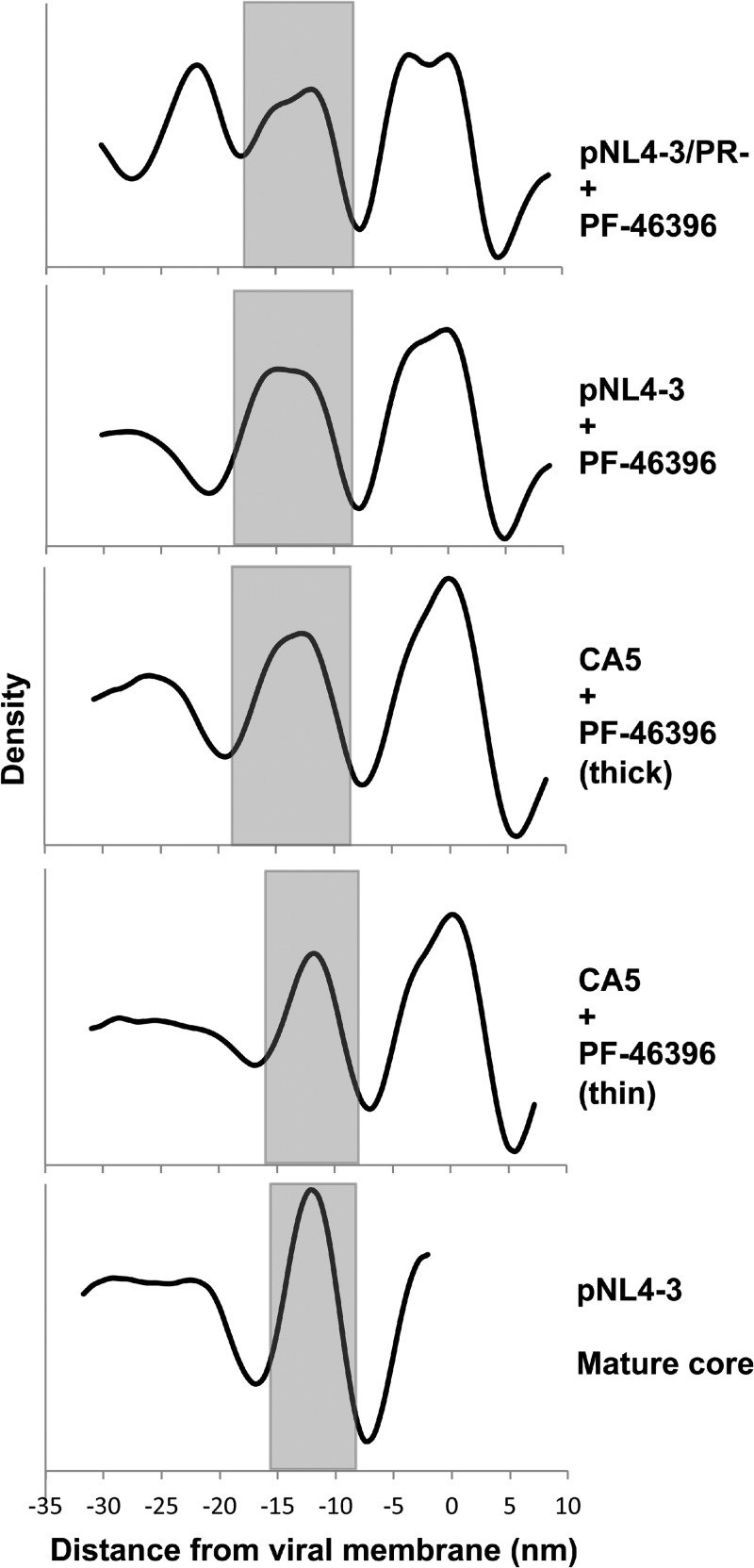

Radial density profiles. The profiles were calculated by appropriately averaging aligned subtomograms from each specimen, combining data from multiple particles: top, protease deficient plus maturation inhibitor (immature); second, wild type plus maturation inhibitor; third, CA5 mutant plus maturation inhibitor (thick shell); fourth, CA5 mutant plus maturation inhibitor (thin shell); bottom, mature core shell. Radial profiles are shown aligned according to the viral membrane for all samples except the mature core, in which case the layer of core density (CA) was used for this purpose. The CA layers are shaded to allow comparison.

DISCUSSION

RSV CA-SP can assemble directly into a mature-like lattice.

At the outset, we considered two possibilities for the mechanism of retrovirus maturation and its inhibition. The first one posits that CA-SP/SP1, the immediate precursor of mature CA, is basically incapable of assembling. However, the alacrity with which CA-SP assembles in vitro into capsids rules out this option, at least for RSV. Referring now to the HIV-1 system, the second possibility envisages that CA-SP1 is assembly competent but inhibitors prevent its release from the immature-like lattice to allow de novo assembly of a mature core. As discussed further below, the bulk of current evidence supports this scenario.

It appears that the spacer peptide is capable of adopting (at least) two conformations. Assuming that it contributes the densities that connect the CA layer to the NC layer in the immature Gag shell (white arrow in Fig. 5D) (12, 13, 36), it should have a definite fold, as disordered protein would be expected to smear out on averaging. These densities have, in fact, been proposed to represent hexameric α-helical bundles (13, 54) that contribute to stabilizing the shell. Other evidence has also been adduced in support of the spacer peptide having an α-helical conformation under certain conditions (31; V. M. Vogt, personal communication). On the other hand, in CA-SP capsids, the SP peptide is disordered, to judge from the RSV reconstructions (Fig. 2 and 3). Moreover, SP and SP1 have appeared as disordered regions in other structural studies (15, 18, 55). Thus, their conformation appears to be context dependent. It is plausible that SP1 retains its helical conformation in the maturing virion until the final CA-SP1 cleavage event, after which CA and SP1 are shed from the immature-like shell. CA enters the soluble pool from which the mature capsid assembles. The conformation of shed SP1 has not been determined, but its (short) length suggests that it may switch to a disordered state. In this scenario, the primary role of CA-SP1 cleavage is to release CA subunits from the immature shell. However, it remains possible that a formation of uncleaved CA-SP may serve as a nucleation point for assembly of the mature core (M. England, J. Purdy, and R. C. Craven, unpublished data).

The inhibitory mechanism of PF-46396 resembles that of BVM, albeit with reduced potency.

The data supporting this conclusion are summarized in Fig. 5 and Table 1. We conclude that both inhibitors bind to assembled Gag, near enough to the CA-SP1 cleavage site to prevent the PR from accessing that site (46), and also stabilizing the CA lattice in an immature-like conformation.

Our cryotomograms depict two states of the CA lattice, distinguished primarily by their thickness. The thick-walled (∼10-nm; Table 2) spherical shell underlying the viral membrane, characteristic of immature virions, has a honeycomb morphology with a periodicity of 8 nm. Beneath it and connected by the SP1 linker is the dense layer of NC plus bound RNA (Fig. 5D, left-hand pair). The thin-walled (∼7.5-nm; Table 2) lattice characteristic of mature capsids—notably, of bona fide conical capsids (Fig. 7B)—does not reveal any substructure at the current resolution. However, it should represent the hexagonal lattice with a repeat of 9.2 nm that has been visualized in assemblies of CA (11, 14, 16) and which is represented—albeit with tighter curvature and more coassembled pentamers—in the T=3 shell of our in vitro-assembled RSV capsids (Fig. 4A and B). In other kinds of particles (i.e., other than WT mature and WT immature), we observe CA-containing shells that resemble these two reference structures in thickness (Table 2; Fig. 8). Pending more detailed structural information, we refer to them as mature-like and immature-like, respectively.

Table 2.

Shell thicknessesa

| Virus sample | Drug | CA shell thickness (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| WT | None | 8.0 ± 0.5 |

| BVM/PF-46396 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | |

| PR− | None/BVM/PF-46396 | 9.4 ± 0.2 |

| CA5 | None | 8.0 ± 0.3 |

| Thick | BVM/PF-46396 | 10.1 ± 1 |

| Thin | PF-46396 | 8.0 ± 0.2 |

The thicknesses of the CA-containing layers were measured from the radial density profiles of averaged subtomograms for each sample type (data not shown) and are listed for comparison. Immature and immature-like shells are 9.5 to 11.0 nm thick, while mature and mature-like shells are significantly thinner, at 7.5 to 8.0 nm. The quoted experimental uncertainties represent the differences between determinations made from different subsets of data, calculated independently, for each sample type.

In CA5 virions, the CA-SP1 lattice undergoes a displacive transformation toward a mature-like state.

In CA5 virions, the Gag molecules that were initially arrayed in spherical immature shells have undergone all cleavages except at the CA-SP1 site. The resulting shells are still approximately spherical, but the spacing between the CA shell and the MA layer is larger and more variable, with an average center-to-center spacing of 9.1 nm ± 2.3 nm (SD) in CA5 virions versus 6.6 nm ± 1.1 nm in PR− virions (Fig. 5E, left; Fig. 7A, top), reflecting the fact that cleavage between MA and CA has decoupled the two structures. Their thickness and overall shape suggest that they have transformed displacively into a mature-like conformation. Supporting this interpretation is the fact that in CA5 shells, we see straight segments meeting at an angle which is suggestive of vertex formation, a property of mature lattices (6).

We surmise that the mature-like lattice represents a lower free energy state than the immature-like lattice and that retention of the SP1 spacer in CA5 shells is unable to restrain the immature-like lattice indefinitely from converting to the mature-like state. Eventually, this conversion initiates at one or more lattice sites and propagates outwards, creating patches that grow and eventually merge to cover the entire shell. In other words, under these conditions, a maturation-like transition takes place in a displacive manner.

However, we did not observe any CA5 virions with conical cores, implying that this displacive maturation does not generate such structures. Moreover, CA5 virions are noninfectious (26). In a recent study, Monroe et al. (21) used hydrogen-deuterium (H/D) exchange mass spectrometry to compare CA5 virions with mature and immature virions, concluding that CA5 CA-SP1 fails to form the NTD-CTD interaction characteristic of the mature CA lattice and that the CA5 lattice is essentially immature-like (see Fig. 7 in reference 21). In contrast, our results show directly that the CA5 lattice is markedly thinner than the immature-like lattice (Table 2) and indistinguishable from mature capsids in this respect. However, the H/D data support the possibility that the “mature-like” CA5 lattice is not identical with the mature WT one.

PF-46396 and BVM bind directly to the immature CA lattice.

When CA5 virions are produced in the presence of either inhibitor, the CA shell remains thick walled, i.e., immature-like: all over, in the case of BVM (Fig. 5E, right), and to various degrees, in the case of PF-46396 (Fig. 7A). We infer that the inhibitors impede displacive transition of the lattice, presumably by binding directly to it, as has been suggested elsewhere (3, 56), and that BVM is more efficient in this regard. With PF-46396, the clamp-like effect of inhibitor binding is less stringent and displacive transition can initiate at one or more sites on the immature-like lattice and propagate outwards in a wave-like manner, creating the thin-walled patches that we observe. In the absence of inhibitor, this transition goes to completion. With BVM, it cannot get started.

Similar, locally nucleated wave-like lattice transformations have been observed in bacteriophage T4 capsid (57) and in the envelope glycoproteins of flavivirus (58); in both systems, they are part of a displacive maturation pathway.

Coexistence of conical capsids and fragments of immature-like shells.

Interpretation of data on retrovirus maturation is complicated by polymorphism: not all virions assemble a capsid, a few assemble more than one capsid, and the capsids produced exhibit a variety of geometries. Another issue concerns the pools of unassembled CA. On average, only about half of the HIV-1 CA molecules become assembled into capsids (38, 40), and that fraction varies quite widely from virion to virion for RSV (43) and probably also for HIV-1. With maturation inhibitors, the fraction of CA cleaved from CA-SP1, which averages 25% for BVM and 50% for PF-43496 (46), may also vary from particle to particle. We envisage that the fraction that is cleaved to CA enters the soluble pool, where it is available for capsid assembly. It is not clear how large that pool must be in order for assembly to be initiated, but the paucity of observed assembly intermediates suggests that, once initiated, the process is rapid and continues until the capsid is completed or until the pool falls below a critical concentration.

In rare cases, PF-46396-treated virions that have both a conical core and a remnant of immature-like shell show a cone that appears not to be closed at the wide end (e.g., Fig. 6A). This observation coincides with the proposal of Briggs et al. that conical capsid assembly initiates at the thin end and completes when the growing wide end encounters the MA layer on the other side of the maturing virion (39).

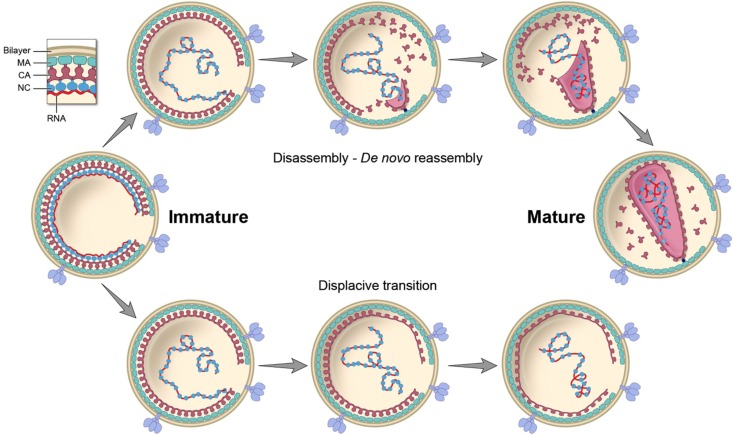

Taken together with earlier data, the present observations suggest that two pathways can lead CA into a mature-like lattice structure (Fig. 9). In nascent wild-type HIV-1 virions, the final cleavage releases CA subunits into the soluble pool from which de novo assembly of the conical core is triggered stochastically, leading to the creation of an infectious virion. Alternatively, in CA5 virions, the endpoint of cleavage leaves a spherical shell of CA-SP1 that is initially in an immature-like conformation but, in the absence of a maturation inhibitor, is metastable and may undergo a displacive transition into a mature-like spherical shell.

Fig 9.

Retroviral maturation pathways. Two routes are considered for transition from the immature virion to the mature virion or mature-like viral particle. In the “disassembly-de novo reassembly” model, the immature lattice is thought to dissolve following complete proteolysis of Gag, releasing CA building blocks, possibly dimers, into a soluble pool. From this pool, a certain proportion (about 50%) of the building blocks reassemble into a mature capsid. In the “displacive transition” model, as appears to occur with the CA5 mutant, the immature-like CA-SP1 shell remains intact but patches of it undergo an in situ remodeling to a thinner mature-like state. Eventually, these patches merge. In a version of this model that would produce conical cores, a portion of initially spherical shell would have to be pinched off, coupled with the lattice maturation event. Our data support the “disassembly-reassembly” model as the likely path to productive core formation and support the idea that cleavage of SP/SP1 from CA serves primarily to release CA from an immature-like lattice into the soluble pool.

In the presence of either maturation inhibitor, a smaller pool of soluble CA—on average, 25% (BVM) to 50% (PF-46396) of the total—is produced and assembles into the capsid-related structures seen in these virions, in some cases including complete conical cores (Table 1; Fig. 6). The compounds stabilize the remaining uncleaved CA-SP1 so that it remains assembled in an immature-like shell, commensurately reduced in size. This account explains the simultaneous presence of both a conical capsid and a partial immature-like shell in some maturation-inhibited virions and not in mature WT virions. It also explains why the incidence of conical core formation depends on the amount of CA released from CA-SP1, which also correlates with the infectivity of the resulting virions (35, 36, 46) and, inversely, to the potency of a given maturation inhibitor. It is also consistent with the previously proposed mechanism of action for small-molecule maturation inhibitors (35, 37, 46) and helps to explain how CA-SP1 cleavage inhibition and immature lattice stabilization are related.

In conclusion, these observations support the views that maturation occurs by a disassembly-reassembly pathway and that a closed filled conical capsid is required for HIV-1 infectivity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. C. Winkler for support with resources for cryo-electron tomography, S. D. Ablan for technical assistance, J. Purdy for initial characterization of RSV CA-SP protein, and H.-G. Kräusslich for providing the HIV-1 CA5 mutant.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of NIAMS and NCI, by the NIH Intramural AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program, by NIH CA100322, NIH training grant 2 T32 CA60395, and by the PA Department of Health (R.C.C.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 October 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Wlodawer A, Vondrasek J. 1998. Inhibitors of HIV-1 protease: a major success of structure-assisted drug design. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 27:249–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adamson CS, Salzwedel K, Freed EO. 2009. Virus maturation as a new HIV-1 therapeutic target. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 13:895–908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou J, Huang L, Hachey DL, Chen CH, Aiken C. 2005. Inhibition of HIV-1 maturation via drug association with the viral Gag protein in immature HIV-1 particles. J. Biol. Chem. 280:42149–42155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganser-Pornillos BK, Yeager M, Sundquist WI. 2008. The structural biology of HIV assembly. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18:203–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freed EO. 1998. HIV-1 gag proteins: diverse functions in the virus life cycle. Virology 251:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heymann JB, Butan C, Winkler DC, Craven RC, Steven AC. 2008. Irregular and semi-regular polyhedral models for Rous sarcoma virus cores. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 9:197–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganser-Pornillos BK, von Schwedler UK, Stray KM, Aiken C, Sundquist WI. 2004. Assembly properties of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 CA protein. J. Virol. 78:2545–2552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganser BK, Li S, Klishko VY, Finch JT, Sundquist WI. 1999. Assembly and analysis of conical models for the HIV-1 core. Science 283:80–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pornillos O, Ganser-Pornillos BK, Yeager M. 2011. Atomic-level modelling of the HIV capsid. Nature 469:424–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardone G, Purdy JG, Cheng N, Craven RC, Steven AC. 2009. Visualization of a missing link in retrovirus capsid assembly. Nature 457:694–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S, Hill CP, Sundquist WI, Finch JT. 2000. Image reconstructions of helical assemblies of the HIV-1 CA protein. Nature 407:409–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briggs JA, Riches JD, Glass B, Bartonova V, Zanetti G, Kräusslich HG. 2009. Structure and assembly of immature HIV. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:11090–11095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright ER, Schooler JB, Ding HJ, Kieffer C, Fillmore C, Sundquist WI, Jensen GJ. 2007. Electron cryotomography of immature HIV-1 virions reveals the structure of the CA and SP1 Gag shells. EMBO J. 26:2218–2226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganser-Pornillos BK, Cheng A, Yeager M. 2007. Structure of full-length HIV-1 CA: a model for the mature capsid lattice. Cell 131:70–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campos-Olivas R, Newman JL, Summers MF. 2000. Solution structure and dynamics of the Rous sarcoma virus capsid protein and comparison with capsid proteins of other retroviruses. J. Mol. Biol. 296:633–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pornillos O, Ganser-Pornillos BK, Kelly BN, Hua Y, Whitby FG, Stout CD, Sundquist WI, Hill CP, Yeager M. 2009. X-ray structures of the hexameric building block of the HIV capsid. Cell 137:1282–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mortuza GB, Haire LF, Stevens A, Smerdon SJ, Stoye JP, Taylor IA. 2004. High-resolution structure of a retroviral capsid hexameric amino-terminal domain. Nature 431:481–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kingston RL, Fitzon-Ostendorp T, Eisenmesser EZ, Schatz GW, Vogt VM, Post CB, Rossmann MG. 2000. Structure and self-association of the Rous sarcoma virus capsid protein. Structure 8:617–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macek P, Chmelik J, Krizova I, Kaderavek P, Padrta P, Zidek L, Wildova M, Hadravova R, Chaloupkova R, Pichova I, Ruml T, Rumlova M, Sklenar V. 2009. NMR structure of the N-terminal domain of capsid protein from the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus. J. Mol. Biol. 392:100–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanman J, Lam TT, Barnes S, Sakalian M, Emmett MR, Marshall AG, Prevelige PE., Jr 2003. Identification of novel interactions in HIV-1 capsid protein assembly by high-resolution mass spectrometry. J. Mol. Biol. 325:759–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monroe EB, Kang S, Kyere SK, Li R, Prevelige PE., Jr 2010. Hydrogen/deuterium exchange analysis of HIV-1 capsid assembly and maturation. Structure 18:1483–1491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Byeon IJ, Meng X, Jung J, Zhao G, Yang R, Ahn J, Shi J, Concel J, Aiken C, Zhang P, Gronenborn AM. 2009. Structural convergence between cryo-EM and NMR reveals intersubunit interactions critical for HIV-1 capsid function. Cell 139:780–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng X, Zhao G, Yufenyuy E, Ke D, Ning J, Delucia M, Ahn J, Gronenborn AM, Aiken C, Zhang P. 2012. Protease cleavage leads to formation of mature trimer interface in HIV-1 capsid. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002886. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bharat TA, Davey NE, Ulbrich P, Riches JD, de Marco A, Rumlova M, Sachse C, Ruml T, Briggs JA. 2012. Structure of the immature retroviral capsid at 8 Å resolution by cryo-electron microscopy. Nature 487:385–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swanstrom R, Wills JW. 1997. Synthesis, assembly, and processing of viral proteins, p 263–334 In Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus H. (ed), Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Woodbury, NY: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiegers K, Rutter G, Kottler H, Tessmer U, Hohenberg H, Krausslich HG. 1998. Sequential steps in human immunodeficiency virus particle maturation revealed by alterations of individual Gag polyprotein cleavage sites. J. Virol. 72:2846–2854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pettit SC, Moody MD, Wehbie RS, Kaplan AH, Nantermet PV, Klein CA, Swanstrom R. 1994. The p2 domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag regulates sequential proteolytic processing and is required to produce fully infectious virions. J. Virol. 68:8017–8027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SK, Potempa M, Kolli M, Ozen A, Schiffer CA, Swanstrom R. 2012. Context surrounding processing sites is crucial in determining cleavage rate of a subset of processing sites in HIV-1 Gag and Gag-Pro-Pol polyprotein precursors by viral protease. J. Biol. Chem. 287:13279–13290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Marco A, Muller B, Glass B, Riches JD, Kräusslich HG, Briggs JA. 2010. Structural analysis of HIV-1 maturation using cryo-electron tomography. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001215. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adamson CS, Freed EO. 2007. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly, release, and maturation. Adv. Pharmacol. 55:347–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Datta SA, Temeselew LG, Crist RM, Soheilian F, Kamata A, Mirro J, Harvin D, Nagashima K, Cachau RE, Rein A. 2011. On the role of the SP1 domain in HIV-1 particle assembly: a molecular switch? J. Virol. 85:4111–4121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Accola MA, Hoglund S, Göttlinger HG. 1998. A putative alpha-helical structure which overlaps the capsid-p2 boundary in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag precursor is crucial for viral particle assembly. J. Virol. 72:2072–2078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keller PW, Johnson MC, Vogt VM. 2008. Mutations in the spacer peptide and adjoining sequences in Rous sarcoma virus Gag lead to tubular budding. J. Virol. 82:6788–6797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krausslich HG, Facke M, Heuser AM, Konvalinka J, Zentgraf H. 1995. The spacer peptide between human immunodeficiency virus capsid and nucleocapsid proteins is essential for ordered assembly and viral infectivity. J. Virol. 69:3407–3419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li F, Goila-Gaur R, Salzwedel K, Kilgore NR, Reddick M, Matallana C, Castillo A, Zoumplis D, Martin DE, Orenstein JM, Allaway GP, Freed EO, Wild CT. 2003. PA-457: a potent HIV inhibitor that disrupts core condensation by targeting a late step in Gag processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:13555–13560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keller PW, Adamson CS, Heymann JB, Freed EO, Steven AC. 2011. HIV-1 maturation inhibitor bevirimat stabilizes the immature Gag lattice. J. Virol. 85:1420–1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou J, Yuan X, Dismuke D, Forshey BM, Lundquist C, Lee KH, Aiken C, Chen CH. 2004. Small-molecule inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by specific targeting of the final step of virion maturation. J. Virol. 78:922–929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Briggs JA, Simon MN, Gross I, Kräusslich HG, Fuller SD, Vogt VM, Johnson MC. 2004. The stoichiometry of Gag protein in HIV-1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:672–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Briggs JA, Grunewald K, Glass B, Forster F, Kräusslich HG, Fuller SD. 2006. The mechanism of HIV-1 core assembly: insights from three-dimensional reconstructions of authentic virions. Structure 14:15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lanman J, Lam TT, Emmett MR, Marshall AG, Sakalian M, Prevelige PE., Jr 2004. Key interactions in HIV-1 maturation identified by hydrogen-deuterium exchange. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:676–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin AJ, Nossal R. 1993. Topological mechanisms involved in the formation of clathrin-coated vesicles. Biophys. J. 65:1523–1537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Purdy JG, Flanagan JM, Ropson IJ, Craven RC. 2009. Retroviral capsid assembly: a role for the CA dimer in initiation. J. Mol. Biol. 389:438–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Butan C, Winkler DC, Heymann JB, Craven RC, Steven AC. 2008. RSV capsid polymorphism correlates with polymerization efficiency and envelope glycoprotein content: implications that nucleation controls morphogenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 376:1168–1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heymann JB, Belnap DM. 2007. Bsoft: image processing and molecular modeling for electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 157:3–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. 2004. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25:1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waki K, Durell SR, Soheilian F, Nagashima K, Butler SL, Freed EO. 2012. Structural and functional insights into the HIV-1 maturation inhibitor binding pocket. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002997. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adachi A, Gendelman HE, Koenig S, Folks T, Willey R, Rabson A, Martin MA. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 59:284–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang M, Orenstein JM, Martin MA, Freed EO. 1995. p6Gag is required for particle production from full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 molecular clones expressing protease. J. Virol. 69:6810–6818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heymann JB, Cardone G, Winkler DC, Steven AC. 2008. Computational resources for cryo-electron tomography in Bsoft. J. Struct. Biol. 161:232–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cardone G, Grünewald K, Steven AC. 2005. A resolution criterion for electron tomography based on cross-validation. J. Struct. Biol. 151:117–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Purdy JG, Flanagan JM, Ropson IJ, Rennoll-Bankert KE, Craven RC. 2008. Critical role of conserved hydrophobic residues within the major homology region in mature retroviral capsid assembly. J. Virol. 82:5951–5961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Purdy J. 2009. To assemble, or not to assemble: the initiation of retroviral capsid assembly. Ph.D. dissertation Pennsylvania State University, Hershey, PA [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blair WS, Cao J, Fok-Seang J, Griffin P, Isaacson J, Jackson RL, Murray E, Patick AK, Peng Q, Perros M, Pickford C, Wu H, Butler SL. 2009. New small-molecule inhibitor class targeting human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virion maturation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:5080–5087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morellet N, Druillennec S, Lenoir C, Bouaziz S, Roques BP. 2005. Helical structure determined by NMR of the HIV-1 (345–392)Gag sequence, surrounding p2: implications for particle assembly and RNA packaging. Protein Sci. 14:375–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gamble TR, Yoo S, Vajdos FF, von Schwedler UK, Worthylake DK, Wang H, McCutcheon JP, Sundquist WI, Hill CP. 1997. Structure of the carboxyl-terminal dimerization domain of the HIV-1 capsid protein. Science 278:849–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nguyen AT, Feasley CL, Jackson KW, Nitz TJ, Salzwedel K, Air GM, Sakalian M. 2011. The prototype HIV-1 maturation inhibitor, bevirimat, binds to the CA-SP1 cleavage site in immature Gag particles. Retrovirology 8:101. 10.1186/1742-4690-8-101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steven AC, Carrascosa JL. 1979. Proteolytic cleavage and structural transformation: their relationship in bacteriophage T4 capsid maturation. J. Supramol. Struct. 10:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Plevka P, Battisti AJ, Junjhon J, Winkler DC, Holdaway HA, Keelapang P, Sittisombut N, Kuhn RJ, Steven AC, Rossmann MG. 2011. Maturation of flaviviruses starts from one or more icosahedrally independent nucleation centres. EMBO Rep. 12:602–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]