Abstract

Fluorescent proteins are routinely employed as reporters in retroviral vectors. Here, we demonstrate that transduction with retroviral vectors carrying a tandem-dimer Tomato (TdTom) reporter produces two distinct fluorescent cell populations following template jumping due to a single nucleotide polymorphism between the first and second Tomato genes. Template jumping also occurs between repeated sequences in the Tomato and green fluorescent protein (GFP) genes. Thus, proper interpretation of the fluorescence intensity of transduced cells requires caution.

TEXT

Fluorescent reporter proteins are frequently used in retroviral vectors for identifying transduced cells (1–4). The fluorescent proteins green fluorescent protein (GFP) and tandem-dimer tomato (TdTomato) are particularly useful because they are very amenable to detection by flow cytometry. These two proteins are derivatives of genes acquired from organisms of the genera Aequorea (5) and Discosoma, but as a consequence of its development as a molecular tool, TdTomato (as well as many other fluorescent proteins) contains short segments of GFP sequence at its N and C termini (6–8). We have observed that transduction of cells with retroviral vectors containing TdTomato results in two distinct populations with either bright or dim fluorescence intensities, as detected by fluorescent light microscopy (Fig. 1A) and flow cytometry (Fig. 1B). This phenomenon was observed using both gammaretroviral and lentiviral vectors and was not dependent on the multiplicity of infection (MOI) of transduction (data not shown).

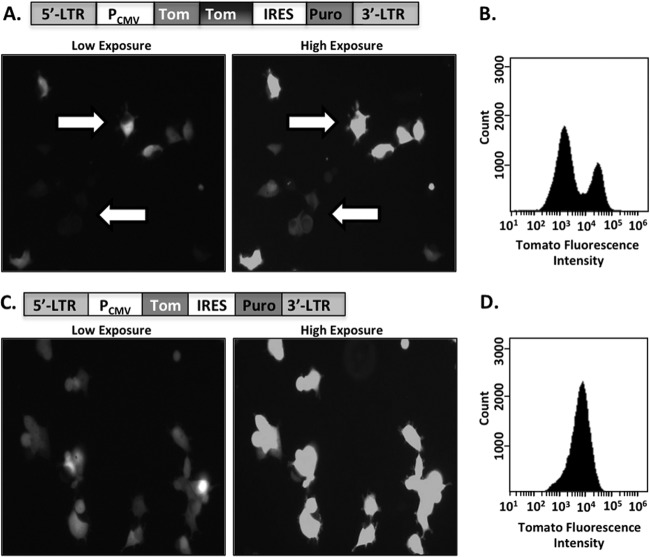

Fig 1.

Transduction using retroviral vectors carrying a TdTomato reporter resulted in two cellular populations with distinct fluorescence intensities. (A and B) TdTomato was cloned into the murine leukemia virus (MLV) transfer vector pQCXIP (Clontech) and used to generate nonclonal stable cell lines from HEK 293FT cells. (A) Fluorescent images of the stable cell line transduced with TdTomato; white arrows highlight bright (top) and dim (bottom) cells. LTR, long terminal repeat; CMV, cytomegalovirus promoter. (B) Total cell populations depicted in panel A were analyzed using flow cytometry to confirm the presence of two distinct fluorescent populations. (C and D) Parallel analysis of cells expressing a monomeric Tomato gene.

Retroviral recombination occurs during reverse transcription of the retroviral genome due to template switching at stretches of homologous nucleotide sequence (9, 10). Recombination also occurs frequently in retroviral vectors containing short stretches of repeated nucleotide sequences (11–14), such as the repeated sequences at the N and C termini of TdTomato. To determine if the bimodal distribution of the distinct fluorescent populations arose from one of the copies of Tomato being deleted due to template jumping, we generated a retroviral vector with only the first copy of the Tomato gene (Fig. 1C). This construct produced a single population of transduced cells (Fig. 1C and D) whose fluorescence was distinctly brighter than the dim fluorescence of the population produced from the TdTomato vectors depicted in Fig. 1A. Thus, the dimly fluorescent population did not appear to arise simply from the deletion of one copy of the TdTomato gene as a result of recombination.

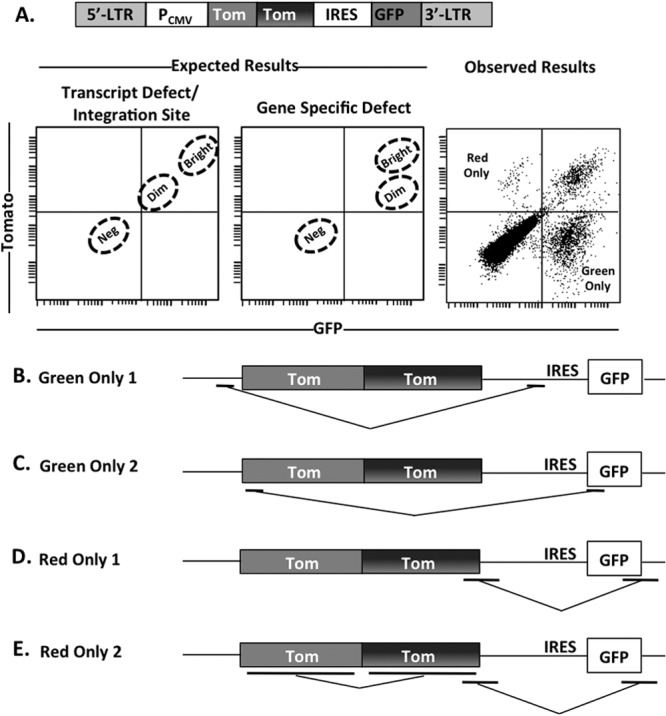

We next wished to determine if the dim Tomato fluorescent population resulted from alterations in the Tomato gene itself or, alternatively, from variations in Tomato mRNA expression. To address this, we generated a TdTomato vector that also expressed GFP from the downstream internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) in place of the puromycin resistance gene (Fig. 2A). If the dim Tomato fluorescence resulted from differences in mRNA expression, we expected the dim Tomato-expressing cells to also express dim GFP (Fig. 2A, left panel). If the dim Tomato fluorescence resulted from alterations in the Tomato gene itself, we expected the dim Tomato-expressing cells to display normal GFP expression levels (Fig. 2A, center panel). Surprisingly, we did not observe dominant cell populations of either of these phenotypes but instead observed populations with various combinations of Tomato and GFP fluorescence, including cells expressing only GFP and cells expressing only Tomato (Fig. 2A, right panel). To determine the nature of these singly fluorescent populations, we sorted the fluorescent green-only and red-only cells by flow cytometry and then recovered the reporter sequences by PCR and sequenced them. The results showed that differential fluorescent populations resulted from template jumping between various locations in the vector where short stretches of homologous sequence were present (Fig. 2B to E). Notably, template jumping occurred between the short identical sequences at both the N-terminal and C-terminal sequences in GFP and Tomato (Fig. 2C to E). This result implies that template jumping is very prevalent in this system, as might be expected from the principles of viral reverse transcription, but fails to fully explain the nature of the dimly fluorescent Tomato population.

Fig 2.

Retroviral recombination occurs between distinct fluorescent proteins. (A) Schematic of double-labeled reporter. The left and center flow plot panels depict the distributions of transduced cells that would be expected if the dimness were due to a transcriptional defect and a gene-specific defect, respectively. The right flow plot depicts observed flow cytometry results following transduction of HEK 293FT cells. Neg, negative. (B to E) Red-only and green-only cells were sorted by flow cytometry. DNA was extracted from sorted cells, and the region between the CMV promoter and the end of GFP was PCR amplified and sequenced. Control PCRs were performed on the parent plasmid to ensure that the observed changes were not caused by PCR. Template-jumping results observed within populations of green-only (B and C) and red-only (D and E) populations are shown. Underlined regions indicate areas of homologous nucleotide sequence.

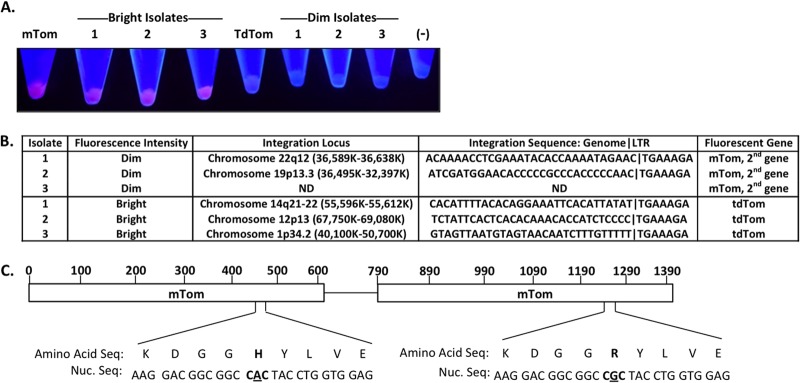

To determine the cause of the bright and dim Tomato fluorescent populations, we performed single-cell isolations by limiting dilution of bright and dim red fluorescent cells from the population in Fig. 1A and expanded these clonal populations (Fig. 3A). It is well established that retroviral integration often occurs near regions of chromatin associated with active transcription (15–19). To rule out genomic integration as a contributing factor for the differential levels of fluorescence intensity observed in Fig. 1A, we analyzed brightly and dimly fluorescent single-cell isolates for TdTomato integration position within the genome. Genomic DNA was extracted from the six populations, and integration locations were determined using the genome walker technique (Clontech) for five of these populations. In this small data set (5 integration sites), there was no obvious correlation between integration site and gene brightness (Fig. 3B). Next, we recovered the Tomato sequence of the bright and dim populations to assess any alterations in the Tomato gene. All three of the dim Tomato populations expressed a single copy of Tomato; notably, in each case it was the second copy of the Tomato gene (Fig. 3B). Some versions of the TdTomato gene have a single nucleotide polymorphism in which an adenine is substituted with a guanine, subsequently resulting in a histidine-to-arginine mutation within the second Tomato gene (Fig. 3C). This polymorphism arose from a PCR mutation during the creation of TdTomato but was initially overlooked because it did not appear to alter the phenotype of Tomato (N. Sharer, personal communication).

Fig 3.

Fluorescence intensity is independent of TdTom genomic integration sites. (A) Cell pellets of bright and dimly fluorescent single-cell isolates from HEK 293FT cells transduced with MLV carrying the TdTom reporter. Cells transduced with the tandem-dimer tomato (TdTom) and monomeric-tomato (mTom) reporters are included for reference, along with nontransduced HEK 293FT cells (−). (B) Genomic DNA from the bright and dimly fluorescent single-cell isolates depicted in panel A was extracted and analyzed to determine genomic integration sites and Tomato gene alteration. (C) Schematic representation of the nucleotide and corresponding amino acid polymorphism between the first and second Tomato genes within the TdTomato reporter.

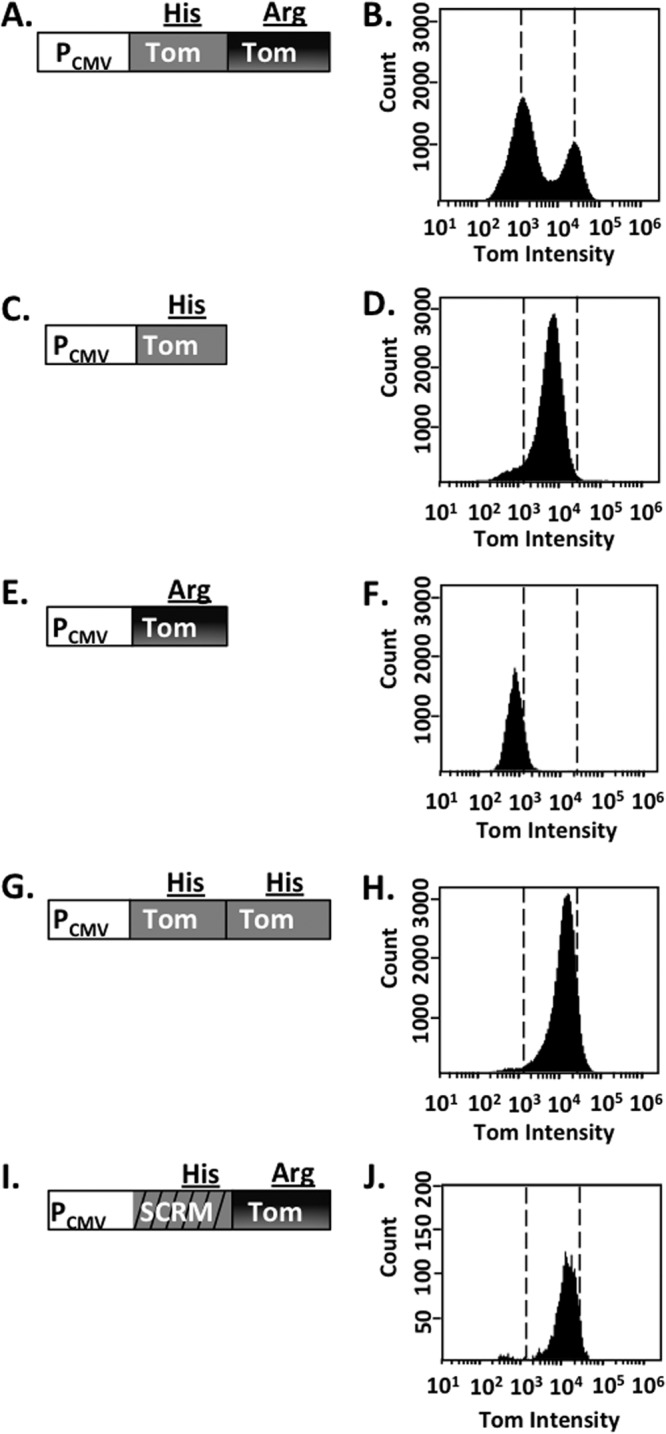

To confirm that the polymorphism was responsible for the Tomato dimness, we generated a retroviral vector with only the second copy of Tomato (Fig. 4E). This construct indeed produced dim red transduced cells (Fig. 4F). A parallel vector that expressed TdTomato without the polymorphism did not change the brightness of Tomato, suggesting that the polymorphism is detrimental only if expressed alone (Fig. 4G and H). Finally, because sequence homology directly influences retroviral recombination (13, 20), we also tested if the dim red population could be eliminated by reducing the sequence homology between the two copies of Tomato. To accomplish this, we produced a TdTomato gene where the codons in the first copy of Tomato were changed such that the amino acid sequence was not changed but the nucleotide homology with the second copy of Tomato was dramatically reduced (Fig. 4I and J). This vector produced only bright red cells.

Fig 4.

Bimodal fluorescence intensity of the TdTom reporter occurs as a result of a single nucleotide polymorphism difference between the TdTom genes. HEK 293FT cells were infected with MLV carrying the modified retroviral Tomato reporters depicted in the left column. The resulting cell populations were analyzed by flow cytometry to assess fluorescent cell populations and are depicted in the histograms. Dashed vertical lines in the right column highlight the fluorescence intensity of the bright and dimly fluorescent cell populations present following transduction with virus carrying the TdTomato reporter.

In summary, we have shown that retroviral recombination among and between fluorescent genes can lead to spurious phenotypes. Although template jumping is a well-known phenomenon in retroviruses and retroviral vectors, short stretches of sequence homology such as those found in fluorescent proteins are not always taken into consideration when vectors are designed. Lack of attention to possible template jumping could lead to misinterpretation of results when assaying for selective loss of expression of a retrovirus-associated gene (21, 22). This potential problem can be prevented by eliminating all repeated sequences, for example, by scrambling the codon sequence in the regions where amino acid sequences are repeated (Fig. 4J).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants AI73098 and GM110776.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 September 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Persons DA, Allay AJ, Allay ER, Smeyne RJ, Ashmun RA, Sorrentino BP, Nienhuis AW. 1997. Retroviral-mediated transfer of the green fluorescent protein gene into murine hematopoietic cells facilitates scoring and selection of transduced progenitors in vitro and identification of genetically modified cells in vivo. Blood 90:1777–1786 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein D, Indraccolo S, Von Rombs K, Amadori A, Salmons B, Günzburg WH. 1997. Rapid identification of viable retrovirus-transduced cells using the green fluorescent protein as a marker. Gene Ther. 4:1256–1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welsh S, Kay SA. 1997. Reporter gene expression for monitoring gene transfer. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 8:617–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng L, Fu J, Tsukamoto A, Hawley RG. 1996. Use of green fluorescent protein variants to monitor gene transfer and expression in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 14:606–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsien RY. 1998. The green fluorescent protein. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67:509–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matz MV, Fradkov AF, Labas YA, Savitsky AP, Zaraisky AG, Markelov ML, Lukyanov SA. 1999. Fluorescent proteins from nonbioluminescent Anthozoa species. Nat. Biotechnol. 17:969–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaner NC, Campbell RE, Steinbach PA, Giepmans BN, Palmer AE, Tsien RY. 2004. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:1567–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell RE, Tour O, Palmer AE, Steinbach PA, Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. 2002. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:7877–7882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onafuwa-Nuga A, Telesnitsky A. 2009. The remarkable frequency of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genetic recombination. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 73:451–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galetto R, Negroni M. 2005. Mechanistic features of recombination in HIV. AIDS Rev. 7:92–102 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delviks-Frankenberry K, Galli A, Nikolaitchik O, Mens H, Pathak VK, Hu WS. 2011. Mechanisms and factors that influence high frequency retroviral recombination. Viruses 3:1650–1680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li T, Zhang J. 2000. Determination of the frequency of retroviral recombination between two identical sequences within a provirus. J. Virol. 74:7646–7650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu WS, Bowman E, Delviks KA, Pathak VK. 1997. Homologous recombination occurs in a distinct retroviral subpopulation and exhibits high negative interference. J. Virol. 71:6028–6036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li T, Zheng J. 2001. Retroviral recombination is temperature dependent. J. Gen. Virol. 82:1359–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu X, Li Y, Crise B, Burgess SM. 2003. Transcription start regions in the human genome are favored targets for MLV integration. Science 300:1749–1751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewinski MK, Yamashita M, Emerman M, Ciuffi A, Marshall H, Crawford G, Collins F, Shinn P, Leipzig J, Hannenhalli S, Berry C, Ecker JR, Bushman FD. 2006. Retroviral DNA integration: viral and cellular determinants of target-site selection. PLoS Pathog. 2:e60. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Felice B, Cattoglio C, Cittaro D, Testa A, Miccio A, Ferrari G, Luzi L, Recchia A, Mavilio F. 2009. Transcription factor binding sites are genetic determinants of retroviral integration in the human genome. PLoS One 4:e4571. 10.1371/journal.pone.0004571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bushman FD. 2003. Targeting survival: integration site selection by retroviruses and LTR-retrotransposons. Cell 115:135–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schröder RW, Shinn P, Chen H, Berry C, Ecker JR, Bushman F. 2002. HIV-1 integration in the human genome favors active genes and local hotspots. Cell 110:521–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.An W, Telesnitsky A. 2002. Effects of varying sequence similarity on the frequency of repeat deletion during reverse transcription of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vector. J. Virol. 76:7897–7902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dahabieh MS, Ooms M, Simon V, Sadowski I. 2013. A doubly fluorescent HIV-1 reporter shows that the majority of integrated HIV-1 is latent shortly after infection. J. Virol. 87:4716–4727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter CC, Onafuwa-Nuga A, McNamara LA, Riddell J, Bixby D, Savona MR, Collins KL. 2010. HIV-1 infects multipotent progenitor cells causing cell death and establishing latent cellular reservoirs. Nat. Med. 16:446–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]