Abstract

The development of a safe and efficient dengue vaccine represents a global challenge in public health. Chimeric dengue viruses (DENV) based on an attenuated flavivirus have been well developed as vaccine candidates by using reverse genetics. In this study, based on the full-length infectious cDNA clone of the well-known Japanese encephalitis virus live vaccine strain SA14-14-2 as a backbone, a novel chimeric dengue virus (named ChinDENV) was rationally designed and constructed by replacement with the premembrane and envelope genes of dengue 2 virus. The recovered chimeric virus showed growth and plaque properties similar to those of the parental DENV in mammalian and mosquito cells. ChinDENV was highly attenuated in mice, and no viremia was induced in rhesus monkeys upon subcutaneous inoculation. ChinDENV retained its genetic stability and attenuation phenotype after serial 15 passages in cultured cells. A single immunization with various doses of ChinDENV elicited strong neutralizing antibodies in a dose-dependent manner. When vaccinated monkeys were challenged with wild-type DENV, all animals except one that received the lower dose were protected against the development of viremia. Furthermore, immunization with ChinDENV conferred efficient cross protection against lethal JEV challenge in mice in association with robust cellular immunity induced by the replicating nonstructural proteins. Taken together, the results of this preclinical study well demonstrate the great potential of ChinDENV for further development as a dengue vaccine candidate, and this kind of chimeric flavivirus based on JE vaccine virus represents a powerful tool to deliver foreign antigens.

INTRODUCTION

Dengue has emerged as the most important mosquito-borne viral disease worldwide during the past decades. The spectrum of illness ranges from asymptomatic infections and dengue fever (DF) to severe and potentially life-threatening dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS). Dengue is transmitted to humans by infected Aedes mosquitoes and maintained by a human-mosquito-human cycle of transmission in nature. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that over 50 million infections occur annually, with 25,000 to 50,000 cases of DHF, and there are over 2.5 billion persons at risk of infection in more than 100 countries throughout the tropical and subtropical regions (1). In fact, the global health burden of dengue could be much higher than previously thought, and a recent modeling work revealed that 390 million people around the world were infected with this mosquito-borne virus in 2010 (2). Currently, there is neither a licensed vaccine nor an effective and specific antiviral therapy for dengue. The four serotypes of dengue virus (DENV-1 to DENV-4) belong to the Flavivirus genus in the family Flaviviridae together with Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), Yellow fever virus (YFV), West Nile virus (WNV), and tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV). Flaviviruses have an ∼11-kb single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome that contains a single open reading frame (ORF) flanked by two untranslated regions (5′ and 3′ UTRs). The ORF encodes a single polyprotein, which is proteolytically processed into three structural proteins (C, prM, and E) and seven nonstructural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5). The E glycoprotein is the principal antigen inducing protective immunity against virus infection, and it requires the coexpression of prM to acquire its native conformation. All the nonstructural proteins are actively involved in viral genome replication, translation, and regulation. Due to the high degree of similarity among flaviviruses in genome organization, replication, and translation strategy, viable chimeric viruses have been rationally designed and generated by interchanging various genes among different flaviviruses (3–6) by using reverse genetics. This kind of chimeric approach has been widely utilized in dengue vaccine development (6–11). The most advanced product of this kind is the ChimeriVax-Dengue (CYD) vaccine developed by Sanofi Pasteur, which was created based on the yellow fever vaccine strain 17D (YF-17D) (reviewed in reference 12). The protective efficacy of this tetravalent dengue vaccine in a phase 2b trial in Thailand was recently reported (13), and large-scale phase 3 trials are ongoing (14). Another chimeric dengue vaccine under clinical trial is developed based on the known attenuated DENV-2 strain PDK53 (6, 10, 15, 16). Additionally, recombinant DENV-4 with a deletion of 30 nucleotides in the 3′ UTR (DEN4Δ30) has been successfully utilized as a backbone for chimeric dengue vaccine development (11, 17–20). Generally, the well-characterized attenuated flaviviruses represent good candidates as a genetic backbone for chimeric dengue vaccine development. A licensed Japanese encephalitis virus live vaccine (strain SA14-14-2) has been widely used in China and other Asian countries, including India, South Korea, Sri Lanka, and Nepal (21). Large-scale vaccination in more than 300 million children has shown an excellent safety profile, genetic stability, and remarkable effectiveness and efficacy for SA14-14-2 (22–26). These attractive properties make JEV strain SA14-14-2 an ideal candidate as a genetic backbone for chimeric dengue vaccine development. In this work, we report the early development of a chimeric dengue vaccine using JEV vaccine strain SA14-14-2 as the genetic backbone. The resulting chimera is highly attenuated, immunogenic, and protective against either JEV or DENV challenge in mice or nonhuman primates, demonstrating great potential for further development. The use of the JEV SA14-14-2 genetic background to deliver protective antigens could be an efficient method for the development of vaccines against other flaviviruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

BHK-21 (baby hamster kidney) and Vero (African green monkey kidney) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin (100 U/ml)-streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Aedes albopictus C6/36 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen) and 10% FBS. Primary hamster kidney (PHK) cells were produced at the Chengdu Institute of Biological Products under the good manufacturing practice (GMP) workshop and cultured in MEM alpha supplemented with 10% FBS. All cell lines were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2, except for C6/36 cells, which were maintained at 28°C. DENV-2 strain D2-43 (GenBank accession no. AF204178) was isolated from the acute-phase serum of a DF patient in Guangxi Province, China, in 1987 (27). DENV-2 strain TSV01 (GenBank accession no. AY037116) was recovered from the infectious clone and prepared from culture supernatants of infected C6/36 cells. JEV strain SX-06 was isolated from a mosquito in Shanxi Province, China, in 2006, and the 50% lethal dose (LD50) was measured in groups of 4-week-old BALB/c mice accordingly. JEV vaccine strain SA14-14-2 (GenBank no. D90195) was provided by the Chengdu Institute of Biological Products. Virus titers were determined by standard plaque assay on BHK-21 cells, and virus stocks were stored in aliquots at −80°C until used.

Genetic construction of the JEV/DENV chimera.

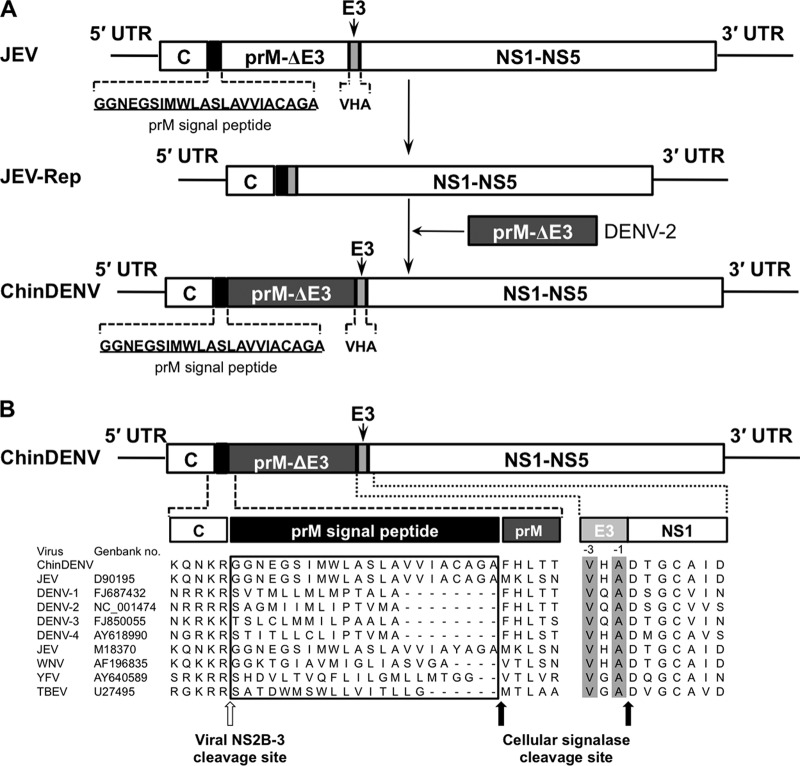

All plasmids were constructed using standard molecular biology protocols and confirmed by enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing. The DNA construct of the chimera is shown in Fig. 1A.

Fig 1.

Design and construction of a genomic-length chimeric JEV/DENV-2 (ChinDENV) cDNA clone. (A) Strategy for the construction of the infectious cDNA clone of ChinDENV. The JEV prM signal peptide (blank box) is underlined. The C-terminal 3 amino acids of JEV E protein (E3, gray box) and the prM-E of DENV-2 lacking the C-terminal 3 amino acids of the E protein (dark gray box) are indicated. (B) Alignment of flavivirus amino acid sequences around the C-prM and E-NS1 junctions. The prM signal peptides are boxed. The last and antepenultimate C-terminal amino acids of flavivirus E proteins are highlighted in gray. Sites of cleavage by the viral NS2B-3 protease and signal peptidase are indicated by the open arrow and solid arrows, respectively.

Genetic construction of the full-length infectious clone of JEV has been described by Ye et al. (28). Briefly, plasmid pACYC-Linker was first created from plasmid pACYC177 (Fermentas) and plasmid pSP64 (Promega). Further details about the construction of pACYC-Linker and primers used in this study are available from the authors on request. The entire genome of JEV strain SA14-14-2 was cloned in plasmid pACYC-Linker. Cloning sites were engineered to permit replacement of the entire pre-M and E coding sequences of JEV for the corresponding sequences of DENV-2 strain D2-43. Sites for posttranslational cleavage of the capsid and pre-M proteins and of the E and NS1 proteins were preserved (Fig. 1A). The resulting plasmid contained the full-length cDNA of the JEV/DENV-2 chimera, named pChinDENV.

Transcription and transfection.

Plasmid pChinDENV was linearized with XhoI and used as a template for SP6 RNA polymerase transcription in the presence of an m7GpppA cap analog. In vitro transcription was done using the RiboMAX Large Scale Production System (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocols. The yield and integrity of transcripts were analyzed by gel electrophoresis under nondenaturing conditions. RNA transcripts (5 μg) were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) into BHK-21 cells grown in 60-mm-diameter culture dishes. Supernatants were then harvested at about day 5 posttransfection, when typical cytopathic effects (CPE) were observed, and clarified by low-speed centrifugation. Working virus stocks (named ChinDENV) were prepared by amplification of the transfection harvest for one passage on Vero or PHK cells and stored in aliquots at −80°C until use. Virus titers were determined by standard plaque assay on BHK-21 cells.

Nucleotide sequencing.

Viral RNA was isolated using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen), and the genome cDNA was obtained by reverse transcription (RT) using SuperScript III (Invitrogen). For determination of consensus sequence, PCR products were directly sequenced in both directions using virus-specific primers. The 5′ and 3′ termini were sequenced using 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE). Sequence fragments were assembled into a consensus sequence with DNA STAR software, version 7.0.

Growth curves.

Growth curves were done by infecting confluent BHK-21, C6/36, Vero, or PHK cells in a 12-well plate at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01. The inoculum was removed after 1 h of adsorption, and culture medium was added. Cell supernatants were collected at successive 24-h intervals postinfection. Yields of virus in each sample were then quantitated by plaque assay on BHK-21 cells. Briefly, BHK-21 cells in 12-well plates were infected with a 10-fold serial dilution of viruses. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h with gentle rocking every 15 min. The supernatant was removed, and cells were overlaid with 1% low-melting-point agarose (Promega) in DMEM containing 2% FBS. After further incubation at 37°C for 4 days, the cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and stained with 0.2% crystal violet to visualize the plaques.

IFA.

Indirect immunofluorescence assays (IFA) were performed as follows. Briefly, confluent BHK-21 cells grown in 60-mm-diameter culture dishes containing a 1-cm2 coverslip inside were infected with viruses at an MOI of 0.01. At 48 h postinfection, the coverslips containing infected cells were removed and directly used for IFA analysis. The cells seeded on the coverslip were fixed with ice-cold acetone and incubated with primary antibodies (monoclonal antibody [MAb] 4AD5F5D5D6for JEV E protein, MAb 2B8 for DENV E protein [27], or JN1 for JEV NS1 protein [Abcam]) or serum of mice at 37°C for 1 h. Cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) in PBS for 30 min at 37°C. Fluorescent cells were examined using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus).

Genetic-stability assay.

The chimeric virus ChinDENV was serially passaged in PHK cells at an MOI of 0.01. The complete genome sequence and plaque phenotypes of ChinDENV virus of passages 3, 9, and 15 were assessed as described above.

Neutralization assay.

Neutralizing antibody titers were determined by a constant virus-serum dilution 50% plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT50). Briefly, a 1:10 dilution of serum was prepared in DMEM containing 2% FBS and then heat inactivated for 30 min at 56°C. Serial 2-fold dilutions of inactivated sera were mixed with equal volumes of DENV-2 in DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS to yield a mixture containing approximately 250 PFU of virus/ml. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, 200-μl volumes of the virus-antibody mixtures were added to wells of 12-well plates containing confluent monolayers of BHK-21 cells. The concentration of infectious virus was determined using the plaque assay described above. The endpoint neutralization titer was calculated by the method of Reed and Muench (29).

Mouse experiments.

Research involving animals was approved by and carried out in strict accordance with the guidelines of the Experimental Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology. For neurovirulence tests, groups of 2-day-old and 4-week-old BALB/c mice were inoculated by the intracerebral (i.c.) route with 10-fold dilutions of ChinDENV and its parent viruses, respectively. Animals were monitored for 21 days after inoculation. Any mice found in a moribund condition were euthanatized and scored as dead. Virus doses inducing a 50% mortality rate were calculated using the method of Reed and Muench. Average survival times (AST) were calculated for animals that succumbed to infection.

Immunogenicity was assessed by subcutaneous (s.c.) inoculation of various doses of ChinDENV virus diluted in DMEM plus 2% FBS into 4-week-old female BALB/c mice. The mice were bled by tail vein puncture 1 day prior to and periodically after immunizations at 2, 4, and 6 weeks postimmunization. The sera were stored at −20°C for determination of IgG antibodies by IFA and neutralizing antibodies by PRNT50.

Additionally, groups of 4-week-old female BALB/c mice (n = 10) were first immunized with 6.85 log10 PFU of JEV live vaccine SA14-14-2 or PBS by the s.c. route, and then 14 days later, all the animals were immunized with the same dose of ChinDENV. At 28 and 42 days after primary immunization, titers of neutralization antibody against DENV-2 in sera from each animal were measured by using standard PRNT as described above.

For the protection assay, heat-inactivated sera from mice immunized with ChinDENV were mixed with equal volumes of DENV-2 (D2-43 strain) diluted in DMEM supplemented to yield a mixture containing approximately 500 PFU (∼100 LD50s) of virus/ml. The virus-antibody mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 1 h and then injected by the i.c. route into groups of 2-day-old BALB/c suckling mice (n = 9). Animals were then monitored for 15 days after inoculation.

JEV challenge experiments.

For the cross protection study, groups of 4-week-old BALB/c mice were inoculated by the s.c. route with 105 PFU of ChinDENV. Equal doses of JEV (SA14-14-2) and PBS were set as controls. Four weeks after the initial vaccination, all the mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) challenged with 105 PFU (10 LD50s) of JEV SX-06 as described in the relevant figure legends. Signs of illness and death were monitored for at least 15 days. Groups of three virus-immunized or PBS-immunized mice were anesthetized, and blood was collected by retro-orbital bleeding and subjected to neutralizing antibody titration by plaque assay. Spleens were taken after cervical dislocation for evaluation of cellular immune response (described below).

Cellular immune responses.

Cellular immune responses were assessed in splenocytes by the gamma interferon (IFN-γ) or interleukin 2 (IL-2) enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) mouse set (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, spleens excised from anesthetized animals were thawed and washed with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS). The cells were then centrifuged at room temperature at 2,500 rpm for 15 min without braking, followed by two washes with HBSS. Then, the cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS and diluted to a working concentration of 100 million cells per ml. For ELISPOT analysis, 10 million cells per well were seeded with the appropriate antigen stimulation in 96-well tissue culture dishes coated with 5 mg/ml of IFN-γ or IL-2 capture monoclonal antibody. Nonstimulated and concanavalin A (5 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich)-stimulated cells were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. The cells were then cultured for 36 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Plates were washed, and biotinylated anti-mouse IFN-γ or IL-2 antibody was added to each well and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Thereafter, the plates were washed and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (streptavidin-HRP). Finally, AEC substrate solution (BD Biosciences) was added and spots were counted with an ImmunoSpot analyzer (Cellular Technology Ltd.). Assay results are expressed as the value obtained by the following: (number of spots in experimental well − number of spots in medium control)/107 cells.

Monkey experiments.

All experimental procedures involving rhesus monkeys were performed under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia by trained technicians, and all efforts were made to ameliorate the welfare and to minimize animal suffering in accordance with the recommendations in The Use of Non-Human Primates in Research (30).

(i) Immunization and challenge of rhesus monkeys.

Fourteen monkeys, weighing 3.4 to 5.0 kg, were prescreened for negativity for antibodies against DENV by IFA. Animals were randomly divided into four groups and immunized s.c. in the deltoid region with 0.5 ml of ChinDENV containing 3.0, 4.0, or 5.0 log10 PFU or were sham inoculated with PBS. Blood was collected daily for 10 days to detect viremia. Blood samples for neutralizing-antibody tests were taken before immunization (day −1) and then on days 15, 20, 30, 50, and 63 postimmunization. On day 64 postimmunization, all the immunized monkeys plus unimmunized controls were challenged by s.c. inoculation of 0.5 ml containing 5 log10 PFU of DENV-2 (TSV-01 strain). For the following 9 days, blood was collected for determination of viremia. Neutralizing-antibody levels in serum were measured by neutralization assay described above on days 15 and 30 postchallenge.

(ii) Viremia determination.

Viremia in monkeys was measured by quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR). Virus titer was expressed in log10 PFU/ml. The number of PFU in serum detected was calculated by generating a standard curve from 10-fold dilutions of RNA isolated from a serum sample containing a known number of PFU, the titer of which was determined by plaque assay on BHK-21 cells as described above. Briefly, viral genomic RNA was extracted from 200 μl of serum or an equal volume of sample serum by using the PureLinkTM RNA minikit (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was eluted in 50 μl of RNase-free water, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C until use. The primers (5′-CAGGCTATGGCACTGTCACGAT-3′ and 5′-CCATTTGCAGCAACACCATCTC-3′) and probe (5′-CTCTCCGAGAACGGGCCTCGACTTCAA-3′) were designed using the program Primer ExpressTM (PE Applied Biosystems, USA). The target region for the assays was based on the E protein region of the genome of DENV-2. A TaqMan assay probe was 5′ labeled with the reporter dye 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) and labeled at the 3′ end with the quencher dye 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA). qRT-PCR was performed by using a One Step PrimeScript RT-PCR kit (TaKaRa, Japan). The 25-μl reaction mixtures were set up with a 0.5 μM concentration of each primer (qDVEF and qDVER, respectively), 0.25 μM probe, and 5 μl of RNA. Thermocycling programs consisted of 42°C for 5 min, 95°C for 10 s, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 30 s.

Statistic analysis.

For survival analysis, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed by a log rank test using standard GraphPad Prism software, version 5.0.

RESULTS

Engineering and characterization of the chimeric ChinDENV.

To assess the potential of the infectious cDNA clone derived from JEV SA14-14-2 to serve as a vector for vaccine development, we engineered a chimeric DENV-2 (termed ChinDENV) cDNA clone containing the structural genes of DENV-2 strain D2-43, a representative strain of the Asia 1 genotype, using a subgenomic replicon of JEV SA14-14-2 (31) as the genetic backbone. ChinDENV retained the prM signal peptide of JEV as well as the last three amino acids at the terminus of the E protein to ensure efficient cleavage at the C-prM junction and E-NS1 junction, respectively (Fig. 1).

Total RNA transcripts encoding ChinDENV were transfected in BHK-21 cells, and immunostaining assays with specific monoclonal antibodies characterized the recovered ChinDENV expressing the E protein of DENV-2 and NS1 protein of JEV (Fig. 2A). The recovered ChinDENV caused typical cytopathic effects in BHK-21 cells almost the same as parental DENV, producing a homogeneous population of plaques which were ≈0.5 mm in diameter, approximately half the size of those of parental JEV (Fig. 2B). RT-PCR analysis and full-genome sequencing confirmed that the prM-E gene of DENV-2 was successfully engineered into the genome of JEV SA14-14-2 as expected.

Fig 2.

In vitro characterization of ChinDENV. (A) Immunostaining of JEV-, ChinDENV-, DENV-2-, or mock-infected BHK cells with specific anti-JEV E, DENV-2 E, and JEV NS1 antibodies. Cells were infected with viruses at an MOI of 0.01. At 48 h postinfection, JEV or DENV-2 antigen was detected with monoclonal antibody 4AD5F5D5D6 (for JEV E protein), 2B8 (for DENV-2 E protein), and JN1 (for JEV NS1 protein). (B) Plaque morphology of JEV, ChinDENV, and DENV-2 on BHK-21 cells grown in 6-well plates were infected with a 10-fold serial dilution of viruses. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Supernatant was removed and cells were overlaid with 1% low-melting-point agarose in DMEM containing 2% FBS. After further incubation at 37°C for 4 days, the cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and stained with 0.2% crystal violet to visualize the plaques. (C) Plaque morphology of ChinDENV passaged in PHK cells. The chimeric virus ChinDENV was passaged in PHK cells up to 15 times. The plaque phenotypes of passage 3, 9, and 15 viruses were examined on BHK-21 cells 4 days after infection by plaque assay. (D) Growth curves of the chimera ChinDENV and parental viruses JEV and DENV-2 in cell culture. Monolayers of Vero, C6/36, and PHK cells were infected with the indicated viruses at an MOI of 0.01. At each time point, the media were removed and virus titers in cell culture media were determined on BHK-21 cells by plaque assay.

Full-genome sequencing showed that there were seven nucleotide substitutions between ChinDENV and parental DENV-2 in the prM-E genes, and four of them resulted in amino acid changes, including prM-28 Gly to Gln, prM-55 Leu to Phe, prM135 Met to Ile, and E402 Phe to Ile. Within the UTRs and capsid protein as well as nonstructural protein genes, there were four nucleotide differences (nucleotide positions 473, 3200, 3465, and 10843) between ChinDENV and JEV SA14-14-2, all of which were silent and did not cause amino acid substitutions.

Subsequently, the growth efficiencies of ChinDENV and its parental viruses were examined in mammalian Vero and mosquito C6/36 cells (Fig. 2D). The results showed that ChinDENV replicated efficiently in Vero and C6/36 cells and peaked at 72 and 48 h postinfection, with titers of 105.8 PFU/ml and 106.9 PFU/ml, respectively. ChinDENV replicated slightly more efficiently than parental DENV-2, whereas both of them replicated less efficiently than JEV in both cells. The growth kinetics of ChinDENV was then determined in primary hamster kidney (PHK) cells, the certified cell bank intended for manufacturing ChinDENV. As shown in Fig. 2D, ChinDENV and DENV-2 exhibited very similar kinetics of virus production, with the same peak titer, approximately 106.3 PFU/ml. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the rescued ChinDENV chimera possesses the designed genomic structure, expresses DENV-specific antigens, shows a small-plaque phenotype, and replicates efficiently in different cell lines.

Genetic and plaque phenotypic stability of ChinDENV.

To assess the phenotype and genetic stability of ChinDENV during sequential passage in vitro, ChinDENV recovered from transfected cells (passage 0) was passaged up to 15 times in PHK cells. Viruses harvested at passages 3, 9, and 15 were subjected to a plaque forming assay and complete-genome sequencing in comparison with that of passage 0. The small-plaque phenotype of ChinDENV in BHK-21 cells remained unchanged at each passage (Fig. 2C), indicating that there were no plaque variants overgrowing the original parent population. Only a single nucleotide mutation at position 2173 in the E gene occurred at passage 15, leading to an amino acid change from Gln to Arg. Another silent nucleotide change at position 8666 in the NS5 gene was observed at passage 9. These data indicate that the chimeric virus ChinDENV exhibits a genetic and plaque phenotypic stability during in vitro passage.

Virulence of the chimeric ChinDENV in mice.

The JEV vaccine strain SA14-14-2 retains a degree of neurotropism in suckling mice (21). To make sure ChinDENV does not exceed its parental virus in neurovirulence, groups of 2-day-old BALB/c mice were inoculated with serial 10-fold dilutions of ChinDENV and its parental viruses, JEV SA14-14-2 and DENV-2 D2-43, by the i.c. route. All the infected animals were then observed for at least 21 days for signs of illness and death. As shown in Table 1, the LD50 of ChinDENV was 245.47 PFU, approximately 115-fold and 50-fold higher than those of JEV SA14-14-2 and DENV D2-43. Additionally, we also found that neither the ChinDENV chimera nor its parental viruses were lethal for 3- to 4-week-old BLAB/c mice inoculated at a dose of 105.0 PFU by the i.c. or i.p. route (data not shown). These results indicate that ChinDENV exhibits greatly reduced neurovirulence in suckling mice compared with those of its parental viruses and retains avirulence to immunocompetent adult mice.

Table 1.

Neurovirulence of ChinDENV and its parental viruses in suckling mice

| Virus (strain) | Dose (log10 PFU) | No.dead/no. inoculated (% mortality) | LD50 (PFU) | ASTa (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChinDENV | 3.00 | 3/4 (75) | 245.47 | 9.5 |

| 2.00 | 1/5 (20) | 13.8 | ||

| 1.00 | 1/4 (25) | 13.5 | ||

| 0.00 | 0/5 (0) | NA | ||

| JEV (SA14-14-2) | 3.00 | 4/4 (100) | 2.14 | 7.2 |

| 2.00 | 5/5 (100) | 8.6 | ||

| 1.00 | 3/4 (75) | 10.5 | ||

| 0.00 | 2/5 (40) | 12.6 | ||

| DENV-2 (D2-43) | 1.80 | 4/5 (80) | 4.97 | 8.0 |

| 0.80 | 4/5 (80) | 8.6 | ||

| −0.20 | 0/5 (0) | NA | ||

| −1.20 | 0/5 (0) | NA |

NA, not applicable.

Immunogenicity and protection in mice.

To assess the immunogenicity of ChinDENV in mice, groups of 4-week-old BALB/c mice were immunized with various doses (104.8 and 105.8 PFU per mouse) of ChinDENV by the s.c. route. Serum IgG and neutralizing antibodies against DENV-2 were measured by IFA and PRNT at 2, 4, and 6 weeks after immunization as previously described (32). All mice had seroconversion at 2 weeks postimmunization, and IgG antibody levels increased rapidly (Fig. 3A). High levels of IgG antibodies remained stable until day 42 in mice receiving either a low or high dose (104.8 or 105.8 PFU) of ChinDENV. Importantly, DENV-specific neutralizing antibodies were induced in all mice immunized with ChinDENV in a dose-dependent manner. The geometric mean titers (GMTs) of neutralizing antibody induced by low and high doses of ChinDENV were 47.1 and 106.3 on day 42 postimmunization, respectively (Fig. 3B).

Fig 3.

Immunogenicity of ChinDENV in mice. Groups of five 4-week-old BALB/c mice were immunized with doses of 60,000 or 600,000 PFU of the chimera by the s.c. route. Serum was collected from animals at 14, 28, and 42 days postvaccination for determination of titers of IgG antibody (A) and neutralizing antibody (B) against DENV-2 by using IFA and PRNT50, respectively. The dotted line represents the limit of detection of the assay for each serum.

To clarify whether preimmunization of JEV interferes with the immunogenicity of ChinDENV, mice immunized with JEV SA14-14-2 were subjected to a second immunization with the same dose of ChinDENV. As shown in Table 2, in mice immunized with JEV SA14-14-2, high neutralization antibodies against DENV-2 were successfully induced by the second ChinDENV immunization. However, the peak titer (55.00 ± 8.85) at 42 days after primary immunization in the JEV-preimmunized mice was slightly lower than that in naive mice (84.00 ± 17.33). And no neutralization antibody was detected in the PBS control group, as expected.

Table 2.

Immunogenicity assay of ChinDENV in mice preimmunized with JEV vaccine SA14-14-2

| 1st immunization | 2nd immunization | PRNT50 titer (mean ± SD) on indicated day after 1st immunization |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | 42 | ||

| JEV SA14-14-2 | ChinDENV | 5.00 ± 2.68 | 55.00 ± 8.85 |

| PBS | ChinDENV | 31.00 ± 8.75 | 84.00 ± 17.33 |

| PBS | PBS | <5 | <5 |

Since no ideal immunocompetent-mouse model was currently available for DENV challenge, we initially evaluated the protection efficacy of ChinDENV antisera in the established suckling-mouse model as previously described (27). Complete protection was observed for the group of animals inoculated with antisera from the ChinDENV-immunized mice, whereas all control mice died within 5 to 9 days postinoculation (data not shown). Taken together, these results demonstrate that immunization with a single dose of ChinDENV could induce a neutralizing antibody response against DENV-2 that conferred full protection against lethal DENV-2 challenge in suckling mice.

Viremia, immunogenicity, and protection in nonhuman primates.

Attenuation of ChinDENV was further evaluated in rhesus monkeys, the most suitable model for preclinical evaluation of safety of DENV infections for humans (33, 34). Three groups of adult rhesus monkeys were inoculated s.c. with ChinDENV at doses of 1 × 103, 1 × 104, and 1 × 105 PFU per animal. Viremia in monkeys was then determined by real-time RT-PCR for 10 days postinjection. All the animals injected with wild-type (wt) DENV-2 exhibited continual viremia (mean duration, 3.5 days), with a peak titer of 102.75 PFU/ml following DENV challenge. However, ChinDENV failed to produce any detectable viremia in any inoculated monkeys (Table 3). No signs of disease or clinical manifestation were observed in any of the ChinDENV-injected animals throughout the experiments. These results strongly demonstrate the excellent safety profile of ChinDENV in nonhuman primates.

Table 3.

Viremia in rhesus monkeys immunized with graded doses of ChinDENV

| Virus | Dose (log10 PFU) | Monkey | Gendera | Viremia (log10 PFU/ml) by indicated day postimmunizationb |

Mean |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Peak titer (SD) | Duration (SD) | ||||

| 5.0 | R0591 | M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| R0022 | F | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| R0772 | F | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| R0322 | F | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| ChinDENV | 4.0 | R0381 | M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| R0792 | F | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| R0822 | F | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3.0 | R0085 | M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| R0411 | M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| R0029 | M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| DENV-2 | 5.0 | R0742 | F | 0 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.75 (0.65) | 3.5 (0.5) |

| R0652 | F | 0 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.75 (0.65) | 3.5 (0.5) | ||

M, male; F, female.

0 < 1.0 log10 PFU/ml.

Next, we determined the neutralizing antibody response induced by the single dose of ChinDENV in monkeys. As shown in Table 4, all the ChinDENV-immune monkeys developed neutralizing antibodies to DENV-2 from day 15 until day 50 postimmunization in a dose-dependent manner. Monkeys receiving high and middle doses of ChinDENV attained peak GMTs of 184 and 204 on day 20 after inoculation, respectively. Animals immunized with the low dose of ChinDENV also developed strong neutralizing antibodies on day 30 postimmunization, with a GMT of 82. No neutralizing antibody was detected for the control animals immunized with PBS, as expected.

Table 4.

Neutralizing antibody response in rhesus monkeys immunized with ChinDENV

| Group | Dose (log10 PFU) | Monkey | Gendera | Reciprocal neutralizing antibody titerb |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day postimmunization |

Day postchallenge |

|||||||||

| −1 | 15 | 20 | 30 | 50 | 15 | 30 | ||||

| ChinDENV | 5.0 | R0591 | M | <10 | 56 | 343 | 206 | 96 | 283 | 456 |

| R0022 | F | <10 | 50 | 68 | 122 | 56 | 268 | 766 | ||

| R0772 | F | <10 | 64 | 334 | 170 | 129 | 1729 | 1455 | ||

| R0322 | F | <10 | 36 | 148 | 140 | 94 | 929 | 447 | ||

| GMT | <10 | 50 | 184 | 156 | 90 | 591 | 690 | |||

| 4.0 | R0381 | M | <10 | 28 | 287 | 127 | 62 | 243 | 447 | |

| R0792 | F | <10 | 51 | 275 | 163 | 98 | 227 | 327 | ||

| R0822 | F | <10 | 23 | 200 | 99 | 66 | 233 | 447 | ||

| GMT | <10 | 32 | 250 | 127 | 74 | 234 | 403 | |||

| 3.0 | R0085 | M | <10 | 15 | 37 | 86 | 74 | 240 | 418 | |

| R0411 | M | <10 | 49 | 73 | 78 | 56 | 411 | 538 | ||

| R0029 | M | <10 | 27 | 100 | 84 | 57 | 254 | 466 | ||

| GMT | lt]10 | 27 | 65 | 82 | 62 | 293 | 471 | |||

| PBS | R0802 | F | <10 | <10 | <10 | NT | NT | 157 | 170 | |

| R0245 | M | <10 | <10 | <10 | NT | NT | 158 | 109 | ||

| GMT | 157 | 136 | ||||||||

M, male; F, female.

50% plaque reduction neutralization measured against DENV-2 strain TSV01. Monkeys were immunized with the indicated doses of ChinDENV and challenged by the s.c. route with 105 PFU of DENV-2 strain TSV01 on day 63. Antibody levels were determined on −1, 15, 20, 30, and 50 days postimmunization and 15 and 30 days postchallenge. NT, not tested.

To assess the in vivo protective efficacy, all the vaccinated animals were challenged with wt DENV-2 on day 63 postimmunization, and viremia was monitored for 10 days thereafter. As shown in Table 5, control animals immunized with PBS exhibited continual viremia (mean duration, 5.5 days), with a peak titer of 102.25 PFU/ml following wt DENV-2 challenge. All the animals receiving high and middle doses (105 and 104 PFU) of ChinDENV developed no viremia following wt DENV-2 challenge; only one animal (R0085) immunized with a low dose (103 PFU) of ChinDENV developed low-level, transient viremia (Table 5). These observations showed that the single dose of ChinDENV immunization significantly protected against wt DENV-2-induced viremia in nonhuman primates. Additionally, the anamnestic antibody response after virus challenge was analyzed in the sera collected at days 15 and 30. It is noteworthy that all ChinDENV-immune monkeys developed a significant (∼4- to 6-fold) increase in serum neutralizing antibody titer after DENV-2 challenge, indicating that DENV-2 challenge had stimulated a strong anamnestic immune response (Table 4). Together, these results strongly demonstrate that a single immunization with ChinDENV successfully induced a robust protective immune response in nonhuman primates.

Table 5.

Viremia in ChinDENV-immunized rhesus monkeys challenged with wt DENV-2 by the s.c. route

| Group (PFU/monkey) | Monkey | Viremia (log10 PFU/ml) by postchallenge daya |

Mean |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | Peak titer (SD) | Duration (SD) | ||

| ChinDENV (105) | R0591 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| R0022 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| R0772 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| R0322 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| ChinDENV (104) | R0381 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| R0792 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| R0822 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| ChinDENV (103) | R0085 | 0 | 0 | 2.3 | 0 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 (1.3) | 0.7 (1.1) |

| R0411 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 (1.3) | 0.7 (1.1) | |

| R0029 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 (1.3) | 0.7 (1.1) | |

| PBS | R0802 | 1.9 | 0 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 0 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 2.25 (0.35) | 5.5 (0.5) |

| R0245 | 0 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 0 | 0 | 2.25 (0.35) | 5.5 (0.5) | |

0 <1.0 log10 PFU/ml.

Protection against lethal JEV challenge in mice.

Clinical trials have demonstrated that YFV-specific cellular immune response could be induced by the YFV-based CYD vaccination (35). In this study, to make sure that the potential protective immunity against JEV was conferred by ChinDENV immunization, groups of 4-week-old BALB/c mice immunized with ChinDENV were challenged with lethal JEV challenge. The same dose of SA14-14-2 was also immunized as controls together with PBS. All the mice were then subjected to a 15-day period of observation for signs of death. All the mice immunized with SA14-14-2 survived, and all PBS controls died within 9 days postinfection, as expected (Fig. 4A). Significantly, none of the ChinDENV-vaccinated animals died from wt JEV challenge. This result demonstrates that a single immunization with ChinDENV could induce complete protection against lethal JEV challenge.

Fig 4.

Cross protection against lethal JEV challenge induced by the chimera ChinDENV in mice. Groups of 4-week-old BALB/c mice were immunized with 105 PFU of JEV, ChinDENV, or PBS via the s.c. route. At 28 days postimmunization, serum was collected for determination of titers of neutralizing antibody by PRNT50. The immunized mice were then challenged with a lethal dose of JEV. From groups of ChinDENV- and PBS-immunized mice, 3 were sacrificed and their spleens were isolated for testing CD8+ T cell responses. (A) Survival data of the immunized mice after inoculation with a lethal dose of JEV (n = 8). (B) Neutralizing antibody level of ChinDENV-, JEV-, or PBS-immunized mice on day 28 postimmunization. (C) Cellular immune responses in the ChinDENV- or PBS-immunized mice. Purified lymphocytes from the spleen were stimulated with JEV or DENV-2 and their corresponding replicons for 36 h. The production of IFN-γ and IL-2 was measured by ELISPOT assay and expressed as spot-forming cells per 107 lymphocytes.

To further investigate the putative roles of the humoral and cellular immune responses in the protection against JEV challenge, PRNT against JEV and DENV-2 were assayed, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4B, ChinDENV immunization induced significant neutralizing antibodies (GMT, 1:33) against DENV-2, whereas the titer of neutralizing antibody against JEV was relatively low (GMT, 1:11). This result indicates that the ChinDNEV-induced protection may not be attributable to the humoral immune response to the chimeric DENV structural proteins.

We next ascertained whether the cell-mediated immune response accounts for the cross protection against JEV infection. Splenocytes from immunized and PBS control mice were harvested 4 weeks postimmunization and were stimulated with JEV or DENV-2 and its corresponding replicons. The production of IFN-γ and IL-2 was then assayed by ELISPOT assay. Significant levels of IFN-γ and IL-2 production were induced by either JEV or JEV replicons in ChinDENV-immunized mice, whereas neither DENV-2 nor DENV-2 replicons induced the secretion of IFN-γ or IL-2 in ChinDENV-immunized mice (Fig. 4C). These data indicate that the significant protection against JEV infection induced by ChinDENV is probably associated with an efficient cellular immune response to the JEV nonstructural proteins of ChinDENV.

DISCUSSION

Utilizing reverse genetics, we obtained a chimeric dengue virus, ChinDENV, by replacement of the prM-E coding region of JEV vaccine strain SA14-14-2 with the corresponding segment of DENV-2. Cleavage of the N-terminal signal sequence of prM by a host cellular peptidase requires prior removal of the C protein from this signal sequence by the viral NS2B/3 protease (36–38). These coordinated cleavage events are believed to play an important role in the process of the assembly of flavivirus virions. The C termini of the E proteins of all members of the Flaviviridae family have similar organizations (39) and consist of two antiparallel transmembrane helices (TM1 and TM2). The TM2 helix serves as an internal signal sequence for the synthesis of the first nonstructural protein, NS1 (40). As shown in Fig. 1B, the last and antepenultimate C-terminal amino acids of flavivirus E proteins are highly conserved, indicating that these amino acids are likely to play an important role in efficient cleavage of the E-NS1 junction. Thus, to ensure proper processing of prM and E proteins of DENV-2, the signal sequence of JEV between C and prM as well as the last three C-terminal amino acids of the JEV E protein were retained in the ChinDENV chimera (Fig. 1B). As expected, the resulting viable ChinDENV was characterized by the chimeric structure of the genome, and the proteins of ChinDENV appeared to be properly processed, with the E protein retaining the antigenic properties of DENV-2 (Fig. 2A). It was also observed that ChinDENV displayed a small-plaque phenotype in BHK-21 cells, similar to that of prM-E donor virus, but its plaque size was significantly reduced compared to that of JEV. We further found that ChinDENV grew equally as well as the parent virus DENV-2 in various cell lines, with decreased peak replication titers compared with JEV. These results are consistent with the previous observations that chimeras exhibited growth characteristics similar to those of the viruses contributing structural protein genes (5, 41), indicating that the reduction in plaque size and replication efficiency for ChinDENV compared to JEV are likely to be determined partly by the donor prM-E genes. In addition, the chimerization itself has been proved to contribute to the attenuation of chimeras (10, 42–50). Notably, the chimeric virus ChinDENV replicated efficiently in Vero and PHK cells, both of which are certified for vaccine production. Additionally, ChinDENV reached a peak titer of 107.7 PFU/ml in PHK cells after optimization. Serial passaging of ChinDENV in Vero cells resulted in a single amino acid change (Q400R) in the E protein of ChinDENV at passage 15 and a single silent nucleotide mutation (C8666T) within NS5 gene at passage 9. Neither mutation affected the phenotypic trait of plaque size of ChinDENV (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that the ChinDENV chimera can be convenient for scale-up and industrialization.

Loss of or low mouse virulence is an important attenuation marker for flaviviruses. In our study, the chimera ChinDENV exhibited a significant attenuation phenotype, with an i.c. LD50 about 115-fold and 50-fold higher than those of its parental viruses JEV SA14-14-2 and DENV-2 D2-43, respectively. In addition, lack of neuroinvasiveness of ChinDENV as well as its parental viruses in the adult mouse demonstrates that ChinDENV does not exceed its parental viruses in peripheral virulence. Attenuation of ChinDENV was further assessed by determining its viremia profile in rhesus monkeys, which is correlated closely to the phenotype of attenuation in humans (51, 52). No viremia was detected in any ChinDENV-inoculated monkey, even at a high dose (105 PFU) (Table 3), while monkeys developed high levels of viremia following inoculation with the same dose of wt DENV-2 (Table 3). These data indicate a favorable safety profile for ChinDENV.

A single dose of ChinDENV stimulated both IgG and neutralizing antibodies against DENV-2 in mice, and passive serum of mice immunized with ChinDENV conferred complete protection against DENV-2 challenge in suckling mice. In rhesus monkeys, the chimeric ChinDENV rapidly elicited a neutralizing antibody response to wt DENV-2 in a dose-dependent manner (Table 4). It was observed that the monkeys immunized with high and middle doses of ChinDENV showed no signs of viremia postchallenge, and the mean peak titer and mean duration of viremia in low-dose groups were significantly reduced compared with those of the PBS-immunized group after challenge with wt DENV-2 (Table 5). Especially, we found that one monkey with viremia postchallenge in the low-dose group had a neutralizing antibody titer of 1:74. Sanofi's recent phase 2b trial also showed a lack of protective efficacy against DENV-2 infection despite the induction of reasonable levels of neutralizing antibodies against all four serotypes on vaccination (13). The explanation for this phenomenon remains a puzzle.

Recall immunity after challenge plays a critical role in protection against flavivirus (53). The role of anamnestic responses for reducing viremia after challenge has been supported by previous studies (54–60). We also found that monkeys immunized with ChinDENV and challenged s.c. with wt DENV-2 had dramatic increases in serum neutralizing antibodies, suggesting a good memory component in ChinDENV immunity. However, the presence of an anamnestic immune response, even in animals that developed no detectable viremia, demonstrating limited or localized viral replication, has been shown in those animals. Nevertheless, the boost in antibody responses postchallenge would guarantee that upon natural exposure, vaccinated individuals would respond with a rapid and robust immune response. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the chimeric virus ChinDENV exhibits a satisfactory balance between attenuation and immunogenicity against DENV-2 in mice and monkeys.

JE vaccination has been proven to be the only effective measure for disease control (61), and the live vaccine SA14-14-2 is widely used in most areas where JE is endemic. Interestingly, a single immunization with ChinDENV provided full protection against lethal JEV challenge in BALB/c mice (Fig. 4). The existence of cross protection between heterologous but closely related members of the Flaviviridae family has been reported (62–66). Neutralization assay showed that the titer of neutralization antibody against JEV was relatively low and may not account for the in vivo protection. The contribution of the NS1-induced immune response should not be ruled out, since flavivirus NS1 protein has been shown to induce protective immune responses in animals (67–73). Notably, immunization with ChinDENV elicited significantly increased JEV antigen-specific T cell responses (IFN-γ and IL-2), suggesting a possible role for cellular immunity in the defense against JEV challenge in ChinDENV-immunized mice. T lymphocytes have been found to be necessary for protection from WNV (74) and DENV (75, 76) infections in animal models. Most identified flavivirus T cell epitopes reside in the nonstructural proteins (77–80), the majority of which concentrated within the NS3 protein (reviewed in reference 81). Although the contribution of cellular immune responses to recovery from JEV infection remains unclear, a requirement for both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to control infections in the central nervous system has also been shown for JEV (82). Collectively, these data suggest that ChinDENV can afford a cross protection against lethal JEV challenge in mice in association with both the humoral and cellular immune responses.

The DENV vaccine candidate ChinDENV described here represents a significant advancement for dengue vaccine development. First, ChinDENV utilizes the JE vaccine SA14-14-2, which has demonstrated an ideal safety profile in large-scale clinical usage, as the genetic backbone. Meanwhile, for YFV-17D, the backbone for CYD in clinical trials, vaccination-associated adverse events have been reported (83–87). Second, the Sanofi Pasteur's CYD2 vaccine carries the prM-E genes of Asian genotype I of DENV-2 (PUO-218 strain). The antigenic mismatch between the CYD2 vaccine virus and the DENV-2 circulating in Thailand currently has been partially attributed to the failure of protection in the clinical trials in Thailand (13). ChinDENV carries the protective antigens of DENV-2 strain D2-43 (Asian genotype II). In particular, there are five amino acid substitutions in the E protein (residues 71, 141, 164, 402, and 484) between ChinDENV and CYD2. Several of them are solvent exposed and involve potential neutralizing antibody epitope recognition (88). Third, JEV and DENV are currently cocirculating in many Asian countries, where the socioeconomic burden of both diseases is significant. A vaccine candidate that could protect against both DENV and JEV will be highly attractive.

In summary, the chimeric virus ChinDENV is characterized by a highly attenuated profile in mice, a lack of viremia in rhesus monkeys, satisfactory immunogenicity, and protective efficacy for DENV-2 infection in mice and monkeys. In particular, the chimera is capable of providing cross protection from JEV infection in mice. This novel live attenuated chimeric dengue vaccine based on JEV vaccine shows great potential for further development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Guan-Mu Dong and Li-Li Jia (National Institute for Food and Drug Control, Beijing) for helpful discussion.

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Project of China (no. 2012CB518904), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 31300151, 81101243, U1132002, and 31270974), and the National Major Special Program of Science and Technology of China (2008ZX10004-015 and 2013ZX10004001). C.-F.Q. was supported by the Beijing Nova Program of Science and Technology (no. 2010B041).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 October 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO 2012. Dengue and severe dengue. Fact sheet no. 117. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, Drake JM, Brownstein JS, Hoen AG, Sankoh O, Myers MF, George DB, Jaenisch T, Wint GR, Simmons CP, Scott TW, Farrar JJ, Hay SI. 2013. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 496:504–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray M, Lai CJ. 1991. Construction of intertypic chimeric dengue viruses by substitution of structural protein genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:10342–10346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pletnev AG, Bray M, Huggins J, Lai CJ. 1992. Construction and characterization of chimeric tick-borne encephalitis/dengue type 4 viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:10532–10536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers TJ, Nestorowicz A, Mason PW, Rice CM. 1999. Yellow fever/Japanese encephalitis chimeric viruses: construction and biological properties. J. Virol. 73:3095–3101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang CY, Butrapet S, Pierro DJ, Chang GJ, Hunt AR, Bhamarapravati N, Gubler DJ, Kinney RM. 2000. Chimeric dengue type 2 (vaccine strain PDK-53)/dengue type 1 virus as a potential candidate dengue type 1 virus vaccine. J. Virol. 74:3020–3028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bray M, Men R, Lai CJ. 1996. Monkeys immunized with intertypic chimeric dengue viruses are protected against wild-type virus challenge. J. Virol. 70:4162–4166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guirakhoo F, Weltzin R, Chambers TJ, Zhang ZX, Soike K, Ratterree M, Arroyo J, Georgakopoulos K, Catalan J, Monath TP. 2000. Recombinant chimeric yellow fever-dengue type 2 virus is immunogenic and protective in nonhuman primates. J. Virol. 74:5477–5485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guirakhoo F, Arroyo J, Pugachev KV, Miller C, Zhang ZX, Weltzin R, Georgakopoulos K, Catalan J, Ocran S, Soike K, Ratterree M, Monath TP. 2001. Construction, safety, and immunogenicity in nonhuman primates of a chimeric yellow fever-dengue virus tetravalent vaccine. J. Virol. 75:7290–7304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang CY, Butrapet S, Tsuchiya KR, Bhamarapravati N, Gubler DJ, Kinney RM. 2003. Dengue 2 PDK-53 virus as a chimeric carrier for tetravalent dengue vaccine development. J. Virol. 77:11436–11447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitehead SS, Hanley KA, Blaney JE, Jr, Gilmore LE, Elkins WR, Murphy BR. 2003. Substitution of the structural genes of dengue virus type 4 with those of type 2 results in chimeric vaccine candidates which are attenuated for mosquitoes, mice, and rhesus monkeys. Vaccine 21:4307–4316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guy B, Barrere B, Malinowski C, Saville M, Teyssou R, Lang J. 2011. From research to phase III: preclinical, industrial and clinical development of the Sanofi Pasteur tetravalent dengue vaccine. Vaccine 29:7229–7241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabchareon A, Wallace D, Sirivichayakul C, Limkittikul K, Chanthavanich P, Suvannadabba S, Jiwariyavej V, Dulyachai W, Pengsaa K, Wartel TA, Moureau A, Saville M, Bouckenooghe A, Viviani S, Tornieporth NG, Lang J. 2012. Protective efficacy of the recombinant, live-attenuated, CYD tetravalent dengue vaccine in Thai schoolchildren: a randomised, controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet 380:1559–1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guy B, Almond J, Lang J. 2011. Dengue vaccine prospects: a step forward. Lancet 377:381–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butrapet S, Huang CY, Pierro DJ, Bhamarapravati N, Gubler DJ, Kinney RM. 2000. Attenuation markers of a candidate dengue type 2 vaccine virus, strain 16681 (PDK-53), are defined by mutations in the 5′ noncoding region and nonstructural proteins 1 and 3. J. Virol. 74:3011–3019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osorio JE, Huang CY, Kinney RM, Stinchcomb DT. 2011. Development of DENVax: a chimeric dengue-2 PDK-53-based tetravalent vaccine for protection against dengue fever. Vaccine 29:7251–7260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blaney JE, Jr, Matro JM, Murphy BR, Whitehead SS. 2005. Recombinant, live-attenuated tetravalent dengue virus vaccine formulations induce a balanced, broad, and protective neutralizing antibody response against each of the four serotypes in rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 79:5516–5528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durbin AP, McArthur JH, Marron JA, Blaney JE, Thumar B, Wanionek K, Murphy BR, Whitehead SS. 2006. rDEN2/4Delta30(ME), a live attenuated chimeric dengue serotype 2 vaccine is safe and highly immunogenic in healthy dengue-naive adults. Hum. Vaccin. 2:255–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pletnev AG, Swayne DE, Speicher J, Rumyantsev AA, Murphy BR. 2006. Chimeric West Nile/dengue virus vaccine candidate: preclinical evaluation in mice, geese and monkeys for safety and immunogenicity. Vaccine 24:6392–6404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durbin AP, Whitehead SS, Shaffer D, Elwood D, Wanionek K, Thumar B, Blaney JE, Murphy BR, Schmidt AC. 2011. A single dose of the DENV-1 candidate vaccine rDEN1Delta30 is strongly immunogenic and induces resistance to a second dose in a randomized trial. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 5:e1267. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu Y. 2010. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of Japanese encephalitis attenuated live vaccine virus SA14-14-2 and their stabilities. Vaccine 28:3635–3641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bista MB, Banerjee MK, Shin SH, Tandan JB, Kim MH, Sohn YM, Ohrr HC, Tang JL, Halstead SB. 2001. Efficacy of single-dose SA 14-14-2 vaccine against Japanese encephalitis: a case control study. Lancet 358:791–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gatchalian S, Yao Y, Zhou B, Zhang L, Yoksan S, Kelly K, Neuzil KM, Yaich M, Jacobson J. 2008. Comparison of the immunogenicity and safety of measles vaccine administered alone or with live, attenuated Japanese encephalitis SA 14-14-2 vaccine in Philippine infants. Vaccine 26:2234–2241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hennessy S, Liu Z, Tsai TF, Strom BL, Wan CM, Liu HL, Wu TX, Yu HJ, Liu QM, Karabatsos N, Bilker WB, Halstead SB. 1996. Effectiveness of live-attenuated Japanese encephalitis vaccine (SA14-14-2): a case-control study. Lancet 347:1583–1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar R, Tripathi P, Rizvi A. 2009. Effectiveness of one dose of SA 14-14-2 vaccine against Japanese encephalitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 360:1465–1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tandan JB, Ohrr H, Sohn YM, Yoksan S, Ji M, Nam CM, Halstead SB. 2007. Single dose of SA 14-14-2 vaccine provides long-term protection against Japanese encephalitis: a case-control study in Nepalese children 5 years after immunization. Vaccine 25:5041–5045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deng YQ, Dai JX, Ji GH, Jiang T, Wang HJ, Yang HO, Tan WL, Liu R, Yu M, Ge BX, Zhu QY, Qin ED, Guo YJ, Qin CF. 2011. A broadly flavivirus cross-neutralizing monoclonal antibody that recognizes a novel epitope within the fusion loop of E protein. PLoS One 6:e16059. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye Q, Li XF, Zhao H, Li SH, Deng YQ, Cao RY, Song KY, Wang HJ, Hua RH, Yu YX, Zhou X, Qin ED, Qin CF. 2012. A single nucleotide mutation in NS2A of Japanese encephalitis-live vaccine virus (SA14-14-2) ablates NS1′ formation and contributes to attenuation. J. Gen. Virol. 93:1959–1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reed LR, Muench H. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493–497 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weatherall D. 2006. The use of non-human primates in research. The Royal Society, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li SH, Li XF, Zhao H, Deng YQ, Yu XD, Zhu SY, Jiang T, Ye Q, Qin ED, Qin CF. 2013. Development and characterization of the replicon system of Japanese encephalitis live vaccine virus SA14-14-2. Virol. J. 10:64. 10.1186/1743-422X-10-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao F, Li XF, Yu XD, Deng YQ, Jiang T, Zhu QY, Qin ED, Qin CF. 2011. A DNA-based West Nile virus replicon elicits humoral and cellular immune responses in mice. J. Virol. Methods 178:87–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosen L. 1999. Comments on the epidemiology, pathogenesis and control of dengue. Med. Trop. 59:495–498 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitehead RH, Chaicumpa V, Olson LC, Russell PK. 1970. Sequential dengue virus infections in the white-handed gibbon (Hylobates lar). Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 19:94–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guy B, Nougarede N, Begue S, Sanchez V, Souag N, Carre M, Chambonneau L, Morrisson DN, Shaw D, Qiao M, Dumas R, Lang J, Forrat R. 2008. Cell-mediated immunity induced by chimeric tetravalent dengue vaccine in naive or flavivirus-primed subjects. Vaccine 26:5712–5721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amberg SM, Rice CM. 1999. Mutagenesis of the NS2B-NS3-mediated cleavage site in the flavivirus capsid protein demonstrates a requirement for coordinated processing. J. Virol. 73:8083–8094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lobigs M, Lee E. 2004. Inefficient signalase cleavage promotes efficient nucleocapsid incorporation into budding flavivirus membranes. J. Virol. 78:178–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamshchikov VF, Compans RW. 1995. Formation of the flavivirus envelope: role of the viral NS2B-NS3 protease. J. Virol. 69:1995–2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cocquerel L, Wychowski C, Minner F, Penin F, Dubuisson J. 2000. Charged residues in the transmembrane domains of hepatitis C virus glycoproteins play a major role in the processing, subcellular localization, and assembly of these envelope proteins. J. Virol. 74:3623–3633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lindenbach BD, Thiel H-J, Rice CM. 2007. Flaviviruses: the viruses and their replication, p 1101–1152 In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE. (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhatt TR, Crabtree MB, Guirakhoo F, Monath TP, Miller BR. 2000. Growth characteristics of the chimeric Japanese encephalitis virus vaccine candidate, ChimeriVax-JE (YF/JE SA14–14–2), in Culex tritaeniorhynchus, Aedes albopictus, and Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 62:480–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chambers TJ, Liang Y, Droll DA, Schlesinger JJ, Davidson AD, Wright PJ, Jiang X. 2003. Yellow fever virus/dengue-2 virus and yellow fever virus/dengue-4 virus chimeras: biological characterization, immunogenicity, and protection against dengue encephalitis in the mouse model. J. Virol. 77:3655–3668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson BW, Chambers TV, Crabtree MB, Arroyo J, Monath TP, Miller BR. 2003. Growth characteristics of the veterinary vaccine candidate ChimeriVax-West Nile (WN) virus in Aedes and Culex mosquitoes. Med. Vet. Entomol. 17:235–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson BW, Chambers TV, Crabtree MB, Bhatt TR, Guirakhoo F, Monath TP, Miller BR. 2002. Growth characteristics of ChimeriVax-DEN2 vaccine virus in Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 67:260–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson BW, Chambers TV, Crabtree MB, Guirakhoo F, Monath TP, Miller BR. 2004. Analysis of the replication kinetics of the ChimeriVax-DEN 1, 2, 3, 4 tetravalent virus mixture in Aedes aegypti by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 70:89–97 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGee CE, Lewis MG, Claire MS, Wagner W, Lang J, Guy B, Tsetsarkin K, Higgs S, Decelle T. 2008. Recombinant chimeric virus with wild-type dengue 4 virus premembrane and envelope and virulent yellow fever virus Asibi backbone sequences is dramatically attenuated in nonhuman primates. J. Infect. Dis. 197:693–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGee CE, Tsetsarkin K, Vanlandingham DL, McElroy KL, Lang J, Guy B, Decelle T, Higgs S. 2008. Substitution of wild-type yellow fever Asibi sequences for 17D vaccine sequences in ChimeriVax-dengue 4 does not enhance infection of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. J. Infect. Dis. 197:686–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pletnev AG, Men R. 1998. Attenuation of the Langat tick-borne flavivirus by chimerization with mosquito-borne flavivirus dengue type 4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:1746–1751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pugachev KV, Schwaiger J, Brown N, Zhang ZX, Catalan J, Mitchell FS, Ocran SW, Rumyantsev AA, Khromykh AA, Monath TP, Guirakhoo F. 2007. Construction and biological characterization of artificial recombinants between a wild type flavivirus (Kunjin) and a live chimeric flavivirus vaccine (ChimeriVax-JE). Vaccine 25:6661–6671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taucher C, Berger A, Mandl CW. 2010. A trans-complementing recombination trap demonstrates a low propensity of flaviviruses for intermolecular recombination. J. Virol. 84:599–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Durbin AP, Karron RA, Sun W, Vaughn DW, Reynolds MJ, Perreault JR, Thumar B, Men R, Lai CJ, Elkins WR, Chanock RM, Murphy BR, Whitehead SS. 2001. Attenuation and immunogenicity in humans of a live dengue virus type-4 vaccine candidate with a 30 nucleotide deletion in its 3′-untranslated region. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 65:405–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Innis BL, Eckels KH, Kraiselburd E, Dubois DR, Meadors GF, Gubler DJ, Burke DS, Bancroft WH. 1988. Virulence of a live dengue virus vaccine candidate: a possible new marker of dengue virus attenuation. J. Infect. Dis. 158:876–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Konishi E, Yamaoka M, Khin Sane W, Kurane I, Takada K, Mason PW. 1999. The anamnestic neutralizing antibody response is critical for protection of mice from challenge following vaccination with a plasmid encoding the Japanese encephalitis virus premembrane and envelope genes. J. Virol. 73:5527–5534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bernardo L, Hermida L, Martin J, Alvarez M, Prado I, Lopez C, Martinez R, Rodriguez-Roche R, Zulueta A, Lazo L, Rosario D, Guillen G, Guzman MG. 2008. Anamnestic antibody response after viral challenge in monkeys immunized with dengue 2 recombinant fusion proteins. Arch. Virol. 153:849–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bernardo L, Izquierdo A, Alvarez M, Rosario D, Prado I, Lopez C, Martinez R, Castro J, Santana E, Hermida L, Guillen G, Guzman MG. 2008. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a recombinant fusion protein containing the domain III of the dengue 1 envelope protein in non-human primates. Antiviral Res. 80:194–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blair PJ, Kochel TJ, Raviprakash K, Guevara C, Salazar M, Wu SJ, Olson JG, Porter KR. 2006. Evaluation of immunity and protective efficacy of a dengue-3 pre-membrane and envelope DNA vaccine in Aotus nancymae monkeys. Vaccine 24:1427–1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guzmán MG, Rodriguez R, Hermida L, Alvarez M, Lazo L, Mune M, Rosario D, Valdes K, Vazquez S, Martinez R, Serrano T, Paez J, Espinosa R, Pumariega T, Guillen G. 2003. Induction of neutralizing antibodies and partial protection from viral challenge in Macaca fascicularis immunized with recombinant dengue 4 virus envelope glycoprotein expressed in Pichia pastoris. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 69:129–134 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Markoff L, Pang X, Houng HS, Falgout B, Olsen R, Jones E, Polo S. 2002. Derivation and characterization of a dengue type 1 host range-restricted mutant virus that is attenuated and highly immunogenic in monkeys. J. Virol. 76:3318–3328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raviprakash K, Porter KR, Kochel TJ, Ewing D, Simmons M, Phillips I, Murphy GS, Weiss WR, Hayes CG. 2000. Dengue virus type 1 DNA vaccine induces protective immune responses in rhesus macaques. J. Gen. Virol. 81:1659–1667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Robert Putnak J, Coller BA, Voss G, Vaughn DW, Clements D, Peters I, Bignami G, Houng HS, Chen RC, Barvir DA, Seriwatana J, Cayphas S, Garcon N, Gheysen D, Kanesa-Thasan N, McDonell M, Humphreys T, Eckels KH, Prieels JP, Innis BL. 2005. An evaluation of dengue type-2 inactivated, recombinant subunit, and live-attenuated vaccine candidates in the rhesus macaque model. Vaccine 23:4442–4452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Halstead SB, Thomas SJ. 2011. New Japanese encephalitis vaccines: alternatives to production in mouse brain. Expert Rev. Vaccines 10:355–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamshchikov G, Borisevich V, Kwok CW, Nistler R, Kohlmeier J, Seregin A, Chaporgina E, Benedict S, Yamshchikov V. 2005. The suitability of yellow fever and Japanese encephalitis vaccines for immunization against West Nile virus. Vaccine 23:4785–4792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Williams DT, Daniels PW, Lunt RA, Wang LF, Newberry KM, Mackenzie JS. 2001. Experimental infections of pigs with Japanese encephalitis virus and closely related Australian flaviviruses. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 65:379–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tesh RB, Travassos da Rosa AP, Guzman H, Araujo TP, Xiao SY. 2002. Immunization with heterologous flaviviruses protective against fatal West Nile encephalitis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:245–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takasaki T, Yabe S, Nerome R, Ito M, Yamada K, Kurane I. 2003. Partial protective effect of inactivated Japanese encephalitis vaccine on lethal West Nile virus infection in mice. Vaccine 21:4514–4518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kanesa-Thasan N, Putnak JR, Mangiafico JA, Saluzzo JE, Ludwig GV. 2002. Short report: absence of protective neutralizng antibodies to West Nile virus in subjects following vaccination with Japanese encephalitis or dengue vaccines. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 66:115–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schlesinger JJ, Brandriss MW, Cropp CB, Monath TP. 1986. Protection against yellow fever in monkeys by immunization with yellow fever virus nonstructural protein NS1. J. Virol. 60:1153–1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Falgout B, Bray M, Schlesinger JJ, Lai CJ. 1990. Immunization of mice with recombinant vaccinia virus expressing authentic dengue virus nonstructural protein NS1 protects against lethal dengue virus encephalitis. J. Virol. 64:4356–4363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Amorim JH, Diniz MO, Cariri FA, Rodrigues JF, Bizerra RS, Goncalves AJ, de Barcelos Alves AM, de Souza Ferreira LC. 2012. Protective immunity to DENV2 after immunization with a recombinant NS1 protein using a genetically detoxified heat-labile toxin as an adjuvant. Vaccine 30:837–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li Y, Counor D, Lu P, Duong V, Yu Y, Deubel V. 2012. Protective immunity to Japanese encephalitis virus associated with anti-NS1 antibodies in a mouse model. Virol. J. 9:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chung KM, Nybakken GE, Thompson BS, Engle MJ, Marri A, Fremont DH, Diamond MS. 2006. Antibodies against West Nile virus nonstructural protein NS1 prevent lethal infection through Fc gamma receptor-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J. Virol. 80:1340–1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee TH, Song BH, Yun SI, Woo HR, Lee YM, Diamond MS, Chung KM. 2012. A cross-protective mAb recognizes a novel epitope within the flavivirus NS1 protein. J. Gen. Virol. 93:20–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lin YL, Chen LK, Liao CL, Yeh CT, Ma SH, Chen JL, Huang YL, Chen SS, Chiang HY. 1998. DNA immunization with Japanese encephalitis virus nonstructural protein NS1 elicits protective immunity in mice. J. Virol. 72:191–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shresta S, Kyle JL, Snider HM, Basavapatna M, Beatty PR, Harris E. 2004. Interferon-dependent immunity is essential for resistance to primary dengue virus infection in mice, whereas T- and B-cell-dependent immunity are less critical. J. Virol. 78:2701–2710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yauch LE, Zellweger RM, Kotturi MF, Qutubuddin A, Sidney J, Peters B, Prestwood TR, Sette A, Shresta S. 2009. A protective role for dengue virus-specific CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 182:4865–4873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yauch LE, Prestwood TR, May MM, Morar MM, Zellweger RM, Peters B, Sette A, Shresta S. 2010. CD4+ T cells are not required for the induction of dengue virus-specific CD8+ T cell or antibody responses but contribute to protection after vaccination. J. Immunol. 185:5405–5416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Weiskopf D, Yauch LE, Angelo MA, John DV, Greenbaum JA, Sidney J, Kolla RV, De Silva AD, de Silva AM, Grey H, Peters B, Shresta S, Sette A. 2011. Insights into HLA-restricted T cell responses in a novel mouse model of dengue virus infection point toward new implications for vaccine design. J. Immunol. 187:4268–4279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Duangchinda T, Dejnirattisai W, Vasanawathana S, Limpitikul W, Tangthawornchaikul N, Malasit P, Mongkolsapaya J, Screaton G. 2010. Immunodominant T-cell responses to dengue virus NS3 are associated with DHF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:16922–16927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bashyam HS, Green S, Rothman AL. 2006. Dengue virus-reactive CD8+ T cells display quantitative and qualitative differences in their response to variant epitopes of heterologous viral serotypes. J. Immunol. 176:2817–2824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Akondy RS, Monson ND, Miller JD, Edupuganti S, Teuwen D, Wu H, Quyyumi F, Garg S, Altman JD, Del Rio C, Keyserling HL, Ploss A, Rice CM, Orenstein WA, Mulligan MJ, Ahmed R. 2009. The yellow fever virus vaccine induces a broad and polyfunctional human memory CD8+ T cell response. J. Immunol. 183:7919–7930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vaughan K, Greenbaum J, Blythe M, Peters B, Sette A. 2010. Meta-analysis of all immune epitope data in the Flavivirus genus: inventory of current immune epitope data status in the context of virus immunity and immunopathology. Viral Immunol. 23:259–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shrestha B, Pinto AK, Green S, Bosch I, Diamond MS. 2012. CD8+ T cells use TRAIL to restrict West Nile virus pathogenesis by controlling infection in neurons. J. Virol. 86:8937–8948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Khromava AY, Eidex RB, Weld LH, Kohl KS, Bradshaw RD, Chen RT, Cetron MS. 2005. Yellow fever vaccine: an updated assessment of advanced age as a risk factor for serious adverse events. Vaccine 23:3256–3263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lindsey NP, Schroeder BA, Miller ER, Braun MM, Hinckley AF, Marano N, Slade BA, Barnett ED, Brunette GW, Horan K, Staples JE, Kozarsky PE, Hayes EB. 2008. Adverse event reports following yellow fever vaccination. Vaccine 26:6077–6082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pulendran B, Miller J, Querec TD, Akondy R, Moseley N, Laur O, Glidewell J, Monson N, Zhu T, Zhu H, Staprans S, Lee D, Brinton MA, Perelygin AA, Vellozzi C, Brachman P, Jr, Lalor S, Teuwen D, Eidex RB, Cetron M, Priddy F, del Rio C, Altman J, Ahmed R. 2008. Case of yellow fever vaccine-associated viscerotropic disease with prolonged viremia, robust adaptive immune responses, and polymorphisms in CCR5 and RANTES genes. J. Infect. Dis. 198:500–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Silva ML, Espirito-Santo LR, Martins MA, Silveira-Lemos D, Peruhype-Magalhaes V, Caminha RC, de Andrade Maranhao-Filho P, Auxiliadora-Martins M, de Menezes Martins R, Galler R, da Silva Freire M, Marcovistz R, Homma A, Teuwen DE, Eloi-Santos SM, Andrade MC, Teixeira-Carvalho A, Martins-Filho OA. 2010. Clinical and immunological insights on severe, adverse neurotropic and viscerotropic disease following 17D yellow fever vaccination. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 17:118–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Seligman SJ. 2011. Yellow fever virus vaccine-associated deaths in young women. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17:1891–1893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sukupolvi-Petty S, Austin SK, Engle M, Brien JD, Dowd KA, Williams KL, Johnson S, Rico-Hesse R, Harris E, Pierson TC, Fremont DH, Diamond MS. 2010. Structure and function analysis of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies against dengue virus type 2. J. Virol. 84:9227–9239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]