Summary

We characterized the effect of ciprofloxacin (CPX) in cultured human tenocytes by morphological and molecular methods. Collagen type I and III mRNA and protein levels were unaffected, but lysyl hydroxylase 2b mRNA levels progressively decreased after CPX administration. MMP-1 protein levels significantly increased after 20 μg/ml CPX administration but remained unmodified at the higher dose, whilst MMP-2 activity was unchanged. Tissue inhibitor of MMP (TIMP-1) gene expression decreased after CPX treatment, whilst TIMP-2 and transforming growth factor-β1 gene expression, the cytoskeleton arrangement, and cytochrome c expression remained unmodified. Secreted Protein Acidic and Rich in Cysteine mRNA and protein levels remained almost unchanged, whilst N-cadherin mRNA levels resulted significantly down-regulated and connexin 43 gene expression tended to decrease after CPX administration.

The CPX-induced decreased ability to cross-link collagen and decreased TIMP-1 levels, possibly leading to higher activity of MMPs in ECM degradation, together with the down-regulation of N-cadherin and connexin 43 are consistent with a reduced ability to maintain tissue homeostasis, possibly making the tendon more susceptible to rupture.

Keywords: ciprofloxacin, collagen turnover, extra-cellular matrix remodelling, tendons, tenocytes

Introduction

Since the first report of the association of fluoroquinolones and tendon disorders in 1983, a causal relationship has emerged between the use of these antibiotics and tendon ruptures from comparative studies1,2. The incidence of adverse tendon effects from use of fluoroquinolones is estimated to be 10–15 cases per 100,000 prescriptions1,3. Older age, renal failure, corticosteroid use, rheumatic disease, diabetes mellitus, hyperparathyroidism are recognized as factors that increase the risk of fluoroquinolone-induced tendinitis and rupture4.

Among fluoroquinolones, pefloxacin and ciprofloxacin elicit greater tenotoxic effects than norfloxacin, levofloxacin, and ofloxacin3,4. The most commonly affected tendon is the Achilles, and its rupture was described in almost one-half of the reports4–6, but other sites such as the rectus femoris tendon are frequently involved7. Data from clinical studies show irregular collagen fiber arrangement, hypercellularity, and increased glycosaminoglycan content after ciprofloxacin (CPX) treatment8. Electron microscope analysis of rat tendons revealed cellular modifications induced by CPX, involving tenocyte organelles, as well as major changes in extra-cellular matrix (ECM) such as decreased fibril diameter and increased distance between the collagen fibers9. Also biomechanical parameters of rat tendons were deteriorated following exposure to CPX in vivo10. A dose-dependent effect of CPX in vitro on fibroblast proliferation and ECM turnover has been described11, as well as oxidative stress induction12, inhibition of tenocyte proliferation and cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase13. It was shown that fluoroquinolones induce tendinopathy by increasing matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), leading to tendon ECM degradation and loss of tendon homeostasis11. However, the mechanisms leading to fluoroquinolone-induced tendinopathy or tendon rupture are not yet completely clear since data are fragmented and sometimes incomplete.

This study was aimed at characterizing the effect of CPX administration on the phenotype of cultured human tenocytes, with particular attention to the expression of genes and proteins involved in collagen synthesis, maturation and degradation, and in the ECM remodeling potential. As tenocytes in tendon are connected by adhering and gap junctions, we also analyzed gene expression for N-cadherin and connexin 4314. Finally, in consideration of the key role of the actin cytoskeleton as a mechanotransduction agent acting in the maintenance of tendon tissue homeostasis15, we also characterized actin microfilament arrangement in CPX-treated tenocytes, as well as vimentin intermediate filaments and microtubules.

Patients and methods

Primary cell cultures

Tendon fragments were obtained from 6 male healthy subjects (mean age 37.7 ± SD 18.7), undergoing surgical procedures to treat anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Patients affected from tendinopathy were excluded from the study.

Three tendon specimens were from the rectus femoris, 1 from the gracilis and 2 from the semitendinosus muscle. Informed consent was obtained, according to the declaration of Helsinki.

Tendon fragments were rinsed with sterile Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), plated in T25 flasks, incubated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin), and ascorbic acid (200 μM) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. When tenocytes grew out from the explant, they were trypsinized (0.025% trypsin-0.02% EDTA) for secondary cultures and plated in T75 flasks. Viability was assessed by the Trypan blue exclusion method. For evaluations confluent human tenocytes were used between the fourth and fifth passage.

Ciprofloxacin treatment

CPX was used at three different doses: 10, 20 and 50 μg/ml. Untreated tenocytes served as controls (CT). CT and CPX-treated tenocytes were cultured in serum-free DMEM for 48 h and then harvested for molecular evaluations or prepared for immunofluorescence procedures, using duplicate cultures for each sample.

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated by a modification of the acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform method (Tri-Reagent, Sigma, Italy). One μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed in 20 μL final volume of reaction mix (Biorad, Segrate-Milan, Italy). mRNA levels of collagen type I and type III (COL-I, COL-III), long lysyl hydroxylase 2 (LH2b), matrix metalloproteinase 1 and 2 (MMP-1, MMP-2), Secreted Protein Acidic and Rich in Cysteine (SPARC), transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), N-cadherin and connexin 43 (CX43) were assessed. GAPDH was used as endogenous control to normalize the differences in the amount of total RNA in each sample.

The primers sequences, designed with Beacon Designer 6.0 Software (BioRad, Italy), were the following: GAPDH: sense CCCTTCATTGACCTCAACTACATG, antisense TGGGATTTCCATTGATGACAAGC; COL-I: sense CGACCTGGTGAGAGAGGAGTTG, anti-sense AATCCATCCAGACCATTGTGTCC; COL-III: sense TGTCAAGTCTGGAGTAGCAGTAGG, anti-sense GGAACCAGGATGACCAGATGTACC; LH2b: sense CCGGAAACATTCCAAATGCTCAG, antisense GCCAGAGGTCATTGTTATAATGGG. MMP-1: sense CGGATACCCCAAGGACATCTACAG, antisense GCCAATTCCAGGAAAGTCATGTGC; MMP-2: sense GCAGTGCAATACCTGAACACCTTC, antisense TCTGGTCAAGATCACCTGTCTGG; TIMP-1: sense GGCTTCTGGCATCCTGTTGTTG, antisense AAGGTGGTCTGGTTGACTTCTGG; TIMP-2: sense TGGAAACGACATTTATGGCAACCC; antisense CTCCAACGTCCAGCGAGACC; SPARC: sense GCGAGCTGGATGAGAACAACAC, antisense GTGGCAAAGAAGTGGCAGGAAG; TGF-β1: sense GTGCGGCAGTGGTTGAGC; antisense GGTAGTGAACCCGTTGATGTCC; N-cadherin: sense AGGATCAACCCCATACACCA, antisense TGGTTTGACCACGGTGACTA; CX43: sense GGA CAT GCA CTT GAA GCA GA, antisense GGT CGC TCT TTC CCT TAA CC.

Amplification reactions were conducted in a 96-well plate in a final volume of 20 μL per well containing 10 μL of 1X SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad, Italy), 2 μL of template, 300 pmol of each primer, and each sample was analyzed in triplicate in iQ5 thermal cycler (BioRad, Italy) after 40 cycles. The cycle threshold (Ct) was determined and gene expression levels relative to that of GAPDH were calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method, using the Gene Study module of the iQ5 Software.

Slot blot

COL-I, COL-III, MMP-1 and SPARC protein levels secreted by tenocytes in the cell culture medium were assessed by slot blot. Protein content was determined by a standardized colorimetric assay (DC Protein Assay, Bio Rad, Italy); 100 μg of total protein per sample in a final volume of 200 μL of Tris buffer saline (TBS) were spotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane in a Bio-Dot SF apparatus (Bio-Rad, Italy), according to manufacturer instructions. Membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% skimmed milk in TBST (TBS containing 0.05% tween-20), pH 8, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in monoclonal antibody to COL-I (1:1000 in TBST) (Sigma, Italy), COL-III (1:2000 in TBST) (Sigma, Italy), MMP-1 (1 μg/mL in TBST) (Millipore, Italy) or to SPARC (1:200 in TBST) (Novocastra, UK). After washing, membranes were incubated in HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse serum (1:40,000 in TBST) (Sigma, Italy) for 1 h. Immunoreactive bands, revealed by the Amplified Opti-4CN substrate (Amplified Opti-4CN, Bio Rad, Italy), were scanned densitometrically (UVBand, Eppendorf, Italy).

SDS-zymography

Culture media were mixed 3:1 with sample buffer (containing 10% SDS). Samples (15 μg of total protein) were run under non-reducing conditions without heat denaturation on to 10% polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE) co-polymerized with 1 mg/mL of type I gelatin. The gels were run at 4°C and, SDS-PAGE, were washed twice in 2.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min each and incubated overnight in a substrate buffer at 37°C (Tris-HCl 50 mM, CaCl2 5 mM, NaN3 0.02%, pH 7.5). MMP gelatinolytic activity, detected after staining the gels with Coomassie brilliant blue R250 as clear bands on a blue background, were quantified by densitometric scanning (UVBand, Eppendorf, Italy).

Fluorescence microscopy

Tenocytes from 4 out of 6 tendon fragments were cultured on 12-mm diameter round coverslips put into 24-well culture plates. After 48 hours CT and CPX-treated cells were washed in PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS containing 2% sucrose for 5 min at room temperature, post-fixed in 70% ethanol, and stored at −20°C until use.

For actin cytoskeleton analysis, cells were washed in PBS three times and incubated with with 50 μM rhodamine-phalloidin (Sigma-Milan) in PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 for 45 min in the dark at room temperature and then washed extensively in PBS.

For vimentin and tubulin detection, cells were incubated for 1 h at room temperature, respectively, with the monoclonal primary antibodies anti-vimentin (1:100 in PBS, Novocastra) or anti-tubulin (1:2000 in PBS, Sigma-Milan). Apoptosis was investigated using a monoclonal antibody anti-cytochrome c (1:100 in PBS, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA). Secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa 488 (1:500 in PBS, Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) was applied for 1 h at room temperature, followed by rinsing with PBS. Negative controls were incubated omitting the primary antibody.

After the labeling procedure was completed, the coverslips were incubated for 15 min with DAPI and mounted onto glass slides using mowiol mounting medium. The cells were photographed by a digital camera connected to a Nikon Eclipse microscope.

Statistical analysis

Data, expressed by mean ± standard deviation (SD), were analyzed by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student-Neumann-Keuls post hoc test (Prism GraphPad). P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Collagen synthesis, maturation and degradation

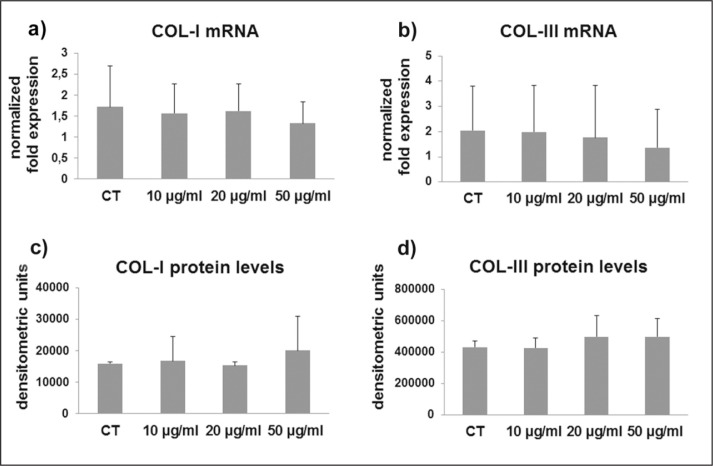

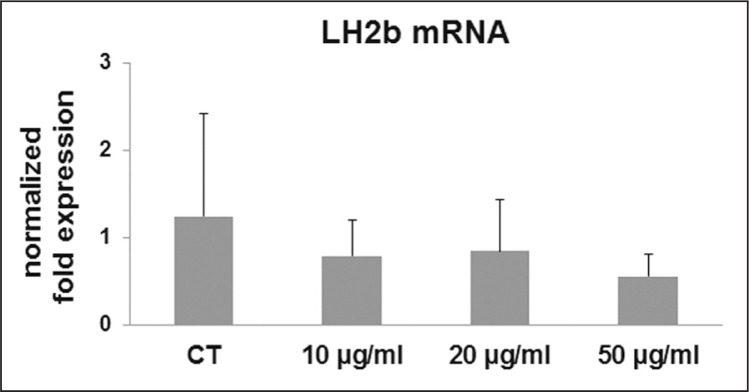

COL-I and COL-III were not affected by CPX administration at the mRNA (Fig. 1a, b) nor at the protein levels (Fig. 1c, d). Gene expression for LH2b, involved in the cross-linking of the newly synthesized collagen, was tended to be progressively down-regulated by CPX (p ns) after administration of 10 and 20 μg/ml and, at a higher extent, after 50 μg/ml (Fig. 2). This decrease was not statistically significant, very likely due to a different responsiveness of the different cell cultures. However, in 1 out of 6 samples the p value of the ANOVA was significant (p=0.021), and in 3 out of 6 samples the decrease of LH2b mRNA after 50 μg/ml CPX was significant (p<0.05 vs CT and 10 μg/ml CPX).

Figure 1.

Bar graphs showing COL-I (a) and COL-III mRNA levels (b) assessed by real time PCR in untreated (CT) and CPX-treated tenocytes. Data were normalized on GAPDH gene expression. (c) Bar graphs displaying COL-I and COL-III (d) protein levels analyzed by slot blot in culture medium of CT and CPX treated tenocytes. Data are mean ± SD for two independent experiments for samples run in duplicate.

Figure 2.

Bar graphs showing mRNA levels for LH2b in CT and tenocytes treated with CPX at different doses as described in the Materials and methods section. Data were normalized on GAPDH gene expression and are expressed as mean ± SD for two independent experiments for samples run in duplicate.

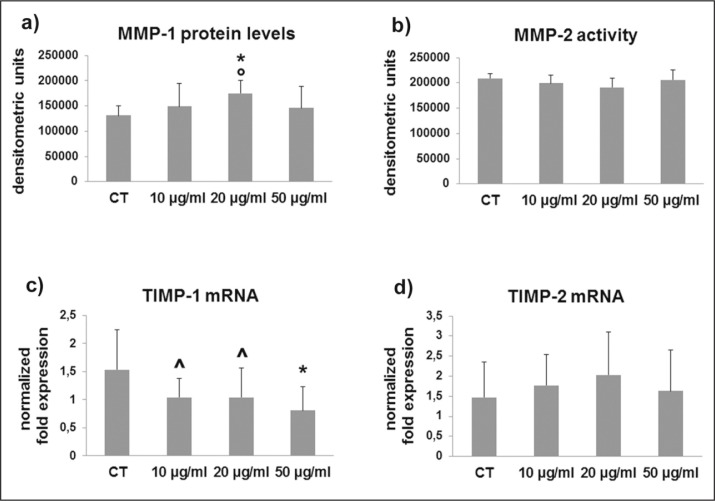

MMP-1 and MMP-2 protein levels and activity, involved in collagen degradation pathways, were analyzed by slot blot and SDS-zymography, respectively, in cell culture supernatants. MMP-1 protein levels were significantly increased by 20 μg/ml CPX but remained unmodified by the other CPX doses (Fig. 3a), and unchanged MMP-2 activity was observed after CPX administration at all the considered doses (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Bar graphs showing MMP-1 protein levels analyzed by slot blot and MMP-2 activity assessed by SDS-zymography (b) in tenocyte serum-free conditioned media after densitometric analysis of immunoreactive and lytic bands, respectively. Data are expressed as densitometric units ± SD for two independent experiments for samples run in duplicate. (c) Bar graphs showing TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 (d) gene expression after normalization on GAPDH mRNA levels. Data are expressed as mean ± SD for two independent experiments for samples run in duplicate.

*p<0.01 vs CT; ^p<0.05 vs CT; °p<0.05 vs 10 μg/ml

TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 were assessed by real time PCR. TIMP-1 gene expression was stronlgly affected after 10 μg/ml (p<0.05 vs CT), 20 μg/ml (p<0.05 vs CT), and 50 μg/ml CPX treatment (p<0.01 vs CT) (Fig. 3c). By contrast, TIMP-2 mRNA levels remained unmodified after CPX treatment (Fig. 3d).

Gene expression for TGF-β1, the major regulator of collagen turnover, was differently affected by CPX administration. In 1 out of 6 samples tended to decrease, in another 1 tended to increase and in 4 out of 6 was unmodified. The overall TGF-β1 gene expression was 1,81 ± 1,22 for CT tenocytes, and 1,71 ± 1,02, 1,94 ± 1,34, 1,74 ± 1,06 for tenocytes treated with 10 μg/ml, 20 μg/ml and 50 μg/ml CPX, respectively.

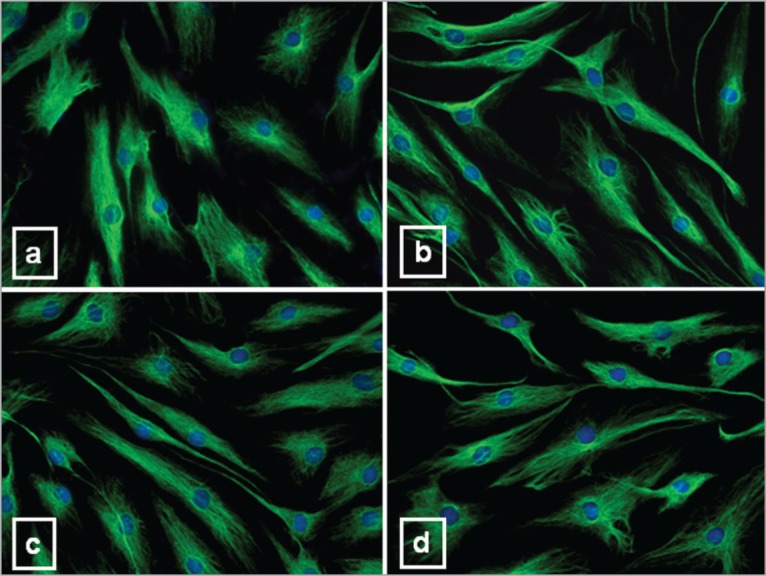

Cytoskeleton arrangement

Fluorescent microscope analysis for F-actin revealed many brightly labeled longitudinally running fibers of phalloidin-labeled actin in the cytoplasm of CT tenocytes (Fig. 4a). This pattern of expression was not affected by CPX treatment (Fig. 4b–d).

Figure 4.

Immunofluorescence analysis of the actin cytoskeleton in tenocytes untreated and treated with CPX. Representative immunofluorescence photomicrographs of microfilament distribution, evidenced by rhodamine-phalloidin labeling, in CT (a) and tenocytes after 10 μg/ml (b), 20 μg/ml (c) and 50 μg/ml CPX (d). DAPI was used for nuclear staining. Original magnification: 40×.

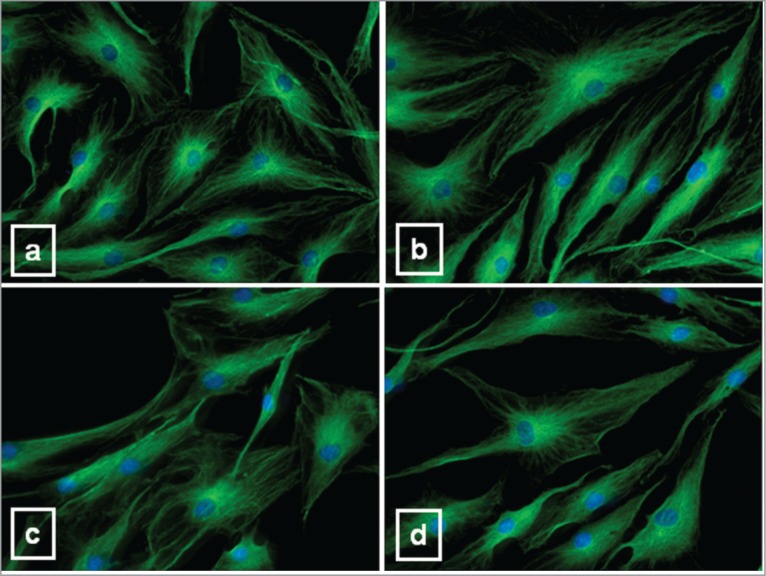

Vimentin intermediate filaments were dispersed in the cytoplasm of CT tenocytes (Fig. 5a), forming a typical network arranged around the nucleus, from which they irradiated out into the cell periphery in fine lace-like threads. This arrangement was non modified by CPX administration (Fig. 5d).

Figure 5.

Representative immunofluorescence analysis for vimentin intermediate filaments in CT (a) and tenocytes after 10 μg/ml (b), 20 μg/ml (c) and 50 μg/ml CPX (d). DAPI was used for nuclear staining. Original magnification: 40×.

The microtubule network displayed normal arrangement and organization in CT tenocytes (Fig. 6a), originating from a brightly stained organizing center located in the perinuclear area. A similar pattern was observed in CT and after 10 μg/ml (Fig. 6b), 20 μg/ml (Fig. 6c) and 50 μg/ml CPX (Fig. 6d).

Figure 6.

Representative immunofluorescence photomicrographs of microtubules in CT (a) and tenocytes after 10 μg/ml (b), 20 μg/ml (c) and 50 μg/ml CPX (d). DAPI was used for nuclear staining. Original magnification: 40×.

SPARC expression

SPARC mRNA levels tended to be slightly dose-dependently down-regulated (p ANOVA 0.065) by CPX administration (Fig. 7a). This pattern of expression resulted statistically different in 1 out of 6 samples (p<0.05 for 50 μg/ml vs 20 μg/ml CPX). By contrast, SPARC protein levels in cell culture supernatants were unchanged after CPX treatment (Fig. 7b).

Figure 7.

Bar graphs showing SPARC gene expression (a) and protein levels in cell culture super-natants (b), N-cadherin (c) and CX43 (d) mRNA levels in tenocytes untreated (CT) and after CPX administration. Data were normalized on GAPDH mRNA levels and are expressed as mean ± SD for two independent experiments for samples run in duplicate.

*P<0.05 vs CT; °P<0.01 vs CT

N-cadherin and CX43 gene expression

N-cadherin mRNA levels resulted down-regulated by the administration of 10 μg/ml CPX (p<0.05 vs CT), 20 μg/ml CPX (p<0.01 vs CT), and 50 μg/ml CPX (p<0.01 vs CT) (Fig. 7c).

As a whole, CX43 gene expression tended to decrease. The observed wide standard deviation is very likely a consequence of the different response elicited by CPX in the different tenocyte samples. In one sample CX43 gene expression was unchanged after CPX administration, in one tended to be increased, but, interestingly, tended to decrease in 4 out of 6 samples (p< 0.05 vs CT for 50 μg/ml in one of them) (Fig. 7d).

Intrinsic apoptosis

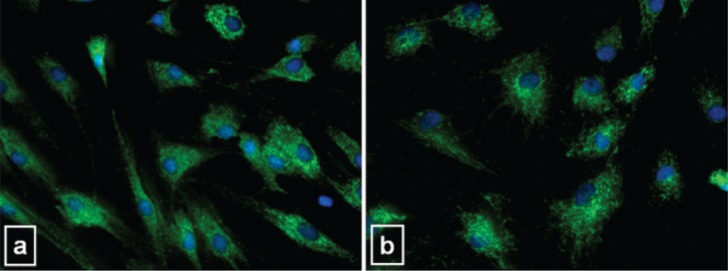

The possible pro-apoptotic effect of CPX on tenocytes was investigated by analyzing the expression of cytochrome c. Cytochrome c fluorescence was similarly expressed in CT and CPX-treated cells: a punctuate immunoreactivity was evident in the cytoplasm of both CT and treated cells (Fig. 8), suggesting that mitochondrial integrity is not affected by the drug.

Figure 8.

Intrinsic apoptosis analysis. Representative microphotographs showing immunofluorescence detection of cytochrome c in CT (a) and 50 μg/ml CPX-treated (b) tenocytes. Untreated CT and CPX-treated cells showed a similar immunoreactivity characterized by a punctate cytoplasmic staining pattern typical for localization of cytochrome c into intact mitochondria. Original magnification 40×.

Discussion

Tenocytes, the resident cells within the tendon, are able to synthesize and degrade tendon ECM, a finely balanced process of “turnover” playing a major role in the maintenance of tendon ECM homeostasis and, therefore, determining the ability of the tendon to resist mechanical forces and to repair in response to injury16,17. Some authors suggested that an imbalance in the synthesis and degradation of ECM components can lead to structure alterations and degeneration of the tendon18. Several studies described a causal relationship between CPX use and tendon disorders, thus leading to tendon rupture with an incidence estimated to be 1%1–3. Previous in vitro studies revealed a decreased tenocyte proliferation and an increase in ECM degradation with the concomitant decrease of its synthesis after CPX administration13. Thus, the increased ECM degradation and the concomitant limited capacity for repair were suggested as possible mechanisms of CPX-induced tendon ruptures.

In this study we investigated the effect of CPX administration on the overall expression of genes and proteins involved in collagen turnover and ECM remodeling in human cultured tenocytes. We also analyzed cytoskeleton arrangement and the expression of N-cadherin and CX43, since tenocytes in tendon are connected by adhering and gap junctions, in order to contribute to the comprehension of the overall mechanisms involved in CPX-induced tenotoxicity.

Type I collagen (COL-I) is the most abundant component of tendon ECM, accounting for approximately the 60% of the dry mass of the tissue. It is organized into fibrils aligned axially to the tendon length and providing the tissue with tensile strength. COL-I expression is consistent with the tensile loading of tendons16,19–21. Type III collagen (COL-III) is the second abundant collagen; in normal tendons COL-III tends to be restricted to the endotenon and epitenon22. However, it is also found intercalated into COL-I fibrils. As COL-III tends to produce thinner and less organized fibrils, this may have implications on the mechanical strength of the tendon. Our data on collagen expression at the mRNA and protein level show that COL-I and COL-III display a variable expression without relevant modifications after CPX administration, thus suggesting that interstitial collagen transcription and translation are not affected by CPX. These results are consistent with TGF-β1 gene expression.

Newly synthesized collagen, collagen fibrils and fibers in the ECM are stabilized by the formation of cross-links. Collagen cross-linking is an important requirement for collagen maturation in relation to the development of tendon strength, providing collagen fibril stabilization and increased tendon tensile strength. Moreover, it has been shown that the elastic properties of tendons are proportional to the fibril length and that the molecular basis of elastic energy storage in tendons seems to involve stretching of collagen triple-helix within cross-linked collagen fibrils23. Collagen cross-linking of the newly synthesized collagen is driven by lysyl hydroxylases and, among them LH2, is the major form expressed in all tissues and generally overexpressed in fibrotic processes. LH2 exists as two alternately-spliced forms, the long one or LH2b, the major form expressed in all tissues, and the short one (LH2a)24. Higher LH2b mRNA were related to higher collagen cross-linking and, in tendons, LH2b up-regulation was described in patients affected by cerebral palsy, possibly providing the ability to respond to higher mechanical load induced by spasticity and to resist to stretch25. Our data show that CPX administration elicits LH2b mRNA down-regulation in 5 out of 6 tenocyte samples, strongly pointing to LH2b as a major target of CPX, and suggesting that CPX-induced down-regulation of LH2b might be responsible of a less stable tendon, more susceptible to collagen degradation and, finally, more susceptible to damage. Collagen breakdown is driven by MMPs, a large family of proteases able to degrade all of tendon ECM components and thought to play a major role in the degradation of ECM during adaptation of tendon to mechanical loading and repair. MMPs are involved also in altered ECM turnover in tendinopathy26,27. MMP-1 begins collagen degradation breakdown by cleaving the native triple helical region of interstitial collagens into characteristic 3/4- and 1/4-collagen degradation fragments, also known as gelatins, that can be further degraded by less specific MMPs such as MMP-2, leading to complete digestion of the fibrillary collagen. The key role of MMP-1 in determining tendon strength is supported by the inverse correlation between MMP-1 gene/protein expression and tensile load, suggesting that low levels of MMP-1 are related to a more stable tendon structure and therefore less susceptible to damage15. MMPs undergo post-translational regulation by tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs), that are specific inhibitors of MMPs; each TIMP binds to active MMPs in a stoichiometric (1:1) ratio, resulting in a stable and inactive complex28. Generally, all TIMPs members inhibit all MMP members to varying degrees, although functional differences have been identified, and TIMP-1 is the main inhibitor of MMP-1. Our results suggest that MMP-1 protein levels were significantly increased by 20 μg/ml CPX but remained unmodified by the other CPX doses, and unchanged MMP-2 activity was observed after CPX administration at all the considered doses. By contrast, we observed a significant TIMP-1 mRNA down-regulation in CPX-treated samples. The observed MMP-1 expression and the concomitant TIMP-1 mRNA down-regulation suggest that collagen degradation could be likely favoured in CPX-treated tenocytes, and that CPX-induced tenotoxicity may be the result of the decreased inhibition of MMP-1, thus leading to increased ECM catabolism. Since, by contrast, it was reported that tendinopathy is associated to increased MMP with no change in TIMP-1 levels26, we can hypothesize that the molecular mechanisms underlying CPX-induced effects on ECM degradation pathways may be different than in tendinopathy. Our data, however, are not consistent with the recent study by Tsai et al.29, who described an increased MMP-2 activity and unmodified TIMP-1 in CPX-treated rat tenocytes. Since interindividual responses may be elicited by CPX administration, a possible explanation of this discrepancy is that in that study only one primary culture of rat tenocytes was used, that therefore was not representative.

Although increased ECM degradation was pointed as the major mechanism responsible for the loss of tendon homeostasis, previous studies showed that CPX was able to induce the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1 in monocytes and macrophages, and to mediate inhibition of cell proliferation and G2/M cell cycle arrest13, thus suggesting that fluoroquinolone-induced tendinopathy may be dependent on the combination of different factors.

ECM remodelling is driven by SPARC, a matricellular glycoprotein that influences a number of biological processes including cell differentiation, migration and proliferation, and is generally overexpressed during ECM remodeling in physiological and pathological conditions. SPARC’s counter-adhesive properties also modulate cell-matrix interactions30. High rate of tissue remodeling is observed in pathologic conditions, and it was suggested that high remodeling is likely to occur secondary to the rupture of tendon in an attempt to repair the defect31. Our findings suggest that CPX does not trigger SPARC protein level increase in cell culture supernatants, and that therefore ECM remodelling is not induced.

Our results on collagen turnover and ECM remodeling show that CPX elicits in some samples different responses, suggesting that tenocytes may display different phenotypes in relation to their ability to maintain ECM homeostasis and to respond to external stimuli, such as CPX administration. This hypothesis is supported by the previously reported inter-individual heterogeneity of gingival fibroblast subpopulations and their heterogeneous responses to various stimuli, playing a relevant role in determining different gingival fibroblast phenotype in relation to collagen turnover and to the responsiveness to drugs32. Thus, different phenotype-related response of tenocytes to CPX administration may account for the observation that CPX-induced tendon rupture occurs in a small proportion of patients.

In mature tendons, tenocytes are arranged in longitudinal rows between the fiber bundles, and they are intimately cell to cell connected with neighboring cells, both with the same cell row and with parallel rows, containing adherens and gap junctions formed by CX32 and CX4314. N-cadherin is the transmembrane protein of adherens junctions in mesenchymal cells, supported by actin cytoskeleton that contributes to cell-cell interaction and to mechanotransduction mechanisms in response to mechanical load16. Decreased N-cadherin gene expression elicited by CPX is consistent with a decreased ability of tenocytes for cell-cell or cell-matrix adhesion, possibly affecting tissue integrity.

CX43 allows cell-cell communication both longitudinally and laterally, contributing to the maintenance of tendon ECM homeostasis is response to tendon mechanical loading, allowing coordination of synthetic activity and facilitating strain-induced collagen synthesis. Our results show a tendency to CX43 mRNA level down-regulation in CPX-treated tenocytes, very likely providing reduced gap junction communication efficiency and synthetic responsiveness.

Some studies by Arnoczky et al.15 showed that tendon connective tissue cells are able to sense and to respond to changes in their mechanical environment using a mechanotransduction system based on the actin cytoskeleton. This is thought to occur through the transfer of the tissue strain applied to tendon to the cell cytoskeleton, eliciting a mechanotransduction response implicated in the maintenance of tissue homeostasis33. In particular, the major role of actin filaments was strongly correlated with collagenase gene expression, since microfilament destruction by cytocalasin D abolished all inhibitory effects of mechanical loading on MMP-1 gene expression down-regulation15, 34.

Since the loss of cytoskeletal tensional homeostasis and the consequent decreased mechanoresponsiveness seem to be involved in the loss of ECM balance, we investigated whether CPX is able to target the actin cytoskeleton to induce its tenotoxic effects. Our data show that actin filament arrangement in tenocyte is not altered after CPX administration, suggesting that CPX-treated tenocytes maintain the integrity of their actin-based mechanotransduction system and, therefore, the ability to remodel the surrounding ECM in response to mechanical loading demand. Moreover, also intermediate filaments and microtubules were not affected by CPX, suggesting that the drug does not target the cell cytoskeleton.

Intrinsic apoptosis was recently investigated in fluoroquinolone-induced tendon disorders and recent data show that CPX elicits nuclear material condensation, apoptotic bodies, bleb formation and caspase-3 activation35. Our data are not in accordance with these results, since we did not observe any altered expression of cytochrome c in CPX-treated tenocytes. This discrepancy, again, could be the result of a different phenotype of tendon cells, influencing their responsiveness to CPX administration and the adverse effects of this drug, in particular in association with glucocorticoids36.

Conclusion

Considered as a whole, our data suggest that CPX administration in vitro could induce a weakness-related phenotype in human tenocytes, mainly characterized by decreased ability to cross-link collagen and decreased TIMP-1 levels, possibly leading to higher activity of MMPs in ECM degradation. Therefore, CPX treatment may be responsible for the failure of tenocytes to adequately maintain tendon ECM responses to mechanical loading in vivo. This hypothesis is strengthened by the down-regulation of N-cadherin and CX43, suggesting a reduced ability for the cell-cell communication needed to maintain tissue homeostasis. On the basis of these observations, we can hypothesize that after CPX administration a repetitive loading below the injury threshold of the tendon could induce degenerative changes in the composition and organization of tendon ECM, thus leading to a weakness of the tissue and making it more susceptible to rupture. We feel that our results provide new information on CPX-induced modifications on tendons, contributing to understand fluoroquinolone tenotoxicity and to plan therapeutic treatments in particular in aged people, since it was previously shown that quinolone-induced tendinopathy or tendon rupture tends to be age-related and that ageing potentiated the effect of ciprofloxacin on tenocytes37. Future perspectives of this research are related to the characterization of CPX effects on aged tenocytes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ariel Foundation, Centro per le Disabilità Neuromotorie Infantili, Milan, Italy.

Footnotes

Authors’ contribution

AM maintained cell cultures and carried out immunofluorescence experiments; LP maintained cell cultures; CM reviewed immunofluorescence experiments; GC contributed to the drafting of the manuscript; NMP recruited patients and performed surgery; IDD contributed to the drafting of the manuscript; MCD assisted with general scientific discussion; NG conceived and designed the study, performed gene and protein expression analysis, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Wilton LV, Pearce GL, Mann RD. A comparison of ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, ofloxacin, azithromycin and cefixime examined by observational cohort studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;41:277–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1996.03013.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Linden PD, van de Lei J, Nab HW, Knol A, Stricker BH. Achilles tendinitis associated with fluoroquinolones. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;48:433–437. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pierfitte C, Royer RJ. Tendon disorders with fluoroquinolones. Therapie. 1996;51:419–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khaliq Y, Zhanel GG. Fluoroquinolone-associated tendinopathy: a critical review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1404–1410. doi: 10.1086/375078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozaras R, Mert A, Tahan V, Uraz S, Ozaydin I, Yilmaz MH, Ozaras N. Ciprofloxacin and Achilles’ tendon rupture: a causal relationship. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22:500–501. doi: 10.1007/s10067-003-0758-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akali AU, Niranjan NS. Management of bilateral Achilles tendon rupture associated with ciprofloxacin: a review and case presentation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:830–834. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karistinos A, Paulos LE. “Ciprofloxacin-induced” bilateral rectus femoris tendon rupture. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17:406–407. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31814c3e69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Movin T, Gad A, Güntner P, Földhazy Z, Rolf C. Pathology of the Achilles tendon in association with ciprofloxacin treatment. Foot Ankle Int. 1997;18:297–299. doi: 10.1177/107110079701800510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shakibaei M, Stahlmann R. Ultrastructural changes induced by the des-F(6)-quinolone garenoxacin (BMS-284756) and two fluoroquinolones in Achilles tendon from immature rats. Arch Toxicol. 2003;77:521–526. doi: 10.1007/s00204-003-0478-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olcay E, Beytemur O, Kaleagasioglu F, Gulmez T, Mutlu Z, Olgac V. Oral toxicity of pefloxacin, norfloxacin, ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin: comparison of biomechanical and histopathological effects on Achilles tendon in rats. J Toxicol Sci. 2011;36:339–345. doi: 10.2131/jts.36.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams RJ, 3rd, Attia E, Wickiewicz TL, Hannafin JA. The effect of ciprofloxacin on tendon, paratenon, and capsular fibroblast metabolism. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:364–369. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280031401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pouzaud F, Bernard-Beaubois K, Thevenin M, Warnet JM, Hayem G, Rat P. In vitro discrimination of fluoroquinolones toxicity on tendon cells: involvement of oxidative stress. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:394–402. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.057984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai WC, Hsu CC, Tang FT, Wong AM, Chen YC, Pang JH. Ciprofloxacin-mediated cell proliferation inhibition and G2/M cell cycle arrest in rat tendon cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1657–1663. doi: 10.1002/art.23518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNeilly CM, Banes AJ, Benjamin M, Ralphs JR. Tendon cells in vivo form a three dimensional network of cell processes linked by gap junctions. J Anat. 1996;189:593–600. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnoczky SP, Tian T, Lavagnino M, Gardner K. Ex vivo static tensile loading inhibits MMP-1 expression in rat tail tendon cells through a cytoskeletally based mechanotransduction mechanism. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:328–333. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kjaer M. Role of extracellular matrix in adaptation of tendon and skeletal muscle to mechanical loading. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:649–698. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birch HL, Thorpe CT, Rumian AP. Specialisation of extracellular matrix for function in tendons and ligaments. Muscle, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. 2013;3:12–22. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2013.3.1.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ireland D, Harrall R, Curry V, Holloway G, Hackney R, Hazleman B, Riley G. Multiple changes in gene expression in chronic human Achilles tendinopathy. Matrix Biol. 2001;20:159–169. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kannus P. Structure of the tendon connective tissue. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2000;10:312–320. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2000.010006312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gagliano N, Menon A, Martinelli C, Pettinari L, Panou A, Milzani A, Dalle-Donne I, Portinaro NM. Tendon structure and extracellular matrix components are affected by spasticity in cerebral palsy patients. Muscle, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. 2013;3:42–50. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2013.3.1.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tresoldi I, Oliva F, Benvenuto M, Fantini M, Masuelli L, Bei R, Modesti A. Tendon’s ultrastructure. Muscle, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. 2013;3:2–6. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2013.3.1.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duance VC, Restall DJ, Beard H, Bourne FJ, Bailey AJ. The location of three collagen types in skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 1977;79:248–252. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(77)80797-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silver FH, Christiansen D, Snowhill PB, Chen Y, Landis WJ. The role of mineral in the storage of elastic energy in turkey tendons. Biomacromolecules. 2000;1:180–185. doi: 10.1021/bm9900139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walker LC, Overstreet MA, Yeowell HN. Tissue-specific expression and regulation of the alternatively-spliced forms of lysyl hydroxylase 2 (LH2) in human kidney cells and skin fibroblasts. Matrix Biol. 2005;23:515–523. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gagliano N, Pelillo F, Grizzi F, Picciolini O, Gioia M, Portinaro N. Expression profiling of genes involved in collagen turnover in tendons from cerebral palsy patients. Connect Tissue Res. 2009;50:203–208. doi: 10.1080/03008200802613630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riley GP. Gene expression and matrix turnover in overused and damaged tendons. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2005;15:241–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Del Buono A, Oliva F, Osti L, Maffulli N. Metalloproteases and tendinopathy. Muscle, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. 2013;3:51–57. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2013.3.1.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy G, Willenbrock F, Crabbe T, O’Shea M, Ward R, Atkinson S, O’Connell J, Docherty A. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase activity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;732:31–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb24722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai WC, Hsu CC, Chen CP, Chang HN, Wong AM, Lin MS, Pang JH. Ciprofloxacin up-regulates tendon cells to express matrix metalloproteinase-2 with degradation of type I collagen. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:67–73. doi: 10.1002/jor.21196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bornstein P, Sage EH. Matricellular proteins: extracellular modulators of cell function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:608–616. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riley GP, Curry V, DeGroot J, van El B, Verzijl N, Hazleman BL, Bank RA. Matrix metalloproteinase activities and their relationship with collagen remodelling in tendon pathology. Matrix Biol. 2002;21:185–195. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tipton DA, Stricklin GP, Dabbous MK. Fibroblast heterogeneity in collagenolytic response to cyclosporine. J Cell Biochem. 1991;46:152–165. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240460209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Docking S, Samiric T, Scase E, Purdam C, Cook J. Relationship between compressive loading and ECM changes in tendons. Muscle, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. 2013;3:7–11. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2013.3.1.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavagnino M, Arnoczky SP, Tian T, Vaupel Z. Effect of amplitude and frequency of cyclic tensile strain on the inhibition of MMP-1 mRNA expression in tendon cells: an in vitro study. Connect Tissue Res. 2003;44:181–187. doi: 10.1080/03008200390215881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sendzik J, Shakibaei M, Schäfer-Korting M, Stahlmann R. Fluoroquinolones cause changes in extracellular matrix, signalling proteins, metalloproteinases and caspase-3 in cultured human tendon cells. Toxicology. 2005;212:24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sendzik J, Shakibaei M, Schäfer-Korting M, Lode H, Stahlmann R. Synergistic effects of dexamethasone and quinolones on human-derived tendon cells. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;35:366–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang HN, Pang JHS, Chen CPC, Ko PC, Lin MS, Tsai WC, Yang YM. The Effect of aging on migration, proliferation, and collagen expression of tenocytes in response to ciprofloxacin. J Orthop Res. 2012;30:764–768. doi: 10.1002/jor.21576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]