Abstract

Microbial mannanases are biotechnologically important enzymes since they target the hydrolysis of hemicellulosic polysaccharides of softwood biomass into simple molecules like manno-oligosaccharides and mannose. In this study, we have implemented a strategy of molecular engineering in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica to improve the specific activity of two fungal endo-mannanases, PaMan5A and PaMan26A, which belong to the glycoside hydrolase (GH) families GH5 and GH26, respectively. Following random mutagenesis and two steps of high-throughput enzymatic screening, we identified several PaMan5A and PaMan26A mutants that displayed improved kinetic constants for the hydrolysis of galactomannan. Examination of the three-dimensional structures of PaMan5A and PaMan26A revealed which of the mutated residues are potentially important for enzyme function. Among them, the PaMan5A-G311S single mutant, which displayed an impressive 8.2-fold increase in kcat/KM due to a significant decrease of KM, is located within the core of the enzyme. The PaMan5A-K139R/Y223H double mutant revealed modification of hydrolysis products probably in relation to an amino-acid substitution located nearby one of the positive subsites. The PaMan26A-P140L/D416G double mutant yielded a 30% increase in kcat/KM compared to the parental enzyme. It displayed a mutation in the linker region (P140L) that may confer more flexibility to the linker and another mutation (D416G) located at the entrance of the catalytic cleft that may promote the entrance of the substrate into the active site. Taken together, these results show that the directed evolution strategy implemented in this study was very pertinent since a straightforward round of random mutagenesis yielded significantly improved variants, in terms of catalytic efiiciency (kcat/KM).

Introduction

Hemicellulose is a combined designation of a diverse set of abundant non-crystalline carbohydrate polymers, among which mannans are the major component in softwoods [1] and are also present in certain plant seeds [2]. Mannans comprise molecules constituted either by a backbone of β-1,4-linked D-mannose residues, known as mannan, or by a heterogeneous combination of β-1,4-D-mannose and β-1,4-D-glucose units, termed glucomannan. Both can be decorated with α-1,6-linked galactose side chains, and these polysaccharides are referred to as galactomannan and galactoglucomannan, respectively. According to Salmén [3] softwood glucomannans are incorporated into aggregates of cellulose, i.e., they are arranged in parallel with cellulose fibrils, to which they are tightly connected.

Mannans are hydrolyzed by the coordinated action of several types of glycoside hydrolases (GH) among which endo-β-1,4 mannanases (EC 3.2.1.78) are the key enzymes that depolymerize the mannan backbone. They are encountered in families GH5, GH26 and GH113 in the CAZy database [4], [5]. Beta-mannanases are useful in several industrial processes such as reduction of viscosity of coffee extracts [6] or biobleaching of softwood Kraft pulp [7] and it is now acknowledged that they will become increasingly important for the biorefining of lignocellulose, especially from softwood biomass [8]–[11]. In the biorefinery process, enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass is one of the major bottlenecks due to the recalcitrance of the plant cell wall and the high cost of enzymes, mainly due to the fact that large amounts are required to breakdown lignocellulose to fermentable sugars [12]–[14].

Despite the fact that mannanases are largely exploited in biotechnological applications, only a few studies have so far reported on the improvement of mannanase properties using molecular engineering [15], [16]. Directed evolution is an important tool for improving critical traits of biocatalysts for industrial applications [17]. Recent advances in mutant library creation and high-throughput screening have greatly facilitated the engineering of biocatalysts but to date only few studies describe improvement of biomass-degrading enzymes using molecular evolution [18]–[20]. The major problem with most directed evolution experiments on biomass-degrading enzymes is the setup of high-throughput assays [17], [21], [22] since it is problematic to measure enzyme activities towards insoluble (hemi) cellulosic substrates.

In this study, a random mutagenesis strategy was used to generate variants of two endo-mannanases from the ascomycete fungus Podospora anserina that belong to the glycoside hydrolase (GH) families GH5 and GH26 (PaMan5A and PaMan26A, respectively) in order to improve their activity towards galactomannan. To evaluate the activity of mannanase variants produced in the Yarrowia lipolytica expression host, an in-house high-throughput method based on the reducing sugar assay [23] was adapted to assay mannanase activity in liquid culture. The results are interpreted in the lights of the three-dimensional structures of both fungal mannanases [24].

Results and Discussion

PaMan5A and PaMan26A heterologous expression in Yarrowia lipolytica

The yeast Y. lipolytica was chosen as host to perform molecular engineering of PaMan5A and PaMan26A since a very high reproducibility in protein expression level was demonstrated [25]. The two genes encoding PaMan5A and PaMan26A were inserted into the Y. lipolytica expression vector in frame with the yeast preprolip2 secretion peptide under the control of the oleic acid-inducible promoter POX2 (Figure 1). Positive transformants selected on plates containing galactomannan were able to produce functional PaMan5A and PaMan26A enzymes to a level of 10.4±0.2 and 11.2±0.6 U.ml−1 in shake flasks, respectively. The culture conditions enabling the secretion of wild-type PaMan5A and PaMan26A were miniaturized in 96-well plates as described in [26] to facilitate the set-up of the high-throughput screening procedure. The mean activities calculated from repeated experiments were 1.78±0.14 and 1.24±0.15 U.ml−1 of culture for PaMan5A and PaMan26A, respectively (coefficient of variation [CV] of 7.7 and 12.2%, respectively), which is adequate for excluding false positives variants. The secretion yields of PaMan5A and PaMan26A in deep-well microplates were 6- and 9-fold lower than in shake flask cultures, which is probably due to a better oxygenation of cultures in flasks than in deep-well plates where the ratio volume of culture/volume of container was of 1/2 instead of 1/10. However, levels of mannanase production were in both cases sufficient to deploy a high-throughput screening campaign.

Figure 1. Error-prone PCR strategy used in the study.

PCR1: error prone-PCR performed on paman5a (HM357135) and paman26a (HM357136); PCR2: PCR without mutation performed on Ura3d1 (selection marker), pPOX2 (inducible promotor of acyl-coA oxidase 2) and prepro Lip2 (secretion signal sequence); PCR3: overlapping PCR to reconstruct the entire sequence between zeta platforms. Primers used are listed in Table 3.

Construction of first-round mutagenesis libraries and screening

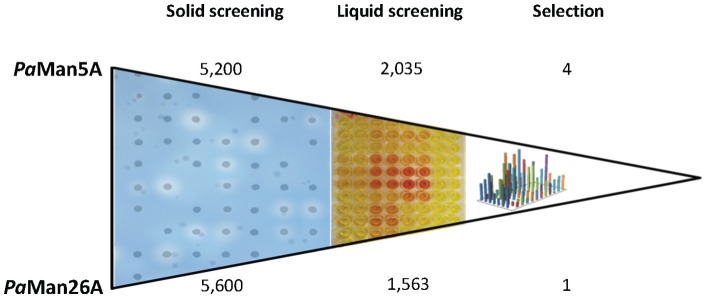

The objective of the directed evolution approach was to improve enzymatic activities of PaMan5A and PaMan26A, two endo-mannanases from Podospora anserina. The error-prone PCR mutagenesis round was carried out using the wild type genes as templates (GenBank HM357135 and HM357136 for paman5a and paman26a, respectively) and with the conditions appropriate to reach a number of mutations in a range of 2 to 5 mutations per kb. Indeed, a very low number of mutations per kb (i.e., below one mutation per kb) would result in too many active variants with unchanged activity, and a high number of mutations per kb would result in too many inactive clones as reported in [17] (>70% inactive clones for a mutation rate of 10 mutation per kb). In our study, subcloning and sequence analysis of a representative set of mutated genes from each library revealed that the mutation rates were in the desired range (i.e. 2.6 and 4.5 mutations per kb for PaMan5A and PaMan26A, respectively). Figure 2 shows a summary of the libraries screening and the number of variants selected at each step. Y. lipolytica transformation yielded about 5,200 and 5,600 clones for PaMan5A and PaMan26A, respectively. As reported in other studies [20], [27], [28], 5,000 variants was considered as a reasonable size of library to identify mutants displaying improved characteristics. The first step of the screening consisted in the selection of active clones on solid medium containing AZO-dyed galactomannan. Since we were looking for an activity improvement that was expected to be rather modest, halo-producing clones could not be screened only by comparing the size of halos but required a second step of screening. Culture-based screening was performed using our in-house robotic platform with about 2,000 and 1,500 mutants for PaMan5A and PaMan26A, respectively (Figure 2). Since the screening capability of this high-throughput system is 15 plates per day, ∼1,400 variants could be analysed in one day and the defined screening job (3,500 variants) was finished within 3 days. Among the best-performing clones that were further tested to confirm the enhancement of activity in liquid cultures, we finally selected four mutants of PaMan5A and one mutant of PaMan26A that displayed improved activity beyond the CV of wild-type mannanases (7.7 and 12.2%, respectively). The Y. lipolytica strain expressing the best PaMan26A variant displayed an increase of activity towards galactomannan of 147% compared to the strain expressing wild-type PaMan26A that corresponded to 12 CV. The Y. lipolytica strains expressing selected PaMan5A variants displayed also increased activity between 8 and 46% compared to the strain expressing wild-type PaMan5A that corresponded to 1.1 to 6 CV. Each of the mannanase-mutant genes was amplified from genomic DNA, subcloned and sequenced. As a result, one single (PaMan5A-G311S), two double (PaMan5A-K139R/Y223H, PaMan26A-P140L/D416G) and two triple mutants (PaMan5A-V256L/G276V/Q316H, PaMan5A-W36R/I195T/V256A) were created. Results are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2. Screening strategy and mutant selection.

The number of variants screened at each step is indicated at the top (PaMan5A) and at the bottom (PaMan26A) of the diagram.

Table 1. Mannanase activity of selected Y. lipolytica variants.

| Enzyme | Activity (U.ml−1) | CV (%) | Activity Improvement (%) |

| PaMan26A wt | 1.24±0.15 | 12.2 | - |

| PaMan26A-P140L/D416G | - | - | 147 |

| PaMan5A wt | 1.78±0.14 | 7.7 | - |

| PaMan5A-V256L/G276V/Q316H | - | - | 46 |

| PaMan5A-W36R/I195T/V256A | - | - | 9 |

| PaMan5A-K139R/Y223H | - | - | 20 |

| PaMan5A-G311S | - | - | 11 |

The mannanase activity was measured at 40°C in sodium acetate buffer 50 mM, pH 5.2 using 1% (w/v) galactomannan. The coefficient of variation (CV) was defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean and was calculated for each of the wild-type enzymes. wt, wild type.

Mutant production in P. pastoris and biochemical characterization

For mutant enzymes production, we used the P. pastoris expression system because (i) it yields higher expression levels than Y. lipolytica [29] and (ii) wild-type PaMan5A and PaMan26A were already successfully expressed to high yields in P. pastoris [10]. The ratio of mannanase production yields obtained in the culture medium with Y. lipolytica and P. pastoris was roughly 1∶10. All of the mutant enzymes were successfully produced in P. pastoris with yields of approximately 1 g per liter of culture and purified taking advantage of the (His)6-tag. SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified mutants compared to the wild type enzymes revealed similar apparent molecular masses (data not shown). Isoelectrofocusing analysis revealed that all of the mutants displayed similar pIs compared to wild-type enzymes except for the PaMan5A-W36R/I195T/V256A mutant that exhibited an increase of 0.3 unit (Figure S1). This increase is likely to be due to the incorporation of an arginine residue. Circular dichroism analysis of all selected mutants was also carried out to check the relative content of secondary structures in each mutant. PaMan26A and PaMan5A variants displayed the same profile compared to parental enzymes, suggesting that the folding of mutants were similar to the parental enzymes (data not shown). Regarding the pH and temperature profiles, no significant difference was observed between variants and parental enzymes (data not shown).

Kinetic parameters of mutants toward galactomannan

Each mutant was characterized using High Performance Anion Exchange Chromatography – Pulsed Amperometric Detection (HPAEC-PAD) to assess its ability to hydrolyze galactomannan and manno-oligosaccharides: mannopentaose (M5) and mannohexaose (M6) (Table 2). Regarding the M5 and M6 hydrolysis, PaMan26A-P140L/D416G exhibited 100% and 30% increase of k cat/KM toward M5 and M6, respectively. PaMan5A-V256L/G276V/Q316H and PaMan5A-W36R/I195T/V256A exhibited same hydrolysis profile as PaMan5A at 10 min or 20 min manno-oligosaccharide hydrolysis (data not shown) and therefore k cat/KM were considered unchanged and not determined. PaMan5A-K139R/Y223H revealed a decrease of k cat/KM of about 35% and 11% respectively. PaMan5A-G311S displayed an increased k cat/KM of about 37% and 12% towards M5 and M6, respectively.

Table 2. Kinetic constants of wild-type enzymes and selected variants toward galactomannan, mannohexaose (M6) and mannopentaose (M5).

| Galactomannan | M6 | M5 | ||||

| Enzyme | KM (mg.ml−1) | kcat (min−1) | k cat/KM (mg−1.ml.min−1) | k cat/KM (mg−1.ml.min−1) | ||

| PaMan26A wt | 2.4±0.3 | 3356±159 | 1413±155 | 7.6×105 | 3.8×105 | |

| 26-P140L/D416G* | 2.1±0.2 | 3860±80 | 1849±148 | 1.0×106 | 7.8×105 | |

| PaMan5A wt | 11.5±1.5 | 1674±138 | 147±19 | 3.0×106 | 9.2×105 | |

| 5-V256L/G276V/Q316H | 7.8±1.6 | 1493±167 | 197±38 | ND | ND | |

| 5-W36R/I195T/V256A* | 16.2±2.5 | 4199±438 | 263±41 | ND | ND | |

| 5-K139R/Y223H* | 6.7±0.5 | 1655±60 | 248±17 | 2.7×106 | 6.8×105 | |

| 5-G311S* | 1.5±0.4 | 1781±134 | 1247±292 | 3.4×106 | 1.2×106 | |

The kinetic parameters were determined at 40°C in sodium acetate buffer 50 mM, pH 5.2 as described in the Methods section. Paired t test was used to compare the kinetic parameters of mutants versus native enzyme. The difference was considered statistically significant when p<0.05 (*). wt, wild type.ND: not determined.

Regarding the KM apparent values, all of the mutants displayed improved apparent affinity for galactomannan. Although turn-over numbers of almost all of the mutant enzymes were similar to wild-type enzymes, the PaMan5A-W36R/I195T/V256A mutant displayed a 2.5-fold increase of turn-over toward galactomannan resulting in an overall catalytic efficiency improved by 1.8-fold. In terms of catalytic efficiency, the best-performing mutant was the PaMan5A-G311S mutant for which the single amino-acid substitution led to a 8.2-fold increase in k cat/KM due to a drastic improvement of KM whereas the k cat remained unchanged. Other PaMan5A mutants exhibited also to a lower extent increased k cat/KM towards galactomannan, i.e., between 32 and 79% improvement. The PaMan26A-P140L/D416G mutant, which is the unique mutant selected from the 5,600 PaMan26A variants screened, displayed an improved k cat/KM of approximately 30%. All of the mutants were subjected to a paired t-test in comparison with the corresponding native enzyme. Three out of four PaMan5A mutants and the PaMan26A mutant revealed p-values below 0.05 for galactomannan hydrolysis and were therefore considered statistically different from their native counterpart (Table 2).

Only sparse studies have previously led to the identification of mutants displaying such increase in catalytic efficiency. For example, several endoglucanase mutants with k cat/KM improvement between 15 and 80% were generated after three rounds of mutagenesis [26]. Song et al [20] identified several xylanase mutants with k cat/KM towards xylan increased in a range of 20 to 50% after several rounds of evolution.

Structure-function relationships of identified variants

Examination of the recently solved three-dimensional structures of PaMan5A and PaMan26A [24] revealed that some of the mutated residues are potentially important for enzyme function.

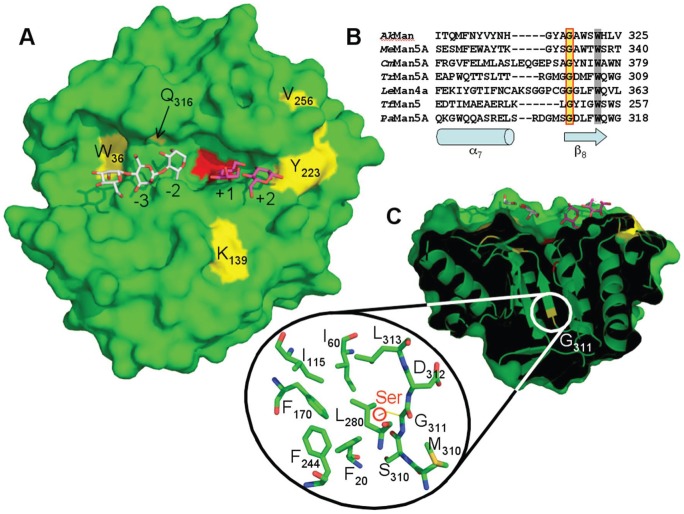

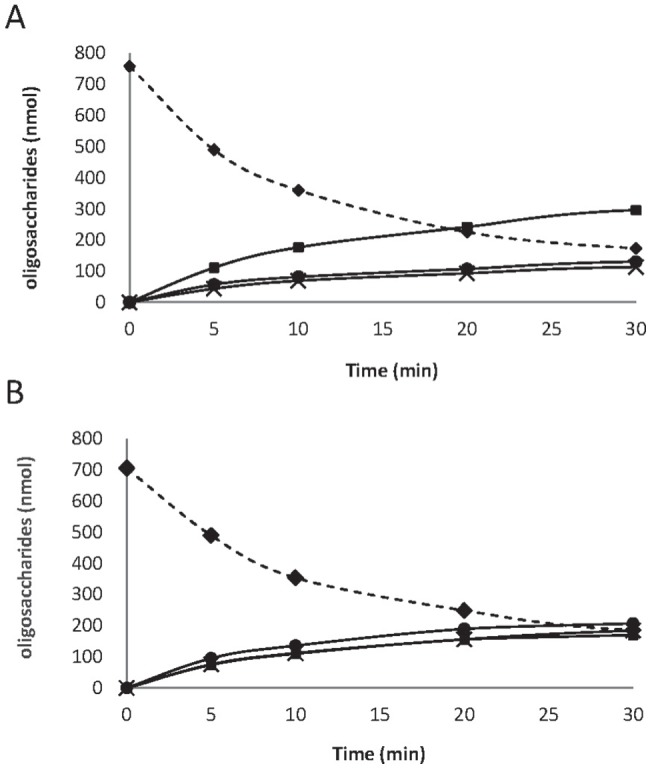

The localization of all of the mutated residues of the PaMan5A mutants revealed that five mutated residues (W36R, K139R, Y223H, V256A/L, and Q316H) out of eight are located within the active site cleft and three mutations are located inside the enzyme core (I195T, G276V and G311S). Three mutations were identified in the PaMan5A-W36R/I195T/V256A mutant, among which W36 and V256 that are located close to the catalytic site (Figure 3A) and I195T is located in the enzyme core (not shown). The W36 residue side chain lies at the bottom of the active site crevice and may contribute to the −4 subsite. Interestingly, the Val256 does not seem to be directly involved in the subsite organization of PaMan5A, but mutation of this residue were found in two distinct variants (PaMan5A-V256L/G276V/Q316H and PaMan5A-W36R/I195T/V256A), indicating a possible hot spot for enzyme improvement to further explore. Concerning the PaMan5A-K139R/Y223H mutant, analysis of the manno-oligosaccharides produced upon hydrolysis of M5 and M6 revealed a potential modification of substrate binding (Figure 4). Indeed, the wild type PaMan5A is known to produce mainly M3 from M6, with small amounts of M2 and M4 [24]. In the case of PaMan5A-K139R/Y223H, equimolar amount of M2, M3 and M4 were quantified (Figure 4), suggesting a displacement of the substrate binding from −3 to +3 subsites to −2 +4 subsites or −4 +2 subsites (Figure 3). Within the two mutations of mutant PaMan5A-K139R/Y223H, it is interesting to note that the Y223 residue is located nearby the +3 subsite. The substitution of the aromatic ring, involved in stacking interaction with the sugar, may contribute to the modification of substrate binding at this position (Figure 3). The single mutation of PaMan5A-G311S is located in the core of the enzyme within the start of β8-strand (Figure 3B). The G311 residue is strictly conserved among all of the GH5 mannanases of known structure. The G311 residue is conserved among GH5 mannanases within the start of the β8-strand and it should be noted that the last residue of this strand is the W315 residue (Figure 3B), which shapes the −2 subsite. The G311 residue is in close vicinity with a compact hydrophobic core made of residues F20, I60, I115, F170, F244, L280 and L313 (Figure 3C). It is difficult to determine the effect of this single substitution from a structural point of view, although we can hypothesize that the hydroxyl group of the serine residue may contribute to the modification of the β8-strand by interacting with the surrounding residues although circular dichroïsm analysis of the PaMan5A-G311S mutant revealed a similar profile compared to the parental enzyme, suggesting that its folding was similar to the parental enzyme (data not shown). Therefore the single mutation PaMan5A-G311S does not seem to modify the overall architecture of the enzyme but a slight movement of the β8-strand could move the W315 residue at the surface of the enzyme and explain the decreased KM.

Figure 3. Structural view of PaMan5A (PDB 3ZIZ) exhibiting substituted amino-acids.

A. Surface view of the catalytic cleft of PaMan5A with mannotriose modelled in the −2 and −3 subsites and mannobiose modelled in the +1 and +2 subsites. The structures of GH5 from T. reesei and T. fusca in complex with mannobiose and mannotriose, respectively, were superimposed on the top of the structure of PaMan5A to map the substrate-binding subsites. The two catalytic glutamate residues, E177 and E283, are coloured in red. The substituted amino-acids are labelled and coloured in yellow. B. Structural based sequence alignment of the region around position 311 (according to PaMan5A numbering) from Podospora anserina (PaMan5A), Aplysia kurodai (AkMan, PDB 3VUP), Mytilus edulis (MeMan5A, PDB 2C0H), Cellvibrio mixtus (CmMan5A, PDB 1UUQ), Trichoderma reesei (TrMan5A, PDB 1QNR), Lycopersicon esculentum (LeMan4A, PDB 1RH9) and Thermomonospora fusca (TfMan5, PDB 2MAN). Secondary structure elements, α-helix α7 and β-strand β8, are indicated below the sequences as a cylinder and an arrow, respectively. Strictly conserved residues, G311 and W315 (according to PaMan5A numbering), are shown with a yellow and a grey background, respectively. C. Surface view of PaMan5A rotated of about 90° along the horizontal axis. The front clipping plane has been moved in order to visualize the location of G311 inside the molecule. The zoom shows a compact hydrophobic core in the vicinity of G311.

Figure 4. Progress curves of the manno-oligosaccharides generated by the wild-type PaMan5A and the PaMan5A-K139R/Y223H variant upon hydrolysis of mannohexaose.

18.2 nM of the wild-type PaMan5A (A) and the PaMan5A-K139R/Y223H variant (B) were incubated with 1 mM of mannohexaose in acetate buffer pH 5.2 at 40°C. The amount of each manno-oligosaccharide, i.e., mannobiose (full circles), mannotriose (full squares), mannotetraose (crosses), and mannohexaose (full diamonds), is indicated during the course of the reaction.

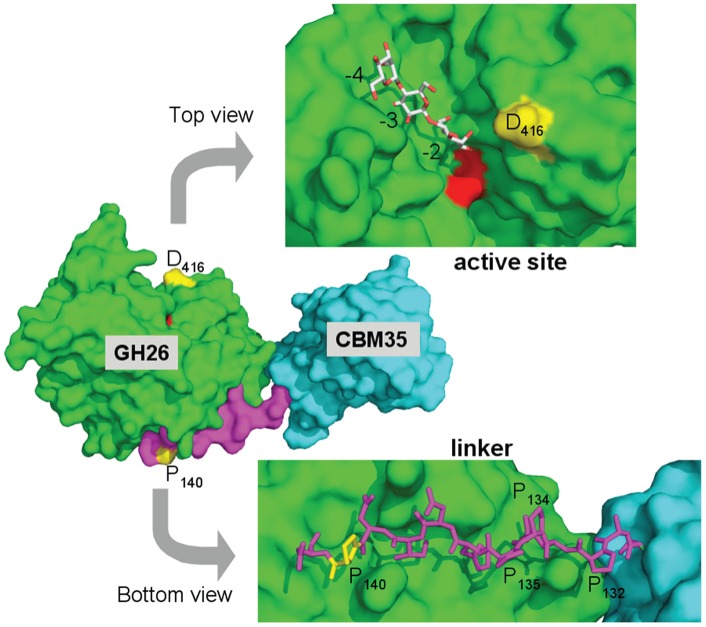

One of the most remarkable findings of this study is the activity increase of the PaMan26A-P140L/D416G mutant that contained only two mutations, i.e., one in the linker region (P140L) and one at the entrance of the active site (D416G) (Figure 5). The region from residue R133 to residue N141, which may be considered as the end of the linker, is tightly bound to the catalytic domain thanks to a dense network of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions [24]. Moreover, the PaMan26A linker sequence contains four proline residues (P132, P134, P135 and P140) out of 12 residues that may confer rigidity to the modular enzyme [24]. In the PaMan26A-P140L/D416G mutant, the P140 residue was substituted by a leucine residue, probably resulting in a decrease of linker rigidity that could partially explain the improved k cat/KM. The D416 amino-acid substitution is located at the edge of the catalytic cleft (Figure 5). The favourable mutation consisted in the removal of the carboxylic group since the D416 amino-acid was substituted by a glycine residue. We suggest that the lack of the carboxylic acid side chain may promote the entrance of the substrate into the active site.

Figure 5. Structural view of PaMan26A (PDB 3ZM8) exhibiting substituted amino-acids.

The central panel shows a surface view of the entire PaMan26A structure, which is composed of a carbohydrate binding module (CBM) belonging to the CBM35 family in cyan, a linker in violet and a catalytic domain belonging to the GH26 family in green. The two catalytic glutamate residues, E300 and E390, are coloured in red. The two substituted amino-acids, P140 and D416, are labelled and coloured in yellow. The top view represents the surface view of the catalytic cleft of PaMan26A rotated about 90° along the horizontal axis with mannotriose modelled into the −2 to −4 subsites. The structure of GH26 from C. fimi in complex with mannotriose was superimposed on the top of the structure of PaMan26A to map the substrate-binding subsites. The bottom view displays the PaMan26A linker (from residue 131 to residue 141) in stick representation. The molecule has been rotated of about 90° along the horizontal axis and in the opposite direction compared to the top view. The proline residues of the linker are labelled.

Conclusions

Activity improvement of fungal carbohydrate-active enzymes has typically met many obstacles, owing primarily to the lack of efficient expression systems and high-throughput screening methodologies. In this study, molecular engineering of two fungal mannanases was undertaken using random mutagenesis in the yeast Y. lipolytica. All of the selected mutants highlighted improved characteristics when compared to wild-type enzymes, thus validating the approach of mutagenesis and screening that were employed. Examination of the three-dimensional structures of PaMan5A and PaMan26A revealed several hot spots (i) around the active site of both mannanases, (ii) in the core region of PaMan5A and (iii) in the linker region of PaMan26A. The directed evolution strategy implemented in this study was very successful since a straightforward round of random mutagenesis yielded significantly improved variants that would have been difficult to predict using rational site-directed mutagenesis and structure-guided design.

Methods

Plasmids, strains and culture conditions

The growth media and culture conditions for the Y. lipolytica JMY1212 strain (Ura-, Leu+, ΔAEP, Suc+) have been previously described [30]. Briefly, the Y. lipolytica JMY1212 strain was cultured in YPD (10 g/l yeast extract, 20 g/l peptone, 20 g/l glucose) at 28°C, 130 rpm in baffled flasks or in Petri dishes containing YPD supplemented with agar (15 g/l). The plasmid used for expression in Y. lipolytica was JMP61 that displayed the POX2 promoter for induction by oleic acid [31] and the Zeta recombination platform for controlled monocopy integration in Y. lipolytica genome. Subcloning of parental genes was performed using the TOPO TA kit (Invitrogen, Cergy-Pontoise, France) and TOP10 E. coli competent cells (Invitrogen).

Construction of JMP61-paman5a and JMP61-paman26a plasmids and yeast transformation

PaMan5A and PaMan26A genes (paman5a [HM357135] and paman26a [HM357136], respectively) were amplified with primers listed in Table 3, starting from the pPICZαA-paman5a and the pPICZαC-paman26a plasmids [10]. Insertion of both genes in the JMP61 expression vector was performed using BamHI and AvrII restriction sites. Y. lipolytica Zeta competent cells were prepared using the lithium acetate method as described in le Dall et al [32].

Table 3. List of primers used in the study.

| Gene | PCR step | Primer name | Sequence (5′->3′) |

| paman5a | integration in JMP61 | GH5JMP61F 5′ | TTTGGATCCCTCCCCCAAGCACAA |

| GH5JMP61R 3′ | TTTCCTAGGCTACGCCGGGAGAGCATT | ||

| mutagenesis PCR (PCR1) | JMP61EvDF | GCAGAAGCGATTCGGATCC | |

| PCR2r | GGAGTTCTTCGCCCACCC | ||

| zeta platform PCR (PCR2) | PCR1d | GATCCCCACCGGAATTGC | |

| GH5EvDRev | GGCTGCTCCTCCACC | ||

| integration in pPICZαA | GH5-InFuFOR | GGCTGAAGCTGAATTCCTCCCCCAAGCACAAGGT | |

| GH5-InFuR | GAGTTTTTGTTCTAGACCCCGCCGGGAGAGCATT | ||

| paman26a | integration in JMP61 | JMP61-CBMGH26-F | TTTGGATCCAAGCCTTGTAAGCC |

| GH26-JMP61-Rev | TTTCCTAGGCTAACTCCTCCACCCCTGAAT | ||

| mutagenesis PCR (PCR1) | PCR1dtmutCBM-F | TTTCCAACCTCAACAACCCCAAC | |

| PCR2r | GGAGTTCTTCGCCCACCC | ||

| zeta platform PCR (PCR2) | PCR1d | GATCCCCACCGGAATTGC | |

| GH26EvDRev | GGAGTAGAGCTTCTT | ||

| integration in pPICZαA | GH26CBM-InFuFOR | GGCTGAAGCTGAATTCAAGCCTTGTAAGCCTCGT | |

| GH26InFuR | GAGTTTTTGTTCTAGACCACTCCTCCACCCCTGAAT | ||

| common | overlap PCR (PCR 3) | PCR1dL | CCGCTGTCGGGAACCGCGTTCAGGTGGAACAGG |

| PCR2rL | CCGCACTGAGGGCTTTGTGAGGAGGTAACGCCG |

Competent cells were immediately transformed with 500 ng NotI-linearized recombinant plasmid combined with 25 µg of salmon sperm DNA by heat shock at 39°C for 10 minutes and immediately recovered in 1.2 ml of 100 mM lithium acetate. Transformants were plated on YNB agar (1.7 g/l YNB, 10 g/l glucose, 5 g/l ammonium chloride, 2 g/l casamino acids, in 50 mM sodium–potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.8, 17 g/l agar) and incubated at 28°C for 48 hours.

Construction of mutagenesis libraries by error-prone PCR

Three PCR were carried out for each gene as shown in Figure 1 with primers listed in Table 3. Mutagenic PCR (PCR1) were performed using Genemorph II Random Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions using primers JMP61EvDF and PCR2r for paman5a and PCR1dtmutCBM-F and PCR2r for paman26a. The PCR contained 500 ng of parental gene, 200 µM dNTP, 0.25 µM primers and 2.5 units of Mutazyme. The PCR were made up to 50 µl and incubated at 95°C for 5 min and then at 95°C for 30 sec, 50°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 1 min and 30 sec for 40 cycles followed by 5 min at 72°C. PCR2 was carried out using HiFi polymerase (Invitrogen) to amplify the zeta platform without introducing any mutations. Primers used were PCR1d and GH5EvDRev for paman5a and PCR1d and GH26EvDRev for paman26a. PCR products were gel-extracted using Gel-Extraction kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) and a third overlap PCR (PCR3) was subsequently carried out using gel-extracted products of PCR1 and PCR2 to rebuild the whole zeta fragment containing mutant genes. The primers used for PCR3 were PCR1dL and PCR2rL for the two constructions. The overlap PCR was carried out using i-Star Max II DNA polymerase (Intron Biotechnology, Boca Raton, FL).

PCR3 products were subsequently transformed into Y. lipolytica as described above and plated onto YNB in QTrays plates (Corning Corp, NY, USA) at a density of about 500 colonies par plate and incubated for 48 hours at 28°C.

Screening of mutagenesis libraries

Agar plate-based screening

The Ura-positive Y. lipolytica transformants obtained from mutagenesis libraries were subsequently gridded on YNB agar medium containing oleic acid (1% v/v, Sigma) and Azo-galactomannan (0.2% w/v, Megazyme) using a QPixII colony picker (Genetix, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The plates were further incubated at 28°C for 48 hours. Mannanase activity was visualized as clear halos around colonies within a blue background.

Liquid culture-based screening

Mannanase-positive colonies were picked on OmniTrays (Nunc, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Courtaboeuf, France) containing YPD agar and incubated for 48 hours at 328°C. Further screening was performed as described in [26]. Briefly, 96-well preculture plates containing 200 µl YPD were inoculated by individual colonies. The precultures were incubated at 800 rpm and 28°C overnight in a Microtron incubator (Infors HT, Switzerland). For expression of recombinant genes, 20 µl of each preculture were transferred in 1 ml of YTO medium (10 g/l yeast extract, 20 g/l% w/v tryptone, 2% oleic acid, in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.8) in 96-deep-well plates. Cultures were further incubated at 28°C with shaking at 800 rpm. After 4 days induction, the supernatants containing mutant enzymes were recovered by centrifugation (10 min, 3500 rpm) and endo-mannanase activity towards galactomannan was determined from DNS assay as described before [23]. Briefly, 10 µl of culture supernatant were incubated with 190 µl of 1% (w/v) galactomannan in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5) at 40°C. 80 µl of reaction mixture was recovered and reaction was terminated by addition of same volume of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent at 1% (w/v) in 96 well PCR plates. Samples were heated at 95°C for 10 min and DO540 was measured relative to a mannose standard curve (1 to 20 mM).

Wild-type and mutant enzymes large-scale production

For heterologous production of PaMan5A and PaMan26A mutant proteins, the selected genes were amplified from genomic DNA using GH5-InFuFOR and GH5-InFuR for PaMan5A and GH26CBM-InFuFOR and GH26-InFuR for PaMan26A, respectively, listed in Table 3 and transferred into the pPICZαA plasmid using InFusion kit (Clontech, Takara). Resulting plasmids were transformed into P. pastoris and protein productions and purification were carried out as described before [10].

Biochemical and biophysical characterization

Protein concentration was determined by using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit with bovine serum albumin as standard (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la Coquette, France) and UV absorbance at 280 nm. SDS-PAGE was performed in 10% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad) using a Pharmacia LMW electrophoresis calibration kit (GE Healthcare, Buc, France). Native IEF was carried out at 4°C in the Bio-Rad gel system, using pI standards ranging from 4.45 to 8.2. IEF gel was coloured with IEF staining solution (0.04% Coomassie Blue R250, 0.05% Cocrein Scarlett, 10% acetic acid, 27% isopropanol).

Characterization and kinetic properties of individual enzymes

Determination of kinetic parameters on galactomannan was performed using DNS activity assay. Unless otherwise indicated, assay mixtures contained substrate and suitably diluted enzyme in sodium acetate buffer 50 mM, pH 5. Briefly, 1 µg of enzyme was mixed with 190 µl of galactomannan (Megazyme International, Wicklow, Ireland) using a range of substrate concentration from 1 to 20 mg.ml−1 (eight concentrations) and incubated at 40°C for 5 minutes. Reactions were performed in triplicate independent experiments. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 300 µl of 1% DNS reagent and samples were heated at 95°C for 10 minutes. DO540 was measured relative to a mannose standard curve (0 to 20 mM). One unit of endo-mannanase activity was defined as the amount of protein that released 1 µmol of sugar monomers per min. The kinetic parameters were estimated using weighted nonlinear squares regression analysis with the Grafit software (Erithacus Software, Horley, UK).

Analysis of initial sugar release by HPAEC-PAD and kinetic parameters measurement

Monosaccharide and oligosaccharides generated after hydrolysis of manno-oligosaccharides (M5 and M6, Megazyme) were analysed using HPAEC-PAD. 10 µl of suitably-diluted enzyme were incubated at 40°C for various time lengths with 190 µl of 1 mM substrate in 50 mM acetate buffer pH 5.2. At each time point, 10 µl of reaction mixture were recovered and the reaction was terminated by the addition of 90 µl of 180 mM NaOH. For HPAEC analysis, 10 µl were injected and elution was carried out as described in [10]. Calibration curves were plotted using β-1,4-manno-oligosaccharides as standards from which response factors were calculated (Chromeleon program, Dionex) and used to estimate the amount of products released in test incubations. All the assays were carried out at least in duplicates. The specificity constants were calculated using the Matsui equation [24], [33].

Supporting Information

Isoelectrofocusing analysis of Pa Man5A and Pa Man26A variants. 1: pI marker (values are on the left); 2: PaMan26A wild-type; 3: PaMan26A-P140L/D416G; 4: PaMan5A wild-type; 5: PaMan5A-V256L/G276V/Q316H; 6: PaMan5A-W36R/I195T/V256A; 7: PaMan5A-K139R/Y223H; 8: PaMan5A-G311S.

(EPS)

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank M. Haon and S. Grisel for their assistance in the purification of mutants. C. Montanier and C. Dumon (LISBP, INSA, Toulouse, France), P.M. Coutinho (AFMB, CNRS, Marseille, France), N. Lopes Ferreira (IFPEN, Rueil-Malmaison, France) and D. Navarro (INRA, Marseille, France) are acknowledged for helpful discussions and C.B. Faulds for proofreading of the manuscript. The plasmids and strains for Yarrowia expression experiments were generously provided by JM Nicaud (MICALIS, INRA-AgroParisTech, France) and A Marty (LISBP, INSA, Toulouse, France). The high-throughput screening work was carried out at the Laboratory for BioSystems & Process Engineering (Toulouse, France) with the equipments of the ICEO facility, dedicated to the screening and the discovery of new and original enzymes. This work was carried out as part of the FUTUROL PROJECT and the authors want to thank OSEO Innovation for its financial support.

Funding Statement

ICEO is supported by grants from the Région Midi-Pyrénées, the European Regional Development Fund and the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA). This work was carried out as part of the FUTUROL PROJECT and the authors want to thank OSEO Innovation for its financial support. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Wiedenhoeft AC, Miller RB (2005) Structure and Function of Wood. In: Rowell RM, editor. Handbook of wood chemistry and wood composites. CRC Press. 9–33.

- 2. Scheller HV, Ulvskov P (2010) Hemicelluloses. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61: 263–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Salmén L (2004) Micromechanical understanding of the cell-wall structure. C R Biol 327(9–10): 873–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cantarel BL, Coutinho PM, Rancurel C, Bernard T, Lombard V, et al. (2009) The Carbohydrate-Active enZyme database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res 37: 233–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Carbohydrate-Active enZymes Database [www.cazy.org].

- 6. Sachslehner A, Foidl G, Foidl N, Gübitz G, Haltrich D (2000) Hydrolysis of isolated coffee mannan and coffee extract by mannanases of Sclerotium rolfsii . J Biotechnol 80: 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Montiel MD, Rodriguez J, Perez-Leblic MI, Hernandez M, Arias ME, et al. (1999) Screening of mannanases in actinomycetes and their potential application in the bleaching of pine Kraft pulps. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 52: 240–245. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Do BC, Dang TT, Berrin JG, Haltrich D, To KA, et al. (2009) Cloning, expression in Pichia pastoris, and characterization of a thermostable GH5 mannan endo-1,4-β-mannosidase from Aspergillus niger BK01. Microb Cell Fact 8: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pham TA, Berrin JG, Record E, To KA, Sigoillot JC (2010) Hydrolysis of softwood by Aspergillus mannanase: role of a carbohydrate-binding module. J Biotechnol 148: 163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Couturier M, Haon M, Coutinho P, Henrissat B, Lesage-Meessen, et al (2011) Podospora anserina hemicellulases potentiate the Trichoderma reesei secretome for saccharification of lignocellulosic biomass. Appl Environ Microbiol 77(1): 237–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chauhan PS, Puri N, Sharma P, Gupta N (2012) Mannanases: microbial sources, production, properties and potential biotechnological applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 93(5): 1817–1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Merino ST, Cherry J (2007) Progress and challenges in enzyme development for biomass utilization. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 108: 95–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Himmel EM, Picataggio SK (2008) Biomass Recalcitrance: Deconstructing the Plant Cell Wall for Bioenergy. In: Himmel EM, editor. Biomass Recalcitrance: Deconstructing the Plant Cell Wall for Bioenergy. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 1–6.

- 14. Margeot A, Hahn-Hagerdal B, Edlund M, Slade R, Monot F (2009) New improvements for lignocellulosic ethanol. Curr Opin Biotechnol 20: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tailford LE, Ducros VM, Flint JE, Roberts SM, Morland C, et al. (2009) Understanding how diverse beta-mannanases recognize heterogeneous substrates. Biochemistry 48(29): 7009–7018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hekmat O, Lo Leggio L, Rosengren A, Kamarauskaite J, Kolenova K, et al. (2010) Rational engineering of mannosyl binding in the distal glycone subsites of Cellulomonas fimi endo-beta-1,4-mannanase: mannosyl binding promoted at subsite −2 and demoted at subsite −3. Biochemistry 49(23): 4884–4896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang XJ, Peng YJ, Zhang LQ, Li AN, Li DC (2012) Directed evolution and structural prediction of cellobiohydrolase II from the thermophilic fungus Chaetomium thermophilum . Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 95(6): 1469–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heinzelman P, Snow CD, Wu I, Nguyen C, Villalobos A, et al. (2009) A family of thermostable fungal cellulases created by structure-guided recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(14): 5610–5615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. García-Ruiz E, Maté D, Ballesteros A, Martinez AT, Alcalde M (2010) Evolving thermostability in mutant libraries of ligninolytic oxidoreductases expressed in yeast. Microb Cell Fact 9: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Song L, Siguier B, Dumon C, Bozonnet S, O'Donohue MJ (2012) Engineering better biomass-degrading ability into a GH11 xylanase using a directed evolution strategy. Biotechnol Biofuels 5(1): 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin L, Meng X, Liu P, Hong Y, Wu G, et al. (2009) Improved catalytic efficiency of endo-β-1,4-glucanase from Bacillus subtilis BME-15 by directed evolution. Appl Environ Microbiol 82: 671–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Andrews SR, Taylor EJ, Pell G, Vincent F, Ducros V, et al. (2004) The use of forced protein evolution to investigate and improve stability of family 10 xylanases. J Biol Chem 279(52): 54369–54379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Couturier M, Roussel A, Rosengren A, Leone P, Stålbrand H, et al. (2013) Structural and biochemical analyses of glycoside hydrolase families 5 and 26 beta-(1,4)-mannanases from Podospora anserina reveal differences upon manno-oligosaccharides catalysis. J Biol Chem 288(20): 14624–14635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Duquesne S, Bordes F, Fudalej F, Nicaud JM, Marty A (2012) The yeast Yarrowia lipolytica as a generic tool for molecular evolution of enzymes. Methods Mol Biol 861: 301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Emond S, Montanier C, Nicaud JM, Marty A, Monsan P, et al. (2010) New efficient recombinant expression system to engineer Candida antartica lipase B. Appl Environ Microbiol. 76(8): 2684–2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liang C, Fioroni M, Rodríguez-Ropero F, Xue Y, Schwaneberg U, et al. (2011) Directed evolution of a thermophilic endoglucanase (Cel5A) into highly active Cel5A variants with an expanded temperature profile. J Biotechnol 154(1): 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen Y, Zhang B, Pei H, Lv J, Yang W, et al. (2012) Directed evolution of Penicillium janczewskii zalesk α-galactosidase toward enhanced activity and expression in Pichia pastoris . Appl Biochem Biotechnol 168(3): 638–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boonvitthya N, Bozonnet S, Burapatana V, O'Donohue MJ, Chulalaksananukul W (2013) Comparison of the heterologous expression of Trichoderma reesei endoglucanase II and cellobiohydrolase II in the yeasts Pichia pastoris and Yarrowia lipolytica . Mol Biotechnol 54(2): 158–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bordes F, Fudalej F, Dossat V, Nicaud JM, Marty A (2007) A new recombinant protein expression system for high-throughput screening in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica . J Microbiol Meth 70(3): 493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nicaud JM, Madzak C, van den Broek P, Gysler C, Duboc P, et al. (2002) Protein expression and secretion in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica . FEMS Yeast Res 2(3): 371–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Le Dall MT, Nicaud JM, Gaillardin C (1994) Multiple-copy integration in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica . Curr Genet 26(1): 38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Matsui I, Ishikawa K, Matsui E, Miyairi S, Fukui S, et al. (1991) Subsite structure of Saccharomycopsis alpha-amylase secreted from Saccharomyces cerevisiae . J Biochem 109: 566–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Isoelectrofocusing analysis of Pa Man5A and Pa Man26A variants. 1: pI marker (values are on the left); 2: PaMan26A wild-type; 3: PaMan26A-P140L/D416G; 4: PaMan5A wild-type; 5: PaMan5A-V256L/G276V/Q316H; 6: PaMan5A-W36R/I195T/V256A; 7: PaMan5A-K139R/Y223H; 8: PaMan5A-G311S.

(EPS)