Abstract

The discovery of new drugs is often propelled by the increasing resistance of parasites to existing drugs and the availability of better technology platforms. The area of microfluidics has provided devices for faster screening of compounds, controlled sampling/sorting of whole animals, and automated behavioral pattern recognition. In most microfluidic devices, drug effects on small animals (e.g., Caenorhabditis elegans) are quantified by an end-point, dose response curve representing a single parameter (such as worm velocity or stroke frequency). Here, we present a multi-parameter extraction method to characterize modes of paralysis in C. elegans over an extended time period. A microfluidic device with real-time imaging is used to expose C. elegans to four anthelmintic drugs (i.e., pyrantel, levamisole, tribendimidine, and methyridine). We quantified worm behavior with parameters such as curls per second, types of paralyzation, mode frequency, and number/duration of active/immobilization periods. Each drug was chosen at EC75 where 75% of the worm population is responsive to the drug. At equipotent concentrations, we observed differences in the manner with which worms paralyzed in drug environments. Our study highlights the need for assaying drug effects on small animal models with multiple parameters quantified at regular time points over an extended period to adequately capture the resistance and adaptability in chemical environments.

INTRODUCTION

Parasitic nematodes have adopted a range of infection, survival, and propagation strategies within hosts of interest, including humans, domestic animals (e.g., cows, pigs, sheep, horses), and agricultural plants (e.g., soybean, corn, rice, potato).1, 2, 3, 4, 5 In particular, intestinal nematodes affect over one-third of the human population and have a negative socioeconomic impact on our society.6, 7 Studies have shown that neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) arising from intestinal nematodes can affect human growth, nutrition, cognition, productivity, intelligence, and earnings. These effects are more pronounced in the poorest countries of the world where a population is strangled in poverty, low performance, and prolonged diseased state.4, 6

Classes of compounds called anthelmintics have been developed and studied for the treatment of intestinal nematodes.4, 8, 9 In the absence of available vaccines, anthelmintic chemotherapy is the only choice for the control of intestinal infection in humans and livestock. Two of these classes of drugs have been approved for use by the World Health Organization: benzimidazoles and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) agonists. The common benzimidazoles are mebendazole and albendazole.10 The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists are grouped under two receptors subtypes they target: L-type and N-type.8 While levamisole and pyrantel are examples of L-type nAChR agonists, methyridine is an example of N-type nAChR agonist.7, 9, 11 Tribendimidine is relatively understudied and its mechanism of action is shown to be similar to levamisole and pyrantel.6, 12 With slow progress in the discovery of new anthelmintics, parasitic worms have developed varying levels of resistance to these compounds.4 In fact, multidrug resistance in parasitic worms is now recognized as a prevalent global menace that overwhelms basic research in chemotherapeutic agents.4, 12, 13, 14

Platforms to investigate the efficacy and resistance of anthelmintics are dependent on the choice of the biological host under study. In vivo animal assays are undoubtedly the best way to test parasitic worms in their natural growth environment.5, 15, 16 These assays, however, require large quantities of the compounds, huge spaces to house the animals, long wait times, and thus higher research costs. Tests on smaller rodents such as mice and chicken are pragmatic but require about 100 mg of the chemical and are impractical for any large-scale random experiments with multiple chemicals. For these reasons, in vitro assays are the preferred choice in parasitology, especially for primary screening. Standard in vitro assays measure the egg count, larvae development, migration through membrane filters, and electrophysiological signals of muscle tissues and ion channels.13, 17, 18

Caenorhabditis elegans is an established small animal model in parasitology for studying novel drug targets and modes of drug action.14, 19, 20, 21 The key reasons that contribute to its wide acceptability are its matured genetics, short lifespan, small size, and conserved genes through generations. Moreover, the relative ease of culturing C. elegans on agarose plates under standard laboratory conditions is in contrast to culturing parasitic worms that have complex life cycles.4, 22, 23, 24 In this context, microfluidics has served as an enabling technology to study the effects of different drugs and toxins on single or multiple C. elegans.25, 26, 27 Microfluidic devices have integrated various techniques (e.g., droplet generation, automated valve operations, suction, image recognition, laser ablation) to demonstrate high-throughput methods of loading, immobilizing, sorting, and phenotyping worm populations.28, 29 While these technological advancements are commendable, it is reasonable to state that almost all microfluidic-enabled drug studies on C. elegans portray the drug effect using a single parameter measured at a finite time (e.g., velocity, stroke frequency).30, 31 Macroscopic, inhibition migration assays also count the percentage of worms surviving a chemical media within a finite time and plot the data as a dose response curve.7, 9, 11, 17 Are there other ways to characterize drug effects in these animals besides using a single parameter measured at end-points of the experiments? If different drugs are chosen at the same potency level, will they all exhibit a similar response on worm populations through the exposure time? We hypothesized that the effect of a certain drug could change over the length of experiment (as C. elegans is known to adapt to their environment)32 and quantifying the patterns of worm adaptation could be used as a means to differentiate different drugs.

To test the above hypothesis, we used a two-dimensional microfluidic platform25 with real-time imaging and a custom worm tracking software. Four anthelmintics are chosen that act on the neuromuscular system of the C. elegans: pyrantel, levamisole, methyridine, and tribendimidine. In each case, the drug concentration used is EC75 or where 75% of worms are responsive to the drug. The worms are exposed to the individual drugs in a microfluidic device and their activity is recorded for 40 min. Upon initial exposure, an active worm shows three types of movement patterns; crawling, curling, and flailing. After prolonged exposure, the active worm shows periods of being immobile before finally succumbing to the drug. We characterize these behavioral changes by a set of parameters and compared the results among the four drugs. Finally, with an attempt to show the usefulness of this characterization technique for future drug screening, we justify our findings about the efficacy of individual drugs using previous literature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Device fabrication

The microfluidic device is fabricated using soft lithography.25, 26 The device design is drawn in AutoCADTM and sent out to an outside vendor (Fineline ImagingTM) for printing the physical mask. A UV-sensitive polymer, SU-8, is spin-coated on a clean, 3-in. silicon wafer to create a 80 μm thick layer. The SU-8 is photolithographically patterned with features on the physical mask and developed. Then, particle desorption mass spectrometry (PDMS) polymer is poured on the SU-8 master mold and allowed to dry overnight in a low-pressure chamber at room temperature. The dried PDMS is peeled off the SU-8 master mold, punched with holes for the fluidic ports, and irreversibly bonded to a glass slide—thus creating our microfluidic device. The SU-8 master mold is re-used multiple times to create new PDMS structures. Each microfluidic device, however, is used only once for a single experiment.

Experimental setup

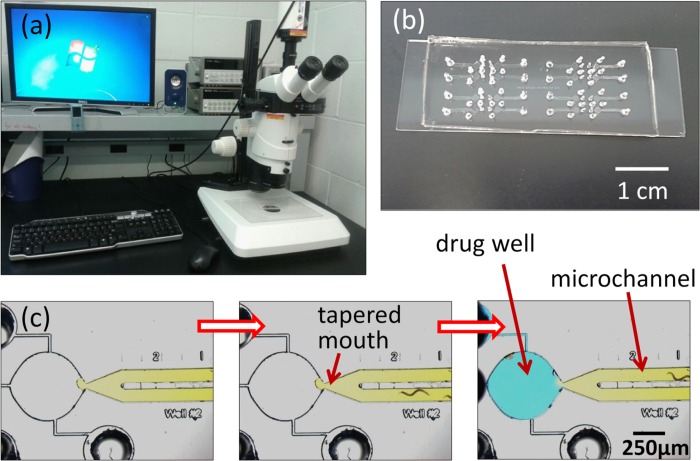

The microfluidic device is physically taped to a microscope stage and filled in a two-step procedure as shown in Fig. 1. The filling procedure is modified from our previous work.25 Earlier, we filled the straight microchannels with agarose gel and then filled the drug well with the drug solution. Worms were drawn into the microchannel and drug well using electrotaxis. Electric fields were continuously applied through the experiment to prevent worms from leaving the drug well. Here, the filling procedure was changed to apply electric fields only in the beginning of the experiment. In the first step, 0.8% agarose gel is loaded in a 1 ml syringe and slowly filled into the straight microchannel. The filling is stopped when the forward profile of agarose gel, observed under the microscope, reaches the tapered mouth of the microchannel. L4-stage C. elegans are picked from a culture plate with a sterilized wire and dropped at the input port. After a wait time of around 5–7 min, the worms penetrate the agarose gel, enter the microchannel, and migrate towards the tapered mouth. As the drug well is filled with air, the worms are restricted in the microchannel. In the second step, anthelmintic solution under test is prepared to a pre-specified concentration and filled in the drug well through a side port. Specifically, in the cases of levamisole, pyrantel, and methyridine, the drug well is filled with a mixture of 0.8% agarose prepared in M9 buffer and the anthelmintic. In the case of tribendimidine, a mixture of 0.8% agarose prepared in M9 buffer and the anthelmintic dissolved in 1% Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is used. For control experiments, 0.8% agarose in M9 buffer (with and without 1% DMSO) is used. We previously concluded that there is minimal diffusion of fluorescein from the drug well during a 45-min experiment.25

Figure 1.

Images of the experimental setup. (a) A stereozoom microscope with a computer-controlled camera is used to record and analyze real-time videos of worms in microfluidic devices. (b) Snapshot of a microfluidic chip comprising multiple devices fabricated in PDMS polymer and bonded to a glass slide. (c) A magnified image of a single microfluidic device comprising a straight microchannel that merges into a circular drug well through a tapered mouth. The empty device (left) is first filled with 0.8% agarose gel (mixed with yellow food dye here) and worms are allowed to enter through the input port (middle). Thereafter, the drug solution in agarose gel (mixed with blue food dye here) is filled in the drug well (right).

To attract the worms to enter into the drug well, on-chip electrotaxis is used.25 Two platinum electrodes are inserted in the agarose gel, one in the input port and one in the side port, and connected to a d.c. voltage supply by electrical cables. The net resistance between the platinum electrodes is measured to ensure there is a finite resistance of around 1–2 MΩ. An electric field is applied (∼5 V/cm) between the two electrodes and worms are coaxed into entering the drug well. From placing the worms on the input port to the start of data collection, the wait time is around 10 min. This time also allows the animals to acclimatize to the microfluidic environment. A Leica MZ16 stereozoom microscope is connected with a high-speed QImaging camera for real-time recording of worm behavior in the drug well. The QCapture software is programmed to record grayscale images of the drug well (every second) for a period of 40 min. Subsequently, the images are stitched into a single.avi file for data analysis. Each experiment is conducted with a certain number of worms (n ≅ 3 to 5) and repeated over at least 4 independent trials (N > = 4). With every drug test, control experiments are conducted in parallel. Statistical analysis on the data is performed using the GraphPad Prism software.

RESULTS

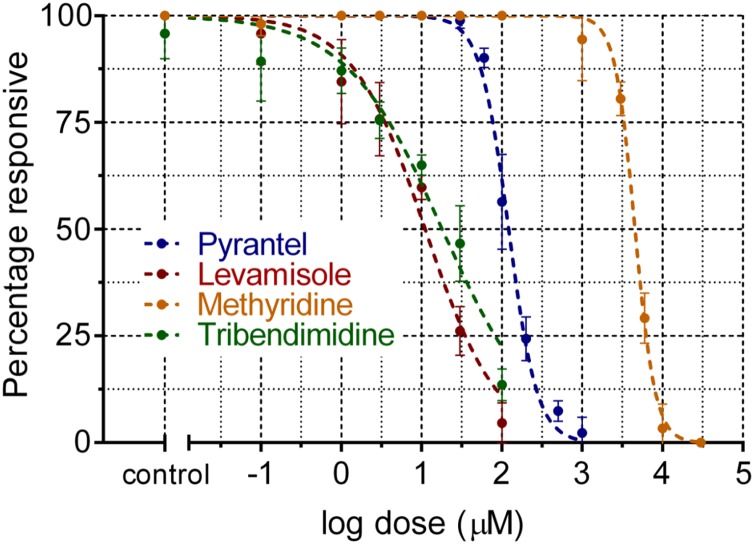

Previously, we reported the dose response (i.e., percentage of worms responsive to the applied electric field) of C. elegans upon exposure to levamisole.25 Using a similar protocol, experiments are conducted with three other anthelmintics (tribendimidine, pyrantel, and methyridine) and the C. elegans dose response is plotted in Fig. 2. To characterize the mode of paralysis in each drug, we chose a critical concentration where 25% of the worms are responsive to the applied electric field (i.e., where 75% of the worms are responsive to the drug, EC75). At EC100, worms paralyzed within a very short time to allow any characterization of drug effects; while at EC50, worms took over an hour to paralyze resulting in larger videos and longer analysis time. We chose EC75 as a reasonable concentration for drug potency as most worms paralyzed within 20–25 min with adequate time for exhibiting their drug response. From Fig. 2, this concentration for each drug is as follows: 30 μm levamisole, 100 μm tribendimidine, 150 μm pyrantel, and 10 mM methyridine. Next, we show that even at these equipotent concentrations, each drug have a distinct signature effect on worm populations observed over the entire experimental time.

Figure 2.

The dose response of C. elegans (represented as the percentage of worms responsive to electrical fields) is plotted for the four drugs used: pyrantel, levamisole, methyridine, and tribendimidine.

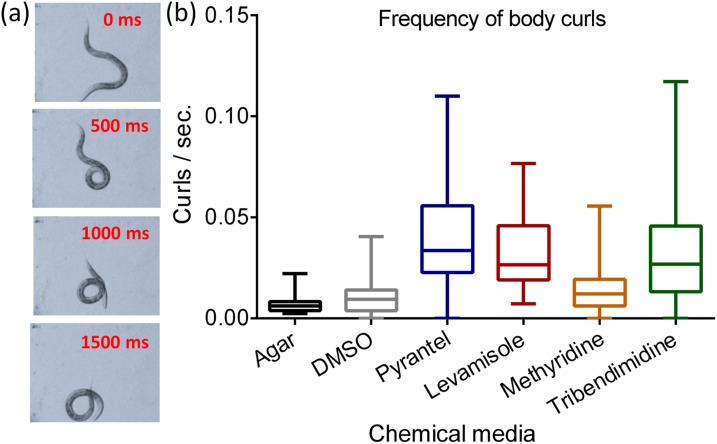

Frequency of body curls

One of our first observations indicated that worms tend to curl more often in drug environments than in control conditions. Fig. 3a shows a series of images to describe the progression of a curl exhibited by a sample worm in the microfluidic drug well. For our analysis, a curl is defined as an event that occurs when a worm's head touches or overlaps its tail. Using this definition, we manually count the total number of curls exhibited by an actively moving worm before it eventually paralyzes. Thereafter, the frequency of body curls (i.e., number of curls per second) is calculated by dividing the total number of curls by the total active time. The frequency of body curls is calculated as follows: 0.007 ± 0.005 for agar, 0.010 ± 0.010 for DMSO, 0.042 ± 0.030 for pyrantel, 0.031 ± 0.020 for levamisole, 0.014 ± 0.010 for methyridine, and 0.032 ± 0.026 for tribendimidine. In Fig. 3b, we plot the frequency of body curls as a box plot representation. Here, the bottom and top of each box correspond to the first and third quartiles, respectively, while the horizontal line inside the box denotes the median. The ends of whiskers are the minimum and maximum values of the data set. We compared the results of pyrantel, levamisole, and methyridine with their corresponding control (i.e., 0.8% agarose) and tribendimidine with its control (i.e., 0.8% agarose and 1% DMSO). There is no significant difference between the two control groups. However, the curl frequency is significantly higher in pyrantel and levamisole (p < 0.0001). Between DMSO and tribendimidine, we observed a significantly higher curl frequency in tribendimidine (p < 0.0001). The curl frequency is significantly lower in methyridine than in pyrantel, levamisole, and tribendimidine (p < 0.0001). This indicates that curling is not as predominant in methyridine as in other compounds. To describe the action of methyridine and to further differentiate among other drugs, we needed more parameters that could be extracted from recorded videos.

Figure 3.

Body curls in actively moving C. elegans upon exposure to anthelmintics. (a) Snapshots of a representative worm (every 500 ms) as it curls its body such that the head touches or overlaps its tail. (b) Frequency of body curls (i.e., the number of curls divided by the total time a worm stays active) is plotted for the four drugs and control conditions (i.e., in 0.8% agarose gel and DMSO).

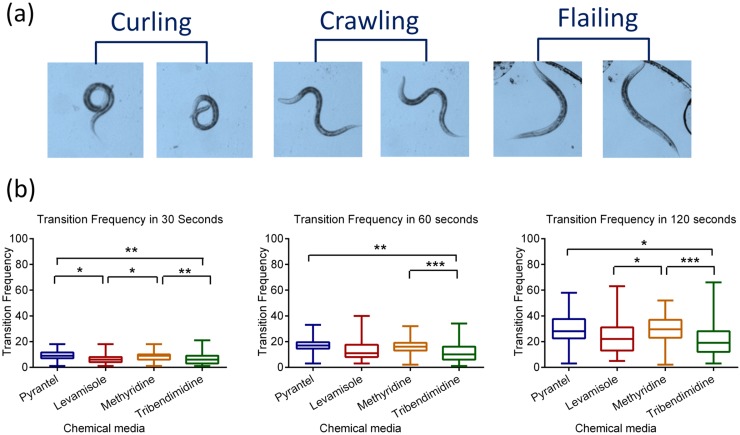

Mode transitions in an actively moving worm: Crawling, curling, or flailing

Besides frequent curling actions, an actively moving worm exhibits changes from its natural sinusoidal movement when exposed to drug environments. As shown in Fig. 4a, we categorize the nature of a worm's body displacement into three modes: crawling, curling, and flailing. Crawling is the undulatory, sinusoidal movement of a worm that results in forward or backward locomotion.33 Curling, as defined earlier, occurs when the worm's head touches or overlaps its tail. Flailing happens when a worm oscillates its body in half waves about a fixed location and is an unusual swimming-like behavior we observed in 0.8% agarose gel.

Figure 4.

Mode transitions between crawling, curling, and flailing. (a) Snapshots of representative worms during curling (head coiled to or beyond the tail), crawling (sinusoidal movement), and flailing (swimming movement with no net displacement). (b) Boxplot representations of the transition frequency (rate of switching between crawling, curling, and flailing) within 30 s (left), 60 s (middle), and 120 s (right) from the time of entering the drug well.

During an experiment, an active worm may exhibit any of the three abovementioned modes of movement (i.e., crawling, curling, and flailing). We manually counted the transitions made by an active worm amongst the three modes of movement. The number of mode transitions is counted within three time periods (30 s, 60 s, and 120 s) from the instance a worm enters into the drug well. A transition frequency is calculated by dividing the number of mode transitions by the time periods of observation. These data are plotted in Fig. 4b. The transition frequency is significantly higher in methyridine than in tribendimidine (p < 0.01 in 30 s, p < 0.001 in 60 and 120 s). The transition frequency is also significantly higher in pyrantel than in tribendimidine (p < 0.05 in 30 s, p < 0.01 in 60 and 120 s). Between levamisole and methyridine, there is significant difference in the 30 s and 120 s periods (p < 0.05). Interestingly, worms exhibited more frequent flailing motion in methyridine than in the other three drugs. In control tests with agar (data not shown), there are no mode transitions because all worms are seen crawling with no curling or flailing.

Immobilization patterns leading to paralysis: Being active, temporarily, or permanently immobilized

As the time of exposure increases, a drug may cause an actively moving worm to show periods of being (partially or completely) immobilized. We grouped these immobilization patterns into three categories: being active, temporarily immobilized or permanently immobilized. From our definition, a worm is considered active (or actively moving) if its entire body is displaced from its original location within a given timeframe (1 s in our case). A worm is permanently immobilized if its entire body remains stationary for at least 600 s, after which we denote the worm as being paralyzed. Our videos indicate that worms that remained immobilized for 600 s never recovered through the length of experiment. A worm is temporarily immobilized if parts of its body (and not the entire body) are still moving or if it can become active after being completely immobile for a certain time period (less than 600 s).

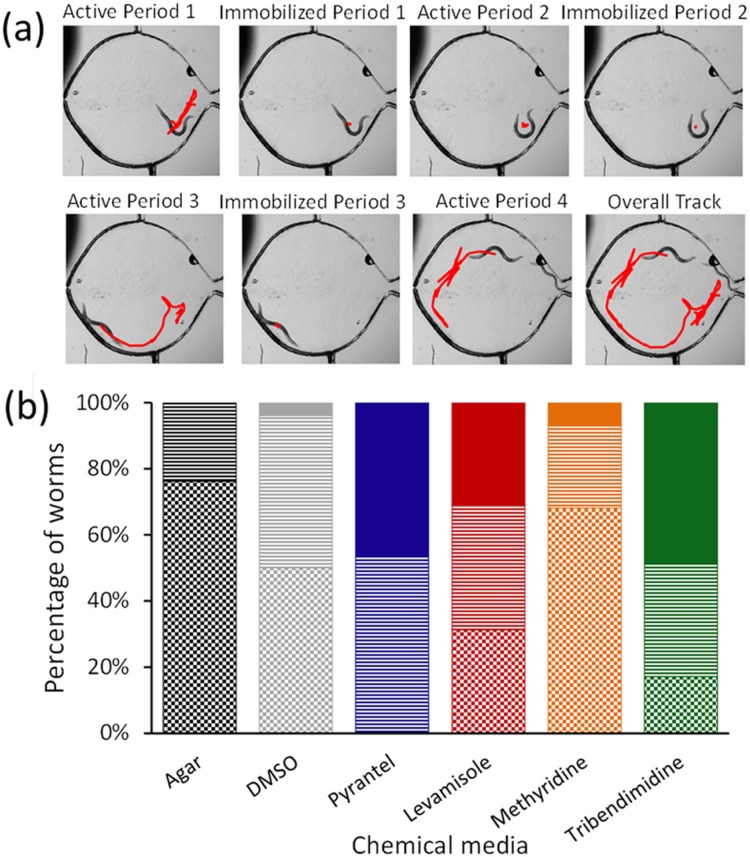

Fig. 5a illustrates the immobilization patterns for a sample worm in the microfluidic device. We used a custom worm tracking program to locate the body centroid of individual worms in the drug well over the length of the video.25 Tracks of a sample worm are plotted to show three cycles periods of being active and temporarily immobilized. During each active period, the worm moves freely and its track appears linear; while in each temporarily immobilized period, a part of the worm's body shows spasm-like events and its track appears to be zigzag without much displacement. Eventually, the worm may enter a permanently immobilized period where it becomes completely motionless for over 600 s.

Figure 5.

Immobilization patterns leading to paralysis. (a) Snapshots of a representative worm undergoing periods of being active and temporarily immobilized. A custom worm tracking program25 is used to mark the x-y co-ordinates of the worm's body centroid as a function of time (shown in red). (b) The plot shows the percentage of worms that are active (shaded as checkerboard), temporarily immobilized (shaded as horizontal lines), or permanently immobilized (shaded as solid) at the end of 40 min of drug exposure.

Fig. 5b plots the percentage of worms that were active, temporarily immobilized, or permanently immobilized at the end of their 40 min drug exposure. In control conditions, a negligible fraction of worms is permanently immobilized. Compared to other drugs, a higher percentage of worms (68%) remain active in methyridine. In pyrantel, none of the worms are active and the population is either temporarily (53.33%) or permanently immobilized (46.66%). The percentages of permanently immobilized worms are comparatively higher in pyrantel and tribendimidine (48.57%) than in other chemical media.

Active and immobilization periods: Count and time duration

Thus far, we characterized an actively moving worm by transitions between crawling, curling, and flailing. We saw that prolonged drug exposure can cause an active worm to enter temporary or permanent immobilization, which was measured at the end of the 40-min experiment. To add further insights to the time-dependent progression of drug activity, we explored how often and how long an active worm enters periods of immobilization before completely succumbing to the drug.

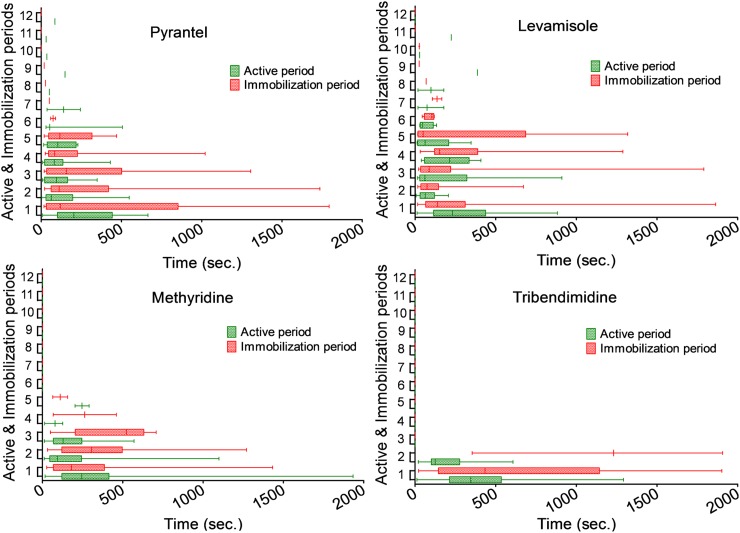

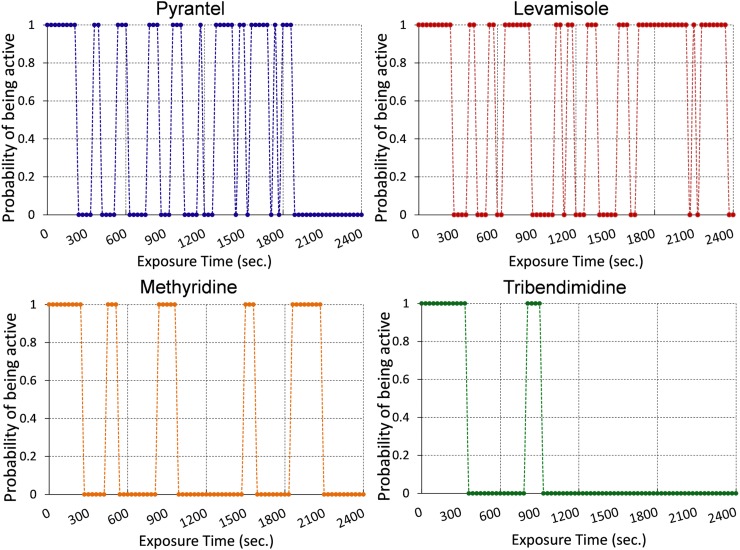

The time duration a worm spends in each active or immobilization period also varies in the four drug environments. In Fig. 6, we plot the time spent by worms in the individual active and immobilization period, respectively. A permanently immobilized worm is ignored for subsequent analyses. In Fig. 7, we plot the probability for a worm being active. Active worms are assigned a probability of 1, and immobile worms have a probability of 0. The median of time durations during each active or immobilization period (from Fig. 6) is estimated and used to plot this figure. In general, the time spent in each active period (shown as green bars, Fig. 6) decreases with increasing exposure time. On the other hand, the time spent in each immobilization period (shown as red bars, Fig. 6) increases with increasing exposure time (except for pyrantel). In other words, an active worm starts pausing for longer time durations (with shorter periods of being active) upon increasing exposure to the drug. In tribendimidine, the time spent in the first two immobilization periods is significantly higher than in other drugs (p < 0.0001). In some worms, the effect of levamisole exposure is even reversible suggesting that this drug may be the least potent amongst the four anthelmintics. All worms remained active in 0.8% agarose and never entered the second immobilization period.

Figure 6.

The figure shows the time duration worms spend in each active and immobilization periods until they are permanently immobilized. Each pair of active and immobilization periods is numbered sequentially in the y-axis.

Figure 7.

The figure shows the probability of a worm being active during the length of drug exposure. The median of time durations for active and immobilized periods are calculated from Figure 6. The probability of a worm being active is denoted as 1 while that of being immobilized is denoted as 0.

DISCUSSION

Some modifications were made in our device design and methodology to simplify the earlier experimental method25 and optimize it for observing events leading to worm paralysis. It was seen that electric field was needed only initially to coax the worms into the drug well. When sufficient number of worms entered the drug well, the electric field was switched off (typically after the first 5–7 min). At the optimal range of electric fields (∼5 V/cm), we did not observe any behavioral changes in the presence of electric fields.25 In addition, the device dimensions were altered to minimize the chances of a worm leaving the drug well in absence of electric fields. For this, the tapered mouth was made narrower and only one side port was included. The two-step agarose filling process (Fig. 1) was also better controlled with a narrower mouth and allowed us to control the time instance when worms enter the drug well. The length of the microchannel was shortened, so the wait time for worm entry into the drug well is reduced. Shrinking the lateral dimensions of every device allowed us to fit up to four devices within the microscope's field of view for parallel runs. Furthermore, in contrast to quantifying drug effects by the sensitivity of electric fields at pre- and post-exposure time instances,25 we extracted parameters related to movement, immobilization, and body shapes through the period of drug exposure and attempted to show differences across four drugs.

In equipotent concentrations of both pyrantel and levamisole, the worms exhibited similar movement phenotypes. We observed that an active worm moves in a sinusoidal manner with periods of immobilization where it curls its body and eventually paralyzes. In both chemical environments, a worm undergoes at least five to six active and immobilization periods (Figs. 67). The average time spent in each active period is similar in both cases and markedly distinct compared to those in methyridine and tribendimidine (Fig. 6). The inherent similarities between movement phenotypes in pyrantel and levamisole do suggest that these drugs act on the same subtype of nAChR receptors (i.e., L-subtype).7, 8, 9, 11, 34 However, there are some differences between pyrantel and levamisole. The average time spent in each immobilization period is longer in pyrantel than in levamisole (Fig. 6). In other words, an active worm in pyrantel prefers to rest longer, curl up, or move less often; whereas an active worm in levamisole spends similar time durations being active or resting/curling. This is also reflected in Fig. 5 where, at the end of an experiment, no worms in pyrantel appear active and are either temporarily or permanently immobilized; whereas around 30% worms are still active in levamisole. These differences suggest that pyrantel may be more effective than levamisole, even being at the same potency concentrations.7

A comparison between tribendimidine and the other two L-subtype nAChR agonists, levamisole and pyrantel, is worth discussing here. It has been shown that tribendimidine affects C. elegans using a similar pathway as levamisole and hence belong to the same class of L-subtype nAChR agonists.6 Since these three drugs have similar mechanisms of action, should we expect differences in the patterns of paralysis? In general, movement phenotypes in tribendimidine are same as those in pyrantel and levamisole. One key difference is noted in the number of active periods and duration of immobilization. In tribendimidine, the number of active periods is reduced and the time duration of immobilization periods is much increased compared to those in levamisole or pyrantel (Fig. 6). This may indicate that tribendimidine is more effective at a single dose than levamisole or pyrantel. Evidence of tribendimidine's superior performance compared to the other two L-type nAChR agonists (i.e., levamisole and pyrantel) at single-dose levels has also been suggested in recent studies performed on treating Ascaris or hookworms.35, 36 In addition, the increased number of active periods in levamisole may indicate that worms could recover from drug exposure, if given at concentrations below 10 μm with recovery time over 2 h (data not shown). Hence, we feel that our derived parameters (such as number of active periods and time durations of immobilization) could help compare the effectiveness of a single or a cocktail of multiple anthelmintics for single dose therapies where irreversible paralysis is desired. Of course, this characterization method would serve as a preliminary test to supplement standard in vivo experiments.12

In methyridine, we noticed a distinct departure from the movement phenotype associated with levamisole, pyrantel, and tribendimidine. In this drug, worms exhibited a swimming-like motion where the body formed half waves during moving. Occasionally, the worms would thrash about a fixed location (that we defined as flailing) and then continue their swimming-like motion. Swimming motion is typically seen in C. elegans when the surrounding medium is liquid. It was interesting to observe this swimming-like behavior in the presence of methyridine where the surrounding medium was 0.8% agarose gel. Considering that methyridine acts on the same nAChR receptor, our observed difference in movement could suggest that this drug acts on a different subtype of nAChR receptor. This assumption is in line with previous studies showing that methyridine target N-subtype nAChR receptors and not the L-subtype nAChR receptors.11

In our view, this microfluidic-enabled characterization method will broaden the scope of data extraction from drug screening experiments, improve our understanding of worm resistance and adaptability in adverse chemical environments, and provide faster ways of predicting new and existing drug targets prior to detailed electrophysiological experiments. To the best of our knowledge, such a detailed characterization of worm paralysis upon exposure to anthelmintics has not been conducted before. While we investigated behavioral changes in wild-type C. elegans leading to paralysis, further tests with relevant mutants and parasites could help establish relationships between molecular mechanisms of drug action and the observed phenotypes.1, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 In this regard, C. elegans and other model organisms are gaining increased attention for the rapid screening of large sets of small molecules (e.g., membrane-permeable inhibitors of protein function) that induce phenotypic changes in the worm, such as lethality, unco-ordinated movement, slow growth and development, and morphological defects.42 It is expected that the process of discovering novel drugs would rely on large-scale behavioral screening of worms, measurement of multiple parameters with sufficient resolution, standardization of observed phenotypes across disparate platforms, and linkage between the chemical and behavioral libraries.43, 44

Interested readers, who wish to use and test our devices on other chemicals or mutants, are welcome to directly email the corresponding author (S.P.). We can provide the fabricated microfluidic devices and tracking software, and discuss the steps for setting up experiments. The device dimensions can be further altered and customized for other parasitic nematodes. A standard desktop computer compatible with Microsoft Windows 7, a large-capacity hard drive, and a microscope with attached camera will be required.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we presented a method to characterize the behavioral events of C. elegans over an extended time period: from exposure to the drug to their eventual paralysis. We found that a single parameter was unable to capture the overall drug effects through the experimental period. So, multiple parameters were calculated, such as curls per second, types of paralyzation, mode frequency, and number/duration of active/immobilization periods. We found that pyrantel is more effective than levamisole in immobilizing the worms at the end of the 40-min experiments. In tribendimidine, worms display shorter number of active periods before permanently immobilizing than in pyrantel or levamisole. In methyridine, worms exhibit a swimming-like movement that is different from the normal crawling movement in pyrantel, levamisole, and tribendimidine. Our results may suggest the following: methyridine acts on a different subtype of nAChR receptors than the other three anthelmintics, the action of pyrantel and levamisole is similar but pyrantel is more effective than levamisole, and tribendimidine is more potent than pyrantel or levamisole in causing an irreversible paralysis of the worms. This multi-parameter extraction method expands the repertoire of phenotypic characterization tools available in existing drug-based microfluidic devices. In addition, the method could complement rigorous electrophysiological experiments to rapidly test screen compounds against nematodes, establish suitable drug candidates, and predict the class of target receptor subtypes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Jo Anne Powell-Coffman for providing C. elegans culture plates, and Alan P. Robertson and Richard Martin for providing the anthelmintics. In addition, we are thankful to Richard Martin for providing valuable insights on the experimental results. This work was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF CMMI-1000808; CBET-1150867) and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NNX12AO60G).

References

- Connell D. O., Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 568–569 (2006). 10.1038/nrmicro1469 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gasbarre L. C., Smith L. L., Hoberg E., and Pilitt P. A., Vet. Parasitol. 166, 275–280 (2009). 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasbarre L. C., Smith L. L., Lichtenfels J. R., and Pilitt P. A., Vet. Parasitol. 166, 281–285 (2009). 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminsky R., Ducray P., Jung M., Clover R., Rufener L., Bouvier J., Weber S. S., Wenger A., Wieland-Berghausen S., Goebel T., Gauvry N., Pautrat F., Skripsky T., Froelich O., Komoin-Oka C., Westlund B., Sluder A., and Maeser P., Nature 452, 176–U119 (2008). 10.1038/nature06722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate R. G. and Besier R. B., Anim. Reprod. Sci. 50, 440–443 (2010). 10.1071/AN10022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Xiao S.-H., and Aroian R. V., PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 3, e499 (2009). 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R. J. and Robertson A. P., Parasitology 134, 1093–1104 (2007). 10.1017/S0031182007000029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H., Martin R. J., and Robertson A. P., Faseb J. 20, 2606 (2006). 10.1096/fj.06-6264fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H., Robertson A. P., Powell-Coffman J. A., and Martin R. J., Faseb J. 22, 3247 (2008). 10.1096/fj.08-110502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leignel V., Silvestre A., Humbert J. F., and Cabaret J., Vet. Parasitol. 172, 80–88 (2010). 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R. J., Bai G. X., Clark C. L., and Robertson A. P., Brit. J. Pharmacol. 140, 1068–1076 (2003). 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Platzer E. G., Bellier A., and Aroian R. V., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 5955–5960 (2010). 10.1073/pnas.0912327107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beugnet F., Kerboeuf D., Nicolle J. C., and Soubieux D., Vet. Parasitol. 63, 83–94 (1996). 10.1016/0304-4017(95)00879-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaletta T. and Hengartner M. O., Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 5, 387–398 (2006). 10.1038/nrd2031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchison W. D., Geary T. G., Manning B., VandeWaa E. A., and Thompson D. P., Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 112, 133–143 (1992). 10.1016/0041-008X(92)90289-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaba S., Cabaret J., Sauve C., Cortet J., and Silvestre A., Vet. Parasitol. 171, 254–262 (2010). 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.03.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørn H., Roepstorff A., Waller P. J., and Nansen P., Vet. Parasitol. 37, 21–30 (1990). 10.1016/0304-4017(90)90022-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson A. P., Bjorn H. E., and Martin R. J., Faseb J. 13, 749–760 (1999); available at http://www.fasebj.org/content/13/6/749.long. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond J. E. and Jorgensen E. M., Nat. Neurosci. 2, 791–797 (1999). 10.1038/12160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Lancheros E., Viau C., Walter T. N., Francis A., and Geary T. G., Int. J. Parasitol. 41, 455–461 (2011). 10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpkin K. G. and Coles G. C., J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 31, 66–69 (1981). 10.1002/jctb.280310110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boina D. R., Lewis E. E., and Bloomquist J. R., Pest Manage. Sci. 64, 646–653 (2008). 10.1002/ps.1591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCavera S., Walsh T. K., and Wolstenholme A. J., Parasitology 134, 1111–1121 (2007). 10.1017/S0031182007000042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinnock R. D., Sattelle D. B., Gration K. A., and Harrow I. D., Neuropharmacology 27, 843–848 (1988). 10.1016/0028-3908(88)90101-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr J. A., Parashar A., Gibson R., Robertson A. P., Martin R. J., and Pandey S., Lab Chip 11, 2385–2396 (2011). 10.1039/c1lc20170k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Deutmeyer A., Carr J., Robertson A. P., Martin R. J., and Pandey S., Parasitology 138, 80–88 (2011). 10.1017/S0031182010001010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldanha J. N., Parashar A., Pandey S., and Powell-Coffman J. A., Toxicol. Sci. 135, 156–168 (2013). 10.1093/toxsci/kft138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K., Crane M. M., and Lu H., Nat. Methods 5, 637–643 (2008). 10.1038/nmeth.1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirman J. N., Crane M. M., Husson S. J., Wabnig S., Schultheis C., Gottschalk A., and Lu H., Nat. Methods 8, 153–U178 (2011). 10.1038/nmeth.1555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W., Wen H., Lu Y., Shi Y., Lin B., and Qin J., Lab Chip 10, 2855–2863 (2010). 10.1039/c0lc00256a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W., Qin J., Ye N., and Lin B., Lab Chip 8, 1432–1435 (2008). 10.1039/b808753a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettinger J. C. and McIntire S. L., Genes Brain Behav. 3, 266–272 (2004). 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00080.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parashar A., Lycke R., Carr J. A., and Pandey S., Biomicrofluidics 5, 024112–024119 (2011). 10.1063/1.3604391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R. J., Clark C. L., Trailovic S. M., and Robertson A. P., Int. J. Parasitol. 34, 1083–1090 (2004). 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S. H., Hui-Ming W., Tanner M., Utzinger J., and Chong W., Acta Trop. 94, 1–14 (2005). 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann P., Zhou X.-N., Du Z.-W., Jiang J.-Y., Xiao S.-H., Wu Z.-X., Zhou H., and Utzinger J., PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2, e322 (2008). 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulin T., Gielen M., Richmond J. E., Williams D. C., Paoletti P., and Bessereau J.-L., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 18590–18595 (2008). 10.1073/pnas.0806933105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L. A., Jones A. K., Buckingham S. D., Mee C. J., and Sattelle D. B., Int. J. Parasitol. 36, 617–624 (2006). 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culetto E., Baylis H. A., Richmond J. E., Jones A. K., Fleming J. T., Squire M. D., Lewis J. A., and Sattelle D. B., J. Biol. Chem. 279, 42476–42483 (2004). 10.1074/jbc.M404370200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James C. E. and Davey M. W., Int. J. Parasitol. 39, 213–220 (2009). 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaewintajuk K., Cho P. Y., Kim S. Y., Lee E. S., Lee H. K., Choi E. B., and Park H., Parasitol. Res. 107, 27–30 (2010). 10.1007/s00436-010-1828-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok T. C. Y., Ricker N., Fraser R., Chan A. W., Burns A., Stanley E. F., McCourt P., Cutler S. R., and Roy P. J., Nature 441, 91–95 (2006). 10.1038/nature04657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokel D., Bryan J., Laggner C., White R., Cheung C. Y., Mateus R., Healey D., Kim S., Werdich A. A., Haggarty S. J., Macrae C. A., Shoichet B., and Peterson R. T., Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 231–237 (2010). 10.1038/nchembio.307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh R., Mohammadi A., Kruglyak L., and Ryu W. S., BMC Biol. 10, 85 (2012). 10.1186/1741-7007-10-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]