Abstract

Prostate Cancer (PCa) is the second leading cause of cancer death in men. Current research findings suggest that the androgen receptor (AR) and its signaling pathway contribute significantly to the progression of metastatic PCa. The AR is a ligand activated transcription factor, where androgens such as testosterone (T) and dihydroxytestosterone (DHT) act as the activating ligands. However in many metastatic PCa, the AR functions promiscuously and is constitutively active through multiple mechanisms. Inhibition of enzymes that take part in androgen synthesis or synthesizing antiandrogens that can inhibit the AR are two popular methods of impeding the androgen receptor signaling axis; however, the inhibition of androgen-independent activated AR function has not yet been fully exploited. This article focuses on the development of emerging novel agents that act at different steps along the androgen-AR signaling pathway to help improve the poor prognosis of PCa patients.

Keywords: Prostate Cancer, Androgen Receptor, Targeted Therapy, Natural Agents

Introduction

For the men of the United States, prostate cancer (PCa) is not only one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers, but also one of the most predominant causes of death in relation to cancer (Siegel et al, 2013). The reason for its prominence is the lack of clear understanding of the cancer and how it is spread. Nonetheless, much research and progress has recently been made in the path toward understanding the mechanisms behind the metastasis of PCa. This has allowed for the development of novel therapies with more definitive targets.

Androgen deprivation therapy is one of the most widely used and understood therapy options for PCa. This therapy is generally accepted to cause a reduction in the amount of prostate specific antigen (PSA), which consequently induces a notable decrease in the circulating tumor cell (CTC) count (Attard et al, 2011; Ferraldeschi et al, 2013). Such declines can be incurred by a variety of different drugs, such as MDV3100 or abiraterone acetate, and they are associated with cancer regression (Attard et al, 2011). These two drugs, as well as others that instigate a similar effect, are known to function by either directly or indirectly inhibiting the androgen receptor (Massard and Fizazi, 2011). Emerging studies have demonstrated that androgen receptor (AR) signaling plays a large role in the development and progression of PCa, even after castration (Sharma et al, 2013; Snoek et al, 2009). Thus, regulation of the receptor and its signaling pathway has become a major point of interest in PCa research.

This article reviews current treatment methods for PCa in addition to promising new methods. Furthermore, current understanding of AR signaling as well as its implications on novel treatments for PCa is examined as summarized in the following sections.

Prostate Cancer & Current Treatment Methods

A variety of different signaling pathways, such as hormonal, autocrine, and paracrine pathways, as well as various transcription factors, are involved in the development of the prostate gland (Prins and Putz, 2008). These pathways are associated with various androgens, including testosterone (T) and dihydroxytestosterone (DHT), which are also necessary for prostate development. As mentioned above, the increased levels of androgens and androgen-driven signaling in males in part contribute to the development of PCa. Thus, treatment methods have been associated with attempting to decrease the amount of circulating androgens and androgen-driven signaling through the activation of the androgen receptor (AR). The most popular method is either surgical castration, which involves removal of the testicles, or chemical castration, which is the systemic delivery of anti-androgens commonly known as Androgen Deprivation Therapy or in short ADT (Massard and Fizazi, 2011). However, both types of castration have proved to be only temporary treatment options because patients frequently develop resistance to these treatments with eventual increased amount of androgens, PSA, and increased CTCs, leading to the development of progressive and metastatic disease. At this point, the disease has progressed to its more detrimental form, commonly called castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). Due to relapse of the cancer, castration has become more of an initial treatment method, but unfortunately is not a permanent solution to cure PCa. Radiation and chemotherapy are also repeatedly used to treat PCa, yet it has been found that these therapies are also more effective in conjunction with other treatment options. One such option is the use of AR targeted drugs (AR antagonists) or hormone therapies (Mostaghel et al, 2009). This option is further discussed in detail in the next section of the article; however, it is currently being recognized that inactivation of androgen production or its binding to AR is not going to be entirely useful for curing PCa patients, and thus attempts are being made to inactivate the AR directly which has likely become the most useful strategy for improving the survival of patients diagnosed with PCa (Sampson et al, 2013; Desiniotis et al, 2010).

Another recently explored option has involved the targeting of AR splice variants by novel agents, as well as siRNA silencing of the full-length androgen receptor (AR-FL) in order to downplay the effects of the splice variants (Hu et al, 2012; Watson et al, 2010). Androgen receptor splice variants (ARVs) are constitutively active forms of the AR that lack the C-terminal ligand-binding domain (Hu et al, 2012; Watson et al, 2010; Dehm et al, 2008). The lack of the ligand-binding domain is instrumental in the resistance to different therapies as it is necessary for hormone binding (Dehm et al, 2008). Although the ligand-binding domain (LBD) has been removed, the N-terminal domain that is necessary for DNA binding and transactivation is preserved among ARVs (Watson et al, 2010; Roychowdhury and Chinnaiyan, 2013). As a result, CRPC patients generally have an up-regulated amount of ARVs that are still able to function in a negative manner, correlating with a more aggressive cancer phenotype. Interestingly enough, the up-regulated amount of ARVs has been shown to correspond with an increased amount of AR-FL, suggesting that a molecular connection between the two may exist. One study illustrated that the negative tumor stimulating effects of ARVs are mediated through AR-FLs, thus by silencing the expression of AR-FLs by siRNAs, the transcription of ARVs would halt as well (Watson et al, 2010); however, this field could use further mechanistic studies. AR targeted drugs such as MDV3100 and abiraterone acetate have been shown to play a positive role in reversing the malignant effects of PCa; however, such drugs seem to play a minor role in PCa cell lines with high expression of ARVs and AR-FLs that have developed resistance to these rather new drugs (Li et al, 2013; Shafi et al, 2013). Thus, additional research should continue towards understanding the signaling mechanism of ARVs to uncover different methods that will enable their knockdown, possibly aiding in the reversal of the poor prognosis of PCa (Peacock et al, 2012).

Androgen Receptor Signaling in Prostate Cancer

It is important to identify various biomarkers of PCa, especially aggressive PCa with high metastatic potential, in order to fully elucidate the molecular mechanisms of the different stages of PCa progression. One such molecular biomarker widely used to screen for PCa is the concentration of serum PSA present (Roychowdhury and Chinnaiyan, 2013). PSA is important in the diagnosis of PCa because high serum PSA levels have been demonstrated to correlate with a poor prognosis while low serum PSA levels generally correlate with more positive outcomes. Because of the effectiveness of PSA as a diagnostic tool, researchers have advocated for the use of outcomes based on PSA measurements when reporting results for different PCa treatment studies (Grimm et al, 2012). Uniformity in the manner of measuring the effectiveness of different treatments when reporting results will allow for a more accurate comparison and analysis of data from different studies. In turn, more appropriate measures can be taken to discover PCa treatments.

While PSA is important in deducing the stages of PCa, the mechanisms by which the AR is able to evolve the cancer into CRPC is also significant. In theory, androgen-deprivation therapy should be effective enough to halt the AR signaling pathway. This failure to do so has led to intense study of the AR and the different manners in which it is being led to sustain tumor growth even after castration. Specific studies of mouse models with CRPC have been shown to decrease tumor growth as well as increase cell apoptosis due to treatment with different drugs that inhibit AR and its signaling pathway (Guerrero et al, 2013; Thompson et al, 2012). Overexpression or mutations of the AR are two of the main methods that have been suggested to lead to CRPC (Edwards et al, 2003; Taplin et al, 2003). Mutations are hazardous because they allow for the possibility of other ligands and steroid hormones to activate the AR pathway without androgens (Ferraldeschi et al, 2013; Taplin et al, 2003). Certain loss of function studies have demonstrated that some point mutations allow for a constitutively active AR, and thus greatly increased chances in PCa development (Hay and McEwan, 2012). Even more threatening are growth factor signaling pathways that activate the AR without any ligand at all, presenting a challenging situation to overcome treatment failure (Montgomery et al, 2008). In addition to overexpression of the AR in CRPC, increasing amounts of the enzymes that take part in synthesizing androgens also contribute to exacerbating the problem (Montgomery et al, 2008). Due to a variety of methods by which CRPC can develop, there are many different approaches that will make the use of AR targeted drugs more effective in inhibiting the AR signaling pathway, either directly or indirectly. Biomarkers such as the serum concentration of circulating PSA or androgens can be useful to these approaches which may indicate different stages of PCa.

Androgen Receptor Targeted Drugs in Prostate Cancer

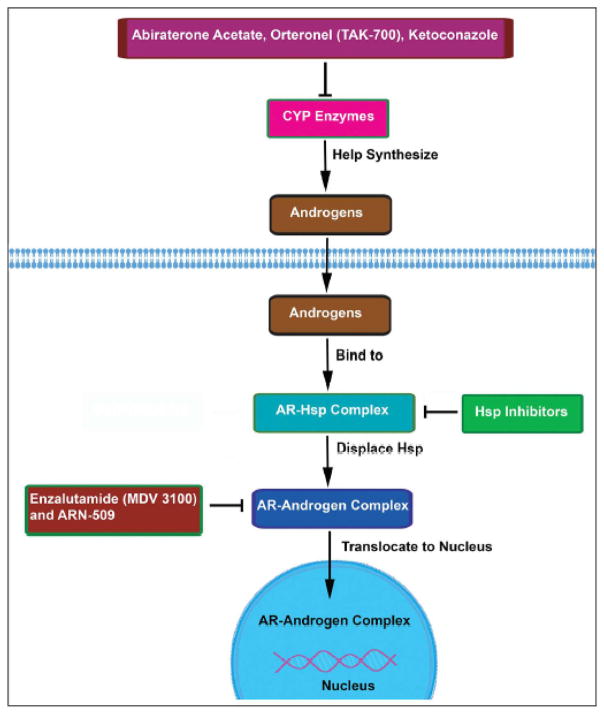

The importance of the AR and its up-regulation in progressively worse stages of PCa has called for the development of novel agents that will disrupt the AR signaling pathway. Essentially, new treatments involving AR targeted drugs have focused on inhibiting the androgen-receptor complex in order to prevent the AR from acting as a transcription factor. Binding of the drug to the receptor can induce a conformational change that can prevent nuclear translocation and transcription (Dumas et al, 2012). As explained above, evidence that the drug is having the desired effect can be noted by a decrease in the amount of PSA. The following are a brief discussion on a few of the most popular upcoming AR antagonists and their signaling pathway as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of Androgen receptor (AR) targeted drugs and their signaling pathways involved in the development and progression of prostate cancer.

Directly Targeting the AR

Enzalutamide (MDV3100)

Enzalutamide, more commonly known as MDV3100, is one of the most frequently studied AR antagonists. Although it is a drug that is administered orally, the effects of enzalutamide are still widespread because it targets several steps in the AR-signaling pathway (Scher et al, 2012; Golshayan and Antonarakis, 2013). Due to its increased binding affinity for the AR, it is able to block androgens from binding to the receptor. Consequently, this prevents nuclear translocation of the AR, DNA binding, and co-activator recruitment of the ligand-receptor complex (Scher et al, 2010; Scher et al, 2012). An additional benefit in the use of MDV3100 is that it has no known agonist activities, thus it is not able to continue the androgen production pathway and can be deemed an “antiandrogen” (Scher et al, 2010; Dumas et al, 2012). Furthermore, in certain mice cell lines that develop tumors, treatment with MDV3100 showed regression of the tumor, as opposed to other drugs that only slowed tumor growth (Tran et al, 2009). One of the more notable characteristics of MDV3100 is that it is able to bind and inhibit not only wild type, but also mutant AR, more effectively than other drugs as discussed below (Richards et al, 2012). Mutant AR refers to point mutations of the AR that commonly occur after the progression of PCa which causes castration resistance.

Clinical trials have also been done with MDV3100. These studies have provided valuable information for the potential use of MDV3100 as a commercial AR targeted drug. One specific study displayed that approximately fifty percent of patients demonstrated a positive response to the drug, exhibiting a drop in PSA levels as well as disease stability (Dumas et al, 2012). The most notable side effect was patient fatigue when higher doses of the drug were administered (Dumas et al, 2012). Additionally, the first phase 3 trial with MDV3100 was conducted with 1,200 metastatic CRPC men with previous docetaxel treatment (Menon and Higano, 2013). The trial displayed low toxicity and again, the most prominent adverse effect was fatigue. However, risk of seizures due to MDV3100 treatment was brought to light and is currently under further review. Collectively, this first phase 3 trial portrayed significantly prolonged overall survival rates in comparison to the men who received the placebo treatment (Menon and Higano, 2013). Hence, MDV3100 can be seen as a safe and well-tolerated drug among the majority of patients treated (Dumas et al, 2012).

ARN-509

After the favorable effects of enzalutamide were presented, there was an increase in the discovery of similar novel agents that would competitively inhibit the AR. ARN-509 is one such agent and has been shown to actually be a more effective and potent antiandrogen than enzalutamide. Not only has it demonstrated longer lasting tumor remissions in mice models, but in general has displayed greater tumor suppressing characteristics than enzalutamide (Kim and Ryan, 2012). As a pure antagonist of the AR, binding of ARN-509 to the AR inhibits nuclear translocation of the AR, the transcription of genes mediated by androgens, and DNA binding (Leibowitz-Amit and Joshua, 2012; Schweizer and Antonarakis, 2012). Such effects are beneficial for the treatment of PCa and especially of CRPC.

Due to its potency, reduced concentrations of ARN-509, as compared to enzalutamide, would be sufficient to achieve the same results. Thus, lower treatment dose in patients is generally perceived as more advantageous due to a lesser chance of possible side effects (Clegg et al, 2012). Phase I trials testing safety, PSA levels, and other outcomes with ARN-509 have been completed and it has now been moved into Phase II testing (Schweizer and Antonarakis, 2012; Clegg et al, 2012). The phase I study exhibited similar toxicity results as MDV3100, with fatigue being the most common side effect (Menon and Higano, 2013). However, unlike enzalutamide, no reports of seizures have been noted to date, further suggesting its increased efficiency in relation to MDV3100 (Menon and Higano, 2013). The results of ARN-509 testing thus far have been promising and it should be at the top of the list as an innovative next generation AR targeting drug.

Bicalutamide

An additional factor that is important to consider when synthesizing AR-targeted drugs is whether or not they are steroids. Non-steroidal antiandrogens have been used regularly in advanced PCa treatment due to their behavior as “pure” AR antagonists (Attard et al, 2011). Steroids have a broader target range in the body, thus implementing the use of non-steroidal agents like bicalutamide can improve the drugs target accuracy and decrease undesirable side effects (Chen et al, 2009). Bicalutamide acts by binding to an allosteric site on the AR, inducing a conformational change in the co-activator binding site, and consequently inhibiting transcriptional activity of AR (Osguthorpe and Hagler, 2011). Decreased expression of the AR upon treatment with bicalutamide occurs as a result; however, it has been discovered that this results in only temporary action. Further studies with bicalutamide have demonstrated that it later loses its antagonistic activity and unfortunately develops agonistic characteristics in castration-resistant tumor cells (Osguthorpe and Hagler, 2011). One reason suggested for the agonistic action of bicalutamide is that by associating with transcription factors like FoxA1, the AR inhibitory effect is diminished (Heidegger et al, 2013). This is due to the fact that binding of bicalutamide to FoxA1 can reorganize chromatin, making chromatin more susceptible for AR binding, which in turn triggers the AR signaling pathway (Sahu et al, 2011). Efforts to deduce the structure of the agonist-receptor complex have been launched in order to understand how to prevent the conformational change that causes bicalutamide to develop agonistic activity (Osguthorpe and Hagler, 2011). It is these efforts and more that will continue to expand the benefits of prostate cancer research and its relation to AR-targeted drugs.

Indirectly Targeting the AR

Ketoconazole

Ketoconazole is another inhibitor of enzymes in the cytochrome P450 pathway; however, it is no longer as commonly used as before especially because of the development of Abiraterone which is a synthetic analog of ketoconazole. Moreover, studies have demonstrated that the other CYP inhibitors such as the two mentioned below are more effective than ketoconazole for a variety of reasons. First and foremost, ketoconazole is not as specific of an inhibitor, thus its wider target range gives it the opportunity to interact with other drugs, therefore decreasing the efficacy of both of the drugs (Zhu and Garcia, 2013). There are also wide ranges of side effects that are associated with ketoconazole use, such as adrenal insufficiency and toxic effects on the liver and GI system (Zhu and Garcia, 2013). Yet despite such negative consequences, treatment with ketoconazole still demonstrated decreased PSA levels at higher doses and inhibited key CYP enzymes (Small et al, 1997).

Abiraterone Acetate

Another emerging agent in the treatment of CRPC is abiraterone acetate. While MDV3100 targets the AR directly, abiraterone acts by indirectly inhibiting the AR signaling pathway. CYP17, an enzyme of the cytochrome P450 family, is inhibited by abiraterone (Stein et al, 2012). This inhibition is significant because CYP17 plays a critical role in testosterone synthesis. Accordingly, inhibition of CYP17 would cause inhibition of testosterone synthesis, limiting the amount of androgens circulating in the body, thus also limiting the action of the AR. While castration is able to decrease testosterone and DHT synthesis, it does not remove all possible sources of androgens within the body, such as intratumoral or adrenal androgens. This explains why other mechanisms of androgen inhibition, such as that seen with abiraterone, are important aspects to consider when determining how to inhibit the overall AR signaling axis to cure CRPC. However, while levels of circulating androgens decrease upon treatment with abiraterone, inhibition of CYP enzymes also indirectly causes a rise in the level of corticosteroids (Sartor et al, 2011). This rise is generally associated with the toxicity of abiraterone and can therefore be classified as dangerous. The effects of elevated corticosteroid levels can also be observed by fluid retention and edema, hypokalemia, and hypertension (Turitto et al, 2012). Moreover, this drug may not be effective in tumors having different splice variants.

A significant decline in PSA levels was observed in over 50% of patients in phase-I studies with abiraterone, implying that it can be a useful therapeutic option (Stein et al, 2012). Although PSA is one method in which the progression of CRPC can be measured, bone metastasis is also a viable measuring tactic. One of the chief causes of morbidity in metastatic CRPC is bone metastasis, which can be deregulated by abiraterone acetate (Taneja, 2013). Thus, some researchers have chosen to measure the effectiveness of abiraterone acetate by measuring the prevention of skeletal-related events in patients during treatment (Taneja, 2013). Additionally, abiraterone was seen to setback the need for chemotherapy as well as the progression of pain in CRPC patients (Taneja, 2013; Burki, 2013).

Interesting studies have been conducted with the oral administration of abiraterone in conjunction with the type of food being eaten during treatment. For example, it was found that foods with a higher fat content were able to increase drug exposure by more than 4 times as compared to patients taking the same amount of drug on an empty stomach (Leibowitz-Amit and Joshua, 2012). Such studies are quite valuable as they can provide evidence that could decrease the amount of drug necessary to have a substantial effect on patients’ tumor, thus allowing for fewer side effects in patients.

Orteronel

Orteronel, also known as TAK-700, is also a CYP17 inhibitor. The difference between orteronel and abiraterone is that orteronel is much more selective than abiraterone as it specifically inhibits the enzyme 17, 20-lyase more than 17-hydroxylase (Dayyani et al, 2011;Leibowitz-Amit and Joshua, 2012). This selective inhibition may not have the same effect as abiraterone on mineralocorticoids because with specific inhibition of the lyase enzyme, orteronel may be less likely to suppress cortisol. This would generally cause a rise in adrenocorticotropic hormone and subsequently an excessive increase in mineralocorticoids (Dayyani et al, 2011). Decreased or normal amounts of mineralocorticoids can be seen to have a more beneficial effect on CRPC by orteronel, possibly making it a safer treatment option than other CYP17 inhibitors. Upon a phase II evaluation of CRPC patients tested with orteronel, patients displayed lower levels of circulating androgens and tumor cells in addition to decreased amounts of PSA (Zhu and Garcia, 2013).

One study demonstrated that cortisol levels did indeed significantly decrease in both humans and monkeys treated with orteronel. Thus the same negative effects as mentioned above, such as edema and hypertension, are less likely to occur with administration of orteronel (Turitto et al, 2012; Yamaoka et al, 2012). Unfortunately, yet another study conducted with orteronel treated mice displayed that while initially T levels did show a significant decrease, approximately 24 hours after dosing, T levels were almost fully restored (Hara et al, 2013). Further investigations are currently being conducted to define the toxicity and efficacy of orteronel in combination with other PCa therapies (Zhu and Garcia, 2013).

Lupron

An innovative approach to prostate cancer therapy has included the development of luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists. LHRH is released from the hypothalamus and stimulates the anterior pituitary to increase the production of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH). FSH and LH are involved in androgen synthesis; therefore, their up-regulation also increases the amount of circulating androgens, like testosterone and DHT. Consequently, there are more androgens available to interact with the AR and enhance the growth of prostate cancer. Lupron is a LHRH agonist that while initially increases the amount of FSH and LH, eventually causes a prolonged decrease in the release of FSH and LH due to continuous stimulation of the anterior pituitary - thus preventing androgen synthesis (Xu et al, 2012). In addition to castration, the use of Lupron and other LHRH agonists has become one of the most common androgen deprivation (ADT) therapies used in the prevention and treatment of prostate cancer (Choi and Lee, 2011). Despite multiple side effects that have been associated with Lupron treatment, the most prevalent being hot flushes; different approaches involving LHRH are being studied (Choi and Lee, 2011). Additionally, combining other agents, like AR antagonists such as bicalutamide, alongside the administration of Lupron can prevent the harmful side effects of the initial increase in circulating androgen levels (Heidegger et al, 2013).

Targeting Heat Shock Proteins

Emerging research is now being done on heat shock proteins and the role that they play in the AR signaling axis. Extensive research has especially been done on heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90). Hsp90 is a molecular chaperone that regulates the function of a variety of different client proteins, including the AR and other oncogenes (Saporita et al, 2007; He et al, 2013). Client proteins are proteins that function as key regulators of signal amplification in various pathways (He et al, 2013). Focusing on the relationship between the client protein AR and Hsp90, it has come to light that the AR is stabilized by Hsp90 in the cytoplasm. Essentially, the AR associates with Hsp90 in the cytoplasm in a multi-chaperone protein complex that stabilizes the receptor in a conformation that is able to modulate ligand binding (Kim et al, 2012; He et al, 2013). Binding of the ligand would then induce a conformational change allowing the receptor to translocate into the nucleus. However, certain agents have been synthesized that inhibit Hsp90, and after inhibition, it has been found that nuclear localization of the AR is inhibited (Saporita et al, 2007). This is because Hsp90 inhibitors prevent dissociation of the Hsp90-AR complex in the cytoplasm, thus decreasing the amount of AR that is able to translocate into the nucleus (De Leon et al, 2011). In turn, this decreases the transcription of genes that depend on the AR, thus decreasing the expression of the AR and its signaling pathway. Certain studies also found that once the AR was destabilized and at times observed to degrade after dissociation from the heat shock proteins, shortly after, induction of apoptosis of PCa cells was also seen (He et al, 2013). Collectively, the effects that Hsp90 inhibitors have on the AR and other client proteins causes coordinated depression of multiple interacting oncogenic signaling pathways in PCa cells, allowing for a more auspicious patient outcome.

Although destabilization of AR-FL occurred, Hsp90 inhibitors have been observed to have almost no effect on the expression of ARV’s or mutant AR’s (Saporita et al, 2007; He et al, 2013). This is because the mutations and/or deletions of the LBD impair the formation of the Hsp90/AR-complex. However, despite the lack of effect of Hsp90 inhibitors on ARV’s, their effect on decreasing the expression of the AR-FL still manages to suppress tumor growth (He et al, 2013).

Another interesting aspect of PCa treatment that targets heat shock proteins involves methoxychalcones. Studies have found that methoxychalcones are specific types of molecules that have the ability to also prevent the dissociation of the Hsp90-AR-complex, thereby further contributing to the prevention of nuclear translocation of the AR (Kim et al, 2012). However, methoxychalcones are not the only agents that can act as Hsp90 inhibitors, others have also been synthesized. Yet with all of this, we can see that targeting and inhibiting heat shock proteins has proven to hold promising results in relation to targeting the AR. Further phase testing will hopefully show promising clinical success with heat shock protein inhibitors.

Natural Agents

In addition to synthesizing drugs from manufactured chemicals, drugs isolated from natural products have also been found to have a significant effect on PCa. Selenium, soy isoflavones, and green tea are a few examples of natural agents that can reduce the cancers malignancy by inhibiting the AR (Sarkar et al, 2010). Additionally, curcumin and curcumin analogs have demonstrated antagonistic AR abilities (Sarkar et al, 2010; Wang et al, 2012). As a result, CDF (curcumin difluorinated), a drug isolated from curcumin by our group could potentially be useful in PCa therapies (Li et al, 2011; Padhye et al, 2009). While extensive research has been done with CDF in other cancer cells, treatment of PCa cells with CDF requires more studies in order to deduce its potential benefits. Another popular upcoming natural agent being used in PCa research is BR-DIM. BR-DIM is a formulated version of 3,3′-Diindolylmethane (DIM). Its importance lies in the discovery that certain dietary indoles found in cruciferous vegetables can potentially inhibit the growth and tumor characteristics of PCa cells (Ahmad et al, 2009). Previous studies from our laboratory and others have displayed that BR-DIM treatment of advanced PCa cells can cause decreased expression of both the AR and the PCa molecular biomarker PSA (Bhuiyan et al, 2006). As a result, apoptosis is induced while cellular proliferation is prohibited, which may allow favorable patient prognosis. Additionally, we have found that formulated isoflavones and BR-DIM have subdued the bone metastasis associated with PCa by targeting multiple pathways involved in bone remodeling (Li et al, 2012). In general, natural agents are thought to be more effective for cancer treatment as they have shown less harmful side effects than other artificial agents in vivo (Bao et al, 2011). Thus, their use in PCa therapies can be seen as a safer and more effective treatment option, although future studies will judge whether natural agents truly have a place in PCa therapy.

Conclusion

PCa continues to be one of the most prominent cancers in men. To decrease the deadly impact of this cancer, studies on its mechanisms of action must continue intensely. Such studies will contribute to the knowledge database of PCa, allowing for the discovery of more effective treatment options. The AR signaling axis clearly plays a key role in the metastatic progression of PCa, thus identifying various methods by which this signaling pathway could be inhibited will increase the likelihood of better patient prognosis (Chen et al, 2004; Dayyani et al, 2011). Although this article focuses on the action of AR targeted drugs singly, emerging research has demonstrated that utilizing a combination of drugs in therapy is more beneficial (Sasse et al, 2012). The synergistic effect of the drugs when used together is able to aid in the prevention of cancer relapse as well as prolong the favorable effects of each of the drugs used. Thus, as the field of research continues to expand and develop newer insight on the mechanism of PCa progression, the importance of the AR will also continue. Increased understanding will contribute to the development of novel therapies that can provide more positive survival outcomes for PCa patients.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Cancer Institute

Contract grant numbers: 5R01CA108535 and 1R01CA164318

This work was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute, NIH 5R01CA108535 and 1R01CA164318 awarded to FHS. All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: [10.1002/jcp.24456]

Literature Cited

- Ahmad A, Kong D, Sarkar SH, Wang Z, Banerjee S, Sarkar FH. Inactivation of uPA and its receptor uPAR by 3,3′-diindolylmethane (DIM) leads to the inhibition of prostate cancer cell growth and migration. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107:516–527. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attard G, Richards J, de Bono JS. New strategies in metastatic prostate cancer: targeting the androgen receptor signaling pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1649–1657. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao B, Ali S, Kong D, Sarkar SH, Wang Z, Banerjee S, Aboukameel A, Padhye S, Philip PA, Sarkar FH. Anti-tumor activity of a novel compound-CDF is mediated by regulating miR-21, miR-200, and PTEN in pancreatic cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Bhuiyan MM, Li Y, Banerjee S, Ahmed F, Wang Z, Ali S, Sarkar FH. Down-regulation of androgen receptor by 3,3′-diindolylmethane contributes to inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis in both hormone-sensitive LNCaP and insensitive C4-2B prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10064–10072. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burki TK. Abiraterone and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e48. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(12)70585-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, Baek SH, Chen R, Vessella R, Rosenfeld MG, Sawyers CL. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10:33–39. doi: 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Clegg NJ, Scher HI. Anti-androgens and androgen-depleting therapies in prostate cancer: new agents for an established target. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:981–991. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70229-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Lee AK. Efficacy and safety of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists used in the treatment of prostate cancer. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2011;3:107–119. doi: 10.2147/DHPS.S24106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg NJ, Wongvipat J, Joseph JD, Tran C, Ouk S, Dilhas A, Chen Y, Grillot K, Bischoff ED, Cai L, Aparicio A, Dorow S, Arora V, Shao G, Qian J, Zhao H, Yang G, Cao C, Sensintaffar J, Wasielewska T, Herbert MR, Bonnefous C, Darimont B, Scher HI, Smith-Jones P, Klang M, Smith ND, De SE, Wu N, Ouerfelli O, Rix PJ, Heyman RA, Jung ME, Sawyers CL, Hager JH. ARN-509: a novel antiandrogen for prostate cancer treatment. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1494–1503. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayyani F, Gallick GE, Logothetis CJ, Corn PG. Novel therapies for metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1665–1675. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leon JT, Iwai A, Feau C, Garcia Y, Balsiger HA, Storer CL, Suro RM, Garza KM, Lee S, Kim YS, Chen Y, Ning YM, Riggs DL, Fletterick RJ, Guy RK, Trepel JB, Neckers LM, Cox MB. Targeting the regulation of androgen receptor signaling by the heat shock protein 90 cochaperone FKBP52 in prostate cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11878–11883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105160108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehm SM, Schmidt LJ, Heemers HV, Vessella RL, Tindall DJ. Splicing of a novel androgen receptor exon generates a constitutively active androgen receptor that mediates prostate cancer therapy resistance. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5469–5477. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desiniotis A, Schafer G, Klocker H, Eder IE. Enhanced antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects on prostate cancer cells by simultaneously inhibiting androgen receptor and cAMP-dependent protein kinase A. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:775–789. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas L, Payne H, Chowdhury S. The evolution of antiandrogens: MDV3100 comes of age. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12:131–133. doi: 10.1586/era.11.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Krishna NS, Grigor KM, Bartlett JM. Androgen receptor gene amplification and protein expression in hormone refractory prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:552–556. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraldeschi R, Pezaro C, Karavasilis V, de BJ. Abiraterone and novel antiandrogens: overcoming castration resistance in prostate cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2013;64:1–13. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-121211-091605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golshayan AR, Antonarakis ES. Enzalutamide: an evidence-based review of its use in the treatment of prostate cancer. Core Evid. 2013;8:27–35. doi: 10.2147/CE.S34747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm P, Billiet I, Bostwick D, Dicker AP, Frank S, Immerzeel J, Keyes M, Kupelian P, Lee WR, Machtens S, Mayadev J, Moran BJ, Merrick G, Millar J, Roach M, Stock R, Shinohara K, Scholz M, Weber E, Zietman A, Zelefsky M, Wong J, Wentworth S, Vera R, Langley S. Comparative analysis of prostate-specific antigen free survival outcomes for patients with low, intermediate and high risk prostate cancer treatment by radical therapy. Results from the Prostate Cancer Results Study Group. BJU Int. 2012;109(Suppl 1):22–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero J, Alfaro IE, Gomez F, Protter AA, Bernales S. Enzalutamide, an Androgen Receptor Signaling Inhibitor, Induces Tumor Regression in a Mouse Model of Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Prostate. 2013 doi: 10.1002/pros.22674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T, Kouno J, Kaku T, Takeuchi T, Kusaka M, Tasaka A, Yamaoka M. Effect of a novel 17,20-lyase inhibitor, orteronel (TAK-700), on androgen synthesis in male rats. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;134:80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay CW, McEwan IJ. The impact of point mutations in the human androgen receptor: classification of mutations on the basis of transcriptional activity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Zhang C, Shafi AA, Sequeira M, Acquaviva J, Friedland JC, Sang J, Smith DL, Weigel NL, Wada Y, Proia DA. Potent activity of the Hsp90 inhibitor ganetespib in prostate cancer cells irrespective of androgen receptor status or variant receptor expression. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:35–43. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger I, Massoner P, Eder IE, Pircher A, Pichler R, Aigner F, Bektic J, Horninger W, Klocker H. Novel therapeutic approaches for the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu R, Lu C, Mostaghel EA, Yegnasubramanian S, Gurel M, Tannahill C, Edwards J, Isaacs WB, Nelson PS, Bluemn E, Plymate SR, Luo J. Distinct transcriptional programs mediated by the ligand-dependent full-length androgen receptor and its splice variants in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3457–3462. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W, Ryan CJ. Androgen receptor directed therapies in castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2012;13:189–200. doi: 10.1007/s11864-012-0188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YS, Kumar V, Lee S, Iwai A, Neckers L, Malhotra SV, Trepel JB. Methoxychalcone inhibitors of androgen receptor translocation and function. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:2105–2109. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.12.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibowitz-Amit R, Joshua AM. Targeting the androgen receptor in the management of castration-resistant prostate cancer: rationale, progress, and future directions. Curr Oncol. 2012;19:S22–S31. doi: 10.3747/co.19.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Chan SC, Brand LJ, Hwang TH, Silverstein KA, Dehm SM. Androgen receptor splice variants mediate enzalutamide resistance in castration-resistant prostate cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2013;73:483–489. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Kong D, Ahmad A, Bao B, Sarkar FH. Targeting bone remodeling by isoflavone and 3,3′-diindolylmethane in the context of prostate cancer bone metastasis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Kong D, Wang Z, Ahmad A, Bao B, Padhye S, Sarkar FH. Inactivation of AR/TMPRSS2-ERG/Wnt signaling networks attenuates the aggressive behavior of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:1495–1506. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massard C, Fizazi K. Targeting continued androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:3876–3883. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon MP, Higano CS. Enzalutamide, a second generation androgen receptor antagonist: development and clinical applications in prostate cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2013;15:69–75. doi: 10.1007/s11912-013-0293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery RB, Mostaghel EA, Vessella R, Hess DL, Kalhorn TF, Higano CS, True LD, Nelson PS. Maintenance of intratumoral androgens in metastatic prostate cancer: a mechanism for castration-resistant tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4447–4454. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostaghel EA, Montgomery B, Nelson PS. Castration-resistant prostate cancer: targeting androgen metabolic pathways in recurrent disease. Urol Oncol. 2009;27:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osguthorpe DJ, Hagler AT. Mechanism of androgen receptor antagonism by bicalutamide in the treatment of prostate cancer. Biochemistry. 2011;50:4105–4113. doi: 10.1021/bi102059z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padhye S, Yang H, Jamadar A, Cui QC, Chavan D, Dominiak K, McKinney J, Banerjee S, Dou QP, Sarkar FH. New difluoro Knoevenagel condensates of curcumin, their Schiff bases and copper complexes as proteasome inhibitors and apoptosis inducers in cancer cells. Pharm Res. 2009;26:1874–1880. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-9900-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock SO, Fahrenholtz CD, Burnstein KL. Vav3 enhances androgen receptor splice variant activity and is critical for castration-resistant prostate cancer growth and survival. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26:1967–1979. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins GS, Putz O. Molecular signaling pathways that regulate prostate gland development. Differentiation. 2008;76:641–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2008.00277.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J, Lim AC, Hay CW, Taylor AE, Wingate A, Nowakowska K, Pezaro C, Carreira S, Goodall J, Arlt W, McEwan IJ, de Bono JS, Attard G. Interactions of abiraterone, eplerenone, and prednisolone with wild-type and mutant androgen receptor: a rationale for increasing abiraterone exposure or combining with MDV3100. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2176–2182. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roychowdhury S, Chinnaiyan AM. Advancing Precision Medicine for Prostate Cancer Through Genomics. J Clin Oncol. 2013 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu B, Laakso M, Ovaska K, Mirtti T, Lundin J, Rannikko A, Sankila A, Turunen JP, Lundin M, Konsti J, Vesterinen T, Nordling S, Kallioniemi O, Hautaniemi S, Janne OA. Dual role of FoxA1 in androgen receptor binding to chromatin, androgen signalling and prostate cancer. EMBO J. 2011;30:3962–3976. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson N, Neuwirt H, Puhr M, Klocker H, Eder IE. In vitro model systems to study androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20:R49–R64. doi: 10.1530/ERC-12-0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saporita AJ, Ai J, Wang Z. The Hsp90 inhibitor, 17-AAG, prevents the ligand-independent nuclear localization of androgen receptor in refractory prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2007;67:509–520. doi: 10.1002/pros.20541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar FH, Li Y, Wang Z, Kong D. Novel targets for prostate cancer chemoprevention. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:R195–R212. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor O, Michels RM, Massard C, de Bono JS. Novel therapeutic strategies for metastatic prostate cancer in the post-docetaxel setting. Oncologist. 2011;16:1487–1497. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasse AD, Sasse E, Carvalho AM, Macedo LT. Androgenic suppression combined with radiotherapy for the treatment of prostate adenocarcinoma: a systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher HI, Beer TM, Higano CS, Anand A, Taplin ME, Efstathiou E, Rathkopf D, Shelkey J, Yu EY, Alumkal J, Hung D, Hirmand M, Seely L, Morris MJ, Danila DC, Humm J, Larson S, Fleisher M, Sawyers CL. Antitumour activity of MDV3100 in castration-resistant prostate cancer: a phase 1–2 study. Lancet. 2010;375:1437–1446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60172-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, Taplin ME, Sternberg CN, Miller K, de WR, Mulders P, Chi KN, Shore ND, Armstrong AJ, Flaig TW, Flechon A, Mainwaring P, Fleming M, Hainsworth JD, Hirmand M, Selby B, Seely L, de Bono JS. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1187–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer MT, Antonarakis ES. Abiraterone and other novel androgen-directed strategies for the treatment of prostate cancer: a new era of hormonal therapies is born. Ther Adv Urol. 2012;4:167–178. doi: 10.1177/1756287212452196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafi AA, Cox MB, Weigel NL. Androgen receptor splice variants are resistant to inhibitors of Hsp90 and FKBP52, which alter androgen receptor activity and expression. Steroids. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma NL, Massie CE, Ramos-Montoya A, Zecchini V, Scott HE, Lamb AD, MacArthur S, Stark R, Warren AY, Mills IG, Neal DE. The androgen receptor induces a distinct transcriptional program in castration-resistant prostate cancer in man. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small EJ, Baron A, Bok R. Simultaneous antiandrogen withdrawal and treatment with ketoconazole and hydrocortisone in patients with advanced prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;80:1755–1759. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971101)80:9<1755::aid-cncr9>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snoek R, Cheng H, Margiotti K, Wafa LA, Wong CA, Wong EC, Fazli L, Nelson CC, Gleave ME, Rennie PS. In vivo knockdown of the androgen receptor results in growth inhibition and regression of well-established, castration-resistant prostate tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:39–47. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MN, Goodin S, Dipaola RS. Abiraterone in prostate cancer: a new angle to an old problem. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1848–1854. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneja SS. Re: Effect of Abiraterone Acetate and Prednisone Compared with Placebo and Prednisone on Pain Control and Skeletal-Related Events in Patients with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Exploratory Analysis of Data from the COU-AA-301 Randomised Trial. J Urol. 2013;189:1715. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taplin ME, Rajeshkumar B, Halabi S, Werner CP, Woda BA, Picus J, Stadler W, Hayes DF, Kantoff PW, Vogelzang NJ, Small EJ. Androgen receptor mutations in androgen-independent prostate cancer: Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study 9663. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2673–2678. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson VC, Day TK, Bianco-Miotto T, Selth LA, Han G, Thomas M, Buchanan G, Scher HI, Nelson CC, Greenberg NM, Butler LM, Tilley WD. A gene signature identified using a mouse model of androgen receptor-dependent prostate cancer predicts biochemical relapse in human disease. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:662–672. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran C, Ouk S, Clegg NJ, Chen Y, Watson PA, Arora V, Wongvipat J, Smith-Jones PM, Yoo D, Kwon A, Wasielewska T, Welsbie D, Chen CD, Higano CS, Beer TM, Hung DT, Scher HI, Jung ME, Sawyers CL. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science. 2009;324:787–790. doi: 10.1126/science.1168175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turitto G, Di BM, Moraca L, Sasso N, Sepede C, Suriano A, Romito S. Abiraterone acetate: a novel therapeutic option in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Recenti Prog Med. 2012;103:74–78. doi: 10.1701/1045.11391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Gao D, Fukushima H, Inuzuka H, Liu P, Wan L, Sarkar FH, Wei W. Skp2: a novel potential therapeutic target for prostate cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1825:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson PA, Chen YF, Balbas MD, Wongvipat J, Socci ND, Viale A, Kim K, Sawyers CL. Constitutively active androgen receptor splice variants expressed in castration-resistant prostate cancer require full-length androgen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16759–16765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012443107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Jiang YF, Wu B. New agonist-and antagonist-based treatment approaches for advanced prostate cancer. J Int Med Res. 2012;40:1217–1226. doi: 10.1177/147323001204000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka M, Hara T, Hitaka T, Kaku T, Takeuchi T, Takahashi J, Asahi S, Miki H, Tasaka A, Kusaka M. Orteronel (TAK-700), a novel non-steroidal 17,20-lyase inhibitor: effects on steroid synthesis in human and monkey adrenal cells and serum steroid levels in cynomolgus monkeys. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;129:115–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Garcia JA. Targeting the adrenal gland in castration-resistant prostate cancer: a case for orteronel, a selective CYP-17 17,20-lyase inhibitor. Curr Oncol Rep. 2013;15:105–112. doi: 10.1007/s11912-013-0300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]