SUMMARY

Epidemiological studies in humans suggest that skeletal muscle aging is a risk factor for the development of several age-related diseases such as metabolic syndrome, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. Here we review recent studies in mammals and Drosophila highlighting how nutrient- and stress-sensing in skeletal muscle can influence lifespan and overall aging of the organism. In addition to exercise and indirect effects of muscle metabolism, growing evidence suggests that muscle-derived growth factors and cytokines, known as myokines, modulate systemic physiology. Myokines may influence the progression of age-related diseases and contribute to the inter-tissue communication that underlies systemic aging.

Keywords: skeletal muscle aging, systemic aging, myokine signaling, exercise, inter-tissue communication during aging

Introduction

Studies in model organisms have shown that different tissues undergo distinct levels of deterioration during aging (Garigan et al., 2002; Herndon et al., 2002), and that signaling events in a single tissue can affect lifespan, although not all tissues have this ability (Bluher et al., 2003; Libina et al., 2003; Hwangbo et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2005; Taguchi et al., 2007). Endocrine communication (or crosstalk) between aging tissues is an important determinant of organismal aging but the signals involved are largely unknown (Russell and Kahn, 2007; Panowski and Dillin, 2009).

In humans, the mortality rate and pathogenesis of many age-related diseases is associated with the functional status, metabolic demand, and mass of skeletal muscle (Anker et al., 1997; Metter et al., 2002; Nair, 2005; Ruiz et al., 2008), suggesting that this tissue is a key regulator of systemic aging. Recent findings in mammals and Drosophila confirm this hypothesis and indicate that nutrient- and stress-sensing in skeletal muscle influence organismal aging. Here, we review recent studies highlighting the interconnection of skeletal muscle and systemic aging and the possible role of myokines, growth factors and cytokines secreted by muscle cells.

Muscle-specific genetic interventions that influence systemic aging

Muscle is one of the tissues in which age-related changes are particularly prominent in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster and other invertebrates (Herndon et al., 2002; Demontis and Perrimon, 2010). During the course of their short lifespan (~10 weeks), fruit flies display a progressive increase in age-associated apoptosis that is particularly pronounced in muscle and less so in the brain and adipose tissue (Zheng et al., 2005). Moreover, age-related changes such as the accumulation of p62/poly-ubiquitin protein aggregates (Demontis and Perrimon, 2010), gene expression changes (Girardot et al., 2006), decline in protein synthesis (Webster et al., 1980), and increased mitochondrial and nuclear DNA damage (Yui et al., 2003; Garcia et al., 2010) are greater in muscles than in other tissues in Drosophila.

DNA mutations are highly prominent also in the muscle of aged mice (Wang et al., 2001; Szczesny et al., 2011). Furthermore, the accumulation of carbonylated mitochondrial proteins during aging is higher, and the levels of the antioxidant enzymes SOD1, SOD2 and catalase are lower in mouse skeletal muscle than in the liver, kidney, or heart (Szczesny et al., 2011). The high metabolic rate and the mechanical and oxidative stress associated with muscle contraction (i.e., exercise) may explain the accumulation of dysfunctional proteins and DNA damage specifically in skeletal muscle. These findings raise the possibility that the muscle acts as a “sentinel tissue”, i.e. the earlier onset of age-related degeneration in muscle may affect aging in other tissues. Several studies on skeletal muscle-specific genetic interventions in Drosophila and mammals support this model.

In Drosophila, FOXO and 4E-BP signaling specifically in muscles activates the autophagy/lysosome system of protein degradation and organelle turnover not only in muscle but also in the retina, brain, and adipose tissue thereby reducing the age-related accumulation of protein aggregates in all these tissues (Demontis and Perrimon, 2010). This systemic regulation is accompanied by preservation of muscle function, lifespan extension, lower glycemia, and decreased feeding behavior and insulin release (Demontis and Perrimon, 2010).

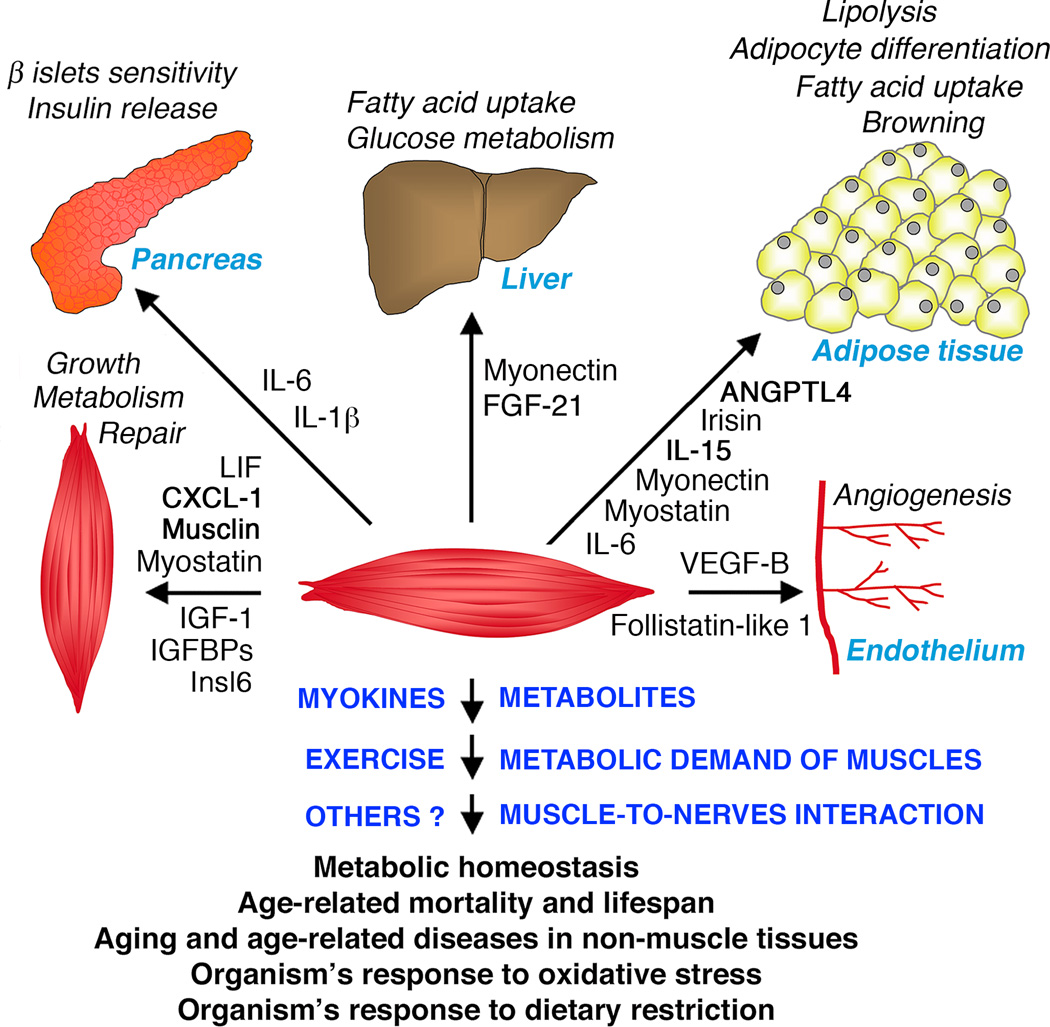

Additional studies have highlighted how oxidative stress resistance in the muscle influences lifespan. For example, the stress-sensing kinase p38 MAPK increases Sod2 levels in Drosophila muscles through the transcription factor Mef2, reduces age-related muscle dysfunction, and extends lifespan (Vrailas-Mortimer et al., 2011). Moreover, adenosine monophosphate protein kinase (AMPK) overexpression in muscles extends lifespan (Stenesen et al., 2013), while muscle-restricted AMPK RNAi has the opposite effect (Tohyama and Yamaguchi, 2010). In addition to regulating age-related mortality, muscle-specific genetic interventions regulate organismal sensitivity to environmental stressors. For example, increased mTOR activity (Patel and Tamanoi, 2006) or decreased Sod2 (Martin et al., 2009), p38 MAPK (Vrailas-Mortimer et al., 2011), or AMPK expression in muscle (Tohyama and Yamaguchi, 2010) reduces the organism’s resistance to oxidative stress. Altogether, these findings in Drosophila suggest that signaling events in muscle delay age-related muscle deterioration but also mitigate age-related functional decline of other tissues, increase the stress resistance of the organism, improve metabolic homeostasis, and extend lifespan (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Systemic regulation of metabolism and aging by skeletal muscle.

Studies in mammals and Drosophila highlight an important role of skeletal muscle in influencing metabolic homeostasis, lifespan, systemic aging, and the progression of age-related diseases. Muscle is also important in the organism’s response to dietary restriction and oxidative stress in Drosophila. Muscle may crosstalk with other tissues via direct muscle-to-nerve interactions, release of metabolites, systemic adaptations deriving from the energy demand of contracting muscles (exercise), and muscle-derived cytokines and growth factors (myokines). In mammals, myokines modulate several metabolic processes in the pancreas, liver, adipose tissue, endothelium, the muscle itself, and other tissues, and may influence systemic aging and lifespan.

In agreement with the findings in Drosophila described above, some muscle-specific genetic manipulations in mice improve metabolic homeostasis and delay systemic age-related degeneration. In particular, increased expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) in muscle promotes mitochondrial biogenesis, enhances aerobic metabolism, and mimics the benefits of endurance training, while it also enhances defenses against oxidative stress (Wenz et al., 2009). In addition, several age-related metabolic defects are delayed, including chronic inflammation and reduction in insulin sensitivity, indicating important systemic consequences of muscle-restricted PGC-1α activity. Conversely, muscle-specific PGC-1α knock-out mice display exercise intolerance, myopathy, and abnormal glucose homeostasis (Handschin et al., 2007a; Handschin et al., 2007b). These systemic effects of PGC-1α activity in muscles presumably result from several PGC-1α-regulated processes including resistance to oxidative stress (Wenz et al., 2009), inhibition of atrophy (Brault et al., 2010), regulation of muscle metabolism, and release of myokines (Bostrom et al., 2012).

Another study reported that muscle overexpression of the cytosolic form of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK-C), a key enzyme in gluconeogenesis, leads to increased spontaneous activity and motor function, higher number of mitochondria, reduced body fat, delayed reproductive aging, and lifespan extension (Hakimi et al., 2007; Hanson and Hakimi, 2008). Although PEPCK-C overexpression in muscles has these profound effects on the organism, the resulting metabolic adaptations and how they influence other tissues are presently unknown.

Although the benefits of PEPCK-C and PGC-1α overexpression in muscles are probably mediated at least in part by increased mitochondrial function, other studies have shown a protective role for mild mitochondrial respiratory uncoupling in muscles, which results in enhanced substrate consumption but decreased ATP production. In mice, skeletal muscle-specific overexpression of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) increases the median lifespan and decreases the incidence of several age-related disease such as lymphomas, diabetes and hypertension (Gates et al., 2007; Keipert et al., 2011).

Mechanistically, mitochondrial uncoupling in muscle in response to UCP1 overexpression activates AMPK, which increases substrate utilization and lipid metabolism (Keipert et al., 2013). Mitochondrial uncoupling also mildly increases oxidative stress, which in turn induces the mitochondrial unfolded protein response that raises antioxidant defense (mitohormesis) and ultimately extends lifespan (Keipert et al., 2013). Protection from obesity and type 2 diabetes has been observed also in mouse models in which moderate mitochondrial uncoupling was induced by muscle-specific ablation of either the mitochondrial intermembrane protein AIF (apoptosis inducing factor; Pospisilik et al., 2007) or TIF2 (transcriptional intermediary factor 2), a regulator of UCP3 expression (Duteil et al., 2010). Taken together, these findings indicate that metabolic adaptations and signaling events in muscles influence lifespan and disease progression in other tissues during aging in Drosophila and mice.

Role of exercise in determining lifespan and preventing age-related diseases

Exercise and muscle functional capacity are important predictors of age-related mortality in humans (Anker et al., 1997; Metter et al., 2002; Ruiz et al., 2011). Several studies indicate protective effects of exercise also in animal models. For example, endurance exercise rescues mitochondrial defects and premature aging of mice with defective proofreading-exonuclease activity of mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ (Safdar et al., 2011). In transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, exercise protects animals from neurodegeneration (Zigmond et al., 2009; Belarbi et al., 2011; Garcia-Mesa et al., 2011). Moreover, breast and colon cancer progression is inhibited by physical activity (Hojman et al., 2011), and exercise can extend lifespan in rats (Holloszy, 1988; Holloszy, 1993) and probably also in humans (Ruiz et al., 2011).

However, the effects of exercise may depend on the specific disease and genetic background (Bronikowski et al., 2006). For example, exercise activates the autophagy/lysosome pathway in muscle, liver, pancreas, and adipose tissue of mice (He et al., 2012), and it may delay systemic aging by promoting the turnover of cellular components in these tissues. However, exercise does not activate autophagy in old age (Ludatscher et al., 1983), and it even may be detrimental in disease conditions in which the autophagic flux is compromised (Grumati et al., 2011). Moreover, different exercise training programs appear to have distinct outcomes. For example, although climbing exercise preserves motor capacity in Drosophila and increases mitochondrial function (Piazza et al., 2009), flight activity appears to shorten lifespan in Drosophila and other insects, perhaps due to lipid peroxidation and the oxidative damage of mitochondrial proteins (Yan and Sohal, 2000; Magwere et al., 2006; Tolfsen et al., 2011).

The interconnections between exercise, muscle function, and lifespan are certainly complex, and lifespan and motor decline are not necessarily linked in Drosophila. For example, flies bearing mutations in the chico/Insulin Receptor Substrate (IRS) have an extended lifespan and delayed locomotor decline (Gargano et al., 2005). However, long-lived methuselah flies, which are also resistant to oxidative stress, suffer functional decline in muscle with aging (Cook-Wiens and Grotewiel, 2002; Petrosyan et al., 2007).

Recent studies indicate that muscle function and exercise have important roles in modulating lifespan in response to dietary restriction (DR). DR increases spontaneous movement in mice and flies (Partridge et al., 2005), and the resulting increase in muscle’s metabolic demand likely contributes to the organism-wide beneficial effects of DR. In agreement with this hypothesis, wing clipping abrogates the lifespan extension associated with DR in Drosophila (Katewa et al., 2012).

In addition to exercise and muscle function, muscle mass is also an important predictor of mortality and can influence the progression of age-related diseases in humans (Astrand, 1992; Wisloff et al., 2005). Strikingly, reducing muscle wasting during cancer cachexia increases the survival of tumor-bearing mice, even if tumor growth is not affected (Zhou et al., 2010). Moreover, transplanting muscle stem cells from young mice into old mice delays sarcopenia and extends lifespan (Lavasani et al., 2012). Thus, both muscle mass and function have important effects on age-related diseases and lifespan.

Endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine functions of muscle via myokines

Because of its sheer mass and high metabolic rate during exercise, muscle has a profound influence on body metabolism. In addition to the indirect effect of muscle’s metabolic demand, it is becoming evident that muscle also has an underappreciated capacity to secrete cytokines and growth factors, known as myokines, that can act in an autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine fashion (Fig. 1). Some myokines are primarily expressed in muscle while others are expressed also in other tissues. Myostatin is one of the best-characterized myokines and it is expressed predominantly in skeletal muscle. Myostatin knock-out animals have doubling of muscle mass (Lee, 2004), and myostatin inhibition has been proposed to delay age-related sarcopenia by preserving muscle mass (Siriett et al., 2006; LeBrasseur et al., 2009) and possibly strength (Whittemore et al., 2003; Haidet et al., 2008). However, other studies have indicated that the muscles in myostatin-null mice, though increased in mass, are not protected from sarcopenia (Morissette et al., 2009; Wang and McPherron, 2012), and with aging may even display a greater than expected decline in force development (Amthor et al., 2007). Moreover, inhibition of myostatin signaling retards the loss of muscle mass associated with cancer cachexia (Zhou et al., 2010) but not the muscle atrophy that follows denervation (Sartori et al., 2009), suggesting that myostatin is not a general homeostatic regulator of muscle mass.

In addition to the regulation of muscle mass, myostatin knock-out animals have improved insulin sensitivity and reduced fat mass (McPherron, 2010). Although these systemic effects indirectly derive from increased muscle mass (Guo et al., 2009), myostatin is also released into the circulation and can act on non-muscle tissues (Zimmers et al., 2002; McPherron, 2010). In particular, myostatin influences adipogenesis to generate immature adipocytes with increased insulin sensitivity and glucose oxidation, leading to systemic resistance to diet-induced obesity (Feldman et al., 2006). These findings suggest that myostatin my have important endocrine functions.

In addition to myostatin, muscle produces other myokines, some of which in response to exercise, including insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1; Arnold et al., 2010; Pedersen and Febbraio, 2012). Although muscle-derived IGF-1 is not detected in the circulation (Hede et al., 2012), it induces muscle hypertrophy in an autocrine/paracrine fashion following exercise (Vinciguerra et al., 2010). Furthermore, several IGF-binding proteins (IGFBP-3, -4, -5, and -6) are expressed in muscles. They differ in their capacity to enhance or block the anabolic effects of IGF-1 by sequestering it, extending its half-life, or inhibiting its interaction with muscle IGF-1 receptors (Silverman et al., 1995; James et al., 1996; Vinciguerra et al., 2010). Interestingly, the expression of IGFBP-3 and -5 decreases in the soleus muscle during aging (Spangenburg et al., 2003) and in several types of muscle atrophy in mice (Lecker et al., 2004). Thus, an autocrine regulatory role in muscle is clear, but the effects of these binding proteins on other tissues, such as bone, remain unclear. There are, in fact, many indications that compensatory changes in bone structure and mass occur in response to changes in muscular activity. Exercise-induced myokines (e.g., IGF-1) most likely mediate such effects.

Several myokines appear to mediate the endocrine functions of muscles on other tissues and organs (Fig. 1). Exercise increases systemic insulin sensitivity, and some myokines, including IL-6, have been proposed to act on the insulin-producing pancreatic beta islets. IL-6 promotes the expression of prohormone convertase PC1/3 in pancreatic alpha cells, which leads to the production of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). In turn, GLP-1 sensitizes pancreatic beta cells to glucose and thus promotes insulin release after food intake (Ellingsgaard et al., 2011). Although IL-6 expression and IL-6 secretion rise during exercise (Ostrowski et al., 1998), the levels of many other myokines, hormones, and metabolites change after exercise. Some of these factors (e.g., lactate) directly regulate insulin secretion (Federspil et al., 1980), and therefore it remains unknown whether IL-6 plays a fundamental role in exercise-induced effects. Furthermore, IL-6 levels rise in highly catabolic conditions (e.g., sepsis and cancer) and contribute to the hepatic production of acute-phase proteins, inflammation, and the progression of type 2 diabetes. Thus, the function of IL-6 appears to differ based on the physiologic context (Kristiansen and Mandrup-Poulsen, 2005). In addition to IL-6, other inflammatory cytokines generally viewed as products of macrophages (i.e., TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-15) can be released from muscles. These factors have been implicated in regulating insulin production by pancreatic beta islets but they also have well-established effects on the endothelium, white blood cells, and hepatic function (Alexandraki et al., 2006; Handschin et al., 2007b).

Myokines that influence adipocyte metabolism include myonectin, IL-6, IL-15, angiopoietin-like protein 4 (ANGPTL4), and the chemokine CXCL-1. Exercise increases IL-15 expression in muscles, and transgenic mice overexpressing IL-15 have increased exercise endurance and fatty acid oxidation (Quinn et al., 2013) and improved insulin sensitivity (Barra et al., 2012). Signaling crosstalk between muscle and adipose tissue is also mediated by ANGPTL4. ANGPTL4 is induced and secreted from skeletal muscles in response to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-δ (PPAR-δ) activity, which is acutely induced by exercise and plasma fatty acids. Release of ANGPTL4 from muscle promotes lipolysis in white adipose tissue, which in turn supplies fatty acids for sustaining oxidative metabolism in muscle during exercise (Staiger et al., 2009). Exercise also induces CXCL-1, which increases lipolysis and fatty acid mobilization from adipose tissue, and its receptor, CXCR2, which increases fatty acid oxidation in muscle (Pedersen et al., 2012).

Recently, Spiegelman and coworkers discovered irisin, a new exercise-induced myokine that regulates beige/brown fat development. Exercise increases PGC-1α levels, which promotes transcription of the irisin precursor FNDC5, a type-I transmembrane protein. FNDC5 is then cleaved, and the extracellular portion, irisin, is released into the circulation (Bostrom et al., 2012). Irisin then acts on white adipose cells to promote the expression of genes responsible for the development of beige adipocytes, which are related to the thermogenic cells of brown adipose tissue (Wu et al., 2012), a tissue that consumes metabolic substrates for heat production. Therefore, by promoting the development of beige adipocytes, irisin has great therapeutic potential as a treatment for diabetes and diet-induced obesity (Bostrom et al., 2012). PGC-1α also enhances the expression and release of other myokines such as VEGF (Arany et al., 2008), IL-15, and the uncharacterized factors Lrg1 and Timp4 (Bostrom et al., 2012), all of which may help explain the benefits of exercise and PGC-1α on lifespan.

Nutrients and nutrient-sensing pathways also regulate the expression of some myokines. For example, the expression of musclin, a myokine almost exclusively expressed in skeletal muscles, is induced by insulin (Nishizawa et al., 2004) and repressed by the nutrient- and stress-sensing transcription factor FoxO1 (Yasui et al., 2007). Musclin reduces glucose uptake and glycogen synthesis in muscles and may contribute to the development of insulin resistance (Nishizawa et al., 2004). Insulin also induces the expression of other myokines, including Insulin-like 6 (Insl6) and fibroblast growth factor-21 (FGF-21), via its downstream kinase AKT (Izumyia et al., 2008; Zeng et al., 2010). FGF-21 acts primarily on the liver and prevents insulin resistance and diet-induced obesity (Kharitonenkov and Shanafelt, 2009). Myonectin is another nutrient-responsive myokine that is secreted predominantly by muscle (especially oxidative fibers) in response to glucose and palmitate and promotes fatty acid uptake by hepatocytes and adipocytes (Seldin et al., 2012). IL-6 expression is also regulated by nutrients (intramuscular glycogen levels), in addition to exercise (Keller et al., 2001).

Many other myokines are known. Follistatin-like 1 promotes endothelial cell migration and revascularization of ischemic tissues (Ouchi et al., 2008). Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and Insl6 are both involved in muscle regeneration (Broholm et al., 2010; Zeng et al., 2010). Oncostatin M (OSM) and secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) suppress breast cancer and colon cancer, respectively (Hojman et al., 2011; Aoi et al., 2013). Additional putative myokines have been identified by mass-spectrometry but have not yet been functionally characterized (Henningsen et al., 2010; Norheim et al., 2011).

In addition to myokines, mechanisms such as the release of metabolites from muscle and muscle-to-nerve interactions may mediate some of the systemic effects of muscle on the organism’s physiology. For example, muscle contraction stimulates posterior hypothalamic neurons (Waldrop and Stremel, 1989), which may, in turn, induce systemic adaptive responses to exercise.

Although myokines are emerging as important endocrine modulators of metabolic homeostasis, they may also function in aging. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that the levels of some myokines change during aging in mammals (Baumann et al., 2003; Gangemi et al., 2005). Currently, there are no studies on myokines in Drosophila. However, its short lifespan and extensive genetic toolkit make this organism an excellent model in which to study evolutionarily conserved myokines and their role in inter-tissue communication during aging.

Conclusions

In this review, we highlighted the evidence for a key role of skeletal muscle in the systemic regulation of aging and age-related diseases. Studies in mammals and Drosophila offer complementary advantages for dissecting the signaling crosstalk between muscle and other tissues and its role in lifespan determination. The emerging evidence that muscles release myokines and thus influence the metabolism of the organism may have important medical applications. Finally, because many myokines are induced by exercise, understanding their actions may shed light on how the metabolism of different tissues is integrated during and after exercise, and how exercise can protect against age-associated diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding to FD from ALSAC, to ALG from the MDA and the NIH (AR055255), and to NP from the NIH (R01AR057352). The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Alexandraki K, Piperi C, Kalofoutis C, Singh J, Alaveras A, Kalofoutis A. Inflammatory process in type 2 diabetes: The role of cytokines. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006;1084:89–117. doi: 10.1196/annals.1372.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amthor H, Macharia R, Navarrete R, Schuelke M, Brown SC, Otto A, Voit T, Muntoni F, Vrbova G, Partridge T, et al. Lack of myostatin results in excessive muscle growth but impaired force generation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2007;104:1835–1840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604893104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker SD, Ponikowski P, Varney S, Chua TP, Clark AL, Webb-Peploe KM, Harrington D, Kox WJ, Poole-Wilson PA, Coats AJ. Wasting as independent risk factor for mortality in chronic heart failure. Lancet. 1997;349:1050–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoi W, Naito Y, Takagi T, Tanimura Y, Takanami Y, Kawai Y, Sakuma K, Hang LP, Mizushima K, Hirai Y, et al. A novel myokine, secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC), suppresses colon tumorigenesis via regular exercise. Gut. 2013;62:882–889. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arany Z, Foo SY, Ma Y, Ruas JL, Bommi-Reddy A, Girnun G, Cooper M, Laznik D, Chinsomboon J, Rangwala SM, et al. HIF-independent regulation of VEGF and angiogenesis by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha. Nature. 2008;451:1008–1012. doi: 10.1038/nature06613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold AS, Egger A, Handschin C. PGC-1alpha and Myokines in the Aging Muscle - A Mini-Review. Gerontology. 2010;57:37–43. doi: 10.1159/000281883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrand PO. Physical activity and fitness. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1992;55:1231S–1236S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/55.6.1231S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barra NG, Chew MV, Holloway AC, Ashkar AA. Interleukin-15 treatment improves glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in obese mice. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2012;14:190–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AP, Ibebunjo C, Grasser WA, Paralkar VM. Myostatin expression in age and denervation-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal. Interact. 2003;3:8–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belarbi K, Burnouf S, Fernandez-Gomez FJ, Laurent C, Lestavel S, Figeac M, Sultan A, Troquier L, Leboucher A, Caillierez R, et al. Beneficial effects of exercise in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease-like Tau pathology. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011;43:486–494. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blüher M, Kahn BB, Kahn CR. Extended longevity in mice lacking the insulin receptor in adipose tissue. Science. 2003;299:572–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1078223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostrom P, Wu J, Jedrychowski MP, Korde A, Ye L, Lo JC, Rasbach KA, Bostrom EA, Choi JH, Long JZ, et al. A PGC1-alpha-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature. 2012;481:463–468. doi: 10.1038/nature10777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault JJ, Jespersen JG, Goldberg AL. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1alpha or 1beta overexpression inhibits muscle protein degradation, induction of ubiquitin ligases, and disuse atrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:19460–19471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.113092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broholm C, Laye MJ, Brandt C, Vadalasetty R, Pilegaard H, Pedersen BK, Scheele C. LIF is a contraction-induced myokine stimulating human myocyte proliferation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011;111:251–259. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01399.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronikowski AM, Morgan TJ, Garland T, Jr, Carter PA. The evolution of aging and age-related physical decline in mice selectively bred for high voluntary exercise. Evolution. 2006;60:1494–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook-Wiens E, Grotewiel MS. Dissociation between functional senescence and oxidative stress resistance in Drosophila. Exp. Gerontol. 2002;37:1347–1357. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demontis F, Perrimon N. FOXO/4E-BP signaling in Drosophila muscles regulates organism-wide proteostasis during aging. Cell. 2010;143:813–825. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duteil D, Chambon C, Ali F, Malivindi R, Zoll J, Kato S, Geny B, Chambon P, Metzger D. The transcriptional coregulators TIF2 and SRC-1 regulate energy homeostasis by modulating mitochondrial respiration in skeletal muscles. Cell Metab. 2010;12:496–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingsgaard H, Hauselmann I, Schuler B, Habib AM, Baggio LL, Meier DT, Eppler E, Bouzakri K, Wueest S, Muller YD, et al. Interleukin-6 enhances insulin secretion by increasing glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion from L cells and alpha cells. Nat. Med. 2011;17:1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/nm.2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federspil G, Zaccaria M, Pedrazzoli S, Zago E, DePalo C, Scandellari C. Effects of sodium DL-lactate on insulin secretion in anesthetized dogs. Diabetes. 1980;29:33–36. doi: 10.2337/diab.29.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman BJ, Streeper RS, Farese RV, Jr, Yamamoto KR. Myostatin modulates adipogenesis to generate adipocytes with favorable metabolic effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:15675–15680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607501103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangemi S, Basile G, Monti D, Merendino RA, Di Pasquale G, Bisignano U, Nicita-Mauro V, Franceschi C. Age-related modifications in circulating IL-15 levels in humans. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:245–247. doi: 10.1155/MI.2005.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AM, Calder RB, Dolle ME, Lundell M, Kapahi P, Vijg J. Age- and temperature-dependent somatic mutation accumulation in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Mesa Y, Lopez-Ramos JC, Gimenez-Llort L, Revilla S, Guerra R, Gruart A, Laferla FM, Cristofol R, Delgado-Garcia JM, Sanfeliu C. Physical exercise protects against Alzheimer's disease in 3xTg-AD mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24:421–454. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-101635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargano JW, Martin I, Bhandari P, Grotewiel MS. Rapid iterative negative geotaxis (RING): a new method for assessing age-related locomotor decline in Drosophila. Exp. Gerontol. 2005;40:386–395. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garigan D, Hsu AL, Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Kenyon C. Genetic analysis of tissue aging in Caenorhabditis elegans: a role for heat-shock factor and bacterial proliferation. Genetics. 2002;161:1101–1112. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.3.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates AC, Bernal-Mizrachi C, Chinault SL, Feng C, Schneider JG, Coleman T, Malone JP, Townsend RR, Chakravarthy MV, Semenkovich CF. Respiratory uncoupling in skeletal muscle delays death and diminishes age-related disease. Cell Metab. 2007;6:497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardot F, Lasbleiz C, Monnier V, Tricoire H. Specific age-related signatures in Drosophila body parts transcriptome. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumati P, Coletto L, Schiavinato A, Castagnaro S, Bertaggia E, Sandri M, Bonaldo P. Physical exercise stimulates autophagy in normal skeletal muscles but is detrimental for collagen VI deficient muscles. Autophagy. 2011;7:1415–1423. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.12.17877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T, Jou W, Chanturiya T, Portas J, Gavrilova O, McPherron AC. Myostatin inhibition in muscle, but not adipose tissue, decreases fat mass and improves insulin sensitivity. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidet AM, Rizo L, Handy C, Umapathi P, Eagle A, Shilling C, Boue D, Martin PT, Sahenk Z, Mendell JR, Kaspar BK. Long-term enhancement of skeletal muscle mass and strength by single gene administration of myostatin inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:4318–4322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709144105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handschin C, Chin S, Li P, Liu F, Maratos-Flier E, Lebrasseur NK, Yan Z, Spiegelman BM. Skeletal muscle fiber-type switching, exercise intolerance, and myopathy in PGC-1alpha muscle-specific knock-out animals. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:30014–30021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704817200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakimi P, Yang J, Casadesus G, Massillon D, Tolentino-Silva F, Nye CK, Cabrera ME, Hagen DR, Utter CB, Baghdy Y, et al. Overexpression of the cytosolic form of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (GTP) in skeletal muscle repatterns energy metabolism in the mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:32844–32855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706127200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handschin C, Choi CS, Chin S, Kim S, Kawamori D, Kurpad AJ, Neubauer N, Hu J, Mootha VK, Kim YB, et al. Abnormal glucose homeostasis in skeletal muscle-specific PGC-1alpha knockout mice reveals skeletal muscle-pancreatic beta cell crosstalk. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:3463–3474. doi: 10.1172/JCI31785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RW, Hakimi P. Born to run; the story of the PEPCK-Cmus mouse. Biochimie. 2008;90:838–842. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Bassik MC, Moresi V, Sun K, Wei Y, Zou Z, An Z, Loh J, Fisher J, Sun Q, et al. Exercise-induced BCL2-regulated autophagy is required for muscle glucose homeostasis. Nature. 2012;481:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nature10758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hede MS, Salimova E, Piszczek A, Perlas E, Winn N, Nastasi T, Rosenthal N. E-peptides control bioavailability of IGF-1. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henningsen J, Rigbolt KT, Blagoev B, Pedersen BK, Kratchmarova I. Dynamics of the skeletal muscle secretome during myoblast differentiation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2010;9:2482–2496. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.002113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndon LA, Schmeissner PJ, Dudaronek JM, Brown PA, Listner KM, Sakano Y, Paupard MC, Hall DH, Driscoll M. Stochastic and genetic factors influence tissue-specific decline in ageing C. elegans. Nature. 2002;419:808–814. doi: 10.1038/nature01135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojman P, Dethlefsen C, Brandt C, Hansen J, Pedersen L, Pedersen BK. Exercise-induced muscle-derived cytokines inhibit mammary cancer cell growth. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;301:E504–E510. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00520.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloszy JO. Exercise and longevity: studies on rats. J. Gerontol. 1988;43:B149–B151. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.6.b149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloszy JO. Exercise increases average longevity of female rats despite increased food intake and no growth retardation. J. Gerontol. 1993;48:B97–B100. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.3.b97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwangbo DS, Gershman B, Tu MP, Palmer M, Tatar M. Drosophila dFOXO controls lifespan and regulates insulin signalling in brain and fat body. Nature. 2004;429:562–566. doi: 10.1038/nature02549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumiya Y, Bina HA, Ouchi N, Akasaki Y, Kharitonenkov A, Walsh K. FGF21 is an Akt-regulated myokine. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:3805–3810. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James PL, Stewart CE, Rotwein P. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5 modulates muscle differentiation through an insulin-like growth factor-dependent mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 1996;133:683–693. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.3.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katewa SD, Demontis F, Kolipinski M, Hubbard A, Gill MS, Perrimon N, Melov S, Kapahi P. Intramyocellular Fatty-Acid Metabolism Plays a Critical Role in Mediating Responses to Dietary Restriction in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Metab. 2012;16:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keipert S, Voigt A, Klaus S. Dietary effects on body composition, glucose metabolism, and longevity are modulated by skeletal muscle mitochondrial uncoupling in mice. Aging Cell. 2011;10:122–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keipert S, Ost M, Chadt A, Voigt A, Ayala V, Portero-Otin M, Pamplona R, Al-Hasani H, Klaus S. Skeletal muscle uncoupling-induced longevity in mice is linked to increased substrate metabolism and induction of the endogenous antioxidant defense system. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;304:E495–E506. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00518.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C, Steensberg A, Pilegaard H, Osada T, Saltin B, Pedersen BK, Neufer PD. Transcriptional activation of the IL-6 gene in human contracting skeletal muscle: influence of muscle glycogen content. FASEB J. 2001;15:2748–2750. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0507fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharitonenkov A, Shanafelt AB. FGF21: a novel prospect for the treatment of metabolic diseases. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2009;10:359–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen OP, Mandrup-Poulsen T. Interleukin-6 and diabetes: the good, the bad, or the indifferent? Diabetes. 2005;54:S114–S124. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.suppl_2.s114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavasani M, Robinson AR, Lu A, Song M, Feduska JM, Ahani B, Tilstra JS, Feldman CH, Robbins PD, Niedernhofer LJ, et al. Muscle-derived stem/progenitor cell dysfunction limits healthspan and lifespan in a murine progeria model. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:608. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBrasseur NK, Schelhorn TM, Bernardo BL, Cosgrove PG, Loria PM, Brown TA. Myostatin inhibition enhances the effects of exercise on performance and metabolic outcomes in aged mice. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2009;64:940–948. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecker SH, Jagoe RT, Gilbert A, Gomes M, Baracos V, Bailey J, Price SR, Mitch WE, Goldberg AL. Multiple types of skeletal muscle atrophy involve a common program of changes in gene expression. Faseb J. 2004;18:39–51. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0610com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ. Regulation of muscle mass by myostatin. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;20:61–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.012103.135836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libina N, Berman JR, Kenyon C. Tissue-specific activities of C. elegans DAF-16 in the regulation of lifespan. Cell. 2003;115:489–502. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00889-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludatscher R, Silbermann M, Gershon D, Reznick A. The effects of enforced running on the gastrocnemius muscle in aging mice: an ultrastructural study. Exp. Gerontol. 1983;18:113–123. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(83)90004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magwere T, Pamplona R, Miwa S, Martinez-Diaz P, Portero-Otin M, Brand MD, Partridge L. Flight activity, mortality rates, and lipoxidative damage in Drosophila. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2006;61:136–145. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin I, Jones MA, Rhodenizer D, Zheng J, Warrick JM, Seroude L, Grotewiel M. Sod2 knockdown in the musculature has whole-organism consequences in Drosophila. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;47:803–813. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherron AC. Metabolic functions of Myostatin and GDF11. Immunol. Endocr. Metab. Agents Med. Chem. 2010;10:217–231. doi: 10.2174/187152210793663810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metter EJ, Talbot LA, Schrager M, Conwit R. Skeletal muscle strength as a predictor of all-cause mortality in healthy men. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2002;57:B359–B365. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.10.b359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morissette MR, Stricker JC, Rosenberg MA, Buranasombati C, Levitan EB, Mittleman MA, Rosenzweig A. Effects of myostatin deletion in aging mice. Aging Cell. 2009;8:573–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair KS. Aging muscle. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005;81:953–963. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa H, Matsuda M, Yamada Y, Kawai K, Suzuki E, Makishima M, Kitamura T, Shimomura I. Musclin, a novel skeletal muscle-derived secretory factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:19391–19395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norheim F, Raastad T, Thiede B, Rustan AC, Drevon CA, Haugen F. Proteomic identification of secreted proteins from human skeletal muscle cells and expression in response to strength training. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;301:E1013–E1021. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00326.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski K, Rohde T, Zacho M, Asp S, Pedersen BK. Evidence that interleukin-6 is produced in human skeletal muscle during prolonged running. J. Physiol. 1998;508:949–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.949bp.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouchi N, Oshima Y, Ohashi K, Higuchi A, Ikegami C, Izumiya Y, Walsh K. Follistatin-like 1, a secreted muscle protein, promotes endothelial cell function and revascularization in ischemic tissue through a nitric-oxide synthase-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:32802–32811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803440200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panowski SH, Dillin A. Signals of youth: endocrine regulation of aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;20:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge L, Piper MD, Mair W. Dietary restriction in Drosophila. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2005;126:938–950. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel PH, Tamanoi F. Increased Rheb-TOR signaling enhances sensitivity of the whole organism to oxidative stress. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:4285–4292. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscles, exercise and obesity: skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012;8:457–465. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen L, Olsen CH, Pedersen BK, Hojman P. Muscle-derived expression of the chemokine CXCL1 attenuates diet-induced obesity and improves fatty acid oxidation in the muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;302:E831–E840. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00339.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrosyan A, Hsieh IH, Saberi K. Age-dependent stability of sensorimotor functions in the life-extended Drosophila mutant methuselah. Behav. Genet. 2007;37:585–594. doi: 10.1007/s10519-007-9159-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza N, Gosangi B, Devilla S, Arking R, Wessells R. Exercise-training in young Drosophila melanogaster reduces age-related decline in mobility and cardiac performance. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pospisilik JA, Knauf C, Joza N, Benit P, Orthofer M, Cani PD, Ebersberger I, Nakashima T, Sarao R, Neely G, et al. Targeted deletion of AIF decreases mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and protects from obesity and diabetes. Cell. 2007;131:476–491. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter CJ, Tasic B, Russler EV, Liang L, Luo L. The Q system: a repressible binary system for transgene expression, lineage tracing, and mosaic analysis. Cell. 2010;141:536–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn LS, Anderson BG, Conner JD, Wolden-Hanson T. IL-15 overexpression promotes endurance, oxidative energy metabolism, and muscle PPARδ, SIRT1, PGC-1α, and PGC-1β expression in male mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154:232–245. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz JR, Sui X, Lobelo F, Morrow JR, Jr, Jackson AW, Sjöström M, Blair SN. Association between muscular strength and mortality in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a439. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz JR, Moran M, Arenas J, Lucia A. Strenuous endurance exercise improves life expectancy: it's in our genes. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011;45:159–161. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.075085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell SJ, Kahn C. Endocrine regulation of ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;8:681–691. doi: 10.1038/nrm2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safdar A, Bourgeois JM, Ogborn DI, Little JP, Hettinga BP, Akhtar M, Thompson JE, Melov S, Mocellin NJ, Kujoth GC, et al. Endurance exercise rescues progeroid aging and induces systemic mitochondrial rejuvenation in mtDNA mutator mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2011;108:4135–4140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019581108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartori R, Milan G, Patron M, Mammucari C, Blaauw B, Abraham R, Sandri M. Smad2 and 3 transcription factors control muscle mass in adulthood. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2009;296:C1248–C1257. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00104.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seldin MM, Peterson JM, Byerly MS, Wei Z, Wong GW. Myonectin (CTRP15), a novel myokine that links skeletal muscle to systemic lipid homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:11968–11980. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.336834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman LA, Cheng ZQ, Hsiao D, Rosenthal SM. Skeletal muscle cell-derived insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding proteins inhibit IGF-I-induced myogenesis in rat L6E9 cells. Endocrinology. 1995;136:720–726. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.2.7530651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siriett V, Platt L, Salerno MS, Ling N, Kambadur R, Sharma M. Prolonged absence of myostatin reduces sarcopenia. J. Cell. Physiol. 2006;209:866–873. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangenburg EE, Abraha T, Childs TE, Pattison JS, Booth FW. Skeletal muscle IGF-binding protein-3 and -5 expressions are age, muscle, and load dependent. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;284:E340–E350. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00253.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiger H, Haas C, Machann J, Werner R, Weisser M, Schick F, Machicao F, Stefan N, Fritsche A, Häring HU. Muscle-derived angiopoietin-like protein 4 is induced by fatty acids via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-delta and is of metabolic relevance in humans. Diabetes. 2009;58:579–589. doi: 10.2337/db07-1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenesen D, Suh JM, Seo J, Yu K, Lee KS, Kim JS, Min KJ, Graff JM. Adenosine Nucleotide Biosynthesis and AMPK Regulate Adult Life Span and Mediate the Longevity Benefit of Caloric Restriction in Flies. Cell Metab. 2013;17:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczesny B, Tann AW, Mitra S. Age- and tissue-specific changes in mitochondrial and nuclear DNA base excision repair activity in mice: Susceptibility of skeletal muscles to oxidative injury. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2011;131:330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi A, Wartschow LM, White MF. Brain IRS2 signaling coordinates life span and nutrient homeostasis. Science. 2007;317:369–372. doi: 10.1126/science.1142179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolfsen CC, Baker N, Kreibich C, Amdam GV. Flight restriction prevents associative learning deficits but not changes in brain protein-adduct formation during honeybee ageing. J. Exp. Biol. 2011;214:1322–1332. doi: 10.1242/jeb.049155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohyama D, Yamaguchi A. A critical role of SNF1A/dAMPKalpha (Drosophila AMP-activated protein kinase alpha) in muscle on longevity and stress resistance in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;394:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinciguerra M, Musaro A, Rosenthal N. Regulation of muscle atrophy in aging and disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010;694:211–233. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7002-2_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrailas-Mortimer A, del Rivero T, Mukherjee S, Nag S, Gaitanidis A, Kadas D, Consoulas C, Duttaroy A, Sanyal S. A muscle-specific p38 MAPK/Mef2/MnSOD pathway regulates stress, motor function, and life span in Drosophila. Dev. Cell. 2011;21:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop TG, Stremel RW. Muscular contraction stimulates posterior hypothalamic neurons. Am. J. Physiol. 1989;256:R348–R356. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.256.2.R348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, McPherron AC. Myostatin inhibition induces muscle fibre hypertrophy prior to satellite cell activation. J. Physiol. 2012;590:2151–2165. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.226001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Michikawa Y, Mallidis C, Bai Y, Woodhouse L, Yarasheski KE, Miller CA, Askanas V, Engel WK, Bhasin S, et al. Muscle-specific mutations accumulate with aging in critical human mtDNA control sites for replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2001;98:4022–4027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061013598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MC, Bohmann D, Jasper H. JNK extends life span and limits growth by antagonizing cellular and organism-wide responses to insulin signaling. Cell. 2005;121:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster GC, Beachell VT, Webster SL. Differential decrease in protein synthesis by microsomes from aging Drosophila melanogaster. Exp. Gerontol. 1980;15:495–497. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(80)90058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenz T, Rossi SG, Rotundo RL, Spiegelman BM, Moraes CT. Increased muscle PGC-1alpha expression protects from sarcopenia and metabolic disease during aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:20405–20410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911570106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Whittemore LA, Song K, Li X, Aghajanian J, Davies M, Girgenrath S, Hill JJ, Jalenak M, Kelley P, Knight A, et al. Inhibition of myostatin in adult mice increases skeletal muscle mass and strength. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;300:965–971. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02953-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisloff U, Najjar SM, Ellingsen O, Haram PM, Swoap S, Al-Share Q, Fernstrom M, Rezaei K, Lee SJ, Koch LG, Britton SL. Cardiovascular risk factors emerge after artificial selection for low aerobic capacity. Science. 2005;307:418–420. doi: 10.1126/science.1108177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Bostrom P, Sparks LM, Ye L, Choi JH, Giang AH, Khandekar M, Virtanen KA, Nuutila P, Schaart G, et al. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell. 2012;150:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan LJ, Sohal RS. Prevention of flight activity prolongs the life span of the housefly, Musca domestica, and attenuates the age-associated oxidative damage to specific mitochondrial proteins. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000;29:1143–1150. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00423-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui A, Nishizawa H, Okuno Y, Morita K, Kobayashi H, Kawai K, Matsuda M, Kishida K, Kihara S, Kamei Y, Ogawa Y, Funahashi T, Shimomura I. Foxo1 represses expression of musclin, a skeletal muscle-derived secretory factor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;364:358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yui R, Ohno Y, Matsuura ET. Accumulation of deleted mitochondrial DNA in aging Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Genet. Syst. 2003;78:245–251. doi: 10.1266/ggs.78.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L, Akasaki Y, Sato K, Ouchi N, Izumiya Y, Walsh K. Insulin-like 6 is induced by muscle injury and functions as a regenerative factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:36060–36069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.160879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Edelman SW, Tharmarajah G, Walker DW, Pletcher SD, Seroude L. Differential patterns of apoptosis in response to aging in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U S A. 2005;102:12083–12088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503374102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Wang JL, Lu J, Song Y, Kwak KS, Jiao Q, Rosenfeld R, Chen Q, Boone T, Simonet WS, et al. Reversal of cancer cachexia and muscle wasting by ActRIIB antagonism leads to prolonged survival. Cell. 2010;142:531–543. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond MJ, Cameron JL, Leak RK, Mirnics K, Russell VA, Smeyne RJ, Smith AD. Triggering endogenous neuroprotective processes through exercise in models of dopamine deficiency. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2009;15:S42–S45. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70778-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmers TA, Davies MV, Koniaris LG, Haynes P, Esquela AF, Tomkinson KN, McPherron AC, Wolfman NM, Lee SJ. Induction of cachexia in mice by systemically administered myostatin. Science. 2002;296:1486–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.1069525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]