Abstract

Background and Aims Hordeum marinum

is a species complex that includes the diploid subspecies marinum and both diploid and tetraploid forms of gussoneanum. Their relationships, the rank of the taxa and the origin of the polyploid forms remain points of debate. The present work reports a comparative karyotype analysis of six H. marinum accessions representing all taxa and cytotypes.

Methods

Karyotypes were determined by analysing the chromosomal distribution of several tandemly repeated sequences, including the Triticeae cloned probes pTa71, pTa794, pAs1 and pSc119·2 and the simple sequence repeats (SSRs) (AG)10, (AAC)5, (AAG)5, (ACT)5 and (ATC)5.

Key Results

The identification of each chromosome pair in all subspecies and cytotypes is reported for the first time. Homologous relationships are also established. Wide karyotypic differences were detected within marinum accessions. Specific chromosomal markers characterized and differentiated the genomes of marinum and diploid gussoneanum. Two subgenomes were detected in the tetraploids. One of these had the same chromosome complement as diploid gussoneanum; the second subgenome, although similar to the chromosome complement of diploid H. marinum sensu lato, appeared to have no counterpart in the marinum accessions analysed here.

Conclusions

The tetraploid forms of gussoneanum appear to have come about through a cross between a diploid gussoneanum progenitor and a second, related—but unidentified—diploid ancestor. The results reveal the genome structure of the different H. marinum taxa and demonstrate the allopolyploid origin of the tetraploid forms of gussoneanum.

Keywords: Hordeum marinum, Hordeum gussoneanum, sea barley, evolutionary history, allopolyploids, FISH, ND-FISH

INTRODUCTION

The Triticeae genus Hordeum consists of about 30 species, with diploid (2n = 2x = 14), tetraploid (2n = 4x = 28) and hexaploid (2n = 6x = 42) taxa, including cultivated barley and its wild related species (Bothmer et al., 1995). The chromosome morphology, Giemsa banding patterns and meiotic behaviour of Hordeum hybrids suggest the existence of four basic diploid genomes (Bothmer et al., 1986, 1987; Linde-Laursen et al., 1992): H, Xa, Xu and I [following the nomenclature of Wang et al. (1996) and Linde-Laursen et al. (1997)]. Accordingly, molecular phylogenies cluster Hordeum species into four groups (Blattner, 2009). One of these groups, the members of which carry the Xa genome, includes the sea barleys. These are usually recognized as a single species, H. marinum, with two subspecies: marinum (2n = 2x = 14) and gussoneanum (2n = 2x = 14 and 2n = 4x = 28). The marinum and gussoneanum diploid forms coexist throughout the Mediterranean region and can be clearly distinguished by their morphology. The tetraploid cytotype of gussoneanum overlaps with the diploids only in the farthest eastern Mediterranean, extending from there towards the east into Asia (Jakob et al., 2007). There are no distinctive morphological traits that distinguish the diploid and tetraploid forms of gussoneanum, and currently they are not recognized as different taxa (Bothmer et al., 1995).

The relationships within this group of waterlogging-tolerant barleys have remained unclear. For example, controversy exists regarding the polyphyletic or monophyletic origin of this species, in part due to conflicts between phylogenetic trees derived from plastid and nuclear sequences (Blattner, 2009; Petersen et al., 2011). Another major disagreement concerns the auto- or allopolyploid origin of the tetraploids. An autopolyploid origin is supported by a number of cytogenetic studies, including the analysis of C-banded karyotypes and the meiotic behaviour of hybrids (Bothmer et al., 1989; Linde-Laursen et al., 1992), as well as the results of molecular phylogenetic studies based on the examination of chloroplast loci, geographical information and ecological data (Jakob et al., 2007). Breaking with what became a long-standing assumption of autopolyploid origin, recent molecular phylogenetic analyses using single nuclear markers seem to indicate that tetraploids originated by hybridization between a diploid form of gussoneanum and another diploid progenitor. Some studies suggest marinum to have been this second progenitor (Kakeda et al., 2009; Blattner, 2009), while others indicate an unknown extant or (probably) extinct diploid form belonging to the H. marinum complex (Komatsuda et al., 2001; Brassac et al., 2012).

To understand the genomic constitution of H. marinum, detailed cytogenetic analyses are required. The aim of the present work was to identify chromosomal markers for characterizing the karyotypes of a representative sample of H. marinum accessions of different geographical origin and covering all subspecies and cytotypes. If diploid gussoneanum and marinum were involved in the origin of tetraploid gussoneanum, their chromosomes should be present in the latter.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

Material representing all subspecies and cytotypes of the Hordeum marinum complex was obtained from the IPK Germplasm Bank (Gatersleben, Germany). Table 1 provides information on the accession numbers and places of origin of the material used.

Table 1.

List of the Hordeum marinum material studied

| Accession number | Ploidy | Country of origin | Scientific name |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCC2001 | 2x | Greece | Hordeum marinum Huds. ssp. marinum |

| GRA963 | 2x | Spain | Hordeum marinum Huds. ssp. marinum |

| GRA1078 | 2x | Italy | Hordeum marinum Huds. ssp. marinum |

| BCC2011 | 4x | Turkey | Hordeum marinum Huds. ssp. gussoneanum (Parl.) Thell. |

| BCC2012 | 2x | Bulgaria | Hordeum marinum Huds. ssp. gussoneanum (Parl.) Thell. |

| GRA1077 | 2x | Italy | Hordeum marinum Huds. ssp. gussoneanum (Parl.) Thell. |

Chromosome preparation

Root tips were obtained from seedlings and exceptionally from plants grown in pots in a greenhouse. Metaphase accumulations and chromosome preparations were performed as previously described (Cuadrado and Jouve, 2007).

Probes, labelling and in situ hybridization

Four probes were employed in FISH analyses: pTa71 and pTa794, containing 45SrDNA and 5SrDNA respectively, from Triticum aestivum, and pSc119·2 and pAs1, tandem repeat sequences obtained from Secale cereale and Triticum tauschii, respectively. The probe labelling procedures and FISH conditions were the same as those described in earlier work (de Bustos et al., 1996). Five synthetic oligonucleotides [(AG)10, (AAC)5, (AAG)5, (ACT)5 and (ATC)5], synthesized with biotin (Roche Applied Science) at both ends, were used to detect their respective simple sequence repeat (SSRs) by non-denaturing (ND) FISH, as described by Cuadrado and Jouve (2010).

Fluorescence microscopy and imaging

Slides were examined using a Zeiss Axiophot epifluorescence microscope. Biotin/Cy3-, digoxigenin/FITC- and DAPI-stained images were recorded with each filter set using a cooled CCD camera (Nikon DS). The localization of the signals relative to the DAPI staining pattern was resolved by merging images using Adobe Photoshop, employing only those functions that applied equally to all pixels.

RESULTS

Karyotype analysis of marinum

Figure 1 shows the distinctive hybridization patterns obtained with probes pTa71, pTa794, pSc119·2, pAs1, (AAC)5, (AAG)5, (ACT)5 and (ATC)5 in metaphase chromosomes of three accessions of marinum (BCC2001, GRA963 and GRA1078). In all three accessions, FISH analysis using the 45SrDNA probe (pTa71) revealed signals exclusively at the secondary constriction of the satellitized chromosome pair. Probe pTa794 revealed at least two pairs of 5SrDNA signals in all three accessions. One locus, which was sometimes resolved as a pair of two very close signals, was observed in the satellitized chromosome pair. The other pair of 5SrDNA signals was detected in a distal position on the long arm of the smaller and very metacentric chromosome pair. In addition, accession GRA963 showed an extra pair of weaker 5SrDNA signals on the long arm of another metacentric chromosome pair (Fig. 1A).

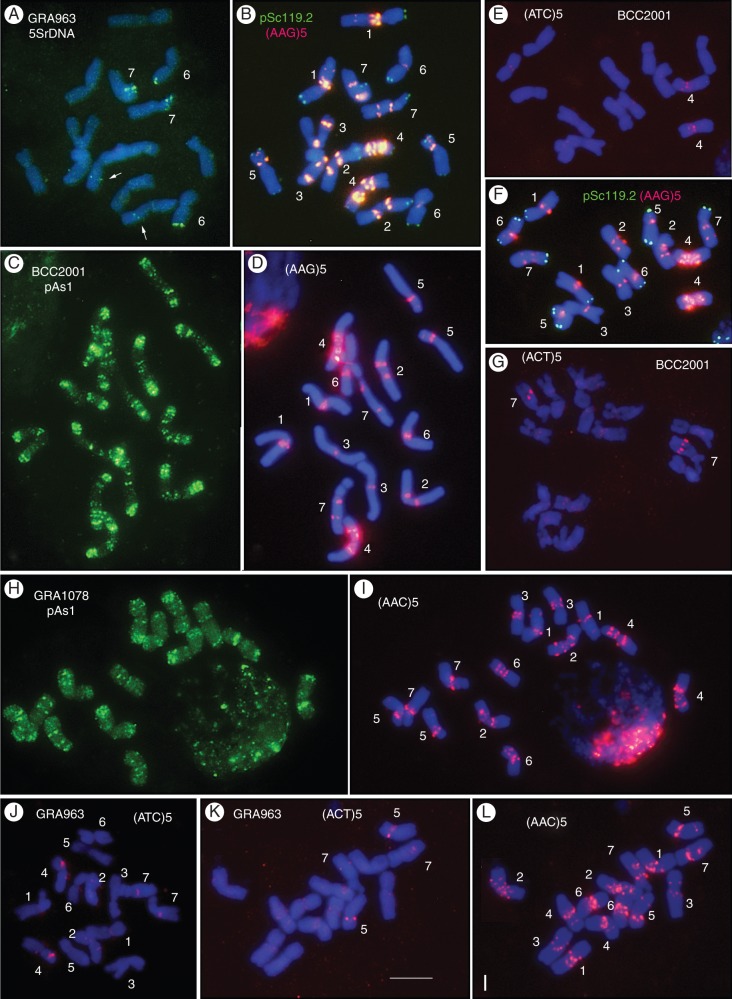

Fig. 1.

In situ hybridization with probes pTa794 (5SrDNA), pSc119·2, pAs1, (AAG)5, (AAC)5, (ACT)5 and (ATC)5 in somatic metaphases of three subspecies marinum accessions. (A, B, J–L) GRA963. (C–G) BCC2001. (H, I) GRA1078. Several panels show merged images to facilitate the visualization of the in situ signals (green or pink/red for digoxigenin- and biotin-labelled probes, respectively) with respect to DAPI blue staining. Chromosome identities are indicated in white lettering. The arrows in (A) indicate the chromosome pair showing an interstitial 5SrDNA locus. Scale bar in (K) = 10 μm.

Probe pSc119·2 showed subtelomeric signals of different intensity ranging in number from 14 on four chromosome pairs in accession BCC2001 (Fig. 1B) and six chromosome pairs in accession GRA963 (Fig. 1B) to 16 signals on five chromosome pairs in accession GRA1078. This indicates that diversity exists among the marinum accessions. The pAs1 probe revealed a rich pattern of multiple signals of different intensity on all chromosome arms, especially near the ends in the majority. Although individual chromosome identification was very difficult with this probe, greater similarities were seen in the pattern of distribution of pAs1 among accessions BCC2001 and GRA1078 than between either of these accessions and accession GRA963 (compare Fig. 1C and H).

No clusters of AG repeats were observed in marinum chromosomes, even after increasing the exposure time of the CCD camera following ND-FISH with (AG)10. The probes (ACT)5 (Fig. 1G, K) and (ATC)5 (Fig. 1E, J) revealed signals of weak intensity that were little suitable as diagnostic markers. No attempt was therefore made to characterize their in situ pattern in detail. In contrast, (AAG)5 and (AAC)5 revealed intense and rich patterns of multiple SSR signals that were particularly concentrated in the pericentromeric region (Fig. 1B, D, F, I, L).

The easy identification of the seven chromosome pairs with probe (AAG)5 allowed chromosome-by-chromosome analysis of the hybridization patterns of the remaining probes in multiple-target in situ experiments. Homologies were established among chromosomes of the different accessions. Figure 2 shows the karyotypes obtained with the six probes that gave well-defined and intense signals. Following the format used in previous descriptions, the chromosomes (1–7) were arranged in order of decreasing length with the satellitized chromosome at the end. Polymorphisms for the presence/absence and/or intensity of several probes were analysed but none was found among plants of the same accession.

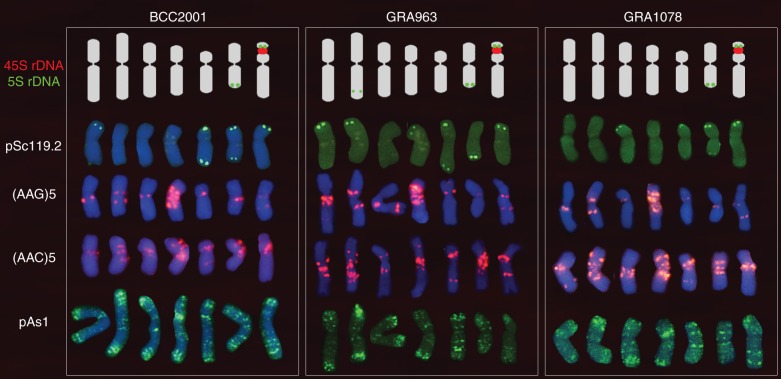

Fig. 2.

Karyotypes from each subspecies marinum accession studied, showing one chromosome of each of the seven homologous pairs. Rows from top to bottom show the distinctive hybridization patterns obtained with the 5S and 45SrDNA probes (pTa71 and pTa794), pSc119·2, (AAG)5, (AAC)5 and pAs1. Chromosomes of each karyotype were chosen from the same metaphase. Chromosomes of BCC2001 probed with pSc119·2 and (AAG)5 from the metaphase shown in Fig. 1F, and those with pAs1 from Fig. 1C. Chromosomes of GRA963 probed with pSc119·2 from the metaphase shown in Fig. 1J, and those of (AAG)5 and pAs1 from the metaphase shown in Fig. 1B. Chromosomes of GRA1078 probed with (AAC)5 and pAs1 from the metaphases shown in Fig. 1H and I respectively. Note that signals observed with the ribosomal DNA probes (clearly shown in Fig. 1A) are drawn over the ideograms to facilitate visualization of the relative size and morphology of the chromosomes.

Karyotype analysis of diploid gussoneanum

Chromosome identification and karyotype analysis of two diploid accessions of gussoneanum (BCC2012 and GRA1077) was performed by combining the physical patterns obtained with the same probes used to characterize marinum (Fig. 3). An effort was made to identify homologous chromosomes for the two diploid taxa. Karyotypes were constructed designating chromosomes from 1 to 7 on the basis of similar chromosome morphology, size and the physical mapping of the probes in marinum karyotypes (Fig. 4).

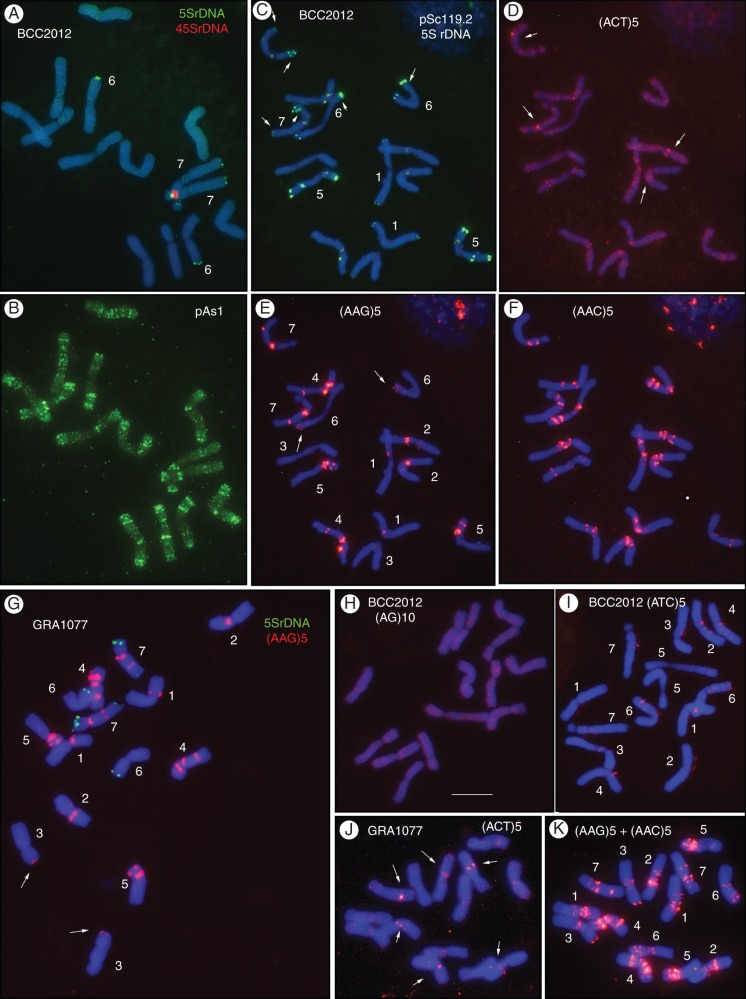

Fig. 3.

In situ hybridization with probes pTa794(5SrDNA), pTa71(45SrDNA), pSc119.2, pAs1, (AG)10, (AAG)5, (AAC)5, (ACT)5 and (ATC)5 in metaphases of two diploid accessions of subspecies gussoneanum. (A–F, H, I) BCC2012. (G, J, K) GRA1077. Some panels show merged images to facilitate visualization of in situ signals (green or pink/red for digoxigenin- and biotin-labelled probes respectively) with respect to DAPI (blue) staining. Chromosome identities are indicated in white numbers. In (C), arrows point to the 5SrDNA loci. In D and J they point to the stronger (ACT)5 signals. In E and G the arrows point to the weak polymorphic (AAG)5 signals. Scale bar in (H) = 10 μm.

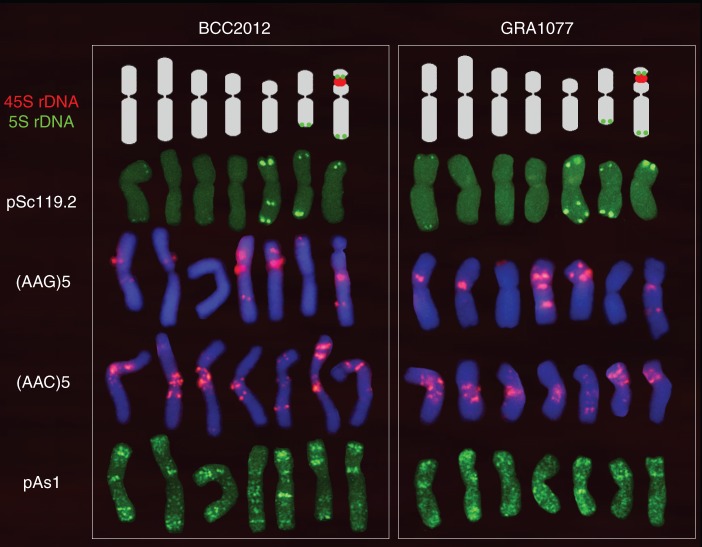

Fig. 4.

Karyotypes of the two 2x gussoneanum accessions studied showing one chromosome of each of the seven homologous pairs. Rows from top to bottom show the distinctive hybridization pattern obtained, respectively, with the 5S and 45SrDNA probes (pTa71 and pTa794), pSc119·2, (AAG)5, (AAC)5 and pAs1. Chromosomes of each karyotype were chosen from the same metaphase. Chromosomes of BCC2001 probed with pSc119·2 from the metaphase are shown in Fig. 3H, I, those probed with (AAG)5 and pAs1 from the same metaphase are shown in Fig. 3A, B and those probed with (AAC)5 are shown in Fig. 3C–F. Chromosomes of GRA1077 probed with (AAG)5 were chosen from the metaphase shown in Fig. 3G and those with pAs1 from the metaphase shown in Fig. 3J, K. Note that signals observed with the ribosomal probes (clearly shown in Fig. 3A) are drawn over the ideograms to facilitate the visualization of the relative size and morphology of chromosomes.

As in the marinum accessions, only the satellitized chromosome pair carried 45SrDNA repeats. Two 5SrDNA loci were located, one on the satellite of the satellitized chromosomes and one distal on the long arm of the smallest metacentric chromosome pair; i.e. also in the same position as in marinum. A third locus with no counterpart in marinum was located in a subterminal position on the long arm of the satellitized chromosome pair (Fig. 3A, G). As in marinum, pSc119·2 was located mainly in subtelomeric positions on four chromosome pairs. However, the most submetacentric chromosome pair of gussoneanum also carried an interstitial site on the long arm (Fig. 3C). Also as in marinum, pAs1 showed a rich pattern of multiple signals of different intensity that was similar for different chromosomes, thus making their clear identification difficult (Fig. 3B).

ND-FISH with the SSR probes (AG)10 revealed no defined clusters of AG repeats (Fig. 3H), and (ACT)5 and (ATC)5 revealed poorly defined signals of even weaker intensity than in the marinum accessions analysed (Fig. 3D, I, J). As in marinum, (AAC)5 produced a rich hybridization pattern of in situ signals. However, some chromosomes could not be easily distinguished from others with similar patterns (compare Fig. 3E, F). The physical map of (AAG)5 produced the clearest distribution pattern of diagnostic signals, allowing the identification of the seven chromosome pairs. It was thus chosen as the diagnostic probe for identifying chromosomes in multiple target experiments (Fig. 3E, G, K).

Analysis of the karyotypes (Fig. 4) revealed no differences in the pattern of distribution of the four Triticeae probes between the two diploid gussoneanum accessions. Among the SSRs analysed, only polymorphism for the presence/absence of two small subterminal clusters of AAG was observed on two chromosome pairs (compare Fig. 3E, G).

Characterization of the two subgenomes present in tetraploids

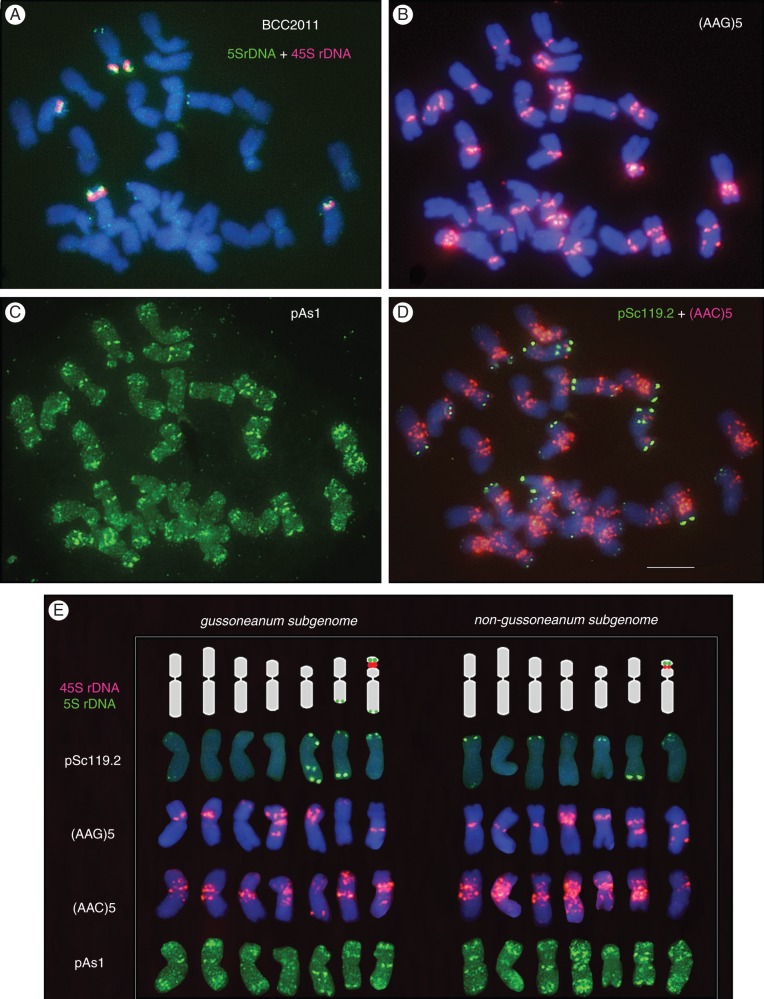

Figure 5 shows the distinctive hybridization patterns obtained with six probes in a metaphase of the tetraploid accession BCC2011 and the corresponding karyotypes.

Fig. 5.

In situ hybridization with different probes in a metaphase cell of the tetraploid accession BCC2011 of subspecies gussoneanum, and their corresponding karyotypes. (A) pTa794 (5SrDNA). The four pink signals show the satellitized chromosomes hybridized with pTa71 (45SrDNA). (B) (AAG)5. (C) pAs1. (D) pSc119·2 (green) and (AAC)5 (pink). (E) Karyotypes with chromosomes arranged in two sets of 14 chromosomes (subgenomes). Rows from top to bottom show the physical maps of the 45S and 5SrDNA probes drawn over ideograms and karyotypes revealing the distinctive hybridization patterns obtained with probes pSc119·2, (AAG)5, (AAC)5 and pAs1. Scale bar in (D) = 10 μm.

The 45SrDNA probe hybridized with two pairs of chromosomes, providing signals of different intensity. The pair carrying the stronger signals (and two 5SrDNA loci) showed visible secondary constriction in all metaphases. The second pair (with only one 5SrDNA locus) only showed visible satellites in less condensed chromosomes (Fig. 5A). In addition to the three 5SrDNA loci observed in the two pairs of satellitized chromosomes, a minor 5SrDNA locus was observed in a distal position on the long arm of a very metacentric chromosome (Fig. 5A). Subtelomeric regions of some chromosomes were identified with the pSc119·2 probe. In addition, as in diploid gussoneanum, an interstitial site was found at a similar location on the long arm of a very submetacentric chromosome. This provided a marker of choice for distinguishing this chromosome (Fig. 5D). The chromosomal distribution revealed by pAs1 was coincident with that seen for diploid H. marinum sensu lato. However, in the tetraploids, which have more chromosomes of similar morphology and in situ pattern, it was very hard to identify individual chromosomes (Fig. 5C).

As in the diploid taxa, no signal was observed with (AG)10. (ACT)5 and (ATC)5 returned very few signals, always of weak intensity, that could not be used as diagnostic landmarks (data not shown). (AAC)5 signals were found at multiple sites, especially in the pericentromeric regions of most chromosomes; again, this rendered individual chromosome identification difficult (Fig. 5D). (AAG)5, which produced the clearest pattern of signals, was chosen as the diagnostic probe for identifying chromosomes and for analysing the physical mapping of the set of probes in multiple-target in situ experiments (Fig. 5B).

In karyotype analysis (Fig. 5E), a set of 14 chromosomes showed the same size, morphology and in situ hybridization pattern as did the chromosomes of diploid gussoneanum. This set of chromosomes must belong to one of the two subgenomes present in the tetraploids, and was designated as the gussoneanum subgenome (signifying that these chromosomes have their counterpart in diploid gussoneanum accessions) (compare Figs 4 and 5E). The other group of 14 chromosomes, which provided a karyotype similar to that of diploid H. marinum sensu lato, did not correspond to any of the diploid accessions analysed here. It was therefore designated as the non-gussoneanum subgenome (compare Figs 2 and 5E).

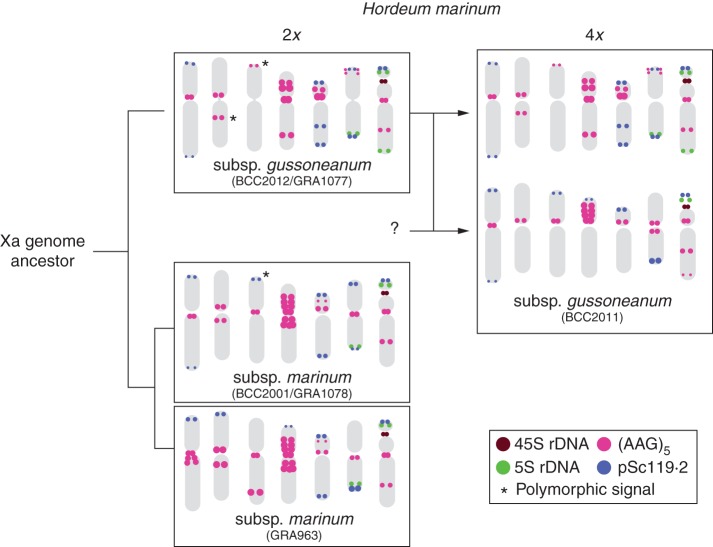

Finally, Figure 6 shows a phylogenetic tree constructed on the basis of the differences and similarities observed in the distribution pattern of probes pTa71, pTa794, pSc119·2 and (AAG)5 within and between H. marinum taxa.

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic tree including ideograms with the distribution of four repetitive sequences (see colour key) in the six accessions of Hordeum marinum examined. Asterisks indicate polymorphisms for the presence/absence of a respective sequence among accessions that share the same ideogram. Note that two ideograms were needed to include the diversity found within marinum accessions.

DISCUSSION

Chromosomal identification and karyotype analysis

This is the first report to identify all H. marinum chromosomes in all its cytotypes. The chromosomes of each taxon, which are not identifiable either by their morphology or by their C-banding pattern, were characterized in detail by multiple-target in situ hybridization analysis. As indicated by other authors, FISH performed with four Triticeae-specific repetitive DNA sequences (pTa71, pTa794, pSc119·2 and pAs1) allowed the identification of a few chromosome pairs of H. marinum, but was insufficient for the reliable identification of any more (de Bustos et al., 1996; Taketa et al., 1999, 2000). However, several SSRs were found to provide useful diagnostic probes for chromosomal identification. Indeed, the use of (AAG)5 in combination with the morphology of DAPI-stained chromosomes was enough to distinguish all individual H. marinum chromosomes easily. The usefulness of SSR sequences as chromosomal markers revealed by ND-FISH in different species, including several members of the tribe Triticeae, has been reported previously by our group (Cuadrado et al., 2008; Cuadrado and Jouve, 2010, 2011). With the exception of (AG)10, (ACT)5 and (ATC)5 (which were ineffective as chromosome markers), the probes used in the present work provided a saturated physical map of H. marinum with a rich set of landmarks distributed across all chromosome arms.

The first step in inferring relationships between species is the discrimination of homology among the chromosomes of related taxa. The distribution pattern of the set of repetitive DNA sequences, plus chromosome morphology, helped establish putative homologies among chromosomes assigned the same number in the subspecies of H. marinum. The homologous relationship between chromosome pairs 6 and 7 was easily established using the rDNA loci as landmarks. Homologies among marinum and gussoneanum for chromosomes 2 (the most metacentric), 4 (the most intensely hybridized with [AAG])5 and 5 (the most submetacentric and showing interstitial pSc119·2 signals in gussoneanum) were established on the basis of similarity in morphology and (AAG)5 pattern. However, the similarities between chromosomes 1 and 3 of both subspecies make it difficult to identify truly homologous relationships. In any event, the nomenclature used to designate chromosomes—following previous karyotype descriptions with chromosomes arranged in order of decreasing length and with the satellitized chromosome at the end—need not be interpreted as a system of Triticeae homoeologies, but simply as a way of identifying chromosomes. In future, the identities of H. marinum chromosomes should adopt the system of homoeologies now well established for other members of the tribe Triticeae, such as barley and wheat. For example, the satellitized chromosome 7 carrying the 5SrDNA locus in its satellite must be at least in part homoeologous to chromosome 5 of the Triticeae group (i.e. 5H of barley and 5A, 5B and 5D of wheat) and should be designated as chromosome 5Xa (Linde-Laursen, 1997). Since H. marinum chromosomes might be identifiable in bivalent configuration, true homologies among marinum and gussoneanum could be established by analysing (for example) the pollen mother cells of their hybrids in metaphase I. Moreover, the analysis of meiotic pairing in hybrids of H. marinum × H. vulgare should allow homoeologous relationships to be established between Triticeae species; this has been successful in identifying homoeologous chromosomes in H. vulgare × H. bulbosum hybrids (Pickering et al., 2006).

Origin of polyploids in H. marinum

Genomic in situ hybridization (GISH) provides a useful cytogenetic means of identifying the parental origin of chromosomes present in hybrids and polyploids (Cuadrado et al., 2004; Taketa et al., 2009; Chester et al., 2010). However, GISH performed with total genomic DNA from diploid subspecies of H. marinum, irrespective of the blocking agent/probe ratios tested, did not differentiate the chromosomes of the tetraploid accession analysed (data not shown). However, in this accession a set of 14 chromosomes of the same size, morphology and hybridization pattern as those of diploid gussoneanum chromosomes was identified. This confirms the putative involvement of gussoneanum as a diploid ancestor of H. marinum tetraploids and demonstrates the latter's allopolyploid origin. The diploid forms of gussoneanum would be the maternal donor, as suggested by molecular phylogenies based on chloroplast DNA (Petersen and Seberg, 2003; Jakob et al., 2007).

The overall resemblance of the two subgenomes present in accession BCC2011, different from any other Hordeum genomes (de Bustos et al., 1996; A. Cuadrado, unpubl. res.), indicates that the origin of the non-gussoneanum subgenome also lies in a species of H. marinum. Hence the two subgenomes present in polyploids are segmental in nature. It remains unknown whether marinum was the second genome donor. However, taking into account the diversity of karyotypes detected within marinum, it cannot be ruled out that the non-gussoneanum genome will be found in other marinum ecotypes. It may also be that related forms of the diploid accessions analysed were parentals and underwent significant genomic and chromosomal changes during the generations coming soon after polyploidization. For example, changes in the number of rDNA sites to more or less the sum of those possessed by their ancestors played a major role in Triticeae evolution (Ozkan and Feldman, 2009; Han et al., 2005). Although no alteration in the morphology or stability of repetitive DNA clusters in the chromosomes donated by gussoneanum appears to have occurred after the polyploidization process, presumably as a consequence of the relatively recent formation of allotetraploids, it cannot be ruled out that the non-gussoneanum subgenome was subject to different trends during the adaptive process following interspecific hybridization. In summary, the second genome remains unknown, although the physical map of the sequences here investigated suggests the donor of the non-gussoneanum genome was a form closer to marinum than to gussoneanum.

Phylogenetic relationships within H. marinum

Although the results of this work distinguish the chromosomes of H. marinum, their size and morphology and the distribution patterns of the chosen probes were similar in those of all taxa and cytotypes examined. This agrees with the monophyletic origin of this complex revealed by molecular studies of single nuclear genes and repeated DNA polymorphisms, which position all H. marinum taxa in one highly supported clade and confirm that all taxa and cytotypes share the same basic Xa genome (Svitashev et al., 1994; Marillia and Scoles, 1996; de Bustos et al., 2002; Petersen and Seberg, 2003). However, the differences found in the distribution of several probes, for example the presence in gussoneanum of a distal loci 5SrDNA in the long arm of the satellitized chromosome or the interstitial pSc119·2 and (AAG)5 signals on chromosome 5, suggest substantial cytogenetic divergence between marinum and 2x gussoneanum. These differences may have appeared after the separation of both subspecies from their ancient progenitor about 2 million years ago (Blattner, 2004, 2006).

At the intraspecific level, the conserved distribution patterns of the 2x gussoneanum accessions contrast with the diversity observed for the accessions of marinum. This agrees with the high genetic variability of the DNA sequences revealed within marinum. Indeed, on the basis of molecular evidence, different authors have suggested the existence of two geographically separated marinum forms: an Iberian group from the mainland of Spain and Portugal, and a non-Iberian group in the Central Mediterranean region (Komatsuda et al., 2001; Jakob et al., 2007). In the present study, although polymorphic signals were detected between accessions BCC2001 and GRA1078 from Greece and Italy, respectively, the physical maps for each probe were very similar, but significantly different from that recorded for the Spanish accession GRA963 (compare karyotypes in Fig. 2 or ideograms in Fig. 6). However, only three marinum accessions were used in this study; more must be examined to support the separation of subspecies marinum into two or more geographically differentiated cytotypes. Nevertheless, the present results point to the existence of substantial cytogenetic differences within marinum, suggesting a less close genomic relationship between the populations of this subspecies than that which exists within the subspecies gussoneanum.

Evolutionary trends of repetitive DNA sequences during H. marinum speciation

In contrast with the conserved pattern of distribution of 45SrDNA among H. marinum taxa, variation in the pattern of distribution of the remaining repetitive sequences may have been due to independent insertion events, amplification and/or removal of copies of the repetitive sequences in particular lineages. Although it cannot be ruled out that, for example, translocations or inversions have contributed to the different distributions of repetitive DNA sequences in H. marinum taxa, chromosomal rearrangement may not be the main cause of karyotypic differences. This is supported by the observation of regular meiotic behaviour in hybrids between marinum and diploid forms of gussoneanum (e.g. absence of univalents and multivalents) (Linde-Laursen and Bothmer, 2012).

With respect to 5SrDNA, the common loci present in the diploid forms (chromosomes 6 and 7) were probably present in their Xa genome common ancestor. The new locus present on the long arm of chromosome 7 in gussoneanum may have been acquired after the separation of this subspecies. It is noteworthy that no other diploid Hordeum species has a 5SrDNA locus on the long arm of its satellitized chromosomes (de Bustos et al., 1996; Taketa et al., 1999), which supports the idea that this locus is a new acquisition in the gussoneanum lineage. Other independent events of amplification of 5SrDNA repeats could be the origin of the third locus observed in the marinum accession GRA963 and in the Spanish material studied earlier by de Bustos et al. (1996). It is reasonable to assume that this could be due to the amplification of pre-existing interstitial 5SrDNA sequences in an ancient form present in the Iberian Peninsula after the geographical isolation of marinum populations in glacial refuges during the Pleistocene (Jakob et al., 2007).

The intraspecific polymorphisms affecting the number of chromosome ends carrying pSc119·2, as observed here within marinum, has been reported in other species, including rye, the species from which the probe comes (Cuadrado et al., 1995; Schneider et al., 2003). The differences in the distribution of probe pSc119·2 among marinum and gussoneanum, exclusively observed in a subtelomeric position in marinum and other Hordeum species (Taketa et al., 2000; de Bustos et al., 1996) but also present in an interstitial location in a chromosome pair in gussoneanum, suggests that this highly repetitive sequence could have supported events of interstitialization. A similar tendency of pSc119·2 to spread towards new interstitial sites occurred during the diversification of the most primitive form of the genus Secale towards the most advanced taxa (Jones and Flavell, 1982; Cuadrado and Jouve, 2002).

(AAG)5 revealed the highest chromosomal variation both within and between taxa. This suggests that this sequence is more predisposed to being amplified or deleted as a consequence of independent events in different lineages. This agrees with the extensive intra- and interspecific polymorphism observed in other Triticeae species; this SSR is very abundant in barley and wheat but restricted to a few locations in H. bulbosum or rye chromosomes (Pedersen et al., 1996; Pedersen and Langridge, 1997; Cuadrado et al., 2008; Carmona et al., 2013). It is reasonable to assume that the clusters exclusively observed in the marinum accession GRA963 are the result of the differential amplification of AAG motifs in this material. However, the evolutionary trends (amplification or deletion) for the polymorphic AAG clusters observed between marinum and the diploid forms of gussoneanum cannot be deduced. Independent amplification or deletion events in particular chromosome locations after both subspecies diverged from the common ancestor might be responsible for the differences observed, and the occurrence of both has been demonstrated during the process of speciation in related species. For example, during the speciation of the genus Secale, clusters of AAG were amplified in S. silvestre and deleted in S. vavilovii with respect to S. cereale (Cuadrado and Jouve, 2002).

The physical maps for pAs1 and (AAC)5 have not been included in the phylogenetic tree in Fig. 6 (although their patterns are readily distinguishable in Figs 2, 3 and 5B and indicate that the same general conclusions can be made as those drawn from Fig. 6). It could be that independent mechanisms of amplification or reduction of the number of copies of each repeat sequence in different lineages occurred after they split from a common ancestor. Assuming a monophyletic origin for the diploid cytotypes of H. marinum, it is difficult to explain why populations of marinum with different origins show greater karyotype variation than populations of gussoneanum of similar geographical origin. Based on the highly significant differences in the DNA content between marinum and 2x gussoneanum (9·10 pg in marinum and 10·41 pg in gussoneanum), Jakob et al. (2004) suggested that significant genome size increases occurred in the lineage leading to gussoneanum. Although individual probes hybridized to more or fewer chromosomal locations in marinum or gussoneanum, when considering the sequences as whole it is hard to see any clear differences between them in terms of the total amounts of these repetitive DNA sequences.

Taxonomy of the H. marinum complex

The taxonomic treatment of marinum and gussoneanum as subspecies is generally accepted. However, their clear morphological differences and the absence of gene flow between both diploid taxa have led several authors to regard them as separate species, i.e. H. marinum and H. gussoneanum (Jorgensen, 1986; Jaaska, 1994; Jakob et al., 2007; Blattner, 2009). Another problem with the complex is the taxonomic status of the different cytological forms of gussoneanum. Assuming the existence of cryptic taxa for the allotetraploids, Jaaska (1994) proposed the tetraploid forms of gussoneanum be treated as H. caudate Jaaska. We agree that this taxon should be considered a separate species based on its reproductive isolation after polyploidization, its meiotic behaviour (involving the almost exclusive formation of trivalents) and the low fertility observed in hybrids with diploid forms (Bothmer et al., 1989).

In conclusion, this study reveals the origin of the polyploid forms of H. marinum and highlights their genome structure and evolution. Moreover, the results of detailed karyotype analyses provide the basis for demonstrating the implication of H. marinum taxa in the origin of polyploid H. secalinum, H. capense and H. brachyantherum (Petersen and Seberg, 2004; Komatsuda et al., 2009; Wang and Sun, 2011). A practical application of the present findings is the detection of individual H. marinum chromosomes in breeding lines, for example the material obtained in breeding programmes after the hybridization of wheat with this interesting and complex salt- and waterlogging-tolerant group (Jiang and Liu, 1987; Garthwaite et al., 2005). Certainly, the taxonomic treatment of tetraploids based exclusively on morphological criteria would appear to be questionable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded by a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (AGL2009-10373 and AGL2012-34052). The authors thank Adrian Burton for linguistic assistance.

LITERATURE CITED

- Blattner FR. Phylogenetic analysis of Hordeum (Poaceae) as inferred by nuclear rDNA ITS sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2004;33:289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattner FR. Multiple intercontinental dispersals shaped the distribution area of Hordeum (Poaceae) New Phytologist. 2006;169:603–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattner FR. Progress in phylogenetic analysis and a new infrageneric classification of the barley genus Hordeum (Poaceae: Triticeae) Breeding Science. 2009;59:471–480. [Google Scholar]

- Bothmer RV, Flink J, Landström T. Meiosis in interspecific Hordeum hybrids. I. Diploid combinations. Canadian Journal of Genetics and Cytology. 1986;28:525–535. [Google Scholar]

- Bothmer RV, Flink J, Landström T. Meiosis in interspecific Hordeum hybrids. II. Triploid combinations. Evolutionary Trends in Plants. 1987;1:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bothmer RV, Flink J, Jacobsen N, Jorgensen RB. Variation and differentiation in Hordeum marinum (Poaceae) Nordic Journal of Botany. 1989;9:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bothmer RV, Jacobsen N, Baden C, Jorgensen RB., Linde-Laursen . An ecogeographical study of the genus Hordeum. 2nd edn. Rome: IPGRI, 129; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Brassac J, Jakob SS, Blattner FR. Progenitor-derivative relationships of Hordeum polyploids (Poaceae, Triticeae) inferred from sequences of TOPO6, a nuclear low-copy gene region. PLoS ONE. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033808. pe33808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona A, Friero E, de Bustos A, Jouve N, Cuadrado A. Cytogenetic diversity of SSR motifs within and between Hordeum species carrying the H genome: H. vulgare L. and H. bulbosum L. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2013;126:949–961. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-2028-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester M, Leitch AR, Soltis P, Soltis DE. Review of the application of modern cytogenetic methods (FISH/GISH) to the study of reticulation (polyploidy/hybridisation) Genes. 2010;1:166–192. doi: 10.3390/genes1010166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado A, Jouve N. Evolutionary trends of different repetitive DNA sequences during speciation in genus Secale. Journal of Heredity. 2002;93:339–345. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.5.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado A, Jouve N. The non-random distribution of long clusters of all possible classes of tri-nucleotide repeats in barley chromosomes. Chromosome Research. 2007;15:711–720. doi: 10.1007/s10577-007-1156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado N, Jouve N. Chromosomal detection of simple sequence repeats (SSRs) using nondenaturing FISH (ND-FISH) Chromosoma. 2010;19:495–503. doi: 10.1007/s00412-010-0273-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado A, Jouve N. Novel simple sequence repeats (SSRs) detected by ND-FISH in heterochromatin of Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:205. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado A, Ceoloni C, Jouve N. Variation in highly repetitive DNA composition of heterochromatin in rye studied by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Genome. 1995;38:101–1069. doi: 10.1139/g95-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado A, Acevedo R, Moreno Díaz de la Espina S, Jouve N, de la Torre C. Genome remodelling in three modern S. officinarum×S. spontaneum sugarcane cultivars. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2004;55:847–854. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado A, Cardoso M, Jouve N. Physical organisation of simple sequence repeats (SSRs) in Triticeae: structural, functional and evolutionary implications. Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 2008;120:210–219. doi: 10.1159/000121069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bustos A, Cuadrado A, Soler C, Jouve N. Physical mapping of repetitive DNA sequences and 5S and 18S-26S rDNA in five wild species of the genus Hordeum. Chromosome Research. 1996;4:491–499. doi: 10.1007/BF02261776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bustos A, Loarce Y, Jouve N. Species relationships between antifungal chitinase and nuclear rDNA (internal transcribed spacer) sequences in the genus Hordeum. Genome. 2002;45:339–347. doi: 10.1139/g01-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garthwaite AJ, Bothmer RV, Colmer TD. Salt tolerance in wild Hordeum species associated with restricted entry of Na+ and Cl- into the shoots. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2005;56:2365–2378. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han F, Fedak G, Guo W, Liu B. Rapid and repeatable elimination of a parental genome-specific DNA repeat (pGc1R-1a) in newly synthesized wheat allopolyploids. Genetics. 2005;147:1381–1383. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.039263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaaska V. Isoenzyme evidence on the systematics of Hordeum section Marina (Poaceae) Plant Systematics and Evolution. 1994;191:213–226. [Google Scholar]

- Jakob SS, Meister A, Battner FR. The considerable genome size variation of Hordeum species (Poaceae) is linked to phylogeny, life form, ecology, and speciation rates. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2004;21:860–869. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob SS, Ihlow A, Blattner FR. Combined ecological niche modelling and molecular phylogeography revealed the evolutionary history of Hordeum marinum (Poaceae)—niche differentiation, loss of genetic diversity, and speciation in Mediterranean Quaternary refugia. Molecular Ecology. 2007;16:1713–1727. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Liu D. New Hordeum-Triticum hybrids. Cereal Research Communications. 1987;15:95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Jones JDG, Flavell RG. The structure, amount and chromosomal localization of defined repeated DNA sequences in species of the genus Secale. Chromosoma. 1982;86:613–641. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen RB. Relationships in the barley genus (Hordeum): an electrophoretic examination of proteins. Hereditas. 1986;104:273–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kakeda K, Taketa S, Komatsuda T. Molecular phylogeny of the genus Hordeum using thioredoxin-like gene sequences. Breeding Science. 2009;59:595–601. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsuda T, Salomon B, Bryngelsson T, Bothmer RV. Phylogenetic analysis of Hordeum marinum Huds. based on nucleotide sequences linked to the vrs1 locus. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 2001;227:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsuda T, Salomon B, Bothmer RV. Evolutionary process of Hordeum brachyantherum 6x and related tetraploid species revealed by nuclear DNA sequences. Breeding Science. 2009;59:611–616. [Google Scholar]

- Linde-Laursen I, Bothmer RV. Connection between rod bivalents and incomplete meiotic association at NORs in Hordeum marinum Huds. Hereditas. 2012;149:139–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.2012.02253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linde-Laursen I, Bothmer RV, Jacobsen N. Relationships in the genus Hordeum: Giemsa C-banded karyotypes. Hereditas. 1992;116:111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Linde-Laursen I, Heslop-Harrison JS, Shepherd KW, Taketa S. The barley genome and its relationship with the wheat genomes. A survey with and internationally agreed recommendation for barley chromosome nomenclature. Hereditas. 1997;123:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Marillia EF, Scoles GJ. The use of RAPD markers in Hordeum phylogeny. Genome. 1996;39:646–654. doi: 10.1139/g96-082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan H, Feldman M. Rapid cytological diploidization in newly formed allopolyploids of the wheat (Aegilops-Triticum) group. Genome. 2009;52:926–934. doi: 10.1139/g09-067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen C, Langridge P. Identification of the entire chromosome complement of bread wheat by two-colour FISH. Genome. 1997;40:589–593. doi: 10.1139/g97-077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen C, Rasmussen SK, Linde-Laursen I. Genome identification in cultivated barley and related species of the Triticeae (Poaceae) by in situ hybridization with the GAA-satellite sequence. Genome. 1996;39:93–104. doi: 10.1139/g96-013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen G, Seberg O. Phylogenetic analyses of the diploid species of Hordeum (Poaceae) and a revised classification of the genus. Systematic Botany. 2003;28:293–306. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen G, Seberg O. On the origin of the tetraploid species Hordeum capense and H. secalinum (Poaceae) Systematic Botany. 2004;20:862–873. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen G, Aagensen L, Seberg O, Larsen IH. When is enough, enough in phylogenetics? A case in point from Hordeum (Poaceae) Cladistics. 2011;27:428–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2011.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering R, Klatte S, Butler RC. Identification of all chromosome arms and their involvement in meiotic homoeologous associations at metaphase I in 2 Hordeum vulgare L.×Hordeum bulbosum L. hybrids. Genome. (2006);49:73–78. doi: 10.1139/g05-071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, Linc G, Molnár-Láng M, Graner A. Fluorescence in situ hybridization polymorphism using two repetitive DNA clones in different cultivars of wheat. Plant Breeding. 2003;122:396–400. [Google Scholar]

- Svitashev S, Bryngelsson T, Vershinin A, Pedersen C, Säll T, Bothmer RV. Phylogenetic analysis of the genus Hordeum using repetitive DNA sequences. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1994;89:801–810. doi: 10.1007/BF00224500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taketa S, Harrison GE, Heslop-Harrison JS. Comparative physical mapping of the 5S and 18S-25SrDNA in nine wild Hordeum species and cytotypes. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1999;98:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Taketa S, Ando H, Takeda K, Harrison GE, Heslop-Harrison JS. The distribution, organization and evolution of two abundant and widespread repetitive DNA sequences in the genus Hordeum. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2000;100:169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Taketa S, Nakauchi Y, Bothmer RV. Phylogeny of two tetraploid Hordeum species, H. secalinum and H. capense inferred from physical mapping of 5S and 18S.25SrDNA. Breeding Science. 2009;59:589–594. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Sun G. Molecular phylogeny and reticulate origins of several American polyploid Hordeum species. Canadian Journal of Botany. 2011;89:405–415. [Google Scholar]

- Wang RRC, Bothmer RV, Dvorak J, Fedak G, Linde-Laursen I, Muratmatsu M. Genome symbols in the Triticeae. In: Wang RRC, Jensen KB, Jaussi C, editors. Proceedings of the 2nd International Triticeae Symposium. Logan, UT: Utah State University; 1996. pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]