Abstract

Retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas are uncommon tumors, with approximately 300 documented cases in the literature. Management necessitates complete surgical resection in order to offer patients a chance at long-term cure. Resection often presents a challenge as these tumors are often large, involving adjacent structures, and may require reconstruction of the inferior vena cava (IVC). In this article, we will present background information on retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas and the technical aspects of surgical resection and vascular reconstructive options of the IVC.

Keywords: Retroperitoneal leiomyosarcoma, Inferior vena cava, Sarcoma, Surgery

Case Report

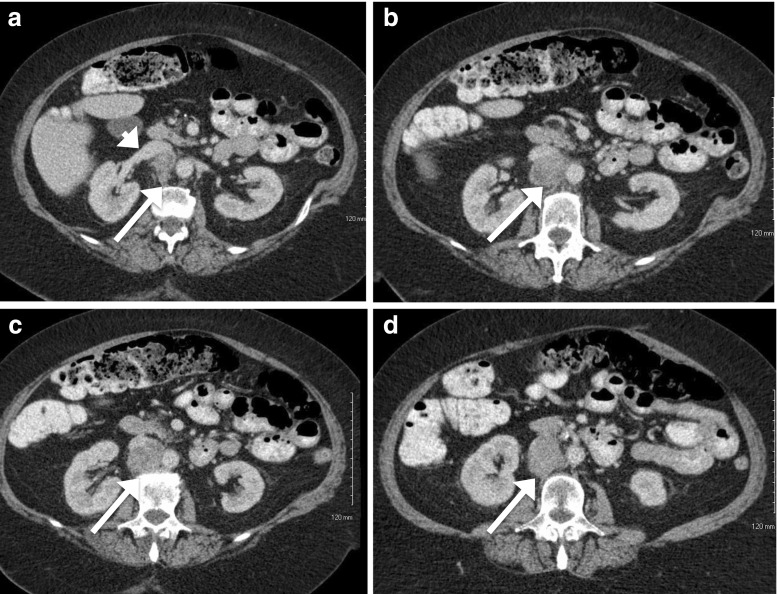

The patient is a 62-year-old female involved in a motor vehicle accident. Upon presentation, she complained of back pain and underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrating an incidental finding of a 5-cm retroperitoneal soft tissue mass adjacent to the aorta and extending inferiorly from the right renal artery and vein. Further workup with contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained demonstrating a 4.6 cm × 4.1 cm × 4.4 cm mass inferior to the right renal vein and posterior to the inferior vena cava with no other associated abnormalities (Fig. 1). She then underwent image-guided core needle biopsy of this lesion with pathology demonstrating a spindle cell neoplasm consistent with leiomyosarcoma.

Fig. 1.

CT images of 4.6 × 4.1 × 4.4 cm leiomyosarcoma. a Image showing the right renal vein entering the IVC (white arrowhead). b, c, d Images showing the extent of IVC invasion (white arrows)

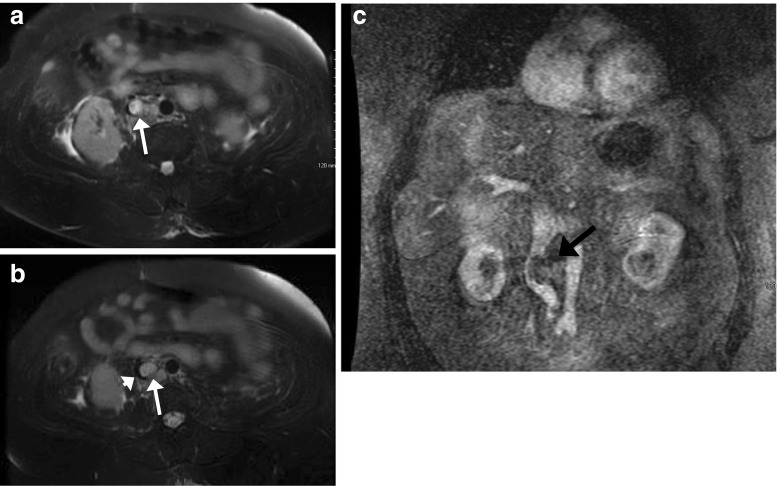

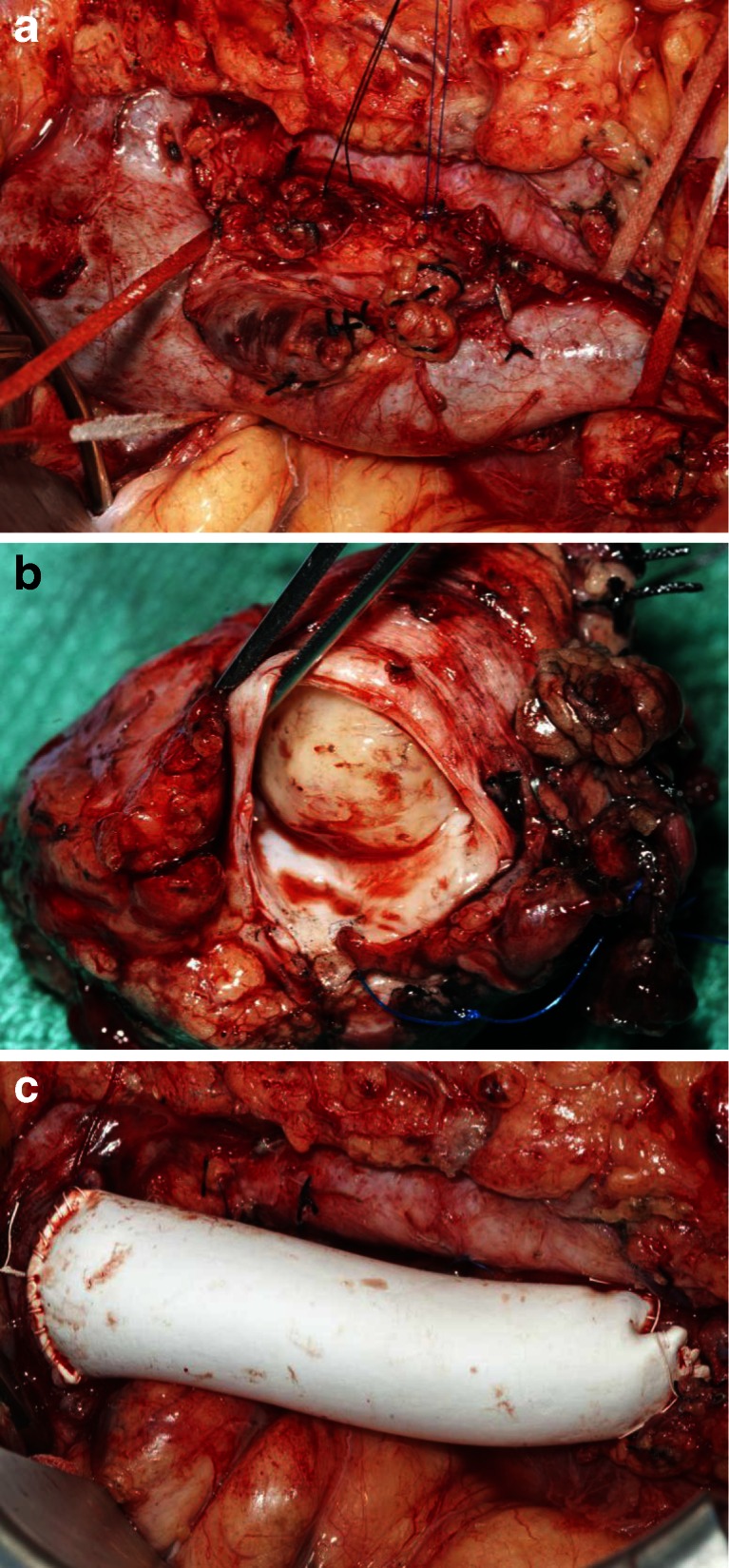

Due to the proximity of the lesion to the aorta and renal vasculature, she underwent neoadjuvant radiation therapy to a dose of 50 Gy with a boost up to 55 Gy. An MRI of the abdomen and pelvis performed 4 weeks after radiotherapy was completed and redemonstrated the mass, now measuring 5.5 cm × 3.3 cm × 3.4 cm and extending from just below the left renal vein to 3 cm above the confluence of the common iliac veins without invasion of the aorta (Fig. 2). She then underwent resection of the mass, which necessitated complete resection of the inferior vena cava (IVC), with reconstruction utilizing a Gore-Tex graft (W.L. Gore & Associates Inc., Flagstaff, AZ; Fig. 3). Final pathology demonstrated >75 % of tumor cytoreduction and closest margin of 1 mm. Postoperatively, she was placed on a heparin drip and discharged on lifelong warfarin and aspirin per our vascular surgery protocol. At her 12-month follow-up appointment, she was doing well with a patent graft. Unfortunately, follow-up imaging obtained 14 months after surgery revealed evidence of extensive pulmonary metastases, not amenable to resection, and partial thrombosis of her graft.

Fig. 2.

T2-weighted MRI performed after neoadjuvant radiation. a, b A 5.5 cm × 3.3 cm × 3.4 cm infrarenal mass, T2 bright, centered within the posteromedial wall of the inferior vena cava (white arrows) without invasion of the aorta. Note narrowing of IVC lumen (black crescentic lumen, white arrowhead). c Coronal view demonstrating deviation of the IVC (black arrow)

Fig. 3.

a Intraoperative picture of IVC leiomyosarcoma with the patient's head on the left and the feet on the right. b Resected leiomyosarcoma. c Reconstructed IVC with Gore-Tex graft

Introduction

Retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas are rare tumors of the mesenchymal cells, most often arising from the IVC.1 , 2 These tumors are estimated to account for approximately 0.5 % of all sarcomas affecting adults and less than 1 in 100,000 of all malignancies.1 , 3

Retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas of the IVC are slow growing, and at the time of diagnosis, they are often very large, making curative resection difficult.1 , 3 In several studies, the mean tumor diameter on final pathology was >10 cm.1 – 5 Due to their extensive tumor growth, some patients will present with flank masses; however, most have nonspecific symptoms, and the tumor is discovered incidentally. Those who do have symptoms most commonly present with right-sided abdominal or flank pain.6 Patients may also present with lower extremity edema, which is more often secondary to deep vein thrombosis as opposed to complete or partial occlusion of the IVC by the tumor or thrombus.3 , 7 , 8 Lower extremity edema due to the latter is seen in ≤30 % of patients on presentation, as the slow growth of these tumors allows for development of venous collaterals.3 There have also been documented cases of patients presenting with Budd–Chiari syndrome due to superiorly extending tumor resulting in occlusion of the hepatic veins. In addition, patients can present with cardiac arrhythmias if the tumor extends into the right atrium.2 , 9 , 10

Currently, complete surgical resection offers the only possibility for long-term cure. Most retrospective studies demonstrate 5-year survival rates ranging from 33 to 68 % for patients undergoing surgical resection.2 , 3 , 7 , 11 These studies emphasize the need for radical resection, including associated viscera, such as the liver, small and large intestines, kidney, and adrenal gland.2 , 5 , 10 – 13 Macroscopic residual disease, involvement of the upper segment of the IVC above the hepatic veins, significant intraluminal growth of tumor, and liver compromise are associated with a poorer prognosis.2 Palliative resections are occasionally performed for symptom control, but they have not been shown to improve survival.1

Diagnosis and Evaluation

Diagnosis is often made with imaging studies. Occasionally, these tumors can be seen on ultrasound of the right upper quadrant evaluating for gallbladder disease. On ultrasound, these tumors appear to be heterogeneous as areas of necrosis are hypoechoic. Doppler flow studies can be used to evaluate the extent of IVC obstruction and to evaluate for thrombosis of the hepatic and renal veins.10

Retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas are more often diagnosed on CT or MRI. On CT imaging, the tumors typically appear as heterogeneous masses with enhancement of the periphery of the tumor.14 Areas of hemorrhage and necrosis may be noted within the mass on CT. On T1-weighted MRI, leiomyosarcomas have low signal intensity, while on T2-weighted imaging, they demonstrate high signal intensity.14

The goals of preoperative radiologic assessment are to evaluate the primary tumor and local invasion, delineate the extent of IVC thrombus, identify invasion of the wall of the IVC, and identify pulmonary emboli and distant metastases. In the largest study to date evaluating preoperative imaging of leiomyosarcomas of the IVC, CT scans were the imaging modality of choice for evaluation of tumor location within the IVC as well as distant metastases.14 MRI is also commonly utilized to evaluate the extent of tumor invasion and to assess for resectability.14 MRI and CT have both been found to provide excellent accuracy for detecting tumor thrombus.15

Operative Procedure

Leiomyosarcomas of the IVC are categorized by their anatomic relation to adjacent structures. The upper segment (level 3) of the IVC extends from the right atrium to the hepatic veins, the middle segment (level 2) extends below the hepatic veins to the insertion of the renal veins, and the lower segment (level 1) encompasses the portion of the IVC below the renal veins to its origin. Specific intraoperative approaches are needed to safely resect tumors at each location.

The approach to surgical management of the vena cava is dictated not only by the level of involvement but also by the extent of tumor burden and by the presence or absence of robust venous collateral networks. Surgical options include (1) partial resection and primary cavoplasty with bovine pericardium or other patch venoplasty, (2) complete resection with interposition graft placement, and (3) ligation.16 The first option can be undertaken with resection of <75 % circumference of the vena cava, whereas complete resection and placement of an interposition graft must be performed if >75 % of the IVC is involved. In a recently reported series, IVC resection with ligation was performed in 26 % of patients when well-developed venous collaterals were noted intraoperatively.16 Simple ligation of the IVC cannot be performed if the tumor invades the upper IVC but can safely be performed on levels 2 and 3.17 This is most likely to be possible without resultant lower extremity edema when the IVC has been occluded by tumor and therefore extensive collaterals are present.

In most cases, the patient can be positioned supine for an abdominal incision, but if the patient is to have a thoracoabdominal incision for upper IVC involvement, then the left lateral decubitus position is preferred. Preoperative antibiotics should be administered 1 h prior to incision. Pneumatic compression devices or graded compression stockings are then placed on the patient's calves for the duration of the operation, and 5,000 units of subcutaneous heparin is given prior to incision as an added preventative modality to reduce the risk of venous thrombosis. A Foley catheter is also placed to monitor urine output throughout the procedure. A central venous catheter and arterial line should also be placed for intraoperative monitoring and resuscitation of the patient. Once the patient is prepped and draped, a midline abdominal incision is preferred. Once the abdominal cavity has been entered, the liver, omentum, and peritoneal surfaces should be evaluated for metastases. Intraoperative frozen section evaluation should be obtained of all suspicious lesions as metastatic disease would preclude a curative resection.

To access the upper segment of the IVC, a thoracoabdominal incision can be utilized, although some authors describe advantages to combining laparotomy with sternotomy.6 The ligamentum teres and falciform ligament of the liver are then dissected to the level of the IVC. The liver can then be retracted caudally for distal control of the suprahepatic IVC. If the tumor extends into the right atria, then placing the patient on cardiopulmonary bypass may be necessary prior to resection.

In order to gain access to the middle and lower IVC, the ascending colon is mobilized medially and an extensive Cattell–Braasch maneuver is performed. This will allow for adequate exposure of the lower IVC. To further expose the middle IVC directly behind the liver, the right liver lobe is mobilized superiorly and medially by dividing the right triangular ligament. Once the tumor is visualized, the tissue surrounding it can be dissected free of adjacent structures. If the tumor is invading local structures such as the liver, right kidney, adrenal gland, or bowel, then these structures need to be mobilized prior to exposing the IVC. Adequate exposure of the IVC includes space for proximal and distal control as well as control of the renal veins and renal artery, particularly the right renal artery. If the right renal vein is clamped at any point during the operation, the corresponding artery can be clamped to avoid renal congestion. Distally, the right iliac artery is mobilized and retracted medially and caudally to allow safe and precise control of the left iliac vein. This is particularly difficult in irradiated fields or for large tumors.

While exposing the IVC in its entirety, the surgeon should attempt to preserve venous collaterals until a definitive decision is made regarding the extent of resection and type of reconstruction to be performed. It is at this time, intraoperatively, that the final decision is made regarding the need for and approach to IVC reconstruction. If the IVC is occluded and collaterals are well developed, resection with ligation is undertaken. If the IVC demonstrates residual luminal patency and if minimal collateral networks are present, resection and reconstruction should be performed.

After complete mobilization of tumor with adjacent involved organs, the patient is then systemically heparinized to an ACT > 250 s during flow interruption. Satinzky clamps are then placed at the proximal and distal aspects of the segment to be resected. Satinzky clamps are preferred as they allow precise placement and are not bulky. The tumor is then dissected and removed from proximal to distal. Meticulous control of multiple large lumbar veins is critical to minimize blood loss. This can be achieved by clipping or simply ligating these vessels via a posterior approach to the IVC if it can be adequately mobilized.

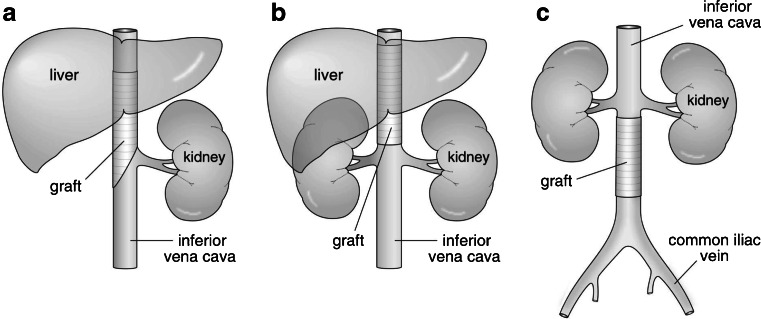

It is important to consider the length and circumference of the IVC to be removed. If the circumference of the IVC to be resected is <75 %, cavoplasty can be performed with bovine pericardium, which is available in large, 8 cm × 12 cm sheets. If the amount of IVC to be resected is >75 %, complete resection and reconstruction is required. A Gore-Tex ringed PTFE graft (W.L. Gore & Associates Inc.), sized to match the IVC diameter, can be used for reconstruction (Fig. 4). After completion of the anastomoses, forward flushing of the proximal anastomosis and backward flushing by increasing intrathoracic pressure is performed.

Fig. 4.

PTFE reconstruction of the IVC. a PTFE reconstruction after right nephrectomy of a level 2 leiomyosarcoma. b PTFE reconstruction of level 2 of the IVC. c PTFE reconstruction of level 3 of the IVC

Once the graft has been sutured into place, the abdomen should be irrigated and evaluated for adequate hemostasis. If possible, the retroperitoneal tissue should then be closed over the graft. The bowel can then be placed in its anatomical position, and the abdomen can be closed.

Graft infection, though uncommon, is a life-threatening event and has been noted to occur more frequently in the setting of concomitant bowel resection.18 However, several series have demonstrated PTFE graft infection to be an uncommon occurrence after IVC resection.6 , 19 , 20 Preoperative antibiotics and some form of coverage of the graft, using retroperitoneal tissue or omentum, may decrease the risk of graft infection. Autologous vein graft or simple ligation would be preferred in cases of gross contamination.

Postoperative Care

Anticoagulation

Few studies have demonstrated a benefit to long-term anticoagulation postoperatively, and there is no consensus on the need for aspirin or warfarin. In a study by Fiore and colleagues, antiplatelet therapy with aspirin was associated with a low rate of graft thromboses.16 Due to the high flow in the vena cava, the need for warfarin anticoagulation is generally not necessary, but many patients are placed on lifelong aspirin antiplatelet therapy at the discretion of the surgeon.

Chemotherapy

No randomized controlled trials exist evaluating the use of neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy for patients with retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas. Various types of chemotherapeutic agents have been utilized over the years in an attempt to increase survival. Hines and colleagues initially administered anthracycline-based chemotherapy, such as doxorubicin, to patients preoperatively, but after demonstrating no survival benefit, the routine use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been discontinued.19 Case reports and small retrospective studies of patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy have not demonstrated an improvement in survival or in local recurrence rates. Due to this, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) 2012 guidelines for retroperitoneal/intra-abdominal sarcomas recommend surgery for patients with resectable leiomyosarcomas. Preoperative chemotherapy, although not common, is an acceptable alternative but is considered a category 2B recommendation.21 If the tumor regresses after chemotherapy, NCCN guidelines recommend surgery.

Radiation

The potential benefit of neoadjuvant radiation includes decreasing tumor size, improving resectability, and improving local control. No studies have definitely demonstrated a benefit to preoperative radiation for retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas. In a case series reported by Mann and colleagues, the 5-year disease-free survival was 37 % with an overall survival of 56 % in patients treated with a dose of 50.4 Gy.4 The American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z9031 study was opened in an attempt to answer whether preoperative radiation improved disease-free survival compared to patients undergoing surgery alone, but it was unfortunately closed early due to low accrual.

Similar to chemotherapy, no randomized controlled trials of adjuvant radiotherapy have been published, but many clinicians advocate the use of radiotherapy in patients found to have positive margins. In a report of six patients by Kim et al., four patients were given doses of radiation between 53 and 56.4 Gy after undergoing surgical resection with varying results.22 Similar to preoperative chemotherapy, the recommendation for preoperative radiation is a category 2B recommendation of the NCCN.21 In selected patients, postoperative radiation can be considered, but this is also a category 2B recommendation.21 In patients undergoing an R0 resection, postoperative radiotherapy should be given to patients with high-grade tumors, extremely large tumors, and those with close margins. After an R1 resection, the NCCN recommends postoperative radiotherapy if neoadjuvant therapy was not given and a boost of 10–16 Gy if preoperative radiotherapy was given.

Follow-up

The perioperative 30-day mortality for patients undergoing resection has been shown to be as high as 15 %.1 , 19 If surgical resection with negative margins is successful, the 5-year survival rate has been demonstrated to be between 33 and 70 %.1 , 7 , 19 , 23 These patients should be followed, usually with CT scans, to evaluate for both local recurrence and distant metastases. The interval for follow-up should be personalized based on individual risk of recurrence. Distant metastases occur most commonly in the lungs.22 Attempts at resection of isolated recurrences or metastases and adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation should be considered in patients with a long disease-free interval and limited sites of disease with good performance status.22

Conclusion

Retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas of the IVC continue to present a challenge to surgeons. Significant improvements have been made in terms of resection and reconstruction of the IVC. Although variable survival rates have been demonstrated in numerous studies, radical resection with negative margins offers the best long-term survival for patients with retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas of the IVC.

References

- 1.Mingoli A, Cavallaro A, Sapienza P, et al. International registry of inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma: analysis of a world series on 218 patients. Anticancer Res. 1996;16(5B):3201–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laskin WB, Fanburg-Smith JC, Burke AP, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: clinicopathologic study of 40 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(6):873–81. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ddf569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hollenbeck ST, Grobmyer SR, Kent KC, et al. Surgical treatment and outcomes of patients with primary inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197(4):575–9. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00433-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mann GN, Mann LV, Levine EA, et al. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: a 2-institution analysis of outcomes. Surgery. 2012;151(2):261–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardwigsen J, Balandraud P, Ananian P, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the retrohepatic portion of the inferior vena cava: clinical presentation and surgical management in five patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200(1):57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kieffer E, Alaoui M, Piette JC, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: experience in 22 cases. Ann Surg. 2006;244(2):289–95. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000229964.71743.db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito H, Hornick JL, Bertagnolli MM, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: survival after aggressive management. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(12):3534–41. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9552-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinones-Baldrich W, Alktaifi A, Eilber F. Inferior vena cava resection and reconstruction for retroperitoneal tumor excision. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55(5):1386–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gay SB, Sistrom CL, Pevarski DJ, et al. Inferior vena cava mass and Budd-Chiari syndrome. Invest Radiol. 1993;28(8):774–6. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199308000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bieliūniene E, Kavaliauskiene G, Mitraite D, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava. Medicina (Kaunas) 2010;46(3):200–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho SW, Marsh JW, Geller DA, et al. Surgical management of leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(12):2141–8. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0700-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexander A, Rehders A, Raffel A, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: radical surgery and vascular reconstruction. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:56. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-7-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu C, Zheng Y, Yang X, et al. Surgical resection of the inferior vena cava for leiomyosarcoma. Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24(6):822.e11–5. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganeshalingam S, Rajeswaran G, Jones RL, et al. Leiomyosarcomas of the inferior vena cava: diagnostic features on cross-sectional imaging. Clin Radiol. 2011;66(1):50–6. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuevas C, Raske M, Bush WH, et al. Imaging primary and secondary tumor thrombus of the inferior vena cava: multi-detector computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2006;35(3):90–101. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiore M, Colombo C, Locati P, et al. Surgical technique, morbidity, and outcome of primary retroperitoneal sarcoma involving inferior vena cava. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(2):511–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1954-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biswas S, Amin A, Chaudry S, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the Inferior Vena Cava-Radical Resection, Vascular Reconstruction, and Challenges: A Case Report and Review of Relevant Literature. World Journal of Oncology. 2013;4(2):107–113. doi: 10.4021/wjon471w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bower TC, Nagorney DM, Cherry KJ, et al. Replacement of the inferior vena cava for malignancy: an update. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31(2):270–81. doi: 10.1016/S0741-5214(00)90158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hines OJ, Nelson S, Quinones-Baldrich WJ, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: prognosis and comparison with leiomyosarcoma of other anatomic sites. Cancer. 1999;85(5):1077–83. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990301)85:5<1077::AID-CNCR10>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Illuminati G, Calio' FG, D'Urso A, et al. Prosthetic replacement of the infrahepatic inferior vena cava for leiomyosarcoma. Arch Surg. 2006;141(9):919–24. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.9.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Network NCC. Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/sarcoma. Accessed November 20, 2012.

- 22.Kim JT, Kwon T, Cho Y, et al. Multidisciplinary treatment and long-term outcomes in six patients with leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012;82(2):101–9. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2012.82.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dew J, Hansen K, Hammon J, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: surgical management and clinical results. Am Surg. 2005;71(6):497–501. doi: 10.1177/000313480507100609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]