Abstract

Objective

We sought to characterize temporal trends in hospitalizations with heart failure as a primary or secondary diagnosis.

Background

Heart failure patients are frequently admitted for both heart failure and other causes.

Methods

Using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), we evaluated trends in heart failure hospitalizations between 2001 and 2009. Hospitalizations were categorized as either primary or secondary heart failure hospitalizations based the location of heart failure in the discharge diagnosis. National estimates were calculated using the sampling weights of the NIS. Age- and gender-standardized hospitalization rates were determined by dividing the number of hospitalizations by the United States population in a given year and using direct standardization.

Results

The number of primary heart failure hospitalizations in the United States decreased from 1,137,944 in 2001 to 1,086,685 in 2009, while secondary heart failure hospitalizations increased from 2,753,793 to 3,158,179 over the same period. Age- and gender-adjusted rates of primary heart failure hospitalizations decreased steadily over 2001–2009, from 566 to 468 per 100,000 people. Rates of secondary heart failure hospitalizations initially increased, from 1370 to 1476 per 100,000 from 2001–2006, then decreased to 1359 per 100,000 in 2009. Common primary diagnoses for secondary heart failure hospitalizations included pulmonary disease, renal failure, and infections.

Conclusions

Although primary heart failure hospitalizations declined, rates of hospitalizations with a secondary diagnosis of heart failure were stable in the past decade. Strategies to reduce the high burden of hospitalizations of heart failure patients should include consideration of both cardiac disease and non-cardiac conditions.

Keywords: Heart failure, hospitalizations, comorbidity

Heart failure is among the most common reasons for hospital admission in the United States. Given this substantial morbidity, efforts have been made to reduce the number of hospitalizations related to this disease. A number of therapies have been developed over the past two decades which have been shown to reduce heart failure hospitalizations (1–8) and quality improvement initiatives have been developed to ensure delivery of these evidence-based therapies. (9,10) To encourage such initiatives, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services began reporting on the quality of care and rate of heart failure rehospitalization for hospitals. (11)

The development of evidence-based treatments and initiatives to improve care delivery may be improving outcomes for patients. For example, while studies demonstrated that the rates of heart failure hospitalizations increased in the 1980s and 1990s, (12,13) recent data from Medicare indicate that hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis of heart failure in the elderly have declined over the last decade. (14) These findings were attributed to both improvements in treatment and reduction in prevalent heart failure. (14) Nonetheless, the majority of hospitalizations of heart failure patients are for reasons other than acute heart failure, (15,16) and quality improvement initiatives typically target only hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis of heart failure so may not impact comorbid conditions which are associated with, but not directly caused by, heart failure. We sought to evaluate recent trends in primary and secondary heart failure hospitalizations in the United States using an all-payer, representative survey of inpatient admissions.

Methods

The Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) is part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (17) The NIS represents the largest all-payer hospitalization database in the United States and samples approximately 8 million hospitalizations per year to represent national estimates.

We included all heart failure hospitalizations between 2001 and 2009 for individuals aged≥18 years. The primary unit of analysis was a patient hospitalization. Individual patients cannot be tracked longitudinally in the NIS, thus an individual may have contributed to more than one observation in a given year. Heart failure was based on the following International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) discharge diagnosis codes in any position: 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.03, 404.11, 404.13, 404.91, 404.93, and 428. (18) If one of these codes was listed in the first position, the admission was considered to be a primary heart failure hospitalization; otherwise, the admission was considered to be a secondary heart failure hospitalization. The NIS abstracts up to 15 discharge diagnosis codes, although actual hospitalizations may list more diagnoses. (17)

All patient and hospital characteristics were obtained from the NIS. Patient characteristics included demographic and outcome characteristics and comorbidities. Age was presented as a continuous variable and categorized as 18–49, 50–64, 65–74, 75–84, and ≥85 years. Race was categorized as white, black, or other. The primary payer for the hospitalization was categorized as Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, self-pay, or other. Number of chronic conditions was defined by summing the Elixhauser comorbidity index, (19) and individual comorbidities were assessed using the HCUP Clinical Classification Software (CCS) definitions. (20) Hospital characteristics included region of the country and rural versus urban density. Region of the country was categorized as Northeast, Midwest, South, or West. Rural region was based on Metropolitan Statistical Area codes prior to 2004 and Core Based Statistical Area codes beginning in 2004. (17)

Hospitalization type was based on principal discharge diagnosis. We categorized hospitalizations as heart failure (using the codes described above), cardiovascular (ICD-9-CM codes between 390 to 459 with the exception of those for heart failure) and non-cardiovascular (all other codes). Hospitalizations were also described based on both individual and multilevel CCS categories. Finally, we identified the top ten CCS categories that were listed as the primary discharge diagnoses.

Outcome related measures were presented separately for both primary and secondary heart failure diagnoses and included in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and discharge disposition. Discharge disposition was categorized as routine, intermediate care transfers, and home health care.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the sampling weights and stratified sample design of the NIS to obtain nationally-representative estimates.

Descriptive statistics for hospitalizations were presented as means with standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. We used chi-squared and one-way analysis of variance to evaluate differences in categorical and continuous variables across years. Chi-squared and Student t-tests were used to test differences in outcome characteristics between hospitalizations that did and did not have heart failure listed as the primary discharge diagnosis.

Yearly rates of primary and secondary heart failure hospitalizations were calculated by dividing the number of hospitalizations by the United States population over the age of 18 in a given year. Population estimates for this study were obtained from the United States Census Bureau. Age and gender adjusted rates of hospitalization were determined using direct standardization method, adjusted to the 2009 population. Changes in hospitalization rates between 2001 and 2009 were determined with Poisson regression in which the independent variable was the calendar year.

We performed subgroup analyses of hospitalization rates for age and gender categories; we did not calculate rates by race categories due to the large number of missing values reported for this variable in NIS (24.6%). Rates for subgroups were determined by taking the number of hospitalizations and dividing by the adult US population for the given category. We also calculated the age adjusted rates of hospitalization for gender using the population distribution of age in 2009 irrespective of gender. We tested significance in trends with Poisson regression of number of hospitalizations per year, offset by the target population in the given year.

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

From 2001 to 2009, there were an estimated 37,563,876 hospitalizations with a primary or secondary diagnosis of heart failure in the United States. Hospitalizations increased from 3,891,737 in 2001 to 4,244,865 in 2009, although the number of hospitalizations peaked in 2006 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Hospitalizations with a Primary or Secondary Diagnosis of Heart Failure

| 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Failure Hospitalizations (n) | 3,891,737 | 3,979,482 | 4,146,308 | 4,230,905 | 4,302,805 | 4,388,414 | 4,209,367 | 4,169,995 | 4,244,865 |

| Age | |||||||||

| Mean (sd) | 74.2 (0.1) | 74.0 (0.1) | 73.7 (0.2) | 73.6 (0.2) | 73.9 (0.2) | 73.4 (0.2) | 73.3 (0.2) | 73.6 (0.2) | 73.1 (0.2) |

| 18–49 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 6.0 | 6.4 |

| 50–64 | 15.5 | 16.2 | 17.0 | 17.4 | 17.1 | 18.1 | 18.6 | 18.3 | 19.2 |

| 65–74 | 22.6 | 22.3 | 22.1 | 21.8 | 21.2 | 21.2 | 21.3 | 21.2 | 21.6 |

| 75–84 | 34.0 | 33.7 | 33.1 | 32.8 | 32.6 | 31.6 | 30.8 | 30.6 | 29.6 |

| 85 and older | 22.6 | 22.3 | 22.0 | 21.9 | 23.2 | 22.7 | 22.9 | 23.9 | 23.2 |

| Female | 55.9 | 55.7 | 55.5 | 54.8 | 54.5 | 53.9 | 53.7 | 53.4 | 52.7 |

| Race | |||||||||

| White | 77.4 | 75.2 | 73.1 | 73.8 | 77.2 | 73.2 | 72.3 | 74.0 | 72.5 |

| Black | 13.1 | 14.6 | 14.9 | 15.6 | 12.1 | 15.1 | 16.1 | 14.7 | 15.5 |

| Other | 9.5 | 10.2 | 12.0 | 10.6 | 10.7 | 11.7 | 11.6 | 11.4 | 12.0 |

| Rural Region | 20.0 | 18.8 | 19.0 | 16.8 | 16.6 | 16.0 | 15.9 | 15.9 | 15.1 |

| Region | |||||||||

| Northeast | 20.3 | 20.9 | 21.0 | 19.4 | 19.6 | 19.9 | 19.5 | 19.0 | 19.8 |

| Midwest | 25.0 | 25.2 | 25.5 | 26.1 | 24.5 | 25.0 | 26.0 | 24.8 | 25.4 |

| South | 39.9 | 38.5 | 38.4 | 39.9 | 40.2 | 40.1 | 39.0 | 40.2 | 39.1 |

| West | 14.8 | 15.4 | 15.1 | 14.7 | 15.6 | 15.1 | 15.5 | 16.1 | 15.7 |

| Primary Payer | |||||||||

| Medicare | 78.2 | 78.8 | 79.2 | 78.1 | 79.5 | 78.4 | 77.0 | 76.4 | 76.3 |

| Medicaid | 5.7 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.1 | 6.5 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 7.1 |

| Private | |||||||||

| Insurance | 13.1 | 12.5 | 11.6 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 11.4 | 12.4 | 13.1 | 12.4 |

| Other | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.3 |

| Number of Comorbidities, mean (SD) | 5.58 (0.01) | 5.69 (0.02) | 5.76 (0.01) | 5.83 (0.02) | 5.88 (0.02) | 5.92 (0.02) | 5.88 (0.02) | 5.85 (0.02) | 5.91 (0.02) |

| Primary Heart Failure Diagnosis | 29.2 | 28.4 | 28.4 | 27.4 | 26.3 | 25.9 | 25.4 | 25.6 | 25.6 |

| Comorbidities | |||||||||

| Diabetes | 35.5 | 36.5 | 36.8 | 36.9 | 36.7 | 37.7 | 39.7 | 40.1 | 41.1 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 23.6 | 24.9 | 25.5 | 26.9 | 28.5 | 29.0 | 30.1 | 29.4 | 30.4 |

| Heart valve disorders | 16.0 | 16.4 | 16.8 | 16.7 | 17.4 | 18.0 | 17.9 | 16.5 | 17.4 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 9.2 | 9.2 | 8.9 | 8.4 | 8.2 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 8.0 | 7.9 |

| Coronary atherosclerosis | 46.8 | 46.9 | 46.7 | 46.6 | 46.1 | 46.9 | 47.8 | 49.7 | 49.8 |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias | 36.5 | 37.6 | 37.8 | 38.9 | 39.7 | 40.3 | 40.9 | 40.8 | 41.7 |

| Peripheral atherosclerosis | 6.8 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 8.7 |

| Pneumonia | 14.3 | 15.0 | 15.5 | 15.6 | 16.9 | 16.3 | 16.9 | 17.2 | 17.0 |

| COPD | 29.5 | 30.5 | 30.3 | 30.6 | 31.6 | 31.6 | 31.9 | 30.1 | 30.3 |

| Renal failure | 10.6 | 11.8 | 13.0 | 14.3 | 18.7 | 27.4 | 36.0 | 36.9 | 40.1 |

| Delirium and Dementia | 8.4 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 9.1 | 9.2 | 9.5 | 10.0 | 11.2 | 10.9 |

| Anemia | 21.5 | 22.4 | 22.9 | 23.8 | 23.9 | 24.5 | 26.7 | 28.8 | 30.1 |

| Mental illness | 25.5 | 27.9 | 28.5 | 29.6 | 30.7 | 32.7 | 34.7 | 37.9 | 38.3 |

| Hypertension | 53.2 | 56.2 | 57.9 | 59.9 | 60.9 | 64.1 | 65.2 | 68.2 | 69.9 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 8.2 | 8.1 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.7 | 8.4 | 8.3 |

| Liver disease | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.6 | 5.1 |

Values are in percentage points unless otherwise specified. P-values for trends across years were p<0.0001, with the exception of race (p<0.01), rural region (p<0.05) and region (p=0.9)

The mean age of patients hospitalized with a diagnosis of heart failure decreased over the period from 74.2 to 73.1 years; this decrease was primarily attributable to an increase in the proportion of hospitalizations among individuals 18–64 years, coupled with a decrease among individuals 65–84 years (Table 1). The majority of hospitalized patients were female and white, although the proportion of each decreased over the period (55.9 to 52.7% and 77.4 to 72.5%, respectively). Medicare was the most common payer for hospitalizations.

The mean number of Elixhauser comorbidities increased from 5.58 in 2001 to 5.91 in 2009 (Table 1). Cardiovascular comorbidities, including coronary atherosclerosis, cardiac arrhythmias, and hypertension, were common and increased over the period. Additionally, the prevalence of a number of related non-cardiovascular comorbid conditions dramatically increased between 2001 and 2009; for instance, the prevalence of diabetes rose from 35.5% to 41.1%, renal disease from 10.6% to 40.1%, and mental illness from 25.5% to 38.3%.

Among the total number of heart failure hospitalizations between 2001 and 2009, 26.9% carried a primary diagnosis of heart failure while the remaining 73.1% were secondary heart failure hospitalizations. The total number of primary heart failure hospitalizations declined from an estimated 1,137,944 hospitalizations in 2001 to 1,086,685 hospitalizations in 2009, representing an annual decrease of 1.0% (95% CI 0.9–1.0%) per year. Conversely, secondary heart failure hospitalizations increased from 2,753,793 to 3,158,179 over the period, with a yearly growth rate of 1.6% (95% CI 1.6-1.6%). The number of secondary heart failure hospitalizations peaked in 2006 at 3,252,693.

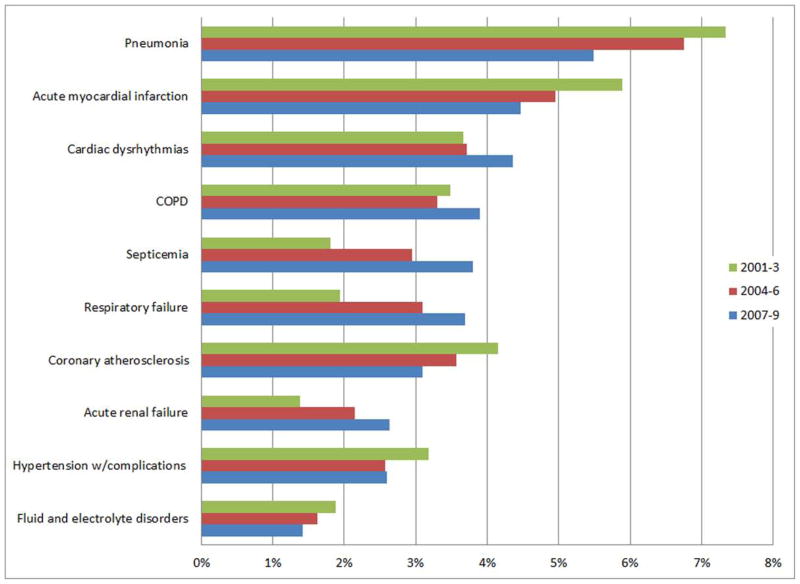

Age- and gender-standardized rates of primary heart failure hospitalization decreased during the study period, from 566 per 100,000 individuals in 2001 to 468 per 100,000 in 2009 (Figure 1). The annual rate of decline of primary heart failure hospitalization rate was 2.8% (95% CI 1.7–3.8%). Age- and gender-standardized rates of secondary heart failure hospitalizations increased annually between 2001 and 2006 and then decreased the following two years to return to levels that did not differ from those at the beginning of the decade. Overall, there was no significant change in the age- and gender-standardized rate of secondary heart failure hospitalizations over the period (annual rate of change −0.2%; 95% CI −0.9–0.4%).

Figure 1. Rates of heart failure related hospitalization.

Annual age- and gender- adjusted rates of hospitalizations in the United States with a diagnosis of heart failure in the primary versus secondary position are shown.

Rates of primary heart failure hospitalization among individuals ages 18–49 increased overall between 2001 and 2009, although the rates peaked in 2004–2006 (Table 2). Among all other age categories, primary heart failure hospitalization rates declined. Secondary heart failure hospitalizations increased significantly over the study period for subgroups of age 18–49 and 50–64; however, among older individuals, rates increased initially but subsequently declined to rates below that of 2001. Both genders showed a similar pattern in trends as the overall cohort (Table 2). Although females had higher rates of hospitalizations as compared to males, this difference was due to the older age distribution of females as compared to males. With standardization to the 2009 population distribution for age among all genders, males had higher rates of both primary (586 vs 465 per 100,000 persons) and secondary (1,526 vs 1,324 per 100,000) heart failure hospitalizations during the period.

Table 2.

Trends in Primary and Secondary Heart Failure Hospitalizations by Age and Gender Category

| Primary | Secondary | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001–2003 | 2004–2006 | 2007–2009 | 2001–2003 | 2004–2006 | 2007–2009 | |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–49 | 59 | 65 | 61 | 108 | 131 | 134 |

| 50–64 | 456 | 431 | 384 | 983 | 1071 | 1045 |

| 65–74 | 1415 | 1293 | 1095 | 3462 | 3641 | 3376 |

| 75–84 | 2899 | 2681 | 2373 | 7601 | 7906 | 7303 |

| 85 and older | 5235 | 5002 | 4521 | 14784 | 14991 | 13499 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 565 | 520 | 462 | 1448 | 1532 | 1438 |

| Male | 503 | 509 | 472 | 1205 | 1312 | 1285 |

Estimates per 100,000 population; P-trends < 0.0001 for all categories

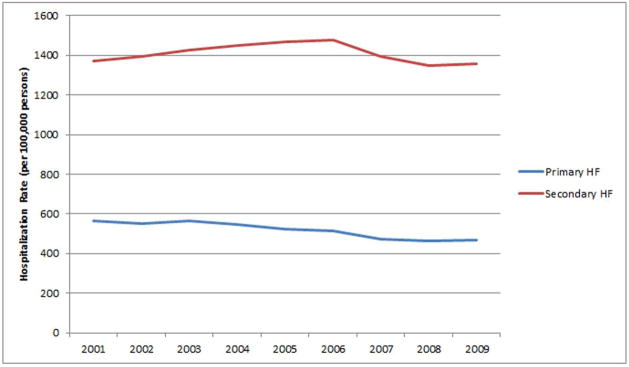

The percent of all hospitalizations that carried a primary diagnosis of heart failure decreased from 29.2% in 2001 to 25.6% in 2009. The rates of hospitalizations due to other cardiovascular causes also decreased, while hospitalizations for non-cardiovascular causes increased from 48.5% to 54.1% from 2001 to 2009. Over 16% of all hospitalizations carried a primary diagnosis related to pulmonary disease, 6% were related to digestive diseases, and nearly 6% were related to injuries and poisoning (Table 3). Significant increases in the percentage of hospitalizations for both renal and infectious diseases were observed (Table 3). Among all heart failure-related hospitalizations, pneumonia was the second most common primary diagnosis (after heart failure), although its prevalence significantly decreased during the period (Figure 2). Comparable declines in percentages of hospitalizations were observed for acute myocardial infarction and coronary atherosclerosis, while other common pulmonary diagnoses, such as COPD and respiratory failure increased. Hospitalizations for both sepsis and acute renal failure were increasingly common over the period (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Primary Diagnosis Category for Hospitalizations with a Primary or Secondary Diagnosis of Heart Failure

| 2001–2003 | 2004–2006 | 2007–2009 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular diseases | 49.9 | 46.3 | 45.3 |

| Coronary atherosclerosis | 4.2 | 3.6 | 3.1 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 5.9 | 5.0 | 4.5 |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias | 3.7 | 3.7 | 4.4 |

| Heart valve disorders | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.3 |

| Hypertension | 3.3 | 2.7 | 2.8 |

| Peripheral atherosclerosis | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Respiratory diseases | 16.0 | 16.5 | 16.6 |

| COPD | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.9 |

| Pneumonia | 7.3 | 6.8 | 5.5 |

| Diabetes | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| Genitourinary diseases | 3.4 | 4.3 | 4.9 |

| Renal Failure | 1.5 | 2.3 | 2.8 |

| Urinary tract infections | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| Diseases of the blood | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Anemia | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Diseases of the digestive system | 6.2 | 6.4 | 6.1 |

| Liver disease | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Mental illness | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Delirium and dementia | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Infectious diseases | 3.2 | 4.5 | 5.5 |

| Skin infections | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| Neoplasms | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.0 |

| Injury and poisoning | 5.4 | 5.9 | 6.1 |

| Fractures | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| Diseases of the musculoskeletal system | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| Symptoms; signs; and conditions | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| All others | 4.9 | 5.2 | 5.3 |

Figure 2. Trends in prevalence of the ten most common primary diagnoses for heart failure related hospitalizations, other than heart failure itself.

Each bars represent the percent of all heart failure related hospitalizations which were related to a given diagnosis for a three year period. P<0.001 for each diagnosis across all years.

In-hospital mortality rates significantly decreased over the decade for both primary and secondary heart failure hospitalizations (Table 4), with mortality rates nearly double for secondary as compared to primary heart failure hospitalizations. Length of stay also decreased over the period for both primary and secondary heart failure hospitalizations. Rates of both home health care and transfer to intermediate care facilities increased over the decade, and both were more common among individuals with a secondary heart failure diagnosis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Outcomes of Heart Failure Hospitalizations, by Primary vs. Secondary Diagnosis of Heart Failure

| 2001 – 2003 | 2004 – 2006 | 2007 – 2009 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Primary | Secondary | Primary | Secondary | Primary | Secondary | ||||

| Sample size, number | 3,446,627 | 8,560,084 | 3,425,655 | 9,496,468 | 3,217,925 | 9,406,341 | |||

| Mortality, % | 4.3 | 8.1 | P < 0.001 | 3.7 | 7.3 | P < 0.001 | 3.2 | 6.2 | P < 0.001 |

| Length of stay, mean (SD) | 5.56 (0.04) | 7.48 (0.05) | P < 0.001 | 5.37 (0.03) | 7.35 (0.04) | P < 0.001 | 5.27 (0.04) | 6.82 (0.05) | P < 0.001 |

| Discharge disposition, % | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | ||||||

| Routine | 61.3 | 46.4 | 56.8 | 42.3 | 54.9 | 42.7 | |||

| Hospital Transfers | 3.6 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.1 | 3.6 | |||

| SNF and Intermediate Care Transfers | 16.7 | 28.0 | 18.3 | 29.9 | 19.2 | 29.7 | |||

| Home health care | 13.3 | 12.9 | 16.6 | 16.0 | 18.4 | 17.1 | |||

Discussion

In this nationally representative sample of hospitalizations in the United States, the total number heart failure related hospitalizations increased from 3,891,737 in 2001 to 4,244,865 in 2009. During this period, primary heart failure hospitalizations steadily decreased, while the total number of secondary heart failure hospitalizations increased by nearly 400,000. As a result, the percentage of hospitalizations attributable to causes other than heart failure increased and accounted for 75% of the total number of heart failure related hospitalizations in the United States by 2009.

Prior studies have suggested that both primary and secondary heart failure hospitalizations increased significantly between 1973 and 2004. (12,13,21,22) Conversely, in a recent study of Medicare beneficiaries, Chen and colleagues found a decrease in primary heart failure hospitalizations between 1998 and 2008. (14) This study was the first to suggest that heart failure hospitalization rates were decreasing in the United States, (23) a finding which our population sample confirmed. However, our study demonstrated that the number of secondary heart failure hospitalizations increased during the period. This suggests that the improvements observed during the last decade in primary heart failure hospitalization rates have not been realized for all-cause hospitalization.

Our observed increase in secondary heart failure hospitalizations can be partly explained by the high number of rehospitalizations among patients with heart failure. Rehospitalizations have not declined significantly in recent years, (24,25) and most frequently are caused by conditions other than heart failure, so this category of hospitalizations contributes primarily to secondary heart failure hospitalizations. (23) As a result, interventions to reduce rehospitalizations and secondary heart failure hospitalizations should include consideration for treatment of comorbid conditions. We did observe a trend of improvement in secondary heart failure hospitalizations after 2006 suggesting that recent interventions to reduce all-cause rehospitalizations may be finding some success. Such interventions include clinical interventions, including the increase in home health services observed in our study, and policy interventions, including public reporting of heart failure rehospitalizations by Medicare, which began during the period. (26)

Clinical and policy interventions may have also contributed to the observed decrease in in-hospital mortality observed in our study. This trend is consistent with earlier studies of primary heart failure hospitalization in the Medicare population. However, those studies demonstrated little to no improvement in post-discharge mortality and rehospitalizations. (24,27) The effect of recent interventions on post-discharge outcomes deserves further attention.

Trends by Age and Gender

Our study demonstrated that the reductions in primary heart failure hospitalizations among the Medicare population were not observed in all age groups. We found no change in the rate of primary heart failure hospitalizations among individuals below the age of 50 between 2001 and 2009. Furthermore, these younger adults had the highest growth in secondary heart failure hospitalizations during the time period. These findings suggest that initiatives to reduce hospitalizations and rehospitalizations among heart failure patients should increase efforts to target younger patients.

At the beginning of the study, females had higher rates of primary heart failure hospitalizations than males. These gender differences were consistent with prior studies. (22) However, by the end of the study period, males had a higher rate of primary heart failure hospitalizations. These results are consistent with previous studies that have suggested that the prevalence of heart failure in males is increasing in comparison to females. (28)

Relationship with Comorbid Conditions

Both cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular comorbid conditions were common in patients hospitalized with heart failure and increased over the period. While the high rates of diseases such as diabetes, kidney disease, infections, and COPD are not surprising as some of these conditions are risk factors for heart failure, (29,30) the presence of an increased number of comorbidities has been associated with worse outcomes in heart failure. (31–33) Furthermore, the presence of multiple chronic conditions can make patient management difficult due to issues such as greater medication burden, reduced adherence, treatment for one condition worsening the other, and physician uncertainty. (34,35) New models of clinical decision making and care delivery are needed to address the needs of the increasing number of individuals with heart failure and comorbid conditions. (35,36)

Comorbidities such as COPD and renal failure may present with symptoms that are similar to heart failure which lends uncertainty to the primary diagnosis of hospitalization. Given this dilemma, our findings that primary heart failure hospitalizations decreased while secondary heart failure hospitalizations increased may be related to changes in coding practices. Medicare began tracking quality measures for primary heart failure hospitalizations in the late 1990s and this information became publicly available in 2004. (37,38) As a result of such initiatives, hospital coders had incentive to become more prudent in assigning a primary heart failure diagnosis to hospitalizations with multiple acute medical issues, so as not to subject such hospitalizations to public review. A similar “downcoding” of pneumonia hospitalizations was suggested in a recent study using the NIS dataset. (39,40) In this context, our finding of a decrease in primary heart failure hospitalizations may be partly attributable to this shift in coding practices.

Several limitations deserve mention. First, diagnostic codes are subject to misclassification and, specifically, we were unable to determine whether a secondary diagnosis represented an active condition versus a remote history of heart failure. We addressed this issue by using an algorithm for ICD9 coding that was similar to well validated ones (41–44) and comparable to those used in prior studies. (13) Second, while the NIS collects data on 8 million hospitalizations annually, or approximately 20% of all hospitalizations in the United States, the dataset is a sample and may not fully reflect all hospitalizations. Third, observations in NIS are at the level of the hospitalization rather than the individual, so we were unable to determine trends in the number of patients hospitalized for heart failure. Nonetheless, the total number of heart failure related hospitalizations are frequently used to measure the burden of this chronic disease. (45,46) Fourth, increases in prevalence of comorbidities may be due to ascertainment or detection bias. For instance, we observed a dramatic increase in the rate of comorbid kidney disease in our study, a finding which may have been influenced by increased detection of mild renal dysfunction as a result of the adoption of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) estimation with routine laboratory results. (47) Fifth, temporal changes in coding practice may have increased the prevalence of heart failure as a secondary diagnosis due to financial incentives related to “upcoding” of complicating conditions. (48) As a result, we were unable to verify the reason for observed trends in heart failure hospitalizations and believe this is an area for further research.

Conclusion

Despite trends showing a decrease in primary heart failure hospitalizations, this chronic disease still accounts for over one million primary hospitalizations each year. Additionally, patients with heart failure experience over three million secondary hospitalizations annually, often due to related comorbid conditions. In total, heart failure is associated with over four million hospitalizations per year in the United States and imparts a substantial burden on both patients and the health care system. Recent interventions do not appear to have decreased the significant number of heart failure related hospitalizations during the past decade. Future strategies to reduce hospitalizations of heart failure patients should consider both cardiac disease and non-cardiac comorbid conditions.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Ogedegbe was supported in part by grant K24HL111315 from the NHLBI

Abbreviations

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- NIS

Nationwide Inpatient Sample

Footnotes

There are no known relationships with industry

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Garg R, Yusuf S. Overview of randomized trials of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. Collaborative Group on ACE Inhibitor Trials. JAMA. 1995;273:1450–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, et al. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1309–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:709–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hjalmarson A, Goldstein S, Fagerberg B, et al. Effects of controlled-release metoprolol on total mortality, hospitalizations, and well-being in patients with heart failure: the Metoprolol CR/XL Randomized Intervention Trial in congestive heart failure (MERIT-HF). MERIT-HF Study Group. JAMA. 2000;283:1295–302. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.10.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Packer M, Bristow MR, Cohn JN, et al. The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. U.S. Carvedilol Heart Failure Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1349–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605233342101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor AL, Ziesche S, Yancy C, et al. Combination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine in blacks with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2049–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bristow MR, Saxon LA, Boehmer J, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2140–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang AS, Wells GA, Talajic M, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for mild-to-moderate heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2385–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF): rationale and design. Am Heart J. 2004;148:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC, Liang L, et al. Sex and racial differences in the use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators among patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA. 2007;298:1525–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.13.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed October 4, 2012];Hospital Compare. Available at: www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov.

- 12.Ghali JK, Cooper R, Ford E. Trends in hospitalization rates for heart failure in the United States, 1973–1986. Evidence for increasing population prevalence. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:769–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang J, Mensah GA, Croft JB, Keenan NL. Heart failure-related hospitalization in the U.S. 1979 to 2004. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:428–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen J, Normand SL, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. National and regional trends in heart failure hospitalization and mortality rates for Medicare beneficiaries, 1998–2008. JAMA. 2011;306:1669–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunlay SM, Redfield MM, Weston SA, et al. Hospitalizations after heart failure diagnosis a community perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1695–702. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blecker S, Matsushita K, Fox E, et al. Left ventricular dysfunction as a risk factor for cardiovascular and noncardiovascular hospitalizations in African Americans. Am Heart J. 2010;160:488–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. [Accessed April 24, 2012];Introduction to the HCUP nationwide inpatient sample (NIS) 2009 Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NIS_2009_INTRODUCTION.pdf.

- 18.Bonow RO, Bennett S, Casey DE, Jr, et al. ACC/AHA clinical performance measures for adults with chronic heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures (Writing Committee to Develop Heart Failure Clinical Performance Measures) endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1144–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. [Accessed October 4,2012];Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp.

- 21.Haldeman GA, Croft JB, Giles WH, Rashidee A. Hospitalization of patients with heart failure: National Hospital Discharge Survey, 1985 to 1995. Am Heart J. 1999;137:352–60. doi: 10.1053/hj.1999.v137.95495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koelling TM, Chen RS, Lubwama RN, L’Italien GJ, Eagle KA. The expanding national burden of heart failure in the United States: the influence of heart failure in women. Am Heart J. 2004;147:74–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gheorghiade M, Braunwald E. Hospitalizations for heart failure in the United States--a sign of hope. JAMA. 2011;306:1705–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bueno H, Ross JS, Wang Y, et al. Trends in length of stay and short-term outcomes among Medicare patients hospitalized for heart failure, 1993–2006. JAMA. 2010;303:2141–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heidenreich PA, Sahay A, Kapoor JR, Pham MX, Massie B. Divergent trends in survival and readmission following a hospitalization for heart failure in the Veterans Affairs health care system 2002 to 2006. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:362–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medpac. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Promoting Greater Efficiency in Medicare. Washington, DC: MedPAC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curtis LH, Greiner MA, Hammill BG, et al. Early and long-term outcomes of heart failure in elderly persons, 2001–2005. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2481–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.22.2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong CY, Chaudhry SI, Desai MM, Krumholz HM. Trends in comorbidity, disability, and polypharmacy in heart failure. Am J Med. 2011;124:136–43. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blecker S, Matsushita K, Kottgen A, et al. High-normal albuminuria and risk of heart failure in the community. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2011;58:47–55. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.02.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nichols GA, Gullion CM, Koro CE, Ephross SA, Brown JB. The incidence of congestive heart failure in type 2 diabetes: an update. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1879–84. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.8.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blecker S, Herbert R, Brancati FL. Comorbid Diabetes and End-of-Life Expenditures Among Medicare Beneficiaries With Heart Failure. Journal of cardiac failure. 2012;18:41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Go AS, Yang J, Ackerson LM, et al. Hemoglobin level, chronic kidney disease, and the risks of death and hospitalization in adults with chronic heart failure: the Anemia in Chronic Heart Failure: Outcomes and Resource Utilization (ANCHOR) Study. Circulation. 2006;113:2713–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.577577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lanfear DE, Peterson EL, Campbell J, et al. Relation of worsened renal function during hospitalization for heart failure to long-term outcomes and rehospitalization. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:74–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tinetti ME, Bogardus ST, Jr, Agostini JV. Potential pitfalls of disease-specific guidelines for patients with multiple conditions. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2870–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb042458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tinetti ME, Fried TR, Boyd CM. Designing health care for the most common chronic condition--multimorbidity. JAMA. 2012;307:2493–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Iannone L. Primary care clinicians’ experiences with treatment decision making for older persons with multiple conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:75–80. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jencks SF, Cuerdon T, Burwen DR, et al. Quality of medical care delivered to Medicare beneficiaries: A profile at state and national levels. JAMA. 2000;284:1670–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams SC, Koss RG, Morton DJ, Loeb JM. Performance of top-ranked heart care hospitals on evidence-based process measures. Circulation. 2006;114:558–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.600973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Rothberg MB. Association of diagnostic coding with trends in hospitalizations and mortality of patients with pneumonia, 2003–2009. JAMA. 2012;307:1405–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sarrazin MS, Rosenthal GE. Finding pure and simple truths with administrative data. JAMA. 2012;307:1433–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Birman-Deych E, Waterman AD, Yan Y, Nilasena DS, Radford MJ, Gage BF. Accuracy of ICD-9-CM codes for identifying cardiovascular and stroke risk factors. Med Care. 2005;43:480–5. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160417.39497.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goff DC, Jr, Pandey DK, Chan FA, Ortiz C, Nichaman MZ. Congestive heart failure in the United States: is there more than meets the I(CD code)? The Corpus Christi Heart Project. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:197–202. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quan H, Li B, Saunders LD, et al. Assessing validity of ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data in recording clinical conditions in a unique dually coded database. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:1424–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00822.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Baggett C, et al. Classification of heart failure in the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study: a comparison of diagnostic criteria. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:152–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration With the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:e1–e90. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lagu T, Rothberg MB, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Steingrub JS, Lindenauer PK. Hospitalizations, costs, and outcomes of severe sepsis in the United States 2003 to 2007. Critical care medicine. 2012;40:754–61. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232db65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Psaty BM, Boineau R, Kuller LH, Luepker RV. The potential costs of upcoding for heart failure in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:108–9. A9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]