Abstract

In the next decades the elderly population will increase dramatically, demanding appropriate solutions in health care and aging research focusing on healthy aging to prevent high burdens and costs in health care. For this, research targeting tissue-specific and individual aging is paramount to make the necessary progression in aging research. In a recently published study we have attempted to make a step interpreting aging data on chronological as well as pathological scale. For this, we sampled five major tissues at regular time intervals during the entire C57BL/6J murine lifespan from a controlled in vivo aging study, measured the whole transcriptome and incorporated temporal as well as physical health aspects into the analyses. In total, we used 18 different age-related pathological parameters and transcriptomic profiles of liver, kidney, spleen, lung and brain and created a database that can now be used for a broad systems biology approach. In our study, we focused on the dynamics of biological processes during chronological aging and the comparison between chronological and pathology-related aging.

Keywords: aging, senescence, diseases, signaling pathways, metabolism, lipofuscin

INTRODUCTION

Aging is generally considered the result of time-dependent deterioration due to stochastic, accumulative ‘wear and tear’ causing gradual degeneration. Therefore, time is the prevailing determinant in age-related processes [1, 2]. However, although aging is highly correlated with time, additional factors significantly influence the rate of aging and as a consequence, individual aging differs greatly [3-6]. Moreover, the rate of age-related deterioration and functional decline varies within every individual in a tissue-specific manner [7-12]. In humans, lifespan ranges from less than 10 years for the severe progeria patients [13, 14] to over 100 years for centenarians. Many pro-aging factors are likely controlled to some extent by genetic variation [2, 15]. However, even in genetically identical, inbred animals aging rate varies substantially among individuals [4, 16, 17]. This indicates that other factors besides time are of significance. Genomic instability due to accumulation of stochastic damage in DNA over time [16-28] causing cell death and cellular senescence is believed to be one of the drivers of aging [29-43]. It has proved difficult to mechanistically dissect processes involved in individual and tissue-specific aging.

Dynamics in aging, chronological aging and pathology-related aging

To investigate general health deterioration and loss of homeostasis in aging, we attempted to determine 1) the dynamics of biological processes during aging and 2) correlate patho-physiological aging end points to transcriptomic responses, which are generally believed to determine the cellular phenotype [44]. Previously, large scale studies provided valuable new insights into aging mechanisms in multiple species, tissues and genotypes [10, 12, 45-52]. Several of these studies focussed on young versus old comparisons [10, 45, 47, 50], making correlation studies difficult to execute.

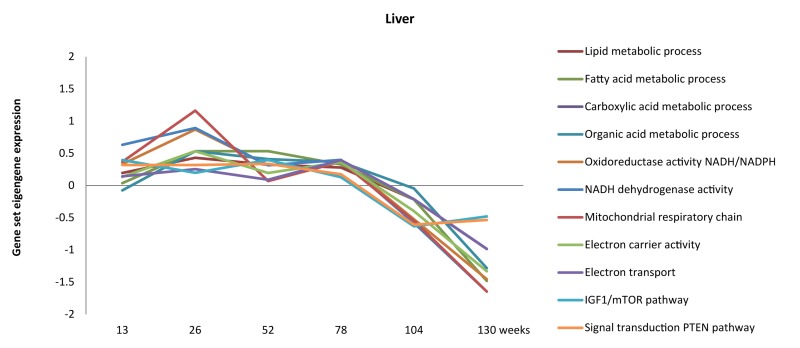

We attempted to fill part of the hiatus between chronological aging rate and its associated patho-physiological patterns in the mouse by full genome gene expression profiling of five organs at six ages covering the entire lifespan in mice [4]. Firstly, using the intercurrent gene expression profiles from the six time points, we were able to follow the dynamics of biological processes during chronological aging. For instance, energy homeostasis, lipid metabolism, IGF-1, PTEN and mitochondrial function in liver were slightly up-regulated during the first half of the lifespan but declined during the last 25% of the lifespan (Figure 1) [4]. These processes have previously been correlated to chronological aging by others [12, 53-67], but interpreting the dynamics of biological functions throughout the lifespan in multiple tissues has been proved difficult so far. Our data can contribute to unravelling the dynamics of functional pathways throughout time in several tissues.

Figure 1.

Dynamics of metabolism, energy and mitochondrial-related processes throughout aging in liver (adapted from [4]).

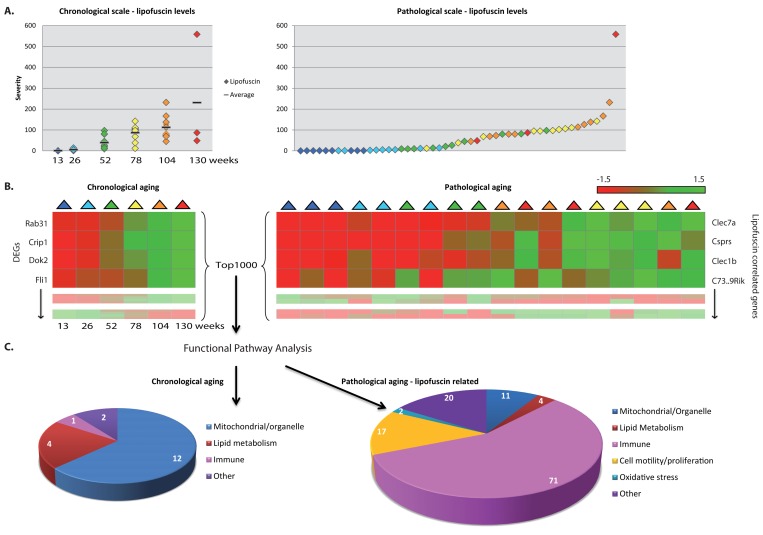

Besides focusing on the dynamics of processes during chronological aging, we additionally scored a range of age-related pathologies (n=18, of which some are possibly novel as an aging-marker, Table 1) in a systematic fashion over time in these five organs to address pathology-related aging. The age-related pathological parameters shown in Table 1 changed over time per age group; nevertheless, substantial individual variation was found (exemplified for instance by the hepatic lipofuscin accumulation in Figure 2A). Not only age-related pathological findings were tissue-specific, but the overall age-related changes in the gene expression profiles were also highly tissue-specific, arguing for caution to consider aging as a systemic generic process and take into account tissue-specific aging [7-12, 68-73].

Figure 2.

Functional pathways analyses on chronological and pathology-related scale. (A) Pathological age-related parameter lipofuscin accumulation was scored at regular intervals during aging. On average per age group lipofuscin levels increase with aging (left panel), however individual differences between chronological ages are notable (right panel). (B) Gene expression profiles were investigated according to a chronological scale (left panel, DEGs = differentially expressed genes) and pathological scale (right panel). For the latter, gene expression profiles are ranked according to correlation to the severity of the pathological parameter. (C) Functional genomics analyses using the top1000 of either chronological age-related genes or pathology-related genes indicate that besides overlapping responses, also differences are visible, e.g. immune response appeared highly correlated to hepatic lipofuscin accumulation. Numbers in diagrams represent the number of pathway hits.

To relate biological functions to age-related patho-physiological end point, we substituted chronological time for the severity of the scored age-related pathological variables in each tissue, as is demonstrated in Figure 2A for lipofuscin accumulation in liver. On a pathological scale, a liver sample of a 2 year old mouse (orange) could be considered younger than the liver of a 1 year old mouse (green) for a certain pathological parameter when the severity of this pathological condition was lower in the 2 year old sample.

Pathology-related transcriptomic profiles were generated by ranking gene expression profiles based on their correlation with the degree of age-related pathologies (Figure 2B, right panel) and subsequently assessing the biological functions of those correlated gene expression profiles (Figure 2C, right panel). These analyses revealed several biological processes that have previously been found associated with age and appeared in both our chronological and pathology-related aging analyses (Figure 2C, Figure 3). Overlap analysis, based on a ranked top1000 as input between hepatic chronological aging (Fig. 2C, left) and lipofuscin-related output in liver (Fig. 2C, right) yielded overlapping biological pathways functional in mitochondrial processes and lipid metabolism for example. However, also ample differences between aging on a chronological and a pathological scale were apparent. In liver, immune responses, cell motility/proliferation/activation and oxidative stress responses paralleled the kinetics of lipofuscin accumulation, which is a generally accepted biomarker for aging and an indicator of cumulative cellular oxidative stress (Figure 2C) [74-86]. Apparently, the lipofuscin-correlated transcripts were overrepresented in many more functional pathways than the 1000 FDR-ranked chronological genes, resulting in an increase in the number of functional (mostly immune-related) pathways. Immune responses, cell motility/adhesion and oxidative stress have been previously linked to (hepatic) injury and aging [87-98] and according to our results these related processes might be contributing factors to the biological diversity in hepatic injury and aging per individual.

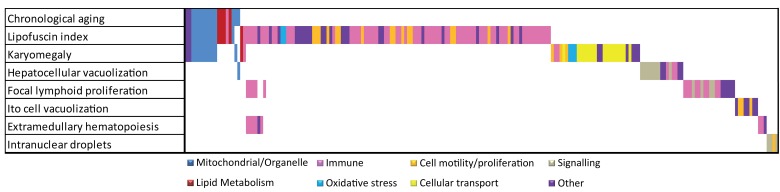

Figure 3.

Overlap analysis of functional responses in chronological and pathology-related aging. Summarized Metacore GeneGO pathways and GO responses are color coded. For chronological and each pathological parameter in liver the functional responses are plotted. Overlapping bars represent overlapping functional responses, e.g. the majority of mitochondrial/organelle-related responses are related to chronological aging, lipofuscin accumulation and karyomegaly. Immune responses are correlated to several age-related pathologies in liver.

Figure 3 depicts an overlap analysis of functional pathways between chronological and all pathology-related aging parameters for liver (for detailed information on the other tissues see [4]). Results indicate that, besides existing overlap between chronological and pathological aging processes (e.g. mitochondrial processes and lipid metabolism), many divergent functional responses were revealed using a (often tissue-specific) pathological scale. These divergent responses leave us with numerous interesting anchor points for future aging research to correlate age-related biological pathways to actual patho-physiological end-points and reveal possible underlying mechanisms, as exemplified for hepatic lipofuscin accumulation. We hope our results contribute to a new paradigm in aging and medical research taking into account individual and tissue-specific aging levels. For this however, as a next step, a systems biology approach is required to decipher causal age-related mechanisms. Correlating pathophysiological aging endpoints to gene expression and other cellular signatures will become a focus in current aging research to explore loss of homeostasis and general health decline on individual or organ-specific level. We hope that our first step in this direction will inspire other researchers to contribute to resolve these complex processes using an integral multi-disciplinary system biology approach.

Acknowledgments

The work presented here was in part financially supported by IOP Genomics IGE03009, NIH/NIA (3PO1 AG017242), STW Grant STW-LGC.6935 and Netherlands Bioinformatics Center (NBIC) BioRange II – BR4.1. Support was also obtained from Markage (FP7-Health-2008-200880), LifeSpan (LSHG-CT-2007-036894), European Research Council (ERC advanced scientist grant JHJH).

Footnotes

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Ressler S, Bartkova J, Niederegger H, Bartek J, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, Jansen-Durr P, Wlaschek M. p16INK4A is a robust in vivo biomarker of cellular aging in human skin. Aging cell. 2006;5:379–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijg J. Oxford University Press; 2007. Aging of the Genome, The dual role of DNA in life and death. [Google Scholar]

- Cherkas LF, Aviv A, Valdes AM, Hunkin JL, Gardner JP, Surdulescu GL, Kimura M, Spector TD. The effects of social status on biological aging as measured by white-blood-cell telomere length. Aging cell. 2006;5:361–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonker MJ, Melis JP, Kuiper RV, van der Hoeven TV, Wackers PF, Robinson J, van der Horst GT, Dolle ME, Vijg J, Breit TM, Hoeijmakers JH, van Steeg H. Life spanning murine gene expression profiles in relation to chronological and pathological aging in multiple organs. Aging cell. 2013;12:901–909. doi: 10.1111/acel.12118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomas-Loba A, Bernardes de Jesus B, Mato JM, Blasco MA. A metabolic signature predicts biological age in mice. Aging cell. 2013;12:93–101. doi: 10.1111/acel.12025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holly AC, Melzer D, Pilling LC, Henley W, Hernandez DG, Singleton AB, Bandinelli S, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Harries LW. Towards a gene expression biomarker set for human biological age. Aging cell. 2013;12:324–326. doi: 10.1111/acel.12044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busuttil R, Bahar R, Vijg J. Genome dynamics and transcriptional deregulation in aging. Neuroscience. 2007;145:1341–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.09.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu C, Hickey M, Morrison M, McCarter R, Han ES. Tissue specific and non-specific changes in gene expression by aging and by early stage CR. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 2006;127:905–916. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass D, Vinuela A, Davies MN, Ramasamy A, Parts L, Knowles D, Brown AA, Hedman AK, Small KS, Buil A, Grundberg E, Nica AC, Di Meglio P, et al. Gene expression changes with age in skin, adipose tissue, blood and brain. Genome biology. 2013;14:R75. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-7-r75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SK, Kim K, Page GP, Allison DB, Weindruch R, Prolla TA. Gene expression profiling of aging in multiple mouse strains: identification of aging biomarkers and impact of dietary antioxidants. Aging cell. 2009;8:484–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00496.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swindell WR. Comparative analysis of microarray data identifies common responses to caloric restriction among mouse tissues. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 2008;129:138–153. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn JM, Poosala S, Owen AB, Ingram DK, Lustig A, Carter A, Weeraratna AT, Taub DD, Gorospe M, Mazan-Mamczarz K, Lakatta EG, Boheler KR, Xu X, et al. AGEMAP: a gene expression database for aging in mice. PLoS genetics. 2007;3:e201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleaver JE, Lam ET, Revet I. Disorders of nucleotide excision repair: the genetic and molecular basis of heterogeneity. Nature reviews Genetics. 2009;10:756–768. doi: 10.1038/nrg2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer KH, Patronas NJ, Schiffmann R, Brooks BP, Tamura D, DiGiovanna JJ. Xeroderma pigmentosum, trichothiodystrophy and Cockayne syndrome: a complex genotype-phenotype relationship. Neuroscience. 2007;145:1388–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeijmakers JH. DNA damage, aging, and cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361:1475–1485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander CF, Solleveld HA, Zurcher C, Nooteboom AL, Van Zwieten MJ. Biological and clinical consequences of longitudinal studies in rodents: their possibilities and limitations. An overview. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 1984;28:249–260. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(84)90025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis JP, Wijnhoven SW, Beems RB, Roodbergen M, van den Berg J, Moon H, Friedberg E, van der Horst GT, Hoeijmakers JH, Vijg J, van Steeg H. Mouse models for xeroderma pigmentosum group A and group C show divergent cancer phenotypes. Cancer research. 2008;68:1347–1353. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilai A, Rotman G, Shiloh Y. ATM deficiency and oxidative stress: a new dimension of defective response to DNA damage. DNA repair. 2002;1:3–25. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(01)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholtz N, Demuth I. DNA-repair in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. DNA repair. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canugovi C, Misiak M, Ferrarelli LK, Croteau DL, Bohr VA. The role of DNA repair in brain related disease pathology. DNA repair. 2013;12:578–587. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diderich K, Alanazi M, Hoeijmakers JH. Premature aging and cancer in nucleotide excision repair-disorders. DNA repair. 2011;10:772–780. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolle ME, Snyder WK, Gossen JA, Lohman PH, Vijg J. Distinct spectra of somatic mutations accumulated with age in mouse heart and small intestine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:8403–8408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giese H, Dolle ME, Hezel A, van Steeg H, Vijg J. Accelerated accumulation of somatic mutations in mice deficient in the nucleotide excision repair gene XPA. Oncogene. 1999;18:1257–1260. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis JP, Kuiper RV, Zwart E, Robinson J, Pennings JL, van Oostrom CT, Luijten M, van Steeg H. Slow accumulation of mutations in Xpc mice upon induction of oxidative stress. DNA repair. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.08.019. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis JP, Luijten M, Mullenders LH, van Steeg H. The role of XPC: implications in cancer and oxidative DNA damage. Mutation research. 2011;728:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis JP, van Steeg H, Luijten M. Oxidative DNA damage and nucleotide excision repair. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2013;18:2409–2419. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono T, Miyamura Y, Ikehata H, Yamanaka H, Kurishita A, Yamamoto K, Suzuki T, Nohmi T, Hayashi M, Sofuni T. Spontaneous mutant frequency of lacZ gene in spleen of transgenic mouse increases with age. Mutation research. 1995;338:183–188. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(95)00023-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevnsner T, Nyaga S, de Souza-Pinto NC, van der Horst GT, Gorgels TG, Hogue BA, Thorslund T, Bohr VA. Mitochondrial repair of 8-oxoguanine is deficient in Cockayne syndrome group B. Oncogene. 2002;21:8675–8682. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltrami E, Ruggiero A, Busuttil R, Migliaccio E, Pelicci PG, Vijg J, Giorgio M. Deletion of p66Shc in mice increases the frequency of size-change mutations in the lacZ transgene. Aging cell. 2013;12:177–183. doi: 10.1111/acel.12036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garinis GA, Uittenboogaard LM, Stachelscheid H, Fousteri M, van Ijcken W, Breit TM, van Steeg H, Mullenders LH, van der Horst GT, Bruning JC, Niessen CM, Hoeijmakers JH, Schumacher B. Persistent transcription-blocking DNA lesions trigger somatic growth attenuation associated with longevity. Nature cell biology. 2009;11:604–615. doi: 10.1038/ncb1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasty P, Vijg J. Accelerating aging by mouse reverse genetics: a rational approach to understanding longevity. Aging cell. 2004;3:55–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyng KJ, May A, Stevnsner T, Becker KG, Kolvra S, Bohr VA. Gene expression responses to DNA damage are altered in human aging and in Werner Syndrome. Oncogene. 2005;24:5026–5042. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Wang Z, Ghosh S, Zhou Z. Defective ATM-Kap-1-mediated chromatin remodeling impairs DNA repair and accelerates senescence in progeria mouse model. Aging cell. 2013;12:316–318. doi: 10.1111/acel.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslov AY, Ganapathi S, Westerhof M, Quispe-Tintaya W, White RR, Van Houten B, Reiling E, Dolle ME, van Steeg H, Hasty P, Hoeijmakers JH, Vijg J. DNA damage in normally and prematurely aged mice. Aging cell. 2013;12:467–477. doi: 10.1111/acel.12071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheu A, Maraver A, Klatt P, Flores I, Garcia-Cao I, Borras C, Flores JM, Vina J, Blasco MA, Serrano M. Delayed ageing through damage protection by the Arf/p53 pathway. Nature. 2007;448:375–379. doi: 10.1038/nature05949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rufini A, Tucci P, Celardo I, Melino G. Senescence and aging: the critical roles of p53. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.640. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepe S, Payan-Gomez C, Milanese C, Hoeijmakers JH, Mastroberardino PG. Nucleotide excision repair in chronic neurodegenerative diseases. DNA repair. 2013;12:568–577. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seviour EG, Lin SY. The DNA damage response: Balancing the scale between cancer and ageing. Aging. 2010;2:900–907. doi: 10.18632/aging.100248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh Y, Vijg J. Maintaining genetic integrity in aging: a zero sum game. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2006;8:559–571. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Jurk D, Maddick M, Nelson G, Martin-Ruiz C, von Zglinicki T. DNA damage response and cellular senescence in tissues of aging mice. Aging cell. 2009;8:311–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell. 2005;120:513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J, Yaswen P. Aging and cancer cell biology, 2009. Aging cell. 2009;8:221–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijg J, Campisi J. Puzzles, promises and a cure for ageing. Nature. 2008;454:1065–1071. doi: 10.1038/nature07216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Eberwine J. RNA: state memory and mediator of cellular phenotype. Trends in cell biology. 2010;20:311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Magalhaes JP, Curado J, Church GM. Meta-analysis of age-related gene expression profiles identifies common signatures of aging. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:875–881. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swindell WR. Gene expression profiling of long-lived dwarf mice: longevity-associated genes and relationships with diet, gender and aging. BMC genomics. 2007;8:353. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swindell WR. Genes and gene expression modules associated with caloric restriction and aging in the laboratory mouse. BMC genomics. 2009;10:585. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swindell WR. Dietary restriction in rats and mice: a meta-analysis and review of the evidence for genotype-dependent effects on lifespan. Ageing research reviews. 2012;11:254–270. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swindell WR, Johnston A, Sun L, Xing X, Fisher GJ, Bulyk ML, Elder JT, Gudjonsson JE. Meta-profiles of gene expression during aging: limited similarities between mouse and human and an unexpectedly decreased inflammatory signature. PloS one. 2012;7:e33204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southworth LK, Owen AB, Kim SK. Aging mice show a decreasing correlation of gene expression within genetic modules. PLoS genetics. 2009;5:e1000776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis JPM, et al. Nucleotide Excision Repair and Cancer. In: Vengrova DS, editor. DNA Repair and Human Health. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech; 2011. pp. 121–144. [Google Scholar]

- Melis JPM. Department of Toxicogenetics. Leiden: Leiden University Medical Center; 2012. Nucleotide excision repair in aging & cancer; p. 158. [Google Scholar]

- Katic M, Kennedy AR, Leykin I, Norris A, McGettrick A, Gesta S, Russell SJ, Bluher M, Maratos-Flier E, Kahn CR. Mitochondrial gene expression and increased oxidative metabolism: role in increased lifespan of fat-specific insulin receptor knock-out mice. Aging cell. 2007;6:827–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00346.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova EA, Antoch MP, Novototskaya LR, Chernova OB, Paszkiewicz G, Leontieva OV, Blagosklonny MV, Gudkov AV. Rapamycin extends lifespan and delays tumorigenesis in heterozygous p53+/− mice. Aging. 2012;4:709–714. doi: 10.18632/aging.100498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linford NJ, Beyer RP, Gollahon K, Krajcik RA, Malloy VL, Demas V, Burmer GC, Rabinovitch PS. Transcriptional response to aging and caloric restriction in heart and adipose tissue. Aging cell. 2007;6:673–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steelman LS, Chappell WH, Abrams SL, Kempf RC, Long J, Laidler P, Mijatovic S, Maksimovic-Ivanic D, Stivala F, Mazzarino MC, Donia M, Fagone P, Malaponte G, et al. Roles of the Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR pathways in controlling growth and sensitivity to therapy-implications for cancer and aging. Aging. 2011;3:192–222. doi: 10.18632/aging.100296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluher M, Kahn BB, Kahn CR. Extended longevity in mice lacking the insulin receptor in adipose tissue. Science. 2003;299:572–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1078223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar D, Trifunovic A. The mtDNA mutator mouse: Dissecting mitochondrial involvement in aging. Aging. 2009;1:1028–1032. doi: 10.18632/aging.100109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzenberger M, Dupont J, Ducos B, Leneuve P, Geloen A, Even PC, Cervera P, Le Bouc Y. IGF-1 receptor regulates lifespan and resistance to oxidative stress in mice. Nature. 2003;421:182–187. doi: 10.1038/nature01298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keniry M, Parsons R. The role of PTEN signaling perturbations in cancer and in targeted therapy. Oncogene. 2008;27:5477–5485. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenaz G, Baracca A, Fato R, Genova ML, Solaini G. New insights into structure and function of mitochondria and their role in aging and disease. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2006;8:417–437. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merry BJ. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial function with aging--the effects of calorie restriction. Aging cell. 2004;3:7–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulliam DA, Bhattacharya A, Van Remmen H. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Aging and Longevity: A Causal or Protective Role? Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2012 doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scialo F, Mallikarjun V, Stefanatos R, Sanz A. Regulation of Lifespan by the Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain: Reactive Oxygen Species-Dependent and Reactive Oxygen Species-Independent Mechanisms. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2012 doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo K, Choi E, Lee D, Jeong DE, Jang SK, Lee SJ. Heat shock factor 1 mediates the longevity conferred by inhibition of TOR and insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathways in C. elegans. Aging cell. 2013 doi: 10.1111/acel.12140. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solari F, Bourbon-Piffaut A, Masse I, Payrastre B, Chan AM, Billaud M. The human tumour suppressor PTEN regulates longevity and dauer formation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Oncogene. 2005;24:20–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng N, Yang KT, Bayan JA, He L, Aggarwal R, Stiles JW, Hou X, Medina V, Abad D, Palian BM, Al-Abdullah I, Kandeel F, Johnson DL, et al. PTEN controls beta-cell regeneration in aged mice by regulating cell cycle inhibitor p16. Aging cell. 2013 doi: 10.1111/acel.12132. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busuttil RA, Garcia AM, Reddick RL, Dolle ME, Calder RB, Nelson JF, Vijg J. Intra-organ variation in age-related mutation accumulation in the mouse. PloS one. 2007;2(9):e876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Clauson CL, Robbins PD, Niedernhofer LJ, Wang Y. The oxidative DNA lesions 8,5'-cyclopurines accumulate with aging in a tissue-specific manner. Aging cell. 2012;11:714–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00828.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan M, Yamaza H, Sun Y, Sinclair J, Li H, Zou S. Temporal and spatial transcriptional profiles of aging in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome research. 2007;17:1236–1243. doi: 10.1101/gr.6216607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T, Zhang J, Xie L, Dong X, Zhang L, Cai YD, Li YX. Crosstissue coexpression network of aging. Omics : a journal of integrative biology. 2011;15:665–671. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow AT, Witkowski S, Marshall MR, Wang J, Lima LC, Guth LM, Spangenburg EE, Roth SM. Chronic exercise modifies age-related telomere dynamics in a tissue-specific fashion. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2012;67:911–926. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijg J, Busuttil RA, Bahar R, Dolle ME. Aging and genome maintenance. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2005;1055:35–47. doi: 10.1196/annals.1323.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunk UT, Jones CB, Sohal RS. A novel hypothesis of lipofuscinogenesis and cellular aging based on interactions between oxidative stress and autophagocytosis. Mutation research. 1992;275:395–403. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(92)90042-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgakopoulou EA, Tsimaratou K, Evangelou K, Fernandez Marcos PJ, Zoumpourlis V, Trougakos IP, Kletsas D, Bartek J, Serrano M, Gorgoulis VG. Specific lipofuscin staining as a novel biomarker to detect replicative and stress-induced senescence. A method applicable in cryo-preserved and archival tissues. Aging. 2013;5:37–50. doi: 10.18632/aging.100527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel SK, Lalwani ND, Reddy JK. Peroxisome proliferation and lipid peroxidation in rat liver. Cancer research. 1986;46:1324–1330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohn A, Grune T. Lipofuscin: formation, effects and role of macroautophagy. Redox biology. 2013;1:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung T, Bader N, Grune T. Lipofuscin: formation, distribution, and metabolic consequences. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1119:97–111. doi: 10.1196/annals.1404.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz T, Eaton JW, Brunk UT. Redox activity within the lysosomal compartment: implications for aging and apoptosis. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2010;13:511–523. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis JP, Speksnijder EN, Kuiper RV, Salvatori DC, Schaap MM, Maas S, Robinson J, Verhoef A, van Benthem J, Luijten M, van Steeg H. Detection of genotoxic and non-genotoxic carcinogens in Xpc(−/−)p53(+/−) mice. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2013;266:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira PI, Santos MS, Oliveira CR. Alzheimer's disease: a lesson from mitochondrial dysfunction. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2007;9:1621–1630. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya K, Nakagawa K, Santa T, Shintani Y, Fujie H, Miyoshi H, Tsutsumi T, Miyazawa T, Ishibashi K, Horie T, Imai K, Todoroki T, Kimura S, et al. Oxidative stress in the absence of inflammation in a mouse model for hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer research. 2001;61:4365–4370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perse M, Injac R, Erman A. Oxidative status and lipofuscin accumulation in urothelial cells of bladder in aging mice. PloS one. 2013;8:e59638. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terman A, Brunk UT. Oxidative stress, accumulation of biological ‘garbage’, and aging. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2006;8:197–204. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terman A, Kurz T, Navratil M, Arriaga EA, Brunk UT. Mitochondrial turnover and aging of long-lived postmitotic cells: the mitochondrial-lysosomal axis theory of aging. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2010;12:503–535. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Chen M, Manivannan A, Lois N, Forrester JV. Age-dependent accumulation of lipofuscin in perivascular and subretinal microglia in experimental mice. Aging cell. 2008;7:58–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunk UT, Terman A. Lipofuscin: mechanisms of age-related accumulation and influence on cell function. Free radical biology & medicine. 2002;33:611–619. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00959-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droge W, Schipper HM. Oxidative stress and aberrant signaling in aging and cognitive decline. Aging cell. 2007;6:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go YM, Jones DP. Redox control systems in the nucleus: mechanisms and functions. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2010;13:489–509. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearps AC, Martin GE, Angelovich TA, Cheng WJ, Maisa A, Landay AL, Jaworowski A, Crowe SM. Aging is associated with chronic innate immune activation and dysregulation of monocyte phenotype and function. Aging cell. 2012;11:867–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackaman C, Radley-Crabb HG, Soffe Z, Shavlakadze T, Grounds MD, Nelson DJ. Targeting macrophages rescues age-related immune deficiencies in C57BL/6J geriatric mice. Aging cell. 2013;12:345–357. doi: 10.1111/acel.12062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun JI, Lau LF. Cellular senescence controls fibrosis in wound healing. Aging. 2010;2:627–631. doi: 10.18632/aging.100201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labunskyy VM, Gladyshev VN. Role of Reactive Oxygen Species-Mediated Signaling in Aging. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2013;19:1362–1372. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Xu Y. p53, oxidative stress, and aging. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2011;15:1669–1678. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnappan S, Ponnappan U. Aging and immune function: molecular mechanisms to interventions. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2011;14:1551–1585. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian F, Wang X, Zhang L, Chen S, Piecychna M, Allore H, Bockenstedt L, Malawista S, Bucala R, Shaw AC, Fikrig E, Montgomery RR. Age-associated elevation in TLR5 leads to increased inflammatory responses in the elderly. Aging cell. 2012;11:104–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00759.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheedfar F, Biase SD, Koonen D, Vinciguerra M. Liver diseases and aging: friends or foes? Aging cell. 2013 doi: 10.1111/acel.12128. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swindell WR, Johnston A, Xing X, Little A, Robichaud P, Voorhees JJ, Fisher G, Gudjonsson JE. Robust shifts in S100a9 expression with aging: a novel mechanism for chronic inflammation. Scientific reports. 2013;3:1215. doi: 10.1038/srep01215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]