Abstract

PP2A is a family of mammalian serine/threonine phosphatases that is involved in the control of many cellular functions including protein synthesis, cellular signaling, cell cycle determination, apoptosis, metabolism, and stress responses through the negative regulation of signaling pathways initiated by protein kinases. Rapid progress is being made in the understanding of PP2A complex and its functions. Emerging studies have correlated changes in PP2A with human diseases, especially cancer. PP2A is comprised of 3 subunits: a catalytic subunit, a scaffolding subunit, and a regulatory subunit. The alternations of the subunits have been shown to be in association with many human malignancies. Therapeutic agents targeting PP2A inhibitors or activating PP2A directly have shed light on the therapy of cancers. This review focuses on PP2A structure, cancer-associated mutations, and the targeting of PP2A-related molecules to restore or reactivate PP2A in anticancer therapy, especially in digestive system cancer therapy.

1. Introduction

Protein phosphatase 2A(PP2A) is a member of phosphoprotein phosphatase (PPP) family which belongs to the superfamily of protein serine/threonine phosphatases that reverse the actions of protein kinases by cleaving phosphate from serine and threonine residues of proteins. It has been proven that PP2A regulates various cellular processes, including protein synthesis, cellular signaling, cell cycle determination, apoptosis, metabolism, and stress responses [1–3]. PP2A is widely described as a tumor suppressor since the first recognition that its inhibitor okadaic acid is a tumor promoter, and mutations of PP2A subunits can be detected in a variety of human malignancies. The tumor suppressing function of PP2A makes it a possible target in anticancer therapy.

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer in males and the second in females, and about 25% of patients with colorectal cancer present with overt metastatic disease. Forty to 50% of newly diagnosed patients can develop metastasis [4, 5]. Liver cancer is the fifth most common cancer in males and the seventh most in females worldwide. It ranks the third in cancer-related deaths [5]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) which account for 70–85% of primary malignancies in liver is the dominant histological type of primary liver cancer [6]. To date, the treatment of these two cancers is not satisfactory, and the discovery of new therapeutic agents is in demand. Among all the possible targets, PP2A is a promising one.

In this review, we focus on the structure of PP2A and the possible mechanism of its participation in anticancer therapy with special emphasis on targeting PP2A in colorectal cancer and HCC.

2. PP2A Structure and Cancer-Associated Mutations

The holoenzyme structure of PP2A comprises a 36 kDa catalytic subunit (PP2AC or C subunit), a 65 kDa scaffolding subunit (PR65 or A subunit), and a regulatory subunit (B subunit). A C subunit and an A subunit make the PP2A core enzyme (PP2AD) which then binds with a B subunit, thus, making the PP2A heterotrimeric holoenzyme (PP2AT).

The catalytic subunit PP2AC is comprised of 309 amino acids and has two different isoforms (α and β) which are encoded by two separated genes but share 97% sequence similarity. Despite the sequence similarity, PP2ACα and PP2ACβ seem to not be able to compensate for each other because PP2ACα knockout mice cannot survive. PP2AC is highly expressed in hearts and brains and is mainly distributed in cytoplasm and nucleus. The regulation of PP2AC is highly organized and precise which is usually made up of phosphorylation at Tyr307 and Thr304 and methylation at Leu309. Phosphorylation at Thr304 is regulated by autophosphorylation-activated protein kinase and can inhibit the recruitment of B55 subunits [7, 8]. Thr307 can be phosphorylated by p60v-src as well as by other receptor and nonreceptor tyrosine kinases which results in a decrease of phosphatase activity and thus can inhibit the interaction with B56 subunits and B55 subunits [9]. The posttranslational modification with methylation at Leu309 is catalyzed by leucine carboxyl methyltransferase 1 (LCMT1) and PP2A methylesterase-1 (PME-1). The methylation can enhance the affinity of PP2A for B55 subunits which can be reversed by phosphorylation at Tyr307 [10] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Nomenclature of subunits of PP2A and the subcellular distribution.

| Subunit | Gene name | Gene locus | Isoforms | Aliases | Subcellular distribution | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | PPP2R1A | 19q13.14 | Aα | PR65α | Cytoplasm | [1, 25, 54, 55] |

| PPP2R1B | 11q23.1 | Aβ | PR65β | Cytoplasm | [1, 13, 25, 54] | |

|

| ||||||

| B | PPP2R2A | 8p21.1 | Bα | PR55α, B55α | Cytoplasm, microtubules, neurofilaments, vimentin, membrane, nucleus, Golgi/reticulum | [1, 25, 54] |

| PPP2R2B | 5q32 | Bβ | PR55β, B55β | Cytosol | [1, 25, 54, 56] | |

| PPP2R2C | 4p16.1 | Bγ | PR55γ, B55γ | Cytoskeletal fraction | [1, 25, 54, 57] | |

| PPP2R2D | 10q26.3 | Bδ | PR55δ, B55δ | Cytosol | [1, 25, 54] | |

|

| ||||||

| B′ | PPP2R5A | 1q32.3 | B′α | PR61α, B56α | Cytoplasm | [1, 25, 54] |

| PPP2R5B | 11q13.1 | B′β | PR61β1, B56β, PR61β2 | Cytoplasm | [1, 25, 54, 58] | |

| PPP2R5C | 14q32.31 | B′γ1 B′γ2 B′γ3 |

PR61γ1, B56γ1, B′α3 PR61γ2, B56γ2, B′α2 B56γ3, B′α1 |

Cytoplasm, nucleus, focal adhesion |

[1, 25, 54] | |

| PPP2R5D | 6p21.1 | B′δ | PR61δ, B56δ | Cytosol, mitochondria, nucleus, microsomes | [1, 25, 54] | |

| PPP2R5E | 14q23.2 | B′ε | PR61ε, B56ε | Cytoplasm | [1, 25, 54] | |

|

| ||||||

| B′′ | PPP2R3A | 3q22.1 | B′′α1 B′′α2 |

PR130 PR72 |

Centrosome and Golgi Cytosol |

[1, 25, 54, 59] |

| PPP2R3B | Xp22.33 | B′′β1 B′′β2 |

PR48 PR59 |

Nucleus | [1, 25, 54] | |

| PPP2R3C | B′′γ | G5PR | Nucleus | [1, 25, 54] | ||

|

| ||||||

| B′′′ | STRN | 2p22.2 | PR110, PR93 | Membrane and cytoplasm | [1, 25, 54] | |

| STRN3 | 14q12 | PR112, PR102,PR94 | nucleus | [1, 25, 54] | ||

|

| ||||||

| C | PPP2CA | 5q31.1 | Cα | PP2Aα | Cytoplasm and nucleus | [1, 25, 54] |

| PPP2CB | 8p12 | Cβ | PP2Aβ | Cytoplasm and nucleus | [1, 25, 54, 60] | |

The A subunit serves as a structural subunit and can bind to a C subunit with its C-terminal repeats 11–15 and to a B subunit with its N-terminal repeats 1–10. The A subunit structure is composed of 15 tandem repeats of a 39 to 41 amino-acid sequence which is called HEAT (huntingtin/elongation/A subunit/TOR) motif. The HEAT repeats of the scaffold A subunit form a horseshoe-shaped fold, holding the catalytic C and regulatory B′ subunits together on the same side [11]. Like the C subunit, the A subunit is also composed of two isoforms (α and β) which share an 87% sequence similarity, and both are widely expressed in cytoplasm. Despite the consistency in the sequence, the 2 isoforms are functionally distinct and cannot substitute for each other, because overexpressed Aα fails to revert the transformed phenotype in Aβ suppressed cells [12]. Unlike Aα, which is ubiquitously expressed in different tissues and cells, the Aβ expression level varies and can sometimes be detected with mutations in tumor tissues with a more common frequency. Mutations of both genes are found to occur at low frequency in human tumors. The gene encoding Aβ was founded to be altered in 15% of primary lung cancers, 15% of colorectal cancers, and 13% of breast cancers, making it unable to bind to B and/or C subunits in vitro [13–15]. The alternations include gene deletion, point mutation, missense, and frameshifts. Sablina et al. found that loss of Aβ can permit immortalized human cells to achieve a tumorigenic state and contribute to cancer progression through dysregulation of small guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) RalA activity which can be dephosphorylated by Aβ at Ser183 and Ser184 and is thus a necessity for the transformed phenotype induced by suppression of Aβ [12, 16]. The Aα gene alternations can also be found in a variety of neoplasms, like melanomas, breast cancers, and lung cancers, though in a lower frequency when compared with Aβ [14, 17]. To date, 4 kinds of caner-associated mutation of Aα have been detected: E64D, E64G, R418W, and Δ171-589 [17]. The specific binding of SV40 small t (ST) antigen to Aα can lead to the elimination of its capacity to from complex with B56γ which results in human cell transformation [18]. By introducing Aα mutants into immortalized but nontumorigenic human cells, Chen et al. found that Aα mutants can induce functional haploinsufficiency which can somehow lead to the deficiency to dephosphorylate Akt. Then, the active form of Akt results in the human cell transformation [19] (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Cancer-associated mutations of PP2A A subunits.

| Subunit | Mutation name | Alternations | Consequence | Cancer type | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR65α | E64D E64G R418W |

Point mutation |

Deficiency in binding to B′α1 Deficiency in binding to B/C subunits |

Breast Lung Skin |

[15, 17, 61] |

| Δ171-589 | Deletion | Breast | |||

|

| |||||

| PR65β | G8R P65S G90D L101P L101P/V448A K343E V448A D504G V545A |

Missense | Dysregulation of RalA GTPase, leading to impaired binding capacity to B/C subunits |

Lung Breast Colon |

[12, 15, 43] |

| ΔE344-E388 | In-frame deletion | [12, 15, 43] | |||

The regulatory B subunits are encoded by 4 unrelated gene families: PR55/B (PPP2R2A, PPP2R2B, PPP2R2C, PPP2R2D), PR56/61/B′ (PPP2R5A, PPP2R5B, PPP2R5C, PPP2R5D, PPP2R5E), PR130/72/48/59/G5PR/B′′ (PPP2R3A, PPP2R3B, PPP2R3C), and PR93/110/B′′′ (STRN, STRN3), and each member from the 4 families shows no similarity in sequence. The B family has 4 isoforms: α, β, γ, and δ. They all show a time and space expression pattern: the α and δ isoforms are widely distributed in tissues, while the β and γ isoforms are enriched in the brain. The expression level of the β isoform decreases while γ elevates. The mainly subcellular distribution of these 4 isoforms are cytoplasm/nucleus, cytosol, cytoskeletal fraction, and cytosol, respectively [1]. The B′ family has 5 isoforms: α, β, γ, δ, and ε. Like the B family, they are also expressed and enriched in certain tissues and subcellular cavity. All B′ family members contain a highly conserved central region which is 80% identical and is responsible for the interaction with A/C subunits and a divergent C-terminal and N-terminal which may confer different functions, such as regulation of substrate specificity and subcellular targeting [20]. The B′′ family contains 5 isoforms that might arise from the same gene by alternative splicing. PR 130 is widely expressed in all tissues and enriched in the heart and muscle, while PR72 is exclusively expressed in the heart and muscle. PR48 shares 68% homology with PR59 and is mainly distributed in nucleus. It is an interaction partner of Cdc6 which functions in the initiation of DNA replication. PR59 is believed to be an interaction partner of p107 protein, and when overexpressed, it can bind to and dephosphorylate p107 protein, thus, leading to the expression of DNA damage related genes which induces inhibition of cell cycle progression [21]. The B′′′ family contains newly identified members that share a conserved epitope with the B′ family. PR93, also termed S/G2 nuclear autoantigen (SG2NA), is mainly distributed in the brain and muscle while PR110, also termed striatin mainly in the postsynaptic densities of neuronal dendrites [22]. They both can act as a calmodulin binding protein to interact with PP2AC in a calcium-dependent manner. It is believed that the variety of B subunits accounts for the functional specificity of PP2A. Besides the cancer-associated mutations of the A subunits, the alternations of B subunits can also contribute to cell transformation. Alternation of certain types of B subunits have been detected in neoplasms, like the decreased expression level of B56γ in human melanoma cell lines [23]. Ito et al. reported that a truncated B56γ1 isoform which can disrupt PP2A phosphatase activity in vivo is expressed in a metastatic clone, BL6, of mouse B16 melanoma cells and is sufficient to enhance the metastasis of another clone, F10 [24]. The overexpression of PR65γ in human embryonic kidney epithelial cells and human hepatocellular cell lines can revert the cell transformation [18] (Table 1).

3. Reactivate PP2A to Augment Anticancer Effect by Targeting Inhibitory Proteins of PP2A

To date, 4 kinds of cellular inhibitory proteins of PP2A has been described, namely, CIP2A, pp32/I1 PP2A , SET/I2 PP2A, and SETBP1. Compared with environmental toxins like okadaic acid, they are more selective. Emerging studies suggest that aberrant expression and/or activity of these phosphatase inhibitors may be associated with many human malignancies (Table 3).

Table 3.

Inhibitory protein of PP2A and possible related anticancer drugs.

| Inhibitory protein | Interaction with PP2A | Drugs against inhibitory | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIP2A | Prevent PP2A-dependent dephosphorylating of c-Myc | Bortezomib; Erlotinib | [32–35] |

| PHAPI/pp32/I2 PP1A | Direct binding | Jacalin | [39, 40] |

| SET/I2 PP2A | Direct binding | COG112; Apolipoprotein E-mimetis peptides | [39, 43, 44] |

| SETBP1 | Form a SETBP1-SET-PP2A complex | [45] |

3.1. CIP2A

The increased expression of cancerous inhibitor of PP2A(CIP2A) has been described in many kinds of malignancy like HCC, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, prostate cancer, lung cancer, chronic myeloid leukemia, and acute myeloid leukemia [25]. In nonsmall cell lung cancer, CIP2A elevation correlated with elevated C-Myc expression levels, and is a significant prognostic predicator for poor survival [26]. Likewise, in acute myeloid leukemia, prostate cancer, and other malignancies, increased CIP2A predicts poor differentiation and worse consequences [27, 28].

Many studies have demonstrated that the disruption and dysfunction of PP2A is a requirement for malignant transformation. Because of PP2A's multiple functions in pathway regulations and variant functions attributed to different PP2A subunits, the mechanism of induced cell transformation is distinct and complicated, such as the dysregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and the Bcl-2 family of apoptosis regulators as well as the deficiency in inhibiting the oncogenic transcription factor c-Myc [29]. C-Myc has two phosphorylation residues: Ser62 and Thr58. The phosphorylation of Thr58 permits the dephosphorylation by PP2A on Ser62 which lead to further degradation of C-Myc. In human cell transformation, inhibition of PP2A fails to dephosphorylate c-Myc Ser62, making it overexpressed in malignancies [30]. The possible mechanism underlying the inhibition of PP2A-mediated c-Myc Ser62 dephosphorylation has been interpreted by Junttila et al. The PP2A inhibitor CIP2A can act as the c-Myc stabilizing protein. It can directly bind to c-Myc through recognition of the Ser62 site and then prevent PP2A-dependent dephosphorylation of c-Myc [31].

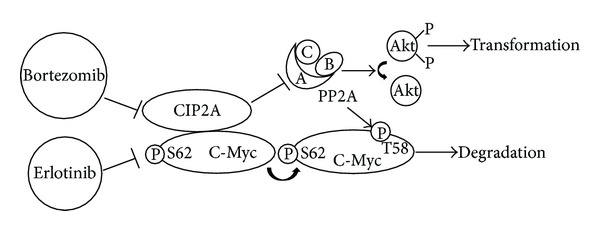

In consideration of its inhibition of PP2A in the stabilization of c-Myc and other signals like the Akt signal, CIP2A has be found to be an anticancer target. CIP2A is reported to be a target of bortezomib in many kinds of malignancies, such as HCC, leukemia, human triple negative breast cancer, and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [32, 33]. Chen et al. found that bortezomib can downregulate CIP2A in a dose- and time-dependent manner, and can upregulate PP2A activity in HCC. The inhibition of CIP2A by bortezomib leads to PP2A-dependent Akt inactivation and tumor cell apoptosis [34]. The apoptotic effect of bortezomib is also described in leukemia cells by downregulation of CIP2A and upregulation of PP2A activity [35]. Bortezomib can sensitize solid tumor cells to radiation through the inhibition of CIP2A [36]. Besides apoptosis-inducing role of bortezomib by antagonizing CIP2A, the induced autophagy by bortezomib also depends on the down-regulation of CIP2A and p-Akt in HCC [37]. And in sensitive hepatocellular cells, the apoptosis- inducing effect of erlotinib is mediated by down-regulation of CIP2A besides its status as a selective epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI). The newly discovered effect of erlotinib by CIP2A-dependent p-Akt down-regulation makes CIP2A a possible target in the treatment of HCC [38] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Bortezomib and erlotinib restore PP2A activity by targeting CIP2A. Bortezomib and erlotinib downregulate CIP2A which leads to up-regulation of PP2A activity and therefore inhibiting cell transformation by inactivating Akt.

3.2. PHAPI/pp32/I1PP2A

The protein putative human HLA-DR-associated protein I(PHAPI), which has been variously identified as pp32 or I1 PP2A, is a putative HLA class II-associated cytosolic protein and also a potent tumor suppressor. It has been shown to be a PP2A inhibitor though the detailed mechanism has not been fully understood, probably by binding directly to the C subunit [39]. Yu et al. found that the antiproliferative lectin, jacalin, can dissociate PP2A from PHAPI through inducing tyrosine phosphorylation of PHAPI in HT29 colon cancer cells [40]. This may seem contradictory because PHAPI itself is a tumor suppressor and PP2A is also a tumor suppressor. However, no proper explanation has been discovered. The inhibitory function of PHAPI is probably dominant in the aspect of inducing apoptosis.

3.3. SET/I2PP2A

The oncogene SET and its truncated cytoplasmic form I2 PP2A are also inhibitory proteins of PP2A. It is discovered that SET is fused with the nucleoporin NU214 (CAN), and it is associated with myeloid leukemogenesis and highly expressed in Wilms' tumors and BCR-ABL1-positive leukemia. Its overexpression predicts poor prognosis [41]. Elevated expression of SET has been linked to cell growth and transformation. SET can inhibit PP2A by forming an inhibitory protein complex with PP2A [39]. Besides, it can also form an inhibitory complex with nm23-H1 which can inhibit tumor metastasis [42].

Eichhorn et al. discovered that a novel apolipoprotein E-based peptide, COG112, can inhibit the interaction of SET with PP2AC, leading to increased PP2A activity. With increased PP2A activity, the p-Akt and c-Myc activity decreases. COG112 can also release SET from nm23-H1, thus, restoring the metastasis suppressor function of nm23-H1 [43]. Also, apolipoprotein E-mimetis peptides can bind to SET, therefore, restoring PP2A activity [44].

3.4. SETBP1

The SET binding protein (SETBP1) is a SET regulator, and it is fused in frame with a nucleoporin, NUP98. SETBP1 is overexpressed in 27.6% of acute myeloid leukemia at diagnosis and is associated with poor prognosis, particularly in elderly patients, as patients with SETBP1 overexpression had a significantly shorter overall survival and event-free survival in patients over 60 years. SETBP1 overexpression protects SET from protease cleavage which increases the amount of full-length SET protein and leads to the formation of a SETBP1-SET-PP2A complex. The SETBP1-SET-PP2A complex can inhibit PP2A and therefore promote the proliferation of leukemic cells [45, 46]. Piazza et al. found mutated SETBP1 (encoding a p.Gly870Ser alternation) to be a new oncogene present in atypical chronic myeloid leukemia as cells expressing this mutant exhibit higher amounts of SETBP1 and SET protein and lower PP2A activity [47].

4. PP2A-Activating Drugs

PP2A can be activated by various agents though direct or indirect interaction, like ceramide and FTY720. The general consequence of reactivation of PP2A in malignancies is apoptosis of cancer cells, and others may include cell proliferation inhibition and cell cycle arrest.

4.1. Ceramide

Ceramide has been shown to be a potent tumor suppressor which can trigger apoptosis and autophagy and limit cancer cell proliferation. The downstream of ceramide include many players, like PP2A, p38, JNK, Akt, and survivin. In ceramide-induced mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), which is a key event in apoptotic signaling, the activation of PP2A is an important step to activate GSK-3β. Ceramide-activated PP2A can dephosphorylate GSK-3β at Ser9 through PI3K-Akt pathway [48]. In ceramide-induced cell cycle arrest, the accumulation of p27 is due to the activation of PP2A which leads to the inhibition of Akt [49].

4.2. FTY720

The immunosuppressant FTY720 is a sphingosine analogue that is approved for the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis. It can induce apoptosis in peripheral blood lymphocytes. Its anticancer function has been discovered in many kinds of malignancies, like breast cancer, leukemia, HCC, and prostate cancer, and so forth [50, 51]. However, the mechanism underlying the anticancer therapy varies. In HCC cells, the FTY720-induced apoptosis is mediated through the PKCδ signal. In leukemia cells, FTY720-direct mitochondrion-related apoptosis is mediated by FTY720-induced PP2A activation which is the outcome of FTY720 disrupting SET-PP2A interaction [51, 52].

Other PP2A-activating drugs, like forskolin, chloroethylnitrosourea, and vitamin E analogues, and so forth, are listed in Table 4. A PP2A-activating protein E1A is also described. It is reported to increase PP2A activity by upregulating PP2AC subunits, which results in the repression of Akt activation and the subsequent apoptosis [53].

Table 4.

PP2A-activating drugs/protein.

| Activating drugs/Proteins | Mechanism | Malignancies | Consequences | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceramide | Activation of PP2A, leading to activation of GSK-3β or accumulation of p27 | Prostate cancer | Apoptosis; Cell cycle arrest | [48, 49] |

| FTY720 | Disrupt SET–PP2A interaction | Leukemia | Apoptosis | [51, 52] |

| Forskolin | Induces PP2A activity by increasing intracellular cAMP levels | Leukemia | Block proliferation; induce apoptosis | [62, 63] |

| Chloroethylnitrosourea | Augment methylation of PP2A, leading to Akt dephosphorylation | Melanoma | Reduce cell proliferation and survival | [64, 65] |

| Vitamin E analogues (i.e., α-tocopheryl succinate) | Reduce PKCα isotype (colon cancer) or inactivation of JNKs (prostate cancer) activity by increasing PP2A activity | Colon, prostate cancer | Apoptosis | [66, 67] |

| Carnosic acid | Downregulate AKT/IKK/NFκB by activation of PP2A | Prostate cancer | Apoptosis | [68] |

| Methylprednisolone | Upregulate PP2A B subunits | Myeloid leukemia | Cell differentiation | [69] |

| Dithiolethione |

Increase PP2A concentration | Lung, breast cancer | Inhibit proliferation | [70] |

| E1A | Upregulate PP2A C subunits | Breast cancer | Apoptosis | [53] |

5. Targeting PP2A in Digestive System Cancers

The PP2A alternations and PP2A inactivation have been described in many kinds of digestive system cancers, like colorectal cancer and HCC. Suppression of PP2A activity may serve a carcinogenesis role in alimentary system malignancies. PP2A subunits have been found to be mutated or deleted to some degree in various digestive system cancers. The subunit Aβ alternation has been detected in 15% of colorectal cancer, and it is related to its capacity of binding to a B and/or a C subunit, which leads to a decreased PP2A activity [13]. Besides the relatively low frequency of PP2A mutations and deletions, Tan et al. found that the epigenetic mechanism may play a dominant role in PP2A inactivation in colorectal cancer. They found that epigenetic silencing of PP2A regulatory B55β subunit can be detected in more than 90% of colorectal cancers [71]. The PP2A inhibitory protein CIP2A is increased in colorectal cancer and HCC, accompanied by impaired PP2A activity. So, in digestive system cancers, PP2A has its unique role in malignancy suppression and can be a target in anticancer therapy.

In colon cancers, researches reveal that resistance to antiangiogenesis therapy exists in CSLCs. It is the consequence of PP2A activity suppression in CSLCs in colon cancer cells. By suppressing PP2A, the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is activated, which leads to the activation of (heat shock protein 27) Hsp27 and the subsequent antiapoptotic effect of Hsp27 [72]. PP2A inhibition in CSLCs of glioblastoma effectively controls the cell differentiation and/or death through modulating the Akt/mammalian TOR (mTOR)/GSK-3β pathway [73]. In colorectal cancer, PP2A inhibition is essential for the maintenance of CSLCs through the Akt Ser473/mTOR pathway [74]. So, the inhibition of PP2A confers CSLCs the characteristics of stem cells and is of significant importance to the initiation of cancers. The therapeutic reactivation of PP2A in CSLCs can be a possible anticancer treatment against drug resistance and recurrence. Wang et al. did find that by activating PP2A, silibinin can suppress the self-renewal of CLSCs and inhibit sphere formation and tumor initiation in colorectal cancer [74].

As has been mentioned, ceramide is a potent tumor suppressor which can lead to tumor cell apoptosis and autophagy. By activating PP2A, ceramide can induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest either by GSK-3β activation or p27 accumulation. Ceramide is a sphingolipid consisting of sphingosine, and sphingadienes (SDs) is another derivative from soy and other natural sphingolipids. SDs are reported to inhibit cell growth and tumorigenesis by inhibiting Wnt signaling through PP2A/Akt/GSK-3β pathway in colon cancer [75]. The chemopreventive effect of SDs relies on PP2A activation, which may serve as an upstream target of SDs in downregulating Wnt signaling. The activating mutations in Wnt signaling have been linked to the initiation of colorectal cancer [76]. However, the down-regulation of Wnt signaling by PP2A is not universal. Aspirin and mesalazine are found to be able to decrease Wnt/β-catenin in colorectal cell lines which make them possible chemopreventive agents. Aspirin and mesalazine treatment are both associated with phosphorylation of PP2A which is an inactive form of PP2A [77, 78]. Some other anti-colon-cancer agents like dihydroxyphenylethanol (DPE) are also reported to induce apoptosis or cell cycle arrest by activating PP2A [79].

In HCC, as mentioned above, CIP2A overexpression can be detected, and bortezomib can downregulate CIP2A and upregulate PP2A activity in HCC. The inhibition of CIP2A by bortezomib leads to tumor cell apoptosis and autophagy. HCC cells with high levels of CIP2A are more resistant to bortezomib treatment than those with low level of CIP2A. Erlotinib can also downregulate CIP2A which leads to apoptosis in HCC. A few erlotinib derivatives have been found as CIP2A-ablating agents in HCC cell line SK-Hep-1. The compounds N4-(3-Ethynylphenyl)-6,7-dimethoxy-N2-(4-phenoxyphenyl) quinazoline-2,4-diamine and N2-Benzyl-N4-(3-ethynylphenyl)-6,7-dimethoxyquinazoline-2,4-diamine can induce HCC cell apoptosis by inhibiting CIP2A [80]. Zanthoxylum avicennae extracts (YBBEs) and diosmin can inhibit HCC cell line HA22T cell proliferation by activating PP2A [81, 82].

6. Conclusion

It has been almost 30 years since the first recognition that okadaic acid is a tumor promoter and targets PP2A [83], and emerging studies have made it solid that PP2A is a tumor suppressor and that its regulation can be a target for anticancer therapy. This review is mainly focused on the restoration and activation of PP2A in human malignancies by targeting PP2A inhibitory proteins or directly activating or upregulating PP2A. However, we should never neglect the controversy that exists that whether PP2A is a real tumor suppressor, because there are also ever-growing evidences against this fundamental hypothesis. For example, Zimmerman et al. found that the inactivation of PP2A, in particular, of the B56γ and B56δ subunits, is a crucial step in triggering apoptin-induced tumor-selective cell death [84]. Antitumor drugs like cantharidin control cell cycle and induce apoptosis by inhibiting PP2A [85], and cell viability inhibition and proapoptotic effect of cantharidin in PANC-1 pancreatic cancer is mediated by the PP2A/IκB kinase (IKKα)/IκBα/p65 NF-κB pathway [86]. Accordingly, PP2A-mediated anticancer therapy may include two opposed aspects, activation and inhibition, mainly depending on the cell types or the transforming agents. And despite the progress made in the field of targeting PP2A in anticancer therapy, there is still a long way ahead to clinical application. Much effort is needed in the molecular mechanisms and medical translation of possible therapeutic agents targeting PP2A.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author's Contribution

Weibo Chen participated in the study design and wrote the paper. Zhongxia Wang participated in the study design and edited the paper. Chunping Jiang participated in the study design and edited the paper. Yitao Ding conceived the study, participated in its design, and gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors have read and approved the final paper. Weibo Chen and Zhongxia Wang contributed equally to the work as cofirst authors.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Science Fund of the Ministry of Health of China (no. LW201008) and Key Project supported by Medical Science and Technology Development Foundation, Nanjing Department of Health (no. ZKX12011), and the Scientific Research Foundation of Graduate School of Nanjing University (no. 2013CL14).

References

- 1.Janssens V, Goris J. Protein phosphatase 2A: a highly regulated family of serine/threonine phosphatases implicated in cell growth and signalling. Biochemical Journal. 2001;353(3):417–439. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3530417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Virshup DM. Protein phosphatase 2A: a panoply of enzymes. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2000;12(2):180–185. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schönthal AH. Role of serine/threonine protein phosphatase 2A in cancer. Cancer Letters. 2001;170(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00561-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Cutsem E, Köhne C-H, Hitre E, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(14):1408–1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA: Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJF, Bell BP. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. Journal of Hepatology. 2006;45(4):529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo H, Reddy SAG, Damuni Z. Purification and characterization of an autophosphorylation-activated protein serine threonine kinase that phosphorylates and inactivates protein phosphatase 2A. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268(15):11193–11198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janssens V, Longin S, Goris J. PP2A holoenzyme assembly: in cauda venenum (the sting is in the tail) Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2008;33(3):113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brautigan DL. Flicking the switches: phosphorylation of serine/threonine protein phosphatases. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 1995;6(4):211–217. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1995.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Favre B, Zolnierowicz S, Turowski P, Hemmings BA. The catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 2A is carboxyl-methylated in vivo. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(23):16311–16317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho US, Xu W. Crystal structure of a protein phosphatase 2A heterotrimeric holoenzyme. Nature. 2007;445(7123):53–57. doi: 10.1038/nature05351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sablina AA, Chen W, Arroyo JD, et al. The tumor suppressor PP2A Aβ regulates the RalA GTPase. Cell. 2007;129(5):969–982. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang SS, Esplin ED, Li JL, et al. Alterations of the PPP2R1B gene in human lung and colon cancer. Science. 1998;282(5387):284–287. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calin GA, di Iasio MG, Caprini E, et al. Low frequency of alterations of the α (PPP2R1A) and β (PPP2R1B) isoforms of the subunit A of the serine-threonine phosphatase 2A in human neoplasms. Oncogene. 2000;19(9):1191–1195. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruediger R, Pham HT, Walter G. Alterations in protein phosphatase 2A subunit interaction in human carcinomas of the lung and colon with mutations in the Aβ subunit gene. Oncogene. 2001;20(15):1892–1899. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sablina AA, Hahn WC. The role of PP2A A subunits in tumor suppression. Cell Adhesion & Migration. 2007;1(3):140–141. doi: 10.4161/cam.1.3.4986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruediger R, Pham HT, Walter G. Disruption of protein phosphatase 2a subunit interaction in human cancers with mutations in the Aα subunit gene. Oncogene. 2001;20(1):10–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen W, Possemato R, Campbell KT, Plattner CA, Pallas DC, Hahn WC. Identification of specific PP2A complexes involved in human cell transformation. Cancer Cell. 2004;5(2):127–136. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen W, Arroyo JD, Timmons JC, Possemato R, Hahn WC. Cancer-associated PP2A Aα subunits induce functional haploinsufficiency and tumorigenicity. Cancer Research. 2005;65(18):8183–8192. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCright B, Rivers AM, Audlin S, Virshup DM. The B56 family of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) regulatory subunits encodes differentiation-induced phosphoproteins that target PP2A to both nucleus and cytoplasm. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(36):22081–22089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Voorhoeve PM, Hijmans EM, Bernards R. Functional interaction between a novel protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunit, PR59, and the retinoblastoma-related p107 protein. Oncogene. 1999;18(2):515–524. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno CS, Park S, Nelson K, et al. WD40 repeat proteins striatin and S/G2 nuclear autoantigen are members of a novel family of calmodulin-binding proteins that associate with protein phosphatase 2A. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(8):5257–5263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deichmann M, Polychronidis M, Wacker J, Thome M, Näher H. The protein phosphatase 2A subunit Bγ gene is identified to be differentially expressed in malignant melanomas by subtractive suppression hybridization. Melanoma Research. 2001;11(6):577–585. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito A, Kataoka TR, Watanabe M, et al. A truncated isoform of the PP2A B56 subunit promotes cell motility through paxillin phosphorylation. EMBO Journal. 2000;19(4):562–571. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.4.562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perrotti D, Neviani P. Protein phosphatase 2A: a target for anticancer therapy. The Lancet Oncology. 2013;14(6):e229–e238. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70558-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong Q-Z, Wang Y, Dong X-J, et al. CIP2A is overexpressed in non-small cell lung cancer and correlates with poor prognosis. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2011;18(3):857–865. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1313-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaarala MH, Vaisanen M-R, Ristimaki A. CIP2A expression is increased in prostate cancer. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;29, article 136 doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-29-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Li W, Li L, Yu X, Jia J, Chen C. CIP2A is over-expressed in acute myeloid leukaemia and associated with HL60 cells proliferation and differentiation. International Journal of Laboratory Hematology. 2011;33(3):290–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-553X.2010.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arroyo JD, Hahn WC. Involvement of PP2A in viral and cellular transformation. Oncogene. 2005;24(52):7746–7755. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Junttila MR, Westermarck J. Mechanisms of MYC stabilization in human malignancies. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(5):592–596. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.5.5492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Junttila MR, Puustinen P, Niemelä M, et al. CIP2A Inhibits PP2A in human malignancies. Cell. 2007;130(1):51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tseng L-M, Liu C-Y, Chang K-C, Chu P-Y, Shiau C-W, Chen K-F. CIP2A is a target of bortezomib in human triple negative breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Research. 2012;14(2, article R68) doi: 10.1186/bcr3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin Y-C, Chen K-C, Chen C-C, Cheng A-L, Chen K-F. CIP2A-mediated Akt activation plays a role in bortezomib-induced apoptosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Oral Oncology. 2012;48(7):585–593. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen K-F, Liu C-Y, Lin Y-C, et al. CIP2A mediates effects of bortezomib on phospho-Akt and apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2010;29(47):6257–6266. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu C-Y, Shiau C-W, Kuo H-Y, et al. Cancerous inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A determines bortezomib-induced apoptosis in leukemia cells. Haematologica. 2013;98(5):729–738. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.050187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang C-Y, Wei C-C, Chen K-C, Chen H-J, Cheng A-L, Chen K-F. Bortezomib enhances radiation-induced apoptosis in solid tumors by inhibiting CIP2A. Cancer Letters. 2012;317(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu H-C, Hou D-R, Liu C-Y, et al. Cancerous inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A mediates bortezomib-induced autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma independent of proteasome. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055705.e55705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu H-C, Chen H-J, Chang Y-L, et al. Inhibition of CIP2A determines erlotinib-induced apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2013;85(3):356–366. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li M, Makkinje A, Damuni Z. The myeloid leukemia-associated protein SET is a potent inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(19):11059–11062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu L-G, Packman LC, Weldon M, Hamlett J, Rhodes JM. Protein phosphatase 2A, a negative regulator of the ERK signaling pathway, is activated by tyrosine phosphorylation of putative HLA class II-associated protein I (PHAPI)/pp32 in response to the antiproliferative lectin, jacalin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(40):41377–41383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Switzer CH, Cheng RYS, Vitek TM, Christensen DJ, Wink DA, Vitek MP. Targeting SET/I2 PP2A oncoprotein functions as a multi-pathway strategy for cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2011;30(22):2504–2513. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fan Z, Beresford PJ, Oh DY, Zhang D, Lieberman J. Tumor suppressor NM23-H1 is a granzyme A-activated DNase during CTL-mediated apoptosis, and the nucleosome assembly protein set is its inhibitor. Cell. 2003;112(5):659–672. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eichhorn PJA, Creyghton MP, Bernards R. Protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunits and cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2009;1795(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christensen DJ, Ohkubo N, Oddo J, et al. Apolipoprotein E and peptide mimetics modulate inflammation by binding the SET protein and activating protein phosphatase 2A. The Journal of Immunology. 2011;186(4):2535–2542. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cristóbal I, Blanco FJ, Garcia-Orti L, et al. SETBP1 overexpression is a novel leukemogenic mechanism that predicts adverse outcome in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2010;115(3):615–625. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-227363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cristóbal I, Garcia-Orti L, Cirauqui C, et al. Overexpression of SET is a recurrent event associated with poor outcome and contributes to protein phosphatase 2A inhibition in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2012;97(4):543–550. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.050542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piazza R, Valletta S, Winkelmann N, et al. Recurrent SETBP1 mutations in atypical chronic myeloid leukemia. Nature Genetics. 2012;45(1):18–24. doi: 10.1038/ng.2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin C-F, Chen C-L, Chiang C-W, Jan M-S, Huang W-C, Lin Y-S. GSK-3β acts downstream of PP2A and the PI 3-kinase-Akt pathway, and upstream of caspase-2 in ceramide-induced mitochondrial apoptosis. Journal of Cell Science. 2007;120(16):2935–2943. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim SW, Kim HJ, Chun YJ, Kim MY. Ceramide produces apoptosis through induction of p27kip1 by protein phosphatase 2A-dependent Akt dephosphorylation in PC-3 prostate cancer cells. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health A. 2010;73(21-22):1465–1476. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2010.511553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Azuma H, Takahara S, Ichimaru N, et al. Marked prevention of tumor growth and metastasis by a novel immunosuppressive agent, FTY720, in mouse breast cancer models. Cancer Research. 2002;62(5):1410–1419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsuoka Y, Nagahara Y, Ikekita M, Shinomiya T. A novel immunosuppressive agent FTY720 induced Akt dephosphorylation in leukemia cells. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2003;138(7):1303–1312. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neviani P, Harb JG, Oaks JJ, et al. Blood: 2010. Washington, DC, USA: The American Society of Hematology; 2010. BCR-ABL1 kinase activity but not its expression is dispensable for Ph plus quiescent stem cell survival which depends on the PP2A-controlled Jak2 activation and is sensitive to FTY720 treatment; pp. 227–228. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liao Y, Hung M-C. A new role of protein phosphatase 2A in adenoviral E1A protein-mediated sensitization to anticancer drug-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Research. 2004;64(17):5938–5942. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sontag E. Protein phosphatase 2A: the trojan horse of cellular signaling. Cellular Signalling. 2001;13(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(00)00123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ruteshouser EC, Ashworth LK, Huff V. Absence of PPP2R1A mutations in Wilms tumor. Oncogene. 2001;20(16):2050–2054. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schöls L, Amoiridis G, Büttner T, Przuntek H, Epplen JT, Riess O. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia: phenotypic differences in genetically defined subtypes? Annals of Neurology. 1997;42(6):924–932. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu P, Yu L, Zhang M, et al. Molecular cloning and mapping of the brain-abundant B1γ subunit of protein phosphatase 2A, PPP2R2C, to human chromosome 4p16. Genomics. 2000;67(1):83–86. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCright B, Brothman AR, Virshup DM. Assignment of human protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunit genes B56α, B56β, B56γ, B56δ, and B56ε (PPP2R5A-PPP2R5E), highly expressed in muscle and brain, to chromosome regions 1q41, 11q12, 3p21, 6p21.1, and 7p11.2 → p12. Genomics. 1996;36(1):168–170. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seshacharyulu P, Pandey P, Datta K, Batra SK. Phosphatase: PP2A structural importance, regulation and its aberrant expression in cancer. Cancer Letters. 2013;335(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jones TA, Barker HM, Da Cruz Silva EEF, et al. Localization of the genes encoding the catalytic subunits of protein phosphatase 2A to human chromosome bands 5q23→q31 and 8p12→p11.2, respectively. Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 1993;63(1):35–41. doi: 10.1159/000133497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruediger R, Zhou J, Walter G. Mutagenesis and expression of the scaffolding Aα and Aβ subunits of PP2A. In: Moorhead G, editor. Protein Phosphatase Protocols. Vol. 365. 2007. pp. 85–99. (Methods in Molecular Biology). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cristóbal I, Garcia-Orti L, Cirauqui C, Alonso MM, Calasanz MJ, Odero MD. PP2A impaired activity is a common event in acute myeloid leukemia and its activation by forskolin has a potent anti-leukemic effect. Leukemia. 2011;25(4):606–614. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feschenko MS, Stevenson E, Nairn AC, Sweadner KJ. A novel cAMP-stimulated pathway in protein phosphatase 2A activation. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2002;302(1):111–118. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guénin S, Schwartz L, Morvan D, et al. PP2A activity is controlled by methylation and regulates oncoprotein expression in melanoma cells: a mechanism which participates in growth inhibition induced by chloroethylnitrosourea treatment. International Journal of Oncology. 2008;32(1):49–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Madhunapantula SV, Mosca PJ, Robertson GP. The Akt signaling pathway: an emerging therapeutic target in malignant melanoma. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2011;12(12):1032–1049. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.12.18442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang P-H, Wang D, Chuang H-C, Wei S, Kulp SK, Chen C-S. α-tocopheryl succinate and derivatives mediate the transcriptional repression of androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells by targeting the PP2A-JNK-Sp1-signaling axis. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(7):1125–1131. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Neuzil J, Weber T, Schröder A, et al. Induction of cancer cell apoptosis by α-tocopheryl succinate: molecular pathways and structural requirements. The FASEB Journal. 2001;15(2):403–415. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0251com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kar S, Palit S, Ball WB, Das PK. Carnosic acid modulates Akt/IKK/NF-κB signaling by PP2A and induces intrinsic and extrinsic pathway mediated apoptosis in human prostate carcinoma PC-3 cells. Apoptosis. 2012;17(7):735–747. doi: 10.1007/s10495-012-0715-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Uzunoglu S, Uslu R, Tobu M, et al. Augmentation of methylprednisolone-induced differentiation of myeloid leukemia cells by serine/threonine protein phosphatase inhibitors. Leukemia Research. 1999;23(5):507–512. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(99)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Switzer CH, Ridnour LA, Cheng RYS, et al. Dithiolethione compounds inhibit Akt signaling in human breast and lung cancer cells by increasing PP2A activity. Oncogene. 2009;28(43):3837–3846. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tan J, Lee PL, Li Z, et al. B55β-associated PP2A complex controls PDK1-directed Myc signaling and modulates rapamycin sensitivity in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(5):459–471. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lin S-P, Lee Y-T, Yang S-H, et al. Colon cancer stem cells resist antiangiogenesis therapy-induced apoptosis. Cancer Letters. 2013;328(2):226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lu J, Zhuang Z, Song DK, et al. The effect of a PP2A inhibitor on the nuclear receptor corepressor pathway in glioma: laboratory investigation. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2010;113(2):225–233. doi: 10.3171/2009.11.JNS091272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang J-Y, Chang C-C, Chiang C-C, Chen W-M, Hung S-C. Silibinin suppresses the maintenance of colorectal cancer stem-like cells by inhibiting PP2A/AKT/mTOR pathways. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2012;113(5):1733–1743. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kumar A, Pandurangan AK, Lu F, et al. Chemopreventive sphingadienes downregulate Wnt signaling via a PP2A/Akt/GSK3β pathway in colon cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33(9):1726–1735. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reya T, Clevers H. Wnt signalling in stem cells and cancer. Nature. 2005;434(7035):843–850. doi: 10.1038/nature03319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bos CL, Kodach LL, Van den Brink GR, et al. Effect of aspirin on the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is mediated via protein phosphatase 2A. Oncogene. 2006;25(49):6447–6456. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bos CL, Diks SH, Hardwick JCH, Walburg KV, Peppelenbosch MP, Richel DJ. Protein phosphatase 2A is required for mesalazine-dependent inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin pathway activity. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(12):2371–2382. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guichard C, Pedruzzi E, Fay M, et al. Dihydroxyphenylethanol induces apoptosis by activating serine/threonine protein phosphatase PP2A and promotes the endoplasmic reticulum stress response in human colon carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(9):1812–1827. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen KF, Pao KC, Su JC, et al. Development of erlotinib derivatives as CIP2A-ablating agents independent of EGFR activity. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 2012;20(20):6144–6153. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dung TD, Day CH, Binh TV, et al. PP2A mediates diosmin p53 activation to block HA22T cell proliferation and tumor growth in xenografted nude mice through PI3K-Akt-MDM2 signaling suppression. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2012;50(5):1802–1810. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dung TD, Chang H-C, Binh TV, et al. Zanthoxylum avicennae extracts inhibit cell proliferation through protein phosphatase 2A activation in HA22T human hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2012;29(6):1045–1052. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bialojan C, Takai A. Inhibitory effect of a marine-sponge toxin, okadaic acid, on protein phosphatases. Specificity and kinetics. Biochemical Journal. 1988;256(1):283–290. doi: 10.1042/bj2560283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zimmerman R, Peng D, Lanz H, et al. PP2A inactivation is a crucial step in triggering apoptin-induced tumor-selective cell killing. Cell Death & Disease. 2012;3(4, article e291) doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Honkanen RE. Cantharidin, another natural toxin that inhibits the activity of serine/threonine protein phosphatases types 1 and 2A. FEBS Letters. 1993;330(3):283–286. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80889-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li W, Chen Z, Zong Y, et al. PP2A inhibitors induce apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cell line PANC-1 through persistent phosphorylation of IKKα and sustained activation of the NF-κB pathway. Cancer Letters. 2011;304(2):117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]