Abstract

Because soy food consumption may influence breast tissue activity, we examined its effect on the presence of epithelial cells in nipple aspirate fluid (NAF). In a randomized, crossover design, 82 premenopausal women completed a high-soy and a low-soy diet for 6 months each, separated by a 1-month washout period. They provided NAF samples at baseline, 6 months, and 13 months during the midluteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Papanicolaou-stained cytology slides (for 33 women at baseline, 24 at low-soy, and 36 at high-soy) were evaluated in women with sufficient NAF. Mixed models evaluated the effect of the high-soy diet on epithelial cytology as compared to baseline and the low-soy diet. At the end of the high-soy diet, cytological class had decreased in 8 (24%) and increased in 3 (9%) women as compared to baseline, whereas the respective values were 3 (14%) and 6 (29%) for the low-soy diet samples (p=0.32). Only the change in subclass indicated a trend in lower cytological class (p=0.06). Contrary to an earlier report, the number of NAF samples with hyperplastic epithelial cells did not increase after a soy intervention in amounts consumed by Asians.

Keywords: Soy foods, isoflavones, nipple aspirate fluid, breast cancer risk, cytology

INTRODUCTION

A number of epidemiologic studies support the hypothesis that soy foods protect against breast cancer, in particular among Asian populations with high intake (1,2). Because of their estrogen-like structure and properties, isoflavones as the active ingredients in soy beans have been the focus of clinical and experimental investigations (3). Depending on dose, isoflavones may act as agonists or antagonists through competitive binding to estrogen receptors, but other mechanisms of actions have also been described (4). Although the findings from randomized trials show little effect on breast cancer risk as assessed by serum estrogens (5) and breast density (6–9), it is possible that isoflavones act directly on breast tissue.

Nipple aspirate fluid (NAF) collection is a non-invasive method to obtain breast fluid and cells, which allow cytologic examination and detection of atypical and malignant cells (10–12). The presence of epithelial cells, in particular atypical cells, has been associated with a higher risk of developing breast cancer (13,14). In previous reports, a soy intervention without a control group found an increase in number of women with hyperplasic epithelial cells (15), but a randomized trial with an isoflavone supplement did not detect an intervention effect on cytologic atypia (16). The objective of the current report was to examine the differences in NAF cytological class among premenopausal women who participated in a dietary intervention that administered soy foods for 6 months (17).

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a randomized, crossover soy intervention consisting of 6 months each on a high-soy and a low-soy diet with a 1 month washout between diets as described previously (17). The study protocol was approved by the Committee on Human Subjects at the University of Hawaii and the Institutional Review Boards at the participating clinics. All participants signed an informed consent form. A Data Safety Monitoring Committee annually reviewed study progress, reasons for drop-outs, and any reported adverse health effects. Interested women were recruited through multiple sources (17). Of 310 interested women, at least 10 µL of NAF, the minimum for participation was obtained from 112 (36%) women. Of these, 96 women were willing and eligible to proceed to randomization; the 48 women in Group A started with the high-soy diet, 2 servings of soy foods per day, while the 48 women in Group B went on the low-soy diet with <3 servings of soy foods per week. A serving was defined as 177 mL soy milk, 126 g tofu, or 23 g soy nuts providing ~25 mg of isoflavones a dose; participants were allowed to choose foods. No additional changes in lifestyle were recommended. A self-administered food frequency questionnaire that assessed usual food intake during the last year was completed by eligible women prior to randomization. As part of monthly contacts, participants reported changes in health status, if any, for monitoring of adverse health effects. Adherence to the intervention strategy was excellent as assessed by 7 unannounced 24-hour dietary recalls and urinary isoflavonoid excretion measured in urine samples collected at baseline and during each diet period (3 samples each) (17).

Sample Collection

NAF samples were collected from each woman at the study visits (baseline, 6 months, and 13 months) planned to occur during the mid-luteal phase based on self-reported information on previous menstruation dates, cycle length, and actual date of next menstruation (17). For NAF collection, a trained staff member demonstrated the collection technique using a FirstCyte© Aspirator, a device similar to a manual breast pump consisting of a 10 or 20 cc syringe attached to a small suction cup (18). The NAF was collected with microcapillary tubes (10, 20, and 50 µL) and the total amount was recorded. The first 20 µL of NAF were pooled in phosphate-buffered saline in a dilution of 1:11, well mixed, aliquoted, and stored at −80° C for sex hormone assays (19). The next 5–20 µL were combined with Shandon Cytospin Collection Fluid to preserve breast cells for cytologic analysis. If more NAF was obtained, it was diluted in buffer again and stored for future assays. For women who produced <20 µL NAF, no cytology samples were available. Of the 82 women who completed the intervention, 36 produced sufficient NAF for cytological evaluation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by cytology statusa

| Characteristic | Cytology | No cytologya | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 36 (44%) | 46 (56%) | ||

| Randomization groupd, N (%) | A | 19 (53%) | 21 (46%) | 0.52 |

| B | 17 (47%) | 25 (54%) | ||

| Ethnicity, N (%) | Caucasian | 21 (58%) | 21 (46%) | 0.18 |

| Asian | 6 (17%) | 16 (35%) | ||

| Other | 9 (25%) | 9 (19%) | ||

| Age at screening (years) | 40.4±6.0 | 38.3±6.1 | 0.12 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.2±5.9 | 25.5±5.3 | 0.56 | |

| Age at menarche (years) | 12.1±1.2 | 12.6±1.5 | 0.12 | |

| Parity, N (%) | Yes | 28 (78%) | 31 (67%) | 0.33 |

| No | 8 (22%) | 15 (33%) | ||

| Age at first child birth (years)c | 27.9±6.8 | 27.7±6.8 | 0.90 | |

| NAF volume, µL | Baseline | 58±49 | 19±16 | <0.0001 |

| Low-soy diet | 51±40 | 10±9 | <0.0001 | |

| High-soy diet | 59±37 | 13±14 | <0.0001 | |

| Dietary intake | ||||

| Isoflavones (mg/day) | Baseline | 2.2±1.9 | 6.3±9.1 | <0.01 |

| Low-soy diet | 3.8±5.8 | 7.6±15.8 | 0.29 | |

| High-soy diet | 65.0±29.5 | 71.3±26.6 | 0.70 | |

| Total fat (g/day) | Baseline | 82.4±51.3 | 76.5±44.8 | 0.53 |

| Low-soy diet | 74.9±26.2 | 77.4±27.8 | 0.09 | |

| High-soy diet | 81.9±25.8 | 72.7±25.4 | 0.67 | |

| Dietary fiber (g/day) | Baseline | 23.7±12.6 | 24.5±16.3 | 0.85 |

| Low-soy diet | 16.7±4.6 | 16.8±6.5 | 0.45 | |

| High-soy diet | 17.3±5.7 | 19.1±8.0 | 0.76 | |

| Urinary isoflavonoid excretion | Baseline | 6.2±12.2 | 4.1±6.0 | 0.80 |

| (nmol/mg creatinine) | Low-soy diet | 3.6±6.8 | 7.6±8.7 | 0.35 |

| High-soy diet | 48.2±30.1 | 66.1±58.1 | <0.01 | |

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation unless otherwise indicated. The “no cytology” category represents women with insufficient NAF volume (≤20 µL) for cytological analysis. Dietary intake was estimated from food frequency questionnaire (baseline) and three unannounced 24-hour dietary recalls administered during each diet period. Urinary isoflavonoid excretion was measured in urine samples collected throughout the study; the mean excretion level across 3 urine samples was presented for each diet period.

P-values for comparison between cytology vs. no cytology used chi-square test or Fisher’s exact text for categorical variables and Student’s t test for continuous variables. Dietary intake of nutrients and urinary isoflavonoid excretion were log-transformed to normalize the distributions.

N=59 for parous women: 31 with no cytology slides, 28 with cytology slides.

Group A: high-soy diet first; Group B: low-soy diet first.

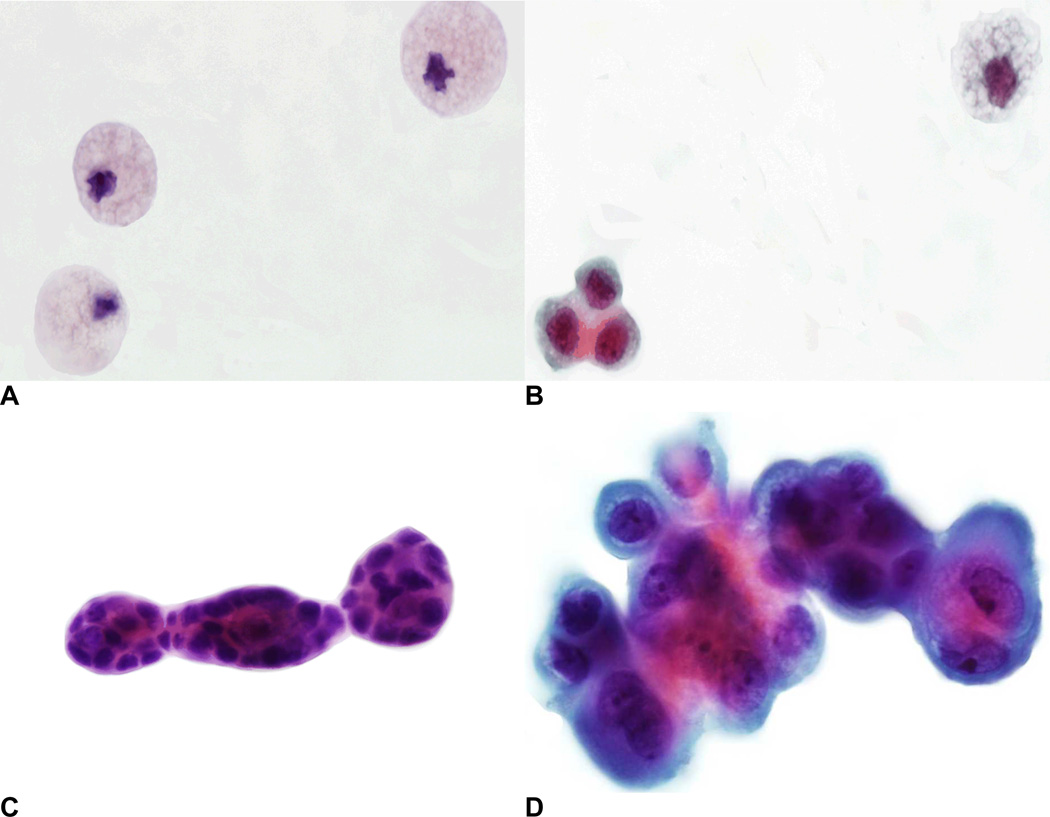

Cytology specimens were stored at 4–8°C for a period of no more than 2 months before slide preparation. Specimens were cytocentrifuged onto as many as 10 glass slides depending on the amount of available fluid. Slides were washed twice in 95% ethanol for 5 minutes each, rehydrated in tap water, and stained by the Papanicolaou method. If available, up to 5 cytology slides for each diet phase were evaluated by an experienced cytopathologist, but a maximum of 5 was chosen to keep the results comparable. At baseline, 5 slides were available for 21 women, 3–4 slides for 9 women, and 3 women had only 1–2 slides. The respective numbers were 15, 6, and 3 for the low-soy diet, and 19, 11, and 6 for the high-soy diet. The remaining slides were stored for future examination. Each specimen was designated as one of the following cytological classes (Figure 1): inadequate (<10) mammary epithelial cells (class I), benign mammary epithelial cells (class II), atypical mammary epithelial cells (class III), and malignant cells present (class IV) (10). The class II and III were further categorized into subclasses a and b: normal epithelial cells (class IIa), hyperplasia without atypia (class IIb), single atypical epithelial cells (class IIIa), and papillary clusters of atypical cells (IIIb).

FIG. 1.

Photomicrographs of cytological specimens (Papanicolaou stain): (A) Class I, foam cells; (B) Class IIa, normal epithelial cells and one foam cell; (C) Class IIb, hyperplasia without atypia; and (D) Class IIIb, papillary clusters of atypical cells (color figure available online).

Statistical Analysis

SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used to perform all statistical analyses with a 2-sided p-value of <0.05 considered statistically significant. Descriptive comparisons of women with and without NAF cytology specimens were conducted using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Student’s t test for continuous variables. We also evaluated, using general linear models (PROC GLM), the differences in mean dietary intake of total fat and dietary fiber during the high-soy vs. low-soy diet to assess the influence of dietary intervention on these nutrients previously linked with breast cancer. We calculated the number of days between NAF collection and the next menstruation and classified them into two categories: midluteal (3–11 days before the next menstruation) or outside that period. To assess the influence of the high-soy diet on NAF cytology as compared to baseline and the low-soy diet, we applied mixed-effects regression (PROC MIXED) models with cytological class as the dependent variable (continuous) and calculated the p-value for the high-soy diet while including time (month 6 or 13) and randomization group (A or B). We also modeled the change in cytological class from baseline to month 6 or 13 and evaluated the interaction between soy diet and randomization group.

RESULTS

The mean NAF volumes for women with and without cytology specimens differed significantly; they were 58±49 vs. 19±16 µL at baseline, 59±37 vs. 13±14 µL at the end of the high-soy diet period, and 51±40 vs. 10±9 µL at the end of the low-soy diet period (Table 1). However, age at screening, reproductive characteristics, body mass index, ethnicity, randomization group, and dietary intake of total fat and dietary fiber were similar. Small differences for dietary isoflavone intake and urinary isoflavonoid excretion were observed; isoflavone intake was lower at baseline (2.2±1.9 vs. 6.3±9.1 mg/day; p < 0.01) and urinary isoflavonoid excretion was lower during high-soy (48.2±30.1 vs. 66.1±58.1 nmol/mg creatinine; p < 0.01) among women with than those without cytology. We also observed no differences in dietary intake of total fat and dietary fiber during the low- vs. high-soy diet across women with or without cytology specimens (data not shown). At baseline, NAF volume was sufficient for 33 women, and at the end of the low-soy and high-soy diet, specimens were available for 24 and 36 women, respectively (Table 2). Thus, 21 women had NAF samples for cytologic evaluation at all 3 time points and 15 women at 2 time points (with one high-soy sample). Of all 93 NAF samples evaluated for cytology, 49 (53%) were collected during the midluteal phase.

Table 2.

Cytology in nipple aspirate fluid samples collected at baseline and at the end of high-soy and low-soy soy dietsa

| Baseline | Low-soy diet |

High-soy diet |

p-valueb |

p-valueb midluteal only |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 33 | 24 | 36 | ||||

| Cytological classification | |||||||

| (1) | Major class | ||||||

| I | Inadequate mammary epithelial cells (<10 epithelial cells) | 16 (49%) | 12 (50%) | 21 (58%) | 0.32 | 0.39 | |

| II | Benign mammary epithelial cells | 13 (39%) | 9 (38%) | 12 (34%) | |||

| III | Atypical mammary epithelial cells | 4 (12%) | 3 (13 %) | 3 (8%) | |||

| IV | Malignant cells present | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | |||

| (2) | Subclass | ||||||

| I | Inadequate mammary epithelial cells (<10 epithelial cells) | 16 (49%) | 12 (50%) | 21 (58%) | 0.06 | 0.15 | |

| IIa | Normal epithelial cells | 9 (27%) | 3 (13%) | 10 (28%) | |||

| IIb | Hyperplasia without atypia | 4 (12%) | 6 (25%) | 2 (6%) | |||

| IIIa | Single atypical epithelial cells | 2 (6%) | 0 (0 %) | 2 (6%) | |||

| IIIb | Papillary clusters of atypical cells | 2 (6%) | 3 (13%) | 1 (3%) | |||

| IV | Malignant cells present | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | |||

| Change in cytological subclass from baselinec | 0.05 | 0.14 | |||||

| No change | --- | 12 (57%) | 22 (67%) | ||||

| Decrease | --- | 3 (14%) | 8 (24%) | ||||

| Increase | --- | 6 (29%) | 3 (9%) | ||||

Data are presented as n (%); percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

p-value was calculated using mixed-effects regression model for the comparison of the high-soy diet vs. baseline and the low-soy diet with adjustment for time (month 6 or 13) and randomization group (A or B) across all or midluteal (N=49) samples.

Change in subclass: decrease=class IIb, III, IIIb to class I,II; increase=class I,II to class IIb, III, IIIb.

Among the 33 women with cytology specimens at baseline, 16 women (49%) were designated as cytological class I, 13 women (39%) as class II, and 4 women (12%) as class III. At the end of the high-soy diet, 21 women (58%) were classified as class I, 12 (34%) as class II, and 3 (8%) as class III. The respective values at the end of the low-soy diet were 12 (50%), 9 (38%), and 3 women (13%). No cytological specimens were designated as class IV. Whereas > 50% of participants remained in the same cytological classes across the study period (p=0.32), a borderline significant difference (p=0.06) was observed at the end of the high-soy diet as compared to baseline and the low-soy diet when subclasses were considered. When an interaction term between soy diet and randomization group was added, this difference became highly significant (p<0.01) indicating that groups A and B responded differently to the dietary intervention. An evaluation of change in cytological class as compared to baseline suggested a trend (p=0.05) towards a lower cytological class. Specifically, a decrease in cytological subclass was seen in 8 women (24%) and an increase in 3 women (9%) at the end of the high-soy diet, whereas, at the end of the low-soy diet, a decrease in 3 women (14%) and an increase in 6 women (29%) occurred. When restricted to midluteal samples, however, the high-soy diet was not associated with changes in cytological class (p=0.14; Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this soy trial among multiethnic premenopausal women, a daily consumption of 2 servings of soy foods for 6-months resulted in a modest trend of a lower cytological class in breast epithelial cells obtained from NAF. Although these findings suggest that regular soy intake at levels commonly seen in Asian countries (20) does not have adverse effects on epithelial breast cells and may even have a beneficial effect on NAF cytology, the small sample size of women for whom cytological specimens were available prohibits any firm conclusions. As we did not observe major changes in dietary fat or fiber intake during the two diet periods, it is unlikely that other nutritional factors that affect NAF cytology (21) are responsible for the small changes in NAF cytology during this trial.

The current study’s findings are in contrast to a previous report, which found an increase from 4.2% to 29.2% of participants with hyperplasic epithelial cells after consuming soy protein isolate (15). However, the study was relatively small and lacked a control group. In a more recent trial with soy supplements, no significant difference in epithelial cell morphology was detected between the study groups (16). A few studies were able to directly examine breast tissue obtained from surgery or pathologic specimens. Women undergoing random fine-needle aspiration (16) who were randomized to a double-blind 6-month intervention of soy isoflavones or placebo detected a larger increase Ki-67 labeling index among pre- than postmenopausal soy-treated women, but the overall effect was not statistically significant. In women scheduled to receive a breast biopsy or to undergo surgery (22,23), the proliferation rate of breast lobular epithelium and pS2 levels in the breast fluid increased indicating an estrogenic stimulus after consuming a soy supplement. In a study using paraffin-embedded blocks from 268 breast cancer patients, hormonal and proliferation markers did not differ by adult soy intake (24).

There is limited evidence whether or not NAF producers have an elevated breast cancer risk. In a follow-up of two large cohorts (13), the risk estimates were 1.6 (95% CI=1.1–2.3) and 1.2 (95% CI=0.8–2.0), respectively, for those with normal cytology in NAF as compared with women who produced no fluid. Two cohorts (14,25) described a 70–90% higher breast cancer risk for women with epithelial cells in NAF, but only epithelial cells that showed hyperplasia or atypia were associated with a significant 2-fold risk (95%CI: 1.1–3.6). These findings imply that the presence or absence of epithelial cells in NAF per se may not constitute an indicator of risk.

Our study had a number of limitations mainly related to the NAF collection process. In addition to the difficulties of accurately measuring the absolute amount of fluid collected, the number of attempts and the amount of time spent to obtain fluid influence the final volume collected at one time, in particular for women who produce large amounts of NAF. Therefore, the volume of NAF used to prepare cytology slides was not consistent across participants and collection times. The NAF volume used to create cytology slides ranged from 5–25 µL depending on the total amount collected. As a result, the number of slides examined per case varied from 1 to 5. Depending on the volume of NAF used to prepare the cytology slides, the slides for some women may have contained no cells although cells were present in the total amount collected and used for lab assays. Unfortunately, this soy trial was not powered for the cytology analysis since NAF volume and estrogens in NAF were the primary outcomes (17,19) and the lack of exact timing in the menstrual cycle may have further biased the results.

On the other hand, this trial had considerable strengths. For a dietary intervention, this trial was relatively long-term, and the randomized crossover design allowed for assessment of between- and within-person effects. The study participants represented several ethnic groups; the soy foods in this study included traditional Asian foods that were administered in comparable amounts (20); the adherence to the dietary protocol was very high; and the drop-out rate was acceptably low, although only 36 out of 82 women who completed the study had sufficient NAF for cytology, and the analysis was based on multiple collections including NAF and urinary isoflavonoid levels (17). To gain insight into breast tissue activity, it would be ideal to examine breast tissue, which is only available for small groups of women with abnormalities who require a biopsy and are supplemented with soy or isoflavones for a short time period before the procedure (22,23). Thus, despite its limitations, NAF is a more feasible method to look at breast cells in healthy women.

In conclusion, while there is widespread concern about possible adverse effects of soy foods (26–28), the results of this study despite its many limitations and in combination with reports from fine needle and tissue biopsy samples (16,22,23), suggest the safety of consuming soy foods in amounts comparable to traditional Asian diets.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Support for this study was obtained by grants from the National Cancer Institute R01 CA 80843 and P30 CA71789 and from the National Center for Research Resources S10 RR020890. The study was registered under clinical trial registration number NCT00513916.

REFERENCES

- 1.Trock BJ, Hilakivi-Clarke L, Clarke R. Meta-analysis of soy intake and breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:459–471. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu AH, Yu MC, Tseng CC, Pike MC. Epidemiology of soy exposures and breast cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:9–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Setchell KD. Phytoestrogens: the biochemistry, physiology, and implications for human health of soy isoflavones. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:1333S–1346S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.6.1333S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes S, Boersma B, Patel R, Kirk M, Darley-Usmar VM, et al. Isoflavonoids and chronic disease: mechanisms of action. Biofactors. 2000;12:209–215. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520120133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hooper L, Ryder JJ, Kurzer MS, Lampe JW, Messina MJ, et al. Effects of soy protein and isoflavones on circulating hormone concentrations in pre- and post-menopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:423–440. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maskarinec G, Takata Y, Franke AA, Williams AE, Murphy SP. A 2-year soy intervention in premenopausal women does not change mammographic densities. J Nutr. 2004;134:3089–3094. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.11.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maskarinec G, Verheus M, Tice J. Epidemiologic studies of isoflavones & mammographic density. Nutrients. 2010;2:35–48. doi: 10.3390/nu2010035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maskarinec G, Verheus M, Steinberg FM, Amato P, Cramer MK, et al. Various doses of soy isoflavones do not modify mammographic density in postmenopausal women. J Nutr. 2009;139:981–986. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.102913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hooper L, Madhavan G, Tice JA, Leinster SJ, Cassidy A. Effects of isoflavones on breast density in pre- and post-menopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16:745–760. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sauter ER, Ross E, Daly M, Klein-Szanto A, Engstrom PF, et al. Nipple aspirate fluid: a promising non-invasive method to identify cellular markers of breast cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 1997;76:494–501. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishnamurthy S, Sneige N, Thompson PA, Marcy SM, Singletary SE, et al. Nipple aspirate fluid cytology in breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;99:97–104. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sauter ER, Ehya H, Babb J, Diamandis E, Daly M, et al. Biological markers of risk in nipple aspirate fluid are associated with residual cancer and tumour size. Br J Cancer. 1999;81:1222–1227. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wrensch MR, Petrakis NL, Miike R, King EB, Chew K, et al. Breast cancer risk in women with abnormal cytology in nipple aspirates of breast fluid. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1791–1798. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.23.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buehring GC, Letscher A, McGirr KM, Khandhar S, Che LH, et al. Presence of epithelial cells in nipple aspirate fluid is associated with subsequent breast cancer: a 25-year prospective study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;98:63–70. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrakis NL, Barnes S, King EB, Lowenstein J, Wiencke J, et al. Stimulatory influence of soy protein isolate on breast secretion in pre-and postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5:785–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan SA, Chatterton RT, Michel N, Bryk M, Lee O, et al. Soy isoflavone supplementation for breast cancer risk reduction: a randomized phase II trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:309–319. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maskarinec G, Morimoto Y, Conroy SM, Pagano IS, Franke AA. The volume of nipple aspirate fluid is not affected by 6 months of treatment with soy foods in premenopausal women. J Nutr. 2011;141:626–630. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.133769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrakis NL. Nipple aspirate fluid in epidemiologic studies of breast disease. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:188–195. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maskarinec G, Ollberding NJ, Conroy SM, Morimoto Y, Pagano IS, et al. Estrogen levels in nipple aspirate fluid and serum during a randomized soy trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1815–1821. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Messina M, Nagata C, Wu AH. Estimated Asian adult soy protein and isoflavone intakes. Nutr Cancer. 2006;55:1–12. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5501_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato I, Ren J, Visscher DW, Djuric Z. Nutritional predictors for cellular nipple aspirate fluid: Nutrition and Breast Health Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;97:33–39. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hargreaves DF, Potten CS, Harding C, Shaw LE, Morton MS, et al. Two-week dietary soy supplementation has an estrogenic effect on normal premenopausal breast. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:4017–4024. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.11.6152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McMichael-Phillips DF, Harding C, Morton M, Roberts SA, Howell A, et al. Effects of soy-protein supplementation on epithelial proliferation in the histologically normal human breast. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:1431S–1435S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.6.1431S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maskarinec G, Erber E, Verheus M, Hernandez BY, Killeen J, et al. Soy consumption and histopathologic markers in breast tissue using tissue microarrays. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61:708–716. doi: 10.1080/01635580902913047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baltzell KA, Moghadassi M, Rice T, Sison JD, Wrensch M. Epithelial cells in nipple aspirate fluid and subsequent breast cancer risk: a historic prospective study. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messina M, Caskill-Stevens W, Lampe JW. Addressing the soy and breast cancer relationship: review, commentary, and workshop proceedings. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1275–1284. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Messina MJ, Loprinzi CL. Soy for breast cancer survivors: a critical review of the literature. J Nutr. 2001;131:3095S–3108S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.3095S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hilakivi-Clarke L, Andrade JE, Helferich W. Is Soy Consumption Good or Bad for the Breast? J Nutr. 2010 doi: 10.3945/jn.110.124230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]