Abstract

Objective

Genetic epilepsies and many other human genetic diseases display phenotypic heterogeneity, often for unknown reasons. Disease severity associated with nonsense mutations is dependent partially on mutation gene location and resulting efficiency of nonsense mediated mRNA decay (NMD) to eliminate potentially toxic proteins. Nonsense mutations in the last exon do not activate NMD, thus producing truncated proteins. We compared the protein metabolism and the impact on channel biogenesis, function and cellular homeostasis of truncated γ2 subunits produced by GABRG2 nonsense mutations associated with epilepsy of different severities and by a nonsense mutation in the last exon unassociated with epilepsy.

Methods

GABAA receptor subunits were coexpressed in nonneuronal cells and neurons. NMD was studied using minigenes that support NMD. Protein degradation rates were determined using 35S radiolabeling pulse chase. Channel function was determined by whole cell recordings while subunits trafficking and cellular toxicity were determined using flow cytometry, immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry.

Results

Although all GABRG2 nonsense mutations resulted in loss of γ2 subunit surface expression, the truncated subunits had different degradation rates and stabilities, suppression of wildtype subunit biogenesis and function, amounts of conjugation with polyubiquitin and endoplasmic reticulum stress levels.

Interpretation

We compared molecular phenotypes of GABRG2 nonsense mutations. The findings suggest that despite the common loss of mutant allele function, each mutation produced different intracellular levels of trafficking-deficient subunits. The concentration-dependent suppression of wildtype channel function and cellular disturbance resulting from differences in mutant subunit metabolism may contribute to associated epilepsy severities and by implication to phenotypic heterogeneity in many inherited human diseases.

Keywords: GABAA receptors, epilepsy phenotype, γ2 subunit truncation mutation, loss of function, protein degradation, ER stress

Introduction

Mutations in GABAA receptor α1, β3 and γ2 subunits are associated with genetic epilepsy syndromes that vary from the relatively benign childhood absence epilepsy (CAE) syndrome, which remits with age, to more severe epilepsy syndromes associated with intellectual disability such as Dravet Syndrome 1–5. Among these mutations, those in γ2 subunits are most frequently associated with epilepsy. This is not surprising given the wide expression and critical roles of γ2 subunits in receptor composition 6, channel properties 7 and receptor targeting to and maintenance of synapses 8,9.

W429X is a recently reported nonsense mutation in the last exon of GABRG2 and in the M3-M4 cytoplasmic loop of γ2 subunits (Figure 1A, B) that is associated with febrile seizures and generalized tonic-clonic seizures 10. Q390X is another nonsense mutation in a location similar to that of W429X (Figure 1A, B), but that is associated with epilepsies with a more severe phenotype including Dravet syndrome 11. We reported that the Q390X mutation did not activate nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD), and that nonfunctional, but stable, mutant γ2(Q390X) subunits were produced and retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The γ2(Q390X) subunits had dominant negative effects on the biogenesis and trafficking of wildtype subunits 12 and were more prone to form intracellular high molecular weight complexes than were wildtype γ2 subunits 13. The molecular pathophysiology of the W429X mutation is unknown, and it is not clear why the phenotype produced by the W429X mutation is milder than that produced by the Q390X mutation since neither mutation should activate NMD and should produce similar truncated γ2 subunits. It is also unknown why loss of one γ2 allele function in heterozygous GABRG2 knockout mice with no mutant γ2 subunit protein detected only displayed hyperanxiety and were reportedly seizure free 14.

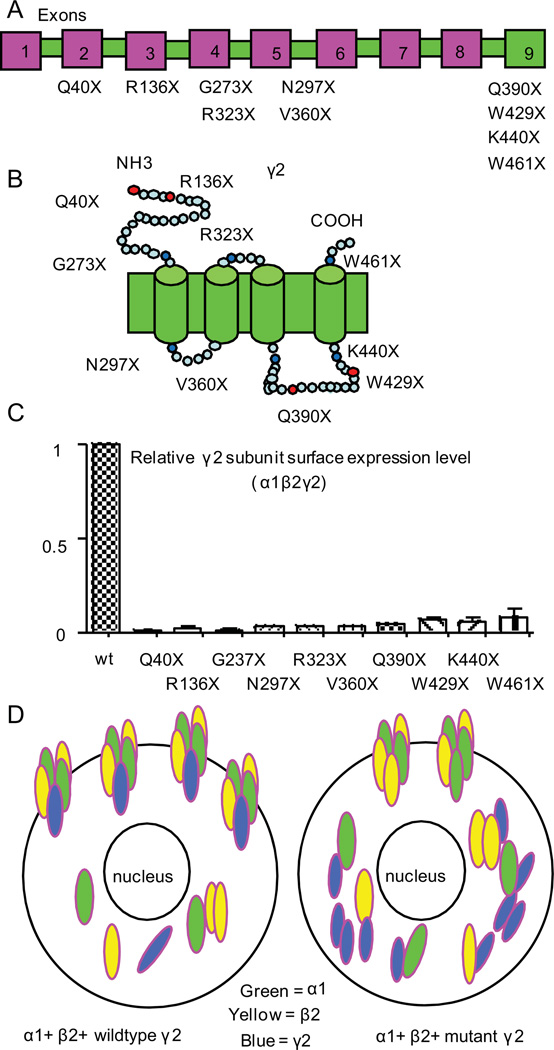

Figure 1. All GABRG2 nonsense mutations produce nonfunctional γ2 subunits with minimal surface expression.

(A) Schematic presentation of human GABRG2 nonsense mutations in exons 1–8 that are sensitive to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) or in exon 9 (the last exon) that are insensitive to NMD. (B) Schematic presentation of γ2 subunit topology and the locations of multiple subunit truncation mutations. The blue dots represent relative locations of the γ2 subunit mutations unrelated to epilepsy, and the red dots indicate mutations associated with epilepsy. (C) When coexpressed with α1 and β2 subunits, the relative surface level of each truncated γ2 subunit was normalized to that obtained with wildtype γ2 subunit. The data were pooled from multiple experiments. (D) The schematic presentation illustrates that when coexpressed with α1 and β2 subunits, the wildtype γ2 subunits in (C) were present on the cell surface as α1β2γ2 receptors while only α1β2 receptors were formed and present on the cell surface in the presence of the truncated γ2 subunits that were retained intracellularly.

To explore this, we expressed multiple truncated γ2 subunits produced by nonsense mutations in GABRG2 exons other than the last exon (Q40X, R136X, G273X, N297X, R323X and V360X) and in the last GABRG2 exon (Q390X, W429X, K440X and W461X) to determine if truncated γ2 subunits of varying lengths had similar or different effects on receptor biogenesis or functional properties. We found that none of the truncated γ2 subunits had significant surface expression and thus all were nonfunctional. However, when we compared three representative truncations in the last GABRG2 exon (Q390X, W429X, W461X), the truncated γ2 subunits differed in stability and degradation rates, amounts of subunit aggregation and extent of suppression of the function of wildtype partnering subunits despite similar mRNA amounts. Thus the effects produced by these three truncated γ2 subunits on GABAergic inhibition should differ, and the severity of the resultant epilepsy syndromes should be correspondingly different that should not depend on NMD efficiency since they are all in the last exon.

Materials and Methods

Expression vectors with GABAA receptor subunits

The cDNAs encoding human α1, β2, γ2 and FLAG- and HA-tagged GABAA receptor subunits (e.g. γ2FLAG, α1FLAG or γ2HA) and γ2 subunit minigenes in pcDNA(3.1) vector with Cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter were as described previously 12,13. HA-tagged polyubiquitin (ubiquitinHA) was kindly provided by Dr. Robert Coffey (Vanderbilt University Medical Center) and is the same as described in the previous study 15. All the truncation mutations were generated with the method as previously described 12. The short form of the γ2 subunit was used in this study, and numbering of γ2 subunit amino acids was based on the immature peptide that includes the 39 amino acids of the signal peptide.

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293T and human L929 cells were cultured with the same condition as described 12. The mouse L929 cells was kindly provided by Dr. Terry Dermody (Vanderbilt University Medical Center) and maintained in culture medium as previously described 16. Rat cortical neurons were prepared as previously described 13.

Electrophysiology, confocal microscopy, [35S] radiolabeling metabolic pulse-chase assays and flow cytometry

Experiments with lifted whole cell recordings, confocal microscopy, [35S] radiolabeling metabolic pulse-chase assays and flow cytometry were carried out based on the protocols from previous studies 13,17.

Mice

The GABRG2 knockout (KO) mouse line14,18 was kindly provided by Dr. Luscher (Penn State Univ) and the GABRG2(Q390X) knockin (KI) mouse line was generated by University Connecticut Health Center. The mice used in this study were in a C57BL/129 mixed background.

Data analysis

Macroscopic currents were low pass filtered at 2 kHz, digitized at 10 kHz, and analyzed using the pClamp9 software suite (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). Numerical data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Proteins were quantified by ChemiImager AlphaEaseFC software and data were normalized to either wildtype subunit proteins or loading controls. Pulse-chase experiments were quantified by using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Fluorescence intensities from confocal microscopy experiments were determined using MetaMorph imaging software and the measurements were modified from previous description 13,17. Statistical significance, using Student’s unpaired t test (GraphPad Prism, La Jolla, CA), was taken as p < 0.05.

Results

Loss of function is a common phenomenon for all nonsense mutations in GABAA receptor γ2 subunits

Nonsense mutations in early exons usually result in mRNA degradation by NMD and thus minimal intracellular truncated protein. Nonsense mutations in the last exon or 50–55 nt from the last exon-exon junction do not activate NMD and often produce nonfunctional, truncated proteins that are retained in the ER. Thus independent of mutation location the truncated proteins produced by nonsense mutations have minimal cell surface expression. We compared the surface expression of multiple epilepsy-related (Q40X, R136X, Q390X, W429X) and epilepsy-unrelated (G273X, N297X, R323X, V360X, K440X and W461X) GABRG2 nonsense mutations in early and last exons that produce truncation of GABAA receptor γ2 subunits (Figure 1A, B). Using flow cytometry we determined the surface expression of the wildtype and mutant γ2 subunits in HEK293T cells cotransfected with α1, β2 and γ2 subunit cDNAs (Figure 1C). Compared with wildtype γ2 subunits, all of the nonsense mutations resulted in significant loss of surface γ2 subunit expression due to ER retention (Figure 1C, D), consistent with loss of function as a common defect among all the γ2 subunit truncation mutations.

Similar amounts of mRNA, but different steady-state total protein levels, were present with γ2(Q390X),γ2(W429X) and γ2(W461X) subunit due to different protein degradation rates

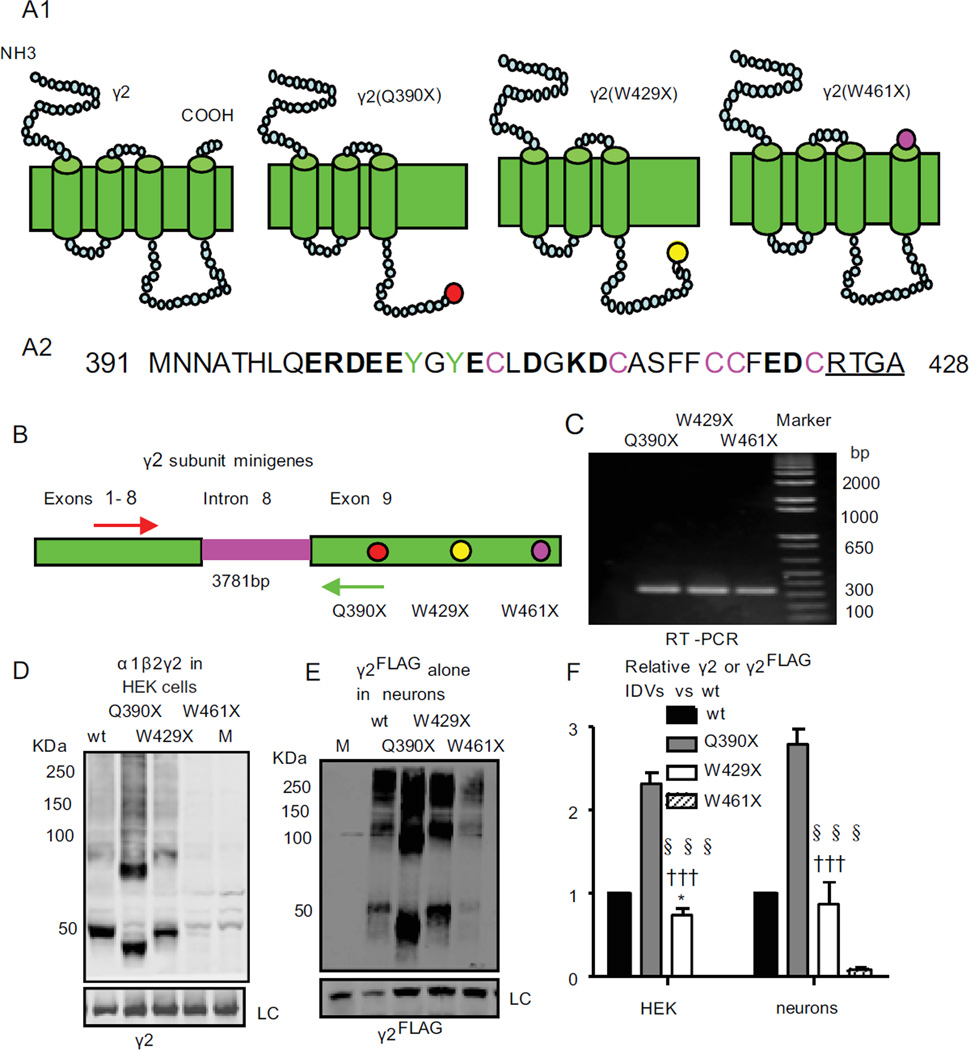

We focused on three mutations in the last GABRG2 exon that should produce truncated γ2 subunits (Figure 2A). We expressed NMD-sensitive wildtype and mutant γ2 subunit minigenes as in a previous study 12 (Figure 2B), but none of them activated NMD as evidenced by similar amount of mRNA (Figure 2C). Surprisingly however, different amounts of mutant proteins were detected in both HEK293T cells (1 for γ2, 2.31 ± 0.14 for γ2(Q390X) and 0.76 ± 0.06 for γ2(W429X) subunits) and in rat cortical neurons (1 for γ2FLAG, 2.79± 0.18 for γ2(Q390X)FLAG and 0.89± 0.25 for γ2(W429X)FLAG subunits in neurons) (Figure 2D–F). Also unexpectedly, γ2(W461X) subunits were almost undetectable in both HEK293T cells and neurons.

Figure 2. GABRG2 subunits with different truncation mutations in the last exon had similar mRNA levels but different steady-state protein levels.

(A1) Schematic topologies of wildtype and mutant γ2 subunits are presented. The dots represent the mutation locations, Q390X (red dot), W429X (yellow dot) and W461X (pink dot). (A2) These 39 amino acids were absent in the M3-M4 loop of the γ2(Q390X) subunit, but present in that of the γ2(W429X) subunit. The segment contains charged residues (bold), palmitoylation sites (pink), tyrosine phosphorylation sites (green) and four residues of the GABAA receptor binding protein (GABARAP) binding sequences (underlined). (B, C) γ2 subunit intron 8 minigenes were constructed by including intron 8 between exons 8 and 9 in γ2 subunit cDNA constructs and were expressed in HEK293T cells. For PCR, primers in flanking exons 7 and 9 (arrows) were used. (D–E) HEK293T cells or rat cortical neurons were cotransfected with α1, β2 and γ2, γ2(Q390X), γ2(W429X) or γ2(W461X) subunits or γ2FLAG, γ2(Q390X)FLAG, γ2(W429X)FLAG or γ2(W461X)FLAG subunits alone or the empty vector pcDNA (M) and then maintained in culture for 2 or 8 days. Total γ2 or immunoprecipitated γ2FLAG subunits were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted by anti-γ2 (D) or anti-FLAG (E) antibody. LC stands for loading control. Individual wildtype γ2 or γ2FLAG subunits were predicted to be 55 KDa and migrated at about 50 KDa, and individual native or FLAG-tagged truncated mutant γ2(Q390X), γ2(W429X) and γ2(W461X) subunits migrated at lower molecular masses predicted to be about 40 KDa, 44.8 KDa and 49 KDa, respectively. (F) Total mutant subunit band IDVs were normalized to the wildtype g2 or g2FLAG subunits (* < 0.05 vs wt; ††† p < 0.001 vs Q390X; §§§ p < 0.001 vs W461X).

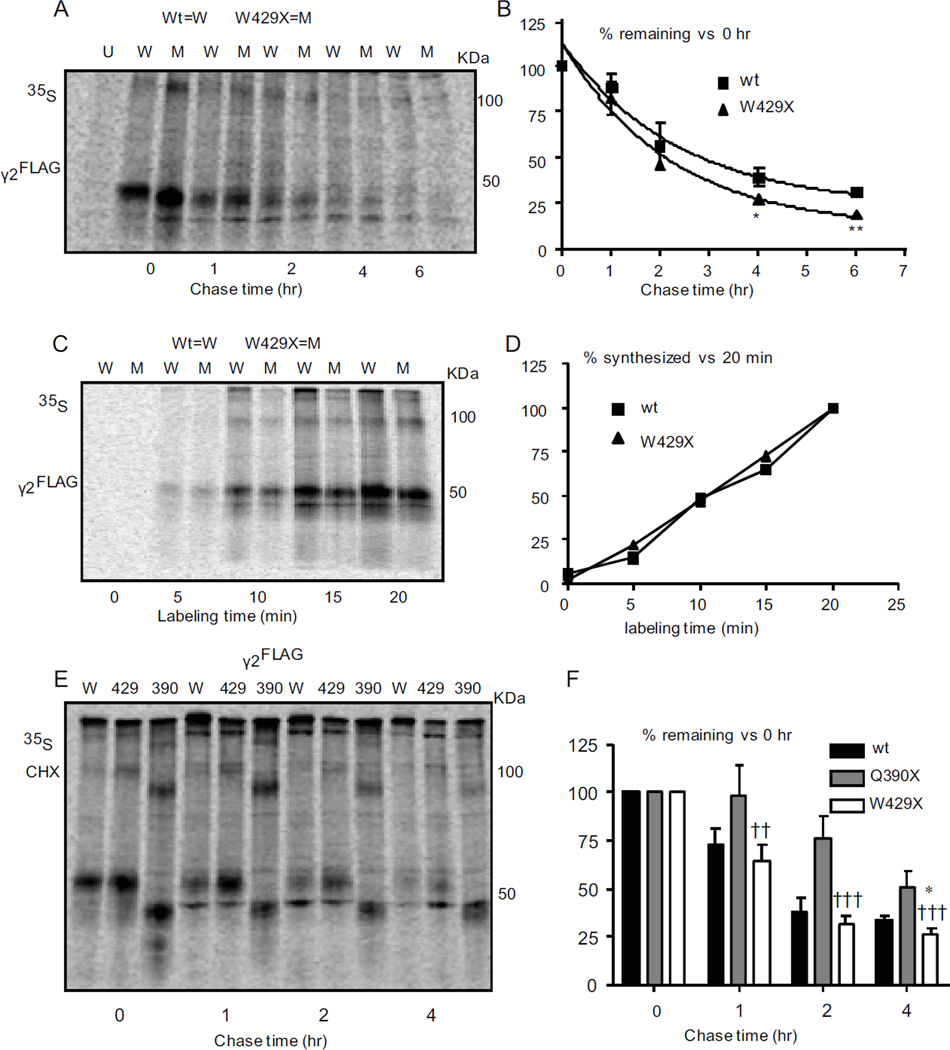

Since expression of the three mutant subunits resulted in markedly different levels of intracellular subunit proteins, we determined the degradation and synthesis rates of the mutant subunits using the [35S] methionine radio-labeling pulse-chase technique. We found the half life of γ2(W429X) subunits was 91.7 min while that of wildtype γ2 subunits was 106.5 min (Figure 3A, B). The half life of γ2(Q390X)FLAG subunits has been previously reported to be ∼4 hr 13. The synthesis rates of wildtype γ2 and mutant γ2(W429X) and γ2(Q390X)FLAG 13 subunits were the same (Figure 3C, D). The differences in degradation rates among subunits (γ2(W461X)FLAG >> γ2(W429X)FLAG > γ2FLAG >> γ2(Q390X)FLAG) subunits thus resulted in different steady-state amounts of high molecular mass γ2 subunit complexes as well as single subunits (γ2(Q390X)FLAG >> γ2FLAG > γ2(W429X)FLAG >> γ2(W461X)FLAG subunits) (Figure 3E, F).

Figure 3. The truncated g2 subunits had different protein degradation rates.

(A, B) [35S] pulse labeled untransfected cells (U) or cells transfected with wildtype γ2FLAG (W) or mutant γ2(W429X)FLAG (M) subunits were lysed, immunopurified using anti-FLAG beads and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. After 20 min of labeling, cells were chased for the indicated times. The percent radioactivity at each chase time point relative to the amount at time 0 for either wildtype or mutant subunits (n = 5) were plotted. (C, D) Cells expressing γ2FLAG or g2(W429X)FLAG subunits were pulse-labeled, lysed and analyzed by SDS-PAGE after immunopurification. The percent radioactivity incorporated during subunit synthesis was plotted by normalizing to the value obtained at 20 min for either wildtype or mutant subunits at each time point (n = 4). (E, F) Cells transfected with γ2FLAG (W), γ2(W429X)FLAG (429) or γ2(Q390X)FLAG (390) subunits were [35S] pulse labeled for 20 min and then chased for 0, 1, 2 and 4 hr. Cycloheximide (CHX) (100 µg/ml) was added in the chase medium to block protein synthesis. The percent radioactivity at each time point relative to the amounts of radioactivity measured at time 0 was plotted for either wildtype or mutant subunits (n = 4). In A–F, both the 100 and 50 KDa bands were included. (In B and F, *< 0.05,**p < 0.01 vs wt; ††† p < 0.001 vs Q390X).

The epilepsy truncation mutations had reduced peak currents due to expression of α1β2 rather than α1β2γ2 receptors

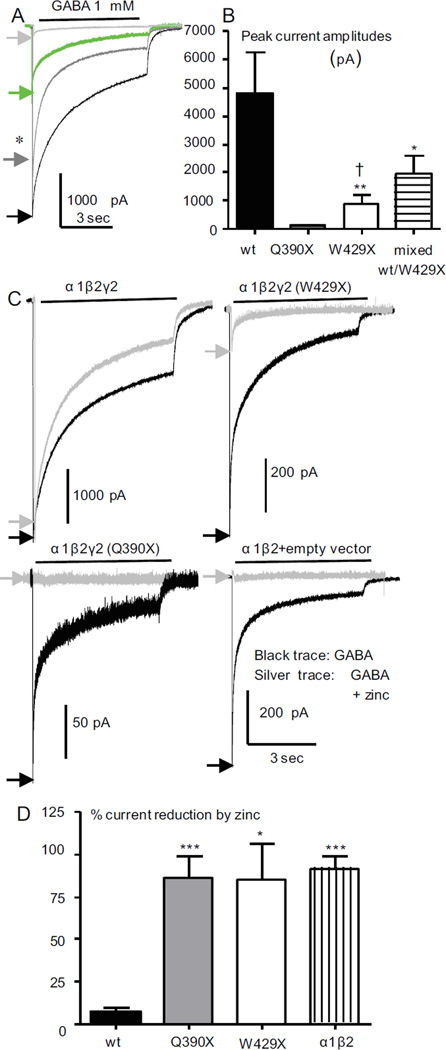

We compared the peak current amplitude and zinc sensitivity of currents recorded from cells coexpressing α1 and β2 subunits with γ2, γ2(Q390X) or γ2(W429X) subunits or with mixed γ2/γ2(W429X) subunits. The peak current from cells expressing mixed γ2/γ2(W429X) subunits (1937 ± 656.9, n = 13) was larger than from those expressing γ2(W429X) (876.9 ± 311.3, n = 10) or α1β2γ2(Q390X) (102.2 ± 35.1, n = 8) subunits but was smaller than recorded from cells expressing wildtype γ2 subunits (4832 ± 1437, n = 7) (Figure 4A, B). Compared to currents from cells expressing wildtype γ2 subunits, currents recorded from cells expressing mutant γ2 subunits had enhanced zinc sensitivity, suggesting surface expression of α1β2 receptors (Figures 1D; 4C, D).

Figure 4. Currents recorded from cells coexpressing α1 and β2 with truncated γ2 subunits had reduced peak current amplitudes and were more sensitive to zinc inhibition.

(A) GABAA receptor currents were obtained with application of 1 mM GABA for 6 sec from HEK293T cells coexpressing α1 and β2 subunits with wildtype γ2 (1:1:1 cDNA ratio; black trace), mixed γ2/γ2(W429X) (1:1:0.5:0.5 cDNA ratio; gray trace with star), mutant γ2(W429X) (1:1:1 cDNA ratio, green trace) or mutant γ2(Q390X) (1:1:1 cDNA ratio, silver trace) subunits. (B) The amplitudes of GABAA receptor currents from (A) were plotted. Values were mean ± SEM (n = 7–13 patches from 6 different transfections) (* p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 vs wt, †p < 0.05 vs Q390X). (C) GABAA receptor currents were obtained with application of 1 mM GABA for 6 sec or with coapplication of 1 mM GABA and 10 µM zinc after preapplication of 10 µM zinc for 6 sec. (D) The percent reduction of peak amplitudes of GABAA receptor currents with coapplication of GABA and zinc compared with application of GABA alone were plotted. (*p < 0.05***p < 0.001 vs wt).

When coexpressed with α1 and β2 subunits, truncated mutant γ2 subunits had primarily immature glycosylation and were not trafficked to the cell surface

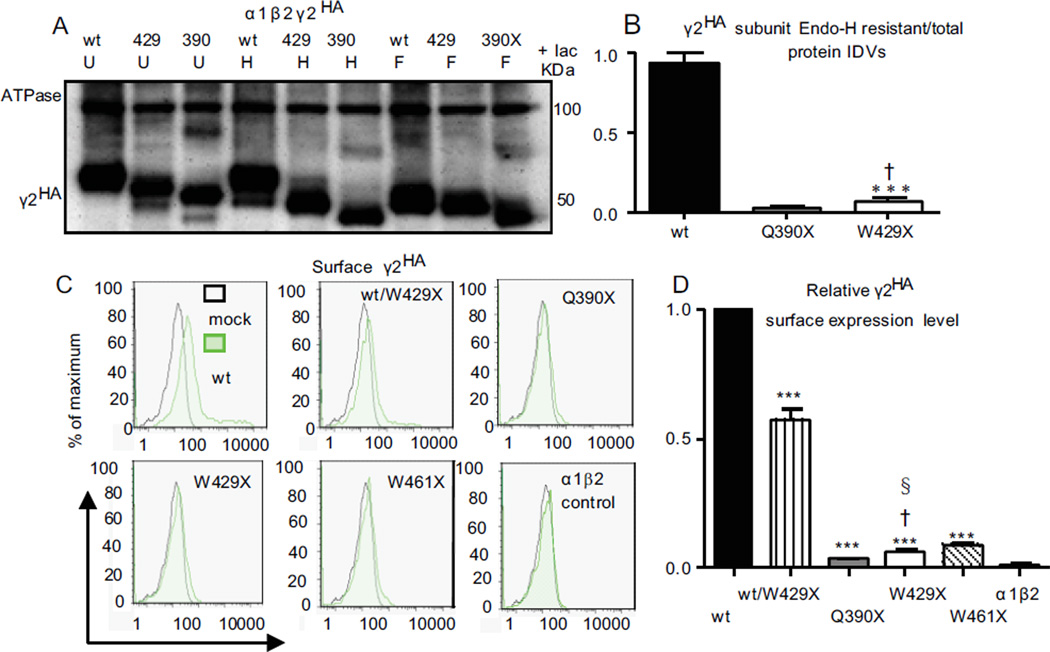

We determined glycosylation of wildtype and mutant γ2 subunits with Endo-H or PNGase F treatment when coexpressed with α1 and β2 subunits 12. The majority of wildtype γ2HA subunits (0.93 ± 0.07, n = 4) were insensitive to Endo-H digestion, consistent with mature glycosylation and trafficking to and beyond the Golgi apparatus. In contrast, mutant γ2(W429X)HA (0.07 ± 0.03, n = 4) and γ2(Q390X)HA (0.03 ± 0.01, n = 4) subunits had minimal resistance to Endo-H treatment (Figure 5B), consistent with retention in the ER and failure to forward traffick. The portion of γ2(W429X)HA subunits resistant to Endo-H digestion was greater than that of γ2(Q390X)HA subunits. Consistent with the glycosylation patterns, wildtype γ2 subunits had substantial surface expression but mutant γ2 subunits all had minimal surface expression (3.5% - 8.8% of wildtype subunit levels) (Figure 5C, D).

Figure 5. Truncated γ2 subunits had minimal surface expression due to ER retention.

(A) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with α1 and β2 subunits and γ2HA (wt), γ2(Q390X)HA (390), or γ2(W429X)HA (429) subunits. The cells were treated with lactacystin (lac, 10 µM) for 6 hr before harvest. Total lysates of the HEK293T cells were undigested (U) or digested (H) with Endo-H or PNGase-F (F) followed by SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-HA antibody. (B) The protein bands insensitive to Endo-H were quantified and presented as a fraction of their total undigested bands (50 KDa + 100 KDa). (C) The flow cytometry histograms depict surface HA levels detected with HA-Alexa 647 with coexpression of γ2HA, γ2HA/γ2(W429X)HA, γ2(Q390X)HA, γ2(W429X)HA, or γ2(W461X)HA subunits or empty vector (α1β2 control) with α1 and β2 subunits. (D) The relative fluorescence intensities of HA signals from cells expressing the mutant γ2HA subunits or empty vector were normalized to those from wildtype γ2HA subunits. In B and D, ***p < 0.001 vs wt; †vs Q390X, § p < 0.05 vs W461X.

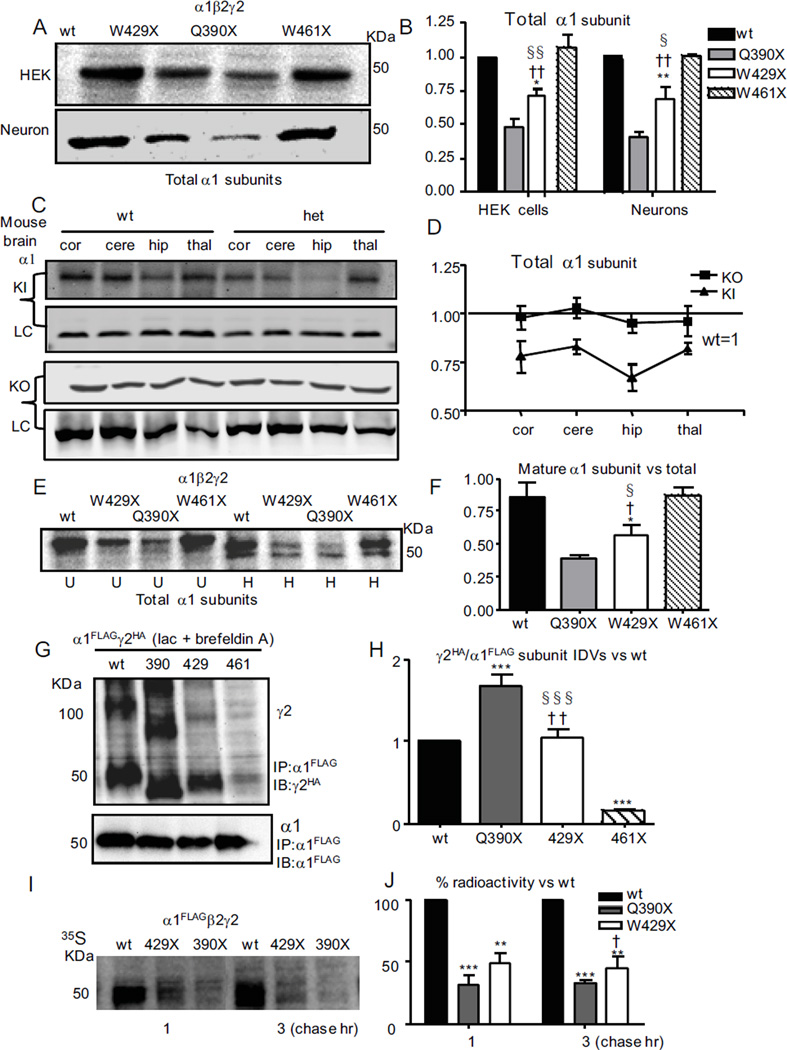

Truncated γ2 subunits reduced total expression and maturation of wildtype α1 and β2 subunits in a concentration-dependent manner

Since the mutant subunits were primarily retained in the ER, we determined their impact on the biogenesis of wildtype subunits. Mutant γ2(Q390X) and γ2(W429X), but not γ2(W461X), subunits reduced total α1 subunit expression in both transfected HEK293T cells and mouse cortical neurons in cell culture (Figure 6A, B). A similar α1 subunit reduction was observed in the GABRG2(Q390X) KI, but not in the GABRG2 KO, mouse brains (Figure 6C, D). We also determined the glycosylation pattern of α1 subunits in the presence of mutant γ2 subunits. Compared with the wildtype subunits, the α1 subunits had reduced mature glycosylation when coexpressed with γ2(Q390X) and γ2(W429X), but not with γ2(W461X), subunits (Figure 6E, F), consistent with a dominant negative effect of the mutant γ2 subunits. The differentially reduced surface expression and glycosylation maturation of α1 subunits was likely due to a differential oligomerization of α1 and mutant γ2 subunits (Figure 6G, H). [35S] radiolabeling pulse chase indicated that substantial degradation of α1 subunits occurred within 1 hr of onset of synthesis (Figure 6I, J). The differential α1 subunit suppression by mutant γ2 subunits was likely due to the different steady-state levels of each mutant subunit (Figure 2D,E,F), with higher steady-state amounts of the mutant γ2 subunits resulting in lower surface α1 subunit expression (Figure 7A, B). This notion was further supported by the fact that increasing mutant γ2 subunits progressively diminished the surface and total expression of mutant more extensively than wildtype α1 subunits (Figure 7C1, C2).

Figure 6. Total α1 subunit levels differed when coexpressed with truncated γ2 subunits due to oligomerization with γ2 subunits and ER retention.

(A) Total lysates of HEK293T cells or rat cortical neurons expressing human α1 and β2 and γ2 subunits were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted by anti-α1 (BD24) antibody. (B) Total α1 subunit protein IDVs were normalized to the α1 subunit of wildtype receptors. (C) Total lysates from cerebral cortex (cor), cerebellum (cere), hippocampus (hip) and thalamus (thal) from new born heterozygous (het) GABRG2 knockout (KO) and GABRG2(Q390X) knockin (KI) mice and their wildtype littermates (wt) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted by anti- mouse α1 antibody. LC stands for loading control. (D) Total α1 subunit protein IDVs from both KO and KI mice were normalized to the α1 subunit of their wildtype littermates (n = 4). (E) Total lysates of HEK cells expressing α1β2γ2 receptors were either undigested (U) or digested (H) with Endo-H and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (F) Total undigested α1 subunit protein IDVs were normalized to their internal control Na+/K+ ATPase IDVs (n = 5). The fractions of Endo-H digested α1 subunits were expressed as a ratio of the 48.4 KDa band (upper bands of H in E) over 48.4 plus 46 KDa bands (lower bands of H in E). (G) HEK293T cells expressing α1FLAG and γ2HA subunits were treated with lactacystin (lac, 10 µM) for 6 hours and brefeldin A (0.5 µg/ml) 36 hours before harvest. The subunits were pulled down with α1FLAG subunits and immunoblotted for γ2HA and α1FLAG subunits. (H) The ratios of the total amount of mutant γ2HA to α1FLAG subunits were normalized to the ratio of wildtype γ2HA to α1FLAG subunits. (I) HEK293T cells containing 35S methionine radio-labeled wildtype or mutant α1FLAGβ2γ2 subunits were chased and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (J) The radioactivities of the α1FLAG subunits were normalized to α1FLAG subunits with coexpression of α1FLAGβ2γ2 for each chase time. In B, F, H ,J (*p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001 vs wt; †p < 0.05; †† p < 0.01 vs Q390X, § p < 0.05; §§ p < 0.01, §§§ p < 0.001 vs W461X).

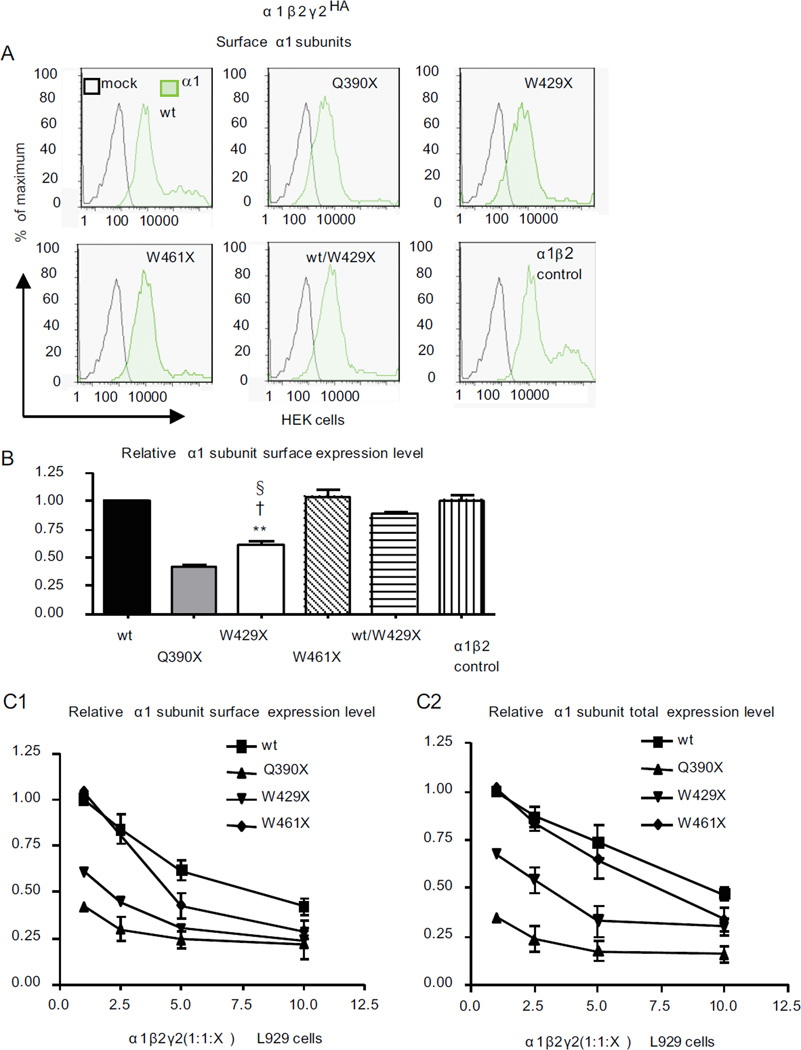

Figure 7. Surface levels of α1 subunits coexpressed with β2 and γ2 subunits were reduced in a trafficking-deficient γ2 subunit concentration-dependent manner.

(A) The flow cytometry histograms depict surface α1 subunit expression levels on HEK293T cells coexpressing the wildtype or mutant α1β2γ2HA subunits. α1 subunits were detected by fluorescently conjugated anti-human α1 antibody (α1–Alexa Fluor-647). (B) The relative fluorescence intensity of α1 subunit signals was normalized to the wildtype α1β2γ2HA receptors (wt) (**p < 0.01 vs wt; †p < 0.05 vs Q390X, § p < 0.05 vs W461X). (C) Human L929 cells were cotransfected with α1β2 subunits and wildtype or mutant γ2 subunits at 1:1:1, 1:1:2.5, 1:1:5, 1:1:10 cDNA ratios. The total amounts of cDNA (12 µg) were equalized by adding empty vector. Both surface (C1) and total (C2) α1 subunits were labeled with α1–Alexa Fluor-647. The relative fluorescence intensities of α1 subunits were normalized to intensities obtained with the wildtype 1:1:1 condition, arbitrarily taken as 1.

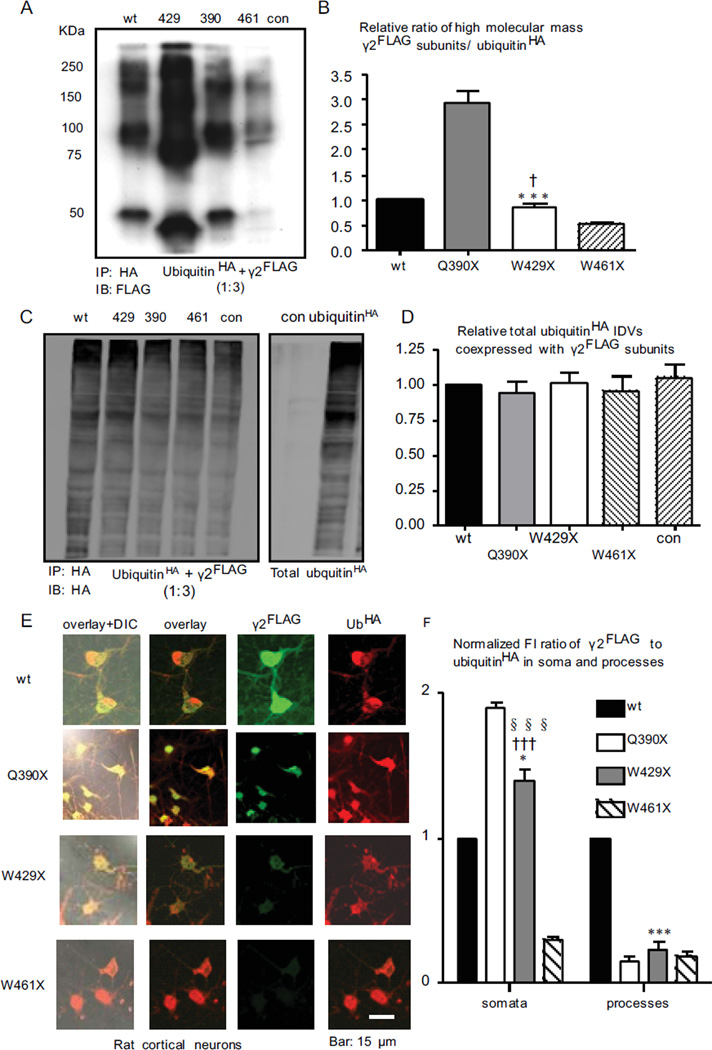

Mutant γ2 subunits had different amounts of high molecular mass protein complexes that were conjugated with ubiquitin

Our previous work demonstrated that γ2(Q390X) subunits were subject to ubiquitin-proteasome degradation 19,20. We demonstrated that in the cells coexpressing γ2FLAG subunits with ubiquitinHA, mutant γ2 subunits were differentially conjugated with polyubiquitin when pulled down with HA beads (Figure 8A, B). There was a denser high molecular mass protein complex for mutant γ2(Q390X)FLAG subunits (2.96 ± 0.21, n = 5) than for wildtype (taken as 1, n = 5), γ2(W429X)FLAG (0.87 ± 0.15, n = 5) or γ2(W461X)FLAG subunits (0.53 ± 0.03, n = 5) (Figure 8B) while the total amount of polyubiquitin was unchanged in each condition (Figure 8C, D). Mutant γ2(Q390X)FLAG and γ2(W429X)FLAG subunits also had increased conjugation with polyubiquitin in the neuronal somata (Figure 8E, F).

Figure 8. Polyubiquitin was conjugated with different amounts of truncated γ2 subunits in different mutations.

(A–D) Total lysates from HEK293T cells expressing HA-tagged polyubiquitin (ubiquitinHA) and γ2FLAG subunits at a cDNA ratio of 1:3 were immunoprecipitated with HA beads and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG antibody (A) while ubiquitinHA from A (C, left panel) or from total lysates of cells expressing empty vector (con) or ubiquitinHA (C, right panel) was detected with anti-HA antibody. The γ2FLAG subunits that were pulled down with ubiquitinHA in the mutant condition (γ2FLAG/ubiquitinHA) were normalized to the wildtype condition. The γ2FLAG subunits were measured from about 75 KDa to 250 KDa (B) (***p < 0.01 vs Q390X; †p < 0.05 vs W461X). The total ubiquitinHA IDVs in C (left panel) were measured from about 25 KDa to 250 KDa. The ubiquitinHA IDVs were normalized to the ubiquitinHA IDVs when coexpressed with wildtype γ2FLAG subunits (D). (E) Rat cortical neurons coexpressing ubiquitinHA and γ2FLAG subunits were permeabilized and labeled with polyclonal anti-FLAG antibody and monoclonal anti-HA antibodies and visualized with FITC rabbit IgG and Cy5 mouse IgG. (F) The ratio of γ2FLAG over the ubiquitinHA fluorescence from the somata or processes in the same neurons were quantified and normalized to wt levels. (*p < 0.05, *** p<0.001 vs wt; †††p < 0.001 vs Q390X; §§§p < 0.001 vs W461X).

Mutant γ2 subunits protein triggered ER stress in a concentration-dependent manner

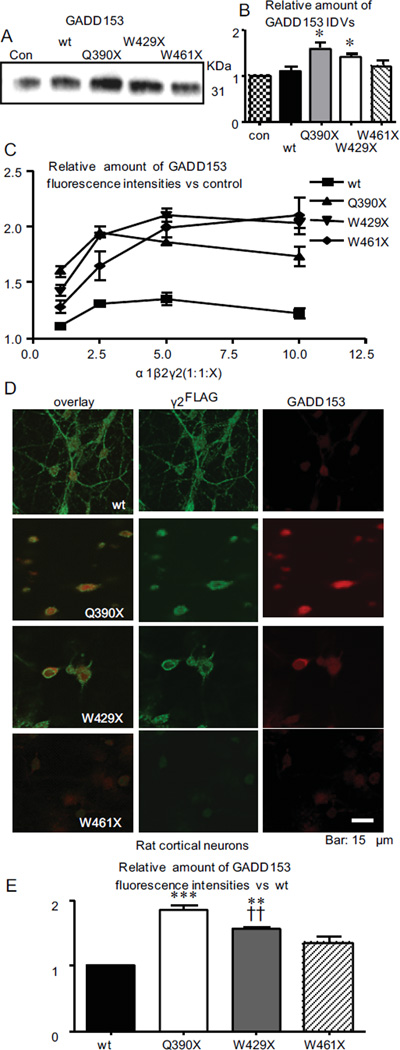

Accumulation of mutant protein in the ER could cause ER stress and trigger the unfolded protein response (UPR) 21. Thus we determined the expression of the ER stress hallmark growth arrest- and DNA damage-inducible gene 153 (GADD153), also known as C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP), in mouse or human L929 cells (Figure 9A, C) and in neurons (Figure 9D, E). We demonstrated that mutant γ2 subunits differentially upregulated GADD153 expression (wt 1.11 ± 0.10, n = 6; γ2(Q390X) (1.60 ±0.13, n = 7; γ2(W429X) (1.43 ± 0.06, n = 6; γ2(W461X) (1.22 ± 0.10, n = 5) (Figure 9B). With increasing expression of the mutant subunits, the GADD153 expression levels were progressively increased (Figure 9C). Consistent with the findings in mouse and human L929 cells, mutant γ2(Q390X) and γ2(W429X) subunits also upregulated expression of GADD153 in neurons (Figure 9D, E).

Figure 9. The truncated γ2 subunits upregulated expression of the ER stress hallmark GADD153 in a concentration-dependent manner.

(A) Total lysates from mouse L929 cells expressing wildtype or mutant γ2 subunits were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with mouse monoclonal anti-GADD153 antibody. (B) The total amounts of endogenous GADD153 were normalized to untreated controls (con) (*p < 0.05 vs wt n = 7). (C) Human L929 cells were transfected with α1β2 subunits with varying amounts of γ2 subunit cDNA, and total GADD153 fluorescence intensities (FI) were analyzed by flow cytometry using anti-GADD153 antibody (1:100) conjugated with Alexa 647 IgG (1:500). The total amounts of cDNA (12 µg) were normalized to empty vector. Relative GADD153 expression was normalized to untreated control expression. Reduction of GADD153 in cells expressing large amounts of γ2(Q390X) subunits (1:1:5–1:1:10) was due to loss of dead cells, which were excluded from the detected cell population. (D) Rat cortical neurons expressing γ2FLAG subunits were permeabilized and labeled with rabbit anti-FLAG antibody and mouse anti-GADD153 antibodies and visualized with FITC rabbit IgG and Cy5 mouse IgG. (E) Total GADD153 FI in γ2FLAG positive neurons was normalized to GADD153 FI in neurons expressing wildtype γ2FLAG subunits (**p < 0.01, ***p<0.001 vs wt, ††p < 0.01 vs Q390X).

Discussion

We propose that stability of trafficking-deficient mutant γ2 subunits may be a phenotype modifier in the associated genetic epilepsies. With nonsense mutations, the presence of different amounts of nonfunctional mutant protein among patients due to differential NMD efficiency has been associated with variation of disease phenotypes in both CNS and non CNS diseases 22,23. In both cases, patients with mutations that escaped NMD had more severe phenotypes. Our present study suggested that the degradation rate of the trafficking-deficient mutant subunits and the resultant ER resident truncated and trafficking-deficient subunits could be another disease phenotype modifier in addition to the efficiency of NMD, disease modifying genes 24 and genetic backgrounds. This may at least partially explain why the γ2(Q390X) subunit mutation is associated with a more severe epilepsy phenotype 11 than the γ2(W429X) subunit mutation 10 and why heterozygous GABRG2 deletion mice with no mutant truncated γ2 subunits displayed only hyperanxiety14 or simple absence seizures25.

We demonstrated that all nonsense GABRG2 mutations share a common defect, loss of the mutant allele function. In addition, the truncated γ2 subunits also had a dominant negative effect to reduce to different extents (γ2(Q390X) > γ2(W429X) > γ2(W461X)) the surface expression of α1 and β2 subunits and wildtype γ2 subunits 12,26. The different extents of dominant negative suppression by the truncated subunits were due to subunit-dependent steady-state protein levels and degradation rates (γ2(390X) t1/2 > γ2(W429X) t1/2 > γ2(W461X) t1/2). It is unclear why the truncated γ2 subunits had different protein stabilities. Increased hydrophobicity or exposure of hydrophobic residues is associated with protein aggregation and lower solubility 27, and the additional 39 residues present in the γ2(W429X) subunit (Figure 2A2) relative to the γ2(390X) subunit are relatively hydrophilic, which may explain, at least in part, the reduced amount of γ2(429X) subunit aggregation. It is worth noting that the reduced peak current, wildtype subunit expression and glycosylation maturation among mutations was only ∼20%. Given that only hyperanxiety 14 and absence seizure phenotypes were observed in heterozygous GABRG2 KO mice 25, that patients with the loss-of-function GABRG2(Q390X) mutation had DS and that there was only a 20–30% more reduction of current and wildtype subunit expression in the GABRG2(Q390X) “heterozygous” condition, this small difference at the molecular level may be enough to alter clinical phenotype severity. Similar observations have been made in other diseases such as Marfan’s syndrome 28. Some Marfan’s syndrome mutations produce 7–10% of the wildtype transcript level, which results in a severe phenotype due to suppression of wildtype protein function by the mutant protein. In contrast, other mutations activated more efficient NMD resulting in lower transcript levels and produced only subclinical phenotypes. However, the altered magnitude may vary regionally and temporally. Future work with KI mice will further elucidate the correlation of molecular and behavioral phenotypes among these mutations.

The different amounts of each of the different mutant γ2 subunits will result in their oligomerization with different amounts of wildtype subunits inside the ER. Mutant γ2(Q390X) subunits had the most, γ2(W429X) subunits had intermediate and γ2(W461X) subunits had the least oligomerization with α1 subunits. The less stable mutant γ2 subunits were degraded more rapidly and formed fewer stable oligomers with wildtype subunits, and thus were less effective in preventing wildtype subunits from forming functional receptors that trafficked to the cell surface.

Similarly, the polyubiquitin in cells expressing mutant γ2(Q390X) subunits was more overloaded than in cells expressing mutant γ2(W429X) or γ2(W461X) subunits. Ubiquitin is not only critical for protein disposal, it is also essential for many cellular events including DNA repair, cell differentiation and apoptosis, transcription as well as stress tolerance, synaptic plasticity and receptor endocytosis 29–32. Dysfunction of ubiquitin has been established to contribute to pathogenesis of many misfolded or aggregated protein related diseases including Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Huntington’s disease 33,34. In these diseases, chronic overloading of ubiquitin by misfolded or aggregated protein causes impaired synaptic function, plasticity and eventually synaptic loss and neuronal death 35.

Each mutant γ2 subunit also induced different levels of ER stress as evidenced by the upregulation of the ER stress marker GADD153. The more ER-retained γ2 subunits, the more ER stress. It is established that ER accumulation of mutant protein can disturb cellular homeostasis and trigger the UPR 36. The truncated γ2 subunits oligomerized with wildtype α1, β2 and γ2 subunits, thus trapping them in the ER. Consequently, both mutant and trapped wildtype subunits could trigger the UPR. Sustained ER stress would impose a negative impact on cells resulting in cellular dysfunction, injury and death. Misfolded proteins impose a concentration-dependent fitness cost in yeast and trigger the UPR independent of loss of protein function 37, suggesting similar costs in various types of cells that could contribute to many human diseases. In addition to triggering the UPR in the ER, misfolded proteins in the cytosol provoke a heat-shock response, oxidative stress, altered membrane integrity and reduced growth rate 38. It is likely that ER retention of mutant protein contributes to the pathogenesis of many inherited degenerative diseases 39 and conventionally nondegenerative diseases like genetic epilepsies.

In summary, we found that the amount of ER-trapped truncated γ2 subunits modulates wildtype channel function and cellular homeostasis. The loss of γ2 subunit function could alter seizure threshold and give rise to the core phenotype such as febrile seizures. The mutant subunit-dependent suppression of biogenesis and function of wildtype partnering subunits and disturbance of cellular homeostasis including differential conjugation of polyubiquitin, activation of ER stress and many undefined cellular signaling pathways could contribute to phenotypic variation.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by research grants from Citizen United for Research in Epilepsy (CURE), Dravet syndrome foundation (DSF), IDEAleague (Dravet organization) and Vanderbilt Clinical and Translation Science Award (CTSA) to KJQ and NIH grant # R01 NS51590 to RLM.

References

- 1.Kang JQ, Macdonald RL. Making sense of nonsense GABA(A) receptor mutations associated with genetic epilepsies. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace RH, Marini C, Petrou S, et al. Mutant GABA(A) receptor gamma2-subunit in childhood absence epilepsy and febrile seizures. Nat Genet. 2001;28:49–52. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cossette P, Liu L, Brisebois K, et al. Mutation of GABRA1 in an autosomal dominant form of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Nat Genet. 2002;31:184–189. doi: 10.1038/ng885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka M, Olsen RW, Medina MT, et al. Hyperglycosylation and reduced GABA currents of mutated GABRB3 polypeptide in remitting childhood absence epilepsy. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:1249–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delahanty RJ, Kang JQ, Brune CW, et al. Maternal transmission of a rare GABRB3 signal peptide variant is associated with autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tretter V, Ehya N, Fuchs K, et al. Stoichiometry and assembly of a recombinant GABAA receptor subtype. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2728–2737. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02728.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angelotti TP, Macdonald RL. Assembly of GABAA receptor subunits: alpha 1 beta 1 and alpha 1 beta 1 gamma 2S subunits produce unique ion channels with dissimilar single-channel properties. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1429–1440. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01429.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Essrich C, Lorez M, Benson JA, et al. Postsynaptic clustering of major GABAA receptor subtypes requires the gamma 2 subunit and gephyrin. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:563–571. doi: 10.1038/2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang C, Deng L, Keller CA, et al. GODZ-mediated palmitoylation of GABA(A) receptors is required for normal assembly and function of GABAergic inhibitory synapses. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12758–12768. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4214-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun H, Zhang Y, Liang J, et al. SCN1A, SCN1B, and GABRG2 gene mutation analysis in Chinese families with generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus. J Hum Genet. 2008;53:769–774. doi: 10.1007/s10038-008-0306-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harkin LA, Bowser DN, Dibbens LM, et al. Truncation of the GABA(A)-receptor gamma2 subunit in a family with generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:530–536. doi: 10.1086/338710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang JQ, Shen W, Macdonald RL. The GABRG2 mutation, Q351X, associated with generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus, has both loss of function and dominant-negative suppression. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2845–2856. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4772-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang JQ, Shen W, Lee M, et al. Slow degradation and aggregation in vitro of mutant GABAA receptor gamma2(Q351X) subunits associated with epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2010;30:13895–13905. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2320-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crestani F, Lorez M, Baer K, et al. Decreased GABAA-receptor clustering results in enhanced anxiety and a bias for threat cues. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:833–839. doi: 10.1038/12207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treier M, Staszewski LM, Bohmann D. Ubiquitin-dependent c-Jun degradation in vivo is mediated by the delta domain. Cell. 1994;78:787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Debiasi RL, Squier MK, Pike B, et al. Reovirus-induced apoptosis is preceded by increased cellular calpain activity and is blocked by calpain inhibitors. J Virol. 1999;73:695–701. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.695-701.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang JQ, Macdonald RL. The GABAA receptor gamma2 subunit R43Q mutation linked to childhood absence epilepsy and febrile seizures causes retention of alpha1beta2gamma2S receptors in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8672–8677. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2717-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunther U, Benson J, Benke D, et al. Benzodiazepine-insensitive mice generated by targeted disruption of the gamma 2 subunit gene of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7749–7753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallagher MJ, Ding L, Maheshwari A, et al. The GABAA receptor alpha1 subunit epilepsy mutation A322D inhibits transmembrane helix formation and causes proteasomal degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12999–13004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700163104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang JQ, Shen W, Macdonald RL. Two molecular pathways (NMD and ERAD) contribute to a genetic epilepsy associated with the GABA(A) receptor GABRA1 PTC mutation, 975delC, S326fs328X. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2833–2844. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4512-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Welihinda AA, Tirasophon W, Kaufman RJ. The cellular response to protein misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Gene Expr. 1999;7:293–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inoue K, Khajavi M, Ohyama T, et al. Molecular mechanism for distinct neurological phenotypes conveyed by allelic truncating mutations. Nat Genet. 2004;36:361–369. doi: 10.1038/ng1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hutchinson S, Furger A, Halliday D, et al. Allelic variation in normal human FBN1 expression in a family with Marfan syndrome: a potential modifier of phenotype? Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2269–2276. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawkins NA, Martin MS, Frankel WN, et al. Neuronal voltage-gated ion channels are genetic modifiers of generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;41:655–660. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reid CA, Kim T, Phillips AM, et al. Multiple molecular mechanisms for a single GABAA mutation in epilepsy. Neurology. 2013;80:1003–1008. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klausberger T, Fuchs K, Mayer B, et al. GABA(A) receptor assembly. Identification and structure of gamma(2) sequences forming the intersubunit contacts with alpha(1) and beta(3) subunits. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8921–8928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banerjee PR, Puttamadappa SS, Pande A, et al. Increased hydrophobicity and decreased backbone flexibility explain the lower solubility of a cataract-linked mutant of gammaD-crystallin. J Mol Biol. 2011;412:647–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montgomery RA, Geraghty MT, Bull E, et al. Multiple molecular mechanisms underlying subdiagnostic variants of Marfan syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1703–1711. doi: 10.1086/302144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hicke L. Protein regulation by monoubiquitin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:195–201. doi: 10.1038/35056583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salghetti SE, Caudy AA, Chenoweth JG, et al. Regulation of transcriptional activation domain function by ubiquitin. Science. 2001;293:1651–1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1062079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muratani M, Tansey WP. How the ubiquitin-proteasome system controls transcription. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:192–201. doi: 10.1038/nrm1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berke SJ, Paulson HL. Protein aggregation and the ubiquitin proteasome pathway: gaining the UPPer hand on neurodegeneration. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:253–261. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bennett EJ, Shaler TA, Woodman B, et al. Global changes to the ubiquitin system in Huntington's disease. Nature. 2007;448:704–708. doi: 10.1038/nature06022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilchrist CA, Gray DA, Stieber A, et al. Effect of ubiquitin expression on neuropathogenesis in a mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2005;31:20–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2004.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Speese SD, Trotta N, Rodesch CK, et al. The ubiquitin proteasome system acutely regulates presynaptic protein turnover and synaptic efficacy. Curr Biol. 2003;13:899–910. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gardner BM, Walter P. Unfolded Proteins Are Ire1-Activating Ligands that Directly Induce the Unfolded Protein Response. Science. 2011 doi: 10.1126/science.1209126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geiler-Samerotte KA, Dion MF, Budnik BA, et al. Misfolded proteins impose a dosage-dependent fitness cost and trigger a cytosolic unfolded protein response in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:680–685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017570108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu C, Brauer MJ, Botstein D. Slow growth induces heat-shock resistance in normal and respiratory-deficient yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:891–903. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-08-0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pennuto M, Tinelli E, Malaguti M, et al. Ablation of the UPR-mediator CHOP restores motor function and reduces demyelination in Charcot-Marie-Tooth 1B mice. Neuron. 2008;57:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]