Abstract

The level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) increases under different stresses and, by destroying cellular components, may cause cell death. In addition, ROS are part of the complex network of transduction signals that induce defense reactions against stress or, alternatively, trigger programmed cell death, and key questions are the levels of each ROS that, respectively determine defense and death responses of the cell. The answer to those questions is difficult because there are several patterns of cell death that frequently appear mixed and are hardly distinguishable. Moreover, although considerable progresses have been achieved in the determination of the levels of specific ROS, critical questions remain on the ROS level in specific cell compartments. By considering chloroplasts as the main source of ROS in photosynthetic tissues at light, a comparison of the levels in stress and senescence of the chloroplastic activities involved in the generation and scavenging of ROS suggests plausible differences in the levels of specific ROS between stress defense and death. In effect, the three activities of the chlororespiratory chain increase similarly in stress defense response. However, in senescence, superoxide dismutase (SOD), that converts superoxide anion radical () to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2,) decreases, while the thylakoid Ndh complex, that favors the generation of singlet oxygen (1O2) and , and peroxidase (PX), that consumes H2O2, increase. The obvious inference is that, in respect to defense response, the ratio (1O2 plus )/H2O2 is increased in the senescence previous to cell death. We hypothesize that the different ROS ratios, probably through changes in the jasmonic acid/H2O2 ratio, could determine the activation of the defense network or the death network response of the cell.

Keywords: chloroplast, chlororespiration, jasmonic acid, leaf senescence, programmed cell death, ROS, stress

INTRODUCTION

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) were formerly known for their damage effects on cellular components. Later, evidences, mainly accumulated along the last decade of twentieth century, showed at the turn of the millennium (Potikha et al., 1999; Quirino et al., 2000; Van Breusegem et al., 2001; Apel and Hirt, 2004; Zimmermann and Zentgraf, 2005; Gechev et al., 2006; Zentgraf, 2007; Khanna-Chopra et al., 2013) additional roles of ROS as transduction signals within the complex network of molecules controlling developmental processes (mainly those leading to cell death) and responses to environmental stresses. In addition to the formidable problem to understand the functional integration of the complex networks regulating the different developmental processes with moderately stable node molecules as proteins and hormones, ROS signals posed entirely new challenges due to uncertainties on their generation and scavenging, on their mobility among cell compartments and on the molecular mechanisms of their interactions with other components (nodes) of the transduction network.

The involvement of ROS in the senescence of photosynthetic tissues provides a good system to size the magnitude of the challenges and to follow progresses to understand the integration of ROS signals within the networks controlling cell cycle and responses to stress. To distinguish between the ROS mediated effects in stress and in cell death, we address two fundamental aspects related to the roles of ROS in the programmed senescence of photosynthetic tissues under field conditions at light: (1) sources and sinks of ROS, and (2) signals that immediately follow ROS in the transduction networks. Programed senescence and death of photosynthetic leaves probably represents the highest amount of biomass and number of cells in the Earth suffering programmed cell death (PCD). Senescence of photosynthetic fruit tissues is a case of programmed senescence, not immediately followed of death, which is part of the maturation of most fleshy fruits and, as such, of high economic relevance. Similitude and differences between the senescence of leaf and the ripening of fruits were recognized since long time and we will refer the last exclusively for recent advances related to the involvement of components of the ROS generation machinery in fruit maturation. In a lesser extension, we will refer to a few processes where ROS signals are also involved and provide insights to understand leaf senescence under field conditions. Among them, the senescence and death of animal cell provides a lot of research advances that may be relevant. Senescence of non-photosynthetic plant cell, cell death associated to hypersensible response (HR), leaf senescence associated to diverse abiotic stresses (dark, drought, low, and high temperatures, nutrient deficiency,) and stress responses in general are fields where recent investigations provide insight relevant to the involvement of ROS as node signals in networks controlling cell processes.

There are different types of cell senescence and death, which frequently make difficult the comparison of the research results in different organisms, in different tissues of an organism and of different types of senescence and death of a specific tissue. For a comparison with the best characterized types of cell senescence and death in animals (Bialik et al., 2010), and in relation to the involvement of ROS, programmed leaf senescence and death shows similarities with the apoptotic/necrotic “intrinsic death pathways,” as far as the mitochondrial ROS source in animal is substituted by the chloroplast ROS source (Zapata et al., 2005; Doyle et al., 2010; Sabater and Martín, 2013).

ROS IN PHOTOSYNTHESIZING LEAVES

Sources and transformation of the main ROS has been intensely investigated in leaves and details may be consulted elsewhere (Karpinski et al., 2001; Sabater and Martín, 2013). Figure 1 summarized the best-known ROS, their transformation and deleterious effects on cell components. In addition to the main ROS found in non-photosynthetic cells: superoxide anion radical (), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical (HO∙); another ROS, the singlet oxygen (1O2), is produced in chloroplast by transfer of excitation from triplet excited chlorophyll (3Chl*) to O2. Hydroperoxyl radical () is also formed although probably in a lesser amount (Grace, 2005). The main four ROS are currently (and majorly) formed by chloroplasts at light and, to minimize their deleterious effects, scavenged by non-enzymatic and enzymatic reactions as superoxide dismutase (SOD), converting to H2O2, and peroxidase (PX) consuming H2O2., and then H2O2 and HO∙ , are also generated in other cell compartments, especially in mitochondria and peroxisomes where H2O2 is destroyed by catalase. To prevent the generation of excess 1O2, heat dissipation of 3Chl* excitation is enhanced through zeaxanthin formed by the xanthophyll cycle (Eskling et al., 2001). At high light intensity, the NADPH generated in the photosynthetic electron transport (PET) exceeds the capacity of the Benson–Calvin cycle to consume it (for example at low temperature or low CO2 supply by partially closed stomata). Then, transporters of the PET become over-reduced, the production of ROS increases and, depending on the environmental severity and the rapidity of the correction responses, it can destroy cell components producing the syndrome of photo-oxidative stress and eventually causing cell death (Levine, 1999).

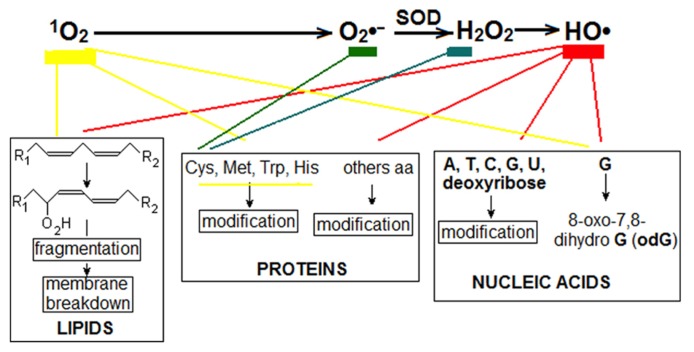

FIGURE 1.

Main ROS found in leaves. Triplet excited chlorophyll (3Chl*) can transfer excitation to oxygen to produce singlet oxygen (1O2). Successive steps convert 1O2 to , H2O2 and HO∙ . In addition, and probably mainly, is produced in the chloroplast by the transfer of one electron from reduced iron-sulfur proteins to O2 (Mehler reaction). Two and two H+, in reaction catalyzed by superoxide dismutase (SOD), produce one molecule of H2O2 and another of H2O. Decomposition of H2O2 to HO∙ is catalyzed by different divalent cations, especially Fe2+ (Fenton reaction). Alternatively, H2O2 may be consumed by catalase and peroxidase catalyzed reactions. Several cell components are destroyed by ROS. 1O2, directly, and HO∙ with oxygen transform 1,4-unsatured fatty acids to hydroperoxy-derivatives (-O2H) which further undergo different transformations, including fragmentations that disassemble membranes. Again, mainly 1O2 and HO∙ modify bases in DNA, RNA, and free bases, especially guanine (G) which is transformed to 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro guanine (odG), which can be paired with C or A, producing erroneous proteins and mRNA and DNA mutations. Most of the amino acids, free or in polypeptide chains, can be modified by ROS; cysteine is especially sensitive to and H2O2; cysteine, methionine, tryptophan, and histidine are especially sensitive to 1O2.

It must be emphasized that over-reduction of components of PET causes increases of ROS whose destructive action is associated to their strong oxidant power and frequently is difficult to distinguish effects regulated by ROS from those regulated by the redox state of the chloroplast (Kruk and Szymánska, 2012). The paradox is not the unique problem to take into account when ROS are investigated as signal within the regulatory network of the cell. As pointed above, high level of ROS, per se, can produce cell death under stress conditions without involving specific signal transduction. To make more complex the situation, many evidences indicate that ROS signals are involved in the response to alleviate photo-oxidative stress that is mainly based on the repression of some genes and induction of some another, mainly those encoding the enzyme systems, as chloroplastic SODs, that scavenge ROS. Under this perspective, the key question is the level of each ROS required for such opposite cell responses as PCD and alleviation of stress to avoid death (Sabater and Martín, 2013). There is not yet a satisfactory response to that question, but there are some aspects, as the nature of the ROS acting as signal and the organelle location of sources and sinks of the different ROS, that provide valuable information on the signaling by ROS in leaf senescence.

ARE ALL ROS TRANSDUCTION SIGNALS?

Damage effects of ROS (Figure 1) are mainly unspecific and could hardly be envisaged as related to their mechanism of interaction with other signal molecules of the regulatory network of the cell. However, effects other than damage are conceivable for H2O2. On the other hand, being 1O2, and HO∙ short-lived, the more stable (and permeable through membranes) H2O2 seems the plausible ROS signal candidate that interacts with other components of the regulatory cellular network and generates genetic and other responses of the cell to stress and PCD. Moreover, as H2O2 is substrate of catalase and diverse PXs, it could conceivably interact (enzymatic or not enzymatically) with proteins downstream in a signal cascade of a cellular network. H2O2 is also the product of the sequence of transformations of 1O2 and (Figure 1), which, in a first approximation, suggests that the increase of these ROS was finally senses by an increase of H2O2 and that, in the simplest imaginable mechanism, H2O2 would be the unique ROS signal of the cellular networks. From a broad perspective, the transformations 1O2 to and then to H2O2 should be no other than stages of signal transduction until the last ROS before non-ROS nodes. As we will see, facts are not so simple. Certainly, there many evidences that H2O2 is a signal, at least in the transduction cascades of the responses to stress, but there are strong evidences suggesting that and, specially, 1O2 could also be signals that, independently of their transformation to H2O2, originate cascade signals involved in leaf senescence.

ROS GENERATION AND SCAVENGING IN STRESS AND SENESCENCE

In effect, the dynamic of ROS generation and scavenging in the healthy and mild-stressed leaves seems to change in senescence. As pointed above, in health photosynthesizing leaf, 1O2 and are formed in chloroplasts by excitation and electron transfer, respectively, to oxygen, processes that are enhanced when there is excess of light in respect to the capacity to consume NADPH (mainly in the Benson–Calvin cycle). Enzymatic and non-enzymatic mechanisms maintain low steady-state levels of ROS by lowering the formation of 1O2 through heath dissipation of excited chlorophyll and, in the reaction catalyzed by SOD, transforming to H2O2, which is consumed by PXs and transformed by the Fenton reaction (Fe2+ + H2O2→Fe3+ + HO∙ + OH-) to (Jakob and Heber, 1996). HO∙ is rapidly consumed in diverse reactions. In an unknown extension, 1O2 seems to be able to oxidize reduced plastoquinone contributing to draining electrons from over-reduced PET (Kruk and Szymánska, 2012). Among chloroplast PXs, plastoquinol PX (Zapata et al., 1998), in addition to scavenge H2O2, directly drains electrons from PET, contributing to alleviate the excess of reducing power that enhances the production of ROS but, at the same time, decreasing the efficiency of the use of light energy in photosynthesis. Similarly, the Mehler reaction generates by draining electron from PET (mainly from reduced non-heme iron-sulfur protein, FeSPred) and, thus, it decreases the efficiency of photosynthesis. At the photo-physical stage, the heath dissipation of excited chlorophyll to reduce the formation of 1O2 also impairs the use of light energy in photosynthesis. Therefore, plants have evolved mechanisms to regulate the processes of generation and scavenging of ROS by adjusting them to different environmental conditions in order to minimize ROS damage and maximize photosynthesis yield. The adjusting is got through appropriate level of zeaxanthin, SOD, and PX (Bowler et al., 1992; Casano et al., 1999; Eskling et al., 2001; Karpinski et al., 2001) for any combination of light intensity, temperature, and CO2 availability (which depends on several factors as stomatal opening).

However, the light intensity that receives the leaf strongly and rapidly fluctuates under natural conditions (Pearcy, 1994; Külheim et al., 2002), which make necessary continuous adjustments of enzyme activities and inevitable transitory burst of ROS and losses of photosynthesis efficiency. The adjustment is not easily reached because many processes are functionally interconnected in photosynthesis. Hence, like photophosphorylation, the dissipation of heat by zeaxanthin requires an appropriate gradient of proton (ΔpH) across the thylakoid membrane (Eskling et al., 2001). However, as pointed out by Heber and Walker (1992), when the components of PET are over-reduced the rate of cyclic PET is too low to supply the necessary extra transport of protons to thylakoid lumen; the functioning of cyclic PET requires balanced (poised) levels of both reduced and oxidized forms of the electron transporters. From this perspective, the draining of electrons from PET by Mehler reaction and plastoquinol PX allows to poise the redox level of the cyclic electron transporters (Casano et al., 2000) and, then, to maintain the appropriate ΔpH for the dissipation as heath of the excess of absorbed light. Thus, the generation of and H2O2 would be a less harmful alternative than the formation of 1O2 under transitory high light. The photo-inhibition of photosystem II (PSII; Osmond, 1994) is other important response of the photosynthetic machinery to transitory high light. When light comes back to moderate or low intensity, the recovery to full activity of photo-inhibited PSII could last several seconds and, frequently, minutes; too much time when compared with the rapid light intensity changes (fraction of second) that a section of a trembling leaf confronts frequently in windy fields. Quickly, after transition to low light, the ΔpH would collapse, now because the electron transporters of the cyclic PET become over-oxidized by the transitory low supply of electrons from PSII. The collapse is prevented because the redox poising of transporters is maintained through the feeding of electrons from NADH by the thylakoid Ndh complex (EC 1.6.5.3; Casano et al., 2000; Sabater and Martín, 2013) a product of the 11 plastid and a few nuclear ndh genes.

Therefore, operating alternatively, the supply of electrons (by the Ndh complex) and the drain of electrons (by concerted actions of the Mehler reaction, SOD and plastoquinol PX) ensure the fine-tuning of the redox level of the transporters of electrons in the cyclic PET. The complete sequence of reactions is:

and results in a global respiratory process named chlororespiration (Casano et al., 2000; Joët et al., 2002; Nixon and Rich, 2007):

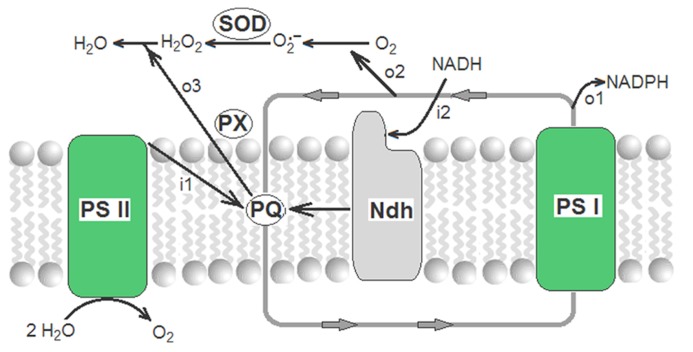

that is schematized in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Redox poising of electron transporters of the cyclic PET by chlororespiratory reactions. Closed gray line with arrows corresponds to cyclic PET where only plastoquinone (PQ) and photosystem I (PSI) are shown. i1 and i2 are the influxes of electrons from, respectively, photosystem II (PSII) and from NADH (through the thylakoid Ndh complex). o1, o2, and o3 are the outfluxes of electrons to, respectively, NADP+, Mehler reaction, and plastoquinol peroxidase.

In the field, rapid increases and fluctuations of the intensity of light, high and low temperatures, hydric stress, and aggressive chemicals rapidly change the rates of electron supply (from PSII) and consumption (by the Benson–Calvin cycle). In this scenario, to maintain functional the cyclic PET and minimize damages by ROS, the activities of the chlororespiratory chain (Ndh complex, SOD, and PX) must be high in comparison with more stable or mild environments. Accordingly, the levels of the Ndh complex increase under different stresses (Serrot et al., 2008; Paredes and Quiles, 2013) and Ndh deficient tobaccos are especially sensible to damages under stress (Martín et al., 1996, 2004; Endo et al., 1999; Prochazkova et al., 2001; Rumeau et al., 2007). There is also a large and classic literature reporting the increase of SOD and/or PX under different stress conditions (see a revision in Bowler et al., 1992). In addition to other factors, the relative activities of the thylakoid Ndh complex, SOD, and PX must determine the relative levels the different ROS in the steady state. Therefore, when the activities were measured in parallel assays, levels of the thylakoid Ndh complex and of the chloroplast SODs (FeSOD and Cu/ZnSOD) and plastoquinol PX increase similarly in young photosynthesizing leaves of tobacco or barley plants subjected to diverse stressing agents (Casano et al., 1994, 1999; Martín et al., 1996, 2004). Always, increases of the Ndh, SOD, and PX are precisely mediated by ROS (Casano et al., 2001) at gene expression and, probably, enzyme activation (Lascano et al., 2003).

When adult-senescent leaves are subjected to different stresses, Ndh complex level and activity as well as those of plastid PX increase in a similar way than in young fully photosynthesis active leaves. In contrast, the induction of SOD in response to stress becomes progressively impaired when leaves enter senescence (Casano et al., 1994, 1999; Kurepa et al., 1997; Abarca et al., 2001a,b; Prochazkova et al., 2001; Ohe et al., 2005). The results provide clues for the frequently reported interactions between stress response and senescence (Behera et al., 2003) and suggest that the fail to induce chloroplastic SOD plays a key role in leaf senescence. This should strongly remember the animal systems where, transgenic over-expressing SOD and catalase show a significant life-span extension (Orr and Sohal, 1994). In the last, catalase must also be over-expressed to avoid the increase of H2O2 formed by over-expressed SOD. Chloroplast lacks catalase but contains several PXs (among them plastoquinol PX) whose increase in senescence must efficiently consume the low amount of H2O2 produced by chloroplast lacking SOD in senescing leaves. In this line, in adult-senescent leaves, over-expression of the Ndh complex and chloroplastic PX and under-expression of chloroplastic SOD must increase the level of and decrease the level of H2O2 in respect to the response of young leaves. As the Ndh complex provides electrons, per se, it must increase the redox level of the transporters and, consequently, the formation of 1O2 and . In contrast to young leaves where increased formations of 1O2 and are neutralized, respectively, by increased heat dissipation and increased scavenging by higher SOD, in adult senescent leaves, 1O2 and produced after a mild stress increased continuously out of control because Ndh complex and PX are induced by ROS.

To the large number of classic publications reporting the decrease of chloroplastic SOD and the increase of PX during leaf senescence, many latter references report the increase of the Ndh complex during leaf senescence and fruit ripening (Martín et al., 1996; Casano et al., 1999, 2000; Lascano et al., 2003; Nashilevitz et al., 2010; Nilo et al., 2012; Serrot et al., 2012). In addition, the involvement of the Ndh complex in senescence seems clear from the delay of leaf senescence (some 30 days in respect to wild type) in transgenic tobacco defective in the ndhF gene and Ndh complex (Zapata et al., 2005). Significantly also, long-lived conifers, as Pinus longaeva whose needles remain functional for 35 years, lack ndh genes in their sequenced plastid DNA (Wu et al., 2011).

HYPOTHESIS: A HIGH RATIO (1O2 + )/H2O2 CHANGES STRESS DEFENSE RESPONSE TO PROGRAMMED LEAF SENESCENCE

Summarizing the evidences discussed above, the decrease of SOD and the increase of the Ndh complex play crucial roles in senescence by determining an increase of , yet reported by McRae and Thompson (1983), and a decrease of H2O2 in chloroplasts which contrasts with the increase of these two ROS in stress responses. It seems that, within the network of transduction signals that regulate the response to stress, the nodes involved in the control of the levels of the Ndh complex remain intact in adult-senescent leaves but those controlling the levels of chloroplastic SOD (FeSOD and Cu/ZnSOD) fail to respond. Then, fine-tuning of the redox level of the electron transporters of cyclic PET is broken early in leaf senescence and gives way to their over-reduction and to a growing spiral of ROS production and death.

Externally supplied H2O2 increases the expression of the plastid ndh genes, the levels of the Ndh complex and the NADH dehydrogenase activity of the Ndh complex by phosphorylation of the NDH-F subunit (Casano et al., 2001; Lascano et al., 2003; Martín et al., 2009). In general, H2O2 is involved in the defense response against different biotic and abiotic stresses (Casano et al., 1999, 2001; Levine, 1999). Although H2O2 probably mediates the increase of the Ndh complex in the defense of young leaves against stress, the increase of the Ndh complex during senescence does not seem due to the increase of H2O2 production in chloroplasts. Bieker et al. (2012) reported that H2O2 level transitorily doubled in brassicaceae leaf during bolting and flowering time, probably related to decreases of catalase and ascorbate PX and not to a high production of H2O2 in chloroplasts. In fact, although H2O2 could increase in peroxisomes (Del Rio et al., 1998), there is no evidence of the increase of H2O2 production in chloroplasts during natural leaf senescence under field light and, accordingly, no accumulation of H2O2 was found during the PCD of bundle sheaths in the maize camouflage1 (cf1) mutant (Huang and Braun, 2010). As pointed above, chloroplasts are probably the main cellular source of H2O2 in the leaf at light, and that source is considerably reduced in adult-senescent leaves. Reduced enough to abolish the main H2O2-dependent transduction signaling in the protection responses against stress. The hypothesis of a low level of H2O2 (in respect to 1O2 and ) during senescence is essentially based on the low levels of the activity that forms it (SOD) and the high level of the activity that consume it (PX). Rapid turnover and damage effects make difficult a precise definition of the level of 1O2 or , of the (1O2 + )/H2O2 ratio, and of a threshold ratio that changes defense response to PCD. At present, the concept of (1O2 + )/H2O2 ratio urges researches on signaling downstream of 1O2 and and on methods for accurate measurements of ROS in plants. The determination of the levels of each 1O2, , and H2O2 in cytosol and in each organelle is difficult but would be particularly relevant with data on the cellular location of the network nodes directly influenced by them.

In contrast to the other ROS produced in chloroplast (1O2, , and HO∙), H2O2 is sufficiently stable and presumably permeable through chloroplast membranes to connect with the cytosolic network of signals that control specific gene expression in the nucleus. Immediate targets of H2O2 are not yet known and plausible candidates in cytosol, or also into the chloroplast, are 2-cysteine peroxiredoxins (PRDX). These could also act as redox signals (Dietz, 2003; Muthuramalingam et al., 2009; Puerto-Galán et al., 2013) and as regulators of the level of H2O2. Many evidences connect the H2O2 signaling with cascades of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases that are involved in the H2O2 production and in the regulation of death, mainly in the response to biotic and abiotic stresses (Overmyer et al., 2003). Moreover, the H2O2-mediated increase of the ndh gene expression seems to depend on protein kinases (Casano et al., 2001; Lascano et al., 2003). However, no protein has yet identified that directly interacts with H2O2 in network signaling.

SIGNALING DOWNSTREAM OF 1O2 AND

If 1O2 and (or) , in the place of H2O2 and its derivative HO∙, are the chloroplast ROS signals involved in programmed leaf senescence, the obvious question refers to its (their) immediate target. As mentioned above, 1O2 or can barely be exit from the chloroplast. Therefore, the immediate target must be into the chloroplast. The modification of amino acids is the main known damage produced by (Figure 1) and, essentially, the same amino acids are modified by and H2O2. Therefore, the oxidation of cysteine residues of proteins by could initiate in chloroplast a signal similar to those supposed for H2O2 in chloroplast and cytosol. However, no precise or specific protein target is yet known that initiates a signal after oxidation by . Other possibility is that the general damage effects of in chloroplasts and the lack of H2O2 for draining the excess of electrons, should impair the rate of cyclic PET collapsing the thylakoid membrane potential and, thus, shooting the production of more 1O2 that would become the key initial signal that compels the cell to death at light. As pointed above, to maintain the leaf functional and healthy, the chloroplast forms other ROS than 1O2. Therefore, the low level of 1O2 must be an objective for enduring cell. For senescence and death, 1O2 probably initiates a signal chain linked to the damage of polyunsaturated fatty acids.

As Figure 1 shows, 1O2 attacks polyunsaturated fatty acids. The first products of the attack of polyunsaturated fatty acids of membrane lipids by 1O2 are 13-hydroperoxy derivate fatty acids. Among them, 13-hydroperoxy linoleic acid is transformed in chloroplasts to the oxylipin (9S, 13S)-12-oxo-phytodienoic acid, which is transformed into jasmonic acid (JA) in peroxisomes and further, in cytosol, to related compounds as methyl jasmonate (Creelman and Mulpuri, 2002; Wasternack, 2007). In this way, JA and several related compounds mediate the rapid response to the stress generated by the production of 1O2 (Wagner et al., 2004) inhibiting the synthesis of protein for the photosynthetic machinery (Reinbothe et al., 1993) and stimulating the expression of genes for the defense against stress and of the senescence associated genes (SAG; Creelman and Mulpuri, 2002). Among other effects, JA and related oxylipin derivatives stimulate the expression of chloroplast lipoxygenase (LOX; Bachmann et al., 2002) and increase the level of the thylakoid Ndh complex (Cuello et al., 1995). Precisely, LOX catalyzes the reaction of free linoleic acid with O2 to form further 13-hydroperoxy linoleic, which, as described, generates more JA and derivatives (Schaller et al., 2004), now dependent on O2, but not of the 1O2 formed by light excess. Therefore, under appropriate conditions, which are plausibly related to the levels of other signals, JA seems a key signal able to generate an autocatalytic cell path to death (Figure 3). In this regard, it is significant that treatments with JA increase the production of 1O2 (Guo et al., 2010) and accelerates senescence (Wasternack, 2007). If not the start gunfire of senescence, the coincidence of high PX, Ndh complex, LOX, and 1O2 with low SOD seems to open the irreversible path to cell death. The spiral increase of ROS (and more precisely of 1O2 or ) is under genetic control, firstly determining the expression of PX and Ndh complex, and later of LOX. The last initiates a light independent increase of JA and, as a consequence, of further light-dependent increase of 1O2. Key nodes of the death path would be JA, which increase and thus induces SAG, and H2O2, which decreases and thus prevent the induction of stress defense genes. Independently of the damage effect of ROS, through the further induction of SAG by JA, the overall process appears a PCD.

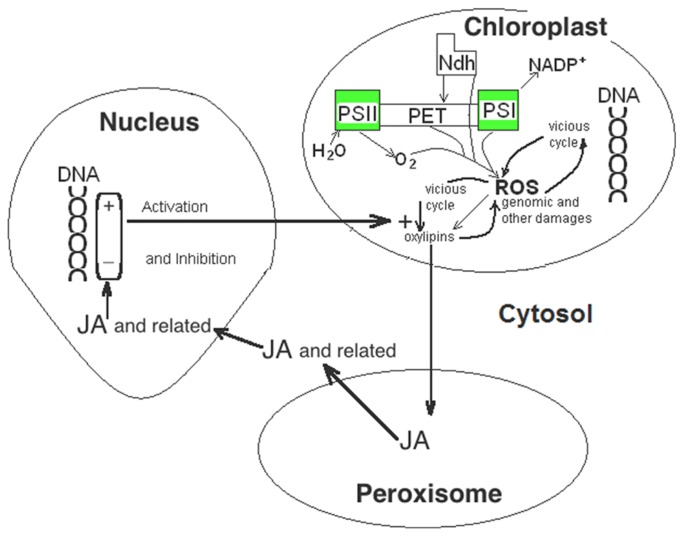

FIGURE 3.

Oxylipins facilitate the vicious cycle that increases the levels of 1O2 and (ROS). JA and related compounds are formed in peroxisomes and cytosol from oxylipins generated in chloroplasts by the action of 1O2 on linoleic acid. Within nucleus, JA and related compounds inhibit genes for chloroplastic SOD and induce genes for chloroplastic LOX and for the Ndh complex subunits encoded in the nucleus that further increase the levels of 1O2 and ROS and, then, of JA.

It would be concluded that the initiation of the program for leaf death is the fail to properly stimulate the expression chloroplastic SODs under mild stress, but the meaning of starting point is fading in an autocatalytic spiral of events as that proposed. Hence, among SAGs, MYB transcription factors have been described (Chen et al., 2002; Buchanan-Wollaston et al., 2005) that bind to the AACTAA motif inhibiting the progression of the transcription machinery to downstream genes. Precisely, the AACTAA motif is close to AGATAA and TATA motifs for the initiation of transcription in upstream region of the Csd2 gene (encoding the chloroplast Cu/ZnSOD) in Arabidopsis. In this way, the induction of the SAG for MYB must obstruct the expression of the chloroplastic SOD, hence contributing, in addition to the mechanisms described above, to the growing spiral of the 1O2 and ROS in leaf senescence (Sabater and Martín, 2013).

The regulatory upstream region of the Arabidopsis Csd2 gene also includes two W-boxes (TGAC(T)) recognized by WRKY transcription factors (Eulgem et al., 2000), some of them induced during leaf senescence (Singh et al., 2002). The gene encoding one of them, WRKY53, also has a high relevance as the crossing point where different signals, and more specifically JA and H2O2 (Zentgraf et al., 2010) should determine defense response or PCD. In effect, although other signals as salicylic acid and nitric oxide (Wang et al., 2013) may be involved, the model described above indicates that the high 1O2 plus /H2O2 ratio in senescence, in respect to non-lethal stress response, is transduced into a high comparative JA/H2O2 ratio. JA and H2O2 would influence (by activation or inhibition, depending on concentration and other factors) at the different steps of complex transduction networks that control stress response and PCD by WRKY53. To add more complexity, several proteins control the expression of the WRKY53 gene and the binding of the WRKY53 protein to DNA upstream of genes expressed in senescence. Therefore, through variable responses to JA and H2O2, the complex network of WRKY proteins could be crucial determining the transition of the defense response to PCD as a consequence of increased 1O2 plus /H2O2 ratio.

The model described for leaf senescence requires, at least in its first stages, light acting on the photosynthesis machinery. But the syndrome of leaf senescence would be more complex in field where alternating light and dark periods during the day could overlap light dependent senescence with dark dependent senescence. Under this condition, the involvement of a high production of H2O2 in cytosol or non-chloroplast organelles could be relevant. In addition, hormonal factors related to developmental processes, as seed filling and shadowing by upper leaves, and nutritional factors can produce a mixture senescence mechanisms, one of which could be dominant in some plants and environments.

CONCLUDING REMARKS AND FUTURE PROSPECTS

In contrast to animals, the development of plants is strongly affected by environmental factors and, not surprisingly, ROS are involved as signals in developmental processes leading to cell death and in the defense response against environmental stress. Difficulties to determine the levels of some specific ROS in the different cell compartments open key questions as the levels and mechanisms through which ROS control different issues such as death and defense. In addition, and similarly to other signals of the networks controlling developmental processes, the level of ROS are subjected to multiple cross, feed-forward, and feed-back effects and poorly known factors, as iRNA and epigenetic modifications, that make difficult to identify a precise cause to effect chain of events explaining the final response of the plant.

However, in contrast to most other signals, the successive steps for enzymatic, and non-enzymatic generation and scavenging of the main ROS (1O2, , H2O2, and HO∙ ) are well known. In addition, the levels of the enzymes involved in the generation and scavenging of most ROS can be accurately determined in different cell compartments and in different stress and senescence conditions. From enzyme data, qualitative level differences between stress and senescence for each ROS can reasonably be proposed for different cell compartments which progresses in ROS determination (Woolley et al., 2013) could test in the future. With this approach, the hypothesis presented here of a high ratio (1O2 + )/H2O2 for the initiation of senescence at light, could be extended or modified after comparison of enzymatic activities in stress responses with those in other types of senescence, including the senescence of non-photosynthetic tissues. The results must facilitate the identification of proteins that directly interact with specific ROS in the regulatory cellular networks. In a first approach, the complex of WRKY proteins deserves full attention. In addition, the results would provide a wide perspective to investigate more precisely the control of genes for generation and scavenging of ROS in stress and PCD.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant BFU2010-15916 of the Spanish Dirección General de Investigación (Ministerio de Economía y Desarrollo).

REFERENCES

- Abarca D., Martín M., Sabater B. (2001a). Differential leaf stress responses in young and senescent plants. Physiol. Plant. 113 409–415 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2001.1130314.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abarca D., Roldán M., Martín M., Sabater B. (2001b). Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Cvi shows an increased tolerance to photo-oxidative stress and contains a new chloroplastic copper/zinc superoxide dismutase isoenzyme. J. Exp. Bot. 52 1417–1425 10.1093/jexbot/52.360.1417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apel K., Hirt H. (2004). Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55 373–379 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann A., Hause B., Maucher H., Garbe E., Vörös K., Weicher H., et al. (2002). Jasmonate-induced lipid peroxidation in barley leaves initiated by distinct 13-LOX forms of chloroplasts. Biol. Chem. 383 1645–1657 10.1515/BC.2002.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behera S. K., Nayak L., Biswal B. (2003). Senescing leaves possess potential for stress adaptation: developing leaves acclimated to high light resist osmotic stress during senescence. J. Plant Physiol. 160 125–131 10.1078/0176-1617-00791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialik S., Zalckar E., Assaf Y. B., Rubinstein A. D., Kimchi A. (2010). System biology analysis of programmed cell death. Trends Biochem. Sci. 36 556–564 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieker S., Riester L., Stahl M., Franzaring J., Zentgraf U. (2012). Senescence-specific alteration of hydrogen peroxide levels in Arabidopsis thaliana and oilseed rape spring variety Brassica napus L. cv. MozartF. J. Integ. Plant Biol. 54 540–554 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2012.01147.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler C., Van Montagu M, Inzé D. (1992). Superoxide dismutase and stress tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 43 83–116 10.1146/annurev.pp.43.060192.000503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan-Wollaston V., Page T., Harrison E., Breeze E., Pyung O. L., Nam H. G., et al. (2005). Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals significant differences in gene expression and signalling pathways between developmental and dark/starvation-induced senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 42 567–585 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02399.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casano L. M., Martín M., Sabater B. (1994). Sensitivity of superoxide dismutase transcript levels and activities to oxidative stress is lower in mature-senescent than in young barley leaves. Plant Physiol. 106 1033–1039 10.1104/pp.106.3.1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casano L. M., Martín M., Sabater B. (2001). Hydrogen peroxide mediates the induction of chloroplastic Ndh complex under photooxidative stress in barley. Plant Physiol. 125 1450–1458 10.1104/pp.125.3.1450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casano L. M., Martín M., Zapata J. M., Sabater B. (1999). Leaf age- and paraquat-dependent effects on the levels of enzymes protecting against photooxidative stress. Plant Sci. 149 13–22 10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00138-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casano L. M., Zapata J. M., Martín M., Sabater B. (2000). Chlororespiration and poising of cyclic electron transport: plastoquinone as electron transporter between thylakoid NADH dehydrogenase and peroxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 275 942–948 10.1074/jbc.275.2.942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Provart N. J., Glazebrook J., Katagiri F., Chang H. S., Eulgem T., et al. (2002). Expression profile matrix of Arabidopsis transcription factor genes suggests their putative functions in response to environmental stresses. Plant Cell 14 559–574 10.1105/tpc.010410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creelman R. A., Mulpuri R. (2002). The oxylipin pathway in Arabidopsis. Arabidopsis Book 1 e0012 10.1199/tab.0012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello J., Quiles M. J., Rosauro J., Sabater B. (1995). Effects of growth regulators and light on chloroplast NAD(P)H dehydrogenase activities of senescent barley leaves. Plant Growth Regul. 17 225–232 10.1007/BF00024730 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rio L. A., Pastori G. M., Palma J. M., Sandalio L. M., Sevilla F., Corpas F. J., et al. (1998). The activated oxygen role of peroxisomes in senescence. Plant Physiol. 116 1195–1200 10.1104/pp.116.4.1195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz K. J. (2003). Plant peroxiredoxins. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 54 93–107 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle S. M., Diamond M., McCabe P. F. (2010). Chloroplast and reactive oxygen species involvement in apoptotic-like programmed cell death in Arabidopsis suspension cultures. J. Exp. Bot. 61 473–482 10.1093/jxb/erp320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T., Shikanai T., Takabayashi A., Asada K., Sato F. (1999). The role of chloroplastic NAD(P)H dehydrogenase in photoprotection. FEBS Lett. 457 5–8 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00989-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskling M., Emanuelsson A., Akerlund H. E. (2001). “Enzyme and mechanisms for violaxanthin-zeaxanthin conversions,” in Regulation of Photosynthesis eds Aro E. M., Andersson B. (Dordrecht: Kluwer; ) 433–452 [Google Scholar]

- Eulgem T., Rushton P. J., Robatzek S., Somssich I. E. (2000). The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 5 199–206 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01600-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gechev T. S., Van Breusegem F., Stone J. M., Denev I., Laloi C. (2006). Reactive oxygen species as signals that modulate plant stress responses and programmed cell death. BioEssays 28 1091–1101 10.1002/bies.20493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace S. C. (2005). “Phenolics as antioxidants,” in Antioxidant and Reactive Oxygen Species in Plants ed. Smirnoff N. (Oxford: Blackwell; ) 141–168 [Google Scholar]

- Guo X. X., Yan X. Q., Yang R. Y., Zeng Q. P. (2010). Salicylic acid and methyl jasmonate but not Rose Bengal enhance artemisinin production through invoking burst of endogen singlet oxygen. Plant Sci. 178 390–397 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.01.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heber U., Walker D. (1992). Concerning a dual function of coupled cyclic electron transport in leaves. Plant Physiol. 100 1621–1626 10.1104/pp.100.4.1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M., Braun D. M. (2010). Genetic analyses of cell death in maize (Zea mays, Poaceae) leaves reveal a distinct pathway operating in the camouflage1 mutant. Am. J. Bot. 97 357–364 10.3732/ajb.0900233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob B., Heber U. (1996). Photoproduction and detoxification of hydroxyl radicals in chloroplasts and leaves and relation to photoinactivation of photosystems I and II. Plant Cell Physiol. 37 629–635 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a028991 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joët T., Cournac L., Peltier G., Havaux M. (2002). Cyclic electron flow around photosystem I in C3 plants. In vivo control by the redox state of chloroplasts and involvement of the NADH-dehydrogenase complex. Plant Physiol. 128 760–769 10.1104/pp.010775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpinski S., Wingsle G., Karpinska B, Hällgren J. E. (2001). “Redox sensing of photooxidative stress and acclamatory mechanisms in plants,” in Regulation of Photosynthesis eds Aro E. M., Andersson B. (Dordrecht: Kluwer; ) 469–486 [Google Scholar]

- Khanna-Chopra R., Nutan K. K., Pareek A. (2013). “Regulation of leaf senescence: role of reactive oxygen species,” in Plant Development in Leaves During Growth and Senescence. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration Vol. 36 eds Biswal B., Krupinska K., Biswal U. C. (Dordrecht: Springer; ) 393–416 10.1007/978-94-007-5724-0_17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk J, Szymánska R. (2012). Singlet oxygen and non-photochemical quenching contribute to oxidation of the plastoquinone-pool under high light stress in Arabidopsis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817 705–710 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Külheim C., Ågren J., Jansson S. (2002). Rapid regulation of light harvesting and plant fitness in the field. Science 297 91–93 10.1126/science.1072359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurepa J., Hérouart D., Van Montagu M., Inzé D. (1997) Differential expression of CuZn- and Fe-superoxide dismutase genes of tobacco during development, oxidative stress and hormonal treatments. Plant Cell Physiol. 38 463–470 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lascano H. R., Casano L. M., Martín M., Sabater B. (2003). The activity of the chloroplastic Ndh complex is regulated by phosphorylation of the NDH-F subunit. Plant Physiol. 132 256–262 10.1104/pp.103.020321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A. (1999). “Oxidative stress as a regulator of environmental responses in plants,” in Plant Responses to Environmental Stress: from Phytohormones to Genome Organization ed. Lerner H. R. (New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc; ) 247–264 [Google Scholar]

- Martín M., Casano L. M., Sabater B. (1996). Identification of the product of ndhA gene as a thylakoid protein synthesized in response to photooxidative treatment. Plant Cell Physiol. 37 293–298 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a028945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín M., Casano L. M., Zapata J. M., Guéra A., del Campo E. M., Schmitz-Linneweber C., et al. (2004). Role of thylakoid Ndh complex and peroxidase in the protection against photo-oxidative stress: fluorescence and enzyme activities in wild-type and ndhF-deficient tobacco. Physiol. Plant. 122 443–452 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2004.00417.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martín M., Funk H. T., Serrot P. H., Poltnigg P., Sabater B. (2009). Functional characterization of the thylakoid Ndh complex phosphorylation by site-directed mutations in the ndhF gene. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787 920–928 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae D. G., Thompson J. E. (1983). Senescence-dependent changes in superoxide-anion production in illuminated chloroplasts from bean leaves. Planta 158 185–193 10.1007/BF01075253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthuramalingam M., Seidel T., Laxa M., Nunes de Miranda S. M., Gärtner F., Ströher E., et al. (2009). Multiple redox and non-redox interactions define 2-Cys peroxiredoxin as a regulatory hub in the chloroplast. Mol. Plant 2 1273–1288 10.1093/mp/ssp089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashilevitz S., Melamed-Bessudo C., Izkovich Y., Rogachev I., Osorio S., Itkin M., et al. (2010). An orange ripening mutant links plastid NAD(P)H dehydrogenase complex activity to central and specialized metabolism during tomato fruit maturation. Plant Cell 22 1977–1997 10.1105/tpc.110.074716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilo R. P., Campos-Vargas R., Orellana A. (2012). Assessment of Prunus persica fruit softening using a proteomics approach. J. Proteomics 75 1618–1638 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.11.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon P. J., Rich P. R. (2007). “Chlororespiratory pathways and their physiological significance,” in The Structure and Function of Plastids eds Wise R. R., Hoober J. K. (Berlin: Springer; ) 237–251 [Google Scholar]

- Ohe M., Rapolu M., Mieda T., Miyagawa Y., Yabuta Y., Yoshimura K., et al. (2005). Decline of leaf photooxidative stress tolerance with age in tobacco. Plant Sci. 168 1487–1493 10.1016/j.plantsci.2005.01.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orr W. C., Sohal R. S. (1994). Extension of life-span by overexpression of superoxide dismutase and catalase in Drosophila melanogaster. Science 263 1128–1130 10.1126/science.8108730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmond C. B. (1994). “What is photoinhibition? Some insights from comparison of shade and sun plants,” in Photoinhibition of Photosynthesis eds Baker N. R., Bowyer J. R. (Oxford: BIOS Scientific; ) 1–23 [Google Scholar]

- Overmyer K., Brosché M., Kangasjärvi J. (2003). Reactive oxygen species and hormonal control of cell death. Trends Plant Sci. 8 335–342 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00135-133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes M., Quiles M. J. (2013). Stimulation of chlororespiration by drought under heat and high illumination in Rosa meillandina. J. Plant Physiol. 170 165–171 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy R. W. (1994). “Photosynthetic response to sunflecks and light gaps: mechanism and constrain,” in Photoinhibition of Photosynthesis eds Baker N. R., Bowyer J. R. (Oxford: BIOS Scientific; ) 255–271 [Google Scholar]

- Puerto-Galán L., Pérez-Ruiz J. M., Ferrández J., Cano B., Naranjo B., Nájera V. A., et al. (2013). Overoxidation of chloroplast 2-Cys peroxiredoxins: balancing toxic and signaling activities of hydrogen peroxide. Front. Plant Sci. 4:310 10.3389/fpls.2013.00310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potikha T. S., Collins C. C., Johnson D. I., Delmer D. P., Levine A. (1999). The involvement of hydrogen peroxide in the differentiation of secondary walls in cotton fibers. Plant Physiol. 119 849–858 10.1104/pp.119.3.849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochazkova D., Sairam R. K., Srivastava G. C., Singh D. V. (2001). Oxidative stress and antioxidant activity as the basis of senescence in maize. Plant Sci. 161 765–771 10.1016/S0168-9452(01)00462-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quirino B. F., Noh Y. S., Himelblau E., Amasino R. M. (2000). Molecular aspects of leaf senescence. Trends Plant Sci. 5 278–282 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01655-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinbothe S., Reinbothe C., Parthier B. (1993). Methyl jasmonate-regulated translation of nuclear encoded chloroplast protein in barley (Hordeum vulgare L. cv. Salome). J. Biol. Chem. 268 10606–10611 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumeau D., Peltier G., Cournac L. (2007). Chlororespiration and cyclic electron flow around PSI during photosynthesis and plant stress response. Plant Cell Environ. 30 1041–1051 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01675.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabater B, Martín M. (2013). “Chloroplast control of leaf senescence,” in Plant Development in Leaves During Growth and Senescence. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration Vol. 36 eds Biswal B., Krupinska K., Biswal U. C. (Dordrecht: Springer; ) 529–550 [Google Scholar]

- Schaller F., Schalller A., Stintzi A. (2004). Biosynthesis and metabolism of jasmonates. J. Plant Growth Regul. 23 179–199 10.1007/s00344-004-0047x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serrot P. H., Sabater B, Martín M. (2008). Expression of the ndhCKJ operon of barley and editing at the 13th base of the mRNA of the ndhC gene. Biol. Plant 52 347–350 10.1007/s10535-008-0071-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serrot P. H., Sabater B, Martín M. (2012). Activity, polypeptide and gene identification of thylakoid Ndh complex in trees: potential physiological relevance of fluorescence assays. Physiol. Plant 146 110–120 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2012.01598.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh K. B., Foley R. C, Oñate-Sánchez L. (2002). Transcription factors in plant defense and stress responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5 430–436 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00289-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Breusegem F., Vranová E., Dat J. F, Inzé D. (2001). The role of active oxygen species in plant signal transduction. Plant Sci. 161 405–414 10.1016/S0168-9452(01)00452-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner D., Przybyla D., op den Camp R., Kim C., Landgraf F., Lee K. P., et al. (2004). The genetic basis of singlet oxygen-induced stress responses of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 306 1183–1185 10.1126/science.1103178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Loake G. J., Chu C. (2013). Cross-talk of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in plant programmed cell death. Front. Plant Sci. 4:314 10.3389/fpls.2013.00314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack C. (2007). Jasmonates: an update on biosynthesis, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. Ann. Bot. 100 681–697 10.1093/aob/mcm079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley J. F., Stanicka J., Cotter T. G. (2013). Recent advances in reactive oxygen species measurement in biological systems. Trends Biochem. Sci. 38 556–565 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. S., Lin C. P., Hsu C. Y., Wang R. J., Chaw S. M. (2011). Comparative chloroplast genomes of Pinaceae: insights into the mechanism of diversified genomic organizations. Genome Biol. Evol. 3 309–319 10.1093/gbe/evr026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapata J. M., Guéra A., Esteban-Carrasco A., Martín M., Sabater B. (2005). Chloroplasts regulate leaf senescence: delayed senescence in transgenic ndhF-defective tobacco. Cell Death. Differ 12 1277–1284 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapata J. M., Sabater B, Martín M. (1998). Identification of a thylakoid peroxidase which oxydized hydroquinone. Phytochemistry 48 1119–1123 10.1016/S0031-9422(98)00133-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zentgraf U. (2007). “Oxidative stress and leaf senescence,” in Senescence Processes in Plants ed. Gan S. (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; ) 69–86 [Google Scholar]

- Zentgraf U., Laum T., Miao Y. (2010). The complex regulation of WRKY53 during leaf senescence of Arabidopsis thaliana. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 89 133–137 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P., Zentgraf U. (2005). The correlation between oxidative stress and leaf senescence during plant leaf development. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 10 515–534 10.1007/s10343-004-0050-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]