Abstract

We demonstrate that optical trapping of multiple silver nanoparticles is strongly influenced by plasmonic coupling of the nanoparticles. Employing dark-field Rayleigh scattering imaging and spectroscopy on multiple silver nanoparticles optically trapped in three dimensions we experimentally investigate the time-evolution of the coupled plasmon resonance and its influence on the trapping stability. With time the coupling strengthens, which is observed as a gradual red-shift of the coupled plasmon scattering. When the coupled plasmon becomes resonant with the trapping laser wavelength, the trap is destabilized and nanoparticles are released from the trap. Modeling of the trapping potential and its comparison to the plasmonic heating efficiency at various nanoparticle separation distances suggests a thermal mechanism of the trap destabilization. Our findings provide insight into the specificity of three-dimensional optical manipulation of plasmonic nanostructures suitable for field enhancement, for example for surface enhanced Raman scattering.

Keywords: metal nanoparticle, optical trapping, optical heating, plasmonic coupling, dark-field spectroscopy

In 1986 Ashkin and colleagues have demonstrated that small objects can be confined or trapped within a certain volume using a single tightly focused laser beam1. Nowadays, optical trapping and optical manipulation of micro- and nano-objects are standard techniques widely used in biology, physics, chemistry and material sciences2,3. The contactless nature of optical forces is an advantageous peculiarity, enabling straightforward integration of optical trapping with optical imaging and spectroscopic techniques. In the simplest case optical trapping is used to “catch” an object of interest and “hold” it while imaging or spectroscopy is performed. Due to the object localization in the focal plane of the objective lens, the quality of the acquired images and spectroscopic data can be improved significantly. This approach is exceptionally beneficial in combination with spectroscopic techniques relying on the collection and analysis of weak optical signals, such as Raman scattering4. Micro-Raman spectroscopy combined with optical trapping has been successfully used to study aerosol particles5, chemical reactions in microdroplets6, living biological cells7, individual cellular organelles8 and erythrocytes9. Although Raman scattering detection efficiency can be greatly increased by means of trapping, the relatively low Raman scattering cross-sections result in long signal acquisition times (tens of seconds or even minutes), thus limiting performance and practical usability of this technique10. An elegant strategy11,12,13,14,15 to overcome this difficulty is to use surface enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) provided by optically assembled metal nanoparticles (NPs). This approach relies on the strong field enhancement in gaps between trapped nanoparticles. The essential prerequisite of SERS is plasmonic coupling appearing at small separation distances between metal nanoparticles resulting in field enhancement. Therefore, in order to integrate SERS or any other field enhancement effect with 3D optical trapping, the effect of the plasmonic coupling on optical trapping performance has to be understood.

Here, we study the influence of plasmonic coupling on optical trapping by combining 3D optical trapping with dark-field Rayleigh scattering spectroscopy, enabling us to investigate the interaction of metal NPs inside of an optical trap and its evolution in time. By trapping several silver nanoparticles we systematically observe plasmonic coupling which has a tendency to strengthen in time. The coupling strengthening is followed by the trap destabilization and prompt escape of the nanoparticles from the trap. Theoretical modeling suggests that trapping is destabilized thermally due to the increased absorption of the coupled plasmon at the trapping wavelength.

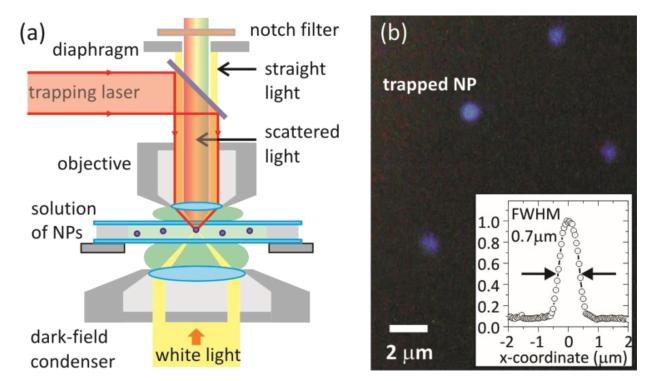

First, we introduce an experimental arrangement (Fig. 1a) suitable for dark-field Rayleigh scattering spectroscopy16 on optically trapped nanoparticles in 3D which is a challenge itself. Indeed, since optical trapping is relying on a gradient of the optical field density, a tight focusing of the trapping laser beam is required. This is provided by objective lenses with high numerical apertures (NAs). Typically, metal NPs are trapped in 3D using 1.3-1.4 NA objectives17,18. In contrast to optical trapping, dark-field microscopy is performed with objectives having NA < 1.2 to ensure that only scattered, but not straight, light is collected by the objective lens. The limitation is imposed by the highest existing NA = 1.2 of state-of-the-art dark-field condensers. This mutual incompatibility aspect of the two techniques straitened their integration so far. To resolve this issue, we propose to constrain the NA of the objective lens only in the imaging channel, remaining the NA high for the trapping laser. Due to the fact that most of the modern objectives are infinity corrected, the NA of such objectives can be varied by a diaphragm installed anywhere between the objective back aperture and the tube lens. We believe that the ease of implementing this solution will promote the Optical Trapping Dark-Field Microscope (OTDFM) to become a standard tool for simultaneous 3D optical manipulation and imaging/spectroscopy of metal nanostructures.

FIG. 1.

Dark-field Rayleigh scattering microscopy in a 3D optical trap. (a) Sketch of the experimental setup used for simultaneous 3D optical trapping and imaging of metal nanoparticles. (b) Typical true color video frame (50 frames per second) of a single trapped and three freely diffusing 40 nm silver nanoparticles. See video 1 in Supporting Information. Inset shows intensity profile across a trapped nanoparticle. Reduced imaging resolution is due to the decrease of NA in the imaging track by the diaphragm.

Our OTDFM is based on an up-right dark-field microscope (Zeiss Axiotech) described in detail elsewhere19 and equipped with a Ti:sapphire laser (Tsunami) operating in CW-mode at 808 nm. The laser beam is expanded by a homebuilt telescope to slightly overfill the back aperture of a Zeiss microscope objective (α-“Plan-Fluar”, 100x/1.45/0.17). A notch filter (Semrock, StopLine 808 nm, NF03-808E-25) is used to filter out scattering from the trapping laser. A diluted solution (1.5 · 10−3 M) of Ag NPs (40 nm in diameter, citrate-stabilized, BBI, extinction maximum at 440 nm with FWHM 110 nm) is sealed between two microscope cover slides and mounted on a XYZ-stage (Linos). To compensate for spherical aberrations in water20, index matching liquid with n = 1.572 (Cargille) is used on the objective side of the sandwich. Laser power in the range of 20-30 mW behind the objective is used to trap multiple Ag NPs. When the laser is switched on, Ag NPs diffusing freely in solution are attracted by the laser beam and trapped. A typical scattering image of one trapped and three freely diffusing Ag nanoparticles is shown in Fig. 1b, emphasizing an important peculiarity of the OTDFM – its wide-field essence. In other words, using the OTDFM NPs can not only be visualized inside but also around the trap, which is not possible with standard techniques2.

We have systematically performed both dark-field Rayleigh scattering spectroscopy and imaging of multiple Ag NPs sequentially diffusing into the trap. Images have been recorded with a digital camera (Canon EOS 500D) at 50 frames per second. Scattering spectra have been acquired using a spectrometer (Andor SpectraPro-300i) equipped with a CCD camera (Roper Scientific 1340/400) at 2 frames per second for tens of minutes to collect a statistically significant amount of observations, which is important considering the stochastic nature of the trap filling via Brownian motion. Due to the construction of our microscope we could perform either imaging or spectroscopy in one experiment, but not both of them at the same time.

40 nm Ag NPs are seen in a dark-field microscope as bright blue spots due to their plasmon resonance at 450 nm. Plasmonic coupling of Ag NPs can be observed in a dark-field microscope by naked eye as a change of the scattering color from blue to green or red. With our OTDFM it was possible to trap up to 5 Ag NPs in a single trap. In most of the cases the scattering color of multiple trapped Ag NPs remained blue suggesting no plasmonic coupling of the NPs. This means that for most of the NPs optical forces pushing NPs against each other are weaker than the electrostatic repulsion force provided by the negative surface charge of NPs. It has recently been revealed in 2D trapping experiments that interparticle interaction is very heterogeneous at the single NP level because of variations of the shape and surface properties from particle to particle21. Apparently due to this heterogeneity in 20% of the multiple trapping events we have observed plasmonic coupling of Ag NPs sequentially filling the trap, which resulted in a change of the scattering color from blue to green or red. From here on we will consider only the experiments where the plasmonic coupling has occurred because only those are relevant to understand an effect of plasmonic coupling on the optical trapping performance.

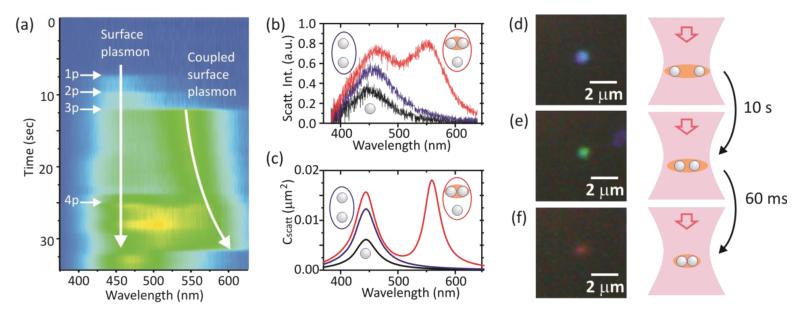

A characteristic sequence of scattering spectra taken from the trap is shown in Fig. 2a. Initially the trap is empty. After few seconds one Ag NP diffuses into the trap and gets trapped, showing a characteristic scattering spectrum of a single Ag NP peaking at 450 nm. Then a second NP is trapped, resulting in an increase of the scattering at 450 nm. Finally, a third NP is trapped causing both an increase of the scattering at 450 nm and a sudden appearance of a new band at 550 nm (Fig. 2b). This band corresponds to the coupled plasmon resonance of an Ag NP dimer with an interparticle separation distance of 2 nm. Indeed, we find the experimentally measured spectra (Fig. 2b) in good agreement with the calculated plane wave scattering cross section spectra (Fig. 2c). It is worth to notice that having three NPs trapped is not an absolute prerequisite for the plasmonic coupling to occur. We have observed the coupling happening when two or four particles were residing in the trap, which is a clear evidence of the sample heterogeneity. Due to the same reason the time needed for the plasmonic coupling to become visible in a scattering spectrum after several NPs are trapped varies considerably, from tens of seconds to almost instantaneous. Although the heterogeneity of the characteristics of individual NPs heavily influences the plasmonic coupling observed in a particular experiment, there is a general behavior valid for all the experiments. The distance between plasmonically coupled NPs reduces with time resulting in a gradual shift of the coupled plasmon towards longer wavelengths. In all cases we have observed, the shift of the coupled plasmon to the red part of the spectrum is followed by a rapid release of coupled NPs from the trap. A sequence of video frames preceded the release is shown in Fig. 2d-f. The coupled plasmon red-shifts non-linearly with time: the stronger the coupling the faster further shifting occurs. This finding can be understood in terms of the optical binding effect22, partly originating from an attractive force between two polarized NPs. Indeed, at small interparticle distances the attractive optical force increases as the separation distance reduces23. Moreover, optical heating of the dimer promotes desorption of citrate molecules from the NP surfaces, which, in turn, reduces the repulsion between NPs. The heating is more efficient at smaller separation distances. Both the increase of the attractive optical force and the decrease of the electrostatic repulsive force result in the faster joining of NPs at smaller separation distances.

FIG. 2.

Plasmonic coupling of optically trapped silver nanoparticles. (a) Time-evolution of the Rayleigh scattering spectrum measured from the optical trap. Observing intensity steps at the silver plasmon resonance ~ 450 nm the number of nanoparticles entering inside the trap can be counted. (b) Experimental scattering spectra of one (black), two (blue) and three (red) trapped silver nanoparticles. (c) Theoretical plane wave scattering cross section spectra of one (black), two non-coupled (blue) and two coupled (d = 2 nm) plus one non-coupled (red) silver nanoparticles, assuming randomly changing orientation of nanoparticles in space. (d)-(f) Evolution of scattering color in time: (d) true color image of three trapped nanoparticles at time zero, (e) 10 seconds after (d), (f) 60 milliseconds after (e). No particles were observed entering the trap during the color evolution process. Note, the spectra (a, b) and the images (d-f) are recorded in different experiments. See video 2 in Supporting Information.

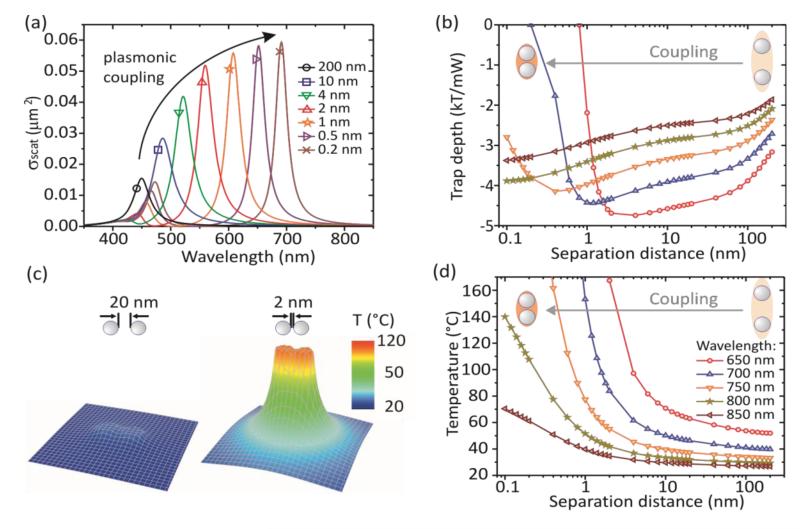

Summarizing our observations, several Ag NPs can simultaneously be trapped in 3D inducing plasmonic coupling between NPs, which is seen in Rayleigh scattering spectra. The strength of the coupling increases with time resulting in a gradual red shift of the coupled plasmon followed by NP release from the trap. In other words, plasmonic coupling, required for SERS and field enhancement, destabilizes the trap. There are two possible reasons for the destabilization of the trap upon plasmonic coupling of trapped NPs. First of all, a change of the balance between scattering and gradient forces affects trapping conditions. Indeed, the coupled plasmon resonance red-shifts upon reduction of the distance between NPs (Fig. 3a) and finally may become resonant with the trapping laser. This results in a strong pushing effect19 instead of trapping. The second possible reason for a destabilization of the trap is increased optical (plasmonic) heating24, 25 by the trapping laser via the coupled plasmon absorption. In order to estimate the impacts of both effects we have performed numerical calculations of the optical forces and the plasmonic heating of optically trapped and plasmonically coupled Ag NPs.

FIG. 3.

Modeling optical trapping of silver nanoparticle dimers. (a) Plane wave scattering cross section spectra of a single dimer assuming its random orientation at different separation distances. (b) Trapping potential depth per mW of the trapping laser power as a function of interparticle separation distance at different trapping wavelengths (for color coding see (d)). (c) Two examples of the temperature distribution around a plasmonically heated silver NPs dimer (25 mW, 800 nm, NA 1.45). (d) Maximum steady-state temperature of a silver dimer as a function of interparticle separation distance at different trapping wavelengths.

For simplicity we consider a dimer of Ag NPs trapped by a focused laser beam (NA=1.45, 25 mW), keeping material constants as used in the experiment. As a measure of the optical trapping stability we choose the depth of the trapping potential well (trap depth). It is equal to the minimum of the integral of the sum of the gradient and scattering forces26 along the beam propagation direction

| (1) |

where is the unit vector in the beam propagation direction. α = α′ + iα″ is the complex polarizability. In order to calculate the polarizability, we first simulate27, 28 the plane wave scattering (σscat) and absorption (σabs) cross sections of an Ag NPs dimer using Mie theory assuming random dimer orientation (Fig. 3a). Approximating the dimer by a point dipole the effective polarizability is found as29

| (2) |

| (3) |

where k is the wave-number of the trapping laser. The trap depth changes non-monotonously with the interparticle separation distance (Fig 3b). It slowly increases with decreasing distance due to the plasmonic coupling providing faster growth of α′ compared to α″. Upon approaching a separation distance realizing resonance conditions with a trapping laser the trap depth vanishes rapidly. Trapping is not possible in this situation. In Figure 3b for certain trapping wavelengths (≥ 750 nm) the trap depth does not turn to zero within the range of separation distances used for the calculations (0.1 – 100 nm). It vanishes at separation distances shorter than 0.1 nm where the model we use is not applicable reliable28. Obviously this technical issue does not affect our conclusions because in the limit of zero distance two touching 40 nm Ag NPs roughly represent a 40×80 nm Ag nanorod, having its longitudinal plasmon resonance in the near infrared30.

To access the effect of optical heating on the optical trapping in the case of plasmonically coupled NPs we performed finite-element calculations (COMSOL Multiphysics, module “Heat Transfer”) of the steady-state temperature raised by absorption of the trapping laser light. For these calculations we used exactly the same absorption cross sections (σabs) and laser beam parameters (NA=1.45, 25 mW) as for the trap depth estimates. The steady-state NPs temperature is dependent on the absorption cross section, which defines the amount of absorbed optical power, and on the relative arrangement of the NPs, influencing heat transfer away from the NPs (Fig. 3c). In case of only two NPs the increased optical heating due to the coupled plasmon absorption dominates the heating process and defines the steady-state temperature distribution. In contrast to this, in larger aggregates the accumulation of heat in the gaps between the NPs influences considerably the temperature distribution around NPs24.

The temperature of a plasmonically heated dimer increases as the interparticle separation distance decreases (Fig. 3d). At small interparticle separation distances the coupled plasmon becomes resonant with the trapping laser light, resulting in efficient heating up to temperatures exceeding the normal boiling temperature of water. At temperatures above 150 °C overheated water surrounding clusters of metal NPs evaporates and nucleation of vapor bubbles occurs31,32. It is worth to notice that water around a single NP can be heated up to more than 300 °C25 without boiling because of the enormously high NP surface curvature, which results in the large pressure of the surface tension forces around the NP. This pressure can reach tens of bars causing significant increase of the boiling temperature of water. The clusters of NPs have lower surface curvature compared to single ones and, therefore, the nucleation of vapor bubble occurs at lower temperatures. The bubble formation reduces cooling efficiency of the dimer resulting in an increased heating up to even higher temperatures. This leads to a destabilization of the trap. Also, at lower temperatures before the nucleation, inhomogeneous heating of the dimer may result in lower trapping stability due to strong thermophorethic forces33.

Both, the change of the balance between gradient and scattering forces and the increased plasmonic heating of coupled silver NPs at small separation distances cause trap destabilization and NP release. Comparing Figures 3b and 3d, we conclude that plasmonic heating dominates the destabilization process. Indeed, a 1 nm separation of two NPs trapped by a 700 nm laser provides strongest possible trapping at this wavelength, but the temperature reaches 170 °C which excludes any trapping. This conclusion has a general character and is valid for any trapping wavelength, although it cannot be quantitatively revealed for trapping laser wavelengths above 750 nm in frames of the Mie theory.

In conclusion, by having integrated 3D optical trapping with dark-field Rayleigh scattering spectroscopy we have experimentally demonstrated that optical trapping is strongly affected by plasmonic coupling of simultaneously trapped silver nanoparticles. The coupling is found to strengthen gradually with time resulting in an increased interaction of the coupled plasmon with the trapping light, which, in turn, destabilizes the trap. The modeling suggests a thermal mechanism being responsible for the trap destabilization. Therefore, the joint usage of 3D optical trapping and field enhancement provided by aggregates of metal nanoparticles is not as straightforward as it is seen at a first glance. Extra measures have to be taken to avoid an overlap between the coupled plasmon resonance and the trapping laser wavelength. Practically, separation distances between NPs have to be taken under fine control to realize plasmonic coupling avoiding its fast strengthening with time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the DFG through the Nanosystems Initiative Munich (NIM) and by the ERC through the Advanced Investigator Grant CHYMEM is gratefully acknowledged. We are thankful to Dr. Frank Jäckel for reading the manuscript and his helpful comments.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Two videos demonstrating optical trapping and plasmonic coupling of trapped Ag nanoparticles. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Ashkin A, Dziedzic JM, Bjorkholm JE, Chu S. Opt. Lett. 1986;11:288–290. doi: 10.1364/ol.11.000288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Dienerowitz M, Mazilu M, Dholakia K. J. Nanophoton. 2008;2:021875–32. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Jonáš A, Zemánek P. ELECTROPHORESIS. 2008;29:4813–4851. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Thurn R, Kiefer W. Applied Spectroscopy. 1984;38:78–8. (6) [Google Scholar]

- (5).Schweiger G. Journal of Aerosol Science. 1990;21:483–509. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Trunk M, Popp J, Lankers M, Kiefer W. Chemical Physics Letters. 1997;264:233–237. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Xie C, Dinno MA, Li Y. Opt. Lett. 2002;27:249–251. doi: 10.1364/ol.27.000249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ajito K, Torimitsu K. Lab Chip. 2002;2:11. doi: 10.1039/b108744b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Ramser K, Logg K, Goksör M, Enger J, Käll M, Hanstorp D. J Biomed Opt. 2004;9:593–600. doi: 10.1117/1.1689336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Petrov DV. J. Opt. A: Pure Appl. Opt. 2007;9:S139–S156. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Itoh T, Ozaki Y, Yoshikawa H, Ihama T, Masuhara H. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006;88:084102. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Svedberg F, Li Z, Xu H, Käll M. Nano Letters. 2006;6:2639–2641. doi: 10.1021/nl062101m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Yoshikawa H, Adachi T, Sazaki G, Matsui T, Nakajima K, Masuhara H. J. Opt. A: Pure Appl. Opt. 2007;9:S164–S171. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Tanaka Y, Yoshikawa H, Itoh T, Ishikawa M. Opt. Express. 2009;17:18760–18767. doi: 10.1364/OE.17.018760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Tong L, Righini M, Gonzalez MU, Quidant R, Käll M. Lab Chip. 2009;9:193. doi: 10.1039/b813204f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Sönnichsen C, Franzl T, Wilk T, von Plessen G, Feldmann J, Wilson O, Mulvaney P. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;88:077402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.077402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Hansen PM, Bhatia VK, Harrit N, Oddershede L. Nano Letters. 2005;5:1937–1942. doi: 10.1021/nl051289r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Bosanac L, Aabo T, Bendix PM, Oddershede LB. Nano Letters. 2008;8:1486–1491. doi: 10.1021/nl080490+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Urban AS, Lutich AA, Stefani FD, Feldmann J. Nano Letters. 2010;10:4794–4798. doi: 10.1021/nl1030425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Reihani SNS, Oddershede LB. Opt. Lett. 2007;32:1998–2000. doi: 10.1364/ol.32.001998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Tong L, Miljković VD, Johansson P, Käll M. Nano Letters. doi: 10.1021/nl1036116. 0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Dholakia K, Zemánek P. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010;82:1767. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Miljković VD, Pakizeh T, Sepulveda B, Johansson P, Käll M. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2010;114:7472–7479. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Stehr J, Hrelescu C, Sperling RA, Raschke G, Wunderlich M, Nichtl A, Heindl D, Kurzinger K, Parak WJ, Klar TA, Feldmann J. Nano Letters. 2008;8:619–623. doi: 10.1021/nl073028i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Bendix PM, Reihani SNS, Oddershede LB. ACS Nano. 2010;4:2256–2262. doi: 10.1021/nn901751w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Chaumet PC, Nieto-Vesperinas M. Opt. Lett. 2000;25:1065–1067. doi: 10.1364/ol.25.001065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Quinten M, Kreibig U. Surface Science. 1986;172:557–577. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Quinten M. MQAggr Version 1.1a, Dr. Michael Quinten Wissenschaftlich Technische Software (2005, 2006)

- (29).Draine BT. Astrophysical Journal, Part 1 (ISSN 0004-637X) 1988 Oct.vol. 333:848–872. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Gu GH, Suh JS. Langmuir. 2008;24:8934–8938. doi: 10.1021/la800845h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Lin C, Kelly M, Sibayan S, Latina M, Anderson R. IEEE J. Select. Topics Quantum Electron. 1999;5:963–968. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Zharov VP, Letfullin RR, Galitovskaya EN. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2005;38:2571–2581. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Zhang Y, Gu C, Schwartzberg AM, Chen S, Zhang JZ. Phys. Rev. B. 2006;73:165405. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.