Abstract

Understanding and controlling nonlinear coupling between vibrational modes is critical for the development of advanced nanomechanical devices; it has important implications for applications ranging from quantitative sensing to fundamental research. However, achieving accurate experimental characterization of nonlinearities in nanomechanical systems (NEMS) is problematic. Currently employed detection and actuation schemes themselves tend to be highly nonlinear, and this unrelated nonlinear response has been inadvertently convolved into many previous measurements. In this Letter we describe an experimental protocol and a highly linear transduction scheme, specifically designed for NEMS, that enables accurate, in situ characterization of device nonlinearities. By comparing predictions from Euler–Bernoulli theory for the intra- and intermodal nonlinearities of a doubly clamped beam, we assess the validity of our approach and find excellent agreement.

Keywords: Nanomechanical systems, nonlinear dynamics, coupled mode analysis, piezoelectric actuators, piezoresistive sensors, Euler–Bernoulli beam

Mechanical resonators are widely used for sensing applications,1–5 and they are especially promising for nanoscale devices,6,7 given their high quality factors, high resonance frequencies, and ultralow masses.8 However, as the geometric dimensions of a nanomechanical systems (NEMS) resonator are scaled downward, its mechanical dynamic range shrinks—due to larger thermomechanical noise amplitude and smaller nonlinear critical amplitude.9 Since nonlinearity often sets performance limits for resonant-sensing applications,8,10,11 the ability to experimentally characterize such properties is essential. Further, understanding nonlinear coupling to higher modes is important for applications requiring ultralow noise performance3 or multimode sensing.12 Critical to accurate characterization of nonlinearities is the use of a transduction scheme that is both sensitive and exceptionally linear over a wide operating range. These restrictions impose strict limitations on the choice of actuation and detection mechanisms.13

Quantitative studies of nonlinear mechanics at the nanoscale necessitate accurately calibrated transduction. Previous measurements of the nonlinear parameters of NEMS devices have employed theoretical estimates of electromechanical or optomechanical transduction efficiencies to deduce the magnitude of mechanical motion.9,14,15 These studies typically use idealized physical models that, in this context, are prone to significant error. Accordingly, accurate, in situ measurements of NEMS nonlinearities have not yet been reported.14–20

In this Letter, we describe a measurement protocol that permits accurate quantification of the nonlinear mechanical properties of NEMS devices. Our approach relies on engineering both a high degree of linearity between the applied input and measured output signals and the ability to accurately calibrate actuation and transduction responsivities. Our calibration is achieved using transducers that are strain-coupled and sufficiently sensitive to resolve thermomechanical fluctuations. The former property ensures highly linear actuation and detection over a large dynamic range,11 while the latter enables accurate calibration of the displacement sensitivity through application of the equipartition theorem. Using this fundamental relation eliminates the need for external calibration or for indirect physical models of the transduction mechanisms.

We employ metallic-piezoresistive (PZM) displacement sensing and piezoelectric (PZE) actuation to achieve in situ characterization of the transduction efficiencies of both intraand intermodal nonlinearities. The high sensitivity and large dynamic range provided by this approach enables characterization of the leading-order nonlinear parameters of individual resonant modes (nonlinear stiffness and nonlinear dissipation), the nonlinear intermodal coupling coefficients, and higher order nonlinear parameters. While optical displacement transduction at the nanoscale typically offers higher motional sensitivity than piezoresistive detection,21–23 it provides linear transduction over only a rather limited range. Semiconducting piezoresistive sensors can also suffer from resistive nonlinearities that complicate interpretation of measurements.24 By comparison, the metallic piezoresistive sensors used here eliminate such issues and are easily integrated into NEMS devices,11 circumventing the need for external instrumentation.

We assess the accuracy of our measurement protocol using a doubly clamped beam NEMS device. Although we study only a single idealized NEMS device, we emphasize that this approach is applicable to a wide variety of other nanoscale mechanical resonators, e.g. cantilevers,25 plate resonators, free–free beams, and torsional resonators.26–28 To calibrate device response, any extraneous drive signal is first removed by grounding the PZE actuator input; see the bottom of Figure 1a. The total noise signal measured then arises solely from thermomechanical fluctuations of the mechanical resonator and subsequent noise added from the PZM detector and amplifier circuits. These extrinsic noise sources are easily separated and evaluated, because (i) they represent independent stochastic processes, and (ii) the mechanical resonance of the NEMS device presents a distinct Lorentzian spectral response. These independent sources are discriminated by fitting the noise to a composite spectrum that includes an ideal Lorentzian response and an additional white noise background. The extracted Lorentzian response is integrated and substituted into the equipartition theorem to give the required displacement responsivity (with units m/V):

| (1) |

Here meff and ⟨V2⟩ are the effective mass and root-mean-squared (RMS) voltage at the required measurement position, ω is the angular resonant frequency, kB is Boltzmann’s constant, and T is the absolute temperature. The resonant frequency ω is obtained from the fit to a Lorentzian response (see above). Therefore, only the effective mass meff at the measurement position need be determined to complete the calibration step. It can be determined through careful measurements of device dimensions in conjunction with a expression for meff, which can be derived analytically for simple geometries. For complex devices, finite element analysis is required to accurately determine meff. For the particular device in this study, deviations between theory and FEM analysis become significant only for a large mode number.

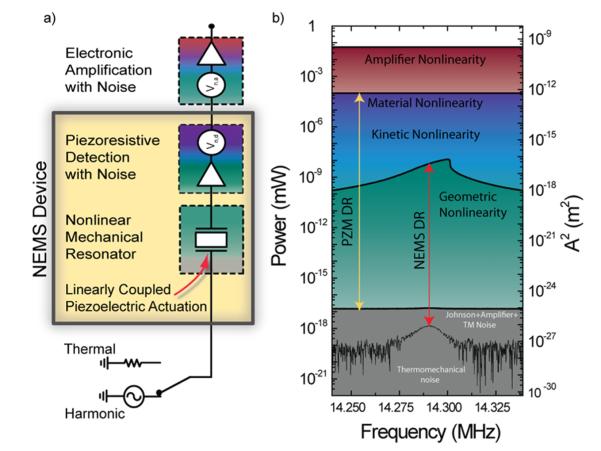

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of measurement design and protocol. When the switch is set to “Thermal”, the device is passively excited by thermal fluctuations. The resulting mechanical motion is transduced into electronic signals via the piezoresistive detector, which can be amplified through use of an external electronic amplifier. Other sources of noise from the detection and amplification exist. Setting the switch to “Harmonic” actively excites the device enabling interrogation of nonlinear response. (b) Illustration of relevant system dynamic ranges. The thermomechanical noise (bottom of red arrow) is extracted from the total noise spectrum (bottom of yellow arrow) and used to calibrate the right-hand vertical axis within the dynamic range (DR) of the metallic piezoresistor (PZM). The upper limit of the DR of the NEMS device is defined by the nonlinear critical amplitude and clearly resides within PZM DR. This enables measurement of the nonlinear properties of the device.

This calibration step enables quantification of the NEMS device displacement under active excitation that is maintained within the metallic-piezoresistive dynamic range (PZM DR); see Figure 1b. Importantly, placement of the metallic piezoresistive sensors must be optimized so that the PZM DR covers the regime in which mechanical nonlinearities in the NEMS device are observed, as also illustrated in Figure 1b. To facilitate quantitative measurement of mechanical nonlinearities in the NEMS device, linearity in the actuation scheme is also required. The in situ piezoelectric actuation employed in our studies provides linearity over both a large displacement range and frequency bandwidth.29

The methodology described above enables our measurement of the leading-order nonlinear stiffness coefficients for the first three out-of-plane flexural modes of a doubly clamped beam NEMS resonator. These measurements are compared to the predictions of Euler–Bernoulli beam theory for the nonlinear coefficients λpq obeying the equation,

| (2) |

where ΔΩp is the fractional frequency shift of mode p, and Amax,q is the maximum RMS displacement of the frequency response of mode q. Note that the Einstein summation convention is not used throughout. Calculations of the nonlinear coefficients λpq using Euler–Bernoulli theory gives (see Supporting Information)

| (3) |

where

Here δpq is the Kronecker delta function, L is the device length, t is the thickness, w is the width, T is the average built-in stress of the materials, E is the Young’s modulus of both materials, and I is the areal moment of inertia. Additionally, with Φp(ξ) is the mode amplitude, normalized according to the constraint ; the length scale for normalized coordinate along the beam axis, ξ, is L.

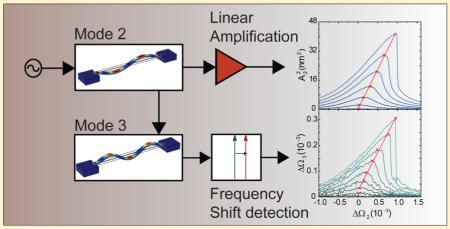

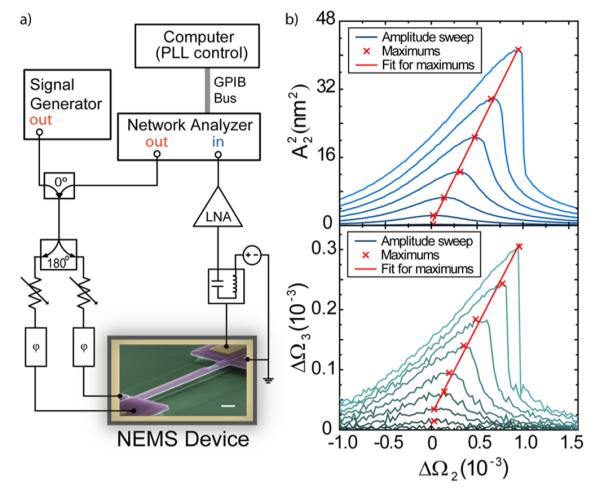

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the piezoelectric doubly clamped beam device is shown in Figure 2a. The scale bar is 1 μm, and the device dimensions L × t × w are 10 μm × 0.21 μm × 0.47 μm. It is patterned from an aluminum nitride (AlN)/molybdenum (Mo)/Silicon-On-Insulator (SOI) multilayer; fabrication details and the multilayer structure are described elsewhere.30,31 For the noise data we set the input of the NEMS to ground, “Thermal” as shown in Figure 1a. The noise output from the NEMS is taken with an Agilent 4395 spectrum analyzer, with bandwidth set between 10 Hz and 1 kHz, depending on the mode number of the device. The driven response, when the input is set to “Harmonic” as in Figure 1a, is taken with a single lock-in measurement with a Agilent 3577A network analyzer, using output voltages between 0.01 V and 1 V peak. Data presented in Figure 1b are obtained from this device, and they show that the range of displacements above and below the critical amplitude (i.e., at the Duffing bifurcation point) is nested within the PZM DR. Therefore, by measuring the driven response of each mode of this device, we can directly measure the intramodal nonlinear coefficients using ΔΩp = λppAmax,p2. The frequency response curves related to these measurements for mode 2 (i.e., p = 2) are given in the top graph of Figure 2b. Note that the horizontal axis in this graph is simply a renormalization of the applied drive frequency centered on the linear-regime resonant frequency of mode 2. The data used for characterization of the intermodal coefficients from Table 1, are used with the circuit presented in Figure 2a. Here we sweep the frequency of one mode with an Agilent 33250 signal generator and detect the frequency shift of another mode with a digital phase locked loop (PLL). The PLL circuit uses an Agilent 3577A network analyzer to probe the phase response of the device.

Figure 2.

(a) Circuit diagram for measurement of intermodal nonlinearities in doubly clamped PZE-actuated/PZM-sensed beam; intramodal nonlinearities are measured without using this circuit; see Figure 1a. A signal generator is used to excite the device at a range of frequencies around the resonance of mode q, while the frequency of mode p is measured using a network analyzer with a digital PLL. (b) Example measurement of intra- and intermodal nonlinearities. Data in the upper graph is due to the intramodal nonlinearity of the second mode. Data in the bottom graph shows the effect of intermodal nonlinearity on the frequency shift of the third mode due to excitation of the second mode. Comparing these two data sets enables the intermodal nonlinearity coefficient to be extracted.

Table 1.

Measured (Theoretically Calculated) Nonlinear Stiffness Coefficients λpq (10−5 nm−2) for the First Three Out-of-Plane Flexural Modes of the Doubly-Clamped NEMS Devicea

| q = 1 | q = 2 | q = 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| p = 1 | 0.53 ± 0.01 (0.53) |

1.76 ± 0.36 (1.45) |

3.51 ± 0.47 (3.59) |

| p = 2 | 0.18 ± 0.01 (0.186) |

1.16 ± 0.03 (1.16) |

1.77 ± 0.13 (1.65) |

| p = 3 | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.124) |

0.35 ± 0.06 (0.445) |

1.43 ± 0.07 (1.43) |

Uncertainties originate from the linear fits to the measured response, e.g., see Figure 2b. Monitored modes (p); driven modes (q).

The intermodal coefficients characterize how nonlinear coupling induces, from the RMS displacement of one mode, a fractional frequency shift of another mode, i.e., p ≠ q in eq 2. The fractional frequency shift of mode p in eq 2 is measured under low excitation, to ensure a linear response in this mode, and that the nonlinearity excited in the beam is solely due to mode q. This enables measurement of the intermodal nonlinear coefficient, λpq, without distortion from the intramodal nonlinearity arising from λpp. In contrast, mode q is excited at larger amplitude to induce a nonlinear response in the beam. While direct measurement of the intermodal coefficient is possible, analogous measurement of the intramodal coefficients presents a more formidable challenge because two modes would need to be monitored simultaneously.

Note that the fractional frequency shift of mode p is proportional to the amplitude squared of mode q, as in eq 2. Consequently, the intermodal coefficient can be obtained by comparing the upper graph of Figure 2b to measurements of the fractional frequency shift of mode p vs the drive frequency of mode q. This is, of course, true only if the frequency separation between the modal resonance peaks is much larger than their spectral widths—ensuring that no other modes are significantly excited. The lower graph of Figure 2b gives this measurement for excitation of mode 2 at a range of frequencies, and detection of the fractional frequency shift of mode 3, i.e., p = 3, q = 2 in eq 2. Comparing the two graphs in Figure 2b clearly demonstrates their identical shape. Importantly, these two graphs need not be measured simultaneously. The required nonlinear coefficient λpq can be obtained by fitting a straight line to the maxima of the lower graph of Figure 2b. The slope of this line is clearly βpq = ΔΩp/ΔΩq. Substituting this expression into eq 2 then gives the required result: λpq = βpqλqq.

Measurements using the procedure described above and calculations from Euler–Bernoulli theory, eq 3, for the intermodal and intramodal coefficients are given in Table 1. Intramodal coefficients fall on the main diagonal only. Note the excellent agreement between theory and measurement for these coefficients, with all predictions residing within measurement uncertainty. While good agreement is also found for the intermodal coefficients (the off-diagonal entries), measurement uncertainty in this case is larger. The reason for this is evident from the lower graph of Figure 2b, where the uncertainty in defining the straight line is greater, due to the lower signal-to-noise ratio of the measurements.

We have demonstrated design principles and a measurement protocol for obtaining accurate in situ characterization of the nonlinear properties of NEMS resonators. Our approach utilizes PZM displacement transduction and piezoelectric actuation to accurately and independently calibrate the driven motion of the device. These inherently linear schemes facilitate measurement interpretation and obviate the need for external transduction. We believe our study is the first confirmation of the quantitative predictions of Euler–Bernoulli theory for tension-induced geometric nonlinearities; direct and accurate measurements of the nonlinear intra- and intermodal stiffness coefficients for the first three out-of-plane flexural modes of doubly clamped NEMS beams are obtained. Our comparison validates the use of Euler–Bernoulli theory for quantitative characterization of the nonlinear mechanical properties of nanoscale mechanical devices and will be useful in evaluation of nonlinear properties and mode-coupling for advanced NEMS applications.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank S. Hanay and M. Cross for useful suggestions and discussions. L.G.V. acknowledges financial support from the European Commission (PIOF-GA-2008-220682) and Prof. A. Boisen. J.E.S. acknowledges support from the Australian Research Council grants scheme.

Footnotes

Supporting Information A brief derivation of the nonlinear coefficients using Euler–Bernoulli theory. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Notes The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Lang HP, Baller MK, Battiston FM, Fritz J, Berger R, Ramseyer JP, Fornaro P, Meyer E, Guntherodt HJ, Brugger J, Drechsler U, Rothuizen H, Despont M, Vettiger P, Gerber C, Gimzewski JK. In The nanomechanical NOSE; MEMS ‘99. Twelfth IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems; Jan 17–21, 1999.pp. 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Naik AK, Hanay MS, Hiebert WK, Feng XL, Roukes ML. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009;4(7):445–450. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Rugar D, Budakian R, Mamin HJ, Chui BW. Nature. 2004;430(6997):329–332. doi: 10.1038/nature02658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Burg TP, Godin M, Knudsen SM, Shen W, Carlson G, Foster JS, Babcock K, Manalis SR. Nature. 2007;446(7139):1066–1069. doi: 10.1038/nature05741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Arlett JL, Myers EB, Roukes ML. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011;6(4):203–215. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Jensen K, Kim K, Zettl A. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008;3(9):533–537. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Chaste J, Eichler A, Moser J, Ceballos G, Rurali R, Bachtold A. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012;7(5):301–304. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ekinci KL, Roukes ML. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2005;76:061101. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Kozinsky I, Postma HWC, Bargatin I, Roukes ML. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006;88(25):253101. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ekinci KL, Huang XMH, Roukes ML. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004;84(22):4469–4471. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Li M, Tang HX, Roukes ML. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007;2(2):114–120. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hanay MS, Kelber S, Naik AK, Chi D, Hentz S, Bullard EC, Colinet E, Duraffourg L, Roukes ML. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012;7(9):602–608. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).For example, capacitive detectors are linear only when the mechanical displacement is much smaller than the capacitive gap. However, the gap dimension must be kept small to ensure that capacitive transducers are sufficiently sensitive to measure nanoscale motion. This leads to an inherent compromise between transducer sensitivity and linearity.

- (14).Westra HJR, Poot M, van der Zant HSJ, Venstra WJ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010;105(11):117205. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.117205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Eichler A, Moser J, Chaste J, Zdrojek M, Wilson Rae I, Bachtold A. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011;6(6):339–342. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Eichler A, del Álamo Ruiz M, Plaza JA, Bachtold A. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;109(2):025503. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.025503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Lulla KJ, Cousins RB, Venkatesan A, Patton MJ, Armour AD, Mellor CJ, Owers-Bradley JR. New J. Phys. 2012;14(11):113040. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Antoni T, Makles K, Braive R, Briant T, Cohadon PF, Sagnes I, Robert-Philip I, Heidmann A. Europhys. Lett. 2012;100(6):68005. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Venstra WJ, Westra HJR, Zant H. S. J. v. d. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010;97(19):193107. doi: 10.1063/1.3516469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Venstra WJ, van Leeuwen R, van der Zant HSJ. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012;101(24):243111–4. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Eichenfield M. Dissertation (Ph.D.) California Institute of Technology; Pasadena, CA: 2010. Cavity optomechanics in photonic and phononic crystals: engineering the interaction of light and sound at the nanoscale. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Kouh T, Karabacak D, Kim DH, Ekinci KL. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005;86(1):013106–013106-3. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Li M, Pernice WHP, Xiong C, Baehr-Jones T, Hochberg M, Tang HX. Nature. 2008;456(7221):480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Matsuda K, Suzuki K, Yamamura K, Kanda Y. J. Appl. Phys. 1993;73(4):1838–1847. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Villanueva LG, Karabalin RB, Matheny MH, Chi D, Sader JE, Roukers ML. Nonlinearity in nanomechanical cantilevers. Phys. Rev. B. 2012;87:024304. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Evoy S, Carr DW, Sekaric L, Olkhovets A, Parpia JM, Craighead HG. J. Appl. Phys. 1999;86(11):6072–6077. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Barton RA, Ilic B, van der Zande AM, Whitney WS, McEuen PL, Parpia JM, Craighead HG. Nano Lett. 2011;11(3):1232–1236. doi: 10.1021/nl1042227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Huang XMH, Prakash MK, Zorman CA, Mehregany M, Roukers ML. In Free-free beam silicon carbide nanomechanical resonators. 12th International Conference on TRANSDUCERS, Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems; Jun 9–12, 2003.2003. pp. 342–343. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Don L,D. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 2001;88(3):263–272. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Karabalin RB, Matheny MH, Feng XL, Defaÿ E, Le Rhun G, Marcoux C, Hentz S, Andreucci P, Roukes ML. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009;95(10):103111. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Villanueva LG, Karabalin RB, Matheny MH, Kenig E, Cross MC, Roukes ML. Nano Lett. 2011;11(11):5054–5059. doi: 10.1021/nl2031162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.