Abstract

In its most basic form an oscillator consists of a resonator driven on resonance, through feedback, to create a periodic signal sustained by a static energy source. The generation of a stable frequency, the basic function of oscillators, is typically achieved by increasing the amplitude of motion of the resonator while remaining within its linear, harmonic regime. Contrary to this conventional paradigm, in this Letter we show that by operating the oscillator at special points in the resonator’s anharmonic regime we can overcome fundamental limitations of oscillator performance due to thermodynamic noise as well as practical limitations due to noise from the sustaining circuit. We develop a comprehensive model that accounts for the major contributions to the phase noise of the nonlinear oscillator. Using a nano-electromechanical system based oscillator, we experimentally verify the existence of a special region in the operational parameter space that enables suppressing the most significant contributions to the oscillator’s phase noise, as predicted by our model.

Advances in time and frequency measurement have closely paralleled technological progress. However, since the appearance of quartz-crystal-based oscillators [1], very few conceptual innovations have been introduced. quartz crystal resonators (their frequency-determining elements) operate at the highest possible signal to noise ratio in order to minimize phase noise. The resonator is always kept within its linear regime, which results in oscillator phase noise being inversely proportional to the oscillator carrier power. Ongoing technological evolution requires a dramatic reduction in the oscillator size and power, preferably without performance degradation. Micro- and nano-electromechanical systems [2–4] are increasingly being considered as valid alternatives to quartz as the frequency-determining element. However, with the reduction in size, their dynamic range also diminishes because nonlinear effects manifest at lower amplitudes [5,6]. This has proven interesting for fundamental studies [7–9], but is typically considered detrimental to the oscillator performance [10,11]. However, several techniques have been proposed to utilize nonlinear behavior in the mechanical element in order to improve oscillator performance. These proposals rely on the local elimination of frequency to energy dependence [12], evasion of amplifier noise [13], use of either parametric feedback [14], nondegenerate parametric drive [15], or coupling to internal resonances [14,16].

In this Letter, we analyze all the contributions to the phase noise in an oscillator based on a nonlinear resonator. We predict the existence of a special region in the parameter space, above the nonlinear threshold, where the dominant contributions to the phase noise are suppressed. We construct such an oscillator from a nanomechanical doubly clamped beam resonator and measure its phase noise. We find good agreement with our theoretical model and unequivocally confirm experimentally the existence of such a special region, where the phase noise performance is improved beyond the limitations of the linear regime. Our findings contravene conventional phenomenological wisdom, which assumes that operation beyond the threshold of nonlinearity necessarily degrades phase noise. Indeed, by operating the oscillator in this region, the signal level can be increased to large values without the conventionally expected performance degradation. It is therefore possible to overcome fundamental limitations of oscillator performance due to thermodynamic noise.

Because we are interested in slow modulation dynamics of an oscillator constructed from a high-Q resonator, we introduce a dimensionless slow time scale T = εω0t with ε a small expansion parameter chosen for convenience as detailed below and ω0 the resonance frequency of the resonator. The resonator signal amplitude is given by x(t) = x0Re[A(T)eiω0t] + · · ·, with x0 being a convenient scale factor as detailed below, Re standing for real part, and the ellipses (…) representing negligible harmonics generated by the resonator nonlinearity. Our theoretical analysis is based on the dimensionless equation of motion for the complex amplitude A(T) = a(T)eiφ(T) of the resonator dynamics

| (1) |

The first two terms on the right-hand side of Eq. (1) arise, respectively, from the linear dissipation and the essential nonlinearity of the resonator, i.e., the dependence of the resonance frequency on the amplitude of motion, and α and γ are parameters that depend on the specific resonator. The third term represents the feedback loop drive projected onto the slow equation of motion of the resonator. The behavior of the feedback loop is then described by the gain function F(a) and the phase delay Δ relative to the resonator phase. Equation (1) relies on the assumption of weak feedback (just sufficient to overcome the small dissipation of the high-Q resonator); then the amplitude of the motion is small, so that nonlinear frequency shifts are comparable to the linear resonance line width, but small compared to the resonance frequency ω0.

Equation (1) is derived from the basic equation of motion using secular perturbation theory [17], and our results are generally applicable. However, to make the discussion concrete we will focus on our particular experimental demonstration, based on a nanoelectromechanical system (NEMS) resonator. The parameters γ and α are related to the quality factor Q and to the nonlinear coefficient α˜ in the spring constant and, in our particular implementation, they are defined by

| (2) |

with m the mass of the resonator. For the perturbation theory to be consistent γ and α must be O(1) quantities. Thus we choose scale factors ε = Q−1 and so that in the absence of fluctuations γ and α are unity.

We focus our study on a heavily saturated oscillator, that is, one in which the system gain is designed to keep the feedback magnitude constant regardless of the amplitude of motion. This scheme is also known as a phase feedback oscillator [13,18], which is commonly used to suppress one quadrature of the amplifier noise. It also provides, in principle, a quantum nondemolition method [19] to track the resonator phase. For saturated feedback, Eq. (1) reduces to

| (3) |

with s the saturation level. This equation can be separated into equations for the magnitude a and phase φ

| (4) |

For steady state oscillations da/dT = 0, dφ/dT = Ω, with Ω giving the frequency offset of the oscillations from the linear resonance frequency, in units of the resonator line width. Thus, Eqs. (4) yield expressions for the oscillation amplitude and frequency offset that define the limit cycle

| (5) |

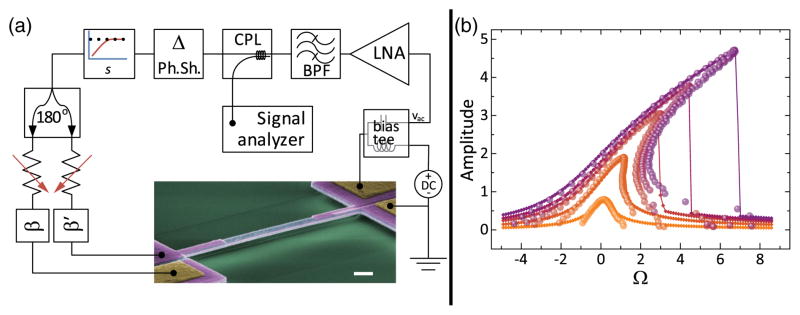

Our experimental demonstration is performed using a piezoelectric NEMS doubly clamped beam made from an aluminum nitride (AlN) and molybdenum (Mo) multilayer (Fig. 1). In our experimental implementation [Fig. 1(a)], both the phase delay Δ and the power of the feedback s can be externally and independently controlled. This permits full exploration of the input parameter space of the feedback oscillator. We first confirm that the system behaves according to predictions for a heavily saturated oscillator [Fig. 1(b)]. For periodic solutions φ = φ0 + ΩT the equation of motion (3) for the heavily saturated oscillator is identical to the one for an open-loop resonator externally driven with a periodic source of constant magnitude s; then Δ represents the phase difference between the resonator motion and the drive. As is known for nonlinear resonators, when the driving force is sufficiently large, the system can bifurcate into three possible solutions at a given drive frequency. two of these are stable, and one is unstable [17]. In the case of the heavily saturated oscillator, the system also presents three possible values for the amplitude of oscillation at a given frequency above a threshold feedback power. However, in this latter case, the resonator-drive phase difference is itself determined by the feedback, and both amplitude and frequency are single-valued functions of this phase. Therefore, all three operating conditions at the same frequency might be stable [18], and this is indeed confirmed by a stability analysis using Eq. (3), and by our measurements [Fig. 1(b)].

FIG. 1.

(color online). (a) Schematic diagram of the feedback system. Motion detection is performed using metallic piezoresistive effect, the beam is driven by piezoelectric actuation [6]. Components include a phase delay (Δ), a variable limiter (s), a 180° power splitter, variable attenuators and phase shifters (β). Colored SEM micrograph shows the doubly-clamped AlN multilayer beam used for experiments (420 nm wide, 9 μm long, 210 nm thick). At 300 K and 1 mtorr its resonance frequency is f0 = 12.63 MHz and quality factor is Q = 1600. The scale bar is 500 nm. (b) (Squares and solid lines) Resonant response of the open-loop (driven) resonator for five different driving powers (s = 0.5, 1.22, 3.06, 4.73, 7.23). (Spheres) Oscillation amplitude vs oscillation frequency for the closed-loop system in (a), taken at the same values of s as the open-loop data while sweeping the phase Δ. As predicted by theory, both responses overlap where the open-loop response is stable. Using the closed-loop system, access to otherwise unstable operation points is possible. Plotted magnitudes are scaled following the Supplemental Material [23].

We now turn to the noise analysis of the feedback-sustained oscillator. In general, the noise, when projected onto the slow dynamics, is represented by adding a complex stochastic term ΞR(T) + iΞI(T) to the evolution in Eq. (1). The performance of an oscillator is typically characterized by the spectral density of its phase noise Sφ or the variance [δφ(T + τ) − δφ(T)]2 of the phase deviation δφ(T) = φ(T) − ΩT, which can be found by solving Eq. (1) with the additional stochastic terms.

For our saturated feedback NEMS oscillator it is possible to distinguish two types of noise affecting the phase diffusion of the oscillator. thermomechanical noise and parameter noise [20,21]. Thermomechanical noise is caused by the Brownian motion of the resonator. it enters the equation as a random, perturbative force and affects independently both quadratures of the oscillation with the same intensity. Its projection in quadrature to the displacement (the phase direction) always affects the oscillator performance (hereafter called the direct thermomechanical contribution), whereas its projection in the amplitude direction affects the phase noise only through amplitude-phase conversion [21]. This is typically assumed to be dominant at higher amplitudes when nonlinear resonators are used. Parameter noise is caused by fluctuations in the parameters pi determining the oscillator operational point (in our case γ, s, α, and Δ). Each independent noise source n is described by stochastic terms va,nΞn(T), vφ,nΞn(T) added to the amplitude and phase evolution equations (4), respectively, where the noise vector (va,n, vφ,n) gives the relative strength of the nth noise force in the amplitude and phase quadratures.

Two key points lead to our predictions for reducing the frequency precision degradation. First, for small frequency offsets compared to the amplitude relaxation rate (i.e., the resonator line width) the time derivative term da/dT can be neglected in calculating the amplitude fluctuations. Second, the evolution terms fa, fφ in Eqs. (4) do not depend on the phase φ. this is the basic phase symmetry of the limit cycle when Eq. (1) applies. These lead directly to a long-time phase diffusion, which is given by

| (6) |

with

| (7) |

and with In the noise intensity defined by

| (8) |

These results can be formally derived using a spectral analysis of the stochastic fluctuations, or following the methods of Demir et al. [20] for phase diffusion of a general limit cycle. Although Eq. (8) corresponds to white noise, one can generalize these results to other types of noise spectra, such as pink noise, i.e., 1/f [21].

The first term in Eq. (7) represents the direct effect of the nth noise source on the oscillator phase; the second term accounts for phase diffusion due to amplitude-phase conversion. Furthermore, for noise due to fluctuations in the parameter pi, the noise vector becomes vφ,i = ∂fφ/∂pi, va,i = ∂fa/∂pi, and, using the stationary amplitude approximation fa ~ 0, the expression for Dn reduces to

| (9) |

so that the stochastic phase diffusion can be evaluated immediately from the dependence of the oscillator frequency on the parameters. Alternatively, for thermomechanical noise that is purely in the amplitude quadrature (va = 1, vφ = 0), the coefficient that quantifies the strength of amplitude-phase conversion is

| (10) |

whereas for thermomechanical noise that is purely in the phase quadrature (va = 0, vφ = 1/a) the strength of direct thermomechanical noise contribution to the phase noise is Ddirect = 1/a2.

Combining the above results, the total phase noise as a function of the offset frequency δν is given by the sum

| (11) |

where νc is the carrier frequency and the parameters Dn have been defined above and the expressions are expanded in Table I. Note that the dependence on δν−2 emerges from the assumption of the noise terms being white. As we show elsewhere [21], a similar result is obtained if colored noise is considered.

TABLE I.

Diffusion coefficients for different physical mechanisms affecting phase noise.

| Type of noise | Diffusion susceptibility to a parameter | Noise intensity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermomechanical-direct |

|

ITh | |

| Thermomechanical-A-φ conversion |

|

ITh | |

| Parameter noise-Δ |

|

IΔ | |

| Parameter noise-s |

|

Is | |

| Parameter noise-α |

|

Iα | |

| Parameter noise-γ |

|

Iγ | |

| Parameter noise-ω0 |

|

Iω0 |

Equation (11) shows two strategies for oscillator performance optimization. minimization of either In or Dn. In this Letter, we focus on the latter—both for its general applicability and because the Dn terms are experimentally controllable parameters, whereas the In coefficients are dictated by the environment. Further, we pay special attention to the terms that are typically considered to be dominant. Ddirect, Da, and DΔ.

The direct contribution of thermomechanical noise has been widely analyzed in the literature and is suppressed by maximizing the oscillator amplitude (a). Noise in the feedback phase (Δ) can be canceled at the operational points where DΔ = (dΩ/dΔ)2 = 0. Greywall et al. and Yurke et al. [13,22] proposed the operation at the bifurcation point, where this condition is satisfied, and showed that near such a Duffing critical point (DCP) the oscillator’s phase is unaffected by fluctuations in Δ. We extend this understanding further and note that above the threshold of nonlinearity, for each saturation value, there are actually two values of Δ for which dΩ/dΔ = 0. At the bifurcation (s = sc), the case considered by Greywall et al. and Yurke et al. [13,22], both of these DCPs are degenerate at Δ = 120°. However, for larger feedback powers, one family of DCPs approaches Δ = 90° while the other one tends toward Δ = 180° (see Supplemental Material, Fig. S2 [23]).

From Eq. (10) we conclude that amplitude-phase converted thermal noise can be canceled at the points where ∂Ω/∂a = 0 (note that this is not where the total derivative vanishes, i.e., dΩ/da = 0) [24]. This term has always been considered to be zero when the resonator used is linear and assumed to be unavoidable when the resonator used is nonlinear. In fact, we show that for linear resonators this is only true for a particular feedback phase, Δ = 90°, and, equivalently, for nonlinear resonators there also exists a value of Δ for each feedback power such that ∂Ω/∂a=0, effectively detaching amplitude and phase. We call this the amplitude detachment point (ADP). Importantly, according to our model, the location of the ADP turns out to be very close to the second aforementioned family of DCPs (see Supplemental Material, Fig. S2 [23]); therefore, this yields a region where two of the major contributions to phase noise can be drastically reduced.

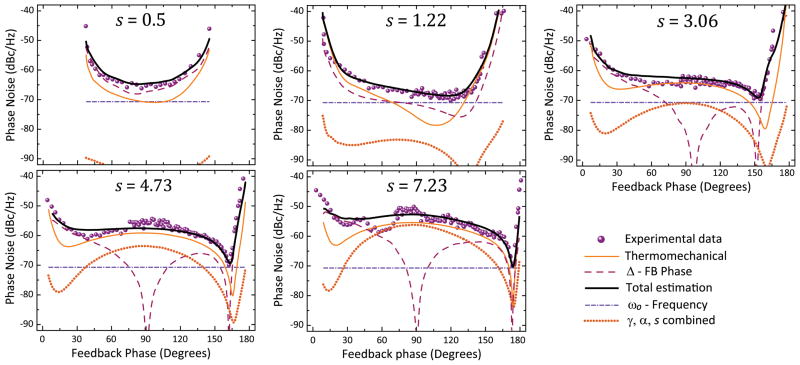

In order to experimentally verify the predicted behavior, we measure the phase noise of the heavily saturated oscillator from Fig. 1 for different values of the feedback power s and phase Δ. Figure 2 shows the results obtained at δν = 1 kHz offset from the carrier (colored spheres). Solid black lines correspond to the predictions of the model described above (and in the Supplemental Material [23]). We find good agreement between the experiments and theory. In order to perform such a quantitative comparison, we first independently estimate ITh and IΔ, and subsequently find an upper bound for the value of Is. We then choose the value for Iω0 to provide good agreement in the region close to the ADP. Finally, we perform minor adjustments (causing ±3 dBc/Hz in the phase noise) to get the best possible match (see Supplemental Material [23], Sec. C). Figure 2 indicates that if the resonator is operated above its onset of nonlinearity (s = sc = 1.433) the phase noise near the conventional operational point (Δ = 90°) is indeed increased. However, when operating near the second set of DCPs and close to the ADP, a significant performance improvement beyond what is possible in the linear regime can be achieved.

FIG. 2.

(color online). Experimental phase noise at δν = 1 kHz offset from the carrier, plotted as 10log10[Sφ(1 kHz)], for different saturation power levels (spheres), superimposed on the total theoretical estimate (black line). The calculated contributions to the total phase noise from the different sources are also shown. Thermomechanical noise (direct and amplitude-phase converted contributions plotted together) and noise in Δ dominate most of the phase range except in the region close to the amplitude-phase detachment point, where fluctuations in frequency become apparent. Fluctuations in saturation (s), dissipation (γ), and nonlinearity (α) are plotted jointly for the sake of simplicity. Noise intensity estimates are detailed in the Supplemental Material [23]. The symmetric behasvior with respect to Δ = 90° seen at low saturation values (s = 0.5) is lost for higher values of s, where a minimum can be seen. This minimum corresponds to the simultaneous minimization of noise in δ and amplitude-phase conversion.

Using our model, we also gain insight into the decomposition of the observed phase noise according to the physical origins of the fluctuations, as can be seen in Fig. 2. We show that thermomechanical noise and noise in Δ are the dominant contributions for most values of the phase. For high saturation values, however, it can also be observed that the phase noise at the minimum is not dominated by either of those contributions. There is a different component that is only visible around that region (and is hidden otherwise), which corresponds to fluctuations in the resonant frequency of the mechanical resonator, possibly arising from environmental noise [24,25] or parametric noise tuning the frequency [26]. The diffusion coefficient for this parameter is constant over all of the parameter space; hence, this component of oscillator noise cannot be reduced by tuning the feedback phase. This specific parameter fluctuation imposes a bound on the phase noise reduction that is achievable with this NEMS device (see Supplemental Material [23], Sec. D). However, even with this ultimate limitation the phase noise is rendered significantly lower than is possible using conventional linear schemes.

In summary, we theoretically predict and experimentally demonstrate a fundamental and simple oscillator paradigm that harnesses nonlinear stiffness, in which the phase noise is substantially lower than in linear operation. At the newly identified special points in the s-Δ parameter space, the effects of fluctuations in the feedback phase are eliminated and amplitude-phase conversion of the thermomechanical noise is suppressed. This optimization contravenes conventional wisdom and establishes a new cornerstone for the use of nonlinear resonators as frequency-determining elements in self-sustained oscillators. We highlight that these results are applicable not only to NEMS as used here, but can also be used for any type of resonator (electrical, optical, etc.) that possesses nonlinearity [27–29].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency Microsystems Technology Office, Dynamic Enabled Frequency Sources Program (DEFYS) through Department of Interior (FA8650-10-1-7029). L. G. V. acknowledges financial support from the European Commission (PIOF-GA-2008-220682).

References

- 1.Cady WG. Proc IRE. 1922;10:83. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuo CJ, Sinha N, Van der Spiegel J, Piazza G. J Microelectromech Syst. 2010;19:570. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verd J, Uranga A, Abadal G, Teva JL, Torres F, Lopez J, Perez-Murano F, Esteve J, Barniol N. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2008;29:146. [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Beek JTM, Puers R. J Micromech Microeng. 2012;22:013001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villanueva LG, Karabalin RB, Matheny MH, Chi D, Sader JE, Roukes ML. Phys Rev B. 2013;87:024304. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matheny MH, Villanueva LG, Karabalin RB, Sader JE, Roukes ML. Nano Lett. 2013;13:1622. doi: 10.1021/nl400070e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eichler A, Moser J, Chaste J, Zdrojek M, Wilson-Rae I, Bachtold A. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6:339. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westra HJR, Poot M, van der Zant HSJ, Venstra WJ. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;105:117205. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.117205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karabalin RB, Lifshitz R, Cross MC, Matheny MH, Masmanidis SC, Roukes ML. Phys Rev Lett. 2011;106:094102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.094102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaajakari V, Mattila T, Oja A, Seppa H. J Microelectromech Syst. 2004;13:715. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cleland AN, Roukes ML. J Appl Phys. 2002;92:2758. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dykman MI, Mannella R, Mcclintock PVE, Soskin SM, Stocks NG. Europhys Lett. 1990;13:691. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greywall DS, Yurke B, Busch PA, Pargellis AN, Willett RL. Phys Rev Lett. 1994;72:2992. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.72.2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villanueva LG, Karabalin RB, Matheny MH, Kenig E, Cross MC, Roukes ML. Nano Lett. 2011;11:5054. doi: 10.1021/nl2031162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenig E, Cross MC, Lifshitz R, Karabalin RB, Villanueva LG, Matheny MH, Roukes ML. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;108:264102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.264102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antonio D, Zanette DH, Lopez D. Nat Commun. 2012;3:806. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lifshitz R, Cross MC. In: Reviews of Nonlinear Dynamics and Complexity. Schuster HG, editor. Vol. 1. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2008. pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HK, Melamud R, Chandorkar S, Salvia J, Yoneoka S, Kenny TW. J Microelectromech Syst. 2011;20:1228. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caves CM, Thorne KS, Drever RWP, Sandberg VD, Zimmermann M. Rev Mod Phys. 1980;52:341. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demir A, Mehrotra A, Roychowdhury J. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst I-Fundamental Theor Appl. 2000;47:655. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenig E, Cross MC, Villanueva LG, Karabalin RB, Matheny MH, Lifshitz R, Roukes ML. Phys Rev E. 2012;86:056207. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.86.056207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yurke B, Greywall DS, Pargellis AN, Busch PA. Phys Rev A. 1995;51:4211. doi: 10.1103/physreva.51.4211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.See Supplemental Material at http.//link.aps.org/supplemental/10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.177208 for details on the amplitude equation, scaling parameters, noise intensity estimates, etc.

- 24.Yang YT, Callegari C, Feng XL, Roukes ML. Nano Lett. 2011;11:1753. doi: 10.1021/nl2003158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fong KY, Pernice WHP, Tang HX. Phys Rev B. 2012;85:161410. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karabalin RB, Villanueva LG, Matheny MH, Sader JE, Roukes ML. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;108:236101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.236101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tazzoli A, Rinaldi M, Piazza G. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2012;33:724. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahboob I, Nishiguchi K, Okamoto H, Yamaguchi H. Nat Phys. 2012;8:387. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen CY, Rosenblatt S, Bolotin KI, Kalb W, Kim P, Kymissis I, Stormer HL, Heinz TF, Hone J. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:861. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.